1. Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic, estrogen-dependent condition affecting approximately 10% of reproductive-age women [

1]. It often causes pelvic pain, infertility, and reduced quality of life [

2]. When medical management fails, surgical excision is the preferred treatment. In such cases, particularly when fertility preservation is a concern, the procedure must be performed with high precision to avoid damage to delicate reproductive structures[

1]. In this context, the choice of surgical energy source plays a pivotal role in balancing efficacy and safety.

Energy-based excision techniques are central to gynecologic surgery, providing effective tissue dissection and hemostasis [

3]. However, conventional modalities such as monopolar and bipolar electrosurgery are limited by thermal spread, which can cause unintended injury to surrounding tissues — a particular concern when operating near delicate reproductive structures [

4,

5]. This risk is amplified in fertility-preserving procedures, where precise excision is critical. Even advanced high-frequency bipolar sealing devices can produce considerable thermal spread, increasing the risk of collateral damage [

6]. These drawbacks highlight the need for newer technologies that enable more precise tissue to target minimal thermal damage, particularly in complex gynecologic surgeries.

The Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator (CUSA®) is an advanced surgical device that uses ultrasonic vibration (23–36 kHz) to selectively fragment hydrated tissue [

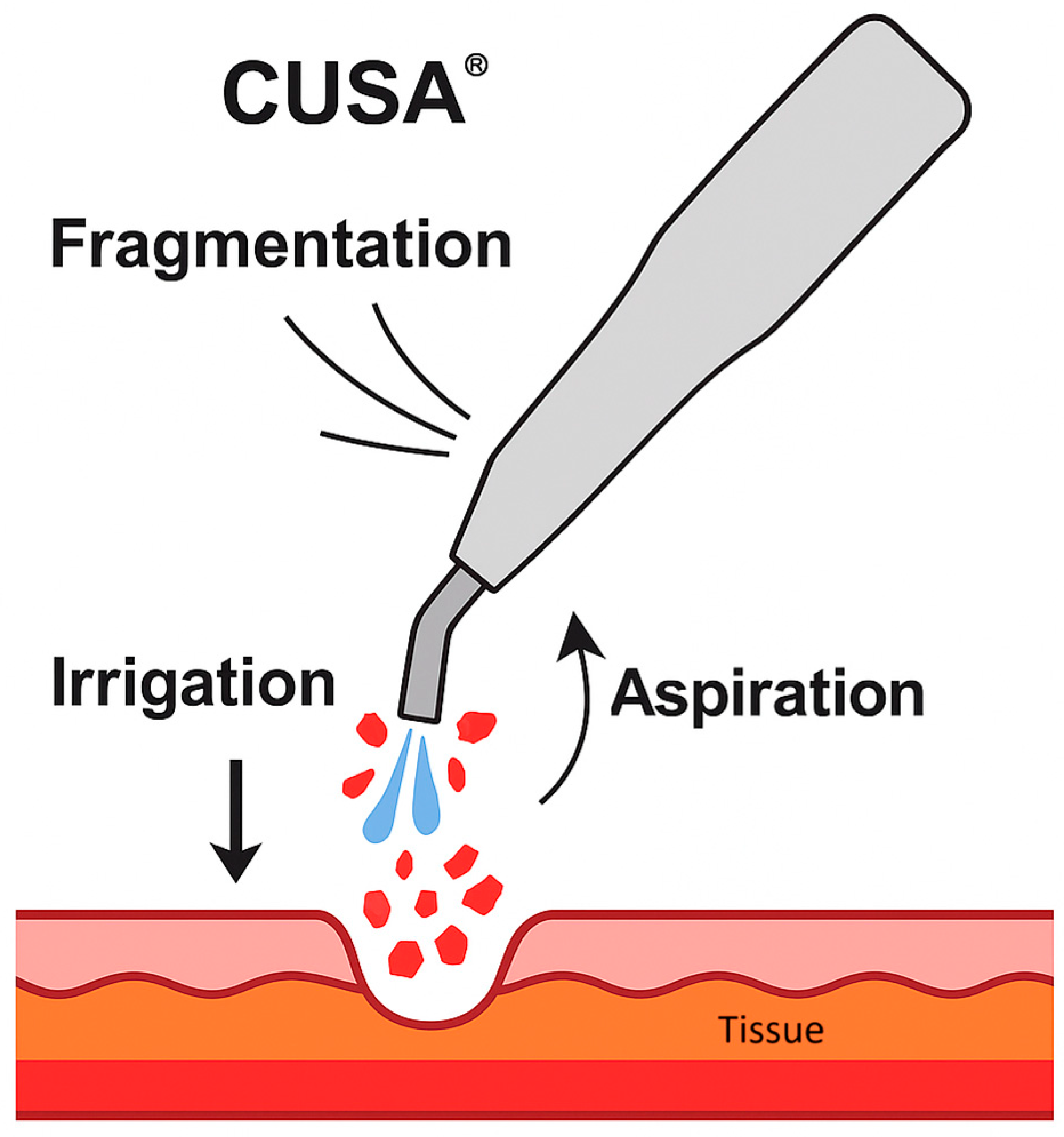

6]. It is based on three main mechanisms principles: fragmentation, irrigation, and aspiration (

Figure 1). It utilizes ultrasonic waves and vibrations to induce cavitation, breaking hydrogen bonds and leading to the denaturation of tissue proteins[

7,

8]. Simultaneously, irrigation flushes the fragmented material, while aspiration clears debris, maintaining visibility and efficiency during surgery [

7].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator (CUSA®) mechanism of action, showing fragmentation of hydrated tissue by ultrasonic vibration, simultaneous irrigation to flush debris, and aspiration to maintain a clear surgical.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator (CUSA®) mechanism of action, showing fragmentation of hydrated tissue by ultrasonic vibration, simultaneous irrigation to flush debris, and aspiration to maintain a clear surgical.

One of CUSA’s main advantages is its ability to selectively fragment tissues with high water content and weak cellular cohesion, while preserving collagen-rich structures such as vessels, nerves, and ducts [

