1. Introduction

Iron (Fe) and steel production have rapidly increased since the 20th century by the development of the global economy because Fe is a fundamental commodity. For example, the global pig Fe and steel production in 2023 exceeded 1.3 billion tonnes (Bt) and 1.8 Bt, respectively [

1,

2]. Owing to the increase in Fe and steel production, the generation of by-products, such as dust, has increased as well. Most of the dust is directly recycled as raw material for blast furnaces. However, electric arc furnace (EAF) dust is not directly recycled owing to its high zinc (Zn) concentration [

3]. Currently, EAF dust is recycled using Waelz Kiln or Rotary Hearth Furnace (RHF) process. In these processes, Zn (

g) and Fe (

s) are recovered through the reduction of EAF dust using carbon (C) at temperatures above 1273 K, thus resulting in carbon monoxide (CO) and/or carbon dioxide (CO

2) gas emission. Therefore, considering the environmental burden from current processes, the development of a CO

2-free method for recycling EAF dust is paramount in the near future.

In the Fe industry, various technologies have been developed to mitigate CO

2 gas emission. Among these technologies, the important approach involves changing the reducing agent from coke to hydrogen (H

2) gas or electron [

4]. The use of green H

2 gas enables the CO

2-free production of Fe. However, the green H

2 gas is produced by water electrolysis. Therefore, the direct use of electrons as reducing agents for Fe metal production provides the advantage of simplifying the production process.

Several studies have been conducted on the electrolysis of Fe oxides, as shown in

Table 1. Depending on the supporting electrolyte used, electrolysis using molten oxide, molten salt, molten carbonate, and molten hydroxide were investigated. Among the various electrolysis methods, molten oxide electrolysis is a promising method because of the high solubility of oxide feedstocks and the direct use of oxide feeds without any pre-treatment, such as sintering or pelletizing. Many studies have reported the results of molten oxide electrolysis at high temperatures such as approximately 1700 K, as shown in

Table 1. However, operation at such high temperatures results in higher energy consumption compared with other electrolytic processes that use molten salt, carbonate, or hydroxide.

To decrease the energy consumption of molten oxide electrolysis, the low-temperature molten oxide electrolysis of hematite (Fe

2O

3) using a boron oxide (B

2O

3) – sodium oxide (Na

2O) electrolyte was investigated [

11]. When the electrolysis of Fe

2O

3 was conducted in B

2O

3 – Na

2O at 1273 K by applying 1.4 – 2 V, Fe metal was obtained with the current efficiency of 32.3 – 54.7 %. The use of the B

2O

3 – Na

2O electrolyte retains the advantages of the molten oxide electrolysis process, such as sufficient solubility of Fe

2O

3 even at moderate operating temperatures.

However, investigations of electrolytic methods using EAF dust to recover Fe and Zn have rarely been reported, as shown in

Table 1. Liu

et al. performed the electrolysis of ZnFe

2O

4 generated during Zn metallurgy instead of EAF dust in sodium chloride (NaCl) – calcium chloride (CaCl

2) molten salt at 1073 K [

19]. It was reported that ZnFe

2O

4 undergoes stepwise reduction, with Fe being reduced prior to Zn. Although this process can be used for recycling EAF dust, treating chloride salts is challenging because the environment of the electrolytic process tends to be corrosive owing to their hygroscopicity.

Low-temperature molten oxide electrolysis becomes an alternative method for recovering Fe and Zn from EAF dust. Molten oxide electrolysis offers a safer and more stable environment during electrolysis compared with chloride-based molten salt systems. In addition, Zn and Fe are recovered from EAF dust without CO

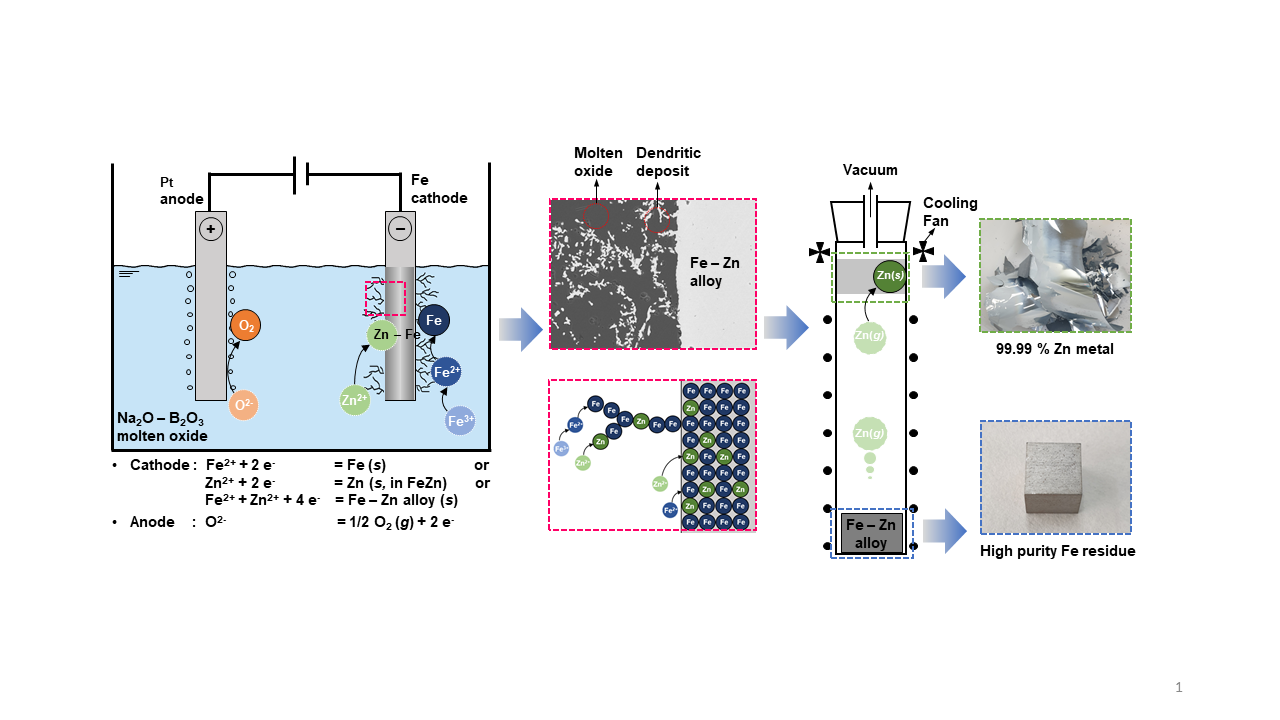

2 gas emission by using an inert anode. Based on these advantages, as shown in

Figure 1, a fundamental investigation of the electrochemical behavior of Fe and Zn oxides and their electrolysis at 1173 K was conducted using low-temperature molten oxide electrolysis to develop a novel and environmentally friendly method for recycling EAF dust.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) of Fe2O3 and ZnO in B2O3 – Na2O Molten Oxide

To investigate the electrochemical behavior of Fe2O3 and ZnO in B2O3 – Na2O molten oxide at 1173 K, CV measurements were conducted. Prior to the experiments, Na2O (purity: >97.5 %; Thermo Fisher Scientific Chemicals, Inc.) was dried in vacuum oven (Model: VOS-602 SD, EYELA) at 453 K for more than 24 h, and subsequently it was stored in a glove box (Model: MB-200MOD, MBRAUN) to prevent hydration by atmospheric moisture.

An oxide mixture of 71 mass% B2O3 (purity: 99.98 %; Thermo Fisher Scientific Chemicals, Inc.) – 26 mass% Na2O – 3 mass% Fe2O3 (purity: 99.9 %; Thermo Fisher Scientific Chemicals, Inc.) and a mixture of 71 mass% B2O3 – 26 mass% Na2O – 1.5 mass% Fe2O3 – 1.5 mass% ZnO (purity: 99.99 %; Thermo Fisher Scientific Chemicals, Inc.) were prepared at a room temperature. The oxide mixture was then placed in an alumina (Al2O3) crucible (O.D. = 56 mm, thickness (t) = 3.5 mm).

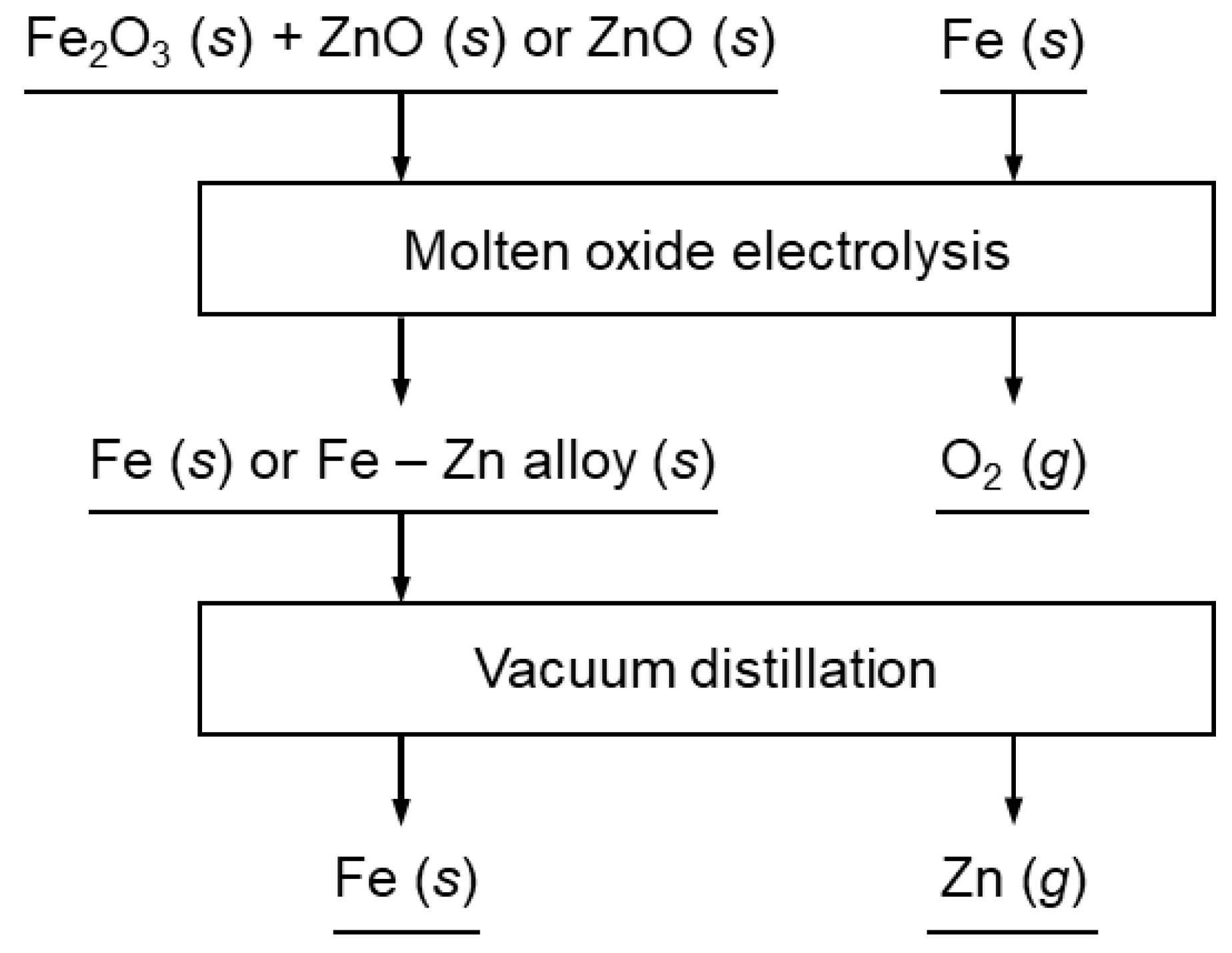

Figure 2 (a) shows a schematic of the electrolytic cell used for the CV measurement (

see Figure S-1 in the supplementary material for a photograph of the apparatus). As shown in

