Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Global Evidence for Parenting Programs

Parenting Programs for Adolescent Parents

Current Study

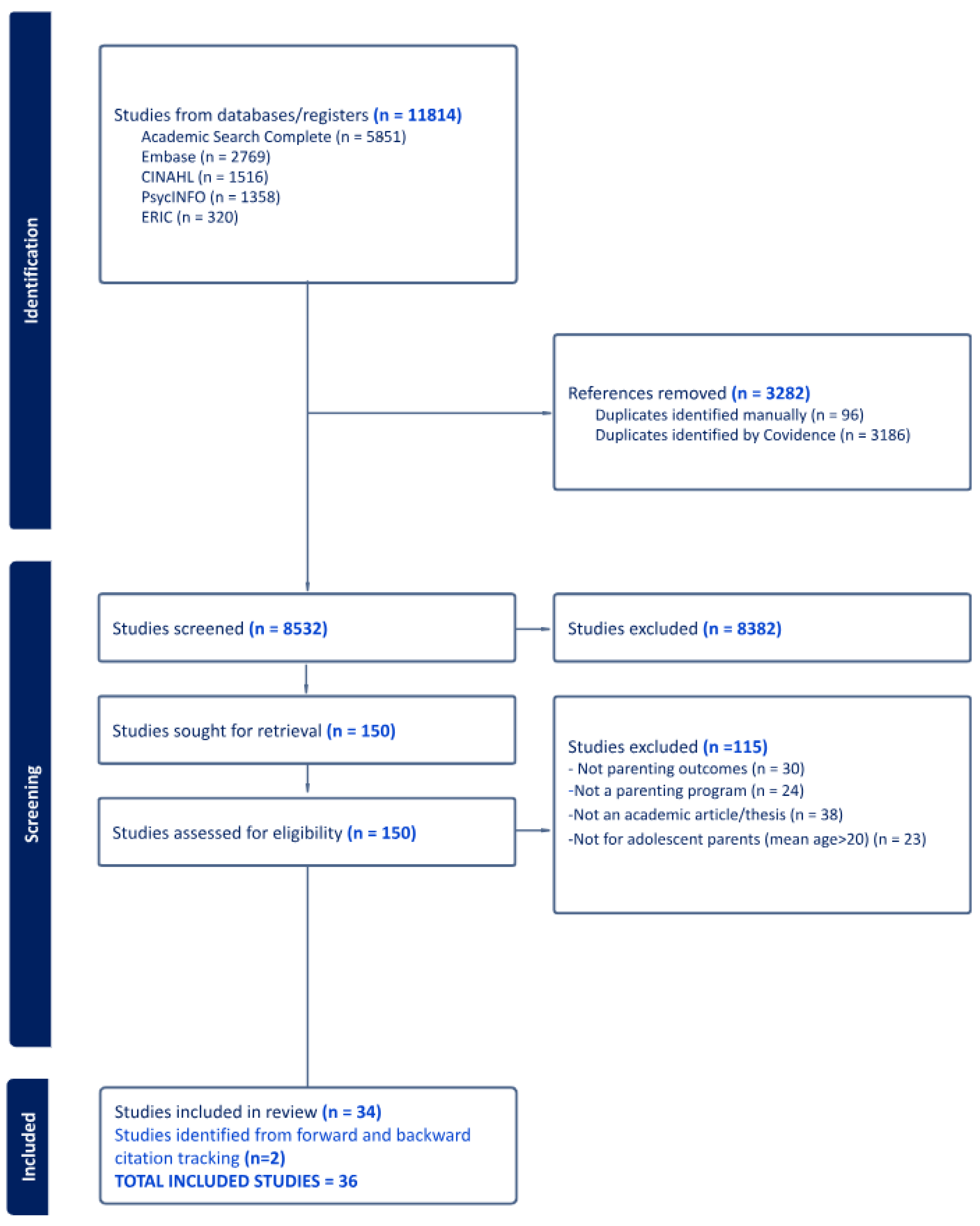

Method

Study Design

Search Strategy

Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Analysis

Coder Inter-Rater Reliability

Results

- 1.

- What Programs are Available?

- 2.

- What are the characteristics and components of these programs?

- 3.

- What are the characteristics of adolescent parents participating in these programs?

- 4.

- Study Methods and Results

Study Quality

Discussion

Summary of Findings

Promising Programs

Strengths and Limitations

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Pre-registration

Acknowledgements

Declaration of Interests

References

- Abebe AM, Fitie GW, Jember DA, Reda MM, Wake GE. Teenage Pregnancy and Its Adverse Obstetric and Perinatal Outcomes at Lemlem Karl Hospital, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2018. Biomed Res Int. 2020 Jan 19;2020:3124847. [CrossRef]

- Alarcão, F. S. P., Shephard, E., Fatori, D., Amável, R., Chiesa, A., Fracolli, L.,... & Polanczyk, G. V. (2021). Promoting mother-infant relationships and underlying neural correlates: Results from a randomized controlled trial of a home-visiting program for adolescent mothers in Brazil. Developmental science, 24(6), e13113. [CrossRef]

- Arain, M., Haque, M., Johal, L., Mathur, P., Nel, W., Rais, A.,... & Sharma, S. (2013). Maturation of the adolescent brain. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment, 449-461. [CrossRef]

- Barr, R., Morin, M., Brito, N., Richeda, B., Rodriguez, J., & Shauffer, C. (2014). Delivering Services to Incarcerated Teen Fathers: A Pilot Intervention to Increase the Quality of Father–Infant Interactions During Visitation. Psychological Services, 11(1), 10-21. [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J., Smailagic, N., Bennett, C., Huband, N., Jones, H., & Coren, E. (2011). Individual and group based parenting for improving psychosocial outcomes for teenage parents and their children. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 7(1), 1-77. [CrossRef]

- Baw, A., Mullany, B., Neault, N., Goklish, N., Billy, T., Hastings, R.,... & Walkup, J. T. (2015). Paraprofessional-delivered home-visiting intervention for American Indian teen mothers and children: 3-year outcomes from a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(2), 154-162. doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14030332.

- Barlow, J., & Coren, E. (2018). The effectiveness of parenting programs: A review of Campbell reviews. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(1), 99-102. [CrossRef]

- Barnet, B., Liu, J., DeVoe, M., Alperovitz-Bichell, K., & Duggan, A. K. (2007). Home visiting for adolescent mothers: Effects on parenting, maternal life course, and primary care linkage. The Annals of Family Medicine, 5(3), 224-232. [CrossRef]

- Barr, R., Brito, N., Zocca, J., Reina, S., Rodriguez, J., & Shauffer, C. (2011). The Baby Elmo Program: Improving teen father-child interactions within juvenile justice facilities. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(9), 1555-1562. [CrossRef]

- Berry, L., Mathews, S., Reis, R., & Crone, M. (2022). Mental health effects on adolescent parents of young children: reflections on outcomes of an adolescent parenting programme in South Africa. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 17(1), 38-54. [CrossRef]

- Bohr, Y., & BinNoon, N. (2014). Enhancing sensitivity in adolescent mothers: Does a standardised, popular parenting intervention work with teens?. Child care in practice, 20(3), 286-300. [CrossRef]

- Burkey, M. D., Hosein, M., Morton, I., Purgato, M., Adi, A., Kurzrok, M.,... & Tol, W. A. (2018). Psychosocial interventions for disruptive behaviour problems in children in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(9), 982-993. [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, F., Gilbert, R., van der Meulen, J., Kendall, S., Kennedy, E., & Harron, K. (2023). Evaluation of intensive home visiting for adolescent mothers in the family nurse partnership: a population based-data linkage cohort study in England. Available at SSRN 4337372.

- Covidence systematic review software 2024). Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org.

- Cox, J. E., Buman, M., Valenzuela, J., Joseph, N. P., Mitchell, A., & Woods, E. R. (2008). Depression, parenting attributes, and social support among adolescent mothers attending a teen tot program. Journal of pediatric and adolescent gynecology, 21(5), 275-281. [CrossRef]

- Cox, J. E., Harris, S. K., Conroy, K., Engelhart, T., Vyavaharkar, A., Federico, A., & Woods, E. R. (2019). A parenting and life skills intervention for teen mothers: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics, 143(3). 10.1542/peds.2018-2303.