6,

7]. This selectivity is particularly valuable in complex procedures involving deep or fibrotic lesions near vital structures, where surgical precision is essential [

9]. Additionally, CUSA offers limited thermal spread, reduced intraoperative bleeding, and better visualization of the surgical field [

6,

9,

10].

While widely used in hepatobiliary, neurosurgical and cardiothoracic procedures, its use in gynecology – particularly in endometrioses – remains relatively underreported. Some studies have reported its application in selected gynecologic surgeries, such as diaphragmatic stripping during advanced ovarian-cancer debulking [

11], palliative debulking of recurrent vaginal malignancies [

12], laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy [

13], and procedures aimed at preserving postoperative vesicourethral function [

14]. More recently, its use has also been described in the laparoscopic excision of deep-infiltrating [

15] and diaphragmatic endometriosis [

16], where precision and tissue preservation are particularly critical.

This prospective study evaluates the safety, precision, and clinical effectiveness of CUSA for laparoscopic excision of endometriosis, focusing on minimal blood loss, preservation of surrounding structures, and postoperative recovery.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective, single-center cohort study was conducted at Hospital da Luz Arrábida, Porto, Portugal. Fifteen women aged 18–50 years with suspected peritoneal, deep-infiltrating, or diaphragmatic endometriosis were enrolled between January 2024 and January 2025. Exclusion criteria included prior pelvic malignancy, pregnancy, and cases requiring bowel or urinary tract resection.

2.2. Surgical Procedure

All surgeries were performed by a single experienced surgeon, who had previously completed 10 procedures using the CUSA® device. The CUSA Excel+® ultrasonic aspirator (Integra LifeSciences®, Princeton, NJ, USA) was used exclusively for lesion excision and adhesiolysis — no monopolar, bipolar, or laser devices were employed. An initial pelvic inspection was performed through a four-port laparoscopic approach, followed by intraoperative staging according to the Enzian classification. Visible endometriotic lesions and adhesions were then treated using a 10-mm, 23 kHz CUSA Excel+ probe with continuous irrigation and aspiration. Lesion sites included peritoneum, uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, torus uterinus, ovaries, and diaphragm. All surgical specimens were routinely submitted for histopathological analysis to confirm the diagnosis and evaluate histological features.

