1. Introduction

The traditional beer markets are thriving, and brewers aim to meet emerging consumer trends [

1]. Although the NAB market was valued at

$36.7 billion, it represents only 4.3% of global beer production [

2]. Rising interest in healthier foods has led to functional beers, such as probiotic or gluten-free options [

3]. The probiotic market, worth

$61.2 billion in 2021, is projected to grow by 7.7% by 2030 [

4]. Beverages as functional matrices are becoming more common, yet adding probiotics to beer is challenging due to its harsh environment [

5]. Consumers increasingly prefer beers with lowered ethanol content aligned with healthier lifestyle [

6], while breweries preserve capital from lower tax burdens [

7]. According to EU Regulation 1169/2011, beverages over 1.2% vol. are alcoholic, but most countries define NAB as ≤0.5% vol. [

8]. NAB can be made by limiting ethanol during fermentation or removing it post-production, but this can cause off-flavours and aroma loss [

9,

10]. Use of non-maltose fermenting yeasts helped improve NAB sensory qualities [

10,

11,

12].

Probiotics are live microorganisms with health benefits when consumed in sufficient amounts [

13]. As ethanol is a drug, probiotic beers should be alcohol-free [

14]. Labels may state CFU levels, but high counts don’t always mean better health effects [

15]. Probiotics can colonize the gut, compete with pathogens, and produce beneficial compounds [

16]. Though only few probiotic yeasts (PYs), like

Saccharomyces boulardii or

Kluyveromyces fragilis B0399, are used, other genera also show probiotic potential, including tolerance to low pH, bile salts, and antimicrobial activity [

17].

S. boulardii, a GRAS organism [

18], is a subtype of

S. cerevisiae and produces ethanol, CO₂, and bioactives like GABA (

γ-aminobutyric acid) and B vitamins [

19].

K. lactis, studied since the 1960s [

20], ferments lactose using LAC12 and LAC4 genes [

21] and can produce ethanol even anaerobically [

22].

K. marxianus, a thermotolerant, Crabtree-negative yeast, survives at 52 °C and can produce ethanol above 40 °C, but its inability to ferment maltose makes it suitable for NAB [

23].

Pichia manshurica, found in fermented foods and wines, is associated with biofilm and volatile phenol production [

24]. Though never used in beer, it showed survival potential under stress factors [

25] and successfully enhanced vinegar aroma profile in one study [

26].

This study applies S. boulardii, K. lactis, K. marxianus, and P. manshurica as sole fermentation cultures in functional NAB production. Results support the concept of using probiotic yeasts to develop next-generation health-promoting beverages.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast Strains

Yeast strains used in this study (

Table 1) were maintained on YPDA medium [10 g.L

-1 yeast extract (Oxoid, ThermoFisher Scientific, USA), 10 g.L

-1 peptone (Thermo Scientific™, USA), 20 g.L

-1 glucose (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and g.L

-1 agar (Carl Roth, GmbH, Germany), pH 6.2] and stored at 4 °C.

2.2. Preparation of Yeast Starters

Yeast starters used in experiments were prepared by 24h submerse cultivation of individual yeast strains in liquid YPD medium (10 g.L -1 yeast extract, 20 g.L -1 glucose, 10 g.L -1 peptone (Thermo Scientific™, USA) pH 6.2; 20 ml in 100 ml Erlenmeyer flasks) on an orbital shaker (Biosan ES-20, Riga, Latvia) at 2 Hz, 28 °C.

2.3. Fermentation of Saccharides

The ability of yeast strains to ferment saccharides (glucose, maltose, lactose) was tested as previously described by [

27] in glass tubes containing inverted Durham tubes. Production of CO

2 indicating the saccharide fermentation was evaluated after 7-day static cultivation at 25 °C. Experiments were performed in triplicates.

2.4. ß-Glucosidase Activity

Yeast strains with positive ß-glucosidase activity are capable of hydrolyzing aesculin as the sole carbon source to glucose and aesculetin, which reacts with present iron ions to form a dark compound. Tested yeast strains were inoculated onto plates with medium containing: aesculin 1.0 g.L -1 (Fisher Scientific, USA), iron (III) citrate 3-hydrate (Acros Organics®, USA), 0.5 g.L -1, yeast extract 8.0 g.L -1, agar 15 g.L -1, and were incubated for 24h at 25 °C. The intensity of ß-glucosidase activity was evaluated based on the formation of the dark zone and the intensity of diffusate colouring. Experiments were performed in triplicates.

2.5. Phenolic Off-Flavour (POF) Phenotype

Yeasts capable of decarboxylating ferulic acid, into the formation of 4-vinyl guaiacol (4-VG) which imparts beer with a clove-like aroma, can be characterized by their positive (POF+) or negative (POF-) phenotype. Yeast starters used in experiments were prepared by 24h submerse cultivation of individual yeast strains in liquid YPD medium. For each yeast strain, 20 ml of pure and sterile YPD medium was poured into glass tube with the addition of 0.2 ml of 1% (v/v) ferulic acid solution prepared by adding ferulic acid (Merck, Darmstadt Germany) into 96% (v/v) of ethanol (CentralChem®, Slovakia). Glass tubes were inoculated by the tested yeast strains in triplicates. Tubes were then sealed and statically incubated at 25 °C for 24h. Evaluation was done by six people and was performed by sensorial analysis comparison of glass tubes containing tested yeast strains against controls, where as a positive control (POF+) yeast SafBrew™ LA-01 was used. As a negative control (POF-), yeast LalBrew® LoNa™ was used.

2.6. Tolerances of Different Conditions

To determine sensitivity of strains to different temperature conditions, 1×106 Cells.mL-1 of liquid yeast starters were cultivated at 4 °C, 20 °C and 37 °C for 24h in sterile glass tubes each containing YPD medium.

Sensitivity of strains to different pH (3; 4; 5 and 6) was evaluated by cultivating 1×106 Cells.mL-1 of fresh liquid yeast starter at 37 °C for 24h in sterile glass tubes each containing YPD medium, where pH was adjusted by adding 35% (v/v) of HCl (CentralChem®, Slovakia). Sensitivity of strains to different concentrations of iso-α-bitter acids in terms of IBU (international bitterness unit) (0; 10; 30; and 50) was evaluated by cultivating 1×106 Cells.mL-1 of fresh liquid yeast starter at 25 °C for 24h in sterile glass tubes each containing YPD medium, where IBU units were adjusted by the addition of iso-α-bitter acid solution (Brewferm®).

The tolerance of different temperatures, pH, concentrations and iso-α-bitter acids was evaluated based on the growth of the yeast culture, which was determined by measuring the optical density of the biomass suspension at a wavelength of 600 nm (ΔOD600nm) against pure YPD medium used as a blank. Viability of yeast cells was determined microscopically using the staining with 0.1% (w/w) methylene blue solution. Experiments were performed in triplicates.

2.7. Fermentation and Maturation

For beer production, 480 ml of wort (8°P made from Pilsen malt and Žatecký poloraný červenák hops (Saaz)) prepared in 25 L Laboratory Microbrewery (Braumeister, Speidel, Germany) in 500 ml fermentation PET flasks was inoculated with yeast starters of pitch rate of 1×106 Cells.mL-1. Flasks were closed and fermentation proceeded at 20 °C for 2 days after which maturation proceeded at 3 °C for 3 weeks. Beers were then stabilised by pascalisation procedure at 400 MPa for 3 min. Finally, fermented beer samples were analysed for composition of residual saccharides, organic acids, glycerol, ethanol and profile of main volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Viability of cell cultures in final beer samples was determined after stabilisation procedure. Fermentation experiments were performed in triplicates.

