1. Introduction

Chromite ore is an important raw material for the production of ferrochrome in the metallurgical industry [

1]. Approximately 90% of chromite ore is employed in the production of ferrochrome, and roughly 80% of the produced ferrochrome is utilized for the manufacture of stainless steel [

2]. The steady expansion of the stainless steel industry has significantly driven up the demand for ferrochrome alloys [

3]. Currently, submerged arc furnace (SAF) smelting is widely adopted in the world. However, SAF smelting is an energy-intensive process, with average energy consumption being 3 to 5 times higher than that of the blast furnace ironmaking process [

4,

5]. Therefore, it is very important that take enhanced measures to reduce energy consumption of chromite smelting.

Solid-state reduction of chromite ore prior to entering the SAF smelting process is an effective strategy for reducing the energy consumption of the SAF smelting process [

4,

5]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that higher degrees of pre-reduction of chromite ore result in lower specific electricity consumption (SEC) [

8]. The lowest specific electricity consumption (SEC) achieved through the solid-state reduction process of chromite ore is approximately 2.4 MWh/t FeCr, whereas the SEC for conventional SAF production ranges from 3.9 to 4.2 MWh/t FeCr [

9]. Clearly, the solid-state reduction of chromite ore offers significant advantages in terms of SEC. Therefore, enhancing the solid-state reduction of chromite ore is crucial for reducing the energy consumption during chromite ore smelting. Many researchers have conducted extensive studies on measures to improve the solid-state reduction of chromite ore. These measures can be categorized into two groups: pretreatment of chromite ore and the use of additives.

With regard to the pretreatment of chromite ore, Kleynhans et al. [

10] demonstrated that pre-oxidizing treatment can enhance the reduction of chromite ore by promoting the release of Fe ions and inhibiting the release of chromium oxide (Cr

2O

3) from the spinel structure, thereby improving the overall reduction process. Pan et al. [

11] further reported that pre-oxidation treatment facilitates the formation of a sesquioxide solid solution and generates cationic vacancies, both of which significantly increase the reactivity of chromite ore. Additionally, Apaydin et al. [

12] showed that mechanical activation induces amorphization and structural disorder in chromite ore, creating more microcracks, disrupting the spinel structure, and consequently enhancing the solid-state reduction process of chromite ore.

Additives have been shown to facilitate the reduction of chromite ore. However, the efficacy of different types of additives in promoting this reduction varies. Research has demonstrated that additives functioning as slagging and fluxing agents can lower the melting point of refractory components in chromite, reduce the diffusion resistance of reactants, and enhance heat and mass transfer conditions [

13,

14,

15]. Furthermore, additives can catalyze the Boudouard reaction, thereby intensifying the reduction of chromite [

16,

17]. Additionally, oxide additives with large ionic radii can alter the spinel structure, improving the solid-phase diffusion capability of Cr and thus catalyzing the reduction reaction of chromite [

18,

19]. Although these additives demonstrate the potential to enhance the reduction of chromite, they still pose certain challenges in practical applications. For instance, although CaCO

3 reduces the Gibbs free energy of chromite reduction, its incorporation may compromise the compressive strength and wear resistance of chromite pelletized ores, thereby adversely affecting the stability and safety during smelting [

18]. It also introduces some unnecessary impurity elements, which will increase the burden of subsequent separation and purification and affect product quality. Therefore, researchers have developed a new additive strategy by adding alloying elements or forming alloying phases in situ [

20,

21,

22,

23], such as nickel powder, iron powder, mill scale (FeO

x), nickel laterite, etc. These additives promote the reduction of chromite ore mainly by forming low-melting-point alloys during the reduction process, lowering the temperature and apparent activation energy of the reduction reaction, and thus promoting the reduction of chromite ore.

Hu et al. [

24] systematically investigated the influence of iron powder on the non-isothermal reduction process of synthetic chromite (FeCr

2O

4). Their findings demonstrated that iron powder serves as an effective catalyst for the reduction reaction of synthetic chromite, reducing the activation energy required for the reaction. Consequently, this leads to a decrease in the reduction temperature and an enhancement in the reaction rate. In general, iron oxide is more readily reduced compared to chromium oxide during the reduction process of natural chromite ore [

25]. At temperatures lower than 1200°C, only Cr

2O

3 is found in the reaction products, and chromium metal is not found [

26]. If the iron oxide in the chromite ore can be reduced as much as possible in a short period of time and at a low reduction temperature(such as below 1200°C), the energy consumption of solid-state reduction of chromite ore will be reduced. Then the iron metal can promote the reduction of chromium oxide during the subsequent smelting process. Therefore, it is worth studying the influencing mechanism of iron powder on the solid reduction of natural chromite ore under isothermal conditions below 1200°C.

In this investigation, the solid-state reduction characteristics of natural chromite ore and the effect of iron powder on the solid-state reduction characteristics of natural chromite ore under iso-thermal conditions below 1200°C were studied. Moreover, the enhancing mechanism of iron powder on the solid-state reduction of natural chromite ore was revealed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

The chromite concentrate used in this study was obtained from South Africa, and its chemical composition is shown in

Table 1. The content of FeO and Cr

2O

3 in the chromite concentrate is 20.81% and 41.32%, respectively, with a Cr/Fe ratio of 1.99, indicating that the chromite concentrate belongs to low-grade ore. The content of S and P elements is low, which is favorable for subsequent pyrometallurgical smelting. The percentage of chromite ore with grinding particle size less than 0.074 mm reaches more than 85%, meeting the requirements for granulation, as shown in

Table 2. The additive employed in this study was metallic iron powder with analytical grade purity, and 100% of the particles were smaller than 0.074 mm in size.

The fixed carbon content of the reductant used was 87.3%, with ash and volatile matter being 10.51% and 0.92%, respectively. The reductant had a low sulfur content and high drop strength, as shown in

Table 3. The reductant was ground using a ball mill until the percentage of particles smaller than 0.074 mm reached 100%.

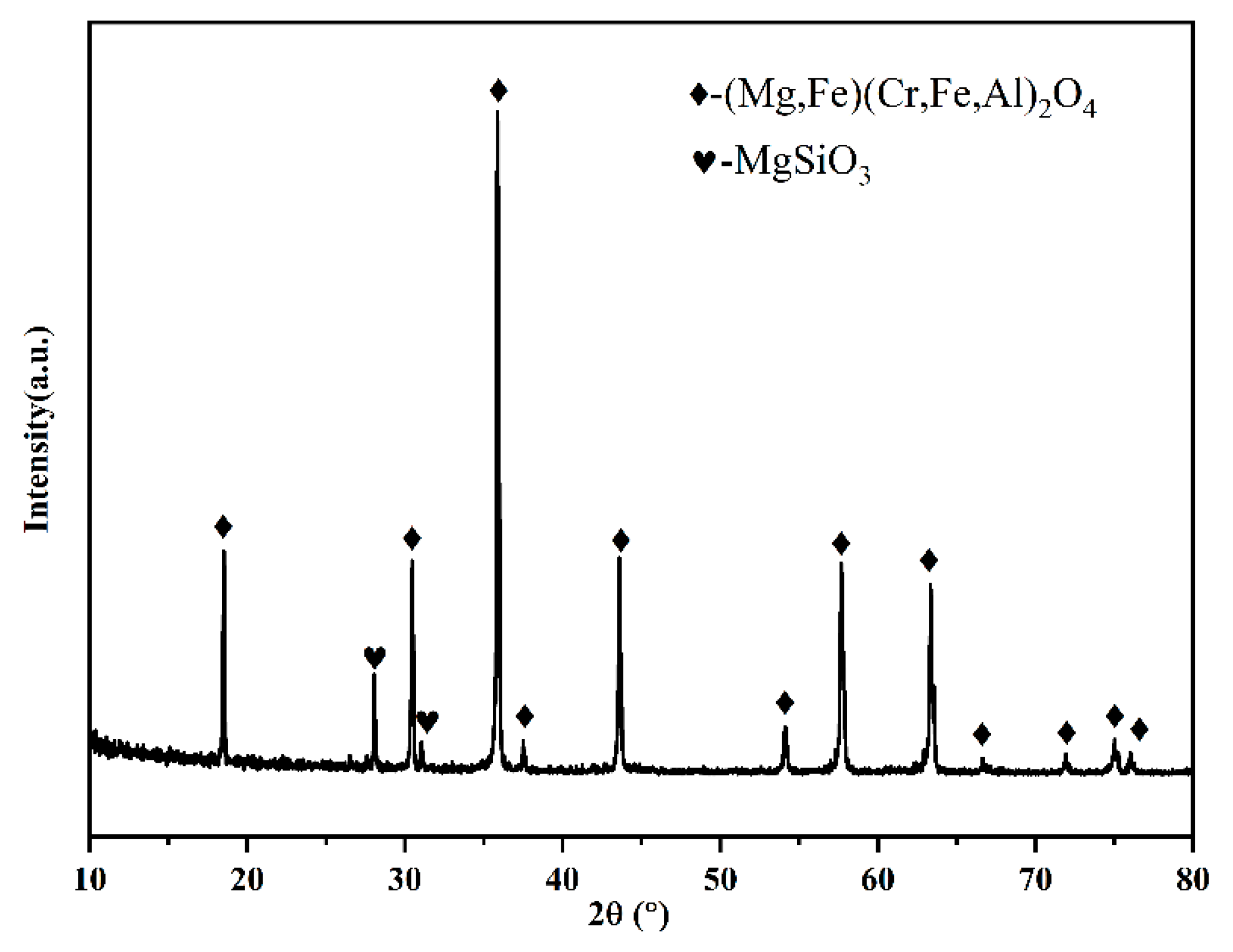

The XRD results of the raw ore can be analyzed to determine that the main mineral phases of chromite ore are spinel (Mg, Fe)(Cr, Fe, Al)

2O

4 and MgSiO

3. Both chromium and iron are primarily present in the spinel structure, as shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Briquetting

The chromite concentrate, carbon powder and iron powder were mixed well in a mixer, moistened with an appropriate amount of water, and made into agglomerates (20*8 mm) using a DY-20 table-top electric tablet press. The agglomerates were then dried in a blast drying oven at 105°C for 6 hours to remove excess moisture and subsequently subjected to reduction roasting.