2.3. Data Collection

For each case, we prospectively recorded skin-to-skin operative time, estimated blood loss, and surgical performance scores (1 = very easy/highly effective to 5 = very difficult/ineffective) for ease of lesion ablation, ease of adhesiolysis, and overall effectiveness of CUSA, as assessed by the lead surgeon. Ease-of-ablation was assessed based on tissue fragmentation, bleeding control, and time/effort required; ease-of-adhesiolysis on adhesion characteristics, separation from critical structures, and instrument maneuverability; and overall effectiveness on lesion removal completeness, preservation of vital structures, hemostasis, and surgical efficiency. The Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) was applied preoperatively to evaluate pain levels.

Postoperative data included complications (Clavien–Dindo classification), hospital stay, and any reoperation within 30 days. At the 4–6 week follow-up, NRS pain score was reassessed, along with time to resume daily and professional activities.

So primary outcomes were CUSA dissection time, blood loss, ease-of-ablation score, ease-of-adhesiolysis score, and overall effectiveness score. Secondary outcomes included hospital stay, time to resume daily/professional activities, change in NRS pain score, and postoperative complications.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed descriptively, as appropriate for the small sample size and exploratory design of this case series. No hypothesis testing or power analysis was performed. Continuous variables are reported as median (interquartile range) and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Tabulations were generated in Microsoft Excel 365®, and graphs in SPSS® version 29.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of Hospital da Luz Arrábida. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and national data protection regulations.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Baseline Characteristics

Sociodemographic and baseline characteristics of the study cohort are summarized in

Table 1. The study cohort comprised 15 women aged 21–39 years (mean: 29y ± 5). The most commonly reported symptoms were dyspareunia (n=15) and dysmenorrhea (n=14), followed by dyschezia (n=8) and scapulodynia (n=4). The mean preoperative NRS score was 6.9 ± 1.4, indicating moderate to severe pain levels at baseline.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and baseline characteristics of our participants.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and baseline characteristics of our participants.

| Characteristic |

Value |

| Participants, n |

15 |

| Age (Mean±SD) |

29± 5 (range 21-39) |

Presenting symptoms, n (%)

Dysmenorrhea Dyspareunia Dyschezia Scapulodynia

|

14 (93%)

15 (100%)

8 (53%)

4 (27%) |

| Preoperative NRS Pain Score (Mean±SD) |

6.9±1.4 |

3.2. Intra-Operative Findings

The CUSA phase of the procedure had a mean duration of 8.5 ± 3.0 minutes (range 4–14 minutes), with a median estimated blood loss of less than 10 mL (no case exceeded 20 mL). The mean ease-of-ablation score was 1.3 ± 0.5, the ease-of-adhesiolysis score of 1.7 ± 0.7, and overall effectiveness score of 1.4 ± 0.6, indicating high procedural efficiency and manageable technical challenges. No intraoperative complications or conversions occurred. The detailed results are presented in

Table 2. The location and extent of endometriotic lesions were documented using the Enzian classification (Supplementary

Table 1).

Table 2.

Intraoperative parameters collected for each patient in CUSA-assisted laparoscopic excision of endometriosis.

Table 2.

Intraoperative parameters collected for each patient in CUSA-assisted laparoscopic excision of endometriosis.

