Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Blueberry Plant Materials

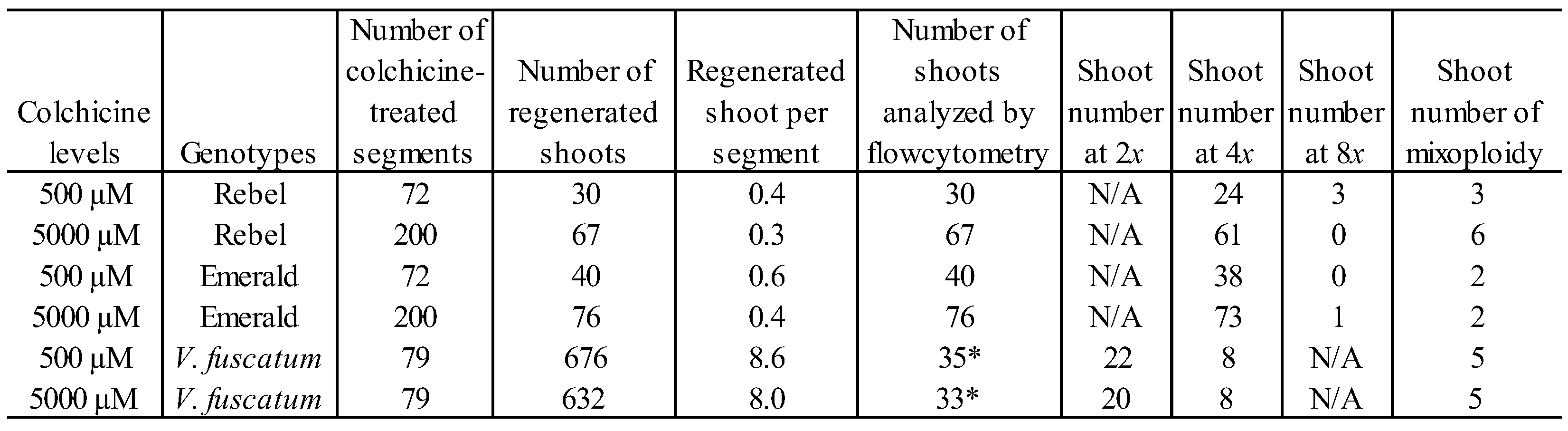

2.2. Tissue Culture and Colchicine Treatment

2.3. Rooting the Shoots from Tissue Culture

2.4. Flow Cytometry Analysis

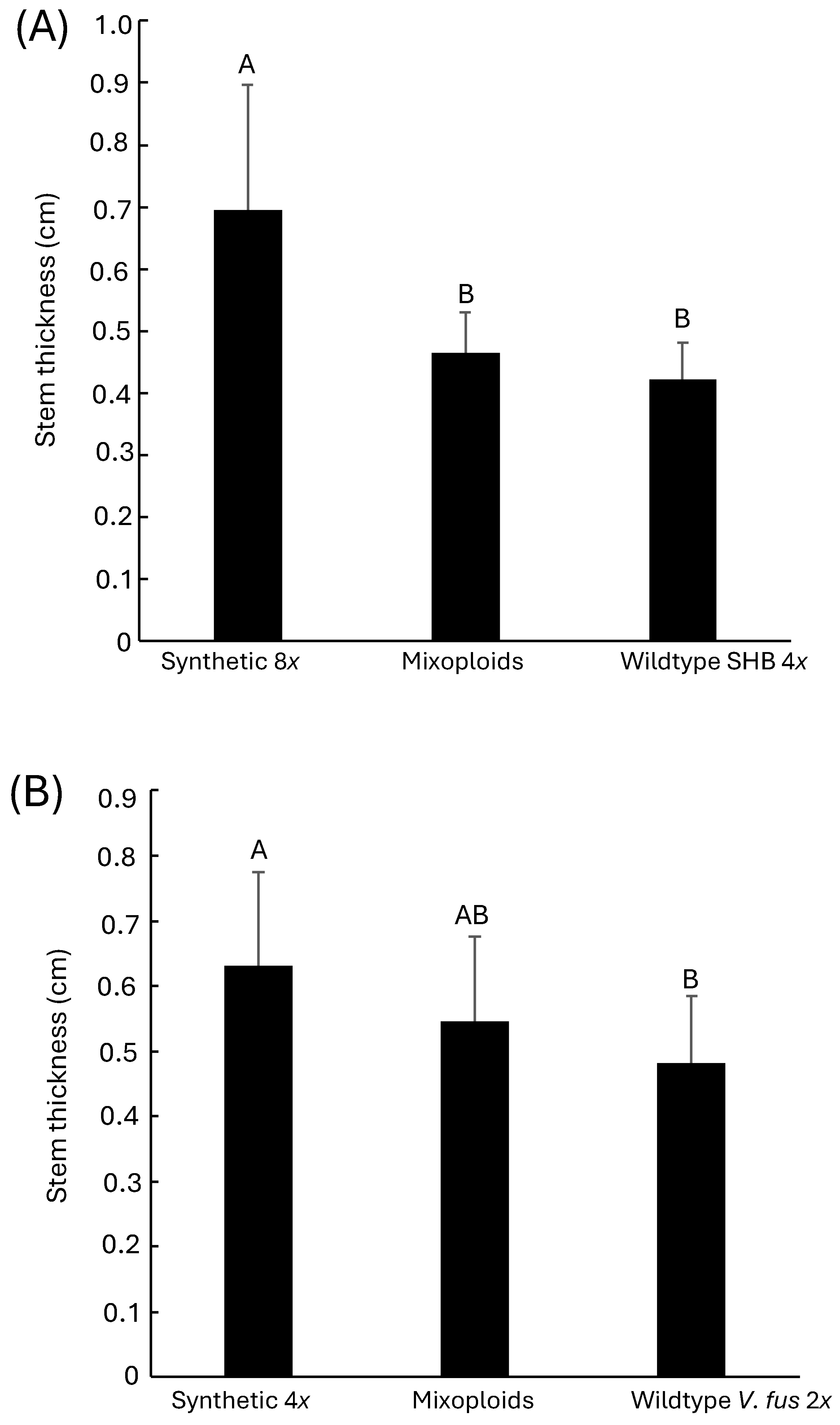

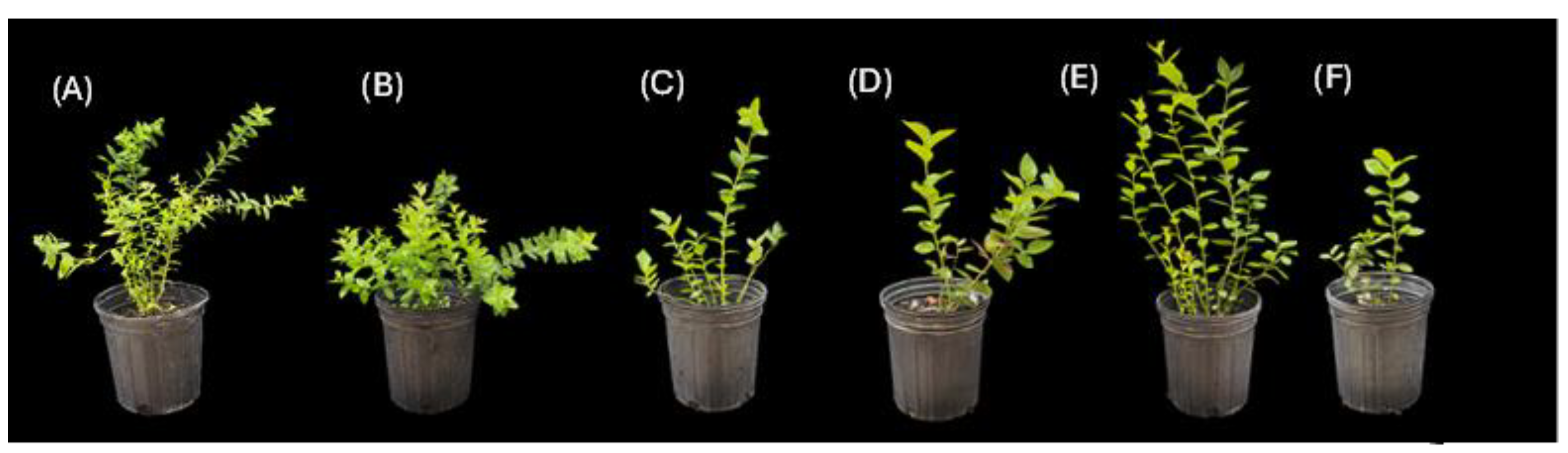

