Submitted:

23 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

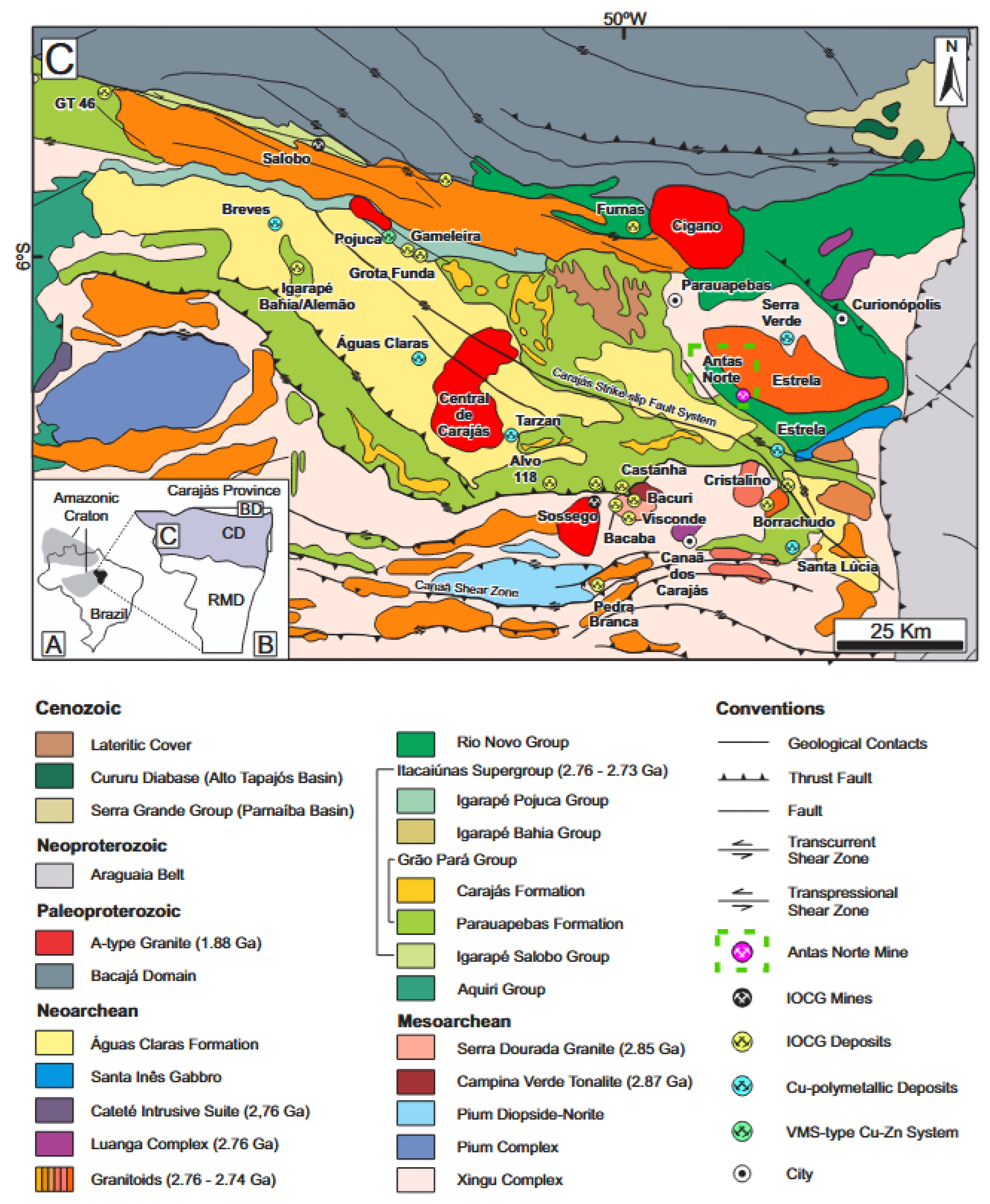

2. Regional Geological Context

3. Iron Oxide Copper-Gold (IOCG) Deposits in the Carajás Province

- Metavolcano-sedimentary host rocks from the Itacaiúnas Supergroup;

- Strong structural control, often associated with shear zones;

- Proximity to diverse intrusive suites (granite, diorite, gabbro);

- Abundant hydrothermal breccias;

- Intense sodic, potassic, and magnetite alterations;

- Polymetallic enrichment (REE, P, U, Ni, W, Sn, Co, Pd);

- Wide variation in formation temperatures (100–570°C) and salinities (0–69 wt.% NaCl eq.).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Fieldwork, Petrography, and SEM Analyses

