Submitted:

29 February 2024

Posted:

01 March 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Site | Latitude N (°) | Longitude E (°) | (m) | Rain Rate Observation Time (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spino d’Adda (Italy) | 45.4 | 9.5 | 84 | 8 |

| Gera Lario (Italy) | 46.2 | 9.4 | 210 | 5 |

| Fucino (Italy) | 42.0 | 13.6 | 680 | 5 |

| Madrid (Spain) | 40.4 | 356.3 | 630 | 8 |

| Prague (Czech Republic) | 50.0 | 14.5 | 250 | 5 |

| Tampa (Florida) | 28.1 | 277.6 | 50 | 4 |

| Norman (Oklahoma) | 35.2 | 262.6 | 420 | 4 |

| White Sands (New Mexico) | 32.5 | 253.4 | 1463 | 5 |

| Vancouver (British Columbia) | 49.2 | 236.8 | 80 | 3 |

2. The Method to Download Clear–Sky Data Volume during Rainfall

2.1. Channel Efficiency

2.2. Power Margin and Bandwidth Expansion

3. Link Efficiency in Zenith Paths

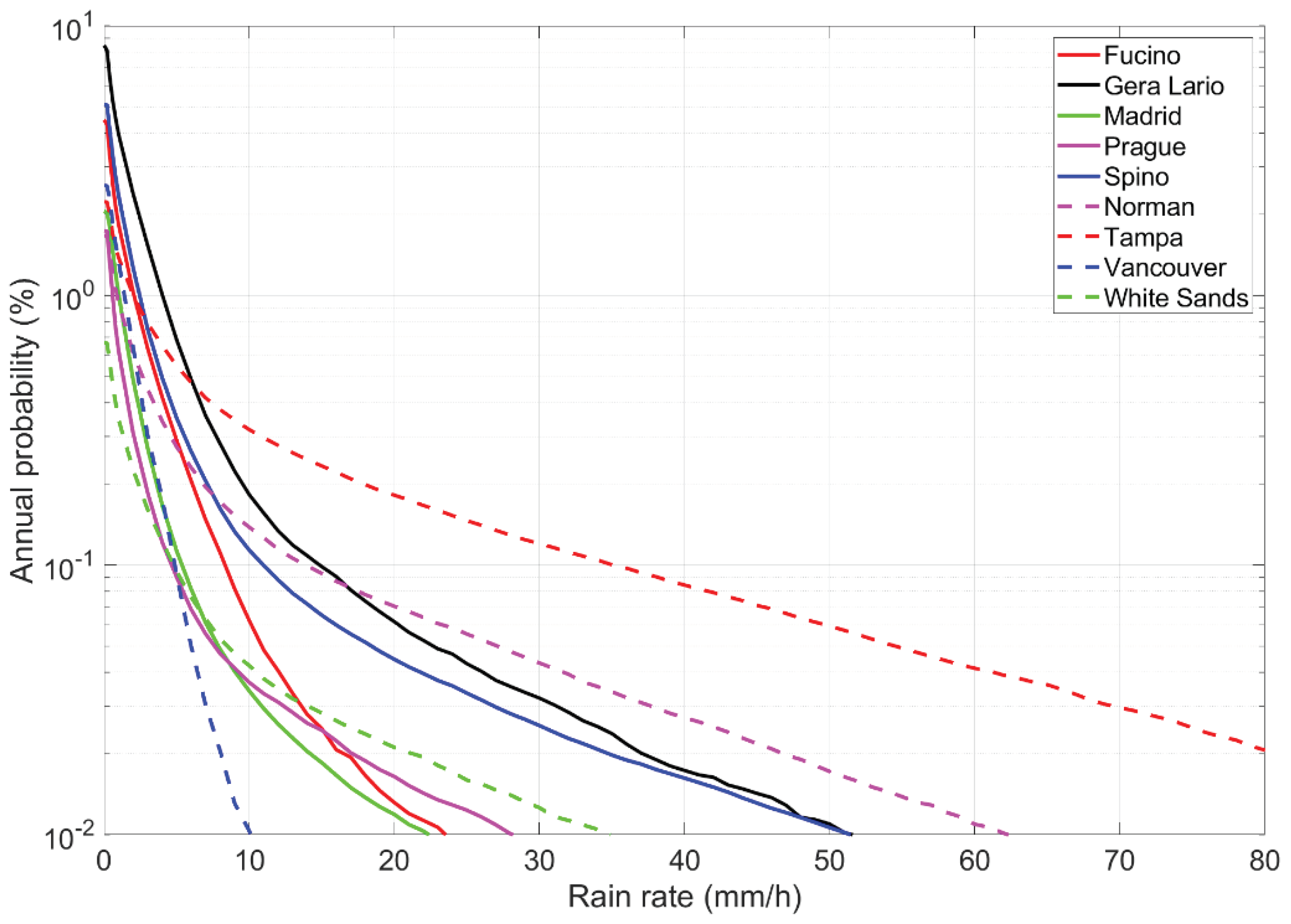

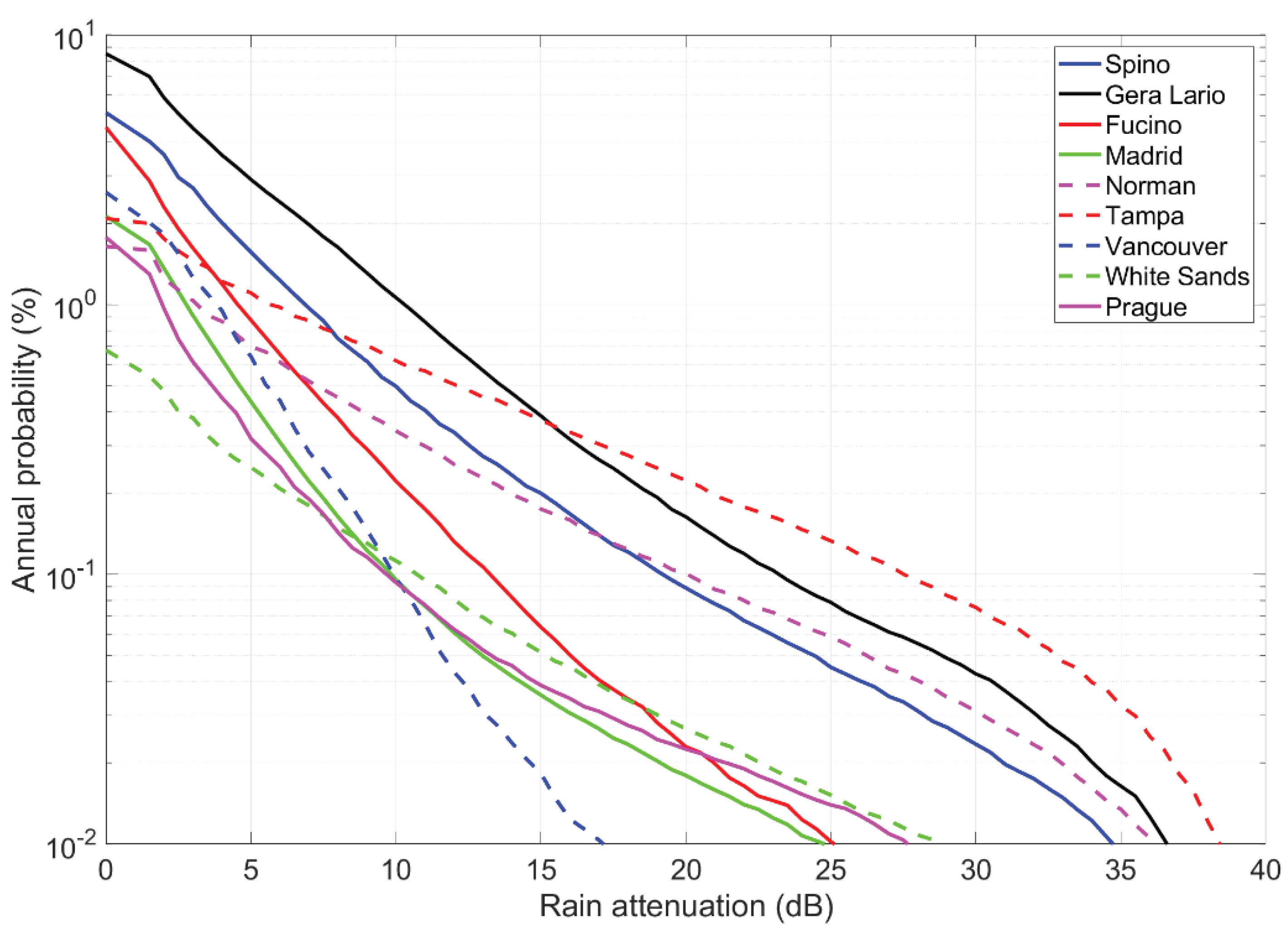

3.1. Probability Distributions , and Channel Efficiency

| Site | Minimum | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| Spino d’Adda (Italy) | 0.378 | 0.403 |

