1. Introduction

The rapid development of generative artificial intelligence has profoundly impacted various fields, including the creative industries [

1,

2]. It has enhanced workflows and creative quality while democratizing access to creative tools [

3]. With the continuous deepening of the concept of human–AI collaboration, generative artificial intelligence is now capable of performing creative tasks that traditionally required human judgment, disrupting the production models of creative work [

4]. Against this backdrop, the art market is increasingly embracing works generated by generative artificial intelligence, significantly increasing its penetration in the field of artistic creation.

Generative artificial intelligence has become a new medium for visual learning and aesthetic ability training [

5]. Specifically, many universities and art institutions have begun integrating generative AI into classroom design, thereby expanding the boundaries of traditional aesthetic education models [

6]. As a vital component of school cultivation systems, aesthetic education plays a key role in shaping students’ abilities to perceive, appreciate, and express beauty [

7]. Generative AI offers new avenues for the development of this field, and its involvement in aesthetic education represents a trend of the times. In particular, image generation models such as DALL-E 3, Midjourney, and Stable Diffusion have been applied in art and design education due to their powerful text-to-image capabilities [

8]. Meanwhile, large language models like GPT-4 and Claude 3 Opus also demonstrate artistic potential in creative guidance and theoretical output [

9].

1.1. Recent Advances in AI Painting Tools

The widespread application of generative artificial intelligence in the arts necessitates a clear understanding of its mainstream tools. As a key component, AI painting tools are reshaping the relationship between art and technology [

10]. OpenAI’s DALL-E 3 has made significant progress in the text-to-image domain, capable of generating highly detailed and high-quality images based on prompts. Meanwhile, Anthropic’s Claude 3 Opus demonstrates outstanding performance in multimodal understanding of text and images, reflecting advanced capabilities in the fusion of language and vision in AI [

11]. Midjourney, known for its ability to generate visual concepts from textual prompts, has shown a positive impact on stimulating student creativity and is recommended for promotion as an auxiliary tool [

12]. Other notable models include StyleGAN, used for generating highly realistic portrait images [

13], and Pix2Pix, commonly applied in style transfer and image restoration tasks [

14], both playing increasingly important roles in the field of visual generation.

Currently, AI painting tools are widely integrated into the creative workflows of art practitioners, serving both as powerful instruments for exploring new styles and as effective means to shorten the creative process [

15]. These tools can also be combined with emerging technologies such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) to expand the modes of artistic expression, providing users with more diverse and interactive experiences [

16]. Against this backdrop, the core of creation is no longer confined to traditional artistic skills but increasingly emphasizes language proficiency, creativity, and the understanding and application of technology [

17].

Although the field is continually advancing, AI painting remains constrained by data-driven training, which means it cannot achieve true originality [

18]. This technical limitation results in users enjoying the accessibility of AI painting while potentially feeling dissatisfied with its creative mechanisms. Studies have shown that the generated works still fail to meet users’ expectations for artistic aesthetic experience [

19]. Similarly, this also affects users’ satisfaction in personalized creation, as some users may expect greater flexibility in idea innovation [

20].

1.2. AI Painting and Aesthetic Education

AI painting tools contribute to the informatization and digital transformation of aesthetic education in schools [

16]. With their capabilities in semantic understanding and artistic creation, these tools are increasingly recognized by the educational community, providing students with rich inspirational support. Under such circumstances, traditional aesthetic education models face new opportunities [

3]. Specifically, the introduction of AI painting disrupts the technique-centered teaching logic, shifting the focus of cultivation toward cognitive training [

21]. Meanwhile, the low-threshold technical features of AI painting enable non-specialist students to participate in artistic creation, thereby promoting the popularization and diversification of aesthetic education [

22]. Aesthetic education plays an irreplaceable role in fostering students’ holistic development, and the involvement of AI painting tools will greatly broaden the scope of school-based aesthetic education.

Despite the emerging advantages of AI painting in the field of aesthetic education within higher education institutions, its acceptance and effective integration remain challenging [

23]. Existing studies indicate that user experience with AI painting tools still faces numerous obstacles [

24]. Since the advent of this technology, ethical and security concerns [

25], questions regarding the nature of art [

26], and issues surrounding human-machine relationships [

27] have continued to provoke debate. Such concerns may lead to user anxiety during practical application of the new technology [

28]. Particularly in art education, where students’ aesthetic perception and artistic practice are highly valued, the often singular output produced by AI may fail to provide a satisfactory artistic experience, potentially affecting students’ acceptance and the overall effectiveness of aesthetic education [

29]. Therefore, the adaptability of AI painting tools across diverse application scenarios remains to be validated. Although AI painting has gradually entered aesthetic education in higher education institutions, there remains a need for a systematic understanding of students’ acceptance intentions toward AI painting tools and the underlying psychological and technological influencing factors.

1.3. Extended TAM Model Perspective

The theoretical framework of this study is based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [

30]. The core variables of TAM are Perceived Usefulness (PU) and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU), which influence users’ attitudes toward using the technology and subsequently determine their actual usage behavior [

31]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that TAM is both stable and reliable, and its effectiveness has been validated across multiple fields, including education [

32,

33]. This model can assist educators in understanding students’ perceptions of system-related factors, thereby enabling more rational integration of technology into teaching contexts.

In addition, TAM possesses an inherent extensibility that allows for the incorporation of specific variables or constructs based on particular research contexts and needs [

34]. For instance, models such as TAM2 and UTAUT were developed through the extension of TAM. This flexibility is equally applicable in studies on AI technology adoption [

35]. For example, psychological and social factors have been shown to significantly influence users’ behavioral intentions toward adopting AI technologies [

36]. Some studies have integrated trust and self-efficacy into TAM and found them to be strong predictors of user acceptance [

37,

38]. Therefore, it is essential to adjust the structural relationships of the theoretical model in accordance with the specific research context.

In the context of AI painting, most scholars have highlighted the influence of performance expectancy and effort expectancy, which are typically associated with utilitarian motivation [

39]. However, the relationship between the inherent features of AI painting tools (such as the quality of generated images) and perceived usefulness, as well as their impact on user acceptance, remains insufficiently clear. Therefore, when examining AI painting systems, it is necessary to investigate their technical attributes and core artistic elements in depth and to incorporate key factors such as painting quality into the model [

40].

Moreover, the usage motivation of non-art-major students in higher education should be fully considered. As creative tools with exploratory characteristics, AI painting systems are not solely driven by efficiency. Students in higher education may place greater emphasis on the entertainment value and emotional feedback provided by such tools [

41]. Against this backdrop, intrinsic motivation becomes a crucial factor in sustaining continuous usage intentions [

42]. Consequently, variables that influence intrinsic motivation, such as hedonic motivation and AI anxiety, should also be incorporated into the model.

By extending the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) with factors specific to AI painting tools, it becomes possible to identify the key determinants influencing higher education students’ adoption of these tools. This approach can also help educators gain deeper insights into students’ preferences for AI painting systems, continuously refine instructional design, and thereby promote their rational and effective integration into aesthetic education.

1.4. Research Rationale and Objectives

Although previous studies have extensively examined the application of artificial intelligence in education, particularly in STEM and language teaching [

43,

44], there is still a lack of empirical research on AI painting tools in aesthetic education within higher education institutions. Existing literature mainly concentrates on user experience in professional fields such as fine arts and design industries [

39,

45,

46], while studies addressing non-professional users, especially among higher education students, remain relatively limited.

As the primary participants in higher education, students’ familiarity with and acceptance of AI painting tools are closely related to the cultivation of their aesthetic literacy and creative abilities [

47]. More importantly, this understanding can provide higher education institutions with a pathway for advancing aesthetic education that aligns with contemporary developments [

48]. Therefore, this study extends the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and focuses on non-design-major students in higher education as the research subjects. The aim is to gain a more systematic understanding of the application of AI painting tools in aesthetic education and to provide more reliable empirical evidence for their integration into teaching practices.

1.5. Research Questions

How do higher education students in China accept AI painting tools?

What factors influence the use of these AI painting tools among higher education students in China?

How can the application of AI painting tools in aesthetic education be optimized in light of these factors?

