The integration of virtual reality, digital twins, and spatial behavior-tracking technologies is reshaping cultural exhibition architecture, shifting the design focus from functional efficiency to immersive, user-centered experiences. However, the behavioral dynamics within these interactive environments remain insufficiently addressed. This study proposes a behavior-oriented spatial typology grounded in Bitgood’s attention–value model, which maps the psychological stages—Attraction, Hold, Engagement, and Exit—onto four spatial categories: Threshold Space, Transitional Space, Narrative Focus Space, and Closure Space. Each represents a distinct phase of perceptual and behavioral response along the exhibition sequence. A mixed-method approach was employed, combining eye-tracking experiments with structured questionnaires to capture both physiological reactions and subjective evaluations. Key spatial variables—enclosure, visual corridors, spatial scale, and light–shadow articulation—were analyzed using multiple regression models to evaluate their effects on interest levels and dwell time. Results show that Threshold Spaces support rapid orientation and exploratory behavior, while Transitional Spaces aid navigation but reduce sustained attention. Narrative Focus Spaces enhance cognitive engagement and decision-making, and Closure Spaces foster emotional resolution and extended presence. These findings validate the proposed typology and establish a quantifiable link between spatial attributes and visitor behavior, offering a practical framework for optimizing immersive exhibition sequences.

1. Introduction

The design of cultural exhibition architecture is undergoing a paradigm shift, moving beyond static object display toward spatial systems that emphasize narrative immersion, interactivity, and emotional resonance. This evolution aligns with emerging visitor expectations in the digital era, where cultural spaces are increasingly tasked with fostering engagement through perceptual and behavioral experience.

Extensive research has demonstrated the influence of spatial geometry—particularly metrics such as integration and visual accessibility—on shaping visitor circulation patterns and emotional rhythms [

1,

2]. Concurrently, developments in immersive eye-tracking and virtual reconstruction technologies have enabled the empirical visualization of interactions between spatial characteristics and behavioral responses [

3,

4].

Digital twin and virtual reality (VR) technologies have redefined spatial logic in exhibition environments by enabling adaptive and interactive user experiences. Platforms such as Shanhai and the Palace Museum VR exemplify this shift toward responsive, feedback-oriented exhibitions that move beyond static, object-centered presentation [5,6,

7]. However, the underlying relationship between spatial configuration and behavioral intention remains underexplored, largely due to the lack of integrated theoretical models and empirical evidence linking spatial design to user engagement.

Three key limitations persist in current spatial behavior research. First, there is an overreliance on static visualizations, such as heatmaps, which inadequately capture the dynamic and sequential nature of spatial interaction. Second, the disjointed treatment of perceptual and behavioral data precludes the formation of a closed-loop model that connects spatial design, user feedback, and iterative improvement. Third, existing modeling efforts often prioritize content features or visitor demographics, overlooking the causal influence and contextual transferability of spatial attributes [

8,

9].

Bitgood’s attention–value model [

10], initially formulated to describe exhibit-level attention processes, outlines four cognitive stages: Attraction, Hold, Engagement, and Exit. This study extends the model’s conceptual scope by spatializing these stages into a typological framework for cultural exhibition architecture. The resulting four spatial types—Threshold Space, Transitional Space, Narrative Focus Space, and Closure Space—correspond to distinct phases of perceptual and behavioral interaction along the exhibition sequence, offering a structured lens to interpret user engagement in spatial terms.

Building on this typological framework, the study constructs a spatial–behavioral mapping model through a mixed-method approach that integrates immersive eye-tracking experiments and structured questionnaires. Four perceptual variables—enclosure, visual corridors, spatial scale, and light–shadow articulation—are analyzed using multiple regression to examine their effects on dwell time and perceived interest. The resulting model provides a quantitative basis for linking spatial configuration to visitor behavior and offers design strategies for optimizing non-exhibit areas in cultural exhibition architecture.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Spatial Rhythm and Behavioral Sequencing in Exhibition Spaces

The spatial configuration of cultural exhibition architecture plays a critical role in guiding perception and shaping behavioral responses. Popelka and Vyslouzil [

11] demonstrated that eye movement patterns are closely aligned with spatial legibility and orientation cues, suggesting that visual structure directly influences how visitors explore exhibition spaces. Raptis [

12] further revealed that attentional shifts in interactive environments tend to follow predictable spatial sequences, reinforcing the view that physical layout serves as a scaffold for cognitive and behavioral engagement. Liu and Sutunyarak [

13] emphasized that immersive spatial qualities—such as enclosure, lighting, and perceived scale—can significantly affect users’ focal attention and behavioral intention in exhibition settings.

From a curatorial perspective, Serrell [

14] proposed that exhibitions function as rhythmic sequences, progressing from perceptual entry to stages of sustained engagement and interpretive closure. This idea of structured experiential flow is supported by digital simulation studies. For instance, van Maanen et al. [

15] observed stable gaze trajectories across virtual museum tours, while Gong et al. [

16] found that augmented spatial cues can effectively regulate visitor attention. Carrozzino and Bergamasco [

17] demonstrated that virtual transitions can replicate the behavioral logic of real-world movement, and Charitonidou [

18] described architectural space as an event-driven continuum that orchestrates both emotional and cognitive shifts.

These insights highlight the potential of spatial sequencing to influence visitor behavior across multiple media and formats. Drawing on Bitgood’s attention–value model [

10]—which outlines four cognitive stages of Attraction, Hold, Engagement, and Exit—this study develops a corresponding spatial typology for exhibition environments. The four spatial types—Threshold Space, Transitional Space, Narrative Focus Space, and Closure Space—are designed to reflect distinct phases of perceptual orientation, attentional modulation, cognitive engagement, and emotional resolution. This typological framework serves as the theoretical foundation for analyzing spatial–behavioral relationships in cultural exhibition architecture.

2.2. Public Perception and Behavioral Response in Spatially Sequenced Exhibitions

As cultural exhibitions evolve toward immersive, participatory formats, spatial design increasingly shapes how visitors perceive, interpret, and emotionally respond to their surroundings. Rendell [

19] emphasized that transitional spaces—such as corridors, thresholds, or spatial pauses—often trigger psychological shifts and emotional reorientation, functioning as perceptual mediators within architectural sequences. From a narrative design perspective, De Bleeckere and Gerards [

20] suggested that spatial sequencing can be deliberately orchestrated to evoke interpretive depth and guide the visitor’s experiential rhythm.

Recent eye-tracking research reinforces this view. Rainoldi et al. [

21] found that gaze fixations frequently concentrate at points of spatial transition, indicating elevated perceptual engagement and memory encoding. Tao et al. [

22], examining post-industrial heritage spaces, argued that spatial rhythm serves not only an organizational role but also communicates cultural identity through sequential architectural experience. Complementing this, Wang [

23] highlighted that spatial form itself—independent of exhibits—can convey semantic meaning and influence cognitive response.

Emotional and perceptual responses are also shaped by contextual familiarity. Bo and Abdul Rani [

24] observed that visitors’ sense of attachment and preference is modulated by cultural familiarity and place-based associations, underscoring the subjective dimension of spatial experience.

