1. Introduction

Heparin resistant recalcifying solution (HRRS) is a reagent that converts an APTT from a heparin sensitive test to a heparin insensitive one. HRRS is used instead of the regular calcium chloride solution in the second (‘recalcification’) step of an APTT procedure [

1]. Thus, use of HRRS avoids mixing of the included heparin neutralizer during the contact activation stage of the APTT. This is the first published report on HRRS although it has been in use in several German and Australian laboratories for many years, mainly for confirming unexpected heparin contamination in samples.

The anticoagulant activity of heparin has been traditionally monitored with APTT tests [

2]. However, the anti-factor Xa (AXA) activity method is increasingly favoured [

3]. Correlation between the two methods is typically poor, since (i) different APTT reagents have variable sensitivity to heparin; (ii) APTT reagents are also sensitive to other components of the clotting mechanism, including clotting factor activities and with some reagents, presence of lupus anticoagulant (LA); (iii) whereas most of the APTT heparin sensitivity is due to the anti-thrombin (ATA) activity of unfractionated heparin, the AXA assay is instead just sensitive to the anti-FXa activity of heparin [

4].

Discrepancies between APTT and AXA complicate the monitoring of heparin therapy, as potentially applied in many clinical scenarios, and has also concerned many investigators over the years [

5,

6]. Interestingly, discordance between APTTs and AXA-determined heparin levels may also have clinical implications; for example, Jin et al [

7] recently identified discordant high APTTs relative to AXA values in hospitalized patients to be an independent risk factor for increased 30-day mortality.

In the current study, the relationships between various APTT tests, AXA and ATA-based assays for heparin in 163 plasmas from 146 heparinized, mainly cardiology patients were investigated. These included 50 from patients recovering from extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). ECMO represents a lifesaving procedure where cardiac output is circulated outside the body for days, weeks or sometimes even months [

8]. ECMO has become increasingly important during the recent COVID-19 epidemic/ongoing endemic. In addition, tests were also carried out for fibrinogen, antithrombin, factor VIII (FVIII) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels as both acute phase proteins and potential markers of complications and bleeding. Further analysis of results may be reported separately.

2. Materials and Methods

Plasma samples (163) were obtained from 146 patients, most of whom had undergone cardiology procedures that included ECMO and who were recovering. Those with initial APTT results on freshly collected plasma 20% or more above the upper limit of normal were selected for inclusion in this laboratory study. All patients were on unfractionated heparin, but some may have been on additional medications which were not well documented. At least 17 were on Argatroban as identified by relatively high antithrombin activity. The project has been approved by the research and development department at Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust as a service evaluation on and given project ID number 4686.

Blood samples were mainly collected from in-dwelling catheters after appropriate saline flushing into 0.109M sodium citrate (1:9 with whole blood). Others by clean venepuncture into regular citrate Vacutainer tubes (Sarstedt, Numbrecht, Germany). They were processed as recommended by ICSH (9) with double centrifugation, then aliquoted and frozen at -80C until analysis. Samples were semi-blinded for the forensic analysis of laboratory results.

APTT tests were carried out with both Synthasil (Werfen/IL, USA) and Actin FS (Siemens, Germany) reagents, (although only results with Synthasil are reported here) on an Werfen ACL Top 750 CTS coagulometer. APTT tests were performed using the 0.020M CaCl2 recalcifying solution supplied with Synthasil and also using heparin resistant recalcifying solution (HRRS, AntiHepCaTM, Haematex, Sydney, 1). Results from the latter test are denoted APTT-HR. An APTT “Correction Ratio” (CR) was defined as an initial APTT (sec) divided by the APTT-HR (sec).

Heparin activities were determined with chromogenic assay kits based on thrombin inhibition (Hyphen BioMed, France) for ATA and similarly based on factor Xa inhibition (Siemens, Germany) for AXA. Both assays were carried out on the ACL Top 750 CTS. Chromogenic assays for factor VIII were carried out using a Siemens kit also on the same ACL machine.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Findings

