Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Blending recycled PLA with virgin material (typically 30–70%) maintains mechanical integrity while enhancing sustainability [23].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Processing of the Material

2.2. Characterization of the Material

3. Results and Discussion

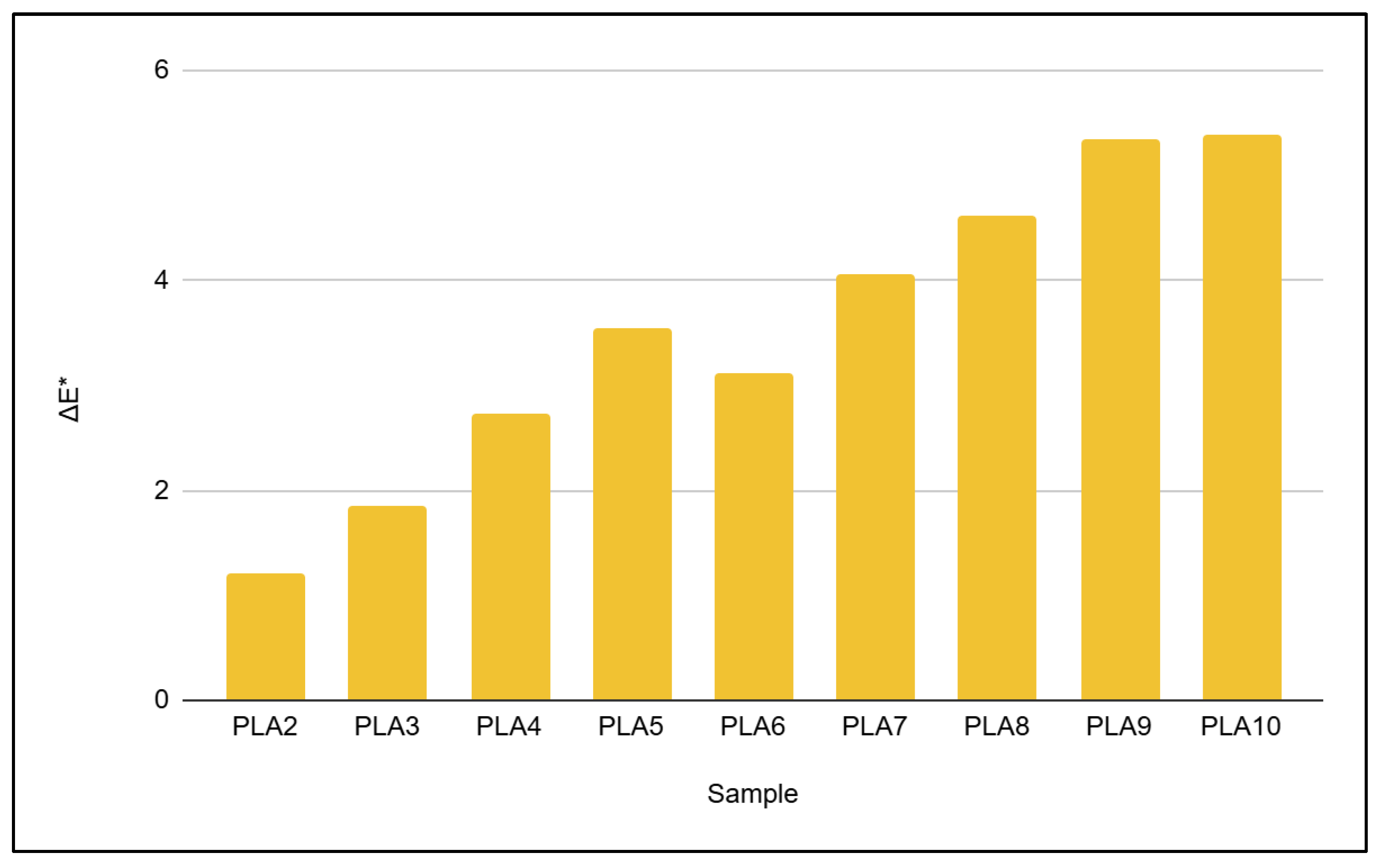

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | c* | h* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA1 | 89.598±0.253 | -5.878±0.101 | 7.98±0,112 | 9.912±0.151 | 126.382±0.106 |

