1. Introduction

Public–Private Partnerships (PPPs) have emerged as a vital delivery model for infrastructure and public service projects over the past four decades. This model aims to create social value by aligning public service delivery objectives with private sector incentives [

1]. It exhibits cross-sectoral and cross-industry applicability [

2], with applications spanning healthcare, affordable housing, etc.

PPP projects prioritise sustainability as a key objective, the achievement of which relies on sustainable processes [

3]. When properly structured and implemented, they can help bridge infrastructure and public service gaps while improving service quality. Existing research has extensively explored sustainability in PPPs [

4]. Sustainable practices throughout the project lifecycle have also been examined [

5,

6].

However, compared to traditional procurement projects, PPP projects are more complex, requiring clearly defined project outputs, reasonable allocation of roles and responsibilities, proper risk distribution, and better integration of expertise and resources [

7]. This poses challenges to project sustainability. Evidence shows that PPP projects worldwide face sustainability issues [

8].

Furthermore, the relationship between PPPs and sustainability should be examined through three key dimensions: economic, environmental, and social, which constitute the three pillars of sustainability. Social sustainability in projects is crucial, as it entails the well-being of stakeholders and improvements in quality of life [

9]. Integrating social sustainability considerations throughout the project lifecycle enhances long-term benefits, whereas neglecting them can lead to risks [

10]. Yet, the social sustainability of PPPs has not received sufficient attention [

11].

This neglect could be detrimental to PPP projects, as social sustainability holds particular significance for them. The profit-driven nature of the private sector may undermine the social value that PPPs aim to create [

12]. Unfortunately, such concerns are being validated. Study [

13] found that the private sector’s pursuit of long-term financial returns may harm end-user interests. Study [

14] demonstrated how private sector profit motives can compromise the public interests. The optimal approach to achieving social sustainability lies in carefully considering and planning activities throughout the project lifecycle [

15]. However, existing research has paid insufficient attention to different stakeholders. There is an urgent need to identify the specific actions each stakeholder should take [

16] and to explore context-specific, process-oriented systemic pathways for integrating social sustainability [

17].

Therefore, the key research question of this study is: How do PPP projects achieve social sustainability? The research aims to explore the structuring of PPP projects to effectively achieve social sustainability. Grounded in prescriptive theorising, it adopts a single-case study approach supplemented by content analysis and backcasting method to examine a Chinese aged care PPP project. Aged care PPP projects refer to long-term contracts between the public and private sectors, where the latter is responsible for providing centralised accommodation, support, and caring services for the elderly at designated locations. The Chinese government has publicly supported PPPs in aged care since 2015. By mid-2022, approximately 100 such projects were recorded in the Ministry of Finance’s project management database.

This research contributes to the field of healthy aging and built environment by examining PPPs in the delivery of aged care services, with a primary focus on social sustainability. Through an in-depth analysis of the case project, it provides valuable insights into how PPPs can be leveraged to provide care services, highlights the importance of social sustainability for PPP projects, and explores PPPs’ potential to achieve it. Additionally, the study expands the application of prescriptive theorising and backcasting, establishing their relevance in the context of PPPs and social sustainability. A structured approach is introduced, synthesising prescriptive theorising with backcasting to analyse and realise social sustainability in aged care PPP projects.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Achieving Sustainability of PPP Projects

Few studies have specifically addressed the social sustainability of PPP projects. Consequently, it is necessary to adopt a broader perspective—that of comprehensive sustainability—to understand this matter. The sustainability of PPPs emphasises sustainable practices throughout the entire project lifecycle to minimise environmental and social impacts [

18]. Study [

19] argues that the public sector should clearly define sustainability objectives during project conceptualisation.

PPP projects that prioritise sustainability emphasise collaborative governance between public and private sectors. To this end, both formal and informal governance tools can be employed to resolve institutional conflicts, integrate project resources, and establish coordination mechanisms [

20]. Contractual governance serves as the primary formal governance instrument [

21]. The public sector can adopt practices such as selecting sustainable private partners [

22], and designing projects rationally [

5]. Additionally, the public sector should leverage informal governance to advance project sustainability [

6].

2.2. PPP Projects in Aged Care Sector

Population aging drives rapid growth in demand for aged care services, including both home-based assistance and institutional care that encompasses daily living support, personal care, healthcare services, and accommodation [

23]. Governments face growing challenges in delivering these public services [

24]. In this context, some countries have begun experimenting with PPPs in this sector.

Existing research on aged care PPPs has primarily focused on Australian and Chinese contexts. In Australia, PPPs have been applied to the development and operation of retirement villages. Study [

25] highlighted best practices for the sustainable development of retirement village PPPs, including the age-friendly design, appropriate location, etc. Five risk factors were found to significantly impact the development of the projects [

26]. Study [

27] further identified “affordability,” “reduced social isolation of residents,” and “improvement of emotional well-being of residents” as the three most critical success criteria for the projects.

Research on PPPs in China’s aged care sector is more fragmented. Study [

28] examined three models of aged care PPPs in Guangdong Province. (Anonymised for Review #1) identified critical practices that should be adopted and established a socially sustainable development process to achieve the social sustainability of such projects. Study [

29] developed a post-occupancy evaluation model for community aged care PPP projects.

2.3. Social Sustainability of Aged Care Projects

Social sustainability in aged care projects refers to the comprehensive consideration of social impacts on stakeholders throughout the entire project lifecycle and the realisation of their well-being (Anonymised for Review #2). Mirroring the research landscape on PPP social sustainability, global studies specifically focusing on social sustainability in aged care projects remain scarce. In China, Study [

30] discovered that most issues identified within residential aged care environments related directly to social sustainability. Further, (Anonymised for Review #2) developed a social sustainability indicator framework for aged care projects, revealing that the current status of social sustainability achievement is suboptimal in China. Building on this, (Anonymised for Review #1) proposed a socially sustainable development process to enhance the social sustainability of aged care PPP projects. Study [

31] identified specific social sustainability characteristics of China's Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRCs).

In Australia, a study reached conclusions similar to those in China, indicating that social sustainability of the aged care system is lacking [

32]. Additionally, scholars have examined the social sustainability of Australian retirement villages, finding it valued by both developers and residents [

33]. Developers are encouraged to provide facilities to enhance resident interaction and improve social sustainability [

34]. Another study conducted in Slovenia assessed the impact of nursing home architecture and open spaces on social sustainability. The findings indicated that, following the COVID-19 pandemic, private investors prioritised economic efficiency over concerns for the quality of life of older adults [

35].

2.4. Research Gap

The literature review offers two key insights: a) PPPs represent a viable model for delivering aged care services; and b) social sustainability is critical to PPPs. However, neither PPPs in the aged care sector nor the social sustainability of PPPs have received adequate attention. A comprehensive understanding of how aged care PPPs operate is lacking. Specifically, the implementation of such projects in specific contexts remains unclear [

36]. Research on how aged care PPPs address multifaceted social sustainability challenges is limited, with few exceptions like (Anonymised for Review #1).