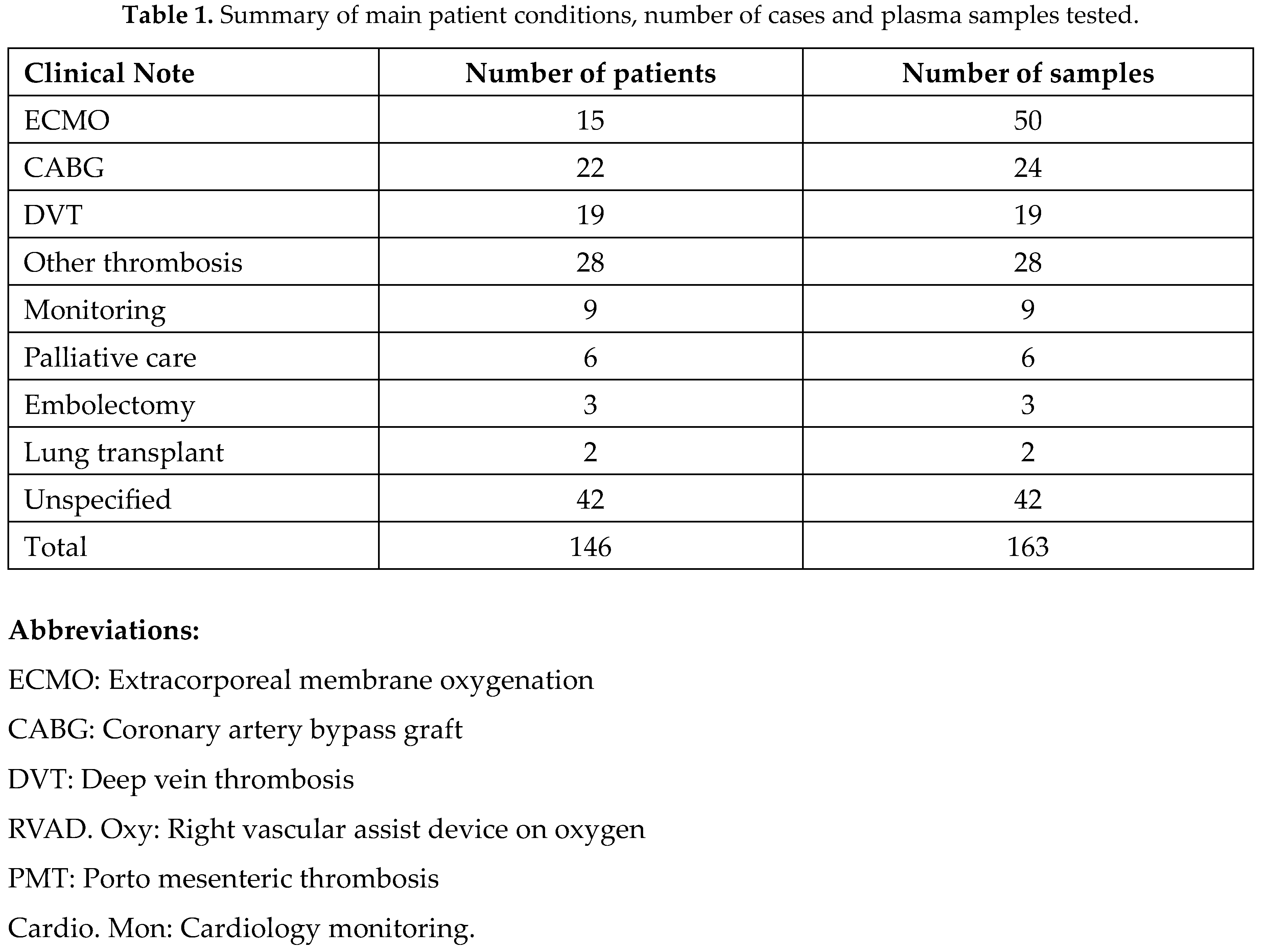

Basic clinical details of the 146 patients from whom the 163 samples were drawn are shown in Table 1. The majority of samples were from patients recovering from extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) procedures and had declining heparin levels over time. Several samples were obtained from some individual patients at varying times depending on their clinical condition.

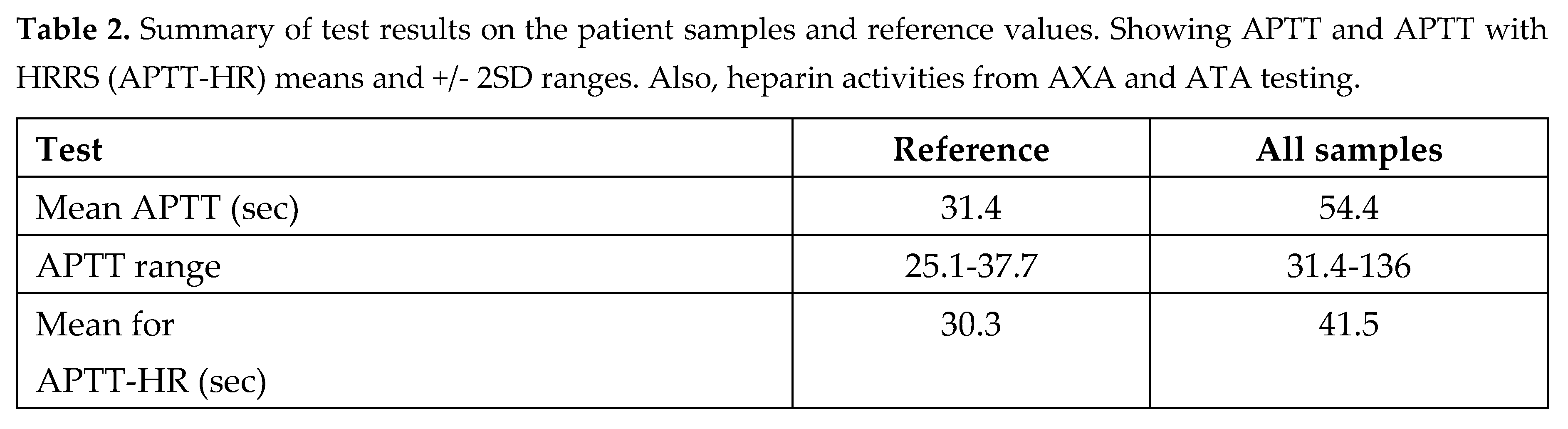

APTT results and normal ranges with and without heparin resistant recalcifying solution (HRRS) are summarized in Table 2. This also shows overall results of the heparin tests with chromogenic anti thrombin assay (ATA) and anti Xa assays (AXA).

