Introduction

The global use of pesticides has played an important role in the intensification of agricultural production. However, it has also raised increasing concerns regarding their potential effects on human health. Scientific evidence indicates that exposure to pesticides, particularly organophosphates, is associated with both acute and chronic neurotoxic outcomes, as well as psychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation (Barbosa et al., 2024; World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2019; Cancino et al., 2023; World Health Organization, 2021; Rother, 2021). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), pesticide self-poisoning accounts for approximately 14 to 20 percent of global suicides, corresponding to more than 110,000 deaths each year, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where highly hazardous pesticides remain widely accessible [2,4].

Beyond occupational pathways, environmental exposure to pesticides has been increasingly recognized as a relevant public health concern in rural communities. Such exposure may occur through multiple non- occupational routes, including pesticide drift from nearby fields, the infiltration of residues into household drinking water sources, and the accumulation of residues in peridomestic soil and dust [6,7]. Several studies have demonstrated that even individual not directly involved in pesticide application, such as women, children, and the elderly, can carry detectable levels of pesticides metabolites in urine, linked to their proximity to treated agricultural areas or domestic use of insecticides [8,9]. These findings underscore the need to consider residential and environmental determinants of exposure, especially in regions characterized by high-intensity agro-industrial practices. Accordingly, monitoring environmental matrices such as soil and water can provide a useful proxy for cumulative pesticide burden in populations lacking biomonitoring infrastructure.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, systematic reviews report associations between pesticide exposure and adverse health outcomes, including genotoxic damage, neurobehavioral impairments, reproductive and endocrine disorders, pregnancy complications, and increased cancer risk [10]. The affected populations include agricultural workers and children, mainly exposed to organophosphates, carbamates, and mixed pesticide compounds [11]. Chronic exposure may occur through aerial dispersion, domestic application, occupational contact, and ingestion of contaminated food or water [12]. Environmental health surveillance systems in the region are limited in scope and technical capacity, with gaps in detection and response, especially in rural areas [13].

A recent meta-analysis reported a statistically significant association between pesticide poisoning and depressive symptoms (odds ratio: 2.94; 95% CI: 1.79–4.83; p < 0.001) [14]. In contrast, non-acute exposure was not associated with increased risk. At the biochemical level, organophosphates inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and induce additional mechanisms including oxidative stress, neuroinflammatory processes, mitochondrial dysfunction, and alterations in serotonergic and glutamatergic neurotransmission—pathways implicated in the neurobiology of depression [1,15,16,17,18]. These effects particularly affect brain regions such as the amygdala and hippocampus, which are involved in emotion regulation and the physiological response to stress [17].

Persistent psychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety, suicidal ideation, and cognitive impairment, have been documented among individuals with long-term occupational exposure to organophosphates, even in the absence of acute intoxication episodes[1,18]. Furthermore, national-level regulatory interventions, including bans on specific highly hazardous pesticides in countries such as Sri Lanka and South Korea, have been associated with substantial reductions in suicide rates (37% to 70%) without negatively impacting agricultural output [2,5].

In Chile, the Maule Region, located in the south-central zone, exhibits high levels of agricultural activity and pesticide utilization [19]. It ranks second nationally in agrochemical sales (15.7%) and in cultivated land area, following the O’Higgins and Araucanía regions, respectively [20].

National surveillance data indicate that in 2023, Maule accounted for 25% of all reported cases of acute pesticide poisoning [21]. Studies conducted in the region have documented extensive environmental exposure affecting both pediatric and adult populations. A recent longitudinal study reported an association between urinary levels of diethyl alkyl phosphate (DEAP) metabolites, biomarkers of organophosphate exposure, and depressive symptoms in male agricultural workers. A dose–response relationship was identified, with associations present even at exposure levels below clinical thresholds [22].

In the Coquimbo Region, located in the north-central zone and characterized by intensive fruit and vegetable production under semi-arid conditions, additional studies have identified chronic health effects related to pesticide exposure. These include genotoxic alterations, neurocognitive deficits, and elevated oxidative stress markers. Affected populations include both agricultural laborers and residents living near areas of pesticide application [13,23,24]. These findings demonstrate the relevance of both occupational and environmental pesticide exposure as determinants of population health, with measurable biological consequences observed across diverse demographic groups in central Chile.

Within this context, the rural area known as “El Arbolillo,” which includes sectors of San Javier and Cauquenes, represents a relevant case. The zone has been the site of a prolonged socio-environmental conflict involving the local population and an industrial pig farming facility. Since its establishment, residents have reported persistent odors, increased fly presence, and intensified insecticide use both inside the facility and in nearby homes. Additionally, other agricultural enterprises in the area, such as vineyards, have also faced fly infestations, which has led to increased agrochemical applications. During the preliminary stage of this research, over 200 administrative, legal, and technical documents were reviewed. These confirmed that the company systematically applied agricultural pesticides, such as organophosphates (diazinon, pirimiphos-methyl) and pyrethroids (cypermethrin), as part of its vector control strategy [25]. These practices have resulted in repeated environmental exposures, triggering official inspections and collective actions by affected residents.

The objective of this study is to assess the association between pesticide residues in peridomestic environments and mental health outcomes in adults residing near an industrial pig farming site in rural Maule, Chile.

This study generates empirical data on the relationship between chronic simultaneous exposure to organophosphate and pyrethroid residues in environmental matrices and mental health outcomes among rural populations not occupationally involved in pesticide application. The resulting evidence contributes to filling a critical knowledge gap in exposure science and rural environmental epidemiology, providing a foundation for regulatory measures on pesticide management, strengthening of environmental health surveillance systems, and targeted public health interventions in territories subjected to sustained agrochemical pressure.

Materials and Methods

This observational cross-sectional study was conducted in rural sectors of the San Javier and Cauquenes communes, within the Maule Region of Chile. The selected areas are characterized by proximity to multiple sources of environmental pesticide exposure, including a large-scale pig farming facility, vineyards, croplands, and forestry operations. These sites have documented histories of intensive agrochemical use and have been associated with persistent socio-environmental conflicts [25].

The target population comprised adult residents (≥18 years) living near the area known as “El Arbolillo,” where the San Agustín del Arbolillo pig production facility, authorized in 2008 for 10,000 sows, is a focal point of environmental controversy [25]. Households located within a 10-kilometer radius of the industrial complex were considered eligible. Participants were randomly selected from registries provided by local community organizations. Continuous residence in the study area for at least 12 months was required for inclusion.

Exclusion criteria were defined to reduce potential confounding. Individuals with a prior diagnosis of neurological disorders or with harmful alcohol consumption patterns, defined as a daily intake exceeding 40 grams for women or 60 grams for men [26], were not eligible to participate.

