Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

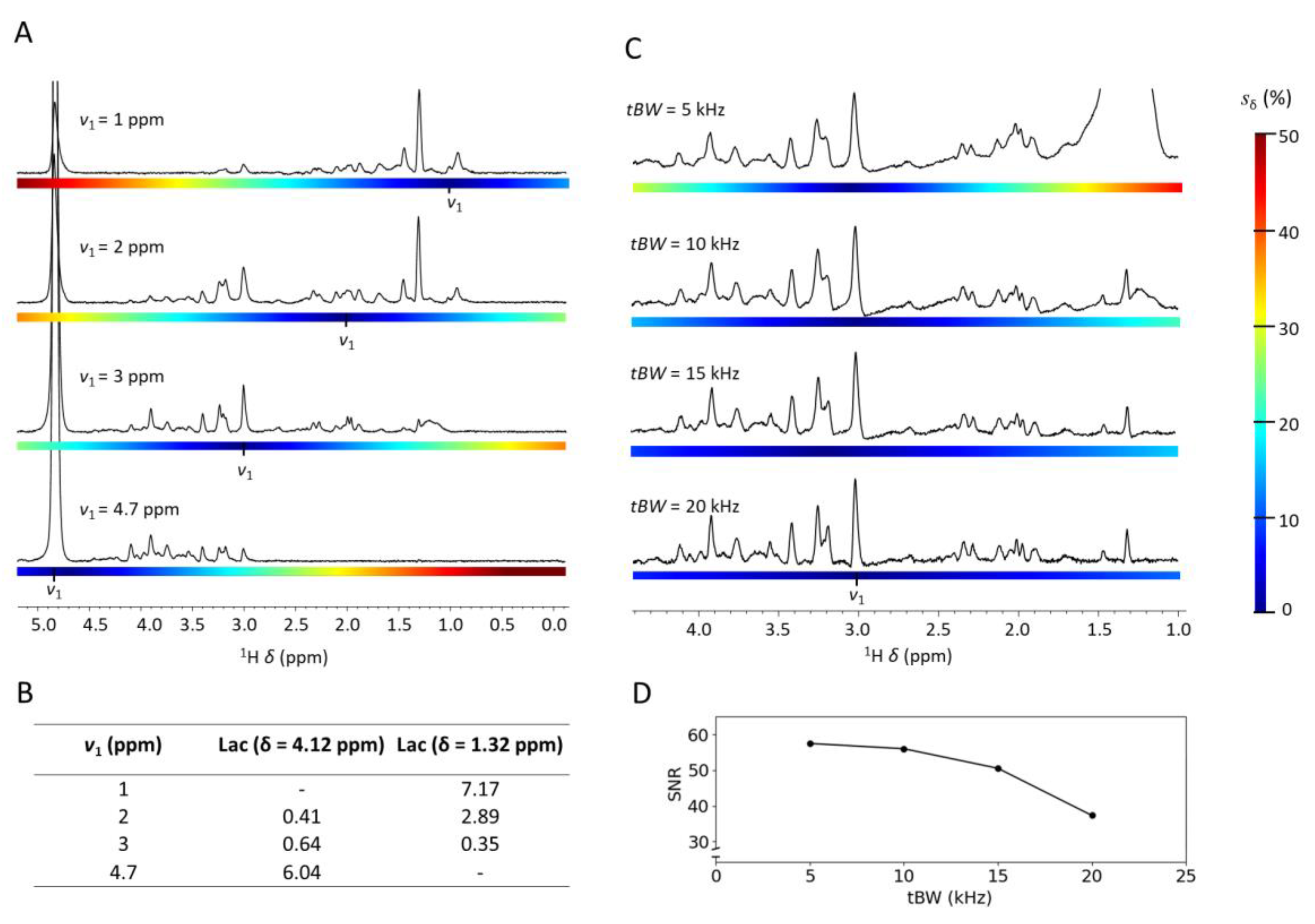

2.1. Mitigating the Chemical Shift Displacement at UHF

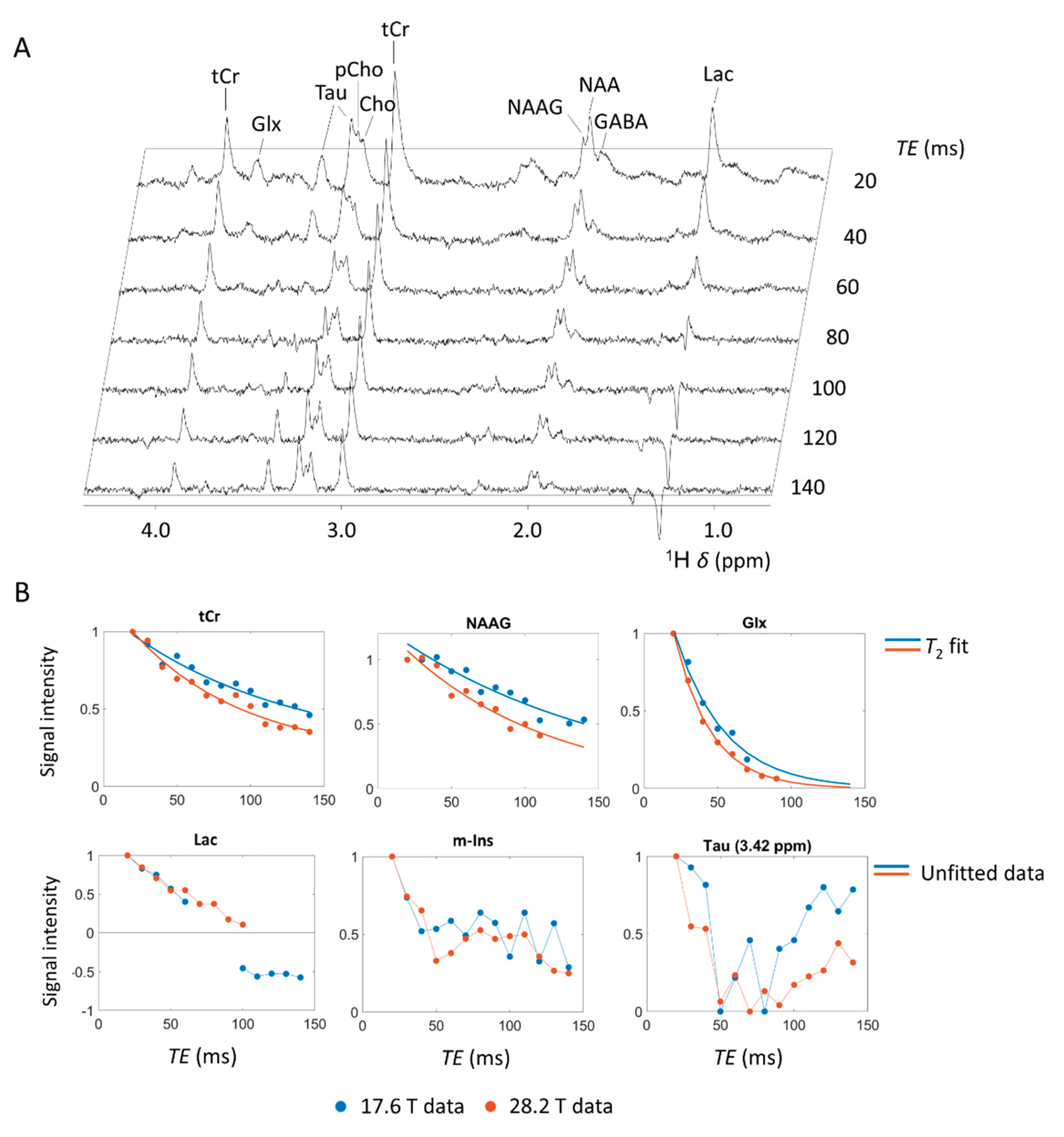

2.2. Localized MRS at Variable Echo Times

2.3. Voxel Volume and Averaging Strategies

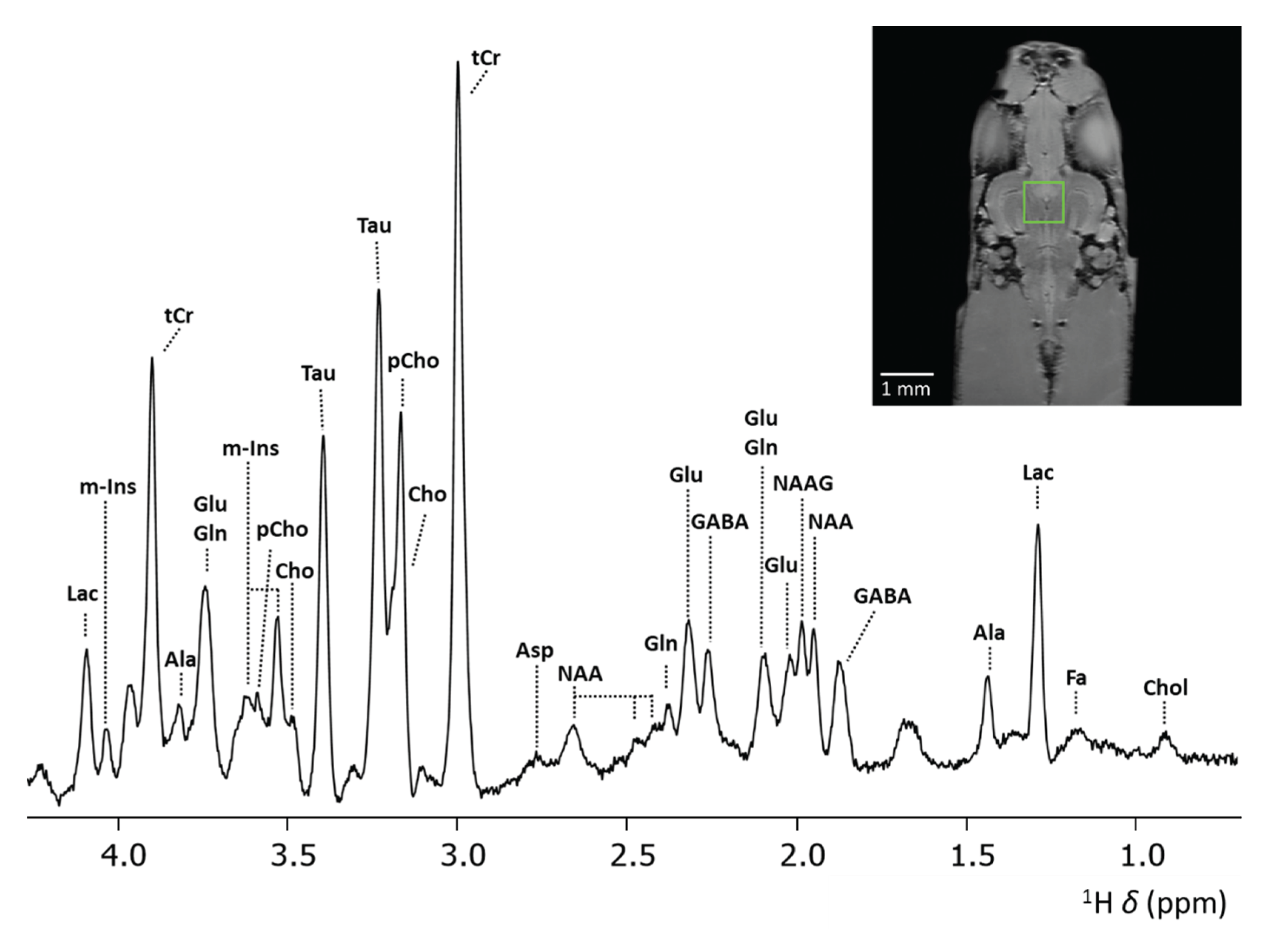

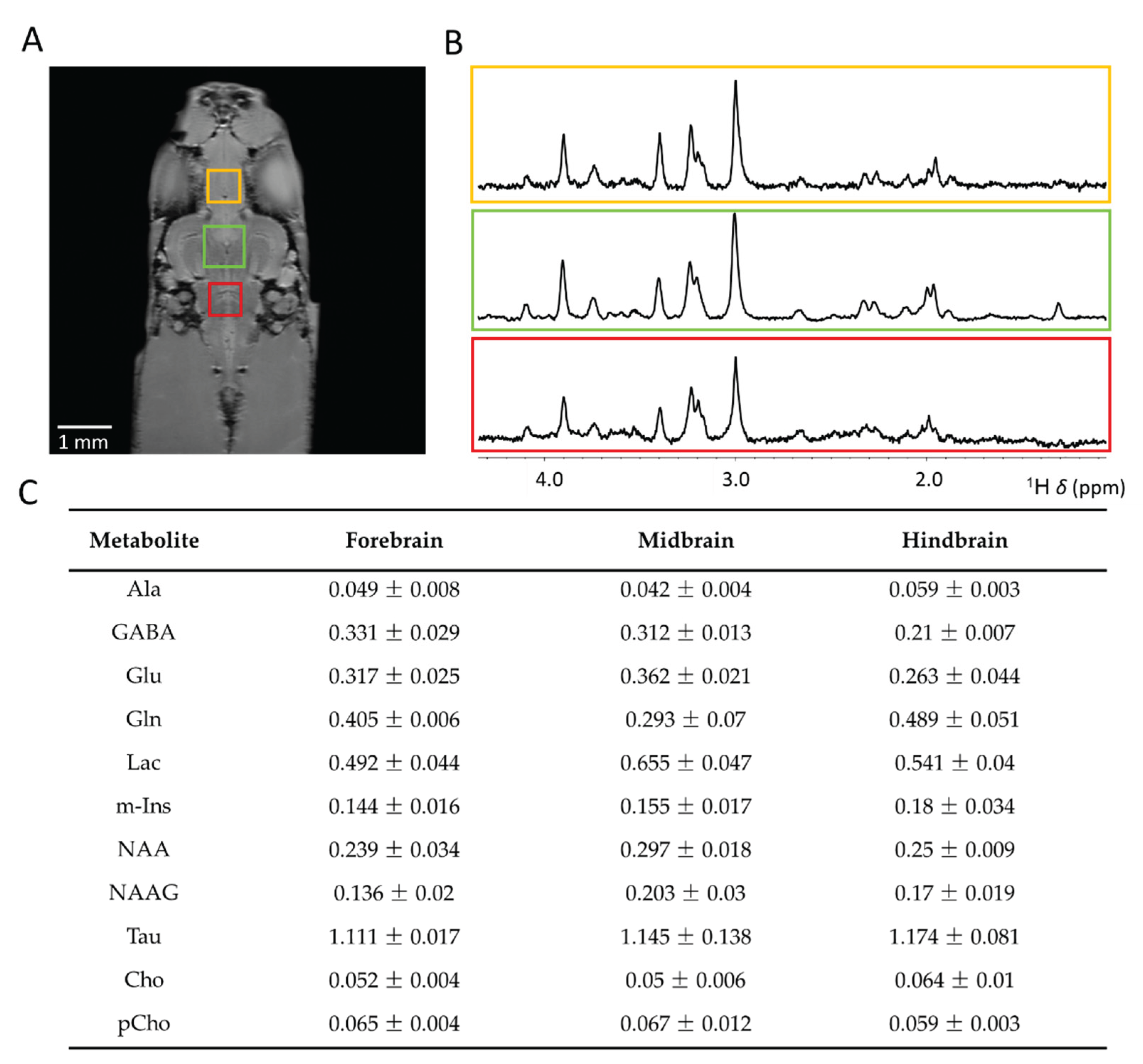

2.4. Metabolite Identification and Quantification at UHF

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Zebrafish Husbandry

3.2. Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy

3.3. Data Processing

5. Conclusions and Future Outlook

| B0 | Magnetic field strength |

| Cr | Creatine |

| G | magnetic field gradient strength |

| GABA | γ-aminobutyric acid |

| Gln | Glutamine |

| Glu | Glutamate |

| HR-MAS | high-resolution magic angle spinning |

| m-Ins | myo-inositol |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MRS | Magnetic resonance spectroscopy |

| NAA | N-acetylaspartate |

| NAAG | N-acetylaspartyl-glutamate |

| ns | number of scans |

