1. Introduction

Anticoagulation therapy is a widely used treatment in intensive care units (ICUs) and is closely related to the use of ventricular assist devices (IMPELLA), haemodynamic support with extracorporeal circulation (ECMO), and continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT). The most commonly used drug for this purpose is unfractionated heparin (UFH), which re-quires repeated measurements and rapid availability of results for dose adjustment.

Anticoagulation levels are generally monitored using activated partial thromboplastin time performed in the clinical laboratory (aPTT-lab) [

1]. However, it has some limitations: its accuracy may vary depending on the technique used, sample transport causes delays in ob-taining the results, and it may compromise the precision of measurements. The current re-commendation is to standardize aPTT values by normalizing the values measured in he-

parinized patients to the mean of the normal range of patients without heparin to calculate the aPTT ratio for monitoring. The therapeutic range for aPTT was set to 1.5–2.5 times [

2]. This standardization also allows for interhospital adjustment by correcting for differences be-tween instruments and reagents.

The availability of a bedside measurement of anticoagulation (point of care POC) has important benefits in decision-making [

1], mainly in patients at high risk of bleeding, such as the type of patients admitted to the ICU. The trend is toward the increasing use of POC testing that provides early results and the need for a low sample volume. This is particularly im-portant in patients who require regular assessment of their anticoagulation status, sometimes several times a day, resulting in a considerable volume of blood being drawn during therapy. Werfen Hemochron® has the measurement of two ACT-POCs, one for low anticoagulation range (ACT-LR) and another when higher anticoagulation intensity is required (ACT+), such as in cardiac surgery and interventional procedures. ACT has been used to monitor antico- agulation in patients with IMPELLA and ECMO ventricular assist devices [

3], but with a high degree of uncertainty, as highlighted in the ELSO guidelines on anticoagulation in ECMO [

2], given the lack of correlation with the aPTT-lab [

4] and that the cumulative experience is in cardiac surgery and the catheterization laboratory [

5]. In the context of low-dose heparin anticoagulation, ACT-LR or aPTT-POC may be indicated for monitoring and adjustment; however, there is scarce published experience. The published studies in- cluded only patients undergoing cardiac surgery and other hospitalized patients and did not include those critically ill [

6]. These studies may have limitations in ICUs because the doses of UFH used in this setting are lower and for longer periods of time. A systematic review con-ducted by Brown E et al in 2016 highlighted the lack of evidence of good quality in this patient group [

7]. In 2019, Lohith Karigowda et al. conducted the first prospective study on this spe- cific population and observed moderate agreement between whole blood aPTT-POC and aPTT-lab (r: 0.65; 95% range 23.4%-28% with a percentage bias of 5%, increasing with test delay above 90 seconds). However, in an analysis of the overall concordance, the authors found it to be poor and considered the results inaccurate [

8].

The aim of this study was to assess the correlation and agreement between ACT-LR, aPTT-POC measurements and aPTT-lab in a cohort of critically ill patients re quiring an- ticoagulation.

2. Materials and Methods

We included consecutive patients admitted to a 22-bed ICU undergoing anticoagula-tion with UFH for any cause, including the use of ventricular assist devices and extracorpo- real circuits (ECMO and CRRT), from January 2022 to January 2024. The exclusion criteria were: age < 18 years and use of other anticoagulants (low molecular weight heparin, direct thrombin inhibitors among others). The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of the Hospital Universitario Clínico San Cecilio de Granada (No. 1970-N-21). The requirement for written informed consent was waived.

This is a concordance and correlation study of laboratory tests to compare results obtained using POC tests with those obtained in the clinical laboratory. The variables of interest were aPTT-lab, aPTT-POC, and ACT-LR. Demographic variables, severity at admi- ssion, and indication for anticoagulation were also recorded.

