1. Introduction

Teaching is a complex profession that demands simultaneous cognitive and emotional efforts, requiring a regular managing of professionals’ emotions as a key element in reaching educational objectives and fostering positive student outcomes (Afridi et al., 2024).

Considering this complexity, several studies highlighted the impact of burnout on the teaching profession. For example, a recent scoping review (Agyapong et al., 2022) reported prevalence rates ranging from as low as 2.81% (Shukla & Trivedi, 2008) to as high as 70.9% (Pohl et al., 2021). Burnout is a multidimensional condition caused by a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal work-related stress, characterized by overwhelming exhaustion, interpersonal detachment or cynicism towards job, which emerges with a reduced sense of professional efficacy (Canu et al., 2021; Maslach et al., 2001).

The burnout among teachers has been linked to a variety of factors that include workplace-related factors such as years of teaching experience, class size, job satisfaction, the subject taught, conflicting beliefs, disintegration of the workplace, strained relationships with coworkers, loss of autonomy, insufficient compensation, absence of equity, high workload and time limits, resource shortages, fear of violence, student behavior issues, role ambiguity and conflict, limited opportunities for advancement, inadequate support, and low participation in decision-making (Abel & Sewell, 1999; Friedman, 1991; Lee & Ashforth, 1996; Hadi et al., 2009; Maslach & Leiter, 1999; Ratanasiripong et al., 2022). In recent years, the challenges faced by teachers have intensified, particularly due to the additional pressures brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2021). Such work-related stressors are often pervasive. Teachers face heavy workloads, role ambiguity, large classes with diverse learning needs, limited organizational support, and frequent classroom management difficulties. Prolonged exposure to these adverse conditions erodes teachers’ mental and physical resources, eventually precipitating the burnout syndrome (Agyapong et al., 2023; Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017; Talavera-Velasco et al., 2018).

Higher levels of occupational stress have been associated with increased rates of absenteeism, staff turnover, higher intentions to quiet, lower teaching effectiveness and satisfaction and numerous negative health effects including fatigue, sleep disturbances, hormonal imbalances (Agyapong et al., 2022). These issues not only affect teachers’ health and personal lives but also impair their job performance and productivity, with indirect consequences for students, such as the quality of education they receive (Agyapong et al., 2022). Since ongoing burnout can evolve into mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression (Agyapong et al., 2022; Chang, 2022; Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017), this context underscores the importance of identifying and understanding the protective factors that contribute to mitigate the impact of burnout on teaching profession.

As mentioned above, one critical set of contributors to burnout are psychosocial risk factors in the work environment. The present study aims to systematically assess these risk factors, through an assessment conducted with the Health and Work Survey (INSAT), developed to evaluate working conditions and their effects on health and well-being (Barros et al., 2017). The INSAT survey comprehensively covers dimensions of the work environment (e.g. work pace, organizational climate, relational support, emotional demands) and has been used in sectors such as education to identify areas of psychosocial strain. Prior research using INSAT and similar surveys has found that high levels of psychosocial risks at work tend to correlate with negative outcomes like stress, musculoskeletal disorders, and burnout symptoms (Baylina et al., 2025; Barros & Baylina, 2024). These findings reinforce that unfavorable psychosocial working conditions are risk factors of teachers’ burnout, warranting interventions at the organizational level.

At the same time, the present study aims to investigate personal resources that might help teachers to cope with stress and resist burnout. Among these, emotional intelligence has emerged as a potentially important protective factor in the teaching profession (Macaranas, Ladringan, & Maniego, 2025; Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017; Fathi et al., 2021). Emotional intelligence broadly refers to the capacity to recognize, understand, and manage emotions in oneself and others, which encompasses a range of self-perceived, emotion-related abilities that enable individuals to recognize, interpret, process and use (Fiorilli et al., 2019; Mérida-López et al., 2020). Teachers with higher emotional intelligence are thought to better navigate the emotional demands of the classroom. For instance, they are better equipped to calmly resolve conflicts, sustain motivation, and recover from setbacks, which reduces their susceptibility to burnout.

A systematic review has demonstrated negative associations between emotional intelligence and burnout, suggesting that educators with higher emotional intelligence tend to report lower exhaustion and depersonalization (Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017; Puertas Molero et al., 2019). Considering these results, emotional intelligence can help teachers reduce burnout and stay engaged in their work (Wang, 2022), likely by enabling more effective stress management, emotional regulation, and use of social support. Given these benefits, emotional intelligence is increasingly seen as valuable personal competency for teachers.

Although both psychosocial risk factors and emotional intelligence have been independently linked to burnout, there is a notable gap in the literature regarding their interactive effects. In other words, it remains underexplored whether a teacher’s emotional intelligence can moderate (i.e. buffer or amplify) the impact of adverse psychosocial work conditions on their burnout levels. We may infer that personal resources might act as a buffer against organizational stressors and a endorse protective factors for psychological well-being (Chang, 2009, 2013; Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017; Dobles Villegas et al. 2025), but direct empirical investigations in educational settings are scarce.

To address this gap, the present study aims to determine whether teachers’ emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between psychosocial risk factors and burnout. In a sample of school teachers, we assessed psychosocial risks, emotional intelligence and burnout, and then tested whether high emotional intelligence attenuates the association between psychosocial risk factors and burnout symptoms.