| CUSA time (min) |

8.5 ± 3.0 (range 4–14) |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) |

<10 median (max 20) |

| Ease of ablation score |

1.3 ± 0.5 (range 1-2) |

| Ease of adhesiolysis score |

1.7 ± 0.7 (range 1-3) |

| Overall effectiveness score |

1.4 ± 0.6 (range 1-3) |

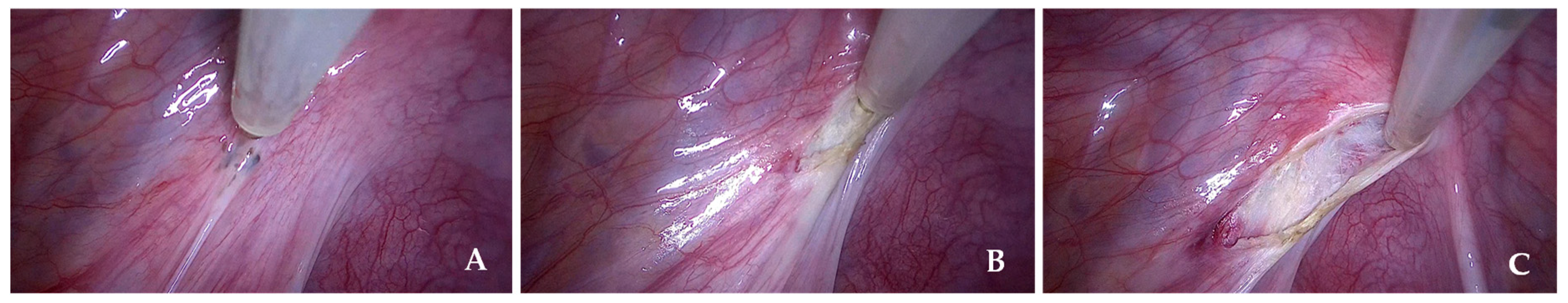

Figure 2 shows a representative intraoperative image of the CUSA from our series.

Figure 2.

Representative intraoperative images of CUSA from our series. (A) Pre-procedural view before the start of lesion excision. (B) and (C) Intraoperative views demonstrating tissue fragmentation, irrigation, and aspiration during the use of CUSA.

Figure 2.

Representative intraoperative images of CUSA from our series. (A) Pre-procedural view before the start of lesion excision. (B) and (C) Intraoperative views demonstrating tissue fragmentation, irrigation, and aspiration during the use of CUSA.

