1. Introduction

In the context of modern education and social development, sport represents a vital mechanism for fostering social inclusion, especially among children and adolescents exposed to marginalization, isolation, or disadvantage. Among various sports, football is uniquely positioned as a global and culturally embedded practice that promotes collective engagement, identity formation, and inter-personal bonds. As such, it serves not only as a vehicle for athletic development but also as a space for cultivating inclusive, equitable environments.

In this paper, we explore the role of small-sided football games (SSGs) as both a pedagogical tool for enhancing technical and tactical player development and a social mechanism capable of pro-moting inclusion. By focusing on youth players aged 13–14 years, we examine how SSGs—through their structural and relational dynamics—can create conditions that empower young people, foster participation, and strengthen team cohesion.

Social Inclusion Through Sport

Social inclusion is a multidimensional construct that encompasses equitable access to resources, active participation in community life, and recognition of individual and group identities. Inclusion involves both removing structural barriers and building social connections that enable individuals to feel part of a collective whole. The World Bank (2013) further emphasizes inclusion as improving the ability, opportunity, and dignity of people to take part in society.

In the context of sport, and football in particular, social inclusion refers not merely to physical presence on a team, but to meaningful participation, reciprocal recognition, and development of social capital (FIFA). Football can serve as an inclusive space where shared goals, communication, and structured interaction allow for mutual trust and solidarity to emerge. These processes are especially potent in youth contexts, where identity and interpersonal skills are actively being shaped.

From a socio-cognitive lens, Social Identity Theory suggests that participation in team sports can enhance group affiliation and reduce intergroup bias. Communities of Practice theory positions football teams as informal learning environments where norms, skills, and values are transmitted through joint engagement.

Within this framework, small-sided games (SSGs) play a specific role: by reducing the number of players and the playing area, they increase individual engagement and interaction. This design minimizes hierarchical barriers, enhances communication, and enables all players—regardless of skill or background—to contribute visibly and frequently. These structural features of SSGs support both technical development and inclusive team dynamics.

The education of the young generation encompasses various aspects of human development, including individual, artistic, moral, civic, psycho-behavioral, and biomotor aspects. Inclusive aspects play a crucial role in this process. Children should be trained to use their free time effectively, fostering healthy life habits and promoting socialization, integration, and self-affirmation. Football, a popular sport, is associated with human virtues such as intelligence, honesty, loyalty, pleasure, strength, and mastery. Top performers serve as role models for children from various social areas. Football offers social security and personal affirmation, making it an effective tool for social inclusion [

1,

2].

FIFA and UNICEF collaborate to improve the quality of life for children and teens by using football as a technique for social inclusion. The Homeless World Cup (HWC) is a successful example of this, with the tournament transforming 1.2 million lives since 2003. Small-sided games (SSGs) provide superior technical/tactical drills, allowing players to make quick and efficient decisions in various situations. These games are designed to train players to be physically, technically, tactically, psychologically, and theoretically capable of continuing their activity in senior teams [

3].

Using games that partially simulate football is a valuable strategy for improving player performance. Small-sided games involve fewer performers, a compact playing field, and adjusted intervention rules, but they can recreate partial episodes in some 11v11 formats [

4,

5,

6,

7].

Football has evolved from normal pitches to smaller pitches, necessitating constant updates on rules and training methods. This requires coaches to adapt and implement new guiding ideas, such as small-sided games (SSGs), based on players' age and practice experience. SSGs are crucial for skill growth in team activities, especially for younger players. This research aims to highlight the impact of SSGs on improving the offensive phase in football, particularly for 13-14-year-old teams. By de-signing SSGs based on the unique characteristics of this age range, the study aims to improve the team's offensive level and attack preparation.

Sport plays a crucial role in combating social exclusion, discrimination, poverty, and unfairness. Football, in particular, contributes to the development of fundamental physical and mental qualities such as attention, willpower, perseverance, self-control, endurance, strength, and speed. Inclusive school sports aim to adapt to individual and collective characteristics, breaking down social barriers and promoting diversity. Football is accessible and contributes to the integration of personal efforts and actions in a team's collective effort, enhancing health and motivation. Street football should be adapted to achieve social goals aimed at individual and collective transformation [

1,

10,

11,

12].

Stair football should be emphasized for its potential to blend physical, technical, and tactical training in environments similar to actual play. Research findings support the application of Street Soccer Groups (SSGs) as a systematic resource for teaching children the game of football. A recent study found that the average amount of goals per game is highly correlated with the physical parameters of eight different football variants, and changes made to the fundamental elements of football can impact its scoring rate. For example, a 20-meter shorter football field could increase the average goal scored per match by 3.6. [

13,

14]

Research on agility requirements in professional Australian football (AF) compared four small-sided games with 14 male premier AFL players. The study found that while there was a significant 2D player load, there was little gain in overall agility movements due to reduced surface per player. However, there was an increase in diversity but a moderate overall number of dexterity movements due to fewer players. The adoption of a 2-handed-tag rule caused a somewhat insignificant decline in agility events compared to conventional AFL tackling regulations. Coaches should carefully assess how SSG is designed to maximize each player's potential for developing agility. The study also found that pitch size changes and goalie participation had different outcomes in terms of overall distance run, explosive distance, accelerations or decelerations, and maximal sprint. Mid-fielders had the highest network significance scores compared to defenders and forwards. The study suggests that coaches can estimate the SSG load and modify the field's dimensions to accommodate players [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Small-sided games (SSGs) are a popular method for football training, as they provide a low training load and allow for a smaller playing area and number of athletes. The size of the pitch is crucial for female football players, as it affects both internal and external strain. Small-sided games are preferred over wide-sided games, as they allow children under 12 to develop a variety of skills and creativity [

20,

21].

However, forcing children to play in larger teams and games can reduce engagement, success, enjoyment, and learning opportunities. Larger-sided games often focus on positions and complex adult tactics, rather than developing skills, communication, and enthusiasm. Training on larger-sided playing areas may have a high failure rate for young football players [

22].

SSGs are modified versions of known games used during training to prepare players for specific technical, tactical, and physical topics. Regular use of SSGs may result in changes in the technical ability and strategic behaviors of child and junior football players. Further research should analyze the tactical and technical aspects of young players' responses to different SSG formats, considering their age and training experience [

23,

24].

A study examined the impact of small-sided games on juvenile football players of varying pitch dimensions during 7-a-side SSG forms. Two teams of seven players each were formed from 14 male soccer athletes in each age category. The study recommended coaches use SSGs to encourage specific-adaptive behaviors and improve individual performance. The development of football for children and juniors has increased dynamically at both elite and grassroots levels, with new approaches focusing on personalized games, strategic awareness, technical/tactical learning, and alternative educational progression [

17,

25].