2.8. Beer Analyses

Basic Beer Parameters

Ethanol concentration and pH of beer and wort samples was determined using a density meter DMA 4500M coupled with Alcolyzer Beer ME, Haze QC ME Turbidity Measuring Module and pH ME Beverage Measuring Module (Anton Paar, GmbH, Graz, Austria). Prior to analysis, fermented final beer samples were centrifuged (10 min, 2524 ×g) and degassed by ultrasonication for 30 min and analysed in triplicates.

Organic Compound Analysis by HPLC-RID-DAD

Before HPLC analysis, the samples were centrifuged (10 min, 2511 ×g) and supernatant was diluted with deionized water if needed. Agilent 1260 HPLC system (Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled to RI (refractive index) and DAD (diode array detector) using Aminex HPX-87H column (300 mm, 7.8 mm; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) was used for HPLC measurements. Sulfuric acid (5 mmol.L-1) was used as the mobile phase with the flow-rate of 0.6 mL.min-1. Separation was performed at 25 °C, injection volume was 20 μL. The signal was detected by RID and DAD detectors. Accurate concentrations of glucose, maltose, glycerol, acetic, lactic and citric acid were determined using the single standard addition method. The standards with purity ≥99.5% were obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Beer samples were analysed in triplicates.

Volatile Organic Compound Analysis by HS-SPME-GC-MS

Prior to analysis, beer samples were cooled and stored at 4 °C. 50 mL of each beer sample was centrifuged (10 °C, 5054 ×g, 10 min) and supernatant was poured into 50 mL flask and enclosed. Flasks were shaken for 3 min to remove the CO

2. In the meantime, 2 g of NaCl with (≥99.9% purity, Pentachemicals, Czech Republic) were put into 20 mL dark vial together with 10 mL of beer sample and 100 µL of internal standard (IS) solution, which contained: ethyl heptanoate (≥ 99% purity, Sigma Aldrich, DE) and 3-octanol (≥ 99% purity, Sigma Aldrich, USA). Vial was vortexed for 30s to dissolve the NaCl and homogenise the sample VOCs were identified and quantified according to a method described in [

27]. VOCs of beer samples were analysed in triplicates.

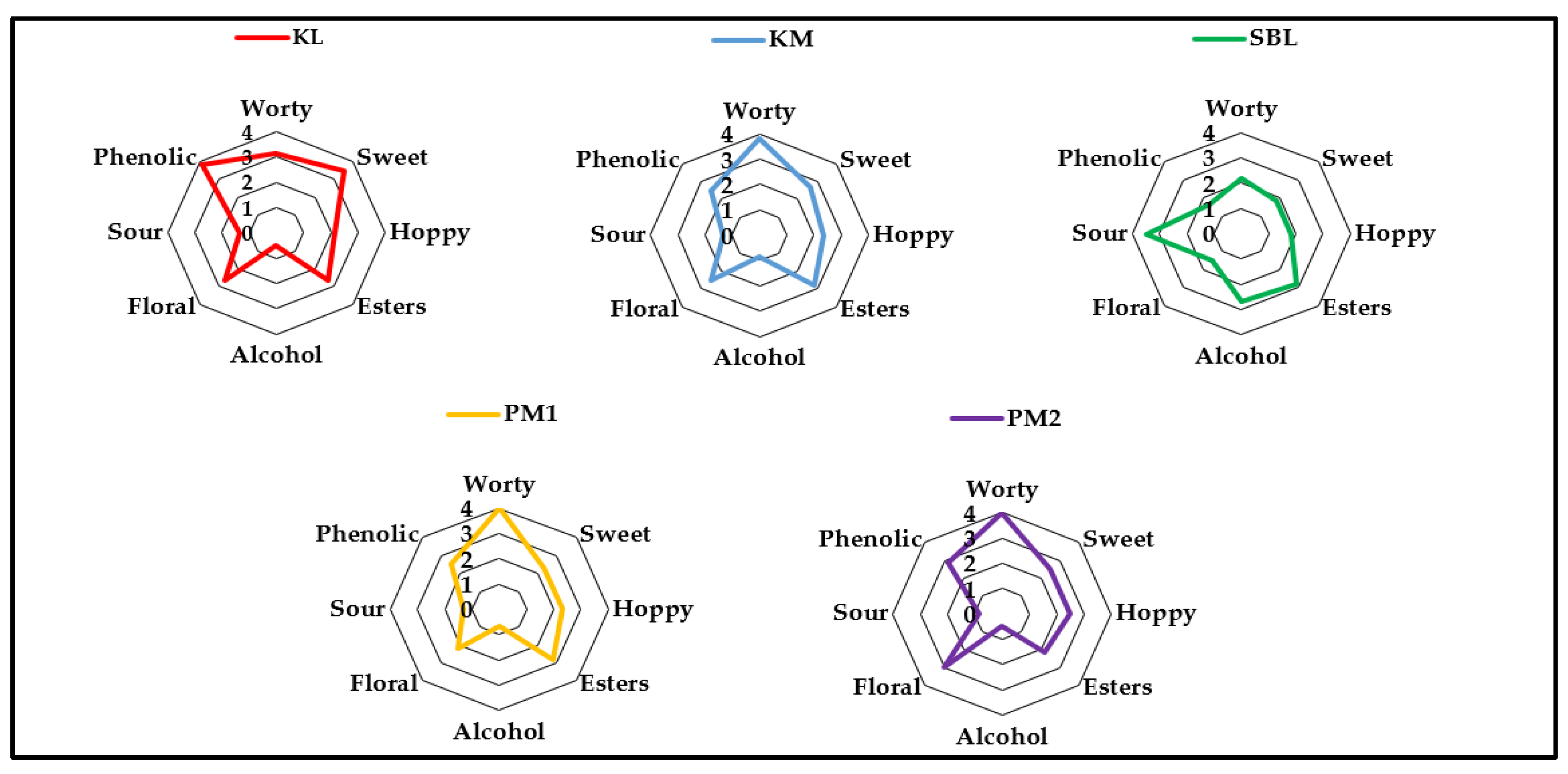

Sensorial Evaluation of Beer Samples

Final beer samples were analysed sensorially by six-person taste panel where attributes of beer aromatic profiles were evaluated and resulting data describing aromatic profile were visualized as a radar chart (aromagram).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Yeast Characterisation

Fermentation tests showed that all strains were able to ferment glucose (

Table 2). Unlike the probiotic strain

S. boulardii, the other four non-

Saccharomyces yeast strains of

Kluyveromyces and

Pichia genus were unable to ferment maltose – the most abundant saccharide in wort (

Table 2) and making them proper candidates for non-alcoholic beer (NAB) production by strategy of using maltose-negative yeast strains [

28]. Potential probiotic strains

K. lactis and

K. marxianus were able to ferment lactose, as was previously confirmed by [

29].

S. boulardii and both yeast strains

P. manshurica have not fermented lactose (

Table 2). Determination of the

ß-glucosidase activity of tested yeasts proved, that both strains of

P. manshurica, as well as

S. boulardii, had weak/delayed

β -glucosidase activity after 24h, whereas

K. lactis and

K. marxianus showed strong

β -glucosidase activity (

Table 2). Several studies have reported that yeasts with increased

β-glucosidase activity play an important role in releasing aromatic aglycones from hops during fermentation [

30] and thus, enhancing aroma complexity of the final beverage. Positive phenolic off-flavour (POF

+) phenotype was sensorially evaluated by the production of clove-like aroma (4-vinyl guaiacol (4-VG)) by all tested yeasts (

Table 2). Besides diacetyl and sulfur compounds, 4-VG is mostly unwanted compound during beer production with the exception of few beer styles e.g. German Hefeweizen and Belgian Wit beers where 4-VG is considered as a part of an aromatic profile [

31]. Even though the tested yeasts were POF

+ they might serve as a fermentation starter culture for brewing specific non-alcoholic wheat beers with clove-like aroma.