| PLA2 | 88.512±0.311 | -6.216±0.134 | 8.43±0.127 | 10.478±0.181 | 126.404±0.191 |

| PLA3 | 87.956±0.499 | -6.42±0.185 | 8.64±0.230 | 10.762±0.296 | 126.614±0.169 |

| PLA4 | 87.166±0.315 | -6.67±0.107 | 8.966±0.156 | 11.174±0.187 | 126.658±0.136 |

| PLA5 | 86.428±0.199 | -6.906±0.087 | 9.216±0.157 | 11.518±0.166 | 126.84±0.310 |

| PLA6 | 86.804±0.132 | -6.766±0.067 | 9.056±0.084 | 11.308±0.094 | 126.762±0.270 |

| PLA7 | 85.982±0.276 | -7.016±0.097 | 9.454±0.107 | 11.77±0.137 | 126.572±0.232 |

| PLA8 | 85.47±0.659 | -7.166±0.22 | 9.596±0.242 | 11.978±0.324 | 126.752±0.201 |

| PLA9 | 84.81±0.688 | -7.382±0.238 | 9.84±0.297 | 12.3±0.382 | 126.872±0.065 |

| PLA10 | 84.782±0.232 | -7.366±0.071 | 9.848±0.107 | 12.298±0.123 | 126.796±0.168 |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PLA | Poly(lactide) |

| EoL | End-of-Life |

| MFI | Melt flow index |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| Tc | Crystallization temperature |

| ΔHc | Crystallization enthalpy |

| Tm | Melting temperature |

| ΔHm | Melting enthalpy |

| Xc | Relative crystallinity |

| ΔHf | Metling enthalpy of 100% crystalline PLA |

| TGA | Thermo-gravimetric analysis |

| DMA | Dynamic-mechanical analysis |

| FTIR | Infrared spectroscopy with Fourrier transformation |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| Td1 | Degradation temperature |

| Tg | Glass transition temperature |

References

- Farah, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Langer, R. Physical and mechanical properties of PLA, and their functions in widespread applications—a comprehensive review. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 367–392. [CrossRef]

- K. Jim Jem; Bowen, T. The development and challenges of poly (lactic acid) and poly (glycolic acid). Adv. Ind. and Eng. Poly. Res. 2020, 3 (2), 60-70. [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.; Wagner, M. Environmental sustainability of bio-based and biodegradable plastics: The road ahead. Chem. Soc. Rev., 2017,46, 6855-6871. [CrossRef]

- European Bioplastics. Market Development Update 2024. Available online: https://www.european-bioplastics.org/market/ (accessed on 08.07.2025.).

- Hajilou, N.; Mostafayi, S.S.; Yarin, A.L.; Shokuhfar, T. A Comparative Review on Biodegradation of Poly(Lactic Acid) in Soil, Compost, Water, and Wastewater Environments: Incorporating Mathematical Modeling Perspectives. AppliedChem 2025, 5, 1. [CrossRef]

- Maragkaki, A.; Malliaros, N.G.; Sampathianakis, I.; Lolos, T.; Tsompanidis, C.; Manios, T. Evaluation of Biodegradability of Polylactic Acid and Compostable Bags from Food Waste under Industrial Composting. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15963. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.R.; Davies, I.J.; Pramanik, A.; John, M.; Biswas, W.K. Recycling Post-Consumed Polylactic Acid Waste Through Three-Dimensional Printing: Technical vs. Resource Efficiency Benefits. Sustainability, 2025, 17, 2484. [CrossRef]

- Aryan, V.; Maga, D.; Majgaonkar, P.; Hanich, R. Valorisation of polylactic acid (PLA) waste: A comparative life cycle assessment of various solvent-based chemical recycling technologies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl., 2021, 172, 105670. [CrossRef]

- Cosate de Andrade, M.F.; Souza, P.M.S.; Cavalett, O.; Morales, A.R. Life Cycle Assessment of Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA): Comparison Between Chemical Recycling, Mechanical Recycling and Composting. J. Polym. Environ. 2016, 24, 372–384. [CrossRef]

- F.R. Beltrán, V. Lorenzo, M.U. de la Orden, J. Martínez-Urreaga. Effect of different mechanical recycling processes on the hydrolytic degradation of poly(l-lactic acid). Poly. Deg. and Stab., 2016, 133, 339-348. [CrossRef]