Figure 2 (a), the Al

2O

3 crucible containing the oxide mixture was placed in an electric furnace. Subsequently, the temperature was increased to 1173 K for the CV measurements.

In this study, platinum (Pt) wire (purity: 99.95 %; diameter (ϕ) = 0.5 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific Chemicals, Inc.) was used as both the working and counter electrodes whereas molybdenum (Mo) wire (purity: 99.95 %; ϕ = 0.5 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific Chemicals, Inc.) was used as the quasi-reference electrode. In addition, an identical Mo wire was used as a potential lead for all electrodes. The electrodes and the Mo potential lead were hand-polished before the experiment. After electrical connection between electrode and potential lead, the potential leads of working electrode and quasi-reference electrode were diagonally inserted into two holes of an Al2O3 tube (O.D. = 8.5 mm) with four holes (ϕ = 1.8 mm). In addition, the potential lead of the counter electrode was inserted into a hole in an identical Al2O3 tube. The end of the potential lead connected to the potentiostat was bent and secured with Teflon tape to prevent electrode movement. Subsequently, the prepared Al2O3 tubes were inserted into the furnace through two holes in the lid and fixed in position using clamps. The prepared electrodes were immersed in the molten oxide, and CV measurements were conducted using a potentiostat (Model: SP-150e, booster: VMP3B, 2 A – 20 V, Biologic Science Instruments).

2.2. Molten Oxide Electrolysis of Fe2O3 and ZnO Using Fe Cathode

Before the experiments, Na

2O was dried in a vacuum oven at 453 K for more than 24 h and subsequently stored in a glove box. 3.0 g of the Fe

2O

3 – ZnO mixture with a predetermined composition in

Table 2 was mixed with 97.0 g of an oxide mixture containing 73 mass% B

2O

3 – 27 mass% Na

2O. The prepared oxide mixture was then placed in an Al

2O

3 crucible, which was then placed in an electric furnace. Subsequently, the temperature was increased to 1173 K and maintained for 3 h prior to electrolysis.

Figure 2 (b) shows a schematic of the experimental apparatus used for the molten oxide electrolysis. Fe wire (purity: 99.99 %;

ϕ = 1 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific Chemicals, Inc.) was used as the cathode, and Pt foil (purity: 99.9 %; length (

l) = 20 mm, width (

w) = 3 mm,

t = 0.127 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific Chemicals, Inc.) was used as the anode. A Mo wire was used as the potential lead for connecting the electrode and potentiostat. The electrodes and the Mo potential lead were hand-polished before use. Each potential lead, which was assembled with an electrode was inserted into a separate Al

2O

3 tube. The end of the potential lead connected to the potentiostat was bent and secured using Teflon tape. Subsequently, the prepared Al

2O

3 tubes were inserted into the furnace through two holes in the lid and fixed in position using clamps. The prepared electrodes were immersed in the molten oxide and chronoamperometry was performed in the range of 1.1 – 1.6 V at 1173 K. After electrolysis was completed, the electrodes were removed from the molten oxide. Subsequently, the temperature was decreased to room temperature and the cathode was retrieved for analysis.

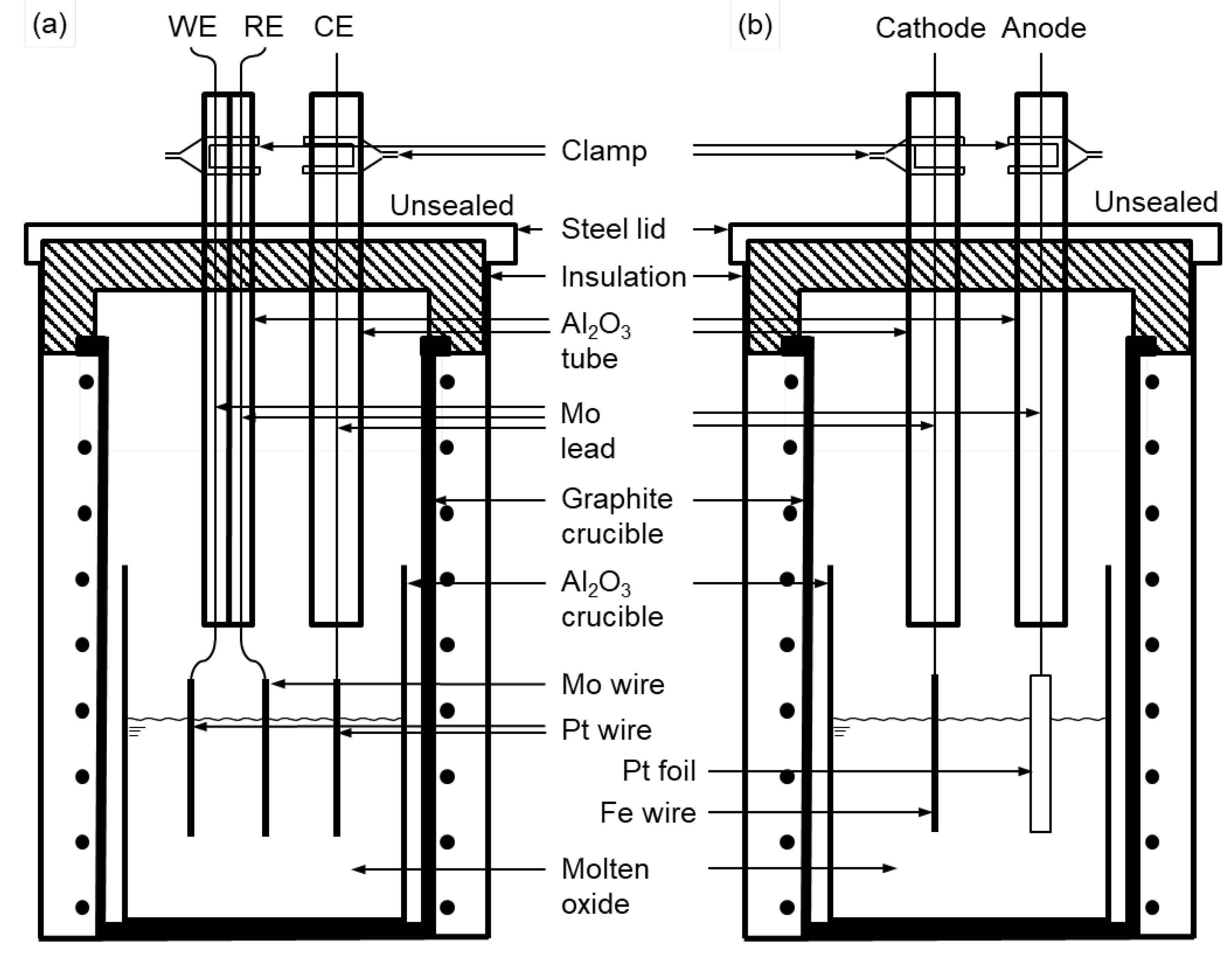

2.3. Vacuum Distillation of Fe - Zn Alloys

Figure 3 shows a schematic and photograph of the experimental apparatus used for vacuum distillation. Fe – 27.1 mass% Zn alloy (

l = 10 mm,

w = 10 mm,

t = 10 mm; RND KOREA Corp.) was placed in a small Al

2O

3 crucible (O.D. = 40 mm,

t = 2 mm), which was then placed in another Al

2O

3 crucible (O.D. = 50 mm,

t = 2 mm), with titanium (Ti) sponge packed at the bottom to absorb the residual O in the atmosphere at elevated temperatures. Subsequently, the assembly was positioned at the bottom of the quartz reactor (O.D. = 61 mm,

t = 3 mm, height (

h) = 650 mm).

After a Viton plug equipped with Pyrex tubes as the inlet and outlet was plugged into the top of the reactor, the reactor was evacuated and refilled with argon (Ar, purity = 99.999 %) gas twice to control the atmosphere. After the final filling Ar gas, the reactor was continuously evacuated using a rotary pump until the end of the experiment.

The reactor was placed in a furnace preheated to 1200 K for the vacuum distillation of Fe – Zn alloy for 1 – 12 h. After vacuum distillation, the reactor was immediately removed from the furnace and cooled to room temperature. The residue at the bottom of the crucible and the deposit on the inner wall of the reactor were recovered for analysis.

2.4. Analysis

The microstructures and compositions of the samples were analyzed using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM: GeminiSEM 560, Carl Zeiss AG.) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The crystalline phases of samples were identified using X-ray diffractometer (XRD: SmartLab, Rigaku Corporation, Cu-Kα radiation). The compositions of the samples were analyzed using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES: 5800 ICP-OES, AGILENT).

3. Mechanism of the Electrolysis of Fe2O3 and ZnO in Molten B2O3 – Na2O

In this study, to produce metallic Fe or Fe – Zn alloy from Fe

2O

3 and ZnO, electrolysis in molten B

2O

3 – Na

2O using an Fe cathode and a Pt anode was investigated. To understand the electrolysis mechanism of Fe

2O

3 and ZnO, the FactSage thermodynamic software (FactSage 8.3 version;

www.factsage.com) was employed. In particular, the FTOxid database containing the optimized data of the Fe

2O

3– B

2O

3 – Na

2O and ZnO – B

2O

3 – Na

2O systems [

26,

27] and the FSStel database for the Fe-Zn alloy were utilized in the FactSage calculations.