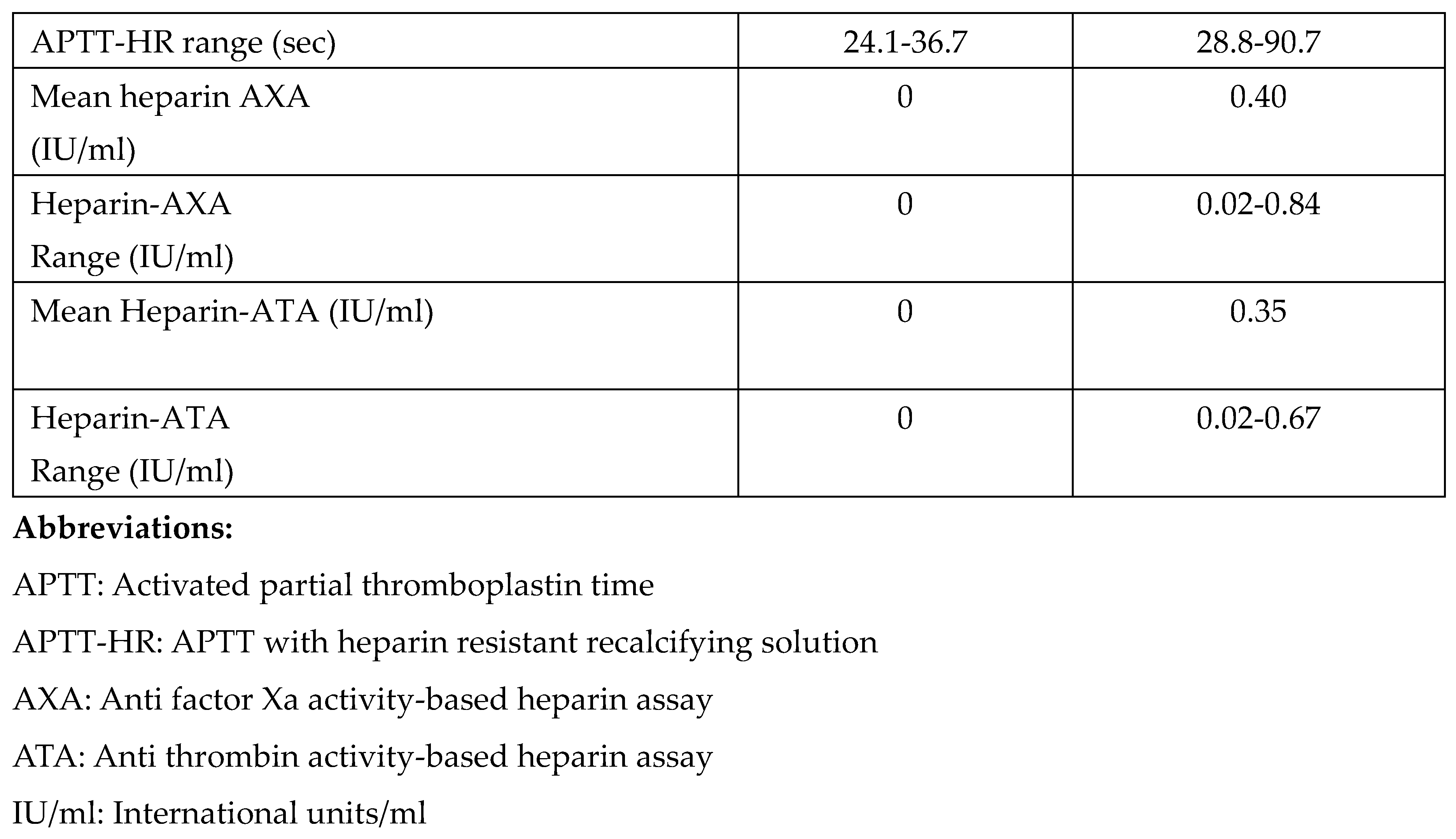

APTT results from the majority of samples (147/163) were shortened by the use of HRRS as might be expected following heparin neutralization. However, there was significant variation in degree of shortening. There were 15 samples in which the APTT was unexpectedly prolonged by HRRS to varying degrees. Overall results were assigned into 3 main groups as shown in

Figure 1.

Group A: Full correction:

These plasmas had APTT correcting back to within the normal range (25.1 - 36.7sec) when re-tested with HRRS. There were 67/163 (41%) such cases. Some details for the 10 cases with longest initial APTTs are shown in

Table 3. These were from well-heparinised patients with no other obvious APTT-prolonging defect. This group included 22 cases where the APTT had normalised to below 37.7 sec after freeze thawing without any assistance from HRRS. All fresh plasma samples initially had APTT 20% above the normal upper limit before freezing for storage and later testing.

Group B: Partial correction:

These plasmas had significant APTT shortening with HRRS while not correcting completely back to within the normal range. These were speculated to be patients with heparin in their plasmas as well as some additional APTT-prolonging defect. There were 81 (50%) such cases.

Basic lab results on the 10 most abnormal cases with APTT-HR above 50sec are shown in

Table 4. There was only 1 case with relatively low factor VIII (<77%) and 9 cases with some other undefined cause for prolonged APTT.

Group C: No correction:

These 15 samples did not correct and paradoxically displayed a small prolongation in APTT after testing with HRRS. These were expected to be patients with little or no heparin and some other defect. Some details of these cases are shown in

Table 5. Results therein are arranged in order of increasingly abnormal initial APTT in column 1.

Heparin activities were quite low according to AXA below 0.2IU/ml, especially with longer APTTs where low factor VIII (<77%) was found in 13 of the 15 cases. The longest APTT results were associated with lowest factor VIII and AXA heparin activities. There were 2 plasmas with high ATA, presumably due to argatroban. Other plasmas with high ATA activities but low AXA representative of argatroban did not display unusually long APTTs.

Comparison of regular APTT and heparin activity test results

The correlation between the standard APTT results and AXA activity on all 163 plasmas tested is shown in

Figure 2. As expected, the correlation was poor at 0.15 (p<0.05).