2. Study Purpose

Guided by the theoretical foundations above, this study investigates the dual function of SSGs in football: (1) their impact on technical and tactical performance indicators in 13–14-year-old players, and (2) their potential to foster social inclusion within a youth training environment. While the primary analysis is quantitative and performance-based, the conceptual emphasis is on how the design and implementation of SSGs align with inclusive values and learning principles that are increasingly critical in contemporary sport pedagogy.

3. Materials and Methods

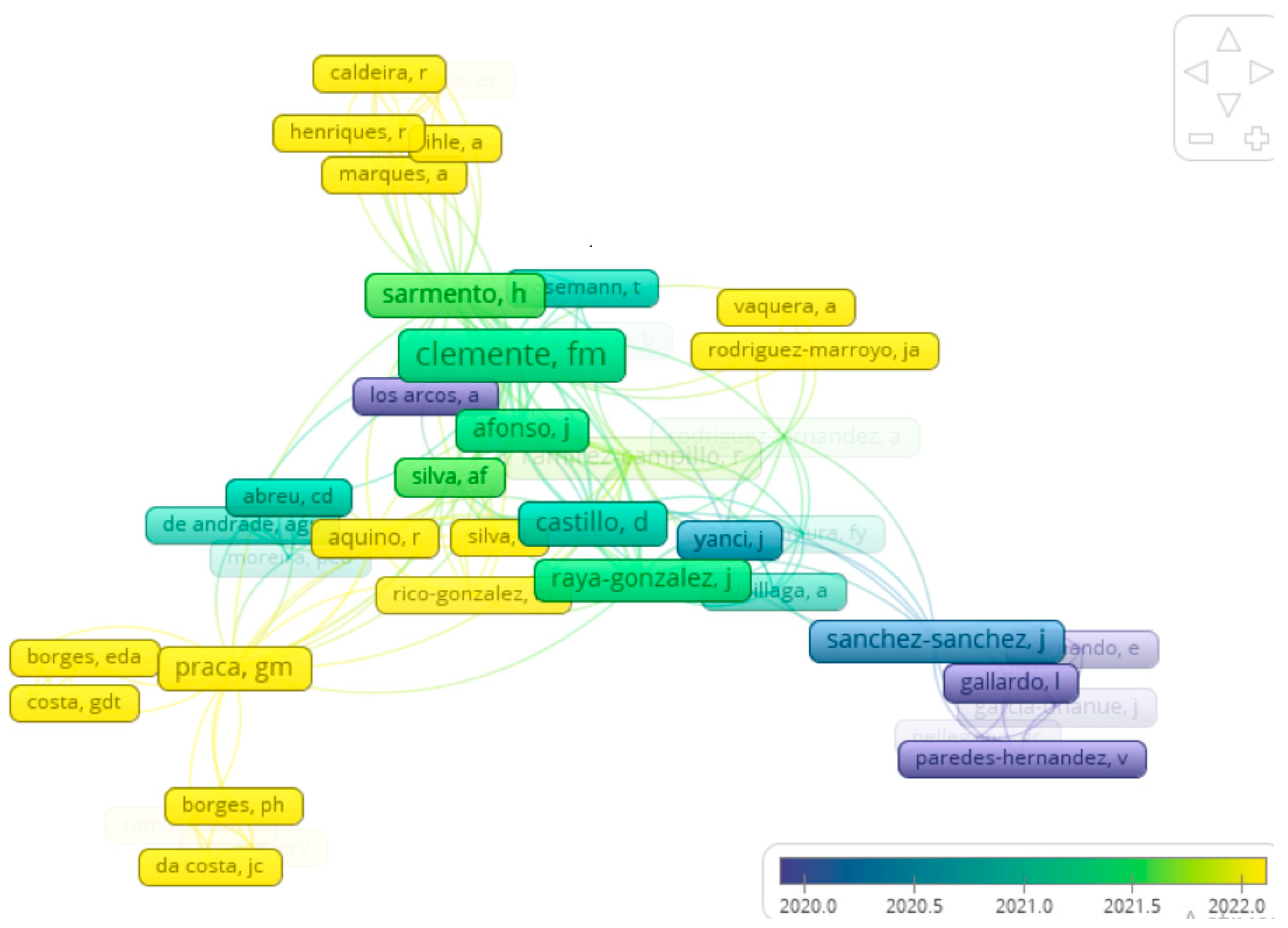

The current analysis is based on a Web of Science (WoS) scan of the scientific literature on football, more specifically, on small-sided games across all WoS sectors and categories, with releases from 2020 to 2023 of both research and review publications. The search yielded 1274 papers, of which 41 were selected based on relevant criteria, namely the results and performance obtained. Studies that showed equivalent results but did not have the full text available and were mainly theoretical or irrelevant to the topic were excluded. The author data in

Figure 1 are classified by key topic and year, with a connection between them.

The effects of SSG treatments on the tactical actions and technical performance of young and adolescent team sports players were examined by a group of writers [

26]. 803 titles were initially found in the database search. Of these, six publications were eligible for in-depth examination and meta-analysis. No tactical behavior outcomes were reported in any of the studies reviewed. Compared to controls, the results demonstrated that SSGs had a minor impact on technical performance. After 17 SSG training sessions, a subgroup examination of the training factor highlighted modest and minor improvements in technical execution. This comprehensive study and meta-analysis found that using SSG programs for training to enhance technical performance in young and adolescent performers had a substantial favorable effect. Regardless of the number of training sessions applied, the benefits were similar. However, further research is needed to include tactical actions as one of the effects of limiting the impact of SSG training [

26].

The objective of the present study is to find out if these SSGs (drills) can have a positive kick on football players in terms of their ability to complete technical/tactical actions at the opponent’s goal by scoring or staying in possession, or by increasing their team’s percentage of staying in attack and decreasing their team’s percentage of passing in defense. Thus, we aim to analyze the impact of SSG programs on technical/tactical performance among adolescents and young people participating in team sports (with a spotlight on the game of football) in order to improve the performance of 13-14-year-old athletes at a competitive level.

For the Concordia Chiajna children's team, the coach used ameliorative methods and training based on small-sided games (SSGs), as shown above. The results were quantified through several technical/tactical indicators during the official games played in both the first half and the return stage of the 2022-2023 championship.

4. Results

4.1. Testing Technical/Tactical Offensive Actions

To find out if there is a statistically meaningful variation among the test values achieved in the first half and the return stage of the championship for technical/tactical offensive actions, we apply the t-test for Paired Samples (Paired-Two-Sample for Means).

