1. Introduction

Invasive species are causing shifts and disruptions in ecosystems worldwide [

1], which reduces biodiversity [

2,

3] and diminishes ecosystem services [

4,

5,

6]. Nonnative invasive shrubs (NNIS) were introduced into many ecosystems deliberately, such as to serve as a food source for wildlife, or accidentally escaped from urban gardens. Due to their success in nonnative habitats, they continue to invade more land, causing numerous direct and indirect damages. Direct damages include the competitive exclusion of ecologically related native species, which threatens them with extirpation or the extinction of endemic species [

2,

7,

8]. Indirect damages include detrimental effects on soil fungi [

9], altering and impairing decomposition [

10,

11], threatening species that depend on the excluded native shrubs [

12,

13,

14,

15] and potentially leading to their extinction, and facilitating the establishment of detrimental species, such as disease vectors [

16,

17].

In the Middle East of North America, grassland habitats that are not regularly mowed or burned, such as the few remaining remnant prairies and restored prairies are increasingly invaded and overgrown by NNIS, including several species of honeysuckle of the genus

Lonicera, such as the Tartarian Honeysuckle (

Lonicera tatarica L.) and the Showy or Bell’s Honeysuckle (

Lonicera x bella Zabel), and

Elaeagnus species such as the Autumn Olive (

E. umbellata Thunb.) and Cherry Silverberry (

E. multiflora Thunb.), which all originating in NE Eurasia. Prairies are important ecosystems with high biodiversity [

18,

19,

20], providing essential ecosystem services that include sheltering pollinators and small animals [

21,

22,

23,

24], carbon sequestration [

25,

26], and sustaining the health of the surrounding ecosystem [

27,

28].

Remote sensing of plant communities using UAVs is becoming increasingly indispensable due to its cost-effective nature, decreasing technology prices, and the ability to save time for the necessary fieldwork in areas where access may be limited [

29,

30,

31,

32].

The purpose of this research was to evaluate whether orthomaps based on RGB images acquired by UAVs provide a reliable means to distinguish between native and invasive shrubs and quantify the extent of invasive shrub invasion in grasslands.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Target Species

