Submitted:

12 August 2025

Posted:

13 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

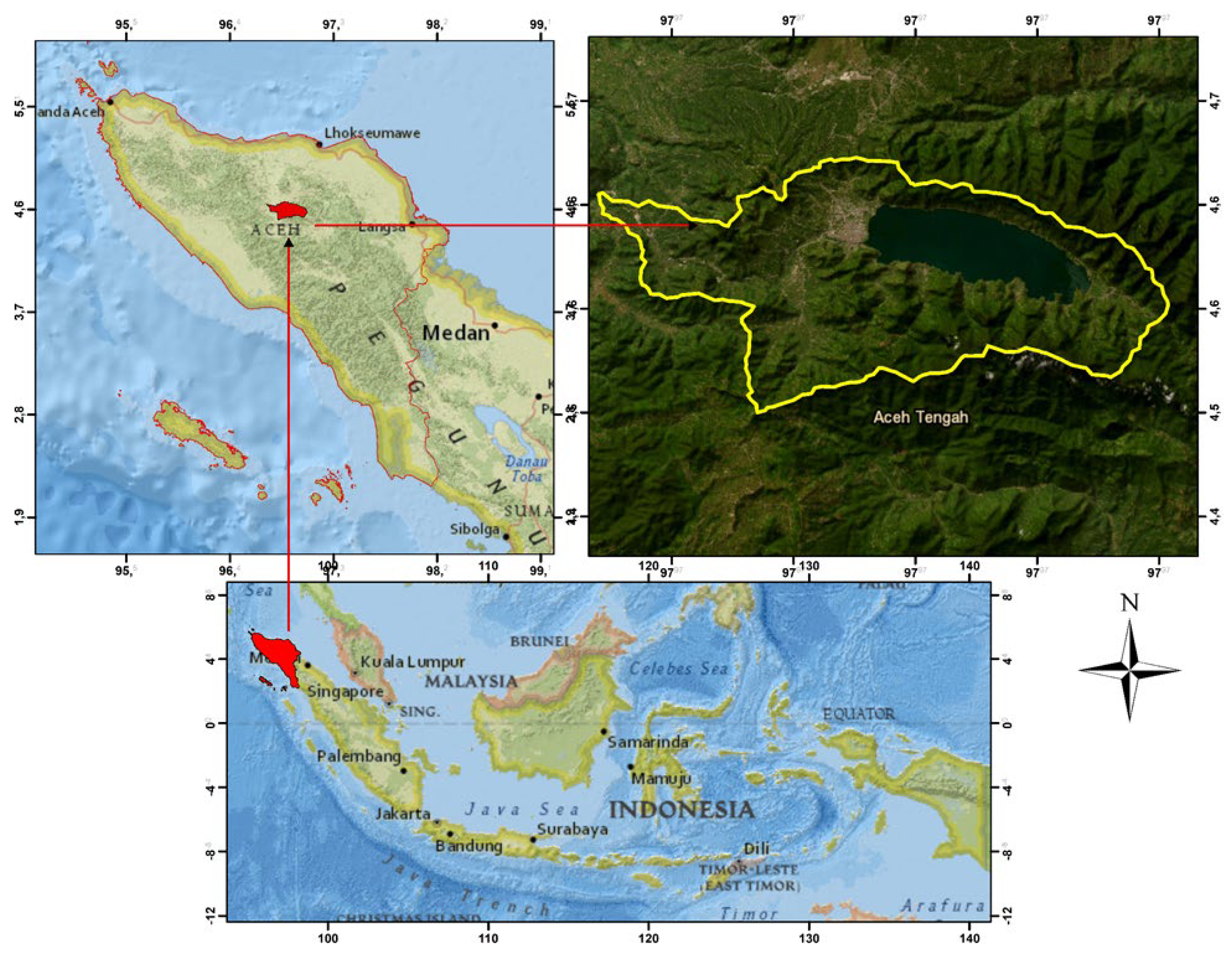

2.1. Research Location

2.1. Source of Data

2.2.1. Data Characteristics

- Operational Land Imager 2 (OLI-2) – The OLI-2 captures images for the visible, near-infrared, and shortwave infrared ranges, and is used for vegetation studies, water quality tests and land monitoring.

- Thermal Infrared Sensor 2 (TIRS-2) – This sensor receives thermal emissions data which are used to report LST, heat anomalies and urban heat island effects.