- T. Ramos-Hernández, J. R. Robledo-Ortíz, M. E. González-López, A. S. M. del Campo, R. González-Núñez, D. Rodrigue, A. A. Pérez Fonseca, J. Appl. Polym. Sci., 2023, 140, e53759. [CrossRef]

- McKeown, P.; Jones, M.D. The Chemical Recycling of PLA: A Review. Sustain. Chem. 2020, 1, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Piemonte, V., Sabatini, S. & Gironi, F. Chemical Recycling of PLA: A Great Opportunity Towards the Sustainable Development?. J Polym Environ 21, 640–647 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Danyluk, C.; Erickson, R.; Burrows, S.; Auras, R. Industrial Composting of Poly(Lactic Acid) Bottles. J. Test. Eval. 2010, 38, 717–723. [CrossRef]

- Musioł, M.; Sikorska, W.; Adamus, G.; Janeczek, H.; Richert, J.; Malinowski, R.; Jiang, G.; Kowalczuk, M. Forensic engineering of advanced polymeric materials. Part III—Biodegradation of thermoformed rigid PLA packaging under industrial composting conditions. Waste Manag. 2016, 52, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wei, S.; Tan, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Progress in upcycling polylactic acid waste as an alternative carbon source: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 446, 136881. [CrossRef]

- Maga, D.; Hiebel, M.; Thonemann, N. Life cycle assessment of recycling options for polylactic acid. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 86–96. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.R.; Davies, I.J.; Pramanik, A.; John, M.; Biswas, W.K. Potential of recycled PLA in 3D printing: A review. Sustain. Manuf. Serv. Econ. 2024, 3, 100020. [CrossRef]

- Finnerty, J.; Rowe, S.; Howard, T.; Connolly, S.; Doran, C.; Devine, D.M.; Gately, N.M.; Chyzna, V.; Portela, A.; Bezerra, G.S.N.; et al. Effect of Mechanical Recycling on the Mechanical Properties of PLA-Based Natural Fiber-Reinforced Composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 141. [CrossRef]

- Agüero, A.; Morcillo, M.d.C.; Quiles-Carrillo, L.; Balart, R.; Boronat, T.; Lascano, D.; Torres-Giner, S.; Fenollar, O. Study of the Influence of the Reprocessing Cycles on the Final Properties of Polylactide Pieces Obtained by Injection Molding. Polymers 2019, 11, 1908. [CrossRef]

- Fiorio, R.; Barone, A.C.; De Cillis, F.; Palumbo, M.; Righetti, M.C. Stabilization of recycled polylactic acid with chain extenders: Effect of reprocessing cycles. Polymers 2022, 14, 3522. [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, F.R.; Infante, C.; Ulagares de la Orden, M.; Martínez Urreaga, J. Mechanical recycling of poly(lactic acid): Evaluation of a chain extender and a peroxide as additives for upgrading the recycled plastic. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 46–56. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.R.; Davies, I.J.; Pramanik, A.; John, M.; Biswas, W.K. Recycling Post-Consumed Polylactic Acid Waste Through Three-Dimensional Printing: Technical vs. Resource Efficiency Benefits. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2484. [CrossRef]

- Sambudi, N.S.; Lin, W.Y.; Harun, N.Y.; Mutiari, D. Modification of Poly(lactic acid) with Orange Peel Powder as Biodegradable Composite. Polymers 2022, 14, 4126. [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, M.; Kwolek, S.; Szparaga, G.; Chrzanowski, M.; Krucińska, I. Investigation of the Influence of PLA Molecular Structure on the Crystalline Forms (α’ and α) and Mechanical Properties of Wet Spinning Fibres. Polymers 2017, 9, 18. [CrossRef]