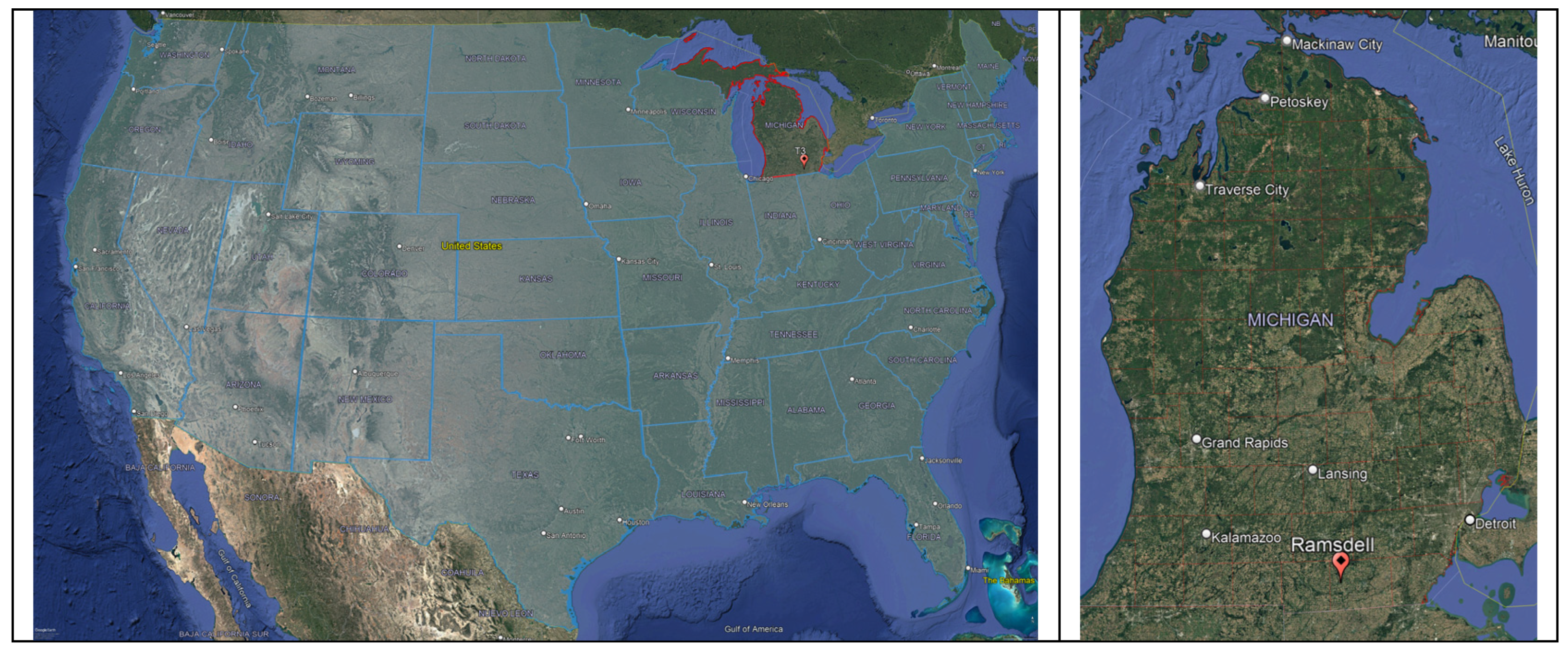

The study area, Ramsdell Park, is a 0.73 km

2 publicly accessible municipal park run and maintained by Lenawee County. It is located approximately 20 km west of Adrian, Michigan, USA (41.9083° N, 84.2596° W) at an average elevation of 295 meters (

Figure 1a, b). The climate falls under the Dfb category of the Köppen Climate Classification [

33], characterized by humid continental conditions with mild summers and a wet year-round pattern (

Table 1).

The landscape mosaic of Ramsdell Park comprises old field vegetation, prairies, deciduous forests, and shallow ponds (

Figure 1c). Before becoming a park in 1991, the area was farmed and was donated to the County by the owner, David R. Ramsdell, to be converted into a nature reserve and developed into a park. His will reads in parts: “I give my farm of 180 acres to the Lenawee County Parks Commission to be used as a park with nature and hiking trails and areas to observe birds and wildlife. I make this gift so that future generations can enjoy this land, the out-of-doors, birds, and nature as I have for so many years.” Park development was promoted by a major grant from the Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund and included collecting seeds from native plants in the region and sowing them into previously tilled fields that had developed into old field vegetation.

To improve the biodiversity of the park, the County began removing several invasive shrub species that had started to overgrow the restored prairies and act as understory shrubs in the forested areas of the study area, especially the Tartarian Honeysuckle (

Lonicera tatarica L.), Showy or Bell’s Honeysuckle (

Lonicera x bella Zabel), Autumn Olive (

Elaeagnus umbellata Thunb.) and Cherry Silverberry (

Elaeagnus multiflora Thunb.). Some of these species were successfully located and targeted by UAVs before [

35,

36,

37,

38].

2.2. UAV Imaging

The UAV used in the research was the DJI Phantom 4 Pro drone (SZ DJI Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), equipped with an RGB camera featuring a 1-inch CMOS sensor, which captured 20-megapixel natural color stills. All drone flights were conducted between 11 a.m. and 4 p.m. on sunny days with a wind speed of < 25 km/h.

We set the drone on a flight path over selected grassland parcels using the free mobile app Pix4Dcapture (version 1.59.0, Pix4D SA, Prilly, Switzerland). After experimenting with different above-ground levels (AGL) of 100, 200, and 400 feet, we settled on 200 feet for generating orthomosaic maps, a traveling speed of 5 meters per second, and front/side image overlays of 80% and 70%, respectively. These settings were recommended by Gene Huntington of the Ecosystem Services Consulting firm Steward Green,

https://stewardgreen.com. FAA clearance and transparency of flight in a public location were ensured by obtaining an Integrated Airman Certification, and flight planning was enacted to verify that no restricted flight zones existed within the flight parameters of the park. Due to the extended spring and fall phenologies of invasive shrubs [

39,

40,

41,

42], we conducted our aerial surveys in late fall 2023 (November 13) and early spring 2024 (April 15).

From the drone images, DEM models and orthomosaic maps were stitched together and calculated using Agisoft Metashape Professional (version 2.2.1, Agisoft LLC, St. Petersburg, Russia). For further analysis, models and maps were imported as KMZ files into Google Earth Pro (version 7.3.6.1021, Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, U.S.) or as GeoTIFF files into QGIS (version 3.4.8-Bratislava).