Our analysis reveals that t-Stat test values in the mode for the variables CROSS (t= 2.13; p= 0.007), CROSSPOSS (t= 1.75; p= 0.05), RELEASE(t= 1.75; p= 0.03), THROWOWN (t= 1.75; p= 0.04), and THROWOPP(t= 2.13; p= 0.01) are greater than the minimum accepted two-tailed t-Critical value, with a very high level of significance (p-value is lower than 0.05) and a 95% confidence level. This difference is statistically significant. We may extend our conclusion to the whole statistical population using the statistical inference t-test, because t-Stat > t-Critical and p < 0.05 (Table 1). In other words, when repeating the test under similar conditions, similar results are obtained. For sports, this means that SSG training positively influenced these technical/tactical offensive components (

Table A1,

Appendix A).

The OTMIN average (691) is lower than the ORMIN average (704), so, in the return stage, the number of minutes played increased, meaning that the higher actual playing time (moments when the ball was in play) offered players from both teams the opportunity to show better technical/tactical expression skills in the offensive and defensive phases (of course, in different proportions) (

Table A1,

Appendix A).

The OTCROSS average (4.63) is lower than the ORCROSS average (6.88), so, in the return stage, the number of crosses increased by 2.25 units compared to the first half of the season, meaning that the team's offensive ability increased, especially on the sidelines of the field (

Table A1,

Appendix A).

The OTCROSSPOSS average (2.81) is lower than the ORCROSSPOSS (3.69) average, so, in the return stage, the number of crosses with ball possession increased by 0.87units compared to the first half of the season, meaning that more goal-scoring opportunities were created (

Table A1,

Appendix A).

The OTVERTRELEASE average (5.75) is higher than the ORVERTRELEASE average (4.31), so, in the return stage, the number of vertical releases decreased by 1.43 units compared to the first half of the season, meaning that the team's potential to reach the opponent's goal faster was lower, but the tactical concern to build the offensive phase increased (

Table A1,

Appendix A).

The OTDIAGRELEASE average (4.19) is higher than the ORDIAGRELEASE average (3.88), so, in the return stage, the number of diagonal releases in the offensive phase decreased (following the previous indicator) by 0.35units (so, very little), meaning that in-game relationships between mid-fielders and forwards were based on medium- and short-range passes, which are characteristic of more elaborate playing relationships (

Table A1,

Appendix A).

The OTCORNER average (2.5) is lower than the ORCORNER average (3.69), so, in the return stage, this fixed phase increased by 1.18 units, meaning that the investigated team players stayed in the attack longer, extending the offensive phase, with a greater potential to score goals (

Table A1,

Appendix A).

The OTPENALTY average (1.19) is lower than the ORPENALTY average (1.31), so, in the return stage, the chances of scoring from penalty kicks increased by 0.12 units, meaning that, despite the small number of players, the team was dangerous in attack, therefore the opponents had no other options but to use this last solution (

Table A1,

Appendix A).

The OTTHROWOWN average (3.94) is higher than the ORTHROWOWN average (2.69), so, in the return stage, the number of throw-ins from the own half of the studied team decreased by 1.25 units compared to the first half of the season, meaning that the opposing team was less present in attack, therefore they initiated fewer offensive actions (

Table A1,

Appendix A).

The OTTHROWOPP average (2.5) is lower than the ORTHROWOPP average (4.38), so, in the return stage, the number of throw-ins from the opponent's half increased by 1.87 units compared to the first half of the season, meaning that the studied team was more present in attack, therefore their offensive actions were more frequent, and the opponent had to send the ball out of play more times (

Table A1,

Appendix A).

T-Stat test values in the mode for the variables min (t= 2.13; p= 0.75), DIAGRELEASE (t= 2.13; p= 0.66), CORNER (t= 2.13; p= 0.16), and PENALTY (t= 2.13; p= 0.54) are less than the minimum accepted two-tailed t-Critical value, with a very low level of significance (p-value> 0.05) and a 95% confidence level. This difference is NOT statistically significant. We may NOT extend our conclusion to the whole statistical population using the statistical inference t-test because t-Stat < t-Critical and p > 0.05 (

Table A1,

Appendix A). In other words, when repeating the test under similar conditions, we are not sure that we get similar results. Regarding the game of football, we can state that SSG training did NOT positively influence these technical/tactical offensive components for our team, but they are possible to be influenced by other individuals through actions developed in the context of the time and space constraints that characterize modern football.

4.2. Testing Technical/Tactical Defensive Actions

To find out if there is a statistically meaningful variation among the test values achieved in the first half and the return stage of the championship for technical/tactical defensive actions, we apply the t-Test for Paired Samples (Paired Two-Sample for Means).

Our analysis highlights that t-Stat test values in the mode for the variables RECOVGOAL (t= 2.13; p= 0.012), RECOVOWN (t = 2.13; p= 0.001), RECOVOPP (t=2.13; p= 0.006), and REJECT-FOOT (t= 1.75; p= 0.001)are greater than the minimum accepted two-tailed t-Critical value, with a very high level of significance (p-value < 0.05) and a 95% confidence level. This difference is statistically significant. We may extend our conclusion to the whole statistical population using the statistical inference t-test because t-Stat > t-Critical and p< 0.05 (Table 2). In other words, when repeating the test under similar conditions, similar results are obtained. For sports, this means that SSG training positively influenced these technical/tactical defensive components (

Table A2,

Appendix A).

The DTRECOVGOAL average (9.31) is lower than the DRRECOVGOAL average (10.93), so, in the return stage, the number of ball recoveries in the own goal area increased by 1.625 units compared to the first half of the season, meaning that, in the defensive phase, in the context of defending their goal and removing the danger, the studied players but mainly the fullbacks had a better ability to get possession of the ball(

Table A2,

Appendix A).

The DTRECOVOWN average (6.56) is lower than the DRRECOVOWN average (9.62), so, in the return stage, the number of ball recoveries in the own half of the field increased by 3.06 units com-pared to the first half of the season, meaning that the use of individual and collective actions had an increased efficiency (

Table A2,

Appendix A).

The DTRECOVOPP average (2.75) is lower than the DRRECOVOPP average (4), so, in the return stage, the number of ball recoveries in the opposing half increased by 1.25 units compared to the first half of the season, meaning that the team used a more aggressive interception press (

Table A2,

Appendix A).

The DTREJECTFOOT average (4.75) is lower than the DTREJECTFOOT average (6.93), so, in the return stage, the number of ball rejections with the foot from fixed phases increased by 2.18 units compared to the first half of the season, meaning that the possibilities of anticipating the trajectory of the ball and the ability to reach the ball first (to get in front of the opponent)had a higher degree of success(

Table A2,

Appendix A).