This study aims to address this research gap. Before presenting the research design, it is necessary to briefly introduce two foundational studies. First, a social sustainability indicator framework for aged care projects in China has been developed (Anonymised for Review #2). This framework considers ten social impacts across three categories of stakeholders, encompassing twenty-one indicators (see

Table 1 for details), illustrating what constitutes a socially sustainable project. Another study explored how to achieve social sustainability in these projects by identifying a series of critical practices (CPs) to be adopted by government departments, private investors, and Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), and by establishing twenty-one realisation paths (Anonymised for Review #1). This study seeks to integrate the indicator framework and realisation paths, examining their application in aged care PPPs to achieve stakeholder well-being.

3. Methodology

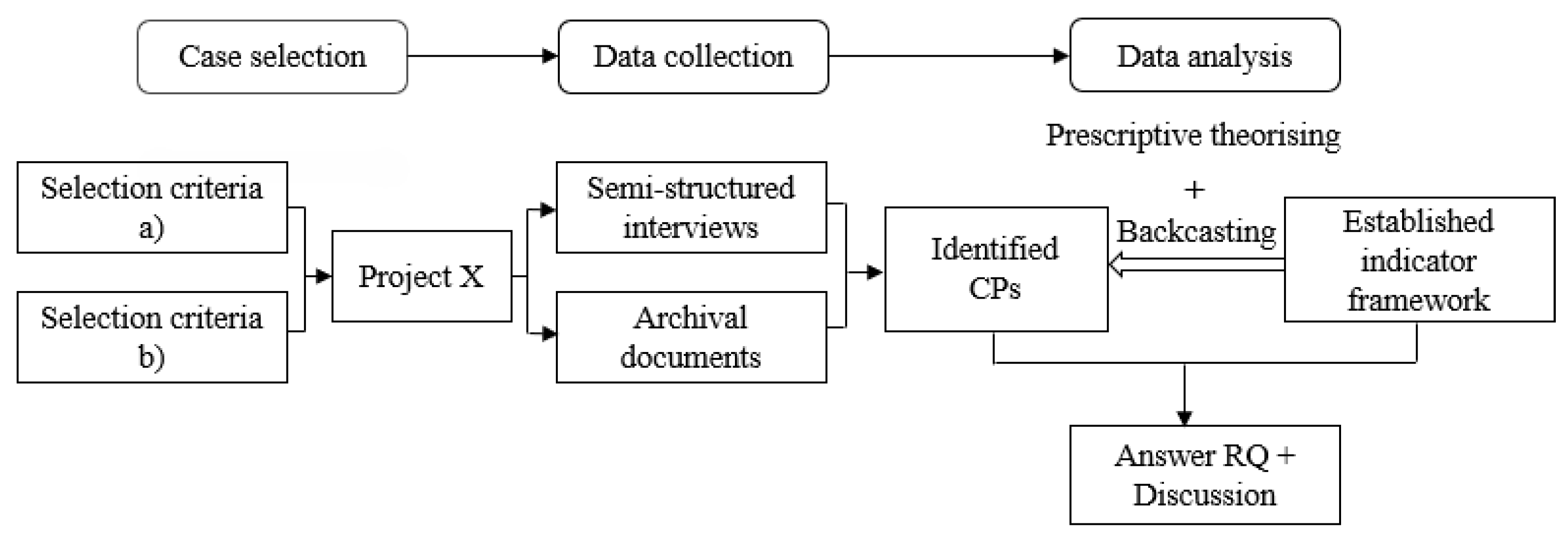

This study employs prescriptive theorising to analyse the achievement of social sustainability in aged care PPP projects. Prescriptive theorising constitutes normative arguments regarding how things should be and how to achieve desired outputs [

37]. The social sustainability of PPP projects requires not only clear articulation of ideal outputs but also roadmaps for achieving them. An exploratory single case study was conducted to analyse how the public and private sectors progressively adopted CPs across different lifecycle phases of an aged care PPP project to achieve social sustainability and to derive insights. Guided by prescriptive theorising, this study pre-establishes social sustainability goals and uses them as a guide to analyse how projects achieve success.

3.1. Case Selection

Project X, an aged care PPP project in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, China, was selected based on two criteria: a) it has entered the operational phase and is recognised by practitioners as successful; and b) it has no negative press coverage. Considering that practitioners are not familiar with the concept of social sustainability, “success” is used as a substitute. Project X was recommended by experienced practitioners in the aged care PPP sector known to the authors.

The implementing agency for Project X is the Civil Affairs Bureau of District A in Shenzhen. In June 2019, the Bureau issued a competitive tender notice for a PPP project involving the District A Welfare Centre (a publicly built and operated aged care institution). Company B won the tender, and a contract was signed in July 2019. The project has a total capacity of 791 beds, a concession period of 15 years, and a user-pays payment mechanism. It is intended to provide universal and affordable aged care services. Company B is required to ensure that it provides affordable, convenient, and accessible services to residents with household registration in District A, particularly for elderly individuals identified as the 'Three No's' (those with no children or relatives, little or no income, and no ability to work), recipients of the minimum living allowance, and other specific groups such as veterans and the very elderly. These groups receive financial support from the local government and pay fees below market prices, with 400 government-subsidised beds designated for this purpose. The remaining 391 beds are allocated market-rate services to elderly people not registered in District A.

Project X serves as a "critical case". It represents Shenzhen's first standardised implementation of an aged care PPP project, setting a benchmark for socialised aged care services across the city. The District A Welfare Centre, established in 2015, had already accumulated rich operational experience over four years prior to the introduction of the PPP model. Having undergone a long period of operation is one of the key reasons why Project X was selected.

3.2. Data Collection

Data collection was conducted through semi-structured interviews and project archive documents. Senior management personnel from Project X's consulting agency and SPV were selected for in-depth interviews, representing the public and private sectors of the project. Three criteria guided the selection of interviewees: a) direct involvement in Project X, b) holding a senior position in the project with sufficient knowledge of the project, and c) an understanding of social sustainability. Three respondents were identified. Their demographic information is shown in

Table 2.

After identifying the interviewees, the authors first collected archival documents of Project X, to familiarise themselves with the project and develop an interview protocol. The protocol was semi-structured and uesed to identify CPs. CPs refer to behaviors or decisions made by the public sector, private investors, and the SPV involved in Project X that have significant direct or indirect impacts on social sustainability in the short or long term.

The interviews were conducted in July 2021. With interviewees’ consent, all interviews were recorded and later transcribed. Interviewees R1 and R2 were each re-interviewed by phone in October 2021 to supplement the data.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted in two stages.

First, content analysis was employed to identify CPs. Only practices that had already been adopted in Project X were considered. Each interview and each document were treated as an analysis unit. The coding principle centred on whether a behaviour or decision was deemed critical - specifically, whether it had a clear purpose or intention, and demonstrated explicit consequences or impacts [

38]. Furthermore, the identified CPs were grouped according to their timing and implementers. Finally, the CPs were validated to ensure reliability.