2.2.1. Data Processing and Analysis

2.1. LST Retrieval

3. Results

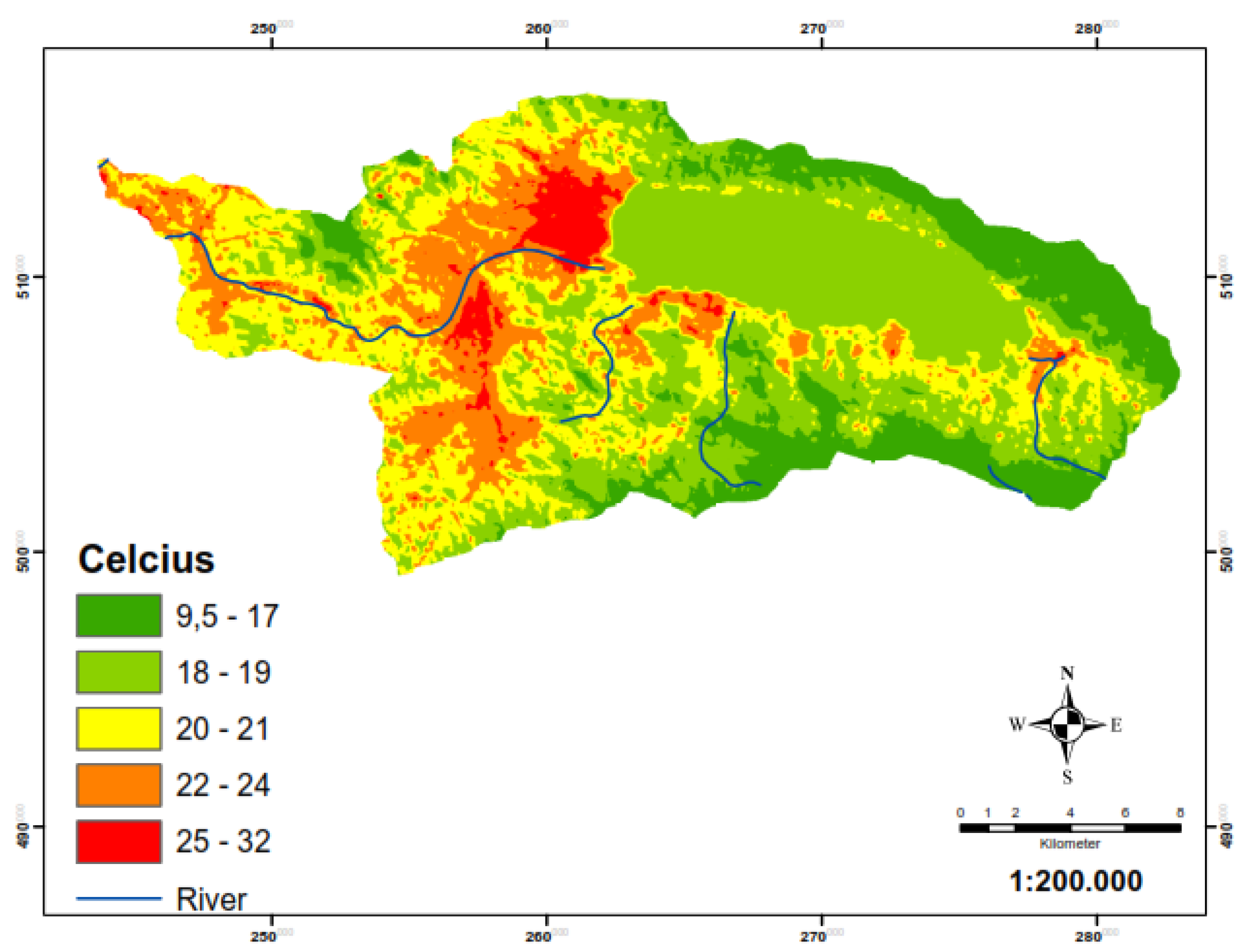

3.1. LST Distribution in the Laut Tawar Sub Watershed

3.1. Spatial Patterns of Land Surface Temperature and Factors That Influence It

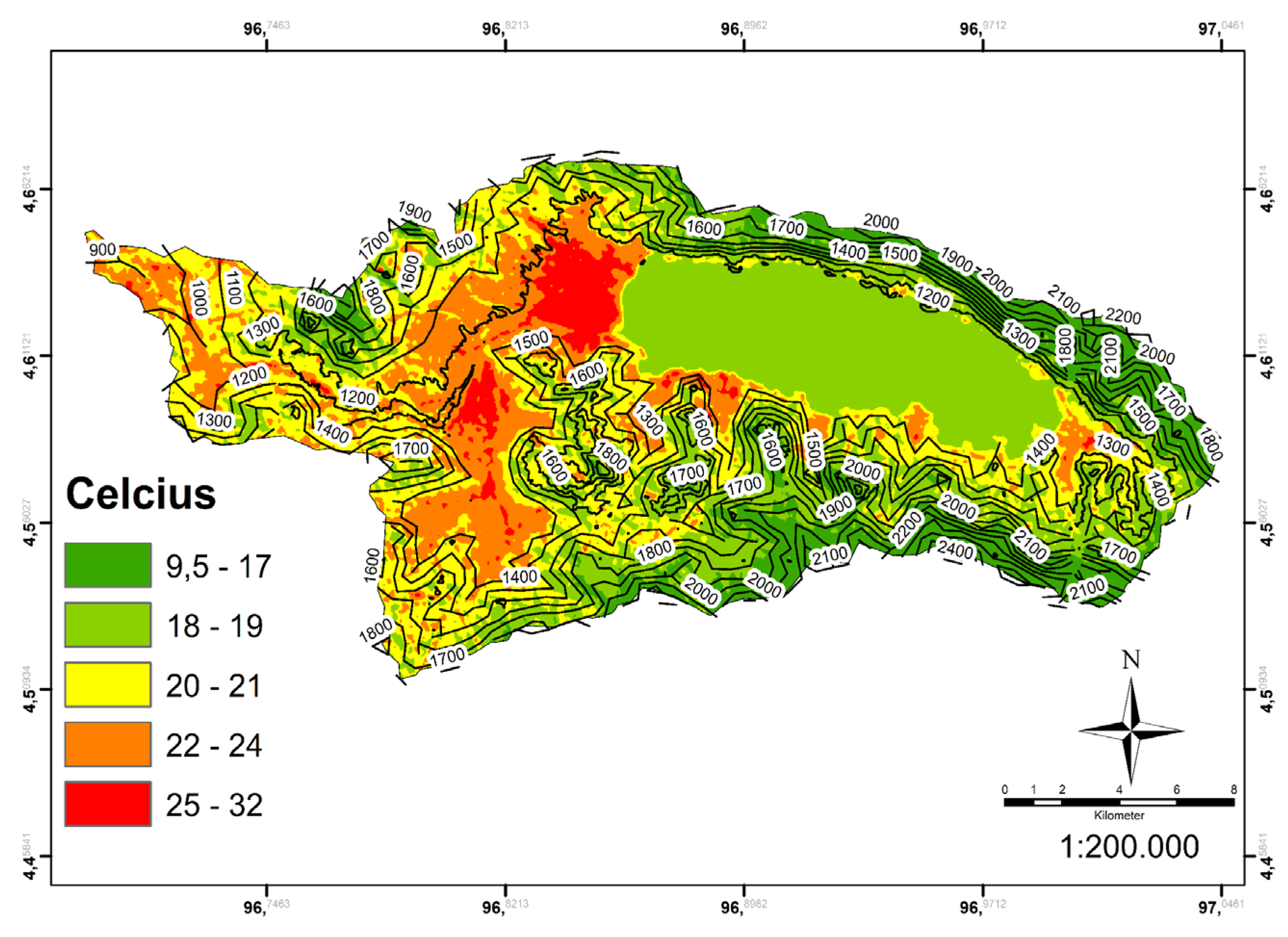

3.2.1. Tofography

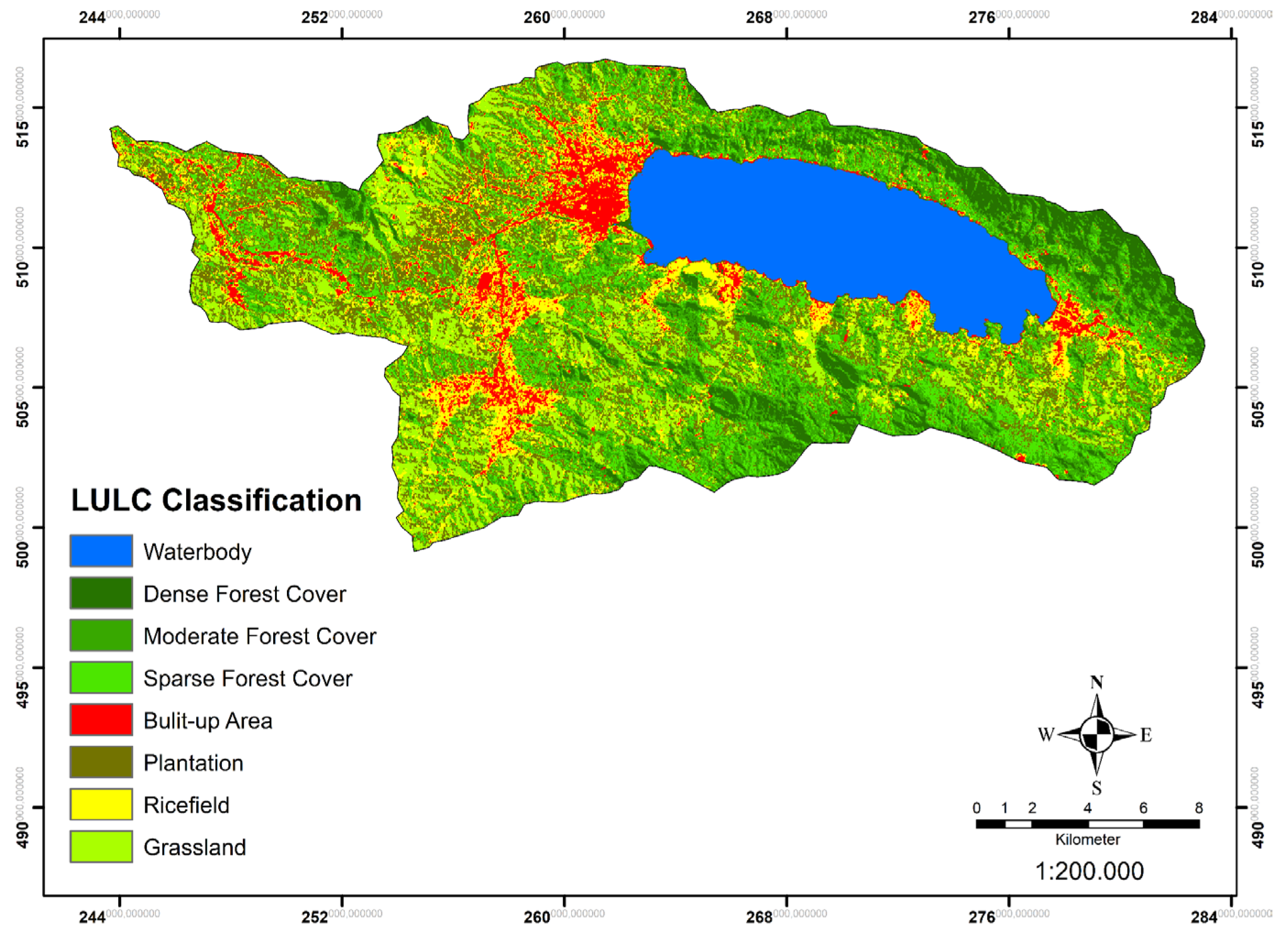

3.2.1. LULC

4. Discussion

4.1. LST Distribution Patterns

4.2. Topography and LST Variations

4.3. LULC and LST Distribution

4.4. Landsat-9 Data in LST Measurement

4.5. Implications for Spatial Management and Climate Adaptation

5. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| LST | land surface temperature |

| LULC | land use and land cover |

| UHI | urban heat island |

References

- Pongratz, J.; Schwingshackl, C.; Bultan, S.; Obermeier, W.; Havermann, F.; Guo, S. Land Use Effects on Climate: Current State, Recent Progress, and Emerging Topics. Curr Clim Chang Reports 2021, 7, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmad, A.; Fadhly, N.; Deli, A.; Ramli, I. Urban growth and its impact on land surface temperature in an industrial city in Aceh, Indonesia. Lett Spat Resour Sci 2022, 15, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara Y, Yavuz V (2025) Urban Microclimates in a Warming World: Land Surface Temperature (LST) Trends Across Ten Major Cities on Seven Continents. Urban Sci. [CrossRef]