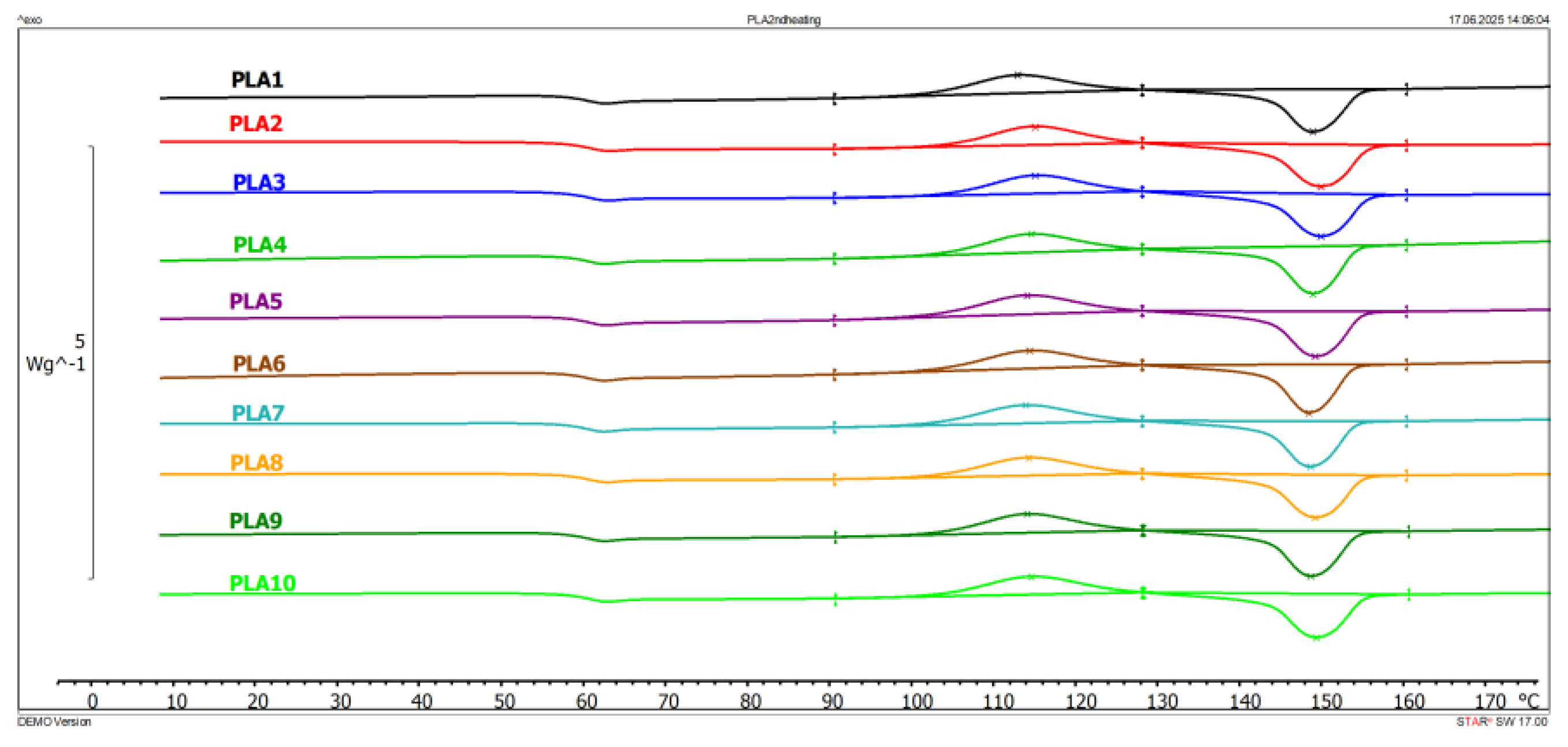

| Sample | Tg (°C) | Tcc (°C) | ΔHcc (J/g) | Tm (°C) | ΔHm (J/g) | Xc (%) | Td1 (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milled PLA | 59.5 | 113.1 | 17.6 | 148.9 | 26 | 8.96 | 370.1 |