4.2. 3D Geological Modeling and Structural Analysis

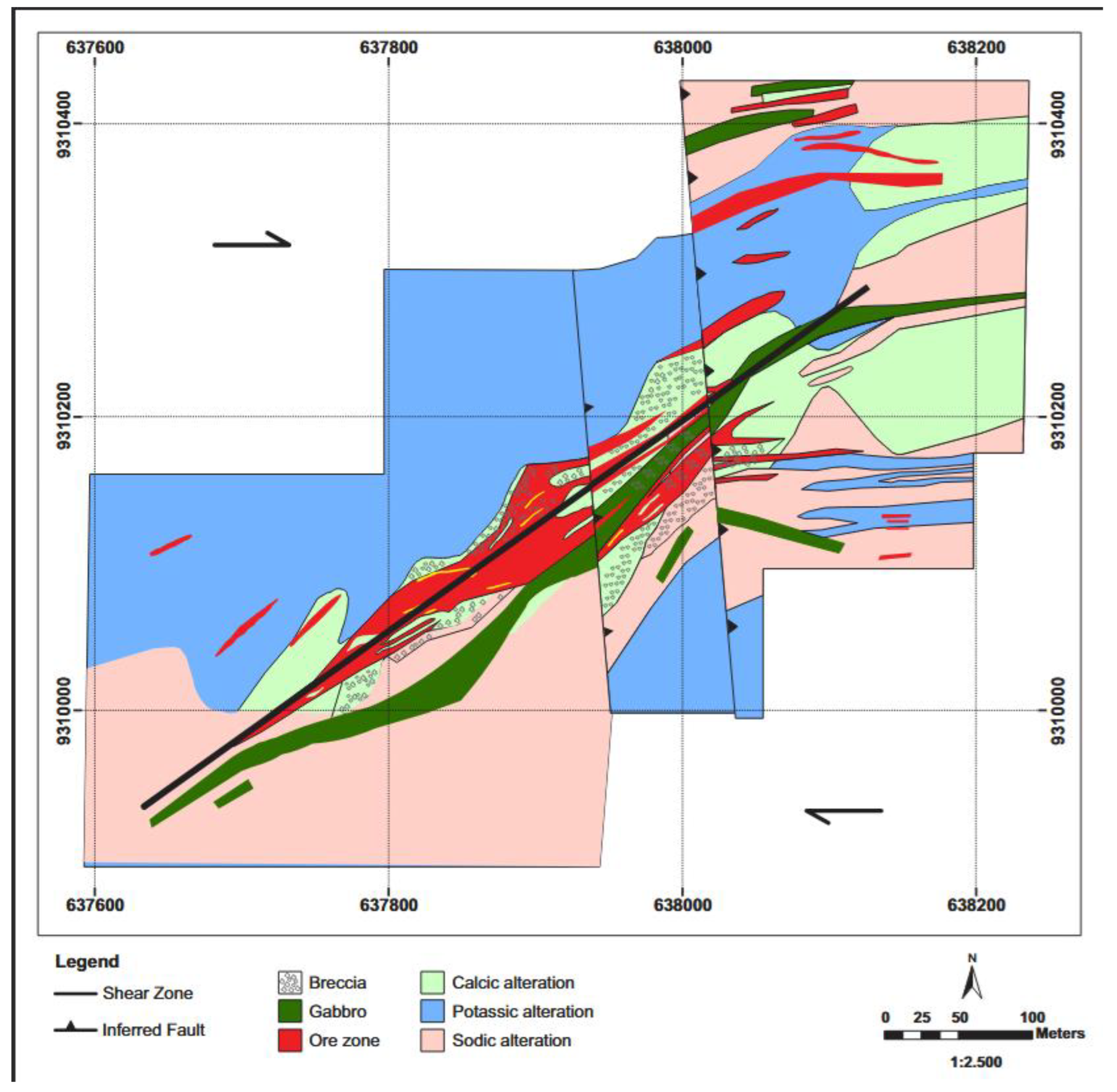

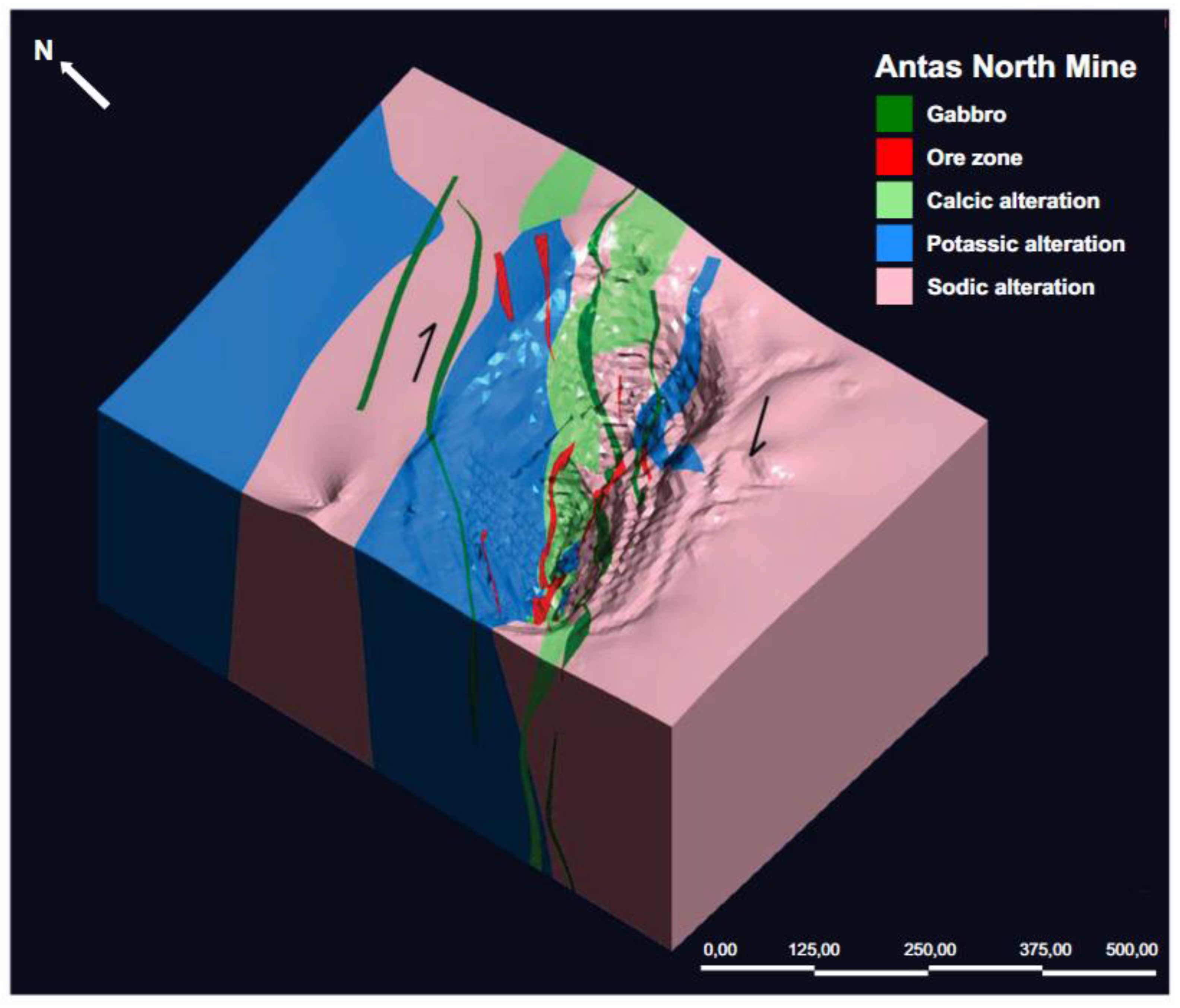

- Geological surface maps,

- Drill hole datasets (totaling 30,657.55 meters),

- Detailed topographic surveys.

