1. Introduction

Introducing millimetre-wave (mmWave) frequencies into South Africa's 5G wireless networks presents an opportunity to meet the increasing demand for faster data speeds, greater bandwidth, and minimal latency [

1,

2]. mmWave bands, particularly at 28 GHz, promise exceptional speed and capacity, and are therefore critical to future-proofing the 5G wireless network. The 28 GHz band supports dense urban deployments with higher data rates. However, using these high frequencies presents challenges, particularly rain attenuation, which can significantly degrade signal quality [

3,

4,

5].

In 5G mmWave networks, incorporating actual rain attenuation into the link budget is essential for accurate path loss estimation, especially for Urban Micro (UMi) and Urban Macro (UMa) cell links. Path loss directly affects the maximum distance between the User Equipment (UE) and the Base Station (BS), as it determines the strength of the received signal relative to the sensitivity of receiver. Smaller UMi cells, covering shorter distances of 10–500 meters, are highly sensitive to variations in path loss, while larger UMa cells covering distances of up to a few kilometres, require a more robust link to handle the interference and attenuation. Rain attenuation, which is significant at mmWave frequencies, intensifies path loss, limiting signal range and potentially reducing cell coverage.

To ensure acceptable quality of service in 5G mobile networks, it is important to maintain a received power level above the minimum threshold. This threshold is typically defined by the minimum signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) [

6,

7]. To achieve sufficient SNR at the receiver, link budgeting is used to account for all power gains and losses during signal transmission [

8]. A key component of the link budget is path loss, which measures the reduction in signal strength due to factors such as physical obstructions, weather conditions, and geographical features. Rain attenuation has a significant impact on the link budget in 5G mmWave wireless communications, especially because the wavelengths of mmWave frequencies are comparable to the size of raindrops, which can cause significant signal degradation through absorption and scattering [

9,

10,

11,

12]. By integrating realistic rainfall data, the link budget enables a more reliable assessment of channel status and ensures that the signal strength (RxSL) exceeds the receiver sensitivity (RxS). This coordination between path loss, rain attenuation, and receiver sensitivity enables optimized cell design and supports effective 5G deployment across diverse environments.

Rain attenuation affects the design and performance of short-range and fixed wireless links by increasing path loss and requiring adjustments to parameters such as transmit power, antenna gain, and site placement. When planning a network, it is essential to account for these losses within the link budget to ensure reliable service, especially in areas with heavy or frequent rainfall.

Models such as the ITU-R P.838 are often used to predict attenuation caused by rain and incorporate these estimates into the link budget to ensure that performance remains within acceptable limits despite adverse weather conditions. In regions with light rain, a small fade margin is typically sufficient to overcome challenges of rain in 5G mmWave networks. However, South African cities experience frequent thunderstorms [

13] during summer, leading to significant rain attenuation even over short distances, such as those between UE and BS in urban micro-cell scenarios. Fixed power margins are often impractical due to limited power availability, the highly variable nature of rainfall in the region, and safety concerns. Consequently, adaptive fade mitigation techniques, such as dynamic power control, hierarchical modulation, data rate reduction, and diversity methods, are more effective in addressing these variations. Because signal attenuation caused by rain is very dynamic and location-specific, real-time attenuation prediction is critical to optimize mitigation strategies balancing coverage and capacity and ensuring the feasibility and efficiency of mmWave based 5G networks.

This study estimates rain-induced attenuation in South African cities using available rain data. Rain rates with a 60-minute integration time are converted to their one-minute equivalents, and attenuation values at 28 GHz are calculated. The analysis focuses on 5G links in Urban Micro (UMi) and Urban Macro (UMa) deployments in Pretoria. The assessment of 5G coverage involves calculating the maximum allowable path loss on the radio interface through a link budget analysis. This process evaluates path loss for downlink transmissions in both UMi and UMa scenarios while identifying potential network design challenges [

14], such as limited coverage.

To plan 5G mmWave deployments in Pretoria, the urban environment is categorized into UMi and UMa scenarios to meet different coverage and capacity requirements. In UMi scenarios, small cells are strategically positioned at heights of 4 to 10 meters, typically on streetlights or building facades, to provide high-capacity, low-latency connectivity in densely populated areas such as Pretoria CBD and Sunnyside. These locations are characterized by heavy pedestrian and vehicular traffic, requiring the use of mmWave technology and beamforming to mitigate signal attenuation and blockages caused by buildings.

Conversely, UMa cells are deployed at greater heights, such as on rooftops or dedicated towers ranging from 25 to 50 meters high, to provide wider coverage in areas such as Hatfield or suburban areas. These cells ensure reliable connectivity over larger areas and complement the targeted, high-density coverage provided by UMi deployments. By integrating UMi and UMa scenarios, the network design achieves an optimized spectrum efficiency, overcomes line-of-sight challenges, and supports a wide range of applications from enhanced mobile broadband to IoT use cases.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 discusses related work and provides context on rain attenuation and its impact on the propagation of 5G mmWave wireless networks.

Section 3 introduces the Moupfouma rain attenuation model and explains its application in the study. Path loss is analysed in

Section 4, followed by a discussion of the link budget in

Section 5. Results and analysis are presented in

Section 6, highlighting key findings. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper and summarizes findings and implications for 5G network planning.