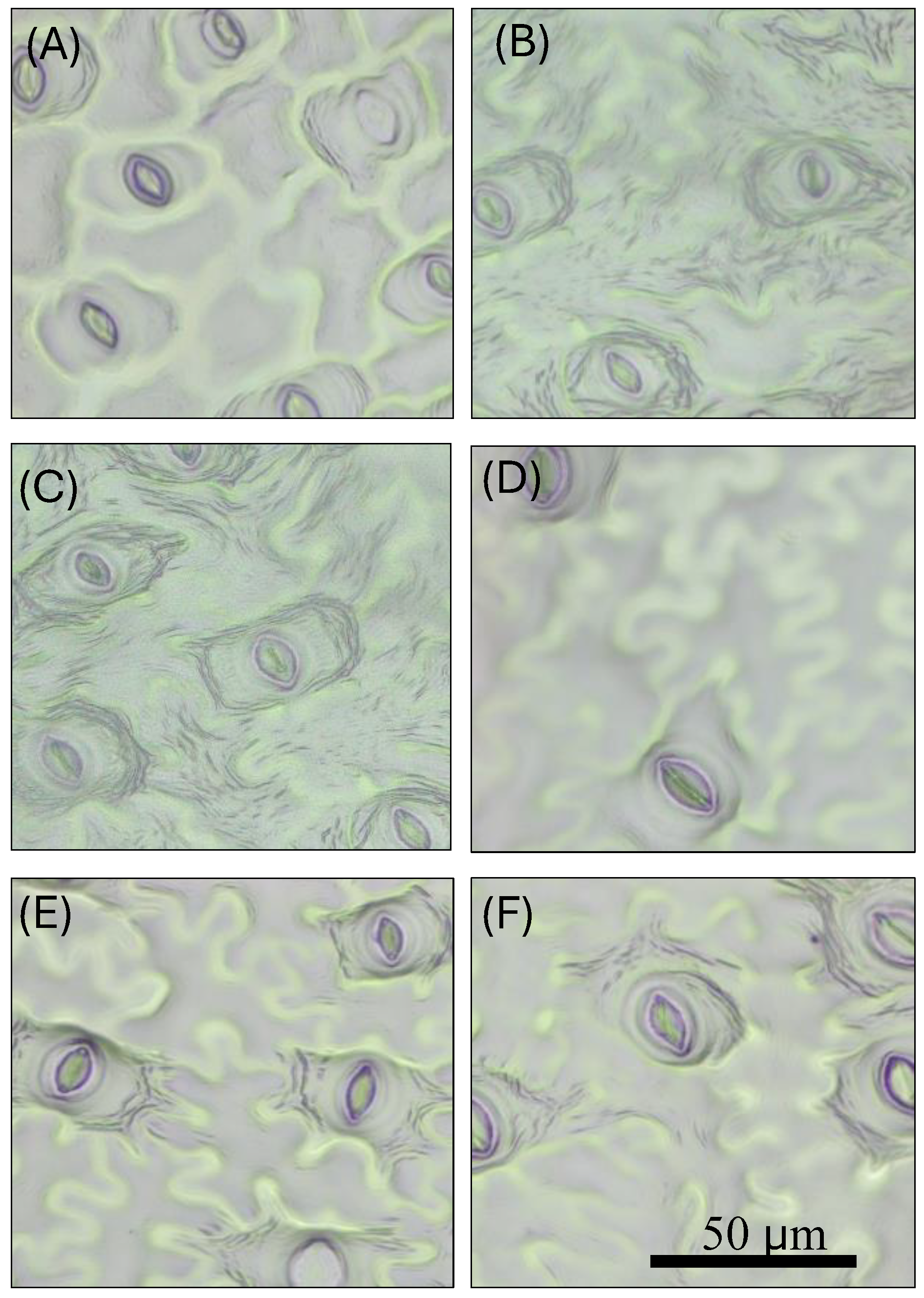

2.5. Morphological Characterization

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stull, A.J.; Cassidy, A.; Djousse, L.; Johnson, S.A.; Krikorian, R.; Lampe, J.W.; Mukamal, K.J.; Nieman, D.C.; Porter Starr, K.N.; Rasmussen, H. The state of the science on the health benefits of blueberries: a perspective. Frontiers in Nutrition 2024, 11, 1415737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammami, A.M.; Guan, Z.; Cui, X. Foreign competition reshaping the landscape of the US blueberry market. Choices 2024, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAOSTAT. 2023. doi:https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/visualize.

