1. Introduction

Flooding is a serious and universal hazard, resulting in economic, social, and environmental damage [

1,

2,

3] . It is a rapidly growing threat to most coastal regions due to alterations in rainfall intensity, sea level rise (SLR), and the intensification of cyclones driven by climate change [

4]. Tropical coastal cities located in low-lying areas are highly vulnerable to flooding [

5]. Approximately 62% of the global low-lying area, with an elevation of less than two meters above sea level, is in tropical regions. Urbanization in these low-lying plains has exposed the population and development activities to an increased risk of flooding [

6,

7]. The interaction between natural processes and anthropogenic activities has increasingly transformed coastal flooding into complex compound events [

7,

8].

Compound events are combinations or successive occurrences of two or more flood drivers leading to substantial exacerbation of flood extent, depth, and duration, thereby resulting in more severe damage to life and property [

8,

9]. Previous studies in tropical regions have primarily concentrated on evaluating individual flood drivers, such as pluvial flooding due to extreme rainfall and river flooding [

10,

11]. Although these studies provide valuable insights, their emphasis on individual factors for evaluating flooding behavior offers an inadequate understanding and visualization of the compound flooding problem, particularly in tropical coastal cities. Relying solely on these outcomes results in insufficient preparedness and potential failure of flood mitigation measures, exposing communities to a greater risk of flood impacts [

3].

Recently, the risk from compound events has become prominent in tropical cities [

7,

12,

13]. Projected climate change outcomes indicate that compound flooding will likely become the new normal in the future [

4]. However, evaluations of this complex phenomenon are limited due to the need for tools with high computational power at a reasonable cost, acceptable processing times, and comprehensive data to provide an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The availability of such resources, primarily in extra-tropical locations, has provided opportunities to model these complex phenomena [

19,

20,

21]. Nevertheless, in tropical catchments, relatively few studies have tried to understand the interactions between extreme precipitation-caused pluvial, river, and coastal flooding [

6,

10,

11]. Many tropical areas encounter challenges in conducting such studies due to a lack of high-resolution digital elevation models, flood records, and research resources.

Particularly in wet tropical catchments, a quantitative assessment of compound flooding is critical for urban planning, the development of flood mitigation measures, and disaster preparedness [

22]. The current understanding, based on an analysis of individual flood phenomena, is not enough to guide future adaptation, as it does not effectively characterize the potential future impact of flooding. Alternatively, assessing the combined effect of numerous significant factors presents a complex problem that consistently results in high uncertainty and errors. A comprehensive understanding of such events can inform future flood mitigation technologies and decrease flood risk in the context of climate change scenarios [

12,

21]. Moreover, the outcomes of such studies should be indicators of a range of possibilities, rather than being regarded as conclusive. Nonetheless, these study outcomes are essential for ensuring that adaptation planning is informed by information and is realistic.

Therefore, this study has adopted a scenario-based hydrodynamic model to examine the impact of compound flooding in a wet tropical catchment. This study aims to address the following questions regarding current and future climate change: (i) How does compound flooding propagate in a wet tropical catchment? (ii) How does climate change impact this compound flooding?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Saltwater Creek is a short, moderately steep, mixed urban-forest catchment with a total area of 16 km

2 in the far northern tropical coastal city of Cairns, Queensland, Australia. This study considers 9.09 km

2 (57%) of the total catchment area as the study site. This fraction of the total catchment area selected for the study site was determined based on the water level measured at the drainage outlet (

Figure 1). The catchment length (from west to east) is ~ 6 kilometers, and its elevation ranges from -0.11 m to 354 m above Australian Height Datum (AHD; average sea level). The steep headwaters make the catchment highly responsive to rainfall events.

Saltwater Creek is a complex catchment featuring numerous interconnected natural and artificial drainage networks, as shown in

Figure 1. This catchment encompasses a diverse range of land uses and land covers, including residential buildings, roads, business areas, public buildings (such as schools), a botanical garden, open parks, a wetland, lagoons, and a tropical rainforest located at the upstream end of the catchment. In addition, this catchment demonstrates multiple interactions between several water bodies, adding further complexities to understanding flood hazards. The runoff discharged from urban areas is intercepted by grey measures, such as those on roads and roofs. It is redirected to the nearest natural stream and the artificial drainage network connected to Saltwater Creek, ultimately discharging into the ocean. Due to its low-lying topography, it is vulnerable to the impacts of tidal inundation and sea level rise due to climate change. These interactions have led to past instances of pluvial, fluvial, and coastal flooding. Compound flooding is expected to continue and intensify, driven by climate change. Consequently, Saltwater Creek serves as an ideal study site for understanding the dynamics of compound flooding in tropical catchments.

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) classifies Cairns as part of the wet tropical climatic zone. This city experiences an annual average rainfall that ranges between 1997 mm and 3148 mm. The maximum monthly precipitation during the wet season, from December to April, can reach 1417 mm, while the rest of the year remains predominantly dry, from July to November. Cairns experiences temperatures ranging from a mean maximum of 29.4°C to a mean minimum of 21.0°C; however, the maximum temperature can rise to 42.6°C during hot, humid summer days.

2.2. Datasets

2.2.1. Digital Elevation Model (DEM)

A high-resolution 0.5 × 0.5 m digital elevation model (DEM) was generated from a 2021 Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) obtained from the Cairns Regional Council (CRC). The DEM defines the catchment topography, as demonstrated in

Figure 1, and has been utilised in this study for catchment delineation and underpinning hydrological and hydraulic modelling.

2.2.2. Rainfall

The climate record from the Cairns Aero Station (31011), located at a latitude of -16.87°N and a longitude of 145.75°E, spanning the period from 1943 to 2024, was analysed [

23]. The rainfall, water level, and tidal level data were collected using different instruments, maintained by the CRC and the Queensland government [

24]. The features such as rain gauges, tidal stations and sensor location at the outlet of Saltwater Creek are highlighted in

Figure 2.

The rainfall data were supplied as cumulative totals at five-minute intervals over a day, with the accumulation resetting to zero at the end of every day. However, none of the rain gauge stations were located within the study site. The four nearest rain gauge stations were used to estimate the distributed rainfall value in this study. The IDW method was adopted to spatially distribute rainfall using interpolation from the sub-catchment centroid to the whole[

25].

2.2.3. Water Level

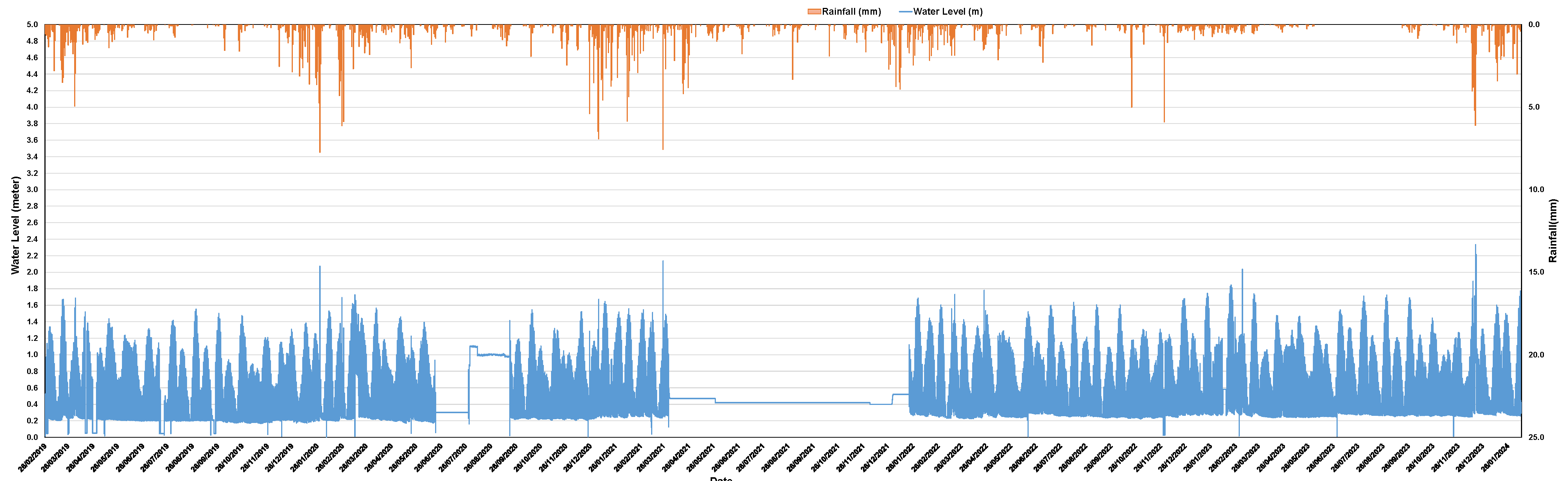

A pressure transducer was installed to collect water level every 5 minutes from 2019 to 2024 by CRC [

26]. Water level data for model calibration and validation were collected by CRC at the catchment outlet. A hydrograph of water level and rainfall data was prepared to check the consistency of the data as presented in

Figure 3.

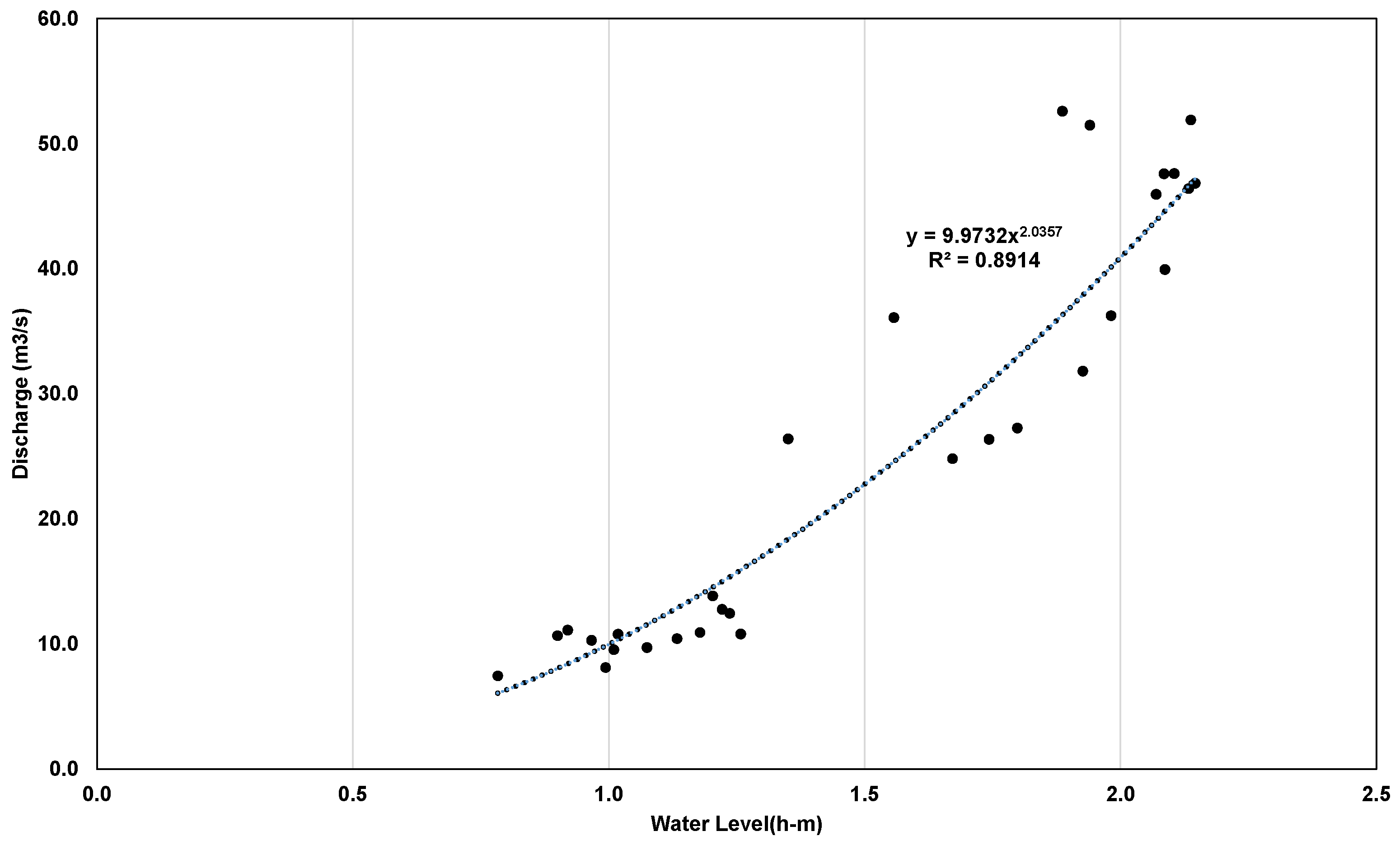

Flow velocity measurements were conducted at the Greenslopes Street sensor location to develop the rating curve for model calibration and validation. A portable current meter was employed, with water level measurements made using a levelling staff [