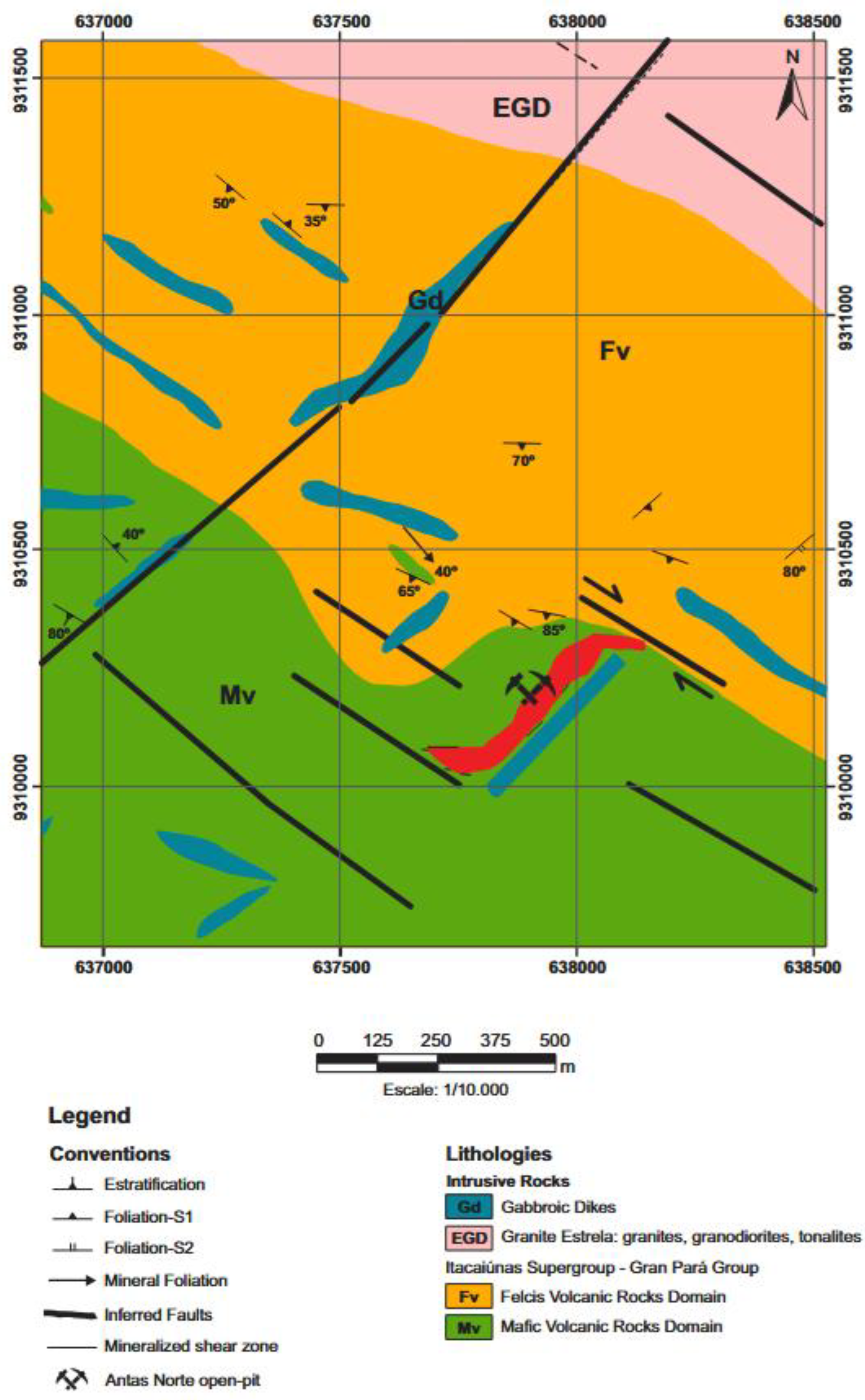

5. Local Geology

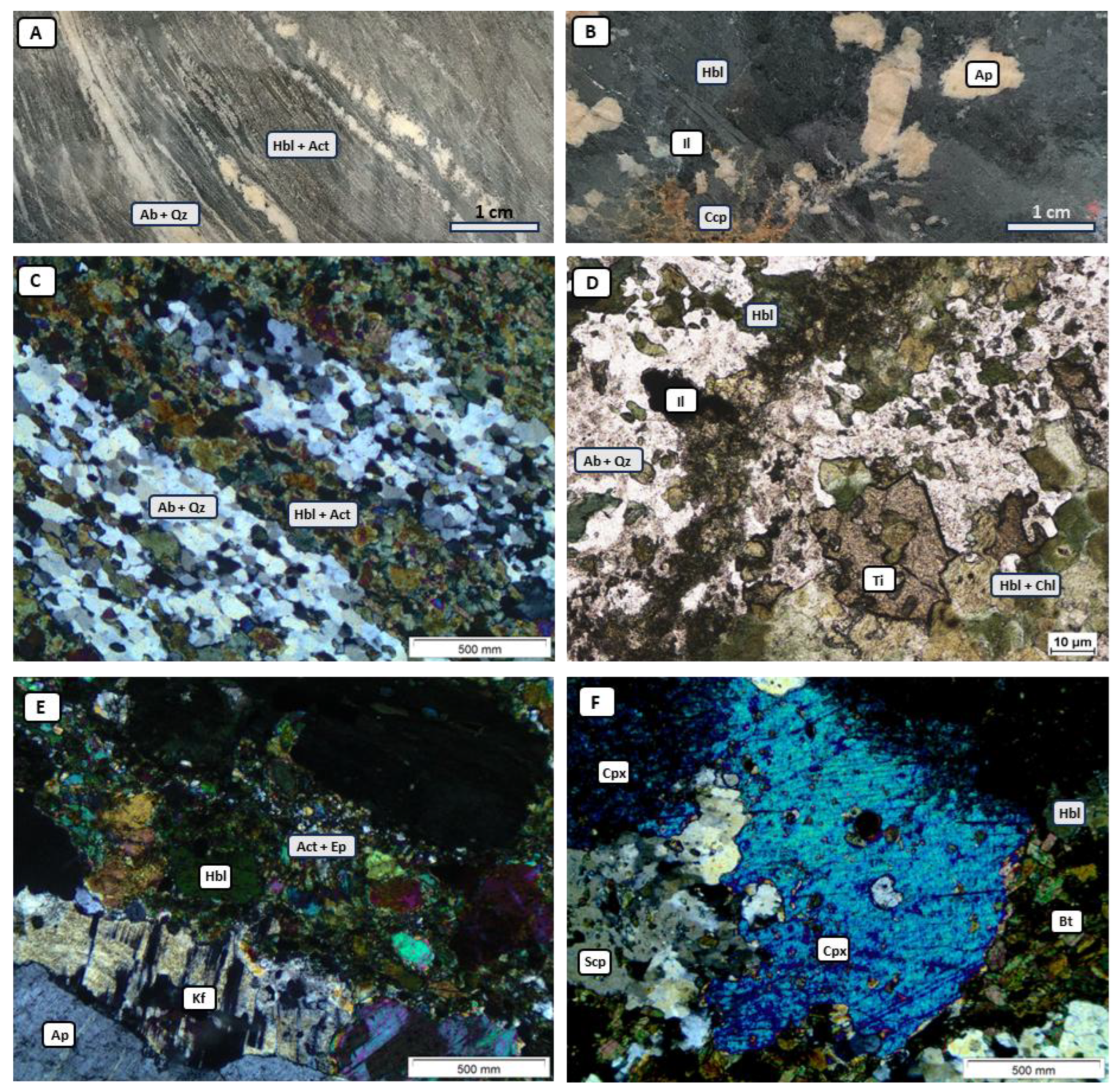

5.1. Host Rocks

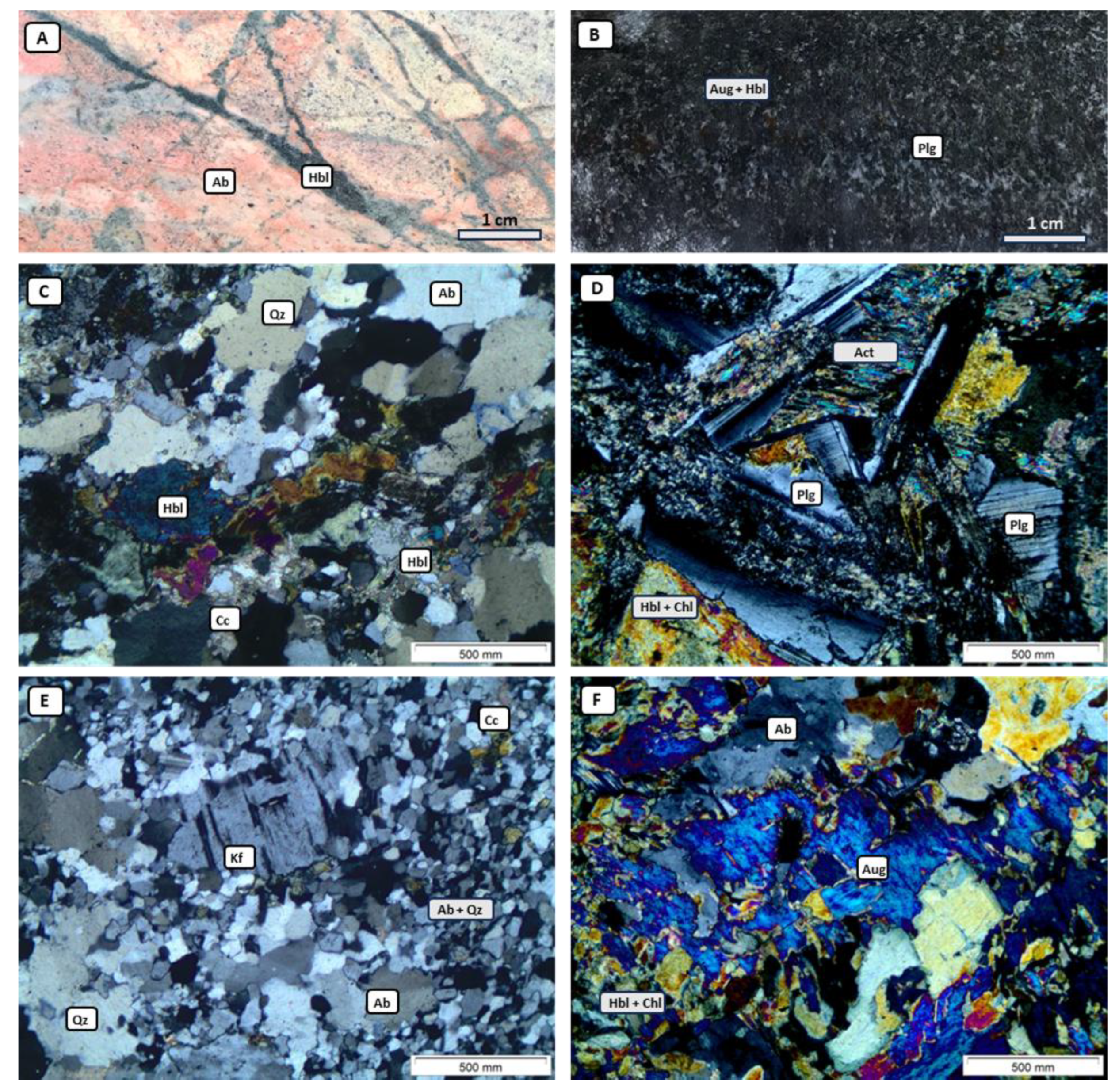

5.2. Felsic Volcanic Rocks

5.3. Gabbro Dikes

6. Hydrothermal Alterations

- Sodic alteration: Dominated by albite replacement, pervasive in host rocks, particularly in felsic volcanics.

- Potassic alteration: Characterized by biotite and scapolite replacing amphiboles and feldspars, centered around mineralized zones.

- Calcic alteration: Marked by amphibole (hornblende, actinolite) and apatite formation, closely associated with copper mineralization.

- Silicification: Pervasive quartz veining and replacement, overprinting previous alteration stages.

- Propylitic alteration: Development of chlorite, epidote, and calcite, particularly at the periphery of ore zones.

7. Mineralization

- Massive sulfide ore: Dominant in the central portions of the orebody, primarily composed of chalcopyrite with subordinate pyrrhotite and pyrite.

- Brecciated sulfide ore: Present along the margins of massive zones, associated with brecciated hydrothermalized host rocks, where sulfides infill breccia matrices.

- Veins and veinlets: Less volumetrically significant, predominantly composed of chalcopyrite, pyrrhotite, and minor ilmenite, crosscutting earlier alteration zones.

8. Geocronology

9. Structural Geology

- Sn foliation: A pervasive mylonitic foliation defined by the preferred orientation of amphiboles, plagioclase, and biotite, which trends NNE–SSW and dips ESE.

- Sn+1 foliation: A later foliation characterized by the alignment of hydrothermal minerals, particularly oriented mafic minerals surrounding quartz and feldspar porphyroclasts, which trends ENE–WSW and dips SSE.

10. 3D Geological Modeling

- Sodic alteration (albite) dominates at regional scale;

- Potassic alteration (biotite + scapolite) surrounds the mineralized core;

- Calcic alteration (amphibole + apatite) is closely associated with copper mineralization.

11. Discussion

12. Conclusions

- Massive sulfide bodies,

- Breccia matrix sulfide infill,

- Sulfide veins and veinlets.

References

- Araújo, O.J.B.; Maia, R.G.N. 1991. Serra dos Carajás, folha SB.22-ZA, Estado do Pará. Programa Levantamentos Geológicos Básicos do Brasil. Companhia de Pesquisa de Recursos Minerais. 136.

- Araújo, O.J.B.; Maia, R.G.N.; Jorge-João, X.S.; Costa, J.B.S. 1988. A megaestruturação da folha Serra dos Carajás. In: Congr. Latino-Americano de Geologia, 7, Proceedings, 324–333.