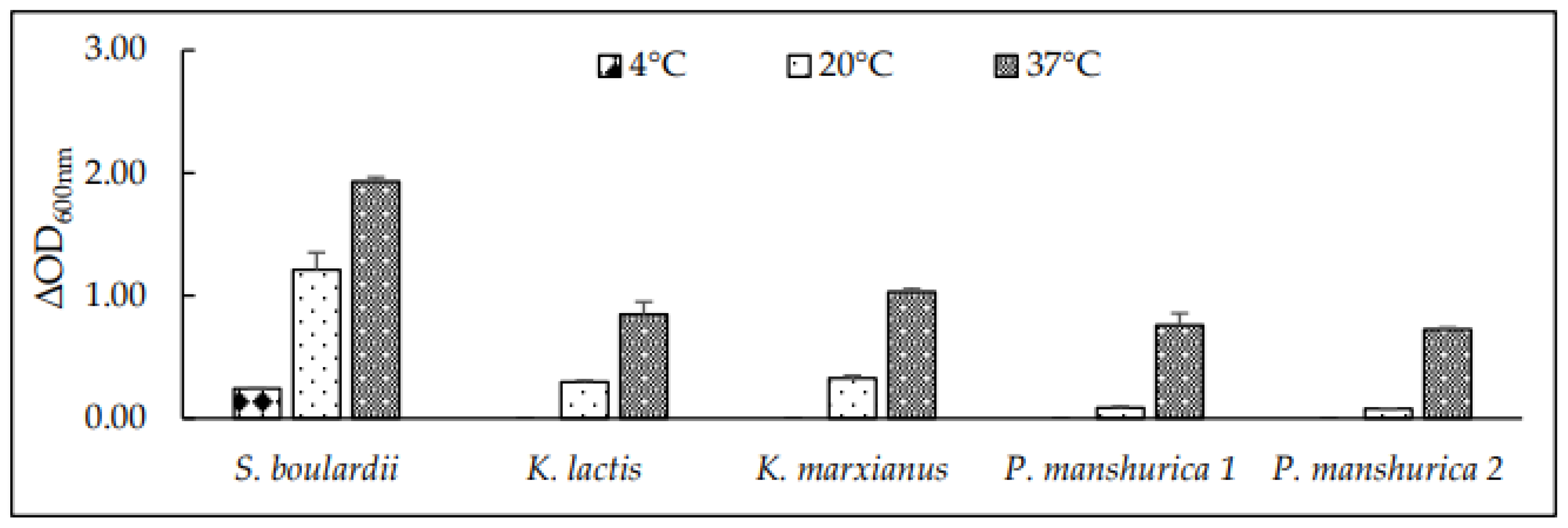

3.2. Tolerance of Different Temperature

Growth of yeast at different temperatures represented as ΔOD

600nm values, showed that the potential probiotic yeasts

Kluyveromyces were unable to grow at 4 °C (

Figure 1), however, the highest growth represented as ΔOD

600nm values were observed in a medium incubated at 37 °C (

Figure 1). According to [

32], the yeast

K. marxianus can withstand 45 °C, but as the human body temperature equals 37 °C, it was not our goal to test growth at ≥37 °C. According to [

33], the optimal growth temperature for the probiotic yeast

S. boulardii is 37 °C. This was supported by our results and

S. boulardii was able to grow sufficiently at whole range of temperatures (

Figure 1). The maturation of beer is performed at temperatures close to 0 °C. Growth of

S. boulardii at low temperatures (4 °C) (

Figure 1) might potentially lead to unexpected fermentation of wort saccharides such as maltose or glucose due to positive fermentability of these saccharides (

Table 2), hence the ethanol limit for NAB production should be maintained. Growth of both

P. manshurica, represented as ΔOD

600nm values was observed at 37 °C (

Figure 1), whereas no growth was observed at 4 °C and minimal at 20 °C. Results supported the suitability of tested yeast to survive the human body temperature. Overall, the highest viability (

Table 3) was determined when cultivating yeast at 37 °C, support the probability of survival of the tested yeasts in a human body gastrointestinal tract. As for the 20 °C which is a temperature in temperature interval used for brewing ale style beers, the viability for both

Kluyveromyces and both

Pichia yeast strains has decreased for more than 10% except for

S. boulardii, which was the most viable yeast strain (97%).

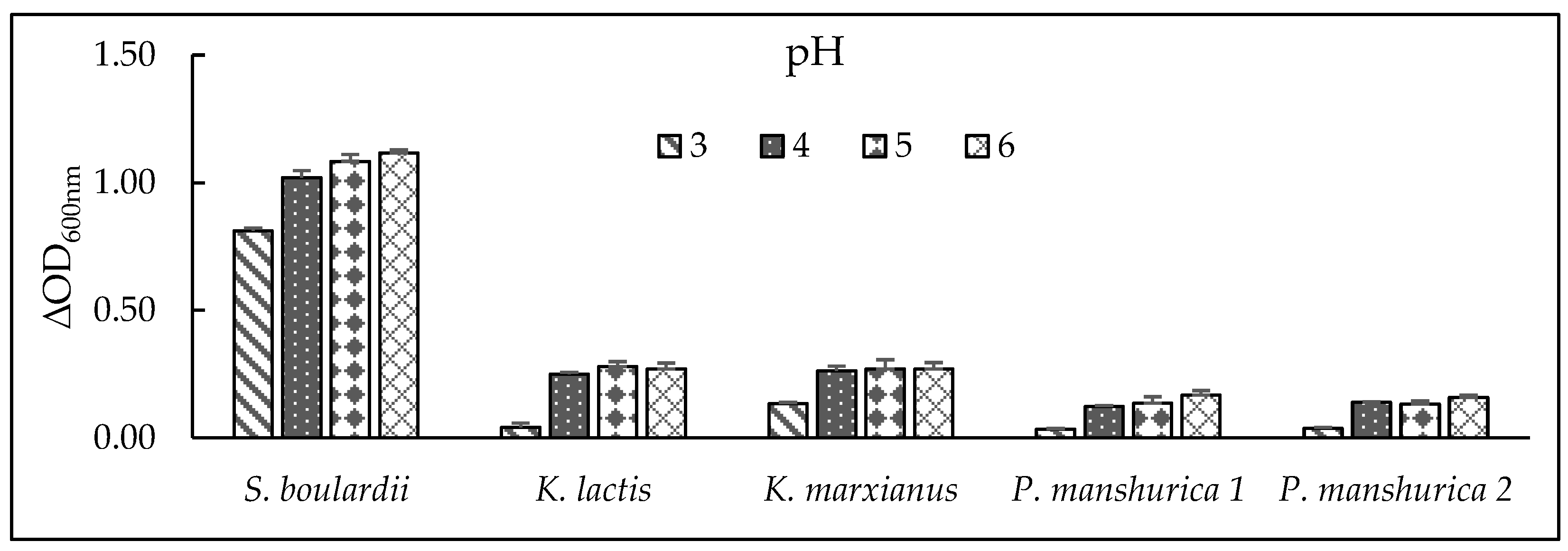

3.3. pH Tolerance

Determination of pH tolerance was used to identify growth behaviour of the studied yeasts to withstand harsh conditions of human stomach (pH 3), fermented medium – beer (pH 4 – 5), and fermentation medium – wort (pH 6). Yeast growth for