3.3. Post-Operative Course

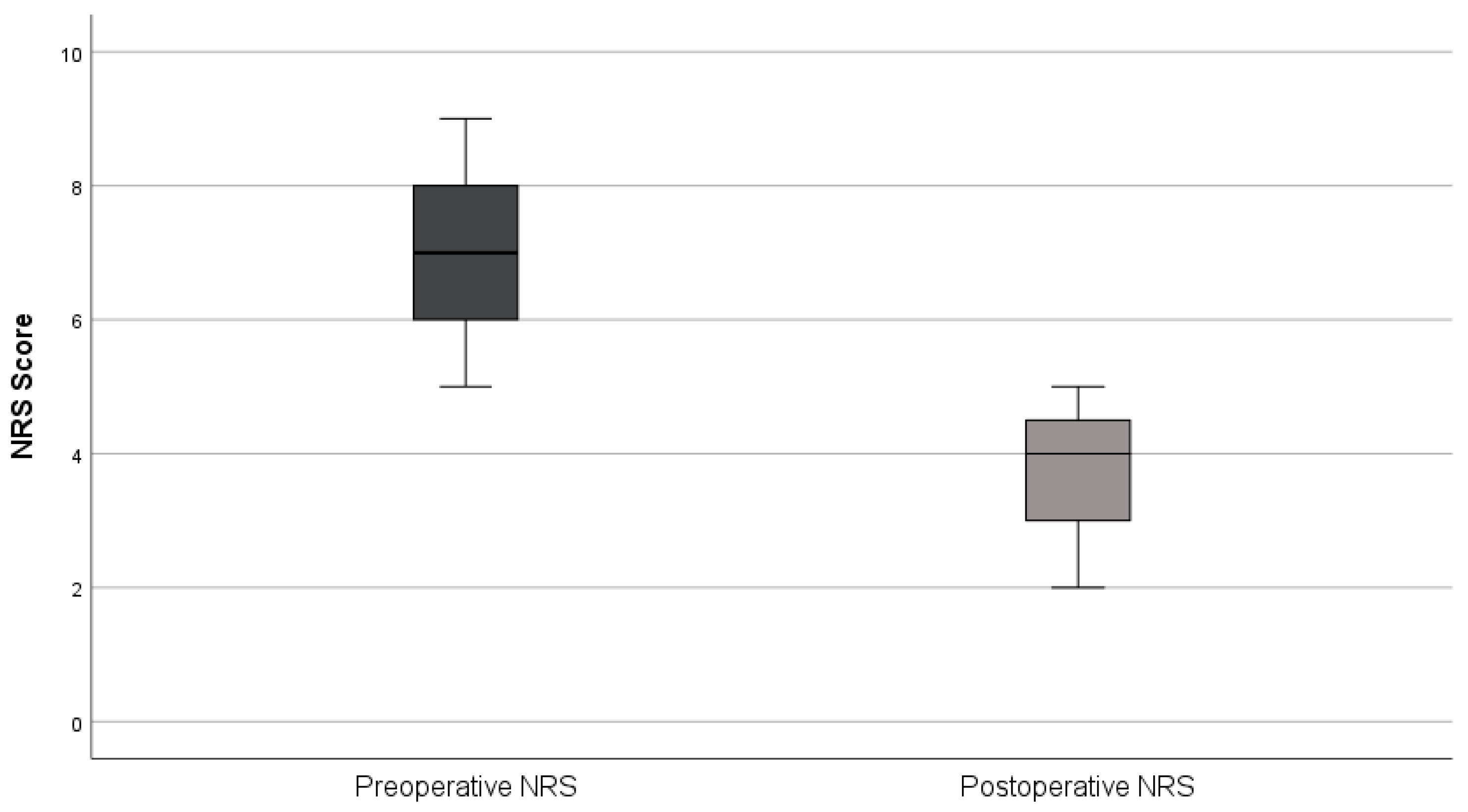

All patients were discharged after one night (median length of stay = 1 day). Daily activities were resumed within 2–3 days and return to professional activities occurred after a mean of 7 days. No early (≤30 days) or late (>30 days) postoperative complications or reoperations were observed. At the first follow-up (6–8 weeks), all patients reported improvement in preoperative symptoms, with NRS pain scores decreasing from 6.9 ± 1.4 preoperatively to 3.7 ± 1.0 postoperatively (mean reduction 3.2 points; 46%) (

Figure 3). Histopathological analysis confirmed endometriosis in all surgical specimens. Fertility outcomes were not assessed due to the limited follow-up period.

Figure 3.

Comparison of Preoperative and Postoperative Pain Scores (NRS).

Figure 3.

Comparison of Preoperative and Postoperative Pain Scores (NRS).

4. Discussion

Our findings indicate that laparoscopic excision of endometriosis using CUSA is a safe and efficient alternative to conventional energy devices, particularly in fertility-preserving surgery. Blood loss was minimal (median <10mL), operative time acceptable (mean 8.5 minutes) and no perioperative complications or reinterventions occurred. Postoperatively, symptoms improved significantly, with a mean pain reduction of 3.2 points (46%), supporting its role in minimizing bleeding while maintaining procedural efficiency and achieving symptom relief. To our knowledge, this is the first prospective series focusing exclusively on fertility-preserving laparoscopic CUSA excision for endometriosis, with no conversions and exceptionally low blood loss, distinguishing it from previous reports.

Our results, align with previous reports, demonstrate the efficacy of CUSA in gynecological surgery. Vasquez et al. reported effective lesion ablation with blood loss below 50 mL in 15 laparoscopic cases treated with a first-generation CUSA, with operative times comparable to our findings [

16]. Further reviews have highlighted similar advantages in complex adhesiolysis and cytoreductive surgery for ovarian or vaginal recurrences [

12,

13]. More recently, Hao et al. demonstrated that integrating CUSA into laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy resulted in reduced blood loss, shorter catheterization time, and decreased hospital stay, without prolonging surgery duration [

14]. These consistent outcomes reinforce the utility of CUSA in managing complex gynecological cases.

The use of CUSA in endometriosis surgery provides several advantages, particularly in patients desiring fertility preservation. The device’s ability to fragment hydrated endometriotic tissue through cavitation while sparing collagen-rich vessels and nerves reduces bleeding and minimizes the need for additional coagulation [

7]. Additionally, the continuous irrigation–aspiration system maintains a clean surgical field and dissipates heat [

7], which may explain the absence of thermal injuries observed in our cohort. Ultra-low blood loss and the lack of thermal spread are particularly important for preserving ovarian reserve and tubal function, which are crucial for fertility. In our series, the median blood loss was <10 mL, which is notably lower than that reported with conventional energy devices, where mean blood loss can reach 88.5 mL (range 82–92 mL) [

18], highlighting CUSA’s potential to minimize intraoperative bleeding. Moreover, the shorter operative duration translates into reduced anesthetic exposure and potentially lower procedural costs.