By clarifying this moderating role of emotional intelligence, the study aims to advance our understanding of how individual emotional competencies can protect against burnout in the teaching profession. Such insights have important practical implications. If emotional intelligence indeed buffers the effects of workplace stressors, then interventions that enhance teachers’ emotional intelligence (through training or professional development) alongside with improvements in work conditions could be a promising dual strategy to combat teacher burnout (Wang, 2022).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethics

In this cross-sectional study, a non-probabilistic convenience sample was collected through a snowball method, among Portuguese teachers from public and private secondary schools. Participants were reached by personal networks contacts who agreed to disseminate the study among secondary school teachers on social media platforms (e.g., WhatsApp and LinkedIn). Data were collected online by distributing a questionnaire via Google Forms between February 6th, 2025 and April 15th, 2025.

The questionnaire included various scales, starting with a cover page that briefly explained the study’s objectives. The criteria for participation involved informed consent, voluntary involvement, and confidentiality. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before they completed the survey. The estimated time to complete the questionnaire was about 15 minutes.

This study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Human and Social Sciences of the University of Fernando Pessoa (protocol code, Ref. FCHS/PI – 475/23-4 and the date of approval on 20 March 2024, Porto, Portugal) and adhered to all procedures outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Participants

The sample of this study consisted of 215 secondary school teachers of public (81.7%) and private (18.3%) schools, 73.5% of whom were female, with participant age varying from 22 to 67 years old (mean = 51.55, median = 53, SD = 9.724), with the majority reporting being married or in a de facto union (66.2%). 74.9% held a graduate university degree, 21% a master’s degree and 4.1% a PhD level. Most of the participants were employed in public schools (81.7%) under permanent work contracts (79.5%).

2.3. Instruments

This study employed the Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT-23) to assess burnout dimensions, the Health and Work Survey (INSAT) to evaluate psychosocial risk factors work-related and the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS-P) to evaluate emotional intelligence.

BAT-23, developed by Schaufeli, Desart, & De Witte (2020), consists of 23 items measuring four core symptoms of burnout: exhaustion (eight items; e.g., “At work, I feel mentally exhausted”), mental distance (five items; e.g., “I struggle to find any enthusiasm for my work”), emotional impairment (five items; e.g., “At work, I feel unable to control my emotions”), and cognitive impairment (five items; e.g., “At work, I have trouble staying focused”). The BAT-23 provides an integrated perspective, as all four dimensions are interconnected and relate to the same underlying condition. Responses to all items were recorded on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) (Schaufeli et al., 2020). In this study, the Portuguese version of the Burnout Assessment Tool was used (Sinval et al., 2022). The scale establishes two cut-off points: (a) scores beginning at 2.59 indicate burnout risk, and (b) scores exceeding 3.02 suggest positive burnout diagnoses. Cronbach’s alpha values for our sample were 0.946 for all scale, 0.937 for the Exhaustion core symptom subscale, 0.913 for the Mental Distance core symptom subscale, 0.908 for the Cognitive Impairment core symptom subscale, and 0.914 for the Emotional Impairment core symptom subscale.

INSAT is a Portuguese self-reported questionnaire that evaluates working conditions, risk factors, and health problems. The questionnaire on psychosocial risks (PSR) comprises 52 items distributed across seven categories with varying numbers of items: high demands and work intensity (eleven items; e.g., “Frequent interruptions”), working hours (eight items; e.g., “Exceeding normal working hours”), lack of autonomy (four items; e.g., “Not being able to participate in decisions regarding my work”), work relations (eight items; e.g., “Needing help from colleagues and not having it”), employment relations (ten items; e.g., “I feel exploited most of the time”), emotional demands (seven items; e.g., “Being exposed to the difficulties and/or suffering of other people”), and ethical and value conflicts (four items; e.g., “My professional conscience is undermined”). Responses to all items were recorded on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not being exposed) to 5 (being exposed with high discomfort). INSAT demonstrates good internal consistency in a Rasch PCM analysis, with a reliability coefficient > 0.8 (Barros et al., 2017). The Cronbach’s alpha values scale has for our sample were 0.942 for all scale and for each category: 0.833 for high demands and work intensity, 0.869 for working times, 0.893 for lack of autonomy, 0.931 for work relations with coworkers and managers items, 0.772 for employment relations with the organization, 0.934 for emotional demands, and 0.895 for work values.

The WLEIS Emotional Intelligence Scale (Wong and Law, 2002) was used to evaluate emotional intelligence. This scale is a widely used self-report instrument designed to assess emotional intelligence based on the four-branch ability model proposed by Mayer and Salovey (1997). The scale consists of 16 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree), divided into four subscales, each containing four items: Self-emotion appraisal (SEA); Others’ Emotion Appraisal (OEA); Use Of Emotion (UOE) and Regulation of Emotion (ROE). In this study, we used the Portuguese version of the WLEIS Emotional Intelligence Scale (Rodrigues, Rebelo, & Coelho, 2011) with strong internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from .78 to .86 across subscales and construct validity. It maintains the conceptual integrity of the original scale, and the four-factor structure was preserved with the four dimensions of emotional intelligence: (i) the evaluation and expression of emotions themselves, (ii) evaluation and recognition of emotions in others, (iii) use of emotions, (iv) regulation of emotions of one’s own. Cronbach’s alpha values for our sample were 0.859 for all scales, 0.837 for the Self Emotional Appraisal (SEA) subscale, 0.800 for the Others’ Emotional Appraisal (OEA) subscale, 0.785 for the Use of Emotion (UOE) subscale, and 0.835 for the Regulation of Emotion (ROE) subscale.