Table 2 shows that t-Stat test values in the mode for the variables MIN (t=2.13; p= 0.75), RE-COVPENALTY (t=2.13; p= 0.62), REJECTHEAD (t=2.13; p= 0.88), and PENALTY (t=2.13; p= 0.18) are less than the minimum accepted two-tailed t-Critical value, with a very low level of significance (p-value > 0.05) and a 95% confidence level. This difference is NOT statistically significant. We may NOT extend our conclusion to the whole statistical population using the statistical inference t-test because t-Stat < t-Critical and p > 0.05 (

Table A2,

Appendix A). In other words, when repeating the test under similar conditions, we are not sure that we get similar results. Regarding the game of football, we can state that SSG training did NOT positively influence these technical/tactical defensive com-ponents for our team, but they are possible to be influenced by other individuals.

The DTMIN average (691.25) is lower than the DRMIN average (704.37), so, in the return stage, the number of minutes played increased by 13.125 compared to the first half of the season, which means a better ability to keep the ball in play and develop tactical actions related to the positive principles of the game (

Table A2,

Appendix A).

The DTRECOVPENALTY average (10.43) is lower than the DRRECOVPENALTY average (10.68), so, in the return stage, the number of ball recoveries in the own penalty area increased by 0.25 units compared to the first half of the season, meaning that the team dominated slightly better (even if very little) an area of the field with high potential for opponents to finish (

Table A2,

Appendix A).

The DTREJECTHEA Daverage (4.31) is higher than the DRREJECTHEAD average (4.25), so, in the return stage, the number of ball rejections with the head from fixed phases decreased by 0.0625units compared to the first half of the season, which means, in the context of the results achieved, that the opponents made fewer crosses in the fixed moments, or their tactics had a different offensive content (

Table A2,

Appendix A).

The DTPENALTY average (0.81) is higher than the DRPENALTY average (0.43), so, in the return stage, the number of penalty kicks decreased by 0.375 units compared to the first half of the season, which could mean, on the one hand, lower aggression from the opponents, and on the other hand, a greater ability of the investigated team to complete offensive actions (

Table A2,

Appendix A).

4.3. Testing the Number of Scored Goals

To find out if there is a statistically meaningful variation among the test values achieved in the first half and the return stage of the championship for the number of scored goals, we apply the t-Test for Paired Samples (Paired Two-Sample for Means).

Our analysis shows that t-Stat test values in the mode for the variables SACOLLECTIVE (t= 2.13; p= 0.019), SAINDIV (t= 2.13; p= 0.006), SFDIRECT (t=2.13; p= 0.001), SFINDIRECT (t=2.13; p= 0.006), SCORNER (t=2.13; p= 0.000), and STOTAL (t=2.13; p= 0.0002) are greater than the mini-mum accepted two-tailed t-Critical value, with a very high level of significance (p-value < 0.05) and a 95% confidence level. This difference is statistically significant. We may extend our conclusion to the whole statistical population using the statistical inference t-test because t-Stat > t-Critical and p < 0.05 (Table 3). In other words, when repeating the test under similar conditions, similar results are obtained. For sports, this means that SSG training positively influenced these technical/tactical offensive components (

Table A3,

Appendix A).

The STACOLLECTIVE average (0.37) is lower than the SRACOLLECTIVE average (1), so, in the return stage, the number of goals from collective actions increased by 0.625 units compared to the first half of the season, which means a better ability to interact during the offensive phase through combinations of two or more players (

Table A3,

Appendix A).

The STAINDIV average (0.25) is lower than the SRAINDIV average (0.75), so, in the return stage, the number of goals from individual actions increased by 0.5 units compared to the first half of the season, which means a greater ability/power to overtake the opponent by dribbling (based on all known football techniques) (

Table A3,

Appendix A).

The STFDIRECT average (0.31) is lower than the SRFDIRECT average (0.1), so, in the return stage, the number of goals from direct free kicks increased by 0.68 units compared to the first half of the season, which means that individual kicks using various techniques were better performed (

Table A3,

Appendix A).

The STFINDIRECT average (0.31) is lower than the SRFINDIRECT average (0.81), so, in the re-turn stage, the number of goals from indirect free kicks increased by 0.5 units compared to the first half of the season, which means an increased ability of the studied players to surprise the opponent (the goalkeeper and fullbacks) through unexpected, unpredictable combinations without immediate defensive response (

Table A3,

Appendix A).

The STCORNER average (0.62) is lower than the SRCORNER average (2.12), so, in the return stage, the number of goals from corner kicks increased by 1.5 units compared to the first half of the season, which means that also in the two situations above (related to the execution of free kicks), the opponents' schemes with a hard-to-predict potential (situations that took the opponent by surprise: exchanges of places, screens, alternative executions on the short corner/long corner or at bar 1/bar 2)had a higher degree of success, of completion of the team’s attack (

Table A3,

Appendix A).

The STTOTAL average (3.06) is lower than the SRTOTAL average (7), so, in the return stage, the number of goals increased by 3.93 units compared to the first half of the season, which means a better ability to score goals and win the victory (

Table A3,

Appendix A).

It can be seen that t-Stat test values in the mode for the variables MIN (t=2.13; p=0.75) and PENALTY (t=2.13; p=0.54) are less than the minimum accepted two-tailed t-Critical value, with a very low level of significance (p-value > 0.05) and a 95% confidence level. This difference is NOT statistically significant. We may NOT extend our conclusion to the whole statistical population using the statistical inference t-test because t-Stat < t-Critical and p > 0.05. In other words, when repeating the test under similar conditions, we are not sure that we get similar results. Regarding the game of football, we can state that SSG training did NOT positively influence these technical/tactical offensive components for our team, but they are possible to be influenced by other individuals (

Table A3,

Appendix A).

The DTMIN average (691.25) is lower than the DRMIN average (704.37), so, in the return stage, the number of minutes played increased by 13.125 compared to the first half of the season, which means that there was a concern to keep the ball in play and even strengthen in-game relationships (

Table A3,

Appendix A).

The DTPENALTY average (1.18) is higher than the DRPENALTY average (1.31), so, in the return stage, the number of goals from penalty kicks increased by 0.12 units compared to the first half of the season, which means an enhanced potential to kick the ball where wanted, and also to mislead the opposing goalkeeper (

Table A3,

Appendix A).

Thus:

- -

the number of crosses increased from 4.63 to 6.88 (+2.25);

- -

the number of crosses with ball possession increased from 2.81 to 3.69 (+0.875);

- -

the number of corner kicks increased from 2.5 to 3.69 (+1.1875);

- -

the number of penalty kicks increased from 1.19 to 1.31 (+0.125);

- -

the number of throw-ins from the own half decreased from 3.94 to 2.69 (-1.25);

- -

the number of throw-ins from the opponent’s half increased from 2.5 to 4.38 (+1.875).