The following sections introduce the extended TAM model and related research hypotheses, followed by an explanation of the research methods. Subsequently, the results of data analysis are presented and discussed. Finally, the study concludes with key findings, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

2. Proposed Model and Hypotheses

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) has demonstrated stability and has been applied across multiple industries [

49]. To better address the issue of acceptance of AI painting tools, it is necessary to further extend this model. Research has shown that hedonic motivation, self-efficacy, painting quality, and AI anxiety play significant roles in influencing users’ intention to adopt technology [

50,

51,

52,

53]. Therefore, we integrated these four external variables into the original TAM framework to examine whether they affect perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEOU), and behavioral intention (BI). Overall, we identified four external variables, which, together with perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, constitute the independent variables. Behavioral intention is the dependent variable.

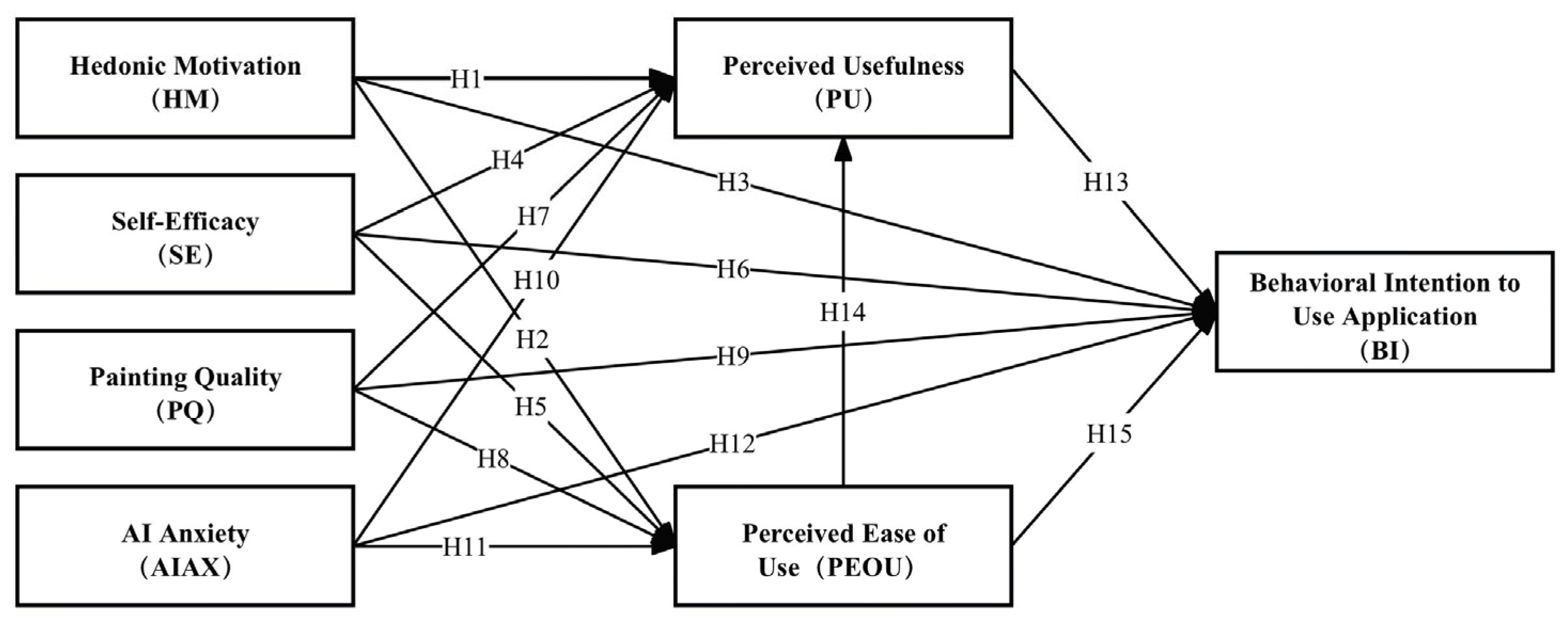

Figure 1 presents the hypothesized model of this study.

2.1. Hedonic Motivation (HM)

Hedonic motivation refers to the intrinsic driving force that enables users to experience pleasure or enjoyment when using technology [

54]. This motivation is closely related to the psychological responses triggered by behavior [

55]. Studies have shown that hedonic motivation plays an important role in users’ technology acceptance [

50]. When users engage with a specific system based on hedonic motivation, they often experience positive emotional responses, which may enhance their evaluation of the system’s usability [

56]. In other words, hedonic motivation is one of the driving forces behind users’ acceptance and continued use of the technological system [

57]. In the field of AI technology acceptance, multiple studies have emphasized the significance of hedonic motivation [

58,

59]. Its application value has been validated in various scenarios, such as intelligent painting [

19] and intelligent social robots [

60]. At present, researchers have integrated hedonic motivation into TAM to expand its applicability. For example, the Hedonic-Motivation System Adoption Model (HMSAM) was built upon TAM, incorporating hedonic factors such as pleasure and curiosity into the model to provide a deeper explanation of how intrinsic motivation influences user acceptance [

61]. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H1: Hedonic motivation will have a positive impact on the perceived usefulness of AI painting tools.

H2: Hedonic motivation will have a positive impact on the perceived ease of use of AI painting tools.

H3: Hedonic motivation will have a positive impact on the behavioral intention to use AI painting tools.

2.2. Self-Efficacy (SE)

Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s subjective assessment of their ability to complete a specific task, which is closely related to their prior experiences [

62]. Typically, individuals with high self-efficacy are more confident in handling new tasks and more willing to put in extra effort to overcome difficulties [

63,

64]. Previous studies have confirmed that self-efficacy is an important factor in assessing whether users adopt a particular technology [

65,

66]. Higher levels of self-efficacy contribute to enhanced user perceptions of technology usability [

67,

68]. Additionally, self-efficacy is regarded as a key factor in driving users’ behavioral intentions [

51,

69,

70]. In the practical application of AI, users’ usage intentions and actual behaviors are profoundly influenced by self-efficacy [

71,

72,

73]. From the perspective of Holden and Rada [

74], self-efficacy enhances users’ sense of ease in technology applications, which may further strengthen their willingness to continue using the technology. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H4: Self-efficacy will have a positive impact on the perceived usefulness of AI painting tools.

H5: Self-efficacy will have a positive impact on the perceived ease of use of AI painting tools.

H6: Self-efficacy will have a positive impact on the behavioral intention to use AI painting tools.

2.3. Painting Quality (PQ)

In aesthetic evaluations, the assessment of painting quality is often influenced by the subjective perspectives of the observer [

75]. Based on existing research, “color,” “composition,” and “meaning and content” are usually important dimensions for evaluating painting quality [

76]. Currently, literature that incorporates painting quality into technology acceptance research is relatively scarce, but some studies suggest a significant relationship between perceived aesthetic quality and perceived usability, although this relationship may be influenced by individual cognitive styles [

77,

78]. Notably, in the field of AI-generated art, the images it produces are sometimes even more popular than those created by human designers [

79,

80]. This high appraisal may further enhance users’ perception of usability. Therefore, we have reason to believe that the higher the quality of images generated by AI painting tools, the better [

77,

78] the users’ perceptual experience will be [

81]. Additionally, research has shown that participants exhibit higher engagement in experiences with high-quality images [

52]. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed in this study:

H7: Painting quality will have a positive impact on the perceived usefulness of AI painting tools.

H8: Painting quality will have a positive impact on the perceived ease of use of AI painting tools.

H9: Painting quality will have a positive impact on the behavioral intention to use AI painting tools.

2.4. AI Anxiety (AIAX)

AIAX is defined as an emotional fear response, characterized by users’ concerns about the unknown impacts of AI and its applications on human society [

82,

83]. AIAX plays a crucial role in shaping users’ attitudes toward adopting AI technologies and tools [

84]. It can be viewed as an antecedent factor influencing behavioral intention and actual behavior. It is essential to distinguish anxiety from a purely negative attitude. As a subjective emotional reaction, anxiety can, in some cases, have a facilitating effect, leading to positive behavioral attitudes and outcomes [

85]. However, in the context of AI, anxiety has been demonstrated to negatively impact perceptions of usability and inhibit behavioral attitudes [

86,

87]. In the AIGC domain, concerns about privacy, transparency, creative autonomy, and technological complexity are significant anxiety triggers [

28,

88]. These concerns may lead to more negative behavioral attitudes toward AI applications [

53,

89]. Based on these insights, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H10: AI anxiety will have a negative impact on the perceived usefulness of AI painting tools.

H11: AI anxiety will have a negative impact on the perceived ease of use of AI painting tools.

