1. Introduction

Climate change represents a critical threat to agricultural productivity across Africa, as shifting climatic patterns increasingly disrupt food systems. The continent has experienced a rise in the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, including prolonged droughts, erratic rainfall, and flooding, which have had detrimental effects on crop yields and overall food security. Ortiz-Bobea et al. (2020) estimate that anthropogenic climate change has reduced global agricultural total factor productivity by approximately 21% since 1961, with disproportionately severe impacts in warmer regions such as sub-Saharan Africa. These challenges are particularly acute for smallholder farmers, who often lack the financial, technical, and infrastructural capacity to adapt to changing conditions (Balgah et al., 2023; Omotoso et al., 2023). Food insecurity remains a persistent concern, as many African countries struggle to produce sufficient food to meet the demands of their rapidly growing populations—limiting not only domestic consumption but also the potential for intra-African trade under conditions of surplus production (Bjornlund et al., 2022). Malnutrition is prevalent, with widespread deficiencies in protein, micronutrients, and vitamin A (Chan et al., 2019). Vegetables and fish are key dietary sources of these nutrients, with fish alone contributing up to 50% of total protein intake in certain African countries (FAO et al., 2020). Nevertheless, per capita consumption of both vegetables and fish remains below global averages and recommended healthy dietary thresholds, resulting in a heavy reliance on imports from outside the continent (Chan et al., 2019; FAO et al., 2020). This dependency highlights the urgent need to strengthen domestic agricultural production and build resilient, self-sustaining food systems. Another pressing challenge lies in youth unemployment and the low appeal of agriculture as a career path for Africa’s growing young population (Boye et al., 2023). With millions entering the labor market annually, agriculture holds significant potential to absorb a substantial share of the workforce. Realizing this potential, however, requires deliberate policy interventions to make the sector more attractive and economically viable for youth. Such measures should focus on enhancing access to skills training, innovation, agricultural extension services, capital, and opportunities for private-sector engagement (Boye et al., 2023).

Addressing the multifaceted challenges facing African agriculture requires a fundamental paradigm shift in agricultural education. This transformation must prioritize affordable, practice-oriented, innovation-driven, and private sector–aligned approaches that equip both students and farmers with the competencies necessary to succeed in an evolving agricultural landscape (Davis et al., 2008; Mkomwa et al., 2022; Boye et al., 2023). The active engagement of the private sector is pivotal in this process, as it can contribute essential resources, technical expertise, and market linkages that enhance the quality, applicability, and impact of agricultural training programs. Co-creation models such as those advanced in this study are emerging as effective mechanisms for fostering collaboration among diverse stakeholders in agricultural research and development. These models convene students, researchers, and private sector actors to jointly design and implement context-specific solutions, including simplified and cost-effective aquaponics systems tailored to address pressing agricultural constraints. Aquaponics, which integrates recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) with hydroponics, exemplifies a closed-cycle technology with potential for sustainable food production (Junge et al., 2017; Benjamin, 2020). By embedding participatory approaches and incorporating diverse stakeholder perspectives into agricultural education and research, such innovations can significantly enhance both the relevance and the long-term impact of capacity-building efforts in the sector. This study introduces a simplified aquaponics system specifically designed to overcome the technical complexity and high capital investment that often hinder the adoption of aquaponics technologies. The system incorporates low-energy operation, minimal technical requirements, and an affordable cost structure, making it highly accessible to a wider user base. With setup costs of less than EUR 1,000—including approximately EUR 550 for a 1 m³ fish tank—scalable to support up to 104 m² of grow beds, this innovation offers new opportunities for enhancing food systems in both urban and rural contexts across sub-Saharan Africa. The combination of affordability, scalability, and operational simplicity positions the prototype as an appropriate solution for smallholder farmers as well as educational institutions seeking practical, high-quality training tools.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Collaborative Development