- Ghasempour, F.; Sekertekin, A.; Kutoglu, S.H. How Landsat 9 Is Superior To Landsat 8: Comparative Assessment of Land Use Land Cover Classification and Land Surface Temperature. ISPRS Ann Photogramm Remote Sens Spat Inf Sci 2023, 10, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye X, Liu R, Hui J, Zhu J (2023) Land Surface Temperature Estimation from Landsat-9 Thermal Infrared Data Using Ensemble Learning Method Considering the Physical Radiance Transfer Process. Land. [CrossRef]

- Adhar, S.; Barus, T.A.; Nababan, E.S.N.; Wahyuningsih, H. Trophic state index and spatio-temporal analysis of trophic parameters of Laut Tawar Lake, Aceh, Indonesia. AACL Bioflux 2023, 16, 342–355. [Google Scholar]

- Ramli I, Murthada S, Nasution Z, Achmad A (2019) Hydrograph separation method and baseflow separation using Chapman Method - A case study in Peusangan Watershed. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. [CrossRef]

- Solanky V, Singh S, Katiyar SK (2018) Land Surface Temperature Estimation Using Remote Sensing Data. 343–351. [CrossRef]

- Ramli, I.; Achmad, A.; Anhar, A. Temporal changes in Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) and local climate in the Krueng Peusangan Watershed (KPW) area, Aceh, Indonesia. Bull Geogr Socio-economic Ser 2023, 59, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halefom A, He Y, Nemoto T, Feng L, Li R, Raghavan V, Jing G, Song X, Duan Z (2024) The Impact of Urbanization-Induced Land Use Change on Land Surface Temperature. Remote Sens. [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G.B. Forests and climate change: Forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science (80- ) 2008, 320, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Bi, Y.; Li, Z.A.; Xia, J. Generalized split-window algorithm for estimate of land surface temperature from Chinese geostationary FengYun meteorological satellite (FY-2C) data. Sensors 2008, 8, 933–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiyanto, D.W.; Setianto, A.; Harijoko, A. Spatial Analysis to Determine the Geothermal Potential Index: The Case Study of Dieng Geothermal Complex. J Geosains dan Remote Sens 2024, 5, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin A, Ali A, Ahmed N (2024) Time-series analysis of Leaf Area Index and Land Surface Temperature Association using Sentinel-2 and Landsat OLI data. Environ Syst Res. [CrossRef]

- Cuce PM, Cuce E, Santamouris M (2025) Towards Sustainable and Climate-Resilient Cities: Mitigating Urban Heat Islands Through Green Infrastructure. Sustain. [CrossRef]

- Nurlina; Kadir, S.; Kurnain, A.; Ilham, W.; Ridwan, I. Impact of Land Cover Changing on Wetland Surface Temperature Based on Multitemporal Remote Sensing Data. Polish J Environ Stud 2023, 32, 2281–2291. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.K. Geospatial and Statistical Analysis of Land Surface Temperature and Land Surface Characteristics of Jaipur and Ahmedabad Cities of India. J Geosci Environ Prot 2024, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocur-Bera, K.; Małek, A. Assessing the Feasibility of Using Remote Sensing Data and Vegetation Indices in the Estimation of Land Subject to Consolidation. Sensors 2024, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achmad, A.; Sari, L.H.; Ramli, I. A study of urban heat island of Banda Aceh City, Indonesia based on land use/cover changes and land surface temperature. Aceh Int J Sci Technol 2019, 8, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, A.A.; Shedge, D.K.; Mane, P.B. Exploring the Effects of Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Modifications and Land Surface Temperature (LST) in Pune, Maharashtra with Anticipated LULC for 2030. Int J Geoinformatics 2024, 20, 42–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov A, De Hertog S, Havermann F, et al (2023) Changes in Land Cover and Management Affect Heat Stress and Labor Capacity. Earth’s Futur. [CrossRef]

- Gao Y, Li N, Gao M, Hao M, Liu X (2024) Modelling Future Land Surface Temperature: A Comparative Analysis between Parametric and Non-Parametric Methods. Sustain. [CrossRef]

- Maheng, D.; Pathirana, A.; Bhattacharya, B.; Zevenbergen, C.; Lauwaet, D.; Siswanto, S.; Suwondo, A. Impact of land use land cover changes on urban temperature in Jakarta: insights from an urban boundary layer climate model. Front Environ Sci 2024, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmad A, Ramli I, Nizamuddin N (2023) Impact of land use and land cover changes on carbon stock in Aceh Besar District, Aceh, Indonesia. J Water L Dev 159–166. [CrossRef]