H12: AI anxiety will have a negative impact on the behavioral intention to use AI painting tools.

2.5. Perceived Usefulness (PU)

Davis [

30] defined perceived usefulness as the user’s evaluation of the utility of a specific system. As one of the core components of TAM, it has been widely applied in research on user acceptance [

90,

91,

92]. In this study, we use perceived usefulness to measure the extent to which users believe AI painting tools can enhance their painting skills. Research has shown that this factor plays a crucial role in users’ intention to use and actual behavior [

93,

94]. This has also been validated in studies related to AI painting [

95,

96]. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H13: Perceived usefulness will have a positive impact on the behavioral intention to use AI painting tools.

2.6. Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU)

Perceived ease of use refers to the degree to which users believe they can operate a specific system without having to exert additional effort [

30]. In this study, we use this factor to measure users’ perceived ease of using AI painting tools. As a core element in user acceptance research, perceived ease of use not only promotes perceived usefulness but also enhances users’ intention to use and actual behavior [

97]. This has been repeatedly confirmed in studies of AI technology acceptance [

98,

99]. With the widespread application of automation and intelligent technologies, ease-of-use standards may become increasingly important in technology acceptance research [

100]. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H14: Perceived ease of use will have a positive impact on the perceived usefulness of AI painting tools.

H15: Perceived ease of use will have a positive impact on the behavioral intention to use AI painting tools.

2.7. Behavioral Intention (BI)

Behavioral intention refers to the psychological tendency or state that users exhibit before using a specific system [

30]. This factor can directly influence whether users will use the system [

100,

101]. In this study, behavioral intention is treated as a dependent variable, primarily used to assess users’ willingness to use AI painting tools. Research has found that users’ attitudes toward AI technology significantly impact their actual behavior [

102]. Through an in-depth analysis of users’ behavioral intentions, we can more accurately predict their actual behavior and provide valuable insights for technological improvement.

3. Method Design

3.1. Materials

The experimental material we used is the AI painting tool MidJourney. Released in 2022, this product has provided a broad user base with the opportunity to participate in artistic creation. Based on a diffusion model, MidJourney offers users multiple functions, including high-precision semantic generation, controllable parametric output, batch generation, and intelligent filtering. Even users without a background in drawing can generate high-quality artwork by inputting prompts. As a representative application of AI technology in the field of art, works created by MidJourney have won multiple awards in professional fields. For instance, at the 2022 Colorado State Fair, the AI-generated piece “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial” won first place in the “Digital Art” category. As of now, the official MidJourney server has registered over 20 million members, attracting attention and usage from users worldwide.

3.2. Development of the Survey Questionnaire

The survey questionnaire consists of two parts. The first part includes demographic information such as gender, age, educational level, relevance of major, and familiarity with the subject. The second part focuses on users’ level of agreement with the AI painting tool’s HM, SE, PQ, AIAX, PU, PEOU, and BI, covering seven dimensions in total. To assess the validity of each item and the conceptual framework, we designed the questionnaire template based on a standardized format. Shorter questionnaires are often more appealing than those with too many items, as they tend to generate higher-quality feedback [

103]. In fact, short questionnaires can provide psychometric results comparable to traditional longer ones [

104]. Therefore, this survey was simplified while ensuring that each dimension in the structural equation model (SEM) contained 3 to 4 factors for analysis. The study included 15 items, with responses on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “1” (strongly disagree) to “7” (strongly agree). The four items measuring the external variable HM (e.g., “I enjoy interacting with this AI painting tool”) were adapted from Alenezi et al. [

105], Venkatesh et al. [

54], Lu et al. [

106], and Wang and Chuang [

107]. The four items measuring SE (e.g., “I am confident in operating this AI painting tool”) were selected from Liaw [

108]. The four measurement items of PQ (e.g., “I think the artwork created by this AI drawing tool is attractive”) were adapted from Li and Chen [

76] and Moshagen and Thielsch [

109]. The three items of AIAX (e.g., “I worry that this AI drawing tool may make us dependent on it”) were selected from Wang and Wang [

83]. In addition, PU (e.g., “I think using this AI drawing tool will improve my drawing ability”), PEOU (e.g., “I think I can quickly learn to use this tool”), and BI (e.g., “The effect of this AI drawing tool left a deep impression on me”) from the original TAM model were adopted from Davis et al. [

110]. After screening and wording adjustments, these items meet the requirements of the survey. For detailed questionnaire content, see

Appendix A.

3.3. Pilot Study

The factors used in our model have been applied in multiple fields. We invited five experts to evaluate the structure and candidate items. These experts are researchers in the field of user experience and professionals in digital product design. They were asked to review whether the content and concepts of the items aligned and assess their accuracy and clarity. The expert panel provided several recommendations, including focusing the PEOU items on ease of use and removing three candidate items: “I think this AI painting tool is easy to learn and operate,” “I think the interface of this AI painting tool is clear and understandable,” and “I think this AI painting tool can easily achieve my goals.” The experts pointed out that the relevance of the deleted items was low within the group, which could lead to unclear research results. Regarding the demographic factors, the experts recommended merging the age options for participants over 30. Additionally, they suggested adding a brief operational flow in the software introduction section to help users better understand how to use it. The materials used in this study are detailed in

Appendix B.

After the preparation of the materials, we conducted a pretest with ordinary users to verify the clarity of the item statements and the rationality of the structure. We randomly selected 57 higher education students from non-design majors to participate, and all participants completed the survey. Most participants took between 2 and 6 minutes to complete the survey and indicated that the items were easy to understand. Among them, five participants found the statement “I think using this painting tool is useful” in the PU dimension too vague, so we modified it to “I think using this painting tool is useful for improving drawing skills.” Additionally, six participants felt that the statement “I think using this AI painting tool will improve my drawing efficiency” was somewhat obscure and similar to the items in the PEOU dimension, so we decided to remove this item. Overall, we accepted the participants’ reasonable feedback. After the expert suggestions and pretest phase, we finalized the structure and items of the questionnaire.

3.4. Participants

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of School of Design of Hunan University (protocol code 2024001). In China, aesthetic education in higher education institutions has increasingly emphasized integration with digital technologies, especially under the impetus of AI development, showing a multidimensional trend [

48]. The survey questionnaire combined both online and offline methods and primarily targeted the higher education student population. The participants consisted of a group of higher education students from China, aged between 18 and 30 years, attending four-year universities and three-year vocational colleges. Before participating in the survey, all respondents signed an informed consent form. A total of 350 valid responses were received, with a participation rate of 87.5% out of 400 participants. Thirty-three samples were removed for not meeting the screening criteria, which included completion times under 1 minute (n=13), response repetition rates over 85% (n=20), missing data (n=0), and data identified as outliers in the SPSS analysis (n=0). Therefore, 317 valid samples remained, with an effective rate of 90.6%. Since the total sample size exceeded 100 (150 being the optional sample size), reliable CB-SEM analysis results can be obtained [

111,

112]. Demographic data show that 159 participants were male and 158 were female. The participants’ ages were mostly between 18 and 25 years, accounting for 87.7%. Although the study focused on non-design majors, three participants with design-related backgrounds were retained in the sample due to their minor proportion (less than 1%) and negligible influence on the overall results. Descriptive statistics of the sample are shown in

Table 1.

3.5. Procedure

The study distributed questionnaires through both online and offline channels. Online distribution primarily occurred via social media platforms such as Weibo and WeChat, while offline distribution focused on school libraries, study rooms, and break-time classrooms. First, participants were provided with an introduction to the experiment and were required to sign an informed consent form. Next, they accessed the questionnaire interface by scanning a QR code and were introduced to the tool through an instructional video. Participants then followed the video tutorial to access the experimental tool and engaged in theme-based painting creation for 20 minutes. Upon completing their artwork, participants submitted their final creations. Finally, they completed the questionnaire through the provided link. After confirming that the data was complete, each participant received a reward of 5 RMB.

4. Results

In this study, data analysis was conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS v27) and structural equation modeling (SEM) software (AMOS v26). Before this, all samples were screened to ensure data completeness and the absence of invalid entries. First, the Jarque-Bera (skewness-kurtosis) test was used to examine the normality of the data. Typically, skewness and kurtosis values are considered normal if they fall within the range of ±2.58 [

113]. Based on this criterion, all items in the dataset passed the normality test and exhibited a normal distribution (i.e., <±2.58). This assumption was further validated through SEM. According to Li et al. [

114], SEM not only accounts for measurement error but also analyzes relationships among multiple constructs. Therefore, SEM was employed to verify whether the proposed model effectively explains higher education students’ acceptance of AI painting tools and to further explore the effects of HM, SE, PQ, and AIAX on users’ PEOU, PU, and BI.