Sample size was estimated based on data from a previous study conducted in the Coquimbo Region, which identified significant differences in mental health outcomes between individuals exposed and not exposed to pesticides [12]. That study reported lower average scores in psychological well-being among the exposed group, indicating a measurable association between exposure and adverse mental health effects. Using these estimates, a minimum of 60 participants (30 per exposure group) was required to detect statistically significant differences in mental health outcomes with 80% power and a 5% significance level (two-tailed). To account for potential non-responses, incomplete data, or exclusions during fieldwork, a 25% oversampling adjustment was applied to compensate for expected attrition. The final estimated sample size was set at 80 individuals.

Data collection Techniques and Instruments

Between December 2023 and January 2024, standardized psychosocial instruments were applied on an individual basis, and environmental samples were obtained from participants’ households. Data collection was conducted at a community facility in El Arbolillo and in participants’ homes. The field team was composed of trained professionals, including psychologists, physicians, biochemists, biologists, and related specialists.

a) Pesticide Exposure Assessment

Environmental exposure was evaluated through the analysis of pesticide residues in drinking water and soil samples:

Water samples: Drinking water was collected from household wells and rural supply points. All samples were preserved at 4 °C (±2 °C) during transport and storage to ensure analyte stability. Extraction followed a QuEChERS-based protocol adapted for water matrices, involving acetonitrile partitioning and dispersive solid-phase extraction. Analytical detection of chlorpyrifos, diazinon, cypermethrin, and permethrin was performed using gas chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS). All water analyses were conducted at the Bioprocess Laboratory of the Universidad Católica del Maule [27].

Soil samples: Surface soil (0–10 cm) was collected from peridomestic areas near agricultural and industrial sites, including vineyards, forestry plantations, and pig farms. Samples were sieved, air-dried, and stored at 4 °C (±2 °C) prior to analysis. A modified QuEChERS method adapted for soil matrices was used for extraction, employing acetonitrile with buffering salts and subsequent clean-up with PSA and C18 sorbents to minimize matrix effects. Quantification of chlorpyrifos, diazinon, and lambda-cyhalothrin was performed using GC-MS/MS at the Bioprocess Laboratory of the Universidad Católica del [28,29].

Georeferencing: Geographic coordinates of each participant's residence and nearby potential exposure sources (e.g., pig farms, vineyards, forestry plantations) were recorded directly in the field. The shortest straight-linear distance (in meters) between each residence and the nearest exposure source was calculated using Google Earth. For spatial visualization and map generation, QGIS software was used to construct georeferenced layers and illustrate proximity patterns between households and identified sources of environmental contamination. These distance values were incorporated as continuous variables in the exposure assessment.

b) Mental health outcome assessment

Mental health outcomes were assessed using a battery of validated self-report instruments designed to evaluate depressive symptoms, anxiety, emotional states, psychological distress, and perceived quality of life:

- -

CES-D scale: The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale is a 20-item instrument that measures the frequency of depressive symptoms during the past week. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0 to 3), yielding a total score from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate greater symptom severity. The scale was analyzed as a continuous variable. The Chilean version has demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0.85) [30].

- -

State-trait anxiety inventory – state version (STAI-S): This 20-item scale evaluates current levels of anxiety. Each item is rated from 0 (“Not at all”) to 3 (“Very much so”), with reverse coding for items indicating calmness. Total scores range from 0 to 60. The Chilean adaptation reports excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.92) [16]. Scores were treated as continuous.

- -

Positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS): Comprising two subscales of 10 items each, the PANAS assesses the intensity of positive (PA) and negative affect (NA). Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 to 5), with subscale scores ranging from 10 to 50. Higher scores reflect stronger affective states. The Chilean validation confirmed the two-factor structure with adequate reliability (α = 0.91 for PA, 0.87 for NA) [31].

- -

General health questionnaire – 12 items (GHQ-12): This scale screens for psychological distress, including symptoms related to anxiety, depression, and social functioning. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 to 3), with total scores ranging from 0 to 36. Based on the Chilean validation (α = 0.902) [32], scores were categorized into three levels: 1 = no risk, 2 = moderate risk, and 3 = high risk of anxiety and depressive symptoms.

- -

Short form health survey (SF-12v2): This 12-item questionnaire evaluates self-perceived health status across eight domains, summarized into Physical (PCS) and Mental (MCS) component scores. Scores were standardized (0–100 scale), with lower values indicating poorer health. For analysis, values were classified as low, moderate, and high-risk using percentile cut-offs. The Chilean version demonstrated good reliability (α = 0.899)[33].

c) Covariates

Additional instruments were applied to characterize participants’ sociodemographic, occupational, and behavioral profiles, and to adjust for potential confounders in the analysis:

- -

General health and exposure history questionnaire: A structured 26-item questionnaire, adapted from a previously validated instrument [34], was used to collect information on sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, education, marital status, per capita household income, and years of residence in the area), occupational history, disability status, and medical conditions potentially linked to pesticide exposure, including past episodes of acute poisoning. It also included items on occupational and domestic pesticide exposure. Anthropometric measurements were taken using a digital scale and stadiometer, with weight recorded in kilograms and height in centimeters.

- -

Alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST 3.0): This 8-item screening instrument assesses the level of risk associated with the use of ten psychoactive substances, including tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, sedatives, and others. It evaluates both lifetime and recent use, adverse consequences, signs of dependence, and intravenous administration. Risk levels are categorized as low, moderate, or high. The Chilean validation demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.91) [35]. In this study, the ASSIST was used as a covariate to control for behavioral factors that may confound associations between pesticide exposure and mental health outcomes.

All mental and physical health instruments were administered by trained health professionals with prior experience in community-based assessments. These professionals were specifically trained in the standardized application of each questionnaire, ensuring consistency in data collection and improving the reliability and comparability of responses across participants.

Analysis plan

Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel matrix using a double-entry procedure to reduce transcription errors. An initial exploratory analysis was conducted to identify missing data, outliers, duplicate entries, and to evaluate the distributional properties of key variables.

Pesticide concentrations in soil (µg/kg) and water (ppb) were processed using a substitution method for values below the analytical limit of detection (LOD). Specifically, non-detects were replaced with LOD divided by the square root of two (LOD/√2), a standard approach for handling left-censored environmental data and reducing estimation bias (

Table 1).

