Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

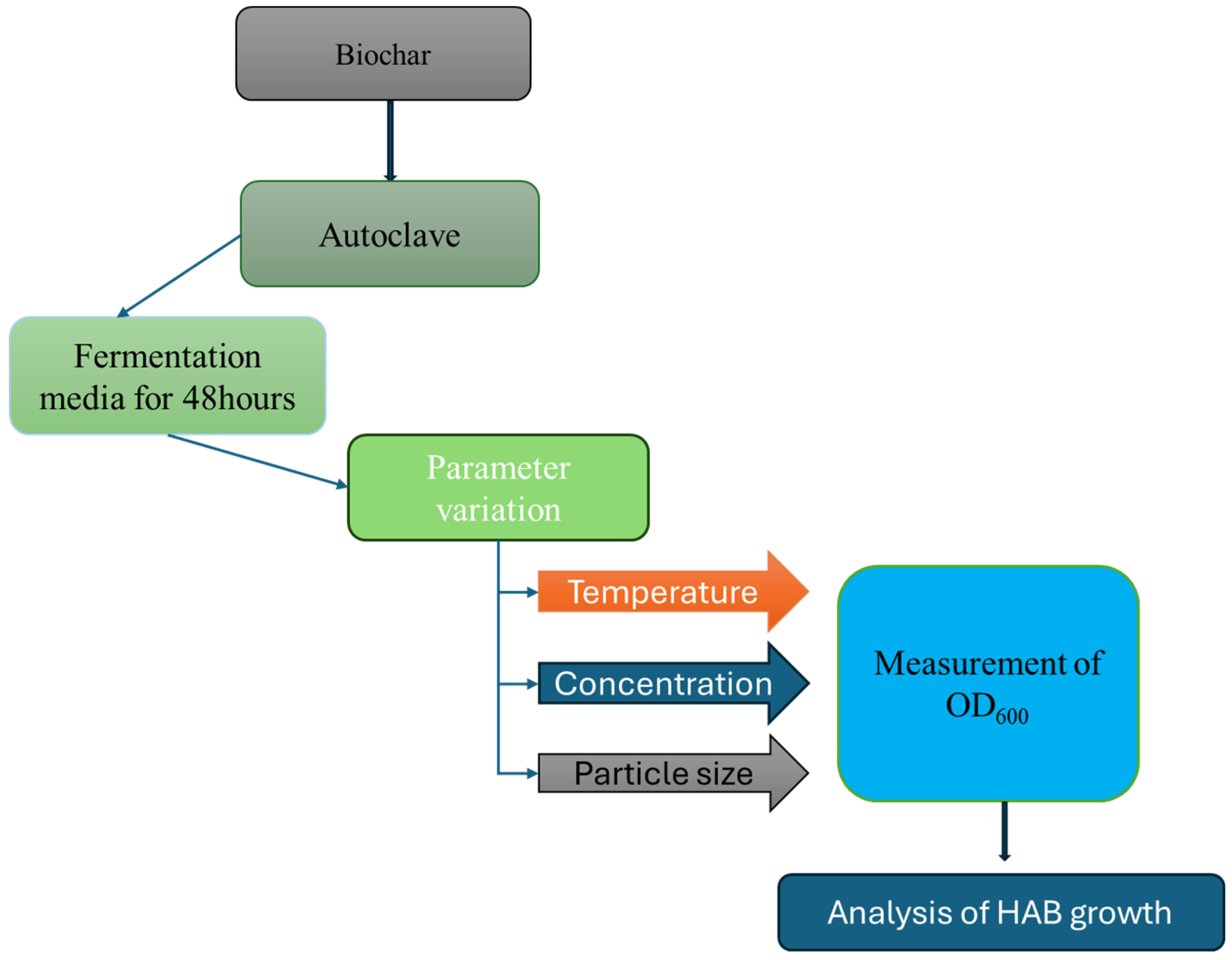

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Media and Fermentation Conditions

2.2. Experimental Set Up

2.2. Biochar Concentration Experiments

2.3. Temperature Experiments

2.4. Biochar Particle Size Experiments

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscope Analysis (SEM)