- Cresswell, L., Faltyn, M., Lawrence, C., Tsai, Z., Owais, S., Savoy, C.,... & Van Lieshout, R. J. (2022). Cognitive and mental health of young mothers’ offspring: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 150(5), e2022057561. [CrossRef]

- Demeusy, E. M., Handley, E. D., Manly, J. T., Sturm, R., & Toth, S. L. (2021). Building healthy children: A preventive intervention for high-risk young families. Development and Psychopathology, 33(2), 598-613. https://.

- DeVito, J. (2010). How adolescent mothers feel about becoming a parent. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 19(2), 25. [CrossRef]

- Drummond, J. E., Letourneau, N., Neufeld, S. M., Stewart, M., & Weir, A. (2008). Effectiveness of teaching an early parenting approach within a community-based support service for adolescent mothers. Research in nursing & health, 31(1), 12-22. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, C. (2020). Supporting Adolescent Mothers Using Video Interaction Guidance (VIG) (Doctoral dissertation, Queen’s University Belfast).

- England-Mason, G., Andrews, K., Atkinson, L., & Gonzalez, A. (2023). Emotion socialization parenting interventions targeting emotional competence in young children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Psychology Review, 100, 102252. [CrossRef]

- Fatori, D., Argeu, A., Brentani, H., Chiesa, A., Fracolli, L., Matijasevich, A.,... & Polanczyk, G. (2020). Maternal parenting electronic diary in the context of a home visit intervention for adolescent mothers in an urban deprived area of São Paulo, Brazil: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 8(7), e13686. [CrossRef]

- Fatori, D., Fonseca Zuccolo, P., Shephard, E., Brentani, H., Matijasevich, A., Archanjo Ferraro, A.,... & V. Polanczyk, G. (2021). A randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of a nurse home visiting program for pregnant adolescents. Scientific reports, 11 (1), 14432. [CrossRef]

- Firk, C., Dahmen, B., Dempfle, A., Niessen, A., Baumann, C., Schwarte, R.,... & Herpertz-Dahlmann, B. (2021). A mother–child intervention program for adolescent mothers: Results from a randomized controlled trial (the TeeMo study). Development and Psychopathology, 33(3), 992-1005. [CrossRef]

- Florsheim, P., Burrow-Sánchez, J. J., Minami, T., McArthur, L., Heavin, S., & Hudak, C. (2012). Young parenthood program: Supporting positive paternal engagement through coparenting counseling. American Journal of Public Health, 102(10), 1886-1892. [CrossRef]

- Harding, J. F., Knab, J., Zief, S., Kelly, K., & McCallum, D. (2020). A systematic review of programs to promote aspects of teen parents’ self-sufficiency: Supporting educational outcomes and healthy birth spacing. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24, 84-104. [CrossRef]

- Govender, D., Naidoo, S., & Taylor, M. (2019). Prevalence and risk factors of repeat pregnancy among South African adolescent females. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 23(1), 73-87. [CrossRef]

- Harding, J. F., Knab, J., Zief, S., Kelly, K., & McCallum, D. (2020). A systematic review of programs to promote aspects of teen parents’ self-sufficiency: Supporting educational outcomes and healthy birth spacing. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24, 84-104. [CrossRef]

- Hans, S. L., Thullen, M., Henson, L. G., Lee, H., Edwards, R. C., & Bernstein, V. J. (2013). Promoting positive mother–infant relationships: A randomized trial of community doula support for young mothers. Infant mental health journal, 34(5), 446-457. [CrossRef]

- Hasani, M., Maleki, A., Mohebbi, P., & Ebrahimi, L. (2024). The effectiveness of the satir approach-based counseling on the parenting sense of competence in adolescent mothers. Preventive Care in Nursing & Midwifery Journal, 14(1), 54-63. [CrossRef]

- Henry, J. B., Julion, W. A., Bounds, D. T., & Sumo, J. N. (2020). Fatherhood matters: An integrative review of fatherhood intervention research. The Journal of School Nursing, 36(1), 19-32. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann T, Glasziou P, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, Altman D, Barbour V, Macdonald H, Johnston M, Lamb S, Dixon-Woods M, McCulloch P, Wyatt J, Chan A, Michie S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ, 348:g1687. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P.,... & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for information, 34(4), 285-291. [CrossRef]

- Hubel, G. S., Rostad, W. L., Self-Brown, S., & Moreland, A. D. (2018). Service needs of adolescent parents in child welfare: Is an evidence-based, structured, in-home behavioral parent training protocol effective? Child abuse & neglect, 79, 203-212. [CrossRef]

- In-Iw, S., Kosolruttaporn, P., & Chuwong, T. (2017). Outcomes of Caring Teenage Mothers and Their Children in Young Family Clinic, Siriraj Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai, 100(8), 872-5. PDF available.

- Jaffee, S., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Belsky, J. A. Y., & Silva, P. (2001). Why are children born to teen mothers at risk for adverse outcomes in young adulthood? Results from a 20-year longitudinal study. Development and psychopathology, 13(2), 377-397. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J., Franchett, E. E., Ramos de Oliveira, C. V., Rehmani, K., & Yousafzai, A. K. (2021). Parenting interventions to promote early child development in the first three years of life: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS medicine, 18(5), e1003602. [CrossRef]

- Jutte, D. P., Roos, N. P., Brownell, M. D., Briggs, G., MacWilliam, L., & Roos, L. L. (2010). The ripples of adolescent motherhood: social, educational, and medical outcomes for children of teen and prior teen mothers. Academic Pediatrics, 10(5), 293-301. [CrossRef]

- Kachingwe, M., Chikowe, I., Van der Haar, L., & Dzabala, N. (2021). Assessing the impact of an intervention project by the young women’s christian association of Malawi on psychosocial well-being of adolescent mothers and their children in Malawi. Frontiers in public health, 9, 585517. [CrossRef]

- Kilburn, K., Ferrone, L., Pettifor, A., Wagner, R., Gómez-Olivé, F. X., & Kahn, K. (2020). The impact of a conditional cash transfer on multidimensional deprivation of young women: evidence from South Africa’s HTPN 068. Social Indicators Research, 151, 865-895. [CrossRef]

- Knerr, W., Gardner, F., & Cluver, L. (2013). Improving positive parenting skills and reducing harsh and abusive parenting in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Prevention science, 14(4), 352-363. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. O., Jeong, C. H., Yuan, C., Boden, J. M., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Noris, M., & Cederbaum, J. A. (2020). Externalizing behavior problems in offspring of teen mothers: A meta-analysis. Journal of youth and adolescence, 49, 1146-1161. [CrossRef]

- Leijten, P., Gardner, F., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Van Aar, J., Hutchings, J., Schulz, S.,... & Overbeek, G. (2019). Meta-analyses: Key parenting program components for disruptive child behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 58(2), 180-190. [CrossRef]

- Leijten, P., Melendez-Torres, G. J., & Gardner, F. (2022). Research Review: The most effective parenting program content for disruptive child behavior–a network meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(2), 132-142. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Patton, G., Sabet, F., Subramanian, S. V., & Lu, C. (2020). Maternal healthcare coverage for first pregnancies in adolescent girls: a systematic comparison with adult mothers in household surveys across 105 countries, 2000–2019. BMJ global health, 5(10), e002373. [CrossRef]

- Long, M. (2018). Treating at-risk adolescent mothers and their children: family therapy delivered from the theraplay® model (Doctoral dissertation, Laurentian University of Sudbury). PDF available.

- MacKinnon, L. (2014). Evaluation of a parenting skills program in Russia. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 34(4), 313-330. [CrossRef]

- McCoy, A., Melendez-Torres, G. J., & Gardner, F. (2020). Parenting interventions to prevent violence against children in low-and middle-income countries in East and Southeast Asia: A systematic review and multi-level meta-analysis. Child abuse & neglect, 103, 104444. [CrossRef]

- McGirr, S., Torres, J., Heany, J., Brandon, H., Tarry, C., & Robinson, C. (2020). Lessons learned on recruiting and retaining young fathers in a parenting and repeat pregnancy prevention program. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24, 183-190. [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M. T., Kvernland, A., & Palusci, V. J. (2017). An adolescent parents’ programme to reduce child abuse. Child abuse review, 26(3), 184-195. [CrossRef]

- Kelvey, L. M., Burrow, N. A., Balamurugan, A., Whiteside-Mansell, L., & Plummer, P. (2012). Effects of home visiting on adolescent mothers’ parenting attitudes. American Journal of Public Health, 102(10), 1860-1862. [CrossRef]

- Martin, M., Kruyer R., Enwedo, J., Tatham. C., Morse K. Parenting programs for adolescent parents: A systematic review of existing interventions. PROSPERO 2024 Available from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024551584.

