1. Introduction

The cosmetics industry is undergoing exciting changes, just like many other sectors around the world. It’s blending age-old traditions, such as fermentation, with modern innovations like artificial intelligence, creating a vibrant new landscape for beauty products. Since prehistoric times, fermentation has been a key part of our culture, and now it’s stepping into the spotlight to play a crucial role in how we think about skincare and cosmetics.

It has been observed that fermentation produces compounds that have positive effects on the skin. The fermented ingredients possess several advantages that enhance the effectiveness of cosmetic products. For example, there is improved absorption because fermentation breaks down larger molecules into small adaptive ones [

1,

2,

3]. They have increased potency because the fermentation process amplifies the concentration of beneficial compounds, such as vitamins and antioxidants, enhancing their skin benefits [

4,

5]. They also have enhanced stability due to the production of natural preservatives like organic acids, alcohols and antibiotics during fermentation [

6]. Fermented ingredients can help balance the skin’s microbiome by promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria, which is crucial for maintaining a healthy skin barrier and preventing issues like acne and inflammation [

7]. Many fermented ingredients possess natural anti-inflammatory properties, making them suitable for sensitive and irritated skin [

8].

Integrating fermented minerals in cosmetics has notable advantages, which is nothing other than the enhanced bioavailability of essential nutrients. According to Majchrzak et al., the fermentation process significantly increases the effectiveness of raw materials used in cosmetics, thanks to the production of beneficial compounds such as amino acids, proteins, and antioxidants [

9]. Numerous ions are indispensable, while others exhibit supportive and auxiliary characteristics. They function within the skin, facilitating certain processes pertinent to the organ’s unique circumstances at the environmental interface. Skin bioenergetics, redox equilibrium, epidermal barrier integrity, and dermal remodelling are among the essential processes influenced by or utilising mineral elements [

10]. Skin regenerative processes and ageing can be favorably influenced by sufficient accessibility, distribution, and equilibrium of inorganic ions.[

10] Wu and colleagues demonstrated that

B. mucilaginosus enhances the breakdown of granite, gneisses, and sandstone by secreting organic acids, amino acids, polysaccharides, and other metabolites [

11]. They found that the contents of various organic acids, amino acids and polysaccharides in the fermentation liquid increased the concentration of the following oxides: SiO

2, Na

2O, P

2O

5, Fe

2O

3, Al

2O

3, CaO, K

2O, MgO and TiO

2 in the ferment broth. The background is, that the acids can react with mineral structures, leading to a more bioavailable form of these minerals [

11]. The complexity of microbial-mineral interactions during fermentation offers a biotechnological avenue for enhancing mineral recovery and improving nutrient cycling in both natural and engineered ecosystems.

Alginite, a mineral derived from the decomposition of algae, is emerging as a viable ingredient in the cosmetic industry, thanks to its unique properties and potential health benefits. Alginite has already been proven to have many unique benefits, such as enhancing crop production, good emulsification properties, and efficient probiotic effects when combined with LABs [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Recent studies have explored the effects of alginite, a mineral-rich substance, on probiotic fermentation and its potential applications in cosmetics, revealing promising results and new avenues for research. Alginite supplementation has consistently demonstrated a significant positive impact on probiotic bacterial growth and biomass production across various strains. Multiple measurement techniques, including cell dry weight (CDW), colony-forming units (CFU), and inline capacitance-based living cell sensors, have confirmed that alginite-supplemented cultures achieve 1.5-2 fold higher cell density compared to alginite-free cultures. Furthermore, specific growth rates and dry matter content during fermentation have shown marked increases, with the

Lactobacillus acidophilus study reporting an increase of the specific growth rate from 0,16 to 0,75 1/l and the dry matter content from 5,1 to 8.3 g/l in the presence of alginite [

20]. These findings have important implications for the efficient production of probiotic biomass, potentially leading to more cost-effective manufacturing processes. However, the relationship between enhanced growth and cosmetic efficacy presents a complex picture that requires further investigation. In the case of

Lactobacillus paracasei, with the hydration levels of 13.9% and 8.1%, respectively, the ferment filtrate without alginite performed better than those with alginite [