2.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the IBM SPSS statistical program for Windows, version 29.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and with PROCESS macro (model 4) for mediation analysis and PROCESS macro (model 1) for moderation analysis (Hayes, 2022). A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was adopted. Frequencies were used to present sociodemographic characteristics. Descriptive analysis, including range, mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis, was performed on the mean scores of psychosocial risk factors sub-scales, burnout sub-scales and emotional intelligence sub-scales. Subsequently, a correlation analysis with the Pearson coefficient was performed to analyse the existing correlations. Finally, the statistical tool the PROCESS macro was applied, based on the principles of ordinary least squares (OLS) linear regression, to analyse the interaction between psychosocial risks (PSR) and Burnout with emotional intelligence (EI) as moderator (Model 1), and (OLS) linear regression with bootstrapping for mediation, to test several paths: a) effect of PSR on EI; b) effect of EI on Burnout, controlling for PSR; c) direct effect of PSR on Burnout, controlling for EI, and d) indirect effect between paths a and b (model 4). The adherence to the assumptions of the method was verified, and the obtained results were deemed reliable.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics, means and standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis of the distributions of each subscale, namely burnout (exhaustion, mental distance, emotional impairment, and cognitive impairment; psychosocial risks factors (work intensity (WI), working hours (WH), autonomy and initiative (AI), social work relations (SWR), employment relations (ER), emotional demands (ED) and Work values (WV); emotional intelligence (Self-emotion appraisal (SEA); Others’ Emotion Appraisal (OEA); Use Of Emotion (UOE) and Regulation of Emotion (ROE), respectively.

Data showed that all variables were approximately normally distributed, with skewness indices (│γ1│) 0 and kurtosis indices (│γ2│) within ±2, meeting the recommended thresholds for normality (George, & Mallery, 2010).

3.2. Correlation Analysis

The correlation analysis is a prerequisite to support the mediation/moderation analysis. To ensure statistical validity correlation analysis was performed using the Pearson coefficient applied between 1) PSR subscales and BAT-23 subscales to show if psychosocial risk factors are associated with burnout (

Table 2); 2) WLEIS subscales and BAT-23 subscales to show if emotional intelligence may reduce burnout (justifies b path or moderation role) (

Table 3); and 3) PSR subscales and WLEIS subscales to show if emotional intelligence might be impacted by Psycho social risk factors (justifies “a” path in mediation) (

Table 4).

Data shows statistically significant positive correlations, moderate to strong, between psychosocial risk factors subdimensions and burnout subdimensions, based on Cohen’s criteria (Cohen, 1998).

Data shows not statistically significant correlations, meaning weak effect between emotional intelligence subdimensions and burnout subdimensions (Cohen, 1998).

Data shows some weak statistically significant correlations between emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks, particularly in Emotional Demands (ED) and Working Hours (WH) with ROE subdimension, and Autonomy and Initiative (AI) and Social Work Relations (SWR) with OEA subdimension. All other correlations are weak and not statistically significant. This means that ROE (Regulation of Emotion) is the most consistent protective factor, significantly negatively correlated with WH and ED. This implies that teachers who are better at managing their emotions feel less emotionally burdened by job demands. Data also shows that OEA negatively correlates with Autonomy and Social Relationships subscales. This may suggest that those who are more emotionally attuned to others are also more sensitive to interpersonal stressors, or more skilled in navigating them.