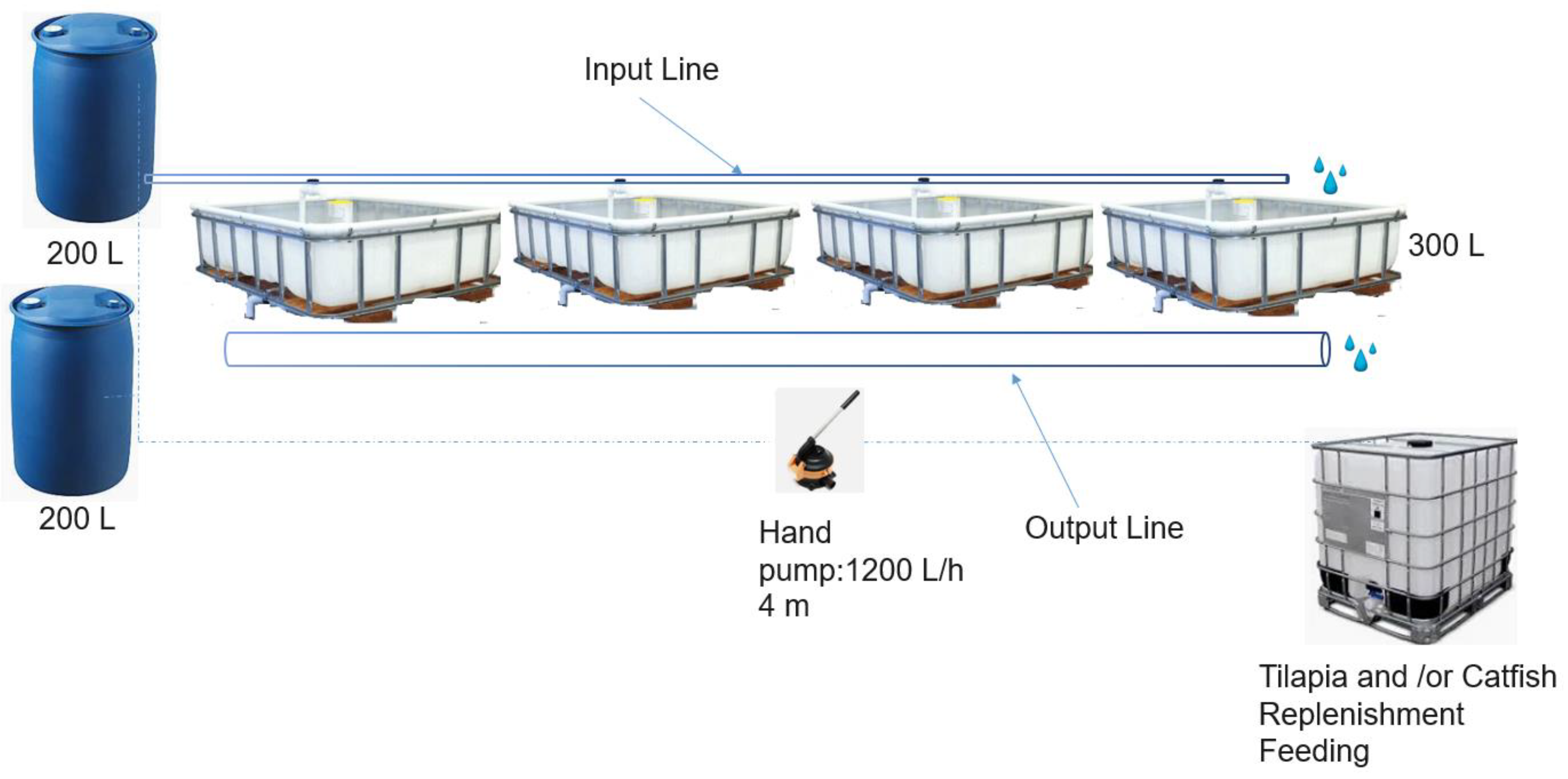

The development of the prototype was the result of a collaborative effort involving the non-governmental organization Aglobe Development Center (ADC), Nigeria; Aquaponik Manufaktur GmbH; and the University of the Bundeswehr Munich (UniBw M), Germany. Its practical implementation engaged students from the Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta (FUNAAB), Nigeria, thereby integrating capacity-building into the project’s execution. The initial conceptual design (Figure 1) was prepared by ADC and subsequently shared with UniBw M and Aquaponik Manufaktur GmbH for technical refinement, leveraging their specialized expertise and experience to optimize the system’s functionality.

Figure 1.

The design and sketch of the simplified aquaponics.

Figure 1.

The design and sketch of the simplified aquaponics.

2.1.2. Simplified Aquaponics System and Components

A key design requirement for the system is its capacity to function with minimal or no reliance on electricity. This off-grid operational capability is intended not merely as an emergency contingency but as a standard operating mode, ensuring that the physiological and environmental needs of both fish and plants are consistently met. The system is engineered to maintain these conditions even under maximum load, defined as the point at which the established carrying capacity for fish and plants is fully utilized.

Fish Tank Specifications

The system utilizes an Intermediate Bulk Container (IBC) tank as the primary fish tank (Figure 21), providing a maximum capacity of 1,000 liters. In the operational configuration, 800 liters of this capacity are allocated for system functioning, ensuring optimal water volume for maintaining stable aquaculture conditions.

Header Tanks

The system incorporates two header tanks, each with a capacity of 200 liters, designed to sustain water circulation for several hours without active pumping. From these tanks, water is directed through the plant grow-bed filtration system and subsequently returned to the fish tank via gravity flow, thereby ensuring continuous nutrient cycling and reducing reliance on external energy inputs.

Grow Beds

The grow-bed component comprises two Intermediate Bulk Container (IBC) tanks, each modified by removing the top and bottom sections to a height of 30 cm, thereby creating four independent growing units. Collectively, these containers provide an effective cultivation area of approximately 4 m². The beds are filled with a suitable inert medium, such as gravel, which functions as a biofiltration zone. Within this zone, residual organic particles undergo further decomposition, and nitrifying bacteria play a critical role in converting ammonia into nitrate, thereby maintaining water quality essential for plant and fish health.

2.2. Plant and Fish Species Selection

The simplified aquaponics system is intended to be cultivated with Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) and African catfish (Clarias Gariepinus) as the fish species.

2.2.1. Crop Variety: Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.)

Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) is among Africa’s indigenous and widely consumed staple vegetables, valued for its ability to supply both macro- and micronutrients to millions across the continent. However, despite its prevalence in local diets, its full nutritional potential remains underexploited (Aderibigbe et al., 2022).