21]. However, in the case of L.

lactis, L. reuteri, and L. rhamnosus, there was no significant difference between the alginite and alginite-free ferment filtrates’ moisturising effect [

22]. On the other hand, the presence of alginite decreased the antioxidant impact in all cases except one (

L. acidophilus), which was unexpected because alginite has been shown to include fulvic and humic acids, which are known to have strong antioxidant properties [

22]. However, because humic acids may only be dissolved in alkaline media, that is why we did not particularly see their impact. While alginite-enriched ferment filtrates of

Limosilactobacillus reuteri and

Bifidobacterium adolescentis showed promise for use in tanning creams, pending skin toxicity tests [

22]. Despite this discrepancy, the potential for alginite-enriched probiotic ferments in cosmetic applications remains significant. These ingredients are noted for being sustainable, environmentally friendly, and highly effective, aligning with growing consumer demand for natural and eco-conscious skincare products. The combination of probiotics and alginite offers a novel approach to creating cosmetic ingredients that may provide multiple benefits beyond hydration.

The European Cosmetic Ingredient database (CosIng database) contains 621 entries for “lactobacillus,” 471 for “lactobacillus filtrate,” and 34 for “lactobacillus lysate.” The database contains several ingredients; yet, there is a scarcity of research publications regarding them in the literature. Now, LABs are registered as moisturizer, humectants, conditioners for skin and/or hair, and some even possess antioxidant and bleaching (skin whitening) characteristics. Consequently, we initiated a systematic investigation for LAB based filtrates [

22] and lysates alone, and in a combination with the prospectiv alginite-mineral.

This study evaluated the effectiveness of fermented lysate derived from

Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and

Bifidobacterium adolescentis as cosmetic ingredients. In the CosIng database, the indicated Lactobacillus ferment lysates mostly have a moisturising effect. We anticipate favourable moisturization scores from the lysates, although they are unlikely to surpass those of the filtrates, because filtrates also contain lactic acid providing well moisturizing effect [

22]. Alginite may absorb and retain water, subsequently releasing it to plants, and we anticipate analogous outcomes for the skin. We evaluated the skin moisturising effects, antioxidant activity via DPPH and CUPRAC methodologies, and skin whitening potential by the mushroom tyrosinase assay, similarly as previously conducted with filtrates. This paper details the implementation of the CUPRAC technique. This experiment is generally conducted at a neutral pH, enhancing its relevance to physiological settings. Conversely, the DPPH assay is typically conducted in organic solvents or alcohol-water combinations, which may not consistently represent physiological circumstances. Consequently, it exhibits more selectivity for lipophilic antioxidants due to its solubility in organic solvents; conversely, the CUPRAC method is responsive to both hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants.

According to our knowledge, no one has reported research about the cosmetic usage of LABs ferment lysate supplemented with alginite mineral yet.

2. Materials and Methods

The following strains were used: Lactobacillus rhamnosus (NCAIM B.02274) in MRS, Lactobacillus acidophilus (NCAIM B.02085) in MRS, and Bifidobacterium adolescentis (NCAIM B.01822) in Bifidobacterium medium.

De Man, Rogosa and Sharp (MRS) medium contained the following: Peptone 10 g/L; Meat extract 10 g/L; Yeast extract 5.0 g/L; Glucose 20 g/L; K2HPO4 2.0 g/L; Sodium-acetate 2.0 g/L; Ammonium-citrate 2.0 g/L; MgSO4 × 7H2O 0.2 g/L; MnSO4 × H2O 0.05 g/L; Tween-80 1.08 g/L.

Bifidobacterium medium: Peptone from casein 10 g/L; Yeast extract 5.0 g/L; Meat extract 5.0 g/L; Soy peptone 5.0 g/L; Glucose 10 g/L; K2HPO4 2.0 g/L; MgSO4 × 7 H2O 0.2 g/L; MnSO4 × H2O 0.05 g/L; Tween-80 1.0 mL; NaCl 5.0 g/L; Cystein-HCl × H2O 0.5 g/L; Resazurin (25 mg/100 mL) 4.0 mL; Trace elements solution 40 mL.