4.1. Measurement Model (MM)

In this study, a measurement model was used to assess the relationship between observed variables and latent variables [

115,

116]. First, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted on the observed variables. The results showed that the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was 0.906, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a p-value of less than 0.001. According to Hutcheson and Sofroniou [

117], these variables were suitable for factor analysis. Subsequently, principal components were extracted using Varimax rotation, resulting in seven factors that explained 81.307% of the total variance. The findings indicated a high degree of fit between the measurement items and their respective factors. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.835 to 0.957, all exceeding 0.8, as shown in

Table 2.

4.2. Structural Model (SM)

After completing the EFA analysis, CFA was conducted to examine the fit between the data and the conceptual model, focusing on convergent validity, discriminant validity, and overall model fit. Specifically, convergent validity reflects the correlation between theoretical constructs and their actual measurements [

118]. According to the recommendations of Fornell and Larcker [

119], the results of convergent validity should meet the following criteria: (1) construct reliability should reach the recommended threshold of 0.80, and (2) the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct should exceed the variance explained by measurement error, with AVE values greater than 0.5. All data presented in

Table 2 met these criteria, indicating good internal consistency of the model.

Discriminant validity can be confirmed by examining whether the square root of each construct’s AVE is greater than its correlation with other constructs [

119]. As shown in

Table 3, the square root of the AVE for all constructs exceeds the estimated correlations with other constructs. This indicates that each construct is not significantly correlated with other measured constructs. Therefore, the results of this study demonstrate good discriminant validity [

119].

To verify the fit of the SEM model, multiple fit indices need to be considered, including χ²/df, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), and non-normed fit index (NNFI). When χ²/df values fall between 1 and 3, RMSEA is below 0.08, AGFI exceeds 0.80, and NFI, NNFI, and CFI are all above 0.90, the model can be considered well-fitted [

112,

120]. As shown in

Table 4, the model structure in this study is acceptable.

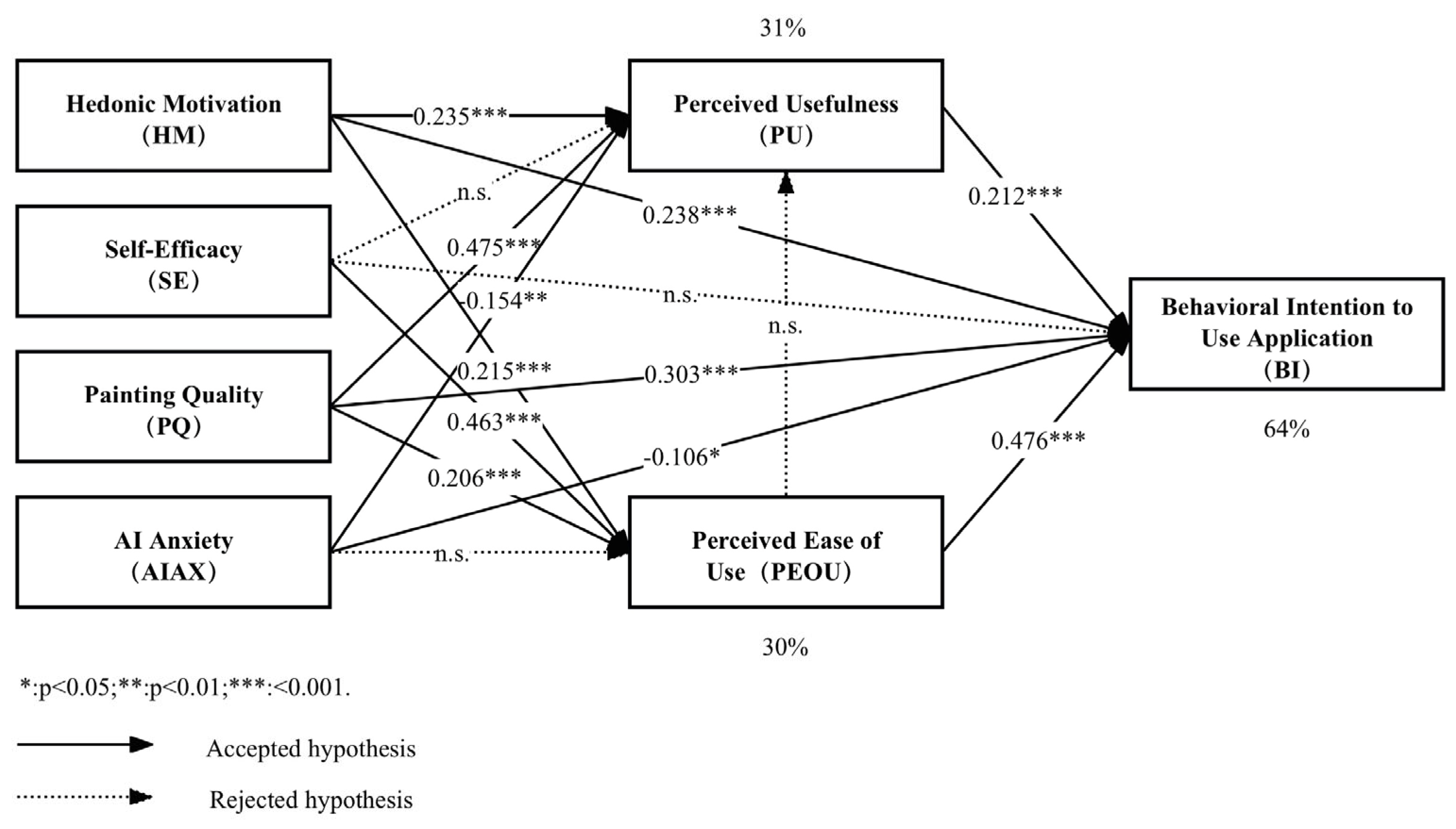

4.3. Path Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

This study explored the relationships between constructs using SEM and conducted hypothesis verification. All hypotheses were supported except for H4, H6, H11, and H14. The results are summarized in

Table 5 and

Figure 2. The results showed that HM significantly influenced PU, PEOU, and BI (β=0.235, CR=4.328, p < 0.001; β=0.215, CR=4.014, p < 0.001; β=0.238, CR=4.847, p < 0.001), supporting H1, H2, and H3. SE had a significant effect on PEOU (β=0.463, CR=8.063, p < 0.001) but no significant effect on PU and BI (β=0.012, CR=0.194, p > 0.05; β=-0.055, CR=-1.044, p > 0.05), supporting H5 but not H4 and H6.PQ significantly influenced PU, PEOU, and BI (β=0.475, CR=8.184, p < 0.001; β=0.206, CR=3.766, p < 0.001; β=0.303, CR=5.359, p < 0.001), supporting H7, H8, and H9. AIAX had a significant impact on PU and BI (β=-0.154, CR=-2.839, p < 0.01; β=-0.106, CR=-2.275, p < 0.05) but not on PEOU (β=0.019, CR=0.346, p > 0.05), supporting H10 and H12 but not H11.The relationships among the original TAM constructs (PU, PEOU, BI) were partially significant. Both PU and PEOU significantly influenced BI (β=0.476, CR=7.55, p < 0.001; β=0.212, CR=3.748, p < 0.001), supporting H13 and H15. However, PEOU did not significantly affect PU (β=0.025, CR=0.381, p > 0.05). The variance structure is shown in

Figure 2.

HM, SE, PQ, AIAX, PU, and PEOU collectively explained 64% of the variance in BI. HM, SE, PQ, AIAX, and PEOU together accounted for 31% of the variance in PU. Additionally, HM, SE, PQ, and AIAX explained 30% of the variance in PEOU.