Instead, the results decreased for two indicators:

- -

vertical releases - from 5.75 to 4.31 (-1.4375);

- -

diagonal releases - from 4.19 to 3.88 (-0.3125).

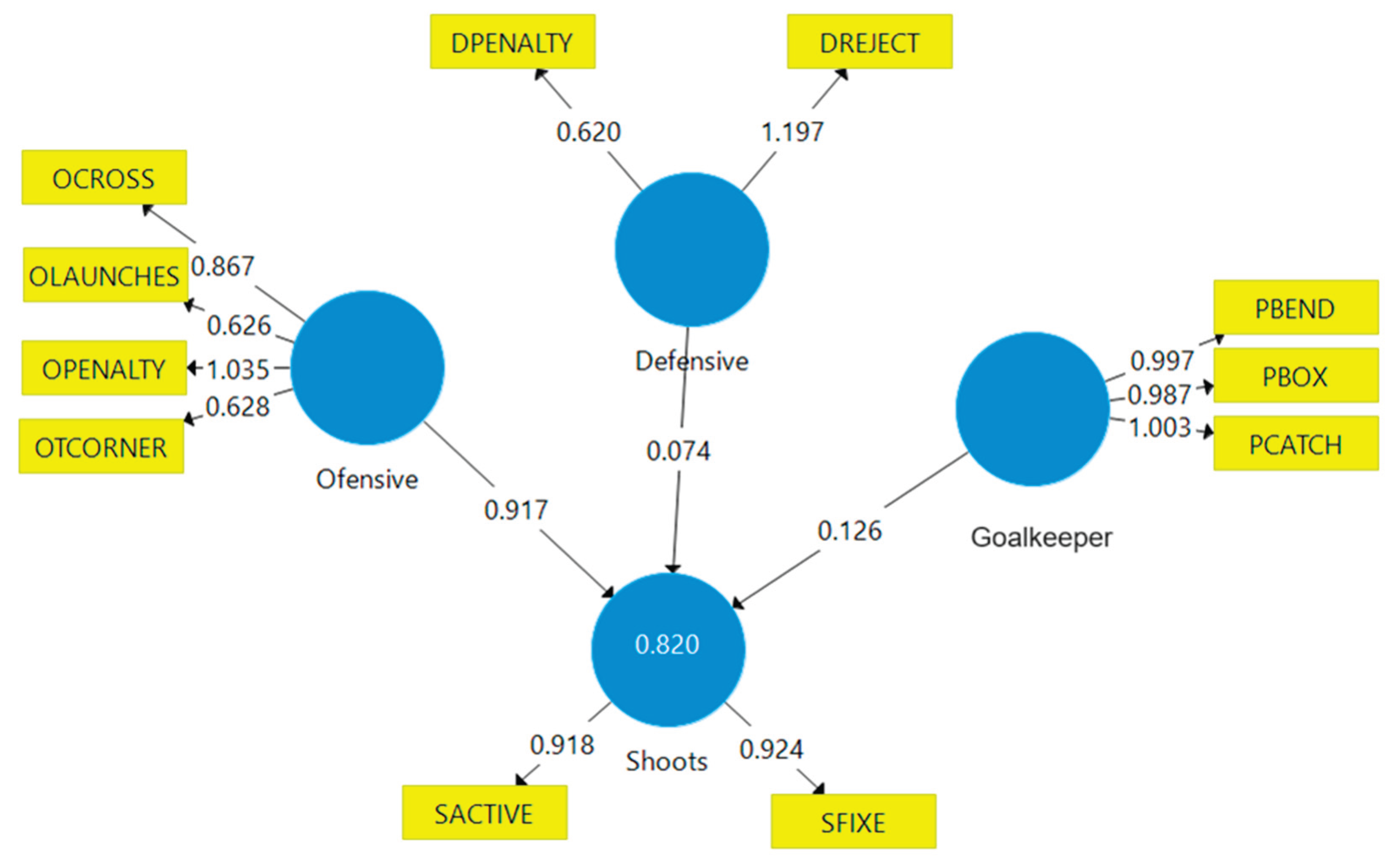

Based on the previously analyzed variables, we have designed a regression model highlighting that each of the offensive and defensive components or the goalkeeper's play has a positive influence on game performance (number of goals from fixed or active phases). The Path Coefficients: OffensiveShots (0.917), Goalkeeper Shots (0.126), and DefensiveShots (0.074) reveal once again the crucial importance of the offensive phase, demonstrating the positive effect of SSGs on improving game strategy and making inspired decisions in real-time (

Figure 2).

The model designed by us is very strong and reflects reality very well because all regression conditions are met, with CA (Cronbach's Alpha), Rho_A, and CR (Composite Reliability) greater than 0.7, and AVE (Average Variance Extracted)> 0.5 (Table 4). There is no multicollinearity between variables since VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) is less than 3 for each analyzed sub-item. R2 is 0.820, indicating a very strong positive correlation between variables. Adjusted R2 is 0.776, which means that the variance of the independent variables OFFENSIVE, DEFENSIVE, and GOALKEEPER ex-plains 77.6% of the variance of the dependent variable SHOTS (Table 1).

5. Discussion

The findings of this study offer a layered understanding of how small-sided games (SSGs) can influence both performance outcomes and inclusive dynamics within youth football environments. While several variables showed measurable improvement following the implementation of SSG-based training, others demonstrated minimal or no statistically significant change. Rather than viewing these outcomes in isolation, this discussion places them within broader pedagogical and tactical contexts.

5.1. Enhancing Offensive Dynamics Through Spatial Constraints

SSGs, by design, compress time and space—forcing players to make faster decisions, engage in more frequent ball contacts, and operate in tighter patterns of play. This appears to have translated into more structured offensive behaviors, evidenced by the increase in crosses, corner kicks, and goals from collective actions. The observed gains in team-level offensive metrics suggest that players de-veloped a stronger sense of spatial awareness, timing, and coordination.

These findings align with Lave and Wenger’s theory of Communities of Practice, where knowledge is co-constructed through shared activities. In SSGs, the frequent repetitions and cooper-ative play create an informal learning space where younger players develop not only skills but also group norms, tactical language, and situational awareness through engagement with peers.

5.2. Defensive Awareness and Recovery Actions

Defensive improvements were most notable in ball recoveries near the goal and in the team's own half. These gains reflect not only heightened anticipation and positioning but also a more proactive defensive stance. The increase in ball rejections with the foot also points to improved timing and intervention skills under pressure.

Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) can also shed light on this dimension: players engaged in consistent, meaningful team-based defensive actions may feel a stronger bond with their teammates. This sense of shared group identity can promote mutual accountability and defensive solidarity—two hallmarks of high-functioning teams.