Categorical variables were described using absolute and relative frequencies. Continuous variables were summarized with means, medians, standard deviations, and interquartile ranges, according to distribution. Group comparisons were performed using non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney U and Kruskal–Wallis), and associations between continuous or ordinal variables were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

Measures of agreement were calculated for categorical variables when applicable. Associations between pesticide concentrations, health outcomes, and residential proximity to exposure sources were initially examined through bivariate analyses. Multiple linear regression models were then fitted, incorporating covariates selected based on previous studies and conceptual relevance: age, sex, education, marital status, per capita income, years of residence, occupational and domestic pesticide exposure, weight, height, and substance use risk.

Given the presence of outliers and heteroscedasticity identified during exploratory analysis, robust linear regression was applied using Huber’s M-estimator with iteratively reweighted least squares. The final model was selected based on adjusted R² and clarity of interpretation. Sensitivity analyses included exclusion of outliers and comparison with ordinary least squares models. Linearity, residual distribution, and multicollinearity were examined to assess model assumptions.

All analyses were performed using Jamovi (v2.6.26.0) and Stata (v19.0).

Results

The final sample included 82 adults: 54.1% men (n = 44) and 45.9% women (n = 38), with a mean age of 52.4 years (SD = 15.2), ranging from 18 to 78 years. Regarding marital status, 54.1% were married, 25.9% single, 9.4% cohabiting, 8.2% separated or divorced, and 2.4% widowed. For analytical purposes, this variable was recoded into two categories: 63.5% were living with a partner (married or cohabiting) and 36.5% were not. In terms of educational attainment, 31.8% had completed primary education or less, 35.3% had some level of secondary education, and 32.9% had pursued higher education (technical or university). For analysis, this variable was grouped into two categories: 52.9% had not completed secondary education, while 47.1% had completed secondary or higher education.

The mean monthly per capita income was CLP $205,302 (SD = $133,998), equivalent to approximately USD $217 (SD = $141), based on an exchange rate of 945 CLP/USD (April 2025). Reported incomes ranged from CLP $25,000 (USD $26) to CLP $666,666 (USD $705). The average length of residence in the area was 16.3 years (SD = 21.5), reflecting substantial variation in participants’ length of residence.

With respect to tobacco use, 67.1% of participants were classified as low-use category, 28.2% within the moderate-use group, and 4.7% within the high-use category. For alcohol consumption, 89.4% were in the low-use group, 8.2% in the moderate-use group, and 2.4% in the high-use category. Overall, problematic substance use levels in the adults were low. However, a relevant proportion of participants reported moderate levels of tobacco consumption, which may be considered in relation to potential confounding in subsequent analyses.

In the combined analysis of peridomestic soil and household well water samples (

Table 2), multiple pesticide residues were identified. In soil (µg/kg), detection frequencies were 57.65% for chlorpyrifos, 14.12% for diazinon, 9.41% for lambda-cyhalothrin, 7.06% for pirimiphos-methyl, and 4.71% for cypermethrin. In well water samples (ppb), intended for human consumption or irrigation, detection rates were 41.03% for chlorpyrifos, 24.36% for cypermethrin, 23.08% for diazinon, 16.67% for pirimiphos-methyl, and 10.26% for lambda-cyhalothrin.

Chlorpyrifos was the most frequently detected compound in both matrices, with a mean concentration of 5.37 µg/kg in soil (range: 0.04–84.02 µg/kg) and 8.08 ppb in water (range: 0.04–61.57 ppb). This pattern suggests widespread environmental presence, likely associated with intensive agricultural and forestry activities in the area. In contrast, cypermethrin, diazinon, pirimiphos-methyl, and lambda-cyhalothrin showed limited occurrence. Their median and interquartile values were at or below the analytical LOD, indicating that quantifiable concentrations were uncommon and likely episodic.

Appendix 1 presents statistically significant negative correlations between residential distance to specific land uses and pesticide concentrations in environmental matrices. Negative Spearman’s rho coefficients indicate that shorter distances from those sources were associated with higher residue levels, particularly in water samples.

Chlorpyrifos in water showed the strongest and most consistent associations, with elevated concentrations near several forestry sites (Sites 2, 6, 7, and 8), vineyards (Sites 1 and 4), and cherry orchards. Correlation coefficients ranged from –0.255 to –0.431 (p < 0.01), supporting the hypothesis of contamination via aerial drift or surface runoff.

Cypermethrin in soil was associated with proximity to forestry Sites 3 and 8, and vineyard Site 2. In water, cypermethrin concentrations were correlated with distance from Sites 9 and Forestry Ce2. Diazinon was associated with both soil (Sites 5, forestry Ce1, and vineyard Sites 1 and 4) and water contamination (Sites 9, Forestry Ce1, Forestry Ce2, vineyards, and cherry orchards). Pirimiphos-methyl showed positive associations in both matrices near vineyard and forestry sites, and in water samples near cherry orchards. Lambda-cyhalothrin in water was associated with forestry Sites 6 and 7, vineyard Site 1, and cherry orchards, while its detection in soil was limited to Site 5.

Regarding non-occupational exposure, 69.0% of participants reported insecticide use inside their homes. This high prevalence suggests that indoor environments may represent a relevant exposure pathway, contributing to overall pesticide burden. According to participants, this practice is largely driven by the need to control high fly densities associated with odors, animal waste, and slurry from the nearby industrial pig facility. Among respondents, 90.5% stated that the survey item referring to pesticide use in household gardens was not applicable, suggesting that most participants do not manage such spaces or do not apply pesticides in them. Among the remaining individuals, 4.8% reported using sulfur, 2.4% biopesticides, and 2.4% pyrethroids, indicating limited but varied use in domestic cultivation.

Among those reporting indoor insecticide use, pyrethroids were the most frequently cited (48.8%), followed by combinations of organophosphates and pyrethroids (10.7%), and organophosphates alone (6.0%). A small proportion (2.4%) reported other insecticides, and 32.1% indicated that the question did not apply. These findings reflect a predominance of pyrethroid use in domestic contexts, consistent with their widespread commercial availability.

Significant differences in soil concentrations were found for cypermethrin (p = 0.041) and chlorpyrifos (p = 0.018) between households that reported indoor insecticide use and those that did not (

Table 3). In both cases, concentrations were lower in households that reported such use, with a more pronounced difference for cypermethrin. No statistically significant differences were observed in water concentrations of any pesticide according to this variable (all p > 0.05).

Regarding pesticide application in household gardens, only diazinon in soil showed statistically significant variation across application types (p = 0.018), with higher levels detected in households that did not apply any pesticides. For water samples, no statistically significant differences were found, although the comparison for chlorpyrifos approached significance (p = 0.063).