- Kustura, K.; Conti, D.; Sammer, M.; Riffler, M. Harnessing Multi-Source Data and Deep Learning for High-Resolution Land Surface Temperature Gap-Filling Supporting Climate Change Adaptation Activities. Remote Sens 2025, 17, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmad A, Ramli I, Irwansyah M (2020) The impacts of land use and cover changes on ecosystem services value in urban highland areas. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V. Estimating land surface temperature in ArcGIS using Landsat-8, Hoshangabad district, (Madhya Pradesh). Int J Appl Res 2017, 3, 1374–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrino, J.A.; Jiménez-Muñoz, J.C.; Paolini, L. Land surface temperature retrieval from LANDSAT TM 5. Remote Sens Environ 2004, 90, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Orozco, D.L.; Ruiz Corral, J.A.; Villavicencio García, R.F.; Rodríguez Moreno, V.M. Deforestation and Its Effect on Surface Albedo and Weather Patterns. Sustain 2023, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Imran H, Issa Shammas M, Rahman A, J. Jacobs S, W. M. Ng A, Muthukumaran S (2021) Causes, Modeling and Mitigation of Urban Heat Island: A Review. Earth Sci 10:244. [CrossRef]

- Ullah N, Siddique MA, Ding M, Grigoryan S, Khan IA, Kang Z, Tsou S, Zhang T, Hu Y, Zhang Y (2023) The Impact of Urbanization on Urban Heat Island: Predictive Approach Using Google Earth Engine and CA-Markov Modelling (2005–2050) of Tianjin City, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Kowe, P.; Dube, T.; Mushore, T.D.; Ncube, A.; Nyenda, T.; Mutowo, G.; Chinembiri, T.S.; Traore, M.; Kizilirmak, G. Impacts of the spatial configuration of built-up areas and urban vegetation on land surface temperature using spectral and local spatial autocorrelation indices. Remote Sens Lett 2022, 13, 1222–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komeh, Z.; Hamzeh, S.; Memarian, H.; Attarchi, S.; Alavipanah, S.K. A Remote Sensing Approach to Spatiotemporal Analysis of Land Surface Temperature in Response to Land Use/Land Cover Change via Cloud Base and Machine Learning Methods, Case Study: Sari Metropolis, Iran. Int J Environ Res 2025, 19, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmad A, Ramli I, Nizamuddin N (2025) Monitoring Land Use and Land Cover Changes in Aceh Province-Indonesia for Sustainable Spatial Planning BT - Inclusive and Integrated Disaster Risk Reduction. In: Opdyke A, Pascua de Rivera L (eds). Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, pp 82–94. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; He, Z.; Ma, D.; Wang, W.; Qian, L. Temperature trends and its elevation-dependent warming over the Qilian Mountains. J Mt Sci 2024, 21, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire CR, Nufio CR, Bowers MD, Guralnick RP (2012) Elevation-Dependent Temperature Trends in the Rocky Mountain Front Range: Changes over a 56- and 20-Year Record. PLoS One. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Serrano F, López-Moreno JI, Azorin-Molina C, Alonso-González E, Aznarez-Balta M, Buisán ST, Revuelto J (2020) Elevation effects on air temperature in a topographically complex mountain valley in the Spanish pyrenees. Atmosphere (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Xu L, Du J, Ren J, Hu Q, Qin F, Mu W, Hu J (2024) Improving the ERA5-Land Temperature Product through a Deep Spatiotemporal Model That Uses Fused Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shen, X.; Fan, G. Elevation-dependent trend in diurnal temperature range in the northeast china during 1961–2015. Atmosphere (Basel) 2021, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmad, A.; Ramli, I.; Sugiarto, S.; Irzaidi, I.; Izzaty, A. Assessing and Forecasting Carbon Stock Variations in Response to Land Use and Land Cover Changes in Central Aceh, Indonesia. Int J Des Nat Ecodynamics 2024, 19, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M.P. Mapping and analyzing temporal variability of spectral indices in the lowland region of Far Western Nepal. Water Pract Technol 2023, 18, 2971–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wu, W.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, J.; Hu, T.; Wang, P. Correlation analysis of land surface temperature and topographic elements in Hangzhou, China. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taripanah, F.; Ranjbar, A. Quantitative analysis of spatial distribution of land surface temperature (LST) in relation Ecohydrological, terrain and socio- economic factors based on Landsat data in mountainous area. Adv Sp Res 2021, 68, 3622–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitis, T.; Klaic, Z.B.; Moussiopoulos, N. Effects of topography on urban heat island. 10th Int Conf Harmon within Atmos Dispers Model Regul Purp 2005, 1, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, H.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Shi, H.; Zhao, J. Exploring the impact of urban spatial morphology on land surface temperature: A case study in Linyi City, China. PLoS One 2025, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Zhou Z, Wen Q, Chen J, Kojima S (2024) Spatiotemporal Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Impact on Urban Thermal Environments: Analyzing Cool Island Intensity Variations. Sustain. [CrossRef]