4.4. Differences Among Demographic Characteristics

There were no significant differences in PQ and AIAX between genders. However, HM, SE, PU, PEOU, and BI showed significant differences between genders (t=3.679, p<0.01; t=4.582, p<0.01; t=1.976, p<0.05; t=4.343, p<0.01; t=4.311, p<0.01). No significant differences were found across all dimensions based on age. Additionally, SE, PQ, and PEOU exhibited significant differences based on participants’ familiarity with AI painting (F=5.696, p<0.001; F=5.673, p<0.001; F=4.687, p=0.001). There were no significant differences in HM, AIAX, PU, and BI based on familiarity with AI painting. The three-line tables comparing demographic differences are presented in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

5. Discussion

This study extended and deepened the TAM model. Based on the original TAM framework (including PU, PEOU, and BI), four external factors were introduced: hedonic motivation, self-efficacy, painting quality, and AI anxiety. The analysis results showed that out of the fifteen hypotheses, eleven were validated, while the remaining four were rejected. Except for the relationship between PEOU and PU, all other relationships within the original TAM were supported. These findings are partially consistent with existing research conclusions on AI systems but also reveal certain differences. Overall, our data validated the acceptance model for AI painting tools.

5.1. Hedonic Motivation

This study found that HM significantly and positively influenced PU, PEOU, and BI (β=0.235, CR=4.328, p < 0.001; β=0.215, CR=4.014, p < 0.001; β=0.238, CR=4.847, p < 0.001). In other words, when users have higher hedonic motivation, they perceive AI painting tools as more useful and easier to use, thereby demonstrating a stronger intention to use them. In other words, hedonic motivation affects usability, which in turn influences usage intention. This result is consistent with previous studies [

45,

121,

122,

123]. The possible reasons are as follows:

(1) Although this system is an AI painting learning tool, its hedonic attributes should not be overlooked. Research shows that while most products are usable, they often lack fun, and fun is a key factor in promoting a positive user experience [

124]. Hedonic motivation can stimulate users’ interest and positive emotions towards new technologies, leading to higher expectations and acceptance of the technology. When users are in a pleasant emotional state, they are more likely to overlook the complexity or potential obstacles in the usage process, thus achieving higher satisfaction. This internal connection enhances the user’s intention to use the system [

125,

126].

(2) Unlike traditional painting, which requires a large amount of time and effort, AI painting imposes almost no requirements on the user’s drawing skills, as users only need to input text to generate images. This low-barrier creative process allows non-professional users to focus more on enjoying the creation process itself, rather than worrying about skill deficiencies or poor results. At the same time, AI painting can quickly produce images and provide immediate psychological feedback to the user. This experience not only meets their entertainment needs but also further enhances their evaluation of the system’s usability [

19].

(3) For functional products, while usability is usually an important factor in determining user engagement, in practice, a sense of accomplishment at different stages can significantly enhance learning motivation [

127]. This sense of achievement leads users to focus more on the satisfaction brought by successful creation rather than specific operational issues, which may cause them to overlook usability problems. However, when this sense of accomplishment is replaced by fun, users’ overall evaluation of the system may further improve. Studies have shown that fun, as a more direct emotional driving factor, has a greater effect on enhancing usability [

128]. Therefore, when users prioritize pleasant experiences, the emotional feedback they receive often provides a more immediate motivating effect.

5.2. Self-Efficacy

This study found that SE significantly positively affects PEOU (β=0.463, CR=8.063, p < 0.001). In other words, when users have high confidence in using the AI drawing tool, they also perceive it as easier to use. This is consistent with most research on technology acceptance [

73,

129,

130].

Interestingly, we found that SE has no significant effect on PU and BI (β=0.012, CR=0.194, p > 0.05; β=-0.055, CR=-1.044, p > 0.05). Users do not necessarily perceive the AI drawing tool as useful or desire to use it simply because they are confident in operating the tool. This supports the findings of Esiyok et al. [

131] and of Falebita and Kok [

132]. This could be because the participants were predominantly non-design major higher education students, whose self-efficacy only affects their initial self-assessment, while their ultimate willingness to use the tool depends on their actual needs. The reasons may be:

(1) Non-design students’ primary needs for AI painting tools in their academic or daily activities often focus on completing specific tasks (such as academic reports or project presentations) rather than long-term usage or in-depth exploration [

133]. Due to the time constraints of these tasks, users rarely have the opportunity to accumulate experience through repeated practice and thus develop self-efficacy with the system. Moreover, the completion of short-term tasks often depends on the direct functionality of the tool rather than the user’s in-depth mastery. The mismatch between the short-term nature of these needs and the gradual development process of self-efficacy may be the direct reason why SE has no significant impact on PU and BI.

(2) Non-design students focus more on the basic functions of AI painting tools rather than their complex applications [

134]. When they perceive that their limited professional skills prevent them from fully utilizing the tool’s potential, the impact of SE on PU and BI may diminish. In other words, due to their lack of confidence in handling complex operations, they may be more inclined to perceive it as a low-threshold drawing tool rather than a platform for efficient artistic creation, which also weakens the role of SE in the entire process.

(3) For students lacking a design background, the emergence of PU and BI may not solely depend on their confidence in operating the tool [

131]. The entertainment attributes of AI painting tools may stimulate users’ non-utilitarian motivations, leading them to explore or use the tool out of curiosity or for entertainment purposes [

41]. In this case, PU and BI are likely to be more influenced by these additional factors, which weakens the impact of SE.

5.3. Painting Quality

This study found that PQ had a significant positive impact on PU, PEOU, and BI (β=0.475, CR=8.184, p < 0.001; β=0.206, CR=3.766, p < 0.001; β=0.303, CR=5.359, p < 0.001). This means that when users perceive the image quality generated by AI painting tools as higher, they tend to enhance their evaluation of the tool’s usefulness and further develop a stronger intention to use it. This result is supported by Jiang et al. [

135] and Wang et al. [

136]. The possible reasons are as follows:

(1) Users’ aesthetic perception of the artwork influences their evaluation of the tool’s usability [

137]. This phenomenon can be explained by the attractiveness bias. In other words, when people perceive a product as highly attractive, they tend to consider it more practical [

138,

139]. This cognitive bias unconsciously leads users to overlook the potential shortcomings of AI painting tools, thereby generating a stronger intention to use them.

(2) The high-quality images generated by AI painting tools meet users’ needs in artistic creation. Particularly for non-design students, they may lack the foundational skills in painting and thus be unable to experience true satisfaction in their creations. However, AI painting tools can quickly generate images that align with users’ needs, and this immediate and effective feedback enhances users’ perceived usability and intention to use the tool [

140].

(3) The creations of AI painting tools exhibit a high degree of shareability. Users participate in the painting process by inputting prompts and, despite lacking professional expertise, develop a sense of ownership, perceiving the results as “my work.” Moreover, AI painting technology excels in deconstructing and reconstructing existing elements, thereby creating surreal visual effects. In this context, users’ needs for creative expression are fully satisfied, leading to an increased dependence on the tool [

141]. It is worth emphasizing that higher education students tend to exhibit a stronger inclination toward personalized self-expression. AI painting, by offering functions such as image stylization and convenient sharing channels, meets their diverse expressive needs. Consequently, their perceived usefulness and behavioral intention toward the tool are also enhanced.

5.4. AI Anxiety

This study found that AIAX significantly and negatively affects PU and BI (β = -0.154, CR = -2.839, p < 0.01; β = -0.106, CR = -2.275, p < 0.05). This means that when users experience anxiety about AI technology, their perceived usefulness of the tool and usage intention significantly decrease. This finding validates the research results of Li [

46] and Du et al. [

39]. A possible explanation is that AI anxiety amplifies users’ perceptions of technological complexity and potential risks, leading to a sense of resistance even before using the tool. This psychological state may persist throughout the entire usage process and negatively impact users’ perceived usefulness and usage intention.

Interestingly, AIAX does not appear to have a significant effect on PEOU (β=0.019, CR=0.346, p > 0.05). This indicates that users’ perception of ease of use is not entirely determined by AI anxiety. The possible reasons are:

(1) Users’ perception of ease of use primarily stems from their direct experience with operational complexity rather than specific emotions or psychological expectations [

142]. Even if they have concerns about AI technology, as long as they find the actual operation of the tool to be simpler than expected, they may still perceive it as highly easy to use. Therefore, users’ firsthand experience may mitigate the negative impact of AI anxiety on ease-of-use evaluation.

(2) Users’ concerns about the potential risks of AI technology or doubts about the reliability of its output may lead to AI anxiety. Specifically, users may worry that AI-generated artworks lack originality, fail to meet specific needs, or pose privacy risks at the technical level [

89,

143]. While these concerns directly affect users’ overall assessment of the system’s value, they have little impact on judgments made during the actual usage process. Therefore, even in the presence of anxiety, users may still quickly adapt to the operation and not transfer their negative emotions to evaluations of operational difficulty.