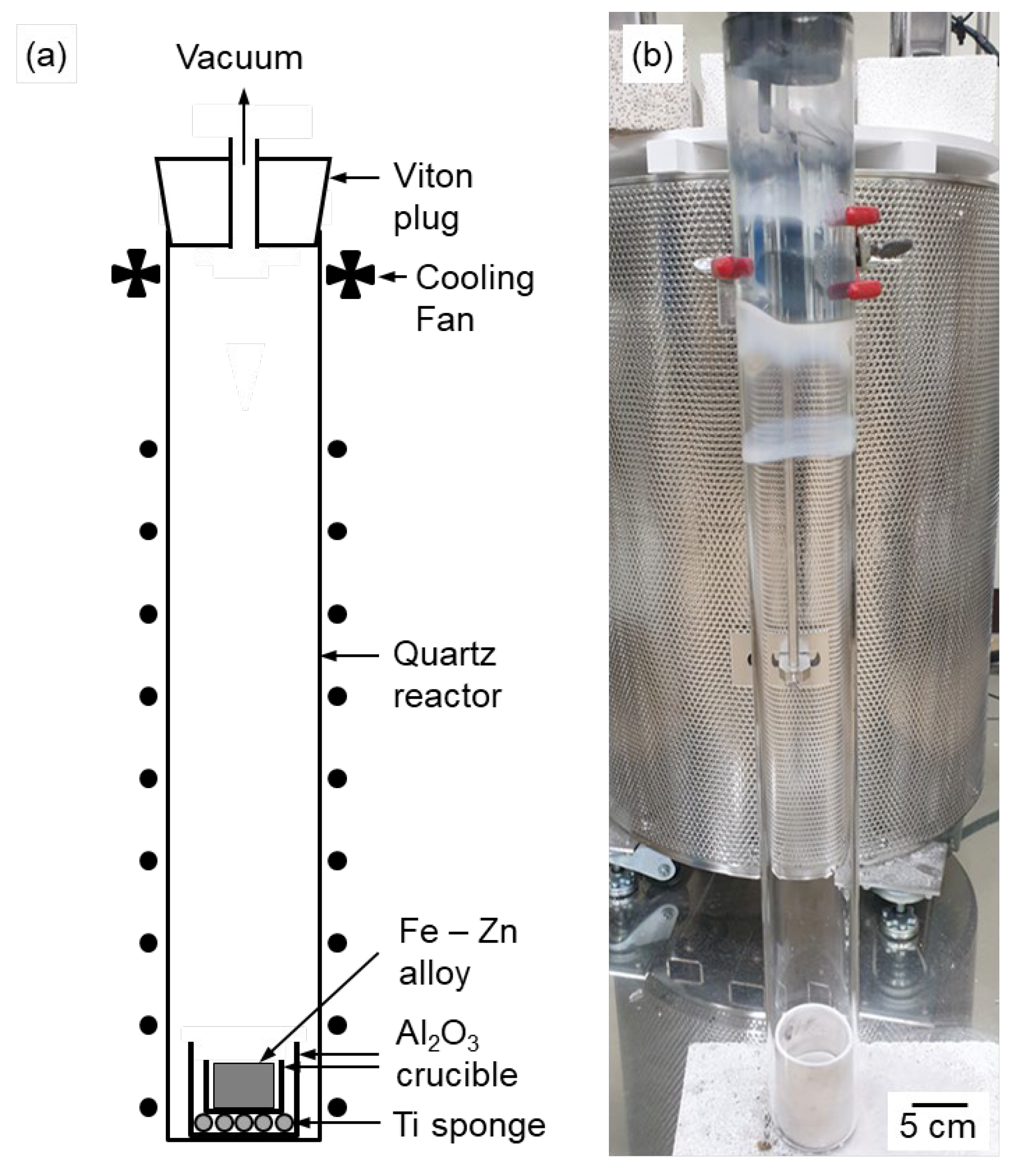

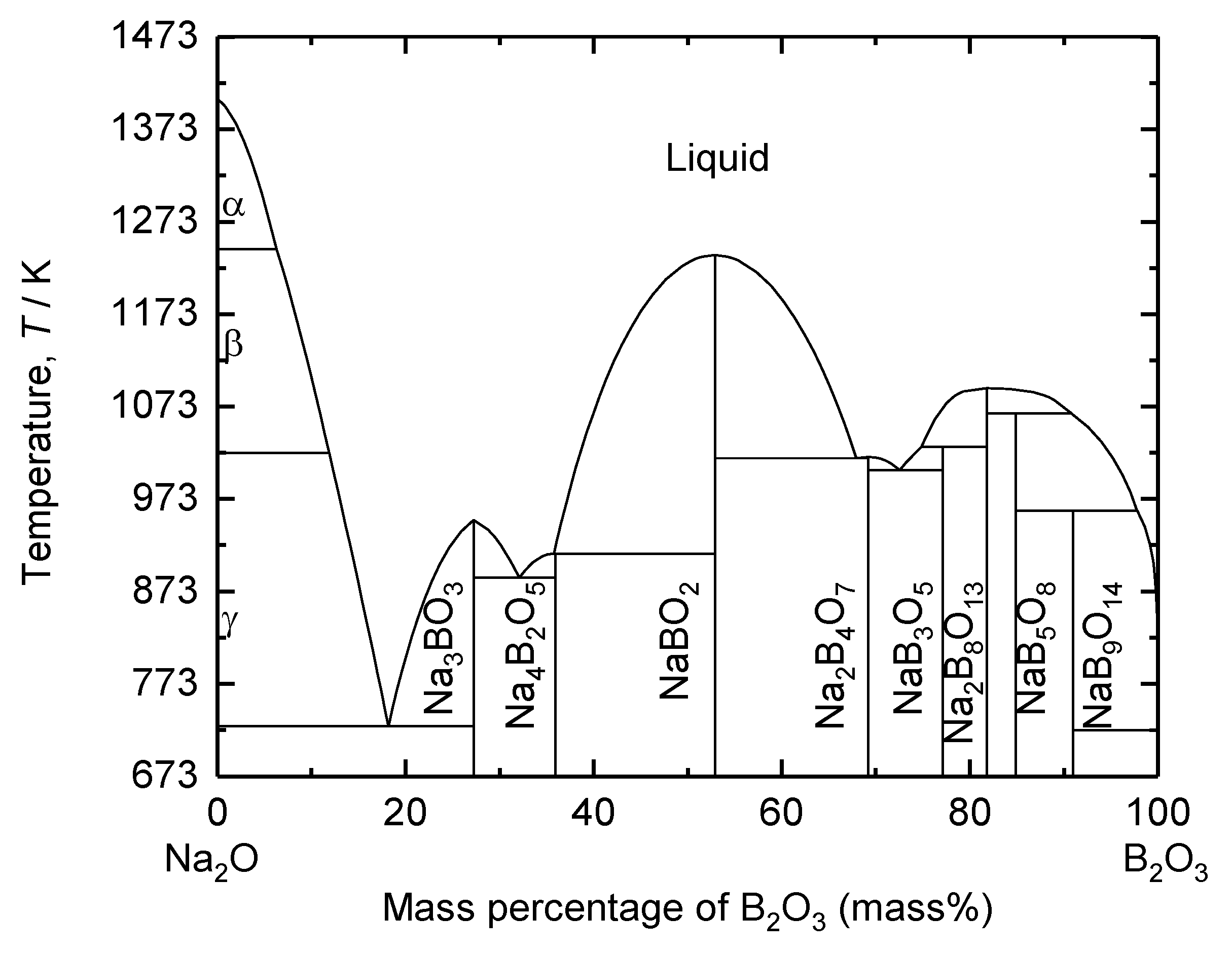

The composition of the supporting electrolyte was determined based on the binary phase diagram of B

2O

3 – Na

2O shown in

Figure 4. As shown in

Figure 4, eutectic compositions of this system are calculated at 73 mass%, 32 mass%, and 18 mass% B

2O

3. Na

2O is a network modifier to break down B

2O

3 network structure in a borate melt, which leads to an increase in electrical conductivity [

28,

29,

30]. However, Kim

et al. showed that an increased amount of Na

2O in molten oxides causes an increase in the basicity of molten oxides, thereby leading to the corrosion of iridium (Ir)-based inert anode [

31]. Therefore, 73 mass% B

2O

3 – Na

2O was determined as a supporting electrolyte in this study.

The eutectic temperature of 73 mass% B

2O

3 – Na

2O is 1004 K (see in

Figure 4). Therefore, for the stable operation of electrolyte considering the composition and temperature fluctuation at scaled-up process in future, the electrolysis temperature in this study was determined to be 1173 K.

The solubilities of Fe

2O

3 and ZnO in molten B

2O

3 – Na

2O at 1173 K were calculated using the FactSage, and they are 11.7 mass% and 4.4 mass%, respectively. Consequently, the maximum concentration of ZnO added to 73 mass% B

2O

3 – Na

2O was determined to be 3 mass% in this study. The sample compositions used in this study are listed in

Table 2.

