1. Introduction

Human emotional experience is complex and involves inner speech activities and self-dialogue during semantic perception [

1]. These inner speech processes encode subjective emotional states and elicit neural activation in regions such as the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex. These patterns partially overlap with those observed during emotional expression [

2,

3,

4]. Therefore, emotion constitutes not merely a physiological or behavioral response but also involves cognitive-semantic processing. Emotional states activate their associated semantic networks, while semantic representations contribute to the refined construction of emotional experience [

7,

8,

9]. Long-sequence semantic decoding can effectively extract context-dependent information during emotional construction, thereby providing the foundation for fine-grained emotional representation [

10,

11].

Common neuroimaging modalities for emotion decoding primarily include electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG), functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [

12]. EEG and MEG offer millisecond temporal resolution but poor spatial specificity due to volume conduction and field spread, making source localization inherently uncertain [

13]. For fNIRS, although it can provide relatively high spatial resolution, its measurement depth is only 2-3 cm [

14]. In contrast, fMRI offers high spatial resolution and whole-brain coverage. This technique can not only enable precise localization of emotion related brain regions but also supports simultaneous detection of co-activation patterns between language processing networks and emotion regulation systems via blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signals [

15]. These features provide a clear advantage for studying the neural mechanisms of emotion and semantic interaction in the Chinese context.

Traditional emotion classification methods typically rely on short-sequence emotion-induction paradigms and machine learning (ML) algorithms. Kassam et al. elicited nine discrete emotions using word-cued spontaneous emotion induction tasks, achieving a rank accuracy of 0.84 in fMRI-based emotion discrimination [

16]. Saarimäki et al. employed multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA) to distinguish six basic emotions, demonstrating good cross-subject generalizability [

17]. However, conventional algorithms show significantly reduced decoding accuracy when the number of target emotion categories increases, and these algorithms face constraints from short stimulus sequences, non-naturalistic experimental paradigms, and coarse-grained emotion classification [

18].

In recent years, large language models (LLMs) exemplified by GPT have demonstrated outstanding performance across diverse domains. These models can effectively capture rich contextual semantic representations and exhibit deep-level semantic reasoning capabilities, offering a novel approach to long-sequence emotion decoding [

19]. Tang et al. developed an fMRI based generative decoding framework that maps brain activity patterns into the latent semantic space of LLMs, achieving neural reconstruction of continuous English speech (BERTScore = 0.82) and revealing the distributed encoding characteristics of the brain’s language network [

20]. However, current research has two critical limitations. First, existing methods have not been validated on high-context language systems such as Chinese [

21]. Second, prior studies have primarily focused on decoding basic semantic content, failing to further examine the subtle emotional components of language processing [

22]. These limitations constrain our understanding of the neural mechanisms that underlie language and emotion interaction in real-world scenarios.

Accordingly, this study aims to develop and validate a fine-grained semantic and emotion decoding framework for extended Chinese narratives, bridging the current gap in understanding the neural mechanisms underlying language-emotion interactions. The innovations of this study include:

Extended emotion decoding in high-context language: This study investigates the feasibility of long-sequence emotion decoding in Chinese, extending emotion decoding to high-context language systems.

Fine-grained emotion decoding with SED-GPT: We propose a novel fine-grained decoding framework (SED-GPT) for Chinese narratives, which aligns brain activity with LLM-based semantic vector representations to reconstruct inner speech semantics.

Dynamic neural interactions in emotion-semantic processing: By systematically examining the dynamic interplay between the language network and emotional systems during Chinese semantic processing, this work provides neural evidence for cognition-emotion coupling.

Overall, this approach is expected to promote the development of affective brain computer interfaces (BCI), demonstrating potential applications in depression treatment and cognitive behavioral therapy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

This study employed the publicly available dataset SMN4Lang to evaluate our model, which comprises structural MRI and functional MRI data from 12 participants, with each participant contributing 6 hours of fMRI data [

23].

At trial onset, a screen displayed the instruction "Waiting for scan", followed by an 8-second blank screen. The instruction then changed to "The audio will begin shortly. Please listen carefully" for 2.65 seconds before the auditory stimulus was presented.

The stimulus set consisted of 60 audio clips (4–7 minutes each) from People's Daily news stories, covering diverse topics including education and culture. All recordings were narrated by the same male speaker. Manual timestamp alignment was performed to ensure precise synchronization between the audio and corresponding textual transcripts.

Structural MRI and fMRI were acquired using a Siemens Prisma 3T scanner equipped with a 64-channel receive coil. T1-weighted images were obtained with a 3D MPRAGE sequence at an isotropic spatial resolution of 0.8 mm³ with the following parameters: TR = 2.4 s, TI = 1 s, TE = 2.22 ms, flip angle = 8°, FOV = 256 × 256 mm.

fMRI data were collected using a BOLD-sensitive T2*-weighted GE-EPI sequence with the following parameters: TR = 710 ms, TE = 30 ms, flip angle = 54°, in-plane resolution = 2 mm, FOV = 212 × 212 mm.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

In this research, fMRIPrep was used for batch preprocessing of the structural MRI and fMRI data in the Chinese semantic perception dataset. 4 participants were excluded after preprocessing due to extensive occipital lobe damage in their structural scans, leaving eight participants for analysis.

30 long-sequence task fMRI files were randomly sampled to identify brain regions showing significant activation during Chinese semantic perception and in response to twenty-one emotion word categories using second-level general linear model (GLM) [

24,

25]. Psychophysiological interaction analysis (PPI) then probed the neural pathways underlying semantic perception [

26].

In comparing activation between task and resting states, at the individual analysis stage we used a first level GLM based on the hemodynamic response function and an autoregressive noise model. In the group analysis we constructed group level activation statistical maps using a second level GLM. After applying a voxel level correction (p < 0.001, Z > 3.09) and filtering by a minimum cluster size of 50 voxels, we identified regions showing significant activation [

27].

