1. Introduction

Community-Based Tourism (CBT) has emerged as both a development paradigm and a localized response to socio-ecological disruptions, particularly in climate-vulnerable regions of the Global South. In Vietnam, CBT is increasingly promoted as an alternative livelihood strategy for climate-affected and economically marginalized communities. However, the effectiveness of CBT is contingent on more than grassroots initiative—it is shaped by broader patterns of investment, infrastructure, governance, and theoretical assumptions about development.

Scholarly support for CBT often draws from sustainability and resilience discourses. Resilience theory (Holling, 1973; Folke, 2006) emphasizes socio-economic systems’ adaptive capacities—especially relevant for tourism-dependent communities facing climate migration. Brown et al. (2018) emphasizes that resilience in community-based tourism emerges from local actors’ ability to navigate social thresholds, adapt to change, and maintain livelihood sustainability amid external shocks. It highlights the importance of strategic flexibility in navigating complex socio-environmental disruptions, allowing tourism systems to adjust to uncertainty while maintaining operational continuity (Sushil, 2015). Sustainability theories, particularly Ostrom’s (2009) Social-Ecological Systems (SES) framework, emphasize the interconnectedness of ecological integrity and institutional adaptability, offering insight into how tourism can respond to migration-induced change (Lacitignola et al., 2007). These frameworks reveal how CBT can contribute to both environmental resilience and economic inclusion.

However, while resilience and sustainability approaches explain adaptive responses to disruption, they do not adequately address the systemic disparities embedded in funding distribution, policy visibility, or scholarly attention across regions. The current literature lacks a critical interrogation of why certain regions receive persistent investment and visibility while others remain marginalized—despite demonstrated need or potential.

To fill this gap, this study introduces a combined theoretical lens of spatial justice and post-development critique. Spatial justice theory (Soja, 2010; Lefebvre, 1991) provides tools for examining how geographic inequalities are produced through institutional structures and donor preferences. It exposes how tourism infrastructure, funding priorities, and even scholarly discourse are not evenly distributed, but rather concentrated in spatially “legible” regions like the Mekong Delta. In parallel, post-development theory (Escobar, 1995; Sachs, 1992) critiques the underlying logic of externally imposed development models. It asks who defines development, whose needs are prioritized, and whose knowledge systems are excluded—questions that are essential for understanding the top-down structure of CBT implementation in Vietnam.

Vietnam’s national climate strategy and external funding mechanisms have disproportionately targeted the Mekong Delta, a region with visible climate vulnerability and infrastructural readiness. In contrast, Northern ethnic minority regions—despite chronic poverty and tourism potential—remain underfunded and under-represented in both practice and scholarship. This paper addresses this gap by analysing the intersection of investment flows, regional CBT readiness, and the epistemic visibility of different Vietnamese regions in CBT research.

2. Literature Review: Spatial Justice and Post-Development Critique

2.1. Spatial Justice and Development Disparities

The concept of spatial justice has emerged as a critical framework for analysing uneven development, territorial inequality, and the politics of place. Introduced by Edward Soja (2010), spatial justice expands upon Henri Lefebvre’s earlier work on the social production of space (Lefebvre, 1991) by emphasizing how spatial configurations are not merely outcomes of economic and political processes but are integral to how power and inequality are produced and reproduced. Soja argues that justice is always spatial—that is, the distribution of resources, opportunities, and rights is inherently shaped by geography. In development contexts, spatial justice offers a means to assess how physical location and regional affiliation determine one’s access to infrastructure, services, and economic opportunities.

Lefebvre’s (1991) The Production of Space laid the theoretical foundation by asserting that space is not a neutral container but is socially constructed and imbued with ideology and power. He famously described three modes of space: perceived (spatial practices), conceived (representations of space), and lived (spaces of representation). These distinctions enable scholars to evaluate how state planning, development funding, and donor interventions create disparities in spatial access and usage.

In tourism studies, spatial justice allows for a critical interrogation of how infrastructure, policy attention, and scholarly focus disproportionately favour some regions over others. For example, in Vietnam, the Mekong Delta region has received consistent investments from multilateral development banks like the World Bank and ADB, while the Northern Highlands, home to most of the country’s ethnic minorities, have been comparatively neglected. Applying Soja’s (2010) framework to these patterns reveals how infrastructure development—while framed as a technical or logistical issue—is deeply political, reflecting systemic spatial preferences that reinforce existing inequalities. In this context, spatial injustice is not merely a question of resource scarcity but of representational erasure and institutional disregard.

Dikeç (2001) further develops the notion of “the spatial imagination,” emphasizing how ideas of justice are shaped by spatial practices and urban governance. He calls for more integrative approaches that combine social justice concerns with spatial analysis. For tourism development, this implies a need to assess how funding flows and policy frameworks prioritize spatially visible or economically strategic areas, often ignoring those that are geographically remote, ethnically diverse, or politically marginalized.

In the case of Community-Based Tourism (CBT) in Vietnam, spatial justice theory provides a powerful lens through which to assess why certain regions receive more attention and support. The dominance of CBT initiatives in the Southern and Central regions, particularly the Mekong Delta, can be interpreted not merely as a result of better readiness or climatic vulnerability, but as evidence of deeper structural preferences embedded in national and international development frameworks.

2.2. Post-Development Critique and Community Agency

While spatial justice helps explain where development happens, post-development theory interrogates the very foundations of how development is conceptualized and operationalized. Emerging in the 1990s as a critical response to mainstream development discourses, post-development scholars such as Arturo Escobar (1995) and Wolfgang Sachs (1992) argue that “development” is not a neutral or universally beneficial process. Rather, it is a discursive apparatus rooted in Western modernity, often imposed upon the Global South in ways that marginalize local knowledge systems, cultural autonomy, and alternative models of well-being.

In Encountering Development, Escobar (1995) deconstructs the history of development institutions, showing how the “Third World” was constructed through discourses of deficiency and progress. He critiques the dominance of expert-led, technocratic approaches that reduce complex social realities to quantifiable indicators and policy frameworks. This critique resonates strongly with CBT in Vietnam, where donor-led tourism projects often prioritize measurable outcomes—such as visitor numbers or infrastructure spending—over locally defined success, cultural sustainability, or empowerment.

Post-development theory offers critical insight into how CBT is frequently instrumentalized as a tool for poverty alleviation or climate adaptation, often without sufficient engagement with the communities it purports to serve. Development agencies may frame CBT as an “inclusive” solution, yet the planning, funding, and implementation processes are frequently top-down. Projects may be designed with limited local input, constrained by donor timelines and indicators. In such cases, CBT risks becoming a technocratic solution rather than a community-driven transformation.

Sachs (1992) and contributors to The Development Dictionary underscore that core development terms—such as “poverty,” “participation,” and even “sustainability”—carry ideological baggage and are often co-opted to justify interventions that reproduce dependency rather than autonomy. For CBT, this critique is particularly relevant: while it is promoted as a participatory approach, actual power over decision-making, revenue allocation, and marketing strategies often lies with external actors—government agencies, NGOs, or private sector intermediaries.