Pichia and

Kluyveromyces sp. was strongly inhibited when exposed to highly acidic environment close to pH in human stomach (pH = 3), only yeast

S. boulardii was able to withstand this acidic environment and with the highest determined ΔOD

600nm values (

Figure 2). According to [

34] the probiotic yeast

S. boulardii can survive under stomach conditions (pH 3), which was confirmed by our results. As for other four non-

Saccharomyces yeasts of

Pichia and

Kluyveromyces sp., increased cell count (above the initial inoculated pitch rate of 10

6 Cells.ml

-1) in values of ΔOD

600nm was detected at pH ≥3 and was generally of rising characteristics to pH 6. The viability of a traditional brewery yeast should normally found to lie in the range of 90 – 99% [

35] and it is generally accepted that the live cell content of the yeast slurry used for subsequent fermentation should contain >95% of live cells, whereas high yeast viability allows for the production of high-quality beer [

36]. However, our viability results revealed that

Kluyveromyces and

Pichia yeasts were not as viable as

S. boulardii (69%) in acidic media (pH =3) after 24h at 37°C due to their low percentage of viability which was under 21% (

Table 4). Different results were obtained when several

K. marxianus strains were investigated by [

37] under harsh acidic environment (<pH 3), results showed initial reduction of cell counts from 10

9 to 10

7 Cells.ml

-1 and afterward growth of

K. marxianus strains during the incubation period of 96h. Stable intracellular pH is crucial for yeast growth and metabolic activity, as enzymatic functions depend on an intracellular pH environment; whereas significant deviations in extracellular pH can disrupt this balance, impairing enzyme activity and cellular function [

38].

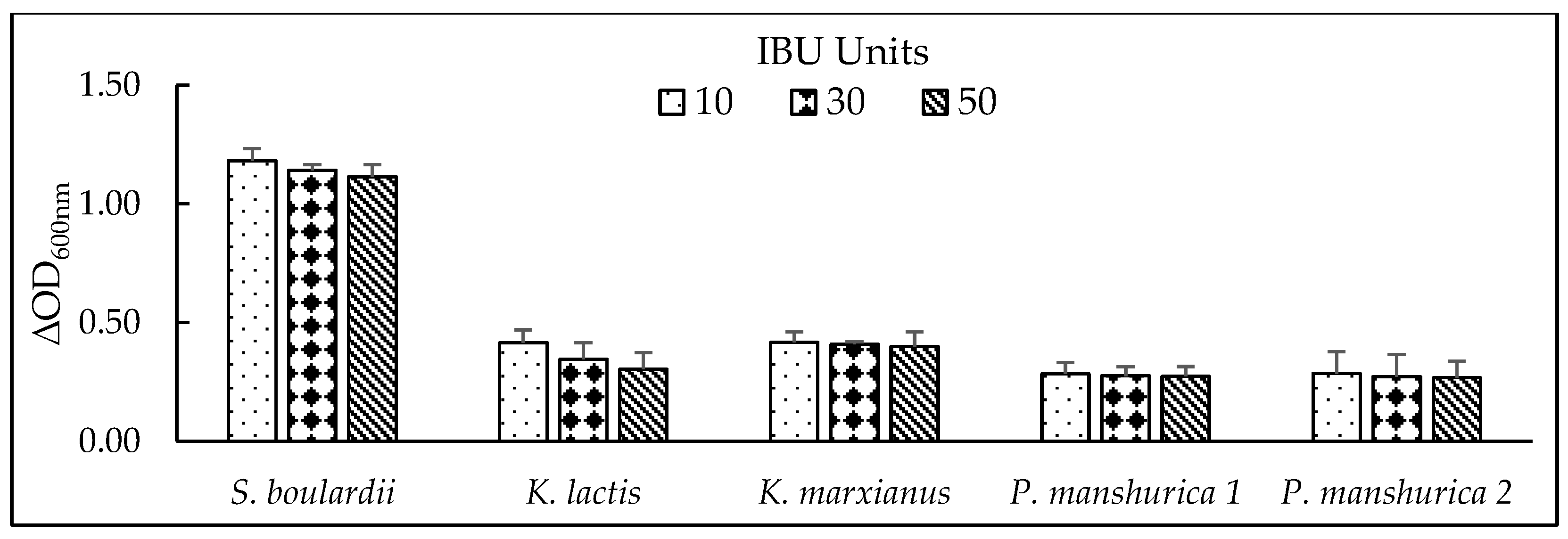

3.4. Tolerance of Iso-α-bitter Acids

Hops are traditionally added during beer brewing as a bittering and flavouring agent [

39]. Hops contain α-bitter acids which isomerize during boiling step to form iso-α-bitter acids – compounds responsible for bitterness of beer [

40]. These substances report antimicrobial properties and protect the beer against the most common spoilage bacteria [

41]. However, [

42] reported that iso-α-bitter acids can affect not only the growth of lactic acid bacteria but can also inhibit the growth of yeast

S. cerevisiae at the concentration of iso-α-bitter acids above 500 mg.L

-1 (equal to 500 International Bitterness Units – IBUs), which is approximately ten times higher than the concentrations required to inhibit bacterial growth. According to [

14], most alcohol-free beers do not tend to exceed 30 IBU. The growth of tested yeasts was probed in the presence of 10,30 and 50 IBU (values characteristic for most of the beer styles) where no exceptional effects of different concentrations of iso-α-bitter acids in terms of different (IBU units) on yeast growth was detected (

Figure 3). Viability of all strains in tested media with different IBUs remained above 95% (data not shown).

3.5. Basic Beer Parameter Analysis

An important analytical parameter of beer is the ethanol concentration, which influences the sensory properties of beer, especially the fullness of flavour, but also colloidal and biological stability of the beer [

3]. The ethanol concentration in produced beers ranged from 0.04 ± 0.01% (v/v) (PM1) to 1.52 ± 0.06% (v/v) (SBL) (

Table 5) and from all the analysed beers except the beer produced with

Saccharomyces boulardii none displayed ethanol concentration ≥0.5% (v/v) which is the limit concentration in alcohol-free beers [

43]. Authors [

44] also studied use of probiotic yeast

S. boulardii, influence of hops on its propagation and fermentation performance and produced beers with 4.67 – 3.26% (v/v) of ethanol. Important note should be considered as term “probiotic beer” (containing 1 x 10

9 CFU, beneficial for health) [

15] might be in conflict with the term “alcoholic beer” (generally containing more than 1.2% v/v of ethanol) where ethanol is considered as a drug. In the characterisation of beers, pH is an important quality indicator, which influences the foaminess, clarity, microbiological and colloidal stability of the beer [

45]. During fermentation of wort, organic acids are produced by yeast, which leads to a decrease of the pH value of the product. The average pH of common beers ranges from 4.3 to 4.7 [

46], while the pH of the produced beers ranged from 4.83 ± 0.02 (SBL) to 5.80 ± 0.01 (PM1) (

Table 5) which was supposedly due to the short-used fermentation times (2 days). The viability of the tested yeasts with methylene-blue staining (data not shown) showed that pascalisation procedure successfully inactivated the yeasts in all beer samples fermented with tested yeasts (

Table 1) to prevent further fermentation activity.