In the study of neural pathways underlying Chinese semantic processing, BOLD signal time series were extracted from predefined brain seed regions. Physiological regressors, psychological regressors, and the original interaction regressor were constructed and then convolved with the hemodynamic response function. A first level GLM was fitted, followed by a second-level GLM group comparison to generate Z-statistic parametric maps. False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction (p < 0.001) was applied to identify brain regions exhibiting significant functional coupling with the semantic perception hubs [

26].

In this study, we used the Affective Lexicon Ontology to mark timestamps for 21 emotions (joy, calm, respect, praise, trust, love, well wishing, anger, sadness, disappointment, guilt, longing, panic, fear, shame, frustration, disgust, blame, jealousy, doubt, surprise) and constructed an event matrix to compare BOLD signal differences evoked by emotion words and neutral words [

28]. After multiple comparison correction and filtering by a minimum cluster size of 10 voxels, we identified the ROIs showing significant activation for each emotion category [

27].

Based on the significant activated brain regions and the functionally coupled regions identified above, along with prior knowledge of brain areas involved in Chinese semantic perception [

29,

30], MNI coordinates were extracted to generate ROI masks. Using these ROI masks, the fMRI response time series of voxels within each mask were extracted. The 3D coordinates of the voxels were then re-encoded into 1D indices, forming a 2D neural response matrix.

2.3. SED-GPT

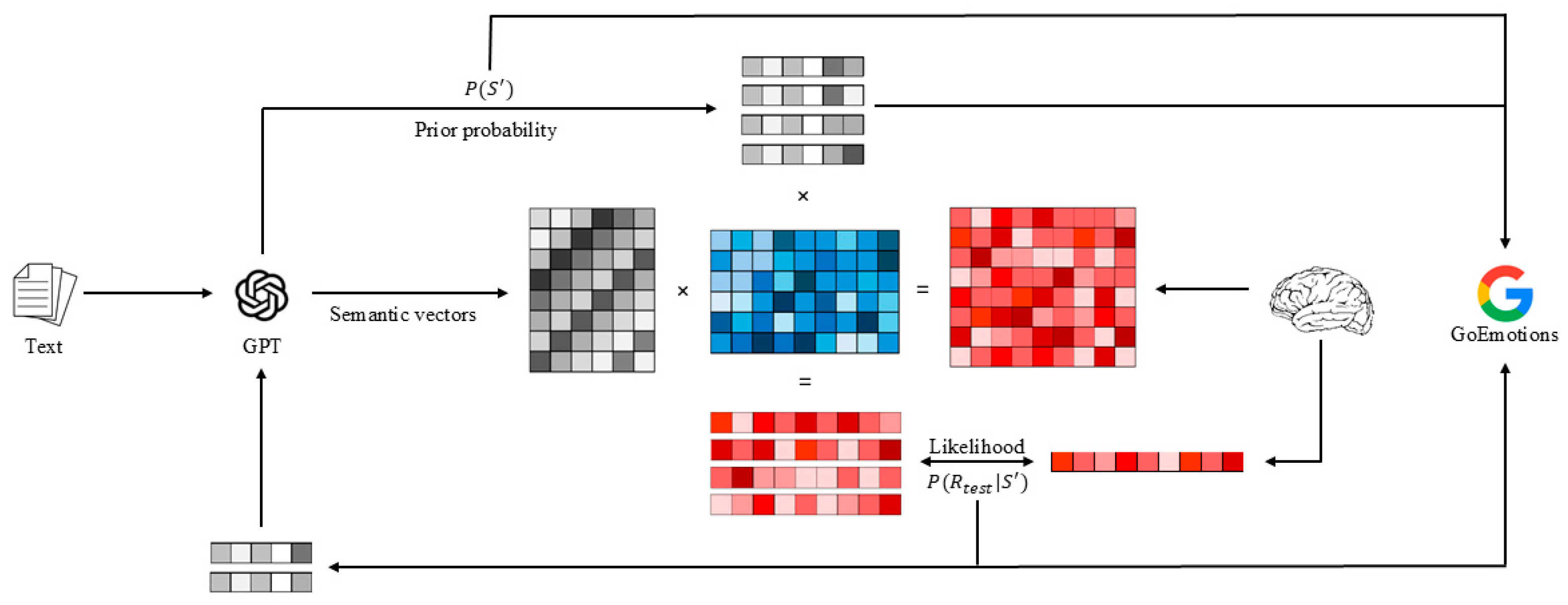

In this study, we propose a non-invasive method for long-sequence fine-grained semantics and emotions decoding, termed Semantic and Emotion Decoding Generative Pretrained Transformer (SED-GPT), as shown in

Figure 1.

In the encoding stage, we employed a Semantic to Brain Response Conversion Module (SBRCM) to minimize the inter-modal distance between linguistic stimuli and brain activity patterns. This module established a mapping between stimulus features and corresponding neural responses, incorporating a word rate model while estimating noise covariance matrices to improve model generalizability.

In the decoding stage, new semantic sequences were generated using linguistic priors from the language model and candidates. These sequences were then projected into neural response space through the SBRCM. The predicted simulated responses were compared with empirically observed brain activity patterns to compute likelihood distributions. Through iterative Bayesian integration of prior probabilities and likelihood estimates, the optimal semantic sequence was reconstructed. This iterative process enabled the generation of extended semantic vectors, whose emotional valence was subsequently classified into multiple categories using the GoEmotions framework [

31].

2.4. Fine-Tuning of LLMs

Due to the differences in writing systems and word boundary markers, English text contains clear separators (spaces) between words and exhibits rich morphological variation, making word-level tokenization effective for capturing semantic and syntactic information. In contrast, Chinese lacks explicit word boundaries, and each character carries its own meaning, so character-level tokenization allows flexible combination into complete lexical units [

32]. Consequently, English LLMs are typically trained with words as tokens, whereas Chinese LLMs use characters as tokens.

