Submitted:

23 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Power Analysis

Language Background and Self-Reported Proficiency

Objective Proficiency Verification

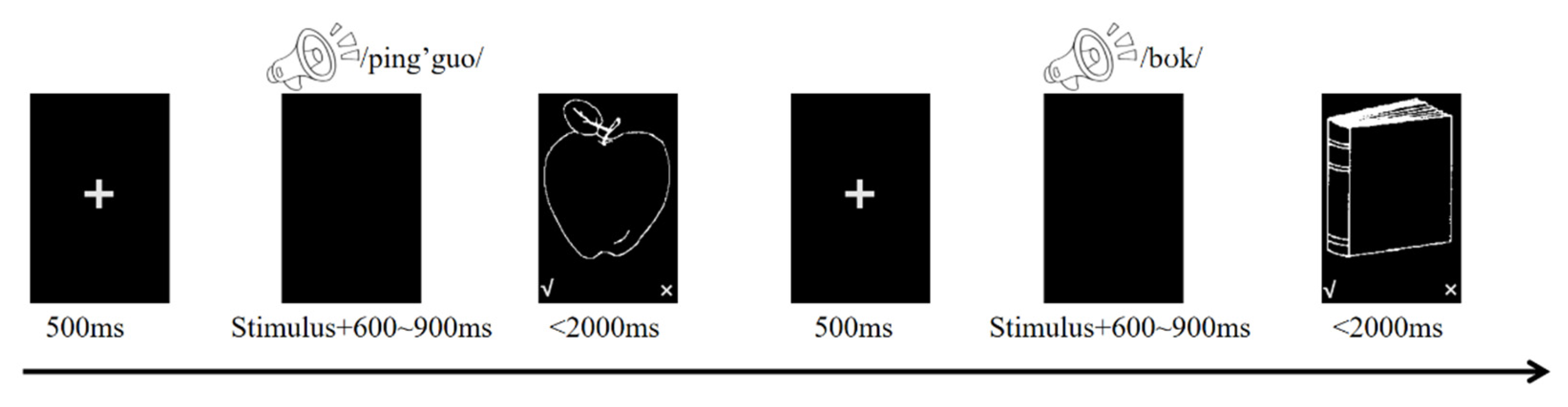

2.2. Materials and Procedure

Experimental Design

2.3. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

EEG Recording

Preprocessing

2.4. Data Analyses

2.4.1. Behavioral Analysis

2.4.2. Event-Related Potential (ERP) Analysis

2.4.3. Multivariate Pattern Analysis (MVPA)

2.4.4. Drift-Diffusion Model (DDM) Analysis

2.4.5. Multiple Regression Linking ERPs and DDM

3. Results

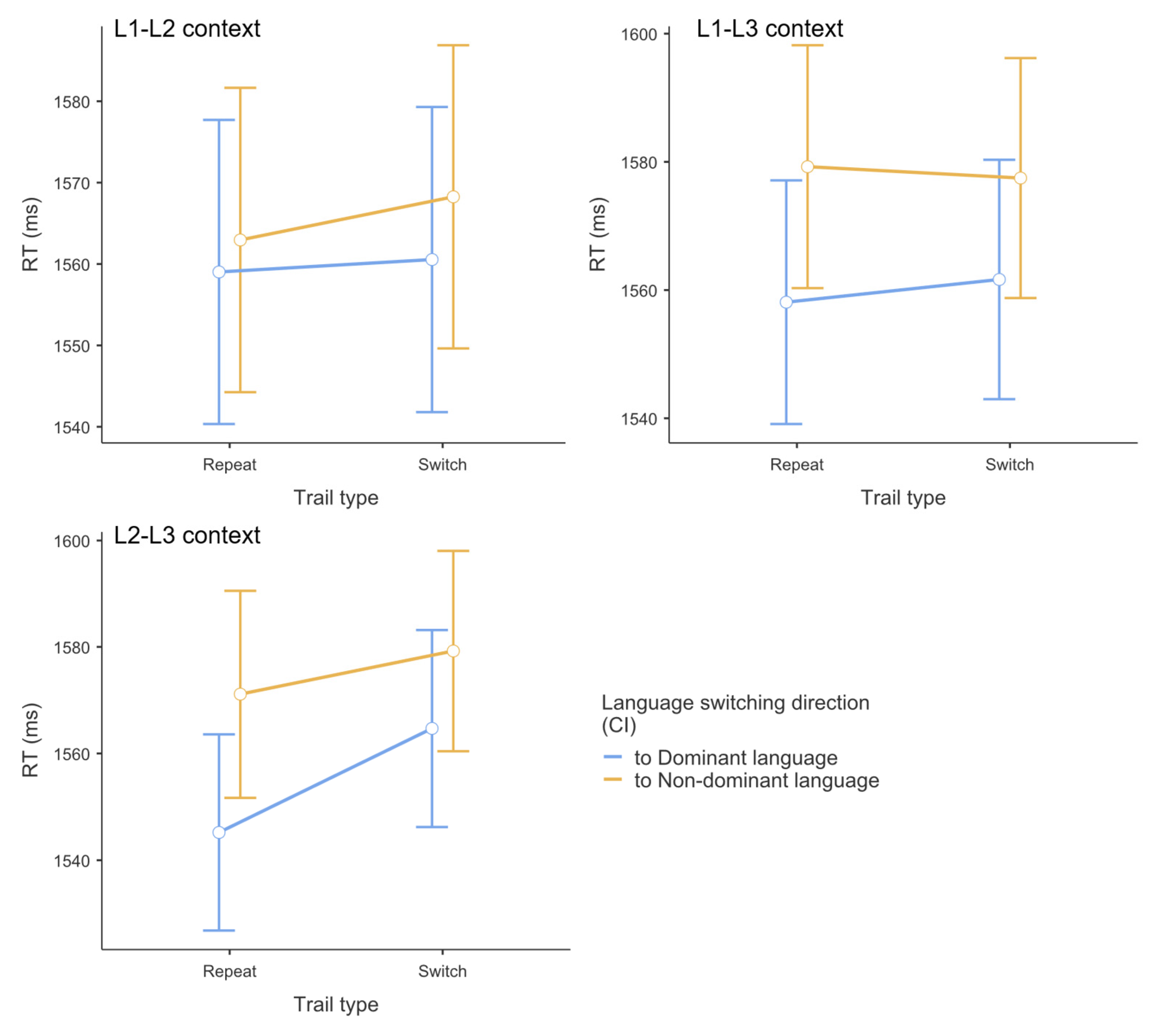

3.1. Results of Reaction Time Data

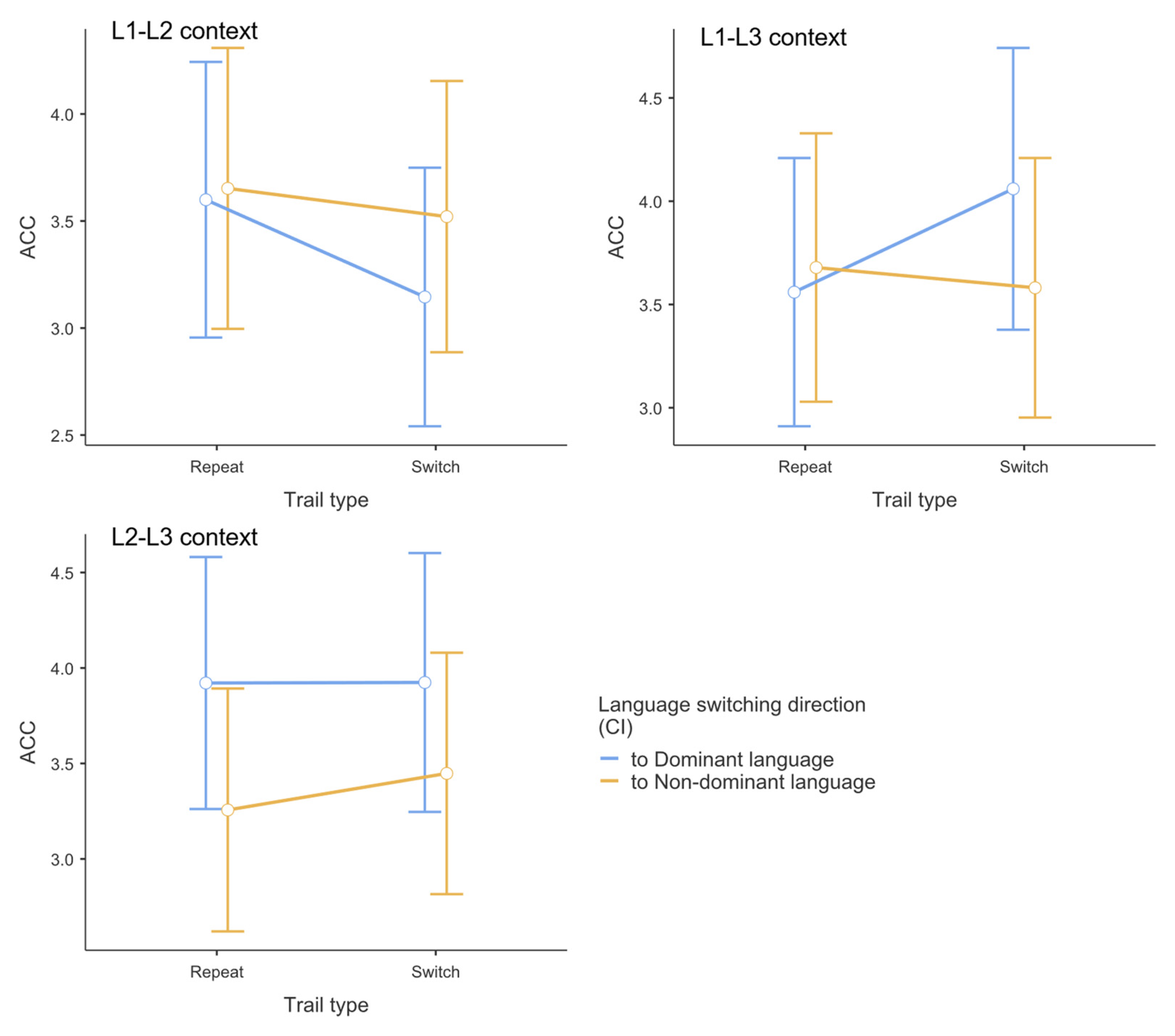

3.2. Results of Accuracy Data

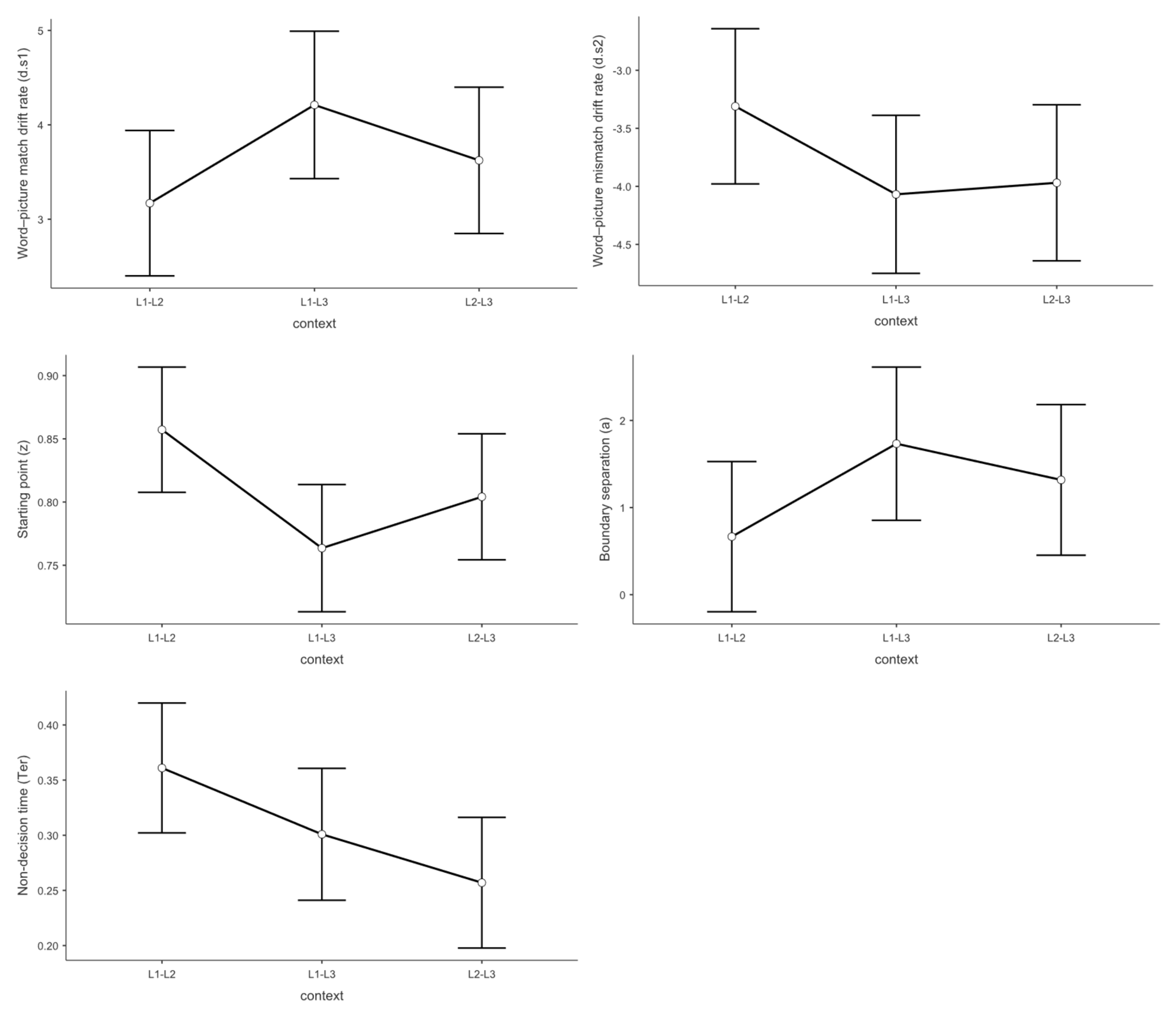

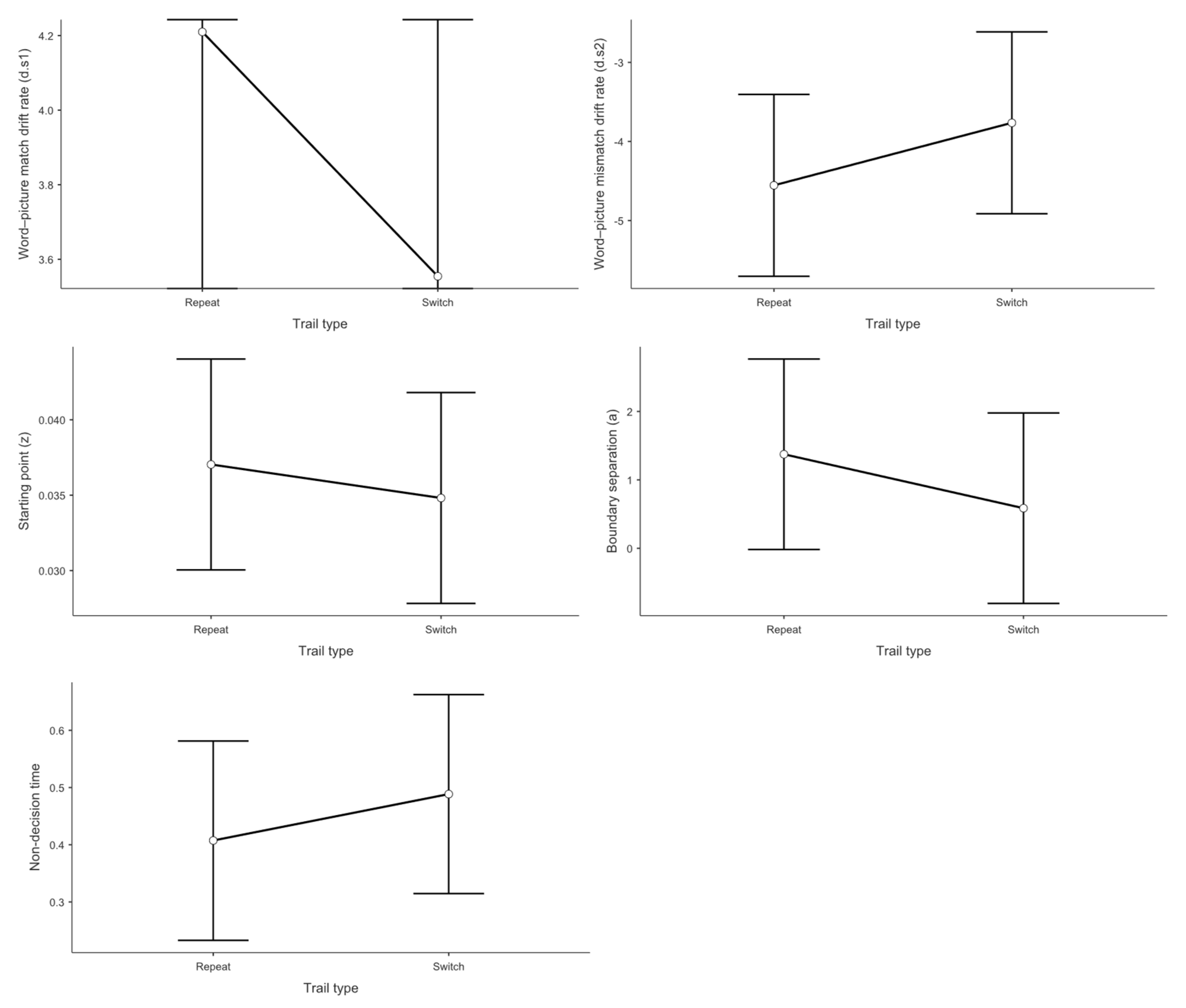

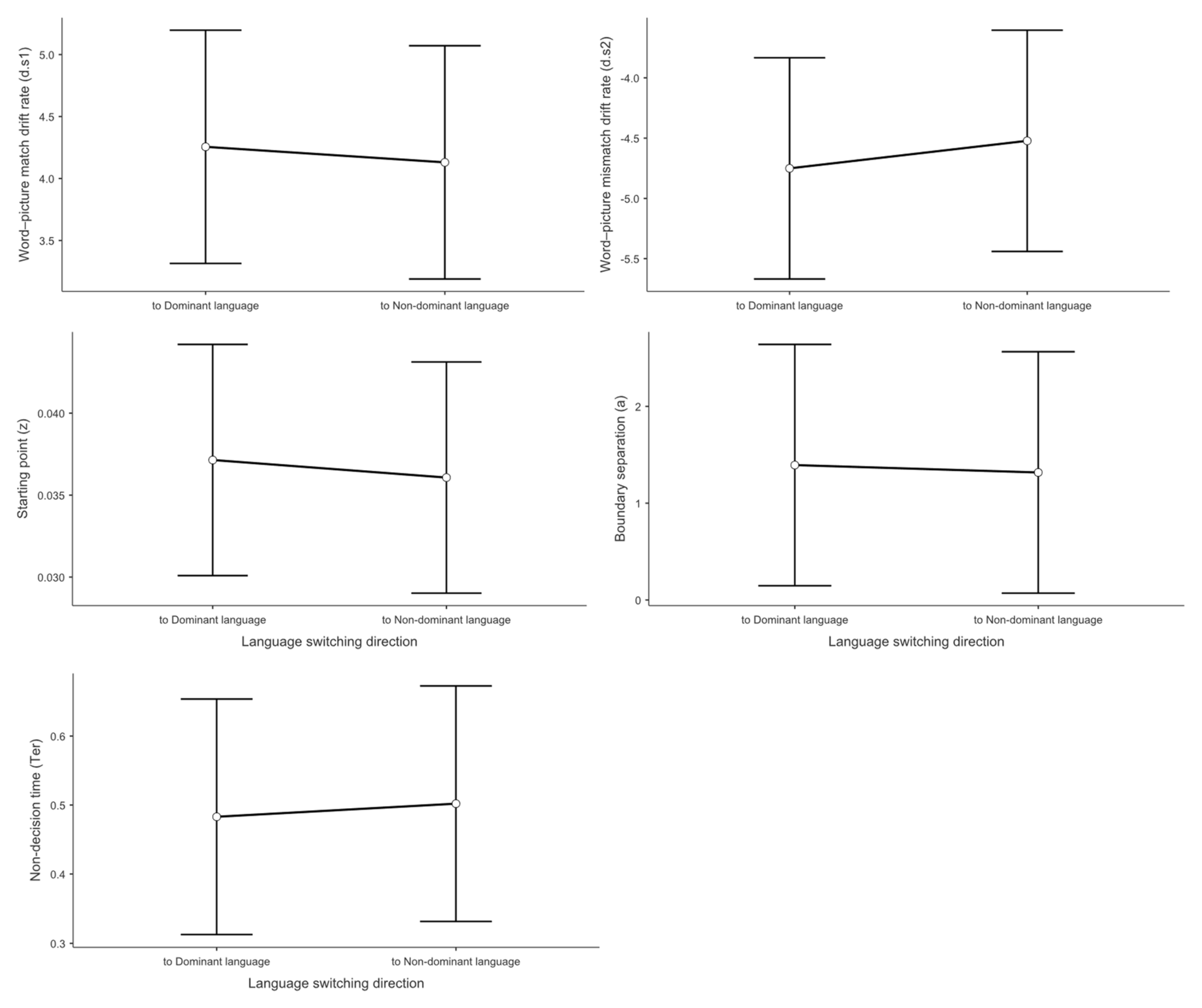

3.3. Drift Diffusion Model Results

3.3.1. Drift Rate Analysis for Match Responses (d.s1)

3.3.2. Drift Rate Analysis for Mismatch Responses (d.s2)

3.3.3. Starting Point Analysis (Response Bias)

3.3.4. Boundary Separation Analysis (Decision Threshold)

3.3.5. Non-Decision Time Analysis (Motor and Encoding Processes)

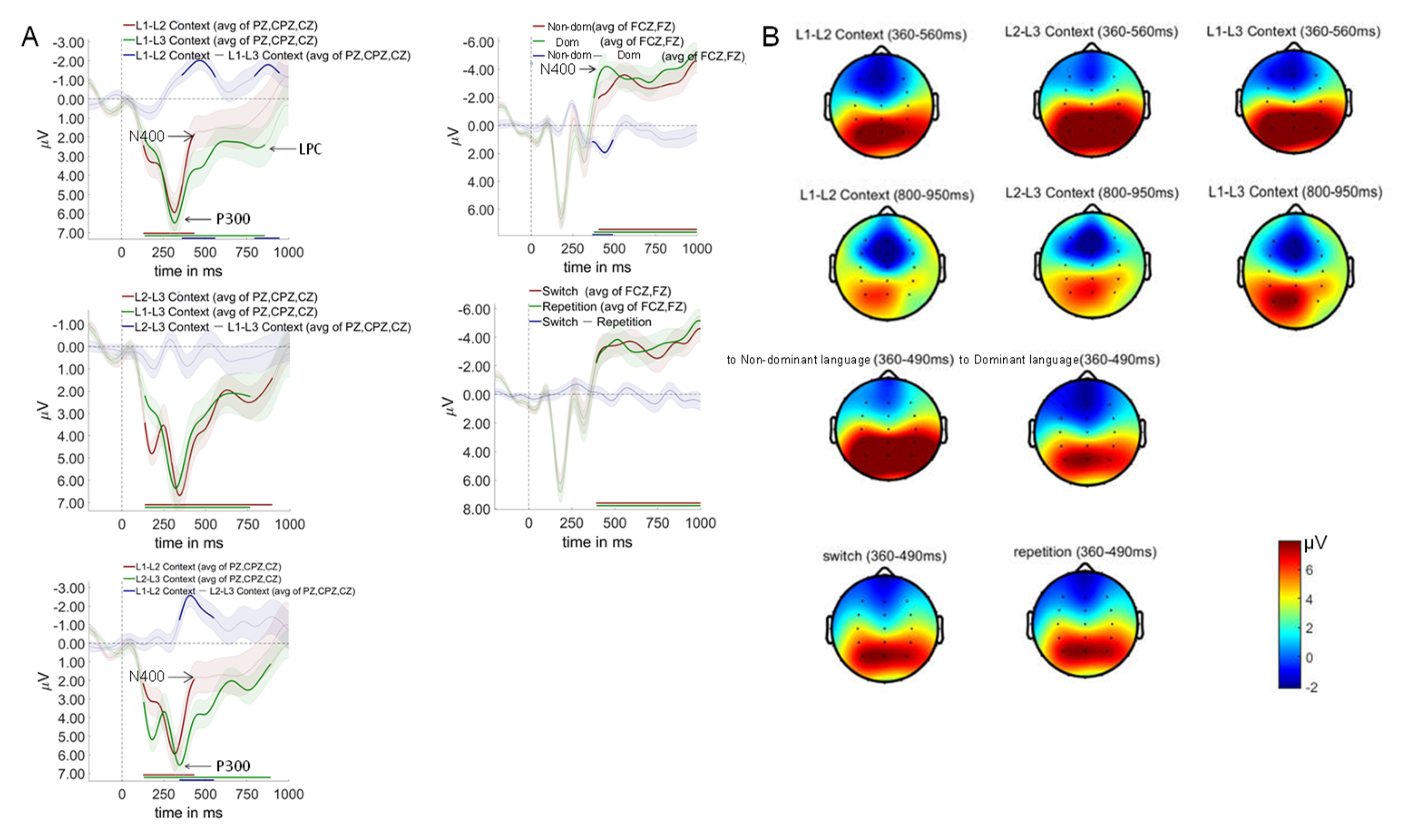