3.3. Mediation and Moderation Analysis

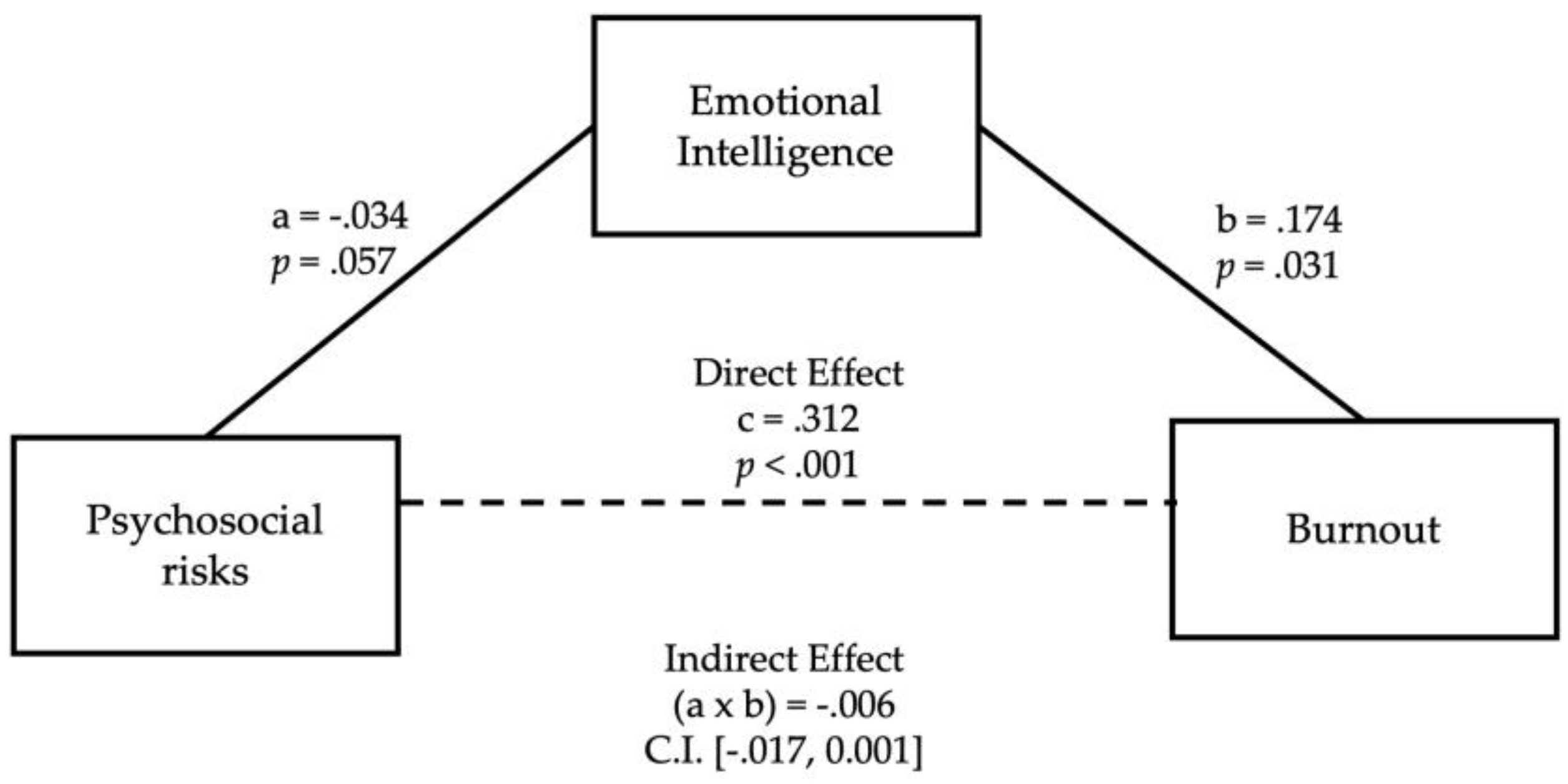

A mediation analysis using PROCESS macro (Model 4) was conducted to examine whether emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between psychosocial risk factors and burnout among teachers. Results are presented in

Table 5.

Data shows the total effect of psychosocial risk factors on burnout was significant, indicating that higher perceived risk predicts greater burnout (B = 0.312, SE = 0.021, p < .001). The effect of psychosocial risk on emotional intelligence was not significant (B = –0.034, SE = 0.018, p = .057), suggesting that emotional intelligence is not significantly affected by stress levels. Emotional intelligence, when included in the model, was a significant positive predictor of burnout (B = 0.174, SE = 0.080, p = .031), indicating a suppressor effect, as this direction contradicts theoretical expectations. The indirect effect of psychosocial risk on burnout through emotional intelligence was not significant (B = –0.006, 95% CI [–0.0169, 0.0011]).

Figure 1 helps to better visualize the mediation role of emotional intelligence on the relation between psychosocial risks and burnout.

These findings do not support a mediating role of emotional intelligence in the relationship between psychosocial risk and burnout.

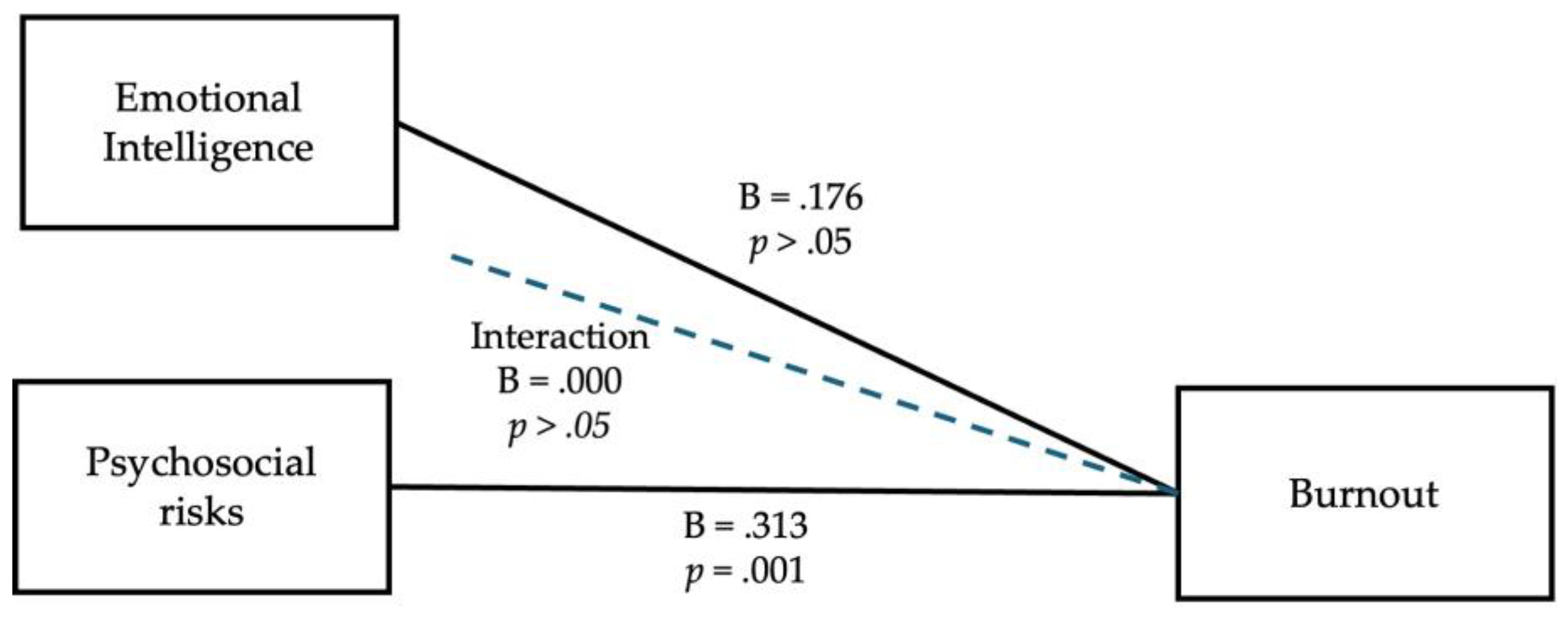

A moderation analysis was performed using PROCESS macro (Model 1) to test whether emotional intelligence moderates the effect of psychosocial risk on burnout. The overall model was significant and explained 51% of the variance in burnout,

R² = .508,

F (3, 211) = 72.65,

p < .001. Results are presented in

Table 6.