When considering the type of insecticide used inside the household, significant differences in water concentrations were observed for diazinon (p = 0.042), pirimiphos-methyl (p = 0.004), and lambda-cyhalothrin (p = 0.012). In all three cases, higher concentrations were found in households reporting the use of both organophosphates and pyrethroids. Diazinon in soil was significantly elevated among households that did not report the use of synthetic insecticides (p = 0.018).

These findings suggest possible associations between household and garden pesticide practices and the presence of residues in environmental matrices. However, multivariable analysis is needed to evaluate these associations while accounting for potential confounders.

Descriptive findings (

Table 4) reveal moderate to high levels of positive affect among participants (mean = 36.48, SD = 6.92 on a 10–50 scale), and comparatively low levels of negative affect (mean = 17.18, SD = 7.29), according to the PANAS scale.

Depressive symptoms assessed with the CES-D yielded a mean score of 14.64 (SD = 9.26), indicating variation in symptom severity across the sample, with some participants potentially exceeding the stablished clinical threshold.

Health-related quality of life, measured using the SF-12, showed moderate average scores for physical (mean = 46.53) and mental functioning (mean = 45.84), with wide standard deviations (both exceeding 28 points), reflecting substantial variability in self-perceived health status. The composite SF-12 score averaged 49.37, close to the midpoint of the scale, again with broad dispersion.

Psychological distress, as measured by the GHQ-12, showed a mean score of 2.98 (SD = 2.74), with values ranging from 0 to 11. This indicates that while a substantial portion of participants reported low distress, others presented elevated levels of psychological symptoms. Anxiety levels assessed by the STAI-S demonstrated marked variability, with a mean of 38.04, a median of 30, and a standard deviation of 27.2. Scores spanned from 1 to 95, revealing significant heterogeneity in acute anxiety at the time of assessment, potentially influenced by contextual or environmental conditions (

Table 5).

Correlation analyses revealed statistically significant associations between pesticide concentrations in environmental matrices and self-reported indicators of psychological and general health. Higher GHQ-12 scores, indicative of greater distress, were inversely associated with SF-12 scores for physical, mental, and overall functioning. Elevated anxiety scores (STAI-S) were positively correlated with both GHQ-12 scores and negative affect, reflecting coherence among the psychological indicators.

These findings suggest potential associations between environmental pesticide exposure and dimensions of mental health. Nonetheless, the cross-sectional design and the modest strength of associations call for longitudinal studies to better understand these patterns and their underlying determinants.

Elevated concentrations of lambda-cyhalothrin in well water were significantly associated with poorer self-perceived health, as reflected by negative correlations with physical health (ρ = −0.228, p = 0.047), mental health (ρ = −0.230, p = 0.044), and overall SF-12 scores (ρ = −0.252, p = 0.027). These associations suggest that increased environmental exposure to this pesticide may adversely influence individuals’ health perceptions. Additionally, cypermethrin levels in water were positively correlated with GHQ-12 scores (ρ = 0.304, p = 0.007), indicating a potential link with heightened psychological distress. Chlorpyrifos concentrations in water were also inversely associated with overall health functioning (SF-12 total score: ρ = −0.314, p = 0.005), further supporting the relationship between pesticide exposure and diminished health outcomes.

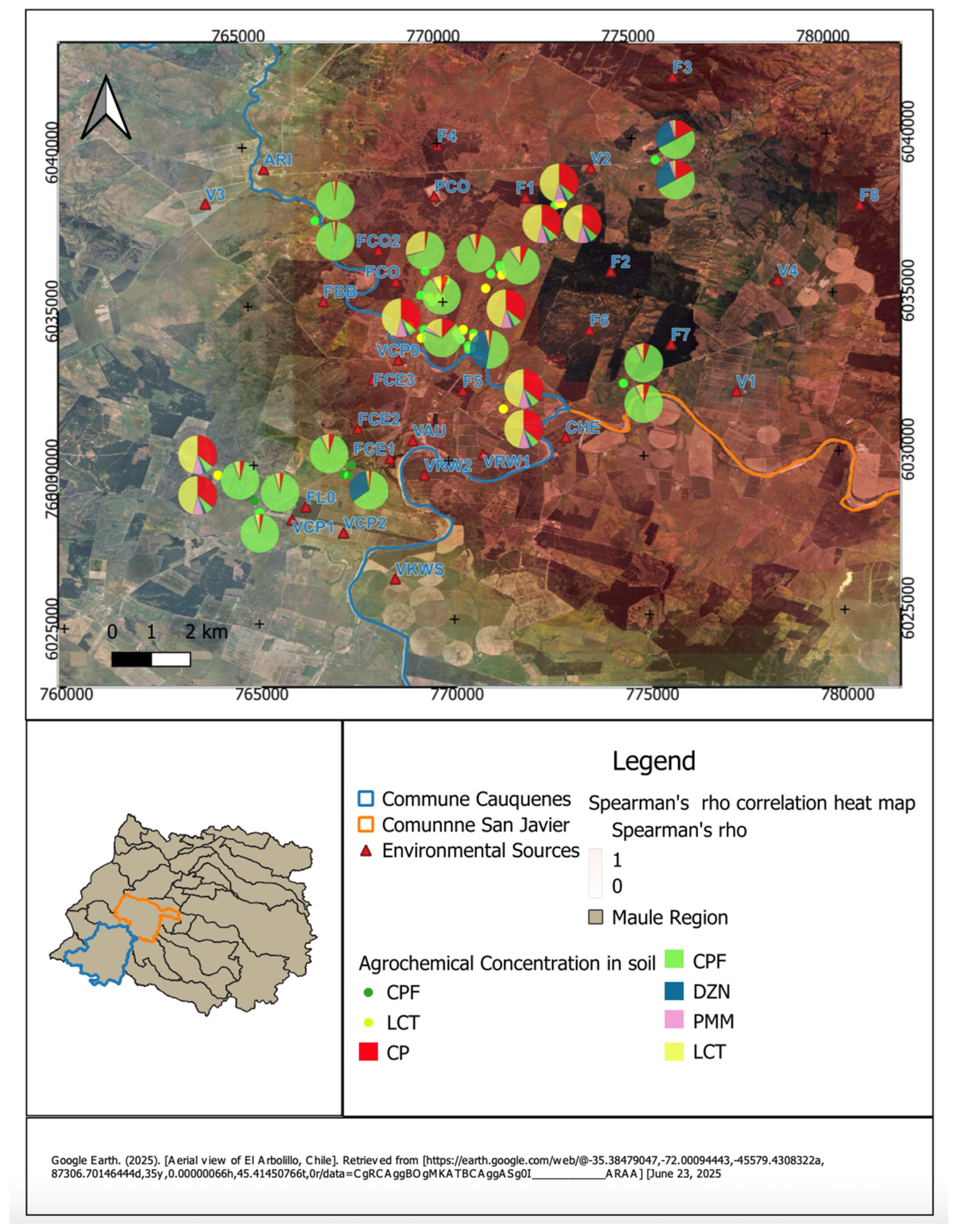

Figure 1 presents the spatial distribution of agrochemical residues in peridomestic soil samples from rural households in the communes of Cauquenes and San Javier, Maule Region. Each pie chart on the satellite map corresponds to a sampling site and shows the relative proportions of detected pesticides: chlorpyrifos (CPF), diazinon (DZN), pirimiphos-methyl (PMM), cypermethrin (CP), and lambda-cyhalothrin (LCT).

