1. Introduction

The use of eye-tracking (ET) systems is important for architects, architecture researchers, and architecture students, as they provide an objective and detailed comprehension into how individuals perceive and visually interact with built contexts [

1]. These systems contribute to understand how people visually explore architectonic contexts, identifying which elements attract most attention or get unnoticed. Recognition which helps to assess whether design features such as circulation, lighting, or proportions are being perceived as intended, contributing to the efficiency, functionality and valorisation of architecture projects [

2].

A better understanding of how to utilize ET effectively in architectonic contexts, and how to decode ET comprehension into design knowledge, is required. Such gap is the central problem that this article seeks to address, as well as how to understand current ET limitations and advance our understanding of visual perception in architectonic contexts.

This work is the most up-to-date review of ET in architectural research until today, incorporating the latest studies through 2024 and providing a comprehensive overview that crosses technological, methodological, and pedagogical aspects. In contrast to previous reviews, we integrate findings across diverse subfields to present a unified picture of how eye-tracking is transforming architecture research and practice.

In this review, we systematically examined recent ET studies in architecture (2010-2024) to understand how this technology has advanced architectural research and practice. We focused on key application areas (design evaluation, wayfinding and education), summarize common findings, and identify limitations and future research needs. The aim of this Scoping Review (SR) is to bridge the knowledge gap in the use of ET data for design insights.

As we did not use a clearly defined research question in this SR searches, we are therefore posteriorly introducing the following PICO research question as a suggestion for the review of this SR: In architecture students, researchers, and practitioners, does the use of eye-tracking technology, compared to traditional qualitative observation methods, provide more accurate, objective, and actionable insights into pedagogic visual perception, design evaluation, and spatial navigation within built environments?

1.1. Literature Search Strategy

This SR was conducted using the knowledge from the authors of this study based in searches in the literature for a previous sketch of this review. We used [

3] research strategy, and searched for evidence, in 27 of November of 2024, in Harzing’s Publish or Perish (Windows GUI Edition), version 8.17.4863.9118.

Our inclusion criteria were:

Being published in English.

Being full articles.

Being published in relevant scientific journals or relevant conference proceedings.

Being published after 2010 and before 2024.

Mentioning “architecture” besides mentioning “eye tracking”.

The exclusion criteria were:

We did not exclude articles based on quality scoring, as our aim was to map all relevant literature; however, we note that study methodologies vary, and some limitations are discussed in this SR.

Our key term was “architecture, eye-tracking” in all searches. The review was a single-author effort during approximately 3 months, as there were not multiple reviewers.

Furthermore, the scope of the analysis was 14 (2010-2024) years. A previous classification was done based on publication date: from the 75 articles selected, we found 29 (38,66 %) articles published before 2021, 14 (18,66 %) from 2022 and 2023, and 32 (42,66 %) from 2024. The 3 Literature Reviews (LR)s were from 2022, 2023 and 2024. The oldest of all the chosen articles amongst these were from 2015 (1 article) and 2016 (1 article).

One of the LRs, from Aalto and Steinert [

4] found that only 20 experiments with ET in architecture had been conducted from 1976 until the end of 2018, even with a large variety of equipment and methods available. And that from 2019 to 2021, the field suddenly leaped forward, with 46 new experimental studies in three years.

We analyzed all abstracts of the 75 articles selected, searching for objectives, methods and results. This article theme classification method was based on checking these constituents of these articles, step by step, by the order that follows, until their theme classification offered no doubt. However, sometimes we did not have to go through all the checking steps:

Title.

Abstract, highlights and article aim.

Concept(s) highlighted in the article (when existent).

Research question(s) (when existent).

Conclusion.

Main article.

Images, graphic(s) and table(s).

As referred, the different themes classified were suggested by the articles themselves, as there was no apriorist idea for the classification items. In the end, we organized the main theme and subthemes by alphabetic order. We identified 13 main thematic categories of applications of ET in architecture, which included this article focus: architectural education and end-user experience. We also decided to include Vartanian et al. [

5] due to its relevance to this SR.

And as a possible Boolean keywords string for this literature search, we are posteriorly suggesting:

(“architect*” OR “architecture student*” OR “design professional*” OR “built environment researcher*”)

And

(“eye-tracking” OR “eye tracking” OR “eye movement” OR “visual attention” OR “gaze tracking”)

And

(“visual perception” OR “spatial navigation” OR “wayfinding” OR “design evaluation” OR “user experience” OR “architectural education” OR “design analysis”).

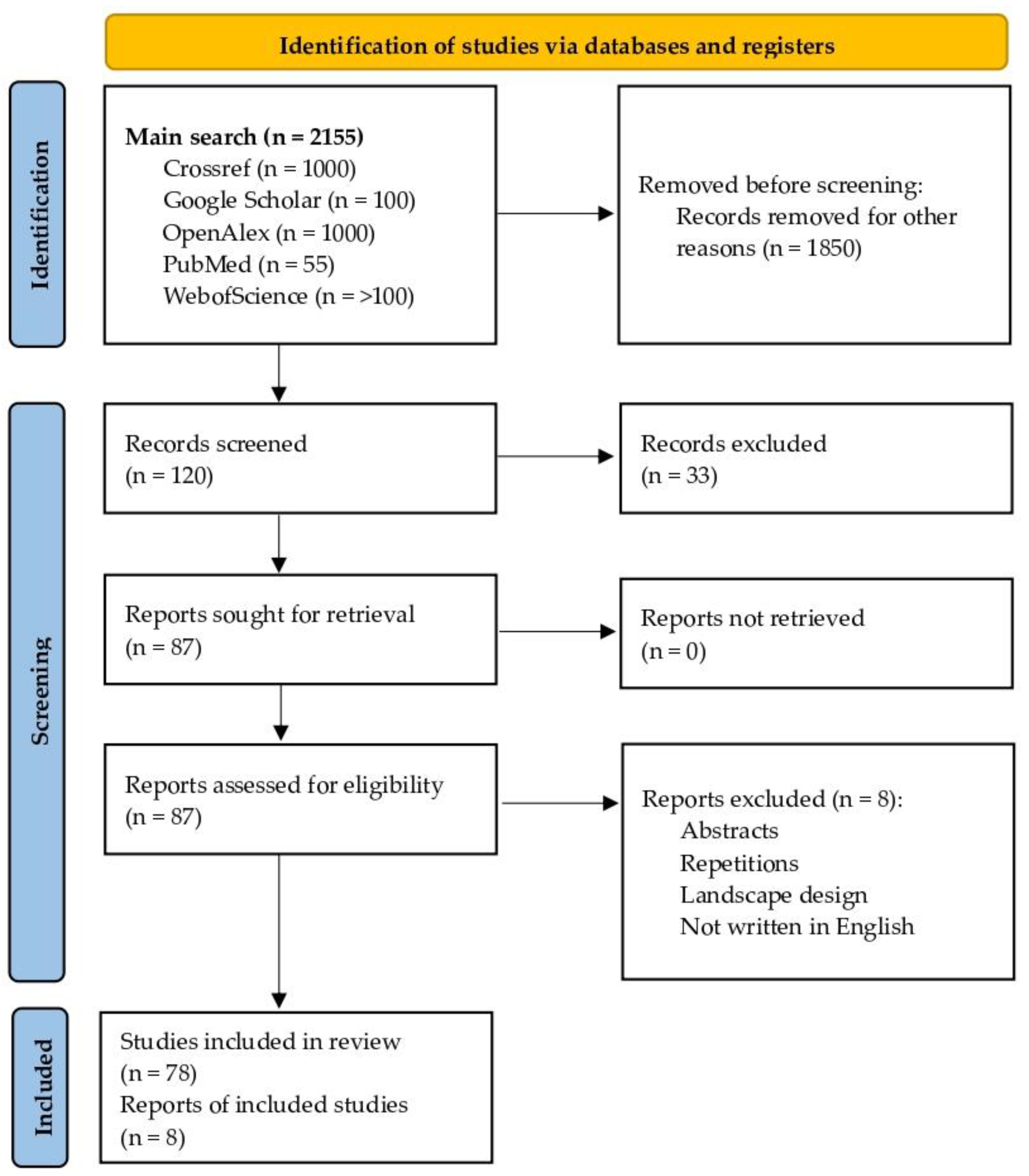

This scoping review was conducted with reference to the PRISMA-ScR guidelines. A PRISMA flow diagram of study selection is provided in

Figure 1, and the PRISMA-ScR checklist is available as Supplement.

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) has been used in this paper to generate text, graphics, to assist in study design, in the analysis, and interpretation.

