Submitted:

18 August 2025

Posted:

19 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Enhancing the Th1/Th2 balance by promoting Th1 cell differentiation and increasing Th1 cells in circulation;

- Converting cold MSS/pMMR tumors to hot tumors by activating Th1 and NK cells in circulation and promoting their extravasation and trafficking to tumor sites;

- Creating conditions for ISV and de-novo neoantigen priming in the TME, including ICD in the context of an inflammatory microenvironment conditioned with inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ;

- Counter-regulation of tumor immunoavoidance and immunosuppression in TME by promoting continuous inflammatory cytokine release, including IL-12 and IFN-γ;

- Immunoenhancement of the de-novo neoantigen-specific anti-tumor adaptive immune response resulting from the ISV mechanism.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approvals

2.2. AlloStim® Manufacturing and Formulation

2.3. Eligibility

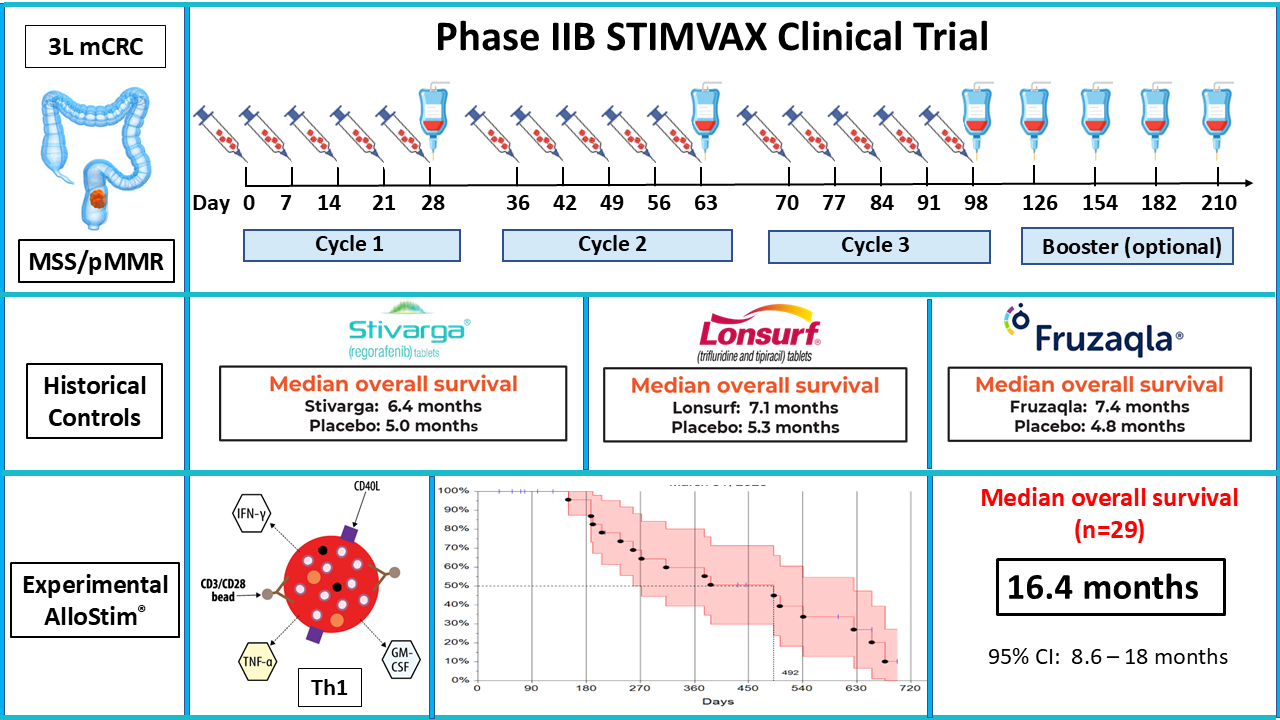

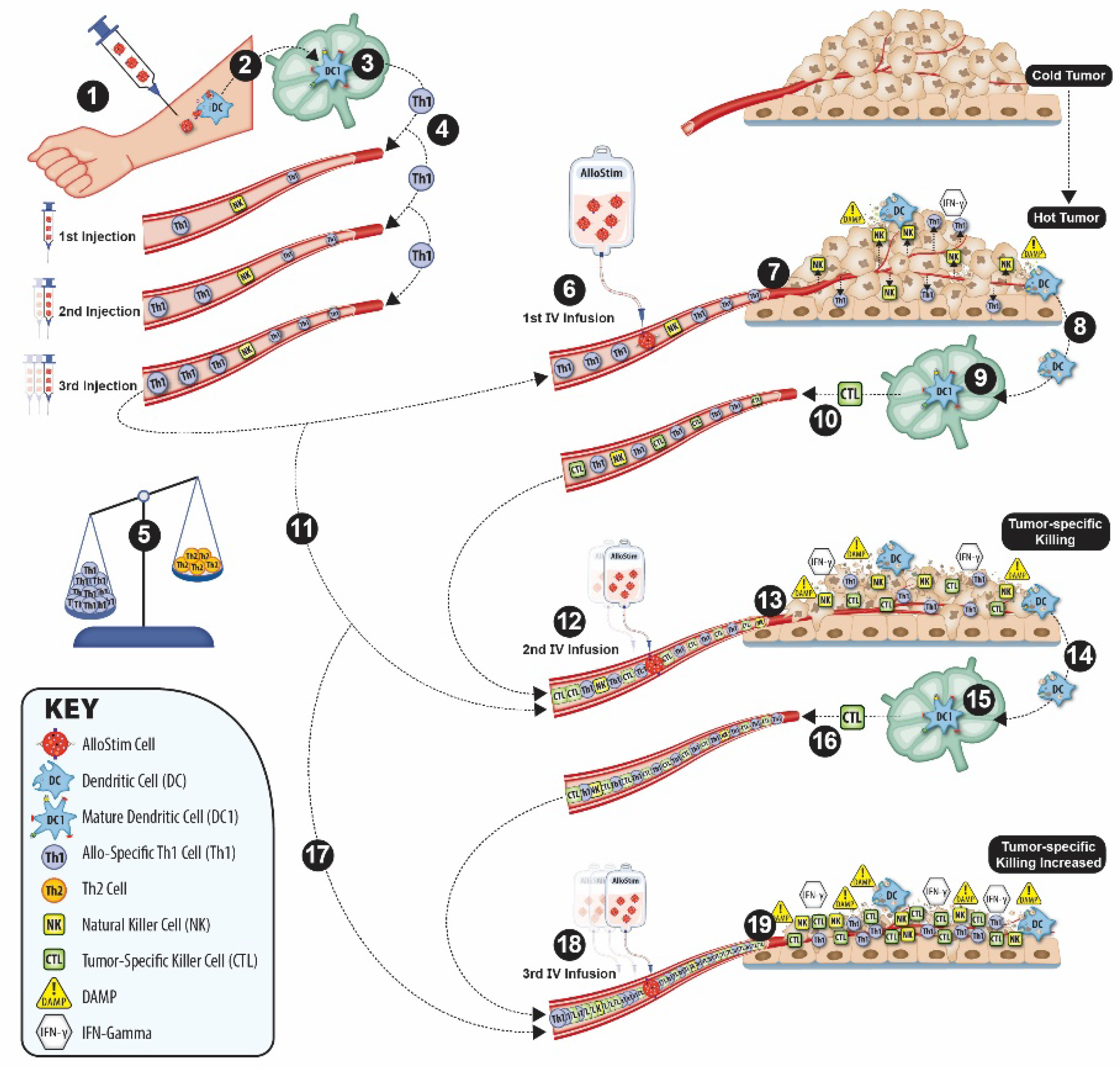

2.4. Protocol

2.5. Putative Mechanism of Action

2.5.1. Th1/Th2 Imbalance Correction

2.5.2. Conversion of Cold Tumors to Hot Tumors

2.5.3. Immunological Tumor Cell Death (ICD) and In-Situ Vaccination (ISV)

2.5.4. Counter-Regulation of Tumor Immunoavoidance and Immunosuppression

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Patient Characteristics

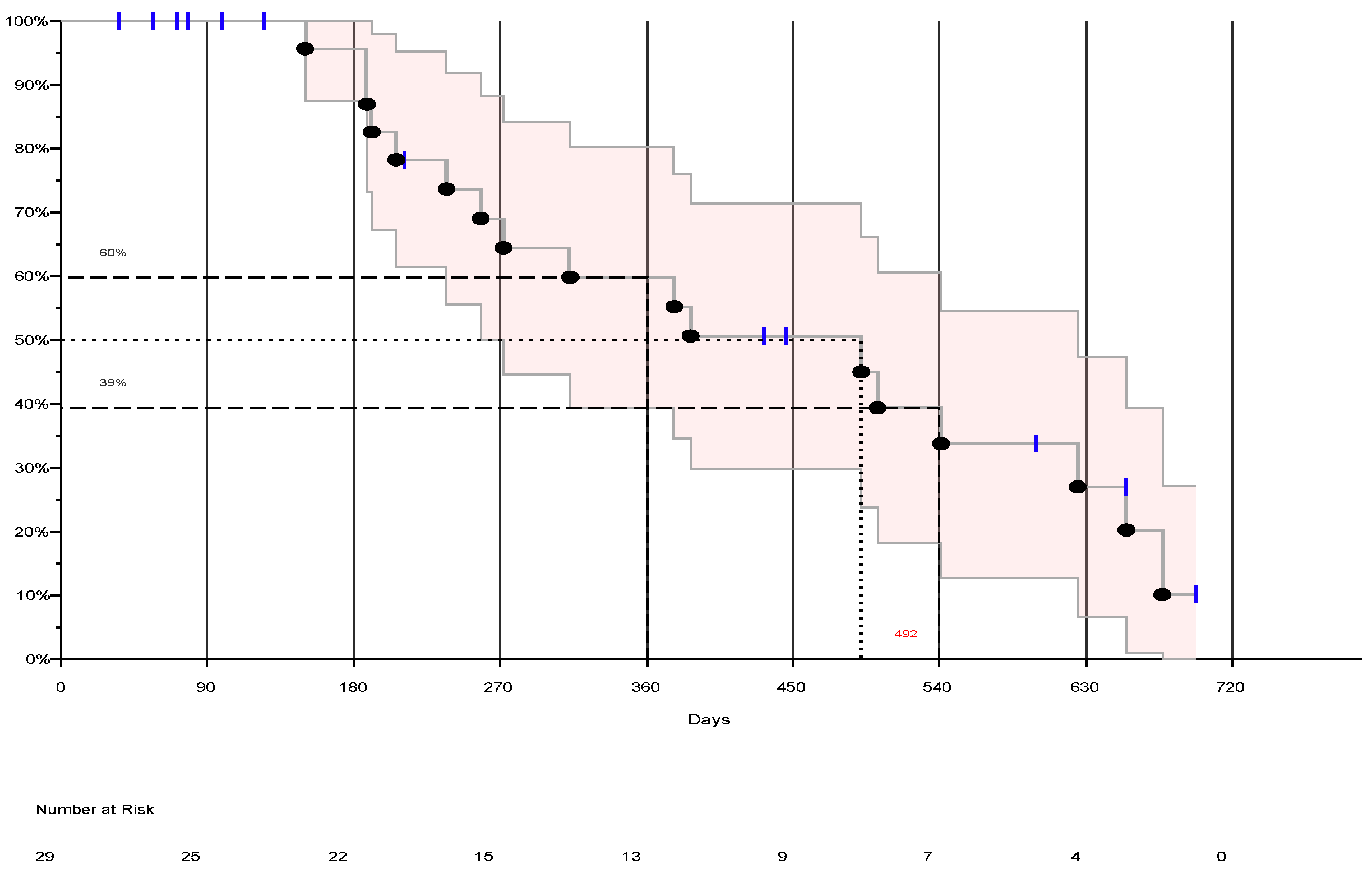

3.2. Overall Survival (OS)

3.2.1. Censor Metrics

3.2.2. Per Protocol Population (PPP)

3.2.3. Intent-to-Treat (ITT) Population

3.3. Comparison to Historical Controls