| Gera Lario (Italy) | 0.358 | 0.386 |

| Fucino (Italy) | 0.483 | 0.502 |

| Madrid (Spain) | 0.444 | 0.458 |

| Prague (Czech Republic) | 0.473 | 0.492 |

| Tampa (Florida) | 0.221 | 0.265 |

| Norman (Oklahoma) | 0.282 | 0.318 |

| White Sands (New Mexico) | 0.338 | 0.377 |

| Vancouver (British Columbia) | 0.421 | 0.431 |

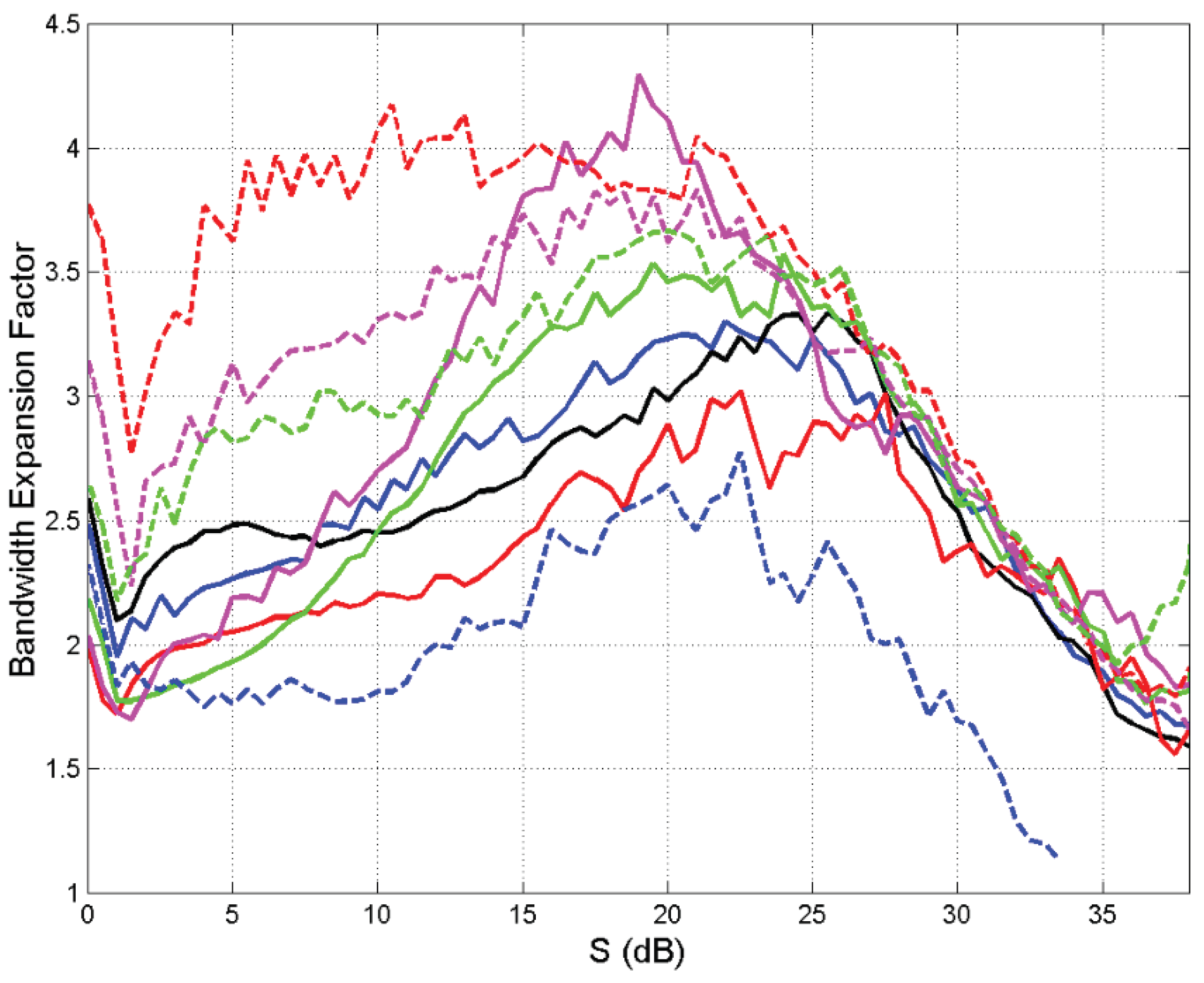

| Site | Maximum | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| Spino d’Adda (Italy) | 4.21 | 3.95 |

| Gera Lario (Italy) | 4.46 | 4.13 |

| Fucino (Italy) | 3.16 | 2.99 |

| Madrid (Spain) | 3.53 | 3.39 |

| Prague (Czech Republic) | 3.25 | 3.08 |

| Tampa (Florida) | 6.56 | 5.76 |

| Norman (Oklahoma) | 5.50 | 4.97 |

| White Sands (New Mexico) | 4.71 | 4.24 |

| Vancouver (British Columbia) | 3.76 | 3.66 |

| Site | Maximum | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| Spino d’Adda (Italy) | 2.64 | 2.48 |