2.2.2. Fish Species: African Catfish (Clarias Gariepinus)

The African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) has emerged as a species of global significance in the aquaculture industry, particularly in regions where environmental constraints limit the cultivation of other fish species due to its robustness (Benjamin et al. 2020). Its prominence is reinforced by its substantial contribution to local and regional economic development. Nutritionally, C. gariepinus is an excellent source of high-quality protein and essential fatty acids, making it highly valuable for human diets (Onyejiaka & Osuigwe, 2019). Under optimal management conditions, the species can attain marketable size within approximately four months (Benjamin et al., 2021)

2.2.3. The Biological Resilience of African Catfish (Clarias Gariepinus)

The African Catfish (Clarias Gariepinus) possesses a unique combination of physiological traits that make it exceptionally suited for low-intensity, resilient aquaculture. This resilience is rooted in its evolutionary adaptations to harsh and variable environments.

Facultative Air-Breathing

The most significant adaptation of Clarias gariepinus is its ability to breathe atmospheric air. The species has a specialized organ at the gills, which functions as a primitive lung, allowing it to survive for extended periods in water with very low dissolved oxygen (DO) concentrations (Onyejiaka & Osuigwe, 2019). While most cultured fish species require continuous aeration to maintain DO levels above a critical threshold, the African catfish can tolerate DO levels as low as 0-3 mg/L without mortality (Environmental, 2012).

Broad Tolerance to Water Quality Parameters

Beyond its tolerance to hypoxia, the African catfish exhibits remarkable hardiness across a spectrum of other critical water quality parameters:

Temperature: It thrives in warm water but can endure a wide temperature range from 8°C to 35°C (Environmental, 2012).

pH: While optimal growth occurs in a pH range of 6.5-8.5 (Nugroho et al., 2021), the species can survive in a much broader range, providing a buffer against the natural pH fluctuations inherent in aquaponic systems.

Nitrogenous Wastes: Clarias gariepinus is known for its high resistance to ammonia, the most toxic nitrogenous waste product in aquaculture. While elevated ammonia negatively impacts growth, the species possesses defense mechanisms to cope with concentrations that would be lethal to other fish (Roques et al., 2011).

2.2.4. Implications for System Engineering

The unique biology of the African catfish directly informs and validates a simplified engineering approach that would be untenable for most other aquaculture species.

Elimination of Continuous Aeration and Pumping: The ability to breathe air is the single most important trait for manual system design. It obviates the need for continuous mechanical aeration and constant water circulation, which are typically the largest energy consumers in a RAS. This allows for an intermittent flow regime, where water is pumped manually (e.g., twice daily) into header tanks and flows via gravity for a limited period, with extended periods of static water being entirely permissible.

Simplified Filtration and Longer Retention Times: The species' tolerance to ammonia and other waste products allows for a less intensive and more passive filtration design. The system can operate with a much longer hydraulic retention time (HRT)—12 hours or more, as opposed to the 30-60 minutes typical of intensive RAS. This reduces the required flow rate, allowing for smaller pumps and piping, and makes simple, non-pressurized media beds effective as the primary biofilter.

Enhanced System Resilience: A system designed around these principles is inherently resilient. It is not vulnerable to power outages or mechanical failures that would be catastrophic in a conventional RAS. This makes it particularly suitable for off-grid applications or in regions where electricity is unreliable or cost-prohibitive.

The selection of Clarias gariepinus is the cornerstone of manual aquaponics design. Its profound biological resilience, particularly its air-breathing capability, makes it possible to engineer a system that is low-cost, low-energy, and robust. This conscious pairing of species and system validates an approach to aquaculture that is accessible, sustainable, and ethically sound, providing a viable food production model for diverse socio-economic contexts.

2.2.5. Flow Rate Management

The system’s average flow rate (Q) is not dependent on the biomass requirements but rather by the volume of the header tanks (Vheader) and the duration between successive pumping cycles (tinterval). Water retained in the header tanks is released by gravity continuously over the entire interval until the subsequent pumping event.

The average flow rate is calculated as:

Using the system operational parameters:

This flow rate represents a fixed parameter inherent to the manual operation and serves as the key determinant of the system’s capacity to process metabolic waste.

Thus, the study calculates the maximum mean production rate (

Rs,mean) that our fixed flow rate (

Q) can support:

For TAN, using the design limit:

This is the maximum mean rate of TAN production that the system can safely process over time. The same process was repeated also for NO

2-N, NO

3-N and TSS.

2.2.6. Feeding Strategy

The maximum permissible daily feeding rate is constrained by the most limiting water quality parameter within the system. Although calculations can be conducted for key substances such as Total Suspended Solids (TSS), nitrite nitrogen (NO₂-N), and nitrate nitrogen (NO₃-N), analyses indicate that Total Ammonia Nitrogen (TAN) serves as the primary limiting factor in determining the design flow rate for systems of this type (Somerville et al., 2014; Bregnballe, 2015). Consequently, the allowable feeding rate is calculated based on the system’s capacity to assimilate and process TAN.

The maximum tolerable mean TAN production rate, estimated at 3.46 g/day, directly informs the calculation of the upper daily feeding limit. This requires determining the specific TAN excretion rate per kilogram of feed (RTAN,excr), which is derived from a nitrogen mass balance under a set of defined assumptions (Boyd & Tucker, 2012):

Feed Nitrogen (Nfeed): A standard feed with 42% crude protein is used, where protein is approximately 16% nitrogen. This results in 67.2g of nitrogen per kg of feed.