These studies collectively suggest that perceptual variation across space types—whether in scale, enclosure, or cultural legibility—plays a significant role in shaping user behavior and emotional engagement. Building on this foundation, the present study incorporates both objective and subjective perceptual indicators to assess how spatial features influence interest levels and behavioral patterns across the exhibition sequence.

2.3. Integration and Modeling of Multi-Source Perceptual Data

Advances in spatial analytics and behavioral modeling have enabled increasingly granular investigations into how users perceive and interact with architectural environments. Spatial syntax analysis has demonstrated that global integration values can effectively predict movement density and spatial clustering in exhibition contexts [

25]. While such geometric metrics provide useful macro-level insights, they often fail to capture perceptual variation within localized spatial segments.

To address this limitation, recent studies have incorporated physiological and visual tracking methods to assess user response at the individual level. Shi et al. [

26] used mobile eye-tracking to map gaze distribution in museum settings, while Marín-Morales et al. [

27] combined biometric signals with immersive virtual navigation to evaluate emotional load and cognitive response. Davis [

28] further applied eye-tracking in VR environments to delineate perceptual stages among older visitors, highlighting how spatial engagement varies across cognitive profiles.

Semantic analysis complements physiological data by capturing perception through linguistic expression. Grootendorst [

29] introduced the BERTopic model to extract environmental themes from user-generated content, offering a scalable method to interpret spatial evaluations at the textual level. These multidimensional indicators can be further integrated through quantitative models. Banaei et al. [

30] developed regression frameworks that combine gaze duration, spatial attributes, and biometric data to predict users’ behavioral responses in interior settings. Additionally, O’Neill [

31] demonstrated that signage and floor plan configurations significantly influence wayfinding accuracy and decision-making patterns, confirming that spatial structure itself operates as a behavioral determinant.

Together, these studies underscore the growing sophistication of spatial–behavioral modeling across semantic, visual, and physiological dimensions. Building on this foundation, the present research adopts a multimodal approach to evaluate how specific spatial characteristics—such as enclosure, visual continuity, scale, and lighting—affect interest and dwell behavior across a typology of exhibition spaces.

2.4. Research Positioning and Methodological Strategy

Prior studies have independently highlighted the significance of spatial sequence, perceptual stimuli, and behavioral responses in shaping user experiences within exhibition environments. However, these dimensions often remain isolated, lacking a unified structure that systematically links spatial configurations to perceptual engagement and behavioral dynamics. While eye-tracking, semantic analysis, and physiological monitoring each offer valuable insights, few studies have integrated these modalities into a cohesive, design-oriented evaluation model. Moreover, existing classifications of exhibition spaces primarily emphasize functional or curatorial dimensions, with limited attention to the perceptual–behavioral transitions that occur along the visitor journey.

To address this methodological fragmentation, this study proposes a spatial typology grounded in user experience, extending Bitgood’s attention–value model into four corresponding space types: Threshold Space, Transitional Space, Narrative Focus Space, and Closure Space. Each type is associated with distinct perceptual and behavioral roles—ranging from initial orientation to prolonged engagement and emotional resolution. By mapping physiological metrics (e.g., gaze patterns), spatial indicators (e.g., enclosure, scale), and subjective responses (e.g., interest levels), the study develops a data-driven framework for assessing user interaction across these typologies.

This approach not only integrates diverse perceptual data but also anchors them within a typological structure that aligns with design intentions. Multiple regression models are employed to quantify the influence of spatial attributes on two key behavioral outcomes: interest intensity and dwell duration. The resulting insights support a nuanced understanding of how architectural features modulate user attention, decision-making, and emotional resonance within sequential exhibition spaces.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Object

To explore how spatial layout influences visitor engagement in cultural exhibition environments, this study began with a comparative analysis of twelve internationally recognized museums. The selection focused on architectural cases with distinctive circulation strategies, clear spatial progression, and alignment with the study’s research focus. From this set, three institutions were selected as primary research objects: the Chichu Art Museum (Japan), the National Museum of Western Art (Japan), and the East Building of the National Gallery of Art (United States). These museums offer structured spatial transitions and diverse exhibition approaches, making them suitable for analyzing the relationship between spatial configuration and visitor behavior.

3.2. Research Framework

This study centers on the examination of prototypical spatial sequences in cultural exhibition environments, with the goal of elucidating the coupling mechanisms between spatial configuration and visitor behavioral response. The research adopts an integrative methodological framework combining quantitative metrics with qualitative diagnostic tools to support evidence-based spatial optimization.

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the framework proceeds in three stages. First, a spatial–behavioral mapping is constructed to correlate spatial nodes with patterns of visitor attention and preference. Second, a multiple regression model is applied to evaluate the influence of key spatial perception variables—such as enclosure, scale, lighting, and visual continuity—on average dwell time and self-reported interest levels. Finally, behavioral preferences are identified and linked to specific spatial triggers within distinct spatial typologies (Threshold Space, Transitional Space, Narrative Focus Space, Closure Space), enabling actionable insights for the design and evaluation of immersive exhibition sequences.

3.3. Research Procedure

The research process is structured into three interrelated stages, integrating spatial modeling, experimental testing, and quantitative analysis to examine the relationship between spatial sequencing and visitor perception in cultural exhibition buildings.

1)Stage 1: Spatial Path Modeling and Experimental Material Development

Based on a literature review and case analysis, the exhibition sequences of museum buildings are categorized into five typical spatial nodes according to the “Threshold Space, Transitional Space, Narrative Focus Space, and Closure Space” narrative logic. Three selected buildings are modeled in 3D using their architectural plans. Fifteen high-fidelity panoramic views of spatial nodes are rendered using the D5 Engine, serving as visual stimuli for the immersive experiment [

32].

2)Stage 2: Eye-Tracking Experiment and Subjective Data Collection

The panoramic images are imported into an eye-tracking platform. A total of 60 undergraduate and graduate students from diverse academic backgrounds participate in the experiment, simulating realistic visitor experiences [

33]. The experiment collects two types of data simultaneously: eye-tracking metrics and subjective perception feedback, enabling the quantification of attention patterns and perceptual preferences.

3)Stage 3: Data Analysis and Model Construction

Based on the experimental data, a spatial–behavioral map is developed to visualize the average interest ratings and dwell time, and behavioral preferences associated with each spatial node. Multiple regression analysis is then used to quantitatively evaluate the influence of four spatial perception variables across four types of space (“Threshold Space”, “Transitional Space”, “Narrative Focus Space”, “Closure Space”) on spatial attractiveness and dwell behavior. The findings provide empirical support and design strategies for enhancing the spatial experience in cultural exhibition buildings.

4. Experimental Design

4.1. Extraction of Spatial Sequences in Cultural Exhibition Buildings

This study extends Bitgood’s attention–value model from exhibit-level analysis to a continuous spatial framework. The four psychological stages—Attraction, Hold, Engagement, and Exit—are mapped to four spatial categories reflecting sequential visitor experience: Threshold Space (orientation), Transitional Space (movement adjustment), Narrative Focus Space (deep engagement), and Closure Space (emotional resolution). This typological reinterpretation offers a structured lens for analyzing behavior along exhibition paths.