| Extruded PLA | 59.3 | 114.4 | 22.21 | 148.8 | 23.21 | 1.07 | 369 |

| PLA1 | 59.2 | 114.4 | 23.2 | 148.7 | 24.09 | 0.95 | 368.7 |

| PLA2 | 59.9 | 115.2 | 16.79 | 149.7 | 28.84 | 12.86 | 368.5 |

| PLA3 | 59.7 | 115.2 | 16.35 | 149.8 | 28.69 | 13.17 | 368.1 |

| PLA4 | 59.5 | 114.7 | 16.93 | 148.9 | 28.25 | 12.08 | 367.5 |

| PLA5 | 59.5 | 115 | 24.47 | 149.6 | 25.53 | 1.13 | 366.9 |

| PLA6 | 59.7 | 114.2 | 18.73 | 149.2 | 28.36 | 10.28 | 367.1 |

| PLA7 | 59.4 | 114.5 | 17.24 | 148.4 | 27.94 | 11.42 | 366.6 |

| PLA8 | 59.4 | 114 | 17.74 | 148.5 | 27.59 | 10.51 | 364.8 |

| PLA9 | 59.7 | 114.4 | 17.3 | 149.2 | 27.86 | 11.27 | 365.3 |

| PLA10 | 59.5 | 114.9 | 23.15 | 149.4 | 25.16 | 2.15 | 363.7 |

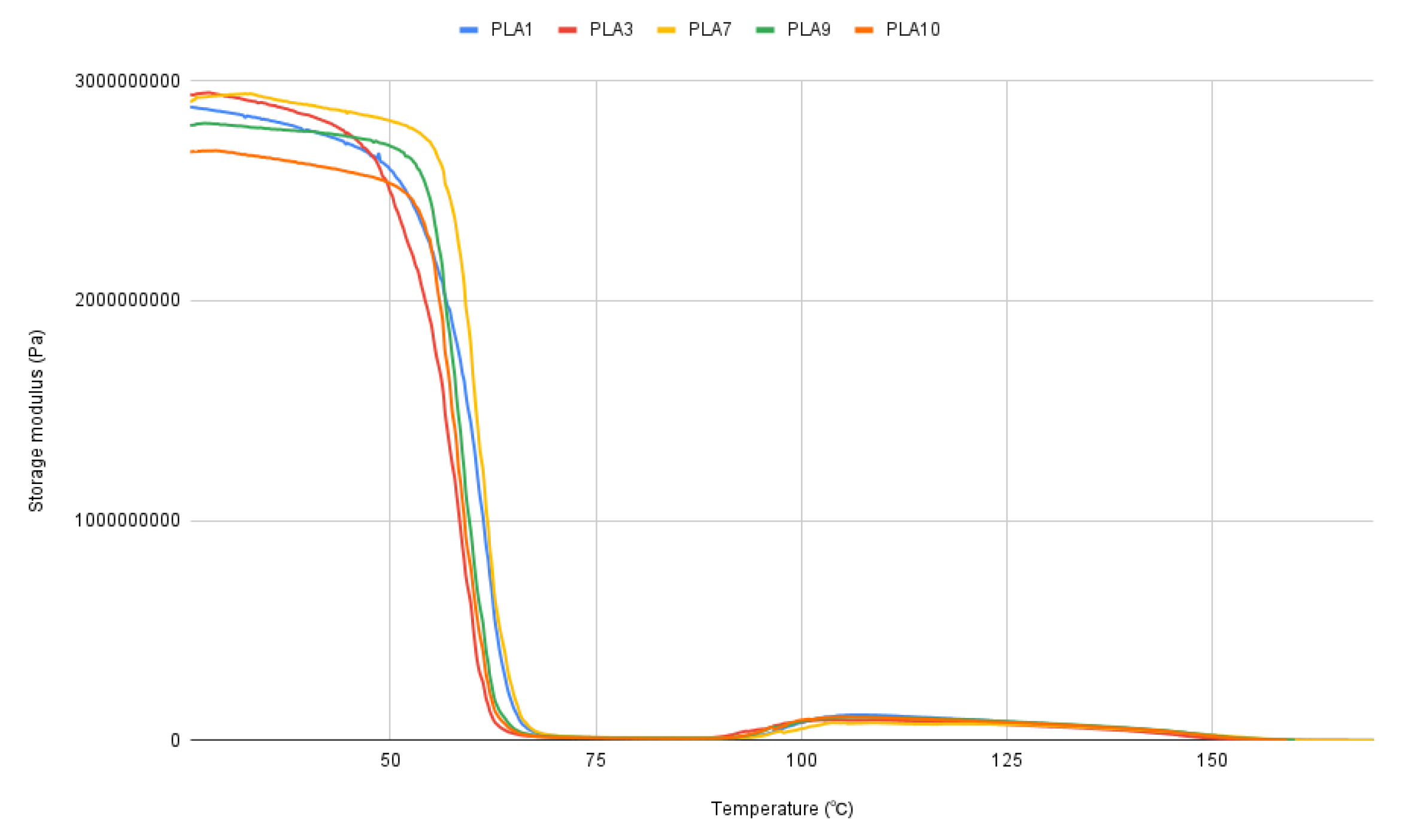

| Sample | E’ @ 30 °C (GPa) | tanδ | Tg | tanδ cc (-) | tanδ cc (°C) | E’ cc (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA1 | 2.8561 | 1.942 | 66.96 | 95,1 | 0,168 | 0,11 |