On the other hand, metrics related to defensive headers and penalty concessions remained mostly unchanged. These areas, less frequently trained in SSGs due to their limited vertical dimension and rare aerial duels, may require supplementary training formats to improve.

5.3. SSGs and Social Inclusion: Structural Participation

Beyond tactical enhancements, the study reinforces the idea that SSGs offer a natural framework for inclusive team dynamics. With fewer players on the field and more touches per participant, the format equalizes involvement. This allows marginalized players—due to late selection, return from injury, or social factors—to re-integrate without hierarchical barriers.

The repetition of game-like scenarios also provides ample opportunity for each player to assume meaningful roles, which can foster a sense of belonging and competence. These are essential psy-chosocial drivers for inclusion, especially in adolescent development stages. For example, the ob-served increase in goals from collective actions suggests greater collaboration and interdependence among teammates, a hallmark of inclusive sport environments.

Additionally, the shift in throw-ins from the team’s own half to the opponent’s half may imply a broader team-based advancement rather than reliance on a single dominant player—indicating shared offensive responsibility and engagement across the squad.

5.4. Interpreting the Mixed Results

Some results, such as penalty kick outcomes or indirect tactical actions, showed minimal change or statistical insignificance. This may be due to the specificity of the SSG formats employed, which may not emphasize these aspects as much as traditional or full-pitch training methods. Rather than diluting the findings, these exceptions point to the need for a balanced training model that includes both constrained and open play scenarios.

5.5. Methodological Considerations and Future Directions

Given that the study was limited to a single team across one season, broader generalizations must be made cautiously. Several potential confounding variables could have influenced the observed improvements. These include natural player maturation, opponent variability, changes in coaching emphasis, psychological development, team dynamics, and even external environmental factors such as weather or school schedules.

While SSGs likely contributed meaningfully to the technical and tactical outcomes, isolating their exclusive impact without a control group limits the strength of causal claims. Future studies should address this by integrating control conditions, randomization, or crossover designs to better distinguish training effects from natural developmental trajectories or external influences.

To better assess the inclusion dimension, future studies should incorporate qualitative and ob-servational tools—such as peer evaluations, sociometric mapping, or interviews—focusing on per-ceived belonging, participation equity, and interpersonal trust within teams.

5.6. Summary

Overall, the implementation of small-sided games appears to offer tangible benefits in both technical-tactical development and the social structuring of youth football teams. While not a panacea, SSGs represent a powerful tool in a coach's methodological arsenal—particularly when applied with awareness of their limitations and complemented by other forms of training. Their potential to enhance inclusivity through structure and repeated engagement may be as valuable as their effect on scoring goals or recovering possession. Moreover, the observed results reflect and reinforce established theoretical models in sports education, demonstrating how cognitive, social, and technical growth can emerge through structured play environments like SSGs.

5.7. Inclusion as an Emergent Outcome of SSG Design

While the present study did not employ formal inclusion metrics, several technical outcomes may indirectly reflect enhanced social integration. For example, the increase in goals from collective actions—coupled with more consistent offensive actions across zones—suggests that multiple players were involved in constructing play, rather than relying on isolated individuals.

Similarly, the rise in opponent-half throw-ins and reduction of own-half throw-ins may point to sustained team advancement, indicative of coordinated, participatory attacking sequences. These dynamics support the idea that SSGs create environments where all players—regardless of previous experience or status—are afforded opportunities to contribute meaningfully.

Future studies should augment these insights with observational tools or self-report measures to more directly assess inclusion indicators such as perceived belonging, equitable decision-making, or communication patterns.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that small-sided games (SSGs) serve as an effective pedagogical and developmental tool in youth football, offering measurable benefits across both performance and social inclusion domains. The targeted use of SSGs among 13–14-year-old players led to significant improvements in technical and tactical execution during both offensive and defensive phases of play. These included increases in goal-scoring from collective actions, more effective ball recovery in critical zones, and enhanced in-game decision-making—hallmarks of modern football competence.

Beyond performance metrics, SSGs also functioned as inclusive environments by design, promoting equitable participation, frequent engagement, and collaborative dynamics. These features are particularly critical for adolescents from socially vulnerable backgrounds, for whom football can act as a vehicle of social empowerment and psychosocial development.

Our findings reinforce the pedagogical value of SSGs not only for enhancing sport-specific competencies but also for advancing broader educational goals such as team cohesion, identity formation, and mutual respect. When carefully structured and aligned with age-specific needs, SSGs support sustainable athlete development while simultaneously fostering inclusive social practices.

Thus, the implementation of SSG-based training protocols should be considered a best practice in youth football programs, particularly those seeking to balance competitive excellence with social responsibility. Future research should further investigate the longitudinal effects of SSGs on inclusion outcomes, incorporating qualitative methods to better capture players' lived experiences and team dynamics.

7. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D.P. and R.S.E.; methodology, R.S.E and M.D.D.; software, R.S.E and M.D.D.; validation, G.D.P.formal analysis, G.D.P..; investigation, G.D.P..; resources, G.D.P..; data curation, R.S.E and M.D.D; writing—original draft preparation, G.D.P.; writing—review and editing, G.D.P., R.S.E and M.D.D.; visualization, G.D.P; supervision, G.D.P.; project administration, G.D.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data Availability on request

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

T-Test for Paired Samples: Offensive actions.

Table A1.

T-Test for Paired Samples: Offensive actions.

| |

Variable |

Variable details |

Average |

Diff. |

Two-tailed t-Critical value |

p-Value |

| 1st HALF |

OTMIN |

Minutes |

691 |

-13.125 |

2.1314 |

0.7505 |

| RETURN |

ORMIN |

704 |

| 1st HALF |

OTCROSS |

CROSSES |

4.63 |

-2.25 |

2.1314 |

0.00742 |

| RETURN |

ORCROSS |

6.88 |

| 1st HALF |

OTCROSSPOSS |

CROSSES WITH BALL POSSESSION |

2.81 |

-0.875 |

1.7531 |

0.05 |

| RETURN |

ORCROSSPOSS |

3.69 |

| 1st HALF |

OTVERTRELEASES |

VERTICAL RELEASES |

5.75 |

1.4375 |

1.7531 |

0.03579 |

| RETURN |

ORVERTRELEASES |

4.31 |

| 1st HALF |

OTDIAGRELEASES |

DIAGONAL RELEASES |

4.19 |

0.3125 |

2.1314 |

0.6641 |

| RETURN |

ORDIAGRELEASE |

3.88 |

| 1st HALF |

OTCORNER |

CORNER KICKS |

2.5 |

-1.1875 |

2.1314 |

0.16699 |

| RETURN |

ORCORNER |

3.69 |

| 1st HALF |

OTTHROWOWN |

THROW-INS FROM THE OWN HALF |

3.94 |

1.25 |

1.7531 |

0.04425 |

| RETURN |

ORTHROWOWN |

2.69 |

| 1st HALF |

OTTHROWOPP |

THROW-INS FROM THE OPPONENT’S HALF |

2.5 |

-1.875 |

2.1314 |

0.01803 |

| RETURN |

ORTHROWOPP |

4.38 |

| 1st HALF |

OTPENALTY |

PENALTY KICKS |

1.19 |

-0.125 |

2.1314 |

0.54445 |

| RETURN |

ORPENALTY |

1.31 |

Table A2.