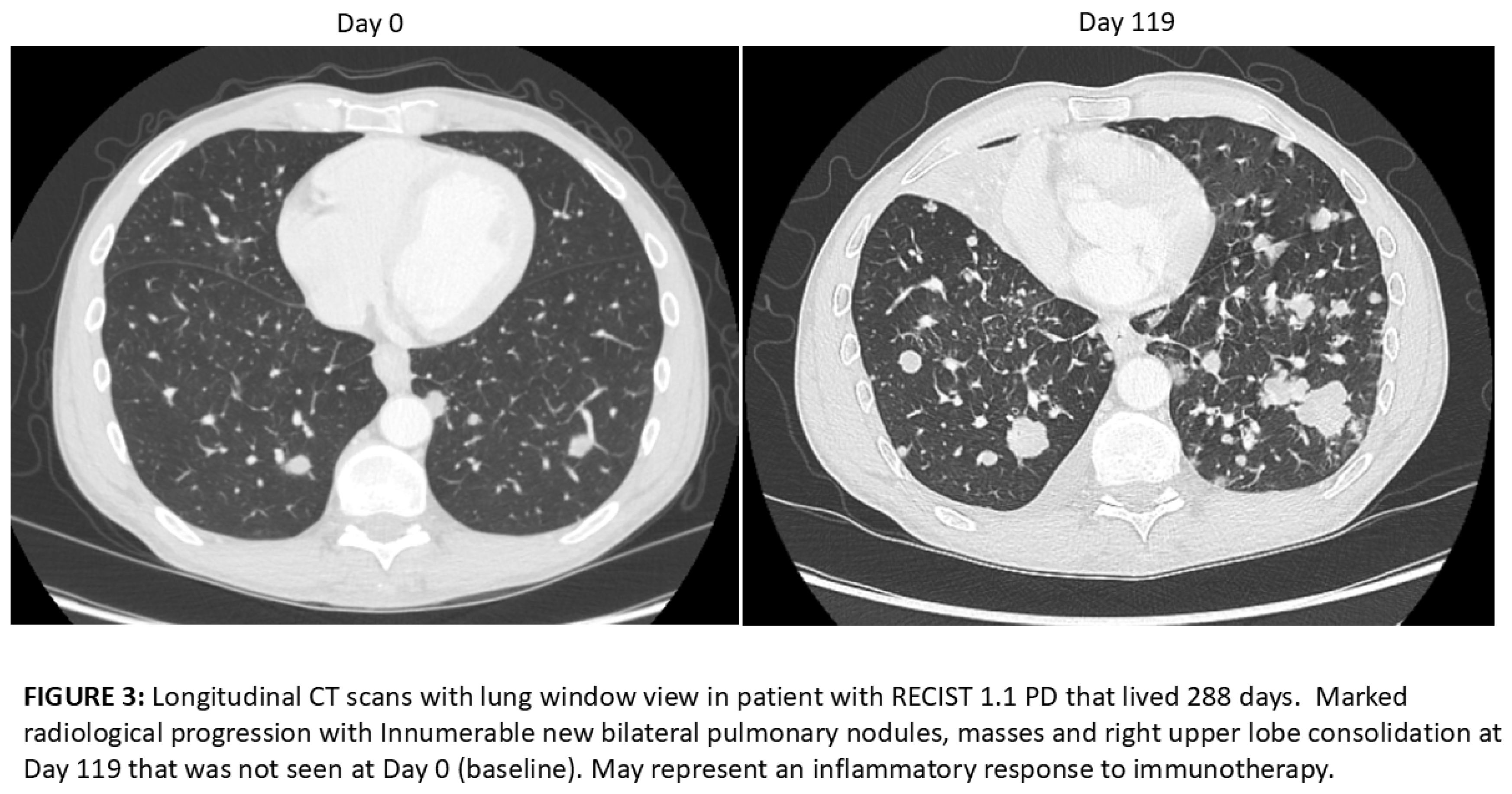

3.4. RECIST 1.1 Evaluation

3.5. Safety

3.5.1. Adverse Events (AE)

3.5.2. Serious Adverse Events (SAE)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFR | Code of Federal Regulations |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| EBV | Epstein-Barr Virus |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| HBV | Hepatitis B Virus |

| HCV | Hepatitis C Virus |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HTLV | Human T-Lymphotropic Virus |

| HLA | Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| IL | Interleukin |

| MHC | Major Histocompatobility Complex |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| Th1 | T-helper type 1 |

| TGF | Transforming Growth Factor |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| WNV | West Nile Virus |