Based on literature and typological synthesis [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18], five spatial node types (S1–S5) were defined and aligned with the four-stage framework, forming a generalized model for cultural exhibition buildings. Three representative cases were analyzed: the Chichu Art Museum, the National Museum of Western Art, and the East Building of the National Gallery of Art. In each, zones such as entry halls, atria, staircases, galleries, and terraces were assigned to spatial categories based on their behavioral functions. For instance, the Chichu Art Museum’s entry and stairs were classified as Threshold and Transitional Spaces, while its terrace served as Closure Space. Similar mappings were observed in the other two cases, supporting the framework’s applicability for spatial–behavioral analysis.

Table 1.

Classification of Twelve Representative Cultural Exhibition Buildings.

Table 1.

Classification of Twelve Representative Cultural Exhibition Buildings.

| Spatial Node Type |

Threshold Space |

Transitional Space |

Narrative Focus Space |

Closure Space |

| Nariwachō Art Museum |

Entrance Hall |

Atrium, Vertical Staircase |

Transitional Platform |

Viewing Terrace |

| National Museum of Western Art (Tokyo) |

Entrance Hall |

Atrium, Zigzag Staircase |

Transitional Platform |

Viewing Terrace |

| National Gallery of Art, East Building |

Entrance Hall |

Atrium, Vertical Staircase |

Transitional Platform |

Viewing Terrace |

| Wen Exhibition Seaside Pavilion |

Entrance Hall |

Atrium, Vertical Staircase |

Transitional Platform |

Upper-Level Platform |

| Chengdu Cultural Exhibition Hall |

Entrance Hall |

Atrium |

Linear Exhibition Hall |

Viewing Terrace |

| Guangzhou Contemporary Exhibition Hall |

Main Gate |

Atrium |

Zigzag Staircase |

Top Exhibition Hall |

| Mediterranean Museum of Modern Art |

Underground Passage |

Atrium |

Linear Exhibition Hall |

Upper Exhibition Hall |

| MAXXI National Museum of 21st Century Arts |

Upper-Level Entrance Hall |

Double-Layered Platform |

Spiral Staircase / Connector |

Top Exhibition Hall |

| Museo Experimental El Eco |

Main Entrance Hall |

Skylight Court |

Corridor / Entrance Hall |

Top Exhibition Hall |

| Muzeum Susch |

Underground Passage |

Cooling Space |

Corridor / Colonnade Space |

Exhibition Hall |

| Oscar Niemeyer Museum |

Underground Passage |

Hall under Water Pool |

Glass Corridor / Staircase |

Top Exhibition Hall |

| Kunsthaus Bregenz |

Entrance Hall |

Atrium Exhibition Hall |

Circular Path / Staircase |

Top Exhibition Hall |

4.2. Experimental Materials

The study selected three representative museum buildings—Nariwachō Art Museum (S1–S5), National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo (S6–S10), and the East Building of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (S11–S15). Five typical spatial nodes were extracted from each building, resulting in a total of 15 nodes. Based on 2D architectural plans, 3D models were constructed and rendered using the D5 Engine under a unified environmental setting [

34], including standardized parameters such as human scale, concrete material textures, and consistent light–shadow articulation conditions. This normalization process eliminated potential distractions from color and material differences, allowing the experiment to focus on spatial configuration. It aligns with best practices in VR-based and eye-tracking experiments regarding variable control.

The questionnaire consisted of two primary dimensions: spatial perception factors and behavioral preferences.

a) Spatial perception factors included enclosure [

35], visual corridors [

36], spatial scale [

37], and light–shadow articulation [

38]. These core elements are widely recognized for their impact on spatial perception and emotional experience.

b) Behavioral response types were categorized along a “dynamic–static” spectrum into six types [

39]: swift traversal, social interaction, spontaneous exploration, navigational hesitation, prolonged gaze, and contemplative engagement. Instead of relying on real-time observation, participants were asked to select their preferred behavior based on their own immersive experience [

40], serving as the primary source of behavioral data.

4.3. Experimental Procedure

To investigate how spatial node composition influences visitor behavior and spatial interest, the experimental procedure was divided into three stages. The design was adapted from the architectural experience evaluation method in virtual environments proposed by Zou and Ergan [

41]:

Participants were first instructed to read and become familiar with the content of the subjective questionnaire. They then completed the setup and calibration of the eye-tracking device (Tobii Pro VR headset) to ensure data accuracy and stability.

- 2)

Immersive Browsing Stage:

Participants freely explored 15 virtual 3D spatial nodes in sequence. All nodes were rendered using consistent visual parameters to ensure uniform visual input. The system automatically recorded eye-tracking and physiological data, while the experimenter manually recorded dwell time for each node to simulate the natural duration of spatial engagement.

- 3)

Subjective Questionnaire Stage:

After browsing, participants completed a recall-based questionnaire evaluating four categories of spatial perception and six categories of behavioral preference. This stage complemented objective data with subjective cognitive feedback, enhancing the analytical basis for understanding spatial–behavioral relationships.

5. Results

5.1. Results of Eye-Tracking Data Analysis

5.1.1. Analysis of Visual Attention: Heatmaps and Scan-Paths

To evaluate the impact of spatial characteristics on visual attention, eye-tracking data were analyzed across four perception variables: enclosure, visual corridors, spatial scale, and light–shadow articulation. As shown in

Figure 2, heatmaps reveal that spatial nodes S6, S8, and S9 concentrated a significantly higher density of visual fixations—approximately 1.8 times the sample mean. These nodes shared common features, including clearly defined visual corridors and high luminance contrast, which likely enhanced visual anchoring.

In contrast, nodes such as S2, S7, and S10 exhibited dispersed fixation distributions, with densities over 25% below the mean. These spaces were characterized by weak enclosure and an indistinct sense of spatial hierarchy, contributing to reduced perceptual salience.

The scan-path diagrams reveal that nodes S6 and S8 elicited significantly fewer saccadic movements—approximately 35% below the sample mean—suggesting more stable gaze trajectories and enhanced spatial coherence. In contrast, nodes S2 and S15 exhibited elevated gaze variability, with average saccadic amplitudes exceeding the mean by 28%. This pattern reflects a deficiency of salient visual cues and limited enclosure, leading to increased exploratory eye movements and reduced cognitive mapping efficiency.

5.1.2. Eye-Tracking Metrics Analysis

To further validate the psychological perception underlying visual behavior, this study introduces three key eye-tracking physiological indicators, as shown in

Table 2.

The three eye-tracking physiological indicators—pupil diameter (PPD), blink count (BC), and saccade count (SC)—offer objective metrics for assessing users’ spatial perception and cognitive responses. An increased PPD typically indicates heightened cognitive load or emotional arousal, often triggered by visually rich or information-dense environments [

42]. A higher BC may signal reduced attentional focus or the onset of visual fatigue, reflecting either diminished spatial coherence or a lack of directional cues [

43]. Elevated SC values are generally associated with intensified visual search behavior, commonly occurring in spatial configurations with high complexity or dispersed focal elements [

44]. Together, these physiological parameters form a quantitative foundation for interpreting perceptual demands, attentional engagement, and user interaction with varying spatial conditions.