| PLA2 | 2.949 | 1.903 | 67.28 | 95,3 | 0,156 | 0,10 |

| PLA3 | 2.9365 | 1.966 | 67.56 | 95,7 | 0,166 | 0,09 |

| PLA4 | 3.0025 | 1.988 | 67.48 | 94,5 | 0,162 | 0,10 |

| PLA5 | 2.7808 | 1.973 | 67.44 | 95,6/107,7 | 0,171/0,126 | 0,07/0,08 |

| PLA6 | 2.8575 | 1.928 | 66.64 | 95,1/109,2 | 0,162/0,090 | 0,10/0,09 |

| PLA7 | 2.9219 | 1.968 | 66.72 | 95,6/105,2/115,3 | 0,158/0,122/0,106 | 0,08/0,07 |

| PLA8 | 3.0066 | 1.991 | 66.76 | 95,4/106,6 | 0,159/0,135 | 0,07/0,08 |

| PLA9 | 2.8005 | 1.961 | 66.4 | 93,3 | 0,151 | 0,10 |

| PLA10 | 2.6755 | 2.049 | 67.19 | 94,3 | 0,166 | 0,10 |

| Sample | Flexural Modulus (GPa) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | Strain at Strength (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLA1 | 3.25 ± 0.01 | 94.41 ± 0.05 | 4.25 ± 0.05 |

| PLA2 | 3.23 ± 0.05 | 94.19 ± 0.25 | 4.24 ± 0.02 |

| PLA3 | 3.3 ± 0.07 | 94.5 ± 0.63 | 4.29 ± 0.09 |

| PLA4 | 3.28 ± 0.08 | 98.59 ± 0.32 | 4.35 ± 0.02 |

| PLA5 | 3.32 ± 0.03 | 93.87 ± 0.84 | 4.1 ± 0.17 |

| PLA6 | 3.31 ± 0.01 | 93.78 ± 0.44 | 4.21 ± 0.04 |

| PLA7 | 3.33 ± 0.03 | 94.59 ± 0.43 | 4.14 ± 0.13 |

| PLA8 | 3.34 ± 0.05 | 95.27 ± 0.47 | 4.25 ± 0.05 |

| PLA9 | 3.44 ± 0.03 | 97.31 ± 1.58 | 4.08 ± 0.4 |

| PLA10 | 3.39 ± 0.05 | 98.05 ± 0.26 | 4.3 ± 0.06 |

| Sample | Tensile modulus (GPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Strain at Strength (%) | Strain at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA1 | 2.62 ± 0.23 | 68.2 ± 2.72 | 4.58 ± 0.29 | 5.18 ± 0.78 |

| PLA2 | 2.55 ± 0.26 | 67.4 ± 0.51 | 4.48 ± 0.36 | 5.72 ± 0.55 |

| PLA3 | 2.66 ± 0.33 | 67.9 ± 1.16 | 4.36 ± 0.35 | 5.34 ± 0.61 |

| PLA4 | 2 ± 0.25 | 69 ± 0.73 | 4.22 ± 0.16 | 5.92 ± 0.9 |

| PLA5 | 3.18 ± 0.15 | 67.5 ± 0.85 | 4.15 ± 0.24 | 4.94 ± 0.49 |

| PLA6 | 2.69 ± 0.38 | 66.9 ± 0.92 | 4.08 ± 0.15 | 5.79 ± 0.64 |

| PLA7 | 3.21 ± 0.32 | 66.6 ± 0.71 | 4.13 ± 0.15 | 4.99 ± 0.16 |

| PLA8 | 2.73 ± 0.15 | 65.5 ± 0.74 | 4.13 ± 0.08 | 5.04 ± 0.37 |

| PLA9 | 2.6 ± 0.33 | 66.3 ± 0.34 | 4.19 ± 0.15 | 5.67 ± 0.62 |

| PLA10 | 2.86 ± 0.23 | 67.1 ± 0.8 | 4.09 ± 0.09 | 5.3 ± 0.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).