- Melendez-Torres, G. J., Leijten, P., & Gardner, F. (2019). What are the optimal combinations of parenting intervention components to reduce physical child abuse recurrence? Reanalysis of a systematic review using qualitative comparative analysis. Child Abuse Review, 28(3), 181-197. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S., Chipeta, M. G., Kamninga, T., Nthakomwa, L., Chifungo, C., Mzembe, T.,... & Madise, N. (2023). Interventions to prevent unintended pregnancies among adolescents: a rapid overview of systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 12(1), 198. [CrossRef]

- Nicolson, S., Judd, F., Thomson-Salo, F., & Mitchell, S. (2013). Supporting the adolescent mother–infant relationship: Preliminary trial of a brief perinatal attachment intervention. Archives of women’s mental health, 16, 511-520. [CrossRef]

- Nyemgah, C. A., Ranganathan, M., Nabukalu, D., & Stöckl, H. (2024). Prevalence and severity of physical intimate partner violence during pregnancy among adolescents in eight sub-Saharan Africa countries: A cross-sectional study. PLOS global public health, 4(7), e0002638. https:// doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0002638.

- Paine, A. L., Cannings-John, R., Channon, S., Lugg-Widger, F., Waters, C. S., & Robling, M. (2020). Assessing the impact of a family nurse-led intervention on young mothers’ references to internal states. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(4), 463-476. [CrossRef]

- Patton, G. C., Coffey, C., Sawyer, S. M., Viner, R. M., Haller, D. M., Bose, K.,... & Mathers, C. D. (2009). Global patterns of mortality in young people: a systematic analysis of population health data. The lancet, 374(9693), 881-892. [CrossRef]

- Rispoli, K. M., & Sheridan, S. M. (2017). Feasibility of a school-based parenting intervention for adolescent parents. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 10(3), 176-194. [CrossRef]

- Riva Crugnola, C., Ierardi, E., Albizzati, A., & Downing, G. (2016). Effectiveness of an attachment-based intervention program in promoting emotion regulation and attachment in adolescent mothers and their infants: A pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 195. [CrossRef]

- Riva Crugnola, C., Ierardi, E., Peruta, V., Moioli, M., & Albizzati, A. (2021). Video-feedback attachment based intervention aimed at adolescent and young mothers: effectiveness on infant-mother interaction and maternal mind-mindedness. Early Child Development and Care, 191(3), 475-489. [CrossRef]

- Robling, M., Bekkers, M. J., Bell, K., Butler, C. C., Cannings-John, R., Channon, S.,... & Torgerson, D. (2016). Effectiveness of a nurse-led intensive home-visitation programme for first-time teenage mothers (Building Blocks): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 388(10053), 1467-1476. [CrossRef]

- Rokhanawati, D., Salimo, H., Andayani, T. R., & Hakimi, M. (2023). The effect of parenting peer education interventions for young mothers on the growth and development of children under five. Children, 10(2), 338. [CrossRef]

- Rose, S. H., Chigusa, H., Sato, A., & Saito, T. (2016). Evaluation of a school-based parenting program: The effects of a preventive intervention in Japan. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(9), 2817-2826. [CrossRef]

- Save the Children (2022). Promising Directions and Missed Opportunities for Reaching First-time Mothers with Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health Services: Findings from formative assessments in two countries. PDF available.

- Schaffer, M. A., Goodhue, A., Stennes, K., & Lanigan, C. (2012). Evaluation of a public health nurse visiting program for pregnant and parenting teens. Public Health Nursing, 29(3), 218-231. [CrossRef]

- Sewpaul, R., Resnicow, K., Crutzen, R., Dukhi, N., Ellahebokus, A., & Reddy, P. (2023). A Tailored mHealth Intervention for Improving Antenatal Care Seeking and Health Behavioral Determinants During Pregnancy Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women in South Africa: Development and Protocol for a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 12(1), e43654. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, K. S., Smith, C., Cluver, L. D., Toska, E., Kelly, J., Thomas, A.,... & Sherr, L. (2025). Men matter: a cross-sectional exploration of the forgotten fathers of children born to adolescent mothers in South Africa. BMJ open, 15(7), e092723. [CrossRef]

- Stiles, A. S. (2010). Case study of an intervention to enhance maternal sensitivity in adolescent mothers. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 39(6), 723-733. [CrossRef]

- Toska, E., Saal, W., Chen Charles, J., Wittesaele, C., Langwenya, N., Jochim, J.,... & Cluver, L. (2022). Achieving the health and well-being Sustainable Development Goals among adolescent mothers and their children in South Africa: Cross-sectional analyses of a community-based mixed HIV-status cohort. PloS one, 17(12), e0278163. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M. R., Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Day, J. J. (2014). The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a multi-level system of parenting support. Clinical psychology review, 34(4), 337-357. [CrossRef]

- Suess, G. J., Bohlen, U., Carlson, E. A., Spangler, G., & Frumentia Maier, M. (2016). Effectiveness of attachment based STEEP™ intervention in a German high-risk sample. Attachment & human development, 18(5), 443-460. [CrossRef]

- Tua, A. I. (2018). Social Inclusion Outcomes for an Organization’s Adolescent Parent Intervention. PDF available.

- UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund) (2022). Motherhood in childhood—The untold story: UNFPA policy brief, 27 June 2022. PDF available.

- Valades, J., Murray, L., Bozicevic, L., De Pascalis, L., Barindelli, F., Meglioli, A., & Cooper, P. (2021). The impact of a mother–infant intervention on parenting and infant response to challenge: A pilot randomized controlled trial with adolescent mothers in El Salvador. Infant Mental Health Journal, 42(3), 400-412. [CrossRef]

- Wahlen, K., & Katja, H. (2018). Preventive parenting interventions: The role of involvement and consequences for adolescent mothers’ parenting outcomes. Journal of youth and adolescence, 47(2), 377-388. [CrossRef]

- Wageman, C. M., & Buch, H. D. (2014). Maternal attitudes and health outcomes in adolescent mothers participating in a community program. Journal of clinical psychology in medical settings, 21(1), 98-106. [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. H., Dumas, B. P., & Edlund, B. J. (2013). An evidence-based parenting intervention with inner-city teen mothers. Journal of National Black Nurses’ Association: JNBNA, 24(1), 24-30. PMID: 24218870. (No doi available).

- World Health Organization. (2012). Strengthening the role of the health system in addressing violence, in particular against women and girls, and against children: Report by the Secretariat (WHA65.13). World Health Organization. PDF available.

- World Health Organization. (2016). INSPIRE: Seven strategies for ending violence against children. World Health Organization. PDF available.

- World Health Organization. (2023). WHO guidelines on parenting interventions to prevent maltreatment and enhance parent–child relationships with children aged 0–17 years. World Health Organization. PDF available.

- World Health Organization. (2024). Adolescent pregnancy. World Health Organization. PDF available.

- Williams, A. L., & Lytle, L. M. (2017). Parenting interventions for adolescent mothers: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(4), 431-438. [CrossRef]

- Woller, D. R., Ho, K. Y., & Schultz, L. R. (2017). Understanding parenting interventions with adolescent mothers: A systematic review. Psychological Services, 14(4), 490-501. [CrossRef]

- Wyatt Kaminski, J., Valle, L. A., Filene, J. H., & Boyle, C. L. (2008). A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 36, 567-589. PDF available.