- Achmad, A.; Ramli, I.; Nizamuddin, N.; Gunawan, A.; Fakhrana, S.Z.; Zhong, X. The impact of land use and land cover changes on ecosystem service value in Aceh Besar Regency, Aceh, Indonesia. Land 2024, 13, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet P, Grieger S, Putzenlechner B, Seidel D (2025) Forests with high structural complexity contribute more to land surface cooling: empirical support for management for complexity. J For Res. [CrossRef]

- Thammaboribal, P.; Tripathi, N.K.; Lipiloet, S. Comparative Analysis of Land Surface Temperature (LST) Retrieved from Landsat Level 1 and Level 2 Data: A Case Study in Pathumthani Province, Thailand. Int J Geoinformatics 2025, 21, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Cheng, J.; Guo, H.; Guo, Y.; Yao, B. Accuracy Evaluation of the Landsat 9 Land Surface Temperature Product. IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens 2022, 15, 8694–8703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, M.; Ozenen Kavlak, M.; Senyel Kurkcuoglu, M.A.; Bilge Ozturk, G.; Cabuk, S.N.; Cabuk, A. Determination of land surface temperature and urban heat island effects with remote sensing capabilities: the case of Kayseri, Türkiye. Nat Hazards 2024, 120, 5509–5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvar Z (2024) PyLST : A Python-based application for retrieving. 0–18. [CrossRef]

- Mohiuddin G, Mund J-P (2024) Spatiotemporal Analysis of Land Surface Temperature in Response to Land Use and Land Cover Changes: A Remote Sensing Approach. 15. [CrossRef]

- Jiang Y, Li X, Huang J (2022) Zoning Optimization Method of a Riverfront Greenspace Service Function Oriented to the Cooling Effect: A Case Study in Shanghai. Int J Environ Res Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Balany, F.; Ng, A.W.M.; Muttil, N.; Muthukumaran, S.; Wong, M.S. Green infrastructure as an urban heat island mitigation strategy—a review. Water (Switzerland) 2020, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shaar W, Bonin O, de Gouvello B (2022) Scenario-Based Predictions of Urban Dynamics in Île-de-France Region: A New Combinatory Methodologic Approach of Variance Analysis and Frequency Ratio. Sustain. [CrossRef]

- Wang J, Tang BH, Zhu X, Fan D, Li M, Chen J (2024) A comparative analysis of five land surface temperature downscaling methods in plateau mountainous areas. Front Earth Sci. [CrossRef]

| Elevation (meter above sea level) | Range on Degree in Celcius based on colour in the map | |