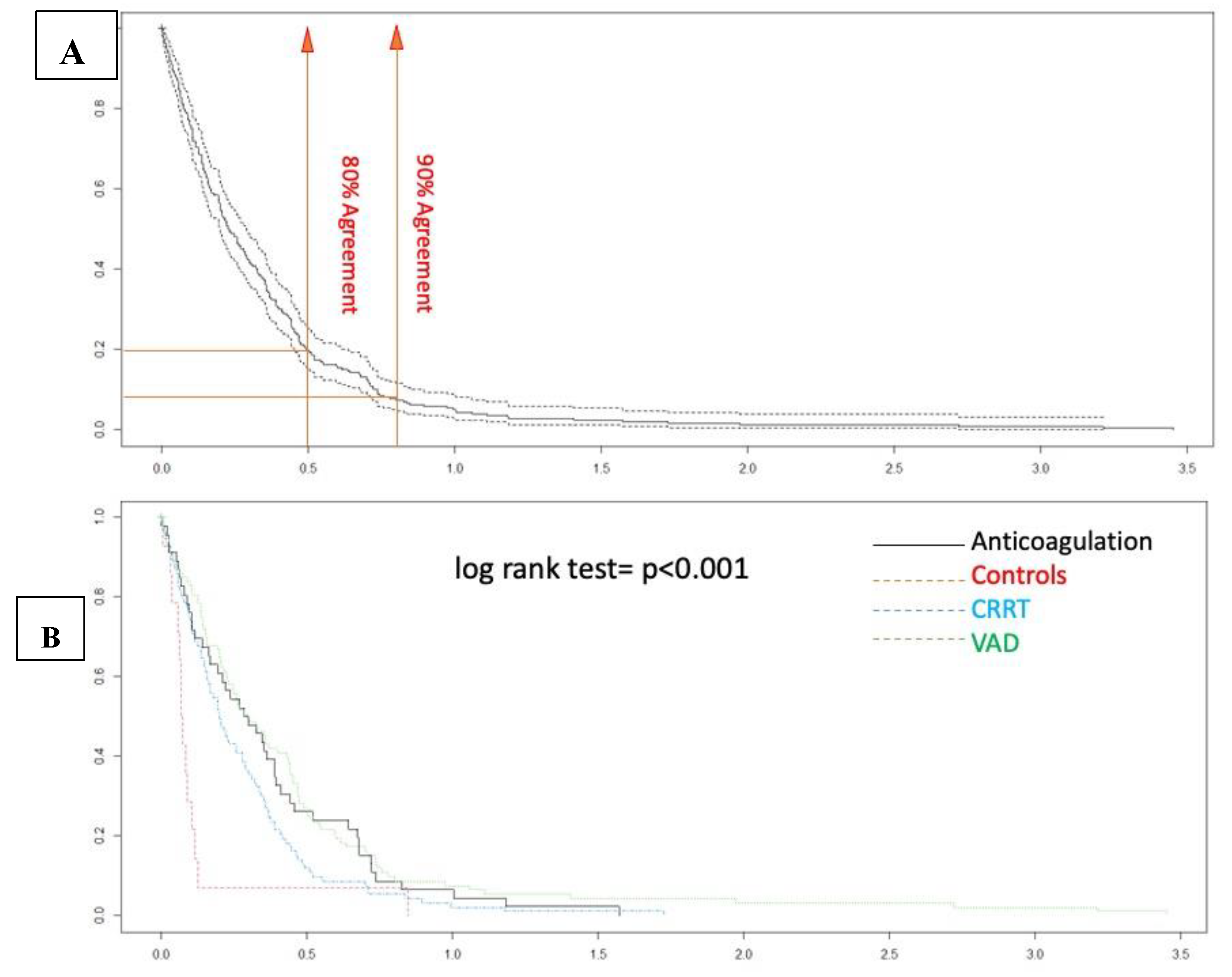

The r-commander software was combined with the rcommader.EZR plugin was used to calculate the sample size. To compare two proportions with 10% disagreement (90% probability of agreement vs. 80%) between the two, 106 measurements are re- quired.

The Werfen Hemochron® device was used for bedside coagulation monitoring. The disposables used for the determination of ACT-POC and ACT-LR were used. According to the usual anticoagulation protocol, blood samples were drawn in a 5 ml syringe at the same time as the aPTT-lab. Thus, three simultaneous measurements were performed for each test: aPTT-lab, aPTT-POC, and ACT-LR. Non-citrated whole blood was used for the POC samples. The samples assayed in the laboratory were centrifuged for 10 minutes to produce platelet poor plasma before aPTT-lab was performed on the Werfen ACL TOP 750 system with the reference values being 24-37 seconds. The reference ranges for normal POC values with He- mochron Werfen are 20.6 to 38.6 seconds for aPTT-POC and 113 to 149 seconds for ACT-LR. The aPTT-lab is considered the gold standard.