Compared to conventional energy devices, such as monopolar and bipolar electrosurgery, CUSA offers a significant advantage by minimizing thermal damage. Conventional techniques, while effective for tissue excision and hemostasis, are associated with the risk of collateral thermal injury to surrounding tissues, which is particularly important in fertility-preserving surgeries [

6]. In contrast, CUSA’s ultrasonic cavitation mechanism enables targeted tissue removal with minimal heat propagation, thereby reducing the risk of damaging adjacent anatomical structures [

7,

8]. Compared to CO₂ laser, CUSA is more widely available and cost-effective while offering similar precision and minimal thermal spread [

7,

19]. Among other advanced energy systems, plasma-based energy devices also minimize injury to adjacent structures. However, their use is associated with higher healthcare costs, mainly due to expensive consumables and maintenance requirements, which can limit their cost-effectiveness, particularly in resource-constrained settings [

20]. In this context, CUSA may represent a more cost-effective option.

CUSA has a relatively short and manageable learning curve, as demonstrated by Doron O. et al., who showed that both experienced surgeons and trainees achieved proficiency within a few attempts in a micro-neurosurgical model, aided by the device’s intuitive handling and immediate feedback from its irrigation–aspiration system [

21]. Its proven usability, together with its established role in other surgical specialties such as hepatobiliary surgery [

22], supports its broader adoption in fertility-preserving endometriosis surgery. However, its implementation in routine gynecologic practice may be limited by availability in certain centers and by higher acquisition and maintenance costs compared with conventional energy devices, which could affect accessibility and cost-effectiveness, particularly in resource-constrained settings.

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the small sample size and single-center setting may limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, as follow-up duration was relatively short, long-term outcomes related to symptom recurrence and fertility preservation could not be assessed. Finally, the subjective nature of the surgeon-reported scores could introduce observer bias, despite being performed by a highly experienced operator.

Future research should include multicenter studies with larger sample sizes to validate these findings and comparative trials assessing CUSA against other minimal thermal-spread technologies to establish its relative efficacy and safety. In addition to long-term symptom control and recurrence rates, future studies should explicitly incorporate reproductive endpoints to clarify the impact of CUSA on fertility outcomes.

Exploring CUSA integration with robotic-assisted platforms and developing dedicated nerve-sparing protocols may further enhance its applicability in complex endometriosis cases. Combining robotic precision with CUSA’s efficient tissue fragmentation and minimal thermal spread has shown promise in other complex surgeries, such as major hepatectomies, by reducing blood loss and improving dissection efficiency [

23]. However, challenges remain, particularly the need for robotic-specific CUSA tips and addressing the learning curve associated with device adaptation. Developing dedicated robotic-compatible instruments and conducting prospective studies could further optimize this approach and expand its clinical application.

5. Conclusions

CUSA provides a precise, tissue-sparing approach for endometriosis surgery, achieving minimal blood loss, reduced thermal injury, and significant pain reduction, with rapid recovery. While device setup and the learning curve remain considerations, our findings support its role as a fertility-preserving alternative to conventional energy sources and encourage its broader adoption in gynecologic surgical practice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Enzian classification by patient.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: HF; Methodology, MV and HF; Software, MV; Validation: HF; Formal Analysis, MV; Investigation, HF; Resources, HF; Data Curation, HF; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, MV; Writing – Review & Editing, MV and HF; Visualization, MV; Supervision, HF; Project Administration, HF; Funding Acquisition, none.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital da Luz, Arrábida..

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bestel, A.; Gunkaya, O.S.; Mutlu, E.A.; Saltan, T.; Çelik, H.G. What is the effect of endometriosis on the quality of life? Reproductive BioMedicine Online 2023, 47, 103552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, M.; Mohamed, S.; Saridogan, E. Safe use of electrosurgery in gynaecological laparoscopic surgery. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2020, 22, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.W.; Portenier, D.D. Bipolar Electrosurgical Devices. In The SAGES Manual on the Fundamental Use of Surgical Energy (FUSE); Feldman, L., Fuchshuber, P., Jones, D.B., Eds. Springer New York: New York, NY, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Voyles, C.R. The Art and Science of Monopolar Electrosurgery. In The SAGES Manual on the Fundamental Use of Surgical Energy (FUSE); Feldman, L., Fuchshuber, P., Jones, D.B., Eds. Springer New York: New York, NY, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa, T.; Hamamoto, S.; Gonda, M.; Taguchi, K.; Unno, R.; Torii, K.; Isogai, M.; Kawase, K.; Nagai, T.; Iwatsuki, S.; Etani, T.; Naiki, T.; Okada, A.; Yasui, T. Evaluation of thermal effects of surgical energy devices: ex vivo study. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 27365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.S. Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator. In The SAGES Manual on the Fundamental Use of Surgical Energy (FUSE); Feldman, L., Fuchshuber, P., Jones, D.B., Eds. Springer New York: New York, NY, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cimino, W.W.; Bond, L.J. Physics of ultrasonic surgery using tissue fragmentation: Part I. Ultrasound in medicine & biology 1996, 22, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Verdaasdonk, R.; Van Swol, C.; Grimbergen, M.; Priem, G. High-speed and thermal imaging of the mechanism of action of the Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator (CUSA). 1998; Vol. 3249, p 72-84.

