Submitted:

22 July 2025

Posted:

23 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

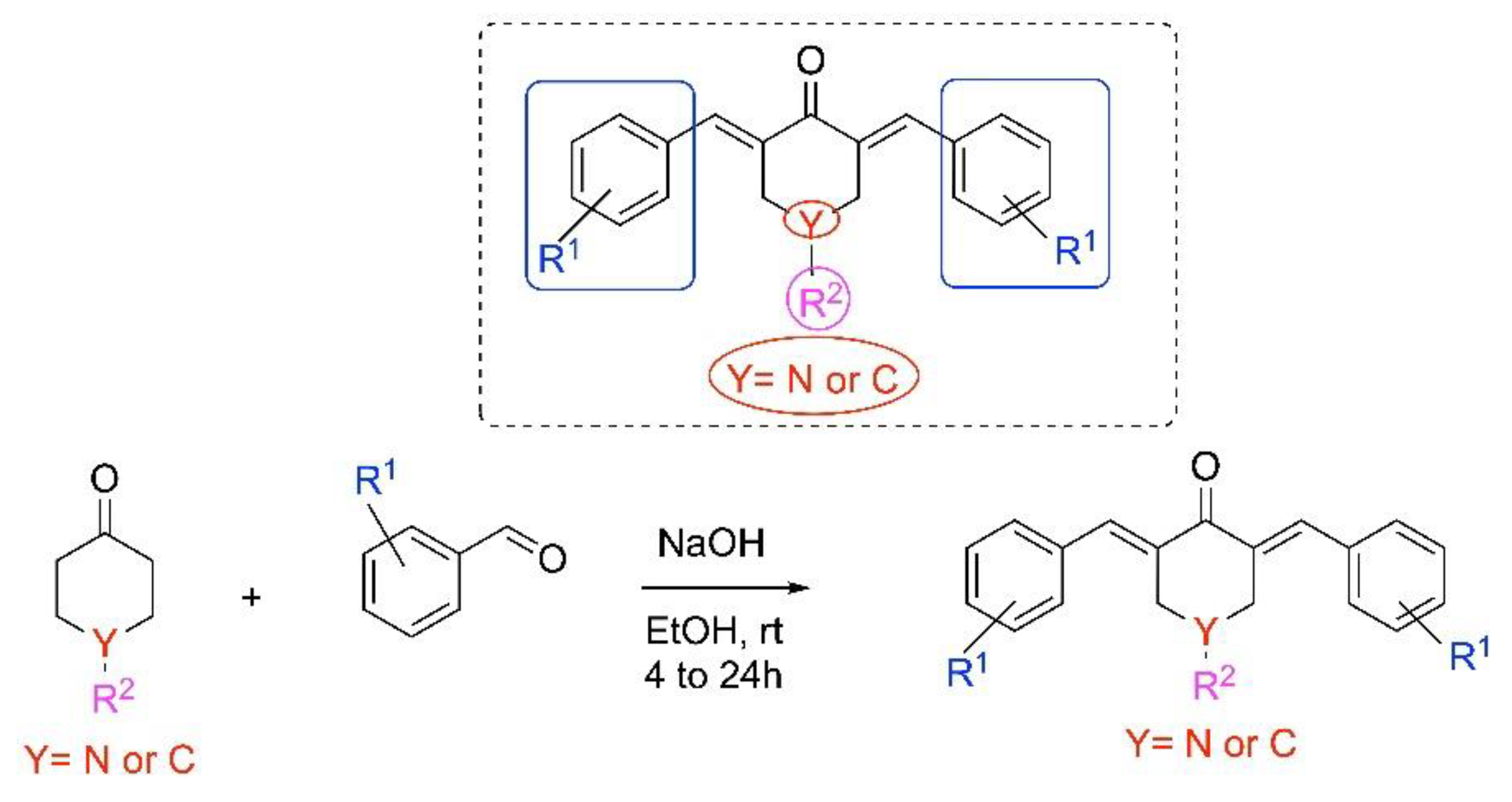

2.1. Synthesis of Piperidones

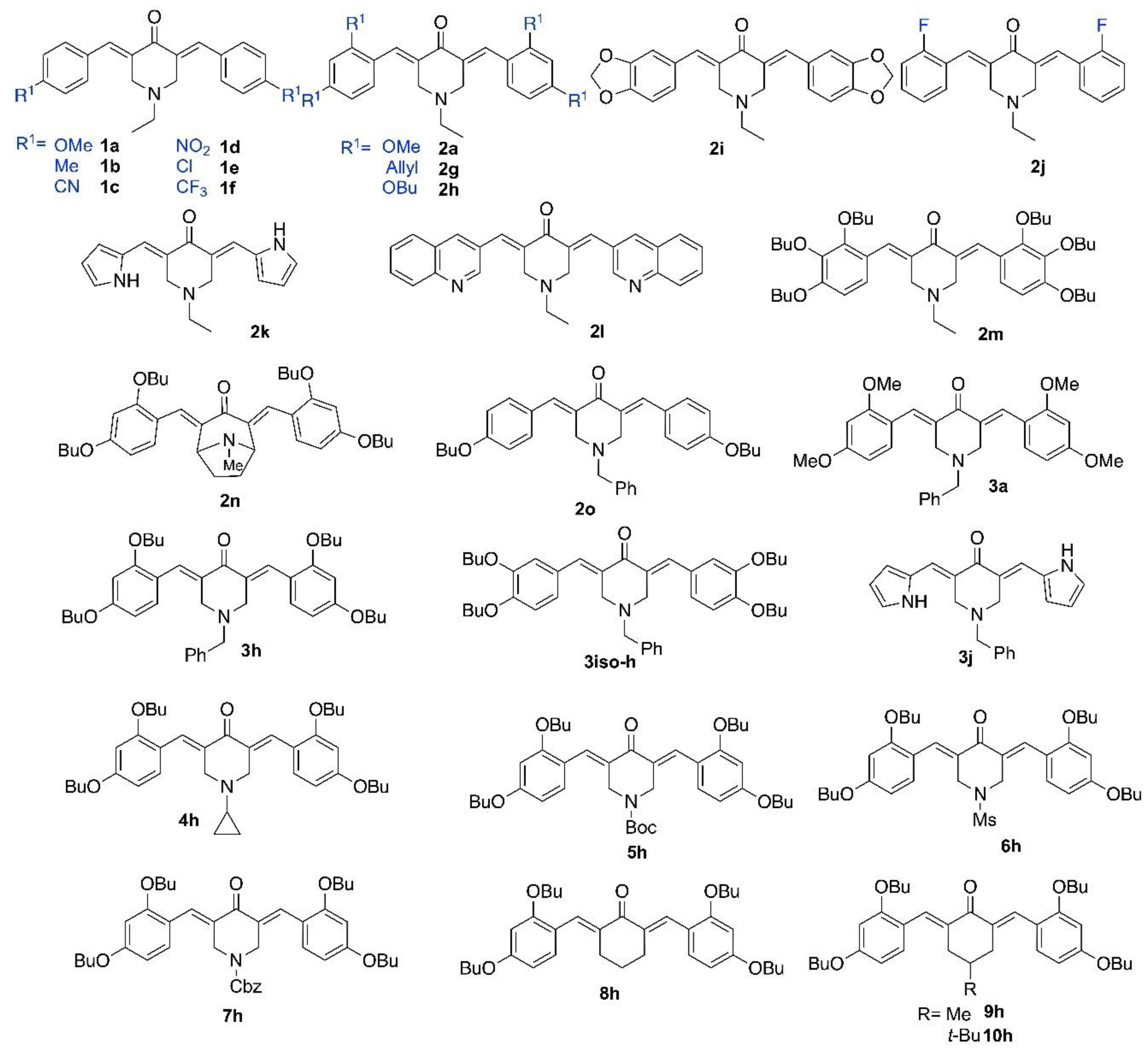

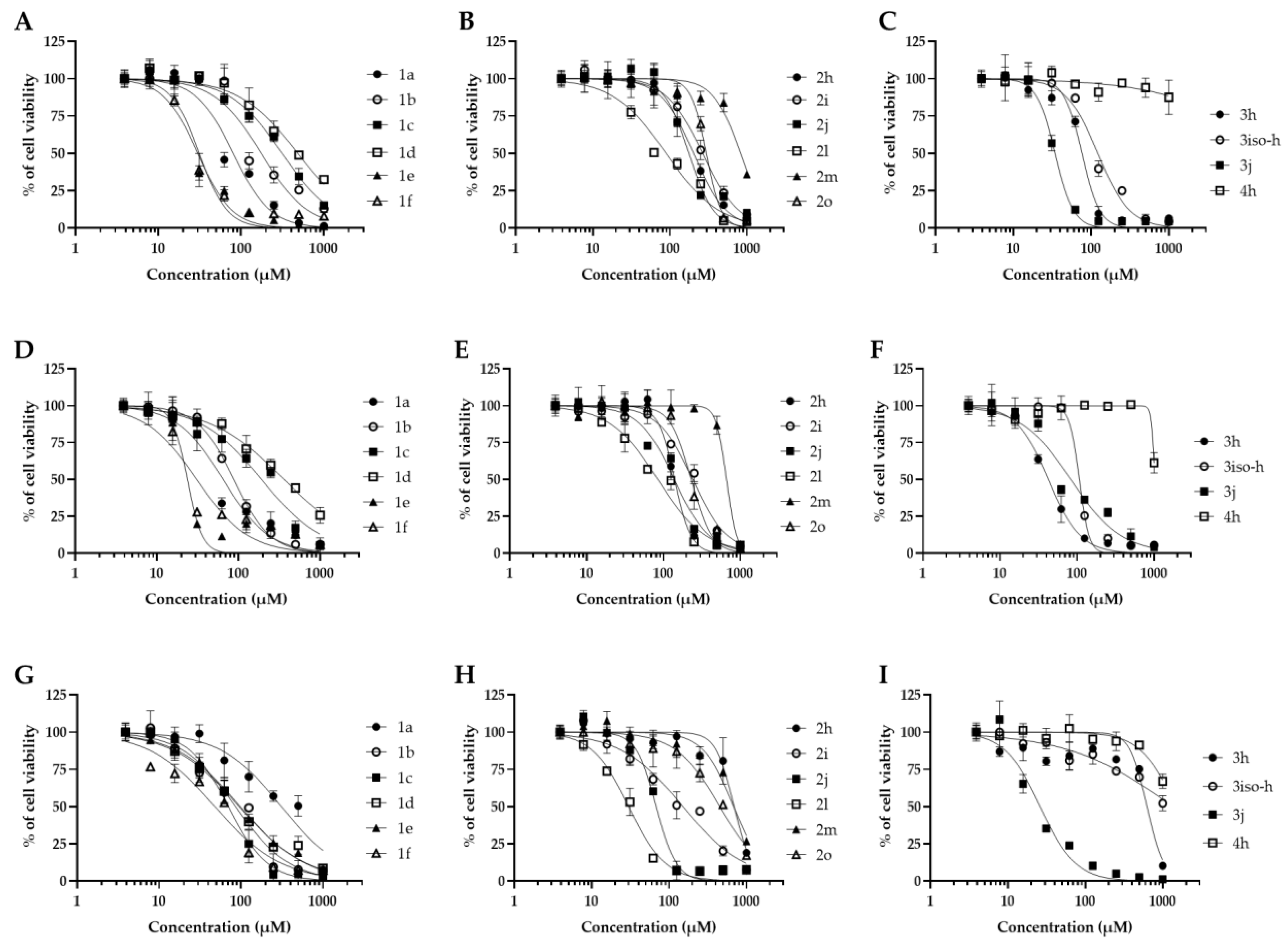

2.1. Antifungal Activities and Toxicity of Synthesized Piperidones

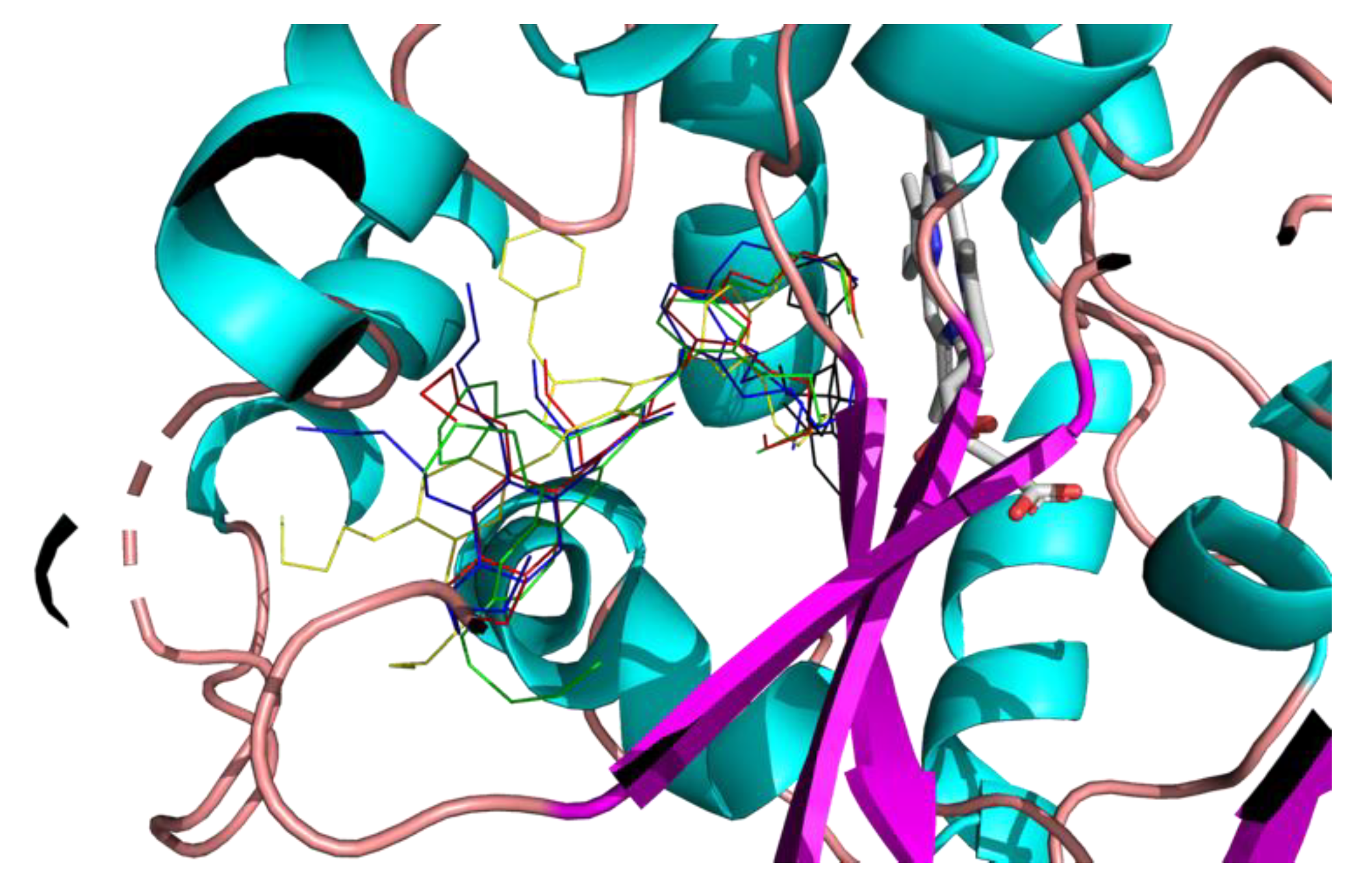

2.3. Molecular Modeling

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemistry

4.2. Antimicrobial Activity

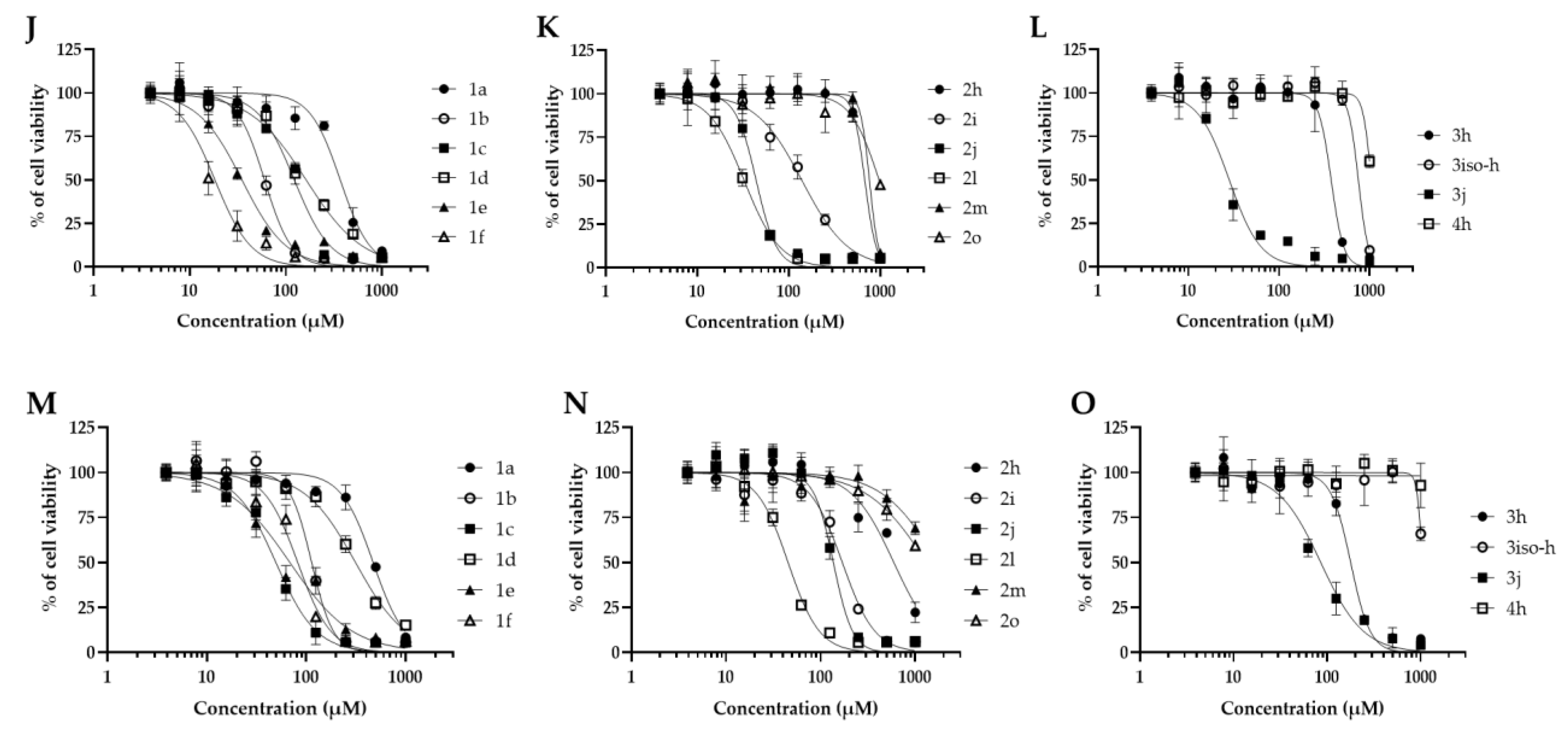

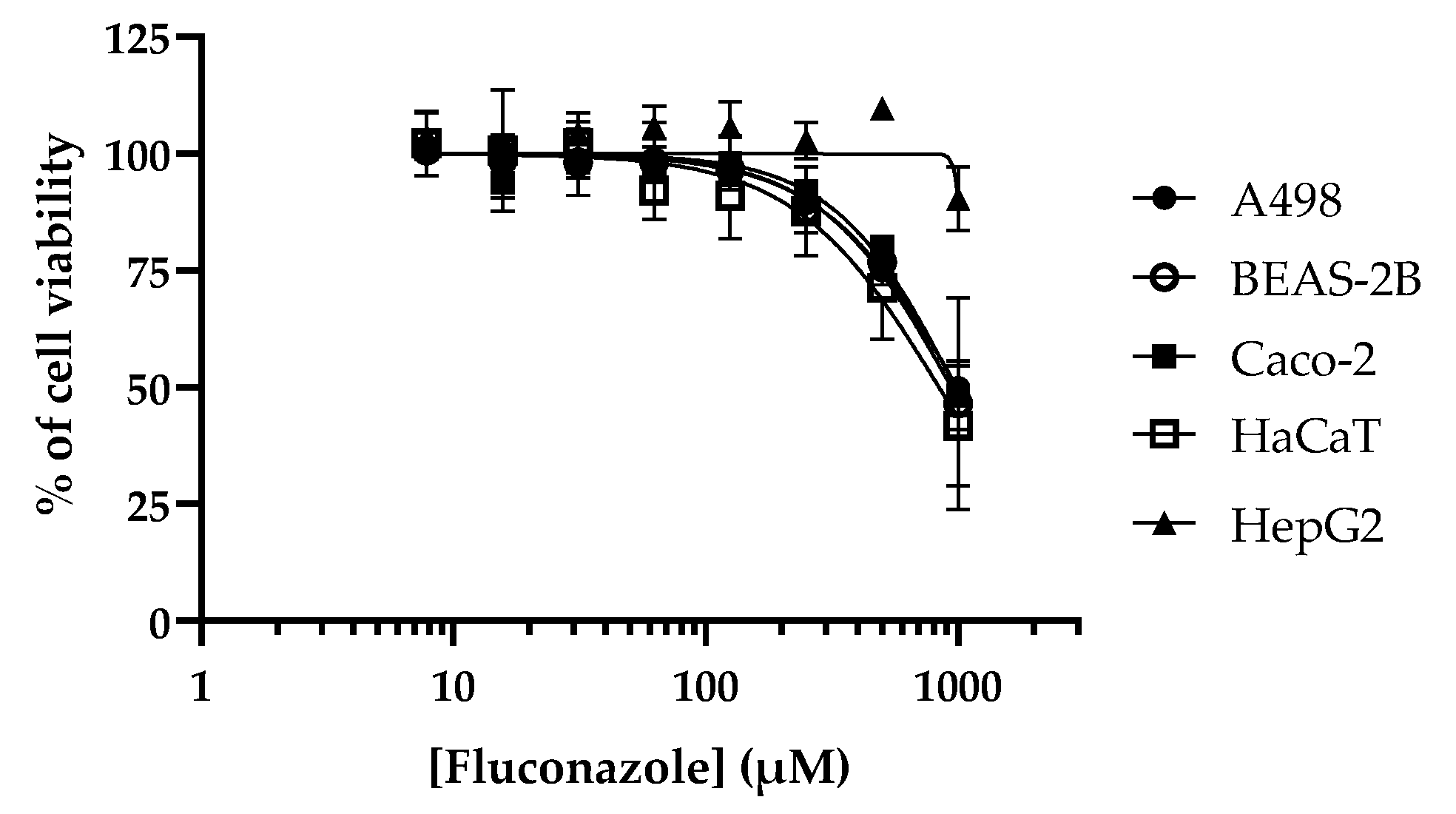

4.3. Cytotoxicity Studies

4.4. Molecular Docking