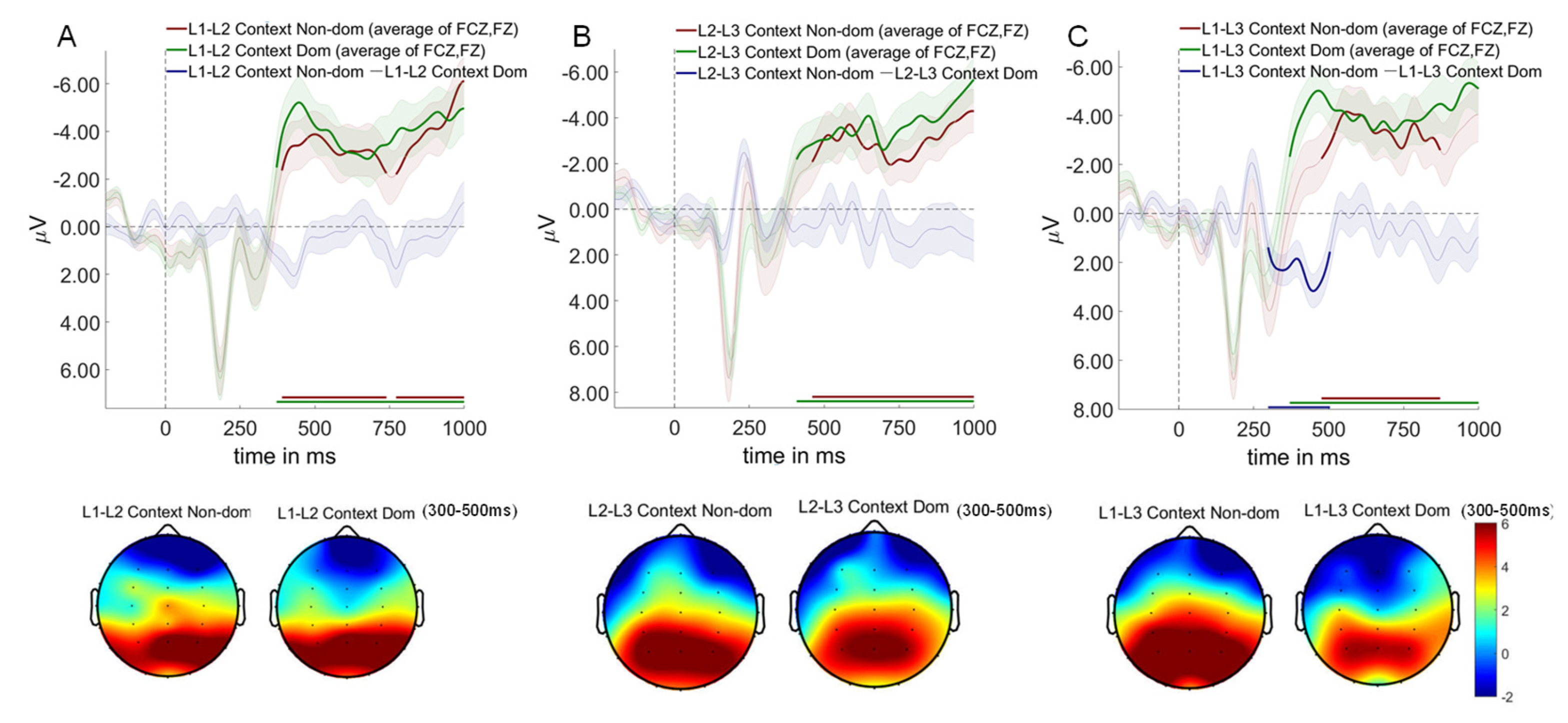

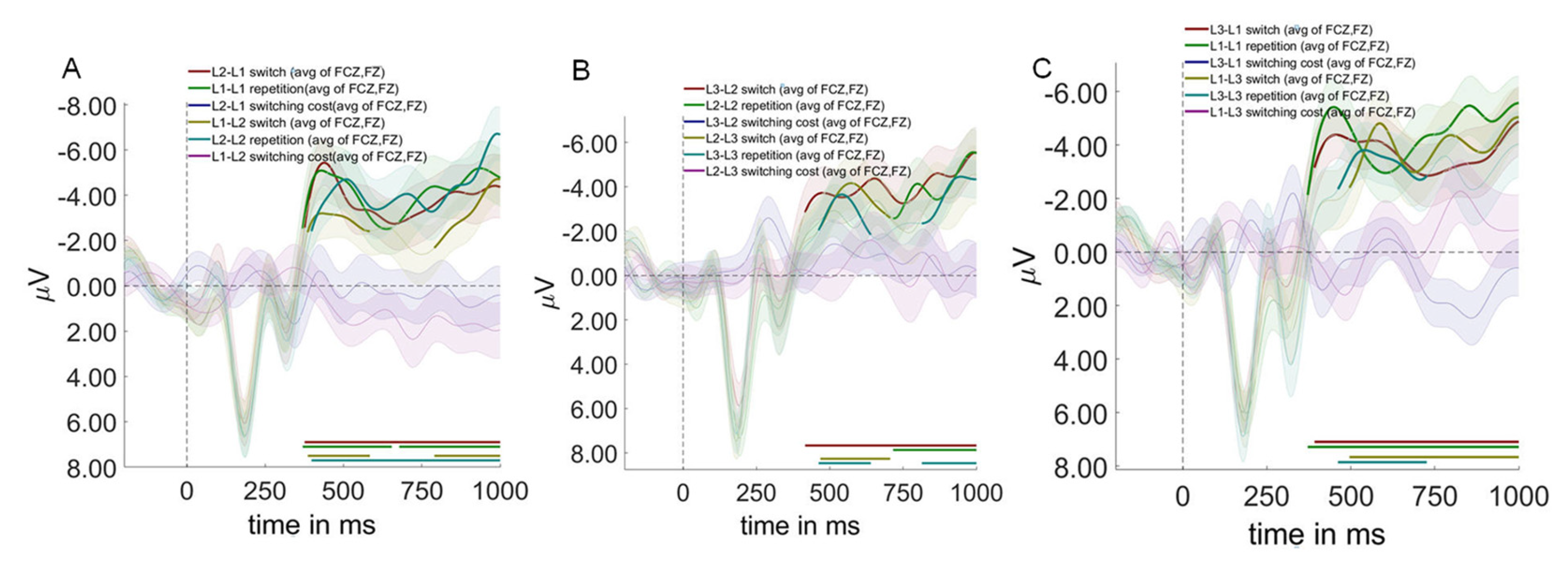

3.4. ERP Results

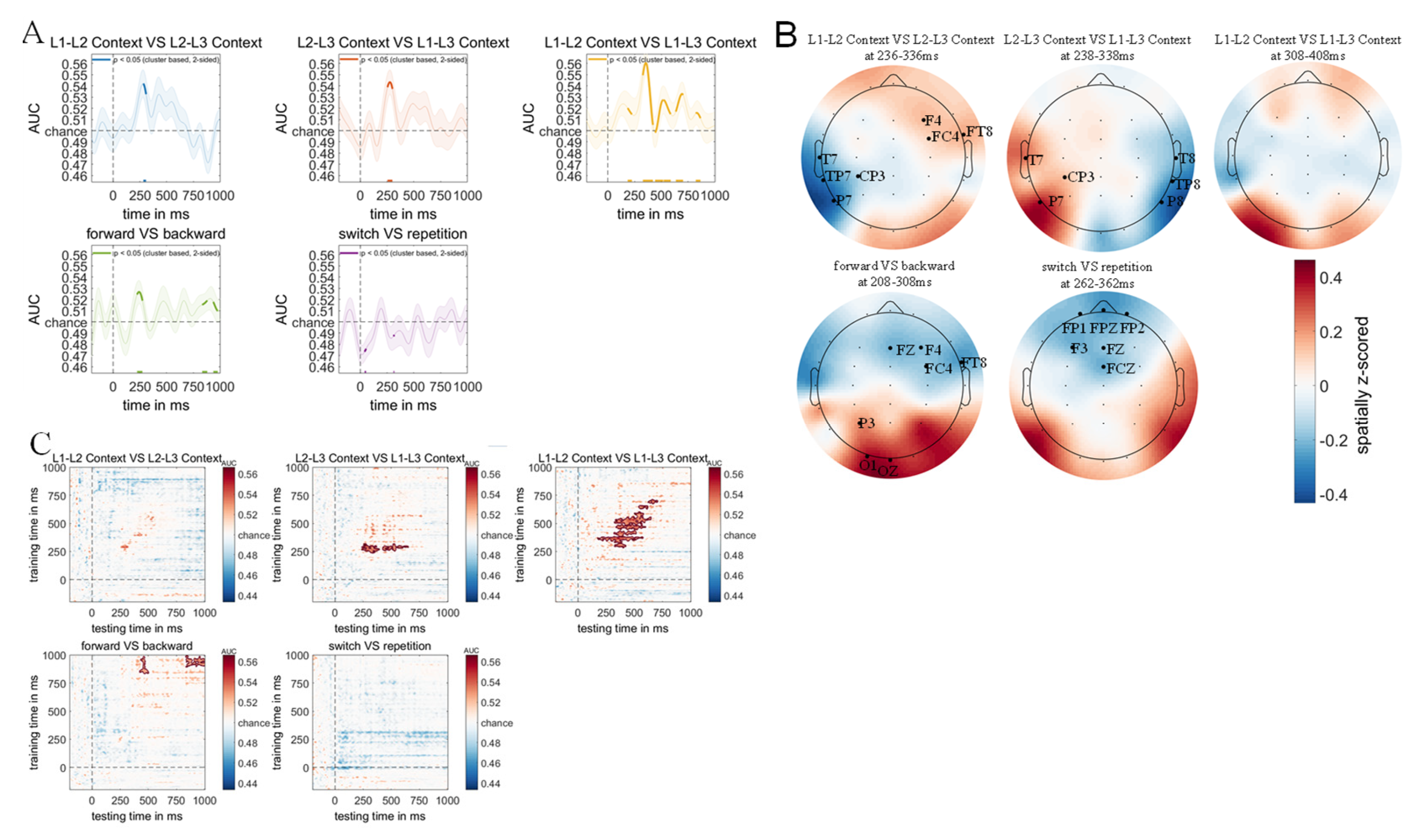

3.5. Multivariate Pattern Analysis Results

3.5.1. Diagonal Decoding Results

3.5.2. Weight Projection Analysis Results

3.5.3. Temporal Generalization Using Classification Across Time result

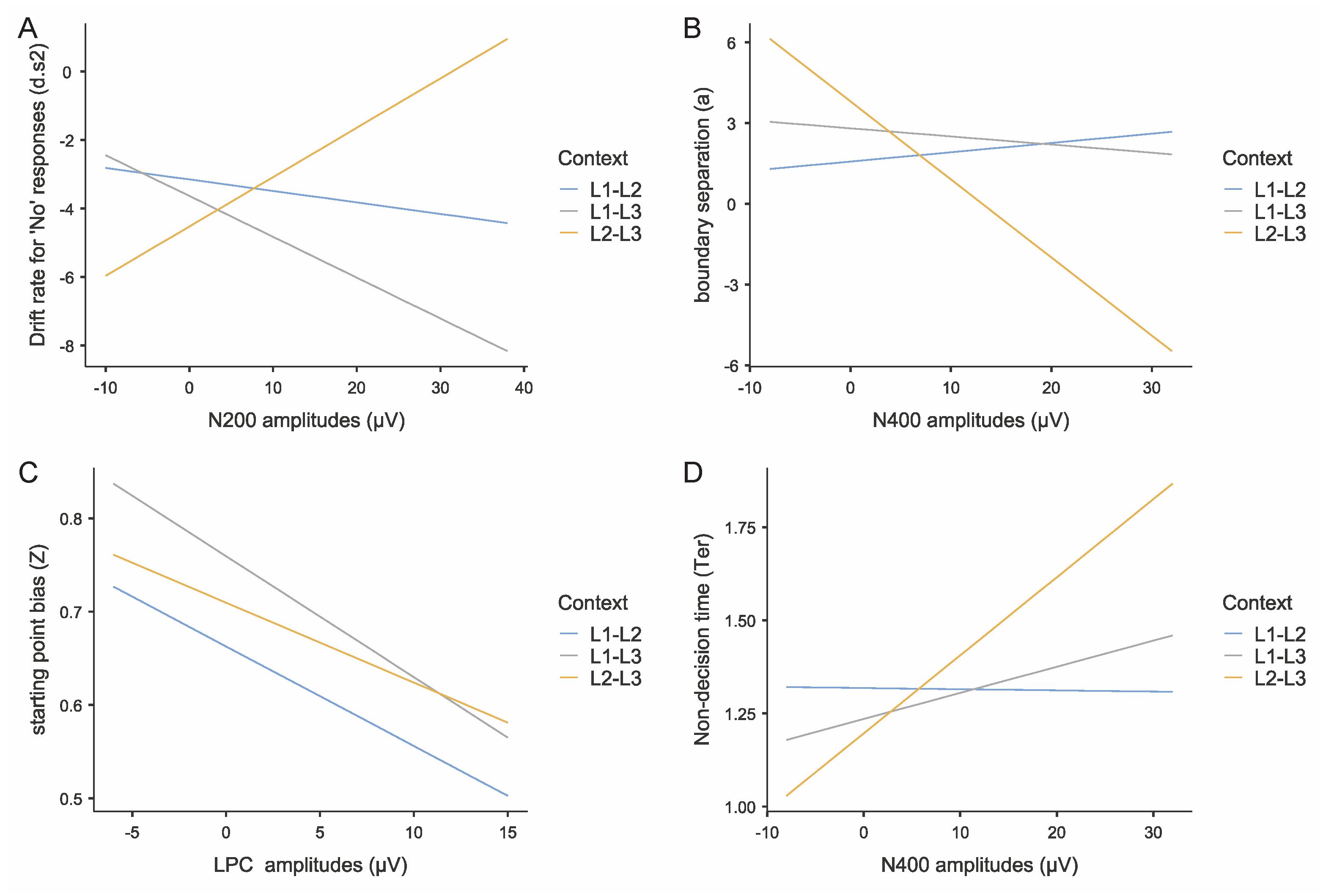

3.5.4. Multiple Regression Analysis of ERP Data and Drift Diffusion Model Parameters

4. Discussion

4.1. Language Comprehension Efficiency Across Dual-Language Contexts

4.2. The Demands of Proactive Control in Different Dual-Language Contexts

4.3. The Demands of Reactive Control in Different Dual-Language Contexts

4.4. Neural Computations of Language Control Across Dual-Language Contexts

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bilingualism in the US, UK & Global Statistics. Available online: https://preply.com/en/blog/bilingualism-statistics/ (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Thierry, G. and Y.J. Wu, Brain potentials reveal unconscious translation during foreign-language comprehension. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2007. 104(30): p. 12530-12535. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., How do L3 words find conceptual parasitic hosts in typologically distant L1 or L2? Evidence from a cross-linguistic priming effect. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 2020. 23(10): p. 1238-1253. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., et al., Examining sources of language production switch costs amongst Tibetan-Chinese-English trilinguals. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 2024. 27(8): p. 1153-1167. [CrossRef]

- Declerck, M. and I. Koch, The concept of inhibition in bilingual control. Psychological Review, 2023. 130(4): p. 953. [CrossRef]

- Grainger, J., K. Midgley, and P. Holcomb, Re-thinking the bilingual interactive-activation model from a developmental perspective (BIA-d). In M. Kail & M. Hickmann (Eds.), Language Acquisition across Linguistic and Cognitive Systems. 2010, Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Jiao, L., et al., The contributions of language control to executive functions: From the perspective of bilingual comprehension. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 2019. 72(8): p. 1984-1997. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., et al., Distinct language control mechanisms in speech production and comprehension: evidence from N-2 repetition, switching, and mixing costs. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 2025: p. 1-17.

- Van Heuven, W.J., T. Dijkstra, and J. Grainger, Orthographic neighborhood effects in bilingual word recognition. Journal of memory and language, 1998. 39(3): p. 458-483. [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T. and W.J. Van Heuven, The architecture of the bilingual word recognition system: From identification to decision. Bilingualism: Language and cognition, 2002. 5(3): p. 175-197.

- Declerck, M. and J. Grainger, Inducing asymmetrical switch costs in bilingual language comprehension by language practice. Acta Psychologica, 2017. 178: p. 100-106. [CrossRef]

- Orfanidou, E. and P. Sumner, Language switching and the effects of orthographic specificity and response repetition. Memory & Cognition, 2005. 33(2): p. 355-369. [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, X. and J.-M. Lavaur, Recognising words in three languages: Effects of language dominance and language switching. International Journal of Multilingualism, 2014. 11(2): p. 164-181. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, P., M. Declerck, and I. Koch, Exploring the functional locus of language switching: Evidence from a PRP paradigm. Acta psychologica, 2015. 161: p. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Declerck, M., et al., Highly proficient bilinguals implement inhibition: Evidence from n-2 language repetition costs. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 2015. 41(6): p. 1911. [CrossRef]

- Declerck, M. and A.M. Philipp, Is inhibition implemented during bilingual production and comprehension? n-2 language repetition costs unchained. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 2018. 33(5): p. 608-617. [CrossRef]

- Green, D.W. and J. Abutalebi, Language control in bilinguals: The adaptive control hypothesis. Journal of cognitive psychology, 2013. 25(5): p. 515-530. [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Elorrieta, E. and L. Pylkkänen, Bilingual language switching in the laboratory versus in the wild: The spatiotemporal dynamics of adaptive language control. Journal of Neuroscience, 2017. 37(37): p. 9022-9036. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. and H. Liu, The effect of the non-task language when trilingual people use two languages in a language switching experiment. Frontiers in Psychology, 2020. 11: p. 754. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y., Y. Lee, and K. Nam, The different P200 effects of phonological and orthographic syllable frequency in visual word recognition in Korean. Neuroscience letters, 2011. 501(2): p. 117-121. [CrossRef]

- Maurer, U., D. Brandeis, and B.D. McCandliss, Fast, visual specialization for reading in English revealed by the topography of the N170 ERP response. Behavioral and brain functions, 2005. 1(1): p. 13. [CrossRef]

- Declerck, M., et al., The other modality: Auditory stimuli in language switching. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 2015. 27(6): p. 685-691. [CrossRef]

- Ong, G., et al., Diffusing the bilingual lexicon: Task-based and lexical components of language switch costs. Cognitive Psychology, 2019. 114: p. 101225. [CrossRef]

- Declerck, M. and A.M. Philipp, A review of control processes and their locus in language switching. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 2015. 22(6): p. 1630-1645. [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T. and W.J. Van Heuven, The BIA model and bilingual word recognition, in Localist connectionist approaches to human cognition. 2013, Psychology Press. p. 189-225.