- Zegers, J. A., & Gragnolati, M. (2017). A systematic review of programs that promote the maternal-infant relationship in adolescent mothers. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(5), 541-547. [CrossRef]

| Citation | Program Name | Design | Program Rationale | Parenting Topics | Program Timing | Mode | Target & Prevention Level1 | Setting | Number Sessions | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alarcão (2021); Fatori (2020) & Fatori (2021) |

Primeiros Lacos |

Designed for teen parents | Promotes parent-child attachments and interactions and parent self-efficacy based on attachment theory, self-efficacy theory and bioecological development theory | Mother-infant attachment relationships | During and after pregnancy (until 1 year of age) | In-person | Individual / Selective - living in poverty | Homes - Urban | 60-62 | Weekly for the first 16 weeks of pregnancy and then biweekly during pregnancy; weekly during the last month of pregnancy; monthly from 21-24 months | |

| Barlow (2013) | Family Spirit | Designed for teen parents | Promotes parent child attachments and advance social learning based on attachment theory and social-learning theory | Positive parenting strategies; parent mental health; parent knowledge and self-efficacy | During and after pregnancy | In-person | Individual / Selective- American Indian | Homes - Rural | 43 | Weekly | |

| Barr (2011) & Barr (2014) |

Baby Elmo Program | Designed for teen parents | Promotes attachment, infant exploration, and following the child’s lead among teen fathers based on Sesame Beginnings | Positive parenting strategies; parent-child attachment and interactions | After pregnancy | In-person | Individual / Selective -Incarcerated fathers | Juvenile detention facility | 10 | Weekly or bi-weekly | |

| Berry (2022) | None | Designed for teen parents | Supports parent-child interactions and attachments as well as reduce parental depression based on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model of development | Parent attachment | After pregnancy | In-person | Group/ Universal |

Schools - Urban | 20 | Weekly | |

| Bohr (2014) | Right from the Start | Designed for teen parents | Enhances maternal sensitivity and infant attachment security by teaching specific parental skills based on the Coping Modeling Problem Solving Approach | Positive parenting strategies’ parent-attachment and bonding; positive parent-child relationships and interactions; maternal sensitivity | After pregnancy | In-person | Group/ Universal |

Community settings | 8 | Weekly | |

| Cavallaro (2023), Paine (2020) & Robling (2016) |

Family Nurse Partnership | Adapted for teen parents | Promotes reduction in child maltreatment and health and development outcomes for children through mother support through home visits from trained family nurses. | Positive parenting; parent-attachment or bonding; positive parent-child relationships and interactions; child maltreatment; child development; adolescent mother development skills; social support and social services | Early pregnancy until child’s second birthday | In-person | Individual / Universal | Home – Urban & Rural | Up to 64 |

Weekly or Bi-weekly | |

| Cox (2019) | Office of Adolescent Pregnancy Programs | Designed for teen parents | Improves teen parenting while enhancing youth and family development including positive, empathetic relationships as well as self-efficacy and self- based on Ansell-Casey Life Skills Assessment Curriculum, the Women’s Negotiation Project Curriculum for Teen Mothers, and the Nurturing Curriculum |

Positive parenting; adolescent development skills | After pregnancy | In-person | Individual / Universal | Pediatric hospital - Urban | 12 | Not reported | |

| Demeusy (2021) | Building Healthy Children | Designed for teen parents | Improves maternal sensitivity and fosters secure parent-child attachment, reducing maternal depression, and mitigating risk factors for child maltreatment and poor development outcomes, based on Child-Parent Psychotherapy (attachment theory) and interpersonal psychotherapy for adolescents. | Positive parenting; maternal mental health; child maltreatment (prevention) | After pregnancy for 3 years | In-person | Individual / Selective - low income | Homes - Urban | Unspecified number | Weekly | |

| Elliot (2020) | Video Interaction Guide | Adapted for teen parents | Enhances attuned interactions and maternal sensitivity in adolescent mothers, based on SATIR family therapy approach. | Positive parenting strategies; parent-child attachment or bonding | After pregnancy | Hybrid: in-person initially then online | Individual / Universal | Home or community, based on ppt choice | 3 cycles of recording, review and discussion | Bi-weekly | |

| Firk (2021) | Steps Toward Effective Enjoyable Parenting-Brief (STEEP-B) | Adapted for teen parents | Promotes secure parent-child attachment by enhancing sensitive parental care, parenting behaviours, and social support, based on attachment-based early intervention programs. | Positive parenting strategies | After pregnancy for 9 months | In-person | Individual / Universal | Homes | 12-18 | Monthly or bi-monthly | |

| Florsheim (2012) | Young Parenthood Program (YPP) | Designed for teen parents | Develops skills to maintain positive, supportive coparenting relationships and to create stable, nurturing environments, based on family systems theory. | Positive parenting; coparenting relationships | During pregnancy | In-person | Individual/ Universal |

Hospitals, homes, and community organizations - Urban | 10 | Weekly | |

| Hans (2013) | Chicago Doula Project | Designed for teen parents | Supports young mothers during childbirth and transition to parenting with empathetic care and understanding of the newborn. | Positive parenting strategies | During and after pregnancy to three months postpartum | In-person and via telephone | Individual / Universal | Homes and hospitals - Urban | 20-25 | Weekly | |

| Hasani (2024) | SATIR | Adapted for teen parents | Promotes parent-child attachment based on strengths-based approach. | Parent-child attachment or bonding | After pregnancy | Hybrid: first session in-person then WhatsApp | Individual/ Universal | Hospital for in-person then online | 6 | Weekly | |

| Hubel (2018) | SafeCare | Adapted for teen parents | Program for at-risk parents that aims to reduce child maltreatment recidivism by improving parent-child relationships and parent knowledge and skills. | Positive parenting strategies; positive parent-child relationships; child development; home safety; child healthcare | After pregnancy for 6 months | In-person | Individual/ Treatment - under contract with the child welfare system |

Homes – Rural and urban | 26 | Weekly | |

| In-iw (2017) | Young Family Clinic (YFC) | For teen parents | Clinic that provides a one-stop shop for teen mothers and their children with the objectives of preventing subsequent pregnancy, promoting child-rearing, and preventing child maltreatment. | Adolescent development; child development; child maltreatment | After pregnancy for 2 years | In-person | Individual/ Universal |

Hospitals | Appointments ongoing | ?? | |

| Kachingwe 2021 | Community Model for Fostering Health and Well-Being Amongst Adolescent Mothers and their Children | For teen parents | Empowers adolescent girls to prioritize the health and well-being of them and their children based on consultations with local stakeholders and a baseline needs assessment. | Positive parenting; child development; adolescent development skills | After pregnancy | In-person | Group/ Universal | Community - Rural | 36 | Two years | |

| Long (2018) | Theraplay | Adapted for teens | Promotes positive mother-child interactions in at-risk population based on Theraplay play-based, family-focused treatment grounded in attachment theory. | Parent-child attachment and bonding. | After pregnancy | In-person | Individual/ Indicated - parents have a concern in the child’s social, emotional or behavioral wellbeing | Community - Urban | 15 | Weekly | |

| Mackinnon (2014) | Pskov Positive Parenting | For teen parents | Strengthens parenting skills with the goal to prevent child abuse and neglect and to reduce the number of children abandoned to state-run orphanages. |

Positive parenting strategies | After pregnancy | In-person | Group/ Selective - dropped out of school and unemployed | Community Organization - Urban | 10 | Weekly | |

| McHugh (2017) | Bellevue Hospital Adolescent Parenting Program | For teen parents | Reduce child abuse reports and promote well-baby visits, immunizations and referrals for developmental delays in high-risk population. | Positive parenting strategies; child development; SRH and maternal education | First 12 months after birth | In-person | Individual/ Universal | Hospital - Urban | ? | Weekly | |

| McKelvey (2012) | Thrive Program | Adapted for teens | Reduces child maltreatment and improves parenting attitudes and beliefs based on Healthy Family Africa (HFA).. | Positive parenting; child development; parent health and wellbeing | From pregnancy until child’s third birthday | In-person | Individual/ Universal | Homes | ? | ? | |

| Nicolson (2013) | Adolescent Mothers’ Program: Let’s Meet Your Baby as a Person (AMPLE) | For teen parents | Aims to influence mothers’ interaction with their baby by helping them see their baby as a person from the beginning, based on attachment theory. | Parent-child attachment or bonding; positive parent-child relationships and interactions; child development | One session in late pregnancy and one after birth | In-person | First session – group; Second session - individual - Universal | Hospital | 2 | Before & after birth | |

| Rispoli (2017) | Parents Interacting with Infants – Teen Version (PIWI-T) | Adapted for teens | Teaches infant attachment, brain development, available community resources. | Parent-child attachment or bonding; positive parent-child relationships and interactions; child development; social support and social services | After pregnancy | In-person | Groups / Universal | School (daycare classroom) - Urban | 4 | Weekly | |

| Riva Crugnola (2016) & Riva Crugnola (2021) |

Promoting Responsiveness, Emotion Regulation and Attachment in Young Mothers and Infants (PRERAYMI) |