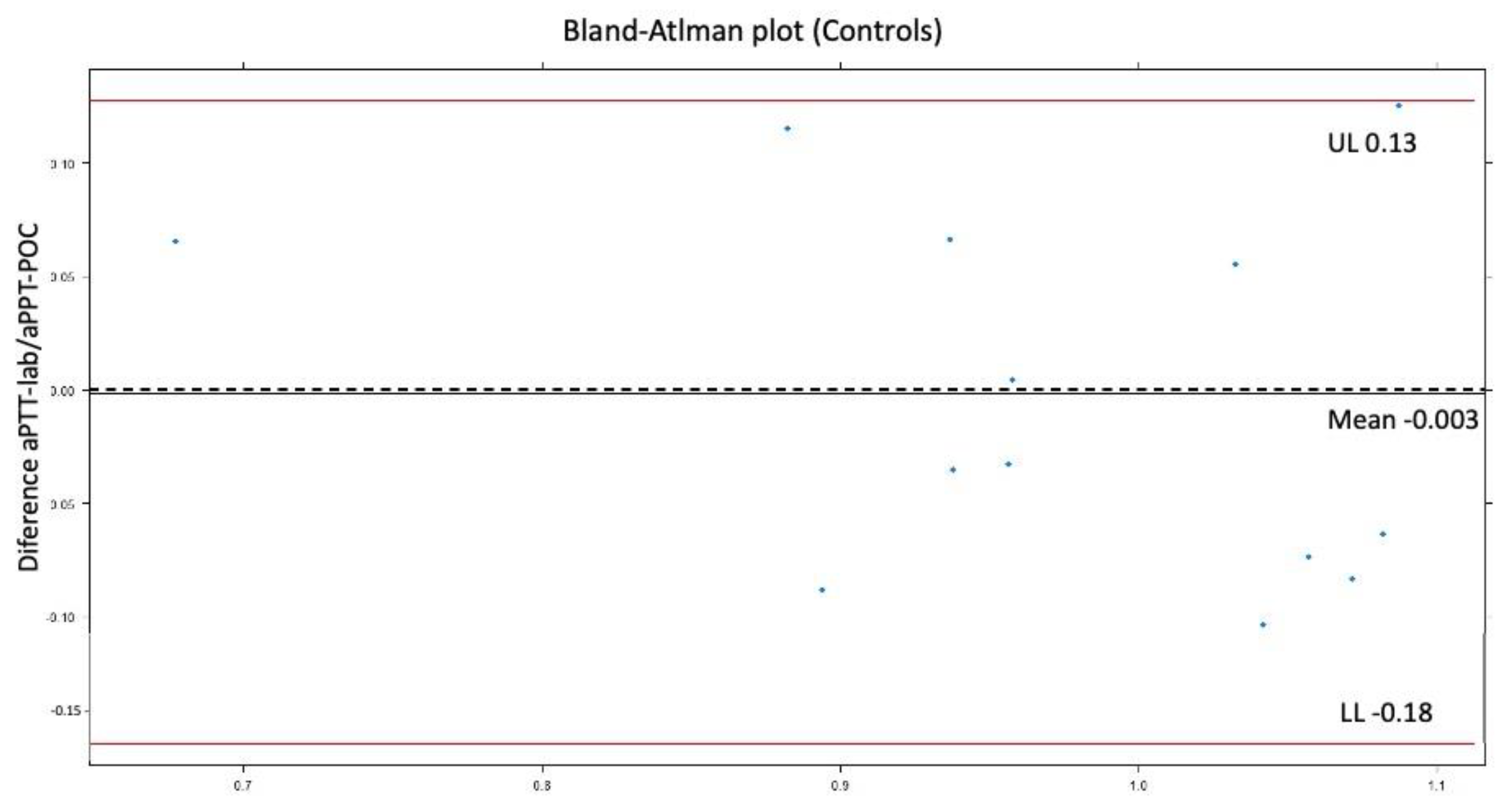

As a control, 14 samples from healthy volunteers were used to determine the normal range and mean POC measurements in patients who did not receive heparin. The aPTT-POC ratio was calculated by dividing the result of the patient’s measurement by the mean result f the control group.

Statistical Analysis

Data were imported from an Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using the statistical package r commander 2.7-2 (R v 4.2.0). Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables as means (standard deviation) or medians (inter-quartile ranges).