Character-encoded Chinese LLMs successfully avoid the complexity of Chinese word segmentation and require less computation for training [

32]. However, this design choice also means that high-performance, open-source Chinese GPT based on word-level tokens remain unavailable [

33,

34]. Character-level tokenization in Chinese GPT models does not align with word-based semantic encoding mechanisms: neuroimaging studies show that Mandarin users rely on explicit word boundaries, encoding meaning at the word rather than character level [

34,

35].

Unlike the character-level tokenization commonly used in Chinese LLMs, human language comprehension integrates lexical, syntactic, and contextual information via a distributed semantic network, activating and mapping the corresponding conceptual representations to enable word-level semantic processing and reasoning. In this process, newly encountered symbols are matched, retrieved and compared against existing network nodes, activating relevant concepts or semantic domains [

36]. This semantic information processing mechanism parallels the token-based encoding used in LLMs, where each input token is projected into a high-dimensional semantic space to capture and combine conceptual features [

37].

In this study, we indexed semantic feature vectors at the word level. We used GPT-4 to translate the time aligned Chinese transcripts into English in batch and used a GPT-2 model—fine-tuned on the DeepMind Q&A news corpus—to construct the stimulus matrix [

38]. The prompt for LLM-based timestamp conversion was: Convert the Chinese text into the most appropriate English. You may split intervals and their corresponding times; ensure that each interval corresponds to exactly one English word and that the xmax value at the end of each sentence remains consistent.

For each word-time pair at every timestamp, the word sequence was fed into the GPT language model, and the semantic feature vector of the target word was extracted from the 9th layer of the model, where the semantic feature vector represents a 768-dimensional semantic embedding [

39]. After obtaining the target words and their corresponding semantic feature vectors, these embedding vectors were temporally resampled to match the fMRI data acquisition time points using a three-lobe Lanczos filter [

40].

2.5. Semantic to Brain Response Conversion Moduler

In the encoding stage, the SBRCM receives input from two modalities: 768-dimensional semantic embeddings extracted from GPT-2 and BOLD signals recorded by fMRI. To account for the temporal-scale difference between these two modalities, the semantic stimulus vectors from 5-10th TRs prior to neural response onset were concatenated to construct a joint feature space. A linear mapping from this feature space to neural signals was then established through L2-regularized regression, with a word rate model being derived by estimating semantic occurrence frequency within individual TRs. To enhance model generalizability, a bootstrapping approach was incorporated in the encoding phase [

41].

In the decoding stage, candidate semantic sequences were initially generated based on GPT-2 prior probabilities. These candidate sequences were subsequently projected into neural response space through the SBRCM to produce predicted brain responses. Each candidate's likelihood was computed by evaluating the correspondence between its predicted response and the empirically observed neural signals. Candidate sequences exhibiting significant discrepancies with the actual brain response patterns were iteratively filtered out. The language model priors were then integrated with the neural likelihoods, and beam search was employed to select a new set of candidate tokens, with this process being repeated until multiple complete text passages were generated. Finally, the sequence exhibiting the highest likelihood was selected, and the GoEmotions model was applied to extract an emotion probability distribution, thereby enabling the decoding of emotional content throughout the semantic perception process [

31].

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

2.6.1. Semantic Similarity

BERTScore, word error rate (WER) and Euclidean distance (ED) were employed to quantify how closely the decoded text matches the original stimulus.

BERTScore measures semantic overlap by aligning contextual embeddings of the candidate and reference texts to compute precision, recall and F1 score [

42]. Precision reflects the matching quality between the two texts. Recall reflects the extent of matching coverage. The F1 score balances both quality and coverage. The metrics are defined as follows:

where

denotes the set of candidate text vectors, and

denotes the set of reference text vectors.

ED computes the Euclidean distance between corresponding semantic vectors, where smaller values indicate greater vector proximity and consequently lower semantic reconstruction error [

43]. The metric is defined as follows:

where

denotes the set of candidate text vectors, and

denotes the set of reference text vectors.

Word error rate (WER) measures, at the word level, the proportion of insertion, deletion, and substitution errors between the predicted text and the reference text relative to the total number of words in the reference [

44]. The metric is defined as follows:

where

is the number of substitutions in the candidate text,

the number of deletions (words present in the reference but missing in the candidate),

the number of insertions (extra words in the candidate),

the total number of words in the reference text.

2.6.2. Emotional Similarity

For emotion decoding, the GoEmotions framework was applied to extract normalized emotion probability distributions from the decoded text [

31].

Cosine Similarity (CS) and Jensen-Shannon (JSS) similarities were then computed between two sets of comparisons: (a) 30 randomly sampled decoded emotion distributions and the true distributions, and (b) 30 randomly generated emotion distributions and true distributions. The emotion-decoding performance of SED-GPT was quantified through direct comparison of these similarity scores.

CS is defined as the cosine of the angle between the predicted and true probability vectors, reflecting the overall alignment of the distributions [

45]. To evaluate emotion similarity, we employed the following formula:

where the normalized emotion probability distribution of the decoded text is

, and the normalized emotion probability distribution of the random text is

.

JSS is defined as one minus the Jensen–Shannon divergence between the two distributions. JSS measures the similarity between the predicted emotion distribution and the true distribution [

46]. To evaluate semantic similarity, we employed the following formula:

where the normalized emotion probability distribution of the decoded text is

, and the normalized emotion probability distribution of the random text is

.

The similarity between the generated text and the reference text was quantified for each emotion category using GoEmotions with multi-emotion classifications. A similarity metric was defined through computation of the normalized ratio for each emotion category. The closer this ratio is to 1, the more consistent the predicted probabilities for that emotion between the two texts [

47]. To evaluate semantic similarity, we employed the following formula:

where the normalized emotion probability distribution of the decoded text is

, and the normalized emotion probability distribution of the random text is

.