Designed for teen parents | Improves the mother-infant relationship, increase maternal responsiveness and reflectivity, and promote secure attachment between mothers and infants, based on attachment theory | Parent-child attachment or bonding; adolescent development skills; emotional regulation | After pregnancy for 6 months | In-person | Individual/ Universal | Hospital | 10- 15 | Bi-weekly | |

| Rokhanawati (2023) | Promoting First Relationship | For teen parents | Enhances maternal sensitivity through a Peer Education Program based on Social Learning Theory, Theory of Reasoned Action and Diffusion of Innovation Theory. | Positive parenting; parent-child attachment and bonding; positive parent-child relationships and interactions | After pregnancy | In-person | Individual/ Universal | Homes - Rural | 8 | Biweekly | |

| Schaffer (2012) | Home Visit Nurse Agency (MVNA) Pregnant and Parenting Teens Program | For teen parents | Promotes family and child health and family self-sufficiency through mentoring. | Positive parenting strategies; parent mental health; adolescent development skills | From pregnancy until two years old | In-person | Individual/ Universal | Home or other safe community setting- Urban | 16 |

Monthly | |

| Stiles (2010) | Promoting First Relationships Intervention | For teen parents | Promotes maternal sensitivity towards child, based on Barnard’s model of maternal/infant relationships. | Positive parenting strategies; parent-child attachment or bonding; positive parent-child relationships and interactions | After pregnancy | In-person | Individual / Universal |

Home - Rural | 8 |

Bi-weekly | |

| Suess (2016) | Steps Towards Effective and Enjoyable Parenting (STEEP) | Adapted for teen parents | Promotes secure attachment and maternal sensitivity, based on attachment theory and video feedback. | Parent-child attachment or bonding; adolescent development skills (social support) | Child aged 12-24 months | In-person | Individual & Group/ Indicated - within the Child Welfare System | Home & Community | 30 home visits; 12 video interventions; 4 family/ friends nights; 2 outings | Weekly | |

| Tua (2018) | Family Incubator Model | For teen parents | Promotes social inclusion based on complex systems theory. | Positive parenting strategies; adolescent development skills | Unspecified | In-person | Individual & Group/ Selective - without a high school diploma | Home & Community -Urban | Unspecified | Unspecified | |

| Valades (2021) | Thula Sana | Adapted for teen parents | Promotes maternal sensitivity and infant secure attachment based on socio-ecological model and attachment theory. | Positive parenting strategies; parent-child attachment or bonding | Late pregnancy to 6 months old | In-person | Individual/Universal | Home - Rural | 16 | Weekly until 2 months, bi-weekly until 4 months, monthly until 6 months | |

| Williams (2013) | Incredible Years Program (IYP) | Adapted for teen parents | Improves effective parenting skills through interactive play, parenting skills, problem solving-skills and non-violent discipline, | Child maltreatment prevention; positive parenting strategies; parent-child attachment or bonding; child development | After pregnancy | In-person | In-Person Group/ Universal | School - Urban | 8 | Weekly | |

| Citation | Country | Parent age, average (range) | Gender | Ethnicity | Child age range | Study Inclusion/Exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alarcão (2021) Fatori (2020) & Fatori (2021) |

Brazil | 17.11 (14 - 19 ) | Female | 31.3% White (only explicitly reported ethnicity breakdown) | 6-24 months | Adolescent mothers aged 14–19 years, First pregnancy, 8–16 weeks gestation, Low socioeconomic status (classified as classes C/D/E according to the Brazilian classification system, ABEP, 2007), Living in impoverished urban areas of São Paulo, Brazil. |

| Barlow (2013) | USA | 18.12 (12–19 ) | Female | American Indian (self-identified) | birth - 12 months | Pregnant and ≤32 weeks' gestation, 12–19 years of age at conception, American Indian (self-identified), and residing in one of four participating reservation communities. |

| Barr (2011) | USA | 17.1 (15 - 18 ) | Male | Fifteen of the 20 teen participants were Hispanic; four were African-American and one was of mixed racial descent. | 6-36 months | Teen fathers aged 15 to 18 years incarcerated in juvenile detention facilities. Fathers had to have children between the ages of 6 to 36 months.Participation was voluntary, and fathers needed to complete at least 4 out of 10 sessions of the Baby Elmo Program to be included in the final analysis. |

| Barr (2014) | USA | 16.89 ()i | Male | 66.19% Hispanic, 22.22% Black, 9.52% Mixed, and 1.59% White. | birth to 15 months | Incarcerated teen fathers with an infant under 15 months of age at enrolment. No direct involvement with child protection services for the target infant or any other infant. Consent from the caregiver to bring the infant into the facility to participate in the study. |

| Berry (2022) | South Africa | 16.38 (12-22) | Female | Peri-urban settlements near Cape Town metropole (Gugulethu, Khayelitsha, and Nyanga), which are predominantly populated by Black African communities. | 0-24 months | Adolescents aged 12-22 years. Participants had to have parental responsibility for at least one child and had substantial time spent on parenting duties. This included both biological and non-biological parents (e.g., siblings or relatives caring for children). Participants were recruited from three secondary schools in Cape Town. Self-selection: Adolescents self-selected into the parenting program. Exclusion: Grade 12 learners (final year of secondary school) were excluded from the study. |

| Bohr (2014) | Canada | 18.54 (17-22 ) | Female | Mixed (63% Canadian-born, others from Philippines, Jamaica, England, Peru) | 1-7 months | Adolescent mothers recruited through a young parent residential resource center |

| Cavallaro (2023) | UK | (13-19) | Female | Birth - 24 months | Retrospective cohort of all first-time mothers aged 13-19 years at last menstrual period with live births in England between 1 April 2010 and 31 March 2019 and their first-born child(ren). 136 Local Authorities in England had an active FNP site between 2010 and 2019 | |

| Cox (2019) | USA | 17.3 () | Female | African American: 33.3% Hispanic: 60.1% Other: 6.5% |

1 - 15 months | Maternal age 19 years at delivery and willingness to receive maternal and infant care in a teen-tot program.Exclusion: Teens with infants 12 months or older were excluded. |

| Demeusy (2021) | USA | 19.08 (15-23 ) | Female | 66.4% African-American 22.8% Caucasian 4.7% biracial 6.0% other race 17.8% Latina |

birth - 36 months | Mothers under 21 years of age at the birth of their first child. Eligible for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Maximum of two children under the age of 3 years. Resident of Monroe County. No previous Child Protective Services indication with her child. Exclusion: Severe maternal medical illness, severe maternal psychiatric conditions, IQ less than 70, and/or current incarceration. |

| Elliott (2020) | UK | (17-18) | Female | 5-18 months | First-time mother aged 16-19 years with child aged 0-5 years; adolescent is primary caregiver, English-speaking, has no mental health difficulties, child has no chronic illness, not on Child Protection Register. Exclusion: Under age 16, not first-time mother, known mental health difficulties, on Child Protection Register, child over age 5, not primary caregiver, non-English speaking, child has chronic illness | |

| Firk (2021) | Germany | 18.3 (14 -21) | Female | The majority of the mothers in the study were German (100% in the standard care group and 96.6% in the STEEP-b group) | 3-21 months | 21 years old or younger at the beginning of pregnancy, mother and child live together, sufficient verbal and intellectual capacity, child between 3 and 6 months old. Exclusion: Maternal criteria: Current substance abuse, current suicidal ideation, psychotic disorders, separation from the child (> 3 months). Child criteria: Preterm birth (< 36 weeks gestation), serious medical problems, and genetic syndromes. |

| Florsheim (2012) | USA | 16.5 (Mothers: 14-18 years; Fathers: 14-24 years) | Female and Male | The majority of the participants were either Latino or White. Specifically, 50% of the mothers were Latino, and 45% of the fathers were Latino, while the remainder identified as White or other ethnicities | Mothers had to be primiparous, at least 14 years old but not older than 18 years, less than 26 weeks pregnant, and have a coparenting partner (the biological father) who was also willing to participate in the study. The eligibility criterion for biological fathers was that he had to be at least 14 years old but not older than 24 years at the initial assessment. | |