Trace elements solution: 1000 mL distilled water: CaCl2 × 2H2O 0.25 g; MgSO4 × 7H2O 0.50 g; K2HPO4 1.00 g; KH2PO4 1.00 g; NaHCO3 10.00 g; NaCl 2.00 g.

In the case of the alginite-based fermentations, each medium was supplemented with powdered alginite mineral (Gérce, Hungary) 10.0 g/L if necessary. The used alginite mineral had an average 20 micron particle size. The alginite used contained, according to Kádár et al. [

23] 4 4% moisture, 15% CaCO3 and 4.6% organic matter. Total-N was 0.15%, K 63 mg/kg, Al-K

2O 386 mg/kg, Al-P

2O

5 216 mg/kg. The alginite used contained approximately 5% elemental Ca; 3.6% Al; 2.9% Fe; 1.9% Mg; 0.82% K; 0.15% P; 0.12% S. Aqua regia soluble content: Ca 49942 mg/kg, Al 36026 mg/kg, Fe 28501 mg/kg, Mg 19188 mg/kg, K 8166 mg/kg, P 1501 mg/kg, S 1237 mg/kg, Mn 587 mg/kg, Na 454 mg/kg, Sr 419 mg/kg, Ba 281 mg/kg, Ni 75,0 mg/kg, Zn 65,8 mg/kg, Cr 63,9 mg/kg, B 26,8 mg/kg, Cu 19,2 mg/kg, Co 15,9 mg/kg, Pb 9,75 mg/kg, As 8,84 mg/kg, Sn 2,84 mg/kg, Mo 1,86 mg/kg, Se 1,02 mg/kg, Cd 0,12 mg/kg.

The fermentations were carried out in a 1 L benchtop bioreactor with a working volume of 0.8 L (Biostat Q fermenter, B. Braun Biotech International, Melsungen, Germany) and a 5% v/v inoculum. For production, the temperature was adjusted to 37 °C with an agitation speed of 300 rpm. The pH was controlled by 25% H3PO4 and 25% NaOH.

After the fermentations, each broth was centrifuged (6000 rpm, Janetzki K23D centrifuge)to separate the supernatant and cell-biomass (also containing alginite content of the broth). The cells (with alginite) were stored in a freezer at - 20°C. The lysates were made by the one-cycle freeze-thaw method.

2.2. Skin Moisturising Measurement

As we previously reported, the ferment filtrates’ short-term/immediate hydration effect was determined using a dermatoscope [

21]. We marked a one-square-centimetre area on the forearm three times and pipetted 20 microliters of cell-free ferment filtrate. After 5 min, we wiped it with a dry hand towel and then measured the hydration of that part of our skin at given intervals with the Corneometer (capacitive) Multi Dermascope MDS 800 (Courage-Khazaka)) sensor. To have a basis for comparison, we measured the level of hydration of the skin before the measurement and subtracted that value from each measured value. Time curves in general jumped after start, and following exponential decay, stabilised at the end of the measurements. The difference between initial and final measured data indicated either the moisturising capability of the tested filtrate or its drying capability (if any).

2.3. Antioxidant Capacity Measurement

2.3.1. Procedure of DPPH Method

The antioxidant capacity of the ferment lysate was determined with the 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH, 97%) scavenging method [

22]. For the calibration, L-ascorbic acid (AscH2, 99,82%) was used in UV/HPLC grade methanol, which was purchased from Sigma Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fresh stock solutions were prepared before each analysis. The spectrophotometric measurements were performed in a Camspec M501 single beam spectrophotometer with 1 cm glass cuvettes at 517 nm.