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

As canopy trees obscure the detection of invasive shrubs in the understory during aerial surveys, this study focused on detecting invasive shrubs in the more visible grassland and shrubland parcels of the park. Areas suspected of having an infestation by invasive shrubs indicated by Google Earth satellite imagery and our initial aerial surveys were checked on-site and verified through photography and identification using the iPhone app PlantNet (Pl@ntNet, by the French research consortia CIRAD, INRAE, INRIA, and IRD), as well as literature covering the local flora [

43,

44]. Site visits were also conducted to identify the highest-quality prairie and savannah areas of the park for inclusion in the study, based on their native floral biodiversity.

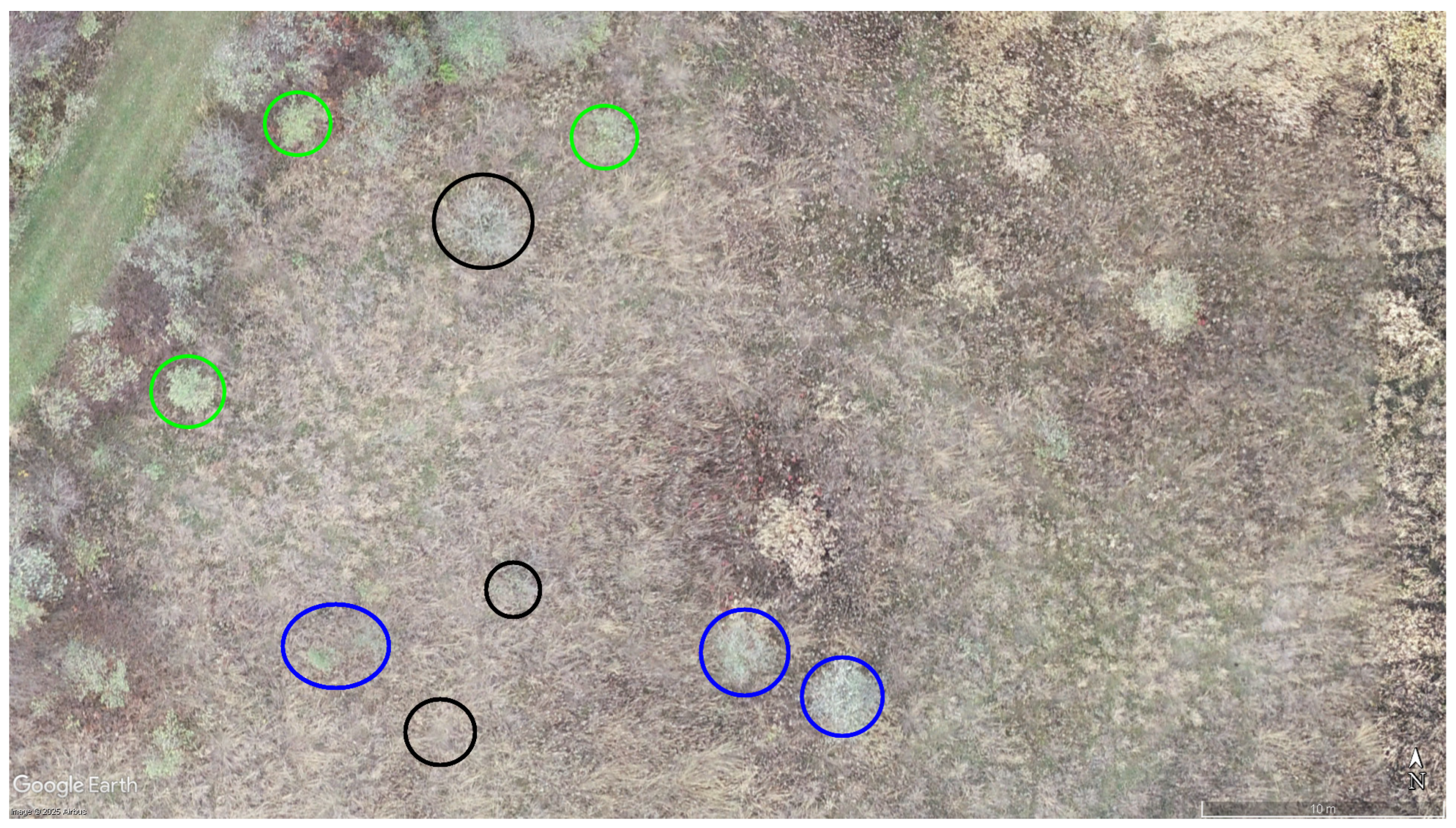

The presence of invasive

Elaeagnus multiflora and

umbellata shrubs was inferred from the presence of shrubs with a blue-green tint (#088F8F) in late fall orthomaps, when no foliage remained on other shrubs or trees (Figure 3) [