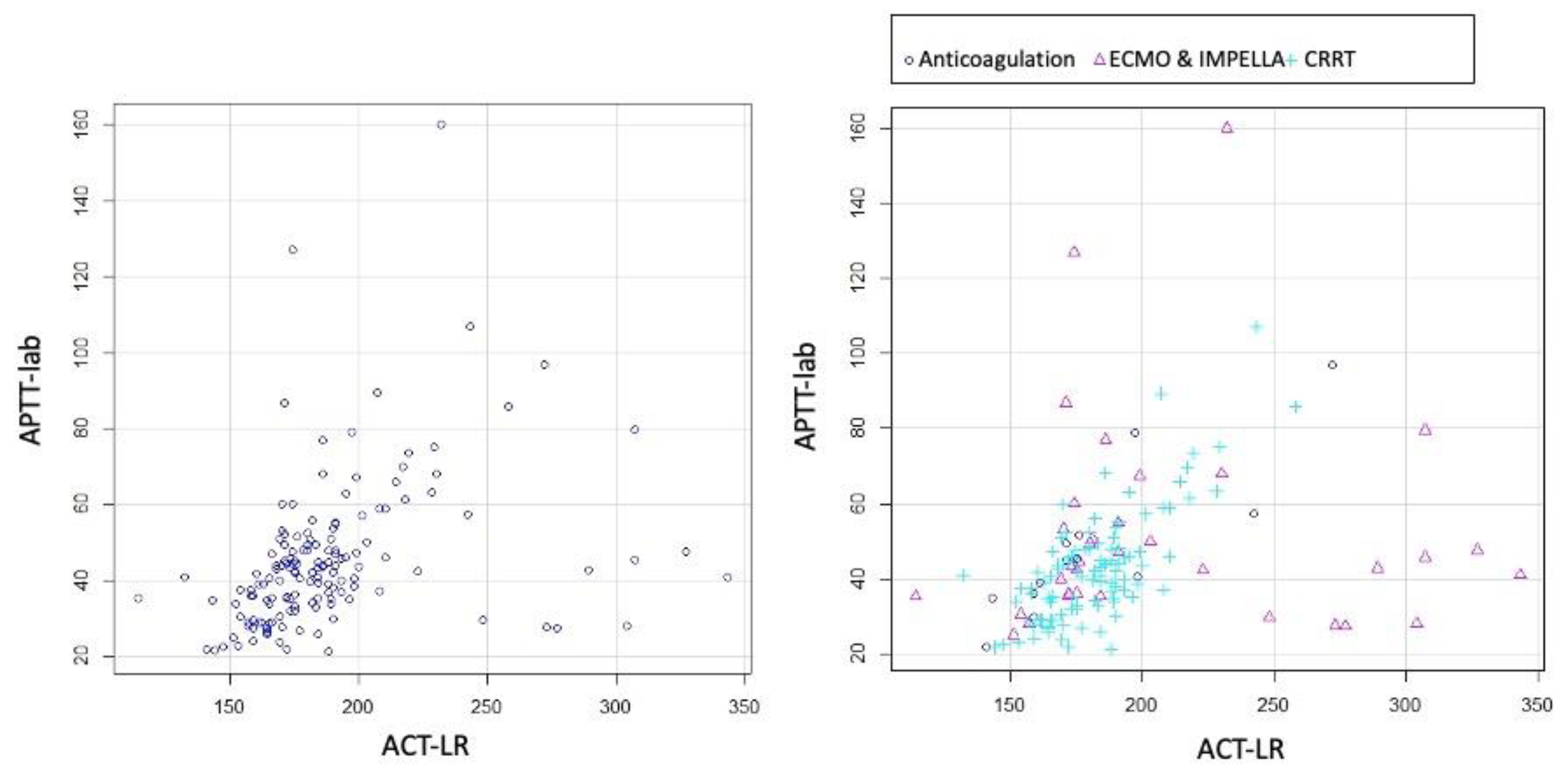

omparisons between aPTT-lab and ACT were performed using scatter plots and Spearman’s correlation coefficient (r). Correlations were interpreted as low (r<0.6), moderate (r between 0.6 and 0.8) or strong (r>0.8) [