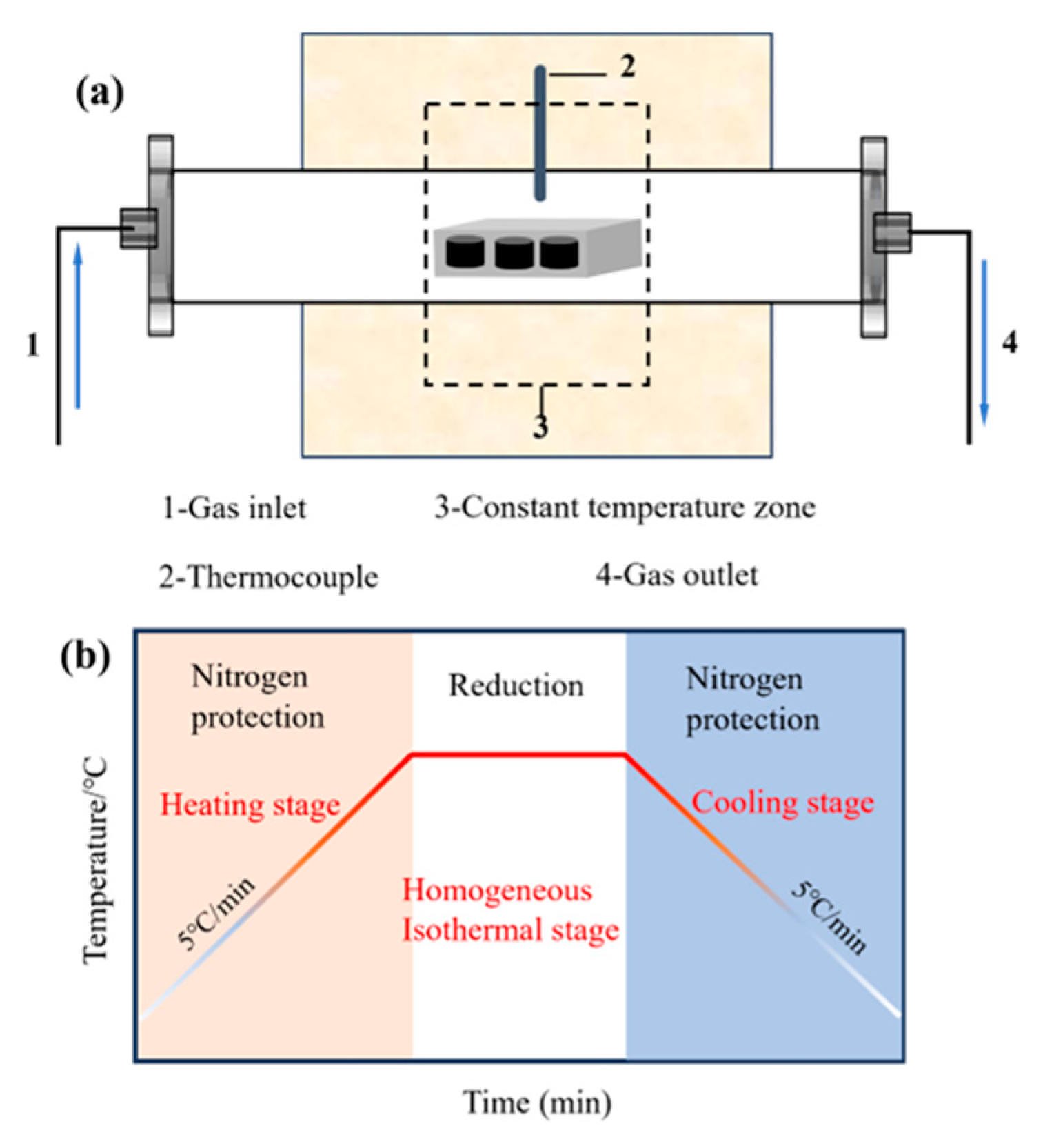

2.2.2. Reduction Roasting

Reduction roasting experiments of agglomerates were carried out in a horizontal tube furnace with a diameter of 35 mm. To establish the reduction roasting experimental program, the agglomerates were placed in a porcelain boat and positioned in the constant temperature zone of the horizontal tube furnace as shown in

Figure 2(a). The heating and cooling rates for the reduction roasting experiment were set at 5 °C/min. To prevent oxidization of samples during the reduction roasting process, high-purity nitrogen was continuously fed into the furnace at a rate of 200 ml/min. The actual reduction roasting temperature profile is presented in

Figure 2(b), and the reduction conditions are listed in

Table 4. The dosages of carbon powder and iron powder were determined based on the percentage of chromite ore. A single-variable approach was employed to investigate the effects of different conditions on the solid-state reduction of chromite, thereby determining the optimal reduction conditions.

2.2.3. Analysis and Characterization

After the reduction roasting trial was completed, some samples of agglomerates under each reduction condition were ground into powder and sieved through a 200-mesh sieve. The composition of the samples under various reduction conditions was systematically investigated. The content of metallic iron and total iron in the samples was quantitatively analyzed using the FeCl

3 titration method and the EDTA titration method, respectively. Based on these results, the iron metallization rate can be calculated using the formula:

is the iron metallization rate of chromite ore, %.

is the metal iron content of the reduced sample, %.

is the total iron content of the reduced sample, %.

represents the metal iron content contributed by iron powder, %.

represents the total iron content contributed by iron powder, %.

is the change in the iron metallization rate of the chromite ore with and without the addition of iron powder, %.

is the iron metallization rate of the chromite ore after the addition of iron powder, %.

is the metallization rate of the chromite ore without iron powder addition, %.

The mineral phase analysis of the reduced samples under different conditions was carried out by X-ray diffractometer (XRD, D8 Advance, Cu Kα) with a scanning angle of 5~90° and a scanning speed of 10°/min. In addition, the reduced samples were embedded in epoxy resin and then polished across the sections. A microscope and a scanning electron microscope (SEM, ZEISS Sigma 300, Germany) were used to analyze the microstructure and mineralogy of the reduced samples, and an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS, OXFORD Instrument) was used to determine the mineral composition in the reduced samples.

3. Results and Discussion

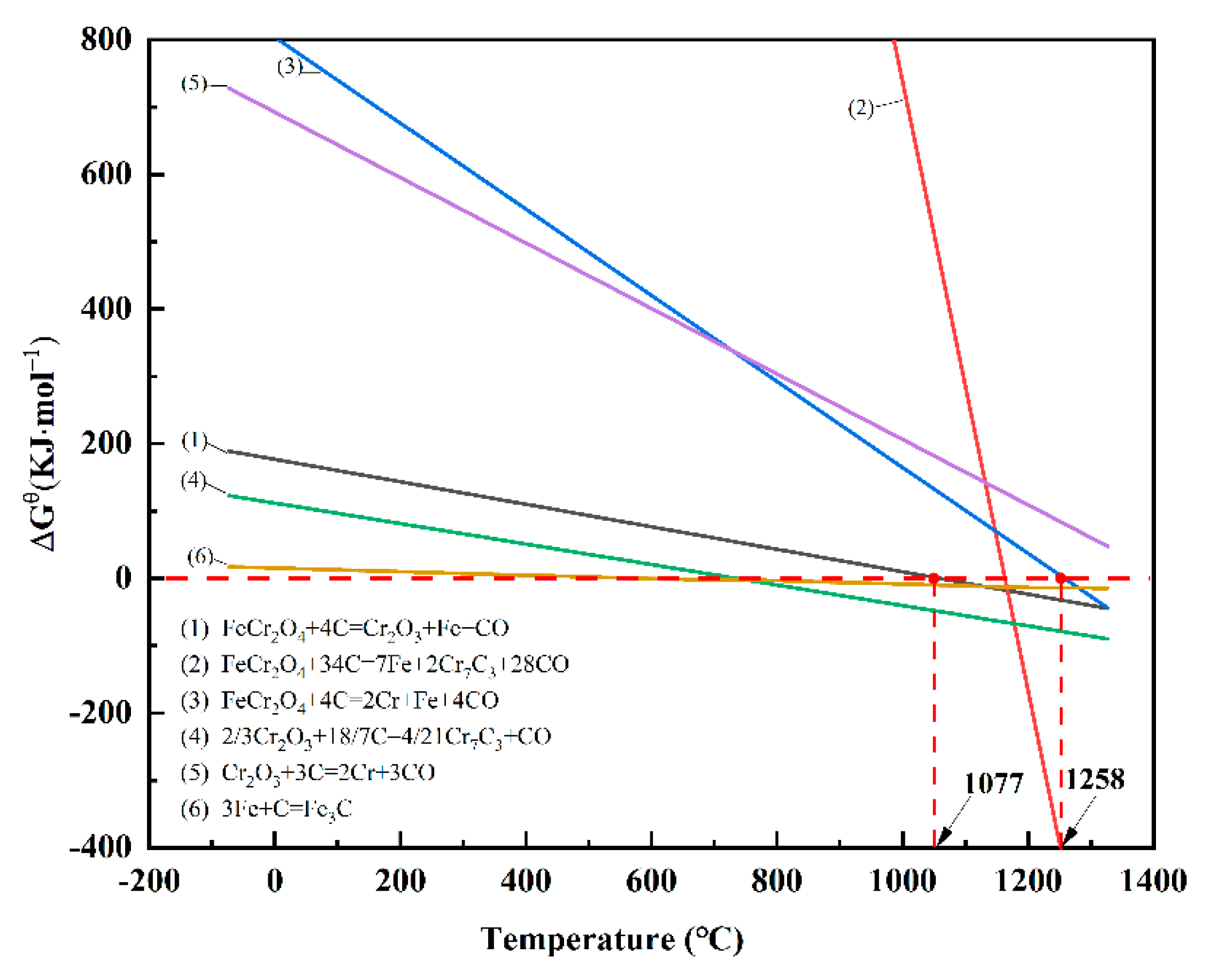

3.1. Thermodynamics of Chromite Solid State Reduction

The initial temperatures of the reduction reactions for each component in chromite can be determined using thermodynamic data. Investigating the carbothermal reduction thermodynamics of pure FeO, Cr

2O

3, and FeCr

2O

4 provides valuable insights into understanding the carbothermal reduction thermodynamics of chromite [

27]. The relationship between the standard Gibbs free energy of the reduction reactions involving carbon for these pure substances under standard atmospheric pressure and temperature is illustrated in

Figure 3. It is evident that in the presence of solid carbon, a series of reduction and carburization reactions occur in FeCr

2O

4. At an initial reaction temperature of 1077°C, FeCr

2O

4 is reduced to Cr

2O

3 and metallic iron, whereas the starting temperature for generating metallic chromium and metallic iron is 1258°C [

28,

29]. When the reduction temperature is below 1200°C, chromite is primarily reduced to metallic iron and ferrochromium carbide, with the amount of reduced metallic chromium being very small. These research findings offer theoretical guidance for this study. Since the primary objective of this study is to explore the effect of adding metallic iron on the reduction of iron oxides during the solid-state reduction process of chromite, the reduction temperature for subsequent solid-state reduction experiments will be set below 1200°C.