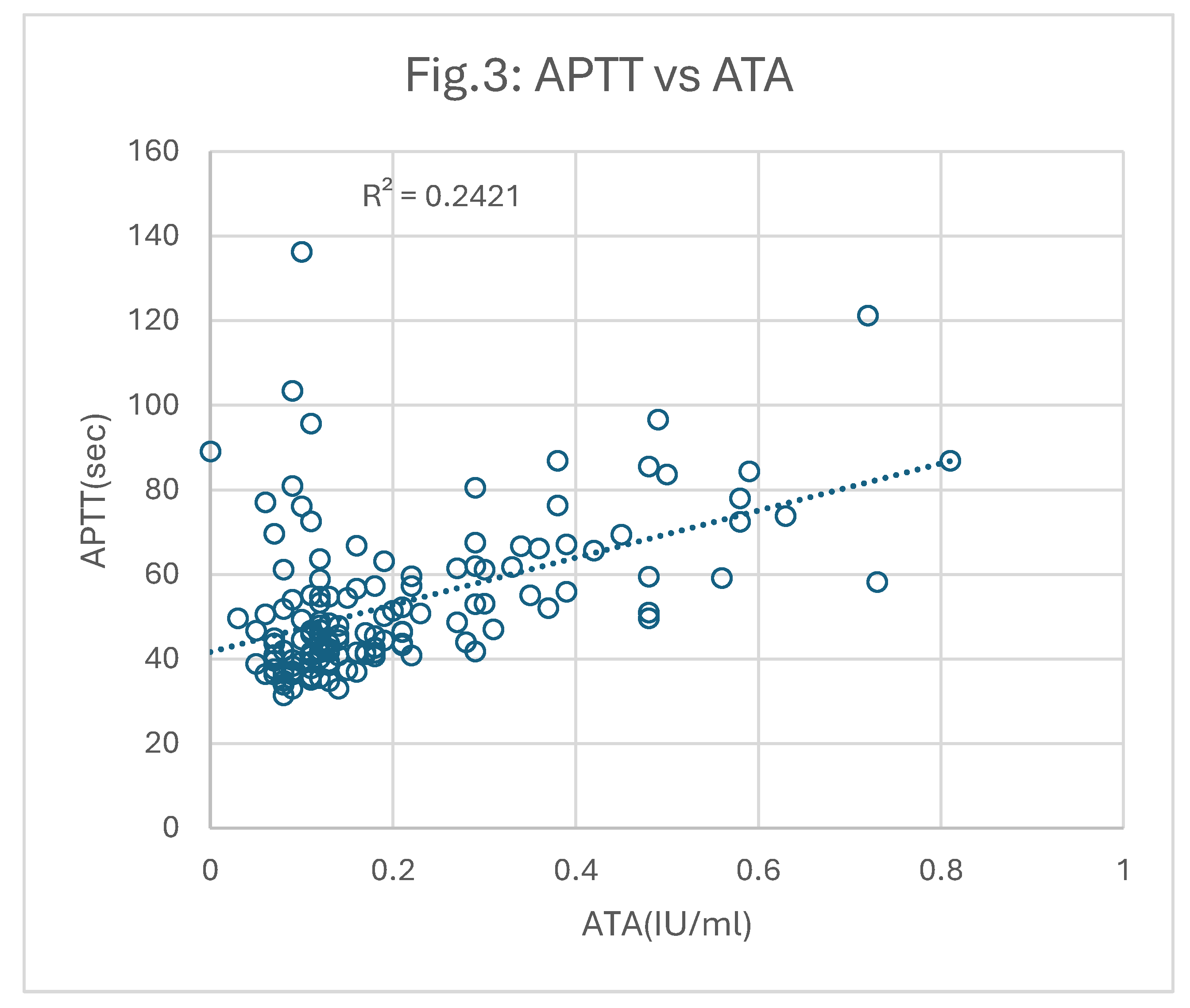

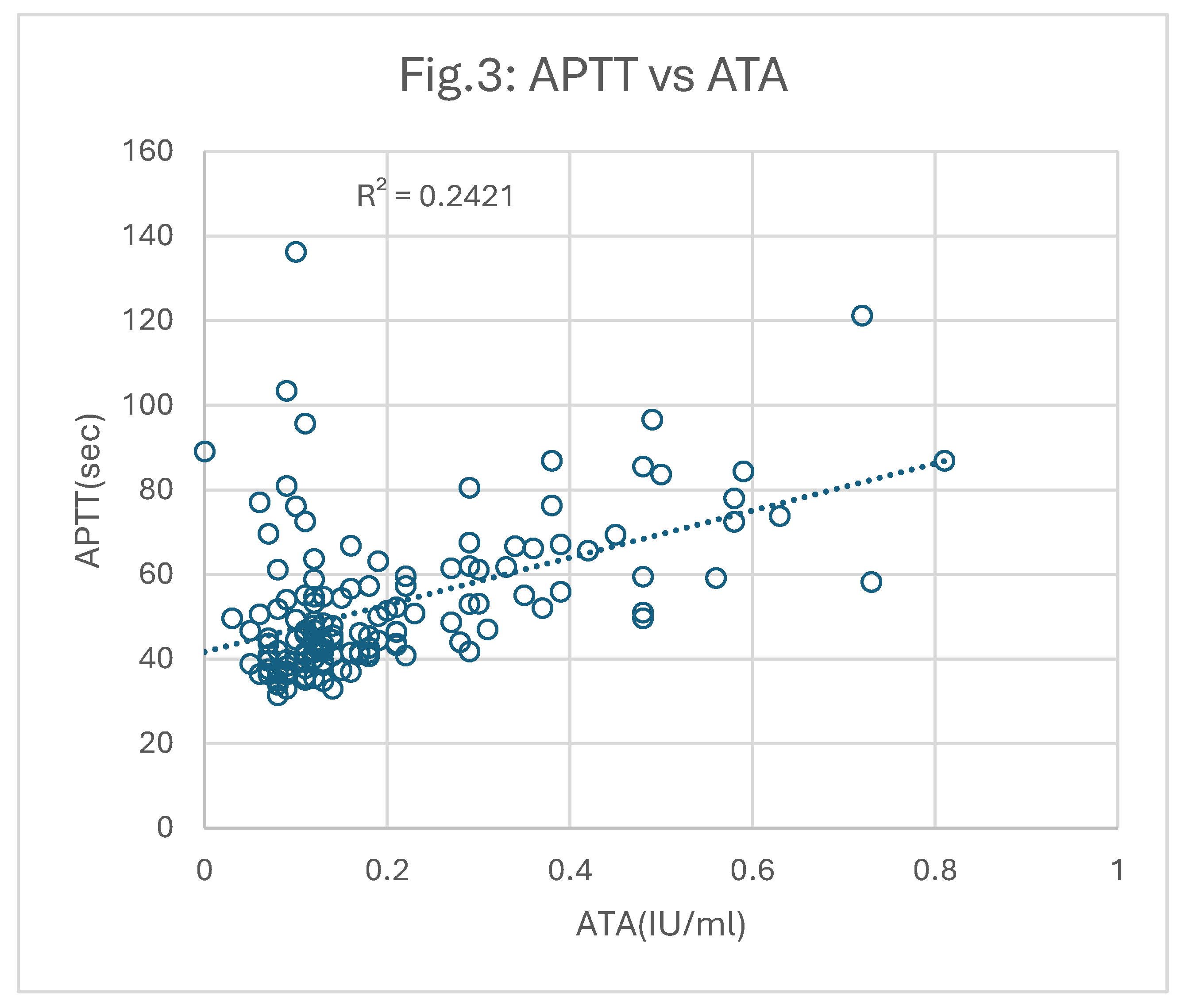

ATA tests were similarly performed on all patient samples. However, 17 gave ATA above 1.0IU/ml likely due to the presence of argatroban. These were excluded from the correlation plot shown in

Figure 3. The correlation between the remaining 136 results for APTT versus ATA was 0.24 (p<0.05), which is still poor, but slightly better than that against AXA.

In both comparisons, APTT vs AXA or ATA, there were 26 samples that gave much longer APTT results than expected from their corresponding ATA or AXA activities. These cases contributed most to the poor correlations and were associated with relatively low factor VIII levels.