27]. The water level recorded during the velocity measurement was later cross-checked against the sensor water level data for validation. The tidal and non-tidal flow velocity components were separated by comparing flow velocity with water level and rainfall data. The tidally influenced data points were removed from the analysis, and only rainfall-driven flow was utilised to develop the rating curve. The discharge calculated from this data was further used to develop the rating curve (

Figure 4). The regression equation generated from the rating curve was adopted to convert the water level measured by the sensor into discharge results, which were then employed for model calibration and validation.

2.2.4. Tidal Datasets

Storm tide data is another critical data required for understanding flood hazards in this catchment. Every 10 minutes, tidal level data were obtained from the Cairns Storm Surge No. 7 Wharf tide gauge (

Figure 2) via the Queensland Government's open data portal [

24]. The lag time between the tidal cycle and its impact at the Greenslopes street outflow was calculated, revealing a maximum lag time of 10 to 20 minutes, which was deemed insignificant. However, tidal data were used for modelling, adjusted for this lag time. This short lag may be attributed to the equidistant location of both sensors (approximately 4.5 kilometers) from the tidal divergence points inside Saltwater Creek to the Wharf Station, where the tidal measurements are taken.

2.2.5. Hydrological Data

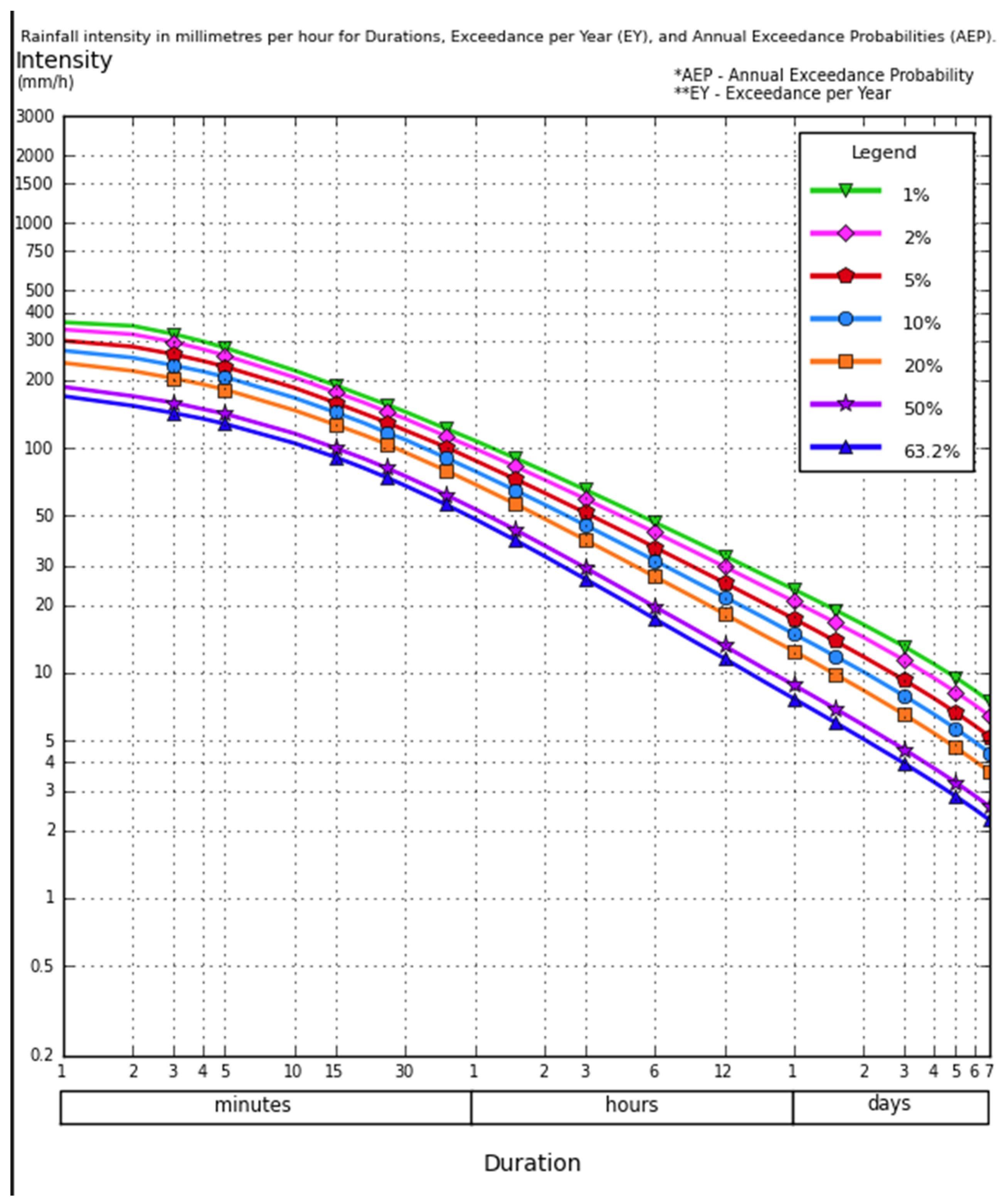

The areal temporal patterns (ATP), areal reduction factors (ARF), and losses were downloaded from the ARR Data Hub website for the study site. Here, ATP refers to a data type that illustrates how rainfall data varies over time within the catchment; this is essential for providing a realistic simulation of storm behavior [

28]. ARF adjusts the point rainfall data to reflect average rainfall over a large catchment. Intensity-frequency-duration (IFD) data were downloaded from the BOM website, which lists frequent and infrequent events extending from 1% Annual Exceedance Probability (AEP) corresponding to a 100-year return period to 63.2% AEP (1.58 years) with durations ranging from 1 minute to 168 hours, as shown in

Figure 5. The IFD data provides information on estimated extreme rainfall intensities over different durations and return periods.

2.2.6. Land Use/Land Cover

The data, such as Land use and Land cover, were obtained from the Cairns Council. The classification for land use areas encompasses rooftops, roads, driveways, forests, open spaces, swimming pools, wetlands, and creeks, as illustrated in

Figure 6. The precision of these datasets was further validated through desk verification, consultations with the relevant authorities, field inspections, on-ground measurements, and utilisation of Queensland Globe [

29].

An urban catchment can be generally divided into impervious areas with direct connection to drainage (DCIA), impervious surfaces without direct connection (ICIA), and pervious or semi-pervious surfaces [

30]. DCIA is the division of total impervious area (TIA) that is hydraulically linked to the drainage system, serving as a reliable catchment boundary for determining actual urban runoff [

31]. In addition, ICIA is a division of TIA, which does not have a direct runoff contribution to the drainage network. Quantifying these values is critical to improving rainfall-runoff modelling, with the catchment comprising 47% DCIA, 27% ICIA, and 27% pervious surfaces.

The maximum area is occupied by forest, followed by green space. While the pool and wetlands cover the least area. The impervious area, composed of buildings, roads, pavements, and pools, accounts for almost 47% of this catchment.

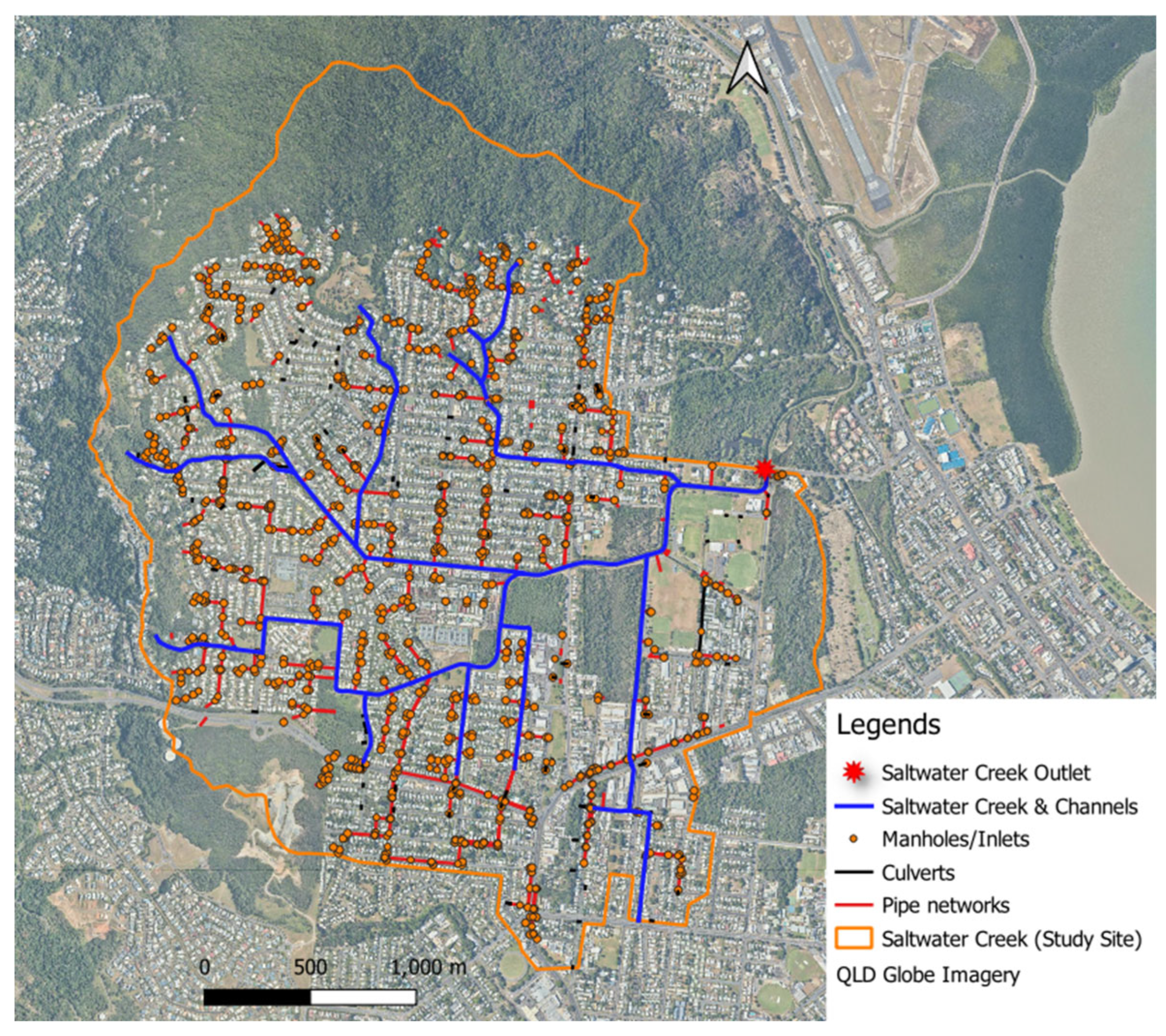

2.2.7. Drainage Data

Currently, the council manages stormwater runoff using grey infrastructure technologies such as pipe networks, manholes, inlets, and discharges into the nearest natural or partially paved open concrete channels, as shown in

Figure 7. This data was gathered from the council team, followed by a desk study, consultations and field measurements to further validate the data.