The overall model was significant and explained 51% of the variance in burnout, R² = .508, F (3, 211) = 72.65, p < .001.

Psychosocial risk was a significant positive predictor of burnout (B = .313, p = .001), indicating that higher perceived risk was associated with higher burnout symptoms. Emotional intelligence did not significantly predict burnout on its own (B = .176, p = .364), and the interaction term (PSR × EI) was not significant (B = 0.000, p = .995), indicating that emotional intelligence does not moderate the relationship between psychosocial risks and burnout.

Figure 2 helps to better visualize the mediation role of emotional intelligence on the relation between psychosocial risks and burnout.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to determine whether teachers’ emotional intelligence moderates the relationship between psychosocial risk factors and burnout.

A central concern emerging from this research is the intensity of burnout symptoms, with particular emphasis on the pronounced emotional exhaustion experienced by teachers. As expected, and in the line with several recent research (Agyapong et al., 2022; Alghamdi, & Sideridis, 2025; García-Carmona et al., 2019) data shows alarmingly high levels on exhaustion dimension of burnout for teaching profession. In fact, teachers are considered the most vulnerable workers, susceptible to burnout and emotional exhaustion - characterized by chronic fatigue, depleted emotional resources, emotionally fragile, and a sense of being overwhelmed - which is recognized the most debilitating dimension of burnout in the teaching profession (Gkontelos et al., 2023; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2021).

This study emphasises elevated levels of psychosocial risks (PSR) that can be associated with increased complaints of emotional exhaustion. The correlations confirmed that psychosocial risk factors, particularly emotional demands, working hours, lack of autonomy and initiative, and work values, were strongly and positively associated with burnout symptoms such as exhaustion, and moderating and positively associated with mental distance, and emotional impairment. These findings are aligned with existing research highlighting the central role of job stressors in the development of teacher burnout (Abel, & Sewell, 1999; Alghamdi, & Sideridis, 2025; Chang, 2009, Chang, 2022; Jomuad et al., 2021).

Data shows that, overhead the emotional demands, working hours, lack of autonomy and working values are the main psychosocial risk factors with the strongest association to elevated levels of teacher burnout, particularly in the dimension of emotional exhaustion. These factors reflect the cumulative effect of these demands that induce chronic strain, conflicting demands, emotionally charged interactions, that contributes to a sustained depletion of emotional resources, reinforcing the vulnerability of educators to burnout.

In fact, psychosocial risk factors have a significant influence on the manifestation of burnout symptoms, highlighting the importance of research in this field for understanding the widespread impact of these risks on teachers. Data shows that teachers are exposed to high emotional demands (managing diverse classroom behaviours, dealing with students’ difficulties and fears and maintaining discipline) can be stressful and anxiety-inducing. Reinforced in the results obtained with high job demands and low social support—two prominent psychosocial risk factors - contribute directly to emotional exhaustion and psychological strain, making teaching one of the most stress-prone professions (Agyapong et al., 2023; Cavallari et. al, 2024). When combined with other psychosocial risks found in our study like, working hours (extensive workload, including lesson planning, grading, and extracurricular activities) and lack of autonomy and initiative can contribute to chronic stress, burnout, and a decline in overall mental well-being, and increase the prevalence of burnout symptoms.

Educators face a complex web of psychosocial risks that significantly affect their physical, emotional, and social well-being (Borrelli et al., 2014; Guo et al, 2024; Peng et al., 2022; Xie, 2023), indicating that burnout is not merely a localized phenomenon, but a systemic issue exacerbated by increasing workloads, emotional labour, and insufficient institutional support.

Several studies indicate that teachers’ emotional intelligence is a key predictor of psychological well-being and a safeguard against burnout (Doyle, et al., 2024; Lucas-Mangas et al. (2022) reinforced by recent systematic reviews (Puertas Molero et al., 2019; Mérida-López & Extremera, 2017) that specifically analyse the relation between emotional intelligence and teacher burnout, offering strong evidence that emotional intelligence acts as a protective factor. Moreover, emotional skills used to identify feelings and emotions facilitate more effective emotional strategies to deal with negative events; teachers with more emotional competencies are better prepared to handle strain and emotional burden and develop regulation strategies to handle with emotional exhaustion (Chen et al., 2024; Fiorilli et al., 2019; Shenaar-Golan, et al, 2020).

However, in our study the mediation model shows new insights on the role of emotional intelligence (EI) through psychosocial risk factors (PSR) and burnout. Our results suggest that the emotional intelligence protection is not enough to provide teachers lower levels of burnout.

If we assume that emotional intelligence is the capacity for self-awareness, as well as the ability to identify the emotions, feelings and needs of others, with a perspective to establishing cooperative relationships, to have an effective problem-solving and decision-making (Borawski et al., 2022; Fathi et al., 2021; Gameiro, & Ferreira, 2024), our results show that emotional intelligence can be helpful but is not sufficient against burnout. In fact, while emotional intelligence has been widely recognized as a protective factor against burnout, the results suggest that its role in preventing burnout may be more limited than previously assumed.

The analysis of emotional intelligence data showed weak and inconsistent correlations with both psychosocial risks and burnout. Although there were two dimensions (such as others’ emotion appraisal (OEA), and regulation of emotion (ROE)) that showed a modest negative correlation with emotional demands and emotional impairment, the extent and strength of these effects were constrained.