2. Related Work

The influence of atmospheric conditions on 5G cellular communications in urban microcell environments has been the focus of several studies. For example, [

15] investigates the significant impact of path loss, particularly at higher frequencies, on signal reception and overall network performance. The study identifies meteorological factors such as temperature, humidity and rain as major causes of increased path loss, leading to increased signal attenuation and reduced network reliability. Particular emphasis is placed on the importance of frequency selection, with 7.125 GHz identified as a relatively stable option. However, challenges persist regarding the cumulative effects of atmospheric conditions and the limitations of millimetre waves for long-distance applications. Similarly, [

16] evaluates the performance of a millimetre wave 5G (mmWave) system in Banda Aceh city by simulating the path loss under line-of-sight propagation (LOS) and non-line-of-sight propagation (NLOS) models. The results show that path loss plays a critical role in determining 5G network performance, with increased signal attenuation and reduced coverage and reliability observed particularly in NLOS scenarios. These findings highlight the need for careful urban deployment planning to mitigate such challenges. In [

17], a modified path loss model is proposed to account for the differences between clear and rainy air conditions based on outdoor microcellular measurements at 26 and 32 GHz. The study introduces a dynamic rain cell model for multi-user systems to analyse the overall impact of rain attenuation. The results indicate that the parameters of the floating intercept (FI) model shift significantly compared to the close-in (CI) model under different rainfall intensities. In addition, larger rain cell radii lead to higher path loss exponents, negatively affecting system capacity, particularly in higher frequency bands. The study also highlights the influence of rain cell speed on path loss and system performance. [

18] investigates the impact of rainfall on the propagation of 5G mmWave channels in urban environments and on highways scenarios. The study examines attenuation, path loss and link margin at different frequencies. The results indicate that as path difference and rain rate increase, path loss increases while link margin decreases, with the effect being more pronounced at higher frequencies. To address these challenges, a particle swarm optimization approach is employed, achieving 94% accuracy and demonstrating an improved signal propagation and overall system performance.

3. Rain Attenuation

This section analyses the impact of rain attenuation on path loss and 5G mmWave signal propagation in selected South African cities, with a focus on outdoor LOS and NLOS paths. The estimated rain attenuation for Pretoria is used to calculate path loss and determine the link budget for Umi and Uma links.

The Moupfouma model [

19] is used to predict rainfall attenuation and provides realistic values tailored to the diverse climate zones of South Africa. The country experiences variable weather conditions, and includes dry regions and areas with frequent rainfall. Rain rates are influenced by seasonal changes, such as the summer thunderstorm rainfall in the eastern and northern regions and the winter rainfall in the Western Cape. These climatic variations impact the intensity and frequency of rainfall, making accurate modelling essential for effective 5G network planning in urban and rural scenarios. The Moupfouma model [

19] improves the prediction of rainfall attenuation in tropical regions by recalibrating the coefficients to reflect local rainfall intensity and variability. This approach enhances forecast accuracy by incorporating tropical-specific features such as higher rainfall rates and droplet sizes.

Rain rate data collected in South African provinces originally based on 60-minute integration time is converted to a 1-minute integration time to analyze the impact of rainfall on terrestrial link design for 5G mmWave networks. The attenuation values for different provinces are then calculated using the method described in [

19] Moupfouma Path attenuation A

0.01 model is mathematically represented as shown in Equation (1).

represents the specific rain attenuation (dB/km) at percentage of time

.

is the rain rate at the corresponding percentage of time

.

is the effective path length over which the rain propagation is considered uniform.

is the reduction factor coefficient and

the actual path length in km.

can be expressed as (3)

where

m is a coefficient that depends on the path length

and the carrier frequency

in GHz.

The coefficient

can be obtained as in the following equation:

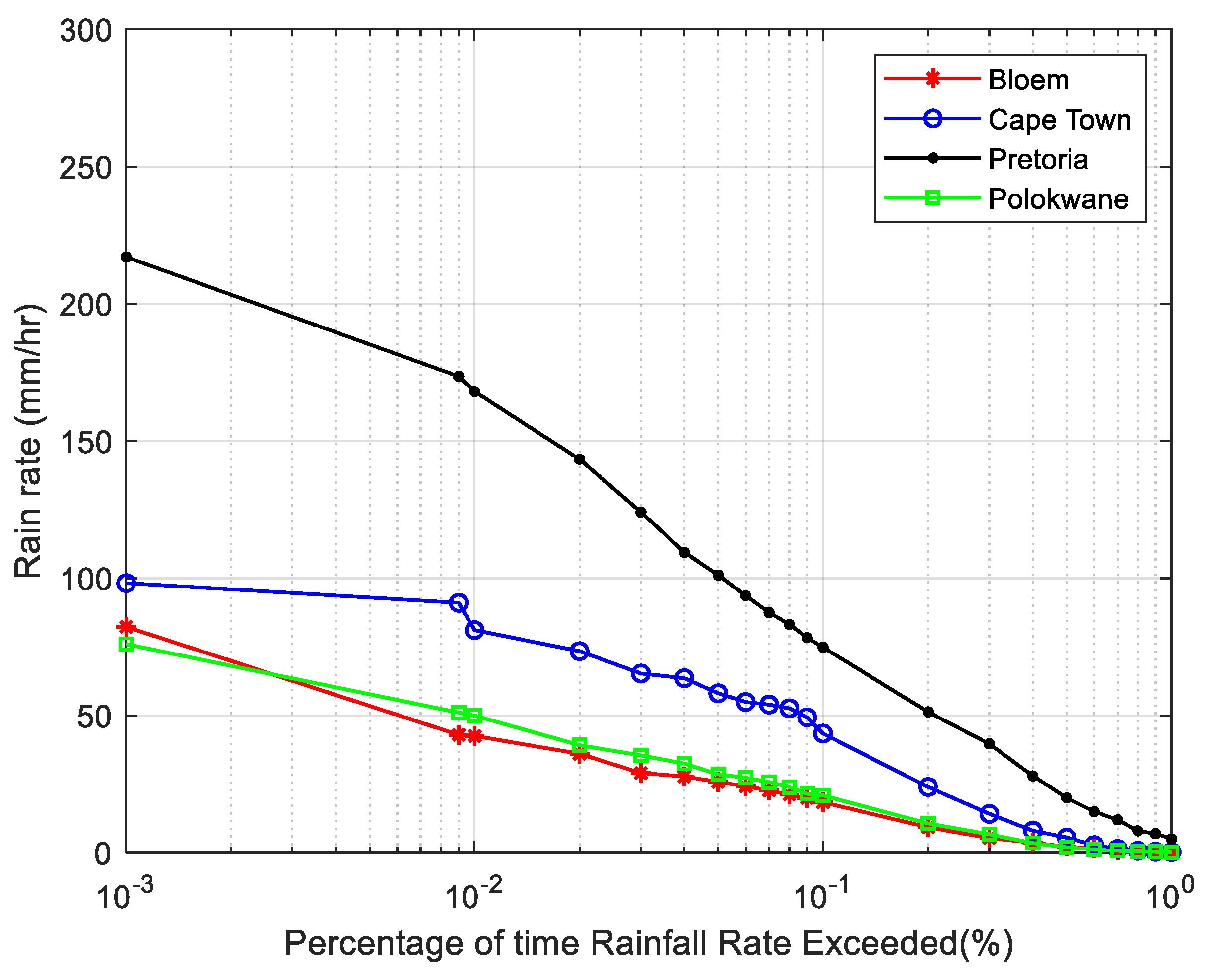

Figure 1 shows the rainfall statistics for selected cities in South Africa. Pretoria recorded the highest rainfall rate at 0.01% exceedance, with 168.5 mm/h, while Bloemfontein recorded the lowest rainfall rate at 42.58 mm/h. Polokwane, and Cape Town have R

0.01 values of 49.9 mm/h, and 81.13 mm/h, respectively. All the cities experience thunderstorms which are characterised by rainfall rate above 40mm/h.

Figure 2 shows the attenuation (dB/km) at different rain intensities. Drizzle with 0.25 mm/h causes minimal attenuation, remaining below 1 dB at all frequencies. widespread rain of 5 mm/h results in attenuation of less than 10 dB. In contrast, showers with rain rate of 25 mm/h and thunderstorms with rain rate of 100 mm/h have significant impacts across all frequencies. The attenuation caused by thunderstorms exceeds 10 dB, highlighting the serious impact of heavy rainfall on signal propagation, especially in high frequency bands.

4. Path Loss

This paper examines the effect of rainfall on path loss in UMa and UMi Line-of-Sight and Non-Line-of-Sight scenarios. Given the high population density and significant data needs in urban areas, the focus is on these environments. UMi cells, designed for high traffic in compact areas such as city streets, typically cover ranges from 100 to a few hundred meters, ensuring low latency connections. In contrast, UMa cells serve larger areas, with a span of several hundred meters to a few kilometres, effectively supporting higher mobility and mitigating interference from urban obstacles. The path losses (PL) are estimated using the Close-In (CI) path loss model, with a reference distance of 1 m [

20] as shown in Equation (6):

where

,

isthe Gaussian random variable with zero mean and a standard deviation δ (in dB). The Free Space Path Loss (FSPL) is given by (7):

where

λ is the wavelength (in m).

The Close-In (CI) model is a simple path loss model that uses a single parameter, the Path Loss Exponent (PLE), that conforms to physical principles. CI model provides a conservative estimate of non-line-of-sight path loss over long distances and applies free-space path loss at a reference distance of 1 meter to improve stability and accuracy [

20]. In contrast, the Alpha-Beta-Gamma (ABG) model requires three parameters, provides slightly better accuracy, lacks a direct physical basis, and predicts lower path loss near the transmitter but higher loss at greater distances [

21]. The CI model offers significant simplicity and achieves reasonable accuracy across various environments and frequency bands. Its minimal parameter requirement and reliance on a physical based approach make it a practical choice for various communication scenarios. For UMa and UMi scenarios, the standard deviations

σ of the Gaussian variables are 4.6, 10, 2.9, and 8.1 dB for UMa LOS, UMa NLOS, UMi LOS, and UMi NLOS, respectively.

5. Link Budget

The link budget estimates the maximum allowable path loss for 5G UMi and UMa scenarios in Pretoria, considering an average rain rate of 48 mm/h and a maximum of 168.5 mm/h and the parameters listed in

Table 1 and

Table 2. The link budget evaluates the system performance taking into account all gains and losses at the transmitter, receiver and propagation medium. Additionally, realistic rain attenuation values to provide a more accurate approximation of total path loss under different environmental conditions.

Currently, most 5G networks use the N28 and N78 frequency bands in SA with maximum channel bandwidth of 10 and 50 for each band respectively. This study presents the results obtained with the N257 CA configuration with 200 MHz carrier bandwidth.