2.2.8. Geology and Soil Type

The geological and soil types in the Saltwater Creek catchment are underlain by the highly deformed metasedimentary Hodgkinson Formation [

32], which is exposed at the surface only in the upper catchment. Across the mid-catchment location, the bedrock is overlain by sand, silt, mud, and a gravelly ferrosol (with a clay loam to clay texture) near creek locations. Bedrock in the lowermost location of this catchment is overlain by Holocene clay, silt, sand, estuarine and deltaic deposits. Furthermore, initial and continuous loss accounting for how soil and plants enable infiltration and evaporation, associated with these soil types, were obtained from the Queensland Government website.

2.2.9. Climate Change Data

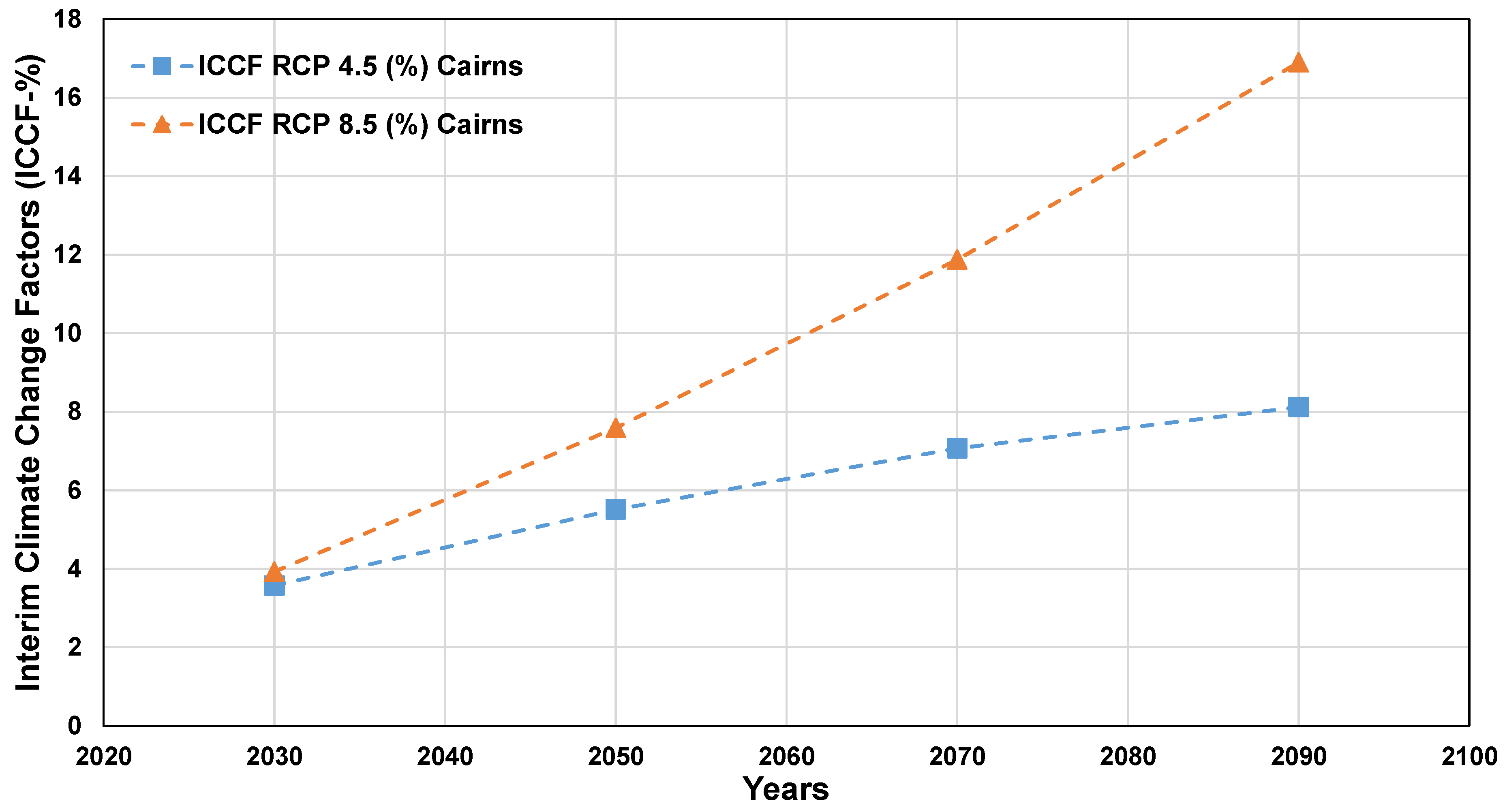

The climate change scenarios and data were sourced from the Queensland Government Long Paddock website [

33], which contains regional maps illustrating the projected mean temperature for each local area in Queensland. Due to the availability of higher-resolution and more precise data, this study has adopted the results from the Long Paddock website instead of those from the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM), Australia. As explained in publication [

34], published by a similar group of authors, we adopted the same method to calculate climate change scenarios by using temperature data. The interim climate change factors (ICCF) generated from the calculation are presented (

Figure 8).

2.3. Method

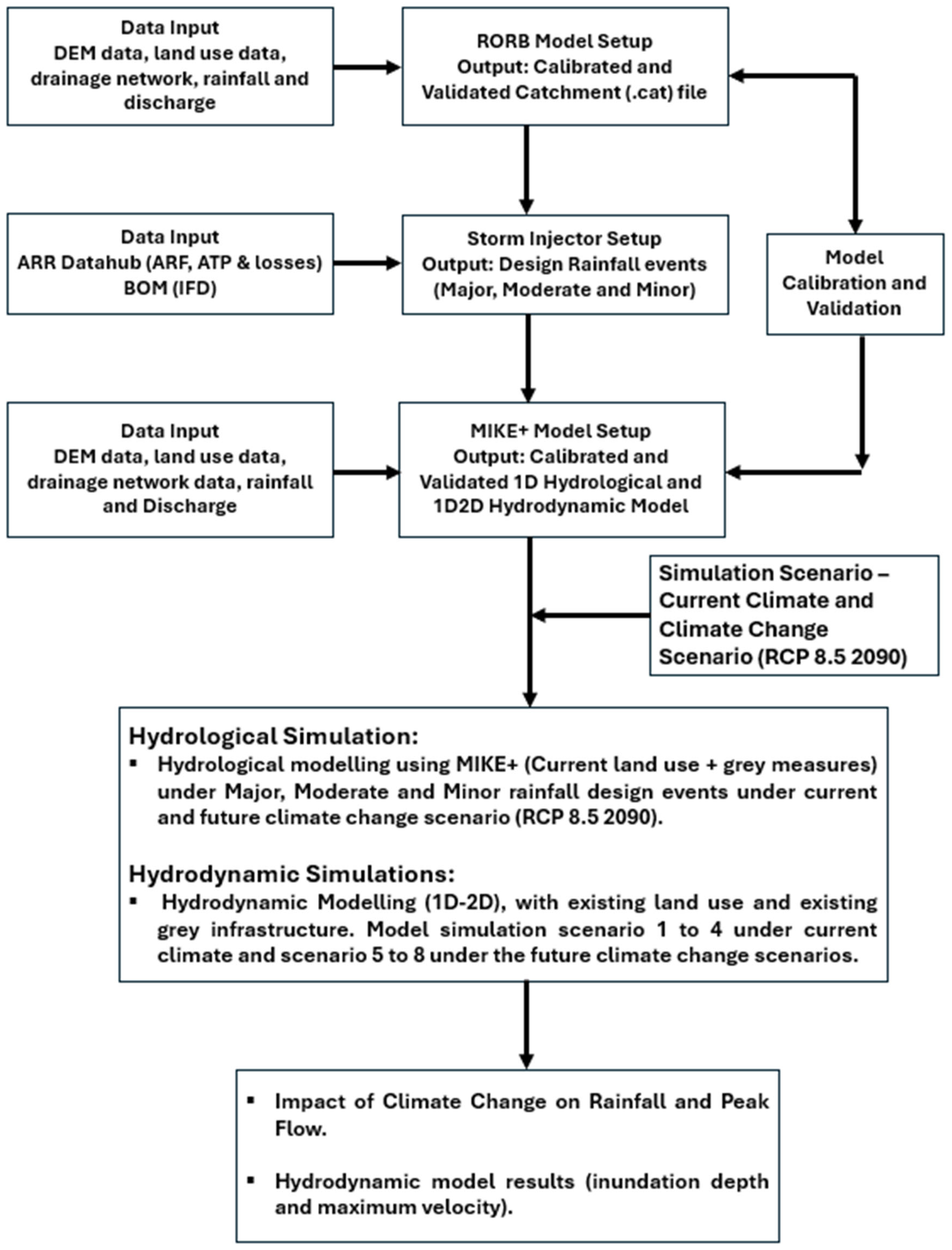

The research methods flow chart adopted for this study is presented as a flow chart. Each step adopted for the hydrological and hydrodynamic model setup, calibration, validation, and simulation scenarios is given in

Figure 9.