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perfect, J.R. Efficiently Killing a Sugar-Coated Yeast. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1354–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.N.; Chau, T.T.H.; Wolbers, M.; Mai, P.P.; Dung, N.T.; Mai, N.H.; Phu, N.H.; Nghia, H.D.; Phong, N.D.; Thai, C.Q.; et al. Combination Antifungal Therapy for Cryptococcal Meningitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1291–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartland, K.; Pu, J.; Palmer, M.; Dandapani, S.; Moquist, P.N.; Munoz, B.; DiDone, L.; Schreiber, S.L.; Krysan, D.J. High-Throughput Screen in Cryptococcus Neoformans Identifies a Novel Molecular Scaffold That Inhibits Cell Wall Integrity Pathway Signaling. ACS Infect. Dis. 2016, 2, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, S.R.; Schnicker, N.J.; Murante, T.; Kettimuthu, K.; Williams, N.S.; Gakhar, L.; Krysan, D.J. Benzothiourea Derivatives Target the Secretory Pathway of the Human Fungal Pathogen Cryptococcus Neoformans. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, H.N.; Das, U.; Das, S.; Bandy, B.; De Clercq, E.; Balzarini, J.; Kawase, M.; Sakagami, H.; Quail, J.W.; Stables, J.P.; et al. The Cytotoxic Properties and Preferential Toxicity