|---|---|---|

| 900 | 20 - 21 | 22 – 24 |

| 1,000 | 20 - 21 | 22 – 24 |

| 1,100 | 20 – 21 | 22 – 24 |

| 1,200 | 20 – 21 | 22 – 24 |

| 1,300 | 18 – 19 | 20 – 21 |

| 1,400 | 18 – 19 | 20 – 21 |

| 1,500 | 18 – 19 | 20 – 21 |

| 1,600 | 9,5 - 17 | 20 – 21 |

| 1,700 | 9,5 - 17 | 18 – 19 |

| 1,800 | 9,5 - 17 | 18 – 19 |

| 1,900 | 9,5 - 17 | 18 – 19 |

| 2,000 | 9,5 - 17 | 18 – 19 |

| 2,100 | 9,5 - 17 | 9,5 - 17 |

| 2,200 | 9,5 - 17 | 9,5 - 17 |

| 2,300 | 9,5 - 17 | 9,5 - 17 |

| 2,400 | 9,5 - 17 | 9,5 - 17 |

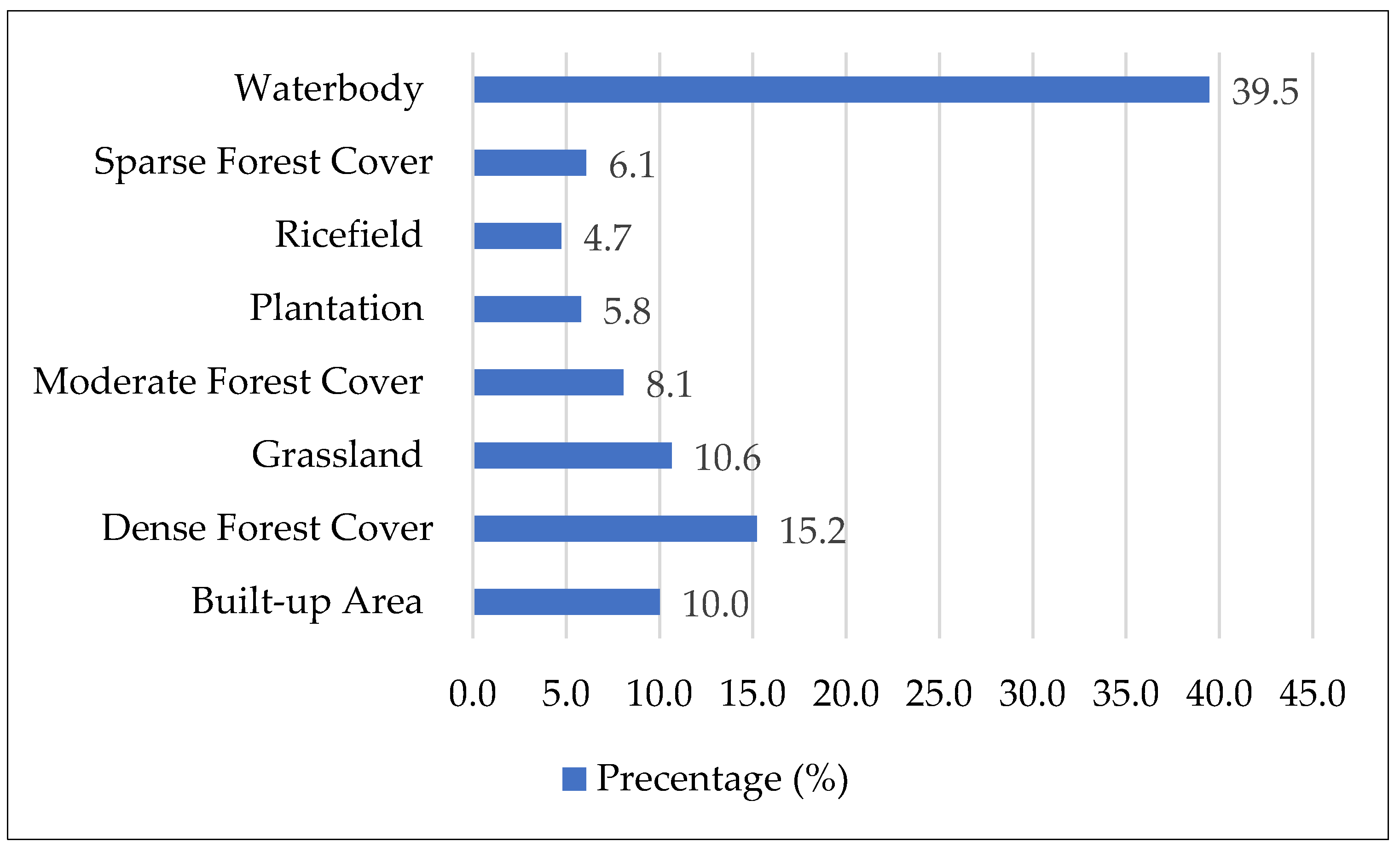

| Classification | Area (Ha) |

|---|---|

| Built-up Area | 1.438 |

| Dense Forest Cover | 2.187 |

| Grassland | 1.530 |

| Moderate Forest Cover | 1.159 |

| Plantation | 832 |

| Rice field | 679 |

| Sparse Forest Cover | 873 |

| Waterbody | 5.670 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).