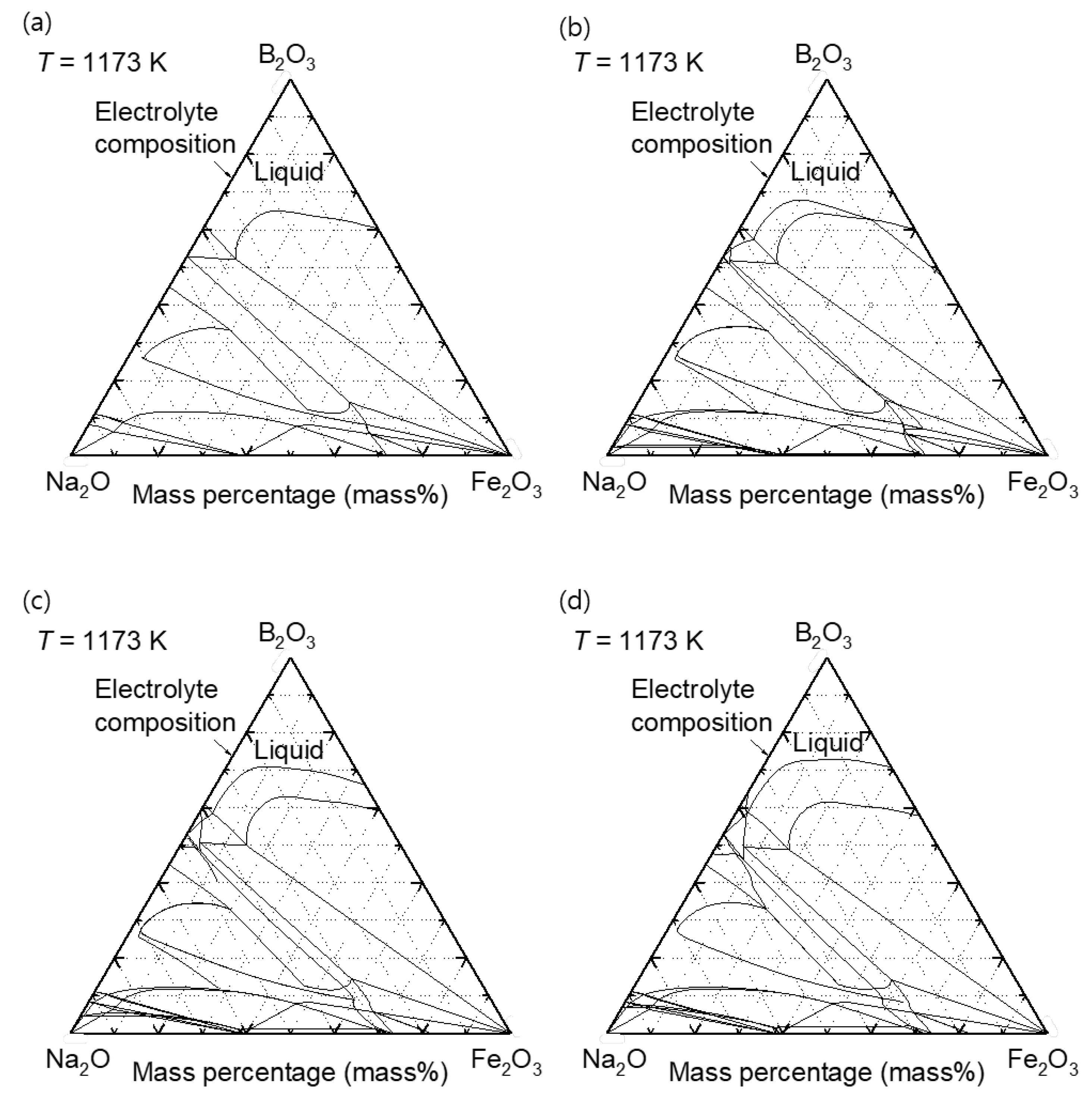

Figure 5 shows the iso-composition plane of the quaternary phase diagram of the B

2O

3 – Na

2O – Fe

2O

3 – ZnO system at 1173 K with 0 mass%, 1 mass%, 2 mass%, and 3 mass% ZnO content. According to the calculated phase diagrams in

Figure 5, all the samples are in fully liquid states.

Table 3 shows the theoretical standard decomposition voltages of selected oxides at 1173 – 1373 K. Na

2O and B

2O

3 are more stable than the other oxides owing to their higher decomposition voltages. The reduction of Fe

2O

3 and ZnO proceeds in the following order: Fe

2O

3 to wüstite (FeO), FeO to metallic Fe, and ZnO to liquid Zn. However, because the actual electrolytic process does not proceed under the standard state, it is necessary to consider the activities of oxides in actual electrolyte melt and metals at the Fe cathode to accurately estimate the decomposition voltages of all species involved during electrolysis at 1173 K. For this purpose, FactSage thermodynamic calculations were performed.

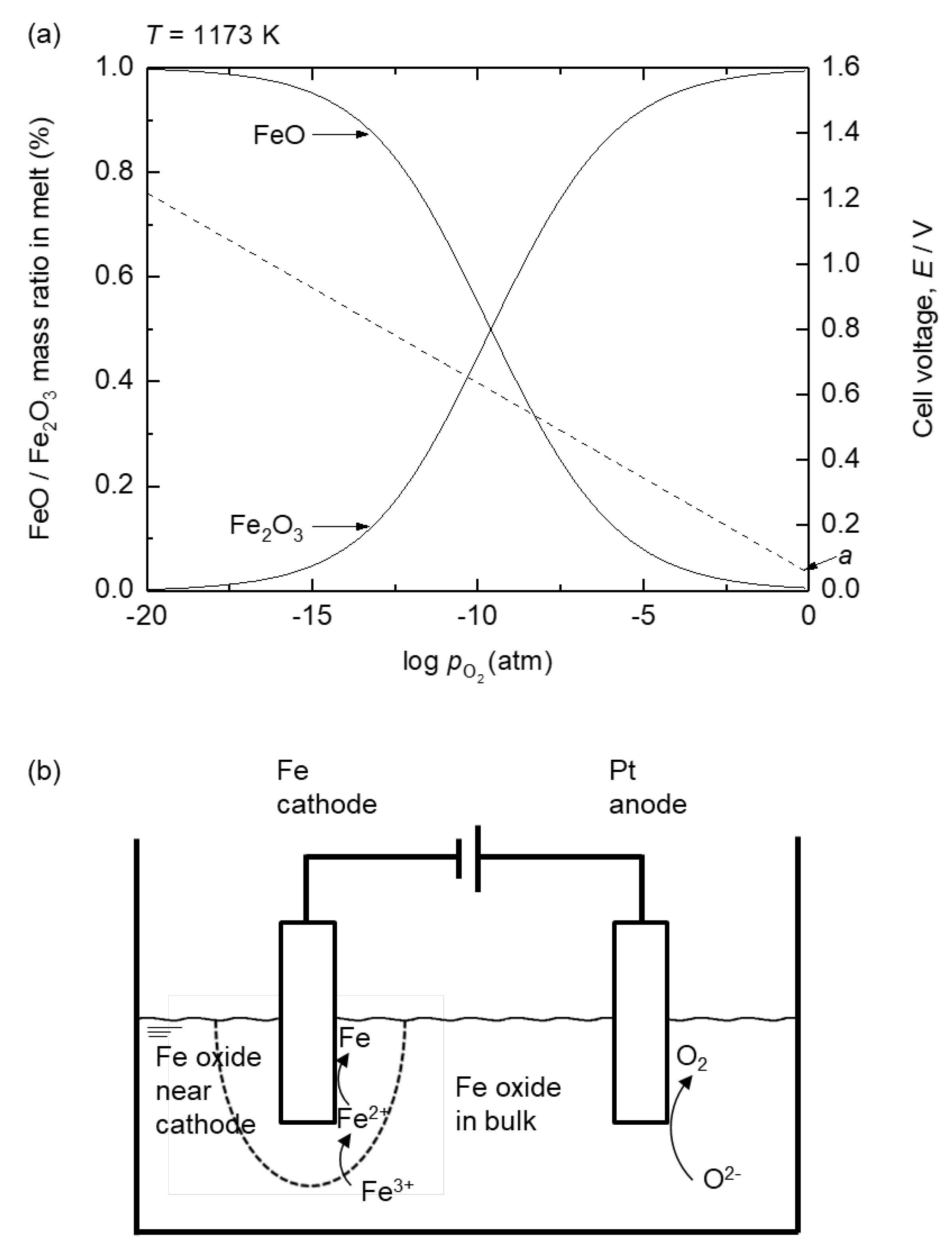

In the case of Fe, trivalent (Fe

3+) and divalent (Fe

2+) ions are present in the oxide melt. To calculate the decomposition voltages of Fe

2O

3 and FeO, their activities in the melt must be considered.

Figure 6 (a) shows the variation of Fe

2O

3 and FeO in 73 mass% B

2O

3 – Na

2O electrolyte at 1173 K as a function of oxygen partial pressure (

pO2). Using the Nernst equation, the cell voltage required for the reduction of Fe

2O

3 to FeO at each oxygen partial condition was calculated and plotted in

Figure 6 (a). As shown in

Figure 6 (a), Fe

3+ and Fe

2+ are dominant at high

pO2 and low

pO2, respectively. During electrolysis, reducing conditions are formed near the cathode, corresponding to a low

pO2, whereas oxidizing conditions are formed near the anode by O

2 gas evolution, corresponding to a high

pO2. Therefore, as electrolysis proceeds, Fe

2+ mainly exists near the cathode, followed by the reduction of Fe

3+ to Fe

2+, whereas Fe

3+ will mainly exists near the anode, as shown in

Figure 6 (b).