Ziai (2007) offers a nuanced analysis of post-development thinking, noting that while early versions were criticized for romanticizing localism or rejecting development altogether, more recent strands advocate for “alternatives to development” rather than an outright rejection. These alternatives emphasize autonomy, self-determination, and pluralism—values that align with the original spirit of CBT, which arose from efforts to give communities control over tourism processes and outcomes.

In the Vietnamese context, applying post-development theory entails scrutinizing how CBT is funded and represented. The dominance of the Mekong Delta in donor portfolios reflects not just climate risk but also donor preferences for visible, accessible, and “successful” projects. Meanwhile, ethnic minority regions in the Northern Highlands are rendered invisible or pathologized as backward, thus receiving funding for poverty alleviation but not tourism development. Post-development critique thus helps explain why these communities are marginalized—not because they lack potential, but because they fall outside the dominant development imaginary.

2.3. Integrative Framework for CBT in Vietnam

Combining spatial justice and post-development theory creates a robust analytical framework for examining CBT initiatives. Spatial justice foregrounds the material and representational inequalities that result from regional development priorities, while post-development critique questions the legitimacy and structure of those priorities themselves. Together, these theories allow us to move beyond a needs-based or capability-based approach and ask more fundamental questions: Who decides what counts as development? Whose knowledge is privileged? And whose spaces are seen as worth investing in?

By framing CBT through these critical lenses, this study argues that the regional disparities in Vietnam’s CBT landscape are not simply logistical challenges or outcomes of uneven readiness. Rather, they reflect deeper structural issues related to geography, ethnicity, and donor-driven planning paradigms. The underrepresentation of Northern ethnic minority areas in both funding and scholarly literature reveals a double marginalization—one that is spatial and epistemic.

2.4. Research Design

This study adopts a critical qualitative research design grounded in spatial justice theory (Soja, 2010) and post-development critique (Escobar, 1995), aiming to uncover how patterns of investment reflect structural and geographic inequalities in Community-Based Tourism (CBT) development across Vietnam. Rather than assessing CBT projects solely on the basis of effectiveness or success, this study interrogates which regions are prioritized by national and international funding actors, and how these priorities shape both practical implementation and academic representation.

Previous scholarship on CBT in Vietnam has emphasized entrepreneurship development and community participation (Khantee & Jeerapattanatorn, 2023), but tends to treat underrepresentation of certain regions—such as the Northern Highlands—as either logistical or readiness-related. This study challenges that assumption by exploring how investment decisions reflect systemic spatial biases, thereby influencing the visibility, feasibility, and scholarly attention afforded to CBT in different regions.

To identify these disparities, this study engages in a theory-informed mapping of funding flows across four regional categories (Northern Highlands, Central Vietnam, Mekong Delta/Southern, and Peri-Urban South). In doing so, it examines the role of both macro-level funders (e.g., World Bank, ADB) and micro-level institutions (e.g., IFAD) in shaping CBT infrastructure and local empowerment. This comparative framing draws on Soja’s (2010) emphasis on spatial inequality and Escobar’s (1995) critique of externally imposed development agendas.

Additionally, the design includes a secondary critical review of literature and institutional reports to assess how knowledge production mirrors investment flows. If funding is concentrated in the Mekong region, and most CBT case studies are drawn from the same area, the paper argues that this represents not only a practical imbalance but also an epistemic injustice—a selective amplification of success narratives from already privileged regions.

2.5. Research Questions

Guided by these theoretical concerns, the study poses the following questions:

- ▪

-

Main Research Question:

How do systemic issues—particularly funding structures and spatial inequality—affect the initiation, visibility, and effectiveness of Community-Based Tourism (CBT) initiatives across Vietnam?

- ▪

-

Subsidiary Questions:

In what ways does the distribution and flexibility of investment mechanisms contribute to regional disparities in CBT development, particularly the dominance of Southern Mekong areas?

How do active NGO involvement and local organizational participation influence the financial agency and tourism readiness of marginalized communities?

2.6. Data Collection

1. Search Strategy

To address these questions, the research undertook a multi-pronged data collection approach combining thematic literature synthesis, document analysis, and AI-assisted content classification.

First, a targeted literature review of peer-reviewed CBT research in Vietnam from 2016 to 2025 was conducted. Inclusion criteria focused on case studies, investment analysis, and regional assessments. Key empirical contributions (e.g., Khantee & Jeerapattanatorn, 2023; Duong, 2025) were analyzed in relation to funding patterns, community readiness, and participatory governance. Where articles lacked explicit CBT framing but addressed related issues—such as tourism infrastructure, social capital, or entrepreneurship—they were evaluated through a CBT-relevant lens.

Second, development finance documents and program reports were examined, including those from the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and the Vietnamese Ministry of Planning and Investment. Projects were assessed for their stated objectives, target regions, and scale of investment, with a focus on tourism, infrastructure, rural development, and climate resilience.

To facilitate regional comparison, projects were categorized into four geospatial zones, and investment amounts were organized by development focus (e.g., infrastructure, training, poverty alleviation). Due to the absence of consistent numeric data across regions, projects were evaluated through narrative attribution and keyword-coded summaries, with classifications supported by critical interpretation rather than simple quantification.

Lastly, the study employed Generative AI (ChatGPT-4.5) as a text-mining tool to assist in identifying patterns within grey literature and funding archives, visualize regional disparities (e.g., pie charts of investment proportions), and identify regional emphases in scholarly literature. This method was not used to generate content but to structure findings and visualize patterns for critical interpretation. AI-assisted analysis was embedded within a researcher-directed framework, grounded in human ethical review and manual verification.

2.7. Methodology: Theoretical Framing and Data Strategy

1. Tourism Resilience, Livelihoods, and Regional Disparities

A growing body of scholarship explores the capacity of tourism systems to adapt to climate-induced migration, often through frameworks such as the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (Kunjuraman, 2022) and Social-Ecological Systems Theory (Ostrom, 2009). These perspectives highlight how tourism functions both as a mechanism for resilience and a beneficiary of socio-environmental transformations. Integrating migrants’ needs into tourism development enhances inclusive livelihood strategies and strengthens ecological and economic adaptability (Mutter et al., 2023).

In the Vietnamese context, rural-to-urban migration trends—driven by both climate stress and industrialization—have reshaped peri-urban spaces such as Can Tho and Ho Chi Minh City (Garschagen et al., 2011). The state’s 2009 strategic plan for agricultural land-use and food security encouraged a structural transition from rice farming to urban industrial employment. Such transitions underscore the urgency of integrating tourism into broader livelihood diversification frameworks. Tourism initiatives must therefore be aligned with land-use policy, agricultural resilience, and internal migration dynamics.

Structured CBT programs can contribute to these goals if supported by inclusive governance, professional training, and cross-sector collaboration among government, NGOs, and community actors. However, without proper management, CBT risks undermining traditional agriculture, cultural authenticity, and community cohesion. Balanced planning is essential to ensure that CBT development complements rather than replaces local systems.

Case studies reveal these tensions: Thanh Phu district in Ben Tre Province demonstrates the integration of agritourism and climate adaptation through IFAD-supported models. Meanwhile, Can Tho’s Floating Market highlights the economic potential of CBT alongside challenges of overcrowding and environmental degradation. Sa Pa’s rapid tourism expansion illustrates risks to traditional farming communities where tourism replaces rather than supports local livelihoods (Truong et al., 2022). These examples confirm that CBT’s impact must be assessed not only in economic terms but through lenses of spatial justice, resilience, and local empowerment.