Based on the spatial sequencing of the three selected buildings into the stages of “Threshold Space, Transitional Space, Narrative Focus Space, and Closure Space”, the influence of spatial perception factors on visual behavior and cognitive load exhibits distinct stage-based variations, as shown in

Table 3. At the Threshold Space (S1, S6, S11), visual corridors and light–shadow articulation conditions are favorable, resulting in concentrated fixations and coherent gaze trajectories with relatively low cognitive load. At the Transitional Space (S2, S3, S7, S8, S12, S13), variations in enclosure and spatial scale increase visual jumping and spontaneous exploration, accompanied by elevated cognitive demand. Narrative Focus Space (e.g., S4, S9, S14) feature localized light–shadow articulation contrasts that intensify visual focus and increase cognitive processing. At the Closure Space (S5, S10, S15), reduced enclosure and scale lead to more dispersed fixations and divergent gaze patterns, while cognitive load remains relatively high.

Heatmaps and eye-tracking trajectories visually illustrate the distribution of spatial attention, while physiological indicators effectively reflect cognitive states. The integration of both offers deeper insights into how spatial perception factors dynamically shape visual paths and psychological responses across architectural space sequences.

5.1.3. Ethics Statement

This study did not involve personal or sensitive data and, under the policies of School of Architecture, Chang’an University, did not require formal ethical review. The experiment involved anonymous eye-tracking of visual behavior during simulated exhibition experiences.

All participants were informed of the study’s aims, procedures, and data handling protocols prior to participation. Written informed consent was obtained, and participants were free to withdraw at any stage. No identifiable personal information was collected, and all data were anonymized before analysis.

5.2. Construction of the Spatial–Behavioral Mapping

To visually represent the coupling between spatial configuration and behavioral preferences, a spatial–behavioral map was developed. In this map, node area indicates dwell time, color intensity reflects interest level, and bar charts display behavioral frequency. The mapping integrates dwell time data from eye-tracking experiments with behavioral preferences and interest ratings obtained from subjective questionnaires.

5.2.1. Analysis of Spatial Nodes Based on Interest Ratings and Dwell Time

The interest level was quantified using the Calt scoring method [

45], which categorized participants’ interest in spatial nodes into five levels: not interested (−1), unnoticed (0), neutral (1), somewhat interested (2), and highly interested (3). This approach enabled the objective evaluation of subjective interest (see

Table 4).

According to the data on average dwell time across spatial nodes shown in

Figure 3, Nodes S7 and S15 exhibited the longest dwell times, reaching 17.72 seconds and 18.36 seconds, respectively—among the highest across all nodes. In terms of average interest ratings, Nodes S13 and S15 received the highest ratings, at 7.0 and 7.2, indicating strong spatial appeal.

Despite a general alignment between dwell time and interest ratings, several nodes exhibit notable divergences. For instance, Node S3 shows an increase in dwell time from 14.32 to 15.12 seconds compared to S2, yet its interest rating declines to 6.16. Similarly, Node S7 ranks second in dwell time (17.72 s) but registers a moderate interest rating of 6.2. Node S11, with the third-longest dwell time (17.04 s), receives an interest rating of only 5.8—the second-lowest among all nodes.

These discrepancies indicate that prolonged spatial engagement does not necessarily imply heightened interest. Additional evidence from eye-tracking heatmaps further supports this observation: areas of intense visual focus do not consistently correspond to higher subjective preference. Thus, neither dwell time nor visual attention, when considered in isolation, provides a comprehensive measure of spatial effectiveness. This highlights the need for multi-dimensional evaluation frameworks that integrate behavioral, perceptual, and attitudinal data.

5.2.2. Discussion and Analysis

As illustrated in

Figure 4, the spatial–behavioral mapping, where dwell time and interest levels are visually encoded through the size and color intensity of each rectangular node. Nodes S15, S7, and S11 exhibit the largest spatial footprints, corresponding to prolonged dwell times. Notably, S15 and S13 display the most saturated warm hues, indicating the highest average interest ratings among all observed nodes. Visitor’s behavior shows marked differences across the four spatial types, revealing spatial dependency in engagement patterns.

Threshold Spaces (S1, S6, S11) primarily elicited dynamic behaviors, notably spontaneous exploration and swift traversal. Static actions—such as visual fixation and navigational hesitation—occurred moderately, while social interaction and reflective pauses were rare.

Transitional Spaces (S2, S3, S7, S8, S12, S13) showed a more balanced behavioral profile. Dynamic activity remained dominant, especially quick movement and exploration, accompanied by intermittent visual fixation. Prolonged gaze and stationary engagement were limited, suggesting an emphasis on spatial flow over attentional depth.

Narrative Focus Spaces (S4, S9, S14) were associated with higher frequencies of static behaviors, particularly extended fixation and hesitation, reflecting increased cognitive engagement. Dynamic behaviors persisted, indicating a layered interaction mode.

Closure Spaces (S5, S10, S15) exhibited high levels of both exploration and prolonged gaze, suggesting intensified attention and reflective processing toward the end of the spatial sequence.

Across the typologies, the relative distribution of the six observed behavior categories is clearly spatially mediated. This spatial variance also influences the overall dynamic-to-static behavior ratio, offering a potential framework for optimizing spatial rhythm and curatorial flow within exhibition design.

5.3. Results of Spatial Factor Analysis

To systematically investigate how spatial perception factors influence visitor interest and dwell behavior, this study employs multiple regression analysis to develop two models: the “Average Interest Ratings Model” and the “Average Dwell Time Model.” These models use average interest ratings and dwell time as dependent variables, and four core spatial perception variables as independent variables, to quantitatively analyze the impact paths of spatial attributes on both subjective perception and actual behavior. The average interest Ratings reflects the perceived attractiveness of a spatial node, while the average dwell time measures its actual usage intensity. The regression results help identify key spatial perception factors influencing visitor behavior, offering quantitative evidence and theoretical support for optimizing spatial nodes.

5.3.1. Statistical Results of the Regression Model

As shown in Table 5, the prediction model for average interest Ratings (Y₁ = α₀ + ∑₁⁴ αᵢXᵢ + ε) demonstrates an excellent fit (R²=1.000), with all regression coefficients statistically significant (p≈0), no multicollinearity (VIF < 2), and residuals approximately normally distributed. The model shows robustness and generalizability, with a five-fold cross-validated mean squared error (MSE) of 0.143. The results indicate that enclosure has a significant negative impact on interest (α=–0.094), suggesting that enclosed spatial structures may reduce perceived attractiveness. In contrast, visual corridors have a minor negative influence (α=–0.007), implying that visual corridors contributes little to interest enhancement. Spatial scale exhibits a positive effect (α = 0.042), indicating a positive correlation between appropriate spatial scale and user interest, where well-balanced proportions tend to increase spatial appeal.