| Hans (2013) | USA | 18.2 () | Female | African American | Pregnant women under the age of 22 and less than 34 weeks gestationExclusion: Plans to move from the area, plans to give up baby for adoption | |

| Hasani (2024) | Iran | (13-20) | Female and Male | Newborns | > 20years, low-risk pregnancy, spending at least 24h after childbirth, stabilization of the mother’s vital signs, access to a cell phone with WhatsApp, living with a sexual partner, and obtaining a score of less than 14.5 based on the GHQ-12, full-term infants without recognized abnormalities at birth. Exclusion: Unwillingness to continue cooperation, hospitalization of the infant in the NICU, and postpartum complications in the mother. | |

| Hubel (2018) | USA | 19.6 (< 21) | 98 % Female | 63% White, 12.9-18.6% American Indian, 10.6-11.4% African American, 6.1-6.2% Hispanic, 3.1-4.5% Other | Adolescent parents (21 years or younger) referred to community-based agencies under contract with the child welfare systemExclusion: Sexual abusers | |

| In-iw (2017) | Thailand | 17.2 () | Female | Teenage mothers and their children who attended the Young Family Clinic (YFC) at Siriraj Hospital and were followed up regularly for at least two yearsExclusion: Mothers and infants who did not complete the two-year program. | ||

| Kachingwe (2021) | Malawi | 17.56 (13-22) | Female | 1-37 months | Adolescent mothers 18 years of age and below | |

| Long (2018) | Canada | () | Female | Parents must have self-referred, aged 19 years of age or younger with child 5 years or younger, parents recognized a concern in their child’s psycho-social-emotional health and well-being or noted behavioral concerns in their child and/or parents had historical or present involvement with the Children’s Aid Society of the Districts of Sudbury and Manitoulin, Parents and/or their child were not experiencing abuse/violence and were not in an active crisis resulting from past experiences of trauma. | ||

| Mackinnon (2014) | Russia | (16-22) | Female | |||

| McHugh (2017) | USA | 17 (14–18 ) | Female | 89.7% Hispanic, 6.9% Bengali, 3.4% African American | birth - 12 months | Age of mother (less than 18 years), willingness to participate in the program |

| McKelvey (2012) | USA | 17.4 () | Female | 40.5% European American (White) 51.1% Black 7.0% Hispanic 1.3% Other |

Adolescent mothers | |

| Nicolson (2013) | Australia | 18.8 (15.7-20.9) | Female | Seventy-two participants (74.2 %) were born in Australia or New Zealand, of whom two were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (ATSI) (2.1 %) The remaining 25 were born in 16 different countries. Fourteen (14.4 %) were born in African countries and seven (7.2 %) in countries of the Asia Pacific region. | 4 months | Adolescents with viable pregnancies and deemed mature minors, competent to give informed consent and able to complete a questionnaire in English, recruited through the YWP clinic. |

| Paine (2020) | UK | 17.91 (13.82-19.98) | Female | When compared to the original Building Blocks trial, the BABBLE sample was significantly different in terms of maternal ethnicity (with fewer participants of black backgrounds), education (fewer with no qualifications), and more spoke only English in the home (all p < .05, available under request). |

22–33 months | Under the age of 19 and living within a catchment area of an FNP team. |

| Riva Crugnola (2016) | Italy | 18.75 (15-21 ) | Female | In the intervention group 26 mothers were Italian, 2 European and 4 Latin American and in the control group 14 were Italian and 2 Latin Americans. | 3 months | Adolescent mothers aged 14–21, having a first child, and being able to speak and understand the Italian language |

| Riva Crugnola (2021) | Italy | 17.33 (14-21) | Female | Majority Italian. The remaining were European or Latin American who knew the Italian language and were integrated into the Italian cultural context. | 3-9 months | Ability to speak and understand the Italian language; age range between 14 and 21; absence of maternal psychopathology, uneventful delivery, infants born at full term with no medical complications and physically healthy. Exclusion: Prematurity and twin birth. |

| Rispoli (2017) | USA | (15-19) | Female and Male | Of the 3 case study participants: 2 White, 1 Multiracial - the children were describe by the mothers as native american, multiracial and biracial. | 0-36 months | Adolescent parents whose children were enrolled in daycare classrooms in select high schools that provided programming for pregnant and parenting students and who had a history of problematic academic performance. |

| Robling (2016) | UK | 17.9 (< 19 ) | Female | White: 88%, Mixed: 5-6%, Asian: 1-2%, Black: 4-5%, Other: <1% | birth - 24 months | First-time mother, aged 19 or younger, living within the catchment area of a local FNP team, ess than 25 weeks pregnant at the time of recruitment, Able to provide consent, Able to speak English, Women expecting multiple births and those with a previous pregnancy ending in miscarriage, stillbirth.. Exclusion: Women who planned to have their child adopted or intended to move outside the FNP catchment area for more than three months. |

| Rokhanawati (2023) | Indonesia | () | Female | Young mothers from Gunung Kidul District, Yogyakarta | Young mothers aged <20 years, whose first child is aged 12–42 months and who have a minimum education level of Elementary School | |

| Schaffer (2012) | USA | 16.7 (13-19) | Female | Ethnicity included 45% African American and 27% Hispanic teens. Additional ethnic groups represented among teens in the program were American Indian (8%), Asian (7%), White (6%), African (3%), and other (3%) | Adolescent mothers need to be under age 20 and enroll before their child is 2 months of age. They may also enroll in the program if they have more than one child and are under 20 years of age. | |

| Stiles (2010) | USA | 17 (< 18) | Female | Hispanic mother with a black father | 3-6 months | First-time teen mother younger than age 18 years at recruitment who had delivered a healthy infant (≥ 37 weeks gestation, no birth anomalies, and no chronic illness) and who was the primary caregiver for her infant. Exclusion: Non-English-speaking mother, preterm birth (<37 weeks), newborn with birth anomalies, multiple births, infant with chronic illness, or a mother who lived outside of a 75-mile radius from the researcher. |

| Suess (2016) | Germany | 18.08 () | Female | 12-24 months | Participants were drawn from child welfare agencies serving mothers at risk for neglect and abuse. All mothers were eligible for child welfare support. |

|

| Tua (2018) | Puerto Rico | () | Female | The group of adolescent parents included in this study are Latinos/Hispanics, usually from Puerto Rico. | Adolescents who became pregnant with their first child before they were 19 years and 11 months of age, living in Bayamon and vicinities, lack a high school diploma but have achieved the 8th grade. | |

| Valades (2021) | El Salvador | 17 (14-19) | Female | Predominantly rural, low-resource communities in El Salvador | Primiparous women in their third trimester of pregnancy; between 14 and 19 years of age; without medical complications during pregnancy; residing in one of the four participating municipalities. | |

| Williams (2013) | USA | 16.7 (15-18) | Female | 60% African American 40% Hispanic/Latino |

1-16 months | Adolescent mothers, grades 9-12, enrolled in the school-based Early Head Start program, English-speaking. |

| Citation | Methodology | Method - details | Relevant Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alarcão (2021) | RCT | RCT - with random blind assigned to intervention or care as usual (CAU) | Mother-infant attachment relationship at child age 12 months | At 12 months, infants in the Primierios Laços intervention group had higher EAS Child Involvement scores than those in the CAU group. A greater proportion of infants in the intervention group were classified as "Emotionally Available" compared to the CAU group. |

| Barlow (2013) | RCT | RCT - Participants randomly assigned to intervention or care as usual. | Parenting knowledge, self-efficacy, home safety, maternal psychosocial and behavioural risk, child emotional and behavioural functioning at 12 months. | Family Spirit Program mothers demonstrated increased parenting knowledge, self-efficacy, better home safety attitudes, and reduced externalizing behaviors, while their children had fewer externalizing problems. The impact was stronger for mothers with a history of substance use, with their children showing fewer externalizing and dysregulation problems and a lower likelihood of being clinically "at risk" for externalizing and internalizing issues. However, the intervention did not significantly affect HOME scale scores or maternal substance use. |

| Barr (2011) | Mixed | Mixed methods - quasi-experimental pilot with control and intervention group and one case study. | Joint attention, emotional engagement, child involvement, turn-taking and following the lead | Individual growth curve analyses showed significant gains in five of six measures of emotional responsiveness over time for Bably Elmo Program participants. These results indicate improvements in positive high quality interactions and communication during sessions between infants and their incarcerated parents. |