| PRESS | Point resolved spectroscopy |

| RARE | rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| sδ | chemical shift displacement |

| T2 | transverse relaxation time |

| Tau | Taurine |

| tBW | transmitter RF pulse bandwidth |

| TE | Echo time |

| TR | repetition time |

| UHF | Ultra-high field |

| v1 | Excitation frequency |

| VAPOR | variable pulse power and optimized relaxation delays |

| Vvoxel | Voxel volume |

| vx | Larmor frequency compound x |

| δ | Chemical shift |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations and Symbols

| B0 | Magnetic field strength |

| Cr | Creatine |

| G | magnetic field gradient strength |

| GABA | γ-aminobutyric acid |

| Gln | Glutamine |

| Glu | Glutamate |

| HR-MAS | high-resolution magic angle spinning |

| m-Ins | myo-inositol |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| MRS | Magnetic resonance spectroscopy |

| NAA | N-acetylaspartate |

| NAAG | N-acetylaspartyl-glutamate |

| ns | number of scans |

| PRESS | Point resolved spectroscopy |

| RARE | rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| sδ | chemical shift displacement |

| T2 | transverse relaxation time |

| Tau | Taurine |

| tBW | transmitter RF pulse bandwidth |

| TE | Echo time |

| TR | repetition time |

| UHF | Ultra-high field |

| v1 | Excitation frequency |

| VAPOR | variable pulse power and optimized relaxation delays |

| Vvoxel | Voxel volume |

| vx | Larmor frequency compound x |

| δ | Chemical shift |

References

- Alger, J.R. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. In Encyclopedia of Neuroscience; Elsevier, 2009; pp. 601–607 ISBN 978-0-08-045046-9.

- Sharma, U.; Jagannathan, N.R. Metabolism of Prostate Cancer by Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS). Biophys Rev 2020, 12, 1163–1173. [CrossRef]

- Cowin, G.J.; Jonsson, J.R.; Bauer, J.D.; Ash, S.; Ali, A.; Osland, E.J.; Purdie, D.M.; Clouston, A.D.; Powell, E.E.; Galloway, G.J. Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy for Monitoring Liver Steatosis. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2008, 28, 937–945. [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.A.; Couch, M.J.; Menezes, R.; Evans, A.J.; Finelli, A.; Jewett, M.A.; Jhaveri, K.S. Predictive Value of In Vivo MR Spectroscopy With Semilocalization by Adiabatic Selective Refocusing in Differentiating Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma From Other Subtypes. American Journal of Roentgenology 2020, 214, 817–824. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.J.; Mirowitz, S.A.; Sandstrom, J.C.; Perman, W.H. MR Spectroscopy of the Heart. American Journal of Roentgenology 1990, 155, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Kantarci, K.; Graff Radford Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Alzheimer’s Disease. NDT 2013, 687. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, B.D.; Kuruva, M.; Shim, H.; Mullins, M.E. Clinical Applications of Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Brain Tumors. Radiologic Clinics of North America 2021, 59, 349–362. [CrossRef]