Second, the backcasting method was used to analyse how the identified CPs were implemented step by step to achieve social sustainability. Backcasting entails first defining a successful end state and then working backwards to plan specific actions from the present to reach that goal. This approach helps avoid sub-optimisation by starting from a strong definition of the desired outputs [

39]. It aligns closely with the prescriptive theorising process. In this study, the established social sustainability indicator framework for aged care projects was set as the goal. The identified CPs were then linked to the various indicators according to their implementation order.

Figure 1 illustrates the process of this study.

4. Results

The results of the content analysis showed that thirty-three CPs were adopted in Project X. Since the detailed identification process of CPs has already been presented in (Anonymised for Review #1), it will not be elaborated upon here. These thirty-three CPs are listed in

Appendix A. This section primarily demonstrates the process of structuring Project X to achieve social sustainability using the Backcasting method.

Two clarifications are necessary before presenting the results:

A) Project X was taken over by the SPV in August 2019. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the project had minimal social impacts on the local community and broader society. Hence, the Backcasting analysis focuses only on the fourteen indicators related to the first two stakeholder groups.

B) For brevity, indicators associated with the same social impact were backcasted together.

4.1. To Achieve Employee Well-Being

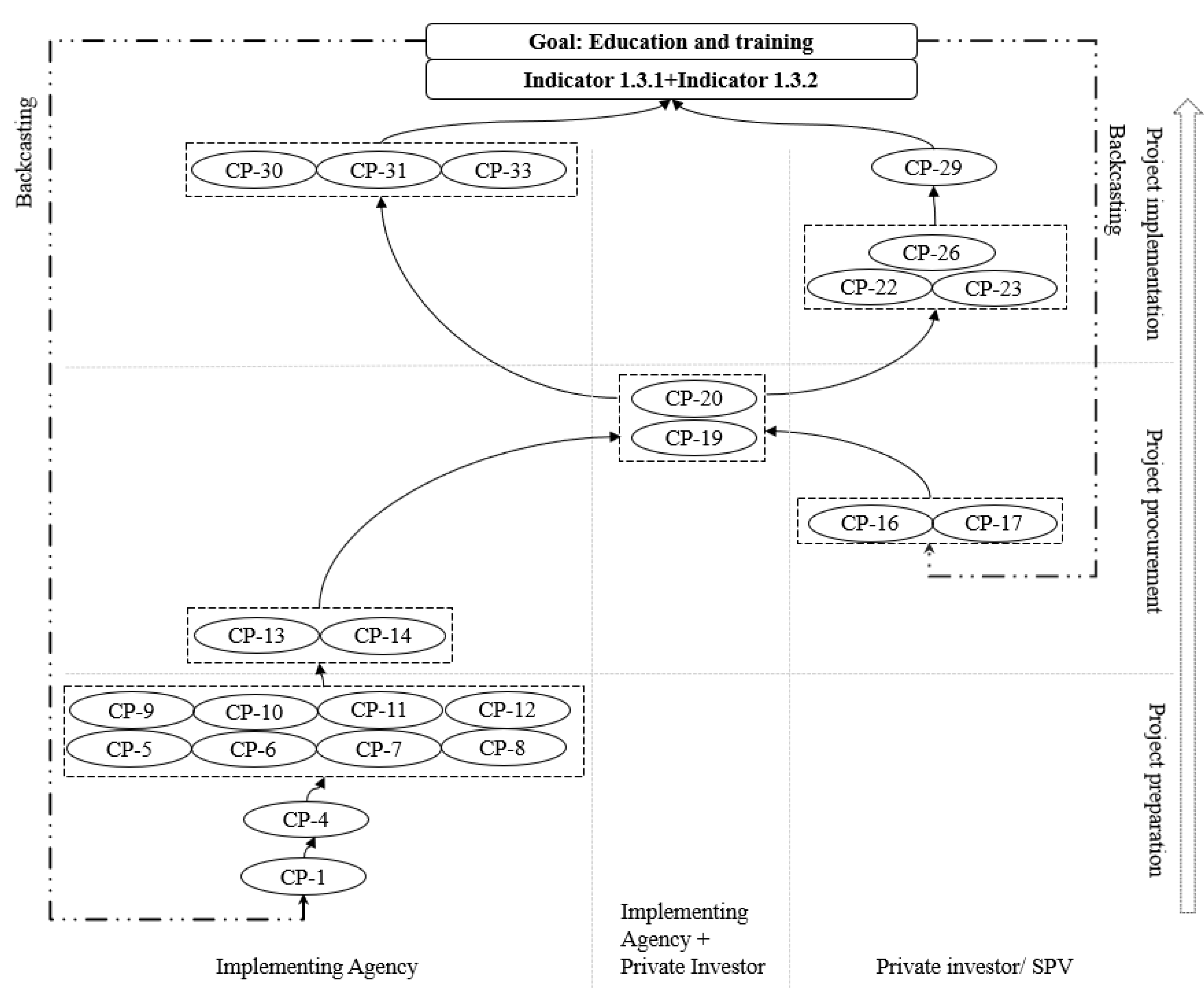

Education and training represent one of the impacts of aged care PPP projects on employee well-being, encompassing the two most important indicators, namely mastering professional skills (Indicator 1.3.1) and improving sustainability awareness (Indicator 1.3.2) (Anonymised for Review #2). This subsection uses the realisation of these two indicators as examples to illustrate the analysis results obtained through the Backcasting method.

During the project preparation phase, the public sector undertook a series of behaviours and decisions. First, the Civil Affairs Bureau of District A incorporated employee education and training into the feasibility study (CP-1). Second, the implementing agency selected a consultant conducive to achieving social sustainability (CP-4). Then, the implementing agency assisted the consultant in conducting industry research (CP-5), introduced stakeholder engagement (CP-6), and provided references for formulating a business case that emphasises employee education and training. "We took employee representatives to visit projects that had already adopted the PPP model, so they could see that after the reform, there would be better training opportunities and room for professional development." (R1)

In the subsequent business case development, the implementing agency undertook the following CPs: a) developed output specifications (CP-7). "We put forward requirements for employee training, mainly considering whether employees' skills could meet the needs." (R1); b) identified risks and established response plans (CP-8); c) defined primary revenue sources and developed an initial payment mechanism (CP-9). During the operation period, the implementing agency performs annual and interim assessments of the SPV. Failure to provide education and training as required would affect payments; d) included education and training provisions in the intial contract arrangements (CP-10), established a preliminary monitor framework to ensure the SPV is on the right track (CP-11), and developed a procurement strategy to secure the most goal-aligned partner (CP-12).