T-Test for Paired Samples: Defensive actions.

Table A2.

T-Test for Paired Samples: Defensive actions.

| |

Variable |

Variable details |

Average |

Diff. |

Two-tailed t-Critical value |

Two-tailed

p-value(T<=t)

|

| 1st HALF |

DTMIN |

Minutes |

691.25 |

13.125 |

2.13145 |

0.75 |

| RETURN |

DRMIN |

704.375 |

| 1st HALF |

DTRECOVPENALTY |

BALL RECOVERY IN THE OWN PENALTY AREA |

10.4375 |

0.25 |

2.13 |

0.62 |

| RETURN |

DRRECOVPENALTY |

10.6875 |

| 1st HALF |

DTRECOVGOAL |

BALL RECOVERY IN THE OWNGOAL AREA |

9.3125 |

1.625 |

2.13 |

0.012 |

| RETURN |

DRECOVGOAL |

10.9375 |

| 1st HALF |

DTRECOVOWN |

BALL RECOVERY IN THE OWNHALF |

6.5625 |

3.0625 |

2.13 |

0.001 |

| RETURN |

DRREVOCOWN |

9.625 |

| 1st HALF |

DTRECOVOPP |

BALL RECOVERY IN THE OPPOSING HALF |

2.75 |

1.25 |

2.13 |

0.006 |

| RETURN |

DRRECOVOPP |

4 |

| 1st HALF |

DTREJECTFOOT |

BALL REJECTION WITH THEFOOT FROM FIXED PHASES |

4.75 |

2.1875 |

2.13 |

0.001 |

| RETURN |

DRREJECTFOOT |

6.9375 |

| 1st HALF |

DTREJECTHEAD |

BALL REJECTION WITH THEHEAD FROM FIXED PHASES |

4.3125 |

-0.0625 |

2.13 |

0.884 |

| RETURN |

DRREJECTHEAD |

4.25 |

| 1st HALF |

DTPENALTY |

PENALITY KICKS |

0.8125 |

-0.375 |

2.13 |

0.18 |

| RETURN |

DRPENALTY |

0.4375 |

Table A3.

T-Test for Paired Samples: Testing the number of scored goals.

Table A3.

T-Test for Paired Samples: Testing the number of scored goals.

| |

Variable |

Variable details |

Average |

Diff. |

Two-tailed t-Critical value |

Two-tailed

p-value(T<=t)

|

| 1st HALF |

STMIN |

Minutes |

691.25 |

13.125 |

2.13145 |

0.75 |

| RETURN |

SRMIN |

704.375 |

| 1st HALF |

STACOLLECTIVE |

Goals FROM COLLECTIVE ACTION |

0.375 |

0.625 |

2.13 |

0.019 |

| RETURN |

SRACOLLECTIVE |

1 |

| 1st HALF |

STAINDIV |

Goals FROM INDIVIDUAL ACTION |

0.25 |

0.5 |

2.13 |

0.006 |

| RETURN |

SRAINDIV |

0.75 |

| 1st HALF |

STFDIRECT |

Goals FROM DIRECT FREE KICKS |

0.3125 |

0.6875 |

2.13 |

0.001 |

| RETURN |

SRFDIRECT |

1 |

| 1st HALF |

STFINDIRECT |

Goals FROM INDIRECT FREE KICKS |

0.3125 |

0.5 |

2.13 |

0.006 |

| RETURN |

SRFINDIRECT |

0.8125 |

| 1st HALF |

STCORNER |

Goals FROM CORNER KICKS |

0.625 |

1.5 |

2.13 |

0.000… |

| RETURN |

SRCORNER |

2.125 |

| 1st HALF |

STPENALTY |

Goals FROM PENALTY KICKS |

1.1875 |

0.125 |

2.13 |

0.54 |

| RETURN |

SRPENALTY |

1.3125 |

| 1st HALF |

STTOTAL |

TOTAL SCORED GOALS |

3.0625 |

3.9375 |

2.13 |

0.0002 |

| RETURN |

SRTOTAL |

7 |

References

- Vilamitjana, J.J. El Futbol, una Oportunidad de Integracion Social [Soccer, an Opportunity for Social Integration]. Boletín Electrónico REDAF 2014, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.M. El Futbol y Sus Posibilidades Socio-Educativas [Soccer and its Educational and Social Possibilities]. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte (https://wwwhomelessworldcuporg/). 2006, 4, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, J.; Yagüe, J.M.; Fernández, R.C.; Petisco, C. Efectos de un Entrenamineto con Juegos Reducidos Sobre la Tecnica y la Condicion Fisica de Jovenes Futbolistas [Effects of Small-Sided Games Training on Technique and Physical Condition of Young Footballers]. Ricyde.RevistaInternacionaldeCienciasdelDeporte 2014, 41, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampinini, E.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Castagna, C.; Abt, G.; Chamari, K.; Sassi, A.; Maecora, S.M. Factors Influencing Physiological Responses to Small-Sided Games. Journal of Sports Sciences 2007, 25, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. Optimizing the Use of Soccer Drills for Physiological Development. The Strength & Conditioning Journal 2009, 31, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, A.L.; Ford, P.R.; Twist, C. Small-Sided Games: The Physiological and Technical Effect of Altering Pitch Size and Player Numbers. Insight 2004, 7, 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- Barnabé, L.; Volossovitch, A.; Ferreira, A.P. Effect of Small-Sided Games on the Physical Performance of Young Football Players of Different Ages and Levels of Practice. In: D. Peters and P. O’Donoghue (Eds.), Proceedings of World Congress "Performance Analysis of Sport IX” 2014 (pp. 71-76). Routledge.