In the link budget calculation process, input parameters are categorized into two types: variable parameters and scenario-specific parameters. Variable parameters include factors such as transmit power, number of transmit antennas, antenna gain, body loss, and SINR. Scenario-specific parameters include elements such as the standard deviation of shadow fading, penetration loss, effective height of base station and mobile station antennas, among others. These parameters are compiled into a structured table, which serves as the basis for computing the downlink link budget for a 28 GHz frequency band. The calculations are carried out for single-antenna setups in urban micro (UMi) and urban macro (UMa) scenarios. The cell radius ranges from 10 to 500 meters for UMi and from 50 to 2000 meters for UMa, reflecting the differing coverage requirements of these environments. The BS and UE 5G RAN parameters used for the simulation are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2 respectively.

Channel Status

The feasibility of the Umi and Uma 5G links are assessed based on the signal strength and system requirements using the link budget. This process calculates the received signal level (RxSL) and compares it to the receiver sensitivity (RxS), the minimum acceptable signal strength. The channel status “Pass” is assigned If RxSL outperforms RxS, indicating a robust link; otherwise, it is marked as “Failed”. Critical factors affecting this evaluation include transmission power, path loss, and antenna gains, which collectively impact communications reliability and performance as shown in Equations (8) to (11):

Tx Power is the transmitted power level of the signal, Gains(dB) is the combined gains in the system, including antenna gain and any amplifier gains. The total signal losses, including path loss, shadowing, penetration loss, cable loss, the estimated rain attenuation and any other attenuation factors is represented by Losses(dB).

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Path Loss

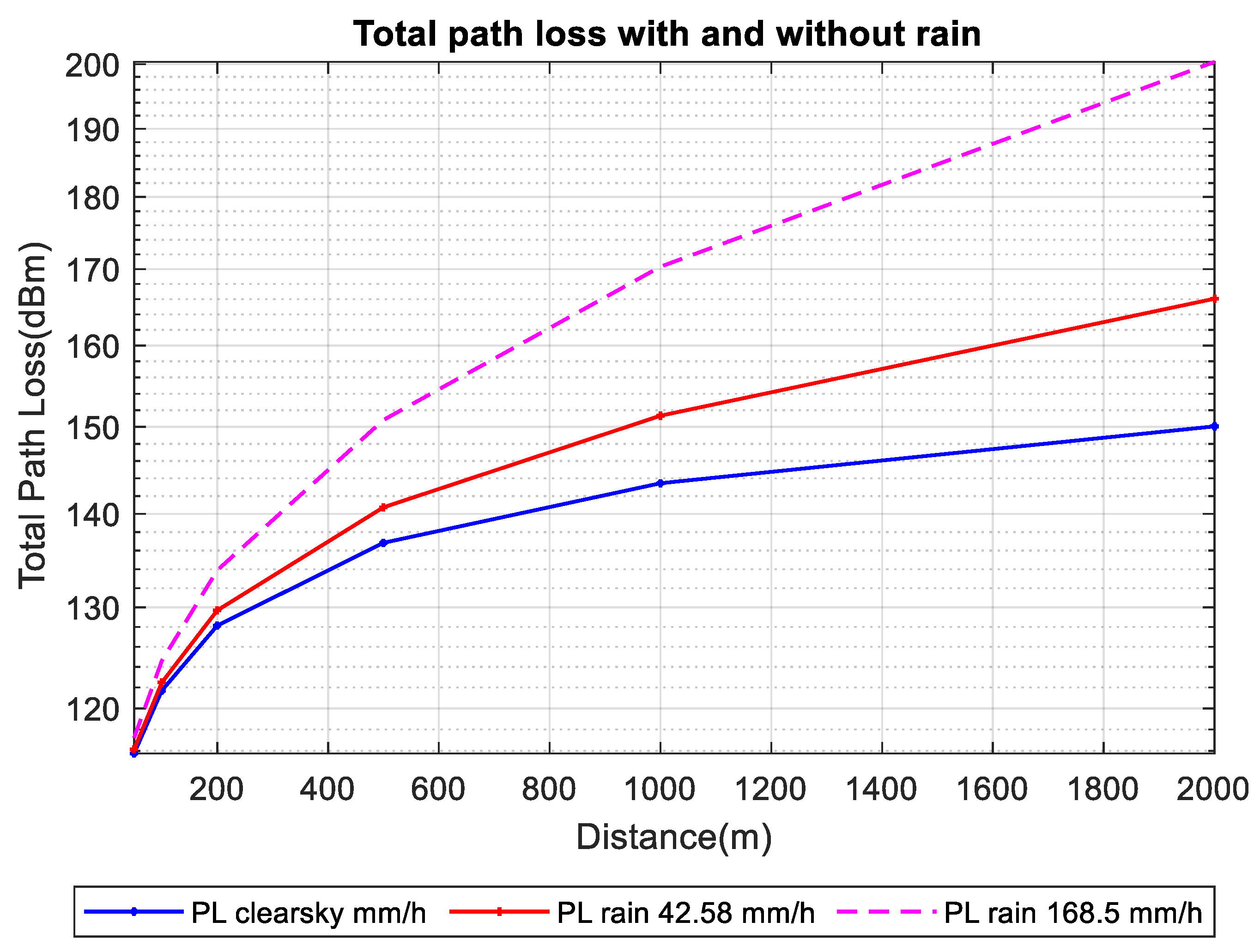

The total path loss is shown in

Figure 3. The graph shows the increasing trend of path loss with increasing distance due to signal attenuation over longer transmission paths. When the sky is clear, the path loss gradually increases. However, rain significantly increases the path loss, as shown by the path loss during rain with rainfall intensities of 42.58 mm/h and 168.5 mm/h. For shorter distances the percentage increase in path losses due to rain is relatively small and is often less than 1%. For example, with a clear sky path loss of 115 dB, the increase under rain is 0.33% for 50 m at a rain rate of 42.58 mm/h, showing negligible degradation at shorter distances or light rain intensities. As the distance increases, the percentage increase in path loss becomes more noticeable; With a clear sky path loss of 136.83 dB, the percentage increase under rain reaches 2.85% and 10.22%, at 42.8 mm/h and 168.5 mm/h, respectively. At greater distances, especially in heavy rainfall conditions, the percentage increase becomes significant. For example, with a clear sky path loss of 150.07 dB, the increase under rain conditions reaches 10.67% at 42.8 mm/h and escalates to 33.5% at 168.5 mm/h.