3. Results

3.1. Brain Activation and Functional Connectivity of Chinese Semantic Perception

3.1.1. Brain Activation of Chinese Semantic Perception

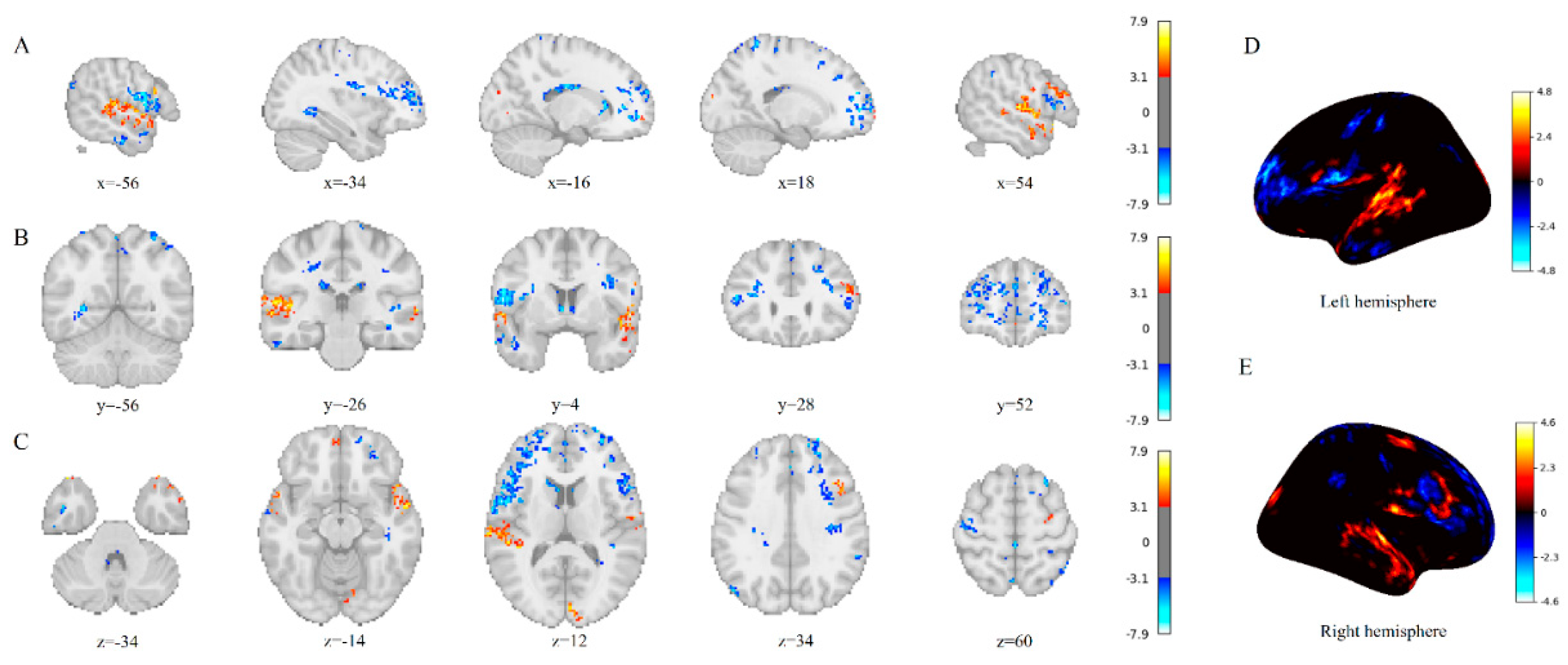

Comparative results between task-state and resting-state activation during the Chinese semantic perception task are shown in

Figure 2 and

Table 1.

During Chinese semantic processing task, significant activation was observed in the classical language network and semantic processing brain regions, accompanied by deactivation patterns in the default mode network (DMN) and primary sensorimotor cortices. Specifically, enhanced neural activity was identified in the bilateral frontal poles and posterior superior temporal gyri.