References

- Baidoun, F.; Elshiwy, K.; Elkeraie, Y.; Merjaneh, Z.; Khoudari, G.; Sarmini, M.T.; Gad, M.; Al-Husseini, M.; Saad, A. Colorectal Cancer Epidemiology: Recent Trends and Impact on Outcomes. Current drug targets 2021, 22, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Huang, C. Application of immune checkpoint inhibitors in colorectal cancer. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2021, 46, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, C.R.; Goel, A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 2073–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, F.; Wu, S.; Yu, W. Progress of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Therapy for pMMR/MSS Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2024, 17, 1223–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, D.C.; Kavgaci, G.; Erul, E.; Syed, M.P.; Magge, T.; Saeed, A.; Yalcin, S.; Sahin, I.H. The Efficacy of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Microsatellite Stable Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Oncologist 2024, 29, e580–e600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzi, A.; Bekaii-Saab, T. Sequencing considerations in the third-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Am J Manag Care 2024, 30, S31–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aglietta, M.; Barkholt, L.; Schianca, F.C.; Caravelli, D.; Omazic, B.; Minotto, C.; Leone, F.; Hentschke, P.; Bertoldero, G.; Capaldi, A.; et al. Reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in metastatic colorectal cancer as a novel adoptive cell therapy approach. The European group for blood and marrow transplantation experience. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2009, 15, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Har-Noy, M.; Slavin, S. The anti-tumor effect of allogeneic bone marrow/stem cell transplant without graft vs. host disease toxicity and without a matched donor requirement? Medical hypotheses 2008, 70, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Har-Noy, M.; Zeira, M.; Weiss, L.; Slavin, S. Completely mismatched allogeneic CD3/CD28 cross-linked Th1 memory cells elicit anti-leukemia effects in unconditioned hosts without GVHD toxicity. Leukemia research 2008, 32, 1903–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, Z.R.; Connelly, C.F.; Fabrizio, D.; Gay, L.; Ali, S.M.; Ennis, R.; Schrock, A.; Campbell, B.; Shlien, A.; Chmielecki, J.; et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med 2017, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebot-Bral, L.; Coutzac, C.; Kannouche, P.L.; Chaput, N. Why is immunotherapy effective (or not) in patients with MSI/MMRD tumors? Bull Cancer 2019, 106, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niknafs, N.; Najjar, M.; Dennehy, C.; Stouras, I.; Anagnostou, V. Of Context, Quality, and Complexity: Fine-combing Tumor Mutation Burden in Immunotherapy Treated Cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westcott, P.M.K.; Sacks, N.J.; Schenkel, J.M.; Ely, Z.A.; Smith, O.; Hauck, H.; Jaeger, A.M.; Zhang, D.; Backlund, C.M.; Beytagh, M.C.; et al. Low neoantigen expression and poor T-cell priming underlie early immune escape in colorectal cancer. Nat Cancer 2021, 2, 1071–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, V.M.; Pan, X.; Soares, K.C.; Azad, N.S.; Ahuja, N.; Gamper, C.J.; Blair, A.B.; Muth, S.; Ding, D.; Ladle, B.H.; et al. Neoantigen-based EpiGVAX vaccine initiates antitumor immunity in colorectal cancer. JCI Insight 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Geng, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, Y.; Wu, F.; Liu, Z.; Ling, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, L. Hot and cold tumors: Immunological features and the therapeutic strategies. MedComm (2020) 2023, 4, e343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosolini, M.; Kirilovsky, A.; Mlecnik, B.; Fredriksen, T.; Mauger, S.; Bindea, G.; Berger, A.; Bruneval, P.; Fridman, W.H.; Pages, F.; et al. Clinical impact of different classes of infiltrating T cytotoxic and helper cells (Th1, th2, treg, th17) in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 2011, 71, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, P.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, G.; Gao, Z.; Tang, Z.; Dang, X.; Wu, Y. Profiles of immune cell infiltration and immune-related genes in the tumor microenvironment of colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 118, 109228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Zhang, T.; Kang, Z.; Guo, G.; Sun, Y.; Lin, K.; Huang, Q.; Shi, X.; Ni, Z.; Ding, N.; et al. Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells Act as a Marker for Prognosis in Colorectal Cancer. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha, N.; Sinha, S.; Valero, C.; Schaffer, A.A.; Aldape, K.; Litchfield, K.; Chan, T.A.; Morris, L.G.T.; Ruppin, E. Immune Determinants of the Association between Tumor Mutational Burden and Immunotherapy Response across Cancer Types. Cancer Res 2022, 82, 2076–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodallec, A.; Sicard, G.; Fanciullino, R.; Benzekry, S.; Lacarelle, B.; Milano, G.; Ciccolini, J. Turning cold tumors into hot tumors: harnessing the potential of tumor immunity using nanoparticles. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology 2018, 14, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Veena, M.S.; Shin, D.S. Key Players of the Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 830208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodzadeh Gholami, M.; Kardar, G.A.; Saeedi, Y.; Heydari, S.; Garssen, J.; Falak, R. Exhaustion of T lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment: Significance and effective mechanisms. Cell Immunol 2017, 322, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, D. Turn cold tumors hot by reprogramming the tumor microenvironment. Nature biotechnology 2025, 43, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iranzo, P.; Callejo, A.; Assaf, J.D.; Molina, G.; Lopez, D.E.; Garcia-Illescas, D.; Pardo, N.; Navarro, A.; Martinez-Marti, A.; Cedres, S.; et al. Overview of Checkpoint Inhibitors Mechanism of Action: Role of Immune-Related Adverse Events and Their Treatment on Progression of Underlying Cancer. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022, 9, 875974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Ni, Y.; Liang, X.; Lin, Y.; An, B.; He, X.; Zhao, X. Mechanisms of tumor resistance to immune checkpoint blockade and combination strategies to overcome resistance. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 915094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Liu, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Kuerban, K.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Ye, L. Challenges and New Directions in Therapeutic Cancer Vaccine Development. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.J.; Shan, N.; Li, L.Y.; Zhu, Y.S.; Lin, L.M.; Mao, C.C.; Hu, T.T.; Xue, X.Y.; Su, X.P.; Shen, X.; et al. Preliminary clinical study of personalized neoantigen vaccine therapy for microsatellite stability (MSS)-advanced colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2023, 72, 2045–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielbowski, K.; Plewa, P.; Zadworny, J.; Bakinowska, E.; Becht, R.; Pawlik, A. Recent Advances in the Development and Efficacy of Anti-Cancer Vaccines-A Narrative Review. Vaccines (Basel) 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merika, E.; Saif, M.W.; Katz, A.; Syrigos, K.; Morse, M. Review. Colon cancer vaccines: an update. In Vivo 2010, 24, 607–628. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan, K.; T, D.; Hebbar, S.R.; Selvam, P.K.; Rambabu, M.; Anbarasu, K.; Rohini, K. Multi-omics and AI-driven immune subtyping to optimize neoantigen-based vaccines for colorectal cancer. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 19333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.T.; Li, X.; Lan, A.L.; Ji, P.F.; Zhu, Y.J.; Ma, X.Y. Advances and challenges in neoantigen prediction for cancer immunotherapy. Frontiers in immunology 2025, 16, 1617654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blass, E.; Ott, P.A. Advances in the development of personalized neoantigen-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021, 18, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczynski, J.R.; Nowak, M. Cancer Immunoediting: Elimination, Equilibrium, and Immune Escape in Solid Tumors. Exp Suppl 2022, 113, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Donnell, J.S.; Teng, M.W.L.; Smyth, M.J. Cancer immunoediting and resistance to T cell-based immunotherapy. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology 2019, 16, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K.G.; Stromnes, I.M.; Greenberg, P.D. Obstacles Posed by the Tumor Microenvironment to T cell Activity: A Case for Synergistic Therapies. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikhlary, S.; Lopez, D.H.; Moghimi, S.; Sun, B. Recent Findings on Therapeutic Cancer Vaccines: An Updated Review. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giram, P.; Md Mahabubur Rahman, K.; Aqel, O.; You, Y. In Situ Cancer Vaccines: Redefining Immune Activation in the Tumor Microenvironment. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2025, 11, 2550–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somu, P.; Mohanty, S.; Basavegowda, N.; Yadav, A.K.; Paul, S.; Baek, K.H. The Interplay between Heat Shock Proteins and Cancer Pathogenesis: A Novel Strategy for Cancer Therapeutics. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seigneuric, R.; Mjahed, H.; Gobbo, J.; Joly, A.L.; Berthenet, K.; Shirley, S.; Garrido, C. Heat shock proteins as danger signals for cancer detection. Frontiers in oncology 2011, 1, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, A.K.; Mehrotra, S. Apoptosis - an Ubiquitous T cell Immunomodulator. J Clin Cell Immunol 2011, S3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshid, A.; Gong, J.; Calderwood, S.K. The role of heat shock proteins in antigen cross presentation. Front Immunol 2012, 3, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, K.L.; Lai, J.J.; Kono, H. Innate and adaptive immune responses to cell death. Immunol Rev 2011, 243, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvillo-Rodriguez, K.M.; Lorenzo-Anota, H.Y.; Rodriguez-Padilla, C.; Martinez-Torres, A.C.; Scott-Algara, D. Immunotherapies inducing immunogenic cell death in cancer: insight of the innate immune system. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1294434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.S.; Sohn, D.H. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Inflammatory Diseases. Immune Netw 2018, 18, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patidar, A.; Selvaraj, S.; Sarode, A.; Chauhan, P.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Saha, B. DAMP-TLR-cytokine axis dictates the fate of tumor. Cytokine 2018, 104, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coenon, L.; Geindreau, M.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Villalba, M.; Bruchard, M. Natural Killer cells at the frontline in the fight against cancer. Cell death & disease 2024, 15, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, R. Natural Killer Cells - Their Role in Tumour Immunosurveillance. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR 2017, 11, BE01–BE05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhatchinamoorthy, K.; Colbert, J.D.; Rock, K.L. Cancer Immune Evasion Through Loss of MHC Class I Antigen Presentation. Frontiers in immunology 2021, 12, 636568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Wang, X.F. Tumor immune evasion: Systemic immunosuppressive networks beyond the local microenvironment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2025, 122, e2502597122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamarron, B.F.; Chen, W. Dual roles of immune cells and their factors in cancer development and progression. International journal of biological sciences 2011, 7, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinay, D.S.; Ryan, E.P.; Pawelec, G.; Talib, W.H.; Stagg, J.; Elkord, E.; Lichtor, T.; Decker, W.K.; Whelan, R.L.; Kumara, H.; et al. Immune evasion in cancer: Mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies. Seminars in cancer biology 2015, 35 Suppl, S185–S198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, H.; Borden, E.C.; Stark, G.R. Interferons and their stimulated genes in the tumor microenvironment. Seminars in oncology 2014, 41, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Kohli, K.; Black, R.G.; Yao, L.; Spadinger, S.M.; He, Q.; Pillarisetty, V.G.; Cranmer, L.D.; Van Tine, B.A.; Yee, C.; et al. Systemic Interferon-gamma Increases MHC Class I Expression and T-cell Infiltration in Cold Tumors: Results of a Phase 0 Clinical Trial. Cancer immunology research 2019, 7, 1237–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Q.; Yu, X.; Sun, Q.; Li, H.; Sun, C.; Liu, L. Polysaccharides regulate Th1/Th2 balance: A new strategy for tumor immunotherapy. Biomed Pharmacother 2024, 170, 115976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llosa, N.J.; Cruise, M.; Tam, A.; Wicks, E.C.; Hechenbleikner, E.M.; Taube, J.M.; Blosser, R.L.; Fan, H.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.S.; et al. The vigorous immune microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer is balanced by multiple counter-inhibitory checkpoints. Cancer discovery 2015, 5, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provine, N.M.; Larocca, R.A.; Aid, M.; Penaloza-MacMaster, P.; Badamchi-Zadeh, A.; Borducchi, E.N.; Yates, K.B.; Abbink, P.; Kirilova, M.; Ng'ang'a, D.; et al. Immediate Dysfunction of Vaccine-Elicited CD8+ T Cells Primed in the Absence of CD4+ T Cells. J Immunol 2016, 197, 1809–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Mandelkow, T.; Debatin, N.F.; Lurati, M.C.J.; Ebner, J.; Raedler, J.B.; Bady, E.; Muller, J.H.; Simon, R.; Vettorazzi, E.; et al. A Tc1- and Th1-T-lymphocyte-rich tumor microenvironment is a hallmark of MSI colorectal cancer. J Pathol 2025, 266, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Har-Noy, M.a.L., W. A phase 2, multicenter, open-label study of AlloStim in-situ cancer vaccine immunotherapy as 3L therapy in MSS/pMMR metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2025, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, P.; Berghella, A.M.; Del Beato, T.; Cicia, S.; Adorno, D.; Casciani, C.U. Disregulation in TH1 and TH2 subsets of CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood of colorectal cancer patients and involvement in cancer establishment and progression. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII 1996, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knutson, K.L.; Disis, M.L. Augmenting T helper cell immunity in cancer. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord 2005, 5, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benichou, G.; Takizawa, P.A.; Olson, C.A.; McMillan, M.; Sercarz, E.E. Donor major histocompatibility complex (MHC) peptides are presented by recipient MHC molecules during graft rejection. The Journal of experimental medicine 1992, 175, 305–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Fuentes, M.P.; Baker, R.J.; Lechler, R.I. The alloresponse. Rev Immunogenet 1999, 1, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.M.; Gill, R.G. Direct and indirect allograft recognition: pathways dictating graft rejection mechanisms. Current opinion in organ transplantation 2016, 21, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iborra, S.; Abanades, D.R.; Parody, N.; Carrion, J.; Risueno, R.M.; Pineda, M.A.; Bonay, P.; Alonso, C.; Soto, M. The immunodominant T helper 2 (Th2) response elicited in BALB/c mice by the Leishmania LiP2a and LiP2b acidic ribosomal proteins cannot be reverted by strong Th1 inducers. Clinical and experimental immunology 2007, 150, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Har-Noy, M.; Zeira, M.; Weiss, L.; Fingerut, E.; Or, R.; Slavin, S. Allogeneic CD3/CD28 cross-linked Th1 memory cells provide potent adjuvant effects for active immunotherapy of leukemia/lymphoma. Leukemia research 2009, 33, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Yang, X.; Paoli-Bruno, J.; Sikes, D.; Marin-Ruiz, A.V.; Thomas, N.; Shane, R.; Har-Noy, M. Allo-Priming Reverses Immunosenescence and May Restore Broad Respiratory Viral Protection and Vaccine Responsiveness to the Elderly: Results of a Phase I/II Clinical Trial. Vaccines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.A.; Goyal, A.; Thapa, R.; Almalki, W.H.; Kazmi, I.; Alzarea, S.I.; Singh, M.; Rohilla, S.; Saini, T.K.; Kukreti, N.; et al. Uncovering the complex role of interferon-gamma in suppressing type 2 immunity to cancer. Cytokine 2023, 171, 156376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavcev, A.; Rybakova, K.; Svobodova, E.; Slatinska, J.; Honsova, E.; Skibova, J.; Viklicky, O.; Striz, I. Pre-transplant donor-specific Interferon-gamma-producing cells and acute rejection of the kidney allograft. Transplant immunology 2015, 33, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.T.; Kim, Y.M.; Sachs, T.; Mapara, M.; Zhao, G.; Sykes, M. Antitumor effect of donor marrow graft rejection induced by recipient leukocyte infusions in mixed chimeras prepared with nonmyeloablative conditioning: critical role for recipient-derived IFN-gamma. Blood 2003, 102, 2300–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.T.; Zhao, G.; Buchli, J.; Chittenden, M.; Sykes, M. Role of indirect allo- and autoreactivity in anti-tumor responses induced by recipient leukocyte infusions (RLI) in mixed chimeras prepared with nonmyeloablative conditioning. Clinical immunology 2006, 120, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, R.M. Natural killer cells and interferon. Critical reviews in immunology 1984, 5, 55–93. [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima, C.; Uekusa, Y.; Iwasaki, M.; Yamaguchi, N.; Mukai, T.; Gao, P.; Tomura, M.; Ono, S.; Tsujimura, T.; Fujiwara, H.; et al. A role of interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) in tumor immunity: T cells with the capacity to reject tumor cells are generated but fail to migrate to tumor sites in IFN-gamma-deficient mice. Cancer research 2001, 61, 3399–3405. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.; Wolgamott, L.; Yoon, S.O. Integrin trafficking and tumor progression. Int J Cell Biol 2012, 2012, 516789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gocher, A.M.; Workman, C.J.; Vignali, D.A.A. Interferon-gamma: teammate or opponent in the tumour microenvironment? Nature reviews. Immunology 2022, 22, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reschke, R.; Enk, A.H.; Hassel, J.C. Chemokines and Cytokines in Immunotherapy of Melanoma and Other Tumors: From Biomarkers to Therapeutic Targets. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grass, G.D.; Krishna, N.; Kim, S. The immune mechanisms of abscopal effect in radiation therapy. Current problems in cancer 2016, 40, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynders, K.; Illidge, T.; Siva, S.; Chang, J.Y.; De Ruysscher, D. The abscopal effect of local radiotherapy: using immunotherapy to make a rare event clinically relevant. Cancer treatment reviews 2015, 41, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.D.; Chen, D.; Luo, J.L.; Wang, Y.M.; Zhang, C.; Chen, S.Y.; Lin, Z.Q.; Zhang, P.D.; Tang, T.X.; Li, H.; et al. The different paradigms of NK cell death in patients with severe trauma. Cell death & disease 2024, 15, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornel, A.M.; Mimpen, I.L.; Nierkens, S. MHC Class I Downregulation in Cancer: Underlying Mechanisms and Potential Targets for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, M.H. Why current peptide-based cancer vaccines fail: lessons from the three Es. Immunotherapy 2009, 1, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solari, J.I.G.; Filippi-Chiela, E.; Pilar, E.S.; Nunes, V.; Gonzalez, E.A.; Figueiro, F.; Andrade, C.F.; Klamt, F. Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) related to immunogenic cell death are differentially triggered by clinically relevant chemotherapeutics in lung adenocarcinoma cells. BMC cancer 2020, 20, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Prete, A.; Salvi, V.; Soriani, A.; Laffranchi, M.; Sozio, F.; Bosisio, D.; Sozzani, S. Dendritic cell subsets in cancer immunity and tumor antigen sensing. Cellular & molecular immunology 2023, 20, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaCasse, C.J.; Janikashvili, N.; Larmonier, C.B.; Alizadeh, D.; Hanke, N.; Kartchner, J.; Situ, E.; Centuori, S.; Har-Noy, M.; Bonnotte, B.; et al. Th-1 lymphocytes induce dendritic cell tumor killing activity by an IFN-gamma-dependent mechanism. Journal of immunology 2011, 187, 6310–6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wculek, S.K.; Cueto, F.J.; Mujal, A.M.; Melero, I.; Krummel, M.F.; Sancho, D. Dendritic cells in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nature reviews. Immunology 2020, 20, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yosri, M.; Dokhan, M.; Aboagye, E.; Al Moussawy, M.; Abdelsamed, H.A. Mechanisms governing bystander activation of T cells. Frontiers in immunology 2024, 15, 1465889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Wen, C.; He, L.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, N.; Liang, L.; Hu, L.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Shi, M.; et al. Nilotinib boosts the efficacy of anti-PDL1 therapy in colorectal cancer by restoring the expression of MHC-I. Journal of translational medicine 2024, 22, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmamed, M.F.; Chen, L. A Paradigm Shift in Cancer Immunotherapy: From Enhancement to Normalization. Cell 2018, 175, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overacre-Delgoffe, A.E.; Chikina, M.; Dadey, R.E.; Yano, H.; Brunazzi, E.A.; Shayan, G.; Horne, W.; Moskovitz, J.M.; Kolls, J.K.; Sander, C.; et al. Interferon-gamma Drives T(reg) Fragility to Promote Anti-tumor Immunity. Cell 2017, 169, 1130–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janikashvili, N.; LaCasse, C.J.; Larmonier, C.; Trad, M.; Herrell, A.; Bustamante, S.; Bonnotte, B.; Har-Noy, M.; Larmonier, N.; Katsanis, E. Allogeneic effector/memory Th-1 cells impair FoxP3+ regulatory T lymphocytes and synergize with chaperone-rich cell lysate vaccine to treat leukemia. Blood 2011, 117, 1555–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Echeverz, J.; Haile, L.A.; Zhao, F.; Gamrekelashvili, J.; Ma, C.; Metais, J.Y.; Dunbar, C.E.; Kapoor, V.; Manns, M.P.; Korangy, F.; et al. IFN-gamma regulates survival and function of tumor-induced CD11b+ Gr-1high myeloid derived suppressor cells by modulating the anti-apoptotic molecule Bcl2a1. European journal of immunology 2014, 44, 2457–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duluc, D.; Corvaisier, M.; Blanchard, S.; Catala, L.; Descamps, P.; Gamelin, E.; Ponsoda, S.; Delneste, Y.; Hebbar, M.; Jeannin, P. Interferon-gamma reverses the immunosuppressive and protumoral properties and prevents the generation of human tumor-associated macrophages. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer 2009, 125, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothey, A.; Van Cutsem, E.; Sobrero, A.; Siena, S.; Falcone, A.; Ychou, M.; Humblet, Y.; Bouche, O.; Mineur, L.; Barone, C.; et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013, 381, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.J.; Van Cutsem, E.; Falcone, A.; Yoshino, T.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Mizunuma, N.; Yamazaki, K.; Shimada, Y.; Tabernero, J.; Komatsu, Y.; et al. Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2015, 372, 1909–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, A.; Lonardi, S.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Elez, E.; Yoshino, T.; Sobrero, A.; Yao, J.; Garcia-Alfonso, P.; Kocsis, J.; Cubillo Gracian, A.; et al. Fruquintinib versus placebo in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer (FRESCO-2): an international, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 study. Lancet 2023, 402, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Shen, L.; Peng, Z. Regorafenib, TAS-102, or fruquintinib for metastatic colorectal cancer: any difference in randomized trials? International journal of colorectal disease 2020, 35, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, G.W.; Taieb, J.; Fakih, M.; Ciardiello, F.; Van Cutsem, E.; Elez, E.; Cruz, F.M.; Wyrwicz, L.; Stroyakovskiy, D.; Papai, Z.; et al. Trifluridine-Tipiracil and Bevacizumab in Refractory Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. The New England journal of medicine 2023, 388, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nierengarten, M.B. New standard of care for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer 2023, 129, 1789–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Li, S.; Hou, X. A real-world study: third-line treatment options for metastatic colorectal cancer. Frontiers in oncology 2024, 14, 1480704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Qin, S.; Xu, R.; Yau, T.C.; Ma, B.; Pan, H.; Xu, J.; Bai, Y.; Chi, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. Regorafenib plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care in Asian patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CONCUR): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. The lancet oncology 2015, 16, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, J.; Luo, G.; Xu, C. Racial disparities in metastatic colorectal cancer outcomes revealed by tumor microbiome and transcriptome analysis with bevacizumab treatment. Frontiers in pharmacology 2023, 14, 1320028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qin, S.; Xu, R.H.; Shen, L.; Xu, J.; Bai, Y.; Yang, L.; Deng, Y.; Chen, Z.D.; Zhong, H.; et al. Effect of Fruquintinib vs Placebo on Overall Survival in Patients With Previously Treated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: The FRESCO Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2018, 319, 2486–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousin, S.; Cantarel, C.; Guegan, J.P.; Gomez-Roca, C.; Metges, J.P.; Adenis, A.; Pernot, S.; Bellera, C.; Kind, M.; Auzanneau, C.; et al. Regorafenib-Avelumab Combination in Patients with Microsatellite Stable Colorectal Cancer (REGOMUNE): A Single-arm, Open-label, Phase II Trial. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2021, 27, 2139–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, S.L.; Jatoi, A.; Strand, C.A.; Perlmutter, J.; George, S.; Mandrekar, S.J. Rates of and Factors Associated With Patient Withdrawal of Consent in Cancer Clinical Trials. JAMA oncology 2023, 9, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kim, M.G.; Lim, K.M. Participation in and withdrawal from cancer clinical trials: A survey of clinical research coordinators. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2022, 9, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Gao, J.; Wu, X. Pseudoprogression and hyperprogression after checkpoint blockade. International immunopharmacology 2018, 58, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, V.L.; Burotto, M. Pseudoprogression and Immune-Related Response in Solid Tumors. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2015, 33, 3541–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.V.; Weber, J.S.; Larkin, J.; Atkinson, V.; Grob, J.J.; Schadendorf, D.; Dummer, R.; Robert, C.; Marquez-Rodas, I.; McNeil, C.; et al. Nivolumab for Patients With Advanced Melanoma Treated Beyond Progression: Analysis of 2 Phase 3 Clinical Trials. JAMA oncology 2017, 3, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tazdait, M.; Mezquita, L.; Lahmar, J.; Ferrara, R.; Bidault, F.; Ammari, S.; Balleyguier, C.; Planchard, D.; Gazzah, A.; Soria, J.C.; et al. Patterns of responses in metastatic NSCLC during PD-1 or PDL-1 inhibitor therapy: Comparison of RECIST 1.1, irRECIST and iRECIST criteria. European journal of cancer 2018, 88, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Gao, Q.; Han, A.; Zhu, H.; Yu, J. The potential mechanism, recognition and clinical significance of tumor pseudoprogression after immunotherapy. Cancer biology & medicine 2019, 16, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, M.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Manos, M.P.; Bailey, N.; Buchbinder, E.I.; Ott, P.A.; Ramaiya, N.H.; Hodi, F.S. Immune-Related Tumor Response Dynamics in Melanoma Patients Treated with Pembrolizumab: Identifying Markers for Clinical Outcome and Treatment Decisions. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2017, 23, 4671–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettinger, S.N.; Horn, L.; Gandhi, L.; Spigel, D.R.; Antonia, S.J.; Rizvi, N.A.; Powderly, J.D.; Heist, R.S.; Carvajal, R.D.; Jackman, D.M.; et al. Overall Survival and Long-Term Safety of Nivolumab (Anti-Programmed Death 1 Antibody, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) in Patients With Previously Treated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2015, 33, 2004–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrissey, S.; Vasconcelos, A.G.; Wang, C.L.; Wang, S.; Cunha, G.M. Pooled Rate of Pseudoprogression, Patterns of Response, and Tumor Burden Analysis in Patients Undergoing Immunotherapy Oncologic Trials for Different Malignancies. Clinical oncology 2024, 36, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschfeld, A.; Gurell, D.; Har-Noy, M. Objective response after immune checkpoint inhibitors in a chemotherapy-refractory pMMR/MSS metastatic rectal cancer patient primed with experimental AlloStim® immunotherapy. Translational Medicine Communications 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yirgin, I.K.; Dogan, I.; Engin, G.; Vatansever, S.; Erturk, S.M. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Assessment of the performance and the agreement of iRECIST, irRC, and irRECIST. Journal of cancer research and therapeutics 2024, 20, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuoka, S.; Hara, H.; Takahashi, N.; Kojima, T.; Kawazoe, A.; Asayama, M.; Yoshii, T.; Kotani, D.; Tamura, H.; Mikamoto, Y.; et al. Regorafenib Plus Nivolumab in Patients With Advanced Gastric or Colorectal Cancer: An Open-Label, Dose-Escalation, and Dose-Expansion Phase Ib Trial (REGONIVO, EPOC1603). Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2020, 38, 2053–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.L.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, J.C.; Liu, H. A meta-analysis comparing regorafenib with TAS-102 for treating refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. The Journal of international medical research 2020, 48, 300060520926408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex | #patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 18 (62.07%) |