to Tumour Cells Displayed by Some 2,4-Bis(Benzylidene)-8-Methyl-8-Azabicyclo[3.2.1] Octan-3-Ones and 3,5-Bis(Benzylidene)-1-Methyl-4-Piperidones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Tyagi, A.K.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin, a Component of Golden Spice: From Bedside to Bench and Back. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazzaro, M.; Linder, S. Dienone Compounds: Targets and Pharmacological Responses. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 15075–15093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noureddin, S.A.; El-Shishtawy, R.M.; Al-Footy, K.O. Curcumin Analogues and Their Hybrid Molecules as Multifunctional Drugs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 182, 111631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.T.; Sehgal, P.; Tung, T.T.; Møller, J.V.; Nielsen, J.; Palmgren, M.; Christensen, S.B.; Fuglsang, A.T. Demethoxycurcumin Is A Potent Inhibitor of P-Type ATPases from Diverse Kingdoms of Life. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0163260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, S.; Arumugam, N.; Almansour, A.I.; Suresh Kumar, R.; Thangamani, S. Dispiropyrrolidine Tethered Piperidone Heterocyclic Hybrids with Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Activity against Candida Albicans and Cryptococcus Neoformans. Bioorganic Chem. 2020, 100, 103865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagargoje, A.A.; Akolkar, S.V.; Subhedar, D.D.; Shaikh, M.H.; Sangshetti, J.N.; Khedkar, V.M.; Shingate, B.B. Propargylated Monocarbonyl Curcumin Analogues: Synthesis, Bioevaluation and Molecular Docking Study. Med. Chem. Res. 2020, 29, 1902–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synthesis and Evaluation of Novel Antifungal Agents Targeted to the Plasma Membrane H[+]-ATPase. Br. J. Pharm. 2018, 2. [CrossRef]