3.2. Solid-State Reduction Characteristics of Natural Chromite Ore

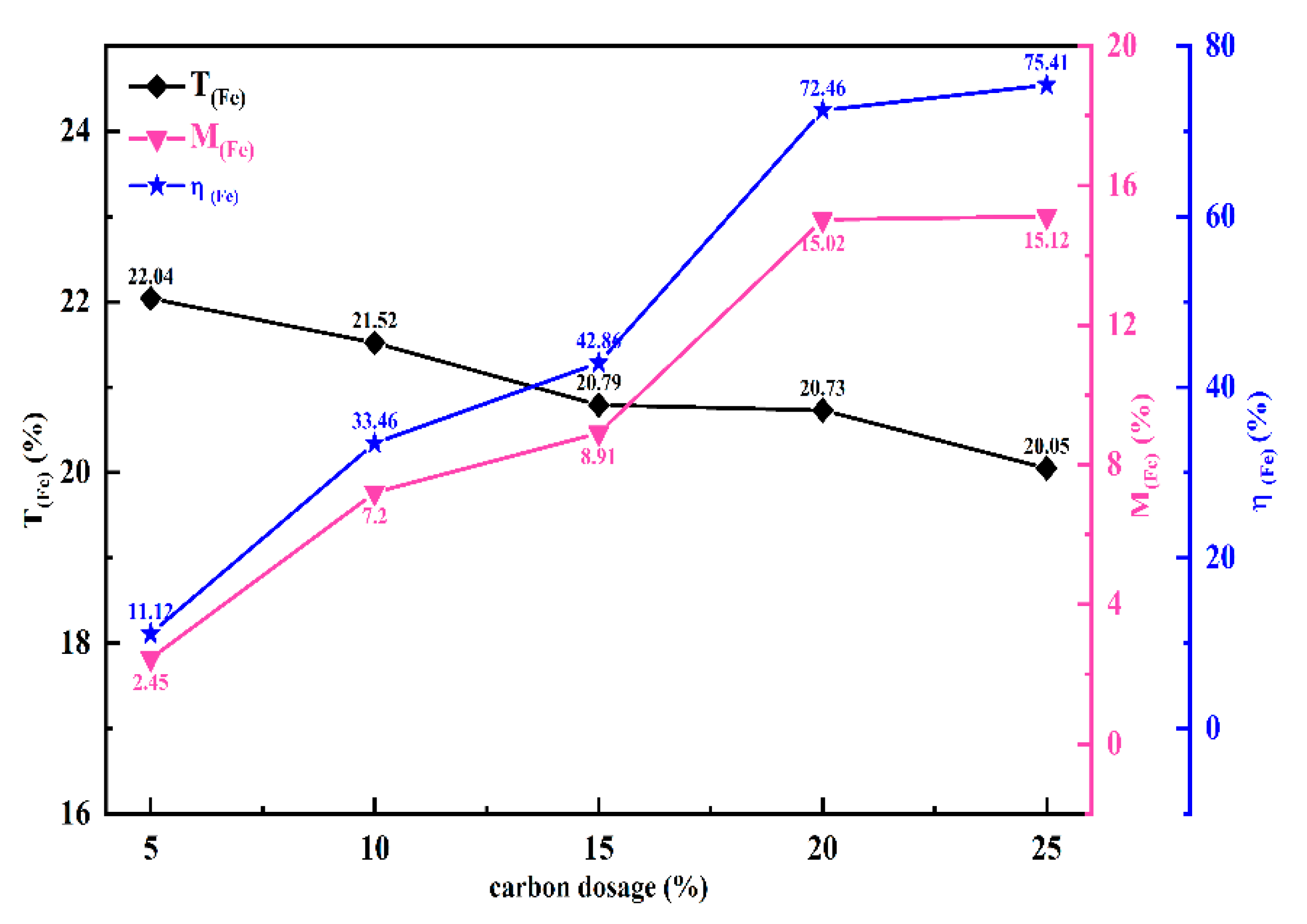

3.2.1. Carbon Dosage

The effect of different carbon dosages on the metallization rate of chromite ore is shown in

Figure 4. The results indicate that with the increase in internal carbon dosages, the iron metallization rate exhibits a gradually increasing trend, particularly between 5% and 20%. After the carbon dosage is increased to 20%, the increase in the iron metallization rate slows down. Therefore, the optimal carbon dosage in this study is determined to be 20%. The amount of carbon is a critical factor influencing the outcomes of chromite solid-state reduction. An appropriate amount of carbon can enhance the metallization rate and reduction speed, thereby promoting the reduction reaction of chromite [

6]. However, adding excessive carbon does not significantly improve reduction; The excessive input of carbonaceous reducing agents can facilitate the formation of stable carbide phases of metal elements, increase the technical complexity of the subsequent product separation process, and concurrently result in a rise in both energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions [

30]. thus, it is essential to accurately control the amount of carbon added during experiments and production.

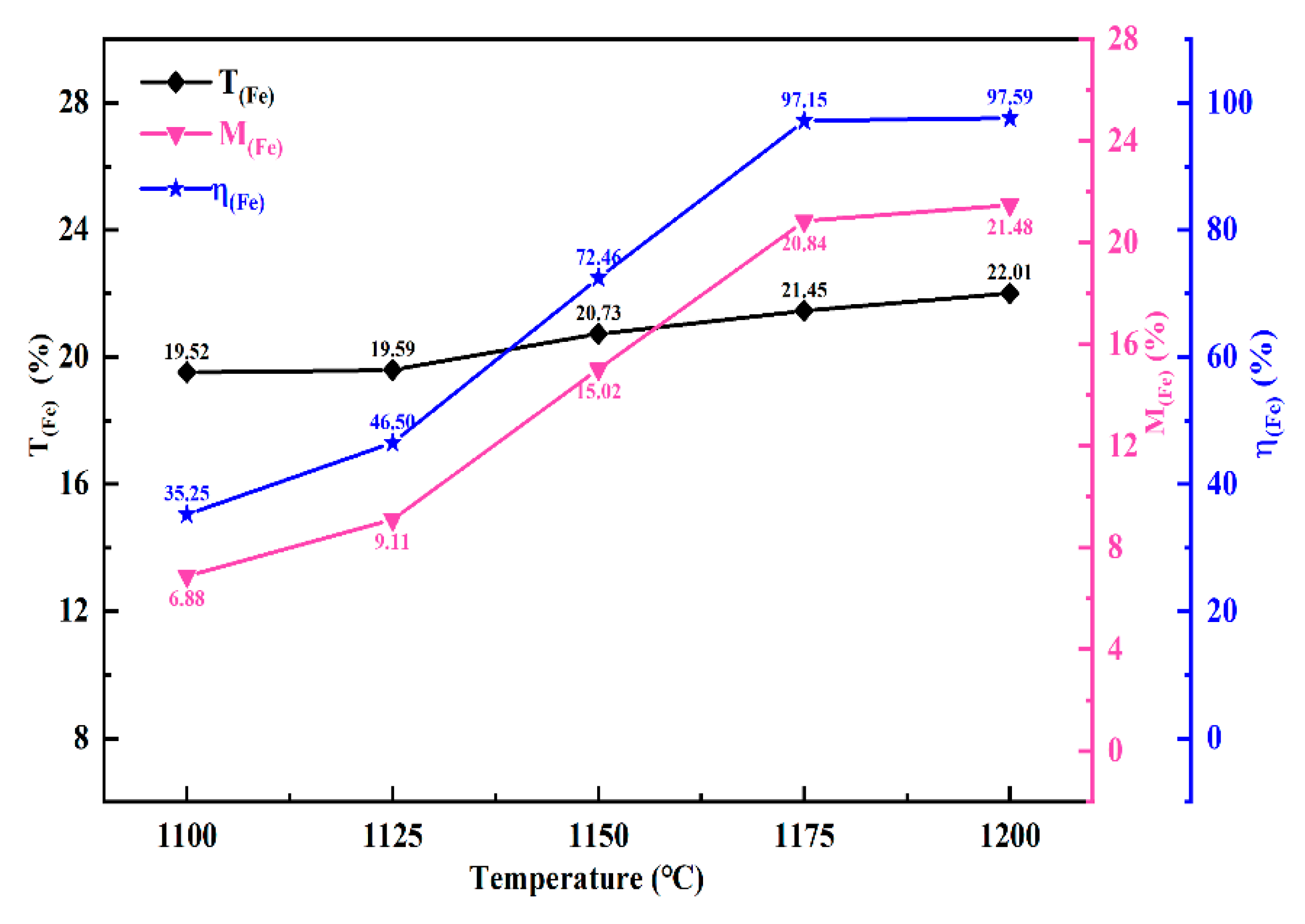

3.2.2. Reduction Temperature

Figure 5 demonstrates the influence of reduction temperature on the rate of iron metallization in chromite ore. The results indicate that the iron metallization rate increased with the rise in reduction temperature within the tested temperature range. Notably, a rapid increase in the metallization rate was observed between 1125°C and 1175°C, rising from 46.50% to 97.15%. At 1175°C, the metallization rate approached stabilization, and further increases in temperature had negligible effects. Consequently, 1175°C was determined as the optimal temperature for this study.