The theoretical role of emotional intelligence as a psychological resource, both mediation and moderation models, was analyzed using PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2022). The mediation analysis (Model 4) showed no significant indirect effect of psychosocial risk on burnout through emotional intelligence. Despite the regression model’s weak association between emotional intelligence and burnout, the impact’s unexpectedly positive direction raises the possibility of a measurement overlap or suppression effect.

Results from the moderation analysis (Model 1) were likewise not statistically significant. Psychosocial risk’s effect on burnout was not mitigated by emotional intelligence, and the interaction term (PSR × EI) added no new explanatory power to the model.

Psychosocial risk was a significant positive predictor of burnout (B = .313, p = .001), indicating that higher perceived risk was associated with higher burnout symptoms. Emotional intelligence did not significantly predict burnout on its own (B = .176, p = .364), and the interaction term (PSR × EI) was not significant (B = 0.000, p = .995), indicating that emotional intelligence does not moderate the relationship between psychosocial risks and burnout.

Overall, these results suggest that emotional intelligence does not play a strong role in reducing or buffering burnout, whereas psychosocial risk factors remain strong and consistent predictors of burnout. This prompts important reflection on whether emotional intelligence, on its own, is sufficient to mitigate the adverse effects of occupational stressors among teachers, particularly when exposure to high levels of psychosocial risks may override or diminish its protective role.

Our findings are consistent with previous literature (Almeneessier, & Azer, 2023; Silva et al. (2023): although EI was inversely related to burnout, the strength of this relationship was weak to moderate, indicating that EI alone may not be sufficient to buffer individuals - particularly educators and healthcare professionals - from chronic stress and emotional fatigue. Souza and Lima (2023) highlighted that not all components of EI contribute equally to burnout prevention, and that contextual and organizational factors often outweigh individual emotional competencies. Furthermore, while emotional intelligence facilitates emotional regulation, it must be supported by adaptive coping strategies and systemic interventions to effectively mitigate burnout (Ferreira, & Martins, 2024).

These findings underscore the need for a more holistic approach to addressing burnout - one that places teachers’ work activity at the center of intervention strategies – improving working conditions and organizational support. Rather than relying solely on individual emotional competencies, such as emotional intelligence, this perspective includes integrating organizational context determinants (time pressure, classroom disruption, workload stressors, technical and administrative difficulties, disruptive class management, and work climate)

A teacher-centered approach to burnout prevention must move beyond individual psychological resources to address to organizational dimensions of the profession itself. Reshaping the conditions under which teachers perform their professional duties and also prioritize collaborative practices, professional autonomy, and recognition of effort and expertise, fostering emotional and mental well-being. Such systemic approach is crucial to reducing burnout in a sustainable and effective way, crucial to educational system’s capacity to create conditions that value and sustain teachers, by the idea of a holistic health and well-being.

Although this study offers important contributions of the role of emotional intelligence to psychosocial risk factors and burnout research, it is important to acknowledge some limitations. While this study highlights the moderation and mediation role of emotional intelligence, it might be important to analyse the role of school organizational climate and leadership and, also, age and gender differences. This cross-sectional design with a self-reported questionnaire may be expanded to enlarge the sample. Replicating this study in different populations would help confirm the validity of the findings.

5. Conclusions

Our findings provide relevant insights that may have useful theoretical and practical

implications. From the theoretical perspective, further research is needed to deepen the analysis of psychosocial risk differences. It is important to confirm whether the results of the present study show that some psychosocial risk factors can have a very different impact on burnout. In response to burnout, teachers have to deal with a variety of negative social and psychological consequences. Those psychological effects are being widely reported in scientific literature. Emotional intelligence plays an important role for coping with adversity, namely emotional regulation, but not sufficient, on their own, to prevent or combat burnout. Burnout is a multifaceted phenomenon deeply rooted in organizational, social, and working conditions that must be addressed through comprehensive and sustained interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B., P.B and C.F.; methodology, C.B., P.B., C.F.; validation, C.B., P.B., C.F.; formal analysis, C.B., P.B., C.F.; investigation, C.B., P.B., C.F.; resources, C.B., P.B., C.F.; data curation, C.B. and P.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.B., P.B and C.F.; writing—review and editing, C.B., P.B and C.F.; supervision, C.B., P.B and C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. It has been approved as following the Ethics and Deontology Committee of Fernando Pessoa University protocol (Porto, Portugal, Ref. FCHS/PI – 475/23, and the date of approval on 20 March 2024, Porto, Portugal).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. This research involved teachers participating anonymously in an online survey. Before completion, an accompanying cover letter explained the confidentiality and purpose of the study, the potential objectives, and the voluntary participation.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abel, M. H., & Sewell, J. (1999). Stress and burnout in rural and urban secondary school teachers. The journal of educational research, 92(5), 287-293. [CrossRef]

- Afridi, A., Ambreen, S., & Durrani, S. (2024). A Cross-Sectional Analysis of The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Burnout in University Teachers. Annals of Human and Social Sciences, 5(2), 375-382. [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, B., Brett-MacLean, P., Burback, L., Agyapong, V. I. O., & Wei, Y. (2023). Interventions to reduce stress and burnout among teachers: A scoping review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 20(9), 5625. [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, B., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Burback, L., & Wei, Y. (2022). Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among teachers: A scoping review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(17), 10706. [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, M. H., & Sideridis, G. (2025). Identifying subgroups of teacher burnout in elementary and secondary schools: The effects of teacher experience, age, and gender. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, Article 1406562. [CrossRef]

- Almeneessier, A. S., & Azer, S. A. (2023). Exploring the relationship between burnout and emotional intelligence among academics and clinicians at King Saud University. BMC medical education, 23(1), 673. [CrossRef]