3. Results

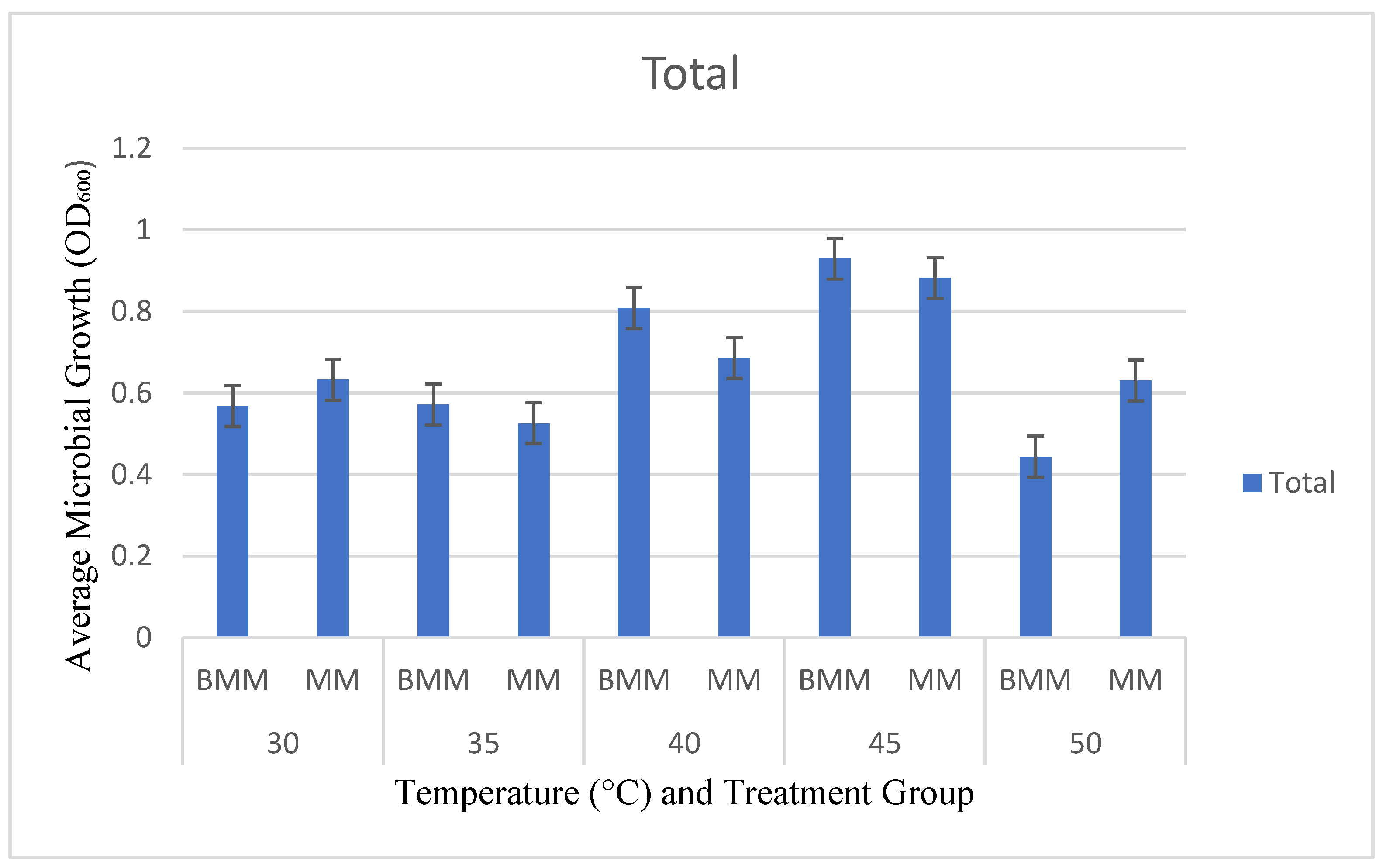

3.1. Temperature Effect

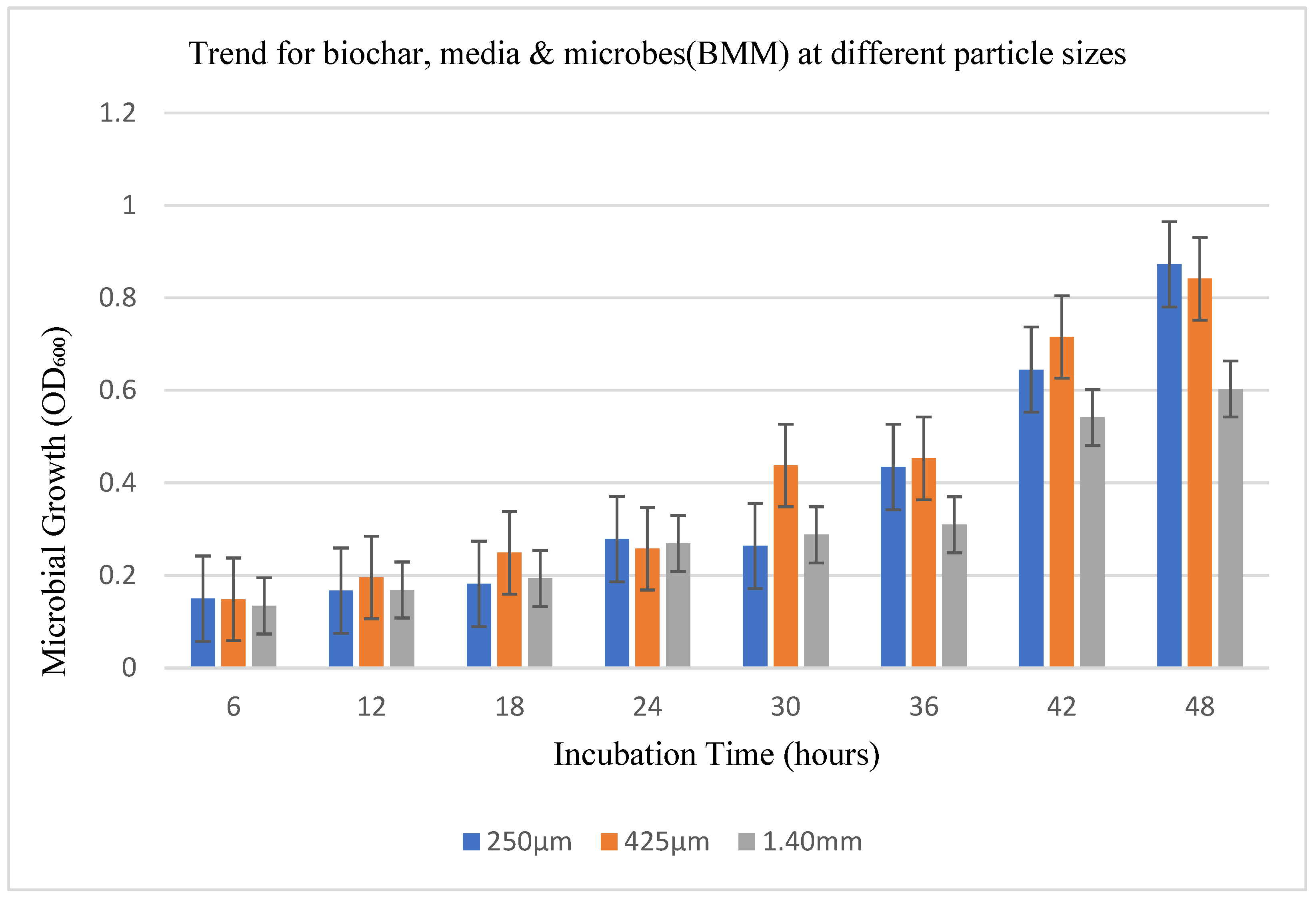

3.2. Particle Sizes

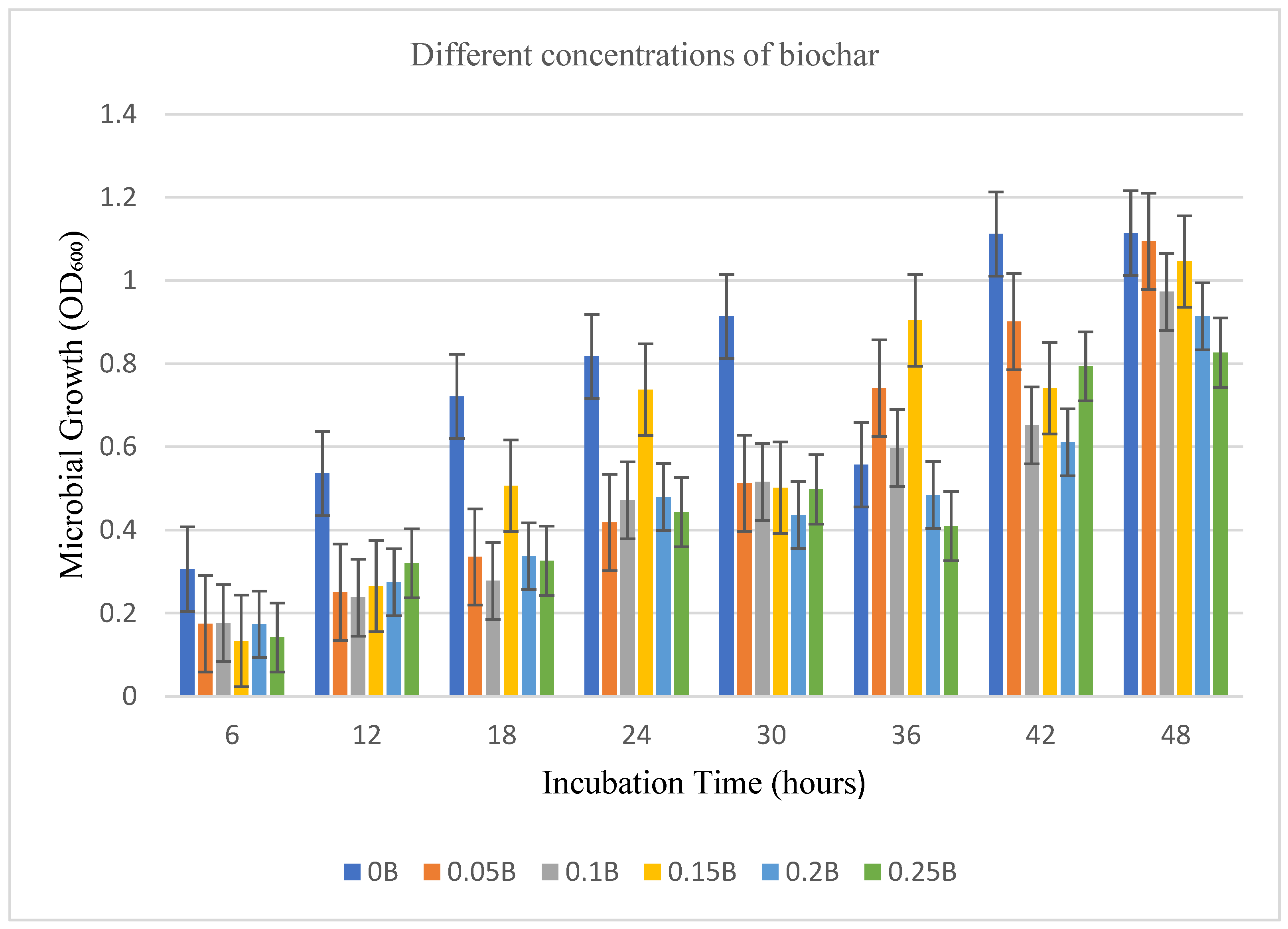

3.3. Biochar Concentration

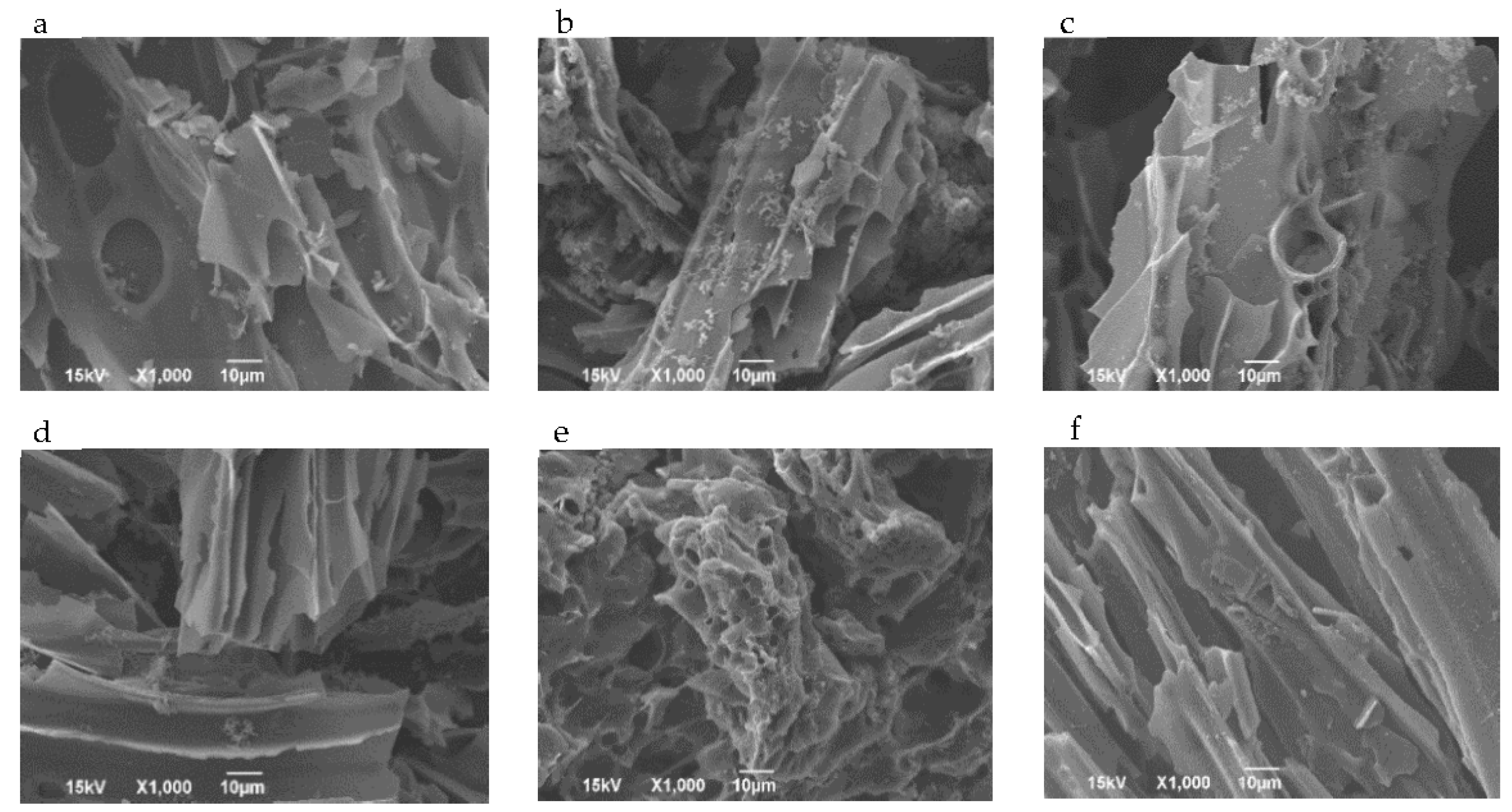

3.3. Biochar, Microbe and Composite Morphology

4. Conclusions

References

- Siddiqui SA, Erol Z, Rugji J, Taşçı F, Kahraman HA, Toppi V, et al. An overview of fermentation in the food industry - looking back from a new perspective. Bioresour Bioprocess 2023;10:85. [CrossRef]

- Kotarska K, Dziemianowicz W, Świerczyńska A. The Effect of Detoxification of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Enhanced Methane Production. Energies 2021;14:5650. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Wang Y, Shang N, Li P. Microbial Fermentation Processes of Lactic Acid: Challenges, Solutions, and Future Prospects. Foods 2023;12:2311. [CrossRef]

- Berillo D, Malika T, Baimakhanova BB, Sadanov AK, Berezin VE, Trenozhnikova LP, et al. An Overview of Microorganisms Immobilized in a Gel Structure for the Production of Precursors, Antibiotics, and Valuable Products. Gels 2024;10:646. [CrossRef]

- Najim AA, Radeef AY, al-Doori I, Jabbar ZH. Immobilization: the promising technique to protect and increase the efficiency of microorganisms to remove contaminants. J Chem Technol Biotechnol 2024;99:1707–33. [CrossRef]