- Arias, M.; Nuñez, P.; Arias, D.; Gumiel, P.; Castañón, C.; Fuertes-Blanco, J.; Martin-Izard, A. 3D Geological Model of the Touro Cu Deposit, A World-Class Mafic-Siliciclastic VMS Deposit in the NW of the Iberian Peninsula. Minerals 2021, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusto, R.A.; Monteiro, L.V.S.; Xavier, R.; Souza Filho, C.R. Zonas de alteração hidrotermal e paragênese do minério de cobre do Alvo Bacaba, Província Mineral de Carajás (PA). Revista Brasileira de Geociências 2008, 38, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelar, V.G.; Lafon, J.M.; Correia Jr, F.C.; Macambira, E.M.B. O magmatismo arqueano da região de Tucumã—Província Mineral De Carajás: Novos resultados geocronológicos. Revista Brasileira de Geociências 1999, 29, 453–460. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, C.E.M.; Dall’Agnol, R.; Barbey, P.; Boullier, A.M. Geochemistry of the Estrela Granite Complex, Carajás region, Brazil: an example of an Archaean A-type granitoid. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 1997, 10, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.E.M.; Macambira, M.J.B.; Barbey, P.; Scheller, T. Dados isotópicos Pb-Pb em zircão (evaporação) e Sm-Nd do Complexo Granítico Estrela, Província Mineral de Carajás, Brasil: Implicações petrológicas e tectônicas. Revista Brasileira de Geociências 2004, 34, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.D. Iron Oxide(-Cu-Au-REE-P-Ag-U-Co) Systems. In Treatise on Geochemistry: Second Edition 2013, 13, 515–541. Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.D.; Johnson, D.A. 2004. Footprints of Fe-oxide(-Cu-Au) systems. In SEG 2004: Predictive Mineral Discovery Under Cover. Centre for Global Metallogeny, Spec. Pub. 33, The University of Western Australia, 112–116.

- Botelho, N.F.; Moura, M.A.; Teixeira, L.M.; Olivo, G.R.; Cunha, L.M.; Santana, M.U. 2005. Caracterização geológica e metalogenética do depósito de Cu ± (Au, W, Mo, Sn) Breves, Carajás. In: Marini OJ, Queiroz ET, Ramos BW (eds). Caracterização do Depósitos Minerais em Distritos Mineiros da Amazônia. DMNP-CT-mineral / FINEPADIMB, 339–389.

- Buddington, A.F.; Lindsley, D.H. Iron-titanium oxide minerals and synthetic equivalents. Journal of Petrology 1964, 5, 310–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, G.; Blenkinsop, T.; Chang, Z.; Huizenga, J.M.; Lilly, R.; McLellan, J. Delineating the structural controls on the genesis of iron oxide–Cu–Au deposits through implicit modelling: a case study from the e1 group, Cloncurry district, Australia. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2017, 453, 349–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriveau, L. 2007. Iron oxide copper-gold deposits: A Canadian perspective. In W. D. Goodfellow (ed.), Mineral Deposits in Canada: A Synthesis of Major Deposit Types, District Metallogeny, the Evolution of Geological Provinces and Exploration Methods, 307–328.