- Nakahara, T.; Tsugawa, S.; Noda, Y.; Ueno, F.; Honda, S.; Kinjo, M.; Segawa, H.; Hondo, N.; Mori, Y.; Watanabe, H.; et al. Glutamatergic and GABAergic Metabolite Levels in Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of 1H-Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Studies. Mol Psychiatry 2022, 27, 744–757. [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in ALS. Front Neurol 2019, 10, 482. [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.W.; Kuzniecky, R.I. Utility of Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging for Human Epilepsy. 2015 2015, 5, 313–322.

- Sajja, B.R.; Wolinsky, J.S.; Narayana, P.A. Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Multiple Sclerosis. Neuroimaging Clinics of North America 2009, 19, 45–58. [CrossRef]

- Shoeibi, A.; Verdipour, M.; Hoseini, A.; Moshfegh, M.; Olfati, N.; Layegh, P.; Dadgar-Moghadam, M.; Farzadfard, M.T.; Rezaeitalab, F.; Borji, N. Brain Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. CJN 2022. [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.M. Glutamate: The Master Neurotransmitter and Its Implications in Chronic Stress and Mood Disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 722323. [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-de La Paz, L.D.; Gulias-Cañizo, R.; D’Abril Ruíz-Leyja, E.; Sánchez-Castillo, H.; Parodí, J. The Role of GABA Neurotransmitter in the Human Central Nervous System, Physiology, and Pathophysiology. RMN 2021, 22, 5355. [CrossRef]

- Kalra, S.; Arnold, D.L. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy for Monitoring Neuronal Integrity in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. In Proceedings of the N-Acetylaspartate; Moffett, J.R., Tieman, S.B., Weinberger, D.R., Coyle, J.T., Namboodiri, A.M.A., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2006; pp. 275–282.

- Bertran-Cobo, C.; Wedderburn, C.J.; Robertson, F.C.; Subramoney, S.; Narr, K.L.; Joshi, S.H.; Roos, A.; Rehman, A.M.; Hoffman, N.; Zar, H.J.; et al. A Neurometabolic Pattern of Elevated Myo-Inositol in Children Who Are HIV-Exposed and Uninfected: A South African Birth Cohort Study. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 800273. [CrossRef]

- Annunziato, M.; Eeza, M.N.H.; Bashirova, N.; Lawson, A.; Matysik, J.; Benetti, D.; Grosell, M.; Stieglitz, J.D.; Alia, A.; Berry, J.P. An Integrated Systems-Level Model of the Toxicity of Brevetoxin Based on High-Resolution Magic-Angle Spinning Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (HRMAS NMR) Metabolic Profiling of Zebrafish Embryos. Science of The Total Environment 2022, 803, 149858. [CrossRef]

- Annunziato, M.; Bashirova, N.; Eeza, M.N.H.; Lawson, A.; Benetti, D.; Stieglitz, J.D.; Matysik, J.; Alia, A.; Berry, J.P. High-Resolution Magic Angle Spinning (HRMAS) NMR Identifies Oxidative Stress and Impairment of Energy Metabolism by Zearalenone in Embryonic Stages of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio), Olive Flounder (Paralichthys Olivaceus) and Yellowtail Snapper (Ocyurus Chrysurus). Toxins 2023, 15, 397. [CrossRef]

- Annunziato, M.; Bashirova, N.; Eeza, M.N.H.; Lawson, A.; Fernandez-Lima, F.; Tose, L.V.; Matysik, J.; Alia, A.; Berry, J.P. An Integrated Metabolomics-Based Model, and Identification of Potential Biomarkers, of Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid Toxicity in Zebrafish Embryos. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2024, 43, 896–914. [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Liu, L.; Forn-Cuní, G.; Ding, Y.; Alia, A.; Spaink, H. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Studies Reveal That Toll-like Receptor 2 Has a Role in Glucose-Related Metabolism in Unchallenged Zebrafish Larvae (Danio Rerio). Biology 2023, 12, 323. [CrossRef]

- Eeza, M.N.H.; Bashirova, N.; Zuberi, Z.; Matysik, J.; Berry, J.P.; Alia, A. An Integrated Systems-Level Model of Ochratoxin A Toxicity in the Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryo Based on NMR Metabolic Profiling. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 6341. [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.P.; Roy, U.; Jaja-Chimedza, A.; Sanchez, K.; Matysik, J.; Alia, A. High-Resolution Magic Angle Spinning Nuclear Magnetic Resonance of Intact Zebrafish Embryos Detects Metabolic Changes Following Exposure to Teratogenic Polymethoxyalkenes from Algae. Zebrafish 2016, 13, 456–465. [CrossRef]