- Tootelian, D. National and state-specific economic impact study. 2023, https://ushbc.blueberry.org/allresources, doi:https://ushbc.blueberry.org/all-resources.

- IBO. Global Fresh Blueberry Outlook 2025–2030. 2025. doi:https://www.internationalblueberry.org/2025/04/14/global-fresh-blueberry-outlook-2025-2030/.

- Camp, W.H. The North American blueberries with notes on other groups of Vacciniaceae. Brittonia 1945, 5, 203–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Kloet, S.P. The genus Vaccinium in north America; Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1988.

- Fritsch, P.W.; Crowl, A.A.; Ashrafi, H.; Manos, P.S. Systematics and evolution of Vaccinium Sect. cyanococcus (Ericaceae): progress and prospects. Rhodora 2024, 124, 301-332, 332. [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.N. Improving highbush blueberries by breeding and selection. Euphytica 1965, 14, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coville, F.V. Blueberry chromosomes. Blueberry chromosomes. Science 1927, 66, 565-566. [CrossRef]

- Longley, A. Chromosomes in Vaccinium. Science 1927, 66, 566–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, A. Blueberry breeding: improving the unwild blueberry. J. Am. Pom. Soc. 2007, 61, 140–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lyrene, P.M. Value of various taxa in breeding tetraploid blueberries in Florida. Euphytica 1997, 94, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norden, E.H.; Lyrene, P.M.; Chaparro, J.X. Ploidy, fertility, and phenotypes of F1 hybrids between tetraploid highbush blueberry cultivars and diploid Vaccinium elliottii. HortSci. 2020, 55, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, S.; Fujikawa, M.; Yamane, H.; Shirasawa, K.; Babiker, E.; Tao, R. Genomic insight into the developmental history of southern highbush blueberry populations. Heredity 2021, 126, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, W.H. Description of species: Vaccinium darrowi-Vaccinium hirsutum. Brittonia 1945, 5, 220–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Kloet, S.P. The taxononmy of Vaccinium and cyancoccus: a summation. Can. J. Bot. 1983, 61, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyrene, P.M. Florida native blueberries and their use in breeding. In Proceedings of the XI International Vaccinium Symposium 1180, 2016; pp. 9-16.

- Bassil, N.; Bidani, A.; Hummer, K.; Rowland, L.J.; Olmstead, J.; Lyrene, P.; Richards, C. Assessing genetic diversity of wild southeastern North American Vaccinium species using microsatellite markers. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2018, 65, 939–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.B. Contributions to the flora of Florida: 6, Vaccinium (Ericaceae). Castanea 1974, 191-205, doi:https://www.jstor.org/stable/4032784.

- Draper, A.; Mircetich, S.M.; Scott, D.H. Vaccinium clones resistant to Phytophthora cinnamomi. HortSci. 1971, 6, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballington, J.R. The role of interspecific hybridization in blueberry improvement. In Proceedings of the IX International Vaccinium Symposium 810, 2008; pp. 49-60.

- Lyrene, P.M.; Vorsa, N.; Ballington, J.R. Polyploidy and sexual polyploidization in the genus Vaccinium. Euphytica 2003, 133, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, A.; Stretch, A.W.; Scott, D.H. Two tetraploid sources of resistance for breeding blueberries resistant to phytophthora cinnamomi Rands. HortSci. 1972, 7, 266–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyrene, P.M.; Sherman, W.B. Horticultural characteristics of native Vaccinium darrowii, V. elliottii, V. fuscatum, and V. myrsinites in Alachua County, Florida. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1980, 105, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, G. Performance of southern highbush and rabbiteye blueberries on the Corindi Plateau NSW Australia. In Proceedings of the V International Symposium on Vaccinium Culture 346, 1993; pp. 141-146.

- Hummer, K.; Zee, F.; Strauss, A.; Keith, L.; Nishijima, W. Evergreen production of southern highbush blueberries in Hawai'i. Journal of the American Pomological Society 2007, 61, 188, doi:https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/evergreen-production-southernhighbush/docview/209773128/se-2?accountid=14537.

- Brazelton, C. World blueberry acreage & production. Folsom: USHBC 2013, 353, 880-886, doi:https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/aa0c/b8a984772846b938dbebf85b97d36e6b2afe.pdf.