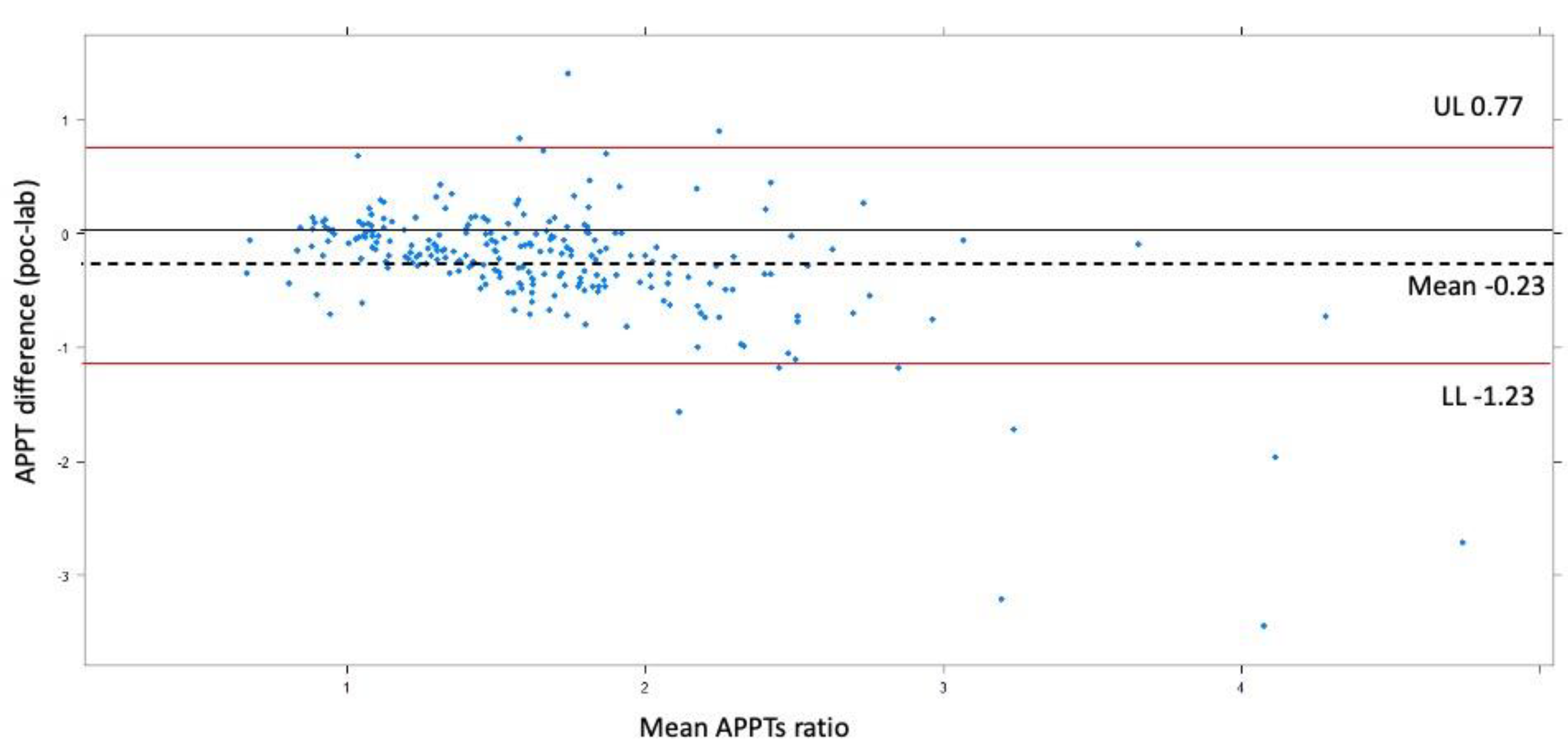

9]. The concordance analysis of the aPTT-Lab and aPTT-POC measurements was performed using the Bland-Altman method and the construc-tion of disagreement-survival plots [

9]. The comparison of aPTT values was performed using the normalized ratio. The Bland-Altman method uses a scatter plot to study the degree of agreement of 2 quantitative measures by constructing a graph where the ordinate axis repre-sents the difference of the measurements and the abscissa axis represents the mean of both measurements. A perfect agreement produces a line parallel to the abscissa axis at point 0. The resulting scatterplot allows the agreement to be estimated visually and numerically by the mean difference between the measurements and the upper and lower cut-off points (±2dt).