In the model for average dwell time (Y₂ = β₀ + ∑₁⁴ βᵢXᵢ + ν), similarly high explanatory power is observed (R² = 1.000), with all statistical indicators significant. Consistent with the interest model, enclosure exerts a strong negative effect on dwell time (β = –0.319), suggesting that enclosed environments may shorten visitor stay. In contrast, visual corridors show a positive influence (β = 0.022), indicating that spatial legibility and visual corridors positively contribute to extended dwell duration. Both regression models were developed using SPSS 26.0 [

46], and their strong explanatory performance provides empirical support for understanding how spatial features affect visitor responses.

Table 5.

Regression Coefficients of Variables in the Average Interest Ratings Model and Average Dwell Time Model.

Table 5.

Regression Coefficients of Variables in the Average Interest Ratings Model and Average Dwell Time Model.

| Variable |

Regression Coefficient (α) for Interest Model

|

Regression Coefficient (β) for Dwell Time Model |

| Constant |

9.503 |

-1.173 |

| Enclosure (X₁) |

-0.094 |

-0.319 |

| Visual corridors (X₂) |

-0.007 |

0.022 |

| Spatial Scale (X₃) |

0.042 |

0.186 |

| Light–Shadow Articulation (X₄) |

-0.057 |

0.156 |

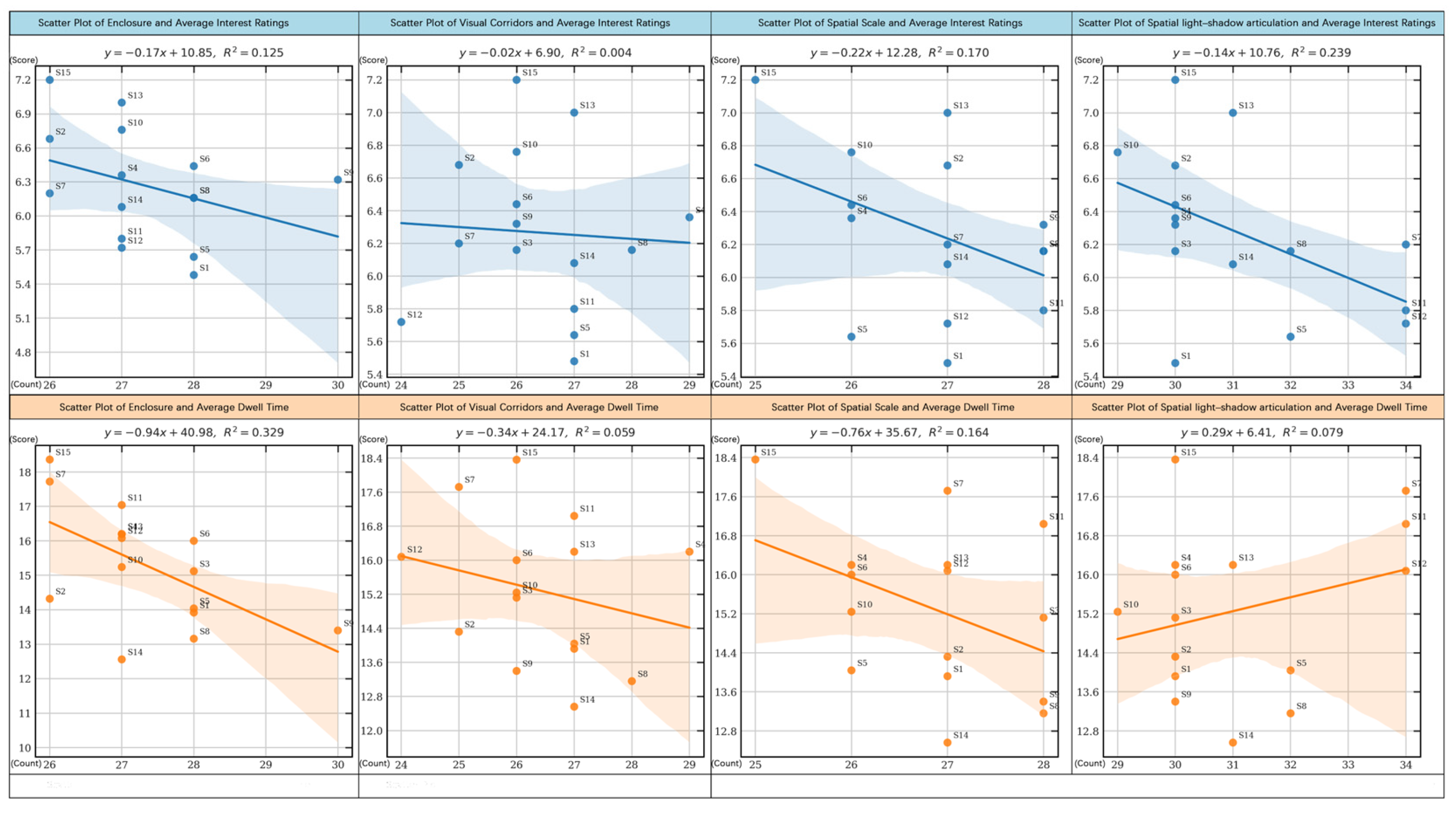

5.3.2. Visualization of the Influence Trends of Spatial Factors

The chart and table group (

Figure 5) illustrates the relationship between average interest ratings and spatial perception variables. Enclosure shows a negative impact, particularly evident at nodes S15 and S7 (R²= 0.125 and 0.170), suggesting that a stronger enclosure may reduce visitor interest. Visual corridors influence is minimal; at node S6, it is nearly insignificant (R²= 0.004), and a weak negative correlation is observed at node S15 (R² = 0.004). A spatial scale also shows a negative correlation at nodes S6 and S14 (R² = 0.170 and 0.239), indicating that larger perceived scale may decrease visitor interest. The influence of light–shadow articulation follows a generally negative trend, with relatively strong negative correlations at nodes S2 and S15 (R² = 0.239 and 0.170). Overall, enclosure and scale are the dominant factors affecting interest ratings, while light–shadow articulation design plays a weaker role in most cases, though it shows more pronounced negative effects at specific nodes such as S2 and S15.

Regarding the relationship between average dwell time and spatial perception variables, enclosure again exhibits a strong negative effect, especially at nodes S15 and S7 (R² = 0.329 and 0.164). Visual corridors show little impact across most nodes; at S2, its influence is negligible (R² = 0.059), while node S12 displays a slight negative effect (R² = 0.079). A spatial scale is negatively correlated with dwell time, with node S10 showing a particularly notable effect (R² = 0.164), indicating that larger spaces may reduce the duration of stay. The impact of light–shadow articulation on dwell time is more complex. While generally weak, a slight positive correlation appears at S10 (R² = 0.079), whereas negative effects are observed at nodes S7 and S6. In summary, enclosure has the most significant influence on dwell time, while the effects of scale and light–shadow articulation are weaker and should be fine-tuned according to the characteristics of each spatial node.

5.3.3. Summary

In different spatial types, participants’ interest ratings and dwell time were significantly influenced by specific spatial perception factors. In “ Threshold Space “ spaces, interest ratings were negatively affected by enclosure (α = -0.094), with enclosure also being the primary factor influencing dwell time (β = -0.319). In “ Transitional Space “ spaces, enclosure had the strongest negative effect on interest ratings, while perceived scale showed the most significant positive impact on dwell time (β = 0.186). In “ Narrative Focus Space “ spaces, perceived scale had the largest effect on interest ratings, while visual corridors influenced dwell time. In “ Closure Space “ spaces, light–shadow articulation conditions had a strong negative impact on interest ratings (α = -0.057), while both perceived scale and light–shadow articulation exerted positive effects on dwell time (β = 0.186 and 0.156, respectively).