In the procurement phase, the implementing agency decided to adopt a comprehensive scoring method to select partners (CP-13) and included specific terms in the draft contract (CP-14). Performance assessment indicators and the quality management system incorporated employee education and training aspects. Subsequently, the private investor conducted a detailed market investigation (CP-16) to understand training practices in other aged care institutions. A person-centred operation plan was established (CP-17), including human resource management strategies aligned with employees' core social needs. The implementing agency then selected partners (CP-19) and signed contracts that aligned with the project goals (CP-20).

During the project implementation phase, the SPV drafted the Quality Management System documents (CP-22). The annual operational plan included strategies for employee training. Stakeholder engagement was integral (CP-23), addressing education and training in communications with both the public sector and employees. Most importantly, the SPV provided education and training to employees (CP-26). New employees participated in induction training, while existing employees received ongoing training covering basic caring skills and various specialised training programmes. Meanwhile, various skill competitions and employee star-level certification programmes were also held within the project. "We prioritise employee training. We have achieved first place in the Shenzhen Aged Caregivers Vocational Skills Competition for two consecutive years. We have also established a comprehensive training system for medical and nursing staff." (R3) Finally, the SPV monitored its own outputs (CP-29). Meanwhile, government departments also supervised the project (CP-30) and conducted performance evaluations (CP-31), adjusting payments based on the evaluation results (CP-33), thus ensuring that the SPV meets its contractual obligations.

Figure 2 shows the backcasting process of Indicators 1.3.1 and 1.3.2.

For brevity, the realisation of indicators related to employee equity and fairness, as well as health and safety, are shown in

Figure S1 and

Figure S2.

4.2. To Achieve Elderly and Their Relatives Well-Being

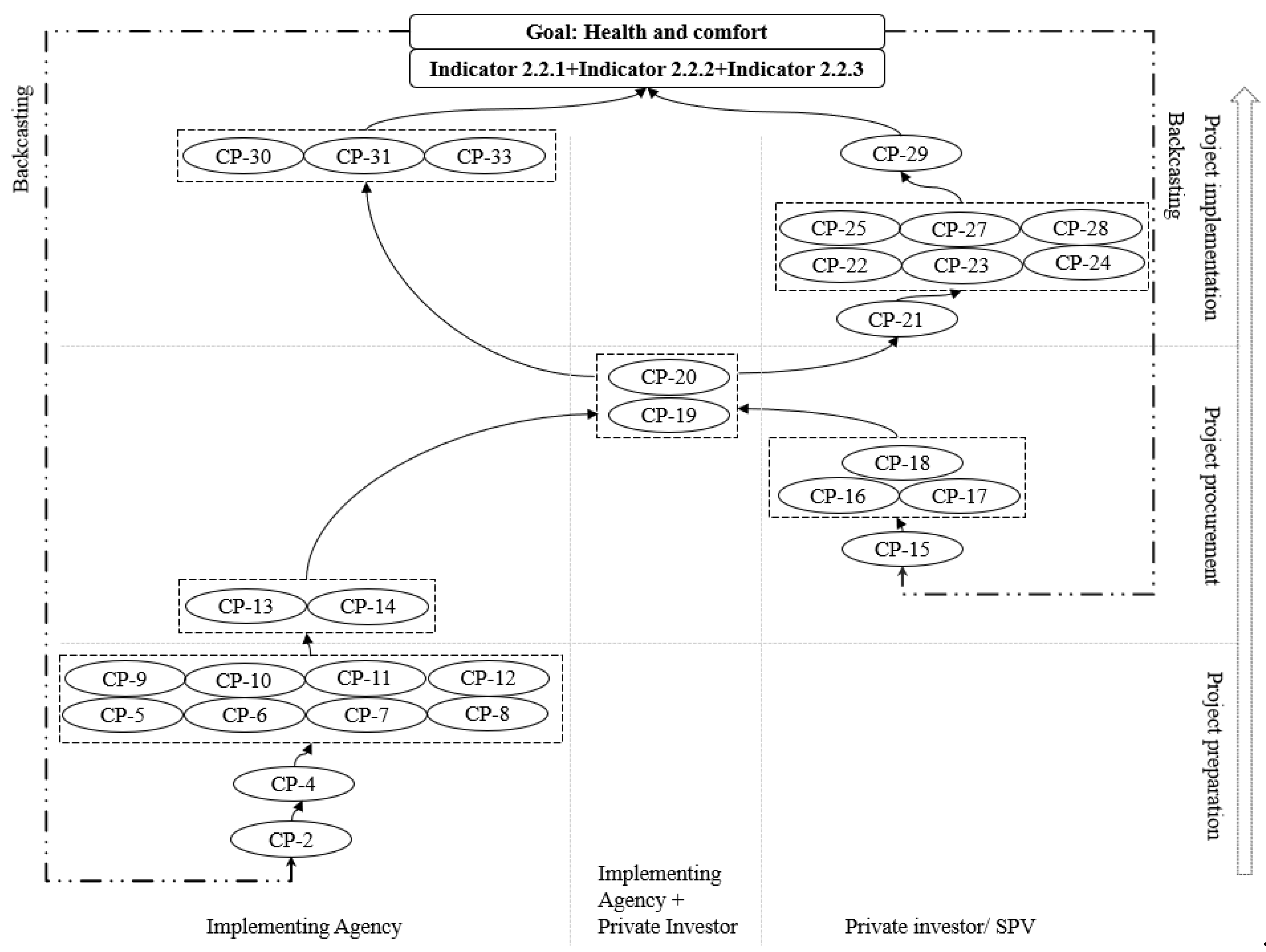

Health and comfort is one of the impacts of projects on the wellbeing of the elderly and their relatives, encompassing the three most important indicators - satisfied basic needs (Indicator 2.2.1), satisfied health and physical comfort (Indicator 2.2.2), and satisfied psychological comfort (Indicator 2.2.3). The result of Backcasting analysis is shown in

Figure 3.

Many CPs were adopted in the preparation phase. First, during the feasibility study, the implementing agency initially considered the health and comfort of the elderly (CP-2). Second, the implementing agency selected an appropriate consultant to assist in achieving the goals (CP-4). "The three competitors were equally matched in capability, but not all of them paid sufficient attention to aged care matters. We performed better in this regard." (R1) The implementing agency then assisted the consultant in conducting an industry investigation (CP-5) and engaging stakeholders (CP-6) to inform the development of a business case focusing on the health and comfort of older people. "We investigated the institutions in our city to determine the project's outputs, such as the ratio of caregivers to elderly residents, and what services should be provided." (R1)

In the subsequent development of the business case, the implementing agency adopted the following CPs:

a) established output specifications (CP-7). It required the SPV to provide a range of services to meet the needs of all elderly people, regardless of their physical abilities, residency status, financial support, or economic situation. "The fees for government-subsidised beds are much lower than those for market-rate beds. To meet the needs of policy-supported elderly, we calculated their number …The services include care, meals, security, etc. The first two are core services that the SPV is not allowed to subcontract…Elderly people and their families are very concerned about the quality of food, so we set a minimum standard for the SPV's procurement budget for food ingredients at 800 RMB per month per bed." (R1);

b) identified risks and developed response plans (CP-8), allocating design and operational risks related to service quality to the SPV;

c) determined the main source of profit—the basic aged care service fees—and established the initial payment mechanism (CP-9). Basic aged care service fees refer to bed fees and caring fees. "We require the SPV to determine the prices before the elderly move in to prevent any reduction in service quality or pressure on residents to purchase additional services. " (R1);

d) included initial contractual provisions related to the health and comfort of the elderly (CP-10), established a preliminary monitor framework to ensure the SPV stays on the right track (CP-11), and formulated a procurement strategy to secure partners with aligned goals (CP-12). For example, Project X's business case requires the SPV to provide operation and maintenance performance bonds, establish contingency plans, and strictly control changes in equity ownership. Competitive consultation was selected for project procurement.