(3) For non-design major students, the semantic generation and convenient adjustment functions provided by AI painting tools are sufficient to meet their creative needs, allowing them to maintain their perception of ease of use even under AI anxiety [

144]. These users are typically more dependent on the tool’s functionality and less tolerant of complex interactions, so the interference of anxiety on their perceived ease of use is therefore limited.

5.5. Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use

The structural relationships in the original TAM model remain significant. The study found that both PU and PEOU had a significant impact on BI (β=0.476, CR=7.55, p < 0.001; β=0.212, CR=3.748, p < 0.001), but PEOU had no significant impact on PU (β=0.025, CR=0.381, p > 0.05). This suggests that users’ perception of the usefulness of AI painting tools is not based on ease of use. Sagnier [

145] supports this view. Based on our findings, we speculate that this may be due to the following reasons:

(1) As a functionality-driven product, even if difficult to use, it can still address users’ rigid needs [

146]. In the case of participants who have no background in drawing, AI painting tools can resolve the problem of difficulty in getting started with drawing. Users are more concerned with whether the AI drawing tool can meet their creative goals and generate high-quality artwork rather than how easy it is to operate. Therefore, their perception of usefulness is more based on the functional operation and output results, which leads to a weaker impact of perceived ease of use on perceived usefulness.

(2) The automation and intelligence of AI drawing naturally lead users to assume its operation is convenient [

19]. In the research results, the ease-of-use score was higher than the usefulness score, with an average of 4.78 compared to 4.13 for usefulness. As users become more familiar with the AI drawing tool, they gradually adapt to its operating process. This low-cost learning model neutralizes the impact of initial operational difficulty on the perception of usefulness. Therefore, users do not increase their perception of usefulness as they gain more familiarity or experience.

5.6. Differences Between Demographic Characteristics

We found significant differences in HM, SE, PU, PEOU, and BI across genders (t=3.679, p<0.01; t=4.582, p<0.01; t=1.976, p<0.05; t=4.343, p<0.01; t=4.311, p<0.01). The results indicate that, except for the AIAX dimension, males generally scored higher than females. The most significant difference between males and females was observed in the SE dimension. This suggests that males perceive AI painting tools more positively and exhibit a stronger willingness to accept them. The findings of Wang [

147] and Cai et al. [

148] support this result, as their studies indicate that males demonstrate a higher acceptance of new technologies. A possible explanation is that females are more prone to anxiety when encountering new technologies, which may be related to socialization factors or technological experience [

149]. In contrast, males tend to exhibit a higher level of hedonic motivation or interest in using new technologies [

150]. This may effectively mitigate their potential anxiety and enhance their confidence in using the product. As a result, even when they encounter difficulties during operation, they are more willing to make efforts to overcome them. This significantly enhances their perceived usefulness of the tool and their intention to use it.

In addition, SE, PQ, and PEOU showed significant differences based on the level of understanding of AI painting (F=5.696, p < 0.001; F=5.673, p < 0.001; F=4.687, p = 0.001). Specifically, understanding positively influenced SE and PEOU. This indicates that users’ familiarity with AI painting tools affects their confidence in using the tool and their ease-of-use evaluation. This may be because a clear understanding of the working principles can reduce concerns about the potential complexity of new technologies, leading users to perceive the technology as easier to master. Interestingly, we found a negative impact of understanding on PQ, suggesting that the more familiar users are with the technical advantages of the tool, the stricter their requirements for the final output quality. In other words, if users are aware of the tool’s capabilities in terms of generation quality and diversity, they tend to have higher aesthetic expectations [

151]. In contrast, users who are not familiar with the tool may be more easily satisfied with AI-generated images.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Work

This study aims to examine the acceptance of AI painting tools among higher education students and the factors influencing their adoption. The results indicate that four external variables based on the extended TAM—hedonic motivation (HM), self-efficacy (SE), painting quality (PQ), and AI anxiety (AIAX)—affect higher education students’ perceived usefulness and behavioral intention to varying degrees. Overall, this research extends the TAM and provides empirical evidence to guide educators in effectively integrating AI painting tools into aesthetic education contexts.

The results indicate that HM and PQ have significant effects on PU, PEOU, and BI. This suggests that when introducing AI painting tools into aesthetic education, educators should emphasize students’ intrinsic interest and interactive experiences. At the same time, improving the quality of AI-generated artworks can enhance students’ perceived usefulness and behavioral intention. In addition, the study confirms the positive influence of SE on PEOU, indicating that educators should focus on the guidance of technology to improve students’ sense of achievement when using AI painting tools. Students may be encouraged to explore and express freely, and their confidence can be strengthened through task-based mechanisms.

The study confirmed that AIAX has a significant negative impact on both PU and BI. This finding highlights the need for educators to address students’ potential technology anxiety and guide them in developing a healthy human-machine relationship. Introducing the generative logic of AI-based painting to students may effectively reduce their anxiety toward emerging technologies. Consistent with previous studies, PU and PEOU continue to exert significant effects on BI in this research. This suggests that perceived usability remains a critical factor in the pedagogical application of AI painting tools. Furthermore, the results indicate that gender and AI literacy level exhibit significant differences across multiple paths. Therefore, individual differences should be carefully considered when integrating AI painting tools into art education settings, as they play a crucial role in the acceptance process.

This study has certain limitations. First, the findings did not reveal significant relationships between self-efficacy (SE) and perceived usefulness (PU) or behavioral intention (BI), nor between perceived ease of use (PEOU) and PU in the context of using AI-based painting tools. These relationships warrant further investigation. Second, the questionnaire-based data collection is inherently subjective and may carry potential biases. Moreover, most participants in this study held undergraduate degrees, and they may be more concerned with the entertainment value of the software. However, it is worth noting that postgraduate students also showed interest in AI painting tools. Compared with undergraduates, they may not focus solely on the entertaining aspects of such tools [

152]. Therefore, it is necessary to acknowledge that the findings of this study may not fully reflect the acceptance of AI painting tools among higher education students across all academic levels in China.

Moreover, this model is based on TAM. While the simulation results demonstrate strong explanatory power, they also indicate that some important variables may have been overlooked. For example, social influence plays a crucial role among younger users, who are often influenced by their peers [

153]. Likewise, cultural differences can impact users’ acceptance of AI technologies [

154]. Although this study expands the traditional model, additional factors affecting AI painting tool adoption have not been fully considered and warrant further exploration. Integrating other models, such as UTAUT and AIDUA, could offer a broader perspective on AI technology acceptance. Additionally, it is important to note that this study examines behavioral intention rather than actual usage behavior, which deviates from the original TAM framework. Since behavioral intention does not always translate into concrete actions [

155], the findings should be interpreted with caution.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z., Y.H.W., Z.R.L.; methodology, Y.Z., Y.H.W.; software, Y.Z., Z.W.; validation, Y.Z., N.M.; formal analysis, Y.Z., Y.H.W.; investigation, Y.Z., Y.H.W., Z.W.; resources, Z.R.L., N.M.; data curation, Y.Z., Y.H.W; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., Y.H.W., Z.R.L., Z.W.; visualization, Y.Z., Z.W., N.M.; supervision, Z.R.L.; project administration, Z.R.L.; funding acquisition, Z.R.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of School of Design of Hunan University (protocol code 2024001).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HM |

Hedonic Motivation |

| SE |

Self-Efficacy |

| PQ |

Painting Quality |

| AIAX |

AI Anxiety |

Appendix A

| Structures |

Items |

Statements |

References |

| Hedonic motivation(HM) |

HM1 |

I enjoy the process of interacting with this AI painting tool. |

[105];

[54];

[106];