For antioxidant activity determination, oxidation of DPPH·-H to DPPH was followed spectrophotometrically, resulting in less oxidised product if antioxidant activity is present, using Ascorbic acid (AscH2) as reference. For that, a 150 µmol/L methanolic DPPH solution was prepared. For DPPH-H, the methanolic solution was prepared with DPPH· and AscH2, both at 150 µmol/L (100% excess of AscH2), protecting the reaction from light for 0.5 h. The DPPH assay was performed by adding constant aliquots of 1.5 mL of an AscH2 methanolic solution (300, 150, 75.0, 37.5 and 18.75 mmol/L) to 1.5 mL of a DPPH solution (150 µmol/L in methanol). The same procedure was applied to the ferment lysate, although there were some modifications. Approximately 1.0 g of the ferment lysate sample was measured, and the liquid volume was adjusted to 4.5 ml (with distilled water), followed by homogenization using vortexing. The fermentation lysates were diluted twice with methanol, and they were used hereafter in different fold dilutions (2, 4, 8, 16 and 32). The negative control was prepared by 1.5 mL of methanol and 1.5 mL of 150 µmol/L DPPH in methanol. All the reactions were kept in the dark for 30 min (at 25°C) until measurements. After the reaction, the precipitated substances were centrifuged. All samples and negative controls were measured in triplicate. The following equation calculated the percentage DPPH scavenging activity (AbsNC—average absorbance of negative control, Abssample—average absorbance of sample):

(1)

DPPHscav.(%) was plotted versus concentration and linear regression was used to determine IC50 values.

2.3.2. Procedure of the CUPRAC Method

Preparation of CUPRAC assay solutions: 0.01 M Cu+2 is prepared by dissolving 0.4262 g CuCl2 · 2H2O in water and diluting to 250 ml (in a volumetric flask at room temperature). Ammonium acetate (NH4Ac) buffer at pH 7.0, 1.0 M, is prepared by dissolving 19.27 g NH4Ac in water and diluting to 250 ml. Neocuproine (Nc) solution, 7.5 * 10-3 M, is prepared daily by dissolving 0.039 g Nc in 96% ethanol and diluting to 25 ml with ethanol.

Approximately 1.0 g of the liquid ferment lysate samples was measured, and the liquid volume was adjusted to 4.5 ml, followed by homogenization using vortexing. 2.25 ml of the previously prepared solution was measured, followed by the addition of 0.75 ml of 0.01 M CuCl2 solution, 0.75 ml of 1.0 M NH4Ac solution, and 0.75 ml of 7.5 x 10-3 M Neocuprione solution. The resulting 4.5 ml solution was allowed to stand for 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by centrifugation (5 minutes at 6500 rpm) to eliminate biomass particles that could interfere with the measurement. The absorbance at 450 nm (A450) was measured relative to a reagent blank. The employed UV-Vis spectrophotometer was Camspec M501 single beam spectrophotometer. All samples and negative controls were measured in triplicate. The following equation calculated the percentage CUPRAC activity (AbsNC - average absorbance of negative control, Abssample - average absorbance of sample, Absblanc – average absorbance of blanc):

(2)

Cu[II.](%) was plotted versus concentration and linear regression was used to determine IC50 values.

2.4. Mushroom Tyrosinase Inhibition

The ferments’ filtrates’ tyrosinase inhibitory activity was evaluated to determine the filtrates’ skin-whitening activity using mushroom tyrosinase as a model enzyme (human tyrosinase takes part in pigment (melanine) formation, thus its inhibition results in more white skin) and L-DOPA (98%). The method reported by Toshiya M. [

24] was employed with some modifications. Briefly, the cuvettes were designated for A (negative control), B (blank of negative control), C (sample), and D (blank of the sample), which contained the following reaction mixtures: A, 750 µL of a 1/15 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) and 200 µL L-DOPA (10 mM in the same buffer with 5% DMSO); B, 950 µL of the same buffer; C, 350 µL of the same buffer, 200 µL L-DOPA (in the same solution), and 400 µL of an appropriate amount of the sample; D, 550 µL of the same buffer and 400 µL of the same amount of the sample solution. B and C cuvettes for all samples were determined in triplicates. The contents of each were well mixed, and 50 µL of tyrosinase (50 units/mL in the same buffer) was added. After incubation at room temperature (23 °C) for 10 min, each cuvette’s absorbance at 475 nm was measured in Pharmacia LKB-Ultrospec Plus spectrophotometer. The following equation calculated the percentage inhibition of the tyrosinase activity:

(3)

The reference compound used for calibration was kojic acid (50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.125 µg/ml).