2.3.1. Rainfall-Runoff Model Selection and Setup

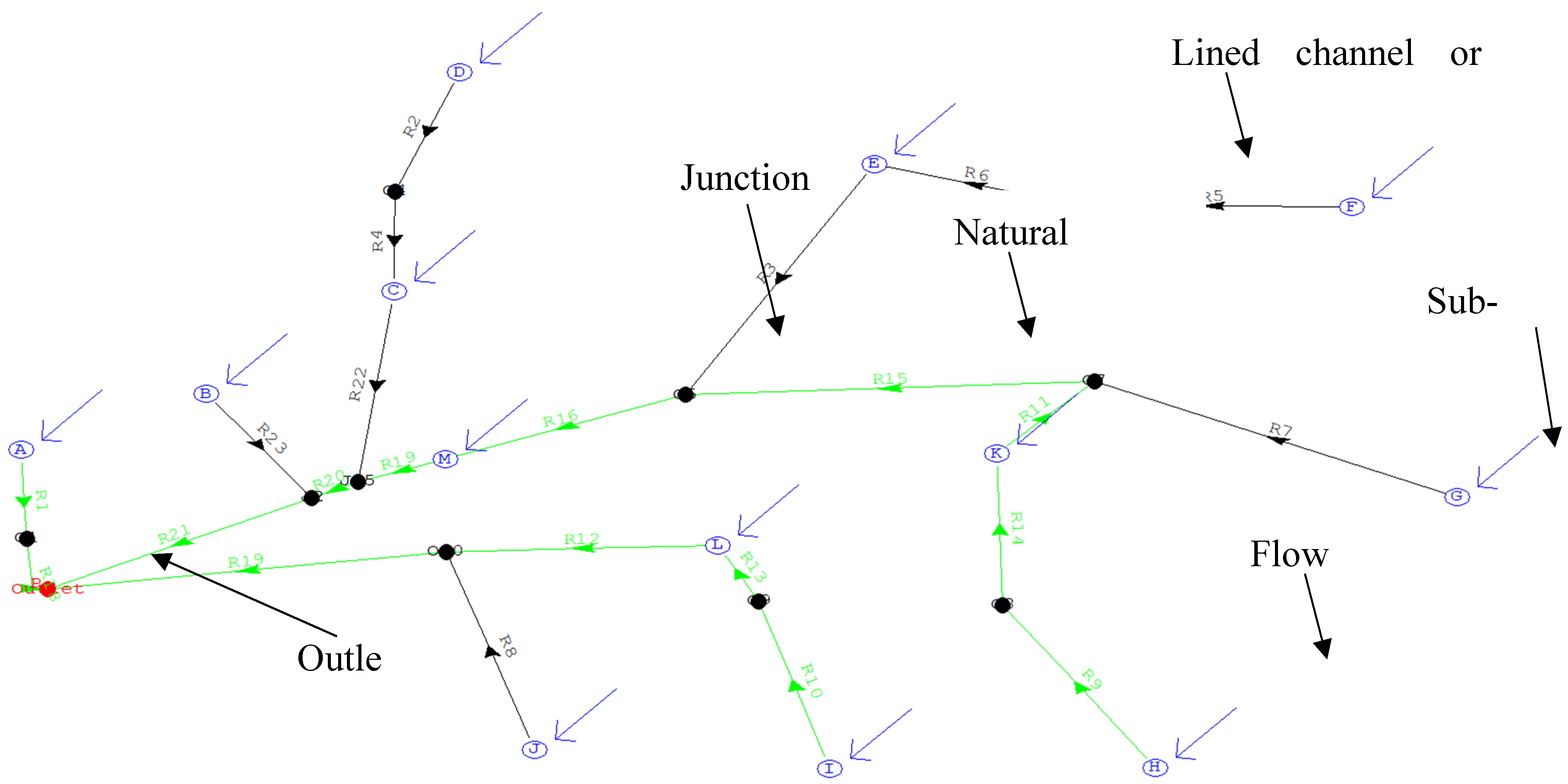

RORB was selected for hydrological simulation due to its free availability and wide range of applications in Australian catchments [

35]. This tool is a streamflow routing program that calculates hydrographs from rainfall and subtracts losses from rainfall due to evapotranspiration and infiltration to generate runoff [

36]. The RORB model delineated and developed a catchment with 14 sub-catchments from DEM for further modelling work (

Figure 10).

2.3.2. Hydrodynamic Model Set Up

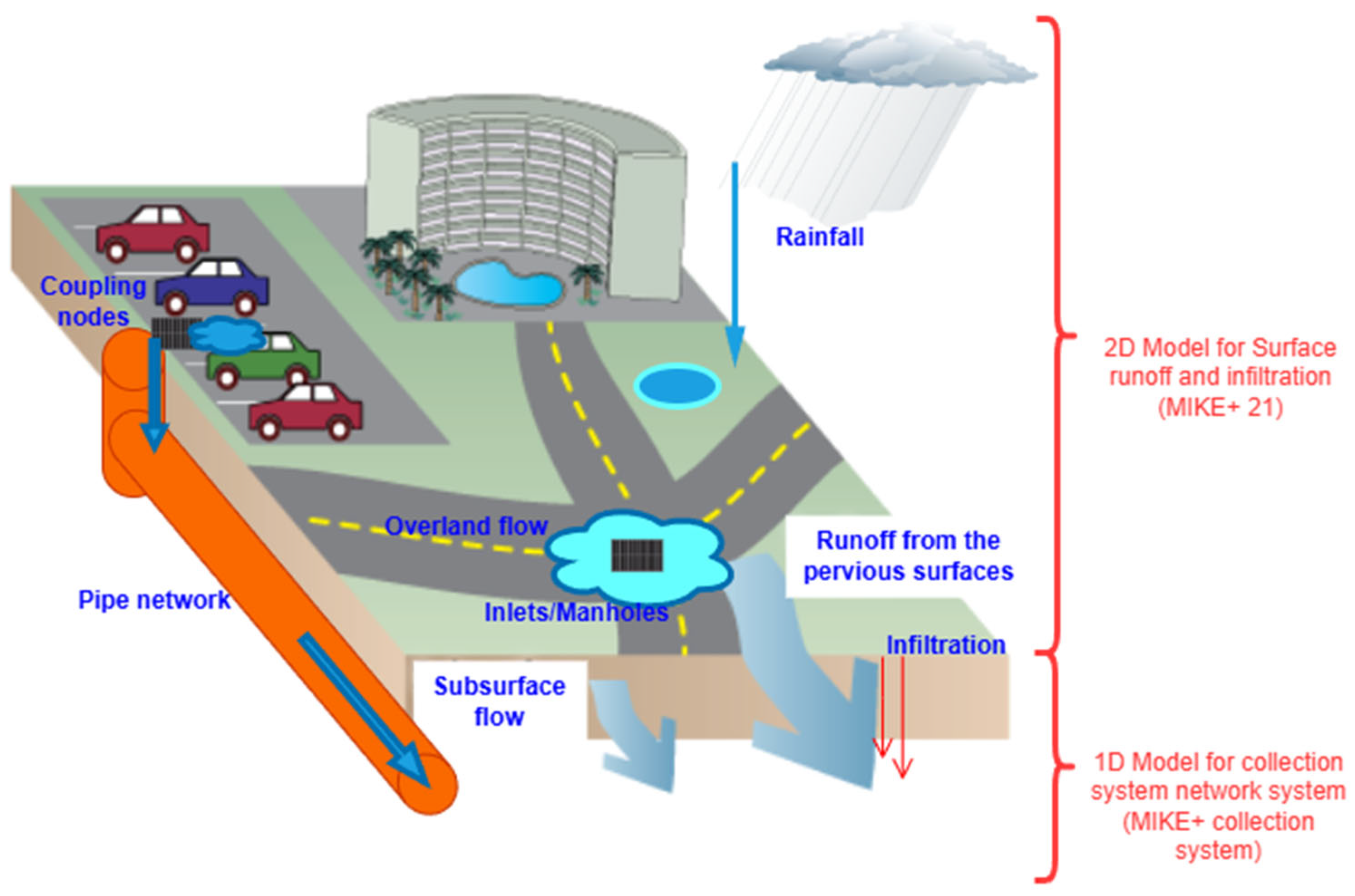

MIKE+ hydrodynamic model was adopted in this study due to its wide range of global use in industry and academia, and its integrated platform capacity to conduct both hydrological and hydrodynamic simulations and its coupling capability of 1D and 2D geometry [

37,

38,

39].

The catchment area was delineated by the MIKE+ automatic tools and further refined through manual delineation, taking into account the catchment contours, road network, and underground drainage. At the final stage, 141 sub-catchments were finalised for hydrological simulation using the kinematic wave method, with sub-catchments ranging in size from 0.013 to 0.35 km².

The MIKE+ collection system (CS) platform was utilised to define the pipe networks, inlets, manholes, culverts and canals at this study site. Then, each catchment is coupled to the CS system, illustrating the flow received by nodes. Additionally, the 2D overland flow platform within the model was employed to develop a rectangular grid with a spatial resolution of 1 m × 1 m.

The catchment boundary condition variable was defined using the design rainfall time series. Additionally, 2D water level time series with tidal time series levels are defined at the boundary location where the creek and ocean interactions occur.

The initial water level condition was defined as varying in the domain at the wetlands, creeks and river channels. [

37,

38,

39]

The model coupling platform within MIKE+ allows for hydrodynamic interaction between surface water (2D) and subsurface stormwater (1D) domains (

Figure 11). The MIKE+ coupling platform enables the coupling of two domains using inlets, manholes and outlets.

2.3.3. Rainfall Design Events

Storm Injector, commercial software [

41], was used to develop rainfall design events for flood modelling under current and future climate change scenarios, along with the required results that link RORB and MIKE+.

This tool features an integrated platform for managing hydrologic model catchment files created in RORB. The catchment files from the RORB model are populated with storm files directly extracted from the ARR data hub, as well as the IFD curve from the BOM. This data was required to generate peak flow and critical time-to-peak flow hydrographs, among several temporal pattern combinations, as recommended by the ARR guideline for flood modelling in the Australian context. This tool also has additional capacity to incorporate climate change scenarios and calculate design events under future climate scenarios.

2.3.4. Calibration and Validation Event Selection

Model calibration and validation were conducted to evaluate the comparative performance of simulated results against measured flow. The approach identified and described in the AAR (2019) was adopted for selecting events for calibration and validation [

42] .

Storm selection criteria were based on cumulative storm depth, maximum duration, antecedent rainfall, end of rainfall, flow, and burst duration. Additional criteria for the discharge range were also considered for further simplification based on the measured water level during this study. Discharges greater than 40 m³/s were regarded as major, 20 to 40 m³/s as moderate, and less than 20 m³/s as minor events. We selected six events for model calibration and three events for validation, as described in

Table 1.

2.3.5. Model Calibration and Validation

The model calibration and validation approaches were based on the relative comparison of simulated and measured outflow hydrographs. The performance of the hydrological model was evaluated using several goodness of fit criteria, including Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE), ratio of root mean square error (RMSE) to the standard deviation of the observation (RSR), Percent Bias (PBIAS), peak and volume [

43].

The NSE value ranges from 1 to -∞; NSE = 1 indicates perfect agreement between modelled and observed data; NSE = 0 means the mean of the observed data is as accurate as the model predictions. RMSE is the mean difference between a statistical model's predicted values and measured values. In addition, the PBIAS parameter was used to measure the tendency of modelled results to be below or above the measured results. Finally, the peak flow / total volume error is also assessed, as peak flow is a hydrological parameter and a critical input for hydraulic design [

25].

Model sensitivity testing was performed by testing the critical parameters, including time steps, grid size, and numerical solution setup. Selecting optimal parameters increases model accuracy, reduces computation time, lowers storage requirements, and improves stability.

2.3.6. Simulated Scenarios

MIKE+ hydrological modelling and hydrodynamic compound modelling scenarios were conducted to assess the impact (