- Manikandan SK, Pallavi P, Shetty K, Bhattacharjee D, Giannakoudakis DA, Katsoyiannis IA, et al. Effective Usage of Biochar and Microorganisms for the Removal of Heavy Metal Ions and Pesticides. Molecules 2023;28:719. [CrossRef]

- Benchaar C, Hassanat F, Côrtes C. Assessment of the Effects of Commercial or Locally Engineered Biochars Produced from Different Biomass Sources and Differing in Their Physical and Chemical Properties on Rumen Fermentation and Methane Production In Vitro. Animals 2023;13:3280. [CrossRef]

- Huff MD, Marshall S, Saeed HA, Lee JW. Surface oxygenation of biochar through ozonization for dramatically enhancing cation exchange capacity. Bioresour Bioprocess 2018;5:18. [CrossRef]

- Wijitkosum S, Jiwnok P. Elemental Composition of Biochar Obtained from Agricultural Waste for Soil Amendment and Carbon Sequestration. Appl Sci 2019;9:3980. [CrossRef]

- Kayoumu M, Wang H, Duan G. Interactions between microbial extracellular polymeric substances and biochar, and their potential applications: a review. Biochar 2025;7:62. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Z, Li Q, Peng F, Yu J. Biochar Loaded with a Bacterial Strain N33 Facilitates Pecan Seedling Growth and Shapes Rhizosphere Microbial Community. Plants 2024;13:1226. [CrossRef]

- Lu J-H, Chen C, Huang C, Lee D-J. Glucose fermentation with biochar-amended consortium: microbial consortium shift. Bioengineered 2020;11:272–80. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Dai L, Wu B, Qi B, Huang T, Hu G, et al. Biochar-mediated enhanced ethanol fermentation (BMEEF) in Zymomonas mobilis under furfural and acetic acid stress. Biotechnol Biofuels 2020;13:28. [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi A, Bello I, Mukaila T, Sarker N, Hammed A. Trends in Biological Ammonia Production 2023. [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly GC, Huo Y, Meale SJ, Chaves AV. Dose response of biochar and wood vinegar on in vitro batch culture ruminal fermentation using contrasting feed substrates. Transl Anim Sci 2021;5:txab107. [CrossRef]

- Burman E, Bengtsson-Palme J. Microbial Community Interactions Are Sensitive to Small Changes in Temperature. Front Microbiol 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Fu Z, Chen Y, Lu Y, Wang Y, Chen J, Zhao Y, et al. KMnO4 modified biochar derived from swine manure for tetracycline removal. Water Pract Technol 2022;17:2422–34. [CrossRef]

- Chang X, Wang S, Luo C, Zhang Z, Duan J, Zhu X, et al. Responses of soil microbial respiration to thermal stress in alpine steppe on the Tibetan plateau. Eur J Soil Sci 2012;63:325–31. [CrossRef]

- Ye J-S, Bradford MA, Maestre FT, Li F-M, García-Palacios P. Compensatory Thermal Adaptation of Soil Microbial Respiration Rates in Global Croplands. Glob Biogeochem Cycles 2020;34:e2019GB006507. [CrossRef]

- Shan S, Coleman MD. Biochar influences nitrogen availability in Andisols of north Idaho forests. SN Appl Sci 2020;2:362. [CrossRef]

- Prévoteau A, Ronsse F, Cid I, Boeckx P, Rabaey K. The electron donating capacity of biochar is dramatically underestimated. Sci Rep 2016;6:32870. [CrossRef]

- Bednik M, Medyńska-Juraszek A, Ćwieląg-Piasecka I, Dudek M. Enzyme Activity and Dissolved Organic Carbon Content in Soils Amended with Different Types of Biochar and Exogenous Organic Matter. Sustainability 2023;15:15396. [CrossRef]

- Zheng Q, Hu Y, Zhang S, Noll L, Böckle T, Richter A, et al. Growth explains microbial carbon use efficiency across soils differing in land use and geology. Soil Biol Biochem 2019;128:45–55. [CrossRef]

- Isaksen GV, Åqvist J, Brandsdal BO. Enzyme surface rigidity tunes the temperature dependence of catalytic rates. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2016;113:7822–7. [CrossRef]