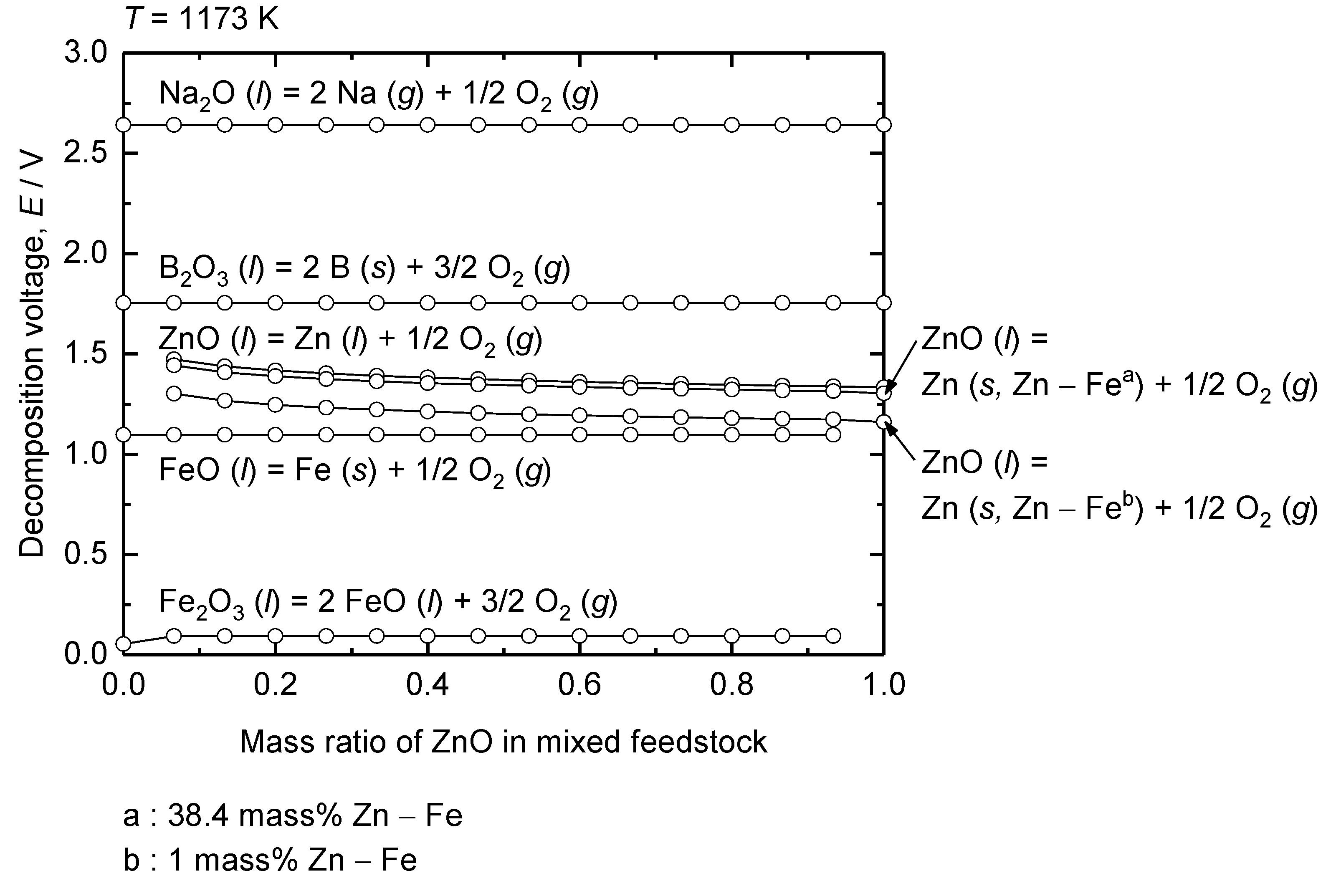

Figure 7 shows the estimated decomposition voltages of Fe

2O

3, FeO, ZnO, B

2O

3, and Na

2O from the Nernst equation, by considering their activities under the conditions used in this study at 1173 K as a function of the mass ratio of ZnO in the Fe

2O

3 – ZnO mixed feed. Before the electrolysis, Fe

2O

3 is dominant over FeO because the Fe

2O

3 – ZnO – B

2O

3 – Na

2O system is in equilibrium with air (

pO2 = 0.21 atm) at 1173 K. When the onset of the electrolysis near cathode is considered, the estimated decomposition voltage for reduction of Fe

2O

3 to FeO decreases from 0.74 V under the standard state to approximately 0.05 – 0.09 V because of the significantly low

aFeO in the melt.

The decomposition voltage for the reduction of FeO to metallic Fe was calculated by considering the activity of Fe as unity owing to the formation of pure metallic Fe (

s). Accordingly, the decomposition voltage is governed by

aFeO, which is directly affected by FeO concentration near the cathode. Because the decomposition voltage for the reduction of Fe

2O

3 at the onset of electrolysis is considerably low as shown in

Figure 7, Fe

2O

3 will be reduced to FeO prior to the reduction of FeO to metallic Fe. This results in the accumulation of FeO near the cathode, leading to a gradual increase in its concentration, until it is reduced to metallic Fe.

The equilibrium pO2 for Fe (s) / FeO (l, in melt) Equation under the experimental conditions is 10-18 atm at 1173 K. Therefore, the activity of the existing state of Fe oxides such as aFeO and aFe2O3 before the reduction of FeO to metallic Fe is determined by FeO (l, in melt) / Fe2O3 (l, in melt) Equation under pO2 = 10-18 atm. The resulting decomposition voltage estimated using aFeO was calculated to be approximately 1.09 V, which is slightly higher than that calculated under the standard state, 0.98 V. This increase is attributed to the lower aFeO content in the melt compared with that in the standard state.

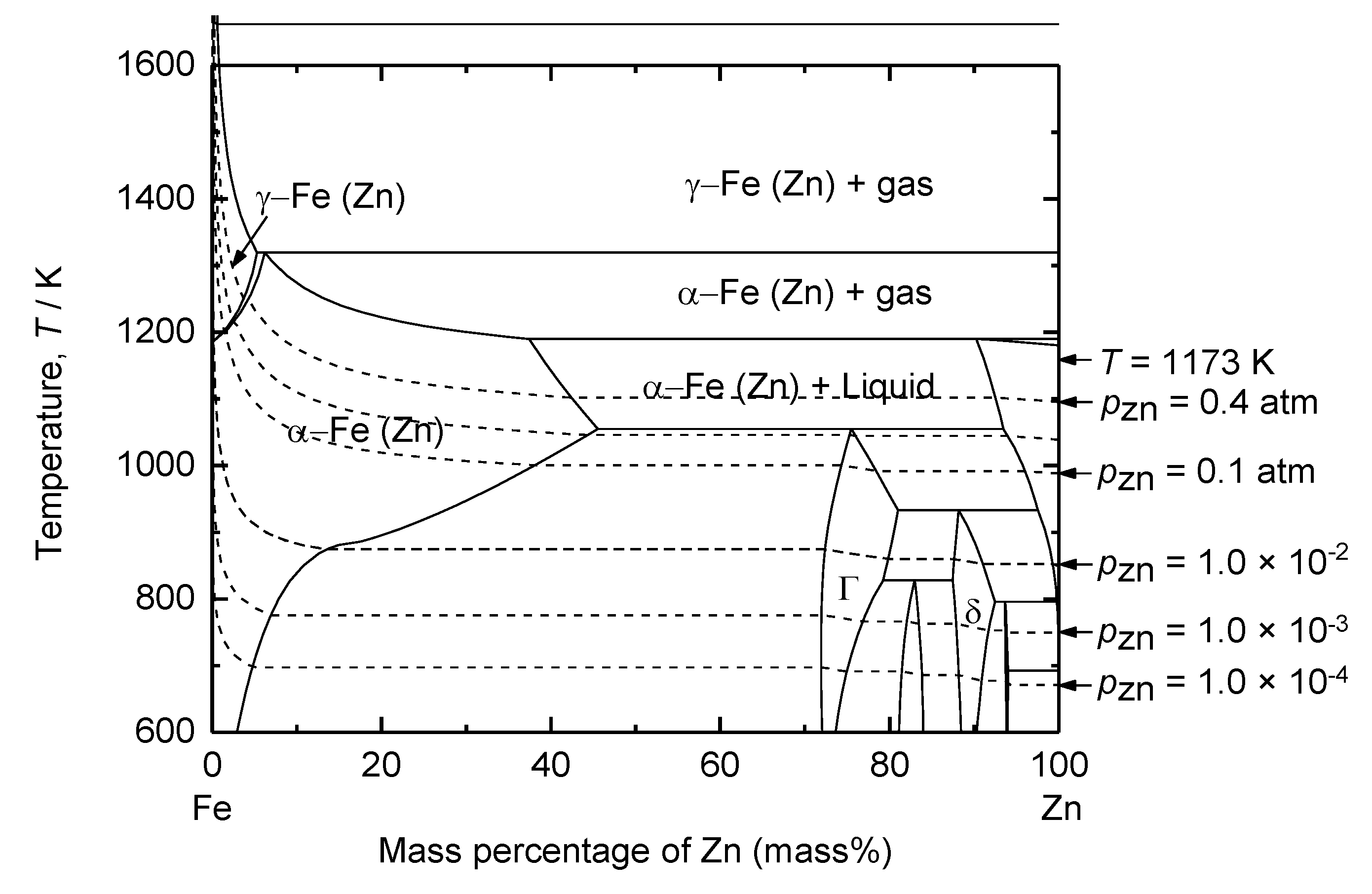

The decomposition voltage for the reduction of ZnO was calculated by considering the activities of ZnO near the cathode and Zn in the Fe – Zn alloy.

Figure 8 shows that the solubility of Zn in Fe is 38.4 mass% at 1173 K. Consequently, the activity of Zn in the 1 mass% Zn – Fe and 38.4 mass% Zn – Fe solid solutions were considered to estimate the decomposition voltage of ZnO. The

aZn of 1 mass% Zn – Fe solid solution indicates the onset of ZnO reduction into the Fe cathode, whereas

aZn of 38.4 mass% Zn – Fe solid solution indicates the saturation of Zn in the Fe cathode by ZnO reduction. The resulting decomposition voltages were estimated to 1.21 V for 1 mass% Zn – Fe solid solution and 1.34 V for 38.4 mass% Zn – Fe solid solution, as shown in

Figure 7.

For the supporting electrolytes, the calculation results indicate that both B

2O

3 and Na

2O decompose at higher voltages than that of Fe oxides and ZnO at 1173 K. The decomposition voltage for B

2O

3 (

l, in melt) was estimated to 1.75 V, slightly higher than that of B

2O

3 (

l) which is 1.70 V under the standard state. The decomposition voltage of Na

2O (

l, in melt) was estimated to 2.64 V, which is significantly higher than that of Na

2O (

s) in the standard state, which is 1.33 V. This increase is attributed to a substantial decrease in the activity of Na

2O in the melt. The previous studies have shown that Na

2O exhibits considerably low activity in acidic oxide systems, as it is strongly stabilized in the melt [

32,

33,

34].

These results indicate that the reduction of Fe and Zn occurs prior to the decomposition of the electrolyte components. In addition, the selective reduction of FeO from the mixture of Fe

2O

3 and ZnO is feasible through molten oxide electrolysis at 1173 K by utilizing the difference in their decomposition voltages, as shown in

Figure 7. Furthermore, when the cell voltage above the decomposition voltage determined by ZnO (

l, in melt) / 1 mass% Zn – Fe (

s) Equation is applied to the molten oxide electrolysis of the mixture of Fe

2O

3 and ZnO at 1173 K, the Fe – Zn solid solution will be obtained.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the Fe and Zn production process presented in this study.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the Fe and Zn production process presented in this study.

Figure 2.

Schematic of experimental apparatus used for (a) cyclic voltammetry measurement and (b) electrolysis in this study.

Figure 2.

Schematic of experimental apparatus used for (a) cyclic voltammetry measurement and (b) electrolysis in this study.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic and (b) photograph of the experimental apparatus for vacuum distillation.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic and (b) photograph of the experimental apparatus for vacuum distillation.

Figure 4.

Calculated binary phase diagram of the B2O3 – Na2O system.

Figure 4.

Calculated binary phase diagram of the B2O3 – Na2O system.

Figure 5.

Calculated phase diagram of B2O3 – Na2O – Fe2O3 – ZnO system at 1173 K with constant ZnO content of (a) 0 mass%, (b) 1 mass%, (c) 2 mass%, and (d) 3 mass%.

Figure 5.