3.1.2. Functional Connectivity of Chinese Semantic Perception

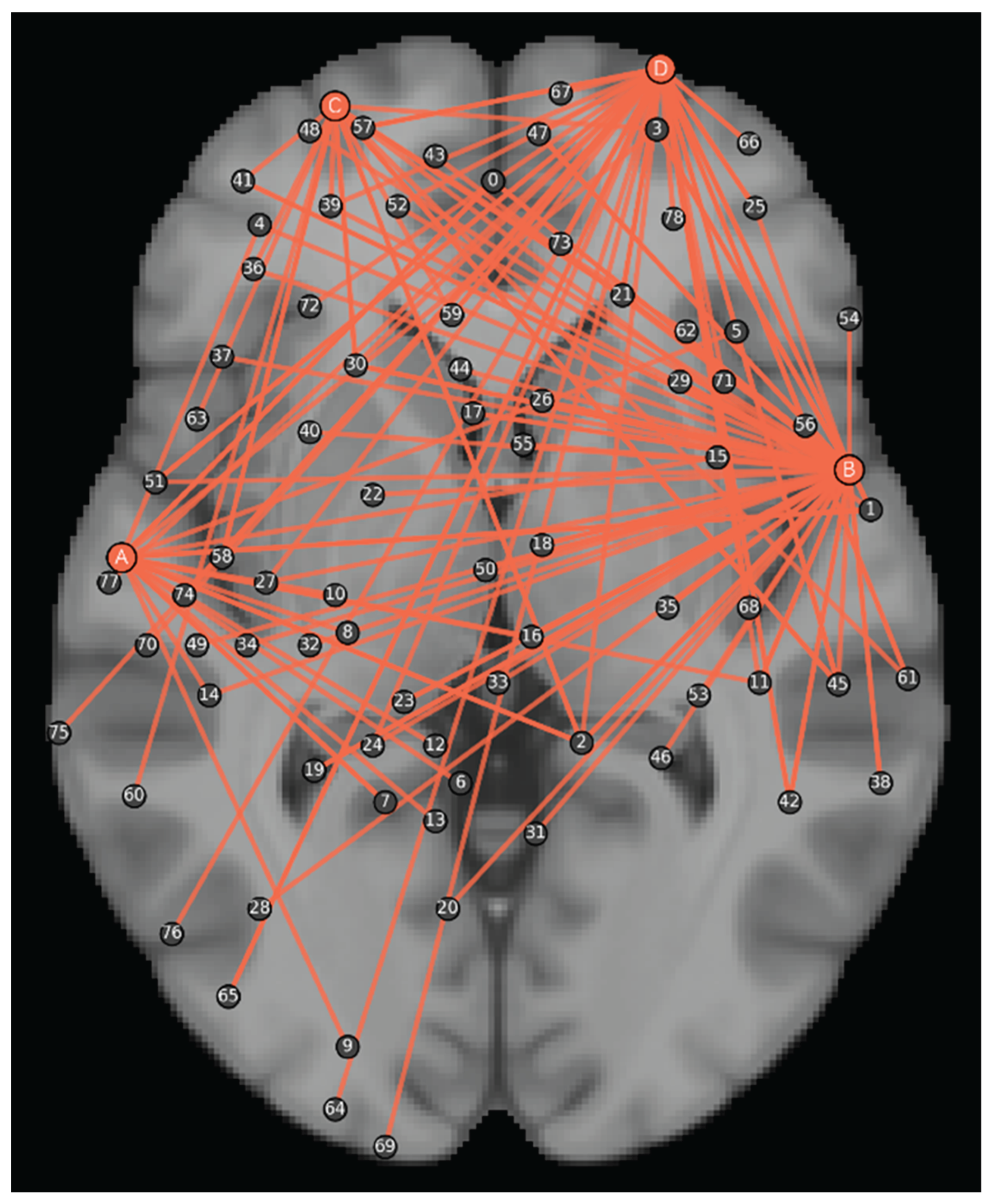

Based on the above activation results, we selected bilateral frontal poles and posterior superior temporal gyri as seed ROIs and performed PPI analysis to investigate the functional connectivity mechanisms underlying semantic processing, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 2.

The PPI analysis revealed that core semantic processing regions exhibited significant task-state functional coupling with distributed brain areas. These semantic processing regions showed significant functional coupling with the 79 distinct connectivity clusters (FDR, p<0.001) including paracingulate gyrus, anterior cingulate cortex and insular cortex.

These connections support processes such as semantic retrieval, contextual and narrative maintenance, motor simulation, attentional control, visual imagery and spatial scene construction, and affective and self-referential processing [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54].

3.2. Brain Regions Activated by Emotional Words

The comparative activation results between each category of emotion words and neutral words during Chinese semantic perception tasks are shown in

Table 3.

Under conditions of continuous natural language stimulation, all emotion categories elicit widely distributed neural activation patterns. Specifically, the processing of emotional words engaged not only classic limbic regions associated with affective processing, but also significantly activated: primary visual cortex, sensorimotor cortices, facial expression-modulation regions and high-level cognitive cortices [

55,

56,

57].

3.3. Semantic Decoding Performance

To assess semantic decoding performance, the text outputs generated by the decoder were quantitatively compared with both the original stimulus texts (ground truth) and randomly generated control texts, as shown in

Table 4.

EXP denotes the experimental group. RM denotes the random group. BERT denotes BERTScore F1.

Across all three metrics, the differences between the experimental and random groups were highly significant (p < 0.001). This indicates that the text produced by our semantic decoder significantly outperformed the random baseline at capturing and reconstructing semantic information in long Chinese narratives.

3.4. Emotion Decoding Performance

The emotion recognition performance was quantitatively assessed by computing both CS and JSS between the decoded emotion distributions and the corresponding true distributions. These metric values were compared against a random baseline condition, as shown in

Table 5.

EXP denotes the experimental group. RM denotes the random group.

For emotion recognition evaluation, we conducted multidimensional affective analysis of the decoded results and compared them with random baseline. Overall, the experimental group demonstrated significantly higher scores in both CS and JSS compared to the random group (p < 0.05).

The normalized ratios between the emotion distributions of decoded texts and the true emotion distributions were calculated. These ratios were then compared against random baseline distributions, as detailed in

Table 6.

The decoding accuracy rates for anger, disgust, embarrassment, fear, grief, joy, nervousness, neutral, remorse, sadness, caring, confusion, desire and love in the experimental group was significantly above the random baseline (p < 0.05). These results underscore the decoder’s robust sensitivity to a wide spectrum of emotional states under naturalistic language conditions.

4. Discussion

Conventional emotion decoding methods are constrained by factors such as short-sequence stimuli, coarse-grained categories, and low-context language systems, making it difficult to capture the interaction mechanisms between language and emotion in real-world scenarios [

16]. Our study demonstrates fine-grained emotion decoding in long-sequence narratives and provides a methodological basis for investigating the neural mechanisms underlying the interaction between emotion and semantic processing. It may address the bottleneck in dynamic emotion monitoring for depression treatment and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [

58].

In this research, we introduce SED-GPT, a fine-grained emotion decoding framework designed for long-sequence Chinese language processing, which establishes a neural alignment between brain activity and LLM-based semantic vector representations to enable inner speech semantic reconstruction. Moreover, our findings reveal the dynamic interplay between language-related cortical networks and affective neural systems during Chinese emotional semantic processing, providing novel neurocognitive evidence for thought-emotion integration mechanisms.

For semantic decoding, SED-GPT achieved a BERTScore F1 of 0.65, an ED of 12.432 and a WER of 0.924. For emotion decoding, it attained a CS of 0.504 and a JSS of 0.469. All decoding performances significantly surpass random baseline.