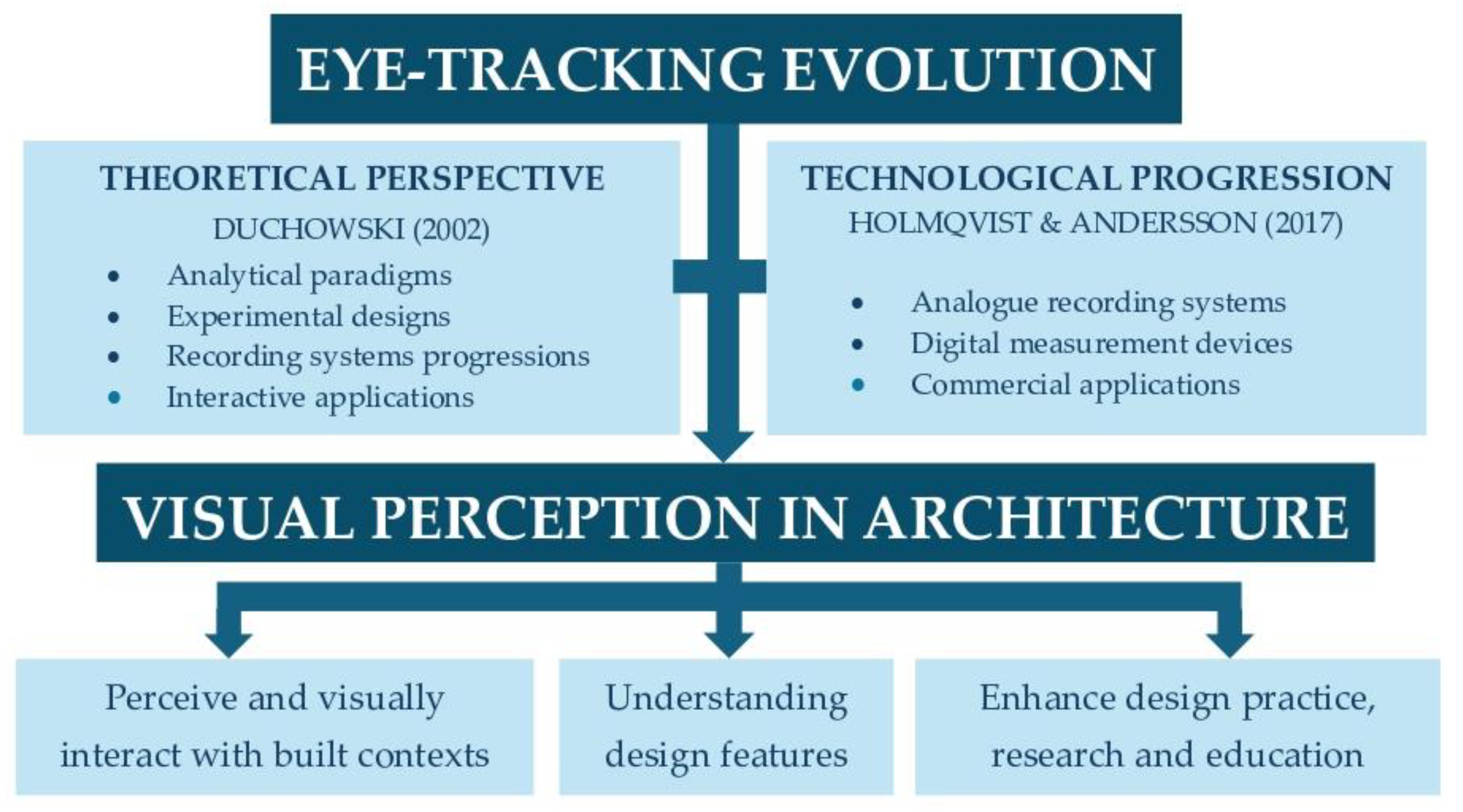

As shown in

Figure 2, we start this article by presenting a short ET history. This way of starting allows us to first have a general view of this technology functionality as a tool to perceive our exterior environment.

1.2. Eye-Tracking Evolution

ET concerns

where,

what and

how we are looking when focusing on a determined visual

stimulus. The focal points can be a painting, a photography, a sculpture, or, as already mentioned, an architectonic context. Hence, ET might allow us to glimpse how individuals visually engage with art. Moreover, since the early nineties, when ET has become more widely accessible, this tool has generated great interest in the user experience field (UX) [

6].

Around 2002, according to Duchowski, ET was arriving to its fourth era with the emergence of interactive applications. The first three eras were clearly summarized by Rayner [

7] and cited by Duchowski [

8]. The first era starting in 1879 (until 1920), when the French ophthalmologist Louis Émile Javal observed the eye movement during silent reading, creating the term

saccade. By then, many basic facts about eye movement were discovered. Basic facts, such as

saccade suppression (blindness during a saccade),

saccade latency (time spent to plan and execute a saccade), and the measure of our amplitude of vision. The second era coincided with the behaviorist movement in experimental psychology, and had a more applied focus, with less research on theory about the eye movement. Finally, the third era, which began in mid-1970s, was marked by progresses in the eye movement recording systems.

On the other hand, more concerned with ET hardware, according to Holmqvist and Andersson [

2], during a first era, Javal, Delabarre, Dodge, Buswell, and Yarbus, and others, built mechanical and optical hardware, recording analogue data which was analyzed by hand. In a second era beginning in the 1970s, researchers built electrical hardware, and computer software, for recording and analyzing analogue and digital data. Finally, in 2017 we were still in a third era. By then, eye trackers had become a commercial product, sold or lend to researchers, who could use prepackaged software from manufacturers, easily recording and processing data more easily.

Notably, Duchowski [

8] and Holmqvist and Andersson [

2] had different understandings on ET history periods. Duchowski [

8] adopts a methodological scrutiny, classifying historical phases predominantly by the analytical and research paradigms that emerged in the different phases. Rather than focusing strictly on hardware, this author highlights shifting theoretical perspectives and experimental designs. In contrast, Holmqvist and Andersson [

2] overview of ET history emphasizes the technological progression of recording and measuring ocular movement, segmenting developments based on significant turns in ET equipment. However, these two authors, place particular focus on how hardware progresses, from rudimentary mechanical devices to modern video-based systems, shaped the evolution of this field. Holmqvist and Andersson [

2] view the time periods through the ability of the technology to capture increasingly precise eye movement data. While, Duchowski [

8] defines similar historical periods with a prism of the methodologies and theoretical frameworks that arose sometimes in response to technological advances.

Some authors [

1,

2,

9], refer that the main method used today for capture gaze movements, possibly the most widely applied ET technique, is video-based corneal reflection. The first use of this method dates to 1901 [

10]. In the 1950s were developed techniques using contact lenses, using attached devices like small mirrors and coils of wire. Subsequently, very complete data was collected with measurement devices relying on physical contact with the eyeball. However, these late systems were very intrusive. The video-based corneal reflection systems are accurate and reliable, non-intrusive, and are now commercially available.

After this quick draft of of ET history, it seems important to focus on what ET is studying supported on the Human Visual System (HVS). Specifically, the neurology which supports our gaze and this gaze behavior.

1.3. Human Visual System

According to Holmqvist and Andersson [

2], the human eye lets light enter through the pupil. This eye turns an exterior image upside down and projects it onto the anterior face of the eyeball, the retina. The retina is covered with light sensitive cells, named cones and rods. These cells transform light into electrical signals, which are sent through the optic nerve to the visual cortex in the brain. While cones are sensitive to visual detail and provide color vision, rods support vision under dim lighting conditions. In the retina, we find a small area called

fovea. The fovea encompasses less than 2º of the visual field, and we only have high-acuity vision in this short angle. To see a selected object sharply, we must move our eyes. This foveal information is prioritized when processed to the brain.

Still, according to Holmqvist and Andersson [

2], the most common event reported through ET does not relate to a movement, but a state when the eye remains immobile over a period. It is called

fixation and lasts approximately, between about tens of milliseconds (

ms) up to several seconds. However, in this position, the eye is not completely stopped but it moves. These movements are called

tremor,

microsaccades, and

drifts [

2,

11].

These same authors, Holmqvist and Andersson [

2], refer that tremor is a small movement, which the exact role is unclear, and it can often be due to imprecise muscle control. Drifts are a slow movement which take the eye from its focus, and microsaccades compensate these drifts by quickly bringing the eye back to its original position.

Finally, Holmqvist and Andersson [

2] mention that the quick eye motion from one fixation to another is called

saccade. Saccades are very fast and take typically 30-80

ms to complete. Moreover, many eye movement paradigms assume that we are blind during most of the saccade. Saccades rarely take the shortest path between two points but can undergo one or several shapes and curvatures. Mostly, saccades do not stop directly at the intended target but continue to wobble a little before coming to stop.

Next, are presented the main types of eye-trackers reported in 2017 by Duchowski and Holmqvist and Andersson. These devices were mainly distributed by mobile and static eye trackers.