| Gera Lario (Italy) | 2.80 | 2.59 |

| Fucino (Italy) | 2.07 | 1.99 |

| Madrid (Spain) | 2.25 | 2.18 |

| Prague (Czech Republic) | 2.11 | 2.03 |

| Tampa (Florida) | 4.53 | 3.77 |

| Norman (Oklahoma) | 3.55 | 3.14 |

| White Sands (New Mexico) | 2.96 | 2.66 |

| Vancouver (British Columbia) | 2.38 | 2.32 |

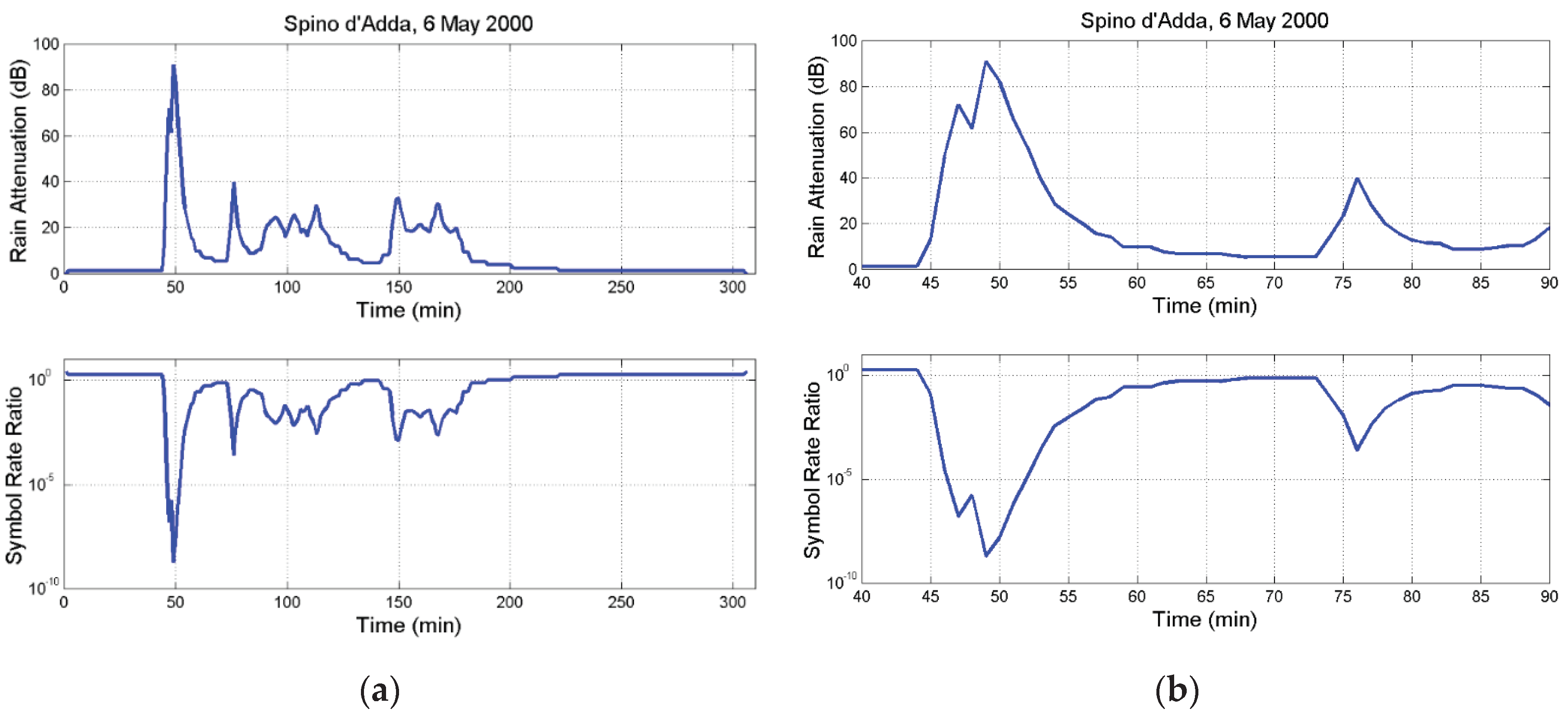

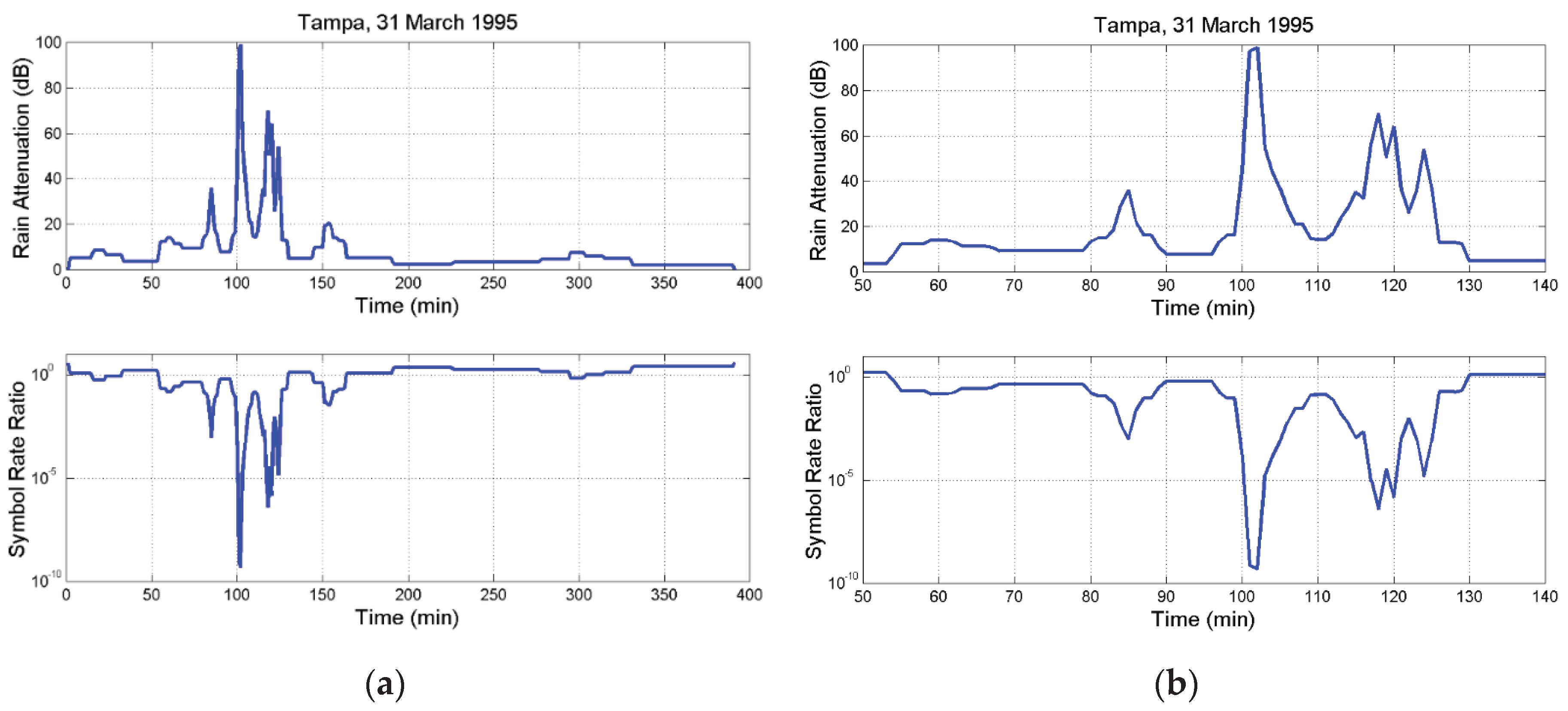

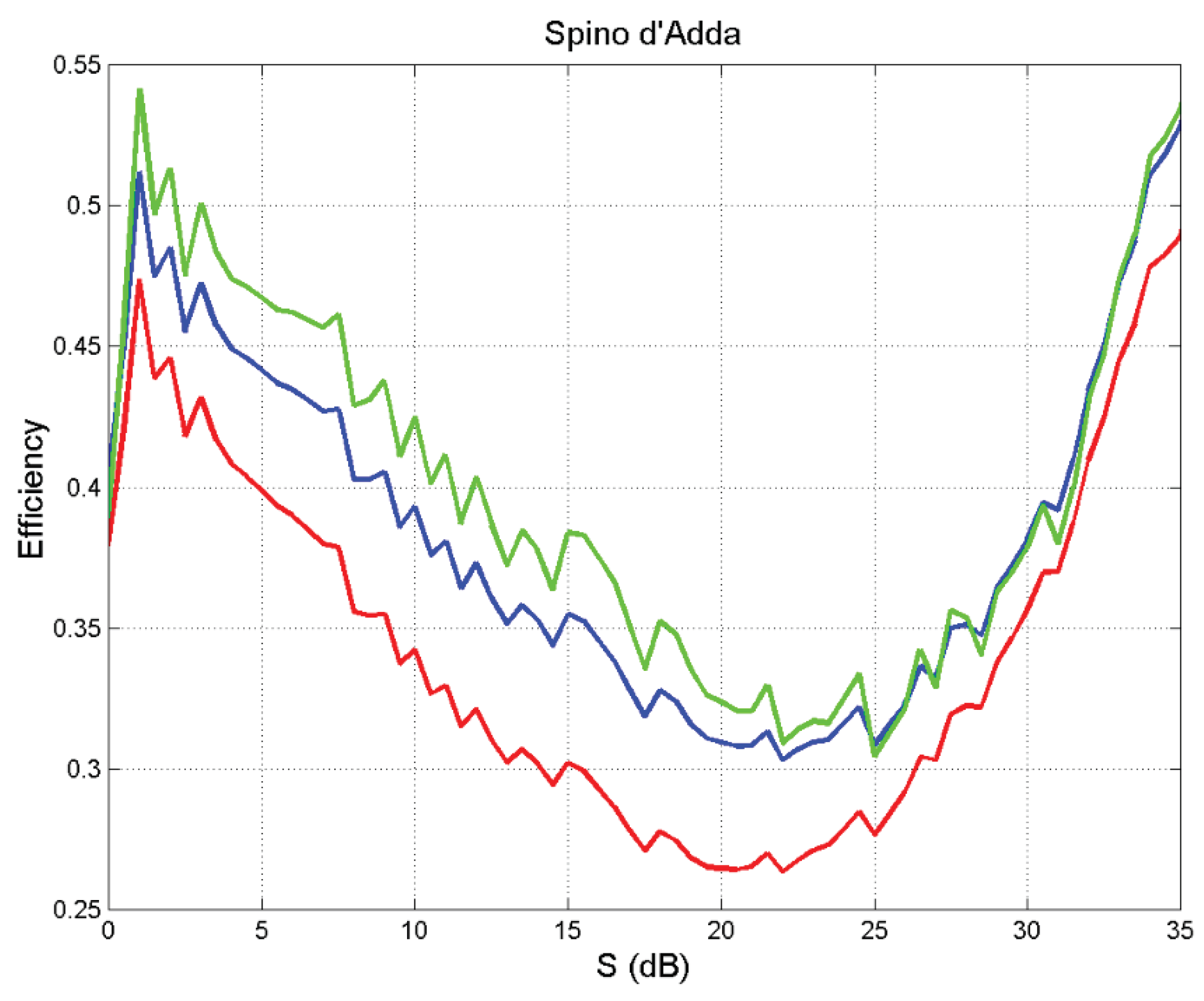