Outcome of APTT-HR testing and improved correlation of test results

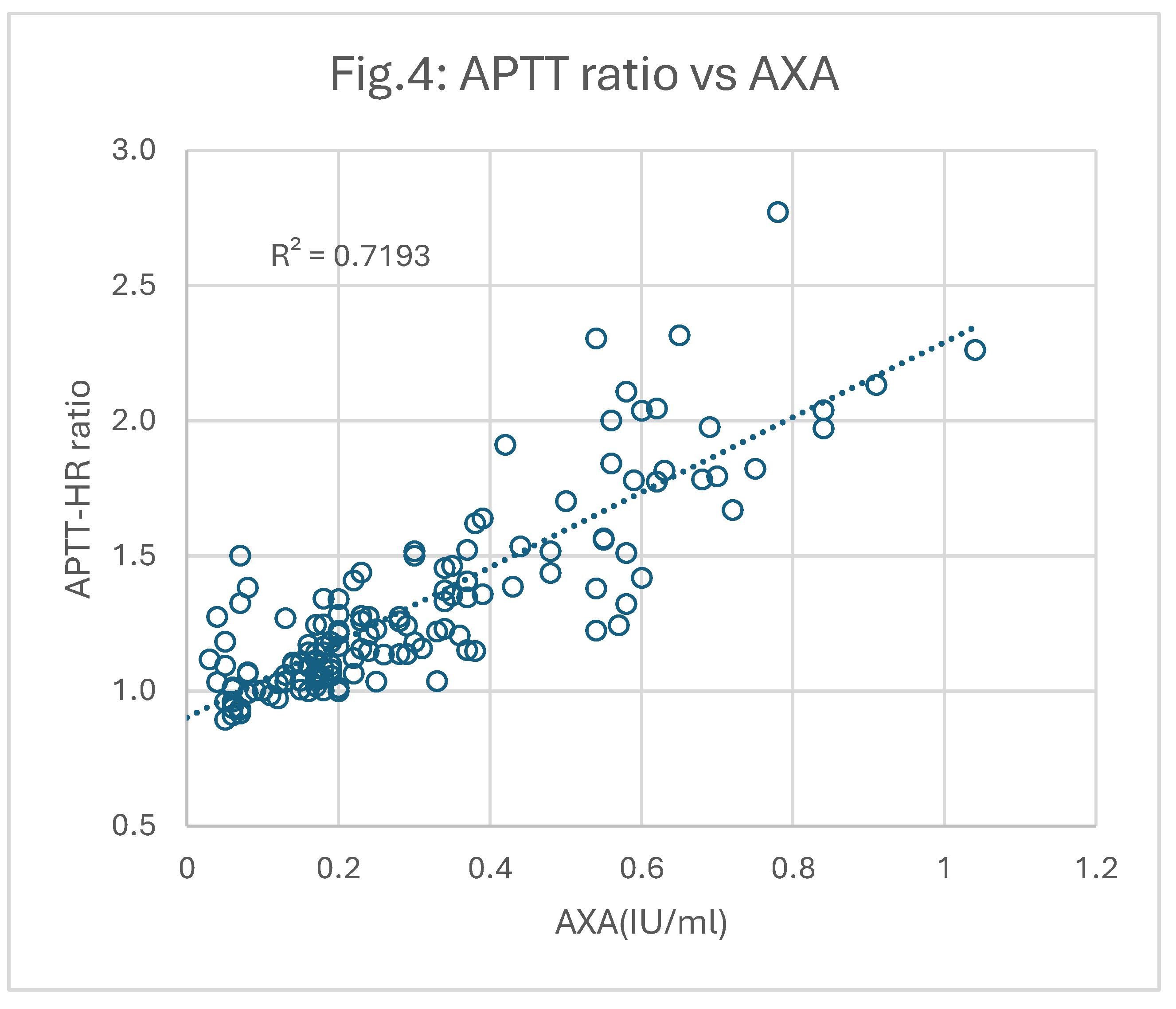

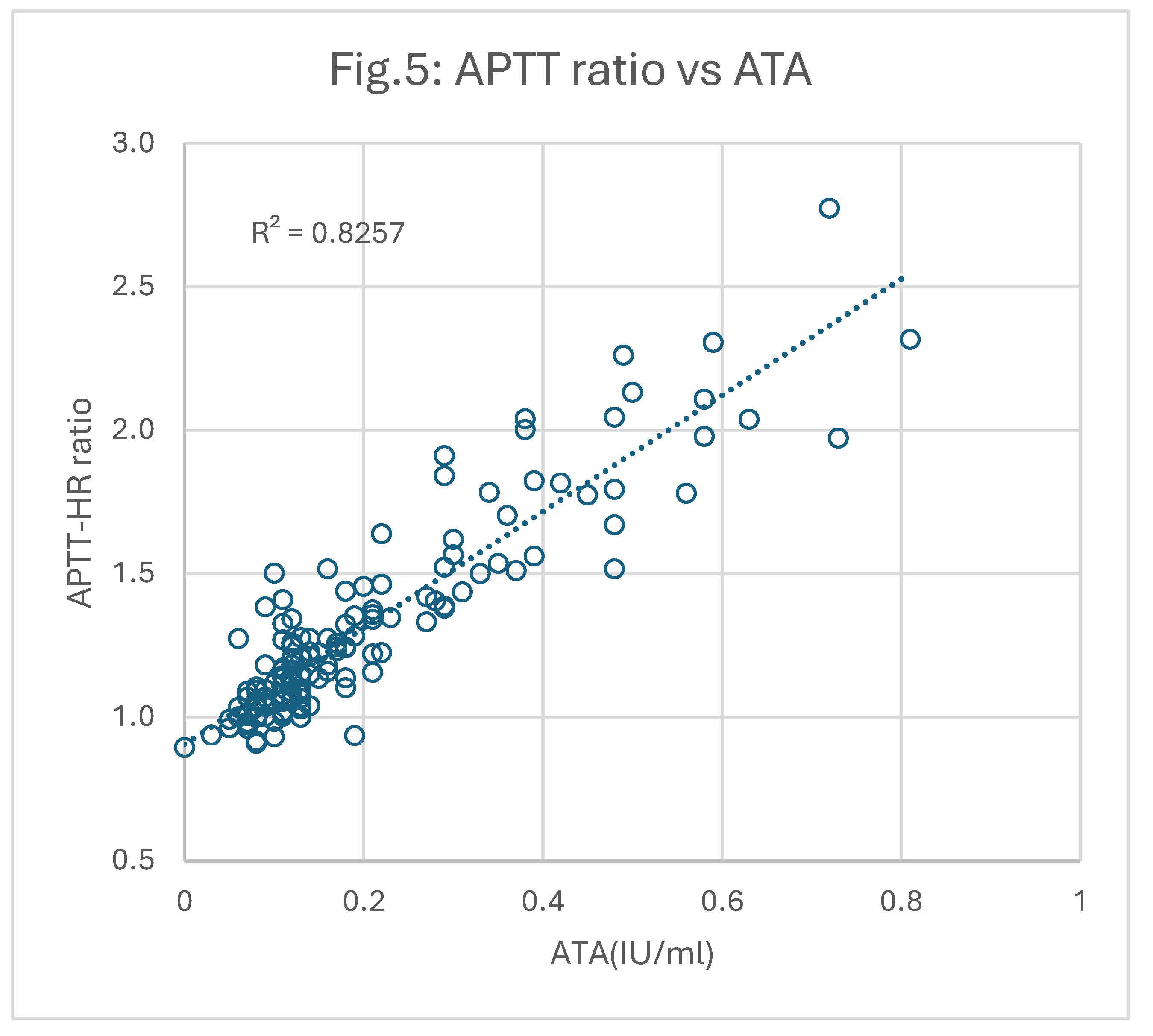

All plasmas were re-tested for APTT using HRRS instead of the regular calcium chloride. Each result was then used to calculate a “Correction Ratio (CR)” of the original APTT relative to the APTT after HRRS (APTT-HR). These correction ratios were then plotted against AXA and ATA as shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 respectively.

It is apparent that the correlations between CR and AXA (0.72; p<0.05) and CR and ATA (0.83; p<0.05) were significantly better than those derived using the original APTT results.

Identification of underlying defects

After the use of HRRS there were 26/163 plasmas with APTT-HR above 50sec suggesting a defect in an APTT-dependent factor. Of these only 12 had FVIII below 77%. Thus 14 had some other defect which was not investigated.

Overall, there were also 26/163 plasmas with FVIII below 77%. Only 12 of these had APTT-HR above 50sec thus suggesting that low FVIII is poorly detected by APTT-HR in such cases.

There were no unusual findings from tests of fibrinogen, CRP or antithrombin.

4. Discussion

The APTT is currently regarded as a somewhat unreliable test for monitoring heparin [

2,

4,

5,

10,

15,

20]. Our analysis of results from this study supports that belief but may also provide an improvement. APTT results analysed in this study confirm that HRRS reagent can be used in place of standard CaCl

2 reagent to provide APTT tests relatively insensitive to heparin. Then pairing this modified APTT assay (APTT-HR) test with the standard APTT provides information on the patient’s status additional to that available from the initial APTT result.

This process can provide a more accurate heparin measurement through use of the HRRS APTT Correction Ratio and an appropriate calibration curve than the initial APTT. It may also identify haemostasis abnormalities that may compound or synergise with heparin to generate very long APTT results. This may then identify patients at risk of bleeding, a potential clinical problem which was not followed up in this analysis.