- Hut, S.C., et al., Language control mechanisms differ for native languages: Neuromagnetic evidence from trilingual language switching. Neuropsychologia, 2017. 107: p. 108-120. [CrossRef]

- Declerck, M., et al., What absent switch costs and mixing costs during bilingual language comprehension can tell us about language control. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 2019. 45(6): p. 771. [CrossRef]

- Green, D.W., Mental control of the bilingual lexico-semantic system. Bilingualism: Language and cognition, 1998. 1(2): p. 67-81. [CrossRef]

- Brysbaert, M., How many participants do we have to include in properly powered experiments? A tutorial of power analysis with reference tables. Journal of cognition, 2019. 2(1): p. 16. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., et al., Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior research methods, 2009. 41(4): p. 1149-1160. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.A., et al., The language and social background questionnaire: Assessing degree of bilingualism in a diverse population. Behavior research methods, 2018. 50(1): p. 250-263. [CrossRef]

- Tomoschuk, B., V.S. Ferreira, and T.H. Gollan, When a seven is not a seven: Self-ratings of bilingual language proficiency differ between and within language populations. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 2019. 22(3): p. 516-536. [CrossRef]

- Gollan, T.H., et al., Self-ratings of spoken language dominance: A Multilingual Naming Test (MINT) and preliminary norms for young and aging Spanish–English bilinguals. Bilingualism: language and cognition, 2012. 15(3): p. 594-615. [CrossRef]

- Szekely, A., et al., A new on-line resource for psycholinguistic studies. Journal of memory and language, 2004. 51(2): p. 247-250. [CrossRef]

- Delorme, A. and S. Makeig, EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. Journal of neuroscience methods, 2004. 134(1): p. 9-21. [CrossRef]

- Bates, D., et al., Package ‘lme4’. convergence, 2015. 12(1): p. 2.

- Kroll, J.F., et al., Language selection in bilingual speech: Evidence for inhibitory processes. Acta psychologica, 2008. 128(3): p. 416-430. , . [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.L., C. Selinger, and S.D. Pollak, P300 as a measure of processing capacity in auditory and visual domains in specific language impairment. Brain research, 2011. 1389: p. 93-102. [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, P.J. and H.J. Neville, Auditory and visual semantic priming in lexical decision: A comparison using event-related brain potentials. Language and cognitive processes, 1990. 5(4): p. 281-312. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, E.M., A. Rodríguez-Fornells, and M. Laine, Event-related potentials (ERPs) in the study of bilingual language processing. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 2008. 21(6): p. 477-508. [CrossRef]

- Fahrenfort, J.J., et al., From ERPs to MVPA using the Amsterdam decoding and modeling toolbox (ADAM). Frontiers in neuroscience, 2018. 12: p. 368. [CrossRef]

- Haufe, S., et al., On the interpretation of weight vectors of linear models in multivariate neuroimaging. Neuroimage, 2014. 87: p. 96-110. [CrossRef]

- King, J.-R. and S. Dehaene, Characterizing the dynamics of mental representations: the temporal generalization method. Trends in cognitive sciences, 2014. 18(4): p. 203-210.

- Heathcote, A., et al., Dynamic models of choice. Behavior research methods, 2019. 51(2): p. 961-985.

- Turner, B.M., et al., A method for efficiently sampling from distributions with correlated dimensions. Psychological methods, 2013. 18(3): p. 368. [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.-H., et al., Systematic parameter reviews in cognitive modeling: Towards a robust and cumulative characterization of psychological processes in the diffusion decision model. Frontiers in psychology, 2021. 11: p. 608287. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.P. and A. Gelman, General methods for monitoring convergence of iterative simulations. Journal of computational and graphical statistics, 1998. 7(4): p. 434-455.

- Holm, S., A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian journal of statistics, 1979: p. 65-70.

- Wu, Y.J. and G. Thierry, Fast modulation of executive function by language context in bilinguals. Journal of Neuroscience, 2013. 33(33): p. 13533-13537. [CrossRef]

- Kałamała, P., et al., The use of a second language enhances the neural efficiency of inhibitory control: An ERP study. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 2022. 25(1): p. 163-180. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X., G. Schafer, and P.M. Riddell, Immediate auditory repetition of words and nonwords: an ERP study of lexical and sublexical processing. PloS one, 2014. 9(3): p. e91988. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., et al., Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the right inferior frontal gyrus impairs bilinguals’ performance in language-switching tasks. Cognition, 2025. 254: p. 105963. [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, I. and J.P. Rauschecker, Phoneme and word recognition in the auditory ventral stream. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2012. 109(8): p. E505-E514. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M., et al., FMRI reveals brain regions mediating slow prosodic modulations in spoken sentences. Human brain mapping, 2002. 17(2): p. 73-88. [CrossRef]

- Van Petten, C. and M. Kutas, Interactions between sentence context and word frequencyinevent-related brainpotentials. Memory & cognition, 1990. 18(4): p. 380-393.

- Palmer, S.D., J.C. van Hooff, and J. Havelka, Language representation and processing in fluent bilinguals: Electrophysiological evidence for asymmetric mapping in bilingual memory. Neuropsychologia, 2010. 48(5): p. 1426-1437. [CrossRef]

- Ludersdorfer, P., et al., Left ventral occipitotemporal activation during orthographic and semantic processing of auditory words. Neuroimage, 2016. 124: p. 834-842. [CrossRef]

- Abutalebi, J. and D.W. Green, Neuroimaging of language control in bilinguals: neural adaptation and reserve. Bilingualism: Language and cognition, 2016. 19(4): p. 689-698. [CrossRef]

- Botvinick, M.M., J.D. Cohen, and C.S. Carter, Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: an update. Trends in cognitive sciences, 2004. 8(12): p. 539-546. [CrossRef]

- Donkers, F.C. and G.J. Van Boxtel, The N2 in go/no-go tasks reflects conflict monitoring not response inhibition. Brain and cognition, 2004. 56(2): p. 165-176.

- van Steenbergen, H., G.P. Band, and B. Hommel, Does conflict help or hurt cognitive control? Initial evidence for an inverted U-shape relationship between perceived task difficulty and conflict adaptation. Frontiers in Psychology, 2015. 6: p. 974. [CrossRef]

- Ecke, P., Parasitic vocabulary acquisition, cross-linguistic influence, and lexical retrieval in multilinguals. Bilingualism: language and cognition, 2015. 18(2): p. 145-162. [CrossRef]

- Ecke, P. and C.J. Hall, The Parasitic Model of L2 and L3 vocabulary acquisition: evidence from naturalistic and experimental studies. Fórum Linguístico, 2014. 11(3): p. 360-372.

- Ortu, D., K. Allan, and D.I. Donaldson, Is the N400 effect a neurophysiological index of associative relationships? Neuropsychologia, 2013. 51(9): p. 1742-1748.