2. Regional Investment Categorization and Funding Analysis

This study evaluates national and international CBT-related investments through a regionalized analysis informed by spatial justice theory (Soja, 2010). Funding is not treated as a neutral economic input but as a spatial and institutional choice that reflects priorities, exclusions, and structural inequalities. The methodology categorizes Vietnam into four regions—Mekong Delta/Southern, Central Vietnam, Northern Highlands, and Southern Peri-urban/Urban—to assess geographic disparities in tourism investment.

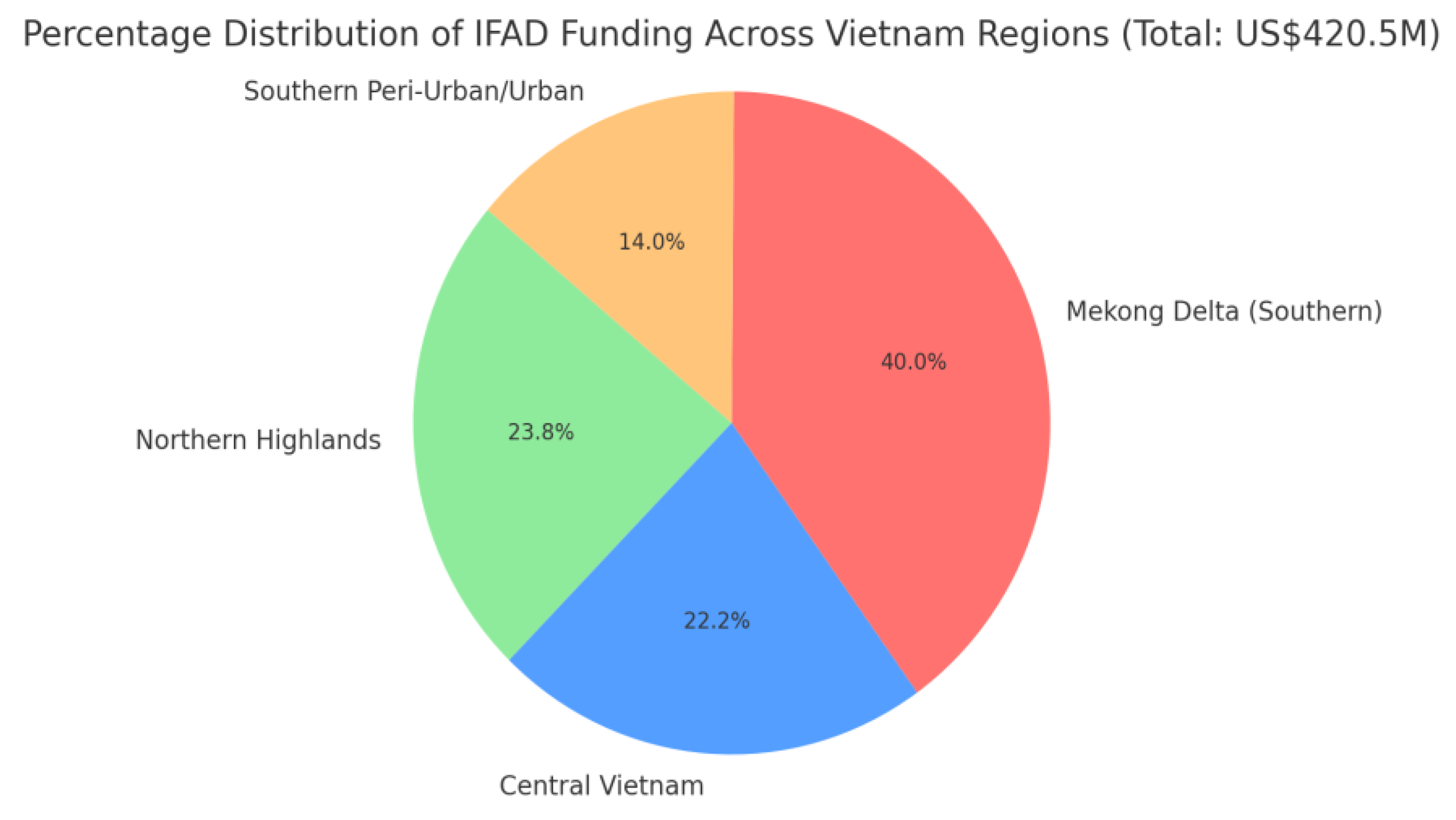

Macro-level funding sources such as the World Bank and ADB were analyzed alongside micro-level programs from IFAD. Due to the lack of standardized regional reporting, project classifications were made using descriptive objectives from evaluation documents, including those addressing poverty reduction, agroforestry, enterprise support, climate resilience, and ecotourism. IFAD has supported 17 projects in Vietnam since 2002 totaling USD 788 million. Of this, USD 420.5 million was directly invested by IFAD. Funding allocations were inferred through project locations documented in official reports (IFAD, 2023c).

The Mekong Delta region includes provinces like Ben Tre and Tra Vinh, consistently referenced in IFAD’s climate-oriented programs (e.g., DBRP, IMPP, CSAT). Central Vietnam includes provinces such as Ha Tinh, Gia Lai, and Quang Binh. The Northern Highlands include Ha Giang, Cao Bang, and Bac Kan—areas with significant ethnic minority populations targeted for poverty alleviation. Southern Peri-Urban areas, such as Ho Chi Minh City and Binh Duong, are less commonly targeted by IFAD but receive major infrastructure funding from national and multilateral sources.

Complementary to this, national funding sources were also analyzed, including Ministry of Planning and Investment allocations and national budgets. A cross-analysis of donor reports and Vietnamese government development plans allowed estimation of regional investment emphasis. Projects were categorized by region, development aim, and donor type. While exact numeric disaggregation was unavailable for some multi-regional projects, critical classification based on primary beneficiaries provided useful approximations.

AI-assisted tools (ChatGPT-4.5) were used to code regional themes, cross-reference geographic mentions in donor documents, and generate visual summaries of investment proportions. This tool supported the analytical workflow, but all interpretations and classifications were researcher-directed, with human oversight applied to ensure accuracy and ethical alignment. The use of AI here aligns with emerging standards for integrating generative technologies in qualitative research (Mahlow & Jones, 2023).

3. Results

3.1. Financial and Infrastructure Investments

From a spatial justice perspective (Soja, 2010), government investments in CBT infrastructure reflect targeted development choices that both empower and exclude. While selected provinces such as Ben Tre benefit from tourism-linked improvements, other peripheral regions remain underserved. Vietnamese government investment has focused on roads, sanitation, electricity, and community centers—especially in regions already poised for CBT rollout. For example, Thanh Phu District in Ben Tre Province received targeted funding for road and visitor center development, which catalyzed local tourism growth.

Beyond physical infrastructure, vocational training and capacity-building in culinary arts, hospitality, and tour guiding have been supported nationally to integrate vulnerable populations, including climate migrants, into tourism value chains. While this suggests inclusive intent, distribution remains spatially uneven.