The 163 samples represent a typical heterogenous group submitted for coagulation testing in the modern era. The patients varied widely in their clinical condition, heparin treatments and coagulation factor levels. This investigation focussed on comparing APTT results for heparin with various test methods. There were a few technical concerns.

Despite using recommended preanalytical conditions and double centrifuging [

9], a significant shortening of APTT results was observed in most cases after freezing test plasma samples. This was possibly due to activation of residual platelets and release of platelet factor 4 which may have induced heparin resistance. Possibly also activation of other factors.

The chromogenic ATA and AXA results may have been less affected than the APTTs by this problem. It is probable that better correlations of APTT with ATA or AXA might have been obtained with fresh plasma samples. However, as with most such studies, samples were batched frozen for convenience and more accurate testing at a later time. It has also been noted that chromogenic ATA and AXA kits can vary in their assessment of heparins [

10].

Heparin neutralizers such as protamine and polybrene have frequently been added to test plasma samples to overcome heparin before testing (11). Also, to some coagulation reagents such as thrombin time, prothrombin time and dilute Russells viper venom time reagents, at low concentrations so they have little effect on their own. However, cationic neutralizers cannot be added to most APTT reagents or indiscriminately to plasmas because the conventional contact activators such as silica, kaolin and ellagic acid are all negatively charged compounds and may be reduced in activity by positively charged agents [

11]. It is possible to titrate a correct amount of neutralizer into a test plasma but this is a tedious procedure [

12].

Heparin adsorbing agents such as ECTEOLA cellulose can be used as a pre-treatment but may induce changes in some clotting factors [

11]. Best current practice is to use heparinase enzyme to enzymatically degrade heparin [

13]. One advantage of HRRS over heparinase is that it is used with much smaller sample volumes, doesn’t need incubation and can be applied on instruments directly replacing the regular calcium chloride. HRRS works well with most APTT reagents, although not optimally with Synthasil [

1] which was used in this study. This may be because a 0.020M calcium chloride is normally used with Synthasil (IL/Werfen) whereas HRRS is currently based on 0.025M calcium chloride concentration.

Factor VIII was below an arbitrary 77% cutoff in only a few cases (26/163) and did not correlate well with prolonged APTT-HR results. Factor VIII activities in this study overall seemed to be unusually high but a similar increase was noted by Streng et al [

15] and others after ECMO in COVID patients. Investigations for other factor deficiencies were not carried out. Lupus anticoagulant (LA) was looked for by comparing the Synthasil APTT results with those obtained with Actin FS which was assumed to be less sensitive to LA. No evidence was found for LA which would have been difficult to detect anyway given the activated state of most samples. Argatroban was also not readily detectable from Synthasil APTT-HR.

Our main finding is that correction ratios correlated better with heparin by AXA or ATA than the initial APTTs. This is probably not surprising because CR applies a variation compensating for any underlying defect in the test plasma in addition to the heparin effect. In our results the correlation between heparin by ATA and CR was 0.83 which is almost good enough for interpolation of patient values. A similar proposal to use APTT ratios was made previously by van den Besselaar et al (16) who used ECTEOLA cellulose to obtain heparin-depleted plasma samples and thereby derive APTT ratios. The correlation coefficients between log (APTT-ratio) and anti Xa or anti IIa activities in that study improved significantly to 0.76 and 0.87 respectively over those obtained with simple log APTT. Remarkably similar to our own findings.

The benefit of using APTT correction ratios is similar to that reported previously for the DOAC neutralizer DOAC Stop

TM with DOAC plasma samples [

16]. Initial APTT results divided by the APTTs after treatment with DOAC Stop gave ratios correlating much more closely with DOAC activity than the initial result. Thus, APTT-LA (Diagnostica Stago) versus dabigatran, apixaban and rivaroxaban concentrations were initially poor (0.64, 0.15 and 0.39 respectively). However, they improved to 0.94, 0.89 and 0.80 respectively after the use of correction ratios. Even better correlation improvements to 0.99, 0.97 and 0.95 respectively were obtained after testing with dRVVT Confirm which is more specific and sensitive to DOACs. Since the DOAC-like anticoagulant argatroban is of increasing interest in blood bypass procedures [

17], APTT correction ratios with DOAC Stop might also be useful to provide more reliable argatroban levels in such circumstances.

The APTT is widely used as a screening test for a number of coagulation variables, such as factor deficiency, lupus anticoagulant (LA) detection and assessment of anticoagulant status including unfractionated heparin [

18,

19]. Thus, a single abnormal APTT result on a sample can be interpreted in various ways. If heparin is suspected to be involved, a quick follow-up APTT with HRRS can provide evidence for heparin and help identify other causes of a prolonged result. Chromogenic AXA or ATA can provide specific results for these enzyme inhibitors but cannot provide a “baseline” APTT underlying a patients’ initial result.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

HRRS effectively shortens APTT as a reliable indicator of heparin activity. The APTT Correction Ratio with HRRS correlates better with heparin activity than APTT alone, particularly with ATA. This simple additional test may not only improve heparin monitoring but can also detect underlying conditions unrelated to heparin, thus reducing potential bleeding risks.

Author Contributions

Stephen MacDonald organised and supervised this study. Georgina Attrill arranged all the testing. Manita Dangol analysed the results. Thomas Exner wrote most of the paper. Emmanuel Favaloro contributed to writing and reviewed the submission.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Suzanne Kelly for facilitating this project.