- Todorova, L., D.A. Neville, and V. Piai, Lexical-semantic and executive deficits revealed by computational modelling: a drift diffusion model perspective. Neuropsychologia, 2020. 146: p. 107560. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., et al., Electrophysiological evidence for domain-general inhibitory control during bilingual language switching. PloS one, 2014. 9(10): p. e110887. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., et al., Late positive complex in event-related potentials tracks memory signals when they are decision relevant. Scientific reports, 2019. 9(1): p. 9469. [CrossRef]

- Todorova, L. and D.A. Neville, Associative and identity words promote the speed of visual categorization: A hierarchical drift diffusion account. Frontiers in Psychology, 2020. 11: p. 955. [CrossRef]

- Tiedt, H.O., F. Ehlen, and F. Klostermann, Age-related dissociation of N400 effect and lexical priming. Scientific reports, 2020. 10(1): p. 20291. [CrossRef]

- Declerck, M., D. Kleinman, and T.H. Gollan, Which bilinguals reverse language dominance and why? Cognition, 2020. 204: p. 104384. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | L1 Uyghur | L2 Chinese | L3 English |

| Age of acquisition (years) M (SD) | 0.68 (1.80) | 5.7 (3.26) | 11.87 (3.40) |

| Exposure (years) M (SD) | 13.46 (5.70) | 6.61 (5.41) | 0 (0) |

| Usage (years) M (SD) | 19.02 (2.60) | 13.94 (3.27) | 8.00 (3.75) |

| Home Use M (SD) | 2.63 (0.76) | 1.45 (0.83) | 0.92 (0.68) |

| Social Use M (SD) | 0.84 (0.79) | 3.12 (0.78) | 1.04 (0.80) |

| Self-ratings of proficiency | |||

| Speaking M (SD) | 9.03 (1.24) | 8.86 (1.20) | 5.48 (1.62) |

| Listening M (SD) | 9.00 (1.22) | 9.10 (1.07) | 5.86 (1.20) |

| Reading M (SD) | 7.65 (2.61) | 9.02 (1.11) | 6.59 (1.69) |

| Writing M (SD) | 6.95 (3.21) | 9.05 (1.12) | 5.97 (1.99) |

| MINT score M (SD) | 63.0 (1.92) | 62.8 (2.10) | 49.8 (3.80) |

| Learning contexts | |||

| Home-only Learning N (%) | 22 (61.11%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| School-only Learning N (%) | 0 (0%) | 30 (83.33 %) | 36 (100%) |

| both N (%) | 14 (38.89%) | 6 (16.67%) | 0 (0%) |

| Medium-of-instruction | |||

| Uyghur N (%) | n/a | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Chinese N (%) | n/a | 36 (100%) | 36 (100%) |

| L1-L2 Context | L1-L3 Context | L2-L3 Context | |

|---|---|---|---|

| to Dominant language | |||

| Repeat M (SE) | 1559 (9.39) | 1558 (9.56) | 1545 (9.23) |

| Switch M (SE) | 1561 (9.43) | 1562 (9.39) | 1565 (9.28) |

| Switching cost M (SE) | 2 (9.41) | 4 (9.47) | 20 (9.25) |

| to Non-dominant language | |||

| Repeat M (SE) | 1563 (9.40) | 1579 (9.53) | 1571 (9.79) |

| Switch M (SE) | 1568 (9.36) | 1577 (9.41) | 1579 (9.46) |

| Switching cost M (SE) | 5 (9.38) | -2 (9.47) | 8 (9.62) |

| Language dominance effect M (SE) | 11 (9.40) | 36 (9.47) | 40 (9.44) |

| L1-L2 Context | L1-L3 Context | L2-L3 Context | |

|---|---|---|---|

| to Dominant language | |||

| Repeat M (SE) | 0.973 (0.0085) | 0.972 (0.008) | 0.981 (0.006) |

| Switch M (SE) | 0.959 (0.012) | 0.983 (0.005) | 0.981 (0.006) |

| Switching cost M (SE) | -0.014 (0.010) | -0.011 (0.007) | 0 (0.006) |

| to Non-dominant language | |||

| Repeat M (SE) | 0.975 (0.008) | 0.975 (0.007) | 0.963 (0.011) |

| Switch M (SE) | 0.971 (0.009) | 0.973 (0.008) | 0.969 (0.009) |

| Switching cost M (SE) | -0.004 (0.008) | -0.002 (0.008) | 0.006 (0.010) |

| Language dominance effect M (SE) | 0.014 (0.009) | -0.007 (0.007) | -0.03 (0.008) |

| outcome | d.s1 | d.s2 | a | ter | z | |||||

| predictors | b | t | b | t | b | t | b | t | b | t |

| LPC | -0.023 | -0.433,p=.667 | 0.0457 | 1.0543,p=.295 | -0.0606 | -1.02,p=.1 | 0.01102 | 1.649,p=.104 | -0.0107 | -3.41,p=.001 |

| Context(L1-L3 VS. L1-L2) | 0.958 | 1.745,p=.352 | -0.9875 | -2.05,p=.047 | 0.993 | 1.607, p=.112 | -0.08316 | -1.855,p=.068 | 0.0923 | 2.6107,p=.011 |

| Context(L2-L3 VS. L1-L2) | 0.5197 | 0.937,p=.085 | -1.374 | -2.52,p=.014 | 1.5658 | 2.194, p=.032 | -0.12167 | -2.4862,p=.015 | 0.05 | 1.4019,p=.165 |

| Context(L1-L3 VS. L2-L3) | 0.4383 | 0.79,p=.432 | 0.891 | 1.59,p=.116 | 0.891 | 1.59, p=.116 | -0.01189 | -0.235,p=.815 | 0.01766 | -1.964,p=.685 |

| N200 | 0.0365 | 1.03,p=.304 | -0.0154 | -0.5,p=.619 | -0.0199 | -0.502, p=.617 | 0.00376 | 1.409,p=.163 | -0.0789 | -0.0347,p=.972 |

| N200 × Context(L1-L3 VS. L1-L2) | 0.00941 | 0.1043,p=.917 | -0.0857 | -1.147,p=.256 | 0.0425 | 0.435, p=.665 | 0.00364 | 0.539,p=.592 | -0.00163 | -0.282,p=.778 |

| N200 × Context(L2-L3 VS. L1-L2) | -0.10026 | -1.101,p=.275 | 0.178 | 2.35,p=.021 | -0.2414 | -2.446, p=.017 | 0.01108 | 1.622,p=.109 | -0.00854 | -1.461,p=.149 |

| N200 × Context(L1-L3 VS. L2-L3) | 0.10966 | 0.9944,p=.324 | -0.263 | -2.88,p=.005 | 0.284 | 2.376, p=.02 | -0.00744 | -0.899,p=.372 | 0.0069 | 0.975,p=.333 |

| N400 | 0.0534 | 1.018,p=.312 | 0.0185 | 0.564,p=.575 | -0.0541 | -1.284, p=.203 | 0.00627 | 2.24,p=.028 | 0.00419 | 1.295,p=.2 |

| N400 × Context(L1-L3 VS. L1-L2) | -0.0389 | -0.42,p=.676 | 0.00778 | 0.101,p=.92 | -0.0647 | -0.669, p=.505 | 0.00732 | 1.1387,p=.259 | -0.00395 | -0.693,p=.491 |

| N400 × Context(L2-L3 VS. L1-L2) | -0.1157 | -1.203,p=.233 | 0.2089 | 2.609,p=.011 | -0.3246 | -3.231, p=.002 | 0.02127 | 3.1808,p=.002 | -0.01599 | -2.697,p=.009 |

| N400 × Context(L1-L3 VS. L2-L3) | 0.0769 | 0.6927,p=.491 | -0.201 | -2.18,p=.033 | 0.26 | 2.24, p=.028 | -0.0139 | -1.809,p=.075 | 0.012 | 1.761,p=.083 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).