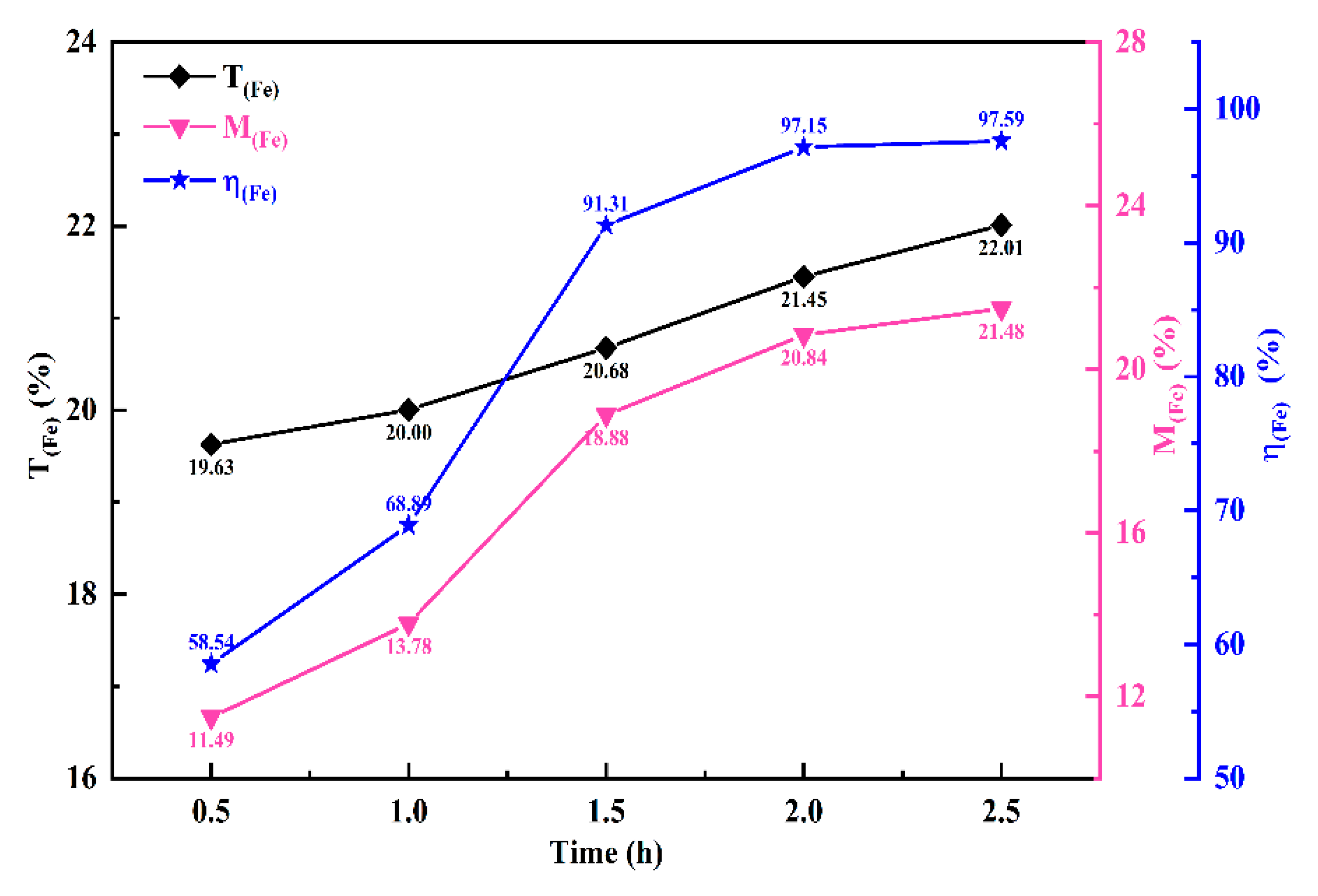

3.2.3. Reduction Duration

Figure 6 illustrates how the iron metallization rate is influenced by the reduction duration. As shown in

Figure 6, under the same temperature conditions, with the extension of the reduction time, the metallization rate of iron exhibits an increasing trend. However, when the reduction duration exceeds 2 h, the growth trend of the iron metallization rate slows down. After 2 h of reduction at 1175 °C, the iron metallization rate of the sample reaches 97.15%. Therefore, a reduction duration of 2 h is recommended as optimal. To investigate the effect of iron powder addition on the solid-state reduction of chromite, a reduction time of 1.5 h was selected for subsequent investigations in this study.

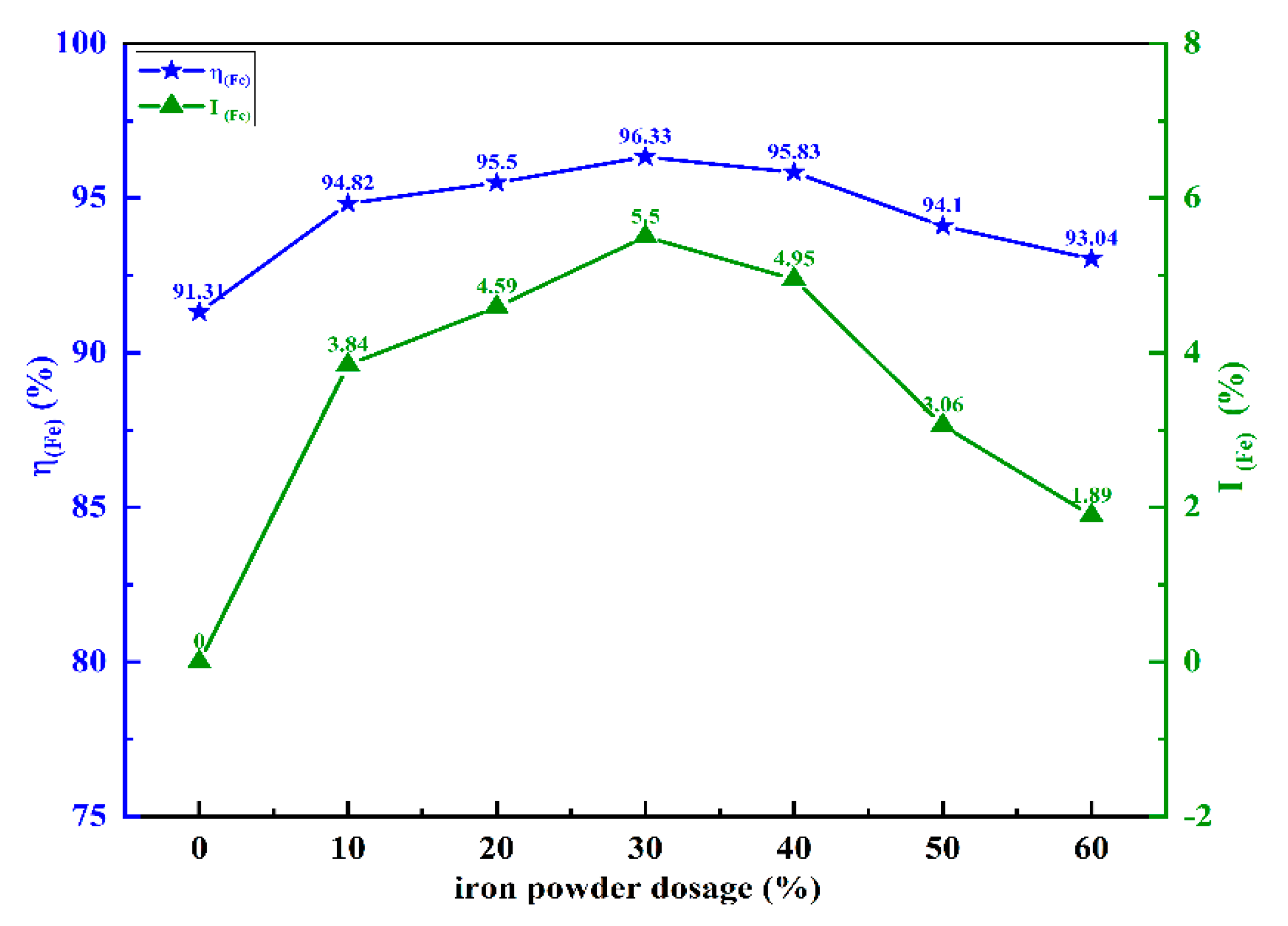

3.3. Effect of Iron Powder Dosage on the Solid-State Reduction of Natural Chromite

The effects of iron powder additions on the iron metallization rate are shown in

Figure 7.

With the addition of iron powder ranging from 0% to 60%, the iron metallization rate exhibited a trend of first increasing and then decreasing, with the highest point appearing at 30% iron powder addition, where the iron metallization rate reached 96.33%. Compared with the chromite ore without added iron powder, the iron metallization rate of the sample with added iron powder increased by 5.50 percentage points. The results in

Figure 7 indicate that the addition of iron powder can promote the solid-state reduction of chromite and improve the iron metallization rate; however, the improvement effect decreases with excessive addition of iron powder. This suggests that adding a moderate amount of iron powder has a significant positive impact on enhancing the iron metallization rate of chromite. There is an optimal value for the addition of iron powder, and in this study, 30% iron powder addition demonstrated the best performance. Beyond this point, the reduction promotion effect will weaken, and the reasons for this will be specifically discussed in

Section 3.4.