- Craveiro, G.S.; Villas, R.N.; Costa Silva, A.R. Depósito Cu-Au Visconde, Carajás (PA): geologia e alteração hidrotermal das rochas encaixantes. Revista Brasileira de Geociências 2012, 42, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craveiro, G.S.; Xavier, R.P.; Villas, R.N.N. The Cristalino IOCG deposit: an example of multi-stage events of hydrothermal alteration and copper mineralization. Brazilian Journal of Geology 2019, 49, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docegeo. 1988. Revisão litoestratigráfica da Província Mineral de Carajás—Litoestratigrafia e principais depósitos minerais. In: Cong. Bras. Geol., 35, SBG, 11–54.

- Domingos, F.H.G. 2009. The Structural Setting of the Canaã dos Carajás Region and Sossego-Sequeirinho Deposits, Carajás Brazil. Doctor of Philosophy thesis. University of Durham, Durham, 483.

- Feio, G.R.L.; Dall’Agnol, R.; Dantas, E.L.; Macambira, M.J.B.; Gomes, A.C.B.; Sardinha, A.S.; Oliveira, D.C.; Santos, R.D.; Santos, P.A. Geochemistry, geochronology, and origin of the Neoarchean Planalto Granite suite, Carajás, Amazonian craton: A-type or hydrated charnockitic granites? Lithos 2012, 151, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feio, G.R.L.; Dall’Agnol, R.; Dantas, E.L.; Macambira, M.J.B.; Santos, J.O.S.; Althoff, F.J.; Soares, J.E.B. Archean granitoid magmatism in the Canaã dos Carajás area: Implications for crustal evolution of the Carajás province, Amazonian craton, Brazil. Precambrian Research 2013, 227, 157–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira Filho, C.F.; Cançado, F.; Correa, C.; Macambira, E.M.B.; Junqueira-Brod, T.C.; Siepierski, L. 2007. Mineralizações estratiformes de PGE-Ni associadas a complexos acamadados em Carajás: os exemplos de Luanga e Serra da Onça. In: Rosa-Costa L.T., Klein E.L., Viglio E.P. (eds.). Contribuições à Geologia da Amazônia. SBG-Núcleo Norte, Belém, p. 1–14.

- Fournier, R.O. Active hydrothermal systems as analogues of fossil systems. In: Eaton, G., (eds.). The Role of Heat in the Development of Energy and Mineral Resources in the Northern Basin and Range Province. Geothermal Resources Council Special Report 1983, 13, 263–284. [Google Scholar]

- Galarza, M.A.; Macambira, M.J.B.; Moura, C.A.V. 2003. Geocronologia Pb-Pb e Sm–Nd das rochas máficas do depósito Igarapé Bahia, Província Mineral de Carajás (PA). 7º Simpósio de Geologia da Amazônia, [CD-ROM].

- Garcia, V.B.; Schutesky, M.E.; Oliveira, C.G.; Whitehouse, M.J.; Hühn, S.R.B.; Augustin, C.T. The Neoarchean GT-34 Ni deposit, Carajás mineral Province, Brazil: An atypical IOCG-related Ni sulfide mineralization. Ore Geology Reviews 2020, 127, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustina, M.E.S.D.; Oliveira, C.G. From the roots to the roof? A verticalization model for the Carajás IOCG Province, Brazil. Ore Geology Reviews 2020, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Grainger, C.J.; Groves, D.I.; Tallarico, F.H.B.; Fletcher, I.R. Metallogenesis of the Carajás Mineral Province, Southern Amazon Craton, Brazil: Varying styles of Archean through Paleoproterozoic to Neoproterozoic base- and precious-metal mineralization. Ore Geology Reviews 2008, 33, 451–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, D.I.; Bierlein, F.P.; Meinert, L.D.; Hitzman, M.W. Iron Oxide Copper-Gold (IOCG) Deposits through Earth History: Implications for Origin, Lithospheric Setting, and Distinction from Other Epigenetic Iron Oxide Deposits. Economic Geology 2010, 105, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad-Martim, P.M.; Souza Filho, C.R.; Carranza, E.J.M. Spatial analysis of mineral deposit distribution: A review of methods and implications for structural controls on iron oxide-copper-gold mineralization in Carajás, Brazil. Ore Geology Reviews 2017, 81, 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggerty, S. Opaque mineral oxides in terrestrial igneous rocks. Mineralogical Society of America. Short Course Notes 1976, 3, 101–300. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, D.W. Iron oxide copper (-gold) deposits: their position in the deposit spectrum and modes of origin. In Hydrothermal iron oxide copper-gold and related deposits. A global perspective 2000, 1, 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hirata, W.K.; Rigon, J.C.; Kadekaru, K.; Cordeiro, A.A.C.; Meireles, E.A. 1982. Geologia Regional da Província Mineral de Carajás. Simpósio de Geologia da Amazônia, 1st, Belém, Abstracts, 100-110.

- Hitzman, M.W. Iron oxide-Cu-Au deposits: what, where, when and why? In T. M. Porter (Ed.), Hydrothermal iron oxide copper-gold and related deposits. A global perspective, Australian Mineral Foundation 2000, 1, 9–25.

- Hitzman, M.W.; Oreskes, N.; Einaudi, M.T. Geological characteristics and tectonic setting of Proterozoic iron oxide (Cu-U-Au-REE) deposits. Precambrian Research 1992, 58, 241–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, R.; Pinheiro, R. The anatomy of shallow-crustal transpressional structures: insights from the Archean Carajás fault zone, Amazon, Brazil. Journal of Structural Geology 2000, 22, 1105–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.-W.; Beaudoin, G. Textures and Chemical Compositions of Magnetite from Iron Oxide Copper-Gold (IOCG) and Kiruna-Type Iron Oxide-Apatite (IOA) Deposits and Their Implications for Ore Genesis and Magnetite Classification Schemes. Economic Geology 2019, 114, 953–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hühn, S.R.B.; Silva, A.M.; Ferreira, F.J.F.; Braitenberg, C. Mapping New IOCG Mineral Systems in Brazil: The Vale do Curaçá and Riacho do Pontal Copper Districts. Minerals 2020, 10, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hühn, S.R.B.; Souza, C.I. J. , Albuquerque, M.C., Leal, E.D.; Brustolin, V. 1999a. Descoberta do depósito Cu (Au) Cristalino: Geologia e mineralização associada região da Serra do Rabo—Carajás—PA. In: Simpósio de Geologia da Amazônia, 6, Boletim de Resumos, 140–143.

- Hühn, S.R.B.; Macambira, M.J.B.; Dall’Agnol, R. Geologia e geocronologia Pb-Pb do Granito Alcalino Planalto, Região da Serra do Rabo, Carajás-PA. In: Simpósio de Geologia da Amazônia, Boletim de Resumos 1999, 6, 463–466. [Google Scholar]

- Hühn, S.R.B.; Nascimento, J.A.S. 1997. São os depósitos cupríferos de Carajás do tipo Cu-Au-U-ETR? In: Costa, M.L.; Angélica, R.S. (Eds.) Contribuições à Geologia da Amazônia. FINEP, SGB-NO, 143-160.