Overall, enclosure showed a consistent and significant negative impact on both interest and dwell time, especially the latter. In contrast, perceived scale had a positive effect on both variables, indicating that greater spatial openness tends to increase dwell duration. Visual corridors had minimal influence and could be considered negligible. Light–shadow articulation conditions negatively affected interest ratings but positively influenced dwell time. In summary, enclosure plays a dominant role in reducing visitor engagement and retention, while perceived scale and light–shadow articulation conditions primarily contribute to extended dwell time through positive modulation.

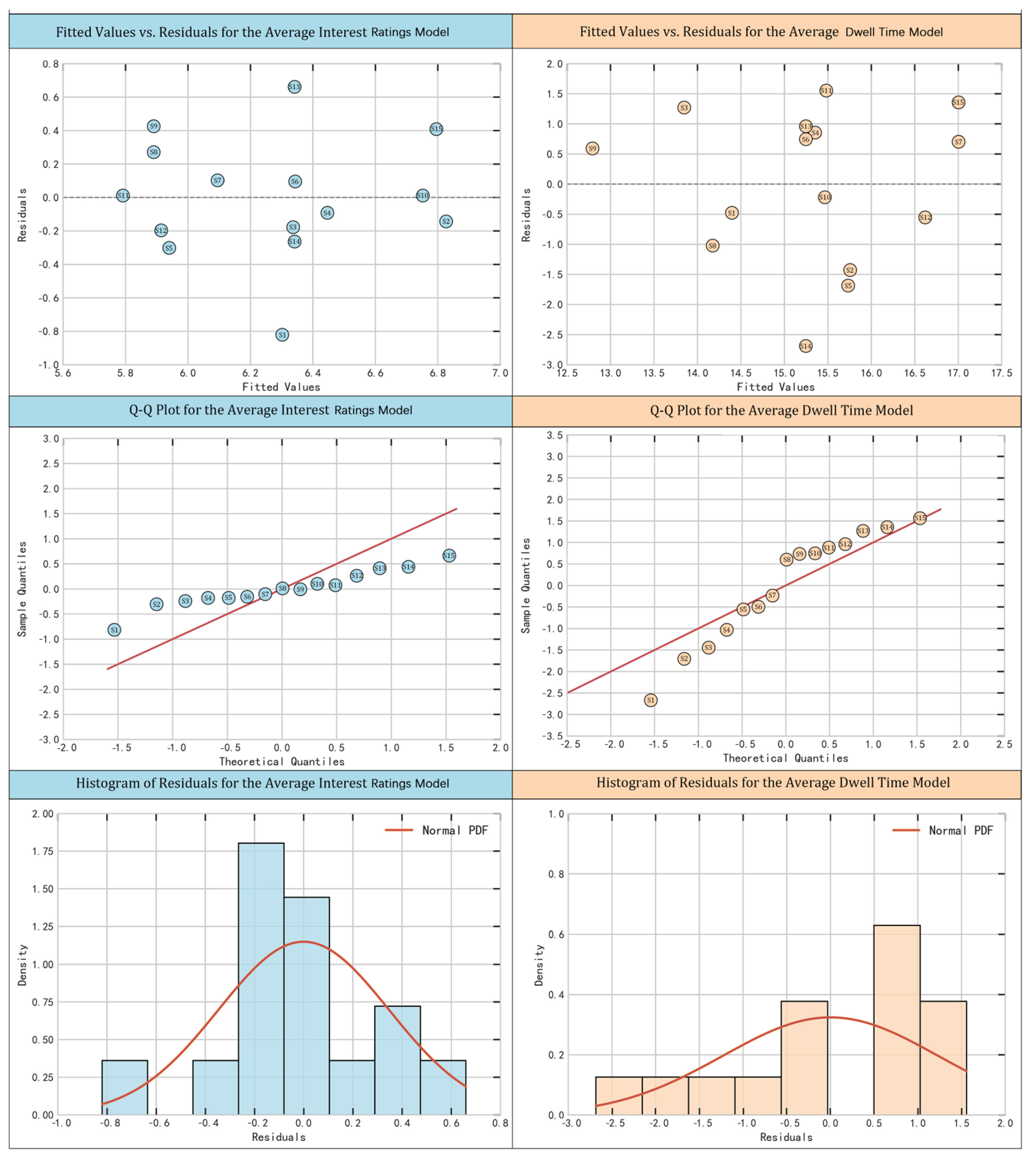

5.3.4. Residual Diagnostics for Regression Assumption Validation

To ensure the statistical robustness of the regression models predicting visitor interest and dwell time, a series of residual diagnostics were conducted, including residuals-versus-fitted value plots, quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plots, and residual histograms overlaid with theoretical normal distributions (

Figure 6). These visual assessments were employed to test the underlying assumptions of linearity, homoscedasticity, and normality.

For the interest Ratings model, residuals are evenly dispersed around the zero baseline, exhibiting neither systematic curvature nor funnel-shaped patterns. This confirms both linearity and homoscedasticity. The residuals-versus-fitted plot shows a consistent horizontal band, with no outliers or high-leverage points among the spatial nodes (S1–S15).

The Q–Q plot displays a strong alignment of standardized residuals with the 45-degree reference line, indicating approximate normality. Minor deviations at the distribution tails fall within acceptable limits for moderate-sized samples. The residual histogram corroborates this, closely approximating a normal bell curve with slight variance. Collectively, these diagnostics support the conclusion that the core regression assumptions are sufficiently met for the interest model.

The residuals-versus-fitted plot for the dwell time model shows general symmetry, but with a mild fanning pattern at higher fitted values, suggesting slight heteroscedasticity. This may reflect increased behavioral variability in spatial zones with extended engagement durations. A few spatial nodes exhibit larger residual spread, especially at the upper prediction range.

The Q–Q plot shows an overall linear trend, yet with noticeable heavy tails at both ends—indicative of potential deviations from normality. These outliers may arise from uneven dwell-time distributions across spatial types. The residual histogram echoes this, with a right-skewed and mildly flattened shape, diverging from the ideal Gaussian form.

Despite these moderate departures from ideal diagnostic profiles, the model remains statistically reliable. Consistent plotting formats and labeled spatial nodes across both models enhance visual interpretability and facilitate comparative assessment. While the dwell time model exhibits slightly greater variance, it retains practical validity for spatial-behavioral inference.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Empirical Insights

This study adopts the “Threshold Space, Transitional Space, Narrative Focus Space, and Closure Space” spatial sequence as an analytical lens to explore how spatial configuration influences visitor behavior in cultural exhibition spaces.

Drawing upon immersive eye-tracking experiments, subjective assessments, and cross-case analysis of three representative museums, a spatial–behavioral mapping model was developed. Using multiple linear regression, the study quantitatively assessed the effects of four key perceptual variables—enclosure, visual corridors, spatial scale, and light–shadow articulation—on two behavioral outcomes: interest ratings and dwell time.