| Barr (2014) | Quantitative | Quants - Observational study and pre-post design | Father-baby activities and parenting skills | The Baby Elmo Program fathers showed significant improvements in parenting behaviors (e.g., praise, maintains and extends) and child engagement over time, with increases in parent support and infant engagement linked to more intervention sessions, while correlations highlighted strong associations between key parenting skills and outcomes. |

| Berry (2022) | Quantitative | Quants - quasi-experimental, longitudinal design with baseline-midline-endline. | Depression and parenting behaviours at 10-month follow-up. | Positive parenting and resilience improved for all participants suggesting that changes over time were not caused by the programme. Intervention participants with higher depression showed less change towards positive parenting indicating the importance of addressing adolescent parent depression. |

| Bohr (2014) | Quantitative | Quants - pre-post design pilot, no control group | Maternal sensitivity, parenting confidence, parenting stress, postnatal depression. | Maternal sensitivity significantly improved for Right from the Start participants but there was no significant difference for depression or parenting stress. |

| Cavallaro (2023) | Quantitative | Quants - secondary data analysis with linked cohort receiving intervention or CAU. | Child maltreatment and child health outcomes for up to 7 years after birth. | No evidence of FNP and indicators of child maltreatment; weak evidence for likelihood children achieving a good level of development by age 5. |

| Cox (2019) | RCT | RCT - random assignment | Maternal self-esteem, parenting attitudes, preparedness for mothering, acceptance of infant, expected relationship with infant at 36 months. | Significantly improved maternal self esteem, preparedness, acceptance and expected relationship in the Office of Adolescent Pregnancy Programs intervention group. |

| Demeusy (2021) | Quantitative | Quants - longitudinal, quasi-experimental with random assignment to intervention or care-as-usual. | Positive parenting, maternal mental health, prevention of child maltreatment and harsh parenting, child symptomatology and self-regulation. | BHC participants showed significant reductions in depressive symptoms at mid-intervention, which was associated with improvements in parenting self-efficacy and stress as well as decreased child internalizing and externalizing symptoms at postintervention. Intervention mothers exhibited less harsh and inconsistent parenting, and marginally less psychological aggression. Intervention children also exhibited less externalizing behavior and self-regulatory difficulties across parent and teacher report. |

| Elliott (2020) | Mixed | Mixed - Semi-structured interviews and quantitative observations with no control group. | Attuned interactions - being attentive, encouraging initiatives, receiving initiatives, developing attuned interactions, guiding and deepening discussion; maternal sensitivity. | There was no significant effect for the VIG participants. |

| Fatori (2020) | RCT | RCT - with random blind assignment to intervention or CAU. | Maternal parenting (singing a song, telling a story, going for a stroll, playing, talking, eating together, positive physical contact)) and parental well-being at 18 months. | Significant effect of Primeiros Laços on parental well-being and maternal parenting behaviour - singing and telling a story, but not on other behaviours. |

| Fatori (2021) | RCT | RCT - with random blind assignment to intervention or CAU, longitudinal design with assessment at 3, 6, 12, & 24 months. | Child development, home environment (emotional and verbal responsivity, avoidance of restriction and punishment, organisation of the physical environment, provision of play materials, parental involvement and variety in daily stimulation. | Significant effect of Primeiros Laços on child expressive language development, maternal emotional / verbal responsivity, variety in daily stimulation but not on other areas of development or home environment. |

| Firk (2021) | RCT | RCT with blind assessors assessing at baseline, midline and endline. | Maternal sensitivity and child responsiveness during free play and an age-appropriate stress situation. | No effect of STEEP-b program on maternal sensitivity, structuring, non-intrusiveness or non-hostility and child responsiveness or involvement. |

| Florsheim (2012) | Quantitative | Quants - quasi-experimental with random assignment to intervention or CAU. | Co-parenting skills and parental functioning second trimester, 3 months & 18 months. Paternal engagement at T3. | Fathers completing the Young Parenthood Program demonstrated more positive parenting. Positive outcomes in paternal functioning were mediated through mother's interpersonal skill development. This in turn predicted positive parenting and coparenting including higher rates of paternal nurturance and lower child abuse potential scores. |

| Hans (2013) | RCT | RCT - | Parent-infant interactions at 4, 12, & 24 months and parenting attitudes and stress. | Mothers in the Chicago Doula Project had more child-centred parenting values, more positive engagement with infants and were more likely to respond to infant distress at 4 months. Infants were less upset during interactions. Beyond the intervention which ceased at 3 months, effects were not sustained. |

| Hasani (2024) | Quantitative | Quants - quasi-experimental with pre-post-6wks post design, no control group. | Parent-child attachment - absence of hostility and pleasure in interaction. | Parenting attachment improved for quality of attachment, absence of hostility and pleasure in interaction for SATIR participants. |

| Hubel (2018) | Quantitative | Quants- quasi-experimental with intervention and CAU. | Child welfare recidivisim, depression and child abuse potential. | The SafeCare intervention did not result in significantly improved outcomes in terms of preventing recidivism or reduction in risk factors associated with child abuse and neglect as compared to child welfare services as usual. Further, no significant differences in program engagement and satisfaction between SafeCare and services as usual were detected. |

| In-iw (2017) | Descriptive | Quants- descriptive, observational. | Child maltreatment and parenting skills. | The YFC showed good outcomes for teenage mothers and their children. Educational sessions, particularly types of contraceptives, parenting skills, and risk prevention had an impact on young family’s outcomes. |

| Kachingwe (2021) | Mixed | Mixed - quasi-experimental with intervention and control groups with pre/post assessment design, participant interviews. | Parenting skills, nutritional practice, parenting stress, mother-child interaction, child physical development and cognitive functions. | The Young Womens' Christian Association of Malawi intervention group showed statistically significant increase in knowledge on parenting skills, nutritional practice, motor skills and cognitive functions in children, as well as expressive language and socio-emotional capacities in children, while the change in confidence and psychosocial well-being was not statistically significant. |

| Long (2018) | Mixed | Mixed - case study and pre-post pilot with no control group. | Parenting stress and parenting interactions | There were observable differences in the interactions of mothers particularly if they attended 10-15 sessions of Theraplay. Increased parenting stress co-occurred with increased negative parenting behaviours. |

| Mackinnon (2014) | Qualitative | Quals - photovoice and interviews. | Maternal sensitivity & social connection. | Participants in the Pskov Positive Parenting Program shifted behaviours to include more sensitive, responsive parenting behavior; competence and confidence in the mothering role increased; social connections between the participants strengthened and helped reduce their isolation; the Program provided information about maternal rights and facilitated access to social and medical services; the Program provided a forum and resources for participants experiencing domestic violence; and finally, the Program had a non-hierarchical, participatory structure. |

| McHugh (2017) | Quantitative | Quants - observational study for intervention completers verses non-completers. | Child abuse reports and health outcomes for infants including emergency room visits, immunisation status and weight. and their parents | Those who completed a full year of the Bellevue Hospital Adolescent Program had some significantly improved measures compared to those who did not, with fewer child abuse reports and more well-baby visits, more immunisations and earlier referral for developmental delays. There was additional health benefits for the adolescent mothers noted as well. |

| McKelvey (2012) | Quantitative | Quants - quasi-experimental, longitudinal (measures at baseline then every 6 months over 24 months), intervention and CAU. | Parenting and child rearing attitudes. | The Thrive Program participants had less inappropriate expectations of children, less strong beliefs in the use of corporal punishment and less reversing of parent-child family roles. However, there was no effect for empathy towards children's needs or oppressing children's power and independence. |

| Nicolson (2013) | Quantitative | Quants - pilot quasi-experimental design with intervention and CAU, blind coded assessors | Mother-infant interaction at age 4 months. | AMPLE intervention effect was evident for emotional availability and separation-reunion as well as maternal non-intrusiveness and maternal non-hostility. |

| Paine (2020) | RCT | Quants - observational sub study of RCT comparing intervention to CAU. | Internal state language (referencing cognitions, desires, emotions, intentions, preferences, physiology and perception) reflecting quality of maternal communication and emotional attunement. | No significant differences were found between Family Nurse Partnership (FNP) and CAU groups in the frequency of maternal internal state language during mother–child interactions. Factors associated with fewer internal state references included higher deprivation scores and mothers not being in education, employment, or training, while positive predictors included being friends with the child’s father and higher maternal mean length of utterance (MLU). Multivariate analysis confirmed that mothers' relationship with the father and MLU were significantly associated with increased use of internal state language. |