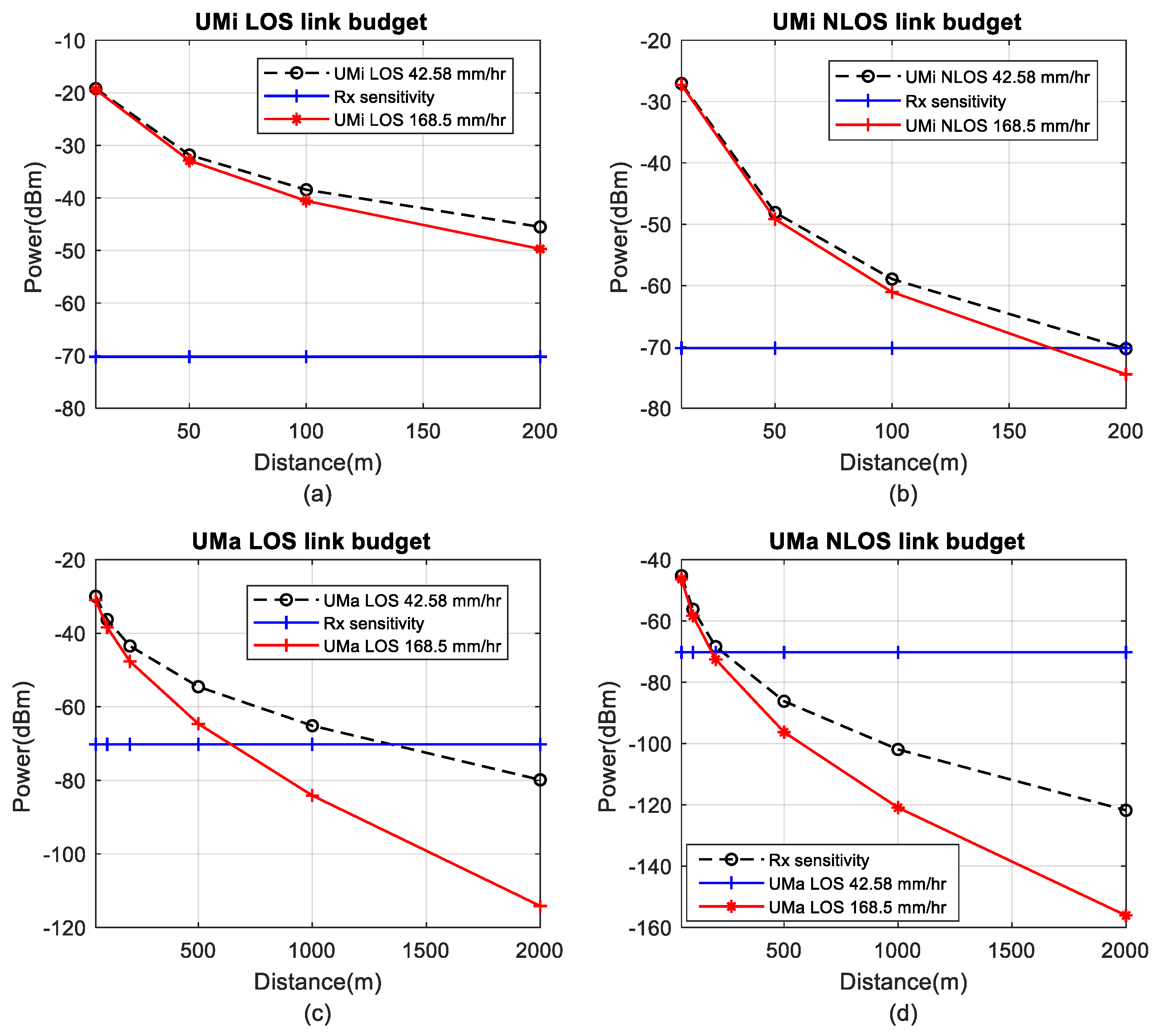

6.2. Link Budget

Figure 4 illustrates the differences between LOS and NLOS links and highlights the significant impact of rain on link budgets. LOS links provide better performance than NLOS links due to lower signal interference. However, for both types there is a decrease in link budgets with increasing distance. Higher rainfall intensities (42.58 mm/h to 168.5 mm/h) increase this deterioration, especially in NLOS links. The receiver sensitivity of -70.21 dB defines the minimum signal power required for the receiver to effectively detect and process the signal. This sensitivity depends on factors such as thermal noise, bandwidth and the required signal-to-noise ratio. Performance below this threshold results in errors. For UMi LOS links, the link budget remains above the receiver sensitivity threshold at distances of up to 200 m, even at rain intensities of 42.58 mm/h and 168.5 mm/h. In contrast, UMi-NLOS links start with a lower link budget and further degrade as rain intensity increases. At a rain rate of 42.58 mm/h, the UMi NLOS link reaches the minimum signal power threshold at 200 m. At 168.5 mm/h, this threshold is reached at approximately 170 m. For UMa links, both LOS and NLOS configurations have negative link budgets at short distances and at both rain rates, which pose significant challenges for reliable communication. At 42.58 mm/h the UMa LOS link budget falls below the receiver sensitivity threshold at 1300 m, while at 168.5 mm/h this occurs at 650 m. In NLOS settings, the UMa link budget falls below the threshold at approximately 190 m for 42.58 mm/h and at 200 m for 168.5 mm/h. At 2000 m, the link budget for both UMa-LOS and NLOS configurations is approximately 40 dB lower than the link budget at 42.58 mm/h.