Calculated phase diagram of B2O3 – Na2O – Fe2O3 – ZnO system at 1173 K with constant ZnO content of (a) 0 mass%, (b) 1 mass%, (c) 2 mass%, and (d) 3 mass%.

Figure 6.

(a) Variation of Fe2O3 and FeO in melt and the decomposition voltage for reduction of Fe2O3 to FeO as a function of partial oxygen pressure at 1173 K, calculated from FactSage database: electrolyte composition of 73 mass% B2O3 – Na2O. (b) Illustration of reactions during electrolysis of Fe oxide in oxide melt.

Figure 6.

(a) Variation of Fe2O3 and FeO in melt and the decomposition voltage for reduction of Fe2O3 to FeO as a function of partial oxygen pressure at 1173 K, calculated from FactSage database: electrolyte composition of 73 mass% B2O3 – Na2O. (b) Illustration of reactions during electrolysis of Fe oxide in oxide melt.

Figure 7.

Decomposition voltages of selected oxides as a function of ZnO concentration in mixed feedstock.

Figure 7.

Decomposition voltages of selected oxides as a function of ZnO concentration in mixed feedstock.

Figure 8.

Calculated binary phase diagram of Fe – Zn system at 1 atm total pressure. Dotted lines are isobaric vapor pressure of Zn (g).

Figure 8.

Calculated binary phase diagram of Fe – Zn system at 1 atm total pressure. Dotted lines are isobaric vapor pressure of Zn (g).

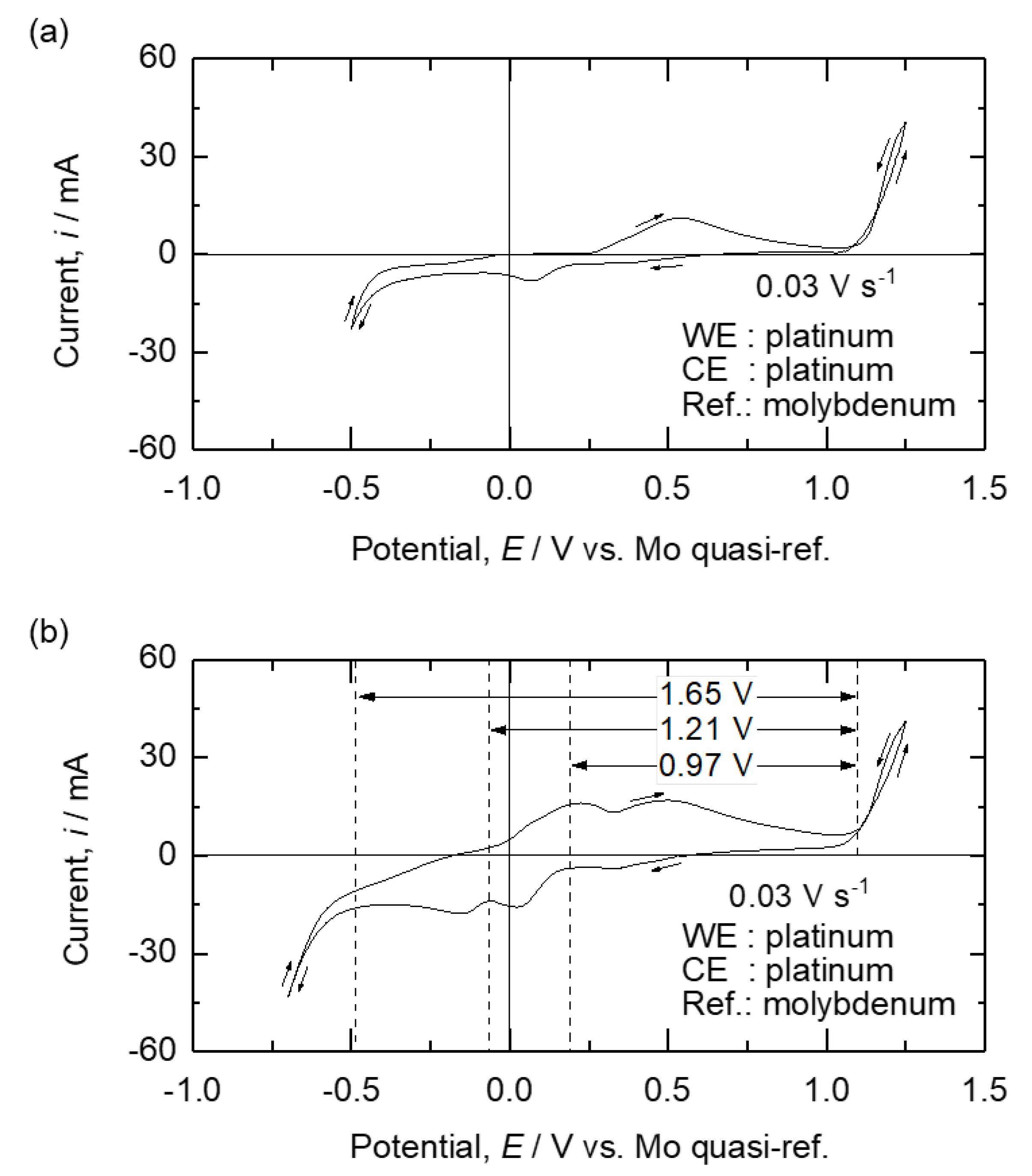

Figure 9.

Results of the CV measurements of (a) B2O3 – Na2O – Fe2O3 molten oxides and (b) B2O3 – Na2O – Fe2O3 – ZnO molten oxides at 1173 K with a scan rate of 0.03 V·s-1.

Figure 9.

Results of the CV measurements of (a) B2O3 – Na2O – Fe2O3 molten oxides and (b) B2O3 – Na2O – Fe2O3 – ZnO molten oxides at 1173 K with a scan rate of 0.03 V·s-1.

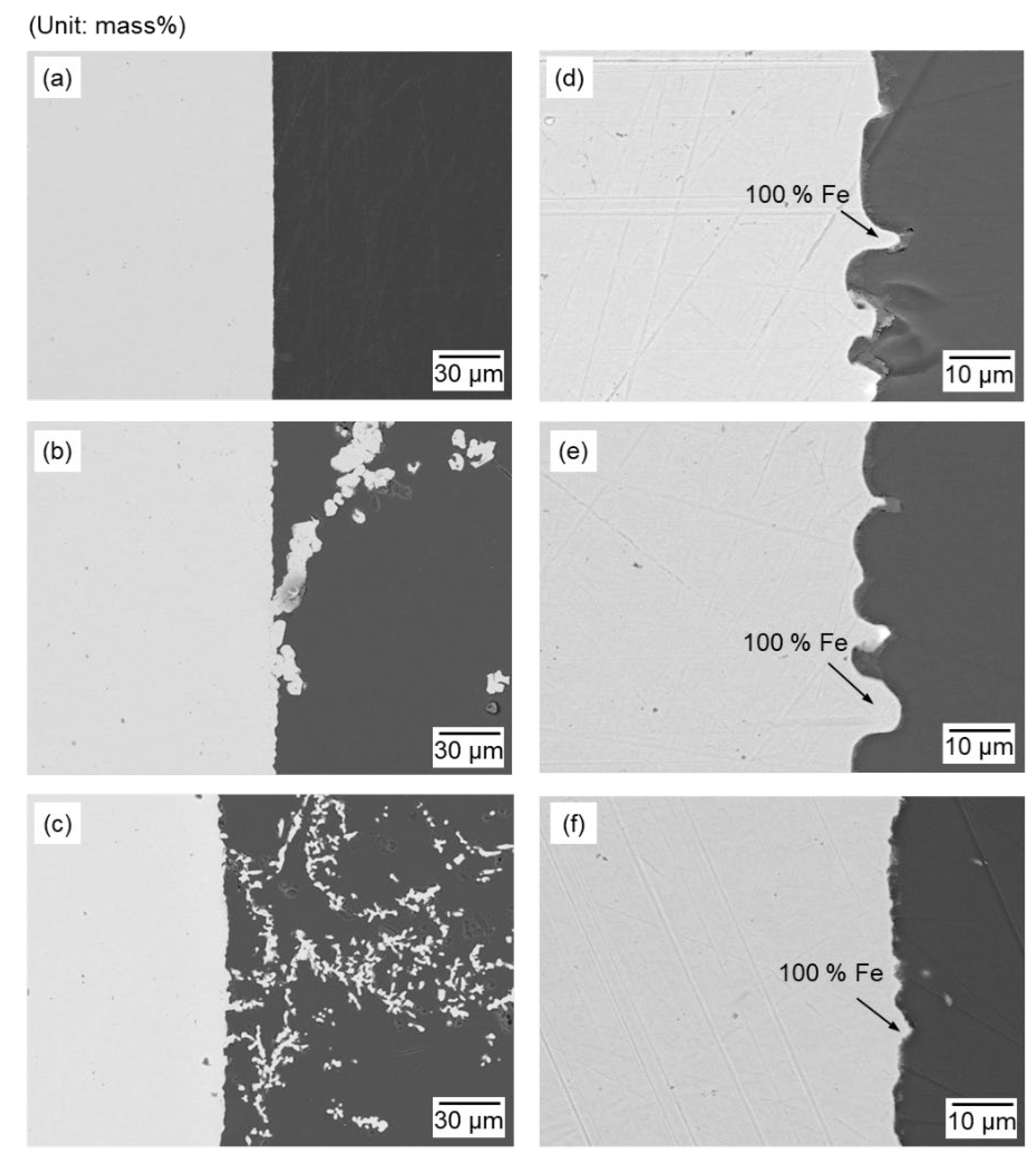

Figure 10.

SEM-EDS analysis results of the cathode surface (a) before electrolysis and after the electrolysis at 1173 K for 1 h with following conditions; (b) 1.1 V, 0.75 g of Fe2O3 + 2.25 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 1-3); (c) 1.6 V, 0.75 g of Fe2O3 + 2.25 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 2-3); (d) 1.1 V, 2.25 g of Fe2O3 + 0.75 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 1-1); (e) 1.1 V, 1.50 g of Fe2O3 + 1.50 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 1-2); and (f) 1.1 V, 0.75 g of Fe2O3 + 2.25 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 1-3).

Figure 10.

SEM-EDS analysis results of the cathode surface (a) before electrolysis and after the electrolysis at 1173 K for 1 h with following conditions; (b) 1.1 V, 0.75 g of Fe2O3 + 2.25 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 1-3); (c) 1.6 V, 0.75 g of Fe2O3 + 2.25 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 2-3); (d) 1.1 V, 2.25 g of Fe2O3 + 0.75 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 1-1); (e) 1.1 V, 1.50 g of Fe2O3 + 1.50 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 1-2); and (f) 1.1 V, 0.75 g of Fe2O3 + 2.25 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 1-3).