3.6. Organic Compound HPLC Analysis

The saccharide composition of beer can greatly affect the resulting taste of beer. Saccharide such as maltose strongly contributes to the body of the beer while the glucose and sucrose contribute to the sweet taste of the beer [

47]. In comparison with used wort, minimal decrease of glucose and maltose were observed in beers fermented with

Kluyveromyces and

Pichia yeasts (

Table 6). It is known that many yeasts can assimilate certain mono- or oligosaccharides aerobically, but not anaerobically (fermentation) whereas this phenomenon is known as the Kluyver effect [

48]. Oxygen availability plays a key role in determining the fermentation pattern of

K. lactis. As oxygen availability decreases, overall glucose metabolism slows down, resulting in reduced fermentation activity [

49]. This might be one of the answers to results concluded in

Table 6, where only a small proportion of glucose and maltose were consumed by the non-

Saccharomyces yeasts

K. lactis,

K. marxianus and both strains of

P. manshurica. In comparison, beer fermented with probiotic yeast

S. boulardii (SBL) had no residual glucose which was presumably utilized during the first 2 days of beer fermentation (

Table 6) which is supported by the obtained results from saccharide fermentation tests where after 24h the glucose was already being fermented (

Table 2). As for maltose, the most abundant saccharide present in the beer wort [

39], results showed that its final concentration decreased strongly during fermentation from 36.8 ± 0.5 g.L

-1 (wort 8°P) to 24.1 ± 0.3 g.L

-1 in the beer fermented by

S. boulardii (SBL) as was expected (maltose-positive strain) (

Table 2) and ethanol (1.52 ± 0.06% (v/v)) was produced. Glycerol concentrations were below the perception threshold level which in beer is 10 g.L

-1 [

39]. Organic acids not only have a significant effect on the sour taste of beer but also lower the pH of beer, which affects the quality and stability of beer flavour [

50]. Concentration of citric acid in beers produced by non-

Saccharomyces yeasts was 0.1 ± 0.0 g.L

-1(

Table 6). Beer prepared with

S. boulardii contained (0.3 ± 0.0 g.L

-1 of citric acid and unlike beers fermented with four other non-

Saccharomyces yeasts (

K. lactis,

K. marxianus and both

P. manshurica), also contained acetic acid (0.1 ± 0.0 g.L

-1) which is not desired.

S. boulardii unique mutations cause accumulation of higher amounts of acetic acid which on the other hand might inhibit bacterial growth [

51] but acetic acid affects the taste of beer in a drastic way, with its sharp acidity and vinegar notes when present in beer above the threshold concentration 200 mg.L

-1 [

52,

53].

3.7. Volatile Organic Compound Analysis by HS-SPME-GC-MS

Among the most important factors influencing the organoleptic quality of beer is the presence of higher alcohols, esters and carbonyl compounds. Our study revealed that during submerse fermentations, non-Saccharomyces yeasts of probiotic potential Kluyveromyces lactis, K. marxianus and both Pichia manshurica displayed potential in production of fermentation by-products, interesting from the brewer´s perspective, namely esters and higher alcohols.

The synthesis of higher alcohols via the Ehrlich pathway involves brewing yeasts absorbing amino acids from the wort, where the amino acids serve as carriers of essential amino groups that act as building blocks for forming yeast structural component after which the remains of amino acids (α-keto acids) are irreversibly converted to higher alcohols [

54]. Increase of fermentation temperature strongly affects transport of amino acid into the yeast cell and thus favouring the increase of higher alcohol production [

55]. As the formation of higher alcohols is temperature dependent, it also strongly influences final ester formation where higher alcohols are necessary for ester formation [

56]. Our study revealed that yeasts

P. manshurica,

K. lactis and

K. marxianus were able to introduce higher alcohols such as 2-methyl-1-propanol, 2-methyl-1-butanol, 3-methyl-1-butanol into the beer, however concentrations of these alcohols were several times lower in comparison with the fermentation led by the probiotic strain

S. boulardii (

Table 7). Authors [

14] worked with probiotic strain of

S. boulardii described influence of main fermentation parameters (temperature, pitch rate, wort composition) on content of higher alcohols and esters and revealed that increasing fermentation temperature and pitch rate increases higher alcohol and ester formation.

Esters might be implemented into a beer during fermentation, acetate esters (ethyl, 2-phenylethyl and 3-methylbutyl acetate) and ethyl esters (ethyl hexanoate, octanoate and decanoate) [

57]. The formation of acetate esters involves higher alcohols and the ethyl esters are formed by condensation reaction of ethyl alcohol and acyl-CoA [

58]. Final concentration of esters in beer is closely related to composition of used wort and fermentation conditions [

59]. Ethyl acetate and 2-phenylethyl acetate were the only ethyl esters detected in beers prepared in this study (

Table 7). According to [

60], yeast

K. marxianus and

K. lactis might produce increased concentrations of volatile organic compounds such as esters, higher alcohols during the fermentation process.

Positive POF

+ phenotype for all tested yeast (

Table 2), was supported by the presence of 4-vinylguaiacol (clove aroma) in final beers (

Table 7). Diacetyl (2,3-butanedione), an unwanted yeast metabolite (buttery aroma) was not detected in the final beers. These results favour in the use of novel potential probiotic yeasts which might tailor aromatic profile of final non-alcoholic beer (e.g. wheat style beers) in a positive way and boost its functionality as a novel beverage with health benefits.

3.8. Sensorial Evaluation of Beer Samples

Beer fermented with

S. boulardii displayed sour and alcoholic character (

Figure 4) with the noticeable notes of acetic acid with ethyl acetate. Throughout the beer fermentation process,

Kluyveromyces lactis and

K. marxianus yeasts were able to implement strong clove and burned apple-like aroma notes (phenolic) (

Figure 4) into the beer which might be beneficial for producing wheat-based functional non-alcoholic beers. Both strains of

Pichia manshurica had no negative impact on the final beer flavour profile, beers fermented with these two strains were very sweet with the notes of rose scent (floral) (

Figure 4).

4. Conclusions

In recent years, rising interest in producing functional beers using yeasts with potential probiotic attributes in the beverage industry is taking place. In the presented study, we focused on the potentially probiotic yeasts Kluyveromyces lactis, K. marxianus and Pichia manshurica and their application in the non-alcoholic beer (NAB) production also using Saccharomyces boulardii as a control probiotic strain. The characterisation of yeast strains demonstrated the survival in the simulated conditions of the human digestive tract (human body temperature and stomach acidic pH) after 24 hours. On top of that, tested yeasts were able to ferment the beer matrix (wort), sustained different IBU (iso-α-bitter acid concentrations) as a sole fermentation culture with targeted conditions to produce NABs. Stabilisation of beer achieved inactivation of yeast, but the yeast cells remained intact – which might serve for functionality of the beer as postbiotics. The final NABs prepared using non-Saccharomyces potential probiotic yeasts K. marxianus, K. lactis and P. manshurica (first time used in the brewing) showed a potential in tailoring final beer sensory profile by producing higher alcohols (2-methyl-1-propanol, 2-methyl-1-butanol and 3-methyl-1-butanol, 2-phenylethanol,) and esters (ethyl acetate and ethyl hexanoate), and no acetic acid, making them a suitable alternative to the commercially available probiotic yeast S. boulardii. All tested yeast strains exhibited production of 4-vinylguaiacol (clove) which was supported by a POF+ phenotype suited for wheat style beer. Sensorial analysis of the final non-alcoholic beers fermented with K. marxianus, K. lactis and P. manshurica revealed their sweet character (residual saccharides) with the notes of clove and rose aroma traces. This work provides insights into further applications in functional beer production using novel non-Saccharomyces potential probiotic yeast strains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.V., J.B., and P.D.; methodology, validation, P.V., J.B., and R.J.; formal analysis, P.V., J.B., and KF.; investigation, J.B., P.V., and R.J.; resources, T.K., P.D., and D.Š.; data curation, P.V., and K.F.; writing – original draft preparation, P.V.; writing – review and editing, T.K., K.F.; visualization, K.F., J.B. and P.V.; supervision, P.D. and D.Š.; project administration, P.D. and D.Š.; funding acquisition, P.D. and D.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Scientific Grant Agency of Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and Slovak Academy of Sciences VEGA 1/0063/18, by Slovak Research and Development Agency APVV-22–0235 and Sport of the Slovak Republic within the Research and Development Operational Program for the project ‘University Science Park of STU Bratislava’, ITMS 26240220084.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chan, M.Z. A.; Toh, M.; Liu, S. Q. Beer with Probiotics and Prebiotics. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Foods. Elsevier, 2021, 179–199.