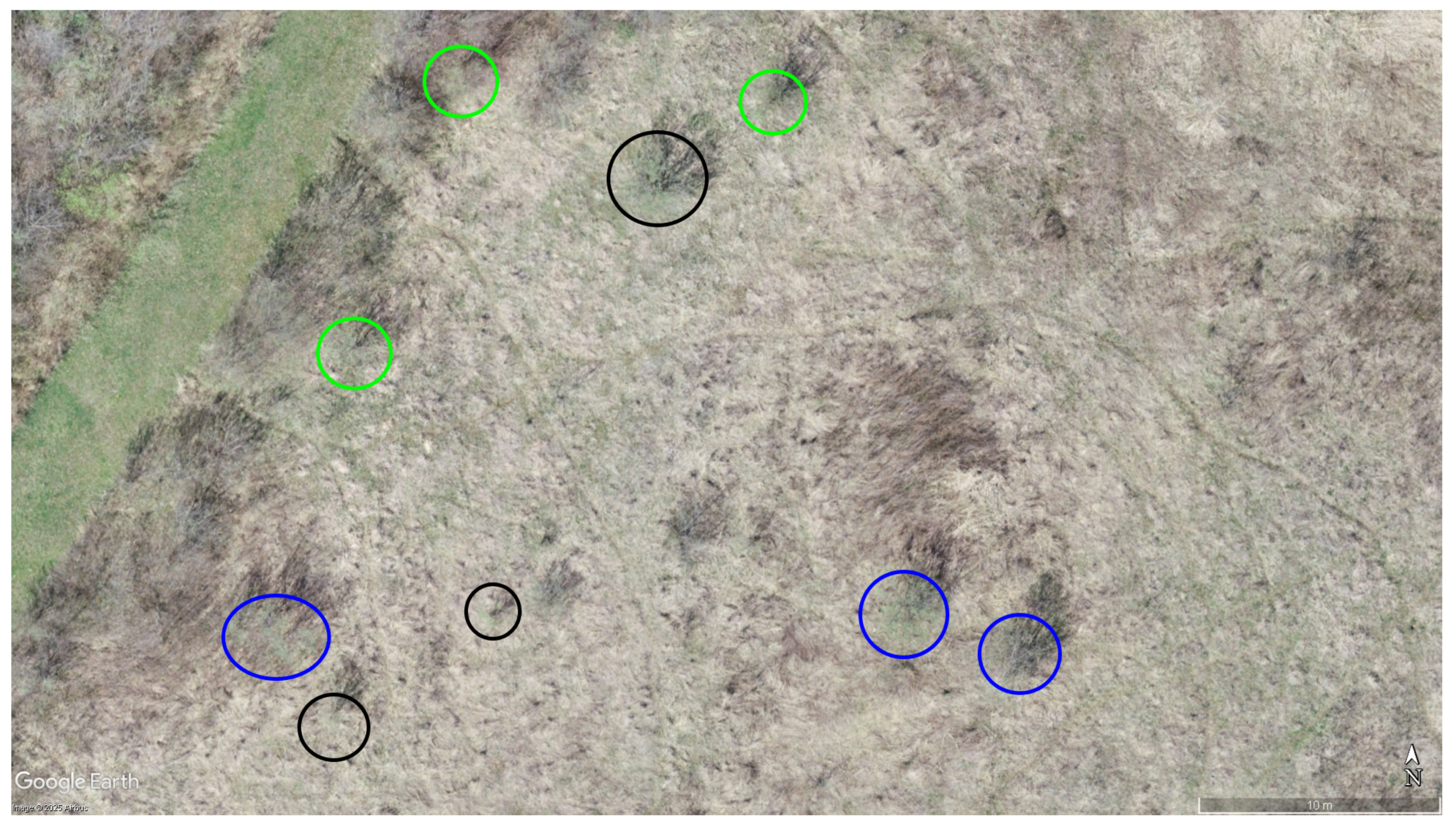

42]. In contrast, the presence of invasive honeysuckles was inferred from the presence of shrubs with a light green tint (#90EE90) in early spring, when no foliage had yet developed on native shrubs or trees (Figure 4) [

42]. The accuracy and reliability of this determination were verified in a blinded choice test. One of the authors (TB) prepared 40 GPS waypoints of shrubs he photographed on site, consisting of 20 invasive shrubs (8 honeysuckles and 12 autumn olives) and 20 non-invasive shrubs (mainly Gray Dogwood,