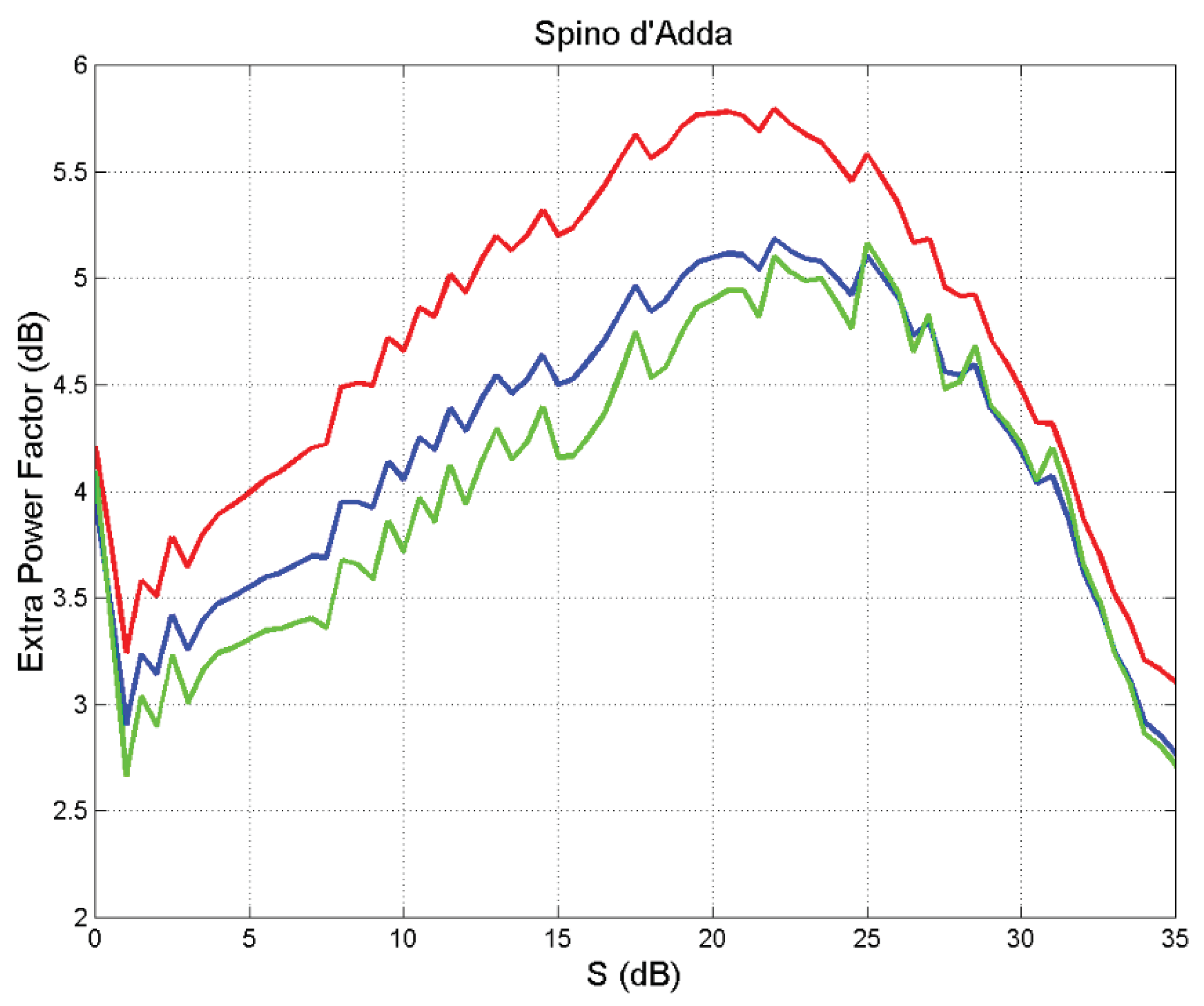

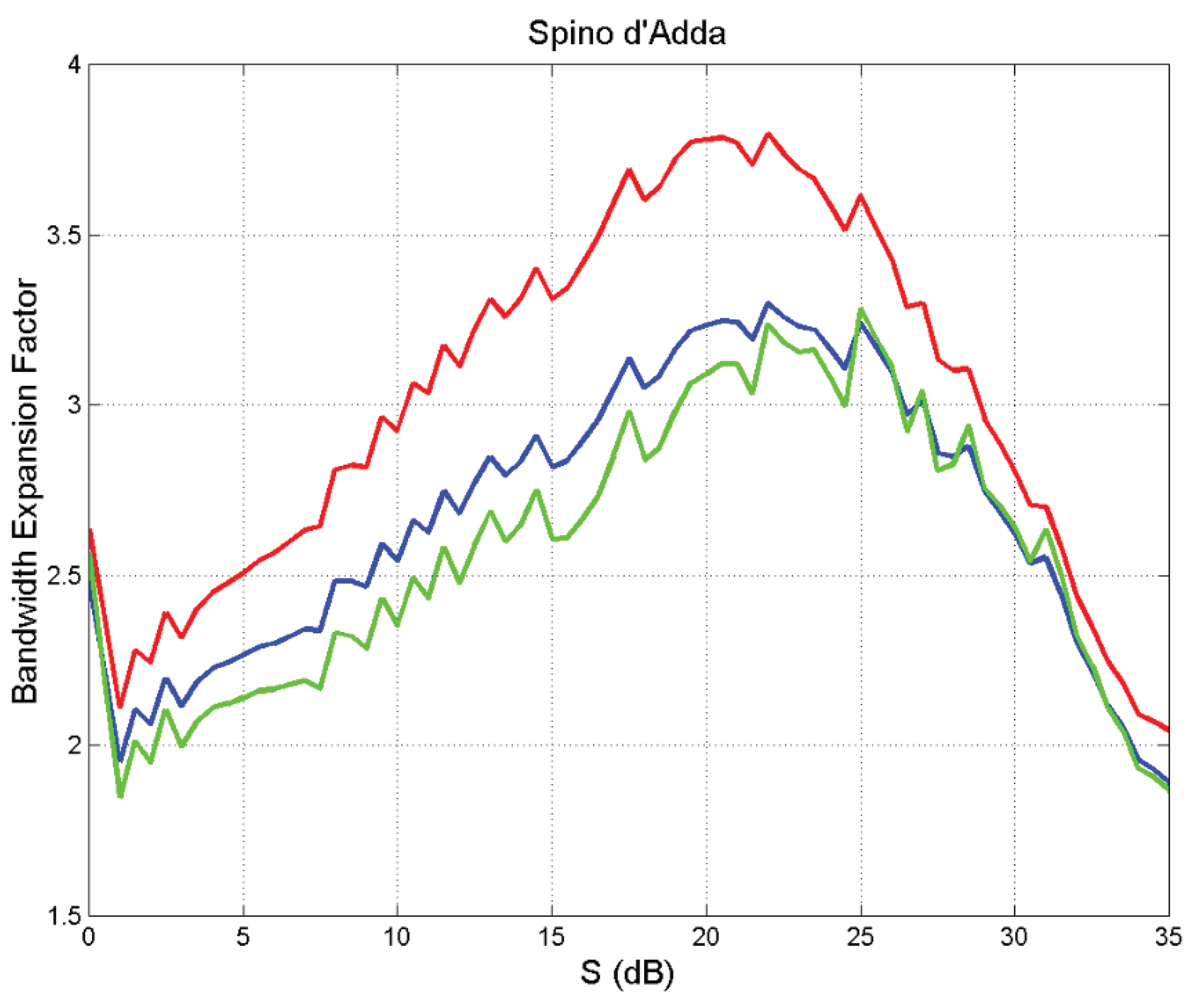

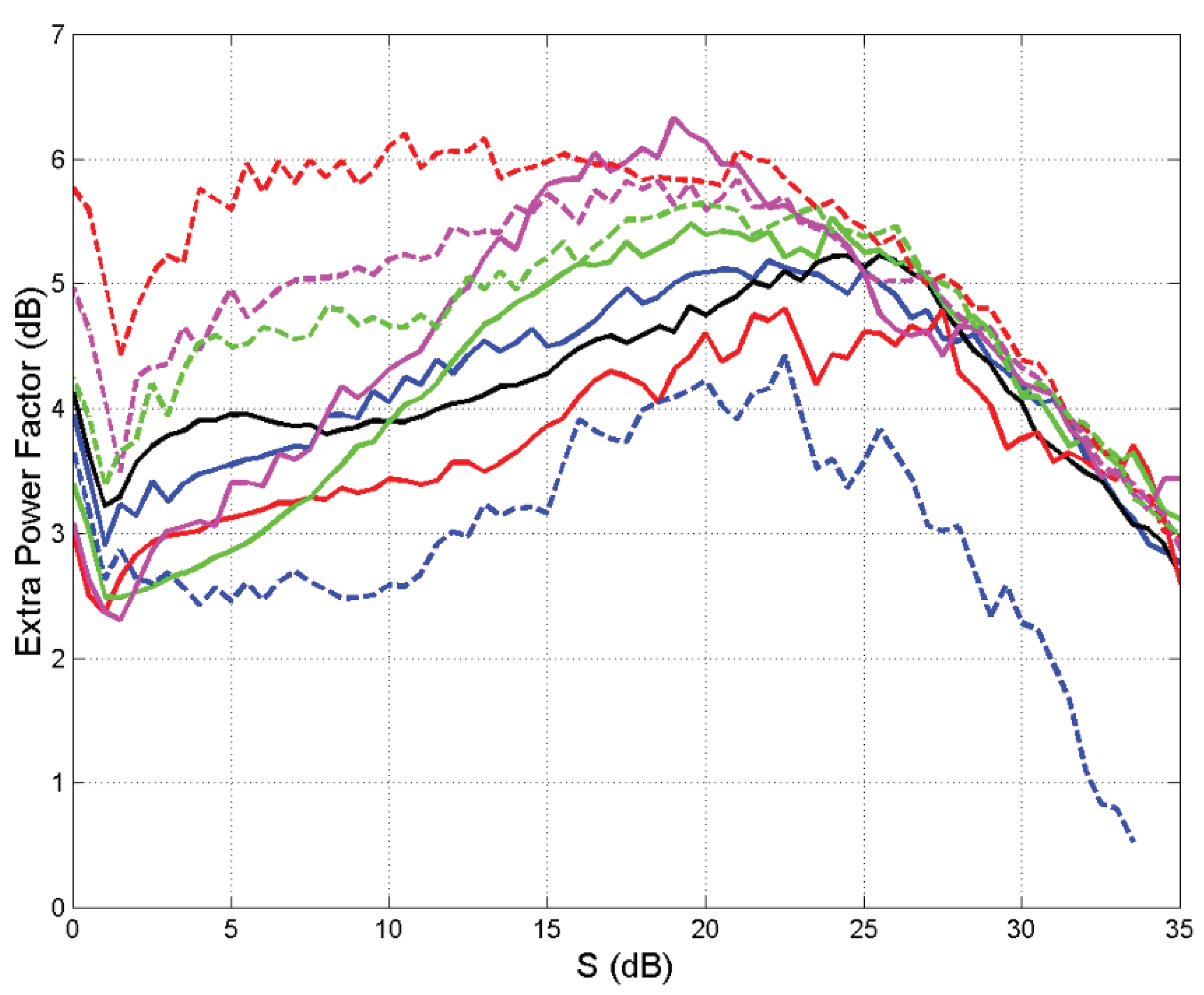

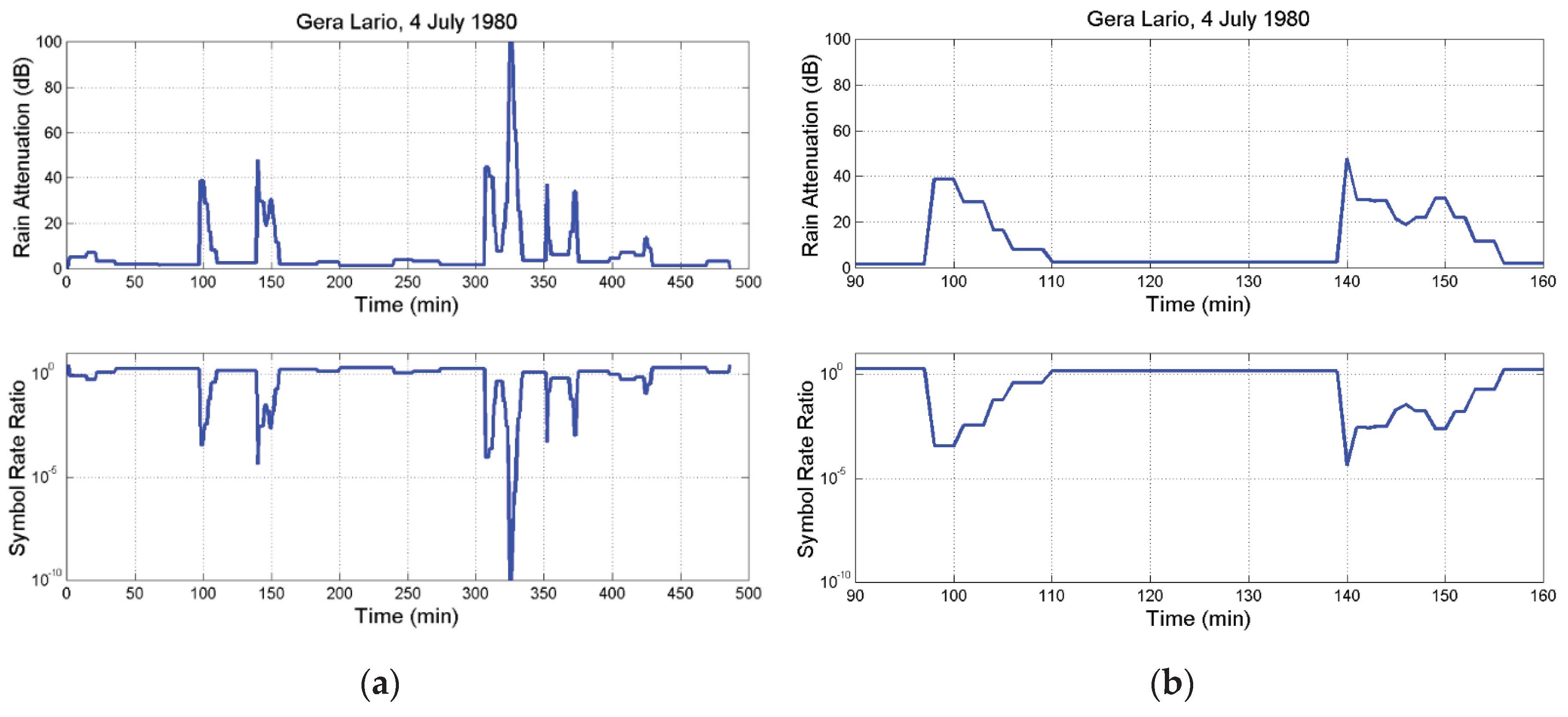

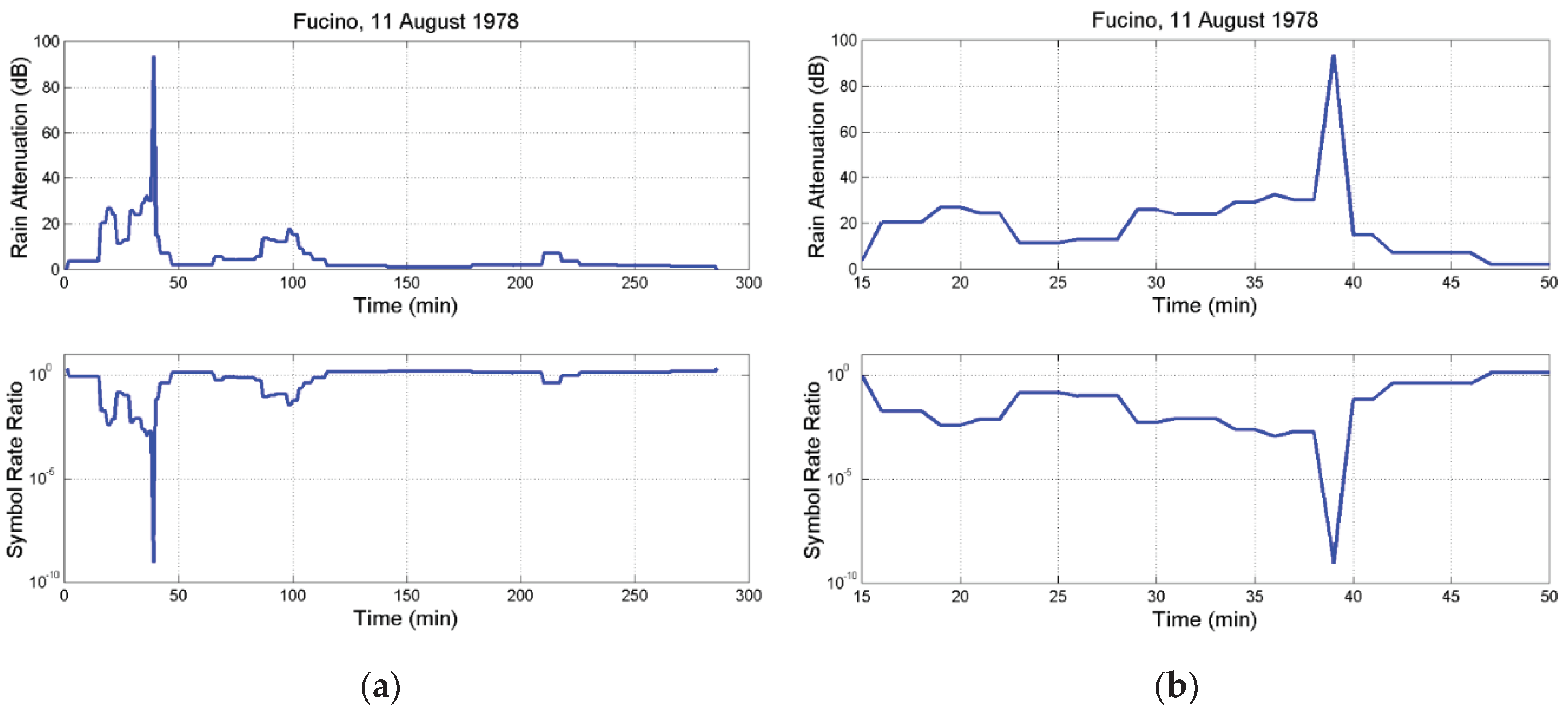