- Howe, K.; Clark, M.D.; Torroja, C.F.; Torrance, J.; Berthelot, C.; Muffato, M.; Collins, J.E.; Humphray, S.; McLaren, K.; Matthews, L.; et al. The Zebrafish Reference Genome Sequence and Its Relationship to the Human Genome. Nature 2013, 496, 498–503. [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Kannan, R.R. Zebrafish: An Emerging Real-Time Model System to Study Alzheimer’s Disease and Neurospecific Drug Discovery. Cell Death Discov. 2018, 4, 45. [CrossRef]

- Basheer, F.; Dhar, P.; Samarasinghe, R.M. Zebrafish Models of Paediatric Brain Tumours. IJMS 2022, 23, 9920. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.M.; Croll, R.P. A Critical Review of Zebrafish Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 835827. [CrossRef]

- D’Amora, M.; Galgani, A.; Marchese, M.; Tantussi, F.; Faraguna, U.; De Angelis, F.; Giorgi, F.S. Zebrafish as an Innovative Tool for Epilepsy Modeling: State of the Art and Potential Future Directions. IJMS 2023, 24, 7702. [CrossRef]

- Fontana, B.D.; Mezzomo, N.J.; Kalueff, A.V.; Rosemberg, D.B. The Developing Utility of Zebrafish Models of Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: A Critical Review. Experimental Neurology 2018, 299, 157–171. [CrossRef]

- Kabli, S.; Spaink, H.P.; De Groot, H.J.M.; Alia, A. In Vivo Metabolite Profile of Adult Zebrafish Brain Obtained by High-resolution Localized Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2009, 29, 275–281. [CrossRef]

- Singer, R.; Oganezova, I.; Hu, W.; Ding, Y.; Papaioannou, A.; De Groot, H.J.M.; Spaink, H.P.; Alia, A. Unveiling the Exquisite Microstructural Details in Zebrafish Brain Non-Invasively Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging at 28.2 T. Molecules 2024, 29, 4637. [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, J.F.P.; Calamante, F.; Collin, S.P.; Reutens, D.C.; Kurniawan, N.D. Enhanced Characterization of the Zebrafish Brain as Revealed by Super-Resolution Track-Density Imaging. Brain Struct Funct 2015, 220, 457–468. [CrossRef]

- Soila, K.P.; Viamonte, M.; Starewicz, P.M. Chemical Shift Misregistration Effect in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Radiology 1984, 153, 819–820. [CrossRef]

- Lufkin, R.; Anselmo, M.; Crues, J.; Smoker, W.; Hanafee, W. Magnetic Field Strength Dependence of Chemical Shift Artifacts. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 1988, 12, 89–96. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo-Tobon, S.S. Theory of Gradient Coil Design Methods for Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Concepts Magnetic Resonance 2010, 36A, 223–242. [CrossRef]

- Krug, J.R.; Van Schadewijk, R.; Vergeldt, F.J.; Webb, A.G.; De Groot, H.J.M.; Alia, A.; Van As, H.; Velders, A.H. Assessing Spatial Resolution, Acquisition Time and Signal-to-Noise Ratio for Commercial Microimaging Systems at 14.1, 17.6 and 22.3 T. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2020, 316, 106770. [CrossRef]

- Kreis, R. Issues of Spectral Quality in Clinical1 H-magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy and a Gallery of Artifacts. NMR in Biomedicine 2004, 17, 361–381. [CrossRef]

- Redpath, T.W.; Wiggins, C.J. Estimating Achievable Signal-to-Noise Ratios of MRI Transmit-Receive Coils from Radiofrequency Power Measurements: Applications in Quality Control. Phys. Med. Biol. 2000, 45, 217–227. [CrossRef]

- Dumoulin, M.; Zimmerman, E.; Hurd, R.; Hancu, I. Increased Brain Metabolite T2 Relaxation Times in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease.