International cooperation further bolsters CBT development. The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) provides targeted funding for projects, particularly in northern mountainous regions like Hoa Binh Province, emphasizing infrastructure development and specialized training aimed at empowering ethnic minority communities (JICA, 2024). Similarly, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) dedicates efforts toward climate-resilient CBT projects, especially in climate-impacted communities within the Mekong Delta, effectively combining local tourism with sustainable livelihoods (UNDP, 2023). The World Bank substantially supports tourism development and sustainable livelihood initiatives in culturally rich yet economically disadvantaged areas, incorporating comprehensive infrastructure upgrades, capacity-building, and socioeconomic integration strategies (World Bank, 2023).

Vietnam’s National Climate Change Strategy (2021-2030) significantly allocates funding for alternative livelihood models, notably Community-Based Tourism (CBT), targeting climate migrants in vulnerable areas such as the Mekong Delta and central coastal provinces. Provinces like Ben Tre, Ca Mau, and Tra Vinh received targeted funding for resettlement and livelihood transition through CBT initiatives. The Mekong Delta Integrated Climate Resilience and Sustainable Livelihoods Project, a partnership with the World Bank, exemplifies a comprehensive approach involving community-driven development, livelihood diversification, and resettlement assistance, with funding exceeding USD 310 million. Additionally, international NGOs and organizations such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM) support CBT pilot projects, with budgets ranging from USD 50,000–200,000 per location in provinces such as An Giang, Dong Thap, and Ben Tre (World Bank, 2023; UNDP, 2023). Smaller international NGOs have provided CBT pilot funding in the range of USD 50,000–200,000 in locations such as An Giang and Dong Thap. GIZ’s Coastal Protection and Climate-Resilient Infrastructure Project (2017–2025) also funds CBT-linked activities, especially where livelihoods intersect with ecological conservation. Policy integration remains strong at the national level. Resolution 08-NQ/TW (2017) names CBT as a pathway for rural economic diversification, yet implementation reflects geographic preferences. In short, tourism investment favors regions already visible in national discourse or logistically favorable for international donors.

3.2. Macro vs. Micro-Level Funding Strategies: Implications for Equity

A comparative analysis of multilateral and community-focused funding streams reveals significant disparities in scale, scope, and strategy. The World Bank and Asian Development Bank (ADB) have committed over USD 25.9 billion and USD 18 billion, respectively, to Vietnam, with large allocations toward climate-resilient infrastructure, transport, and economic integration (World Bank, 2025; VietnamPlus, 2025). These investments disproportionately target regional transportation networks and peri-urban economic corridors—such as the Mekong Delta and central coast.

In contrast, IFAD’s funding footprint is modest—USD 788 million across 17 projects since 2002, with USD 420.5 million direct investment. IFAD emphasizes small-scale, community-led projects: rural markets, homestay facilities, and livelihood training—particularly relevant for CBT readiness. While this aligns with the participatory goals of CBT, the limited financial capacity restricts broader structural change.

This funding disparity raises critical concerns. While macro-level donors support physical connectivity and economic resilience, they risk reinforcing top-down governance structures and bypassing grassroots ownership. IFAD’s localized approach promotes empowerment but lacks the financial leverage to alter spatial inequalities at scale.

Bridging this gap requires a blended investment strategy—large-scale infrastructure paired with localized community capacity-building. Importantly, spatial justice demands not only resource redistribution, but also attention to the narratives, visibility, and planning priorities afforded to regions. Peripheral provinces should not be excluded from CBT development trajectories simply because they are less “bankable.”

This divergence between investment philosophies reflects deeper structural inequalities and calls for integrated policy approaches that value both connectivity and community. Without such integration, CBT’s potential to serve climate migrants and vulnerable rural populations will remain unrealized. Table Below is a comparative description clearly illustrating the total investments by IFAD, World Bank, and ADB in Vietnam, highlighting the chronological and financial scale differences:

Table 1.

Comparative Investment Analysis (IFAD vs. World Bank & ADB) (1993-2025).

Table 1.

Comparative Investment Analysis (IFAD vs. World Bank & ADB) (1993-2025).

| Region |

Investment Focus |

Total Amount

Invested (USD)

|

| World Bank |

Large-scale infrastructure, economic integration,

climate resilience |

US $25.9 Billion |

| Asian Development Bank (ADB) |

Transport infrastructure, clean energy, vocational training, rural development, climate resilience |

US $18 Billion1

|

| IFAD |

Small-scale rural infrastructure, livelihood diversification, community-led empowerment |

US $788 Million |

3.3. IFAD’s Targeted Funding Strategy and Spatial Equity Implications

IFAD’s investment portfolio in Vietnam reflects a regionally adaptive model aligned with livelihood diversification, poverty reduction, and rural development. However, when analyzed through the lens of spatial justice (Soja, 2010), these investments also reveal persistent geographic disparities linked to long-standing marginalization—particularly in the Northern Highlands.

In Northern regions such as Ha Giang and Cao Bằng, IFAD projects like the Decentralized Programme for Rural Poverty Reduction (DPRPR), Economic Empowerment of Ethnic Minorities (3EM), and Developing Business with the Rural Poor (DBRP) target foundational infrastructure and ethnic minority inclusion. While vital, these initiatives focus on basic needs and financial literacy rather than tourism innovation or market integration. This approach, while well-intentioned, may inadvertently reinforce a dependency cycle rather than facilitate empowerment through community-based tourism (CBT).

In Central Vietnam, IFAD’s support for agroforestry and environmental resilience through projects like the 3PAD and Tam Nong Support Project (TNSP) aligns with the region’s cultural and ecological characteristics. Central Vietnam accounted for 22.2%, targeting rural development and livelihood diversification (IFAD, 2023c). The Mekong Delta, by contrast, receives more robust funding (40%, or USD 168.2 million), emphasizing climate adaptation, market access, and ecotourism (e.g., IFIA, CSAT, DBRP). This region’s strategic alignment with donor priorities reflects a strong visibility bias linked to climate urgency and perceived development return.

The pie chart in

Figure 1 and

Table 2 illustrate this distribution, where the Mekong Delta consistently leads in CBT-enabling investment. While the Northern Highlands received 23.8% of IFAD funding, this was directed toward poverty alleviation rather than tourism development. The discrepancy highlights a funding logic that favors already ‘bankable’ regions while leaving structurally marginalized areas with foundational but non-transformative support.

This regional disparity mirrors trends in tourism scholarship, suggesting that regions receiving more funding also receive greater academic attention. As such, IFAD’s otherwise decentralized approach unintentionally contributes to spatial injustice by reproducing visibility and opportunity gaps in Vietnam’s tourism development landscape.