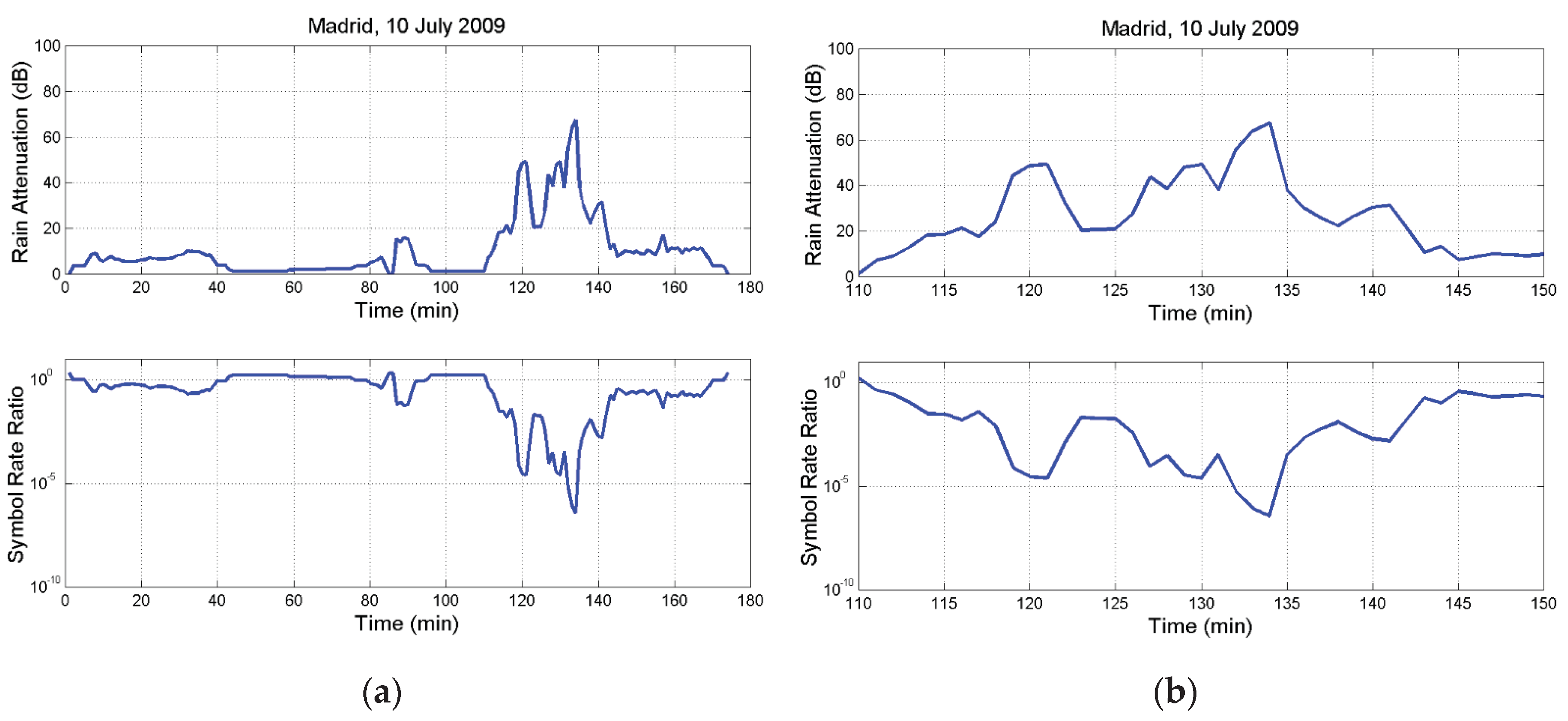

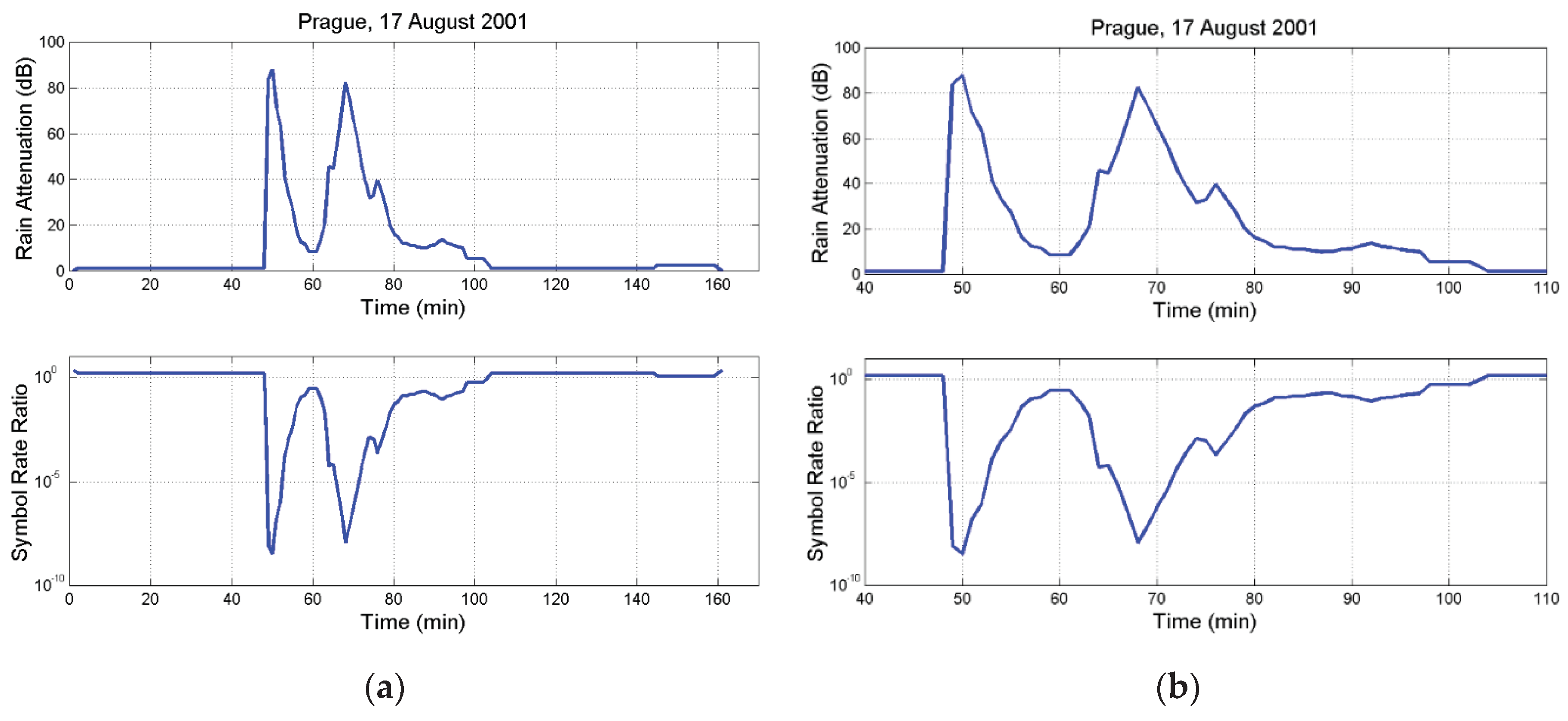

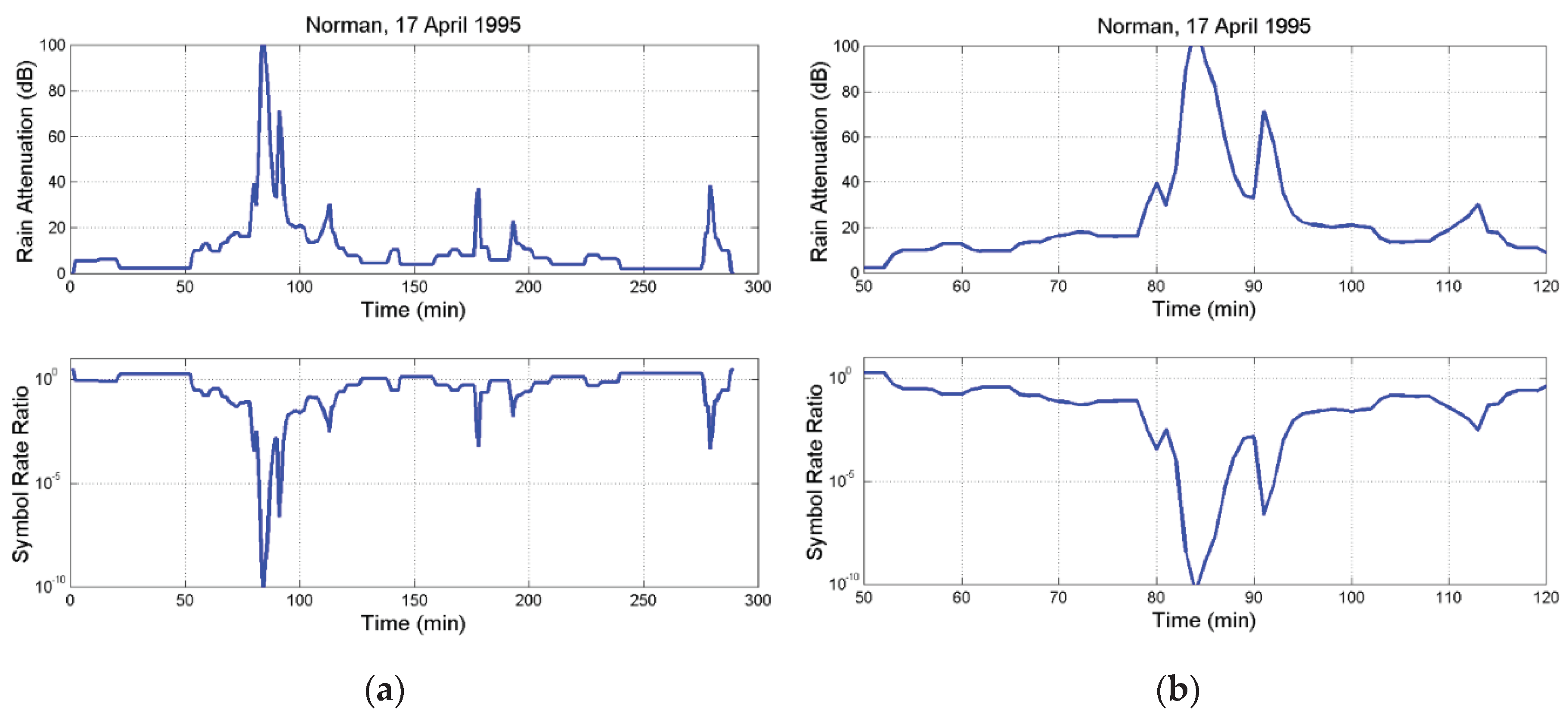

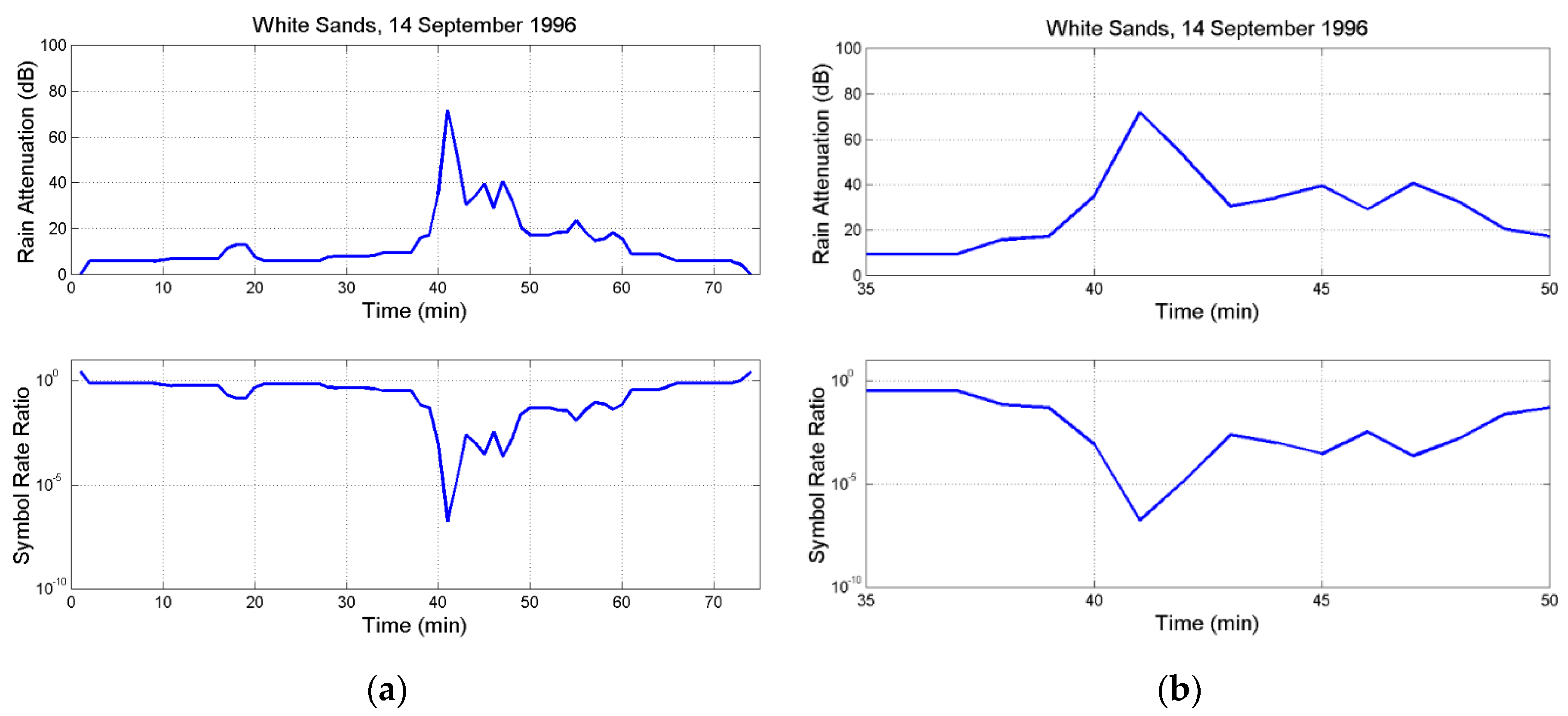

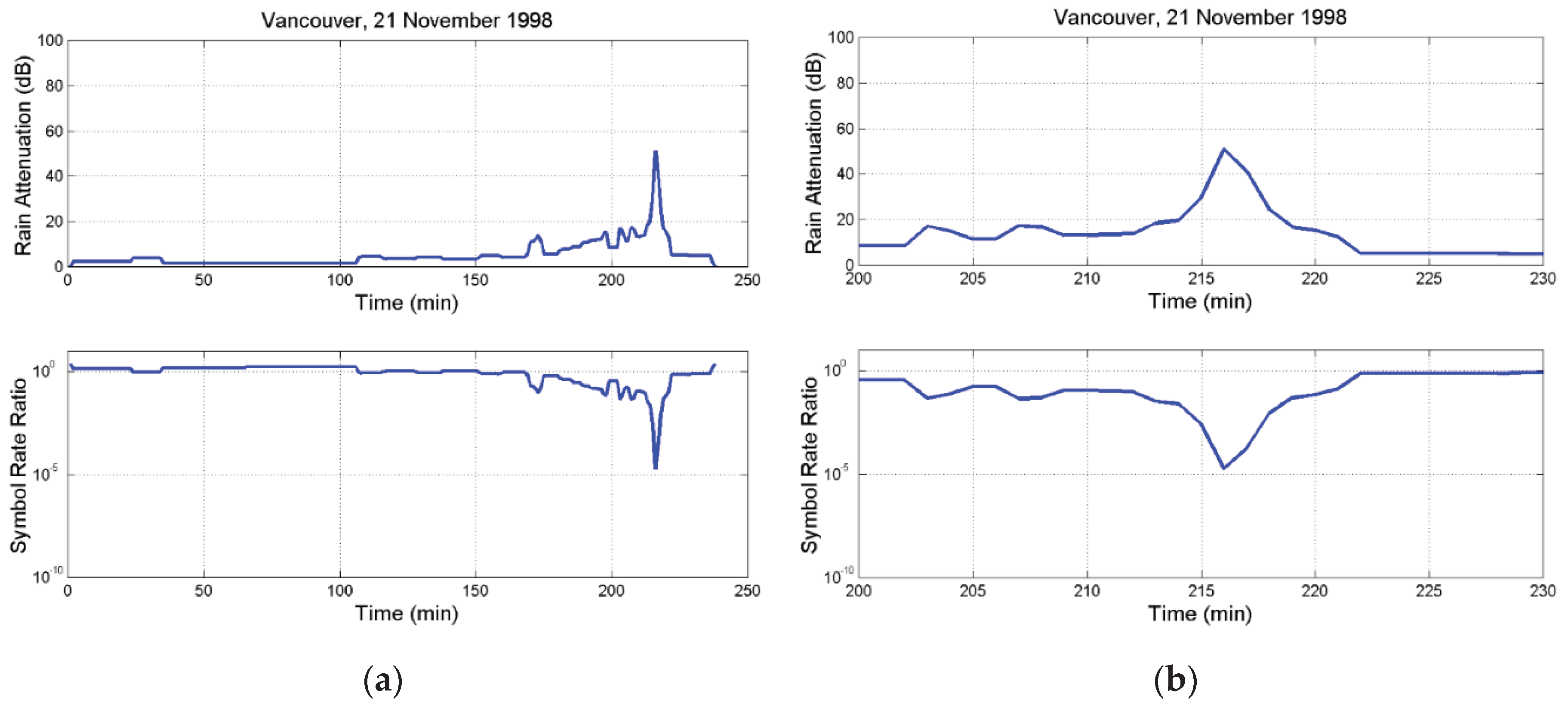