Cornus racemosa Lam.). These waypoints were based on on-site localizations of isolated shrubs with a handheld Garmin eTrax 10 GPS receiver (Garmin Ltd., Olathe, Kansas), which provided an accuracy of 5-10 meters. Due to this limitation, only shrubs growing isolated from other shrubs were selected. TB send these waypoints to the other author (TW) to identify the georeferenced shrubs on the orthomaps as either invasive or non-invasive shrubs. TB then categorized TW’s choices as correct or incorrect. The observed frequencies of correct answers were then tested against the expectation of a uniform distribution using a Chi-Square test. Unfortunately, this procedure was not possible for the spring mapping, as the County removed most of the invasive shrubs using a brush mower before pictures of the shrubs at the mapped locations could be taken.

3. Results

Compared to drone surveys in September and October 2023 (

Figure 2), the orthomaps of the grassland and shrub areas in late November 2023 (

Figure 3) and early April 2024 (

Figure 4) showed that only a few shrubs had maintained/developed foliage, which appeared in different shades of green. This allowed us to map out the locations of suspected invasive shrubs and estimate the degree of infestation in the shrub- and grassland-dominated parcels of the park [

31].

The accuracy in distinguishing between invasive and native shrubs using orthomaps in late fall was high (92.5%), with

X2 (1,

N = 40) = 28.9,

p < 0.0001;

Table 2).

Using the fall orthomaps of the entire park and based on the extent of late fall foliage and foliage color, we estimated the invasive shrub coverage of the seven most valuable central and northeastern grassland parcels to be approximately 14,569 m², or 9.4% of the included grassland area of 155,630 m². This corresponds to class V in [

45]. The plots varied significantly in their percentage of invasive shrubs, with the highest coverage at 19.8% (class IV, [

14]) and the lowest at 0.8% (class VII, [

45]). The grassland sections in the middle of the park exhibited the highest coverage of invasive shrubs, whereas the far northeastern sections showed significantly lower frequencies (

Figure 1A). Most invasive shrubs exhibited a patchy distribution, occurring in clusters rather than being evenly distributed across the grassland (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

Our results support the hypothesis that invasive shrubs can be reliably detected and distinguished (92.5% accuracy) from the surrounding vegetation using RGB orthomaps. The few invasive species misidentified as native shrubs had very few leaves left, diminishing the differences in hue and saturation with the surrounding vegetation. Drone-based identification is, therefore, a cost-effective and rapid method of assessment, avoiding damage to the fragile prairie grasslands that would be inevitable with on-site surveys. However, while the detection of invasive shrubs in late fall was highly satisfactory (

Figure 3 and

Table 2), it was much less convincing in early spring (

Figure 4). This finding aligns with the results of [

9], who found that most invasive shrubs in the U.S. are extending into the late autumn niche, while exhibiting less consistent niche extensions into early spring. Due to their bluish-green leaf color, it was even possible to distinguish the

Elaeagnus species,

E. umbellata and

E. multiflora, from other late-flushing shrubs [

37].

However, some invasive shrub species do extend into the early spring niche, especially certain Asian honeysuckles, such as

Lonicera x bella and

L. tatarica [

42]

, which both occur at the study site, and should therefore be easily identifiable in early spring orthomaps. While our results show some early flushing shrubs in mid-April with the correct shade of green, this is much less visible than in the fall, especially against the background of the dormant grassland vegetation (

Figure 4).

We used our late fall orthomaps to determine the degree of invasion by NNIS on the Ramsdell grasslands to be between 0.8% and 19.8% (class VII-IV, [

14]) or low to medium [

46]. We assume that these values are rather underestimates than overestimates, as our fall orthomaps were based on a drone survey in mid-November, when many NNIS, especially

Lonicera species, had already shed their leaves, like their native counterparts [

42]. These numbers are, therefore, alarming and warrant urgent management measures. Luckily, the County Parks Department has already started removing NNIS using shrub mowers, controlled burning, and pesticide application.