Fish Nitrogen Content (Nfish): The biomass of African catfish contains approximately 27.5g of nitrogen per kg of fish.

Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR): An FCR of 1.0 is assumed, meaning 1 kg of feed produces 1 kg of fish biomass. This is a value that is quite usual for African Catfish.

The nitrogen retained in fish biomass (

Nretained) per kg of feed is therefore 27.5g. The total excreted nitrogen (

Nexcreted) is the difference between the nitrogen input and the nitrogen retained:

Not all excreted nitrogen is soluble TAN. Assuming approximately 88% of excreted nitrogen is released as TAN, the specific excretion rate is:

With the total daily TAN processing capacity (

RTAN,daily) of 3.46 g and the specific excretion rate (

RTAN,excr), the maximum daily feed allowance (

Rfeed) is calculated:

Therefore, the system is designed to handle a maximum of approximately

100 grams of fish feed per day.

2.2.7. Stocking Density

The maximum daily feeding rate determines the total fish biomass (or standing stock, mmax) the system can support. The feeding rate (fr) for catfish is typically between 1-2% of their body weight per day, depending on their size and water temperature.

Using the formula

, we can calculate the maximum biomass:

Assuming an average feeding rate of 1.5% (0.015):

With a production volume (

V) of 800 L (0.8 m³), the maximum stocking density (

dmax) is:

This calculation confirms that the operational constraints of the manual system naturally lead to a low stocking density (around 8.4 kg/m³), which aligns perfectly with the system's low-intensity philosophy and further reduces stress on the fish.

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The dataset utilized for the analysis comprises biomass and daily feed weight as well as water quality parameters from a simplified aquaponics system. The students from FUNAAB under the supervision and guidance of the ADC staffs systematically collected this data.

3. Results

3.1. System Operational Performance

The preliminary result for the first 60 days are promising results with all components (see

Figure 2) performing as anticipated and fulfilling their designated hybrid functions in. Water was pumped from the fish tank to the header tanks twice daily at intervals of approximately seven hours. Efficient settling of larger solids occurred at the base of the header tanks, substantially reducing the organic load entering the grow beds, as predicted. Operating at an average flow rate of approximately 1.0 L/min, the 400-liter capacity of the header tanks facilitated continuous water delivery for roughly seven hours per cycle. The observed average flow rate of 0.25 L/min to each media bed corresponds well with the system’s overall design flow rate of 1.0 L/min. The mean flow rate resulted in a hydraulic retention time (HRT) in the media beds of approximately 2 hours. This was long enough to reliably ensure the removal of the organic load and maintain biological filtration (i.e., nitrification). At the same time, the plants were continuously supplied with nutrients. This also enabled the simplified aquaponics system to sustain continuous water flow to both the grow beds and fish tank for a cumulative duration of 14 hours per day, notwithstanding notable fluctuations in flow rate resulting from variations in the hydraulic head within the header tanks. During the remaining 10 hours, primarily overnight, water flow was minimal or ceased altogether. The intermittent flow regime posed no discernible risk to either the African catfish (

Clarias gariepinus) or the cultivated amaranth (

Amaranthus spp.), owing to stable water retention in the media beds and reduced metabolic demands associated with lower ambient temperatures during nighttime.