In Threshold Space, both dwell time and interest were negatively correlated with enclosure, with visitor behavior primarily characterized by spontaneous exploration and swift traversal.

In Transitional Space, enclosure emerged as the strongest predictor of interest, while an increased spatial scale significantly extended dwell time. Visual corridors supported smooth transitions between dynamic and static engagement.

In Narrative Focus Space, rapid passage was dominant. Spatial scale positively influenced interest, whereas visual corridor depth primarily determined dwell duration.

In Closure Space, visitors displayed increased contemplative engagement and prolonged gaze. While light–shadow articulation negatively affected interest ratings, it—alongside spatial scale—positively contributed to extended dwell time.

These results build upon prior research on the influence of spatial geometry in shaping movement and emotional response [

1,

2], offering a more nuanced perspective: the impact of spatial attributes is highly context-dependent when embedded within sequential spatial narratives. For example, while enclosure may reduce dwell time in initiation spaces (Threshold Space), it can enhance perceptual focus and engagement in development spaces (Transitional Space). This underscores the non-linear and dynamic effects of spatial variables, in contrast to earlier studies that assessed such features in isolation or through static analytical tools like heatmaps.

Moreover, the study highlights spatial rhythm as a structuring mechanism for visitor behavior. The sequential transition from Threshold Space to Closure Space reveals a gradual shift from goal-directed navigation to immersive observation, suggesting that carefully orchestrated spatial sequencing can foster deeper and sustained engagement. This finding supports contemporary approaches in museum and experience design, where spatial narration complements curatorial content to enrich the overall visitor journey.

6.2. Practical Design Implications

The findings of this study offer evidence-based spatial strategies for curators and designers seeking to optimize visitor experience in cultural exhibition environments. Each spatial node type within the “Threshold Space, Transitional Space, Narrative Focus Space, and Closure Space” sequence requires distinct spatial articulation in response to differentiated behavioral patterns:

Threshold Space should emphasize spatial legibility and permeability. Open layouts with reduced enclosure, minimal visual clutter, and intuitive wayfinding systems can foster exploratory movement and smooth spatial entry.

Transitional Space benefit from controlled enclosure and perceptual pacing. Architectural features such as semi-transparent partitions, overhead apertures, or transitional rest zones can maintain visitor engagement while supporting gradual immersion.

In Narrative Focus Space, where orientation shifts and redirection are central, design should enhance visual anchoring and spatial modulation. This can be achieved through targeted material contrasts, spatial compression and release, or directional light–shadow articulation that guides reorientation.

Closure Space demand a heightened focus on atmospheric cohesion and contemplative depth. Expansive spatial volumes, integrated natural–artificial light–shadow articulation schemes, and acoustically modulated environments can cultivate prolonged attention and emotional resonance.

Together, these spatial design recommendations translate perceptual and behavioral insights into narrative-specific interventions. Rather than applying universal strategies, the findings encourage a sequenced spatial calibration approach, aligning design intentions with the cognitive and affective trajectories of visitors as they move from initial orientation to immersive contemplation.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Despite the theoretical contributions and empirical insights of this study, several limitations warrant acknowledgment. These limitations inform future methodological refinement and ensure the broader applicability of findings:

While the use of controlled virtual scenes ensured consistency across participants, the absence of multisensory cues (e.g., ambient noise, temperature, or tactile stimuli) may have reduced ecological validity. Such environmental simplifications may have influenced participants’ perceptual responses and decision-making behavior, potentially affecting the generalizability of spatial preference outcomes.

The relatively small and homogeneous sample constrains statistical inference and increases susceptibility to model instability. The limited variability across participant backgrounds restricts the capacity to uncover subgroup-specific behavioral patterns. Moreover, the high goodness-of-fit values observed (R² = 1.000) suggest the possibility of overfitting, especially under conditions of constrained sample variability or simplified experimental settings. To address this, five-fold cross-validation was conducted, resulting in a mean squared error (MSE) of 0.143, indicating acceptable predictive robustness. Nevertheless, caution is advised, and future work will include residual analysis and larger, more diverse samples to enhance model generalizability and reduce the risk of specification bias.

The current modeling framework focuses primarily on spatial-perceptual variables (e.g., enclosure, scale, directionality) while omitting potentially important individual-level characteristics—such as age, gender, architectural familiarity, or cognitive styles—that may shape spatial behavior. The absence of these control variables may have introduced unobserved heterogeneity and limited the model’s explanatory depth. Future studies should incorporate user profiling data to allow for subgroup-specific analysis and the development of personalized spatial strategies.

Although both qualitative and quantitative data were collected, their integration was not based on a formal weighting or fusion methodology. This may have limited the analytical synergy between spatial metrics and subjective impressions. Further development of multi-modal integration frameworks—potentially combining behavioral data, survey inputs, and biometric measures—would improve interpretability and design applicability.

To address these limitations, several avenues are recommended. Enhancing ecological validity through immersive and multisensory virtual environments will allow for more realistic spatial experience assessment. Broadening the sample size and participant diversity will support statistical robustness and uncover latent behavioral typologies. Methodologically, the adoption of cross-validation, residual diagnostics, and control variable inclusion can ensure model parsimony and generalizability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.C., W.P. and J.C.; methodology, X.C. and J.C.; software, X.C. and G.F.; validation, X.C. and J.C.; formal analysis, X.C.; investigation, X.C., J.C. and G.F.; resources, Z.L.; data curation, X.C. and G.F.; writing—original draft preparation, X.C. and J.C.; writing—review and editing, X.C. and J.C.; visualization, X.C.; supervision, X.C. and W.P.; project administration, X.C. and W.P.; funding acquisition, W.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Xi’an Social Science Planning Fund Project “Research on the Dynamic Inheritance and Innovative Utilization of Folk Cultural Spaces along the Qin ling Mountain Range” (Grant No. 24QL46), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities Project “Research on Hierarchical Protection and Micro-Intervention Methods for Historic Districts Based on Cultural Power Stratification Analysis” (Grant No. 300102410101).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984.

- Psarra, S. Museum layout, movement and meaning. In Proceedings of the 1st International Space Syntax Symposium; University College London: London, UK, 2001.

- Bianconi, F.; Filippucci, M.; Felicini, N. Immersive Wayfinding: Virtual Reconstruction and Eye-Tracking for Orientation Studies inside Complex Architecture. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2019, XLII-2/W9, 143–150.

- Tural, A.; Tural, E. Exploring Sense of Spaciousness in Interior Settings: Screen-Based Assessments with Eye Tracking, and Virtual Reality Evaluations. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1473520.