- Statista 2024. Accessed online on 30.4.2025 (https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/alcoholic-drinks/beer/non-alcoholic-beer/worldwide).

- Habschied, K.; Živković, A.; Krstanović, V.; et al. Functional Beer—A Review on Possibilities. Beverages 2020, 6, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polaris 2024. Accessed online on 30.4.2025 (https://www.polarismarketresearch.com/industry-analysis/probiotics-market).

- Hinojosa-Avila, C.R.; García-Gamboa, R.; Chedraui-Urrea, J.J.T.; et al. Exploring the potential of probiotic-enriched beer: Microorganisms, fermentation strategies, sensory attributes, and health implications. Food Research International 2024, 175, 113717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, L.; Nikulin, J.; Juvonen, R.; et al. Sourdough cultures as reservoirs of maltose-negative yeasts for low-alcohol beer brewing. Food Microbiology 2021, 94, 103629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamenko, K.; Kawa-Rygielska, J.; Kucharska, A.Z. Characteristics of Cornelian cherry sour non-alcoholic beers brewed with the special yeast Saccharomycodes ludwigii. Food Chemistry 2020, 312, 125968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okaru, A.O.; Lachenmeier, D.W. Defining No and Low (NoLo) Alcohol Products. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brányik, T.; Silva, D.P.; Baszczyňski, M.; et al. A review of methods of low alcohol and alcohol-free beer production. Journal of Food Engineering 2012, 108, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellut, K.; Michel, M.; Zarnkow, M.; et al. Screening and Application of Cyberlindnera Yeasts to Produce a Fruity, Non-Alcoholic Beer. Fermentation 2019, 5, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, M.; Meier-Dörnberg, T.; Jacob, F.; et al. Review: Pure non-Saccharomyces starter cultures for beer fermentation with a focus on secondary metabolites and practical applications: Non-conventional yeast for beer fermentation. J Inst Brew 2016, 122, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaštík, P.; Rosenbergová, Z.; Furdíková, K.; et al. Potential of non-Saccharomyces yeast to produce non-alcoholic beer. FEMS Yeast Research 2022, 22, foac039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkarcinova, B.; Graça Dias, I.A.; Nespor, J.; et al. Probiotic alcohol-free beer made with Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii. LWT 2019, 100, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIH, 2024. Accessed online on 30.4.2025 (https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Probiotics-HealthProfessional).

- Del Valle, J. C.; Bonadero, M. C.; Fernández-Gimenez, A.V. Saccharomyces cerevisiae as probiotic, prebiotic, synbiotic, postbiotics and parabiotics in aquaculture: An overview. Aquaculture 2023, 569, 739342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Ebrahimi, M.; Shahryari, S.; et al. Food applications of probiotic yeasts; focusing on their techno-functional, postbiotic and protective capabilities. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 128, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, S.; Anal, K. Probiotics-based foods and beverages as future foods and their overall safety and regulatory claims. Future Foods 2021, 3, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira De Paula, B.; De Souza Lago, H.; Firmino, L.; et al. Technological features of Saccharomyces cerevisiae var. boulardii for potential probiotic wheat beer development. LWT 2021, 135, 110233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuhara, H. ; Kluyveromyces lactis – a retrospective. FEMS Yeast Research 2006, 6, 323–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, A.J.; Puricelli, M.; Ortiz-Merino, A.R.; et al. Origin of Lactose Fermentation in Kluyveromyces lactis by Interspecies Transfer of a Neo-functionalized Gene Cluster during Domestication. Current Biology 2019, 29, 4284–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Siso, M.I.; Ramil, E.; Cerdán, M.E.; et al. Respirofermentative metabolism in Kluyveromyces lactis: Ethanol production and the Crabtree effect. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 1996, 18, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Ji, L.; Xu, Y.; et al. 2022. Bioprospecting Kluyveromyces marxianus as a Robust Host for Industrial Biotechnology. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2022, 10, 851768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyotome, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Horie, M. Draft Genome Sequence of the Yeast Pichia manshurica YM63, a Participant in Secondary Fermentation of Ishizuchi-Kurocha, a Japanese Fermented Tea. Microbiology Resource Announcements 2019, 8, e00528-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, A.; Yari Khosroushahi, A.; Faghfoori, Z.; et al. Molecular identification and probiotic characterization of isolated yeasts from Iranian traditional dairies. Progress in Nutrition 2019, 21, 445–457. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Huo, N.; Wang, Y.; et al. Aroma-enhancing role of Pichia manshurica isolated from Daqu in the brewing of Shanxi Aged Vinegar. International Journal of Food Properties 2017, 20, 2169–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaštík, P.; Sulo, P.; Rosenbergová, Z.; Klempová, T.; Dostálek, P.; Šmogrovičová, D. Novel Saccharomyces cerevisiae × Saccharomyces mikatae Hybrids for Non-alcoholic Beer Production. Fermentation 2023, 9, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoglan, S.Y.; Jung, R.; Gauthier, M.; et al. Maltose-Negative Yeast in Non-Alcoholic and Low-Alcoholic Beer Production. Fermentation, 2022; 8, 273. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtzman, C.; Fell, J. The Yeasts: A Taxonomic Study. 2011, Elsevier ISBN 9780444521491.

- Gao, P.; Peng, S.; Sam, F.E.; et al. Indigenous Non-Saccharomyces Yeasts With β-Glucosidase Activity in Sequential Fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae: A Strategy to Improve the Volatile Composition and Sensory Characteristics of Wines. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, S.; Steensels, J.; Gallone, B.; et al. Rapid Screening Method for Phenolic Off-Flavor (POF) Production in Yeast. Journal of the American Society of Brewing Chemists, 2017, 75, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montini, N.; Doughty, T.W.; Domenzain, I.; et al. Identification of a novel gene required for competitive growth at high temperature in the thermotolerant yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus. Microbiology 2022, 168, 001148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pais, P.; Almeida, V.; Yilmaz, M.; et al. Saccharomyces boulardii: What Makes It Tick as Successful Probiotic? Journal of Fungi 2020, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.N.; Afrin, S.; Humayun, S.; et al. Identification and Growth Characterization of a Novel Strain of Saccharomyces boulardii Isolated from Soya Paste. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2020, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, R.B. Determination of yeast viability. J. Inst. Brew. 1959, 65, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharczyk, K.; Żyła, K.; Tuszyński, T. Optimization of Fermentation Parameters in a Brewery: Modulation of Yeast Growth and Yeast Cell Viability. Processes 2025, 13, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, R.; Nosrati, R.; Zare, H.; et al. Screening and characterization of in-vitro probiotic criteria of Saccharomyces and Kluyveromyces strains. Iran J Microbiol. 2018, 10, 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Narendranath, N.V.; Power, R. Relationship between pH and medium dissolved solids in terms of growth and metabolism of Lactobacilli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae during ethanol production. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005, 71, 2239–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, D.E.; Boulton, C.A.; Brookes, P.A.; Stevens, R. Briggs, D.E.; Boulton, C.A.; Brookes, P.A.; Stevens, R. Brewing science and practice. Abington Hall, Abington: Woodhead Publishing Limited; 2004.