- Kampmann, T.C.; Stephens, M.B.; Weihed, P. 3D modelling and sheath folding at the Falun pyritic Zn-Pb-Cu-(Au-Ag) sulphide deposit and implications for exploration in a 1.9 Ga ore district, Fennoscandian Shield, Sweden. Mineral Deposita 2016, 51, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; Jiang, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z. Combining 3D Geological Modeling and 3D Spectral Modeling for Deep Mineral Exploration in the Zhaoxian Gold Deposit, Shandong Province, China. Minerals 2022, 12, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, Z.G.; Teixeira, J.B.G. 1999. Ore genesis at the Salobo copper deposit, Serra dos Carajás. In: Silva M. G., Misi A. (eds.). Base Metal Deposits of Brazil. MME/CPRM/DNPM, Belo Horizonte, 33-43.

- Lindenmayer, Z.G.; Pimentel, M.M.; Ronchi, L.H.; Althoff, F.J.; Laux, J.H.; Araújo, J.C.; Fleck, A.; Baecker, C.A.; Carvalho, D.B.; Nowatzki, A.C. 2001b. Geologia do depósito de Cu-Au de Gameleira Serra dos Carajás, Pará. In: Jost H., Brod J.A., Quieroz E.T. (eds.) Caracterização de depósitos auríferos em distritos mineiros brasileiros. Brasilia, ADIMB-DNPM, p. 79-139.

- Lindenmayer, Z.G. 2003. Depósito de Cu–Au do Salobo, Serra dos Carajás: Uma revisão. In: L.H. Ronchi and F.J. Althoff (eds.). Caracterização e modelamento de depósitos minerais. São Leopoldo, Editora Unisinos, 69–98.

- Lindenmayer, Z.G.; Fleck, A.; Gomes, C.H.; Santos, A.B.S.; Caron, R.; Paula, F.C.; Laux, J.H.; Pimental, M.M.; Sardinha, A.S. 2005. Caracterização geológica do Alvo Estrela (Cu-Au), Serra dos Carajás, Pará. In: Marini OJ, Queiroz ET, Ramos BW (eds). Caracterização dos depósitos minerais em distritos mineiros da Amazônia. DMNPCT-mineral/FINEP-ADIMB, 157–225.

- Macambira, E.B.M.; Ferreira Filho, C.F. 2005. Exploration and origin of stratiform PGE mineralization in the Serra da Onça layered complex, Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil. In: 10th International Platinum Symposium Extended Abstract, Oulu.

- Macambira, E.B.M.; Ferreira Filho, C.F. 2002. Fracionamento magmático dos corpos máfico ultramáficos da Suíte Intrusiva Cateté—sudeste do Pará. In: Klein EL, Vasquez ML, Rosa-Costa LT (Eds) Contribuições à geologia da Amazônia. Belém, SBG-Núcleo Norte, 105-114.

- Machado, N.; Krough, T.E.; Lindenmayer, Z.G. U–Pb geochronology of Archean magmatism and basement reactivation in the Carajás Area, Amazon Shield, Brazil. Precambrian Res. 1991, 49, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, E.T.; Ferreira Filho, C.F.; Oliveira, D.P. The Luanga deposit, Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil: Different styles of PGE mineralization hosted in a medium-size layered intrusion. Ore Geology Reviews 2020, 118, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansur, E.T. , Ferreira Filho, C.F., 2016. Magmatic structure and geochemistry of the Luanga Mafic-Ultramafic Complex: Further constraints for the PGE-mineralized magmatism in Carajás, Brazil. Lithos. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Izard, A.; Arias, D.; Arias, M.; Gumiel, P.; Sanderson, D.J.; Castañón, C.; Lavandeira, A.; Sanchez, J. A new 3D geological model and interpretation of structural evolution of the world-class Rio Tinto VMS deposit, Iberian Pyrite Belt (Spain). Ore Geol. Rev. 2015, 71, 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschik, R.; Mathur, R.; Ruiz, J.; Leveille, R.A.; Almeida, A.-J. Late Archean Cu-Au-Mo mineralization at Gameleira and Serra Verde, Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil: constraints from Re-Os molybdenite ages. Mineralium Deposita 2005, 39, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, G.H.C.; Monteiro, L.V.S.; Moreto, C.P.N.; Xavier, R.P.; Silva, M.A.D. Paragenesis and evolution of the hydrothermal Bacuri iron oxide-copper-gold deposit, Carajás Province (PA). Brazilian Journal of Geology 2014, 44, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, G.H.C. 2011. Contexto geológico e evolução metalogenética do depósito de cobre Bacuri, Província Mineral de Carajás. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso, Instituto de Geociências, Universidade de Campinas, 66.

- Monteiro, L.V.S.; Xavier, R.P.; Carvalho, E.R.; Hitzman, M.W.; Johnson, C.A.; Souza Filho, C.R.; Torresi, I. Spatial and temporal zoning of hydrothermal alteration and mineralization in the Sossego iron oxide-copper-gold deposit, Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil: Paragenesis and stable isotope constraints. In Mineralium Deposita 2008, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, L.V.S.; Xavier, R.P.; Hitzman, M.W.; Juliani, C.; Souza Filho, C.R.; Carvalho, E.R. Mineral chemistry of ore and hydrothermal alteration at the Sossego iron oxide–copper–gold deposit, Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil. Ore Geology Reviews 2008, 34, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, L.V.S.; Xavier, R.P.; Souza Filho, C.R.; Augusto, R.A. 2007. Aplicação de isótopos estáveis ao estudo dos padrões de distribuição das zonas de alteração hidrotermal associados ao sistema de óxido de ferro-cobre-ouro Sossego, Província Mineral de Carajás. In: Congresso Brasileiro de Geoquímica. Atibaia, Sociedade Brasileira de Geoquímica.

- Moreto, C.P.N.; Monteiro, L.V.S.; Xavier, R.P.; Creaser, R.A.; Dufrane, S.A.; Tassinari, C.C.G.; Sato, K. Timing of multiple hydrothermal events in the iron oxide–copper–gold deposits of the Southern Copper Belt, Carajas Province, Brazil. Mineralium Deposita 2015, 50, 517–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreto, C.P.N.; Monteiro, L.V.S.; Xavier, R.P.; Creaser, R.A.; Dufrane, S.A.; Tassinari, C.C.G.; Sato, K.; Kemp, A.I.S.; Amaral, W.S. Neoarchean and Paleoproterozoic iron oxide-copper-gold events at the Sossego deposit, Carajas Province, Brazil, Re-Os and U-Pb geochronological evidence. Economic Geology 2015, 110, 809–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreto, C.P.N. 2013. Geocronologia U-Pb e Re-Os aplicada à evolução metalogenética do Cinturão Sul do Cobre da Província Mineral de Carajás. Tese de Doutorado, Instituto de Geociências, UNICAMP, 216.

- Moreto, C.P.N.; Monteiro, L.V.S.; Xavier, R.P.; Amaral, W.S.; Santos, J.S.S.; Juliani, C.; Souza Filho, C.R. Mesoarchean (3.0 and 2.86 Ga) host rocks of the iron oxide-Cu-Au Bacaba deposit, Carajás Mineral Province: U-Pb geochronology and metallogenetic implications. Mineralium Deposita 2011, 46, 789–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.C.R.; Truckenbrodt, W.; Pinheiro, R.V.L. Formação Águas Claras, Pré-Cambriano da Serra dos Carajás: redescrição e redefinição litoestratigráfica. Bol. Mus. Par. Em. Goeldi. Ciência da Terra 1995, 7, 177–277. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, C.G.; Santos, R.V.; Lafon, J.M. Variação da razão 87Sr/86Sr durante a evolução da zona de cisalhamento aurífera de Diadema, Sudeste do Pará. In: 38 Congresso Brasileiro de Geologia, Camboriú. Resumos Expandidos 1994, 2, 415–416. [Google Scholar]

- Oz Minerals. 2020. Antas North. Mineral Resource and Ore Reserve Statement and Explanatory Notes.