3.4. Macro-Level Donor Investment Patterns: Centralization and Corridor Bias

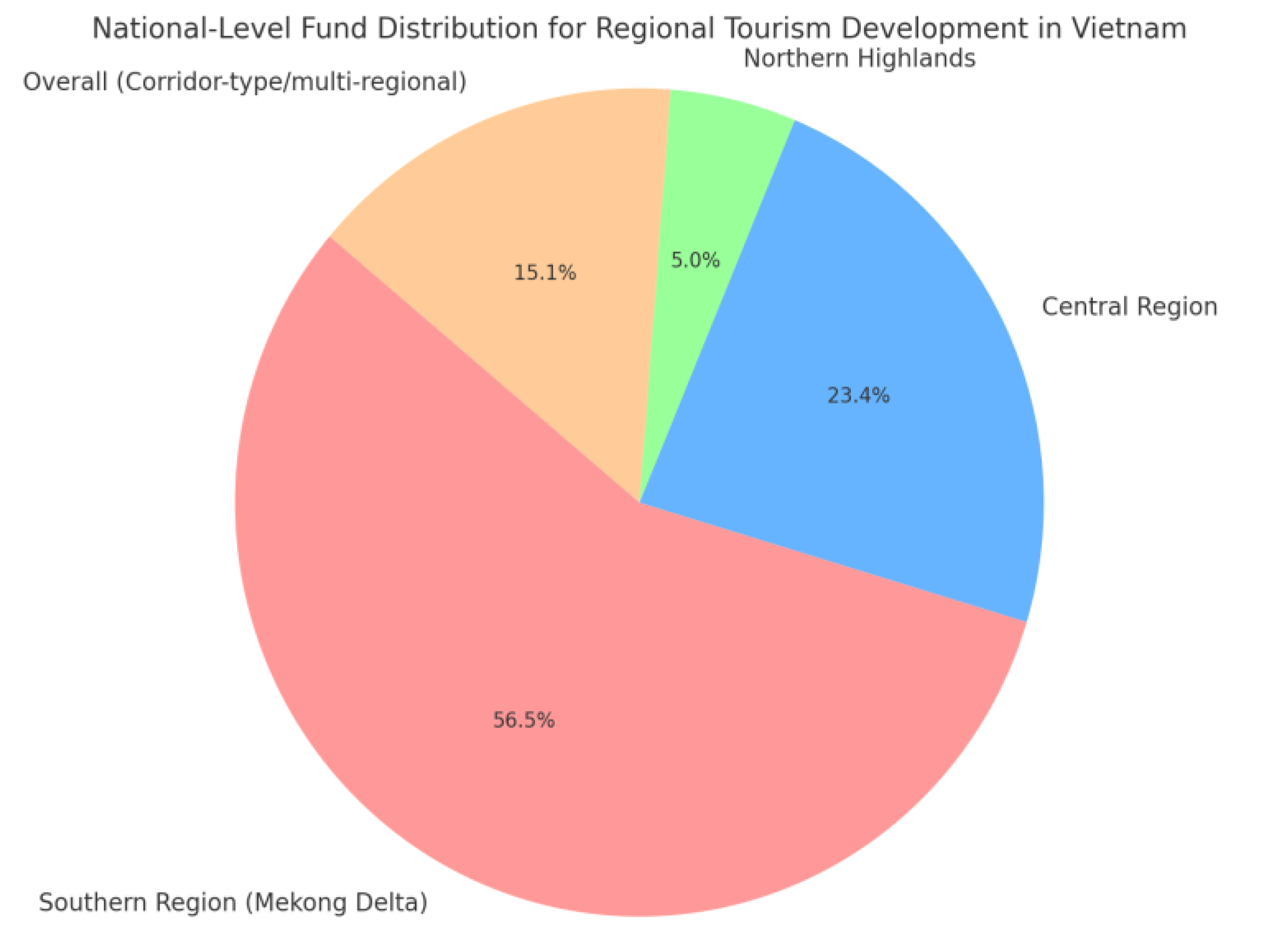

National-level funding from the World Bank and ADB exhibits a strong spatial concentration toward Vietnam’s Southern and Central regions, particularly the Mekong Delta. Projects such as the Mekong Delta Integrated Climate Resilience and Sustainable Livelihoods Project (USD 310 million) and the Mekong Resilient Regional Connectivity Project (USD 250 million) reflect major international commitments to climate-resilient infrastructure and economic integration.

These macro-level investments prioritize inter-provincial highways, flood defenses, and urban resilience—especially in high-density areas like Can Tho and Ben Tre. Similarly, ADB initiatives like the Climate Resilient Inclusive Infrastructure for Ethnic Minorities Project II (USD 72 million) and the Australia-ADB co-funded Central Mekong Delta Connectivity Project (USD 160 million) enhance regional infrastructure and connectivity. This initiative directly addresses infrastructure deficits among ethnic minority communities in provinces like Phú Yên and Quảng Trị (VietnamPlus, 2023). However, these projects favor logistic centrality and measurable economic outputs (ADB, 2023).

In contrast, the Northern Highlands—home to some of Vietnam’s most vulnerable ethnic minority communities—receive minimal and poorly documented support. Project data for provinces such as Hà Giang and Điện Biên are sparse, often embedded within corridor-style programs that blur geographic attribution (ADB, 2023; World Bank, 2020). This lack of visibility reflects what Escobar (1995) calls the erasure of peripheral voices in dominant development narratives.

The funding breakdown in

Table 3 and

Figure 2 confirms these spatial imbalances. The Mekong Delta receives 56.5% (USD 560 million) of total funding, while the Northern Highlands receive only 5% (USD 50 million). Despite national commitments to inclusive development, the opacity and concentration of macro-level donor strategies reveal an underlying centralization bias.

Thus, even as these projects contribute to national infrastructure goals, they risk reproducing territorial inequality by neglecting regions with lower administrative capacity or political visibility. Bridging this equity gap requires greater transparency in allocation processes and a stronger commitment to inclusive planning frameworks that center spatial justice as a core development principle.

3.5. Regional Development Barriers and Spatial Disparities in CBT Readiness

Drawing from Khantee and Jeerapattanatorn’s (2023) analysis and situated within the framework of spatial justice and CBT readiness, this section categorizes tourism development challenges across three major Vietnamese regions. These disparities not only shape the practical implementation of CBT but reflect deeper institutional biases in how ‘readiness’ is defined and addressed by donors. The categorization is based on a critical review of 25 studies focusing on entrepreneurship development, infrastructure access, cultural alignment, and regional policy gaps.

In the Northern region, the main entrepreneurship development challenges include limited community involvement, low financial literacy, inadequate access to bank credit, minimal tourism infrastructure, environmental issues (such as freshwater scarcity), and negative perceptions of informal activities like street vending. These issues contribute to weak tourism capacity and low CBT readiness, making the region less attractive for investment or research attention (Duong et al., 2023; Mai et al., 2014; Luan et al., 2023; Phan et al., 2021; Hoang et al., 2018; Huong & Lee, 2017; Truong, 2017). This pattern suggests a recurring treatment of the region as a passive recipient of aid, rather than an active tourism actor, echoing Escobar’s (1995) critique of top-down development paradigms.

In Central Vietnam, challenges are more closely linked to socio-cultural misalignments and entrepreneurial deficiencies. These include cultural misunderstandings between hosts and tourists, low technical skills, weak heritage promotion, and competition with industrial sectors. Environmental degradation and lack of sustainable development planning are also common. These overlapping pressures hinder entrepreneurship growth and sustainable CBT implementation (Nguyen et al., 2023; Phu & Thi Thu, 2022; Quang et al., 2022; Hong et al., 2021; Ngo et al., 2019; Trinh & Ryan, 2015; Ngo et al., 2018; Cong & Thu, 2020; Conga & Chip, 2020; Truong, 2019; Suntikul et al., 2016).