3. Results

We have performed the three primary evaluations employed to assess the potency of individual skincare products. The three measurements include the assessment of the moisturising impact, the analysis of antioxidant activity employing the DPPH and CUPRAC methods and the evaluation of sun protection efficacy via the mushroom tyrosinase method.

3.1. Skin Moisture Effect Determination

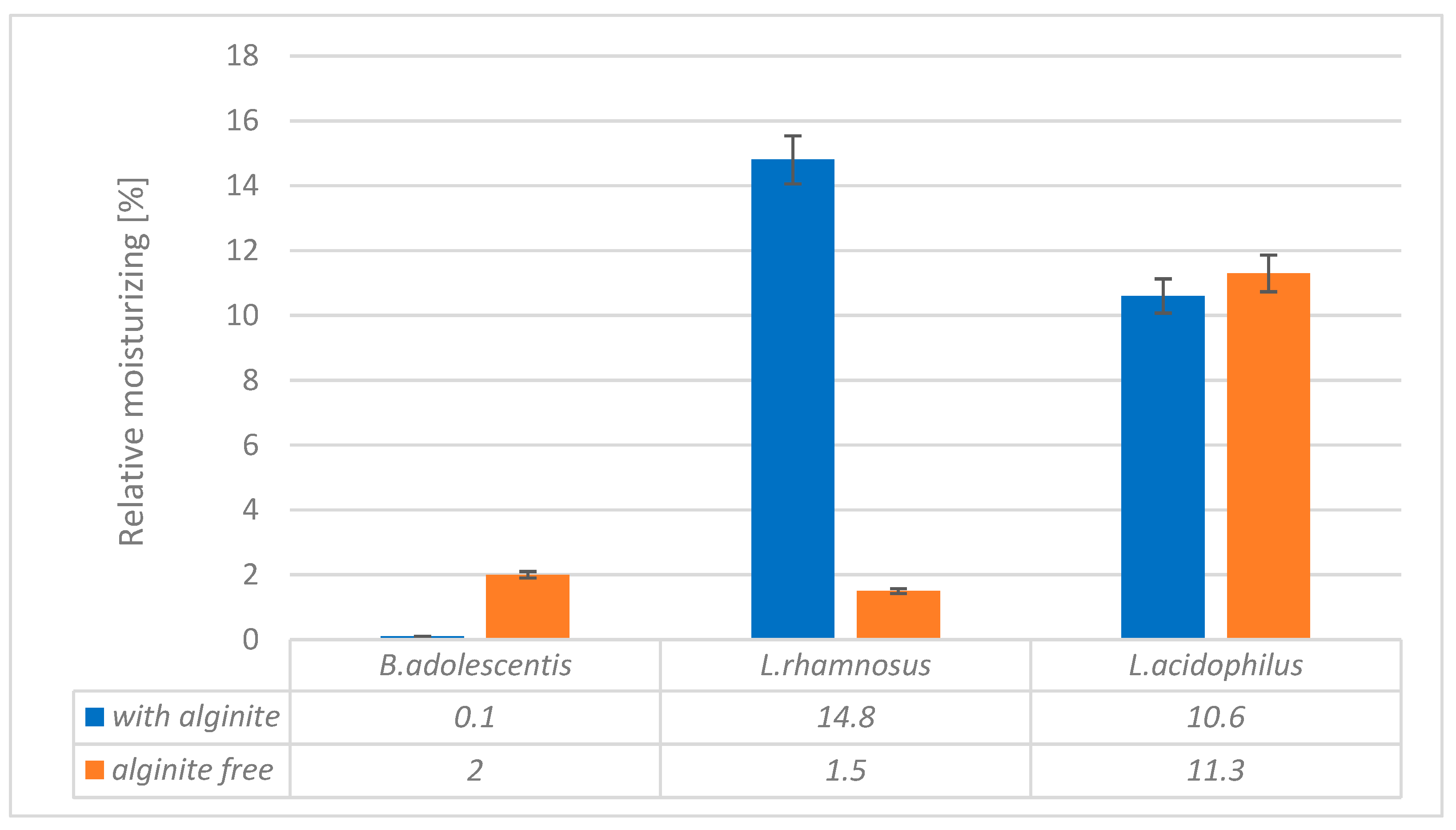

Our study investigated the moisturising effects of three probiotic strains (Bifidobacterium adolescentis, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and Lactobacillus acidophilus) and their combinations with alginite. The pure probiotic biomasses showed varying degrees of moisturising effects, with L. acidophilus exhibiting the highest effect (11.3), followed by B. adolescentis (2.0) and L. rhamnosus (1.5) (