- Yang, X.; Wang, Z.; Weizhe, S.; et al. Characterization and formation mechanisms of viable, but putatively non-culturable brewer's yeast induced by isomerized hop extract. LWT 2022, 155, 112974. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, M.; Cocuzza, S.; Biendl, M.; et al. The impact of different hop compounds on the growth of selected beer spoilage bacteria in beer. J. Inst. Brew 2020, 126, 354–361. [Google Scholar]

- Hazelwood, L.A.; Walsh, M.C.; Pronk, J.T.; et al. Involvement of Vacuolar Sequestration and Active Transport in Tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to Hop Iso-α-Acids. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2010, 76, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decree 2014. No 30/2014 of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of the Slovak Republic of 31 January 2014 on requirements for beverages.

- Díaz, A.B.; Durán-Guerrero, E.; Valiente, S.; et al. Development and Characterization of Probiotic Beers with Saccharomyces boulardii as an Alternative to Conventional Brewer’s Yeast. Foods 2023, 12, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, K. The Effect of Beer pH on Colloidal Stability and Stabilization--A Review and Recent Findings. Technical Quarterly. 2010, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basařová, G.; Šavel, J.; Basař, P.; et al. Pivovarství: Teorie a praxe výroby piva, VŠCHT, Praha, 2010;1–863. ISBN 978-80-7080-734-7.

- Van Landschoot, A. Saccharides and sweeteners in beer. Cerevisia 2009, 34, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara, H. The Kluyver effect revisited. FEMS Yeast Research 2003, 3, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merico, A.; Galafassi, S.; Piskur, J.; et al. The oxygen level determines the fermentation pattern in Kluyveromyces lactis. FEMS Yeast Research 2009, 9, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, F. Changes in Organic Acids during Beer Fermentation. Journal of the American Society of Brewing Chemists 2015, 73, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, B.T.; Subotić, A.; Vandecruys, P.; et al. Enhancing probiotic impact: engineering Saccharomyces boulardii for optimal acetic acid production and gastric passage tolerance. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2024; e0032524. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchez, A.; De Vuyst, L. Acetic Acid Bacteria in Sour Beer Production: Friend or Foe? Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 957167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Oevelen, D.; Delescaille, F.; Verachtert, H. Synthesis of aroma components during spontaneous fermentation of lambic and gueuze. J. Inst. Brew. 1976, 82, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, E.; Teixeira, J.A.; Brányik, T.; et al. Yeast: The soul of beer's aroma - A review of flavour-active esters and higher alcohols produced by the brewing yeast. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2014, 98, 1937–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, Y.; Omura, F.; Miyajima, K.; et al. Control of Higher Alcohol Production by Manipulation of the BAP2 Gene in Brewing Yeast. Journal of the American Society of Brewing Chemists 2001, 59, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landaud, S.; Latrille, E.; Corrieu, G. Top pressure and temperature control the fusel alcohol/ester ratio through yeast growth in beer fermentation. Journal of The Institute of Brewing 2001, 107, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saerens, S.M.; Delvaux, F.; Verstrepen, K.J.; et al. Parameters affecting ethyl ester production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae during fermentation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2008, 74, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, N.X.; Bieseman, J.; Daran, J.M.G. Unlocking lager's flavour palette by metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces pastorianus for enhanced ethyl ester production. Metabolic Engineering, 2024; 85, 180–193. [Google Scholar]

- Nešpor, J.; Andrés-Iglesias, C.; Karabín, M.; et al. Volatile Compound Profiling in Czech and Spanish Lager Beers in Relation to Used Production Technology. Food Anal. Methods 2019, 12, 2293–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano-Plaza, M.; Noriega-Cisneros, R.; et al. Fermentative capacity of Kluyveromyces marxianus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae after oxidative stress. J Inst Brew 2017, 123, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Temperature tolerance of tested yeasts in 2% YPD medium at 3 different temperatures (4, 20 and 37 °C) after 24h by Optical density (ΔOD600nm) measurements. Results are presented as Average values of 3 OD600nm measurements.

Figure 1.

Temperature tolerance of tested yeasts in 2% YPD medium at 3 different temperatures (4, 20 and 37 °C) after 24h by Optical density (ΔOD600nm) measurements. Results are presented as Average values of 3 OD600nm measurements.

Figure 2.

pH tolerance of tested yeasts in 2% YPD medium with different pH (3 – 6) after 24h, at 37 °C by Optical density (∆OD600nm) measurements. Results are presented as Average value of 3 OD measurements.

Figure 2.

pH tolerance of tested yeasts in 2% YPD medium with different pH (3 – 6) after 24h, at 37 °C by Optical density (∆OD600nm) measurements. Results are presented as Average value of 3 OD measurements.

Figure 3.

Iso-α-bitter acid tolerance of tested yeasts in 2% YPD medium with different IBU concentrations (10, 30 and 50) after 24h, at 25 °C by Optical density (∆OD600nm) measurements. Results are presented as Average value of 3 OD measurements.

Figure 3.

Iso-α-bitter acid tolerance of tested yeasts in 2% YPD medium with different IBU concentrations (10, 30 and 50) after 24h, at 25 °C by Optical density (∆OD600nm) measurements. Results are presented as Average value of 3 OD measurements.

Figure 4.

Sensorial evaluation of the beer samples represented as aromagram (radar chart). Abbreviation of beer sample corresponds to a yeast abbreviation used for beer production. SBL= S. boulardii, PM1 and PM2 = P. manshurica 1 and 2, KL = K. lactis, KM = K. marxianus. Each aroma attribute of the beer profile represents the mean score obtained from a panel of six evaluators. Scoring scale: was set from 0 (not perceptible) to 6 (strongly perceptible).

Figure 4.

Sensorial evaluation of the beer samples represented as aromagram (radar chart). Abbreviation of beer sample corresponds to a yeast abbreviation used for beer production. SBL= S. boulardii, PM1 and PM2 = P. manshurica 1 and 2, KL = K. lactis, KM = K. marxianus. Each aroma attribute of the beer profile represents the mean score obtained from a panel of six evaluators. Scoring scale: was set from 0 (not perceptible) to 6 (strongly perceptible).

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this work with their abbreviation and short description.

Table 1.

Yeast strains used in this work with their abbreviation and short description.

| Yeast |

Abbreviation |

Description |

|

Pichia manshurica 1 CCY* 039-063-001 |

PM1 |

Potential probiotic strain |

|

Pichia manshurica 2 CCY* 039-063-004 |

PM2 |

Potential probiotic strain |

|

Kluyveromyces lactis CCY* 026-012-002 |

KL |

Potential probiotic strain |

|

Kluyveromyces marxianus CCY* 029-008-010 |

KM |

Potential probiotic strain |

|

Saccharomyces boulardii HANSEN CBS** 5926 |

SBL |

Control probiotic strain |

Table 2.

Determination of saccharide fermentation tests, ß-glucosidase activity and phenolic off-flavour (POF) phenotype tests with studied yeasts after 24h incubation at 25 °C.

Table 2.