To improve our method, we plan to repeat our surveys next spring using multispectral orthomaps, which are expected to provide significantly better contrast [

36,

47,

48,

49,

50]. We also plan to utilize an RTK GNSS receiver to achieve real-time centimeter-scale positioning, enabling us to more accurately compare the state of individual shrubs in late fall and early spring (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). This should enable us to clearly identify invasive shrubs as

Lonicera or

Elaeagnus species. We are furthermore planning to train a YOLO deep learning model to automatically detect invasive shrubs using our orthomaps [

51,

52], differentiate between the two major genera at Ramsdell, and distinguish their age classes, which require different management practices such as controlled burning, herbicide treatment, and shrub mowers [

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.W.; methodology, T.W. and T.B.; validation, T.W. and T.B.; formal analysis, T.W. and T.B.; investigation, T.B.; resources, T.W.; data curation, T.W.; writing—original draft preparation, T.W.; writing—review and editing, T.W; visualization, T.W. and T.B.; supervision, T.W.; project administration, T.W.; funding acquisition, T.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Oak Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland, and by the Biology Department of Siena Heights University.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available as part of this.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Oak Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland, for providing funding and their support of research and conservation efforts at Ramsdell Park. We would also like to thank the Biology Department of Siena Heights University for providing the necessary resources, especially the UAV, and Gene Huntington of Steward Green Wildlife Habitat Solutions for providing technical and operational expertise in drone imaging for our missions. This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper entitled “Drone-based assessments of invasive shrubs in Ramsdell Park, Lenawee County, Michigan”, which was presented at the 2024 Great Lakes Regional Conference of the Ecological Society of America in Kalamazoo, Michigan, April 5-7, 2024 [58].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UAV |