- Almeida, C.H.; Volossovitch, A.; Duarte, R. Influence of Scoring Mode and Age Group on Passing Actions during Small-Sided and Conditioned Soccer Games. Human Movement 2017, 18, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javier, D.G.; Martín, J.; Jesús, P. Fútbol y Racismo: Un Problema Científico y Social [Soccer and Racism: A Scientific and Social Problem]. Ricyde.RevistaInternacionaldeCienciasdelDeporte http://wwwcafydcom/REVISTA/art5n3a06pdf. 2006, 3, 68–94. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro-Rueda, M.; Fernández-Cerero, J. El Deporte Inclusivo: Un Camino Hacia la Equidad y la Igualdad de Oportunidades [Inclusive Sport: A Pathway to Equity and Equal Opportunities]. Retos 2024, 51, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memmert, D. Teaching Tactical Creativity in Sport: Research and Practice2015. Routledge. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Espínola, C.; Robles, M.T.A.; Fuentes-Guerra, F.J.G. Small-Sided Games as a Methodological Resource for Team Sports Teaching: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blondeau, J. The Influence of Field Size, Goal Size and Number of Players on the Average Number of Goals Scored per Game in Variants of Football and Hockey: The Pi-Theorem Applied to Team Sports. Journal of Quantitative Analysis in Sports 2020, 17, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J.; Young, W.; Farrow, D.; Bahnert, A. Comparison of Agility Demands of Small-Sided Games in Elite Australian Football. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2013, 8, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonney, N.; Ball, K.; Berry, J.; Larkin, P. Effects of Manipulating Player Numbers on Technical and Physical Performances Participating in an Australian Football Small-Sided Game. Journal of Sports Sciences 2020, 38, 2430–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.J.; Figueiredo, T.; Ferreira, C.; Espada, M. Physiological and Physical Effects Associated with Task Constraints, Pitch Size, and Floater Player Participation in U-12 1×1 Soccer Small-Sided Games. Human Movement 2022, 23, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, P.H.; da Costa, J.C.; Ramos-Silva, L.F.; Praça, G.M.; Vaz Ronque, E.R. Combined Effect of Game Position and Body Size on Network-Based Centrality Measures Performed by Young Soccer Players in Small-Sided Games. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 873518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangnier, S.; Cotte, T.; Brachet, O.; Coquart, J.; Tourny, C. Planning Training Workload in Football Using Small-Sided Games’ Density. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2019, 33, 2801–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modena, R.; Togni, A.; Fanchini, M.; Pellegrini, B.; Schena, F. Influence of Pitch Size and Goalkeepers on External and Internal Load during Small-Sided Games in Amateur Soccer Players. Sport Sciences for Health 2021, 17, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannicandro, I. Small-Sided Games and Size Pitch in Elite Female Soccer Players: A Short Narrative Review. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise 2021, 16, S361–S369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F.M.; Wong, Del P.; Martins, F.M.L.; Mendes, R.S. Acute Effects of the Number of Players and Scoring Method on Physiological, Physical, and Technical Performance in Small-Sided Soccer Games. Research in Sports Medicine 2014, 22, 380–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Football. Using Small-Sided Games 2024. https://ministry-of-football.com/small-sided-games/.

- Casamichana Gómez, D.; Castellano Paulis, J.; González-Morán, A.; García-Cueto, H.; García-López, J. Demanda Fisiológica en Juegos Reducidos de Fútbol con Diferente Orientación del Espacio [Physiological Demand in Small-Sided Games on Soccer with Different Orientation of Space]. Ricyde.RevistaInternacionaldeCienciasdelDeporte 2011, 23, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J.; Fernández, E.; Echeazarra, I.; Barreira, D.; Garganta, J. Influence of Pitch Length on Inter- and Intra-Team Behaviors in Youth Soccer. Anales de Psicología 2017, 33, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, F.M.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Sarmento, H.; Praça, G.M.; Afonso, J.; Silva, A.F.; Rosemann, T.J.; Knechtle, B. Effects of Small-Sided Game Interventions on the Technical Execution and Tactical Behaviors of Young and Youth Team Sports Players: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 667041, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.667041Media OTCROSS (4.63) este mai mică decât media ORCROSS (6.88), deci in faza de retur a crescut cu 2.25unități numărul de centrări în ofensivă, față de tur, ceea ce dpdv al fotbalului inseamnă…... [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnabé, L.; Volossovitch, A.; Duarte, R.; Ferreira, A.P.; Davids, K. Age-Related Effects of Practice Experience on Collective Behaviours of Football Players in Small-Sided Games. Human Movement Science 2016, 48, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frencken, W.; Lemmink, K.A.P.M.; Visscher, C.; Dellemn, N. Oscillations of Centroid Position and Surface Area of Soccer Teams in Small-Sided Games. European Journal of Sport Science 2011, 11, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Haas, S.V.; Dawson, B.T.; Impellizzeri, F.M.; Coutts, A.J. (2011). Physiology of Small-Sided Games Training in Football: A Systematic Review. Sports Medicine 2011, 41, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, J.E.; Lago, C.; Gonçalves, B.; Maças, V.M.; Leite, N. Effects of Pacing, Status and Unbalance in Time Motion Variables, Heart Rate and Tactical Behaviour when Playing 5-A-Side Football Small-Sided Games. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2013, 17, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Haas, S.V.; Coutts, A.J.; Rowsell, G.J.; Dawson, B.T. Generic versus Small-Sided Game Training in Soccer. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2009, 30, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessitore, A.; Meeusen, R.; Piacentini, M.F.; Demarie, S.; Capranica., L. Physiological and Technical Aspects of “6-A-Side” Soccer Drills. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 2006, 46, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, D.M.; Drust, B. The Effect of Pitch Dimensions on Heart Rate Responses and Technical Demands of Small-Sided Soccer Games in Elite Players. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 2009, 12, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroso, J.; Rebelo, A.; Gomes-Pereira, J. Physiological Impact of Selected Game-Related Exercises. Journal of Sports Sciences 2004, 22, 522. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S.; Drust, B. Physiological and Technical Demands of 4v4 and 8v8 Games in Elite Youth Soccer Players. Kinesiology 2007, 39, 150–156. [Google Scholar]

- Katis, A.; Kellis, E. Effects of Small-Sided Games on Physical Conditioning and Performance in Young Soccer Players. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine 2009, 8, 374–380. [Google Scholar]

- Little, T.; Williams, A.G. Suitability of Soccer Training Drills for Endurance Training. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2006, 20, 316–319. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.; Owen, A.L. The Impact of Player Numbers on the Physiological Responses to Small-Sided Games. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 2007, 6, 99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, J.; Wisloff, U.; Engen, L.C.; Kemi, O.J.; Helgerud, J. Soccer Specific Aerobic Endurance Training. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2002, 36, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallo, J.; Navarro, E. Physical Load Imposed on Soccer Players during Small-Sided Training Games. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 2008, 48, 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hill-Haas, S.V.; Coutts, A.J.; Dawson, B.T.; Rowsell, G.J. Time-Motion Characteristics and Physiological Responses of Small-Sided Games in Elite Youth Players: The Influence of Player Number and Rule Changes. The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2010, 24, 2149–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).