- Baylina, P., Fernandes, C. & Barros, C. (2025). The Impact of Psychosocial Risks on Burnout: Tracing the Pathways to Professional Exhaustion? In: Santos Baptista et al. (Eds). Occupational and Environmental Safety and Health VI, 231 Biomechanics, Occupational Psychosociology and New Trends, 231 (Chap 10). ISBN 978-3-031-82290-2, 640989. [CrossRef]

- Barros, C., Cunha, L., Baylina, P., Oliveira, A., & Rocha, Á. (2017). Development and validation of a health and work survey based on the Rasch model among Portuguese workers. Journal of Medical Systems, 41, Article 79. [CrossRef]

- Barros, C., & Baylina, P. (2024). Disclosing strain: How psychosocial risk factors influence work-related musculoskeletal disorders in healthcare workers preceding and during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(5), 564. [CrossRef]

- Baudry, A. S., Grynberg, D., Dassonneville, C., Lelorain, S., & Christophe, V. (2018). Sub-dimensions of trait emotional intelligence and health: A critical and systematic review of the literature. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 59(2), 206–222. [CrossRef]

- Borawski, D., Sojda, M., Rychlewska, K., & Wajs, T. (2022). Attached but Lonely: Emotional Intelligence as a Mediator and Moderator between Attachment Styles and Loneliness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14831. [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, I., Benevene, P., Fiorilli, C., D’Amelio, F., & Pozzi, G. (2014). Working conditions and mental health in teachers: a preliminary study. Occupational medicine (Oxford, England), 64(7), 530–532. [CrossRef]

- Canu, I. G., Marca, S. C., Dell’Oro, F., Balázs, Á., Bergamaschi, E., Besse, C., ... & Wahlen, A. (2021). Harmonized definition of occupational burnout: A systematic review, semantic analysis, and Delphi consensus in 29 countries. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 47(2), 95. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, V. S., Guerrero, E., Chambel, M. J., & González-Rico, P. (2016). Psychometric properties of WLEIS as a measure of emotional intelligence in the Portuguese and Spanish medical students. Evaluation and Program Planning, 58, 152-159. [CrossRef]

- Cavallari, J. M., Trudel, S. M., Charamut, N. R., Suleiman, A. O., Sanetti, L. M. H., Miskovsky, M. N., Brennan, M. E., & Dugan, A. G. (2024). Educator perspectives on stressors and health: A qualitative study of U.S. K–12 educators. BMC Public Health, 24, Article 2733. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M. L. (2009). An appraisal perspective of teacher burnout: Examining the emotional work of teachers. Educational psychology review, 21(3), 193-218.

- Chang, H. (2022). Stress and burnout in EFL teachers: The mediator role of self-efficacy. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 880281. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M. L. (2013). Toward a theoretical model to understand teacher emotions and teacher burnout in the context of studentmisbehavior: appraisal, regulation and coping. Motivation and Emotion, 37, 799–817.

- Chen, Y. C., Huang, Z. L., & Chu, H. C. (2024). Relationships between emotional labor, job burnout, and emotional intelligence: an analysis combining meta-analysis and structural equation modeling. BMC psychology, 12(1), 672. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Dobles Villegas, M. T., Sanchez-Sanchez, H., Schoeps, K., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2025). Emotional Competencies and Psychological Well-Being in Costa Rican Emerging Adults: The Mediating Role of Self-Esteem and Resilience. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 15(5), 89. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, N. B., Downer, J. T., & Rimm-Kaufman, S. E. (2024). Understanding teachers’ emotion regulation strategies and related teacher and classroom factors. School Mental Health, 16, 123–136. [CrossRef]

- Fathi, J., Derakhshan, A., & Torabi, S. (2021). The interplay of EFL teachers’ emotion regulation, self-efficacy, and emotional intelligence in their job burnout. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 9(2), 59–76. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L., & Martins, A. (2024). The relation between emotional intelligence, resilience, and burnout in Portuguese individuals. Global Health, Education & Social Sciences, 2(3). [CrossRef]

- Fiorilli, C., Benevene, P., De Stasio, S., Buonomo, I., Romano, L., Pepe, A., & Addimando, L. (2019). Teachers’ burnout: The role of trait emotional intelligence and social support. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2743. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, I. A. (1991). High and low-burnout schools: School culture aspects of teacher burnout. The Journal of educationalresearch, 84(6), 325-333. [CrossRef]

- Gameiro, F., & Ferreira, P. (2024). The relation between emotional intelligence, resilience and burnout in Portuguese individuals. Global Health Econ Sustain, 2(3):2738. [CrossRef]

- García-Carmona, M., Marín, M. D., & Aguayo, R. (2019). Burnout syndrome in secondary school teachers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 22(1), 189–208. [CrossRef]

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2010). SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 17.0 Update (10th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Gkontelos, A., Vaiopoulou, J., & Stamovlasis, D. (2023). Burnout of Greek Teachers: Measurement Invariance and Differences across Individual Characteristics. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(6), 1029–1042. [CrossRef]

- Guo, L., Awiphan, R., Wongpakaran, T., Kanjanarat, P., & Wedding, D. (2024). Social Anxiety among Middle-Aged Teachers in Secondary Education Schools. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(8), 2390-2403. [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A. A., Naing, N. N., Daud, A., Nordin, R., & Sulong, M. R. (2009). Prevalence and factors associated with stress among secondary school teachers in Kota Bharu, Kelantan, Malaysia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health, 40(6), 1359-1370.

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. (Third Edition ed.). The Guilford Press. ISBN 9781462549030.