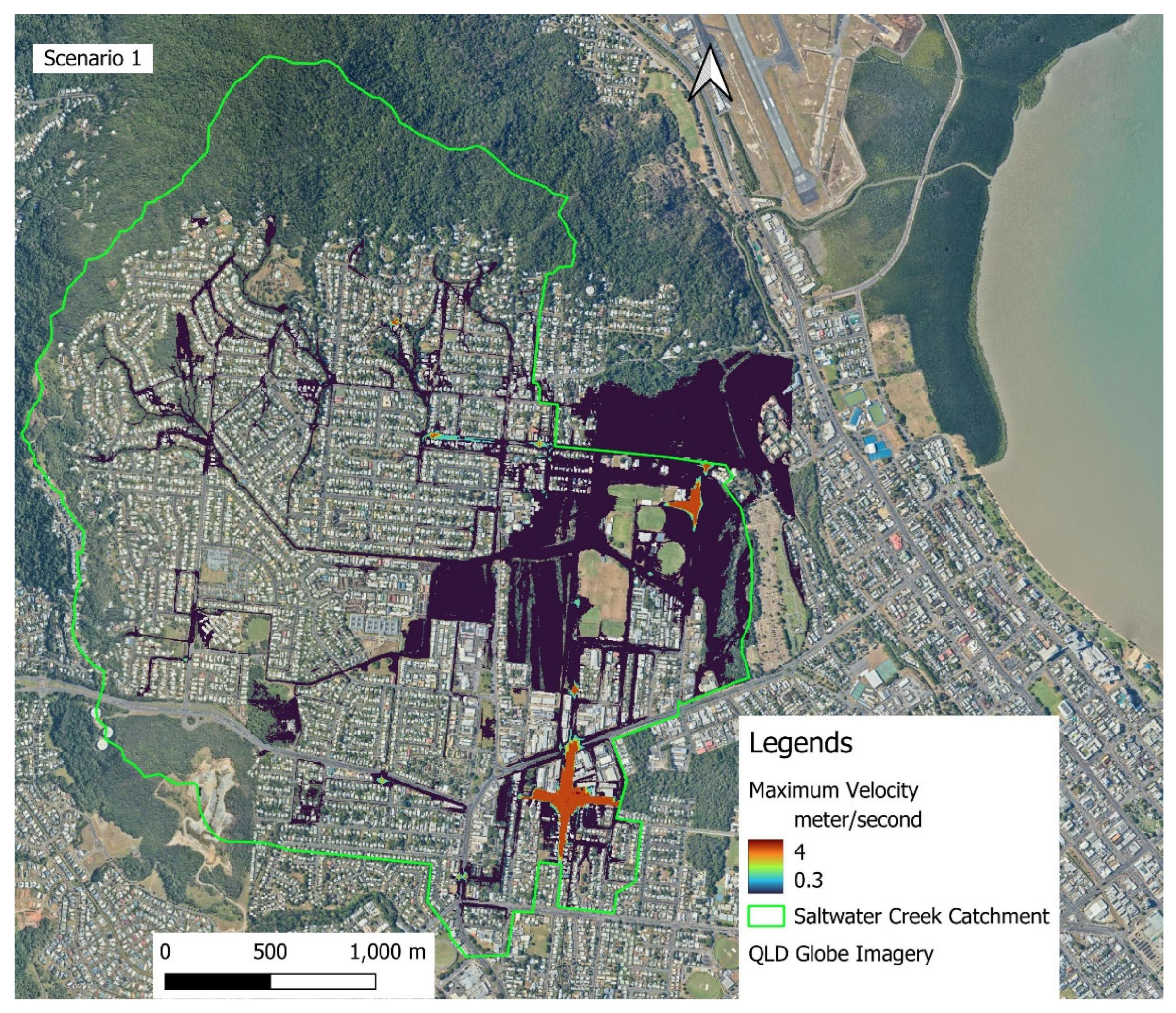

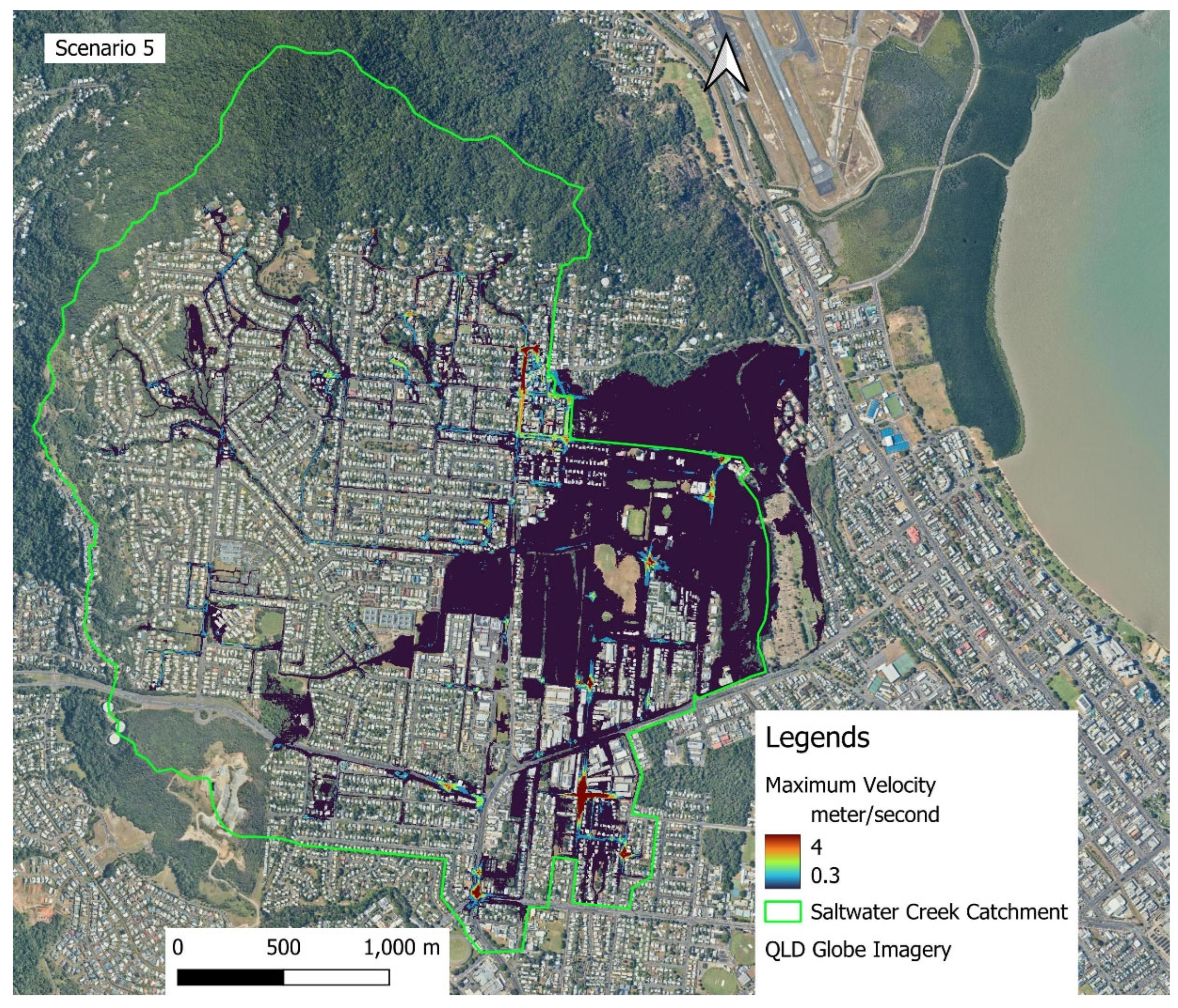

Table 2). The hydrological model was used to simulate three design rainfall events under the current climate (CC) and a future climate change scenario (RCP 8.5, 2090). In addition, hydrodynamic simulation scenarios 1 represent compound flooding under CC scenarios, while scenarios 5 represent the corresponding compound flooding under future climate change scenarios with RCP 8.5 in 2090.

3. Results

3.1. Hydrological Model Calibration/Validation

The simulated and observed stream flows for Saltwater Creek at the Greenslopes street outlet were used during the calibration and validation. A total of six events were selected for model calibration, and three events were chosen for validation. The calibrated and validated results are summarized in

Table 3. The models demonstrated strong overall performance during calibration, with NSE values for calibration periods at the Saltwater Creek outlet ranging from 0.59 to 0.81 and 0.5 to 0.92, respectively, for the RORB and MIKE+ models. Similarly, the validation NSE results for RORB and MIKE+ range from 0.73 to 0.95 and 0.57 to 0.85, respectively. The NSE results range from good to very good performance ratings, indicating good overall model performance [

25,

43]. Since the events considered for model calibration and validation range from major to minor, the model can reliably estimate a broad range of flow conditions. Both models exhibited low peak flow estimation errors (<±5%) for most events, indicating strong alignment with observed peak flows.

Model Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis indicates that a coarse grid size results in higher errors with slower convergence. At the same time, a grid size that is too fine requires a more powerful computer to run simulations for an extended period. To address both limitations, optimal grid size sensitivity testing was conducted. The grid size of the model was set to 1 m × 1 m, 2 m × 2 m, 3 m × 3 m, and 4 m × 4 m. Sensitivity testing determined that an optimal grid size was 2 m × 2 m. The 1 m x 1 m grid required 24 hours of synthetic testing. In contrast, other grid sizes yielded a significant error in assigning surface elevation to the 1D2D domain-coupled locations. During simulation, the elevation difference between the two coupled domains was up to 10 m, exceeding the threshold limit, which impacts the model's stability, flow inundation, and runoff exchange between the domains.

In addition, the sensitivity testing time-step selection for hydrodynamic modelling using MIKE+ determines the stability of the modelling process. The optimal time step selection requires updating the equation governing fluid flow to provide detailed flow characteristics. A step that is too large increases numerical instability and reduces accuracy, whereas a step that is too small requires a substantial increase in computing time. This model identified a 1-second time step for 2D overland flow as an optimal time step and 60 seconds for the surface runoff models.

The low-order fast algorithm was selected over the high-order, more accurate algorithm due to the higher time requirement for simulations using the latter. The wetting and drying depths must be considered to capture the inundation depth within the catchment. A 2 mm (wetting depth) and 3 mm (drying depth) were identified as appropriate during this sensitivity testing. The small drying and wetting depth captures the water level in a low-lying area.

3.2. Climate Change Impact on Hydrology

The alteration in rainfall depth under major, moderate, and minor design events, as well as climate change scenarios such as CC and RCP 8.5, is presented in

Table 4. The results show an increase in rainfall depth when comparing CC and RCP 8.5 for 2090. Meanwhile, the major and moderate events observed a 14% increase in rainfall depth, while minor events showed a 19% increase, during RCP 8.5 2090 compared to the CC.

Similarly, the peak flow increment during RCP 8.5 2090 ranges from 17% to 21% for rainfall design events when compared to the CC. All the modelled rainfall events resulted in a significant increase in rainfall and peak flow, implying a potential severe flooding risk during future climate scenarios. In conclusion, the results suggest that climate change has a disproportionately greater impact on minor hydrological extremes compared to major events.

3.3. Hydrodynamic Model Result

3.3.1. Inundation Depth

The compound effects of rainfall, tidal and SLR under current and future climate scenarios were examined. The flood maps show the altered maximum water depth, flooding hotspots, flood extent area and critical grey measures

Figure 13. S1 represent flood maps that illustrate the compound effects under current climatic conditions, and S5 represent corresponding combination scenarios under climate change (RCP 8.5, 2090).

Under the CC scenario, the study site has an inundating proportion of 18% (S1) of the catchment area. The maximum inundation occurs when major rainfall coincides with a high tidal level. Different locations within the catchment exhibited varying maximum inundation depths, ranging from 0 to 4.6 m (S1). The maximum water level increase was observed along the flow paths of Saltwater Creek and its tributaries. The inundation depth was further distributed along the low-lying areas and for 50 m on either side of the Saltwater Creek corridor.

Figure 12.

Compound flooding events, inundation depth, maximum water level variations and flood extent areas under CC scenarios under (a) S1, (b) S2, (c) S3 and (d) S4.

Figure 12.

Compound flooding events, inundation depth, maximum water level variations and flood extent areas under CC scenarios under (a) S1, (b) S2, (c) S3 and (d) S4.

Under the extreme climate change scenario of RCP 8.5 for 2090, modelling suggests inundation areas of 25% (S5), as illustrated in Figure 27. Due to the compounding effects, an additional 7% of the area is expected to be affected by future flooding compared to the CC S1 scenario. In addition, the maximum water level ranges from 0 to 5.6 m (S5). Under this climate change scenario, the observed inundation depth increased by 28% compared to the CC S1 scenarios. As a result of climate change, the maximum water level variation has expanded from the creek to urban areas, reaching up to 80 m on either side of the Saltwater Creek corridor.

Figure 13.

Compound flooding events, inundation depth, maximum water level variations and flood extent area under future climate scenarios (RCP 8.5 2090).

Figure 13.

Compound flooding events, inundation depth, maximum water level variations and flood extent area under future climate scenarios (RCP 8.5 2090).

The flooding hotspots are primarily concentrated in low-lying areas of the study sites, specifically those at an elevation of <4 m AHD. The eastern sub-catchments are continuously flooded under most of the compound scenarios tested for this study. However, localized flooding hotspots due to overland flooding were also observed at the northern, south-western and western upstream urban and road areas. Most of these hotspots were due to the hydraulic insufficiency of grey measures such as inlets, pipes, manholes and culverts. Most culverts experience high overflow, inundating roadside areas and contributing to floods that propagate to the nearest urban area.