In the Southern region, especially the Mekong Delta and peri-urban zones, key challenges include ineffective marketing, gender-related burdens on women entrepreneurs, limited product diversification, and weak regional cooperation. Socioeconomic stressors such as increased living costs, pollution, and social issues (e.g., drug abuse, prostitution) compound these difficulties. Additionally, COVID-19-related income losses from international tourism exacerbate these existing vulnerabilities (Quyen & Tuan, 2022; Quang et al., 2023; Huong et al., 2020; Pham, 2020; Nguyen et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2021). While infrastructure in this region is stronger, unequal benefit distribution and social risks complicate sustainability outcomes.

The provided

Table 4. aligns common regional challenges with specific interventions from IFAD’s 17 projects across various regions of Vietnam. At the national level, all regions face common issues such as limited entrepreneurship skills and inadequate infrastructure, addressed through IFAD’s investments in entrepreneurship support, rural enterprise development, and basic infrastructure.

Table 4.

Comparison of Regional Needs and IFAD’s Common Projects.

Table 4.

Comparison of Regional Needs and IFAD’s Common Projects.

| Regional Needs (Common Problems) |

IFAD’s Common Project Investments |

| Limited entrepreneurship skills and inadequate infrastructure across all regions |

Entrepreneurship support, rural enterprise development, basic infrastructure investment (IMPP, DBRP, DPRPR) |

Table 5.

Comparison of Region-Specific Needs and IFAD’s Specified Projects.

Table 5.

Comparison of Region-Specific Needs and IFAD’s Specified Projects.

| Region |

Region-Specific Needs |

IFAD’s Region-Specific Investments |

| Northern Highlands |

Freshwater shortage, financial literacy gaps, minority empowerment, negative perceptions of local tourism activities (street vending) |

Infrastructure enhancement, ethnic minority empowerment, market integration, rural enterprise support (DPRPR, 3EM, DBRP) |

| Central Vietnam |

Cultural misunderstandings, insufficient promotion of cultural heritage, inadequate facilities, environmental sustainability concerns, agro-economic competition |

Agro-forestry development, sustainable agricultural practices, poverty alleviation for ethnic minorities (3PAD, TNSP) |

| Mekong Delta & Southern Peri-Urban |

Gender-based pressures, ineffective marketing, socio-economic challenges (pollution, increased living costs, social issues), vulnerability to climate impacts |

Market access enhancement, rural enterprise and eco-tourism development, climate adaptation and mangrove-based innovations (IMPP, DBRP, IFIA, CSAT) |

Although IFAD’s regionally tailored strategies indicate awareness of local variation, actual implementation still varies by region in scope and ambition. In the North, foundational poverty alleviation dominates. In the South, more advanced climate-linked tourism models are deployed. This reinforces the earlier argument that development strategies respond not only to need, but also to institutional perceptions of implementability and return on investment. Spatial justice thus requires a deeper restructuring of both how CBT readiness is evaluated and how regional interventions are designed.

4. Discussion

This study reveals that despite the increasing recognition of CBT’s potential in national and donor-led development agendas, its implementation across Vietnam remains uneven and structurally constrained. The Mekong Delta continues to dominate tourism investment narratives—not only due to climatic vulnerability but also because of its logistical legibility, urban proximity, and long-standing donor engagement. This spatial preference reflects Soja’s (2010) concept of spatial injustice, where development resources are disproportionately allocated to already visible and administratively favored regions.

The comparative analysis of IFAD, World Bank, and ADB investments underscores an enduring ‘development bifurcation.’ While macro-level institutions prioritize corridor-based, large-scale infrastructure, IFAD’s micro-level investments are more community-oriented yet limited in scope—particularly in ethnic minority areas where infrastructural and administrative deficits inhibit scalable outcomes. These two tracks—top-down modernization and bottom-up empowerment—rarely converge in practice, leading to parallel but non-intersecting development models.

Epistemically, this investment imbalance translates into representational marginalization. As Bebbington (2000) describes, peripheral communities are often excluded from scholarly visibility due to their limited participation in high-profile, donor-supported initiatives. Thus, CBT-related scholarship reinforces rather than disrupts regional inequalities in Vietnam’s development geography.

NGO involvement in CBT remains constrained by bureaucratic complexity, regulatory sensitivities, and limited integration with national tourism strategies. Despite rhetorical commitments to participation, grassroots tourism models lack the institutional support necessary to expand beyond localized pilots.

4.1. Rethinking CBT Empowerment through IFAD’s Model: Progress and Pitfalls

IFAD’s initiatives in Vietnam illustrate both innovation and constraint. In provinces like Ben Tre and Tra Vinh, programs such as the IMPP, DBRP, IFIA, and CSAT have successfully integrated climate-smart agriculture, eco-aquaculture, and local infrastructure into CBT-readiness frameworks. These interventions foster diversified livelihoods and strengthen community-level governance, aligning with principles of decentralization and resilience.

However, these cases remain exceptions rather than norms. Many IFAD-supported projects outside the Mekong Delta—including those in the Northern Highlands and Central regions—focus on basic rural infrastructure and poverty reduction without tourism-specific components. This limits their long-term impact on CBT and fails to leverage the cultural richness and ecological diversity of these underrepresented areas.

Moreover, CBT-focused projects, even where implemented, often face significant administrative bottlenecks. Approval procedures are lengthy, documentation requirements are burdensome, and cross-sector coordination is weak. These structural constraints limit replication and scalability.

Comparatively, while IFAD’s empowerment-driven model fosters inclusion, it lacks the funding power and visibility of macro-donors like the World Bank and ADB. The latter institutions prioritize infrastructure integration, economic corridors, and large-scale impact metrics, often bypassing local agency in the name of efficiency.

For CBT to fulfill its transformative potential, policy actors must bridge this divide. A blended strategy—combining macro-level infrastructure with micro-level participatory planning—is essential. This requires not only redistributive investment mechanisms but also a fundamental shift in how CBT readiness is defined. Empowerment must go beyond access to include narrative control, resource ownership, and institutional inclusion. Only then can CBT evolve from a tourism strategy into a pathway toward structural justice.

4.2. Spatial Disparities in CBT Access and Implementation

The availability of CBT infrastructure across Vietnamese regions reflects not only differences in economic and administrative capacity but also deeper donor-driven spatial preferences. The contrast between the Mekong Delta and Northern Highland regions illustrates entrenched development asymmetries rooted in spatial justice dynamics (Soja, 2010).

The Mekong Delta Integrated Climate Resilience and Sustainable Livelihoods Project (MD-ICRSL) exemplifies this prioritization. Funded primarily by the World Bank and implemented between 2016 and 2022, the project allocated over USD 310 million to climate-resilient infrastructure and community-driven planning. While not exclusively aimed at CBT, its investments in transport, water management, and livelihoods indirectly enhanced tourism potential in nine southern provinces, particularly Ben Tre and Tra Vinh. Complementary initiatives by IOM, GIZ, and IFAD further reinforced the region’s readiness. With targeted budgets and programmatic support, the Mekong Delta now hosts a relatively vibrant CBT ecosystem. Projects like the Cái Răng Floating Market and Ben Tre agritourism initiatives underscore the synergy between climate adaptation and tourism innovation.