If there is good agreement, the mean difference in the measurements will be close to zero and the point cloud will be between ±2dt cut-off points. Following the recommendations of the National External Quality Assessment Scheme (NEQAS) in the UK and the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments in the USA (CLIA), we calculated the plot difference as a percentage, considering the POC determination to be accurate if it is within 10-15% [

8].

The disagreement-survival curves allow the assessment of the percentage of dis- agreement between two estimates for different cutoff points. The percentage of agreement at the absolute value of the measurement difference was calculated from the cut-off point of the curve to the upper value of the ordinate axis. To assess the direction of bias and evaluate the influence of different factors, we performed a stratified analysis according to the method of Llorca and Delgado-Rodríguez [

10].

4. Discussion

In this study, we observed that aPTT-POC and ACT-LR measurements had moderate accuracy for monitoring POC anticoagulation in critically ill patients treated with intravenous heparin. This result is in contrast with the near-perfect accuracy in the healthy volunteer group and is due to the presence of several factors in critically ill patients that dis-tort their results.

Anticoagulation monitoring in critically ill patients receiving intravenous heparinisa-tion is essential to avoid complications due to under- or overdosing, especially in patients with devices. There remains a lack of standardization in monitoring, as reflected in the results of the latest ELSO 2024 survey of European centers involved in the care of adults on mecha-nical cardiocirculatory support. Of the respondents, 72.4% adhered to locally established pro-tocols, with laboratory-measured aPTT monitoring predominating (43.1% with the use of IM- PELLA and 32.9% in ECMO patients). In the remaining cases, considerable heterogeneity was observed between centers [

10,

11].

Despite the known benefits of intravenous heparinisation, it can have an unpredictable dose-response effect in critically ill patients, making its use challenging. This group is cha-

racterized by a high risk of both bleeding (the most frequent and feared complication in pa- tients with devices) and thrombotic events. The use of POC systems, if determined to be a-

ccurate, will help to adjust UFH doses quickly and improve patient care by reducing the delay in obtaining results inherent in sample transport and processing. This allows decisions to be made quickly and accurately. However, to date, although POC testing is available, the accu- racy and validation studies of ECMO [

2] are very limited, as recognized in the afore men- tioned ELSO 2021 anticoagulation guidelines.

The accuracy of POC devices in critically ill patients receiving intravenous heparinisa- tion is limited, and the results are conflicting. These studies used different POC devices (He-mochron 801, Hemochron Junior, Hemochron Response, Hemochron Signature Elite, etc.) and had different case mixes (ICU or non-ICU patients) with or without therapeutic antico-agulation using intravenous heparinisation. In our study, we used the Hemochron Werfen® device; thus, it is difficult to compare our results with those of studies using other tools.

Among the coagulation parameters measured at bedside, ACT is the most widely used strategy. The correlation between ACT and aPTT-lab was poor [

6,

7], with aPTT-lab[

8] being considered superior. The limitations of ACT in this group of patients are widely described, with its results being insensitive to various factors (platelet alteration, fibrinogen levels, etc [

12]). This has led to a progressive shift from the use of ACT to aPTT-lab, which has been clearly reflected in the different ELSO surveys (2013 and 2021 [

13,

14]). The addition of the ACT-LR test to low-dose heparin monitoring was intended to overcome the problems asso- ciated with ACT. However, its accuracy has also been questioned in many studies, with up to 22% of the results being classified as incorrect during vascular surgery with low-dose in-travenous heparinisation [

15]. Another study by Atallah et al [

15,

16] (ECMO patients) found a low correlation between paired samples of ACT-LR and aPTT (r=0.41), as well as with the dose of heparin administered (r=0.11-0.14). These data were also reproduced in patients who underwent ECMO-PCR with even lower correlations [

17].

The ACT-LR correlation in our study was better in the control group (r=0.7) than in those treated with intravenous heparin. This may be explained by the influence of alterations in critical patients in relation to certain factors, such as hematocrit and platelets, as the ana-lysis on whole blood samples are standardized to normal values. This potential bias is even more evident in patients treated with ventricular support devices who are routinely subjected to thrombopenia, transfusions, and haemodilution. The correlation in medically anticoagu-lated patients has been shown to be higher (r=0.7) and similar to that of our cohort if we include the control group and medically anticoagulated patients (r=0.8), supporting the po-tential influence of these external factors on the validity of the ACT-LR.