The central part of the catchment experienced minimal flooding. This may be due to well-drained steeper topography, which will likely reduce maximum overland flow and flood inundation. However, with the presence of several inlets, the pipe network in this catchment allows the flow to occur in both directions (forward and backwards) depending on the hydraulic gradient. On the other hand, the tailwater level difference at the outlet location of the pipe networks determines the outflow or inflow conditions from the pipe network to the natural drainage. Low tailwater conditions can enhance the effectiveness of grey measures that intercept runoff from roadside and urban areas, which are then discharged into creeks and support downstream flow, thereby reducing the likelihood of overland flooding. In contrast, if the tailwater level is high, flow from the pipe outlet is constrained, leading to higher surface runoff and an increase in either the inundation depth or the flood extent area. The numerous outlets in an urban area can therefore have a ripple effect, transferring flooding conditions to different catchment locations, even farther from the actual sources. This study utilised interpolated data, referencing the outlet water level data from the council sensor, to determine tailwater condition. The lack of precise tailwater levels for the pipe network outlet locations likely impacted the flooding results in the mid-catchment of this study. The tailwater level of the pipe network outlet controls the runoff interception and transportation mechanism through inlets and the pipe network.

3.3.2. Velocity Alterations

Velocity is the least discussed parameter in analyses such as those performed for this study [

44], due to its high computational demands. However, it can provide valuable insights into the kinetic energy associated with the flow and the potential damage caused by moving water. This information is crucial for evaluating flood hazards and developing effective flood mitigation strategies, including inlets, pipe networks, culverts, and bridges.

The maximum velocity alteration under S1 during CC scenarios is presented in

Figure 14. A velocity of 0.3 m/s was adopted as the minimum value for all scenarios. The velocities range from 0.3 to 4 m/s; however, the variation in velocity depends on the sources of combining factors that govern the flow conditions. The minimal velocity variation was observed during scenario 3, while scenario 1 showed maximum velocity variations.

The extreme velocity values were concentrated along the central line of the flow path, specifically within the creek itself. The maximum velocity, observed at approximately 4 m/s, was recorded in the uppermost part of the catchment, correlated with the steepest elevation gradient in the catchment. However, the southern and northern sub-catchments, near the outlet of the concrete drain, also experienced high velocities. Although these sub-catchments do not undergo significant slope changes, the runoff discharged to the concrete channel from the pipe network exhibited a high velocity. In contrast, the low-lying area near the main catchment channel and the overland flow experienced minimal velocities.

The maximum velocity alteration from S5 during future climate change scenarios is presented in

Figure 15. The velocity ranges from 0.3 to 4 m/s, depending on the combination of factors governing the flow conditions. The maximum velocity alteration under climate change scenarios was observed during S5, with an extended area experiencing higher velocity within the catchment.

Maximum alterations in velocity were observed at the outlet location of the pipe network connecting the creek and the overland flow. Additionally, drainage locations, such as the entry and exit points of culverts, also exhibited the maximum alteration in flow velocity. This information can provide valuable insights into the condition of the pipe or drainage flow. Generally, piped flow can increase peak flow at the downstream or outlet location, potentially resulting in flash flooding. The flow velocity data from the drainage network can be used to evaluate the safety of structures against the kinetic force associated with the flow.

Under RCP 8.5 2090 scenarios, the number of locations within the catchment experience maximum velocity compared to S1 scenarios. The north side and south downstream locations experienced maximum velocities, despite topography limiting the flow velocity under the RCP 8.5 2090 scenario. Maximum velocities exceeding 4 m/s at these locations can sweep away humans, vehicles, and buildings. In addition to the inundation in the low-lying areas of this catchment, the risk of high velocity is another critical aspect.

4. Discussion

This study aims to understand the scale and impact of compound flooding events governed by extreme rainfall, tidal level, and sea level rise under current and future climate scenarios at this study site.

4.1. Accuracy of Modelling Results

The results generated by the MIKE+ 1D2D hydrodynamic model and presented above were compared with regional modelling results from [

45]. The observational comparative assessment of 1% AEP results from the MIKE+ model maps and the baseline inundation maps reveals several areas of agreement with known flood hotspots and inundated areas within the catchments. Model calibration and validation are fundamental steps to ensure that the simulated flow of the model falls within the error limit. However, several uncertainties associated with the model setup, flow data, rating curve data, and rainfall impact this process.

This study utilised water level, rainfall, and tidal level data for flood model calibration and validation, which spanned only six years. The rating curve for converting water level data was based on five events. Although the data period is short, the current model has utilised the best available data to establish a model that accurately represents the condition of this catchment compared to the regional model. Thus, the regional model may have a higher probability of overestimating the flood extent area compared to the results of this study, as the regional model has overgeneralized the parameters adopted for hydrodynamic modelling.

4.2. Compounding Modelling: Philosophical to Practical Approach

Compound events lack complete philosophical consistency; different agencies and guidelines have defined such events in different ways, which limits understanding and application [

8]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has defined it as a combination of two or more (not necessarily extreme) weather or climate events that occur at the same time or in close succession or concurrently in different regions [

46]. However, in the Australian context, the precise definition is more limited; ARR defines a compound event as a coincidence of fluvial (rainfall-runoff) and coastal(storm-tide) extremes [

47,

48]. UK guidelines typically model individual types of flooding, such as river, pluvial, and coastal flooding. However, Scottish guidelines suggest using the fluvial /coastal method for combined pluvial and coastal flooding [

49].

Through practical modelling work, several approaches have been adopted to develop a compound modelling approach. These methods include event-based simulation, i.e. simulating historical extreme events, probabilistic (joint statistical method), hybrid frameworks (statistical sampling and numerical modelling), and a fully coupled model able to solve hydrology and ocean dynamics simultaneously [

7,

8,

9,

18,

19,

50,

51,

52]. Compound flood modelling is a complex process, particularly for locations with limited data, which can result in scale mismatches and statistical uncertainty. Although ARR provides a formal method for coastal compound floods for the Australian context, its application depends on local conditions, such as catchment size, flood types, and data availability.

Therefore, there is a critical need for a comprehensive understanding of compound flooding events and to establish consistency in their philosophical and practical modelling approaches. The current study adopted a multivariate scenario-based approach, utilising a 1D2D hydrodynamic coupled model driven by rainfall (from major to minor events), resulting in pluvial flooding, with additional data for 2D surface flow, river routing, high and low tides, and urban drainage systems. This approach provided an advantage in detailing the interaction between different flow domains, including flood maps with flood depth, velocity, duration, and extent, as well as scenario combinations. However, this method requires significant data for model setup, a time-consuming process for calibration and validation. Coupling the 1D and 2D geometries is a challenging aspect of this approach. The approach likely includes minor errors in setting boundary conditions, which can propagate and affect numerical stability, resulting in a significant reduction in model accuracy over time. Statistical joint probability methods of compound flooding modelling were not adopted during this study due to its short data period (6 years), which can result in high statistical uncertainty, leading to underestimation of extremes and unstable fits [

53,

54].

4.3. Compounding Effect

The results presented here have several implications, including for the efficacy of existing flood mitigation measures, the future need for flood mitigation measures, decision-making processes for selecting mitigation approaches, and investment decisions. Each year, flooding events affect numerous locations in this catchment, and complete mitigation of the flooding problem is impractical. However, being prepared, informed, and proactive during such events is essential to minimise the risk of flooding and associated economic and human losses.

The existing grey measures intercept runoff and often function under pressured flow conditions during major events, increasing the discharge rate at the outlet. This can lead to flash flooding at downstream locations. Besides increasing the severity of such events, grey measures can also increase flood risk at the upstream end of the catchments. Grey measures are designed to enable flow in the downstream direction but can also induce backflow, depending on the tailwater conditions. During compound flooding events, the higher water levels at the outlet locations reduce the functionality of inlets, propagating pluvial flooding. Specifically, major rainfall events combined with king tides can result in excessive economic losses due to inundation and damage to vehicles and homes.

Low-lying urban areas are critically exposed to flood risks in the study catchment. This flooding generally has a low flow rate but a high water depth, resulting in an inundation problem. Notably, areas with minimal gradient and locations with backflow, such as those experiencing tidal flow, frequently encounter these problems. On the other hand, the low-lying areas with constrained drainage capacity still experienced high-velocity flow. However, upstream locations of this catchment have a high-velocity flow flood risk associated with it, driven by steep gradients. Although the upstream locations of this catchment's topography do not support inundation, high flow velocities are predicted at such locations. High-velocity flow can sweep away vehicles, houses, infrastructure, and humans, as well as scour the soil along its path.

The results, such as maximum water level variation and maximum velocity, discussed in this research, have significant implications for risk assessment. Most flood studies primarily focus on inundation depth when talking about flood risk. However, this is insufficient to holistically assess flood risk because it does not account for the complexity of flooding within the catchment and the energy associated with the flow. Therefore, to minimise such problems, the related velocity must also be considered in the coming days. Thus, flood mitigation approaches also need to be thought out in a way that reduces both inundation and velocity during the flooding period.

Besides flood mitigation, grey measures such as inlets, manholes, and culverts are critical locations for propagating the flooding problem within a catchment. Such locations are potentially compromised by uncertainty in their effectiveness for flow interception and conveyance under climate change. Such infrastructure requires continuous improvement in hydraulic capacity, which can be achieved through redesign and rehabilitation. These grey measures can be redesigned by considering the impact of climate change on flood mitigation design [

55,

56]. Based on these results, grey measures can be rehabilitated; however, this is a complex construction activity that is costly and time-consuming. Therefore, an in-depth study should be undertaken before adopting this approach, and possible alternative options should be explored with an economic evaluation before implementing any planning measures.

Grey measures at the study site involved infrastructure that linked water flows and water bodies. Runoff during rainfall events was intercepted by inlets and manholes and transferred to the nearest creeks. This can significantly increase flow in creeks, resulting in fluvial flooding. Pipe network outlets transporting overland flow to the creeks can also push back the flow towards urban areas, such as streets, roads, and nearby buildings, particularly during high tailwater conditions in creeks or during king tides. The projected flooding problem is expected to continue in the future; therefore, understanding the limitations of existing measures and seeking alternative novel technologies, such as nature-based solutions, are key aspects that authorities need to explore. This is particularly the case for the future climate change scenarios, which suggest high uncertainty in the amount of runoff received by the grey measures. Upgrading, adding new, and rehabilitating existing grey measures, which have a fixed capacity to accommodate runoff, might require major expansion at considerable cost.

The added challenges for administrative bodies include the requirement for ongoing and increasing funding and resources to implement and maintain any measures to mitigate flood risk. Besides changes in rainfall, sea level rise and associated increases in flood risk, climate change has other implications for urban heat island effects and droughts. Grey measures do not provide any benefit in mitigating such issues; therefore, multifunctional systems with a holistic view of urban and coastal systems are necessary, such as WSUD.

5. Limitations of the Study

The results obtained from any modelling approaches must take into account methodological constraints and the uncertainties associated with data coverage and quality. This study focused on the number of stressors that influence major flooding in a small wet tropical urban catchment. Climate change impacts rainfall, SLR, tidal rise, and their combined effects have been considered in the simulations. A significant assumption in this modelling lies in using existing land use for current and future climate change. This assumption was made to understand the climate-driven impact of flooding under the existing land use. Urbanisation alterations have several effects associated with changing the microclimate conditions and increasing the area of impervious surfaces, significantly impacting overland flow generation and the increase in inundated regions under future climate change conditions. Thus, further urbanisation can considerably increase the inundated area compared to the current results obtained from the model. An account of future changes other than those in response to climate change has not been included.