- De Graaf, R.A.; Brown, P.B.; McIntyre, S.; Nixon, T.W.; Behar, K.L.; Rothman, D.L. High Magnetic Field Water and Metabolite Proton T1 and T2 Relaxation in Rat Brain in Vivo. Magnetic Resonance in Med 2006, 56, 386–394. [CrossRef]

- Murali-Manohar, S.; Borbath, T.; Wright, A.M.; Soher, B.; Mekle, R.; Henning, A. T2 Relaxation Times of Macromolecules and Metabolites in the Human Brain at 9.4 T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2020, 84, 542–558. [CrossRef]

- Deelchand, D.K.; Auerbach, E.J.; Kobayashi, N.; Marjańska, M. Transverse Relaxation Time Constants of the Five Major Metabolites in Human Brain Measured in Vivo Using LASER and PRESS at 3 T. Magn Reson Med 2018, 79, 1260–1265. [CrossRef]

- Bloembergen, N.; Purcell, E.M.; Pound, R.V. Relaxation Effects in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Absorption. Phys. Rev. 1948, 73, 679–712. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. T1 and T2 Metabolite Relaxation Times in Normal Brain at 3T and 7T. J Mol Imag Dynamic 2013, 02. [CrossRef]

- Michaeli, S.; Garwood, M.; Zhu, X.-H.; DelaBarre, L.; Andersen, P.; Adriany, G.; Merkle, H.; Ugurbil, K.; Chen, W. Proton T2 Relaxation Study of Water, N-Acetylaspartate, and Creatine in Human Brain Using Hahn and Carr-Purcell Spin Echoes at 4T and 7T. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 2002, 47, 629–633. [CrossRef]

- Jiru, F.; Skoch, A.; Wagnerova, D.; Dezortova, M.; Viskova, J.; Profant, O.; Syka, J.; Hajek, M. The Age Dependence of T2 Relaxation Times of N-Acetyl Aspartate, Creatine and Choline in the Human Brain at 3 and 4T. NMR in Biomedicine 2016, 29, 284–292. [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Gambarota, G.; Cudalbu, C.; Mlynárik, V.; Gruetter, R. Single Spin-Echo T2 Relaxation Times of Cerebral Metabolites at 14.1 T in the in Vivo Rat Brain. Magn Reson Mater Phy 2013, 26, 549–554. [CrossRef]

- Isobe, T.; Matsumura, A.; Anno, I.; Kawamura, H.; Muraishi, H.; Umeda, T.; Nose, T. Effect of J Coupling and T2 Relaxation in Assessing of Methyl Lactate Signal Using PRESS Sequence MR Spectroscopy. Igaku Butsuri 2005, 25, 68–74.

- Xin, L.; Gambarota, G.; Mlynárik, V.; Gruetter, R. Proton T2 Relaxation Time of J -coupled Cerebral Metabolites in Rat Brain at 9.4 T. NMR in Biomedicine 2008, 21, 396–401. [CrossRef]

- Mulkern, R.; Bowers, J. Density Matrix Calculations of AB Spectra from Multipulse Sequences: Quantum Mechanics Meets In Vivo Spectroscopy. Concepts Magn. Reson. 1994, 6, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Bottomley, P.A.; Foster, T.H.; Argersinger, R.E.; Pfeifer, L.M. A Review of Normal Tissue Hydrogen NMR Relaxation Times and Relaxation Mechanisms from 1–100 MHz: Dependence on Tissue Type, NMR Frequency, Temperature, Species, Excision, and Age. Medical Physics 1984, 11, 425–448. [CrossRef]

- De Graaf, R.A.; Brown, P.B.; McIntyre, S.; Nixon, T.W.; Behar, K.L.; Rothman, D.L. High Magnetic Field Water and Metabolite Proton T1 and T2 Relaxation in Rat Brain in Vivo. Magnetic Resonance in Med 2006, 56, 386–394. [CrossRef]

- Korb, J.; Bryant, R.G. Magnetic Field Dependence of Proton Spin-lattice Relaxation Times. Magnetic Resonance in Med 2002, 48, 21–26. [CrossRef]

- Öz, G.; Deelchand, D.K.; Wijnen, J.P.; Mlynárik, V.; Xin, L.; Mekle, R.; Noeske, R.; Scheenen, T.W.J.; Tkáč, I.; Mrs, the E.W.G. on A.S.V. 1H Advanced Single Voxel 1H Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Techniques in Humans: Experts’ Consensus Recommendations. NMR in Biomedicine 2021, 34, e4236. [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Tkáč, I. A Practical Guide to in Vivo Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy at High Magnetic Fields. Analytical Biochemistry 2017, 529, 30–39. [CrossRef]

- Govindaraju, V.; Young, K.; Maudsley, A.A. Proton NMR Chemical Shifts and Coupling Constants for Brain Metabolites. NMR Biomed 2000, 13, 129–153. [CrossRef]

- Lodder-Gadaczek, J.; Becker, I.; Gieselmann, V.; Wang-Eckhardt, L.; Eckhardt, M. N-Acetylaspartylglutamate Synthetase II Synthesizes N-Acetylaspartylglutamylglutamate. J Biol Chem 2011, 286, 16693–16706. [CrossRef]