[107] |

| HM2 |

Interacting with this AI painting tool is fun. |

| HM3 |

Interacting with this AI painting tool is pleasant. |

| HM4 |

The actual interaction process with this AI painting tool is comfortable. |

| Self-efficacy(SE) |

SE1 |

I am confident in operating this AI painting tool. |

[108] |

| SE2 |

This AI painting tool is not difficult for me. |

| SE3 |

I have the ability to complete tasks using this AI painting tool. |

| SE4 |

I believe I can complete AI painting on my own. |

| Painting quality(PQ) |

PQ1 |

I find the works created by this AI painting tool to be attractive. |

[76,109] |

| PQ2 |

I find the colors in the works created by this AI painting tool to be harmonious. |

| PQ3 |

I find the composition of the works created by this AI painting tool to be reasonable. |

| PQ4 |

I find the works created by this AI painting tool to be vivid. |

| AI anxiety(AIAX) |

AIAX1 |

I worry that this AI painting tool may cause dependency. |

[83] |

| AIAX2 |

I worry that this AI painting tool may lead to the degradation of our painting abilities. |

| AIAX3 |

I worry that the works created by this AI painting tool may not match my expectations. |

| Perceived usefulness(PU) |

PU1 |

I believe using this painting software is useful for improving my painting skills. |

[110] |

| PU2 |

I believe using this AI painting tool will improve my painting abilities. |

| PU3 |

I believe using this AI painting tool will improve my painting expression. |

| Perceived ease of use(PEOU) |

PEOU1 |

I believe I can learn this software quickly. |

| PEOU2 |

I believe the interface of this software facilitates quick identification and use. |

| PEOU3 |

I believe this AI painting tool can help me achieve my goals quickly. |

| PEOU4 |

I believe the interface of this software makes it easy for me to master quickly. |

| Behavioral intention (Bl) |

BI1 |

The results of this AI painting tool left a deep impression on me. |

| BI2 |

I believe this AI painting tool is a valuable tool. |

| BI3 |

I am very satisfied with the works created by this AI painting tool. |

| BI4 |

I believe using this AI painting tool for creation is worthwhile. |

References

- Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Abdalla, S.; Mogaji, E.; Elbanna, A.; Dwivedi, Y. K. The impending disruption of creative industries by generative AI: Opportunities, challenges, and research agenda. 2024, 79, 102759.

- Balasubramaniam, S.; Chirchi, V.; Kadry, S.; Agoramoorthy, M.; Gururama, S. P.; Satheesh, K. K.; Sivakumar, T. The road ahead: emerging trends, unresolved issues, and concluding remarks in generative AI—a comprehensive review. International Journal of Intelligent Systems 2024, 2024, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M. B. The paradox of artificial creativity: Challenges and opportunities of generative AI artistry. Creativity Research Journal 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbya, H.; Strich, F.; Tamm, T. Navigating generative artificial intelligence promises and perils for knowledge and creative work. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 2024, 25, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J. M. Using generative AI to produce images for nursing education. Nurse educator 2023, 48, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Suh, S. AI technology integrated education model for empowering fashion design ideation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Z. Aesthetic education in the new media era: From the perspective of aesthetic education philosophy. European Journal for Philosophy of Religion 2023, 15, 316–330. [Google Scholar]

- Paananen, V.; Oppenlaender, J.; Visuri, A. Using text-to-image generation for architectural design ideation. International Journal of Architectural Computing 2024, 22, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, T.; Badreldin, H. A.; Alrashed, M.; Alshaya, A. I.; Alghamdi, S. S.; Bin Saleh, K.; Alowais, S. A.; Alshaya, O. A.; Rahman, I.; Al Yami, M. S. The emergent role of artificial intelligence, natural learning processing, and large language models in higher education and research. Research in social and administrative pharmacy 2023, 19, 1236–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Seokin, K.; Zhang, L. In On GANs art in context of artificial intelligence art, Proceedings of the 2021 5th International Conference on Machine Learning and Soft Computing, 2021; pp 168-171.

- Anantrasirichai, N.; Zhang, F.; Bull, D. Artificial Intelligence in Creative Industries: Advances Prior to 2025. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Huang, Y. Technological innovation in architectural design education: Empirical analysis and future directions of midjourney intelligent drawing software. Buildings 2024, 14, 3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Ye, H.; Chen, S.-Y.; Gao, L.; Fu, H. DrawingInStyles: Portrait image generation and editing with spatially conditioned StyleGAN. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 2022, 29, 4074–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Song, W.; Lin, G.; Shi, Y. Solar Image Cloud Removal based on Improved Pix2Pix Network. Computers, Materials & Continua 2022, 73, 6181–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. Application of AI-assisted painting creation based on AIGC background. Communications in Humanities Research 2024, 35, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T. The Application of AI Art in New Media Art Design. Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences 2024, 41, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmawan, A. J.; Arimbawa, I. M. G.; Heptariza, A.; Brayen, H. In Harnessing Ai Image generator prompt engineering For academic excellence, Proceeding Bali-Bhuwana Waskita: Global Art Creativity Conference, 2024; pp 192-202.

- Mökander, J.; Schroeder, R. AI and social theory. AI & SOCIETY 2021, 37, 1337–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, H.; Yoo, C.; Pan, Y. Is everyone an artist? A study on user experience of AI-based painting system. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fu, T.; Du, Y.; Gao, W.; Huang, K.; Liu, Z.; Chandak, P.; Liu, S.; Van Katwyk, P.; Deac, A.; Anandkumar, A.; Bergen, K. J.; Gomes, C. P.; Ho, S.; Kohli, P.; Lasenby, J.; Leskovec, J.; Liu, T.-Y.; Manrai, A. K.; Marks, D. S.; Ramsundar, B.; Song, L.; Sun, J.; Tang, J.; Velickovic, P.; Welling, M.; Zhang, L.; Coley, C. W.; Bengio, Y.; Zitnik, M. Scientific discovery in the age of artificial intelligence. Nature 2023, 620, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q. Application of artificial intelligence-based visual arts pedagogy in traditional painting education. Applied Mathematics and Nonlinear Sciences 2024, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.-C.; Hwang, G.-J.; Hsia, L.-H.; Shyu, F.-M. Artificial intelligence-supported art education: A deep learning-based system for promoting university students’ artwork appreciation and painting outcomes. Interactive Learning Environments 2024, 32, 824–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Mokmin, N. A. M. Unveiling the canvas: Sustainable integration of AI in visual art education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragot, M.; Martin, N.; Cojean, S. AI-generated vs. human artworks. A perception bias towards artificial intelligence? In In Extended abstracts of the 2020 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 1–10). 2020.

- Hsu, C.-C.; Lee, C.-Y.; Zhuang, Y.-X. Learning to detect fake face images in the wild. In 2018 international symposium on computer, consumer and control (IS3C) (pp. 388–391), 2018; pp 388-391.

- Risse, M. Political theory of the digital age: Where artificial intelligence might take us. Cambridge University Press: 2023.

- Hutson, J.; Nichols, M. H. Generative AI and algorithmic art: Disrupting the framing of meaning and rethinking the subject-object dilemma. Global Journal of Computer Science and Technology 2023, 23, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y. Ethical risk and pathway of AIGC cross-modal content generation technology. International Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities (IJSSH) 2024, 9, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoie, A. Aesthetic experience and creativity in arts education: Ehrenzweig and the primal syncretistic perception of the child. Cambridge Journal of Education 2017, 47, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. Mis Quarterly 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D.; Granić, A. Introduction:“Once Upon a TAM”. In The Technology Acceptance Model Springer: 2024; pp 1-18.

- Kavitha, K.; Joshith, V. P. Artificial intelligence powered pedagogy: Unveiling higher educators acceptance with extended TAM. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, D. Integrating TAM and IS success model: Exploring the role of blockchain and AI in predicting learner engagement and performance in e-learning. Frontiers in Computer Science 2023, 5, 1227749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Xu, N. Extended TAM model to explore the factors that affect intention to use AI robotic architects for architectural design. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 2022, 34, 349–362. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, S.; Kaye, S.-A.; Oviedo-Trespalacios, O. What factors contribute to the acceptance of artificial intelligence? A systematic review. Telematics and Informatics 2023, 77, 101925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. S. M.; Wasel, K. Z. A.; Abdelhamid, A. M. M. Generative AI and media content creation: Investigating the factors shaping user acceptance in the Arab Gulf States. Journalism and Media 2024, 5, 1624–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhuri, R.; Vrontis, D.; Thrassou, A.; Ghosh, S. K. Adoption of artificial intelligence-integrated CRM systems in agile organizations in India. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2021, 168, 120783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Tu, Y.-F. Factors affecting the adoption of AI based applications in higher education: An analysis of teachers perspectives using structural equation modeling. Educational Technology and Society 2021, 24, 116–129. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Li, T.; Gao, C. Why do designers in various fields have different attitude and behavioral intention towards AI painting tools? an extended UTAUT model. Procedia Computer Science 2023, 221, 1519–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Xie, H.; Yu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zuo, W.; Zeng, W. Exploring user acceptance of Al image generator: Unveiling influential factors in embracing an artistic AIGC software. AI-generated Content 2024, 1946, 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Hansen, P.; Zhu, Q. Exploring laypeople’s engagement with AI painting: A preliminary investigation into human-AI collaboration. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology 2023, 60, 1215–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe, Y.; Gutierrez, O.; Huanca, S.; Castillo, W.; Quilcca, G. Motivational, cognitive and emotional factors as predictors of creative expression in university students. Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental 2024, 18, e010563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Ouyang, F. The application of AI technologies in STEM education: a systematic review from 2011 to 2021. International Journal of STEM Education 2022, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, G.; Yeşilyurt, Y. E. A bibliometric analysis of artificial intelligence in L2 teaching and applied linguistics between 1995 and 2022. ReCALL 2024, 36, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Han, B.; Ryu, S.; Hua, M. Acceptance of generative AI in the creative industry: Examining the role of AI anxiety in the UTAUT2 model. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 288–310). Springer Nature Switzerland: 2023.