| Female | 11 (37.93%) |

| Age (years) | Median (range) |

| Male | 56.5 (31-77) |

| Female | 58.2 (40-79) |

| Race | #patients (%) |

| Caucasian | 24 (82.8%) |

| Black | 4 (13.8%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (3.4%) |

| ECOG Status | #patients (%) |

| ECOG=0 | 19 (65.5%) |

| ECOG=1 | 10 (34.5%) |

| KRAS Mutation | #patients (%) |

| positive | 16 (55.2%) |

| negative | 13 (44.8%) |

| Primary Disease Site | #patients (%) |

| Colon | 14 (48.3%) |

| Rectum | 13(44.8%) |

| Colon and Rectum | 1 (3.4%) |

| Cecum | 1 (3.4%) |

| Previous Lines of Treatment | #patients (%) |

| 2 Lines | 9 (31%) |

| 3 Lines | 11 (37.9%) |

| ≥ 4 Lines | 8 (27.6%) |

| Sites of Metastases | #patients (%) |

| Liver Only | 9 (31%) |

| Lung Only | 2 (6.9%) |

| Liver+Lung Only | 10 (34.5%) |

| Liver+Lung+Other | 3 (10.3%) |

| Liver+Other (not Lung) | 2 (6.9%) |

| Bone Only | 1 (3.4%) |

| Other Only | 2 (6.9%) |

| Severity Grade | Definitely Related | Probably Related | Possibly Related | Unlikely Related | Not Related | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (mild) | 7 | 10 | 76 | 60 | 78 | 231 |

| 2 (moderate) | 5 | 4 | 27 | 20 | 21 | 77 |

| 3 (severe) | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 20 |

| 4 (life threatening) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 (death) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).