The distribution is spatially heterogeneous, with higher concentrations and more varied mixtures in areas located closer to identified environmental sources (indicated with red triangles). Households near agricultural or industrial facilities tend to present more complex pesticide profiles. The heatmap overlay, based on Spearman’s rho values, indicates the strength and direction of correlations between pesticide concentrations in soil and distance to these sources.

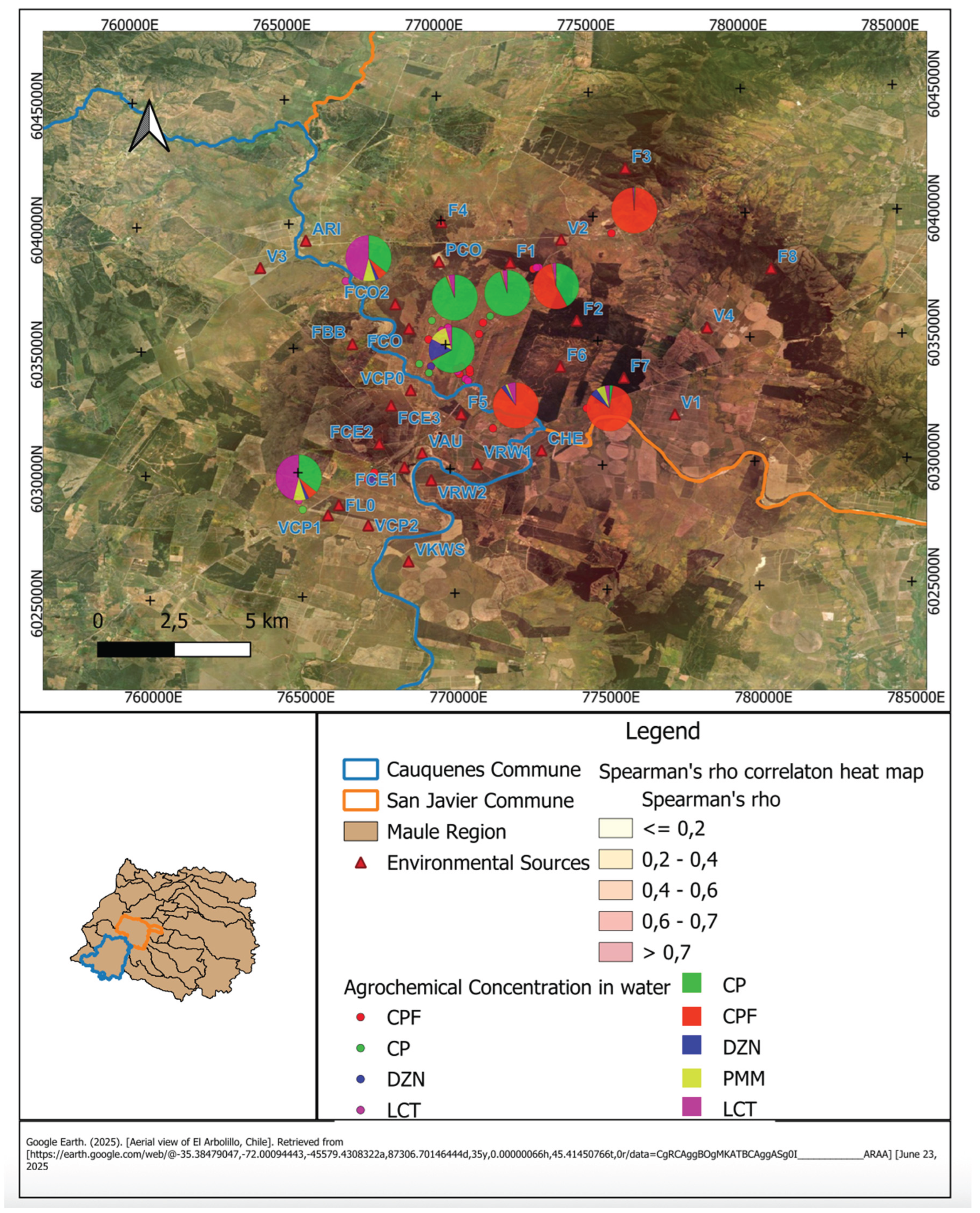

Figure 2 presents the spatial distribution of pesticide residues detected in well water samples from rural households in the communes of Cauquenes and San Javier, Maule Region. Each pie chart corresponds to a sampling site and illustrates the relative contribution of detected agrochemicals CPF, CP, DZN, PMM, and LCT.

The underlying heatmap represents Spearman’s rho values, reflecting the strength of the correlation between pesticide concentrations and residential proximity to environmental sources (marked with red triangles). Darker areas indicate stronger positive correlations (ρ > 0.7), while lighter areas denote weak or null associations (ρ ≤ 0.2).

The spatial distribution reveals that households situated closer to environmental sources tend to exhibit higher concentrations of chlorpyrifos and cypermethrin in water samples. This pattern suggests a geographic gradient of contamination, where proximity to agricultural or industrial activities contributes to increased presence of these compounds. In contrast, households located farther from such sources generally show lower residue levels, consistent with distance-based attenuation of environmental inputs.

Table 6 shows the results of robust multiple linear regression models examining associations between mental health and quality of life outcomes and selected sociodemographic and environmental pesticide exposure variables (n = 82).

Depressive symptoms (CES-D) were significantly associated with higher concentrations of cypermethrin and chlorpyrifos in water, and pirimiphos-methyl in soil. Cypermethrin in soil showed an inverse association with depressive symptoms, suggesting differential effects depending on the exposure route. Variables such as sex and chlorpyrifos in soil were not significant in this model.

For state anxiety (STAI-S), none of the pesticide variables showed significant associations. The only significant predictor was per capita income, with a positive relationship suggesting that higher income was linked to higher anxiety scores.

General psychological distress (GHQ-12) was positively associated with female sex and higher concentrations of cypermethrin in water, indicating that both factors may contribute to elevated distress levels.