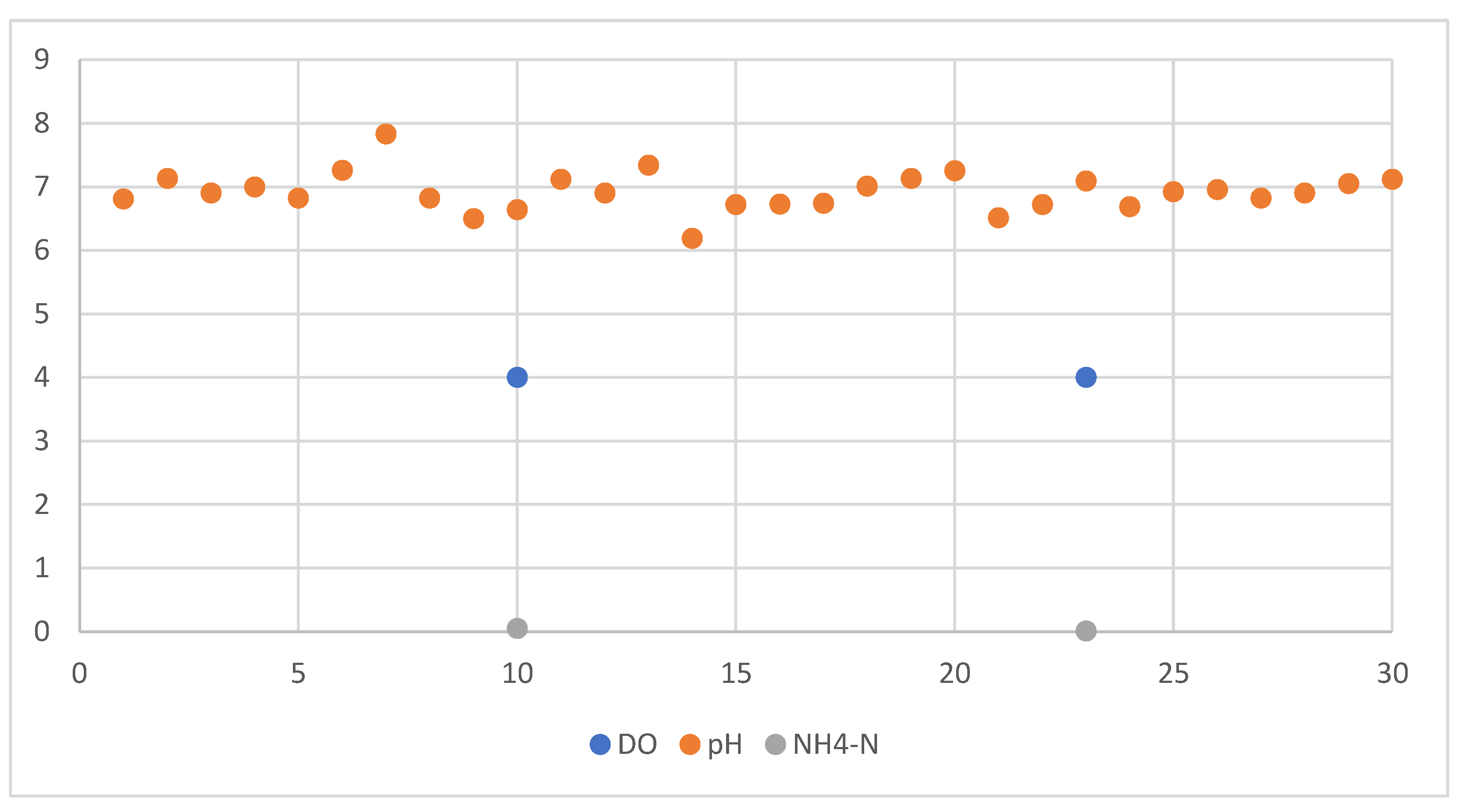

3.1.1. Core Physiochemical Parameters

Dissolved oxygen (DO) levels were consistently maintained near 4 mg/L, a concentration sufficient to support the physiological requirements of aquatic organisms as well as the aerobic microbial communities critical for processes such as nitrification. The system’s pH remained stable at approximately 7 throughout the monitoring period, aligning with the optimal range for efficient plant nutrient assimilation and microbial activity, particularly favoring nitrifying bacteria that thrive in neutral to slightly alkaline environments (see

Figure 3). Ammonium (NH₄⁺) concentrations were measured at below 0.05 mg/L and exhibited a decreasing trend during the preliminary operational phase. This decline suggests active biological conversion of ammonium to nitrite and subsequently to nitrate, indicating a functional and efficient nitrification process within the biofilter or root zone microbiome.

3.1.2. Water Consumption

The actual water replacement within the system was 3 liters per day with stable water quality parameters, underscoring the robustness and efficacy of the integrated plant filtration component. This performance highlights the advantages of the closed-loop aquaponics design, where nutrient cycling and waste assimilation occur synergistically, minimizing the need for frequent water renewal. The plant biofilter effectively removed organic contaminants and metabolized nitrogenous wastes, thereby sustaining a balanced aquatic environment conducive to both fish health and plant growth

3.2. Plant Production Performance (Amaranthus spp.)

After 45 days of cultivation,

Amaranthus spp. plants demonstrated robust growth, reaching an average height of 90 cm and producing approximately 255 leaves per plant (see

Figure 2 above).

3.3. Fish Production Performance (Clarias gariepinus)

The initial mean individual weight of the African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) at stocking was approximately 20 grams, which increased to an average of 125 grams over a 60-day cultivation period, accompanied by a high survival rate of 90%. These growth performance metrics underscore the system’s efficiency and robustness. Based on these results, a projected biomass yield of above 250 g/m³ is both realistic and attainable within this production framework. Preliminary data also indicate a feed conversion ratio (FCR) of 2.0 for the simplified aquaponics system, reflecting moderate feed efficiency consistent with intensively managed aquaculture systems (Benjamin et al., 2021; Onyejiaka & Osuigwe, 2019). Such performance highlights the potential of this system to sustainably produce substantial fish biomass under resource-constrained conditions.

3.4. Cost Analysis

The establishment of the simplified aquaponics system necessitates the strategic procurement of critical components to ensure both operational functionality and long-term sustainability. Central to the system are Intermediate Bulk Containers (IBC tanks), which function as the primary water reservoirs and fish habitats, providing robust and cost-effective containment. Water circulation is facilitated by a manually operated hand pump, complemented by an array of pipes and fittings that enable efficient connectivity between the aquaculture and hydroponic subsystems. The structural framework supporting the aquaponics setup can be fabricated using concrete blocks, wooden frames, or a hybrid approach. In this case study, a combination of concrete and wood was selected to balance stability, durability, and flexibility. The concrete base delivers a solid, weather-resistant foundation capable of withstanding environmental stresses, while the wooden elements afford ease of assembly, adaptability in design modifications, and reduced material costs. The initial capital investment for the system amounted to EUR 333, or EUR 283 excluding the optional block work component (see

Table 1), underscoring the affordability and scalability of this model for smallholder farmers and educational institutions.