1.4. Types of Eye-Trackers

According to Duchowski, the ET systems available in 2017 were primarily head-mounted or table-mounted. Head-mounted devices were often integrated into portable glasses, allowing greater mobility for conducting experiments outside in controlled contexts. Table-mounted devices, were usually affixed to a computer screen, being better suited for static, laboratory-based studies. Holmqvist and Andersson [

2] also categorize these systems by identifying eye-mounted eye-trackers, head-mounted eye-trackers, tower-mounted eye-trackers, and remote eye-trackers, which collectively illustrate the diverse technological approaches researchers employ to capture visual attention data.

Although, according to Holmqvist and Andersson [

2], mounting an eye-tracker on to participant eyes can present several problems, it still offers the possibility of high-quality data. Hence, head-mounted eye-trackers place active parts on the head of the participant, on a helmet, cap, or a pair of glasses. Simultaneously, a scene camera records the stimulus. These head-mounted eye-trackers, allow the participant the maximum mobility, especially if the recording computer is small and lightweight. However, it is important to remark that the camera angle towards the eye can, in principle, be shifted and adapted to the individual participant and specific task. In addition, we can find other human interfaces such as fMRI eye-trackers and even primate eye-trackers. These last interfaces, and virtual reality (VR) eye-trackers, are all versions of mobile eye-trackers, and the stimulus display is fixed in relation to the camera and the head of the participant. However, 3D objects are not fixed, and in the data, there will be a variable level of vergence due to depth, nevertheless there will take simultaneously place a constant level of accommodation.

After this presentation of ET history, HVS and types of eye-trackers, we are introducing architecture by understanding the importance of studying the human visual perception in architecture. And, how this can help architects, researchers and students of architecture in an innovative way, bringing new contributions to projects, research and learning.

1.5. The Importance of Studying Visual Perception in Architecture

There are several architectural features which influence the way we experience architectonic contexts. Therefore, how we visually perceive architecture, is imperative either to find our way throughout these architectonic contexts or to find its beauty.

Amongst several authors, namely the founding study by Ulrich [

12], cited by Wiener and Franz [

12], contextual characteristics of architecture influence subjective experience. Therefore, several theories explain human behavior and experience by the interdependency of individuals with the environment.

One author, O’Neill [

14], demonstrated that wayfinding performance decreased with increasing plan complexity. In 2015, a few theories and empirical studies had already aimed at analyzing this interdependency thoroughly, namely in an objective way using ET. However, researchers made use of qualitative descriptions of a few selected spatial situations.

Other authors argue that certain architectural elements like ceiling height have strong effect on individuals [

5]. Also, according to this author, the perceived degree of movement freedom through an architectonic context, i.e., perceived enclosure, can have impact on beauty judgments concerning architecture, together with decisions to enter or exit those contexts. Vartanian cites Appleton [

15] to refer that an architectonic context judgment as aesthetically pleasing results of its inclusion of certain characteristics (e.g., shapes, colors, spatial arrangements) suggesting that it is a context favorable to survival. Namely, “to see without being seen” and “to be not seen”. Regardless this survivability being somewhat accurate or not.

Now that we are aware of the importance of studying visual perception in architecture, we will check the history and future perspectives of ET use in architecture. These usages of ET in architecture are still developing, as we will understand, and ET is being increasingly applied in architecture, mainly by academic researchers. However, these usages should be extended to architects and students, as proposed by several scholars.

1.6. Eye-Tracking Architectural Applications, History and Future Perspectives

The pioneers of ET applications to architecture are both [

16,

17]. According to Aalto and Steinert [

4], Buswell [

16] included images of architecture in his pioneering study and Yarbus [

16], published the earliest guide to ET research. Both these studies inspired Janssens [

18], to publish “an exceptional thorough study that combines ET with verbal descriptions and semantic ratings to examine the pleasantness and ease of identification of 10 types of Swedish building exteriors” [

4]. According to these last authors, this work [

18] might be the first use of ET in architecture. This same author, Janssens [

19], has noted that architects and non-architects might see the world differently, but, as Aalto and Steinert [

4] suggests, this author most important contribution might be highlighting the relevance of ET for architectural research.

Also, according to Aalto and Steinert [

4], some researchers, Weber et al. [

20], suggested that objects were seen differently than mere contours. Later, other authors, Foulsham et al. [

21], indicated that a controlled laboratorial experiment could provide more significant quantifiable results about architecture than interviews or surveys. Which was important for a better understanding of the individual factors affecting experimental results.

Aalto and Steinert [

4] refer that until 2021, ET had been used in architecture in multiple ways, such as remembering visual experience [

22], visual preference [

23], viewing objects and elements [

24], architectural experience [

25], creative performance [

26], validity in building heritage and degradation [

27,

28], design process [

29], triangulation [

30] and education [

28].

Finally, Aalto and Steinert [

4], recommended for future research in ET analyzing architecture:

Use of VR to systematically verify designs in development, to ensure that users gaze patterns match what we want to be read in a context.

Develop ET methodology, methods, and triangulation to deal with in situ experiments complexity.

Further develop best practices for laboratory-based experiments.

Use replication, and verification studies, on analysis of gaze differences between architects and non-architects, on the relationship between gaze patterns and preferences, and on the role of individual building elements in attracting gaze.

Developing further new and rapid approaches such as visual attention software (VAS).

We conclude this introduction, having shortly reviewed the history of ET architectural applications and mentioned future perspectives for this field. In the next chapter, we will broaden our knowledge about the ET role in understanding architecture.

Figure 3.

Conceptual model of the themes in “Understanding eye-tracking in architecture” (

Section 2). This diagram summarizes the technical and theoretical concepts (definition, fixations/saccades, advantages, limitations) introduced before delving into applications. (Source: authors).

Figure 3.

Conceptual model of the themes in “Understanding eye-tracking in architecture” (

Section 2). This diagram summarizes the technical and theoretical concepts (definition, fixations/saccades, advantages, limitations) introduced before delving into applications. (Source: authors).

2. Understanding Eye-Tracking in Architecture

2.1. Use and Technical Principles

In architectural research, the different types of ET hardware enable architects, researchers and students of architecture to study how individuals visually engage with physical or virtual designs. Thus, revealing how building users perceive space, respond to environmental cues, and navigate complex structures [

31,

32,

33]. By selecting the ET system that fits the required mobility and experimental control, either a head-mounted system for in-situ observations by pedestrians inside a building, or a table-mounted system for assessing the gaze patterns of users on digital architectural renderings, researchers can produce targeted insights to inform user-centered design strategies or improve spatial experiences.

After referring how ET can help architectural research, outlining some ET technical principles in architecture, we will refer and define eye movement concerning architectural research. We will go through Henderson and Hollingworth [

34] exploration of scenes, view and perception, relating these ways of seeing scenes to architectonic contexts viewing.

2.2. Fixations, Saccades, and Scan Paths in Architecture

According to Henderson and Hollingworth [

34], in research,

scene is typically defined as a view of a real-world context comprising “background elements and multiple discrete objects arranged in a spatially licensed manner. Background elements are taken to be larger-scale, immovable surfaces and structures, such as ground, walls, floors, and mountains, whereas objects are smaller-scale discrete entities that are manipulable (e.g., can be moved) within a scene.” The distinction between a scene and an object is dependent of the spatial scale. However, as it might be difficult to determine the approximate scale of a scene, so most researchers of scene perception have just scaled their scenes to human scale. Henderson and Hollingworth [

34], have also done the same.

According to these authors, there are three levels of seeing when we first perceive a scene: low-level or early vision, intermediate-level, and high-level. In low-level, we extract the physical properties, depth, color, and texture, and generate representations of surfaces and edges [

35]. On intermediate level, we extract shape and determine spatial relations [

36]. Finally, in high-level vision, we map from visual representations to meaning, which is followed by an active acquisition of information, that is stored in short-term memory, and the identification of objects and scenes. We will analyze this last level of seeing based on Henderson and Hollingworth [

34].

During eye movement in scene perception, these authors concluded that, during scene viewing, fixation positions are non-random, with visually and semantically informative regions clustering these gaze positions. This attraction based on meaning is not immediate, but if these regions which are spotted by our eyes they may remain there for longer time. For architecture viewing, this conclusion might imply that where our gaze lingers and comes back, might be on architectural features with most meaning in an architectonic context.

Concerning

scene representation retained across a saccade, these authors concluded that during complex, natural scene viewing, only a limited amount of information is carried across saccades. And this information is coded and stored in an abstract (nonperceptual) format. Moreover, our experience of a complete and integrated visual world results from an illusion or construction based on “an abstract conceptual representation coding general information about the scene (e.g., its category) combined with perceptual information derived from the current fixation” [

34]. For architecture viewing, this conclusion might imply that when we move our gaze through an architectonic context, we will have an abstract representation of this context based on our previous conceptual information about this scene, mingled with what we are fixating in a current moment.