The GLM results from both task and resting states demonstrated that during Chinese semantic processing, the coordinated activation of the left frontopolar cortex and right medial frontopolar cortex likely involves top-down attentional modulation and cross-modal semantic integration [

59]. Bilateral posterior superior temporal gyri were engaged in acoustic feature analysis and semantic primitive extraction, and bilateral temporal poles participated in abstract semantic representation and integration of social context [

60,

61]. Concurrently, the suppression of the DMN and other non-task regions (e.g., the default mode network) indicates directed allocation of cognitive resources to core language networks [

62]. Activity along the left central sulcus during Chinese lexical ambiguity resolution suggests enhanced phonological working memory [

63]. The co-activation of the working memory network (left superior frontal gyrus to right superior parietal lobule) with the attentional network (right precuneus) supports context integration and interference suppression [

64]. Cross-modal activation of the left middle occipital gyrus implies that orthography–phonology associations may facilitate automatic mapping from speech to visual representations [

65]. In higher level comprehension (e.g., discourse level processing), bilateral frontal poles and middle frontal gyri support context maintenance and are implicated in controlled semantic retrieval [

66,

67].

PPI analyses showed that the right-hemisphere target seed region exhibited significant functional coupling with the paracingulate gyrus, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), and insular cortex. From a network perspective, this model can be reasonably explained theoretically. The paracingulate gyrus is primarily involved in self-monitoring and reality monitoring processes [

68], the anterior cingulate integrates negative emotions, pain and cognitive control [

69], and the insula enriches semantic understanding by integrating abstract semantic information with interoceptive bodily states and socio-emotional experience [

70]. This task-dependent functional coupling mechanism may collectively support the multi-level synergistic integration of semantic content with contextual and emotional cues during narrative comprehension [

71,

72].

The GLM contrast between emotional and neutral words suggests:

Network reorganization and resource redistribution. Emotional words were associated with widespread changes across cortical networks. High social value words (e.g., praise) activate an integrated network of empathic, motor simulation and evaluation, while activity in general executive control regions is significantly reduced [

57].

Embodied simulation mechanism. In the joy condition, significant activation was observed in the left and right precentral gyrus, which may involve the recruitment of oral and facial motor representations. In the praise condition, notable activation was detected in the postcentral gyrus and the anterior supramarginal gyrus, reflecting the engagement of somatosensory and speech-related pathways. These findings support the notion that abstract emotions participate in sensory-motor representation mapping [

56].

The emotion-visual imagery coupling mechanism. Positive emotions (e.g., joy, admiration) and negative emotions (e.g., fear) were associated with activation in the inferior occipital cortex, cuneus and right higher-order visual areas, revealing the multi-level integration of vivid mental imagery with emotional processing [

73].

The self/others reference and value assessment mechanism. Emotional words (e.g., admiration) activated the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and superior frontal gyrus, reflecting metacognitive simulation of self and others in complex social emotions [

74].

Suppression patterns of specific emotions. Emotional words (e.g., criticism) elicited large-scale deactivation in visual-semantic, sensorimotor and executive/metacognitive networks (e.g., middle frontal gyrus, frontal pole). This pattern may reflect down-regulation of DMN processing to concentrate cognitive resources on affective synesthesia and social reasoning network [

75].

Fine-grained emotion decoding results indicate that the proposed method can distinguish 14 emotional states from brain activity. Notably, negative emotions (anger, disgust, fear, grief, sadness) exhibit greater decoding accuracy, which may be attributed to humans’ preferential processing of negative stimuli. During disgust-related words processing, participants experienced embodied interoceptive imagery (e.g., nausea), activating the right somatosensory cortex (postcentral gyrus) [

76]. Concurrently, stronger engagement of higher-order cognitive regions (e.g., right frontal pole) was required to evaluate and regulate this negative emotional response (e.g., suppressing the "gagging" impulse) [

76]. Sadness-related words can cause significant suppression in right lateral occipital cortex, right precuneus and right frontal pole. It indicates that the subjects exhibited weakened imagery, spatial association, and metacognitive processing under sad emotions [

77]. Humans allocate more attentional, perceptual, learning and memory resources to negative stimuli, resulting in stronger and more stable neural responses with a higher signal-to-noise ratio, which facilitates emotion decoding [

78].

5. Conclusions

In this study, we achieved the textual reconstruction of semantic content by aligning fMRI signals induced by Chinese auditory narratives with semantic representations and further extracted multidimensional emotional features for classification. Our findings not only demonstrate the neural decoding of complex emotional components in the Chinese context but also highlight the immense potential of integrating large-scale language models with neuroimaging technology. Overall, this approach could advance the development of affective brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) and show promising applications in the treatment of depression and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.C. and L.M.; methodology, W.C. and Z.W.; software, W.C and Z.W.; validation, W.C and Z.W.; formal analysis, W.C and Z.W.; investigation, W.C. and L.M.; resources, L.M.; data curation, W.C and Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, W.C.; writing—review and editing, W.C and Z.W.; visualization, W.C.; supervision, L.M.; project administration, L.M.; W.C. and Z.W. contributed equally to this work and should be considered co-first author. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study used publicly available dataset, and the original data had already obtained ethical approval and informed consent from the participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FP |