While the initial setup utilizes a hand pump due to its cost-effectiveness and ease of use, there is an optional upgrade to a solar-powered pump. This solution would increase the total investment by EUR 212 to EUR 545. This alternative, although more expensive, offers the benefits of automated water circulation and energy efficiency, particularly in off-grid or low-resource settings. Importantly, this upgrade remains feasible within the overall budget of EUR 1,000 allocated for the system, allowing for greater flexibility based on user needs and available resources.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates the feasibility, resilience, and cost-effectiveness of a simplified, low-energy aquaponics system designed for African contexts, with a specific focus on the integration of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and Amaranthus spp. as culturally and nutritionally significant species. The integration of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and Amaranthus spp. creates a nutrient cycle that addresses key micronutrient deficiencies prevalent in African diets. Amaranth (Amaranthus spp) is rich in vitamins A and C, iron, and protein (Achigan-Dako et al., 2014), while African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) provides high-quality animal protein and omega-3 fatty acids (Onyejiaka & Osuigwe, 2019). By combining affordable, scalable technology with context-appropriate biological species, the system addresses three intersecting challenges in sub-Saharan Africa’s food systems: climate change adaptation, food and nutritional security, and youth engagement in agricultural innovation. Aquaponics has been widely recognized as a promising closed-loop food production system that can reduce resource inputs, minimize waste, and improve productivity in constrained environments (Goddek et al., 2019; Love et al., 2015). However, high capital costs, technological complexity, and energy dependence have historically limited its adoption in low-income contexts (König et al., 2018). The current design overcomes these barriers through minimal reliance on electricity, manual water pumping, and passive gravity-fed filtration, aligning with findings that technological simplification can dramatically improve adoption rates in low-resource settings (Junge et al., 2017). Operational results show that the system maintained stable dissolved oxygen (~4 mg/L), pH (~7), and low ammonium (<0.05 mg/L) over 60 days, supporting both fish and plant health. These parameters align with optimal ranges for nitrification and nutrient assimilation (Rakocy et al., 2006; Somerville et al., 2014) and indicate that the simplified filtration and flow design did not compromise system functionality. The minimal daily water loss (~3 L) underscores the system’s water-use efficiency, which is critical in drought-prone regions where irrigation competes with other water demands (FAO, 2020). The ability of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) to tolerate intermittent flow and low DO concentrations is central to the viability of the manual pumping approach. This physiological resilience has been documented in multiple studies (Opiyo et al., 2020; Roques et al., 2011), and here it facilitated the elimination of continuous aeration, a major energy burden in conventional recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS). The result is a robust production model that remains operational under grid-independent conditions, thus mitigating risks posed by power outages and infrastructure gaps (Kubitza, 2025). The achieved amaranth growth rate compares favorably with yields from hydroponic and soil-based systems under similar conditions (Dinssa et al., 2018), and the African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) growth rate (from 20 g to 125 g in 60 days) indicates strong compatibility between species and system parameters. While the feed conversion ratio (FCR) of 2.0 is higher than in some intensive systems (Benjamin et al., 2021), it remains within acceptable limits for low-input aquaculture and reflects the trade-off between feed efficiency and low-energy system design. Furthermore, the relatively low stocking density (~8.4 kg/m³) is consistent with welfare-friendly aquaculture practices that reduce stress and disease incidence (Martins et al., 2012).One of the interesting findings is the low capital investment required, EUR 283–545 depending on pump choice. This affordability places the system within reach of smallholder farmers, community groups, and educational institutions, directly addressing the cost barrier cited in multiple adoption studies (König et al., 2018; Beintema & Stads, 2019). Private sector engagement in both design and implementation stages, through collaboration with Aquaponik Manufaktur GmbH, demonstrates the viability of co-creation models that align academic research, NGO outreach, and commercial expertise. Such multi-stakeholder approaches are increasingly recognized as essential for scaling agricultural innovation in Africa (Davis et al., 2008; Mkomwa et al., 2022). The active role of students in system assembly and monitoring further embeds experiential learning in agricultural education, which is critical for attracting and retaining youth in agribusiness (Boye et al., 2024). Given the vulnerability of African agriculture to climate shocks (Ortiz-Bobea et al., 2020; Omotoso et al., 2023), climate-resilient food production technologies are a strategic necessity. The simplified aquaponics model reduces dependency on climate-sensitive inputs such as irrigation water and synthetic fertilizers, while offering urban and peri-urban scalability to reduce supply chain exposure to extreme weather events. The closed-loop nutrient cycling and minimal waste discharge also align with the circular economy principles underpinning sustainable intensification (Pretty et al., 2018).The choice of culturally accepted and market-preferred species further enhances resilience by integrating into existing dietary habits and value chains. For instance, African catfish has strong market demand across West and Central Africa, ensuring that production can translate into income as well as nutrition (Effiong et al., 2018). From a policy perspective, the findings support the integration of simplified aquaponics into agricultural extension programs, vocational training curricula, and youth agribusiness initiatives. Governments and development agencies could incentivize adoption through microcredit schemes, start-up kits, or integration with climate-smart agriculture subsidies (Marson, 2025). Scaling of the simplified aquaponics will require attention to three enabling factors:

- a)

Local Manufacturing Capacity – Encouraging local fabrication of IBC-based systems and pumps can reduce costs and create ancillary employment.

- b)

Feed Availability – While the system reduces input dependency, sustainable sourcing or local production of quality fish feed remains essential.

- c)

Market Linkages – Building aggregation and cold-chain capacity for fish, alongside urban retail channels for vegetables, will maximize income potential.