Physical health (SF-12 Physical) was better among men and those with higher education, while poorer scores were observed in older participants and individuals with higher chlorpyrifos concentrations in water. BMI showed a marginal negative association. Mental health (SF-12 Mental) scores were positively associated with pirimiphos-methyl in soil, while lambda-cyhalothrin in soil and chlorpyrifos in water were negatively associated. Cypermethrin in water also approached significance, showing a potential negative relationship. Overall quality of life (SF-12 Total) was negatively associated with older age, BMI, lambda-cyhalothrin in soil, and chlorpyrifos in water. Higher scores were linked to male sex and higher education. Pirimiphos-methyl in soil showed a positive trend but was not statistically significant.

Positive affect (PANAS+) was higher among older participants but decreased with lower per capita income, longer residence time, and higher chlorpyrifos levels in soil. These patterns suggest a potential influence of prolonged exposure and socioeconomic conditions. No significant predictors were identified for negative affect (PANAS–), although longer residence and higher diazinon concentrations in soil and water showed non-significant associations.

In summary, these findings indicate that environmental exposure to specific pesticides, particularly chlorpyrifos, cypermethrin, pirimiphos-methyl, and lambda-cyhalothrin, is associated with a range of psychological and health indicators. These associations remain after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics, suggesting that pesticide exposure may play an important independent role in shaping mental health and well-being among rural populations.

Discussion

This study provides empirical evidence of associations between environmental pesticide exposure and psychological symptoms among rural populations who are not engaged in agricultural labor in the Maule Region of Chile. Unlike prior research conducted nationally [23,36,37], which has concentrated on occupational exposure in agricultural settings, our findings indicate that residents living near agroindustrial, forestry, or livestock operations may also experience environmental exposure and report psychological symptoms potentially related to environmental pesticide exposure.

Environmental analyses confirmed the presence of multiple pesticide compounds in soil and drinking water, with chlorpyrifos, cypermethrin, diazinon, and pirimiphos-methyl being most frequently detected. Higher concentrations of chlorpyrifos and cypermethrin were significantly associated with increased levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, psychological distress, and negative affect, as well as with lower scores in mental health-related quality of life. These findings are in line with previous studies linking chronic exposure to organophosphates and pyrethroids with neurobehavioral and affective disorders (Cancino et al., 2023; Landeros et al., 2022; Zúñiga-Venegas et al., 2022).

Depressive symptomatology showed heterogeneous associations with pesticide residues, depending on the chemical class and the environmental matrix. Organophosphates such as pirimiphos-methyl in soil and chlorpyrifos in water exhibited positive associations with depressive symptoms, while the relationship for cypermethrin varied by medium: positive in water, but inverse in soil. This divergence may indicate that higher concentrations in soil could correspond to lower current exposure due to environmental degradation, redistribution, or behavior-related distancing [39,40]. Furthermore, the simultaneous detection of organophosphates and pyrethroids in environmental samples indicates mixed exposures that may exert additive or antagonistic effects on mental health outcomes [41,42].

Previous research has documented that chronic or repeated exposure to organophosphates is linked to elevated risks of depression and other neurobehavioral alterations, especially in agricultural populations (Beseler et al., 2008; Cancino et al., 2023; Freire and Koifman, 2013)

Chlorpyrifos, in particular, has been mechanistically associated with inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neuroinflammation, all of which may interfere with neurotransmitter systems implicated in emotional regulation [16,18].

While previous reviews have highlighted associations between acute pesticide poisoning and depression, our results contribute to a growing body of research suggesting that chronic, low-level environmental exposure may also be linked to adverse psychological outcomes, even in the absence of clinical confirmed acute poisoning [17]. Similar results have been reported in Latin American studies that examined neuropsychological outcomes among populations living near pesticide-treated agricultural areas [10].

Spatial patterns observed in this study reinforce the importance of proximity to environmental sources. Households located closer to agricultural or industrial sites had higher concentrations of pesticides in soil and water. These results are consistent with established non-occupational exposure routes, including pesticide drift, infiltration into aquifers, and contact with contaminated surfaces. Previous research in the same region has shown elevated urinary metabolite levels of organophosphates in populations residing near crop fields [37], supporting the interpretation that distance from pesticide application areas is a key determinant of environmental exposure [46].

The use of Huber-IRLS regression in this study allowed for more robust estimates by minimizing the influence of extreme values, which is particularly relevant in environmental exposure data prone to skewed distributions [47]. Modeling psychological outcomes as continuous variables enhanced the capacity to detect exposure–effect gradients associated with pesticide concentrations in environmental matrices, reducing the risk of information loss from dichotomization or arbitrary cutoffs [48]. This analytic strategy strengthens the interpretation of subtle associations that may be diluted in categorical analyses. Furthermore, the psychological instruments applied were previously validated in Chile, supporting the cultural and psychometric appropriateness of the measures and improving the internal validity of the findings.

These findings have implications for environmental health surveillance. While earlier studies in the Maule Region have focused on occupational risk, the current data indicate that residents not working in agriculture but living in high pesticide-use areas may also face exposure-related risks (13,23,25,49,50). This aligns with regional literature describing the vulnerability of rural communities adjacent to intensive agricultural zones in Latin America.

The repeated detection of chlorpyrifos in environmental samples raises regulatory concerns. Despite growing international restrictions due to its neurotoxicity, this pesticide remains authorized in Chile [25]. Global health authorities have recommended phasing out highly hazardous pesticides as a preventive strategy. Evidence from countries that have implemented such measures suggests improvements in population mental health without detriment to agricultural productivity [51].

Using environmental matrices as indirect exposure indicators offers a viable alternative in resource-limited settings where biomonitoring is not feasible. Although individual biomarker data were not collected in this study, previous research in the region has shown correspondence between environmental pesticide levels and urinary biomarkers, suggesting that soil and water data can reflect meaningful exposure patterns at the community level.

Nonetheless, important limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design does not allow causal inference. Temporal dynamics of exposure and symptom development cannot be established, and reverse causality is possible. The absence of individual-level biomonitoring (biomarker measurement) restricts assessment of internal dose and interindividual metabolic variability. Moreover, the geographically localized sample limits generalizability to other rural contexts. The study also did not evaluate dietary intake, despite its relevance as a route of chronic pesticide exposure in rural populations. While self-reported data on household insecticide use were collected, these exposures were not fully incorporated into the statistical models, potentially contributing to residual confounding.

Finally, contextual variables such as perceived risk, support networks or health system access, which could modify the association between environmental exposure and mental health, were not regarded. Despite these limitations, the associations observed are supported by previous epidemiological research and are coherent with public health surveillance data documenting acute poisonings in the study region.