- Jomuad, P. D., Antiquina, L. M. M., Cericos, E. U., Bacus, J. A., Vallejo, J. H., Dionio, B. B., Bazar, J. S., Cocolan, J. V., & Clarin, A. S. (2021). Teachers’ workload in relation to burnout and work performance. International Journal of Educational Policy Research and Review, 8(2), 48–53. [CrossRef]

- Macaranas, A. L. C., Ladringan, E. A. P., & Maniego, A. F. (2025). The mediating role of emotional intelligence between work-related stress and work engagement. International Journal of Future Multidisciplinary Research, 3(3), Article 45436. https://www.ijfmr.com/papers/2025/3/45436.pdf.

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (1999). Teacher burnout: A research agenda. In R.V. Vandenberghe & M. Huberman (Eds.), Understanding and preventing teacher burnout: A sourcebook of international research and practice (pp. 295-303). Cambridge University Press.

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey & D. J. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications (pp. 3–31). New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Mendonça, N. R. F., Santana, A. N., Bueno, J. M. H. (2023). The Relationship Between Burnout and Emotional Intelligence: A Meta-Analysis. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho, 23(2), 2471-2478. [CrossRef]

- Mérida-López, S., & Extremera, N. (2017). Emotional intelligence and teacher burnout: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Research, 85, 121-130. [CrossRef]

- Mérida-López, S., Sánchez-Gómez, M., & Extremera, N. (2020). Leaving the teaching profession: Examining the role of social support, engagement and emotional intelligence in teachers’ intentions to quit. Psychosocial Intervention, 29(3), 141–151. [CrossRef]

- Mijakoski, D., Cheptea, D., Marca, S. C., Shoman, Y., Caglayan, C., Bugge, M. D., Gnesi, M., Godderis, L., Kiran, S., McElvenny, D. M., Mediouni, Z., Mesot, O., Minov, J., Nena, E., Otelea, M., Pranjic, N., Mehlum, I. S., van der Molen, H. F., & Canu, I. G. (2022). Determinants of Burnout among Teachers: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(9), 5776. [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N., Idoiaga Mondragon, N., Bueno-Notivol, J., Pérez-Moreno, M., & Santabárbara, J. (2021). Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid systematic review with meta-analysis. Brain sciences, 11(9), 1172. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y., Wu, H., & Guo, C. (2022). The Relationship between Teacher Autonomy and Mental Health in Primary and Secondary School Teachers: The Chain-Mediating Role of Teaching Efficacy and Job Satisfaction. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(22), 15021. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H., Gonçalves, V. O., & Assis, R. M. d. (2021). Burnout, Organizational Self-Efficacy and Self-Esteem among Brazilian Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 11(3), 795-803. [CrossRef]

- Pohl, M., Feher, G., Kapus, K., Feher, A., Nagy, G. D., Kiss, J., Fejes, É., Horvath, L., & Tibold, A. (2022). The Association of Internet Addiction with Burnout, Depression, Insomnia, and Quality of Life among Hungarian High School Teachers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 438. [CrossRef]

- Puertas Molero, P., Zurita Ortega, F., Ubago Jiménez, J. L., & González Valero, G. (2019). Influence of emotional intelligence and burnout syndrome on teachers’ well-being: A systematic review. Social Sciences, 8(6), 185. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R. T., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of applied Psychology, 81(2), 123.

- Ratanasiripong, P., Ratanasiripong, N. T., Nungdanjark, W., Thongthammarat, Y., & Toyama, S. (2022). Mental health and burnout among teachers in Thailand. Journal of Health Research, 36(3), 404-416. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, N., Rebelo, T., & Coelho, J. V. (2011). Adaptação da Escala de Inteligência Emocional de Wong e Law (WLEIS) e análise da sua estrutura factorial e fiabilidade numa amostra portuguesa. Psychologica, 55, 189–207. [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Desart, S., & De Witte, H. (2020). Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT)—Development, Validity, and Reliability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24). [CrossRef]

- Shenaar-Golan, V.;Walter, O.; Greenberg, Z.; Zibenberg, A. (2020). Emotional Intelligence in higher education: Exploring its effects onacademic self-efficacy and coping with stress. College Student Journal, 54(4), 443-459.

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2021). Teacher burnout: Relations between dimensions of burnout, perceived school context, job satisfaction and motivation for teaching. Teachers and Teaching, 27(1), 602–616. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A., & Trivedi, T. (2008). Burnout in Indian teachers. Asia Pacific Education Review, 9, 320-334. [CrossRef]

- Silva, R., Almeida, P., & Chen, Y. (2023). Exploring the relationship between burnout and emotional intelligence. BMC Medical Education, 23, Article 4604. [CrossRef]

- Sinval, J., Vazquez, A. C. S., Hutz, C. S., Schaufeli, W. B., & Silva, S. (2022). Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT): Validity Evidence from Brazil and Portugal. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3). [CrossRef]

- Souza, M. A., & Lima, T. R. (2023). A relação entre burnout e inteligência emocional: Uma metanálise. Revista Psicologia: Organizações e Trabalho, 23(1), 45–59. https://submission-pepsic.scielo.br/index.php/rpot/article/view/23748.

- Talavera-Velasco, B., Luceño-Moreno, L., Martín-García, J., & García-Albuerne, Y. (2018). Psychosocial risk factors, burnout and hardy personality as variables associated with mental health in police officers. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1478. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. (2022). Exploring the relationship among teacher emotional intelligence, work engagement, teacher self-efficacy, and student academic achievement: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 810559. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.-S., & Law, K. S. (2002). Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. [CrossRef]

- Wong, C. S., & Law, K. S. (2017). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. In Leadership perspectives (pp. 97-128). Routledge.

- Xie Y. (2023). The impact of online office on social anxiety among primary and secondary school teachers-Considering online social support and work intensity. Frontiers in psychology, 14, 1154460. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).