Figure 1). When combined with alginite, the moisturising effects changed notably. The L. rhamnosus-alginite combination (LR-alginite) demonstrated the most substantial moisturising effect (14.8), showing a significant increase from its pure probiotic form. The L. acidophilus-alginite combination (LA-alginite) maintained a strong moisturising effect (10.6), similar to its pure form. Interestingly, the B. adolescentis-alginite combination (BA-alginite) showed a marked decrease in moisturising effect (0.1) compared to its pure form.

These findings suggest that the combination of probiotics with alginite can significantly alter their moisturising properties, with the effect varying depending on the specific probiotic strain. The L. rhamnosus-alginite combination, in particular, shows promising potential for moisturising applications.

3.2. The Antioxidant Capacity

The antioxidant capacity of three probiotic bacterial strains’ ferment filtrate (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, and Bifidobacterium adolescentis) was evaluated using both CUPRAC and DPPH methods when either alginite was applied or wasn’t during the fermentation.

CUPRAC method results revealed significant variations in antioxidant capacity.

L. acidophilus alginite ferment filtrate showed a marked increase in antioxidant capacity compared to alginite-free filtrates, from 24.9 to 5.2, representing a 79.1% increase (

Table 1., the lower IC

50 is the better result).

B. adolescentis exhibited a moderate increase, from 7.5 to 5.8, a 22.7% improvement. In contrast,

L. rhamnosus demonstrated a slight decrease, from 8.3 to 10.3, indicating a 24.1% reduction in antioxidant capacity.

DPPH method results (

Table 2.) presented a different pattern.

L. acidophilus displayed a substantial decrease in antioxidant capacity with alginite, from 4.51 to 2.46, which means a 45.5% reduction. Similarly,

B. adolescentis showed a notable decrease, from 3.01 to 1.42, representing a 52.8% decline.

L. rhamnosus, however, remained almost unchanged, with values shifting marginally from 6.01 to 6.02, a mere 0.2% increase.

These findings highlight the complex interaction between alginite and bacterial antioxidant systems. The contrasting results between CUPRAC and DPPH methods, particularly for L. acidophilus, suggest that alginite may influence different antioxidant mechanisms within the bacterial cells. L. rhamnosus demonstrated the most consistent results across both methods, indicating a potentially more stable antioxidant system in the presence of alginite.

The divergent responses of the three bacterial strains to alginite emphasize the species-specific nature of antioxidant capacity modulation. This variability underscores the importance of strain selection in probiotic formulations, especially when considering potential synergistic effects with additives like alginite.

Furthermore, the discrepancies between CUPRAC and DPPH results highlight the necessity of employing multiple analytical methods when assessing antioxidant capacity, as different assays may capture distinct aspects of the complex antioxidant systems present in probiotic bacteria. These comprehensive findings provide valuable insights into the intricate relationship between alginite and the antioxidant properties of probiotic strains, paving the way for more targeted research and applications in the field of probiotics and functional foods.

The enhanced antioxidant potential of the probiotic-alginite combinations, particularly BA-alginite and LA-alginite, may have important implications for potential applications in various industries, such as cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and food, where strong antioxidant activity is desirable.

3.3. Mushroom Tyrosinase Inhibition

The third important and studied cosmetic parameter is the mushroom tyrosinase inhibition measurement. This is a common method used to assess the activity of tyrosinase, an enzyme that plays a crucial role in melanin biosynthesis.