- Harmon, P.F.; Liburd, O.E.; Dittmar, P.; Williamson, J.G.; Phillips, D. 2024 Florida blueberry integrated pest management guide, HS1156. UF/IFAS Extension 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.; Wilk, P.; Collins, D.; Robertson, D.; Daniel, R. Managing blueberry rust under an evergreen system. In Proceedings of the XI International Vaccinium Symposium 1180, 2016; pp. 105-110.

- Chu, Y.; Lyrene, P.M. Artificial induction of polyploidy in blueberry breeding: A review. HortScience 2025, 60, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeslee, A.F.; Avery, A.G. Methods of inducing doubling of chromosomes in plants. By treatment with colchicine. Journal of Heredity 1937, 28, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldy, R.G.; Lyrene, P.M. In vitro colchicine treatment of 4x blueberries, Vaccinium sp. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1984, 109, 336–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweikat, I.; Lyrene, P. Production and evaluation of a synthetic hexaploid in blueberry. TAG 1989, 77, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, R.; López, A.; Valenzuela, B.; D’Afonseca, V.; Gomez, A.; Arencibia, A.D. Organogenesis of plant tissues in colchicine allows selecting in field trial blueberry (Vaccinium spp. cv Duke) clones with commercial potential. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyrene, P.M.; Perry, J.L. Production and selection of blueberry polyploids in vitro. J. Heredity 1982, 73, 377–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Lyrene, P. In vitro induction of tetraploidy in Vaccinium darrowi, V. elliottii, and V. darrowi x V. elliottii with colchicine treatment. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1984, 109, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyrene, P.M. ‘Emerald’ southern highbush blueberry. HortSci. 2008, 43, 1606–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NeSmith, D.S. ‘Rebel’ southern highbush blueberry. HortSci. 2008, 43, 1592–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappai, F.; Garcia, A.; Cullen, R.; Davis, M.; Munoz, P.R. Advancements in low-chill blueberry Vaccinium corymbosum L. tissue culture practices. Plants 2020, 9, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.C. In vitro culture of lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium Ait.). Small Fruits Rev. 2004, 3, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y. High efficiency regeneration system from blueberry leaves and stems. Life 2023, 13, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade, R.; RAI, M.K. Colchicine, current advances and future prospects. Nusantara Bioscience 2010, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malawista, S.E. Colchicine: a common mechanism for its anti-inflammatory and anti-mitotic effects. Arthritis & Rheumatism 1968, 11, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, U.; Kundu, S.; Mandal, N. Artificial polyploidy in medicinal plants: advancement in the last two decades and impending prospects. J. Crop. Sci. Biotech. 2017, 20, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-w.; Zeng, W.-d.; Yan, H.-b. In vitro induction of tetraploids in cassava variety ‘Xinxuan 048’using colchicine. PCTOC 2017, 128, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haring, R.; Lyrene, P. Detection of colchicine induced tetraploids of Vaccinium arboreum with flow cytometry. In Proceedings of the IX International Vaccinium Symposium 810, 2008; pp. 133-138.