3.2. Examples of Theoretical Application to Time Series

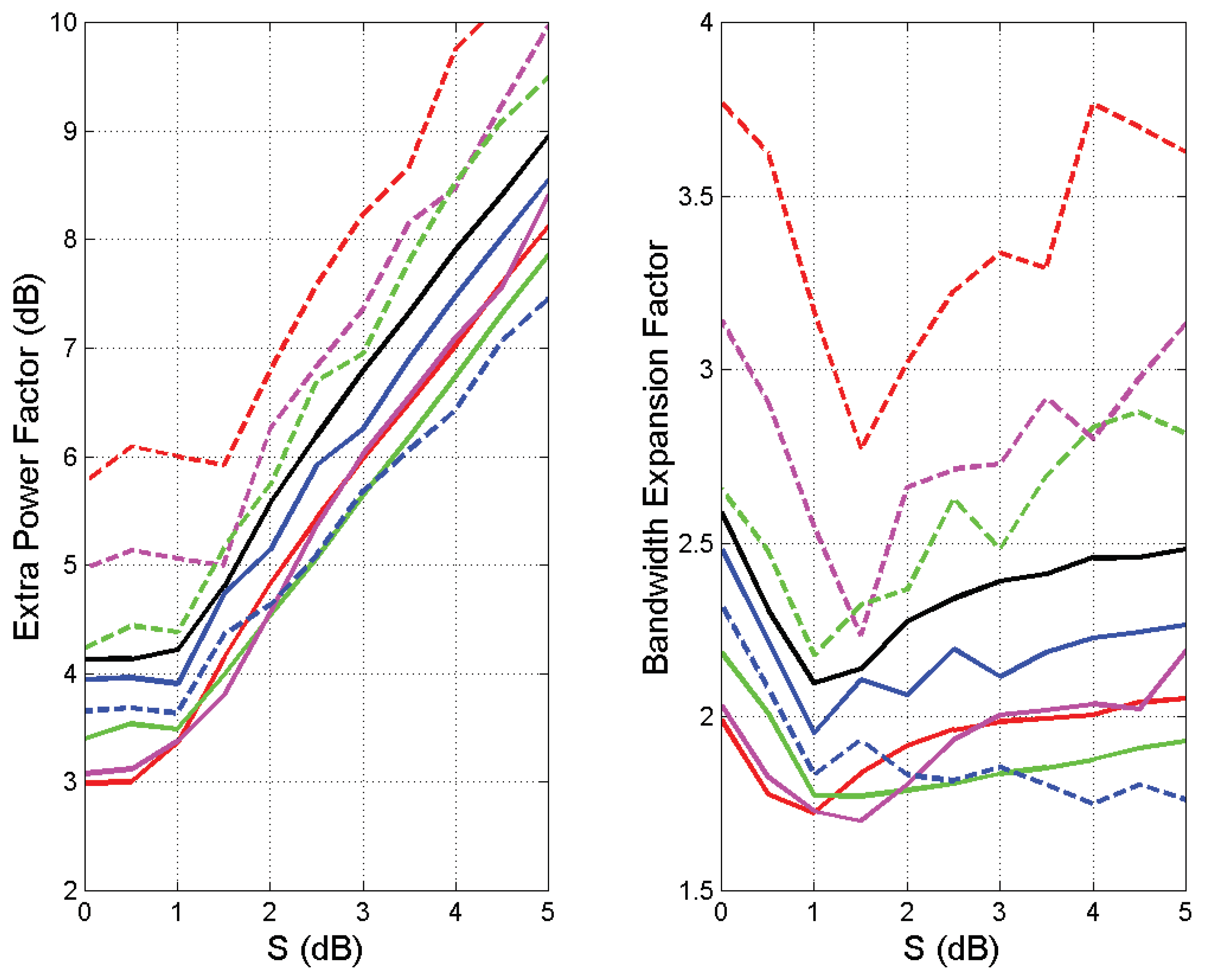

4. Design with Extra Fixed Power Margin

- (a)

- The efficiency is maximum at lower thresholds, but not at dB.