- Borghini, E.; Coscia, C.; Valentini, V.; Moccia, A.; Baglivo, G. Digital Twins and Enabling Technologies in Museums and Cultural Heritage. Sensors 2023, 23(3), 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Huang, W.; Shen, M.; Yi, X.; Zhang, J.; Lu, S. Extending X-reality technologies to digital twin in cultural heritage risk management: A comparative evaluation from the perspective of situational awareness. Heritage Sci. 2024, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaggion, C.; Castelli, S.; Usai, D.; Artioli, G. Cultural Heritage Digital Twin: Modeling and Representing Visual and Intangible Aspects via Knowledge Representation. Soft Comput. 2024, 28, 13421–13438. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-L.; Lee, M.-F.; Chen, G.-S.; Wang, W.-J. Application of Visitor Eye Movement Information to Museum Exhibit Analysis. Sensors 2022, 14, 6932. [Google Scholar]

- Gulhan, D.; Durant, S.; Zanker, J.M. Similarity of Gaze Patterns across Physical and Virtual Versions of an Installation Artwork. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitgood, S. An Attention–Value Model of Museum Visitors. Visitor Stud. Today 2002, 5, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Popelka, S.; Vyslouzil, J. Understanding Visitor Behavior in Geographic Exhibit with Eye-Tracking. Proceedings of the 2025 Symposium on Eye Tracking Research and Applications (ETRA ‘25), ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Article No. 87, pp. 1–7.

- Raptis, G.E. Exploring Cognitive Variability in Interactive Museum Games. Heritage 2025, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Sutunyarak, C. The Impact of Immersive Technology in Museums on Visitors’ Behavioral Intention. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrell, B. Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach, 2nd ed.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van Maanen, L.; Janssen, C.; van Rijn, H. Personalization of a Virtual Museum Tour Using Eye-Gaze. Proc. CogSci 2006, pp. 2620.

- Gong, Z.; Wang, R.; Xia, G. Augmented Reality (AR) as a Tool for Engaging Museum Experience: A Case Study on Chinese Art Pieces. Digital 2022, 2(1), 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrozzino, M.; Bergamasco, M. Beyond Virtual Museums: Experiencing Immersive Virtual Reality in Real Museums. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11(4), 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitonidou, M. Simultaneously Space and Event: Bernard Tschumi’s Conception of Architecture. Arena J. Archit. Res. 2020, 5(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendell, J. May mo(u)rn: Transitional spaces in architecture and psychoanalysis — A site-writing. J. Archit. 2019, 24(2), 223–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bleeckere, S.; Gerards, S. Narrative Architecture: A Designer’s Story; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rainoldi, M.; Yu, C.-E.; Neuhofer, B. The Museum Learning Experience through the Visitors’ Eyes: An Eye-Tracking Exploration of the Physical Context. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2043. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, H.; Wen, Y.; Liu, M.; Wu, Y. Industrial Heritage Protection from the Perspective of Spatial Narrative: A Case Study of Shougang Park. Land 2025, 14, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. From Locality to Architectural Semantics. Architects 2014, (6), 4–7. In Chinese.

- Bo, L.; Abdul Rani, M.F. The Value of Current Sense of Place in Architectural Heritage Studies: A Systematic Review. Buildings 2025, 15, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Várady, G.; Zagorácz, M.B. Application of Space Syntax in the Renewal of Industrial Area Design: Case Study of Baosteel Zhanjiang Steel Co. Ltd. Pollack Periodica 2022, 17(1), 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Ono, K.; Li, L. Cognitive Insights into Museum Engagement: A Mobile Eye-Tracking Study on Visual Attention Distribution and Learning Experience. Electronics 2025, 14, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Morales, J.; Higuera-Trujillo, J.L.; Greco, A.; Guixeres, J.; Llinares, C.; Gentili, C.; Botella, C.; Alcañiz, M. Real vs. Immersive-Virtual Emotional Experience: Analysis of Psycho-Physiological Patterns in a Free Exploration of an Art Museum. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223881.

- Davis, R.A. The Feasibility of Using Virtual Reality and Eye Tracking in Research With Older Adults With and Without Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 607219.

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural Topic Modeling with Class-Based TF-IDF. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.05794.

- Banaei, M., Hatami, J., Yazdanfar, S.-A., & Gramann, K. Behavioral, physiological, and psychological responses to architectural interiors. Environment and Behavior, 2017, 49(2), 197–225.

- O’Neill, M. J. Effects of signage and floor plan configuration on wayfinding accuracy. Environment and Behavior, 1991, 23(5), 553–574.

- Juan R, Yue W, Qibo L, et al. Numerical Study of Three Ventilation Strategies in a prefabricated COVID-19 inpatient ward. Building and Environment, 2021, 188, 107467.

- Han, S. , Song, D. , Xu, L., Ye, Y., Yan, S., Shi, F.,... & Du, H. Behaviour in public open spaces: A systematic review of studies with quantitative research methods. Building and Environment, 2022, 223, 109444. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, N., Nishina, D., Sugita, S., Jiang, R., Kindaichi, S., Oishi, H., & Shimizu, A. Virtual reality space in architectural design education: Learning effect of scale feeling. Building and Environment, 2024, 248, 111060.

- Radwan, A., Mohammed, M. A. S. E., & Mahmoud, H. Architecture and Human Emotional Experience: A Framework for Studying Spatial Experiences: Egypt as a case study. JES. Journal of Engineering Sciences, 2024, 52(5), 482–497.

- Hsieh, Y.-L.; Lee, M.-F.; Chen, G.-S.; Wang, W.-J. Application of Visitor Eye Movement Information to Museum Exhibit Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6932.

- Lee, K. The interior experience of architecture: An emotional connection between space and the body. Buildings, 2022, 12(3), 326.

- Xylakis, E., Liapis, A., & Yannakakis, G. N. Affect in Spatial Navigation: A Study of Rooms. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 2024.

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y. The Characteristics of Visitor Behavior and Driving Factors in Urban Mountain Parks: A Case Study of Fuzhou, China. Land, 2022, 11(6), 835.

- Mandolesi, S.; Gambelli, D.; Naspetti, S.; Zanoli, R. Exploring Visitors’ Visual Behavior Using Eye-Tracking: The Case of the “Studiolo Del Duca”. J. Imaging, 2022, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Zou and S. Ergan. Evaluating the effectiveness of biometric sensors and their signal features for classifying human experience in virtual environments. Advanced Engineering Informatics 2021 Vol. 49 Pages 101358.

- Ktistakis, E., Skaramagkas, V., Manousos, D., Tachos, N. S., Tripoliti, E., Fotiadis, D. I., & Tsiknakis, M. COLET: A dataset for COgnitive workLoad estimation based on eye-tracking. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 2022, 224, 106989.

- Cho, Y. Rethinking eye-blink: Assessing task difficulty through physiological representation of spontaneous blinking. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2021, pp. 1–12.

- Tanasković, I., Miljković, N., Stojmenova Pečečnik, K., & Sodnik, J. Saccade Identification During Driving Simulation from Eye Tracker Data with Low-Sampling Frequency. In Conference on Information Technology and its Applications, 2023, pp. 30–39.

- Ho, M.-H.R.; Au, W.T. Scale Development for Environmental Perception of Public Space. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 596790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.R.; Melber, L.M.; Gillespie, K.L.; Lukas, K.E. The Impact of a Modern, Naturalistic Exhibit Design on Visitor Behavior: A Cross-Facility Comparison. Visitor Stud. 2012, 15(1), 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).