Finally, concerning

object and scene identification, these authors concluded that a consistent scene facilitates the identification of objects, despite the existence of methodological problems found in the studies [

37,

38] analyzed by Henderson and Hollingworth [

34]. And that are advantages for the identification of consistent versus inconsistent objects. Recent studies did not find this advantage [

39]. The functional isolation model, which proposes that object identification is isolated from expectations derived from scene knowledge, provided the best explanation for this problem. For architecture viewing, this conclusion might imply that expectations imputed by viewing architectonic contexts, do not influence the identification of architectural features and that consistent scenes are better identified.

In the following section, we will present advantages and limitations in the use of ET in architecture. Although, the use of ET presents many advantages, there are still important challenges ahead.

2.3. Advantages and Limitations of the Use of Eye-Tracking in Architecture

Mahmoud et al. [

40], in their LR refer several advantages and disadvantages related with the use of ET in architectural research.

As advantages:

The interest in the experimental side of architectural research is increased.

A way of accurately communicating graphically and numerically the viewer visual experience is provided.

The acceptance of design orders which require in-depth analysis of the visual needs of the users is further guaranteed.

The importance of visual perception of architecture, and to get closer to its users, is highlighted.

Whereas, as disadvantages:

Maintenance and conservation of ET hardware is complex.

ET equipment is not available for public use.

ET devices are for only one user at the time.

ET tools still lacking latency and accuracy.

These authors, Mahmoud et al. [

40], reviewed five ET studies, [

24,

41,

42,

43,

44].

One year after, Zhipeng and Pesarakli [

45] reviewed 50 articles on ET and environmental research, which contained, specifically related to architecture and interior spaces: 10 studies on “examining the effects of environmental features (e.g., lighting, color, spatial arrangement, material and outdoor view) on people’s behavioral, emotional, and physiological responses”, 3 studies on “evaluating the effects of different types of stimuli (e.g., sketch, image, 3D representation and VR) on eye behaviors”, and finally, 7 studies on “assessing the influences of environmental features on people’s indoor wayfinding performance and behaviors”.

Concerning these 50 studies, Zhipeng and Pesarakli [

45] found several articles discussing the limitations of ET:

Interpretations of gaze behaviours, fixations and scan paths might not provide direct information on the subject’s brain activities (e.g., emotion, cognition and attention); found in the article by [

46].

Some limitations concerning ET glasses. “Eye-tracking became challenging when subjects had free movement, which incurred an inaccurate estimate of head direction/position and gaze direction in 3D coordinates” [

45]; found in the article by [

47].

“Data loss was a common problem for outdoor mobile eye-tracking, possibly due to bright lighting conditions and head/body movements” [

45]; found in the articles by [

48,

49].

“Inaccuracy between the captured and the actual gaze points” [

45]; found in the article by [

50].

Some studies used pupil size as indicator of emotional state. “However, the pupil size and emotional arousal relationship was complex, and the pupil size was also influenced by other factors such as cognitive processing load” [

45]; found in the articles by [

51,

52,

53,

54]. As well as factors like “light quantity and contrast” also influence the pupil size [

45]; found in the articles by [

55,

56].

Concerning data analysis, for studies using mobile ET devices, it took significant time and effort to code and analyse visual behaviours as the views of the subject constantly changed during the experiment [

45]; found in the articles by [

57,

58].

As we saw, although there seem to be many important advantages, the use of ET in architectural studies is still a major challenge. Now, we will set our attention on the role of ET in architectural research, where ET seems to perform multiple tasks: education, end-user satisfaction, wayfinding, understanding architectonic contexts features, amongst others.

Figure 4.

Conceptual model of the themes in “Role of eye-tracking in architectural research” (

Section 3). This diagram summarizes the architectural education and end-user experience concepts (design pedagogy, expert and novice gaze behavior differences, wayfinding and spatial navigation, visual hierarchy and attention distribution, orientation and the role of complexity) introduced before delving into the discussion section. (Source: authors).

Figure 4.

Conceptual model of the themes in “Role of eye-tracking in architectural research” (

Section 3). This diagram summarizes the architectural education and end-user experience concepts (design pedagogy, expert and novice gaze behavior differences, wayfinding and spatial navigation, visual hierarchy and attention distribution, orientation and the role of complexity) introduced before delving into the discussion section. (Source: authors).

3. Role of Eye-Tracking in Architectural Education and Research

3.1. Eye-Tracking Applications in Architecture Design Pedagogy

After four years of cooperation and research, Rusnak and Rabiega [

28] published an article concluding that they are certain of the importance of ET for architects and the future education of urban planners. And they highlight that ET makes possible to record what attracts or distracts the attention of the users of specific spaces, as well as how elements defining squares, streets and passages are perceived by people, improving orientation in the city and inside buildings. Moreover, ET makes possible to verify architectural projects expectations and promote the self-improvement and self-development of students and teachers. And, concluding, to help them to gain knowledge in experimental research.

Rusnak and Rabiega [

28], enumerated several strong points for introducing ET in the curricula of architecture learning:

An inventive technique to guide the attention of future architects to the topic of order in architecture and urban planning, broadening their knowledge on the perception of architecture, i.e., how to design attracting the gaze of the users of architecture, while at the same time appropriately inscribing the project of someone in the natural or historical context.

Increase the interest of students in the experimental side of research in architecture, which may lead to solve architectural projects with more creativity.

Broaden the social and technological skills of the students, which may facilitate their future acceptance of non-standard and complex architectural project orders, that require in-depth analysis of the visual requirements of the users, as well as interdisciplinary cooperation.

Self-monitor both teachers and students.

Influence in a positive way student-teacher personal working relationship, which may facilitate the following to advanced studies, e.g., master or doctorate.

Promote the academic institution, distinguishing it from other research centres, both by these advanced technological solutions and by adjusting learning requirements to real needs of the users.

Educate the architectural public interesting them in the buildings they see day-to-day and promote the profession of architects.

Nevertheless, Rusnak and Rabiega [

28] found a few problems to this:

High cost of ET use (if we purchase it), maintenance, and conservation, as well as its insurance.

Necessity of a room for the experiences, which should be able to receive about 12 persons, and, depending on the experience characteristics, it can be necessary to prepare a laboratory.

Teachers may contest the legitimate use of ET for self-analysis, as it requires adding work hours and extra effort as well as an open-minded and self-critical approach.

Classes need to be in-person to manipulate ET, which would be impossible in exceptional conditions like COVID.

Rusnak and Rabiega [

28], emphasized that these advantages and disadvantages required to be checked. Moreover, that the literature about the use of ET in other fields seems to confirm the usefulness of ET in architecture education.

After seeing advantages and disadvantages of using ET in architecture classes, we will see how these devices allow us to have a more precise idea of what is an expert and novice gaze in architecture. How ET behaves differently in these two types of conditions. Further outlining its impact on architectural education.

3.2. Differentiating Expert and Novice Gaze Behavior in Architectural Education

While we can quite easily assume that a teacher and a student look at architecture in a different way, ET might allow us to identify where, what and how does each of them looks when they appreciate an architectonic context. And we also may want to know in which sense this difference might be pedagogic.

In their article about differences between expert and non-expert gaze, Jam et al. [

59] refer that there are in the literature numerous studies exploring these perceptual differences in architecture and urbanism [

60,

61,

62,

63].

These authors, Jam et al. [

59], investigated “the impact of expertise on preference, visual exploration, and cognitive load experienced during the aesthetic judgment of facades” in Theeran. For this purpose, they used a psychophysical paradigm and ET and to distinguish between expert and non-expert in architecture, and they tested four hypotheses.

Jam et al. [

59] found significant differences in how experts versus non-experts viewed facades. As experts had longer fixations and saccades and paid more attention to context and structure, whereas non-experts had more fixations on decorative elements and shorter scan paths. They also noted that experts showed signs of higher cognitive load, suggesting deeper processing.

This investigation Jam et al. [

59], concludes by referring that the analyzed visual aesthetic evaluation of the façades could by influenced by the physical elements and attributes of the facades, and a personal cognitive variable such as expertise. And recommends further investigation in this field, namely using ET.

We believe that students of architecture are also non-experts in architecture, but with a higher level of expertise than the individuals participating in this study by Jam et al. [

62]. It would be expectable that through ET we may find also different ways of viewing architecture between teachers and students of architecture. Consequently, this tool might be valuable to teach architecture, guiding students to expert ways of seeing architecture.

In the next section, we will see how it is possible and advisable to use ET to improve wayfinding through architectonic contexts. Consequently, user-end experience of architecture contexts, may be a means of using ET for enhancing our architectural projects.