Additionally, the drainage network model was accurately configured in terms of its position, types, and sizes of structures, as well as flow directions, based on the data provided by the CRC. Several field visits to the site were also conducted to understand the exact conditions and cross-validate the provided data. However, several input values for these grey measures are missing and were interpolated from the nearest available data. For example, several pipe network invert levels were interpolated, considering the nearest available data. This can also cause flooding problems in specific catchments or localised areas. If more accurate data became available, the results presented in this study might be altered.

Furthermore, the limited availability of high-resolution, long-term data has hindered the few studies conducted in tropical cities regarding compound flood events. However, within the study catchment, the availability of 2021 high-resolution DEM data, drainage networks, advanced computational tools, and powerful computers, along with software such as MIKE+, has contributed to the successful modelling of the complex flooding problem in the study catchment. Nevertheless, the data used in flood modelling (rainfall, tidal, and water levels) only covers six years. Data for constructing the rating curve were available for only five events at the outlet location. This can create additional uncertainty in the results generated by the modelling work. Nevertheless, the modelling approach used here can provide critical information to understand the complexity of flooding risk, which can be further improved and updated as data collection continues. This approach can still yield higher-quality results than an isolated modelling approach for each hydrodynamic phenomenon separately, an approach that has been generally adopted in the past and is still in practice.

6. Conclusions

This study addressed the critical problem of the compound flooding effect of rainfall and SLR in the coastal urban Saltwater Creek catchment. The primary objective of this study was to understand the flooding problem in the Saltwater Creek catchment under both current and future climate change scenarios. The scenario-based MIKE+ hydrodynamic model simulation indicated that this catchment is experiencing compound flooding, which can further inundate an area ranging from 5% to 25% under the RCP 8.5 in 2090. Another significant result obtained from this study was a variation in maximum velocity during the flooding period, ranging from 0.3 to 4 m/s. The results indicate that this catchment experiences two distinct flooding problems, with inundation in the low-lying areas and extreme velocity at the upstream locations. Current findings suggest that existing flood mitigation measures are inadequate to address the flooding challenges, which are projected to increase under climate change. However, the limitations of this study are recognized, including the use of a short record of rainfall, water levels, and tidal levels, which spans only six years. Some drainage data, such as the invert level of the pipe, inlet and tailwater levels at outlet locations, were missing and were completed by interpolating the nearest known values. In conclusion, the compound flooding problem in this catchment is evident and projected to worsen in the future. This necessitates a strategic response, through the integration of novel and robust economic techniques such as WSUD, to mitigate future flooding challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.B.G. and B.J.; Data collection and modelling works, S.B.G.; investigation, S.B.G.; resources, S.B.G., B.J.; data curation, S.B.G.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.G.; writing—review and editing, S.B.G., B.J., R.J.W., and M.B.; review, visualisation; supervision, B.J., R.J.W., and M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of James Cook University and the International Research Training Program (IRTPS-081386F) for funding this research. Additionally, the authors would like to recognise the Cairns Regional Council (PD23041 Saltwater Creek Flood Mitigation Project) and the Queensland Government Department of Environment and Science for funding this project. Furthermore, the authors would also like to thank the Hunter Research Grant [00117J] for providing additional funds to purchase the software tools.

Data Availability Statement

The field data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to acknowledge James Cook University, the Cairns Regional Council, and the Queensland Government Department of Environment, Science, and Innovation for funding this project. Specifically, we would like to thank Iain Brown and David Ryan for providing us with valuable data, reports, and information. The authors would like to acknowledge DHI Australia for providing the student version of the MIKE+ Tool license for research purposes (Student Toolkit). The authors also appreciate the Australian Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) and Queensland’s Long Paddock for crucial data. The authors would also like to thank the Hunter Research Grant for providing additional funds to purchase the software tools. The authors also acknowledge the anonymous reviewers whose comments have improved this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Abbreviations |

Meanings |

Abbreviations |

Meanings |

| SLR |

Sea-level rise |

QGIS |

Quantum Geographic Information System |

| WSUD |

Water Sensitive Urban Design |

NSE |

Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency |

| AEP |

Annual Exceedance Probability |

RMSE |

Root Mean Square Error |

| 1D |

1-Dimension |

PBIAS |

Percentage Bias |

| 2D |

2-Dimension |

RSR |

Ratio of the Root Mean Square Error to the Standard Deviation Ratio |

| PF |

Peak flow |

EIA |

Effective impervious area |

| TRV |

Total runoff volume |

FEA |

Flood extent area |

| IPCC |

Intergovernmental panel on climate change |

CA |

Catchment area |

| AHD |

Australian Height Datum |

MWL |

Maximum water level |

| CRC |

Cairns Regional Council |

IL |

Initial Loss |

| BOM |

Australian Bureau of Meteorology |

CL |

Continuous loss |

| DEM |

Digital Elevations Model |

WBNM |

Watershed Bounded Network Model |

| IDW |

Inverse Distance Weighting |

URBS |

Unified River Basin Simulator |

| ARR |

Australian Rainfall and Runoff |

HEC-HMS |

Hydrologic Engineering Centre-Hydrologic Modelling System |

| ATP |

Areal temporal patterns |

XP-RAFTS |

XP-Rainfall-Runoff Analysis Forecasting Tool for Stormwater |

| ARF |

Areal reduction factors |

RCPs |

Representative concentration pathways |

| IFD |

Intensity Frequency Duration |

DCIA |

Directly connected impervious Area |

| RORB |

Runoff-routing |

ICIA |

Indirectly connected impervious Area |

| DHI |

Danish Hydraulic Institute |

TIA |

Total Impervious Area |

| CS |

Collection system |

ICCF |

Interim Climate Change factors |

| GIS |

Geographic Information System |

CC |

Current Climate |

References

- Allaire, M. Socio-economic impacts of flooding: A review of the empirical literature. 2018, 3, 18-26. [CrossRef]

- Dottori, F.; Szewczyk, W.; Ciscar, J.C.; Zhao, F.; Alfieri, L.; Hirabayashi, Y.; Bianchi, A.; Mongelli, I.; Frieler, K.; Betts, R.A.; et al. Increased human and economic losses from river flooding with anthropogenic warming. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8(9), 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirezci, E.; Young, I.R.; Ranasinghe, R.; Lincke, D.; Hinkel, J. Global-scale analysis of socioeconomic impacts of coastal flooding over the 21st century. Frontiers in Marine Science 2023, 9, 1024111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Climate change 2021: The physical science basis summary for policymakers; 2021; pp. 1-42.

- Hooijer, A.; Vernimmen, R. Global LiDAR land elevation data reveal greatest sea-level rise vulnerability in the tropics. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, H.; Downes, N.K. A scenario-based approach to assess Ho Chi Minh City's urban development strategies against the impact of climate change. Cities 2011, 28, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Najafi, M.R. Probabilistic Numerical Modeling of Compound Flooding Caused by Tropical Storm Matthew Over a Data-Scarce Coastal Environment. Water Resources Research 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Haigh, I.D.; Quinn, N.; Neal, J.; Wahl, T.; Wood, M.; Eilander, D.; de Ruiter, M.; Ward, P.; Camus, P. Review article: A comprehensive review of compound flooding literature with a focus on coastal and estuarine regions. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2025, 25, 747–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, M.; Arabi, M.; Kao, S.C.; Obeysekera, J.; Sweet, W. Climate Change and Changes in Compound Coastal-Riverine Flooding Hazard Along the U.S. Coasts. Earth's Future 2021, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, D.S.; Chatterjee, C.; Kalakoti, S.; Upadhyay, P.; Sahoo, M.; Panda, A. Modeling urban floods and drainage using SWMM and MIKE URBAN: a case study. Natural Hazards 2016, 84, 749–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, D.; Luo, P.; Lyu, J.; Zhou, M.; Huo, A.; Duan, W.; Nover, D.; He, B.; Zhao, X. Impact of temporal rainfall patterns on flash floods in Hue City, Vietnam. Journal of Flood Risk Management 2021, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.; Karmakar, S.; Ghosh, S.; Aliaga, D.G.; Niyogi, D. Impact of green roofs on heavy rainfall in tropical, coastal urban area. Environmental Research Letters 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Gu, X.; Shi, P.; Singh, V.P. Impact of tropical cyclones on flood risk in southeastern China: Spatial patterns, causes and implications. Global and Planetary Change 2017, 150, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevacqua, E.; Vousdoukas, M.I.; Zappa, G.; Hodges, K.; Shepherd, T.G.; Maraun, D.; Mentaschi, L.; Feyen, L. More meteorological events that drive compound coastal flooding are projected under climate change. Communications Earth & Environment 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A.; Lin, N.; Smith, J. Assessing Compound Flooding From Landfalling Tropical Cyclones on the North Carolina Coast. Water Resources Research 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koochaksarali, H.B. Compound Flooding in Coastal Areas Emanating From Inland and Offshore Events. 2020.

- Leijnse, T.; van Ormondt, M.; Nederhoff, K.; van Dongeren, A. Modeling compound flooding in coastal systems using a computationally efficient reduced-physics solver: Including fluvial, pluvial, tidal, wind- and wave-driven processes. Coastal Engineering 2021, 163, 103796–103796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moftakhari, H.R.; Salvadori, G.; AghaKouchak, A.; Sanders, B.F.; Matthew, R.A. Compounding effects of sea level rise and fluvial flooding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2017, 114, 9785–9790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drews, M.; Schröter, K.; Wortmann, M.; Larsen, M.A.D. Compound risk of extreme pluvial and fluvial floods. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Collazo, F.L.; Bilskie, M.V.; Hagen, S.C. A comprehensive review of compound inundation models in low-gradient coastal watersheds. Environmental Modelling and Software 2019, 119, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieken, A.H.; Samprogna Mohor, G.; Kreibich, H.; Müller, M. Compound inland flood events: Different pathways, different impacts and different coping options. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2022, 22, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridder, N.N.; Pitman, A.J.; Westra, S.; Ukkola, A.; Hong, X.D.; Bador, M.; Hirsch, A.L.; Evans, J.P.; Di Luca, A.; Zscheischler, J. Global hotspots for the occurrence of compound events. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/averages/tables/cw_031011.shtml. Available online: (accessed on 12/08).

- https://www.data.qld.gov.au/dataset/cairns-tide-gauge-predicted-interval-data. Available online: (accessed on 8/12).

- Brown, I.W.; McDougall, K.; Alam, M.J.; Chowdhury, R.; Chadalavada, S. Calibration of a continuous hydrologic simulation model in the urban Gowrie Creek catchment in Toowoomba, Australia. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 2022, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, L.; Lim, H.; Brown, I.; Huang, T.; Munksgaard, N.C.; Randall, M.; Holdsworth, J.; Cook, H. Innovation Through Collaboration. Water e-Journal 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.swoffer.com/. Available online: (accessed on 8/9).

-

Australian Rainfall Runoff Revision Project 3: Temporal Patterns of Rainfall - Stage 3 report; 2015; p. 62.

- https://qldglobe.information.qld.gov.au/. Available online: (accessed on 2024).

- Boyd, M.J.; Bufill, M.C.; Knee, R.M. Pervious and impervious runoff in urban catchments. Hydrological Sciences Journal 1993, 38, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimian, A.; Wilson, B.N.; Gulliver, J.S. Improved methods to estimate the effective impervious area in urban catchments using rainfall-runoff data. Journal of Hydrology 2016, 536, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://geoscience.data.qld.gov.au/data/map-collection/mr002086. Available online: (accessed on 16 October).