Conflicts of Interest

Thomas Exner and Manita Dangol are employees of Haematex Research, Sydney which manufactures HRRS as AntiHepCaTM. The other authors disclose no conflicts. The study from which these results were obtained was carried out in Cambridge, independently from and without any support from Haematex other than free HRRS samples.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APTT |

Activated partial thromboplastin time |

| APTT-HR |

APTT with heparin resistant recalcifying solution |

| AXA |

Anti factor Xa activity-based heparin assay |

| ATA |

Anti thrombin activity-based heparin assay |

| IU/ml |

International units/ml |

| ECMO |

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| CABG |

Coronary artery bypass graft |

| DVT |

Deep Vein Thrombosis |

| PMT |

Porto mesenteric thrombosis |

| RVAD.Oxy |

Right vascular assist device on oxygen |

| Cardio. Mon |

Cardiology monitoring |

References

- Antihepca™-HRRS. Heparin Resistant Recalcifying Solution. [Online] 2024. [Cited: 21 October 2024.] https://www.haematex.com/haematex-products/antihepca-hrrs.

- Marlar RA, Clement B, Gausman J. Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Monitoring of Unfractionated Heparin Therapy: Issues and Recommendations. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2017; 43: 253-260.

- Favaloro EJ, Kershaw G, Mohammed S, Lippi G. How to Optimize Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT) Testing: Solutions to Establishing and Verifying Normal Reference Intervals and Assessing APTT Reagents for Sensitivity to Heparin, Lupus Anticoagulant, and Clotting Factors. Semin. Thromb Hemost.2019; 45: 22-35.

- Arachchillage DJ, Kitchen S. Pleiotropic Effects of Heparin and its Monitoring in Clinical Practice. Semin Thromb Hemost.2024; 50; 1153-1162.

- Li S, Li A, Beckman JA, Kim C, Granich MA, Mondin J, Sabath DE, Garcia DA, Mahr C. Discordance between aPTT and anti-Xa in monitoring heparin anticoagulation in mechanical circulatory support. ESC Heart Fail. 2024; 11: 2742-2748.

- van Roessel S, Middeldorp S, Cheung YW, Zwinderman AH, de Pont AC. Accuracy of aPTT monitoring in critically ill patients treated with unfractionated heparin. Neth J Med. 2014; 72: 305-10.

- Jin J, Gummidipundi S, Hsu J, Sharifi H, Boothroyd D, Krishnan A, Zehnder JL. Discordant High Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Relative to Anti-Xa Values in Hospitalized Patients is an Independent Risk Factor for Increased 30-day Mortality. Semin Thromb. Hemost. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0044-1789020. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39191408.

- Bartlett R, Arachchillage DJ, Chitlur M, Hui SR, Neunert C, Doyle A, Retter A, Hunt BJ, Lim HS, Saini A, Renné T, Kostousov V, Teruya J. The History of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation and the Development of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Anticoagulation. Semin Thromb. Hemost. 2024; 50: 81-90.

- Kitchen S, Adcock DM, Dauer R, Kristoffersen AH, Lippi G, Mackie I, Marlar RA, Nair S. International Council for Standardization in Haematology (ICSH) recommendations for processing of blood samples for coagulation testing. Int J Lab Hematol. 2021; 43: 1272-1283.

- Toulon P, Smahi M, De Pooter N. APTT therapeutic range for monitoring unfractionated heparin therapy. Significant impact of the anti-Xa reagent used for correlation. J Thromb Haemost. 2021,19: 2002-2006.

- Cumming AM, Jones GR, Wensley RT, Cundall RB. In vitro neutralization of heparin in plasma prior to the activated partial thromboplastin time test: an assessment of four heparin antagonists and two anion exchange resins. Thromb Res. 1986; 1; 41: 43-56.

- Newall F. Protamine titration. Methods Mol Biol. 2013; 992: 279-87.

- van den Besselaar AM, Meeuwisse-Braun J. Enzymatic elimination of heparin from plasma for activated partial thromboplastin time and prothrombin time testing. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1993; 4: 635-8.

- Exner T, Favresse J, Lesire S, Douxfils J, Mullier F. Clotting test results correlate better with DOAC concentrations when expressed as a “Correction Ratio”; results before/after extraction with DOAC Stop reagent. Thromb. Res. 2019; 179: 69-72.

- Streng AS, Delnoij TSR, Mulder MMG, Sels JWEM, Wetzels RJH, Verhezen PWM, Olie RH, Kooman JP, van Kuijk SMJ, Brandts L, Ten Cate H, Lorusso R, van der Horst ICC, van Bussel BCT, Henskens YMC. Monitoring of Unfractionated Heparin in Severe COVID-19: An Observational Study of Patients on CRRT and ECMO. TH Open. 2020; 19: 4: e365-e375.

- van den Besselaar AM, Meeuwisse-Braun J, Bertina RM. Monitoring heparin therapy: relationships between the activated partial thromboplastin time and heparin assays based on ex-vivo heparin samples. Thromb Haemost. 1990; 63:16-23.

- Aubron C, Chapalain X, Bailey M, Board J, Buhr H, Cartwright B, Dennis M, Hodgson C, Forrest P, McIlroy D, Murphy D, Murray L, Pellegrino V, Pilcher D, Sheldrake J, Tran H, Vallance S, Cooper DJ, McQuilten Z. Anti-Factor-Xa and Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time Concordance and Outcomes in Adults Undergoing Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Secondary Analysis of the Pilot Low-Dose Heparin in Critically Ill Patients Undergoing Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Randomized Trial. Crit Care Explor. 2023; 8; 5(11): e0999.

- Geli J, Capoccia M, Maybauer DM, Maybauer MO. Argatroban Anticoagulation for Adult Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Systematic Review. J Intensive Care Med. 2022; 37: 459-471.

- Rajsic S, Treml B, Jadzic D, Breitkopf R, Oberleitner C, Bachler M, Bösch J, Bukumiric Z. aPTT-guided anticoagulation monitoring during ECMO support: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. 2023; 77:154332.

- Vandiver JW, Vondracek TG. Antifactor Xa levels versus activated partial thromboplastin time for monitoring unfractionated heparin. Pharmacotherapy. 2012; 32: 546-58.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).