- Berger, U.V.; Luthi-Carter, R.; Passani, L.A.; Elkabes, S.; Black, I.; Konradi, C.; Coyle, J.T. Glutamate carboxypeptidase II is expressed by astrocytes in the adult rat nervous system. Journal of Comparative Neurology 1999, 415, 52–64. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, G.; Stauch-Slusher, B.; Sim, L.; Hedreen, J.C.; Rothstein, J.D.; Kuncl, R.; Coyle, J.T. Reductions in Acidic Amino Acids andN-Acetylaspartylglutamate in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis CNS. Brain Research 1991, 556, 151–156. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, G. Abnormal Excitatory Neurotransmitter Metabolism in Schizophrenic Brains. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995, 52, 829. [CrossRef]

- Reischauer, C.; Gutzeit, A.; Neuwirth, C.; Fuchs, A.; Sartoretti-Schefer, S.; Weber, M.; Czell, D. In-Vivo Evaluation of Neuronal and Glial Changes in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis with Diffusion Tensor Spectroscopy. NeuroImage: Clinical 2018, 20, 993–1000. [CrossRef]

- Provencher, S.W. Estimation of Metabolite Concentrations from Localized in Vivo Proton NMR Spectra. Magnetic Resonance in Med 1993, 30, 672–679. [CrossRef]

- Edden, R.A.E.; Pomper, M.G.; Barker, P.B. In Vivo Differentiation of N-acetyl Aspartyl Glutamate from N-acetyl Aspartate at 3 Tesla. Magnetic Resonance in Med 2007, 57, 977–982. [CrossRef]

- Braakman, N.; Oerther, T.; De Groot, H.J.M.; Alia, A. High Resolution Localized Two-dimensional MR Spectroscopy in Mouse Brain in Vivo. Magnetic Resonance in Med 2008, 60, 449–456. [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Raj Choudhary, P.; Kumar Nirmal, N.; Syed, F.; Verma, R. Neurotransmitter Systems in Zebrafish Model as a Target for Neurobehavioural Studies. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 69, 1565–1580. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Yoon, B.-E. Altered GABAergic Signaling in Brain Disease at Various Stages of Life. Exp Neurobiol 2017, 26, 122–131. [CrossRef]

- Puts, N.A.J.; Edden, R.A.E. In Vivo Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy of GABA: A Methodological Review. Progress in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy 2012, 60, 29–41. [CrossRef]

- Lanz, B.; Abaei, A.; Braissant, O.; Choi, I.-Y.; Cudalbu, C.; Henry, P.-G.; Gruetter, R.; Kara, F.; Kantarci, K.; Lee, P.; et al. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy in the Rodent Brain: Experts’ Consensus Recommendations. NMR Biomed 2020, e4325. [CrossRef]

- Satou, C.; Kimura, Y.; Hirata, H.; Suster, M.L.; Kawakami, K.; Higashijima, S. Transgenic Tools to Characterize Neuronal Properties of Discrete Populations of Zebrafish Neurons. Development 2013, 140, 3927–3931. [CrossRef]

- Tabor, K.M.; Marquart, G.D.; Hurt, C.; Smith, T.S.; Geoca, A.K.; Bhandiwad, A.A.; Subedi, A.; Sinclair, J.L.; Rose, H.M.; Polys, N.F.; et al. Brain-Wide Cellular Resolution Imaging of Cre Transgenic Zebrafish Lines for Functional Circuit-Mapping. eLife 2019, 8, e42687. [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Ding, Y.; Nowik, N.; Jager, C.; Eeza, M.N.H.; Alia, A.; Baelde, H.J.; Spaink, H.P. Leptin Deficiency Affects Glucose Homeostasis and Results in Adiposity in Zebrafish. Journal of Endocrinology 2021, 249, 125–134. [CrossRef]

- Bottomley, P.A. Selective Volume Method for Performing Localized NMR Spectroscopy 1984.

- Tkac, I.; Starcuk, Z.; Choi, I.-Y.; Gruetter, R. In Vivo 1H NMR Spectroscopy of Rat Brain at 1 Ms Echo Time. Magn. Reson. Med. 1999, 41, 649–656. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.T.; Mushtaq, M.Y.; Verpoorte, R.; Richardson, M.K.; Choi, Y.H. Zebrafish as a Model for Systems Medicine R&D: Rethinking the Metabolic Effects of Carrier Solvents and Culture Buffers Determined by1 H NMR Metabolomics. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology 2016, 20, 42–52. [CrossRef]

- Markley, J.L.; Anderson, M.E.; Cui, Q.; Eghbalnia, H.R.; Lewis, I.A.; Hegeman, A.D.; Li, J.; Schulte, C.F.; Sussman, M.R.; Westler, W.M.; et al. New Bioinformatics Resources for Metabolomics. Pac Symp Biocomput 2007, 157–168.

- De Graaf, R.A. In Vivo NMR Spectroscopy: Principles and Techniques; 1st ed.; Wiley, 2007; ISBN 978-0-470-02670-0.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).