Published studies on the validity of aPTT-POC as a substitute for laboratory tests have not found satisfactory results. Several studies in the context of acute haemorhage. Gauss et al [

18] used Hemochron Signature Elite for this purpose. Their definition of acceptable agree-ment was that no more than 5 % of the aPTT-POC results differed by more than 20 % from aPTT-lab. They observed a total of 89% of the aPTT-POC measurements were out of range. It is assumed that bleeding is associated with rapid changes in hematocrit and platelet counts and other factors, including fluid therapy and transfusion [

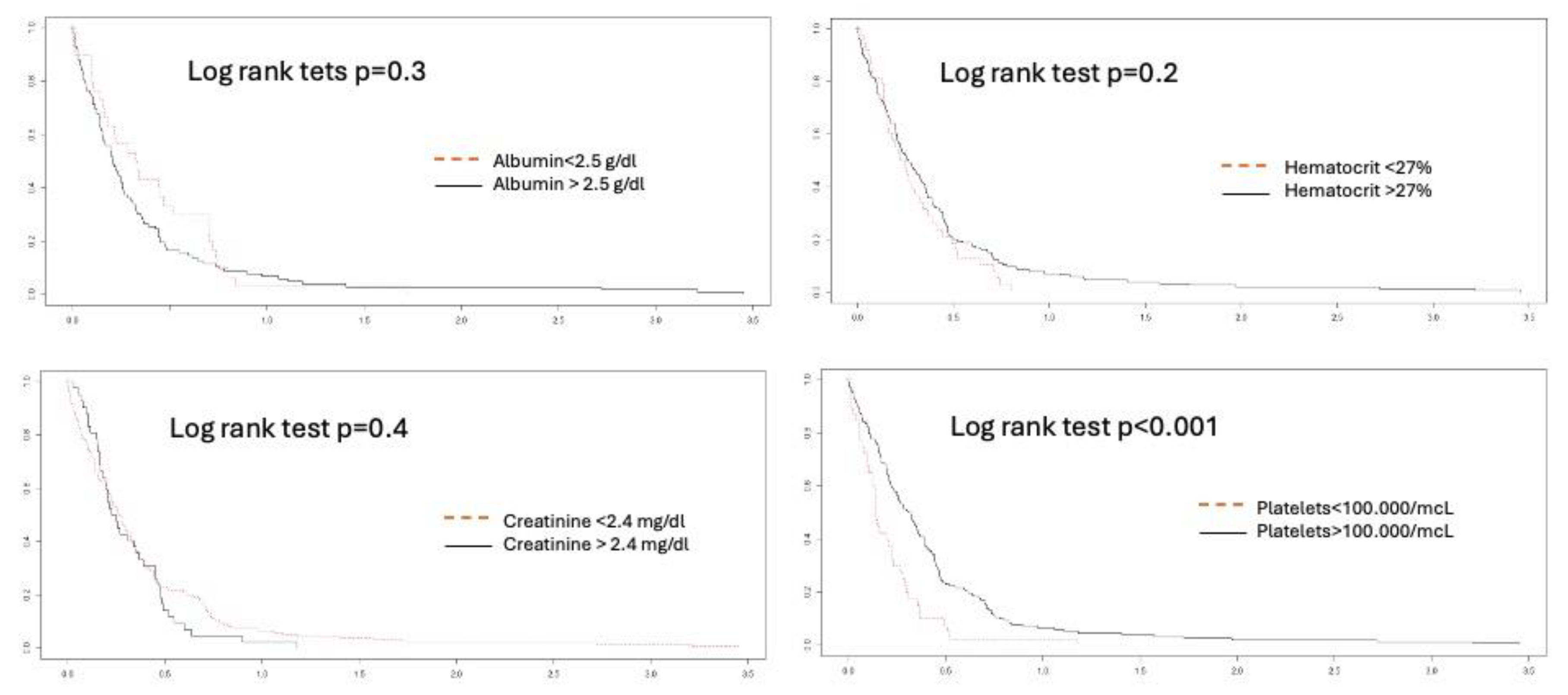

19]. In our case, after considering these confounding factors, we observed that the presence of thrombopenia < 100,000/µL modified the concordance significantly

(Figure 5).