3.3. Evaluating Wayfinding and Spatial Navigation in Architectural Research

ET can operate as a robust tool for understanding how people navigate and orient themselves within architectonic contexts, offering valuable data about the gaze of users and attentional priorities during wayfinding tasks [

13]. By correlating ET metrics, such as fixation density and saccadic patterns, with architectural features, researchers can reveal which environmental elements users rely on when creating mental representations of the layout of a building. For instance, individuals might repeatedly fixate on “anchor points” or salient features like doorways, windows, or signage, which facilitate orientation and route selection [

13].

According to Sun, Li, Lin and Hu [

31], who studied airport wayfinding, architectural facilities for transportation are important in wayfinding research. In these buildings visitors have a clear wayfinding purpose. Therefore, to improve wayfiding efficiency is crucial a perfected signage system. In railway stations, wayfinding is also very important, Zeng, Zhang and Zhang [

32] found that “connectivity and visual field area of wayfinding nodes have strong positive correlation with passengers”.

Wayfinding is a process from environmental perception to decision-making. And, through ET, the specific causes of a wrong wayfinding decison can be rigorously find and analyzed [

31]. Current research on architectural wayfinding uses a variety of representation methods: the field reality scene, VR three-dimensional model, panoramic photographs, etc. Moreover, research objectives have roughly two aspects: guide signs and space pattern [

32].

Whereas, according to Wu, Chen, Zhao and Xue [

64], wayfinding is a continuous process envolving perception, decision-making, and execution. And wayfinding studies normally choose to employ field reality scene or VR methods.

Wayfinding in architectonic and urban contexts is therefore an important field for ET use, being this technology crucial for implementation of good practices. In the following section, we will analyze the attention of the viewer and perceptual hierarchy when exploring interior spaces, mainly using a study by Vartanian et al. [

5].

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

3.4. Analyzing Visual Hierarchy and Attention Distribution in Interior Spaces in End-User Experience Research

Vartanian et al. [

5] academic article about ET provides valuable insights concerning how specific architectural features, such as ceiling height or enclosure, can condition the attention of the viewer. This study was also concerned on perceptual hierarchy when exploring interior spaces. By recording fixations and saccadic movement, researchers can pinpoint which elements, like high or low ceilings, open corridors, or enclosed corners, attract immediate attention. Vartanian et al. [

5] verified that the judgments of people on beauty and comfort are closely tied to the spatial arrangement they face, highlighting that ceiling height and enclosure levels serve as major cues during the scanning of the viewers of an architectonic context.

Moreover, visual hierarchy revealed through ET often shows that individuals assign more time to areas they find crucial for orientation, doorways, functional furnishings, or lighting sources, and to features that make a room feel expansive or constricted [

5]. In open, airy rooms with higher ceilings, participants typically exhibit fewer re-checks or back-and-forth saccades to reassure themselves of the spatial dimensions. By contrast, more enclosed or lower-ceilinged designs provoke longer and more frequent fixations on potential congested areas, presumably due to higher perceived complexity [

5].

Together, these patterns show how the interaction of enclosure and ceiling height, influences the attentional distribution and comfort levels of the users. Finally, architects can use these ET insights to conceive interior architectonic contexts with effective direct visual interest, reinforce intended pathways, and promote a sense of aesthetic harmony [

5].

After analyzing the use of ET for interior features of architectonic contexts, in the next sections, we are going to discuss and conclude this study findings.

4. Discussion

This study findings underscore that ET has become a powerful lens for understanding visual perception in architecture, revealing how people explore, and experience, architectonic contexts. Over the past decades, advances in ET technology and methodology have made it possible to gather precise, real-time data on where viewers focus in architectonic contexts [

1].

As a result, researchers can now objectively document attention patterns in spaces ranging from buildings and streets to interior rooms. Indeed, the application of ET in architectural research has rose recently, Aalto and Steinert [

4] report that after only approximately 20 studies from 1976 to 2018, there were 46 new ET-based experiments in architecture between 2019 and 2021. This growing body of work also reveal the value of ET in connecting design intent and actual user experience.

By capturing how elements like lighting, layout, or forms attract (or fail to attract) attention, ET provides evidence-based insights that enrich our understanding of the HVS in context. It confirms, for example, that observers do not passively see a space all at once; rather, vision is an active process of selection of the environment, guided by both the physical features present and the goals and expectations of the viewers [

34]. In architectonic scenes, this might mean that people tend to sequentially focus on spatial cues that help them make sense of the environment, a process that ET can elucidate in detail.

One prominent theme, that emerged in this study, is the difference of gaze behavior between experts (e.g., trained architects) and novices when observing architecture. This SR and analysis build on previous research, finding that expertise significantly shapes visual scanning patterns. Jam et al. [

59], showed that architects tend to have larger and more structured scan paths when evaluating building façades, whereas non-architects tend to fixate more on immediate, decorative details. In this authors study, experts more frequently scrutinized contextual and structural elements of façades (overall form or integration with surroundings), and showed fewer fixations on ornamental features, compared to novices. This might suggest that with training, architects develop schemas or expectations that guide their eyes efficiently toward functionally or compositionally relevant aspects of a design, rather than getting distracted by surface ornamentation. Experts were also perceived to be “more active and attentive” in their viewing, indicating they cover a scene with purposeful eye movement to extract information. Such discrepancies in visual strategy are not merely academic matter, they convey important implications for how we teach and practice design.

In education, making students aware of these expert–novice differences can be very instructive. If novice students can learn where to look, for instance, to pay more attention to contextual cues or spatial organization, as experts do, they may improve their ability to evaluate and create designs. ET can facilitate this pedagogical goal by providing immediate, objective feedback. As, during a critique a teacher might use ET to show a student which key features of a building they overlooked, or conversely how a gaze of an expert lingered on areas the student underappreciated. In fact, scholars have begun to argue that ET is a valuable tool in design studios to “guide the attention of future architects” towards more expert-like observation patterns. Rusnak and Rabiega [

28] stress that incorporating ET into architecture curricula can broaden the understanding of the students on how designs are perceived, enhance their appreciation of user experience, and even promote greater self-reflection in both students and teachers.

However, benefits for education come with practical limitations. As Rusnak and Rabiega [

28] remark, high equipment costs, and the requirement for dedicated laboratorial space or hardware can pose challenges to schools. Additionally, teachers must be trained to interpret ET data and integrate it meaningfully into design critique process. Despite these difficulties, the consensus emerging from the literature is that the pedagogical return of ET, in promoting evidence-based design learning and cherishing more attentive, user-conscious architects, is significant.

Another central contribution of ET research to architecture is user-centered design practice, particularly in areas like spatial navigation, wayfinding, and interior layout optimization. ET offers an extraordinary insight into how people navigate through spaces, and which features they rely for orientation. By analyzing users gaze paths and fixation clusters, architects can identify environmental elements that attract attention and operate as cognitive “anchor points”. Studies in complex public buildings have found that users naturally fixate on doors, signage, and distinctive markers to orientate themselves. If an expected cue (a directional sign) is constantly missed in gaze data, it might be a clear suggestion that the design or placement of this element is inadequate.

Some empirical research also stresses this matter, in an airport wayfinding study, Sun et al. [

31] used ET to show that efficient navigation is sustained in well-designed signage system, as the eyes of the participants were attracted to signs at decision points. Similarly, Zeng et al. [

32] found in a railway station context that the “connectivity and visual field area” of key wayfinding nodes (e.g., junctions, exits) had a strong positive correlation with how easily passengers found their way.

Besides wayfinding, ET research into interior space perception shows how design influences both attention and emotional responses. Notably, Vartanian et al. [

5] demonstrated that ceiling height and enclosure affect not just aesthetic judgments based on gaze behavior and approach/avoidance decisions. Participants in more open, high-ceiling rooms exhibited more relaxed viewing patterns, fewer back-and-forth fixations and less visual checking of the environment, and they were more inclined to classify such spaces as beautiful and inviting. In contrast, low-ceiling or more enclosed rooms elicited denser fixation patterns (people visually “searched” the space more thoroughly) and were more frequently related with the desire to exit the space. For architects, this implies, that subtle design choices, which change how space is visually perceived (spacious vs. confined, open views vs. obstructed views) can be objectively correlated with user comfort and behavior.

Finally, the advantages of ET for insights being clear, our discussion also brings to light the methodological and technological limitations. Firstly, there is a probability of bias in interpretation, ET records where someone looks, but not why. The same gaze pattern can have multiple explanations, and only ET cannot distinguish between, a prolonged fascinated gaze and another driven by confusion or discomfort. As Zhipeng and Pesarakli [

45] emphasize in their review, metrics like fixations and scan paths “might not provide direct information” about a viewer’s underlying cognitive or emotional state. In research, this might mean that while we can detect that a participant stared for 5 seconds at a particular painting or facade detail, we need complementary methods (such as interviews, think-aloud protocols, or physiological measures) to ascertain whether that gaze indicates aesthetic appreciation, puzzlement, or other. Without such context, there is a risk of misinterpreting the data.