Future studies should adopt longitudinal designs to evaluate mental health trajectories under cumulative pesticide exposure. Including biomarkers such as urinary dialkyl phosphates and enhancing geospatial exposure modeling would improve exposure assessment. In addition, it is important to examine how contextual variables, including psychosocial stress, risk perception, and healthcare access, may influence the relationship between environmental exposure and mental health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Rocío Hojas, José Norambuena, América Ponce, Joaquín Toro, and Sebastián Pozo: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis. Jandy Adonis, Bárbara Figueroa, Francisca Cabezas, Cristian Valdés, Liliana Zúñiga-Venegas, Benjamín Castillo, Natalia Landeros, Boris Lucero, Ramón Castillo, Cynthia Carrasco, Juan Pablo Gutiérrez, Catalina Saavedra, Patricio Yáñez, María Ignacia Valdés, María Victoria Rodríguez, Andrés Canales-Johnson: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. María Teresa Muñoz-Quezada: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Software, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Validation.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgment

Funding for this study was provided by FONDECYT nº1240899 of the Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID) of the Chilean Government. The researchers gratefully acknowledge the support and collaboration of the organization Maule Sur por la Vida and the Regional Office of the National Institute for Human Rights (Instituto Nacional de Derechos Humanos, Región del Maule).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Barbosa Junior M, Ramos Huarachi DA, de Francisco AC. The link between pesticide exposure and suicide in agricultural workers: a systematic review. Rural and Remote Health. 2024;24:8190. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Preventing suicide: a resource for pesticides registrars and regulators [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2019 [cited 2025 Jan 30]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/326947/9789241516389-eng.pdf.

- Cancino J, Soto K, Tapia J, Muñoz-Quezada MT, Lucero B, Contreras C, et al. Occupational exposure to pesticides and symptoms of depression in agricultural workers. A systematic review. Environmental Research. 2023 Aug 15;231:116190.

- World Health Organization. Suicide worldwide in 2019: global health estimates [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2021 [cited 2025 Jan 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643.

- Rother HA. Pesticide suicides: what more evidence is needed to ban highly hazardous pesticides? The Lancet Global Health. 2021 Mar 1;9(3):e225–6.

- Coronado GD, Holte S, Vigoren E, Griffith WC, Barr DB, Faustman E, et al. Organophosphate Pesticide Exposure and Residential Proximity to Nearby Fields: Evidence for the Drift Pathway. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine [Internet]. 2011;53(8). Available from: https://journals.lww.com/joem/fulltext/2011/08000/organophosphate_pesticide_exposure_and_residential.10.aspx.

- Deziel NC, Friesen M, Hoppin Jane A., Hines CJ, Kent T, Freeman Laura E. Beane. A Review of Nonoccupational Pathways for Pesticide Exposure in Women Living in Agricultural Areas. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2015 June 1;123(6):515–24.

- Guzman-Torres H, Sandoval-Pinto E, Cremades R, Ramírez-de-Arellano A, García-Gutiérrez M, Lozano-Kasten F, et al. Frequency of urinary pesticides in children: a scoping review. Frontiers in Public Health [Internet]. 2023;Volume 11-2023. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1227337. [CrossRef]

- Lu C, Fenske RA, Simcox NJ, Kalman D. Pesticide Exposure of Children in an Agricultural Community: Evidence of Household Proximity to Farmland and Take Home Exposure Pathways. Environmental Research. 2000 Nov 1;84(3):290–302. [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga-Venegas L, Hyland C, Muñoz-Quezada MT, Quirós-Alcalá L, Butinof M, Buralli Rafael, et al. Health Effects of Pesticide Exposure in Latin American and the Caribbean Populations: A Scoping Review. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2022;130(9):096002.

- Ahmad MF, Ahmad FA, Alsayegh AA, Zeyaullah Md, AlShahrani AM, Muzammil K, et al. Pesticides impacts on human health and the environment with their mechanisms of action and possible countermeasures. Heliyon. 2024 Apr 15;10(7):e29128. [CrossRef]

- Tudi M, Li H, Li H, Wang L, Lyu J, Yang L, et al. Exposure Routes and Health Risks Associated with Pesticide Application. Toxics [Internet]. 2022;10(6). Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2305-6304/10/6/335. [CrossRef]

- Corral SA, de Angel V, Salas N, Zúñiga-Venegas L, Gaspar PA, Pancetti F. Cognitive impairment in agricultural workers and nearby residents exposed to pesticides in the Coquimbo Region of Chile. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2017 July 1;62:13–9. [CrossRef]

- Frengidou E, Galanis ,Petros, and Malesios C. Pesticide Exposure or Pesticide Poisoning and the Risk of Depression in Agricultural Populations: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Agromedicine. 2024 Jan 2;29(1):91–105.

- Farkhondeh T, Mehrpour O, Forouzanfar F, Roshanravan B, Samarghandian S. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in organophosphate pesticide-induced neurotoxicity and its amelioration: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2020 July 1;27(20):24799–814.

- Kori RK, Singh MK, Jain AK, Yadav RS. Neurochemical and Behavioral Dysfunctions in Pesticide Exposed Farm Workers: A Clinical Outcome. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry. 2018 Oct 1;33(4):372–81.

- Tsai YH, Lein PJ. Mechanisms of organophosphate neurotoxicity. Current Opinion in Toxicology. 2021 June 1;26:49–60.

- Zanchi MM, Marins K, Zamoner A. Could pesticide exposure be implicated in the high incidence rates of depression, anxiety and suicide in farmers? A systematic review. Environmental Pollution. 2023 Aug 15;331:121888.

- Muñoz-Quezada MT, Iglesias V, Zúñiga-Venegas L, Pancetti F, Foerster C, Landeros N, et al. Exposure to pesticides in Chile and its relationship with carcinogenic potential: a review. Frontiers in Public Health [Internet]. 2025;Volume 13-2025. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2025.1531751. [CrossRef]

- Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero. [General report on sales of agricultural pesticides in Chile. Agricultural and Forestry Protection Division. Food Safety Section]. [Internet]. Chile; 2023. Available from: https://www.sag.gob.cl/content/reporte-general-de-las-declaraciones-de-ventas-de-plaguicidas-ano-2023.

- Subsecretaría de Salud Pública. Epidemiological Situation of Acute Pesticide Poisonings in Chile – REVEP, 2011–2023. [Internet]. Santiago, Chile: Ministerio de Salud, Chile; 2025 p. 27. Available from: https://epi.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Informe_Epidemiologico_de_Intoxicaciones_agudas_por_plaguicidas_por_comunas_REVEP_2011_2023.pdf.