In the project procurement phase, the public and private sectors adopted the following CPs. First, the implementing agency set evaluation criteria for private investors, giving higher scores to those with experience in similar projects (CP-13), and refined contract terms to prioritise the health and comfort of residents (CP-14). For example, in the performance evaluation plan, assessments of aged care services provided by the SPV accounted for 60% of the total score.

Second, the private investor adopted several CPs, including prioritising social benefits over profit (CP-15), investigating the social needs of the elderly (CP-16), and establishing a person-centred operational and maintenance plan (CP-17 and CP-18). " We undertook this project to explore new service areas. We wanted to establish a good reputation and provide high-quality services." (R2) Finally, the implementing agency selected an appropriate partner (CP-19) and signed the contract (CP-20).

During the implementation phase, the SPV adopted additional CPs, including: a) defining a vision to build a multi-level aged care service supply system and enhance the quality of services (CP-21); b) drafting quality management system documents (CP-22), and setting up complaint management and satisfaction survey systems. "Residents can lodge complaints within the institution, or externally to the Civil Affairs Bureau, government complaint platforms (12345), or media channels." (R2); c) engaging stakeholders to better understand their social needs and perspectives to improve services (CP-23). Project X established multiple channels (such as short video broadcasts and elderly assemblies) for information interaction with the elderly. The SPV and the implementing agency also created a joint meeting system; d) assuming project operations as contracted (CP-24); e) providing diverse services as agreed (CP-25); f) enacting emergency response measures (CP-27); g) performing facility maintenance as agreed (CP-28); h) delivering self-monitored outputs (CP-29).

At this stage, the implementing agency and other government departments adopted three CPs: a) monitored contract implementation (CP-30). "The District Finance Bureau is evaluating the project, mainly monitoring whether the SPV is fulfilling its contractual obligations." (R3); b) conducted performance evaluations (CP-31); c) made payments based on performance results (CP-33).

Figure S3 and

Figure S4 respectively demonstrate the backcasting realisation of indicators related to equity and accessibility for the elderly and their relatives.

5. Discussions

5.1. Importance of Social Sustainability for PPP Projects

The case study demonstrates that social sustainability is crucial when utilising PPP projects to provide aged care services. Achieving social sustainability means meeting the social needs of the elderly, their relatives, and employees, ensuring a high quality of life. This is essential for the sustainable development of an aging society [

32].According to [

3], projects are not only expected to produce sustainable outputs but are also required to adopt socially sustainable processes.

First, aged care PPPs should deliver socially sustainable services. The inherent profitability of private investors in PPPs may lead to their lack of genuine focus on satisfying the social needs of service recipients [

14]. Project X's public and private sectors identified the social needs of the elderly and translated them into services through a series of practices (CP-2, CP-5 to CP-7, CP-16, CP-17, and CP-23). These practices are supported by prior research. Both government agencies and private investors need to clearly define their requirements at the outset of the project and a lack of clear output specification will cause losses in the future [

40]. The introduction of stakeholder engagement facilitates the identification of their social needs and enhances the value of the project [

41]. A person-centred care will treat older adults with dignity, contributing to the realisation of their well-being [

42].

Second, aged care PPPs should adopt a socially sustainable process. Research on social sustainability indicates that merely defining the project's goals is insufficient, it is also crucial to focus on how these goals are achieved. In other words, organisations should implement specific actions and procedures when pursuing sustainable development [

43]. The case study in this paper demonstrates that the delivery of socially sustainable services in Project X relies on a socially sustainable process, involving 33 CPs undertaken by various stakeholders at different stages of the project’s lifecycle. As noted by (Anonymised for Review #1), achieving social sustainability in aged care PPP projects follows a backcasting process. This involves first establishing the project’s goal—social sustainability—and then enabling all participating parties to incrementally adopt CPs [

44].

5.2. Potential of Structuring PPP Projects for Social Sustainability

The case study also demonstrates that PPP projects have the potential to achieve social sustainability when properly structured. Existing research indicates that ineffective collaboration due to organisational structure and a lack of dynamic responsiveness to complex issues are common challenges for social sustainability in business organisations [

17]. The PPP model helps overcome these challenges.

First, PPPs facilitate the coordination of cross-sector resources and efforts [

45]. Such coordination represents a collaborative approach among diverse stakeholders, aiming to achieve desired results with minimal process losses [

46]. In Project X, several CPs such as CP-5, CP-6, and CP-11 all reflect the integration of resources such as data and technology between the public and private sectors, as well as among public sector entities. Existing research indicates that, compared to traditional models, PPPs help improve the efficiency of cross-sector coordination [

47], directly contributing to the achievement of the United Nations SDGs [

48].

Second, PPPs demonstrate inherent flexibility. It manifests in multiple aspects, such as contract flexibility, decision-making flexibility, and product flexibility [

49]. Flexibility enables project teams to adapt to changing environments and handle unforeseen events throughout the lifecycle [

50]. It may also enhance project performance and value [

51]. Take the partner selection of Project X as an example. By establishing a competitive procurement strategy (CP-12) and adopting a comprehensive scoring method (CP-13), it incentivised private investors to contribute more resources, thereby optimising project operations and outputs, and delivering greater social value. The potential flexibility of PPPs is corroborated by the research of [

52]. They found that flexibility enables PPPs to acquire information and expertise from the private sector while securing support from non-market stakeholders.

5.3. Synthesising Prescriptive Theorising with Backcasting to Support PPPs for Social Sustainability

Having elaborated on the importance of social sustainability and the potential of PPPs, we now shift our focus to discuss how to better support PPPs in achieving this goal. Our research demonstrates the power of synthesising prescriptive theorising with backcasting.

Prescriptive theorising guided this study in clearly articulating the ideal outputs of aged care PPPs and providing CPs to achieve them. It is primarily used to address normative ("how things should be") and instrumental ("how to achieve them") questions, aiming to actively generate desired outputs by steering social actions toward alternative states [

37]. As both a theoretical paradigm and practical tool, prescriptive theorising has been applied in management research [

53]. Following [

37], this study implemented prescriptive theorising through two steps: defining/justifying specific goals and defining/justifying the means to achieve them. Social sustainability is established as the goals for the selected case, with CPs identified.