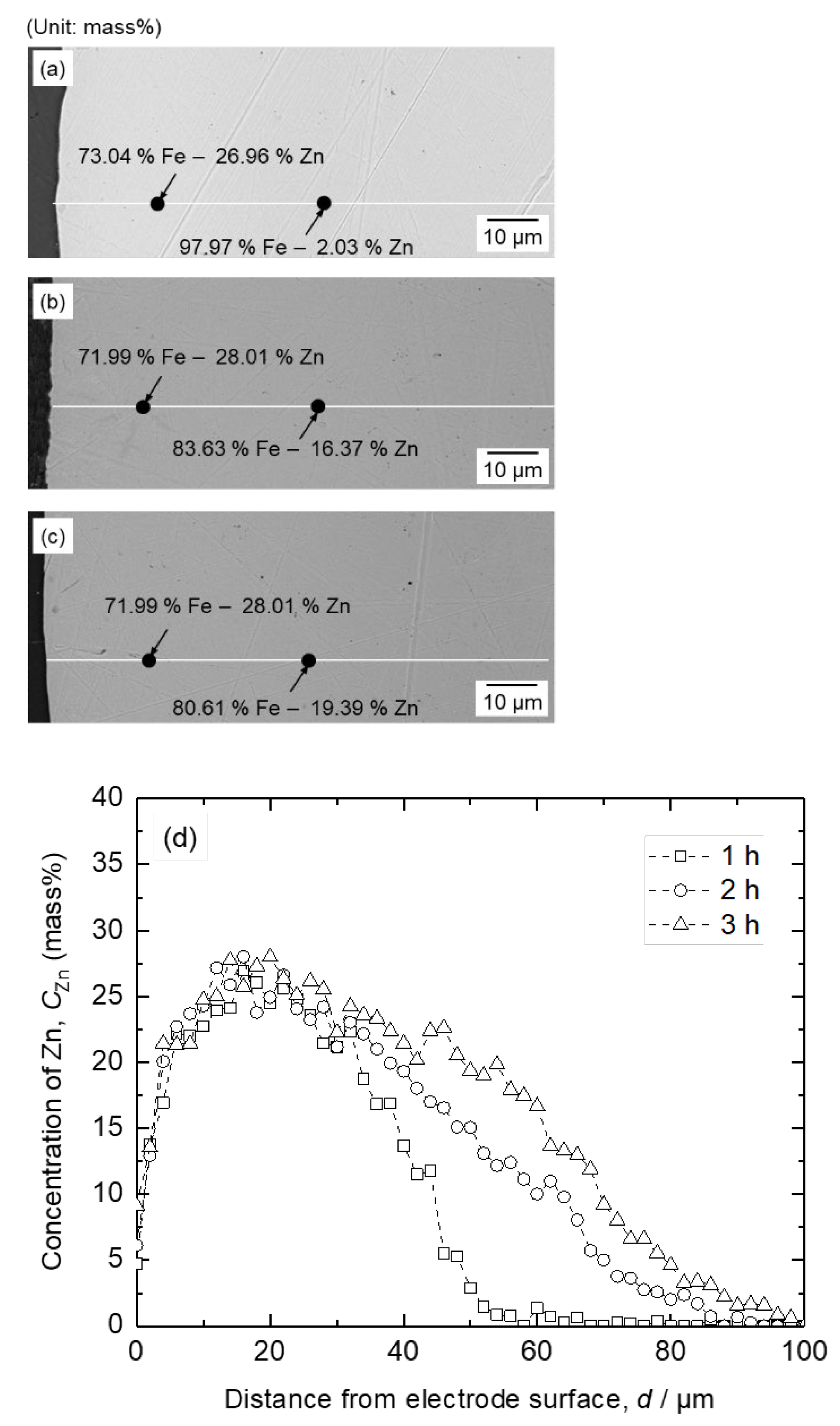

Figure 11.

SEM-EDS analysis results of the cathode after electrolysis of B2O3 – Na2O – ZnO at 1173 K by applying cell voltage of 1.6 V for (a) 1 h, (b) 2 h, and (c) 3 h and (d) EDS line analysis result of Zn concentration in Fe cathode as a function of distance from the electrode surface.

Figure 11.

SEM-EDS analysis results of the cathode after electrolysis of B2O3 – Na2O – ZnO at 1173 K by applying cell voltage of 1.6 V for (a) 1 h, (b) 2 h, and (c) 3 h and (d) EDS line analysis result of Zn concentration in Fe cathode as a function of distance from the electrode surface.

Figure 12.

SEM-EDS analysis results of the cathode after electrolysis of B2O3 – Na2O – Fe2O3 – ZnO at 1173 K for 1 h by applying cell voltage of 1.6 V in following feedstocks; (a) (a) 2.25 g of Fe2O3 + 0.75 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 2-1); (b) 1.50 g of Fe2O3 + 1.50 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 2-2); (c) 0.75 g of Fe2O3 + 2.25 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 2-3) and (d) EDS line analysis result of Zn concentration in Fe cathode as a function of distance from the electrode surface.

Figure 12.

SEM-EDS analysis results of the cathode after electrolysis of B2O3 – Na2O – Fe2O3 – ZnO at 1173 K for 1 h by applying cell voltage of 1.6 V in following feedstocks; (a) (a) 2.25 g of Fe2O3 + 0.75 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 2-1); (b) 1.50 g of Fe2O3 + 1.50 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 2-2); (c) 0.75 g of Fe2O3 + 2.25 g of ZnO (Exp. no. 2-3) and (d) EDS line analysis result of Zn concentration in Fe cathode as a function of distance from the electrode surface.

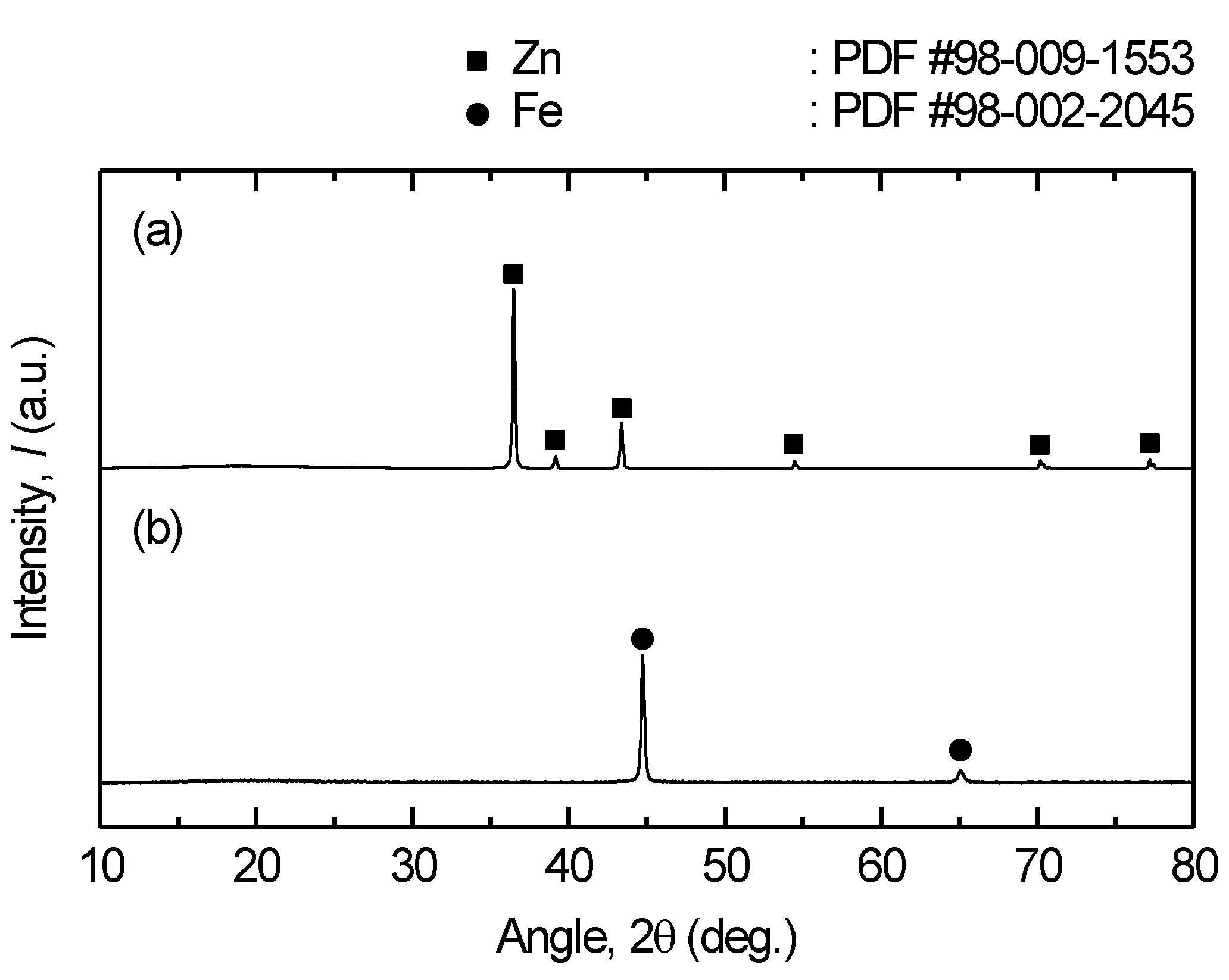

Figure 13.

XRD results of the (a) deposit obtained from the low-temperature part of the reactor and (b) residue at the bottom of the reactor after vacuum distillation of Fe – Zn alloy at 1200 K for 12 h.

Figure 13.

XRD results of the (a) deposit obtained from the low-temperature part of the reactor and (b) residue at the bottom of the reactor after vacuum distillation of Fe – Zn alloy at 1200 K for 12 h.