- Lucero B, Muñoz-Quezada MT, Canales-Johnson A, Carrasco C, Rodríguez MV, Reid T, et al. Biomarkers of pesticide exposure predict Depressive Symptoms in rural and urban workers of the Maule Region, Chile. medRxiv. 2025 Jan 1;2025.01.30.25321387.

- Ramírez-Santana M, zúñiga-Venegas L, Corral S, Groenewoud H, Van der Velden K, Sheepers PTJ, et al. Association between cholinesterase’s inhibition and cognitive impairment: A basis for prevention policies of environmental pollution by organophosphate and carbamate pesticides in Chile. 2020 Apr 8;186(109539). [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Quezada MT, Pasten P, Landeros N, Valdés C, Zúñiga-Venegas L, Castillo B, et al. Bioethical Analysis of the Socio-Environmental Conflicts of a Pig Industry on a Chilean Rural Community. Sustainability. 2024;16(13).

- Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders M. AUDIT The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Guidelines for Use in Primary Care [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2001. Available from: https://www.paho.org/sites/default/files/Auditmanual_ENG.pdf.

- Santana-Mayor Á, Socas-Rodríguez B, Herrera-Herrera AV, Rodríguez-Delgado MÁ. Current trends in QuEChERS method. A versatile procedure for food, environmental and biological analysis. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2019;116:214–35.

- Ðurović-Pejčev RD, Bursić VP, Zeremski TM. Comparison of QuEChERS with Traditional Sample Preparation Methods in the Determination of Multiclass Pesticides in Soil. Journal of AOAC INTERNATIONAL. 2019 Jan 1;102(1):46–51. [CrossRef]

- Łozowicka B, Rutkowska E, Jankowska M. Influence of QuEChERS modifications on recovery and matrix effect during the multi-residue pesticide analysis in soil by GC/MS/MS and GC/ECD/NPD. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2017 Mar 1;24(8):7124–38.

- Gempp R, Thieme C. Effect of different scoring methods on the reliability, validity, and cut points of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Terapia psicologica. 2010 July;28:5–12.

- Vera-Villarroel P, Urzúa A, Jaime D, Contreras D, Zych I, Celis-Atenas K, et al. Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): psychometric properties and discriminative capacity in several Chilean samples. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2019;42(4):473–97.

- Garmendia ML. Análisis factorial: Una aplicación en el cuestionario de salud general de Goldberg, version de 12 preguntas. Revista Chilena de Salud Pública. 2007;11(2):57–65.

- Martinez MP, Gallardo I. Evaluacion de la confiabilidad y validez de constructo de la Escala de Calidad de Vida en Salud SF-12 en poblacion chilena (ENCAVI 2015-6). Revista Medica de Chile. 2020 Nov;148:1568–76. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Quezada MT, Lucero B, Bradman A, Baumert B, Iglesias V, Muñoz MP, et al. Reliability and factorial validity of a questionnaire to assess organophosphate pesticide exposure to agricultural workers in Maule, Chile. International Journal of Environmental Health Research. 2019;29(1):45–59. [CrossRef]

- Soto-Brandt G, Portilla Huidobro R, Huepe Artigas D, Rivera-Rei A, Escobar M, Salas Guzmán N, et al. [Validity evidence of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in Chile]. Adicciones. 2014;26(4):291–302.

- Muñoz-Quezada M, Lucero B, Iglesias V, Levy K, Muñoz MP, Acú E, et al. Exposure to organophosphate (OP) pesticides and health conditions in agricultural and non-agricultural workers from Maule, Chile. Environmental Research. 2017 Feb;27(1):82–93.

- Ramírez-Santana M, Farías-Gómez C, Zúñiga-Venegas L, Sandoval R, Roeleveld N, Van der Velden K, et al. Biomonitoring of blood cholinesterases and acylpeptide hydrolase activities in rural inhabitants exposed to pesticides in the Coquimbo Region of Chile. PLOS ONE. 2018 May 2;13(5):e0196084. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt P, Huang Y, Zhan H, Chen S. Insight Into Microbial Applications for the Biodegradation of Pyrethroid Insecticides. Frontiers in Microbiology [Internet]. 2019;Volume 10-2019. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01778.

- Qin S, Budd R, Bondarenko S, Liu W, Gan J. Enantioselective Degradation and Chiral Stability of Pyrethroids in Soil and Sediment. J Agric Food Chem. 2006 July 1;54(14):5040–5.

- Eve L, Fervers B, Le Romancer M, Etienne-Selloum N. Exposure to Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals and Risk of Breast Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020;21(23). [CrossRef]

- Savitz D, Hattersley A. Evaluating Chemical Mixtures in Epidemiological Studies to Inform Regulatory Decisions. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2023;131(4):045001.

- Beseler C, Stallones L, Hoppin J, Alavanja M, Blair, Keefe T, et al. Depression and Pesticide Exposures among Private Pesticide Applicators Enrolled in the Agricultural Health Study. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2008 Dec 1;116(12):1713–9. [CrossRef]

- Freire C, Koifman S. Pesticides, depression and suicide: A systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2013 July 1;216(4):445–60.

- Muñoz-Quezada M, Lucero BA, Gutierrez-Jara JP, Buralli RJ, Zúñiga-Venegas L, Muñoz MP, et al. Longitudinal exposure to pyrethroids (3-PBA and trans-DCCA) and 2,4-D herbicide in rural schoolchildren of Maule region, Chile. Science of the Total Environment. 2020 Dec;749:141512.

- Varin S, Panagiotakos DB. A review of robust regression in biomedical science research. Arch Med Sci. 2020;16(5):1267–9. [CrossRef]

- Royston P, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W. Dichotomizing continuous predictors in multiple regression: a bad idea. Statistics in Medicine. 2006 Jan 15;25(1):127–41. [CrossRef]

- Landeros N, Duk S, Márquez C, Inzunza B, Acuña-Rodríguez IS, Zúñiga-Venegas LA. Genotoxicity and Reproductive Risk in Workers Exposed to Pesticides in Rural Areas of Curicó, Chile: A Pilot Study. IJERPH. 2022 Dec 10;19(24):16608.

- Zúñiga-Venegas L, Pancetti FC. DNA damage in a Chilean population exposed to pesticides and its association with PON1 (Q192R and L55M) susceptibility biomarker. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis. 2022 Apr 1;63(4):215–26.

- Steinmetz J, Seeher K, Schiess N, Nichols E, Cao B, Servili C, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet Neurology. 2024 Apr 1;23(4):344–81.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).