- Epstein, F. The Cavitron ultrasonic aspirator in tumor surgery. Clinical neurosurgery 1983, 31, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takayama, T.; Makuuchi, M.; Kubota, K.; Harihara, Y.; Hui, A.M.; Sano, K.; Ijichi, M.; Hasegawa, K. Randomized comparison of ultrasonic vs clamp transection of the liver. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960) 2001, 136, 922–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aletti, G.D.; Dowdy, S.C.; Podratz, K.C.; Cliby, W.A. Surgical treatment of diaphragm disease correlates with improved survival in optimally debulked advanced stage ovarian cancer. Gynecologic oncology 2006, 100, 283–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deppe, G.; Malviya, V.K.; Malone, J.M., Jr. Use of Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator (CUSA) for palliative resection of recurrent gynecologic malignancies involving the vagina. European journal of gynaecological oncology 1989, 10, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hao, M.; Wang, Z.; Wei, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Ping, Y. Cavitron Ultrasonic Surgical Aspirator in Laparoscopic Nerve-Sparing Radical Hysterectomy: A Pilot Study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2016, 26, 594–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niwa, K.; Imai, A.; Hashimoto, M.; Yokoyama, Y.; Tamaya, T. Postoperative vesicourethral function after ultrasonic surgical aspirator-assisted surgery of gynecologic malignancies. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology 2000, 89, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez, J.M.; Eisenberg, E.; Osteen, K.G.; Hickerson, D.; Diamond, M.P. Laparoscopic ablation of endometriosis using the cavitational ultrasonic surgical aspirator. The Journal of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists 1993, 1, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, P.J.; Ahmad, N.; Dasgupta, D.; Campbell, J.; Guthrie, J.A.; Lodge, J.P. Case hepatic endometriosis: a continuing diagnostic dilemma. HPB surgery : a world journal of hepatic, pancreatic and biliary surgery 2009, 2009, 407206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magrina, J.F.; Espada, M.; Kho, R.M.; Cetta, R.; Chang, Y.H.; Magtibay, P.M. Surgical Excision of Advanced Endometriosis: Perioperative Outcomes and Impacting Factors. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology 2015, 22, 944–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nezhat, C. Advantages of CO₂ laser technology in gynecologic surgery; Lumenis Surgical: 2017.

- Nieuwenhuyzen-de Boer, G.M.; Geraerds, A.; van der Linden, M.H.; van Doorn, H.C.; Polinder, S.; van Beekhuizen, H.J. Cost Study of the PlasmaJet Surgical Device Versus Conventional Cytoreductive Surgery in Patients With Advanced-Stage Ovarian Cancer. JCO clinical cancer informatics 2022, 6, e2200076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doron, O.; Langer, D.J.; Paldor, I. Acquisition of Basic Micro-Neurosurgical Skills Using Cavitron Ultrasonic Aspirator in Low-Cost Readily Available Models: The Egg Model. World neurosurgery 2021, 151, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagano, Y.; Matsuo, K.; Kunisaki, C.; Ike, H.; Imada, T.; Tanaka, K.; Togo, S.; Shimada, H. Practical usefulness of ultrasonic surgical aspirator with argon beam coagulation for hepatic parenchymal transection. World journal of surgery 2005, 29, 899–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawksworth, J.; Radkani, P.; Nguyen, B.; Belyayev, L.; Llore, N.; Holzner, M.; Mateo, R.; Meslar, E.; Winslow, E.; Fishbein, T. Improving safety of robotic major hepatectomy with extrahepatic inflow control and laparoscopic CUSA parenchymal transection: technical description and initial experience. Surgical endoscopy 2022, 36, 3270–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).