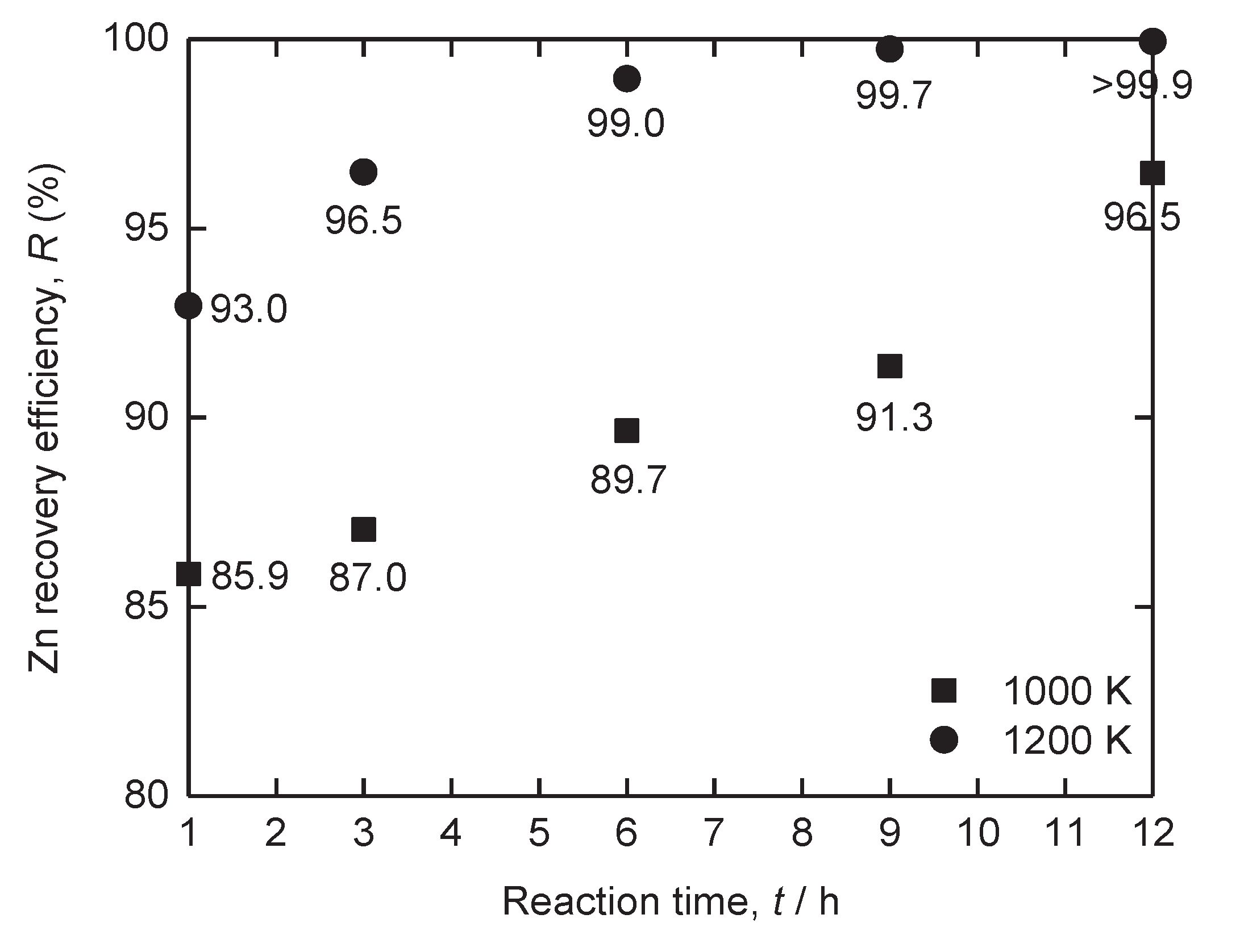

Figure 14.

Zn recovery efficiency obtained after vacuum distillation of Fe – Zn alloy at 1000 K and 1200 K for 1 – 12 h.

Figure 14.

Zn recovery efficiency obtained after vacuum distillation of Fe – Zn alloy at 1000 K and 1200 K for 1 – 12 h.

Table 1.

Previous studies on electrolysis of Fe oxide feedstock in various electrolytes.

Table 1.

Previous studies on electrolysis of Fe oxide feedstock in various electrolytes.

| Method |

Electrolyte |

Feedstock |

Temp,T / K |

Electrode for electrolysis |

Cathode product |

Cell voltage,E / V |

Faradic efficiency,(%) |

Ref. |

| Type |

FeOx conc.(mass%) |

Cathode |

Anode |

Molten

oxide

electrolysis |

Al2O3 – CaO – MgO |

Fe3O4

|

10 |

1838 |

Mo |

Cr90Fe10

|

Fe |

3.8 |

34 |

[5] |

| Al2O3 – CaO – MgO – SiO2

|

Fe2O3

|

10 |

1873 |

Mo |

Graphite |

Fe |

2 |

32 |

[6] |

| Al2O3 – MgO – SiO2

|

Fe3O4

|

15 |

1823 |

Pt – Rh |

Pt |

Fe |

3 |

36 |

[7] |

| Al2O3 – CaO – SiO2

|

Fe2O3

|

5 |

1773 – 1873 |

Mo |

Graphite |

Fe |

– |

64 – 83 |

[8] |

| Al2O3 – CaO – MgO – SiO2

|

Fe2O3

|

9.1 |

1823 |

Mo |

Ir |

Fe |

2 |

25a

|

[9] |

| Al2O3 – CaO – MgO – SiO2

|

Fe2O3

|

5 |

1848 |

Mo |

Ir |

Fe |

– |

– |

[10] |

| B2O3 – Na2O |

Fe2O3

|

5 |

1273 |

Pt |

Pt |

Fe |

1.4 |

33.2 |

[11] |

| K2MoO4 – Fe2O3

|

Fe2O3

|

– |

1273 |

Steel |

Steel |

Fe – Mo |

– |

70.77 |

[12] |

| Al2O3 – CaO – MgO – SiO2

|

Fe2O3,

NiO |

15 |

1723 |

W |

Graphite |

Fe – Ni |

– |

46 |

[13] |

Molten

salt

electrolysis |

CaCl2 – KF |

Fe2O3

|

1.7 |

1100 |

Fe |

Fe3O4

|

Fe |

– |

– |

[14] |

| CaCl2 – CaF2

|

Fe2O3

|

1.5 |

1163 |

Fe |

Fe3O4

|

Fe |

– |

92 |

[15] |

| NaCl – CaCl2 |

Fe2O3b

|

– |

1073 |

Fe2O3

|

Graphite |

Fe |

1.2 |

95.3 |

[16] |

| LiCl |

Fe2O3b

|

– |

933 |

Fe2O3

|

Graphite |

Fe |

0.97 |

97 |

[17] |

| CaCl2

|

Fe2O3b

|

– |

1073 |

Fe2O3

|

Graphite |

Fe |

1.8 |

90 |

[18] |

| NaCl – CaCl2 |

ZnFe2O4b

|

– |

1073 |

ZnFe2O4

|

Graphite |

Fec

|

1.8 |

– |

[19] |

| NaCl – KCl |

Fe2O3,

Al2O3b

|

– |

1123 |

Fe2O3 –

Al2O3

|

Graphite |

FeO – Al2O3

|

2.3 |

– |

[20] |

| CaCl2

|

Fe2O3,

TiO2b

|

– |

1223 |

Fe2O3 –

TiO2

|

Graphite |

Fe – Ti |

3 |

– |

[21] |

| CaCl2

|

Fe2O3,

Tb4O7b

|

– |

1173 |

Fe2O3 –

Tb4O7

|

Graphite |

Fe – Tb |

2.6 |

13.6 |

[22] |

Molten

carbonate

electrolysis |

Na2CO3 – K2CO3 |

Fe2O3b

|

– |

1023 |

Fe2O3

|

NiCuFe |

Fe |

2 |

93.6 |

[23] |

Molten

hydroxide

electrolysis |

NaOH |

Fe2O3b

|

– |

803 |

Fe2O3

|

Ni |

Fe |

1.7 |

89 |

[24] |

| NaOH |

Fe2O3b

|

– |

773 |

Fe2O3

|

Ni Si Al |

Fe |

1.7 |

30 |

[25] |

Table 2.

Experimental conditions for the electrolysis of Fe2O3 and/or ZnO using Fe cathode and Pt anode at 1173 K.

Table 2.

Experimental conditions for the electrolysis of Fe2O3 and/or ZnO using Fe cathode and Pt anode at 1173 K.

| Exp.no.a

|

Weight of feed, wfeed / g |

Mass ratio of oxide to feed, roxide / feed

|

Applied cell voltage,E / V |

Time,t / h |

| Fe2O3

|

ZnO |

Fe2O3

|

ZnO |

| 1-1 |

2.25 |

0.75 |

0.75 |

0.25 |

1.10 |

1 |

| 1-2 |

1.50 |

1.50 |

0.50 |

0.50 |

1.10 |

1 |

| 1-3 |

0.75 |

2.25 |

0.25 |

0.75 |

1.10 |

1 |

| 2-1 |

2.25 |

0.75 |

0.75 |

0.25 |

1.60 |

1 |

| 2-2 |

1.50 |

1.50 |

0.50 |

0.50 |

1.60 |

1 |

| 2-3 |

0.75 |

2.25 |

0.25 |

0.75 |

1.60 |

1 |

| 3-1 |

0.00 |

3.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

1.60 |

1 |

| 3-2 |

0.00 |

3.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

1.60 |

2 |

| 3-3 |

0.00 |

3.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

1.60 |

3 |

Table 3.

Theoretical decomposition voltages of selected oxides at 1173 K, 1273 K and 1373 K.

Table 3.

Theoretical decomposition voltages of selected oxides at 1173 K, 1273 K and 1373 K.

| Reaction |

Decomposition voltage, Eo / V |

Phase transformation |

| 1173 K |

1273 |

1373 K |

| FeO (s) = Fe (s) + 1/2 O2 (g) |

0.98 |

0.94 |

0.91 |

Fe (BCC) → Fe (FCC) at 1184.81 K |

| ZnO (s) = Zn (l,g) + 1/2 O2 (g) |

1.19 |

1.09 |

0.98 |

Zn (l) → Zn (g) at 1181.47 K |

| B2O3 (l) = 2 B (s) + 3/2 O2 (g) |

1.70 |

1.66 |

1.62 |

– |

| Na2O (s) = 2 Na (g) + 1/2 O2 (g) |

1.33 |

1.18 |

1.03 |

Na2O (β) → Na2O (α) at 1243 K |

| Fe2O3 (s) = 2 Fe (s) + 3/2 O2 (g) |

0.90 |

0.86 |

0.81 |

Fe (BCC) → Fe (FCC) at 1184.81 K |

| Fe3O4 (s) = 3 Fe (s) + 2 O2 (g) |

0.96 |

0.92 |

0.88 |

Fe (BCC) → Fe (FCC) at 1184.81 K |

| Fe2O3 (s) = 2 FeO (s) + 1/2 O2 (g) |

0.74 |

0.68 |

0.62 |

– |