- Oz Minerals. 2022. Pedra Branca. Mineral Resource and Ore Reserve Statement and Explanatory Notes.

- Passchier, C.W.; Trouw, R.A.J. 2005. Microtectonics. Berlin; New York, Springer.

- Pestilho, A.L.S.; Monteiro, L.V.S.; Melo, G.H.C.; Moreto, C.P.N.; Juliani, C.; Fallick, A.E.; Xavier, R.P. Stable isotopes and fluid inclusion constraints on the fluid evolution in the Bacaba and Castanha iron oxide-copper-gold deposits, Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil. Ore Geology Reviews 2020, 121, 103738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidgeon, R.T.; Macambira, M.J.B.; Lafon, J.M. Th-U-Pb isotopic systems and internal structures of complex zircons from an enderbite from the Pium Complex, Carajás province, Brazil: Evidence for the ages of granulite facies metamorphism and the protolith of the enderbite. Chem. Geol. 2000, 166, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.M.; Lindenmayer, Z.G.; Laux, J.H.; Armstrong, R.; Araújo, J.C. Geochronology and Nd geochemistry of the Gameleira Cu–Au deposit, Serra dos Carajás, Brazil: 1.8–1.7 Ga hydrothermal alteration and mineralization. Journal of South American Earth Science 2003, 15, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, R.V.L.; Kadekaru, K.; Soares, A.V.; Freitas, C.; Ferreira, S.N.; Matos, F.M.V. 2013. Carajás, Brazil—a short tectonic review. In: XIII Simpósio de Geologia da Amazônia. Belém, 1086–1089.

- Pinheiro, R.V.L.; Holdsworth, R.E. Reactivation of Archean strike-slip fault systems, Amazon region, Brazil. Journal of the Geological Society 1997, 154, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, R.V.L.; Holdsworth, R.E. Evolução tectonoestratigráfica dos sistemas transcorrentes Carajás e Cinzento, Cinturão Itacaiúnas, na borda leste do Cráton Amazônico. Pará. Rev. Bras. Geociências 2000, 30, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, P.J.; Taylor, R.G.; Peters, L.; Matos, F.; Freitas, C.; Saboia, L.; Huhn, S.R.B. 2018. 40Ar-39Ar dating of Archean iron oxide Cu-Au and Paleoproterozoic granite-related Cu-Au deposits in the Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil: implications for genetic models. Miner. Deposita, 1–18.

- Reed, M.H. 1997. Hydrothermal alteration and its relationship to ore fluid composition. In: Barnes H.L. (ed.). Geochemistry of Hydrothermal Ore Deposits, Wiley, New York, 303–365.

- Réquia, K.; Stein, H.; Fontboté, L.; Chiaradia, M. Re–Os and Pb–Pb geochronology of the Archean Salobo iron oxide copper–gold deposit, Carajás Mineral Province, northern Brazil. Mineralium Deposita 2003, 38, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigon, J.C.; Munaro, P.; Santos, L.A.; Nascimento, J.A.S.; Barreira, C.F. (2000) Alvo 118 copper–gold deposit: geology and mineralization, Serra dos Carajás, Pará, Brazil. 31st International Geological Congress, Rio de Janeiro. SBG, Abstract Volume, [CD-ROM].

- Rimstidt, J.D. (1997) Gangue mineral transport and deposition. In: Barnes, H.L. (ed.) Geochemistry of Hydrothermal Ore Deposits, 3rd ed. Wiley, New York, pp. 435–487.

- Roberts, D.E.; Hudson, G.R.T. The Olympic Dam copper-uranium-gold deposit, Roxby Downs, South Australia. Economic Geology 1983, 78, 799–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Mustafa, M.A.; Simon, A.C.; Real, I.; Thompson, J.F.H.; Bilenker, L.D.; Barra, F.; Bindeman, I.; Cadwell, D. A Continuum from Iron Oxide Copper-Gold to Iron Oxide-Apatite Deposits: evidence from Fe and O stable isotopes and trace element chemistry of magnetite. Economic Geology 2020, 115, 1443–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.O.S. (2003) Geotectônica do Escudo das Guianas e Brasil-Central. In: Bizzi, L.A. (ed.) Geologia, Tectônica e Recursos Minerais do Brasil: Texto, Mapas e SIG. CPRM, Brasília, pp. 169–226.

- Sardinha, A.S.; Barros, C.E.M.; Krymsky, R. Geology, geochemistry, and U-Pb geochronology of the Archean (2.74 Ga) Serra do Rabo granite stocks, Carajás Metallogenetic Province, northern Brazil. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 2006, 20, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, A.C.; Knipping, J.; Reich, M.; Barra, F.; Deditius, A.P.; Bilenker, L.; Childress, T. Kiruna-type iron oxide-apatite (IOA) and iron oxide copper-gold (IOCG) deposits form by a combination of igneous and magmatic-hydrothermal processes: Evidence from the Chilean iron belt. Society of Economic Geologists, Special Publication 2018, 21, 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Siepierski, L. (2016) Geologia, petrologia e potencial para mineralizações magmáticas dos corpos máfico-ultramáficos da região de Canaã dos Carajás, Província Mineral de Carajás, Brasil. PhD Thesis, Universidade de Brasília.

- Sillitoe, R.H. Iron oxide-copper-gold deposits: An Andean view. Mineralium Deposita 2003, 38, 787–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.M.G.; Villas, R.N. The Águas Claras Cu-sulfide ± Au deposit, Carajás region, Pará, Brazil: geological setting, wall-rock alteration and mineralizing fluids. Revista Brasileira de Geociências 1998, 28, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skirrow, R.G. Iron oxide copper-gold (IOCG) deposits—A review (part 1): Settings, mineralogy, ore geochemistry and classification. Ore Geology Reviews 2022, 140, 104569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skirrow, R.G.; Murr, J.; Schofield, A.; Huston, D.L.; Van der Wielen, S.; Czarnota, K.; Coghlan, R.; Highet, L.M.; Connolly, D.; Doublier, M.; Duan, J. Mapping iron oxide Cu-Au (IOCG) mineral potential in Australia using a knowledge-driven mineral systems-based approach. Ore Geology Reviews 2019, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skirrow, R.G.; Walshe, J.L. Reduced and oxidized Au-Cu-Bi iron oxide deposits of the Tennant Creek Inlier, Australia: An integrated geologic and chemical model. Economic Geology 2002, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, S.R.B.; Macambira, M.J.B.; Sheller, T. (1996) Novos dados geocronológicos para os granitos deformados do Rio Itacaiúnas (Serra dos Carajás, PA); implicações estratigráficas. In: 5º Simpósio de Geologia da Amazônia, Belém, pp. 380–383.

- Tallarico, F.H.B.; Figueiredo, B.R.; Groves, D.I.; Kositcin, N.; McNaughton, N.J.; Fletcher, I.R.; Rego, J.L. (2005) Geology and SHRIMP U-Pb geochronology of the Igarapé Bahia deposit, Carajás copper-gold belt, Brazil: An Archean (2.57 Ga) example of Iron-Oxide Cu-Au-(U-REE) mineralization. Economic Geology, 100th Anni, 7–28.