6.3. LOS and NLOS Impact

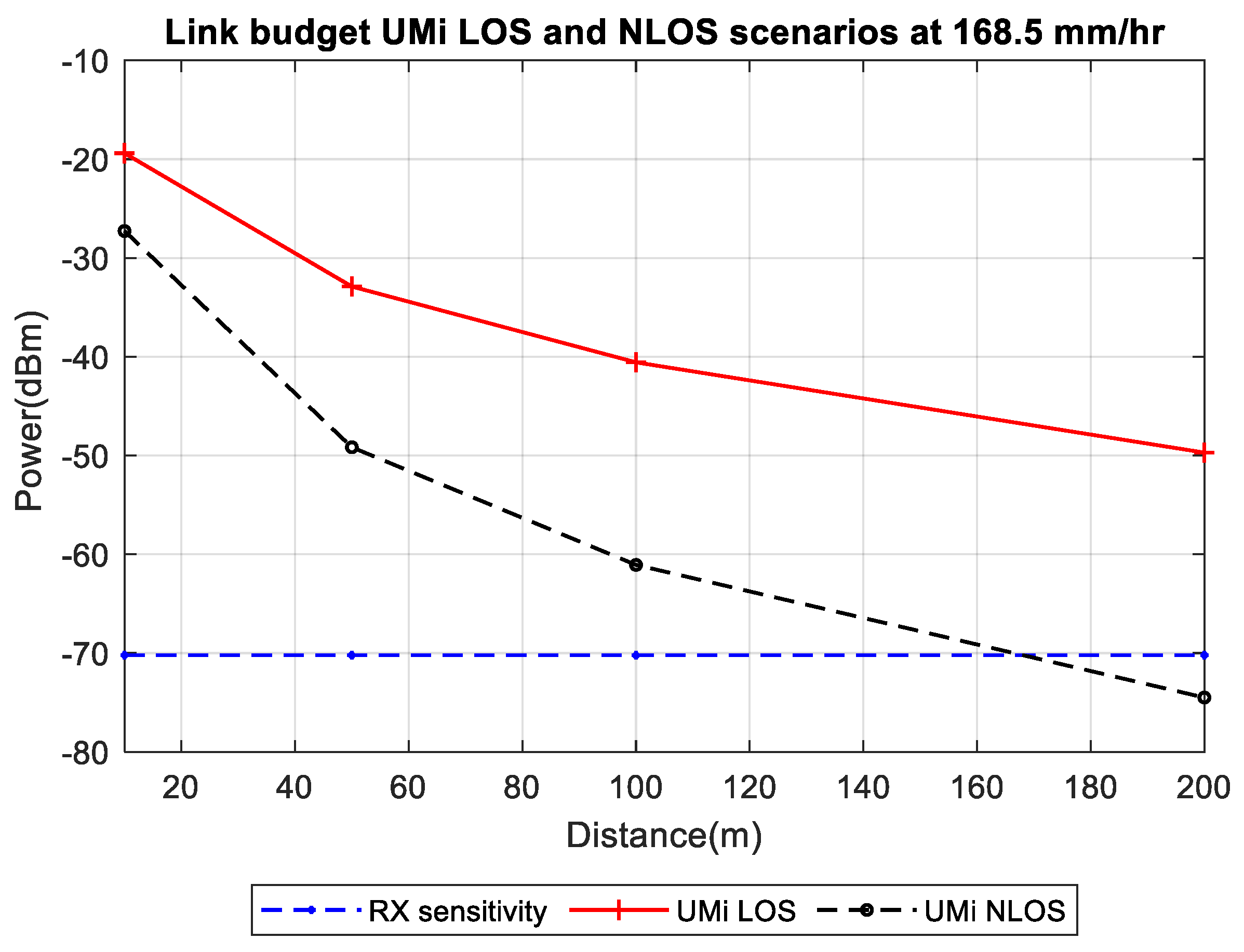

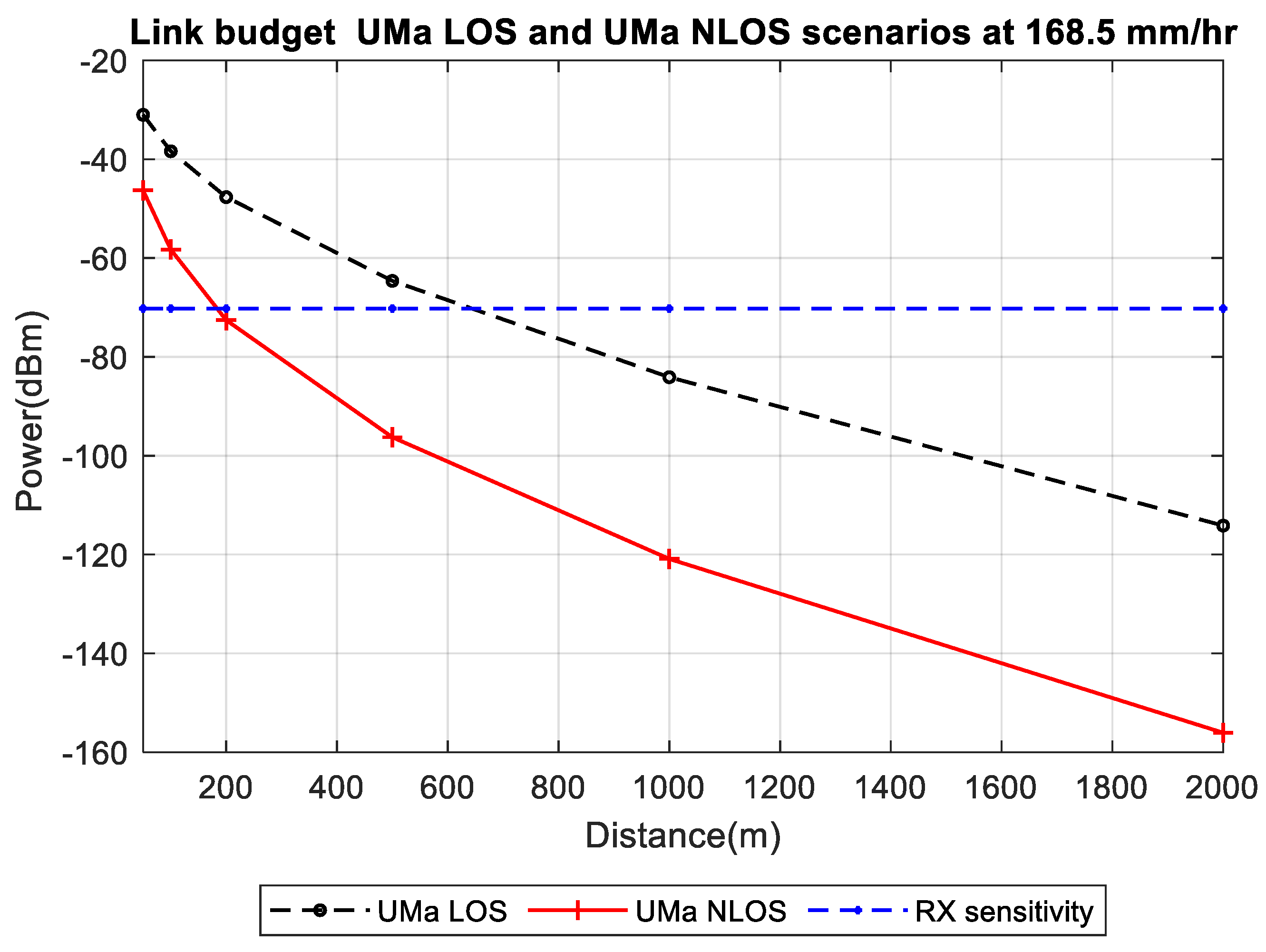

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 compare the link budgets of UMa and UMi environments with receiver sensitivity under the influence of rain-induced attenuation at a rain rate of 162.08 mm/h.

Figure 5 shows the link budgets for LOS and NLOS scenarios in a UMi environment along with the receiver sensitivity threshold. The link budget decreases linearly with distance in both scenarios due to the loss of the free space path. However, in the NLOS scenario, the performance decreases faster than in the LOS case, which is probably due to additional losses due to diffraction, reflection and shadowing. At a link distance of 200 meters and a rain rate of 168.5 mm/h, the UMi LOS link remains above the receiver's sensitivity threshold, ensuring a strong and reliable connection. Even under these conditions, which result in a rain attenuation of 5.7 dB, the LOS connection remains functional. In contrast, the UMi NLOS link budget drops below the receiver sensitivity threshold after 160 meters, marking the maximum range for reliable communications in this configuration at the same rain rate.

Figure 6 shows the link budget as a function of distance for UMa-LOS and NLOS conditions. The received power in the NLOS scenario drops significantly faster than in the LOS scenario due to higher free space path loss and additional attenuation factors.

At a rain rate of 168.5 mm/h, the NLOS link budget falls below the receiver sensitivity threshold at approximately 200 meters, while the LOS link remains functional up to approximately 600 meters. These distances represent the maximum reliable communication ranges for UMa NLOS and LOS links under these conditions. Beyond these distances, received power drops below -70 dBm, resulting in link failure if no countermeasures are taken.

7. Conclusions

This study highlights the significant impact of rain attenuation on path loss and link budgets for potential 5G mmWave deployments in Pretoria, South Africa, at 28 GHz. Path loss increases with distance and rainfall intensity, with negligible effects at short ranges but significant degradation over longer distances, particularly under heavy rainfall. Link budget analysis shows that LOS links consistently outperform NLOS links, maintaining functionality at greater distances. In UMi scenarios, LOS links remain operational up to 200 meters under heavy rain, while NLOS links fail beyond 160 meters. In UMa scenarios, LOS links support communication up to 600 meters, while NLOS links are limited to approximately 200 meters under similar conditions. At distances of 2000 meters, the link budget for both UMi and UMa scenarios deteriorates sharply, with path loss increases of up to 33.5% in heavy rainfall. These findings emphasize the importance of rain attenuation in planning 5G mmWave networks. UMi deployments can achieve reliable connectivity with careful placement of small cells, while UMa deployments require advanced techniques, such as beamforming, advanced error correction, and network densification, to address significant rain-induced losses.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.M.; investigation, S.B.M.; methodology, S.B.M., P.A.O.; software, S.B.M; supervision, P.A.O.; validation, S.B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