In contrast, Northern Highland provinces such as Dien Bien, Cao Bang, and Ha Giang—despite cultural richness and tourism potential—continue to face structural limitations. IFAD programs in these areas remain focused on poverty alleviation and basic infrastructure without integrated CBT components (Ho and Nguyen, 2025). Transportation deficits, limited amenities, and bureaucratic centralization hinder tourism development and stakeholder participation. This stark divide in CBT availability highlights the importance of reevaluating investment logic. If funding follows infrastructure readiness and economic viability, rather than poverty severity or potential, then CBT risks becoming reproduced along already privileged spatial and institutional lines.

4.3. Epistemic Visibility and Development Narratives

Development funding shapes more than material infrastructure—it also defines which regions receive representational attention in academic and policy discourse. As Bebbington (2000) argues, epistemic marginalization occurs when the voices and realities of peripheral communities are excluded from dominant development narratives.

Between 2020 and 2025, literature on CBT in Vietnam disproportionately features Southern provinces, particularly Ben Tre and Can Tho. These regions are not only recipients of IFAD and World Bank funding but also strategically visible and logistically accessible. Consequently, they dominate tourism success stories and research agendas.

The Cái Răng Floating Market, designated as a national intangible cultural heritage site, exemplifies how infrastructural accessibility and policy alignment contribute to scholarly focus. Nguyen Thi Huynh Phuong’s 2017 study highlighted both the promise and limitations of this model—exposing persistent infrastructure gaps, coordination challenges, and narrow local participation.

Such patterns suggest a self-reinforcing feedback loop: well-funded areas attract more researchers, which in turn legitimizes continued investment. Meanwhile, underfunded regions—especially in the north—are deemed academically invisible, despite their socioeconomic urgency. Further empirical research is needed to unpack how funding distribution shapes the geographies of tourism knowledge and to develop more equitable research frameworks.

4.4. Ethnicity, Poverty, and Structural Exclusion

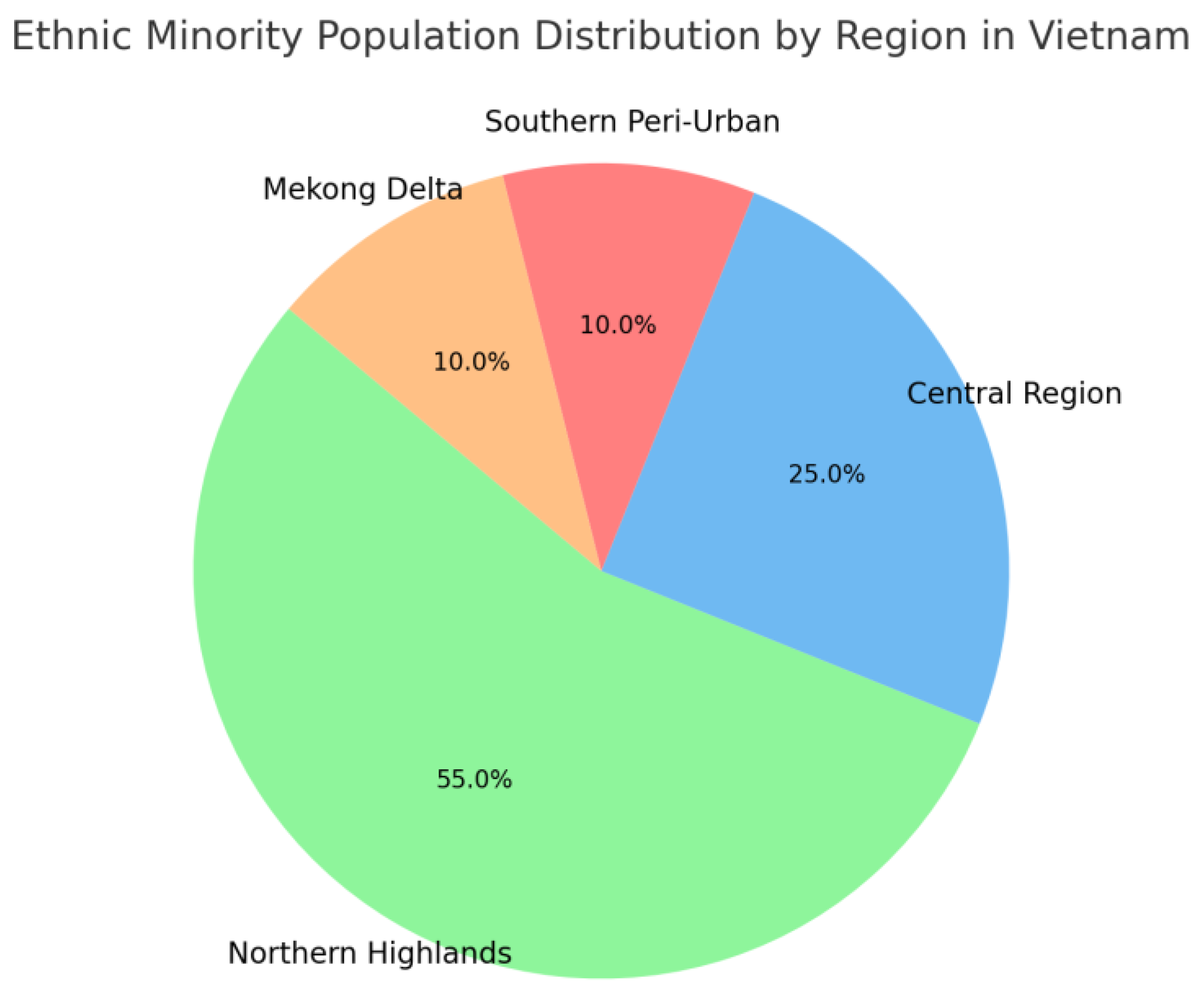

Vietnam’s ethnic composition adds another layer of complexity to spatial tourism development. Of the 54 officially recognized ethnic groups, minority populations—who comprise around 14.7% of the national population—are overwhelmingly concentrated in the Northern Highlands and Central regions (World Bank, 2022; Michaud, 2016). These areas face compounded disadvantages: limited infrastructure, weaker administrative representation, and chronic poverty rates reaching 18% or higher.

By contrast, Southern provinces such as Ben Tre and Tra Vinh, which are predominantly inhabited by the Kinh majority, benefit from more favorable infrastructure, targeted tourism investments, and policy visibility. This disparity is not merely statistical; it reflects a deeper legacy of structural exclusion stemming from colonial administration, post-war centralization, and donor spatial bias (McElwee, 2004).

While CBT is promoted as a tool for poverty alleviation and cultural preservation, its current implementation does little to redress these historical imbalances. Northern communities remain peripheral in both development plans and tourism narratives. The ‘last mile’ challenge of poverty alleviation in these regions underscores the necessity for tailored structural interventions that go beyond infrastructure provision to address root causes of exclusion—especially those faced by ethnic minority groups.

Unless CBT strategies explicitly confront ethnic and spatial marginalization, they risk reinforcing the very inequities they aspire to mitigate.

Figure 3.

Ethnic Minority Population Distribution by Region in Vietnam.

Figure 3.

Ethnic Minority Population Distribution by Region in Vietnam.