- Li, W. A study on factors influencing designers’ behavioral intention in using AI-generated content for assisted design: perceived anxiety,perceived risk, and UTAUT. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2024, 1-14.

- Zhang, C.; Lei, K.; Jia, J.; Ma, Y.; Hu, Z. AI painting: An aesthetic painting generation system. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM international conference on Multimedia (pp. 1231–1233). 2018.

- Fan, Y. The promotion strategy of artificial intelligence on students ‘ creativity and critical thinking in college art education. International Theory and Practice in Humanities and Social Sciences 2024, 1, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W. R.; He, J. A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model. Information & Management 2006, 43, 740–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Sánchez, J.-P.; Villarejo-Ramos, Á. F.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Shaikh, A. A. Identifying relevant segments of AI applications adopters - Expanding the UTAUT2’s variables. Telematics and Informatics 2021, 58, 101529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W. Innovative school climate, teacher’s self-efficacy and implementation of cognitive activation strategies. Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction 2023, 13, 126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kokil, U.; Harwood, T. The interplay between perceived usability and quality in visual design for tablet game interfaces. Journal of User Experience 2022, 17, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, T. H.; Kim, M. Is ChatGPT scary good? How user motivations affect creepiness and trust in generative artificial intelligence. Telematics and informatics 2023, 83, 102030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J. Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Scheepers, H. Understanding the intrinsic motivations of user acceptance of hedonic information systems: Towards a unified research model. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 2012, 30, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, S. C.; Trudel, R.; Kurt, D. The influence of purchase motivation on perceived preference uniqueness and assortment size choice. Journal of Consumer Research 2018, 45, 710–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N. P.; Prakasam, N.; Dwivedi, Y. K. The battle of Brain vs. Heart: A literature review and meta-analysis of “hedonic motivation” use in UTAUT2. International Journal of Information Management 2019, 46, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, N.; Upadhyay, S.; Dwivedi, Y. K. Theorizing artificial intelligence acceptance and digital entrepreneurship model. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 2022, 28, 1138–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. Y.; Sheehan, L.; Lee, K.; Chang, Y. The continuation and recommendation intention of artificial intelligence-based voice assistant systems (AIVAS): The influence of personal traits. Internet Research 2021, 31, 1899–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.-Y.; Jhang, C.-C.; Wang, Y.-S. Factors affecting parental intention to use AI-based social robots for children’s ESL learning. Education and Information Technologies 2024, 29, 6059–6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, P. B.; Gaskin, J.; Twyman, N.; Hammer, B.; Roberts, T. Taking ‘fun and games’ seriously: Proposing the hedonic-motivation system adoption model (HMSAM). Journal of the association for information systems 2012, 14, 617–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational psychologist 1993, 28, 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Yang, L.; Ergün, A. L. P. Exploring the relationship between burnout, learning engagement and academic self-efficacy among EFL learners: A structural equation modeling analysis. Acta Psychologica 2024, 248, 104394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M.; Usher, E. L. Self-efficacy in educational settings: Recent research and emerging directions. Advances in Motivation and Achievement 2010, 16, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch, R. A.; Case, K. A.; Meerman, H. Increasing academic self-efficacy in statistics with a live vicarious experience presentation. Teaching of Psychology 2012, 39, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latikka, R.; Turja, T.; Oksanen, A. Self-efficacy and acceptance of robots. Computers in Human Behavior 2019, 93, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, Y. Y.; Hwang, Y. Predicting the use of web-based information systems: Self-efficacy, enjoyment, learning goal orientation, and the technology acceptance model. International journal of human-computer studies 2003, 59, 431–449. [Google Scholar]

- Surendran, P. Technology acceptance model: A survey of literature. International journal of business and social research 2012, 2, 175–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C.; Marks Woolfson, L.; Durkin, K. School environment and mastery experience as predictors of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs towards inclusive teaching. International journal of inclusive education 2020, 24, 218–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J. The effect of computer self-efficacy on the behavioral intention to use translation technologies among college students: Mediating role of learning motivation and cognitive engagement. Acta Psychologica 2024, 246, 104259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, K. P.; Pramod, D. Conversational artificial intelligence in the workplace: Analysing the impact of ChatGPT on users’perceived self-efficacy. In 2024 2nd International Conference on Advancement in Computation & Computer Technologies (InCACCT) (pp. 766–770). 2024; pp 766-770.

- Kwak, Y.; Ahn, J.-W.; Seo, Y. Influence of AI ethics awareness, attitude, anxiety, and self-efficacy on nursing students’ behavioral intentions. BMC Nursing 2022, 21, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Nah, S.; Makady, H.; McNealy, J. Understanding user attitudes towards AI-enabled technologies: An integrated model of self-efficacy, TAM, and AI ethics. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2024, 1-13.

- Holden, H.; Rada, R. Understanding the influence of perceived usability and technology self-efficacy on teachers’ technology acceptance. Journal of research on technology in education 2011, 43, 343–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, M.; Elgammal, A. Art, creativity, and the potential of artificial intelligence. Arts 2019, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. C.; Chen, T. Aesthetic visual auality assessment of paintings. IEEE Journal of selected topics in Signal Processing 2009, 3, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conklin, S. M.; Koubek, R. J.; Thurman, J. A.; Newman, L. The effects of aesthetics and cognitive, style on perceived usability. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting 2006, 50, 2153–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soui, M.; Chouchane, M.; Mkaouer, M. W.; Kessentini, M.; Ghédira, K. Assessing the quality of mobile graphical user interfaces using multi-objective optimization. Soft Computing 2019, 24, 7685–7714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lu, H. Comparing the design quality and efficiency between design intelligence and intermediate designers. In 2022 14th International Conference on Intelligent Human-Machine Systems and Cybernetics (IHMSC) (pp. 184–187). IEEE: 2022; pp 184-187.

- Zou, X. The development and impact of AI-generated content in contemporary painting. Transactions on Computer Science and Intelligent Systems Research 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpokas, I. Work of art in the age of its AI reproduction. Philosophy & Social Criticism 2023.

- Johnson, D. G.; Verdicchio, M. AI anxiety. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 2017, 68, 2267–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-Y.; Wang, Y.-S. Development and validation of an artificial intelligence anxiety scale: An initial application in predicting motivated learning behavior. Interactive Learning Environments 2019, 30, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, F.; Aydın, F.; Schepman, A.; Rodway, P.; Yetişensoy, O.; Demir Kaya, M. The roles of personality traits, AI anxiety, and demographic factors in attitudes toward artificial intelligence. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 2022, 40, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, J.; Miller, J. L. The positive role of negative emotions: Fear, anxiety, conflict and resistance as productive experiences in academic study and in the emergence of learner autonomy. The International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education 2009, 20, 144–154. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Yang, X.; Li, D.; Liu, Y. An explanatory study of factors influencing engagement in AI education at the K-12 Level: An extension of the classic TAM model. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 13922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florin Stănescu, D.; Constantin Romașcanu, M. The influence of AI anxiety and neuroticism in attitudes toward artificial intelligence. European Journal of Sustainable Development 2024, 13, 191–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. T.; Pan, Y. H.; Yan, M.; Su, Z.; Luan, T. H. A survey on ChatGPT: AI-generated contents, challenges, and solutions. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society 2023, 4, 280–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]