the author declares that all the data are provided in the article text

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5G |

Fifth Generation (Mobile Network Technology) |

| mmWave |

Millimetre Wave |

| GHz |

Gigahertz |

| LOS |

Line-of-Sight |

| NLOS |

Non-Line-of-Sight |

| UE |

User Equipment |

| BS |

Base Station |

| UMi |

Urban Microcell |

| UMa |

Urban Macrocell |

| RxSL |

Received Signal Level |

| RxS |

Receiver Sensitivity |

| SNR |

Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| ITU-R |

International Telecommunication Union – Radiocommunication Sector |

| CI Model |

Close-In Path Loss Model |

| FI Model |

Floating Intercept Path Loss Model |

| A₀.₀₁ |

Specific Attenuation Exceeded for 0.01% of the Time |

| dB |

Decibel |

References

- Cox, C. An introduction to 5G: the new radio, 5G network and beyond; John Wiley & Sons: west Sussex, UK, 2020; pp. 1–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Lee, N. Introduction to 5G and beyond. In 5G and Beyond: Fundamentals and Standards, (eds)Springer, Cham, 2021; p. 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Ojo, J.; Ajewole, M; Sarkar, S. Rain rate and rain attenuation prediction for satellite communication in Ku and Ka bands over Nigeria. Pier B 2008, 5, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isabona, J.; Imoize, A. L.; Rawat, P.; Jamal, S. S.; Pant, B.; Ojo, S.; Hinga, S. K. Realistic prognostic modeling of specific attenuation due to rain at microwave frequency for tropical climate region. WCMC 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.S.; Siat, L.J.; Hong, Y.L. Atmospheric impairments and mitigation techniques for high-frequency earth-space communication system in heavy rain region: A brief review. IJIE 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananya, S.T.; Islam, S.; Mahmud, A.R.; Podder, P.K.; Uddin, J. Atmospheric propagation impairment effects for wireless communications. Int. J. Wirel. Mob. Netw, 2020, 12, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, A.J.; Varaiya, P.P. Capacity of fading channels with channel side information. IEEE transactions on information theory 1997, 43, 1986–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3GPP, 3rd Generation Partnership Project Technical Specification Group Radio Access Network Study on channel model for frequencies from 0.5 to 100 GHz (Release 18). In TR38.9012024. p. 98.

- Li, X.; Xie, L.; Zheng, X. The comparison between the Mie theory and the Rayleigh approximation to calculate the EM scattering by partially charged sand. JQSRT 2012, 113, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wriedt, T. Mie theory: a review. In The Mie Theory: Basics and Applications; Springer Series in Optical Sciences; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; Volume 169, pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohren, C.F.; Huffman, D.R. Absorption and scattering of light by small particles; John Wiley & Sons, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Recommendation, I. , Prediction methods required for the design of terrestrial free-space optical links. International telecommunication Union, 2007, p. 1814.

- Afullo, T.J.O. Raindrop size distribution modeling for radio link design along the eastern coast of South Africa. Pier B 2011, 34, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, T.S.; MacCartney, G. R.; Sun, S.; Yan, H.; Deng, S. Overview of millimeter wave communications for fifth-generation (5G) wireless networks—With a focus on propagation models. In IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, 17; vol. 65, no. 12, pp. 6213–6230. 20 December. [CrossRef]

- Ratul, R.H.; Zaman, S.M.; Chowdhury, H.A.; Sagor, M.Z.H.; Kawser, M.T.; Nishat, M.M. Atmospheric influence on the path loss at high frequencies for deployment of 5g cellular communication networks. In 2023 14th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Delhi, India, 6-. 8 July. [CrossRef]

- Yunida, Y.; Maulana, A.; Nasaruddin, N. Performance Analysis of Pathloss Model for 5G mm Wave Communication System at 24 GHz, 30 GHz, and 32 GHz. In 2023 2nd International Conference on Computer System, Information Technology, and Electrical Engineering (COSITE), Banda Aceh, Indonesia, 2-. 3 August. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, Q.; Geng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. Path loss modification and multi-user capacity analysis by dynamic rain models for 5G radio communications in millimetre waves. IET Communications 2019, 13, 1488–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuan, L.L.; Roslee, M. B.; Sudhamani, C.; Mousa I. M.S.; Waseem, A.; Osman, A. F.; Zaharah A.F.; Ullah, Y. Impact of Rainfall on 5G Millimeter Wave Channels. Pier C, 2024; 148, 97–107. [CrossRef]

- Moupfouma, F. , Electromagnetic waves attenuation due to rain: A prediction model for terrestrial or LOS SHF and EHF radio communication links. J Infrared Milli Terahz Waves 2009, 30, 622–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, T.S.; MacCartney, G. R.; Samimi, M. K.; Sun, S. Wideband millimeter-wave propagation measurements and channel models for future wireless communication system design. In IEEE Transactions on communications, 15, vol 63(9), pp. 3029-3056. 20 September. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Rappaport, T. S.; Rangan, S.; Thomas, T. A.; Ghosh, A.; Kovacs, I. Z.; Rodriguez, I.; Koymen, O.; Partyka, A.; Jarvelainen, J. Propagation path loss models for 5G urban micro-and macro-cellular scenarios. In 2016 IEEE 83rd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC Spring), Nanjing, China,15-. 18 May. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).