- Jarpa-Tauler, G.; Martínez-Barradas, V.; Romero-Romero, J.L.; Arce-Johnson, P. Autopolyploidization and in vitro regeneration of three highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) cultivars from leaves and microstems. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2024, 158, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, C.; Ishikawa, S.; Mii, M. In vitro induction of the amphiploid in interspecific hybrid of blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum× Vaccinium ashei) with colchicine treatment. Sci. Hort. 2009, 122, 375–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, E.; Biswal, A.; Ozias-Akins, P.; Chu, Y. Leaf organogenesis improves recovery of solid polyploid shoots from chimeric southern highbush blueberry. BioTech 2025, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Fleet, P.; Nevo, E.; Zhang, X.; Sun, G. Transcriptome analysis reveals plant response to colchicine treatment during on chromosome doubling. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 8503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liantinioti, G.; Argyris, A.A.; Protogerou, A.D.; Vlachoyiannopoulos, P. The Role of colchicine in the treatment of autoinflammatory diseases. Curr Pharm Des 2018, 24, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Xiang, P.; Zhang, S.; Wu, H.; Liu, W.; Yan, H. Delayed elimination in humans after ingestion of colchicine: Two fatal cases of colchicine poisoning. Journal of Forensic Sciences 2023, 68, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweikat, I.M.; Lyrene, P.M. Induced tetraploidy in a Vaccinium elliottii facilitates crossing with cultivated highbush blueberry. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 1991, 116, 1063–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podwyszynska, M.; Mynett, K.; Markiewicz, M.; Pluta, S.; Marasek-Ciolakowska, A. Chromosome doubling in genetically diverse bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) accessions and evaluation of tetraploids in terms of phenotype and ability to cross with highbush blueberry (V. corymbosum L.). Agron. 2021, 11, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangelli, F.; Pavese, V.; Vaia, G.; Lupo, M.; Bashir, M.A.; Cristofori, V.; Silvestri, C. In vitro polyploid induction of highbush blueberry through de novo shoot organogenesis. Plants 2022, 11, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aalders, L.; Hall, I. Note on aeration of colchicine solution in the treatment of germinating blueberry seeds to induce polyploidy. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1963, 43, 107–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, D.J.; Lyrene, P.M. Production and identification of colchicine-derived tetraploid Vaccinium darrowii and its use in breeding. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2009, 134, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyrene, P.M. First report of Vaccinium arboreum hybrids with cultivated highbush blueberry. HortSci. 2011, 46, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyrene, P.M. Phenotype and fertility of intersectional hybrids between tetraploid highbush blueberry and colchicine-treated Vaccinium stamineum. HortSci. 2016, 51, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, H.; Kunitake, H.; Yamasaki, M.; Komatsu, H.; Yoshioka, K. Production of intersectional hybrids between colchicine-induced tetraploid shashanbo (Vaccinium bracteatum) and highbush blueberry ‘Spartan’. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 2013, 138, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, W.-H.; Ho, W.-S. Polyploidization using colchicine in horticultural plants: A review. Sci. Hort. 2019, 246, 604–617. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, S.P.; Whitton, J. Polyploid incidence and evolution. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2000, 34, 401–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Martin, E.; Regalado, J.; Raghavan, L.; Encina, C. In vitro induction of autooctoploid asparagus genotypes. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2015, 121, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widoretno, W. In vitro induction and characterization of tetraploid Patchouli (Pogostemon cablin Benth.) plant. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2016, 125, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, J. Colchicine-induced tetraploidy in Dendrobium cariniferum and its effect on plantlet morphology, anatomy and genome size. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) 2021, 144, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corneillie, S.; De Storme, N.; Van Acker, R.; Fangel, J.U.; De Bruyne, M.; De Rycke, R.; Geelen, D.; Willats, W.G.T.; Vanholme, B.; Boerjan, W. Polyploidy affects plant growth and alters cell wall composition Plant Physiology 2018, 179, 74-87. [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, S.-I. Polyploidy and cellular mechanisms changing leaf size: comparison of diploid and autotetraploid populations in two species of Lolium. Annals of Botany 2005, 96, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, M.C.; Carvalho, C.R.; Clarindo, W.R. The polyploidy and its key role in plant breeding. Planta 2016, 243, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głowacka, K.; Jeżowski, S.; Kaczmarek, Z. In vitro induction of polyploidy by colchicine treatment of shoots and preliminary characterisation of induced polyploids in two Miscanthus species. Industrial Crops and Products 2010, 32, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, M.; Chen, R.; Jing, Y.; Wu, F.; Chen, Z.-H.; Tissue, D.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y. Guard cell and subsidiary cell sizes are key determinants for stomatal kinetics and drought adaptation in cereal crops. New Phytologist 2024, 242, 2479–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, A.M.; Woodward, F.I. The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature 2003, 424, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.-C.; Li, F.-M.; Zhang, T. Performance of wheat crops with different chromosome ploidy: root-sourced signals, drought tolerance, and yield performance. Planta 2006, 224, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Xiang, C.-B. Stomatal density and bio-water saving. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 2007, 49, 1435–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yan, H.; Li, L.; Yu, Y.; Si, H.; Hu, G.; Xiao, H.; Sun, Z. Photosynthesis-related characteristics of different ploidy rice plants. Zhongguo Shuidao Kexue 1999, 13, 157-160, doi:http://www.ricesci.cn/EN/Y1999/V13/I3/157.

- Leng, G.; Hall, J. Crop yield sensitivity of global major agricultural countries to droughts and the projected changes in the future. Science of the Total Environment 2019, 654, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).