Furthermore, the backcasting method serves as a transformative mechanism, which has successfully traced, through case study, the specific realisation paths for phased adoption of 33 CPs to achieve 21 social sustainability indicators. Due to its normative, goal-oriented, and problem-solving characteristics, backcasting is particularly suited to addressing long-term urban challenges and formulating sustainable solutions [

54]. It has now become a widely adopted research approach for tackling sustainability challenges and driving transformative change [

55]. The method enables researchers and practitioners to systematically integrate fragmented knowledge and tailor approaches to specific projects [

56].

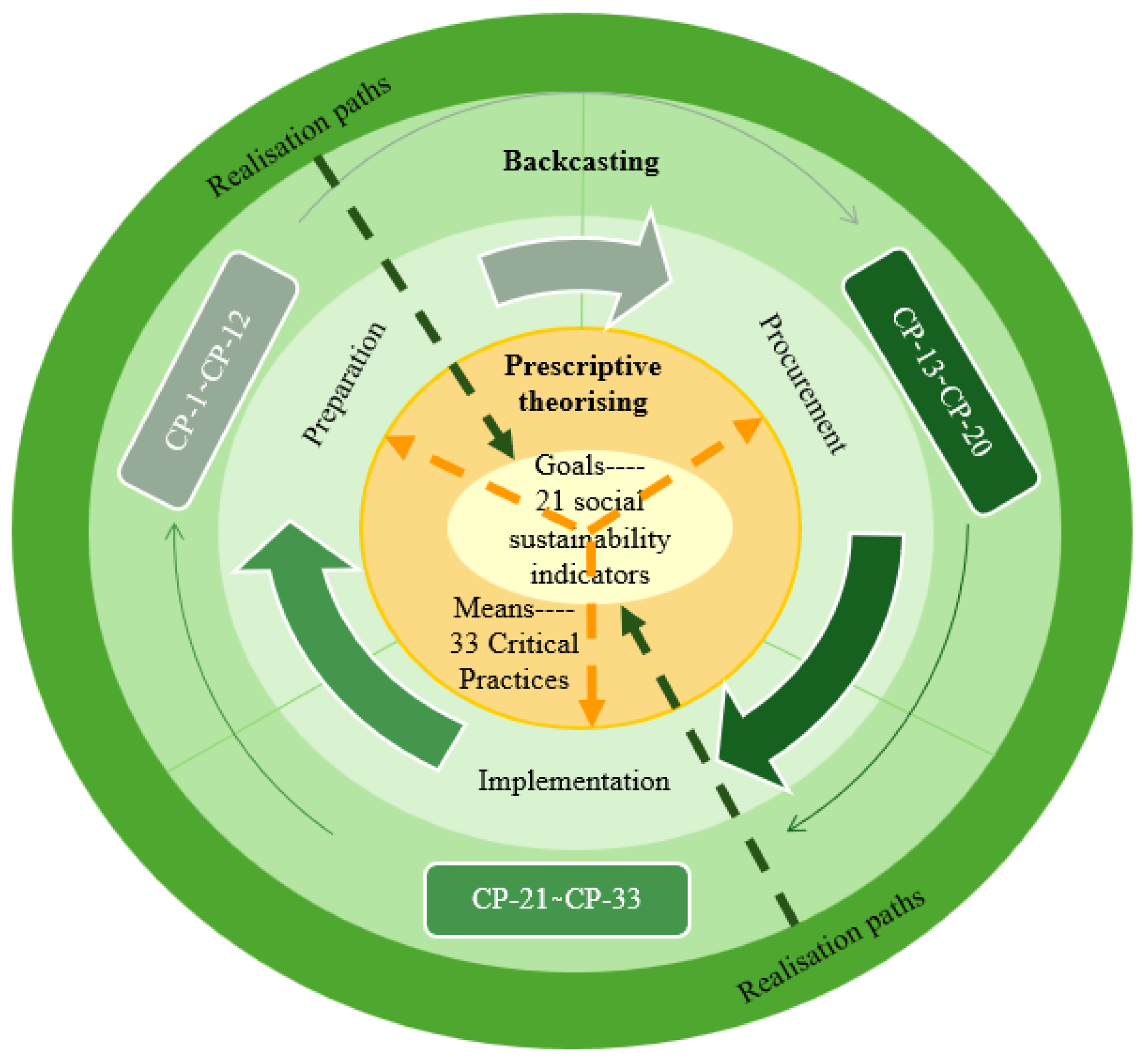

The synthesis of prescriptive theorising with backcasting can better support PPPs in achieving goals. In this study, the former guides the identification of 21 social sustainability indicators and 33 CPs, providing a normative framework. The latter connects the indicators, CPs, and project processes to design reverse pathways.

Figure 4 illustrates this synthesis. The two yellow concentric circles at the center represent the contributions of prescriptive theorising, while the three green concentric circles surrounding them denote the contributions of backcasting. The orange and dark green dashed arrows respectively signify the guidance from prescriptive theorising to backcasting and the supportive feedback from backcasting to prescriptive theorising.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

The case study suggests that achieving social sustainability in aged care PPP projects involves backcasting from established goals, representing a socially sustainable development process. Social sustainability should be the ultimate goal, symbolising a state of success. The backcasting method helps achieve the goal by requiring the public sector, private investors, and the SPV to adopt a series of CPs at different stages and phases of the life cycle.

The importance of social sustainability for PPP projects and the potential of structuring PPP projects to achieve social sustainability are discussed. PPPs' cross-sector coordination capabilities and flexibility enable them to attain these objectives. This paper further examines supportive approaches to better assist PPPs in achieving their goals—specifically, the synthesis of prescriptive theorising and backcasting. These two exhibit a complementary and progressive relationship of theoretical guidance and practical feedback in supporting PPPs to achieve their goals.

The research findings contribute to a deeper understanding of optimising PPPs to address complex social issues. While the indicator framework and realisation paths for the social sustainability of aged care projects were proposed in the authors' earlier work, this paper's novel contribution lies in demonstrating the process, potential, and approach of achieving social sustainability through PPPs. This provides valuable insights for other developing countries or emerging economies considering PPPs to address social challenges, particularly in aged care service provision. The research findings help public and private sectors refine policies, strengthen governance, and enhance the long-term sustainability of aged care PPPs. The contributions extend beyond the aged care sector, highlighting the broad applicability of social sustainability-oriented PPP models in tackling global social challenges.