Other limitations concern hardware and data collection constraints. Modern eye trackers have evolved substantially from the difficult setups of the past, becoming relatively non-intrusive and user-friendly, yet they still have fragilities. Mobile head-mounted eye trackers (ET glasses) introduce complexity, when users have free movement in a real environment. Even a small head movement can introduce mistake in mapping gaze to 3D space, leading to reduced accuracy in determining exactly what object was viewed.

As multiple studies have reported, outdoor usage adds further difficulty, bright lighting and wide head motions often cause data loss or tracking dropouts. In our study context, if an architect would use ET glasses to study how people explore an urban plaza, he might encounter segments of missing data whenever a user quickly turns their head or walks under direct sunlight, potentially leaving gaps in the visual record. Additionally, calibration drift over time can mean that the gaze point recorded might be slightly offset from the true gaze, requiring careful post-validation.

Even in controlled settings, current commercial eye trackers still have finite selection rates and precision. Mahmoud et al. [

40] note that ET tools of today “still [lack] latency and accuracy” to some degree. This can be critical when analyzing fast eye movement or very small details. A slight timing lag or positional error might cloud the analysis of whether a brief glance fell on a particular sign or just next to it.

Another practical limitation is that ET systems just record one person at a time, which makes large-group studies or collaborative scenario tracking impossible. In research, we might be interested in social dynamics (e.g., how people in a crowd collectively attend to a public art piece or how two people talking in a space look around). High costs and setup requirements further constrain widespread usage, setting up an ET laboratory for architecture may require significant investment in equipment and space, which not all firms or schools can afford.

Despite these challenges, it is important to recognize that different types of ET setups offer a spectrum of options, and selecting the right setup can mitigate some limitations depending on the research or design question. A steady, screen-based eye tracker (often mounted below a computer monitor) outshines in studios where we utilize images, plans, or VR scenes on a screen under controlled lighting. Such systems usually possess high precision and stability, making them ideal for pinpointing minute gaze differences when comparing design alternatives or evaluating visual attention on drawings. However, they inherently restrict the movement of the participants and field of view, thus sacrificing realism. As, a person viewing a building on a monitor may not behave exactly as they would in situ. On the other hand, head-mounted mobile eye trackers allow users to walk through real or mock-up architectonic contexts, providing rich data on how attention evolves naturally in space, but at the cost of lower spatial accuracy and more complex data processing. Our review noticed that analyzing data from mobile ET can be labor-intensive, as a scene is continuously changing, and each fixation must be mapped to a dynamic reference frame. Still, for studies of wayfinding or immersive experience, the mobile approach is the best of options.

An emerging middle ground is the use of VR headsets with incorporated ET. This system can immerse participants in a full-scale 3D simulation while recording their gaze, combining some benefits of real-world immersion with the experimental control of a laboratory. In VR, we can modify design variables (lighting, materials, signage placement, etc.) on the moment and immediately see how those changes affect visual attention, something impossible to do in a real building. Early research shows that VR-based ET offers insights comparable to real environment studies for certain tasks (wayfinding), though we must be cautious about differences in depth perception and user interface distractions in VR.

Overall, the choice of ET system should correspond to research goals, if the priority is ecological validity and understanding natural behavior, mobile or VR systems are better despite their data noise. If the aim is detailed analysis of visual preferences or comparisons of design details, steady desktop trackers may be more appropriate.

Recognizing these compensations is part of the current methodological discourse in ET studies. Crucially, as technology improves, we anticipate that many of these limitations will diminish, next-generation eye trackers promise higher accuracy, better outdoor performance, and multi-user capabilities, which will further solidify the role of ET in research and practice.

4.1. Challenges and Gaps

In this chapter we will provide a critical evaluation of the state of the research by pointing out if some of the previous analyzed study results are contradictory or if certain topics have been understudied.

Henderson and Hollingworth’s [

34] article remain today a high-quality, self-critical survey that maps the theoretical field while clearly exposing weak spots in the empirical basis. Its main limitations stem from the irregular quality of primary literature they had to review and not from the reviewing process itself. The internal contradictions they expose are not a fault from the study but a precious indication of where the field needed, and in many cases still needs, better experiments.

Rusnak and Rabiega [

28] offer a large scope vision of how ET could enrich architectural education. The strength of the article lays in its conceptual synthesis and straightforward inventory of practical difficulties. Its weaknesses stem from the lack of systematic empirical data and several self-contradictory claims about what ET can, and cannot, deliver. It is an inspirational paper which now requires rigorous follow-up experiments.

Jam et al. [

59], advance façade research by intertwine architectural theory with modern ET metrics and a ingenious layer-based coding scheme. The study is well reported, and its self-critical tone is stimulating. Nevertheless, its modest, monocultural sample, coarse preference scale, and interpretative leaps (mainly around “cognitive load”) limit the strength of its conclusions. Some findings are even contradictory: experts are referred to make more effort yet supposedly process more efficiently, and present scan-paths that change with façade material. In general, this paper presents valuable hypothesis, particularly about how training redirects attention from decorative to contextual cues. But this needs replication with larger and more diverse collaborators and tighter stimulus control.

Vartanian et al. [

5], innovates by pairing a factorial architectural manipulation with simultaneous beauty and approach judgments inside a scanner. This study is methodological adventurous and confirms that higher ceilings and openness

look better. Yet, the sample is reduced, the fMRI thresholding is liberal, and the imagery is quite uncontrolled. Future studies with immersive VR, larger and diverse samples, and finer-grained rating scales are needed.

5. Guidelines for Education and Field Use of Eye-Tracking in Architecture

While recent studies have advanced the theoretical and empirical understanding of ET applications in architecture, there is a lack of operational guidance on how to effectively implement ET in educational and in situ research contexts. To address this gap, we propose two sets of practice-oriented guidelines, one focused on architectural pedagogy and the other on field studies, based on the evidence reviewed in this article.

5.1. Best Practices for Using Eye-Tracking in Architectural Education

The integration of ET into architecture education has been highlighted as an opportunity to foster reflective learning, deepen students’ understanding of user-centered design, and align academic training with evidence-based practices [

28]. However, its pedagogical value depends not only on technological availability but also on methodological intentionality. The following practices are grounded in findings across multiple studies:

Table 1.

Best Practices for Using Eye-Tracking in Architectural Education. (Sources: Rusnak and Rabiega [

28], with methodological guidance from eye-tracking literature).

Table 1.

Best Practices for Using Eye-Tracking in Architectural Education. (Sources: Rusnak and Rabiega [

28], with methodological guidance from eye-tracking literature).

| Recommended Practice |

Purpose or Benefit |

| Embed ET exercises (e.g., building walk-throughs or peer design reviews) in coursework |

Promotes reflective learning and evidence-based design by revealing where students focus attention |

| Highlight expert vs. novice gaze patterns in critiques |

Deepens students’ understanding of user-centered design by illustrating perceptual differences |

| Integrate ET projects and assignments into the curriculum |

Broadens students’ awareness of how designs are perceived by users |

| Plan for equipment constraints (cost, lab space) |

Addresses practical implementation barriers and sets realistic project scope |

5.2. Checklist for Conducting in Situ Eye-Tracking Studies in Architecture

Conducting eye-tracking studies in real or realistic architectural contexts involves numerous technical and ethical considerations. Based on challenges identified by Mahmoud et al. [

40], Zhipeng and Pesarakli [

45], and Holmqvist and Andersson [

2], we propose the following checklist to support robust data collection and analysis:

Table 2.

Checklist for Conducting in Situ Eye-Tracking Studies in Architecture. (Sources: Rusnak and Rabiega [

28], with methodological guidance from eye-tracking literature).

Table 2.

Checklist for Conducting in Situ Eye-Tracking Studies in Architecture. (Sources: Rusnak and Rabiega [

28], with methodological guidance from eye-tracking literature).

| Step/Item |

Purpose or Rationale |

Considerations or Requirements |

| Define research objectives/questions |

Focus the study and align methods with goals |

Formulate clear research questions on visual perception or navigation in built environments |

| Select study design and equipment |

Choose ET hardware and setting to match objectives |

Balance ecological validity vs. experimental control (e.g., VR vs. real-world; screen-based vs. mobile trackers) |

| Establish participant criteria |

Ensure a representative, consistent sample |

Screen for vision or cognitive issues; obtain informed consent; consider participant fatigue and comfort |

| Calibrate and test equipment |

Maximize data accuracy and reduce error |

Perform individual calibration for each participant; monitor and correct calibration drift; check for data loss (especially outdoors) |

| Conduct the eye-tracking session |

Collect gaze data under real-world conditions |

Monitor data quality in real time; minimize head/body movements; control lighting and distractions as much as possible |

| Analyze gaze data |

Identify attention patterns quantitatively |

Compute fixation counts/durations and scan paths; exclude blinks or noise; use areas-of-interest or heatmaps as appropriate |

| Triangulate and interpret results |

Contextualize gaze with other measures |

Supplement ET data with surveys or interviews to explain visual behavior; interpret findings in the architectural context |

These operational guidelines aim to enhance methodological transparency, data quality, and pedagogical relevance in future eye-tracking studies. As ET technology becomes more accessible and embedded in academic and professional settings, these best practices can contribute to a more informed, reflective, and user-centered architectural culture

6. Conclusions

Integrating ET into research and practice offers a transformative method to merge design intuition with scientific evidence. This study has highlighted how ET can enrich our understanding of the human visual experience of architecture. By objectively capturing where people look, for how long, and in what sequence, ET provides insight into the minds of the users as they meet architectonic contexts. Architects and researchers can utilize this to ensure that the intended focal points of a design catch the gaze and that critical information (wayfinding cues or safety features) is not being overlooked.