Uncrewed Aerial Vehicle |

| NNIS |

Nonnative invasive shrubs |

References

- Peller, T.; Altermatt, F. Invasive Species Drive Cross-Ecosystem Effects Worldwide. Nat Ecol Evol 2024, 8, 1087–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Hulme, P.E.; Simberloff, D.; Bacher, S.; Blackburn, T.M.; Carlton, J.T.; Dawson, W.; Essl, F.; Foxcroft, L.C.; Genovesi, P.; et al. Scientists’ Warning on Invasive Alien Species. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 2020, 95, 1511–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilsey, B.; Martin, L.; Xu, X.; Isbell, F.; Polley, H.W. Biodiversity: Net Primary Productivity Relationships Are Eliminated by Invasive Species Dominance. Ecol Lett 2024, 27, e14342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turbelin, A.J.; Cuthbert, R.N.; Essl, F.; Haubrock, P.J.; Ricciardi, A.; Courchamp, F. Biological Invasions Are as Costly as Natural Hazards. Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation 2023, 21, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagne, C.; Leroy, B.; Vaissière, A.-C.; Gozlan, R.E.; Roiz, D.; Jarić, I.; Salles, J.-M.; Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Courchamp, F. High and Rising Economic Costs of Biological Invasions Worldwide. Nature 2021, 592, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Rai, P.; Singh, J.S. Invasive Alien Plant Species: Their Impact on Environment, Ecosystem Services and Human Health. Ecol Indic 2020, 111, 106020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Jarošík, V.; Hulme, P.E.; Pergl, J.; Hejda, M.; Schaffner, U.; Vilà, M. A Global Assessment of Invasive Plant Impacts on Resident Species, Communities and Ecosystems: The Interaction of Impact Measures, Invading Species’ Traits and Environment. Global Change Biology 2012, 18, 1725–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeish, R.E.; McEwan, R.W. A Review on the Invasion Ecology of Amur Honeysuckle (Lonicera Maackii, Caprifoliaceae) a Case Study of Ecological Impacts at Multiple Scales1. tbot 2016, 143, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Dai, Z.; Qi, S.; Du, D. Different Degrees of Plant Invasion Significantly Affect the Richness of the Soil Fungal Community. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e85490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulette, M.M.; Arthur, M.A. The Impact of the Invasive Shrub Lonicera Maackii on the Decomposition Dynamics of a Native Plant Community. Ecol Appl 2012, 22, 412–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harner, M.J.; Crenshaw, C.L.; Abelho, M.; Stursova, M.; Shah, J.J.F.; Sinsabaugh, R.L. Decomposition of Leaf Litter from a Native Tree and an Actinorhizal Invasive across Riparian Habitats. Ecological Applications 2009, 19, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, M.; Hough-Goldstein, J.; Tallamy, D. Arthropod Communities on Native and Nonnative Early Successional Plants. Environ Entomol 2013, 42, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traveset, A.; Richardson, D.M. Biological Invasions as Disruptors of Plant Reproductive Mutualisms. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2006, 21, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipollini, D.; Stevenson, R.; Enright, S.; Eyles, A.; Bonello, P. Phenolic Metabolites in Leaves of the Invasive Shrub, Lonicera Maackii, and Their Potential Phytotoxic and Anti-Herbivore Effects. J Chem Ecol 2008, 34, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzędzicka, E. Plant Invasion-Induced Habitat Changes Impact a Bird Community through the Taxonomic Filtering of Habitat Assemblages. Animals (Basel) 2024, 14, 1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.F.; Dutra, H.P.; Goessling, L.S.; Barnett, K.; Chase, J.M.; Marquis, R.J.; Pang, G.; Storch, G.A.; Thach, R.E.; Orrock, J.L. Invasive Honeysuckle Eradication Reduces Tick-Borne Disease Risk by Altering Host Dynamics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 18523–18527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewhart, L.; McEwan, R.W.; Benbow, M.E. Evidence for Facilitation of Culex Pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) Life History Traits by the Nonnative Invasive Shrub Amur Honeysuckle (Lonicera Maackii). Environmental Entomology 2014, 43, 1584–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Gamon, J.A.; Hogan, K.F.E.; Kellar, P.R.; Wedin, D.A. Prairie Management Practices Influence Biodiversity, Productivity and Surface-Atmosphere Feedbacks. New Phytol 2025, 247, 562–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Gamon, J.A.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Townsend, P.A.; Zygielbaum, A.I. The Spatial Sensitivity of the Spectral Diversity-Biodiversity Relationship: An Experimental Test in a Prairie Grassland. Ecol Appl 2018, 28, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermann, J.S.; Buzhdygan, O.Y. Grassland Biodiversity. Curr Biol 2021, 31, R1195–R1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.J.; Koford, R.R. Habitat and Landscape Associations of Breeding Birds in Native and Restored Grasslands. The Journal of Wildlife Management 2002, 66, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulnik, J.; Plantureux, S.; Dajoz, I.; Michelot-Antalik, A. Using Matching Traits to Study the Impacts of Land-Use Intensification on Plant-Pollinator Interactions in European Grasslands: A Review. Insects 2021, 12, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, I.G.; Portman, Z.M.; Herron-Sweet, C.H.; Pardee, G.L.; Cariveau, D.P. Differences in Bee Community Composition between Restored and Remnant Prairies Are More Strongly Linked to Forb Community Differences than Landscape Differences. Journal of Applied Ecology 2022, 59, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, I.G.; Herron-Sweet, C.R.; Portman, Z.M.; Cariveau, D.P. Floral Resource Diversity Drives Bee Community Diversity in Prairie Restorations along an Agricultural Landscape Gradient. Journal of Applied Ecology 2020, 57, 2010–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, D.A.; Tilman, D. Soil Carbon Sequestration in Prairie Grasslands Increased by Chronic Nitrogen Addition. Ecology 2012, 93, 2030–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Y, B.; Mf, C. Grassland Soil Carbon Sequestration: Current Understanding, Challenges, and Solutions. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2022, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, F.J.; Suter, M.; Lüscher, A.; Buchmann, N.; El Benni, N.; Feola Conz, R.; Hartmann, M.; Jan, P.; Klaus, V.H. Effects of Management Practices on the Ecosystem-Service Multifunctionality of Temperate Grasslands. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 3829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.J. Recent Advances in Understanding Grasslands. F1000Res 2018, 7, F1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainelli, R.; Toscano, P.; Di Gennaro, S.F.; Matese, A. Recent Advances in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Forest Remote Sensing—A Systematic Review. Part I: A General Framework. Forests 2021, 12, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwaimana, M.; Satyanarayana, B.; Otero, V.; Muslim, A.M.; A, M.S.; Ibrahim, S.; Raymaekers, D.; Koedam, N.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F. The Advantages of Using Drones over Space-Borne Imagery in the Mapping of Mangrove Forests. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0200288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Xie, Y.; Huang, Y. UAVs as Remote Sensing Platforms in Plant Ecology: Review of Applications and Challenges. Journal of Plant Ecology 2021, 14, 1003–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.M.; Dziob, K.; Bogawski, P. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Environmental Biology: A Review. European Journal of Ecology 2018, 4, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastrup, R.A. Physical Geography and Natural Disasters - Geosciences LibreTexts; LibreTexts Commons;

- NOAA NCEI, U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access Available online:. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/us-climate-normals/#dataset=normals-annualseasonal&timeframe=15&location=MI&station=USW00004847 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Lautenbach, J.M.; Stricker, N.; Ervin, M.; Hershner, A.; Harris, R.; Smith, C. Woody Vegetation Removal Benefits Grassland Birds on Reclaimed Surface Mines. Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management 2019, 11, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.T. Remote Sensing of Bush Honeysuckle in the Middle Blue River Basin, Kansas City, Missouri, 2016–17; Scientific Investigations Map; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Huelsman, K.; Epstein, H.; Yang, X.; Mullori, L.; Červená, L.; Walker, R. Spectral Variability in Fine-Scale Drone-Based Imaging Spectroscopy Does Not Impede Detection of Target Invasive Plant Species. Frontiers in Remote Sensing 2023, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, A.L. Effects of Forest Fragmentation and Honeysuckle Invasion on Forest Lepidoptera in Southwest Ohio, Wright State University, 2008.