Frontal Pole |

| PreCG |

Precentral Gyrus |

| PoCG |

Postcentral Gyrus |

| MFG |

Middle Frontal Gyrus |

| SFG |

Superior Frontal Gyrus |

| IFGpt |

Inferior Frontal Gyrus, pars triangularis |

| IFGoper |

Inferior Frontal Gyrus, pars opercularis |

| ACC |

Anterior Cingulate Cortex |

| ParaCG |

Paracingulate Gyrus |

| PCC |

Posterior Cingulate Cortex |

| PCG |

Posterior Cingulate Gyrus |

| SMA |

Supplementary Motor Area |

| FMC |

Frontomedial Cortex |

| FOC |

Frontal Orbital Cortex |

| COC |

Central Opercular Cortex |

| SCC |

Supracalcarine Cortex |

| LOCsup |

Lateral Occipital Cortex, superior division |

| LOCid |

Lateral Occipital Cortex, inferior division |

| LOCs |

Lateral Occipital Cortex, superior division |

| OP |

Occipital Pole |

| CunC |

Cuneal Cortex |

| PCunC |

Precuneous Cortex |

| MTG |

Middle Temporal Gyrus |

| MTGto |

Middle Temporal Gyrus, temporooccipital part |

| MTGpd |

Middle Temporal Gyrus, posterior division |

| MTGad |

Middle Temporal Gyrus, anterior division |

| STG |

Superior Temporal Gyrus |

| STGpd |

Superior Temporal Gyrus, posterior division |

| TP |

Temporal Pole |

| ITGto |

Inferior Temporal Gyrus, temporooccipital part |

| ITGpd |

Inferior Temporal Gyrus, posterior division |

| AG |

Angular Gyrus |

| SMGa |

Supramarginal Gyrus, anterior division |

| SMGp |

Supramarginal Gyrus, posterior division |

References

- Fernyhough, C.; Borghi, A.M. Inner speech as language process and cognitive tool. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2023, 27, 1180–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nummenmaa, L.; Saarimäki, H.; Glerean, E.; et al. Emotional speech synchronizes brains across listeners and engages large-scale dynamic brain networks. Neuroimage 2014, 102, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkin, A.; Egner, T.; Kalisch, R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011, 15, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Morrell, M.J.; Vogt, B.A. Contributions of anterior cingulate cortex to behaviour. Brain 1995, 118, 279–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, J.R.; Conant, L.L.; Humphries, C.J.; et al. Toward a brain-based componential semantic representation. Cogn. Neuropsychol. 2016, 33, 130–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenci, A.; Lebani, G.E.; Passaro, L.C. The emotions of abstract words: A distributional semantic analysis. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2018, 10, 550–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satpute, A.B.; Lindquist, K.A. At the neural intersection between language and emotion. Affective Sci. 2021, 2, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaillard, R.; Del Cul, A.; Naccache, L.; et al. Nonconscious semantic processing of emotional words modulates conscious access. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 7524–7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperberg, G.R.; Deckersbach, T.; Holt, D.J.; et al. Increased temporal and prefrontal activity in response to semantic associations in schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Guo, C.; Feng, H.; et al. A review of key technologies for emotion analysis using multimodal information. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 1504–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, Z.; et al. Decoding the flow: Causemotion for emotional causality analysis in long-form conversations. arXiv arXiv:2501.00778, 2025.

- Chaudhary, U. Non-invasive brain signal acquisition techniques: Exploring EEG, EOG, fNIRS, fMRI, MEG, and fUS. In Expanding Senses Using Neurotechnology: Volume 1—Foundation of Brain-Computer Interface Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 25–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, W.R.; Nunez, P.L.; Ding, J.; et al. Comparison of the effect of volume conduction on EEG coherence with the effect of field spread on MEG coherence. Stat. Med. 2007, 26, 3946–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, T.; Biondi, M. fNIRS in the developmental sciences. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2015, 6, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deCharms, C.R. Applications of real-time fMRI. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, K.S.; Markey, A.R.; Cherkassky, V.L.; et al. Identifying emotions on the basis of neural activation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saarimäki, H.; Gotsopoulos, A.; Jääskeläinen, I.P.; et al. Discrete neural signatures of basic emotions. Cereb. Cortex 2016, 26, 2563–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kragel, P.A.; LaBar, K.S. Decoding the nature of emotion in the brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016, 20, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Tay, Y.; Bommasani, R.; et al. Emergent abilities of large language models. arXiv arXiv:2206.07682, 2022.

- Tang, J.; LeBel, A.; Jain, S.; et al. Semantic reconstruction of continuous language from non-invasive brain recordings. Nat. Neurosci. 2023, 26, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Ai, Q.; Liu, Y.; et al. Generative language reconstruction from brain recordings. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Dong, G.; Guo, D.; et al. A survey on fMRI-based brain decoding for reconstructing multimodal stimuli. arXiv arXiv:2503.15978, 2025.

- Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. A synchronized multimodal neuroimaging dataset for studying brain language processing. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajula, J.; Tohka, J. How many is enough? Effect of sample size in inter-subject correlation analysis of fMRI. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2016, 2016, 2094601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.H.; Vilidaite, G.; Lygo, F.A.; et al. Power contours: Optimising sample size and precision in experimental psychology and human neuroscience. Psychol. Methods 2021, 26, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, X.; Zhang, Z.; Biswal, B.B. Understanding psychophysiological interaction and its relations to beta series correlation. Brain Imaging Behav. 2021, 15, 958–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roiser, J.P.; Linden, D.E.; Gorno-Tempinin, M.L.; et al. Minimum statistical standards for submissions to Neuroimage: Clinical. Neuroimage Clin. 2016, 12, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Lin, H.; Pan, Y.; et al. Constructing the affective lexicon ontology. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inf. 2008, 27, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Gao, J.H. A review of functional MRI application for brain research of Chinese language processing. Magn. Reson. Lett. 2023, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Luo, C.; et al. The neural basis of semantic cognition in Mandarin Chinese: A combined fMRI and TMS study. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2019, 40, 5412–5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demszky, D.; Movshovitz-Attias, D.; Ko, J.; et al. GoEmotions: A dataset of fine-grained emotions. arXiv arXiv:2005.00547, 2020.

- Si, C.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. Sub-character tokenization for Chinese pretrained language models. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2023, 11, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Han, X.; Zhou, H.; et al. CPM: A large-scale generative Chinese pre-trained language model. AI Open 2021, 2, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Cui, W.; Yang, W.; et al. Noninvasive decoding and reconstruction of continuous Chinese language semantics. J. Data Acquis. Process. 2025, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, G.R.E. Word Boundary Information and Chinese Word Segmentation.