- Tallarico, F.H.B.; McNaughton, N.J.; Groves, D.I.; Fletcher, I.R.; Figueiredo, B.R.; Carvalho, J.B.; Rego, J.L.; Nunes, A.R. Geological and SHRIMP II U-Pb constraints on the age and origin of the Breves Cu-Au-(W-Bi-Sn) deposit, Carajás, Brazil. Mineralium Deposita 2004, 39, 68–86. [Google Scholar]

- Tallarico, F.H.B. (2003) O cinturão cupro-aurífero de Carajás, Brasil. Tese de Doutorado, Instituto de Geociências, UNICAMP, Campinas, 229.

- Tazava, E.; Oliveira, C.G. (2000) The igarapé Bahia Au-Cu-(REE-U) deposit, Carajás Mineral Province, northern Brazil. In: Porter, T.M. (ed.) Hydrothermal Iron Oxide Copper-Gold & Related Deposits: A Global Perspective. Australian Mineral Foundation, Adelaide, pp. 203–212.

- Teixeira, A.S.; Ferreira Filho, C.F.; Giustina, M.E.S.D.; Araujo, S.M.; Silva, H.H.A.B. Geology, petrology and geochronology of the Lago Grande layered complex: Evidence for a PGE-mineralized magmatic suite in the Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 2015, 64, 116–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, W.; Hamilton, M.A.; Girardi, V.A.V.; Faleiros, F.M.; Ernst, R.E. U-Pb baddeleyite ages of key dyke swarms in the Amazonian Craton (Carajás/Rio Maria and Rio Apa areas): Tectonic implications for events at 1880, 1110 Ma, 535 Ma and 200 Ma. Precambrian Research 2019, 329, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torresi, I.; Bortholoto, D.F.A.; Xavier, R.P.; Monteiro, L.V.S. Hydrothermal alteration, fluid inclusions and stable isotope systematics of the Alvo 118 iron oxide-copper-gold deposit, Carajás Mineral Province (Brazil): Implications for ore genesis. Mineralium Deposita 2012, 47, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendall, A.F.; Basei, M.A.S.; De Laeter, J.R.; Nelson, D.R. SHRIMP U-Pb constraints on the age of the Carajás formation, Grão Pará Group, Amazon Craton. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 1998, 11, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale (2022) Formulário de Relatório Annual 20-F.; Comissão de Valores Mobiliários dos Estados Unidos.

- Vanko, D.A.; Bishop, F.C. Occurrence and origin of marialitic scapolite in the Humboldtt Lopolith, N.W. Nevada. Contributions to Mineralogy Petrology 1982, 81, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, L.V.; Rosa-Costa, L.R.; Silva, C.G.; Ricci, P.F.; Barbosa, J.O.; Klein, E.L.; Lopes, E.S.; Macambira, E.B.; Chaves, C.L.; Carvalho, J.M.; Oliveira, J.G.; Anjos, G.C.; Silva, H.R. (2008) Geologia e Recursos Minerais do Estado do Pará: Sistema de Informações Geográficas–SIG: Texto Explicativo dos Mapas Geológico e Tectônico e de Recursos Minerais do Estado do Pará. CPRM, Belém.

- Vollgger, S.A.; Cruden, A.R.; Ailleres, L.; Cowan, E.J. Regional dome evolution and its control on ore-grade distribution: Insights from 3D implicit modelling of the Navachab gold deposit, Namibia. Ore Geology Reviews 2015, 69, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volp, K.M. (2005) The Estrela copper deposit, Carajás, Brazil. Geology and implications of a Proterozoic copper stockwork. In: Mao, J.; Bierlein, F.P. (eds.) Mineral Deposit Research: Meeting the Global Challenge. Springer, Berlin, pp. 1085–1088.

- Williams, P.J.; Barton, M.D.; Johnson, D.A.; Fontboté, L.; de Haller, A.; Mark, G.; Oliver, N.H.S.; Marschik, R. Iron oxide copper-gold deposits: Geology, space-time distributions and possible modes of origin. Economic Geology 2005, 100, 371–405. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, C.J. (1994) Geology and base-metal mineralization associated with Archean iron-formation in the Pojuca Corpo Quatro Deposit, Carajás, Brazil. University of Southampton.

- Wirth, K.R.; Gibbs, A.K.; Olszewski, W.J. Jr. U-Pb ages of zircons from the Grão Pará Group and Serra dos Carajás granite, Pará, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Geociências 1986, 16, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, R.P.; Monteiro, L.V.S.; Souza Filho, C.R.; Torresi, I.; Carvalho, E.R.; Dreher, A.M.; Wiedenbeck, M.; Trumbull, R.B.; Pestilho, A.L.S.; Moreto, C.P.N. (2010) The iron oxide copper‒gold deposits of the Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil: an updated and critical review. In: Porter, T.M. (ed.) Hydrothermal Iron Oxide Copper-Gold & Related Deposits: A Global Perspective. Australian Miner. Fund, Adelaide, 3, 285–306.

- Xavier, R.P.; Monteiro, L.V.S.; Moreto, C.P.N.; Pestilho, A.L.S.; Melo, G.H.C.; Silva, M.A.D.; Aires, B.; Ribeiro, C.; Silva, F.H.F. (2012) The Iron Oxide Copper-Gold Systems of the Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil. In: Geology and Genesis of Major Copper Deposits and Districts of the World: A Tribute to Richard Sillitoe. Special publication of the Society of Economic Geologists.

- Xavier, R.P.; Moreto, C.P.N.; Melo, G.H.; Toledo, P.; Hunger, R.; Delinardo da Silva, M.A.; Faustinoni, J.; Lopes, A.; Monteiro, L.V.S.; Previato, M.; Jesus, S.S. (2017) Geology and metallogeny of Neoarchean and Paleoproterozoic copper systems of the Carajás Domain, Amazonian Craton, Brazil. In: Proceedings of the 14th Biennial SGA Meeting of the Society for Geology Applied to Mineral Deposits, Quebec.

- Xavier, R.P.; Monteiro, L.V.S.; Moreto, C.P.N.; Pestilho, A.L.S.; Melo, G.H.C.; Silva, M.A.D.; Aires, B.; Ribeiro, C.; Silva, F.H.F. 2012. The The Iron Oxide Copper-Gold Systems of the Carajás Mineral Province, Brazil. In: Geology and Genesis of Major Copper Deposits and Districts of the World: A Tribute to Richard Sillitoe. Special publication of the Society of Economic Geologists.

- Xavier, R.P.; Moreto, C.P.N.; Melo, G.H.; Toledo, P.; Hunger, R.; Delinardo da Silva, M.A.; Faustinoni, J.; Lopes, A.; Monteiro, L.V.S.; Previato, M.; Jesus, S.S. 2017. Geology and metallogeny of Neoarchean and Paleoproterozoic copper systems of the Carajás Domain, Amazonian Craton, Brazil. In: Proceedings of the 14th Biennial SGA Meeting of the Society for Geology Applied to Mineral Deposits, Quebec, 899-902.

- Zucchetti, M. 2007. Rochas máficas do Grupo Grão Pará e sua relação com a mineralização de ferro dos depósitos N4 e N5, Carajás, PA. Tese de Doutorado, UFMG, 165.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).