3.4. Mechanism of the Enhanced Solid-State Reduction of Chromite by Iron Powder Addition

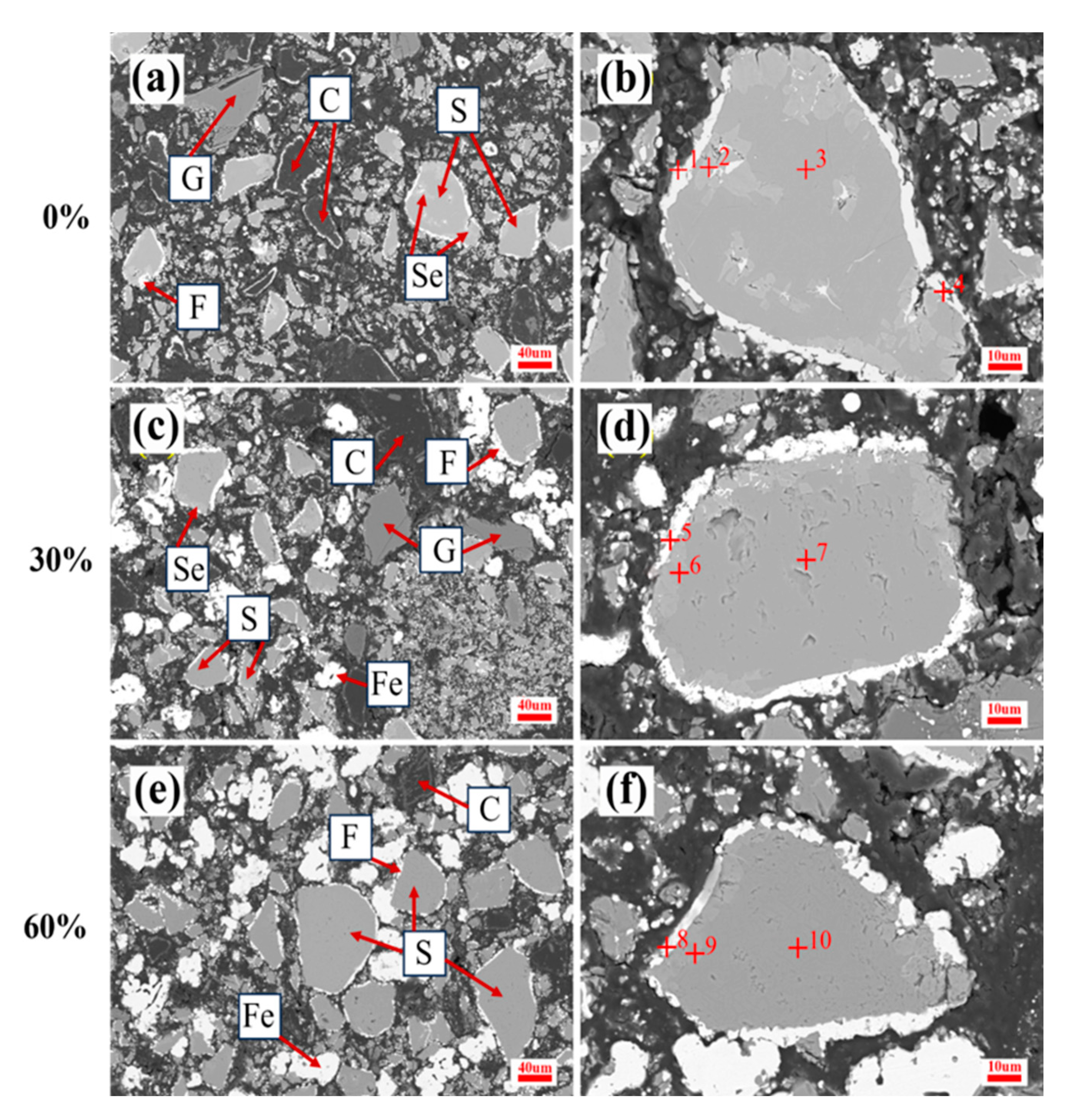

3.4.1. Microstructure Observation

The SEM-EDS analysis of the reduced samples with different iron powder contents at 1175 °C are presented in

Figure 8 and

Table 5.

Figure 8 (a) and (b) illustrate the microstructure of the reduced samples with 0% iron powder addition. The dark gray particles (S) represent Cr-rich spinel. Substances with a bright white color on the spinel surface, exhibiting spherical or bar-shaped morphologies, are identified as Fe-C-Cr alloys (points 1, 5, and 8). It can be concluded that the bar-shaped Fe-C-Cr alloys are formed through the aggregation of numerous spherical alloys. According to the EDS results, the primary elements present in the Cr-rich spinel include Cr, Mg, Al, O, along with a small amount of Fe. Combined with the XRD analysis shown in Fig. 10, the molecular formula of the unreduced Cr-rich spinel is determined to be (Mg, Fe)(Cr, Al)

2O

4, indicating that the Fe element within the spinel has not been fully reduced and a residual amount of Fe remains. In

Figure 8(b), light gray particles (point 2) can be observed near the edge or within the internal region of the spinel. Based on the EDS and XRD results, these particles are identified as sesquioxide ((Cr, Al)

2O

3), which forms as a result of spinel reduction.

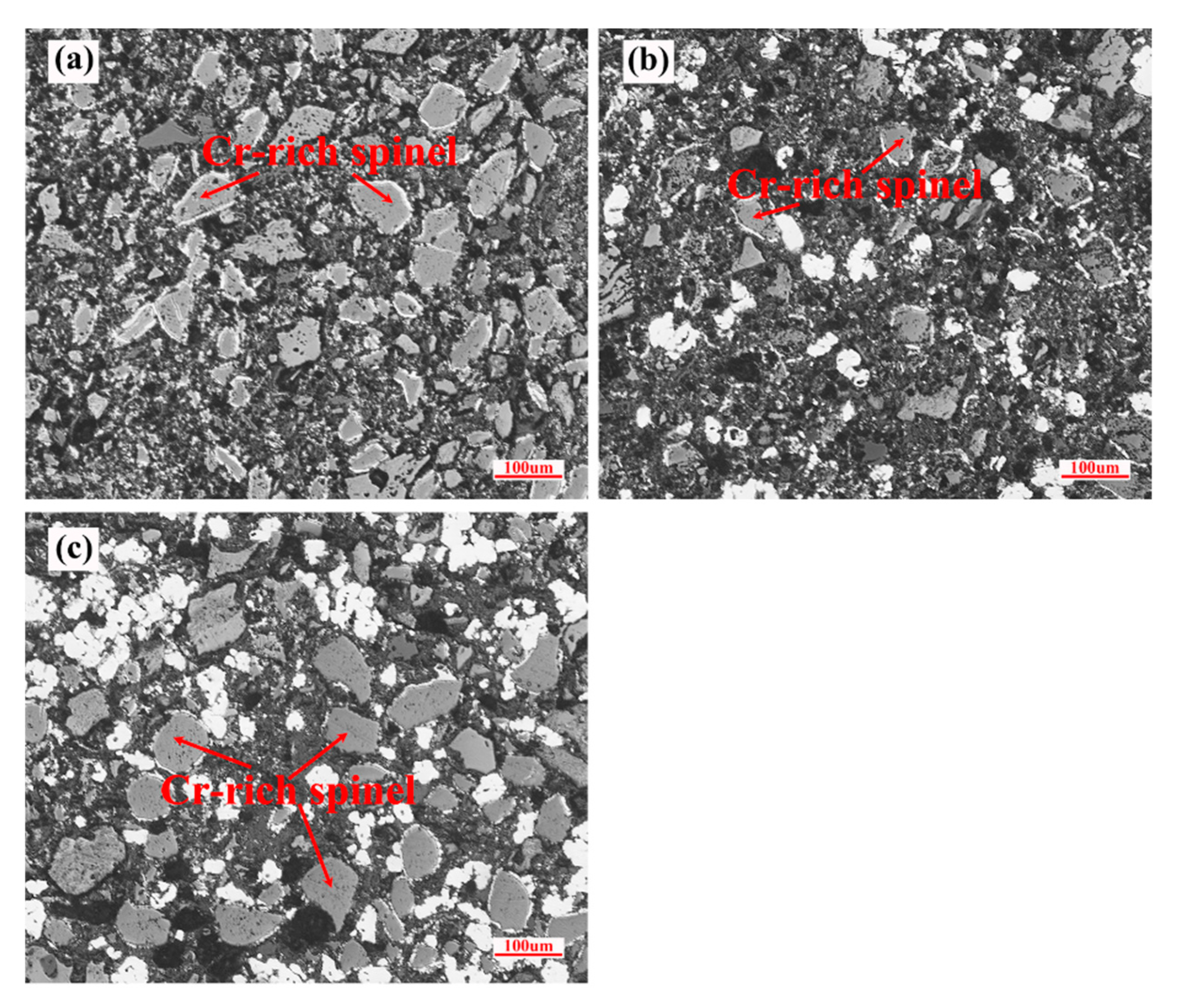

Figure 9 shows micrographs of samples with different amounts of iron powder added; grey particles are Cr-rich spinel. When 30% iron powder is added, the structure of the chromite spinel particles is severely damaged. The particle size continues to decrease, and the separated small chromite spinel particles continue to produce metallic iron through reduction, as shown in

Figure 9(b). This indicates that the addition of iron powder helps dissociate the spinel structure during the reduction process. Furthermore, it promotes the reduction reaction [

12]. A comparison of

Figure 8 (b) and (d) shows that the layer of Fe-C-Cr alloy at the edge of the spinel becomes more continuous and increases in thickness. This suggests that the reduction is more thorough and a large amount of Fe-C-Cr alloy continues to precipitate on the spinel surface. Zhao and Hayes point out that the metallic phase appears to be deposited where sesquioxide was previously formed. This preferential nucleation may be due to the absence of MgO, which would thermodynamically stabilize both the Fe phase and the spinel [

31]. It can be inferred that the presence of iron powder provides favorable kinetic conditions for the nucleation and growth of metallic iron.

A significant number of iron particles are densely arranged around the spinel particles when the iron powder content reaches 60%, as shown in

Figure 8(e), (f). The excess metal iron particles reduce the likelihood of carbon particles coming into contact with the spinel particles, thereby suppressing the direct reduction reaction to some extent [

30]. Compared to the sample with 30% iron powder added, the spinel particles are larger and more structurally intact. Additionally, the sesquioxide continues to decrease, which aligns with the experimental results presented in

Figure 8. Notably, based on the EDS and XRD results, composite carbides (Fe, Cr)

7C

3 were detected in the samples without iron powder, but were scarcely observed in the samples with iron powder.

In conclusion, the evolution of the spinel structure can be inferred through the reduction process. The incorporation of 30% iron powder resulted in substantial microstructural degradation of the chromite spinel, enhancing particle dissociation and consequently increasing the specific surface area for reaction, which facilitated the reduction reaction. Conversely, the addition of 60% iron powder exerted minimal damage to the chromite spinel structure and did not significantly reduce particle size, leading to a limited enhancement of the reduction reaction.