- (b)

- The extra power margin is minimum in according with efficiency.

- (c)

- The bandwidth expansion factor is minimum in according with efficiency.

- (d)

- The efficiency is minimum (worst case) at about dB.

- (e)

- For dB another maximum efficiency occurs, but this range is not attractive because of the very large power margin.

| Site | Total power margin | Bandwidth expansion factor |

|---|---|---|

| Spino d’Adda (Italy) | ||

| Gera Lario (Italy) | ||

| Fucino (Italy) | ||

| Madrid (Spain) | ||

| Prague (Czech Republic) | ||

| Tampa (Florida) | ||

| Norman (Oklahoma) | ||

| White Sands (New Mexico) | ||

| Vancouver (British Columbia) |

5. Conclusion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Matricciani, E.; Riva, C. The search for the most reliable long–term rain attenuation cdf of a slant path and the impact on prediction models. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2005, 53, 3075–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E.; Riva, C.; Luini, L. Tropospheric Attenuation in GeoSurf Satellite Constellations. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E.; Riva, C. Outage Probability versus Carrier Frequency in GeoSurf Satellite Constellations with Radio–Links Faded by Rain. Telecom 2022, 3, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E.; Riva, C. Transfer–functions and Linear Distortions in Ultra–Wideband Channels Faded by Rain in GeoSurf Satellite Constellations. Future Internet 2023, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E.; Magarini, M.; Riva, C. Feasibility of Ultra–Wideband Channels at Millimeter Wavelengths Faded by Rain in GeoSurf Satellite Constellations. Telecom 2023, 4, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badron, K.; Ismail, A.F.; Din, J.; Tharek, A.R. Rain induced attenuation studies for V–band satellite communication in tropical region. J. Atmos. Sol.–Terr. Phys. 2011, 73, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, X.; Gabard, B.; Casadebaig, L.; Castanet, L. Four Years of Total Attenuation Statistics of Earth–Space Propagation Experiments at Ka–Band in Toulouse. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2015, 63, 2203–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelmendi, A.; Hrovat, A.; Mohorčič, M.; Švigelj, A. Alphasat Propagation Measurements at Ka and Q–Bands in Ljubljana: Three Years’ Statistical Analysis. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2021, 20, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recommendation ITU‒R P.618‒14. Propagation Data and Prediction Methods Required for the Design of Earth–Space Telecommunication Systems; ITU: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Matricciani, E. A method to achieve clear-sky data-volume download in satellite links affected by tropospheric attenuation. Int. J. Satell. Commun. Netw. 2016, 34, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea, J. Goldsmith, Soon-Ghee Chua, Adaptive Coded Modulation for Fading Channels. IEEE Transactions on Communications 1998, 46, 595–602. [Google Scholar]

- Alberty, E.; Defever, S.; Moreau, C.; Gaudenzi, R.D.; Ginesi, A.; Rinaldo, R.; Gallinaro, g.; Vernucci, A. Adaptive Coding and Modulation for the DVB-S2 Standard Interactive Applications: Capacity Assessment and Key System Issues; IEEE Wireless Communications, August 2007, 61–69.

- Bischl, H.; Brandt, H.; de Cola, T.; De Gaudenzi, R.; Eberlein, E.; Girault, N.; Alberty, E.; Lipp, S.; Rinaldo, R.; Rislow, B.; Skard, J.A.; Tousch, J.; Ulbricht, G. Adaptive Coding and Modulation for satellite broadband networks: From theory to practice. International Int. J. Satell. Commun. Netw. 2010, 28, 59–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yu, G.; Yu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Weather-Conscious Adaptive Modulation and Coding Scheme for Satellite-Related Ubiquitous Networking and Computing. Electronics 2022, 11, 1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Lu, F.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Li, J. A Transmission Efficiency Evaluation Method of Adaptive Coding Modulation for Ka-Band Data-Transmission of LEO EO Satellites. Sensors 2022, 22, 5423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mhangara, P.; Mapurisa, W. Multi-mission earth observation data processing system. Sensors 2019, 19, 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.Q.; Li, L.; Jin, F.; Zhang, J.P. Research on satellite-borne high-speed adaptive transmission technique. Space Electron. Technol. 2014, 11, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.P. Adaptive coding and modulation for remote sensing satellite. Space Electron. Technol. 2016, 13, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.G.; Wang, D.B.; Hu, Y.; Lu, F. Analysis on application efficiency of adaptive coding and modulation for LEO remote sensing satellite at Ka-band. Spacecr. Eng. 2021, 30, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Matricciani, E. Geocentric Spherical Surfaces Emulating the Geostationary Orbit at Any Latitude with Zenith Links. Future Internet 2020, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Physical–mathematical model of the dynamics of rain attenuation based on rain rate time series and a two–layer vertical structure of precipitation. Radio Sci. 1996, 31, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Prediction of fade duration due to rain in satellite communication systems. Radio Sci. 1997, 22, 935–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Verma, P.; Paudel, B.; Shukla, A.; Das, S. Validation of Synthetic Storm Technique for Rain Attenuation Prediction Over High–Rainfall Tropical Region. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2021, 19, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, S.L.; Riva, C.; D’Amico, M.; Lam, H.Y.; Yunus, M.M.; Din, J. Performance of synthetic storm technique in estimating fade dynamics in equatorial Malaysia. Int. J. Satell. Commun. Netw. 2018, 36, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Matricciani, Probability distributions of rain attenuation obtainable with linear combining techniques in space-to-Earth links using time diversity. International Journal of Satellite Communications and Networking 2017, 2017, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Physical-mathematical model of dynamics of rain attenuation with application to power spectrum. Electronics Letters. 1994, 30, 522–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, D.D.; Pérez-Fontán, F.; Pastoriza-Santos, V.; Machado, F. Application of synthetic storm technique for rain attenuation prediction at Ka and Q band for a temperate Location, Vigo, Spain. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 66, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E.; Riva, C. Duration of Rainfall Fades in GeoSurf Satellite Constellations. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, F.S. Modeling antenna noise temperature due to rain clouds at microwave and millimeter–wave frequencies. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2006, 54, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turin, G.L. Introduction to spread spectrum antimultipath techniques and their application to urban digital radio. Proc. IEEE 1980, 68, 328–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickholtz, R.; Schilling, D.; Milstein, L. Theory of spread–spectrum communications—A tutorial. IEEE Trans. Commun. 1982, 30, 855–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viterbi, A.J. CDMA Principles of Spread Spectrum Communications; Addinson–Wesly: Reading, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dinan, E.H.; Jabbari, B. Spreading codes for direct sequence CDMA and wideband CDMA celluar networks. IEEE Commun. Mag. 1998, 36, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeravalli, V.V.; Mantravadi, A. The coding–spreading trade–off in CDMA systems. IEEE Trans. Sel. Areas Commun. 2002, 20, 396–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Matricciani, Rate of change of signal attenuation from SIRIO at 11.6 GHz. Electronics Letters. 1981, 17, 139–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia–Rubia, J.M.; Riera, J.M.; Garcia–del–Pino, P.; Pimienta–del–Valle, D.; Siles, G.A. Fade and Interfade Duration Characteristics in a Slant–Path Ka–Band Link. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2017, 65, 7198–7206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Chakraborty, M.; Das, S. Second order experimental statistics of rain attenuation at Ka band in a tropical location. Adv. Space Res. 2012, 67, 4043–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papafragkakis, A.Z.; Kourogiorgas, C.I.; Panagopoulos, A.D.; Ventouras, S. Second Order Excess Attenuation Statistics in Athens, Greece at 19.701 GHz using ALPHASAT. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium on Communication Systems, Networks and Digital Signal Processing (CSNDSP), Porto, Portugal, 20–22 July 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Chakraborty, M.; Chakraborty, S.; Shukla, A.; Acharya, R. Experimental studies of Ka Band Rain Fade Slope at a Tropical Location of India. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 66, 1551–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, S.L.; Riva, C.; Din, J.; D’Amico, M.; Lam, H.Y. Fade slope analysis for Ku-band earth-space communication links in Malaysia. IET Microw. Antennas Propag. 2019, 13, 2330–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, M.A.; Diba, F.D.; Choi, D.-Y. A Survey of Rain Fade Models for Earth–Space Telecommunication Links—Taxonomy, Methods, and Comparative Study. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).