In essence, ET data serves as feedback of the efficiency of design elements. For instance, if a striking lobby artwork was meant to impress visitors, but ET shows most people walking past it without a glance, designers may reconsider its placement or emphasis. Likewise, if students are not noticing certain features that experts consider important, educators can use that insight to adjust how design principles are taught. The comprehensive value of ET in architecture lies in its capacity to validate and inform design decisions with empirical user data, promoting a more evidence-based and user-centered design process.

In practical terms, our findings lead to several actionable recommendations for different stakeholders in the field. For educators, we recommend incorporating ET exercises and projects in the curricula of architecture. Even simple experiments, such as having students to use an eye-tracker while exploring a building or reviewing designs of peers, can reveal biases in observation and prompt discussions on why certain elements attract attention. This practical approach can cultivate more mindful observer. As students see the discrepancies between what they notice and what users notice, they learn to design with the gaze of the user in mind. Rusnak and Rabiega [

28] note that such integration not only broadens knowledge of perception but also encourages the interest of the students in the research dimension of design.

For practitioners (architects and urban designers), we suggest adopting ET as a tool in design evaluation and refinement process. Before finalizing a design, conducting ET studies with representative users can generate intuitions that traditional critiques or client feedback might oversee. Practitioners could use mobile ET in a full-scale mock-up or VR walkthrough of a new space to check if people fail to notice an important sign or consistently get visually drawn to an unintended area. With the increasing availability of portable and user-friendly ET devices, even small firms can consider collaborating with specialists or universities to perform such user tests. The data gathered can inform interactive design changes, leading to architectonic contexts that are not just artistically compelling but also intuitively navigable and engaging.

For researchers, the continued development of ET in architecture should focus on both expanding the scope of studies and addressing current limitations. There is a need for more cross-disciplinary collaboration, working with vision scientists to interpret complex gaze patterns, or with data experts to handle the big data aspects of ET (a single study can collect thousands of data points per minute).

Future research should also prioritize triangulation of methods. Combining ET with other techniques like biometric sensors (to measure stress or arousal), brain imaging, or post-experiment interviews, researchers can create a richer picture of the human-building interaction, linking where people look to how they feel or decide. Such multimodal approaches will help overcome the interpretation ambiguity of only using gaze data. Moreover, replicating and extending studies to diverse contexts and populations is important. As Aalto and Steinert [

4] recommend, we should undertake systematic replication studies on key phenomena, verifying if, in different cultural contexts, architects consistently scan spaces differently than non-architects, or whether certain design features universally attract attention.

These efforts will strengthen the generalization of ET findings and integrate them into foundational theory (e.g., confirming whether “universal” design principles exist in terms of human visual response).

Technologically, a clear direction for future research would be enhancing the accuracy and robustness of ET in architectonic contexts. This includes improving calibration algorithms, developing trackers that function reliably outdoors and in motion (possibly through sensor fusion or computer vision techniques), and enabling the study of multi-user architectonic contexts. Advances might allow tracking the gaze of a group of people simultaneously as they interact in an architectonic context, opening new possibilities to study social and collaborative dynamics in contexts like classrooms or public squares.

Another promising possibility is a deeper integration of VR and augmented reality (AR) with ET. As our review mentioned, VR provides a controlled yet immersive platform for testing design alternatives. Future research can improve this advantage by ensuring that VR-generated insights translate to real-world outcomes. And, through using ET in VR, not just for observation, but as an interactive input (e.g., architecture that adapts in real-time to where users look, creating adaptive architectonic contexts).

Lastly, the field would benefit from developing open databases of ET data and standardized protocols, so that different studies can be more easily compared and collectively extracted to establish broader patterns.

In conclusion, ET is catalyzing a shift in architecture towards more empirically grounded design and teaching practices. It highlights the perspective of the user in a way that was previously difficult to achieve, quantifying the subtle interaction between attention, perception, and design features. As ET hardware and analysis techniques continue to improve, we anticipate that its adoption will become more usual. From classrooms where students improve their designs based on viewer gaze data, to professional design firms validating concepts through “eye-tracked” user experience testing.

Finally, the integration of ET in architecture enriches the ability of the discipline to create architectonic contexts that are not only aesthetically pleasing and functionally efficient, but also profoundly aligned with innate patterns of human vision and cognition. This synergy between technology and design research announces a future in which architectonic contexts are worked with a deeper understanding of their users, leading to a more intuitive, comfortable, and human-centered architecture.

Concluding, we think it is pertinent to connect this investigation with the work and investigation of Jan Gehl. Gehl marked an important Shift in architecture, from a metalanguage to a user centered design. This sift was (and is) crucial to architecture and we wish to keep walking this path. The convergence of contemporary eye-tracking research with Jan Gehl’s human-centric design principles underscores a shared commitment to architecture at the pedestrian scale. As this review has shown, eye-tracking (ET) has matured into an

evidence-based lens for creating intuitive, legible, and human-centered environments. This scientific approach resonates with Gehl’s long-standing emphasis on human-scale design and sensory experience in public spaces [

65]. Both perspectives prioritize understanding how people perceive and navigate the built environment. ET studies reveal where occupants focus, for how long, and in what sequence, providing objective insights that complement designers’ intuition. Likewise, Gehl begins with the

“spaces between buildings,” observing how pedestrians move and feel at eye level and walking speed [

65,

66]. In effect, the technological precision of eye-tracking amplifies Gehl’s qualitative observations: both confirm that architecture must speak to our senses and scale of movement to be truly responsive and comfortable for its users. The result is a unified vision of design—rooted in data and human experience alike—that advocates lively, people-oriented places rather than abstract edifices.

Crucially, eye-tracking now offers empirical support for many of Gehl’s theories on human comfort, engagement, and social interaction in cities. Gehl has posited that the quality of an environment directly influences how long people linger and whether optional, recreational activities blossom into social encounters [

67]. Eye-tracking metrics help validate these insights by objectively indicating which design features captivate attention and invite prolonged engagement. For example, Gehl observed that rich,

5 km/h details at street level (varied façades, doors, and signage) enrich the pedestrian experience [

66]; ET studies corroborate this by showing that human-scaled, detail-oriented frontages consistently draw and hold viewers’ gaze, whereas monotonous “60 km/h” streetscapes fail to do so [

66]. Moreover, by capturing where people naturally look in a plaza or streetscape, eye-tracking can confirm that

“comfort features”—such as seating, greenery, or clear wayfinding cues—are noticed and utilized as intended. In turn, this feedback allows architects and urban designers to refine spaces so that critical information is not overlooked and pedestrians feel at ease and oriented. The synergy between Gehl’s humanistic framework and eye-tracking’s analytics thus heralds a more evidence-based approach to human-scale urban design. With emerging methods even enabling multi-user gaze studies in public squares, designers can quantitatively examine the

“life between buildings” that Gehl sees as the heart of city life [

67]. In sum, integrating eye-tracking into architectural research and practice reinforces Gehl’s vision with scientific rigor – ensuring that our cities are not only designed

for people, but are empirically tested and continuously improved to maximize comfort, engagement, and vibrant social interaction.