The study’s 60-day monitoring period provides promising initial results but limits insights into long-term system dynamics, seasonal variability, and multi-cycle productivity. Future trials should assess nutrient balance over multiple production cycles, pest and disease pressures in plants, and economic performance under fluctuating market conditions. Comparative studies could also evaluate performance against other low-energy aquaponics configurations and alternative species combinations. Furthermore, while the system is designed for low-skill operation, adoption at scale may require simplified manuals, video tutorials, and localized training to ensure consistent management and troubleshooting capacity. Finally, life-cycle assessment (LCA) of the system’s environmental footprint would provide a quantifiable basis for claims of sustainability.

5. Conclusion

This study contributes to the expanding body of evidence demonstrating that low-cost, low-energy aquaponics systems, when strategically adapted to local ecological realities and socio-economic contexts, can serve as a cornerstone in Africa’s ongoing food system transformation. The presented model exemplifies how technology, biology, and participatory governance can intersect to produce a sustainable and socially inclusive innovation. By leveraging the exceptional physiological resilience of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus), capable of thriving in low-oxygen and variable water quality conditions, the system minimizes dependence on continuous aeration and energy-intensive infrastructure, making it particularly suited for off-grid and resource-limited environments. Simultaneously, the incorporation of Amaranth (Amaranthus spp), a nutrient-dense, fast-growing, and culturally familiar crop, ensures that outputs directly address prevalent micronutrient deficiencies while appealing to local dietary preferences. Equally significant is the system’s foundation in multi-stakeholder co-creation, bringing together private sector expertise, academic research capacity, and grassroots implementation networks. This approach enhances not only the technical robustness of the innovation but also its scalability and acceptance across diverse user groups. The affordability of the system, achieved through modular design, repurposed materials, and locally available components, removes one of the most persistent barriers to technology adoption among smallholder farmers, youth entrepreneurs, and community-based organizations. Beyond its immediate productivity gains, the system offers strategic benefits for climate adaptation by reducing reliance on vulnerable supply chains, conserving water resources, and enabling decentralized food production in both urban and rural areas. The integration of hands-on training within its deployment framework further embeds knowledge transfer, fostering a new generation of agricultural innovators. Collectively, these attributes position the simplified aquaponics system not merely as a production tool but as a catalyst for broader socio-economic transformation in empowering youth, enhancing nutritional security, and reinforcing resilience against climate shocks in Africa’s rapidly evolving food landscapes.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union under Horizon Europe, grant agreement No. 101182485, project name “Fair Food and Trade Systems for Africa through Food Convergence Innovation” (FCI4Africa). The views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the management and staff of Aglobe Development Center (ADC), (

www.aglobedc.org) Lagos, Nigeria. We would also like to express sincere gratitude to the students of the fisheries department at the Federal University of Agriculture Abeokuta (FUNAAB), Nigeria that interned at ADC in 2025.

References

- Achigan-Dako, E. G., Sogbohossou, O. E., & Maundu, P. (2014). Current knowledge on Amaranthus spp.: research avenues for improved nutritional value and yield in leafy amaranths in sub-Saharan Africa. Euphytica, 197(3), 303-317. [CrossRef]

- Aderibigbe, O. R., Ezekiel, O. O., Owolade, S. O., Korese, J. K., Sturm, B., & Hensel, O. (2022). Exploring the potentials of underutilized grain amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) along the value chain for food and nutrition security: A review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition, 62(3), 656-669.

- Balgah, R. A., Benjamin, E. O., Kimengsi, J. N., & Buchenrieder, G. (2023). COVID-19 impact on agriculture and food security in Africa. A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Development Perspectives, 31, 100523. [CrossRef]

- Beintema, N., & Stads, G. J. (2019). Taking stock of national agricultural R&D capacity in Africa South of the Sahara. Gates Open Res, 3(654), 654.

- Benjamin, E. O., Buchenrieder, G. R., & Sauer, J. (2021). Economics of small-scale aquaponics system in West Africa: A SANFU case study. Aquaculture economics & management, 25(1), 53-69. [CrossRef]

- Bjornlund, V., Bjornlund, H., & van Rooyen, A. (2022). Why food insecurity persists in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of existing evidence. Food security, 14(4), 845-864. [CrossRef]

- Boye, M., Ghafoor, A., Wudil, A. H., Usman, M., Prus, P., Fehér, A., & Sass, R. (2024). Youth engagement in agribusiness: perception, constraints, and skill training interventions in Africa: A systematic review. Sustainability, 16(3), 1096. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C. E., & Tucker, C. S. (2012). Pond aquaculture water quality management. Springer Science & Business Media.Bregnballe, J. (2015). Recirculation aquaculture. FAO and Eurofish International Organisation: Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Chan, C. Y., Tran, N., Pethiyagoda, S., Crissman, C. C., Sulser, T. B., & Phillips, M. J. (2019). Prospects and challenges of fish for food security in Africa. Global Food Security, 20, 17-25. [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. E., Ekboir, J., & Spielman, D. J. (2008). Strengthening agricultural education and training in sub-Saharan Africa from an innovation systems perspective: a case study of Mozambique. Journal of agricultural education and extension, 14(1), 35-51. [CrossRef]

- Dimado, F.D. (2024). The Best Guide for Optimal Water Parameters for Catfish 2025. https://famerlio.org/optimal-water-parameters-for-catfish/.