Determination of saccharide fermentation tests, ß-glucosidase activity and phenolic off-flavour (POF) phenotype tests with studied yeasts after 24h incubation at 25 °C.

| Yeast (Abbreviation) |

*Saccharide Fermentation |

**ß-Glucosidase Activity |

***POF Phenotype |

| Glucose |

Maltose |

Lactose |

|

Saccharomyces boulardii (SBL) |

+ |

+ |

- |

positive |

POF+

|

|

Pichia manshurica 1(PM1) |

+ |

- |

- |

w/d |

POF+

|

|

Pichia manshurica 2 (PM2) |

+ |

- |

- |

w/d |

POF+

|

|

Kluyveromyces lactis (KL) |

+ |

- |

+ |

positive |

POF+

|

|

Kluyveromyces marxianus (KM) |

+ |

- |

+ |

positive |

POF+

|

Table 3.

Viability of tested yeasts after 24h incubation of yeasts in a 2% YPD medium at 3 different temperatures (4°C, 20 and 37°C).

Table 3.

Viability of tested yeasts after 24h incubation of yeasts in a 2% YPD medium at 3 different temperatures (4°C, 20 and 37°C).

| Yeast |

S. boulardii (SBL) |

P. manshurica 1 (PM1) |

P. manshurica 2 (PM2) |

K. lactis (KL) |

K. marxianus (KM) |

| Viability at 4°C |

83% |

27% |

30% |

35% |

37% |

| Viability at 20°C |

97% |

82% |

83% |

80% |

85% |

| Viability at 37°C |

98% |

97% |

98% |

96% |

96% |

Table 4.

Viability of tested yeasts after 24h incubation at 37 °C of yeasts in a 2% YPD medium at 2 different pH 3 and 6.

Table 4.

Viability of tested yeasts after 24h incubation at 37 °C of yeasts in a 2% YPD medium at 2 different pH 3 and 6.

| Yeast |

S. boulardii (SBL) |

P. manshurica 1 (PM1) |

P. manshurica 2 (PM2) |

K. lactis (KL) |

K. marxianus (KM) |

| Viability at pH 3 |

69% |

17% |

16% |

21% |

18% |

| Viability at pH 6 |

97% |

84% |

86% |

83% |

87% |

Table 5.

Ethanol concentration, pH of the beer samples prepared from 8°P Wort, fermented with tested yeasts (1x106 Cells.mL-1) at 20 °C (2 days) and maturated at 3 °C (3 weeks) and pascalised at 400 MPa (3 min).

Table 5.

Ethanol concentration, pH of the beer samples prepared from 8°P Wort, fermented with tested yeasts (1x106 Cells.mL-1) at 20 °C (2 days) and maturated at 3 °C (3 weeks) and pascalised at 400 MPa (3 min).

| |

Sample |

| Basic Parameters |

8°P Wort |

SBL |

PM1 |

PM2 |

KL |

KM |

| Ethanol % (v/v) |

n.d. |

1.52 ± 0.06 |

0.04 ± 0.01 |

0.07 ± 0.01 |

0.13 ± 0.02 |

0.14 ± 0.01 |

| pH |

6.00 ± 0.06 |

4.83 ± 0.02 |

5.80 ± 0.01 |

5.73 ± 0.02 |

5.41 ± 0.01 |

5.36 ± 0.03 |

Table 6.

Concentration of organic compounds (g.L-1) in the beer samples prepared from 8°P Wort, fermented with tested yeasts (1x106 Cells.mL-1) at 20 °C (2 days) and maturated at 3 °C (3 weeks) and pascalised at 400 MPa (3 min), determined by HPLC-RID-DAD.

Table 6.

Concentration of organic compounds (g.L-1) in the beer samples prepared from 8°P Wort, fermented with tested yeasts (1x106 Cells.mL-1) at 20 °C (2 days) and maturated at 3 °C (3 weeks) and pascalised at 400 MPa (3 min), determined by HPLC-RID-DAD.

| |

Sample |

| Compound (g.L-1) |

8°P Wort |

SBL |

PM1 |

PM2 |

KL |

KM |

| Glucose |

7.3 ± 0.2 |

n.d. |

5.3 ± 0.2 |

5.4 ± 0.1 |

5.4 ± 0.1 |

5.4 ± 0.1 |

| Maltose |

36.8 ± 0.5 |

24.1 ± 0.3 |

35.5 ± 0.3 |

35.1 ± 0.3 |

34.3 ± 0.3 |

35.5 ± 0.6 |

| Glycerol |

n.d. |

1.2 ± 0.0 |

0.3 ± 0.1 |

0.5 ± 0.0 |

0.5 ± 0.0 |

0.5 ± 0.0 |

| Citric acid |

n.d. |

0.3 ± 0.0 |

0.1 ± 0.0 |

0.1 ± 0.0 |

0.1 ± 0.0 |

0.1 ± 0.0 |

| Acetic acid |

n.d. |

0.1 ± 0.0 |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

| Lactic acid |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

Table 7.

Concentration of VOCs (volatile organic compounds (μg.L-1) of the beer samples prepared from 8°P Wort, fermented with tested yeasts (1x106 Cells.mL-1) at 20 °C (2 days) and maturated at 3 °C (3 weeks) and pascalized at 400 MPa (3 min), determined by HS-SPME-GC-MS.

Table 7.

Concentration of VOCs (volatile organic compounds (μg.L-1) of the beer samples prepared from 8°P Wort, fermented with tested yeasts (1x106 Cells.mL-1) at 20 °C (2 days) and maturated at 3 °C (3 weeks) and pascalized at 400 MPa (3 min), determined by HS-SPME-GC-MS.

| Beer Sample |

Compound

(μg.L-1)

|

SBL |

PM1 |

PM2 |

KL |

KM |

| Ethyl acetate |

530.5 ± 85.8 |

18.6 ± 6.7 |

24.4 ± 7.9 |

212.0 ± 6.3 |

373.8 ± 54.1 |

| 2-Phenylethyl acetate |

73.1 ± 18.4 |

n.d. |

n.d. |

358.1 ± 7.1 |

166.7 ± 11.2 |

| 3-Methylbutyl acetate |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

| 2-Methyl-1-propanol |

981.4 ± 199 |

160.6 ± 26.5 |

983.5 ± 87.2 |

371.1 ± 92.7 |

212.4 ± 46.8 |

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol |

2867.3 ± 66.7 |

363.5 ± 35.7 |

828.2 ± 13.1 |

803.5 ± 42.4 |

488.2 ± 50.0 |

| 3-Methyl-1-butanol |

6125.8 ± 21.5 |

615.0 ± 57.1 |

1195.5 ± 38.5 |

992.8 ± 20.2 |

775.2 ± 48.9 |

| 2-Phenylethanol |

7955.3 ± 163.1 |

1730.0 ± 220.4 |

2377.2 ± 78.9 |

1372.9 ± 93.2 |

1197.5 ± 112.1 |

| Ethyl hexanoate |

274.2 ± 21.6 |

162.9 ± 18.9 |

146.0 ± 7.6 |

139.0 ± 3.0 |

149.4 ± 7.6 |

| Ethyl octanoate |

307.5 ± 44.3 |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

| Ethyl decanoate |

366.1 ± 91.6 |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

| Hexanoic acid |

3855.8 ± 488.0 |

332.4 ± 30.3 |

304.3 ± 51.6 |

239.1 ± 15.0 |

274.7 ± 16.2 |

| Octanoic acid |

2736.1 ± 484.2 |

827.3 ± 140.6 |

524.4 ± 50.7 |

381.9 ± 23.8 |

448.1 ± 15.2 |

| Decanoic acid |

1420.8 ± 273.5 |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

| 4-Vinylguaiacol |

3033.9 ± 48.3 |

650.11 ± 46.4 |

628.10 ± 36.6 |

629.65 ± 44.7 |

681.30 ± 50.1 |

| Butane-2,3-dione |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

n.d. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).