3.4.2. Mineral Phase Evolution

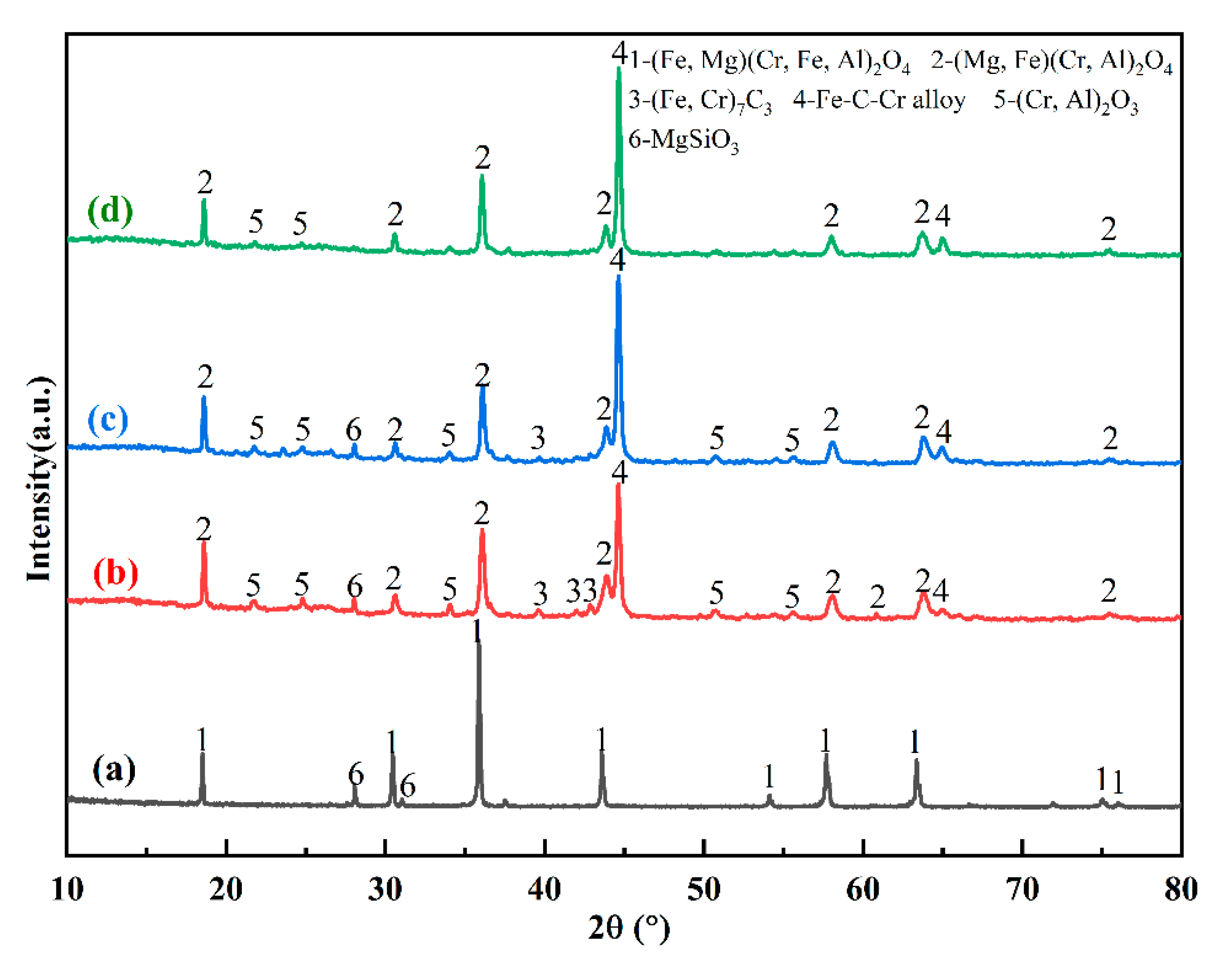

The mineral phase compositions of the original chromite and the samples with different iron powder additions were analyzed by XRD. The results are shown in

Figure 10. In the original chromite, the main mineral phase compositions are spinel ((Fe, Mg)(Cr, Fe, Al)

2O

4) and enstatite (MgSiO

3).

Comparing

Figure 10(a), (b), (c), and (d), it is evident that after the reduction of chromite ore, the spinel undergoes a transformation from pristine spinel (Fe, Mg)(Cr, Fe, Al)

2O

4 to Cr-rich spinel (Mg, Fe)(Cr, Al)

2O

4. This shift results in changes in the positions of the diffraction peaks due to alterations in chemical composition. As depicted in

Figure 10(b), the raw spinel was reduced without the addition of iron powder, yielding Cr-rich spinel, sesquioxide (Cr, Al)

2O

3, (Fe, Cr)

7C

3, and Fe-C-Cr alloy. Upon the introduction of iron powder, the Fe-C-Cr alloy content increased, while the sesquioxide and (Fe, Cr)

7C

3 gradually decreased. When the iron powder content reached 30%, the sesquioxide remained relatively abundant, whereas the (Fe, Cr)

7C

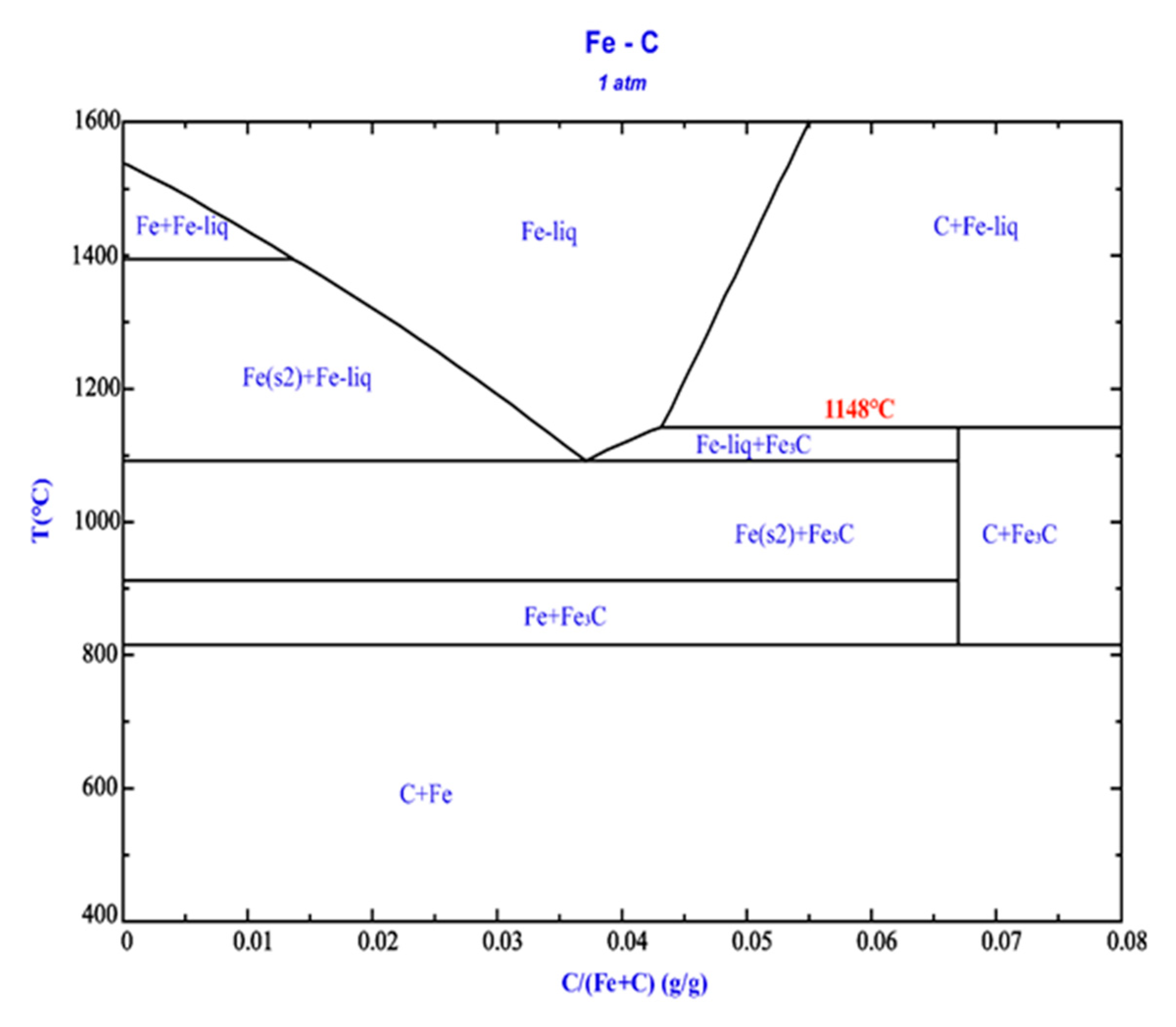

3 content was comparatively lower. The increase in Fe-C-Cr alloy can primarily be attributed to the initial reaction between the added iron powder and solid carbon, forming Fe

3C. According to

Figure 11, at temperatures exceeding 1148°C (the experimental temperature of 1175°C surpasses this threshold), a eutectic liquid phase forms through the interaction of Fe

3C and metallic iron. Consequently, newly formed metallic iron continues to dissolve in situ, reducing its reactivity. Additionally, iron particles serve as carbon carriers, enhancing direct reduction reactions and thereby promoting the reduction of chromite [

9,

31].

When the addition of iron powder reaches 60%, no carbide phase is detected in the XRD results, and the intensity of the sesquioxide peaks gradually decreases until it disappears, as shown in

Figure 10(d). The formation of sesquioxide leads to a change in the internal volume of the spinel, resulting in the cleavage of the spinel into smaller-grained spinel. However, with 60% iron powder, there is less sesquioxide, and therefore the spinel particles do not split into smaller ones, so the spinel particles are larger in size (as shown in

Figure 9).