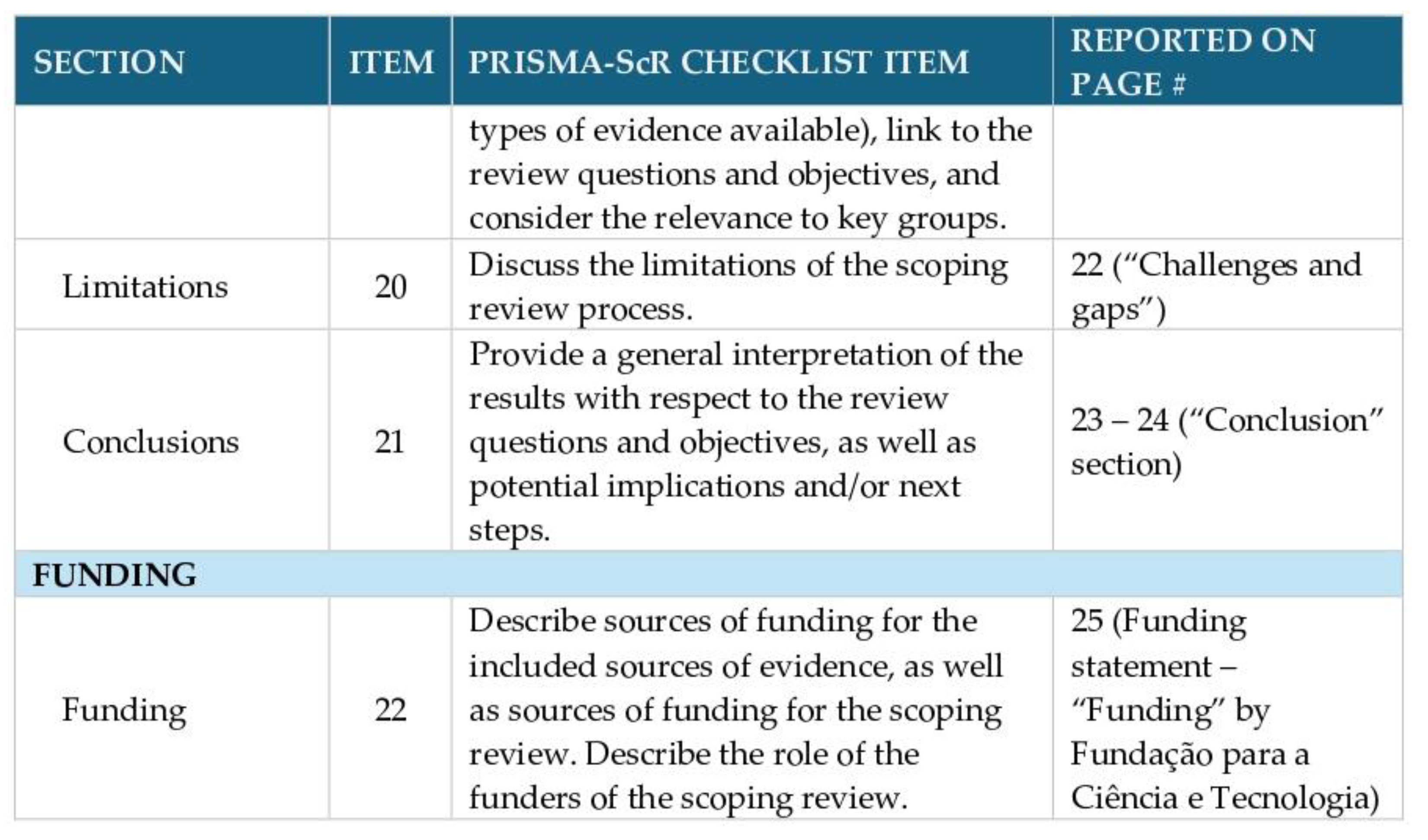

Figure 5.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist. (Source: Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850).

Figure 5.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist. (Source: Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018; 169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850).

Author Contributions

Mário Bruno Cruz was the main contributor for this revision. Francisco Rebelo gave its structure and revised. And Jorge Cruz Pinto revised this article.

Funding

This article was funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT) doctoral grant number 2024.00282.BD. This work is financed by national funds through FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., under the Strategic Project with the references UID/04008: Centro de Investigação em Arquitetura, Urbanismo e Design.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ET |

Eye tracking |

| SR |

Scoping Review |

| LR |

Literature Review |

| GenAI |

Generative artificial intelligence |

| UX |

User experience |

| HVS |

Human Visual System |

| ms |

milliseconds |

| VR |

Virtual reality |

| AR |

Augmented reality |

Glossary

ARCHITECTONIC CONTEXTS – Corresponds to all contexts, exterior (e.g., built landscape), interior (e.g., rooms, workplaces) or interfaces (e.g., façades, windows), which are considered architecture, either conceived by architects or nonarchitects. Source: authors. FOVEA – “A small depression in the center of the macula that contains only cones and constitutes the area of maximum visual acuity and color discrimination” (of the eye). Source: Merriam Webster, 2025. STIMULUS – “A visual object or element that a participant views. Stimuli can be static, like facial expressions, or dynamic, like short video clips.” Source: Google Search, 2025.

References

- Duchowski, A. T. Eye tracking methodology: Theory and practice. Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2017.

- Holmqvist, K.; Andersson, R. Eye tracking, a comprehensive guide to methods, paradigms and measures, 2nd ed.; Lund Eye-Tracking Research Institute.: Lund, Sweden, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Reasearch Methodology 2007, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalto, P.; Steinert, M. Emergence of eye-tracking in architectural research: a review of studies 1976-2021. Architectural Science Review 2004, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, O.; Navarrete, G.; Chatterjee, A.; Fich, L. B.; Gonzalez-Mora, J. L.; Leder, H.; . . . Skov, M. Architectural design and the brain: Effects of ceiling height and perceived enclosure on beauty judgements and approach-avoidance decisions. Journal of Environmental Psychology 2014.

- Bojko, A. Eye tracking the user experience: A practical guide to research. Rosenfeld Media: New York, NY, United States of America, 2013.

- Rayner, K. Eye movements in reading and information processing: 20 years of research. Psychological Bulletin 1998, 124, 372–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchowski, A. T. A breadth-first survey of eye-tracking applications. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers 2002, 34, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, A.; Ball, L. J. Eye Tracking in HCI and Usability Research. In C. Ghaoui, Encyclopedia of Human Computer Interaction. IGI Global: Hershey, PA, United States of America, 2006.

- Robinson, D. A. The oculomotor control system: A review. In Proceedings of the IEEE, 1968, 56, 1032–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Conde, S.; Macnick, S. L.; Hubel, D. H. The role of fixational eye movements in visual perception. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2004, 5, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, R. S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiener, J. M.; Franz, G. Isovists as a means to predict spatial experience and behavior. In Lecture Notes on Computer Science, 3343, 2015. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, M. Effects of familiarity and plan complexity in wayfinding in simulated buildings. Journal of Environmental Psychology 1992, 12, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. The experience of landscape. John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, United States of America, 1975.

- Buswell, G. T. How people look at pictures: a study of the psychology and perception in art. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, United States of America, 1935.

- Yarbus, A. L. Eye movements and vision; Riggs L. A., Ed.; Haigh, B. , Trans.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, United States of America, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Janssens, J. Hur man betraktar och identifierar byggnadsexteriörer: metodstudie [How people see and indentify building exteriors - A method study]. Tekniska Högskolan i Lund, Sektionen för Arkitektur. Tekniska Högskolan i Lund: Lund, Sweden, 1976.

- Janssens, J. Skillnader mellan arkitekter och lekmän vid betraktande av byggnadsexteriörer [The effect of professional education and experience on the perception of building exteriors]. Tekniska Högskolan i Lund, Sektionen för Arkitektur. Tekniska Högskolan i Lund: Lund, Sweden, 1984.

- Weber, R.; Choi, Y.; Stark, L. The impact of formal properties on eye movement during the perception of architecture. In ACSA 1995, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Foulsham, T.; Walker, E.; Kingstone, A. The where, what and when of gaze allocation in the lab and the natural environment. Vision Research 2011, 51, 1920–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayegh, A.; Andreani, S.; Li, L.; Rudin, J.; Yan, X. A new method for spatial analysis: Measuring gaze, attention, and memory in the built environment. In Proceedings of the 1st International ACM SIGSPATIAL Workshop on Smart Cities and Urban Analytics - UrbanGIS’15, ACM Press: New York, NY, United States of America; 2015; 42-46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noland, R. B.; Weiner, M. D.; Gao, D.; Cook, M. P.; Nelessen, A. Eye-tracking technology, visual preference surveys, and urban design: Preliminary evidence of an effective methodology. Journal of Urbanism 2017, 10, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisińska-Kuśnierz, M.; Krupa, M. Eye -tracking in research on perception of objects and spaces. Architecture and Urban Planning 2018, 12, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lisińska-Kuśnierz, M.; Krupa, M. Suitability of eye-tracking in assessing visual perception in architecture - A case study concerning selected projects located in Cologne. Buildings 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, J.; Cho, J. Y. A triangular relationship of visual attention, spatial ability and creative performance in spatial design: An exploratory case study. Journal of Interior Design 2021, 46, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabaja, B.; Kupa, M. Possibilities of using the eye tracking method for research on the historic architectonic space in the context of its perception users. Wiadomości Konserwatorskie - Journal of Heritage Conservation 2027, 52, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Rusnak, M. A.; Rabiega, M. The potential of using an eye tracker in architectural education: Three perspectives for ordinary users, students and lecturers. Buildings 2021, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]