- https://www.longpaddock.qld.gov.au/qld-future-climate/dashboard/#responseTab1. Available online: (accessed on 2023).

- Gurung, S.B.; Wasson, R.J.; Bird, M.; Jarihani, B. Impact of Climate Change on Water-Sensitive Urban Design Performances on Mitigating Urban Flooding in the Wet Tropical Queensland Sub-Catchment. Earth 2025. [Google Scholar]

- https://harc.com.au/software/rorb/. Available online: (accessed on 5/8).

- Laurenson, E.M.; Mein, R.G.; Nathan, R.J. User Manual of RORB Runoff Routing Program, Version 6 Department of Civil Engineering, Monash University, Australia: 2010.

-

MIKE 2022 MIKE+ User Guide Model Manager; 2022.

-

MIKE Flood 1D-2D Modelling User Manual; 2017; pp. 1-160.

- https://www.dhigroup.com. Available online: (accessed on 6/6).

- Haghighatafshar, S.; Nordlöf, B.; Roldin, M.; Gustafsson, L.G.; la Cour Jansen, J.; Jönsson, K. Efficiency of blue-green stormwater retrofits for flood mitigation – Conclusions drawn from a case study in Malmö, Sweden. Journal of Environmental Management 2018, 207, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://csse.com.au/index.php/products/storm-injector. Available online: (accessed on 8/8).

- Ball J.E., B.M.N.R.W.W.W.E.R.M.T.I. A Guide to Flood Estimation -A Guide to Flood Estimation Book; 9781925848366; 2019; pp. 187-187.

- Althoff, D.; Rodrigues, L.N. Goodness-of-fit criteria for hydrological models: Model calibration and performance assessment. Journal of Hydrology 2021, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Zhou, X. Impact of Tides and Surges on Fluvial Floods in Coastal Regions. Remote Sensing 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://floodcheck.information.qld.gov.au/. Available online: (accessed on 12/8).

- Seneviratne, S.I., X. Zhang, M. Adnan, W. Badi, C. Dereczynski, A. Di Luca, S. Ghosh, I. Iskandar, J. Kossin, S. Lewis,; F. Otto, I.P., M. Satoh, S.M. Vicente-Serrano, M. Wehner, and B. Zhou. Chapter 11: Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate:The Physical Science Basis; 2021; pp. pp. 1513–1766.

- Zheng, F.; Westra, S.; Leonard, M. REVISION PROJECT 18: Coincidence of Fluvial Flooding Events and Coastal Water Levers in Estuarine Areas; 2014.

- Westra, S. Revision Project 18: Interaction of Coastal Processes and Severe Weather Events. 2012.

-

Flood Modelling Guidance for Responsible Authorities,Version 1.1; 2017.

- Couasnon, A.; Eilander, D.; Muis, S.; Veldkamp, T.I.E.; Haigh, I.D.; Wahl, T.; Winsemius, H.C.; Ward, P.J. Measuring compound flood potential from river discharge and storm surge extremes at the global scale. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2020, 20, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevacqua, E.; De Michele, C.; Manning, C.; Couasnon, A.; Ribeiro, A.F.S.; Ramos, A.M.; Vignotto, E.; Bastos, A.; Blesić, S.; Durante, F.; et al. Guidelines for Studying Diverse Types of Compound Weather and Climate Events. Earth's Future 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Tian, Z.; Sun, L.; Ye, Q.; Ragno, E.; Bricker, J.; Mao, G.; Tan, J.; Wang, J.; Ke, Q.; et al. Compound flood impact of water level and rainfall during tropical cyclone periods in a coastal city: the case of Shanghai. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2022, 22, 2347–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuele Bevacqua, D.M. Ingrid Hobæk Haff, Martin Widmann, and Mathieu Vrac. Multivariate statistical modelling of compound events via pair-copula constructions: analysis of floods in Ravenna (Italy). 2017.

- ThomasWahl, S.J., Jens Bender, Steven D. Meyers and Mark E. Luther. Increasing risk of compound flooding from storm surge and rainfall for major US cities. 2015.

- Ball, J.E., Babister, M. K., Nathan, R., Weinmann, P. E., Weeks, W., Retallick, M., & Testoni, I. Australian Rainfall & Runoff Book 1: A Guide to Flood Estimation; 2019.

- Coombes, P.; Roso, S. A Guide To Flood Estimation: Book 9 Runoff in Urban Areas; 2019; pp. 184-184.

Figure 1.

Saltwater Creek catchment (study site) in Cairns City, Queensland, Australia, including the drainage network and digital elevation model, with key features shown.

Figure 1.

Saltwater Creek catchment (study site) in Cairns City, Queensland, Australia, including the drainage network and digital elevation model, with key features shown.

Figure 2.

Rain gauge, tidal gauge station, pressure transducer at the outlet and drainage network within the Saltwater Creek study site.

Figure 2.

Rain gauge, tidal gauge station, pressure transducer at the outlet and drainage network within the Saltwater Creek study site.

Figure 3.

Water level time series measured by pressure transducer sensor at the Greenslopes Street Bridge site, Saltwater Creek catchment outlet.

Figure 3.

Water level time series measured by pressure transducer sensor at the Greenslopes Street Bridge site, Saltwater Creek catchment outlet.

Figure 4.

Rating curve for Saltwater Creek at Greenslopes Street Bridge Outlet for rainfall runoff flow only.

Figure 4.

Rating curve for Saltwater Creek at Greenslopes Street Bridge Outlet for rainfall runoff flow only.

Figure 5.

IFD design rainfall intensity (mm/h) for Saltwater Creek catchment.

Figure 5.

IFD design rainfall intensity (mm/h) for Saltwater Creek catchment.

Figure 6.

Land use/land cover map of the Saltwater Creek catchment.

Figure 6.

Land use/land cover map of the Saltwater Creek catchment.

Figure 7.

Natural and existing man-made channels and existing pipe network, inlets, manholes, culverts and grey measures in the Saltwater Creek catchment.

Figure 7.

Natural and existing man-made channels and existing pipe network, inlets, manholes, culverts and grey measures in the Saltwater Creek catchment.

Figure 8.

Calculated interim climate change factors (ICCF) based on the temperature data from Long Paddock for the Saltwater Creek catchment used for simulating climate change impact.

Figure 8.

Calculated interim climate change factors (ICCF) based on the temperature data from Long Paddock for the Saltwater Creek catchment used for simulating climate change impact.

Figure 9.

Flood modelling approach and steps flow chart.

Figure 9.

Flood modelling approach and steps flow chart.

Figure 10.

Saltwater Creek RORB catchment (.cat) file setup with key features.

Figure 10.

Saltwater Creek RORB catchment (.cat) file setup with key features.

Figure 11.

Schematic setup of the MIKE+ model (modified and adapted from [

40]).

Figure 11.

Schematic setup of the MIKE+ model (modified and adapted from [

40]).

Figure 14.

Compound flooding events, maximum velocity variations under CC (a) S1.

Figure 14.

Compound flooding events, maximum velocity variations under CC (a) S1.

Figure 15.

Compound flooding events, maximum velocity variations under future climate change (RCP 8.5 2090) scenario (S5).

Figure 15.

Compound flooding events, maximum velocity variations under future climate change (RCP 8.5 2090) scenario (S5).

Table 1.

Rainfall event characteristics adopted for model calibration and validation.

Table 1.

Rainfall event characteristics adopted for model calibration and validation.

| Events |

Types |

Rainfall Depth (mm) |

Rainfall Duration (Hours) |

Peak flow (m3/s) |

Remarks |

| Calibration Events |

|

| 29/01/2020 |

Major |

154 |

21 |

46 |

|

| 17/12/2023 |

Major |

472 |

81 |

56 |

Tropical Cyclone Jasper 13-18, 2023 |

| 04/04/2019 |

Moderate |

138 |

30 |

30 |

|

| 13/01/2024 |

Moderate |

71 |

17 |

24 |

|

| 28/01/2020 |

Minor |

32 |

16 |

9 |

|

| 27/02/2020 |

Minor |

59 |

15 |

18 |

|

| Validation Events |

|

| 24/03/2021 |

Major |

110 |

24 |

51 |

Tropical Cyclone Niran |

| 25/02/2020 |

Moderate |

57 |

14 |

29 |

|

| 22/02/2020 |

Minor |

56 |

14 |

16 |

|

Table 2.

MIKE+ model simulation scenario combinations.

Table 2.

MIKE+ model simulation scenario combinations.

| Scenarios |

Descriptions |

| Hydrological Simulation Scenarios |

| Rainfall |

Major, Moderate and Minor |

| Climate Change |

Current Climate (CC) and RCP 8.5 |

| Hydrodynamic Simulation Scenarios |

| Scenario 1 (S1) |

Major rainfall design event under CC + High astronomical event time series (measured tidal time series) |

| Scenario 5 (S5) |

Major rainfall design event RCP 8.5 2090 + High astronomical tidal event time series (measured time series) + SLR (80 cm) + Surge value (20 cm) |

Table 3.

RORB and MIKE+ hydrological model calibration and validation results.

Table 3.

RORB and MIKE+ hydrological model calibration and validation results.

| RORB/MIKE+ Model Calibration Results |

| Events |

Type |

PF Error, m3/s |

NSE |

RMSE |

R2

|

RSR |

| RORB |

MIKE+ |

RORB |

MIKE+ |

RORB |

MIKE+ |

RORB |

MIKE+ |

RORB |

MIKE+ |

| 29/01/2020 |

Major |

0.00 |

-0.07 |

0.79 |

0.85 |

7.01 |

5.9 |

0.89 |

0.95 |

0.46 |

0.39 |

| 17/12/2023 |

Major |

2.98 |

-0.03 |

0.81 |

0.76 |

8.52 |

9.5 |

0.91 |

0.93 |

0.44 |

0.49 |

| 04/04/2019 |

Moderate |

5.14 |

-0.04 |

0.78 |

0.73 |

3.85 |

5.8 |

0.89 |

0.89 |

0.48 |

0.7 |

| 13/01/2024 |

Moderate |

3.65 |

-0.01 |

0.77 |

0.89 |

3.37 |

2.4 |

0.91 |

0.96 |

0.56 |

0.34 |

| 28/01/2020 |

Minor |

1.33 |

0 |

0.77 |

0.5 |

1.38 |

2.1 |

0.89 |

0.83 |

0.48 |

0.71 |

| 27/02/2020 |

Minor |

0.48 |

0 |

0.59 |

0.92 |

2.77 |

1.6 |

0.92 |

0.94 |

0.94 |

0.37 |

| RORB/MIKE+ Model Validation Results |

| 24/03/2021 |

Major |

-0.43 |

-0.04 |

0.95 |

0.8 |

2.9 |

6.1 |

0.98 |

0.93 |

0.22 |

0.44 |

| 25/02/2020 |

Moderate |

4.65 |

-0.022 |

0.75 |

0.85 |

4.1 |

3.2 |

0.90 |

0.96 |

0.5 |

0.39 |

| 22/02/2020 |

Minor |

3.69 |

-0.27 |

0.73 |

0.57 |

2.9 |

3.6 |

0.89 |

0.9 |

0.52 |

0.66 |

Table 4.

Rainfall and peak flow alteration for design events using the MIKE+ hydrological model.

Table 4.

Rainfall and peak flow alteration for design events using the MIKE+ hydrological model.

| Scenarios |

Total Rainfall Depth (mm) |

| Minor |

Moderate |

Major |

| CC |

86 |

136 |

334 |

| RCP 8.5 2090 |

106 |

159 |

390 |

| |

Peak Flow (m3/s) |

| CC |

35 |

54 |

99 |

| RCP 8.5 2090 |

42 |

67 |

125 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).