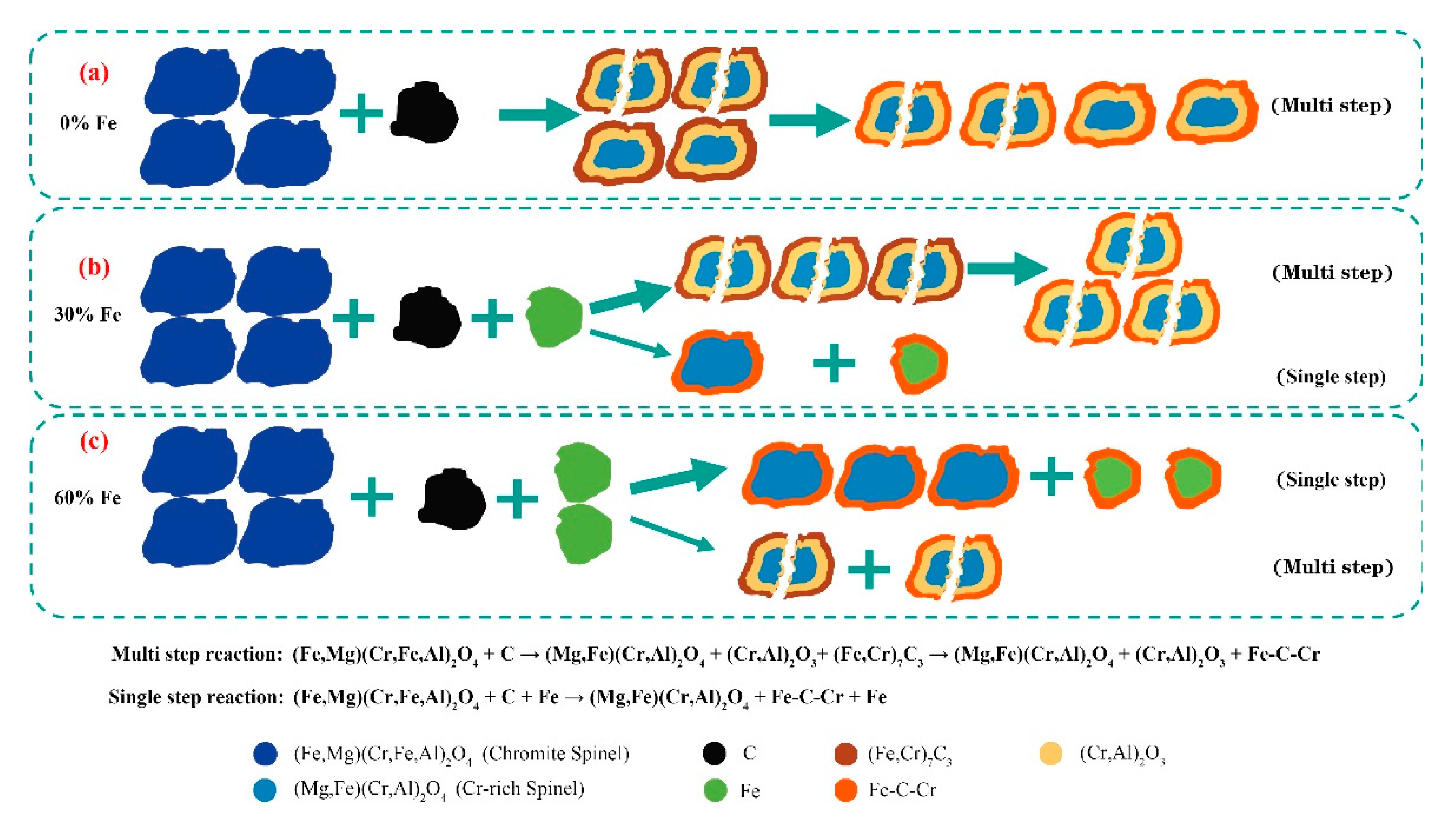

3.4.3. Reduction Process Analysis

The study analyzed the reduction process of chromite without added iron powder and found that this process was not a single step but involved multiple consecutive chemical reaction stages. The schematic diagram of the reaction process for chromite with different iron powder additions is shown in

Figure 12. Firstly, the main mineral component of chromite, spinel (Fe, Mg)(Cr, Fe, Al)

2O

4, reacts with carbon during the reduction process and gradually transforms into chromium-rich spinel (Mg, Fe)(Cr, Al)

2O

4. At this stage, the reaction primarily involves carbon capturing oxygen from the spinel structure, leading to the decomposition of spinel. Subsequently, the generated iron oxide continues to react with carbon in the reducing atmosphere and is reduced to metallic iron, eventually forming the Fe-C-Cr alloy. Meanwhile, chromium separates from the spinel structure in the form of (Cr, Al)

2O

3 rather than existing directly as a metal, which aligns with previous studies [

34,

35].

When the amount of added iron powder reaches 30%, the decomposition extent of chromite spinel increases, as shown in

Figure 12(b). During the reduction process, metallic iron particles initially come into contact with carbon, forming cementite (Fe

3C). Under conditions of high temperature and high carbon concentration, the cementite further reacts to form a eutectic liquid phase with metallic iron. The presence of this liquid phase plays a critical role in the reduction process: Firstly, it accelerates the dissolution of nascent iron, enabling newly formed metallic iron to rapidly integrate into the liquid phase. This reduces the activity of nascent iron and promotes the reduction reaction. Secondly, the liquid phase facilitates the diffusion and dispersion of carbon atoms, thereby inhibiting carbon aggregation on the surface of spinel particles and suppressing carbide formation [

36,

37]. These findings indicate that the addition of iron powder alters the chemical behavior of carbon during the reduction of chromite and reduces carbide formation. Moreover, the incorporation of iron powder significantly influences the microstructure of chromite. During reduction, large spinel particles progressively fracture into smaller ones, allowing the reduction reaction to proceed toward the center of the spinel particles.

However, when the addition amount of iron powder further increases (e.g., 60%), as shown in

Figure 12(c), the reduction mechanism of chromite changes, and the reaction shifts from being mainly multi step superimposed to being primarily a single step reaction. The sesquioxide produced by the decomposition of spinel gradually disappears, the microstructure changes little, and the spinel particle size remains intact; thus, the promoting effect on reduction decreases.

To sum up, when no iron powder is added, the solid-state reduction of chromite proceeds via multi step reactions, with intermediate products including sesquioxide (Cr, Al)2O3 and complex carbides (Fe, Cr)7C3. The volume change associated with the formation of sesquioxide facilitates the cracking of chromite spinel particles. The incorporation of metallic iron promotes the formation of a low-melting-point liquid phase of Fe-C alloy. This liquid phase suppresses the activity of newly formed iron, enhances the solid-state reduction reaction of chromite, accelerates the cracking of chromite spinel particles, increases the surface area for the reduction reaction, improves the kinetic conditions of the reaction, reduces the apparent activation energy of the reduction process, and expedites the formation of metallic iron. As the amount of iron powder added increases, the solid-state reduction of chromite gradually shifts from multi step reactions to single step reactions. Since single step reactions do not produce intermediate products such as sesquioxide, no significant volume changes occur in chromite spinel, and thus chromite spinel particles do not fragment into smaller particles. When the addition of iron powder exceeds 30%, the volume of chromite spinel particles progressively increases, leading to a reduction in the surface area available for the reduction reaction. Consequently, the reinforcing effect of metallic iron on the solid-state reduction of chromite diminishes.

4. Conclusions

(1) The optimal iron metallization rate of 97.15% was achieved under the following optimized parameters: 20 wt% carbon dosage, reduction temperature maintained at 1175°C, and a duration of 2h.

(2) The addition of iron powder can enhance the solid-state reduction of chromite ore, and the enhance effect first increases and then decreases with the increase in the amount of iron powder. The optimum addition of iron powder is 30 wt.% at a carbon dosage of 20% under isothermal reduction at 1175°C for 1.5 h, during which the iron metallization rate reaches 96.33%. Compared to chromite ore without iron powder, the iron metallization rate increases from 91.31% to 96.33.

(3) The addition of iron powder facilitates the generation of a low-melting Fe-C alloy liquid phase, the in-situ fusion of newly generated iron and the disintegration of chromite spinel particles, enhancing the solid-state reduction of chromite ore. When the iron powder dosage exceeds 30%, the re-duction reaction mechanism transitions from multi step reaction to single step reaction, which reduces the disintegration of chromite spinel particles and the enhancement effect of iron powder on the solid-state reduction of chromite ore.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.Z. and X.J.; methodology, X.J. and Y.C.; formal analysis, Y.C. and Z.L.; investigation, Z.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.Z and X.J.; writing—review and editing, F.Z and X.J.; visualization, Y.C. and Z.L.; supervision, F.Z.; funding acquisition, F.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52004075), Science and Technology Planning Projects of Guizhou Province (No. ZK[2021]262).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express sincere gratitude to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52004075) and the Science and Technology Planning Projects of Guizhou Province (No. ZK[2021]262) for their substantial support in facilitating this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhu, D.; Yang, C.; Pan, J.; etc. An integrated approach for production of stainless steel master alloy from a low grade chromite concentrate. Powder Technol 2018, 335, 103–113. [CrossRef]

- Murthy, Y.R.; Tripathy, S.K.; Kumar, C.R. Chrome ore beneficiation challenges & opportunities – A review. Miner Eng 2011, 24, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Yang, S.; Xue, X. Effect of Cr2O3 addition on oxidation induration and reduction swelling behavior of chromium-bearing vanadium titanomagnetite pellets with simulated coke oven gas. Int J Min Met Mater 2019, 26, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Jiang, Z.; Bao, C.; etc. The energy consumption and carbon emission of the integrated steel mill with oxygen blast furnace. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2017, 117, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, B.; Fang, Z.; etc. Energy and exergy analyses of pellet smelting systems of cleaner ferrochrome alloy with multi-energy supply. J Clean Prod 2021, 285, 124893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Ranganathan, S.; Sinha, S.N. Investigations on the carbothermic reduction of chromite ores. Metall Mater Trans B 2005, 36, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, S.; Chen, Z.; Sahoo, P.P.; etc. Kinetics of solid-state reduction of chromite overburden. International Journal of Minerals,Metallurgy and Materials 2023, 30, 2347–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neizel, B.W.; Beukes, J.P.; van Zyl, P.G.; etc. Why is CaCO3 not used as an additive in the pelletised chromite pre-reduction process? Miner Eng 2013, 45, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niayesh, M.J.F.G. In An assessment of smelting reduction processes in the production of Fe-Cr-C alloys., Proc. of the 4th International Ferroalloys Congress, Sao Paulo, Brazil, Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1986, pp. 115-123.