- Donnelly, A.; Yu, R.; Rehberg, C.; Schwartz, M.D. Variation in the Timing and Duration of Autumn Leaf Phenology among Temperate Deciduous Trees, Native Shrubs and Non-Native Shrubs. Int J Biometeorol 2024, 68, 1663–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, E.; Savage, J. Extended Leaf Phenology Has Limited Benefits for Invasive Species Growing at Northern Latitudes. Biol Invasions 2020, 22, 2957–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, A.; Yu, R.; Rehberg, C.; Schwartz, M.D. Characterizing Spring Phenology in a Temperate Deciduous Urban Woodland Fragment: Trees and Shrubs. Int J Biometeorol 2024, 68, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridley, J.D. Extended Leaf Phenology and the Autumn Niche in Deciduous Forest Invasions. Nature 2012, 485, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, E.G.; Reznicek, A.A. Field Manual of Michigan Flora; University of Michigan Press, 2012; ISBN 978-0-472-11811-3.

- University of Michigan Herbarium Michigan Flora Online Available online:. Available online: https://www.michiganflora.net/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Moser, W.K.; Fan, Z.; Hansen, M.H.; Crosby, M.K.; Fan, S.X. Invasibility of Three Major Non-Native Invasive Shrubs and Associated Factors in Upper Midwest U.S. Forest Lands. Forest Ecology and Management 2016, 379, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Liu, X.-S.; Qin, T.-J.; Jiang, F.; Cai, J.-F.; Shen, Y.-L.; A, S.-H.; Li, H.-L. Relative Abundance of Invasive Plants More Effectively Explains the Response of Wetland Communities to Different Invasion Degrees than Phylogenetic Evenness. Journal of Plant Ecology 2022, 15, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasingam, N.; Vanegas, F.; Hele, M.; Warfield, A.; Gonzalez, F. Integrating Artificial Intelligence and UAV-Acquired Multispectral Imagery for the Mapping of Invasive Plant Species in Complex Natural Environments. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, A.C.; Kapos, B.; Liao, S.; Draper, J.; Eddinger, J.; Updike, C.; Frazier, A.E. An Integrated Spectral–Structural Workflow for Invasive Vegetation Mapping in an Arid Region Using Drones. Drones 2021, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzialetti, F.; Frate, L.; De Simone, W.; Frattaroli, A.R.; Acosta, A.T.R.; Carranza, M.L. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-Based Mapping of Acacia Saligna Invasion in the Mediterranean Coast. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How to Use Multispectral Imaging for Drone-Based Habitat Assessment – Every Picture Matters 2024.

- Gautam, D.; Mawardi, Z.; Elliott, L.; Loewensteiner, D.; Whiteside, T.; Brooks, S. Detection of Invasive Species (Siam Weed) Using Drone-Based Imaging and YOLO Deep Learning Model. Remote Sensing 2025, 17, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rominger, K.R.; Meyer, S.E. Drones, Deep Learning, and Endangered Plants: A Method for Population-Level Census Using Image Analysis. Drones 2021, 5, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenreich, J.H.; Aikman, J.M. An Ecological Study of the Effect of Certain Management Practices on Native Prairie in Iowa. Ecological Monographs 1963, 33, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobney, P.; Larson, D.L.; Larson, J.L.; Viste-Sparkman, K. Toward Improving Pollinator Habitat: Reconstructing Prairies with High Forb Diversity. naar 2020, 40, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munger, G. Lonicera Spp. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/shrub/lonspp/all.html (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Munger, G. Species: Elaeagnus Umbellata Available online:. Available online: https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/shrub/elaumb/all.html (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Borland, K.; Campbell, S.; Schillo, R.; Higman, P. A Field Identification Guide to Invasive Plants in Michigan’s Natural Communities; Michigan Natural Features Inventory; Michigan State University Extension: Lansing, Michigan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bakoway, T.; Wassmer, T. Drone-Based Assessments of Invasive Shrubs in Ramsdell Park, Lenawee County, Michigan.; Great Lakes Chapter of the Ecological Society of America: Kalamazoo, April 6 2024. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).