This study has three main research limitations. First, it focuses on a single case within the Chinese context. Although single case studies are widely adopted in research examining the interrelationships among aged care, PPPs, and sustainability, it is undeniable that there are local differences and specific contextual factors. This limitation may constrain the generalisability of the research findings. Second, the selected case has only been in operation for a short period, limiting the long-term validation of the PPP model’s potential in achieving social sustainability. Third, this single case study involved only three respondents. It must be acknowledged that the limited number of interviewees may lead to insufficient data collection and potential bias in the results. However, as described before, this study is an integration of two existing foundational studies. The identification of complete CPs (a total of 42 CPs) is presented in (Anonymised for Review #1). These were derived from the analysis of three major cases and seventeen parallel reference cases, involving nine interviewees. Therefore, while the 33 CPs presented in this study for Project X were sourced from only three interviewees and related documents, they were cross validated against the broader set of cases in (Anonymised for Review #1).

Future research could consider selecting multiple cases or conducting cross-country and cross-industry comparisons to analyse the commonalities, differences, and underlying reasons for structuring PPPs to achieve social sustainability in different contexts. Longitudinal studies on cases are also encouraged.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Backcasting the realisation of Indicators of 1.1.1 and 1.1.2; Figure S2: Backcasting the realisation of Indicators of 1.2.1 and 1.2.2; Figure S3: Backcasting the realisation of Indicators of 2.1.1 and 2.1.2; Figure S4: Backcasting the realisation of Indicators of 2.3.1,2.3.2, and 2.3.3.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kun Wang; methodology, Yongjian Ke; validation, Yongjian Ke; formal analysis, Kun Wang; investigation, Kun Wang; resources, Yongjian Ke; writing—original draft preparation, Kun Wang; writing—review and editing, Yongjian Ke and Shankar Sankaran; supervision, Shankar Sankaran; funding acquisition, Kun Wang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Zhejiang Office of Philosophy and Social Science, grant number: 24NDJC062YB.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Here are the thirty-three CPs adopted by Project X. For supporting information used to identify them, such as the purpose or intent of a CP and its consequences or impacts, please refer to (Anonymised for Review #1).

CP-1: The Implementing Agency Gives Initial Consideration to Employees Well-being in the Feasibility Study

CP-2: The Implementing Agency Gives Initial Consideration to Elderly and Their Relatives Well-being in the Feasibility Study

CP-3: The Implementing Agency Gives Initial Consideration to Local Community and Society Well-being in the Feasibility Study

CP-4: The Implementing Agency Selects Consultant Who Contribute to Achieving Social Sustainability

CP-5: The Implementing Agency Assists the Consultants in the Investigation

CP-6: The Implementing Agency Introduces Stakeholder Engagement

CP-7: The Implementing Agency Develops Output Specification

CP-8: The Implementing Agency Identifies Risks and Establishes Response Plans

CP-9: The Implementing Agency Determines the Main Source of Profit, and Outlines an Initial Payment Mechanism

CP-10: The Implementing Agency Makes Initial Consideration of Contractual Arrangements

CP-11: The Implementing Agency Establishes a Preliminary Monitor Framework to Constrain the SPV's Behaviours

CP-12: The Implementing Agency Determines the Procurement Strategy to Best Procure the Required Outputs

CP-13: The Implementing Agency Determines to Use a Comprehensive Scoring Method to Select the Partners

CP-14: The Implementing Agency Sets the Terms of the Draft Contract

CP-15: The Private Investors Set the Goal of Participating in a Project

CP-16: The Private Investors Conduct Detailed Market Investigation

CP-17: The Private Investors Establish Person-Centred Overall Operation Schemes

CP-18: The Private Investors Establish Facility Maintenance Scheme

CP-19: The Implementing Agency Selects Appropriate Partner

CP-20: The Implementing Agency Signs PPP Contracts with the Winning Private Investor

CP-21: The SPV Defines Its Vision or Mission

CP-22: The SPV Drafts Documents of Quality Management System

CP-23: The SPV Involves Stakeholder Engagement

CP-24: The SPV Takes Over the Project as Agreed

CP-25: The SPV Provides Diversified Services for All Kinds of Elderly as Agreed

CP-26: The SPV Provides Good Human Resource Management for the Employees as Agreed

CP-27: The SPV Provides Contingency Response for Emergencies

CP-28: The SPV Performs Facility Maintenance as Agreed

CP-29: The SPV Self-Monitors the Outputs

CP-30: The Implementing Agency and other Government Departments Conduct Contract Implementation Monitoring

CP-31: The Implementing Agency Conducts Performance Evaluation

CP-32: The Implementing Agency Makes Information Public

CP-33: The Implementing Agency Pays the SPV on a Performance Basis

References

- Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Tiong, R. L. K. , Institutional quality configuration for encouraging private capital participation in PPP projects: evidence from 36 belt and road countries. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 2024, 17, 898–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Ke, Y.; Yang, Z.; Cai, J.; Wang, H. , Diversification or convergence: An international comparison of PPP policy and management between the UK, India, and China. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2020, 27, 1315–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, G.; Huemann, M. , Research Handbook on Sustainable Project Management. Edward Elgar Publishing: 2024.

- Hancock, L.; Ralph, N.; Ali, S. H. , Bolivia's lithium frontier: Can public private partnerships deliver a minerals boom for sustainable development? Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 178, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Liu, G.; Xu, Y. , Can joint-contract functions promote PPP project sustainability performance? A moderated mediation model. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2021, 28, 2667–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Fu, J. , Can relational governance improve sustainability in public-private partnership infrastructure projects? An empirical study based on structural equation modeling. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2023, 30, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. , Making sense of the definition of public-private partnerships. Built Environment Project and Asset Management ahead-of-print. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, S. R.; Ke, Y.; Devkar, G.; Mangioni, V.; Sankaran, S. , Handbook on Public–Private Partnerships in International Infrastructure Development: A Critical Perspective. Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024.

- Valdes-Vasquez, R.; Klotz, L. E. , Social Sustainability Considerations during Planning and Design: Framework of Processes for Construction Projects. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2013, 139, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, L. A.; Pellicer, E.; Yepes, V. , Social sustainability in the lifecycle of Chilean public infrastructure. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 2016, 142, 05015020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, N.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y. , Sustainability assessment of urban water public-private partnership projects with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria. Journal of the American Water Resources Association 2024, 60, 1209–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, J.; Xia, B.; Zou, J.; Zillante, G. , Sustainable retirement living: What matters? Australasian Journal of Construction Economics and Building, Conference Series 2012, 12, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, H. , Sustainable Performance Measurements for Public–Private Partnership Projects: Empirical Evidence from China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ke, Y.; Liu, T.; Sankaran, S. , Social sustainability in Public–Private Partnership projects: case study of the Northern Beaches Hospital in Sydney. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2022, 29, 2437–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordi, N. E.; Sheila, B.; and Che Ibrahim, C. K. I. , Mapping of social sustainability attributes to stakeholders’ involvement in construction project life cycle. Construction Management and Economics 2021, 39, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamnezhad, M.; Nasirzadeh, F.; Khanzadi, M.; Mohammad Jafar, J.; Ghayoumian, M. , Modeling social sustainability in construction projects by integrating system dynamics and fuzzy-DEMATEL method: a case study of highway project. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2020, 27, 1595–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missimer, M.; Mesquita, P. L. , Social sustainability in business organizations: A research agenda. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, G.; Schipper, R.; Planko, J.; Brink, J. v. d.; Planko, M. J.; Dalcher, P. D. , Sustainability in Project Management. Routledge: Farnham, UNITED KINGDOM, 2017.