- Dinssa, F. F., Yang, R. Y., Ledesma, D. R., Mbwambo, O., & Hanson, P. (2018). Effect of leaf harvest on grain yield and nutrient content of diverse amaranth entries. Scientia Horticulturae, 236, 146-157. 236, 146–157. [CrossRef]

- Effiong, M. U., Ella, F. A., & Adams, Z. O. (2018). Growth performance and yield of hybrid catfish Clarias gariepinus (♂) x Heterobranchus bidorsalis (♀) at various stocking densities. Tropical Freshwater Biology, 27(1), 23-30. [CrossRef]

- Environmental, A. (2012). African sharptooth catfish Clarias gariepinus. DAFF Biodiversity Risk-and Benefit Assessment (BRBA) of alien species in aqua-culture in South Africa.

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, & WHO. (2020). The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2020. Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets. Rome, IT: Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Goddek, S., et al. (2019). Aquaponics and global food challenges. Sustainability, 11(15), 4068. [CrossRef]

- Junge, R., et al. (2017). Aquaponics: The basics. Ecosystem Services, 26, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- König, B., et al. (2018). Potential of small-scale aquaponics for sustainable food production. Agricultural Systems, 165, 110–123. [CrossRef]

- Kubitza, F. (2025). The impact of water quality on health and performance of farmed fish and shrimp, Part 1: dissolved oxygen and carbon dioxide. https://www.globalseafood.org/advocate/the-impact-of-water-quality-on-health-and-performance-of-farmed-fish-and-shrimp-part-1-dissolved-oxygen-and-carbondioxide/.

- Love, D. C., et al. (2015). An international survey of aquaponics practitioners. PLoS ONE, 9(7), e102662. [CrossRef]

- Martins, C. I., et al. (2012). New developments in recirculating aquaculture systems in Europe: A perspective on environmental sustainability. Aquacultural Engineering, 53, 2–13. [CrossRef]

- Marson, M. (2025). Effects of public expenditure for agriculture on food security in Africa. Empirical Economics, 1-32. [CrossRef]

- Mkomwa, S., Mloza-Banda, H., & Mutai, W. (2022). Formal Education and Training for Conservation Agriculture in Africa. In Conservation Agriculture in Africa: Climate Smart Agricultural Development (pp. 305-330). GB: CABI.

- Nugroho, Y. A., Prayitno, S. B., & Sari, S. H. J. (2021). Analysis of Aquaponic-Recirculation Aquaculture System (A-Ras) Application in the Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) Aquaculture in Indonesia. Journal of Aquaculture and Fish Health, 10(2), 177-186. [CrossRef]

- Omotoso, A. B., Letsoalo, S., Olagunju, K. O., Tshwene, C. S., & Omotayo, A. O. (2023). Climate change and variability in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of trends and impacts on agriculture. Journal of Cleaner Production, 414, 137487. [CrossRef]

- Onyejiaka, A. I., & Osuigwe, D. N. (2019). Swimming in the mud – a short review of environmental parameters for the culture of the African catfish, Clarias gariepinus. AACL Bioflux, 12(1), 9-17. [CrossRef]

- Opiyo, A. O., Obiero, M. O., & Ogello, J. O. (2020). High-rate algal ponds for improved dissolved oxygen supply for African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) culture. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies, 8(2), 41-46.

- Ortiz-Bobea, A., Ault, T. R., Carrillo, C. M., Chambers, R. G., & Lobell, D. B. (2020). The historical impact of anthropogenic climate change on global agricultural productivity. arXiv:2007.10415.

- Pretty, J., et al. (2018). Global assessment of agricultural system redesign for sustainable intensification. Nature Sustainability, 1, 441–446. [CrossRef]

- Roques, J. A. C., Schrama, J. M., & Verreth, J. A. J. (2011). The impact of elevated water ammonia concentration on physiology, growth and feed intake of African catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Aquaculture, 319(1-2), 153-158. [CrossRef]

- Roques, J. A. C., Schrama, J. W., & Verreth, J. A. J. (2013). The impact of elevated water nitrite concentration on physiology, growth and feed intake of African catfish (Clarias gariepinus, Burchell 1822). Aquaculture Research, 44(9), 1433-1442. [CrossRef]

- Roques, J. A. C., Schrama, J. W., & Verreth, J. A. J. (2014). The impact of elevated water nitrate concentration on physiology, growth and feed intake of African catfish (Clarias gariepinus, Burchell 1822). Aquaculture Research, 45(4), 647-655. [CrossRef]

- Somerville, C., Cohen, M., Pantanella, E., Stankus, A., & Lovatelli, A. (2014). Small-scale aquaponic food production: integrated fish and plant farming. FAO Fisheries and aquaculture technical paper, (589), I.

- Stone, N. M., & Thomforde, H. K. (2004). Understanding your fish pond water analysis report (pp. 1-4). Cooperative Extension Program, University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, US Department of Agriculture and County Governments Cooperating.

- Wurts, W. A., & Durborow, R. M. (1992). Interactions of pH, carbon dioxide, alkalinity and hardness in fish ponds. Southern Regional Aquaculture Center Publication No. 464. https://aquaculture.ca.uky.edu/sites/aquaculture.ca.uky.edu/files/desirable-water-quality-parameters-for-catfish-ponds.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).