Gauss et al. showed poor concordance in patients with acute bleeding requiring trans- fusion. In this study, we did not find any reference to the normality value used for calculating the ratio between the POC and the laboratory samples [

18]. In our case, the aPTT-POC measurements underestimated the laboratory values, as shown in

figure 3. However, it should be noted that the agreement is better in the range of the aPTT ratio between 1.5 and 2, which is the usual target aPTT range for anticoagulation with UFH. The worst agreement was ob-served at high anticoagulation values. This was also the first study to assess the accuracy of aPTT-POC in ICU patients [

8]. This prospective study included patients requiring all-cause anticoagulation in the ICU (APACHE II medium 18). The main indications for UFH infusion were pulmonary embolism and atrial fibrillation. Comparisons were made between labora-tory and POC values in both whole blood and citrated blood according to whether the aPTT was less or more than 90 seconds.

The limits of agreement were wider and the bias was greater with aPTT POC obtained using citrated blood than with that obtained using whole blood. Agreement was better at aPTT POC values below 90 seconds and bias increased with increasing aPTT POC values. The results showed that adjusting the UFH dose based on the aPTT-POC measurement re-sulted in more patients receiving inadequate than excessive doses. The findings highlight the need for future studies to establish an adequate aPTT range.

Adequate accuracy has not been demonstrated in studies on patients with devices, with the most frequent being in the context of ECMO use. Yuan-Teng et al [

20] found low concor-dance between both tests, both in seconds and in ratio. The aPTT values between 23.2 and 38.7 seconds were considered normal, which were obtained from Werfen. In our cohort, the values of normality in healthy volunteers were higher; therefore, the ratios more adjusted, which would explain why our concordance is better. In another study conducted in patients with V-V ECMO support for ARDS secondary to SARS-Cov-2, low concordance was observed between aPTT-POC and aPTT-lab, with increased concordance when the results were normalized to platelet and creatinine counts. The authors believe that platelets and renal function may influence the outcome of whole blood POC testing [

21].

We identified only one study with satisfactory agreement between laboratory values and those of the bedside test (with HEMOCHRON Jr, International Technidyne Corporation (ITC), Edison, NJ). This study was conducted in the context of heparinization for cardiovas-cular surgery and during the operating room stay5, which differs markedly from our popu-lation of critically ill patients. The correlation found was r = 0.867, p < 0.001.

Methodological differences may partly explain the poor agreement between the POC measurements and the aPTT-lab. The reagents used in POC are phospholipids and kaolin, whereas aPTT-lab uses silicon dioxide, ellagic acid, calcium, and phospholipids. There are also differences in the principles involved in the time-to-clot detection (photoelectric versus viscoelasticity) [

8].

In addition, the POC method uses whole blood, whereas in the laboratory, plasma de- void of white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets is used. This processing of the blood prior to aPTT measurement may eliminate some of the variation and individual influences, particularly those related to platelet count, and therefore may account for some of the differ-rence in results. POC assays are derived from whole blood by calculating aPTT-POC using an algorithm. The results were theoretically calibrated to normal hematocrit and platelet counts. Some manufacturers’ specifications for POC measurements recommend that blood samples with a hematocrit < 20% should not be used for the measurement of aPTTT-POC, as the optical density of the sample exceeds the detection range. different coagulation activators produce different results [

22,

23].

Our study provides important data with respect to previous publications. First, comarisons between determinations were made using the normalized aPTT ratio, obtained by dividing the patient's determination with respect to the mean of determinations of the control group (for the aPPT-POC) and that obtained in the hematology laboratory. These data seem relevant to us, since in our cohort the normality values in seconds are 22 to 31 s for the aPTT-lab, while the normality values for the aPTT-POC (control group) are 39.7 (dt 5.3; min 26- max 45.1), slightly different from those supplied by the manufacturer. Second, this is a prospective study (most studies published to date are retrospective and from databases), and it includes a heterogeneour cohort with the different types of patients that can be found in the ICU and he different support therapies that are currently the main indications for anticoagulation with UFH. Previous studies have tested the measurements in groups of patients subject to greater bias due to the presence of thrombopenia, hemodilution, and multiple transfusions, such as acute hemorrhage and ECMO treatment. Finally, we analyzed several samples that were more than the recommended minimum sample size of 40.

The current study has several limitations. This was a single-center study with a limited number of patients. Some important variables, such as anti-Xa levels and anticoagulation fac-tors, were not available. It was also not possible to monitor the concentration of heparin and its relationship with POC measurements because it was not available at our center.