- Lv Y, Tang C, Liu X, Zhang M, Chen B, Hu X, et al. Optimization of Environmental Conditions for Microbial Stabilization of Uranium Tailings, and the Microbial Community Response. Front Microbiol 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Ding J, Zhen F, Kong X, Hu Y, Zhang Y, Gong L. Effect of Biochar in Modulating Anaerobic Digestion Performance and Microbial Structure Community of Different Inoculum Sources. Fermentation 2024;10:151. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad W, Nepal J, Zou Z, Munsif F, Khan A, Ahmad I, et al. Biochar particle size coupled with biofertilizer enhances soil carbon-nitrogen microbial pools and CO2 sequestration in lentil. Front Environ Sci 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Gu Y, Zhang H, Liang X, Fu R, Li M, Chen C. Effect of different biochar particle sizes together with bio-organic fertilizer on rhizosphere soil microecological environment on saline–alkali land. Front Environ Sci 2022;10. [CrossRef]

- Tang E, Liao W, Thomas SC. Optimizing Biochar Particle Size for Plant Growth and Mitigation of Soil Salinization. Agronomy 2023;13:1394. [CrossRef]

- Tahery S, Parra MC, Munroe P, Mitchell DRG, Meale SJ, Joseph S. Developing an activated biochar-mineral supplement for reducing methane formation in anaerobic fermentation. Biochar 2025;7:26. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Lim EY, Loh K-C, Ok YS, Lee JTE, Shen Y, et al. Biochar enhanced thermophilic anaerobic digestion of food waste: Focusing on biochar particle size, microbial community analysis and pilot-scale application. Energy Convers Manag 2020;209:112654. [CrossRef]

- Wu S-L, Wei W, Xu Q, Huang X, Sun J, Dai X, et al. Revealing the Mechanism of Biochar Enhancing the Production of Medium Chain Fatty Acids from Waste Activated Sludge Alkaline Fermentation Liquor. ACS EST Water 2021;1:1014–24. [CrossRef]

- Heitkamp K, Latorre-Pérez A, Nefigmann S, Gimeno-Valero H, Vilanova C, Jahmad E, et al. Monitoring of seven industrial anaerobic digesters supplied with biochar. Biotechnol Biofuels 2021;14:185. [CrossRef]

- Tang E, Liao W, Thomas SC. Optimizing Biochar Particle Size for Plant Growth and Mitigation of Soil Salinization. Agronomy 2023;13:1394. [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhamied AS, El-Shiekha AM. Effect of Biochar Source, Particle Size and Application Rates on Soil Properties and Maize Yield (Zea mays L.) under Sandy Soil Conditions. J Soil Sci Agric Eng 2021;12:71–80. [CrossRef]

- Waqas M, Nizami AS, Aburiazaiza AS, Barakat MA, Ismail IMI, Rashid MI. Optimization of food waste compost with the use of biochar. J Environ Manage 2018;216:70–81. [CrossRef]

- Schommer VA, Nazari MT, Melara F, Braun JCA, Rempel A, dos Santos LF, et al. Techniques and mechanisms of bacteria immobilization on biochar for further environmental and agricultural applications. Microbiol Res 2024;278:127534. [CrossRef]

- Krichen E, Harmand J, Torrijos M, Godon JJ, Bernet N, Rapaport A. High biomass density promotes density-dependent microbial growth rate. Biochem Eng J 2018;130:66–75. [CrossRef]

- Frenkel O, Jaiswal AK, Elad Y, Lew B, Kammann C, Graber ER. The effect of biochar on plant diseases: what should we learn while designing biochar substrates? J Environ Eng Landsc Manag 2017;25:105–13. [CrossRef]

- Li K, Yang B, Wang H, Xu X, Gao Y, Zhu Y. Dual effects of biochar and hyperaccumulator Solanum nigrum L. on the remediation of Cd-contaminated soil. PeerJ 2019;7:e6631. [CrossRef]

- Hill RA, Hunt J, Sanders E, Tran M, Burk GA, Mlsna TE, et al. Effect of Biochar on Microbial Growth: A Metabolomics and Bacteriological Investigation in E. coli. Environ Sci Technol 2019;53:2635–46. [CrossRef]

- Zhang B, Li R, Zheng Y, Chen S, Su Y, Zhou W, et al. Biochar Composite with Enhanced Performance Prepared Through Microbial Modification for Water Pollutant Removal. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:11732. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).