- Hueskes, M.; Verhoest, K.; Block, T. , Governing public-private partnerships for sustainability: An analysis of procurement and governance practices of PPP infrastructure projects. International Journal of Project Management 2017, 35, 1184–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Ávila, C.; Hartmann, A.; Dewulf, G. , Contractual and Relational Governance as Positioned-Practices in Ongoing Public–Private Partnership Projects. Project Management Journal 2019, 50, 716–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Hao, S.; Li, X. , Project Sustainability and Public-Private Partnership: The Role of Government Relation Orientation and Project Governance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, F.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; An, X.; Dong, G. , Sustainable supplier selection for water environment treatment public-private partnership projects. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 324, 129218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwuagwu, A. O.; Poon, A. W. C.; Fernandez, E. , A scoping review of barriers to accessing aged care services for older adults from culturally and linguistically diverse communities in Australia. BMC Geriatrics 2024, 24, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Ke, Y.; Sankaran, S.; Xia, B. , Problems in the home and community-based long-term care for the elderly in China: A content analysis of news coverage. International Journal of Health Planning and Management 2021, 36, 1727–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Tam, V.; Ma, M. , Effective strategies for developing retirement village public – private partnership. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis 2021, 14, 821–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Tam, V.; Ma, M. , Risk Assessment of Retirement Village Public-Private Partnership Homes. Journal of Aging and Environment 2021, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Kyei, R.; Narbaev, T.; Atafo-Adabre, M.; Chileshe, N.; Ofori-Kuragu, J. K. , Critical success criteria for retirement village public – private partnership housing. Construction Innovation 2023, 23, 1018–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chan, W. K. , Public–private partnership in care provision for ageing-in-place: A comparative study in Guangdong, China. Australasian Journal on Ageing 2023, 42, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Zhang, L.; Geng, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, Y. , Research on Multi-Stage Post-Occupancy Evaluation Framework of Community Comprehensive Elderly Care Service Facilities under the Public-Private Partnership Mode—A Case Study of China. Buildings 2024, 14, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ke, Y.; Sankaran, S. , How Socially Sustainable Is the Institutional Care Environment in China: A Content Analysis of Media Reporting. Buildings 2024, 14, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. , Social sustainability of continuing care retirement communities in China. Facilities 2023, 41, 819–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ke, Y. , Towards sustainable development: Assessing social sustainability of Australian aged care system. Sustainable Development 2024, n/a, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Chen, Q.; Buys, L.; Skitmore, M.; Walliah, J. , Sustainable living environment in retirement villages: What matters to residents? Journal of Aging and Environment 2021, 35, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, B.; Zuo, J.; Skitmore, M.; Chen, Q.; Rarasati, A. , Sustainable retirement village for older people: A case study in Brisbane, Australia. International Journal of Strategic Property Management 2015, 19, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalicky Klemenčič, V.; Žegarac Leskovar, V. , Towards Inclusive and Resilient Living Environments for Older Adults: A Methodological Framework for Assessment of Social Sustainability in Nursing Homes. Buildings 2025, 15, 2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. , Market-Oriented Policies on Care for Older People in Urban China: Examining the Experiment-Based Policy Implementation Process. Journal of Social Policy 2022, 51, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanisch, M. , Prescriptive Theorizing in Management Research: A New Impetus for Addressing Grand Challenges. Journal of Management Studies 2024, 61, 1692–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, G.; Tourish, D. , The critical incident technique reappraised: Using critical incidents to illuminate organizational practices and build theory. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management 2016, 11, 276–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missimer, M.; Robèrt, K. H.; Broman, G.; Sverdrup, H. , Exploring the possibility of a systematic and generic approach to social sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 2010, 18, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European PPP Expertise Centre, The guide to guidance: How to prepare, procure and deliver PPP projects. European Investment Bank: 2011.

- Keeys, L. A.; Huemann, M. , Project benefits co-creation: Shaping sustainable development benefits. International Journal of Project Management 2017, 35, 1196–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Nakayama, T. , Empirical Research on the Life Satisfaction and Influencing Factors of Users of Community-Embedded Elderly Care Facilities. Buildings 2025, 15, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellitto, M. A.; Camfield, C. G.; Buzuku, S. , Green innovation and competitive advantages in a furniture industrial cluster: A survey and structural model. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2020, 23, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quist, J. N. , Backcasting for a sustainable future: The impact after 10 years. Eburon Academic Publishers: Delft, Netherlands, 2007.

- Doh, J. P.; Tashman, P.; Benischke, M. H. , Adapting to Grand Environmental Challenges Through Collective Entrepreneurship. Academy of Management 2019, 33, 450–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trauernicht, N.; Braaksma, J.; Haanstra, W.; van Dongen, L. A. M. , The Impacts on Interorganizational Project Coordination: A Multiple Case Study on Large Railway Projects. Project Management Journal 2024, 0, 87569728241265927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, E.; Fischer, R. D.; Galetovic, A. , The Economics of Public-Private Partnerships: A Basic Guide. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2014.

- World Bank Procuring Infrastructure Public-Private Partnerships Report 2018: Assessing Government Capability to Prepare, Procure, and Manage PPPs; Washington, 2018.

- Demirel, H. Ç.; Leendertse, W.; Volker, L.; Hertogh, M. , Flexibility in PPP contracts–Dealing with potential change in the pre-contract phase of a construction project. Construction Management and Economics 2017, 35, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, P. E.; Larsson, J.; Pesämaa, O. , Managing complex projects in the infrastructure sector — A structural equation model for flexibility-focused project management. International Journal of Project Management 2017, 35, 1512–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, R.; Sakhrani, V. , Appropriating the Value of Flexibility in PPP Megaproject Design. J. Manage. Eng. 2020, 36, 05020010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kwak, Y. H.; Cui, Q. , The Power(lessness) of Flexibility in Public–Private Partnerships: Two Capital Projects From the National Capital Region. Project Management Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Howard-Grenville, J.; Joshi, A.; Tihanyi, L. , Understanding and tackling societal grand challenges through management research. Academy of Management Journal 2016, 59, 1880–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S. E. , A methodological framework for futures studies: integrating normative backcasting approaches and descriptive case study design for strategic data-driven smart sustainable city planning. Energy Informatics 2020, 3, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogués, S.; González-González, E.; Stead, D.; Cordera, R. , Planning policies for the driverless city using backcasting and the participatory Q-Methodology. Cities 2023, 142, 104535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishita, Y.; Höjer, M.; Quist, J. , Consolidating backcasting: A design framework towards a users’ guide. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2024, 202, 123285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).