- Howard, K.C.; Dennis, E.K.; Watt, D.S.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. A Comprehensive Overview of the Medicinal Chemistry of Antifungal Drugs: Perspectives and Promise. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 2426–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pigot, C.; Noirbent, G.; Bui, T.-T.; Péralta, S.; Gigmes, D.; Nechab, M.; Dumur, F. Push-Pull Chromophores Based on the Naphthalene Scaffold: Potential Candidates for Optoelectronic Applications. Materials 2019, 12, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagargoje, A.A.; Akolkar, S.V.; Siddiqui, M.M.; Subhedar, D.D.; Sangshetti, J.N.; Khedkar, V.M.; Shingate, B.B. Quinoline Based Monocarbonyl Curcumin Analogs as Potential Antifungal and Antioxidant Agents: Synthesis, Bioevaluation and Molecular Docking Study. Chem. Biodivers. 2020, 17, e1900624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, R.; Biava, M.; Porretta, G.; Landolfi, C.; Simonetti, N.; Villa, A.; Conte, E.; Porta-Puglia, A. Research on Antibacterial and Antifungal Agents. XI. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity of N-Heteroaryl Benzylamines and Their Schiff Bases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 30, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoudi Halat, D.; Younes, S.; Mourad, N.; Rahal, M. Allylamines, Benzylamines, and Fungal Cell Permeability: A Review of Mechanistic Effects and Usefulness against Fungal Pathogens. Membranes 2022, 12, 1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfect, J.R.; Dismukes, W.E.; Dromer, F.; Goldman, D.L.; Graybill, J.R.; Hamill, R.J.; Harrison, T.S.; Larsen, R.A.; Lortholary, O.; Nguyen, M.-H.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Cryptococcal Disease: 2010 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 291–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyse, A.; Burry, J.; Cohn, J.; Ford, N.; Chiller, T.; Ribeiro, I.; Koulla-Shiro, S.; Mghamba, J.; Ramadhani, A.; Nyirenda, R.; et al. Leave No One behind: Response to New Evidence and Guidelines for the Management of Cryptococcal Meningitis in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, e143–e147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.W. Global Incidence and Mortality of Severe Fungal Disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e428–e438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, B.; Lacy, A.J.; Koyfman, A.; Liang, S.Y. Candida Auris: A Focused Review for Emergency Clinicians. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 84, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, M.; Kinjo, Y.; Koshikawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Basic Research on Candida Species: Disease Mechanism, Virulence, and Relationship with Environmental Factors. Med. Mycol. J. 2024, 65, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawoud, A.M.; Saied, S.A.; Torayah, M.M.; Ramadan, A.E.; Elaskary, S.A. Antifungal Susceptibility and Virulence Determinants Profile of Candida Species Isolated from Patients with Candidemia. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beardsley, J.; Kim, H.Y.; Dao, A.; Kidd, S.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Sorrell, T.C.; Tacconelli, E.; Chakrabarti, A.; Harrison, T.S.; Bongomin, F.; et al. Candida Glabrata ( Nakaseomyces Glabrata ): A Systematic Review of Clinical and Microbiological Data from 2011 to 2021 to Inform the World Health Organization Fungal Priority Pathogens List. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keighley, C.; Kim, H.Y.; Kidd, S.; Chen, S.C.-A.; Alastruey, A.; Dao, A.; Bongomin, F.; Chiller, T.; Wahyuningsih, R.; Forastiero, A.; et al. Candida Tropicalis —A Systematic Review to Inform the World Health Organization of a Fungal Priority Pathogens List. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, S.; Cramer, R.A. Regulation of Sterol Biosynthesis in the Human Fungal Pathogen Aspergillus Fumigatus: Opportunities for Therapeutic Development. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Giacoletto, N.; Schmitt, M.; Nechab, M.; Graff, B.; Morlet-Savary, F.; Xiao, P.; Dumur, F.; Lalevée, J. Effect of Decarboxylation on the Photoinitiation Behavior of Nitrocarbazole-Based Oxime Esters. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 2475–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deligeorgakis, C.; Magro, C.; Skendi, A.; Gebrehiwot, H.H.; Valdramidis, V.; Papageorgiou, M. Fungal and Toxin Contaminants in Cereal Grains and Flours: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods 2023, 12, 4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maebashi, K.; Niimi, M.; Kudoh, M.; Fischer, F.J.; Makimura, K.; Niimi, K.; Piper, R.J.; Uchida, K.; Arisawa, M.; Cannon, R.D.; et al. Mechanisms of Fluconazole Resistance in Candida Albicans Isolates from Japanese AIDS Patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 47, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janowski, M.; Demchuk, O.M.; Wujec, M. Fluconazole Analogs and Derivatives: An Overview of Synthesis, Chemical Transformations, and Biological Activity. Molecules 2024, 29, 2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, N. Antifungal Resistance: Current Trends and Future Strategies to Combat. Infect. Drug Resist. 2017, Volume 10, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. ; Perrier, J.; Maresca, M. Comparative Structure–Activity Analysis of the Antimicrobial Activity, Cytotoxicity, and Mechanism of Action of the Fungal Cyclohexadepsipeptides Enniatins and Beauvericin. Toxins 2019, 11, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkhaled, B.T.; Hadiouch, S.; Olleik, H.; Perrier, J.; Ysacco, C.; Guillaneuf, Y.; Gigmes, D.; Maresca, M.; Lefay, C. Elaboration of Antimicrobial Polymeric Materials by Dispersion of Well-Defined Amphiphilic Methacrylic SG1-Based Copolymers. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 3127–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olleik, H.; Yacoub, T.; Hoffer, L.; Gnansounou, S.M.; Benhaiem-Henry, K.; Nicoletti, C.; Mekhalfi, M.; Pique, V.; Perrier, J.; Hijazi, A.; et al. Synthesis and Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activities of 13-Substituted Berberine Derivatives. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | MIC (μM) | CC50 (μM) | SI | ||||