- Kleynhans, E.L.J.; Neizel, B.W.; Beukes, J.P.; etc. Utilisation of pre-oxidised ore in the pelletised chromite pre-reduction process. Miner Eng 2016, 92, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Yang, C.; Zhu, D. Solid State Reduction of Preoxidized Chromite-iron Ore Pellets by Coal. Isij Int 2015, 55, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apaydin, F.; Atasoy, A.; Yildiz, K. Effect of mechanical activation on carbothermal reduction of chromite with graphite. Can Metall Quart 2013, 50, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, H.V.; Johnston, R.F. Kinetics of solid state silica fluxed reduction of chromite with coal. Ironmak Steelmak 2000, 27, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, P.; Eric, R.H. The reduction of chromite in the presence of silica flux. Miner Eng 2006, 19, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasoy, A.; Sale, F.R. An Investigation on the Solid State Reduction of Chromite Concentrate. Solid State Phenomena 2009, 147-149, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, H.G. The Mechanism of Reduction of Chromic Oxide by Carbon. Journal of the Japan Institute of Metals 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deventer, J.S.J.V. The effect of additives on the reduction of chromite by graphite: An isothermal kinetic study. Thermochim Acta 1988, 127, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.L.; Warner, N.A. Catalytic reduction of carbon-chromite composite pellets by lime. Thermochim Acta 1997, 292, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neizel, B.W.; Beukes, J.P.; van Zyl, P.G.; etc. Why is CaCO3 not used as an additive in the pelletised chromite pre-reduction process? Miner Eng 2013, 45, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Paktunc, D. Kinetics and mechanisms of the carbothermic reduction of chromite in the presence of nickel. J Therm Anal Calorim 2018, 132, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wang, H.; Teng, L.; etc. Direct chromium alloying by chromite ore with the presence of metallic iron. J Min Metall B 2013, 49, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yang, Q.; Sundqvist Ökvist, L.; etc. Thermal Analysis Study on the Carbothermic Reduction of Chromite Ore with the Addition of Mill Scale. Steel Res Int 2016, 87, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhu, D.; Pan, J.; etc. Reduction of Carbon Footprint Through Hybrid Sintering of Low-Grade Limonitic Nickel Laterite and Chromite Ore. J Sustain Metall, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Teng, L.; Wang, H.; etc. Carbothermic Reduction of Synthetic Chromite with/without the Addition of Iron Powder. Isij Int 2016, 56, 2147–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, J.; etc. Kinetics of carbothermic reduction of synthetic chromite. J Min Metall B 2014, 50, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; etc. Hydrogen-based pre-reduction of chromite: Reduction and consolidation mechanisms. Int J Hydrogen Energ 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekatou, A.; Walker, R.D. Solid state reduction of chromite concentrate: Melting of prereduced chromite. Ironmak Steelmak 1995, 22, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gu, H.; Huang, A.; etc. Thermodynamic analysis and experimental verification of the direct reduction of iron ores with hydrogen at elevated temperature. J Mater Sci 2022, 57, 20419–20434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Peng, Z.; Tian, R.; etc. Efficient pre-reduction of chromite ore with biochar under microwave irradiation. Sustain Mater Techno 2023, 37, e00644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleynhans, E.L.J.; Beukes, J.P.; Van Zyl, P.G.; etc. The Effect of Carbonaceous Reductant Selection on Chromite Pre-reduction. Metall Mater Trans B 2017, 48, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.H.P.C. In Effects of oxidation on the microstructure and reduction of chromite pellets., The Twelfth International Ferroalloys Congress (INFACON XII), Outotec Oyj, Helsinki, Finland, Outotec Oyj, Helsinki, Finland, 2010, pp. 263-273.

- Hu, X.; Teng, L.; Wang, H.; etc. Carbothermic Reduction of Synthetic Chromite with/without the Addition of Iron Powder. Isij Int 2016, 56, 2147–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.Y.; Wang, L.J.; Liu, S.Y.; etc. Kinetic mechanism of FeCr2O4 reduction in carbon-containing iron melt. J Min Metall B 2023, 59, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.L.; Warner, N.A. Kinetics and mechanism of reduction of carbon-chromite composite pellets. Ironmak Steelmak 1997, 24, 224–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kekkonen, M. Kinetic study on solid state and smelting reduction of chromite ore. PhD. Type, Helsinki University of Technology, Espoo, 2000.

- Turkdogan, E.T.; Vinters, J.V. Gaseous reduction of iron oxides: Part III. Reduction-oxidation of porous and dense iron oxides and iron. Metallurgical Transactions 1972, 3, 1561–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkdogan, E. T., & Vinters, J. V. Reducibility of iron ore pellets and effect of additions. Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly, 12(1), 9–21. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

XRD analysis of raw chromite ore.

Figure 1.

XRD analysis of raw chromite ore.

Figure 2.

(a) Horizontal Tube Furnace, (b) Reduction Roasting Heating and Cooling Curve.

Figure 2.

(a) Horizontal Tube Furnace, (b) Reduction Roasting Heating and Cooling Curve.

Figure 3.

Variation curve of standard Gibbs free energy with reduction temperature.

Figure 3.

Variation curve of standard Gibbs free energy with reduction temperature.

Figure 4.

Effect of carbon dosage on solid state reduction(temperature:1150℃,time:2h).

Figure 4.

Effect of carbon dosage on solid state reduction(temperature:1150℃,time:2h).

Figure 5.

Effect of temperature on reduction results (carbon dosage:20%, time:2h).

Figure 5.

Effect of temperature on reduction results (carbon dosage:20%, time:2h).

Figure 6.

Effect of time on reduction results (carbon dosage:20%, temperature:1175℃).

Figure 6.

Effect of time on reduction results (carbon dosage:20%, temperature:1175℃).

Figure 7.

Effect of iron powder dosage on iron metallization rate (carbon dosage:20%, temperature:1175℃, time:1.5h).

Figure 7.

Effect of iron powder dosage on iron metallization rate (carbon dosage:20%, temperature:1175℃, time:1.5h).

Figure 8.

SEM-EDS analysis of reduced ore with different iron powder dosage. (S-Chromite spinel, Se- Sesquioxide, C-carbon, F-Fe-C-Cr alloy or (Fe, Cr)7C3, G-gangue;Fe-Metal iron).

Figure 8.

SEM-EDS analysis of reduced ore with different iron powder dosage. (S-Chromite spinel, Se- Sesquioxide, C-carbon, F-Fe-C-Cr alloy or (Fe, Cr)7C3, G-gangue;Fe-Metal iron).

Figure 9.

Micrographs of reduced samples ((a)without iron addition, (b)30wt% iron addition, (c)60wt% iron addition).

Figure 9.

Micrographs of reduced samples ((a)without iron addition, (b)30wt% iron addition, (c)60wt% iron addition).

Figure 10.

Influence of iron powder on the evolution of reduced chromite mineral phase ((a)raw chromite ore, (b)without iron addition, (c)30wt% iron addition, (d)60wt% iron addition).

Figure 10.

Influence of iron powder on the evolution of reduced chromite mineral phase ((a)raw chromite ore, (b)without iron addition, (c)30wt% iron addition, (d)60wt% iron addition).

Figure 11.

Fe-C phase diagram, generated using FactSage.

Figure 11.

Fe-C phase diagram, generated using FactSage.

Figure 12.

Mechanism diagram of the restoration process.

Figure 12.

Mechanism diagram of the restoration process.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of chromite concentrate / wt%.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of chromite concentrate / wt%.

| Raw materials |

TFe |

FeO |

Cr2O3

|

Ni |

SiO2

|

CaO |

Al2O3

|

MgO |

S |

P |

| Chromite concentrate |

21.68 |

20.81 |

41.32 |

0.03 |

3.16 |

0.27 |

14.56 |

8.98 |

0.081 |

0.005 |

Table 2.

Size composition of chromite particle after grinding /%.

Table 2.

Size composition of chromite particle after grinding /%.

| Raw materials |

0.074-0.15mm |

0.045-0.074mm |

-0.045mm |

| Chromite concentrate |

9.43 |

36.80 |

53.77 |

Table 4.

Reduction and roasting trial conditions.

Table 4.

Reduction and roasting trial conditions.

| Num. |

Temperature/°C |

Time/h |

Carbon dosage/% |

iron powder dosage/% |

| 1 |

1150 |

2 |

5 |

0 |

| 2 |

10 |

| 3 |

15 |

| 4 |

20 |

| 5 |

25 |

| 6 |

1100 |

2 |

20 |

0 |

| 7 |

1125 |

| 8 |

1150 |

| 9 |

1175 |

| 10 |

1200 |

| 11 |

1175 |

0.5 |

20 |

0 |

| 12 |

1 |

| 13 |

1.5 |

| 14 |

2 |

| 15 |

2.5 |

| 16 |

1175 |

1.5 |

20 |

10 |

| 17 |

20 |

| 18 |

30 |

| 19 |

40 |

| 20 |

50 |

| 21 |

60 |

Table 3.

Carbon composition and properties /%.

Table 3.

Carbon composition and properties /%.

| Ash |

Volatile matter |

dropout voltage |

Fixed carbon |

sulfur |

abrasion |

| 10.51 |

0.92 |

98.3 |

87.3 |

0.51 |

7.6 |

Table 5.

EDS results of SEM in

Figure 8.

Table 5.

EDS results of SEM in

Figure 8.

| powder dosage/% |

Area No. |

Elemental compositions/mass pct. |

mineral phase |

| C |

O |

Mg |

Al |

Si |

Ca |

Cr |

Fe |

| 0%Fe |

1 |

10.26 |

0.58 |

0.12 |

0.01 |

0.06 |

0 |

9.24 |

79.75 |

(Fe, Cr)7C3

|

| 2 |

0.37 |

35.69 |

0.23 |

13.77 |

0 |

0.07 |

49.53 |

0.34 |

Sesquioxide |

| 3 |

0.26 |

35.82 |

11.68 |

9.69 |

0 |

0.03 |

39.48 |

3.30 |

Cr-rich spinel |

| 4 |

6.14 |

0.45 |

0 |

0.04 |

0.11 |

0.06 |

9.37 |

83.82 |

Fe-C-Cr alloy |

| 30%Fe |

5 |

5.91 |

0.22 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.10 |

0.03 |

9.16 |

84.55 |

Fe-C-Cr alloy |

| 6 |

0.36 |

34.97 |

0.16 |

13.77 |

0.04 |

0.08 |

49.97 |

0.66 |

Sesquioxide |

| 7 |

0.41 |

33.94 |

10.53 |

10.98 |

0 |

0.01 |

40.82 |

3.04 |

Cr-rich spinel |

| 60%Fe |

8 |

5.73 |

0.34 |

0 |

0.05 |

0.03 |

0 |

7.95 |

85.9 |

Fe-C-Cr alloy |

| 9 |

3.8 |

30.27 |

0.07 |

12.16 |

0 |

0 |

53.06 |

0.64 |

Sesquioxide |

| 10 |

3.94 |

30.56 |

8.21 |

11.34 |

0.06 |

0.01 |

41.13 |

4.75 |

Cr-rich spinel |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).