- Binder, J.R.; Desai, R.H.; Graves, W.W.; et al. Where is the semantic system? A critical review and meta-analysis of 120 functional neuroimaging studies. Cereb. Cortex 2009, 19, 2767–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caucheteux, C.; Gramfort, A.; King, J.R. Disentangling syntax and semantics in the brain with deep networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR; 2021; pp. 1336–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Hermann, K.M.; Kocisky, T.; Grefenstette, E.; et al. Teaching machines to read and comprehend. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Huth, A. Incorporating context into language encoding models for fMRI. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deniz, F.; Nunez-Elizalde, A.O.; Huth, A.G.; et al. The representation of semantic information across human cerebral cortex during listening versus reading is invariant to stimulus modality. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 7722–7736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benara, V.; Singh, C.; Morris, J.X.; et al. Crafting interpretable embeddings for language neuroscience by asking LLMs questions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 124137. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Nogueira, R.; Yates, A. Pretrained Transformers for Text Ranking: Bert and Beyond; Springer Nature, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Elmore, K.L.; Richman, M.B. Euclidean distance as a similarity metric for principal component analysis. Mon. Weather Rev. 2001, 129, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Renals, S. Word error rate estimation for speech recognition: e-WER. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers); 2018, Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL); pp. 20–24. [CrossRef]

- Xia, P.; Zhang, L.; Li, F. Learning similarity with cosine similarity ensemble. Inf. Sci. 2015, 307, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F. On a generalization of the Jensen–Shannon divergence and the Jensen–Shannon centroid. Entropy 2020, 22, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podani, J.; Ricotta, C.; Schmera, D. A general framework for analyzing beta diversity, nestedness and related community-level phenomena based on abundance data. Ecol. Complex. 2013, 15, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, J.; Thompson, H.E.; Hallam, G.; et al. Exploring the role of the posterior middle temporal gyrus in semantic cognition: Integration of anterior temporal lobe with executive processes. Neuroimage 2016, 137, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simony, E.; Honey, C.J.; Chen, J.; et al. Dynamic reconfiguration of the default mode network during narrative comprehension. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacobbe, C.; Raimo, S.; Cropano, M.; et al. Neural correlates of embodied action language processing: A systematic review and meta-analytic study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2022, 16, 2353–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piai, V.; Roelofs, A.; Acheson, D.J.; et al. Attention for speaking: Domain-general control from the anterior cingulate cortex in spoken word production. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein, R.A. Parahippocampal and retrosplenial contributions to human spatial navigation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2008, 12, 388–396. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, R.L.; Hoffman, P.; Pobric, G.; et al. The semantic network at work and rest: differential connectivity of anterior temporal lobe subregions. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 1490–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennari, S.P.; Millman, R.E.; Hymers, M.; et al. Anterior paracingulate and cingulate cortex mediates the effects of cognitive load on speech sound discrimination. Neuroimage 2018, 178, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballotta, D.; Maramotti, R.; Borelli, E.; et al. Neural correlates of emotional valence for faces and words. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1055054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauk, O.; Johnsrude, I.; Pulvermüller, F. Somatotopic representation of action words in human motor and premotor cortex. Neuron 2004, 41, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citron, F.M.M. Neural correlates of written emotion word processing: A review of recent electrophysiological and hemodynamic neuroimaging studies. Brain Lang. 2012, 122, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchey, M.; Dolcos, F.; Eddington, K.M.; et al. Neural correlates of emotional processing in depression: Changes with cognitive behavioral therapy and predictors of treatment response. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 45, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van ckeren, M.J.; Rueschemeyer, S.A. Cross-modal integration of lexical-semantic features during word processing: Evidence from oscillatory dynamics during EEG. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davey, J.; Thompson, H.E.; Hallam, G.; et al. Exploring the role of the posterior middle temporal gyrus in semantic cognition: Integration of anterior temporal lobe with executive processes. Neuroimage 2016, 137, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeppel, D.; Idsardi, W.J.; Van Wassenhove, V. Speech perception at the interface of neurobiology and linguistics. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 1071–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eysenck, M.W.; Moser, J.S.; Derakshan, N.; et al. A neurocognitive account of attentional control theory: How does trait anxiety affect the brain’s attentional networks? Cogn. Emot. 2023, 37, 220–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, G.; Dong, Q.; Jin, Z.; et al. Mapping of verbal working memory in nonfluent Chinese–English bilinguals with functional MRI. Neuroimage 2004, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Y.; Ho, M.H.R.; Chen, S.H.A. A meta-analysis of fMRI studies on Chinese orthographic, phonological, and semantic processing. Neuroimage 2012, 63, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, J.R.; Burman, D.D.; Meyer, J.R.; et al. Development of brain mechanisms for processing orthographic and phonologic representations. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2004, 16, 1234–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. How context features modulate the involvement of the working memory system during discourse comprehension. Neuropsychologia 2018, 111, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfetti, C.A.; Frishkoff, G.A. The neural bases of text and discourse processing. Handb. Neurosci. Lang. 2008, 2, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Lavallé, L.; Brunelin, J.; Jardri, R.; et al. The neural signature of reality-monitoring: A meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2023, 44, 4372–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shackman, A.J.; Salomons, T.V.; Slagter, H.A.; et al. The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, A.D. How do you feel—now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simony, E.; Honey, C.J.; Chen, J.; et al. Dynamic reconfiguration of the default mode network during narrative comprehension. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, A.G.; Scott, B.; Gimbel, S.I.; et al. Functional brain connectivity during narrative processing relates to transportation and story influence. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 665319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatinelli, D.; Fortune, E.E.; Li, Q.; et al. Emotional perception: Meta-analyses of face and natural scene processing. Neuroimage 2011, 54, 2524–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immordino-Yang, M.H.; McColl, A.; Damasio, H.; et al. Neural correlates of admiration and compassion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 8021–8026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anticevic, A.; Cole, M.W.; Murray, J.D.; et al. The role of default network deactivation in cognition and disease. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2012, 16, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, B.; Keysers, C.; Plailly, J.; et al. Both of us disgusted in my insula: The common neural basis of seeing and feeling disgust. Neuron 2003, 40, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maddock, R.J. The retrosplenial cortex and emotion: New insights from functional neuroimaging of the human brain. Trends Neurosci. 1999, 22, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Finkenauer, C.; et al. Bad is stronger than good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 323–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).