4.5. Why can NGOs in Vietnam more Engaging in CBT?

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Vietnam often refrain from actively engaging in community-based tourism (CBT) for several structural, political, and philosophical reasons. First, many Vietnamese NGOs (often referred to as “VNGOs”) operate with close ties to the government and are frequently donor-dependent and urban-based. This limited autonomy restricts their ability to enter sectors perceived as politically sensitive or commercially driven, such as tourism (Chi Thai, 2017). Tourism, particularly CBT, may also be viewed as economically and politically sensitive, thus receiving greater scrutiny than sectors like education or health, which are easier to negotiate (Mekong Plus, 2023).

Moreover, traditional development paradigms among NGOs emphasize agriculture, education, and basic services rather than economic diversification. Tourism is sometimes seen as misaligned with core poverty alleviation values, leading NGOs to perceive it as less legitimate within the development framework (Scheyven, 2007).

If community-based initiatives remain inactive, it is essential to identify the underlying factors. However, a lack of motivation or insufficient training does not appear to be the primary constraint, as training for community-based tourism (CBT) is typically funded or subsidized by governmental and non-governmental sources. Hospitality, homestay management, and tour-guiding programs are often provided free of charge or at subsidized rates by NGOs, provincial governments, or international development agencies (World Bank, 2020). For instance, the Farmer Field School (FFS) model—widely implemented throughout Asia, including Vietnam—offers comprehensive training in sustainable agriculture at minimal or no cost to participants (FAO, 2021). Similarly, institutions such as the Mekong Delta Development Institute (MDI) at Can Tho University provide government- and NGO-supported courses in rural development, rice farming, and livelihood diversification (MDI, 2022).

Exemplarily, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) has actively collaborated with local NGOs and community-based organizations (CBOs) to foster community engagement, participatory planning, and local ownership. NGOs have contributed essential services, including capacity-building, technical assistance, and market linkage support, directly responding to the specific needs of rural poor and marginalized populations. Local stakeholders—such as farmers’ cooperatives, women’s associations, and village-level committees—have played pivotal roles in the decision-making process, ensuring that interventions remain culturally relevant and community-driven. Despite top-down policy challenges, several NGOs have successfully engaged in CBT in Vietnam:

1. Action on Poverty (AoP) partnered with ethnic minority communities in Da Bac, Hoa Binh Province, to develop a CBT model based on homestays and cultural tourism. This initiative provided capacity-building, micro-loans, and mentorship for local entrepreneurs and has been cited as a model for sustainable, locally-driven CBT (Intrepid Travel, n.d.).

2. Streets International, a U.S.-based NGO operating in Hội An, provides vocational training in hospitality and culinary arts for disadvantaged youth, linking social empowerment directly with tourism infrastructure. Though not a CBT project per se, its integration into the tourism economy creates pathways for marginalized youth to benefit from tourism growth (Streets International, n.d.).

3. The IMPP Project (Improving Market Participation of the Poor), co-implemented by IFAD in Ha Tinh and Tra Vinh provinces, emphasized collaboration with local cooperatives and CBOs rather than named NGOs, but illustrates how international organizations can promote tourism-adjacent development through community involvement (IFAD, 2012). These examples demonstrate that NGO engagement in tourism is possible, particularly when supported by international development frameworks and when CBT is positioned as a tool for inclusive economic development rather than commercial tourism alone.

Effective Outcomes of the Collaboration-IMPP Exemplary case

The “Improving Market Participation of the Poor (IMPP)” project in Ha Tinh and Tra Vinh provinces exemplified this approach through collaboration between IFAD, provincial government agencies, and local actors. According to the IFAD Country Programme Evaluation Report (2012), while explicit references to named NGOs were limited, the project emphasized coordination with: Provincial People’s Committees (PPCs) of Ha Tinh and Tra Vinh, District and Commune People’s Committees, and Local farmers’ cooperatives and CBOs.

This multi-stakeholder collaboration significantly improved market participation among smallholder farmers, resulting in increased household income and enhanced economic resilience. The partnership model strengthened local governance and accountability mechanisms, empowering community members through skills training, entrepreneurship development, and integration into sustainable markets. The active involvement of NGOs and local actors further enhanced project sustainability by ensuring continued community ownership beyond the project lifecycle.

4.6. NGO Engagement and Institutional Constraints in CBT Development

The cautious involvement of NGOs in community-based tourism (CBT) in Vietnam reflects structural, political, and philosophical constraints. Vietnamese NGOs (VNGOs), often operating with close ties to the government, are typically urban-based and donor-dependent. This limited autonomy restricts their engagement in politically or commercially sensitive sectors such as tourism (Chi Thai, 2017). Tourism development—especially CBT—can be perceived as infringing on state narratives, resource control, and symbolic capital, thereby requiring higher bureaucratic clearance than sectors like education or health (Mekong Plus, 2023).

Traditional NGO mandates have also historically centered on agriculture, education, and healthcare rather than economic diversification. Within these paradigms, tourism is often viewed as less aligned with poverty alleviation goals (Scheyven, 2007). Yet, this perception is gradually shifting with the recognition that CBT, when properly framed, can integrate social empowerment, climate resilience, and inclusive economic development.

Training access is not the primary barrier to NGO participation. Initiatives like Farmer Field Schools (FAO, 2021), provincial tour guide training, and rural development programs run by institutions like the Mekong Delta Development Institute (MDI, 2022) indicate widespread knowledge access. The more significant constraint lies in navigating state authorization, inter-agency coordination, and funding legitimacy.

Nevertheless, successful examples exist. Action on Poverty’s homestay model in Da Bac, Hoa Binh Province, and Streets International’s vocational program in Hội An demonstrate how NGOs can contribute to tourism ecosystems. IFAD’s IMPP project in Ha Tinh and Tra Vinh further exemplifies how coordinated engagement with CBOs and local cooperatives facilitates tourism-adjacent development without direct NGO labeling.

These cases suggest that NGO engagement is feasible—particularly when CBT is positioned as a tool for equity, resilience, and community empowerment. However, expansion requires clearer institutional roles, formal policy endorsement, and trust-building between state agencies and grassroots actors.

4.7. Strategic Pathways for Inclusive Knowledge and Policy

Recent evaluations by IFAD’s Independent Office of Evaluation (IOE) reveal meaningful reforms in its knowledge management (KM) systems since 2016. Key enhancements include stronger departmental coherence, improved monitoring frameworks, and the integration of value-chain thinking into project design (IFAD, 2023a; IFAD, 2023b). These developments promise greater accountability and field-level responsiveness.

However, KM reform must also reckon with the representational asymmetries built into development architectures. For CBT to effectively serve ethnic minority populations, KM systems must go beyond performance metrics to integrate indigenous knowledge, localized decision-making, and cultural livelihood systems. This requires reframing CBT not as a donor-mandated product but as a platform for community-led storytelling, heritage preservation, and adaptive livelihood design—particularly in ethnic minority regions where structural exclusions remain persistent (Baulch et al., 2002).

Ultimately, inclusive tourism planning in Vietnam demands epistemic pluralism and structural flexibility—features that are still emerging within donor and state institutions. The path forward lies in leveraging KM not only for reporting but for reflexive governance, ensuring CBT development reflects the full cultural and geographic diversity of Vietnam’s rural communities.