| Riva Crugnola (2016) | Mixed | Mixed - quasi-experimental pilot with intervention and control; case study | Maternal sensitivity, parenting style and emotional regulation in both adolescents and mothers at 3, 6, and 9 months. | PRERAYMI participants showed significantly improved maternal sensitivity and decreased controlling styles, with positive effects on infant cooperation, reduced passivity, and increased time spent in coordinated play and affective matches, especially within the first six months. Dyads in the intervention group demonstrated greater capacity for repairing mismatches and maintaining positive interactions compared to the control group, which showed declines in sensitivity, increases in controlling styles, and more mismatched states over time. |

| Riva Crugnola (2021) | Quantitative | Quants - quasi-experimental with intervention and control and pre/post design. | Maternal mind-mindedness and styles of interaction evaluated at infant aged 3 months and 9 months. | The PRERAYMI intervention significantly improved outcomes with increases in attuned mind-related comments, overall verbalizations, maternal sensitivity, and infant cooperative style, while reducing non-attuned and controlling behavour. No changes were observed in the control group. Neither maternal attachment nor childhood experiences of maltreatment significantly moderated the intervention's effects on mind-mindeness or mother-infant interaction styles. |

| Rispoli (2017) | Mixed | Mixed - case study and quantitative pre-post observational data. | Parental positive affect, responsiveness, verbalisations to help child self-regulate and social initiations towards child. | The PIWI-T intervention is acceptable to teachers, can be implemented with fidelity, and has the potential to increase positive caregiving practices for adolescent parents with the largest effects for responsiveness and quality of verbalisations. |

| Robling (2016) | RCT | RCT - Pragmative, non-blinded, random assignment, parallel-group to intervention or care as usual. | Emergency attendance and hospital admission for child in first 24 months | No evidence of benefit from Family Nurse Partnership intervention on smoking and other addictions or on child emergency admissions. |

| : Rokhanawati (2023) | Quantitative | Quants - quasi-experimental with intervention and control and pre/post design. | Parenting self-efficacy and behaviour, growth and development of children. | Compared with the control group, the PPE intervention group reported significantly better parenting self-efficacy, parenting behaviour, children’s growth, and children’s cognitive and language development with very small effects on motor development. |

| Schaffer (2012) | Descriptive | Quants - descriptive, intervention compared to all teens in the metro area. | Maternal-infant bonding and attachment and infant growth and development | MVNA participants were supported with parenting skills and child development, with 95% of children up-to-date on immunizations, 92% with normal ASQ:SE scores, and significant improvements in maintaining a safe home environment and responsiveness to babies, alongside high participant satisfaction (92% recommending the program). |

| Stiles (2010) | Mixed | Mixed methods - Descriptive case study & pre/post design. | Maternal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, self-concept, parenting stress at post-test. | Participant gained confidence in parenting abilities and increased maternal sensitivity to her infant. There was no change in her depression and her anxiety increased. Self-concept, parenting stress and social support all improved. |

| Suess (2016) | Quantitative | Quants - quasi-experimental design with allocation to intervention or CAU and data collection at 12 & 24 months. | Mother- infant attachment style, parenting attitudes, maternal depression. | Significant attachment results (increased security, decreased disorganization) were evident at 12 months and at 24 months in the STEEPb intervention group, even though they had higher risk factors. At the end of intervention, STEEPb group mothers showed significant less risky child rearing attitudes, particularly in empathy and valuing children's autonomy. Depression was not affected. |

| Tua (2018) | Quantitative | Quants - quasi-experimental with pre-post design and comparison to control group. | Responsible parenting skills (no child negligence or abuse records), co-parenting practices. | There was a significant change in nurturing family environments between pre and post for the Family Incubator Model intervention participants. |

| Valades (2021) | RCT | RCT - pilot study with random assignment to intervention or CAU, blind assessment, pre-post design. | Parental sensitivity, infant emotional regulation. | Thula Sana had a positive impact on maternal sensitivity and infants showed more regulated behaviour, more attempts to restore communication and more social and goal-directed behaviour. |

| Williams (2013) | Quantitative | Quants - pre-post design pilot, no control group | Dysfunctional parenting style - laxness, overactivity, verbosity. | There was no statistically significant difference between pre and post for parenting style for Incredible Years participants. |

| Citation | Methodology | Program Name | Score/5 | S12 | S23 | S34 | S45 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alarcão (2021) | RCT | Primeiros Laços | 4 | X | X | X | X |

| Barlow (2013) | RCT | Family Spirit Program | 3 | X | X | X | X |

| Barr (2011) | Mixed | The Baby Elmo Program | 4 | X | X | X | X |

| Barr (2014) | Quantitative | The Baby Elmo Program | 3 | X | X | X | X |

| Berry (2022) | Quantitative | N/A | 3 | X | X | X | |

| Bohr (2014) | Quantitative | Right From the Start | 1 | X | X | X | X |

| Cavallaro (2023) | Quantitative | Family Nurse Partnership | 4 | X | X | X | X |

| Cox (2019) | RCT | Office of Adolescent Pregnancy Programs | 3 | X | X | X | |

| Demeusy (2021) | Quantitative | Building Healthy Children | 4 | X | X | X | X |

| Elliott (2020) | Mixed | Video Interaction Guidance (VIG) | 3 | X | X | X | |

| Fatori (2020) | RCT | Primeiros Laços | 4 | X | X | X | X |

| Fatori (2021) | RCT | Primeiros Laços | 5 | X | X | X | X |

| Firk (2021) | RCT | STEEP-b | 2 | X | X | X | |

| Florsheim (2012) | Quantitative | Young Parenthood Program | 3 | X | X | X | X |

| Hans (2013) | RCT | Chicago Doula Project | 4 | X | X | X | |

| Hasani (2024) | Quantitative | SATIR Approach | 2 | X | X | ||

| P19: Hubel (2018) | Quantitative | SafeCare | 3 | X | X | X | |

| In-iw (2017) | Descriptive | Young Family Clinic | 1 | X | X | ||

| Kachingwe (2021) | Mixed | The Young Women's Christian Association of Malawi | 2 | X | X | X | |

| Long (2018) | Mixed | Theraplay | 2 | X | |||

| Mackinnon (2014) | Qualitative | Pskov Positive Parenting Program | 3 | Can't tell | X | ||

| McHugh (2017) | Quantitative | Bellevue Hospital Adolescent Parenting Program | 2 | X | X | ||

| McKelvey (2012) | Quantitative | Thrive Program (derived from the Healthy Families America model) | 1 | X | X | X | X |

| Nicolson (2013) | Quantitative | AMPLE Intervention | 4 | X | X | X | |

| Paine (2020) | RCT | Family Nurse Partnership | 2 | X | X | X | X |

| Rispoli (2017) | Mixed | Parents Interacting with Infants - Teen version (PIWI-T) | 3 | X | X | X | X |

| Riva Crugnola (2016) | Mixed | PRERAYMI | 4 | X | X | X | X |

| Riva Crugnola (2021) | Quantitative | PRERAYMI | 4 | X | X | X | X |

| Robling (2016) | RCT | Family Nurse Partnership | 5 | X | X | X | X |

| Rokhanawati (2023) | Quantitative | Parenting Peer Education Model | 4 | X | X | X | |

| Schaffer (2012) | Descriptive | MNVA Pregnant and Parenting Teen Program | 5 | X | X | ||

| Stiles (2010) | Mixed | Promoting First Relationships | 1 | X | X | ||

| Suess (2016) | Quantitative | STEEP-b (Steps Toward Effective and Enjoyable Parenting) | 3 | X | X | X | X |

| Tua (2018) | Quantitative | Family Incubator Model | 2 | X | |||

| Valades (2021) | RCT | Thula Sana | 5 | X | X | X | X |

| Williams (2013) | Quantitative | Incredible Years | 2 | X | X |

- 2

- Are there clear research questions?

- 3

- Do the collected data address the research questions?

- 4

- Is the description of the method sufficient for replication?

- 5

- Does the intervention have sufficient standardisation to enable replication (is it manualised)?

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).