| A498 | BEAS-2B | Caco-2 | HaCaT | HepG2 | Min-Max | ||

| 1a | 125 | 80.4 | 64.9 | 313.7 | 368.6 | 471.9 | 0.5-3.7 |

| 1b | 250 | 175.6 | 87.9 | 86.2 | 60.0 | 113.5 | 0.2-0.7 |

| 1c | 250 | 313.9 | 191.8 | 70.3 | 122.7 | 49.5 | 0.1-1.2 |

| 1d | 250 | 486.2 | 363.5 | 95.4 | 162.9 | 313.6 | 0.3-1.9 |

| 1e | 250 | 31.3 | 23.7 | 98.6 | 34.9 | 68.5 | 0.09-0.4 |

| 1f | 250 | 30.0 | 30.9 | 47.0 | 18.3 | 82.1 | 0.07-0.3 |

| 2a | >250 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 2g | >250 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 2h | 31.2 | 203.7 | 140.2 | 696.6 | 680.3 | 595.6 | 4.5-22.3 |

| 2i | 250 | 266.6 | 241.2 | 152.0 | 140.0 | 169.6 | 0.5-1.0 |

| 2j | 250 | 177.3 | 139.0 | 68.3 | 44.2 | 136.4 | 0.1-0.7 |

| 2k | >250 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | ND |

| 2l | 250 | 89.5 | 84.5 | 30.0 | 32.6 | 45.3 | 0.1-0.3 |

| 2m | 62.5 | 829.4 | 663.7 | 686.9 | 764.3 | >1000 | 10.6->16 |

| 2n | >250 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 2o | 125 | 297.4 | 230.5 | 454.7 | 979.3 | >1000 | 1.8->8 |

| 3a | >250 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 3h | 7.8 | 76.4 | 42.4 | 628.6 | 377.3 | 178.3 | 5.4-80.5 |

| 3iso-h | 62.5 | 122.4 | 106.9 | >1000 | 753.8 | >1000 | 1.7->16 |

| 3j | 62.5 | 34.5 | 82.9 | 26.1 | 28.2 | 85.6 | 0.4-1.3 |

| 4h | 250 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 | >4 |

| 5h | >250 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 6h | >250 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 7h | >250 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 8h | >250 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 9h | >250 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| 10h | >250 | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT |

| Fluconazole | 25 | 993.6 | 942.5 | 977.0 | 841.2 | >1000 | 33.6->40 |

| Compound | C. albicans | C. auris | C. glabrata | C. tropicalis | C. neoformans |

| 2h | 250 | 31.2 | 31.2 | 250 | 31.2 |

| 2m | 125 | 31.2 | 15.6 | 250 | 62.5 |

| 3h | 62.5 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 125 | 7.8 |

| 3iso-h | 250 | 31.2 | 62.5 | 125 | 62.5 |

| Fluconazole | 6.25 | 500 | 250 | 1000 | 25 |

| Compound | A. flavus | A.fumigatus | C. graminicola | F.graminearum | M.oryzae | M. bolleyi | P.verrucosum | T. rubrum |

| 2h | >250 | 125 | >250 | >250 | 15.6 | 62.5 | 125 | 62.5 |

| 2m | >250 | 250 | >250 | >250 | 62.5 | >250 | >250 | 31.2 |

| 3h | 31.2 | 31.2 | 250 | 125 | 7.8 | 31.2 | 62.5 | 7.8 |

| 3iso-h | >250 | 125 | 125 | >250 | 15.6 | 62.5 | 125 | 125 |

| Fluconazole | >1000 | >1000 | 50 | >1000 | 12.5 | >1000 | >1000 | >1000 |

| Compound | Binding energy kcal/mol |

Hydrophobic interactions with amino acids | Aromatic interactions |

| Fluconazole | -8.1 | Phe110, Tyr116, Leu127, Ala287, Ala291, Leu356 | T-Shaped (Tyr103), Hem500 |

| 2h | -7.8 | Tyr103, Met106, Tyr116, Leu219, Phe290, Ala291, Leu356, Met360, Met460 | Hem500 T-Shaped (Tyr103), |

| 3h | -8.2 | Val102, Tyr103, Ile105, Pro210, Phe290, Ala291, Leu356, Met360, Met460 | Hem500 T-Shaped (Tyr103), |

| 2m | -7.2 | Ile72, Tyr103, Phe110, Pro210, Leu219, Phe290, Thr295, Leu356, Met360, Met460, Val461 | Hem500 |

| 3iso-h | -8.8 | Ile105, Met106, Leu208, Pro210, Leu219, Phe290, Ala291, Leu356, Thr459, Val461 | Hem500 T-Shaped (His294, Phe290), |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).