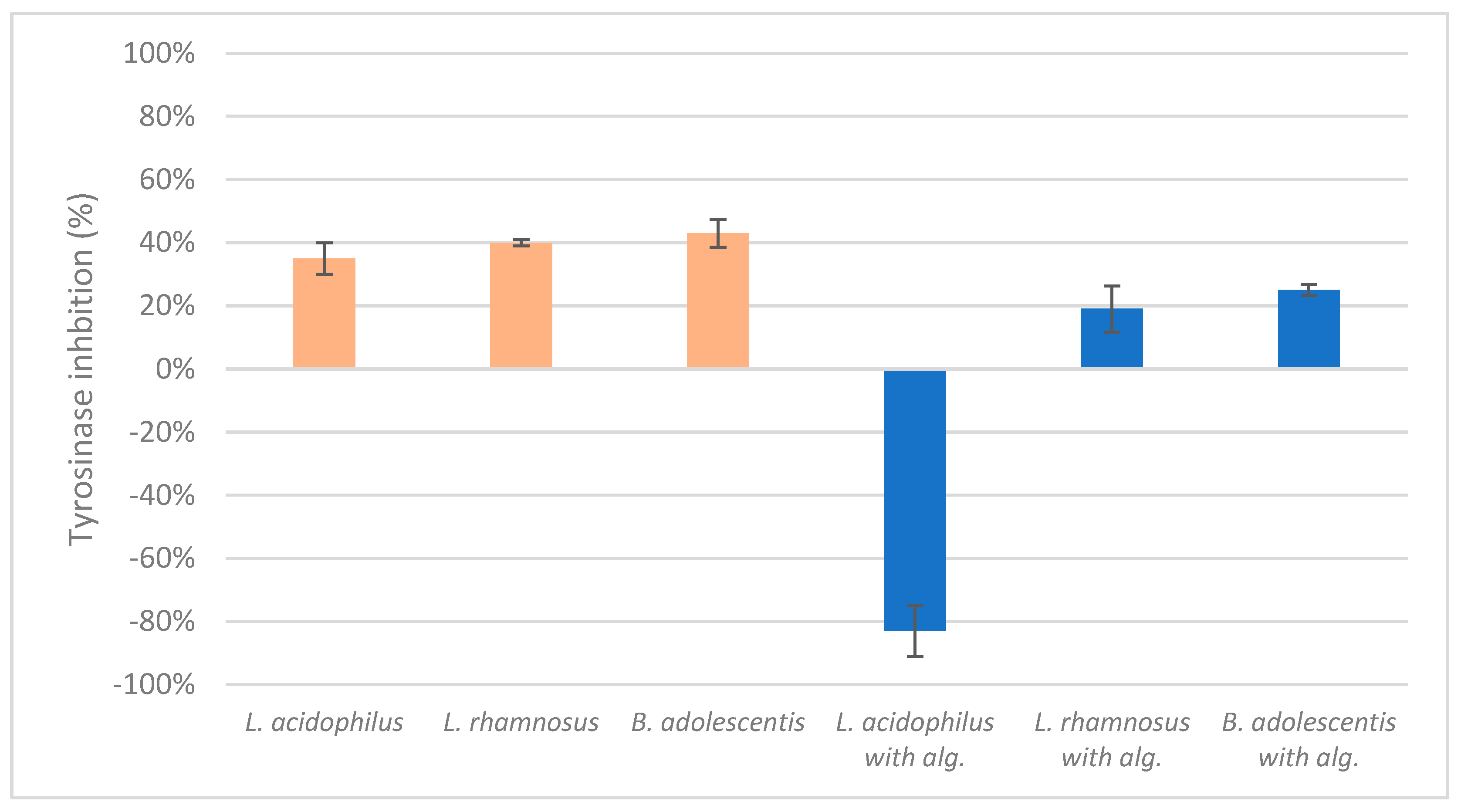

The results of the mushroom tyrosinase inhibition measurements indicated a lack of significant positive or negative effects on inhibition, with the exception of the lysate of

L. acidophilus combined with alginite, which enhanced enzyme activity (

Figure 2.). This finding aligns with our previous study, where the ferment filtrates of

L. reuteri, B. adolescentis, and

L. acidophilus with alginite also demonstrated a tanning effect [

22].

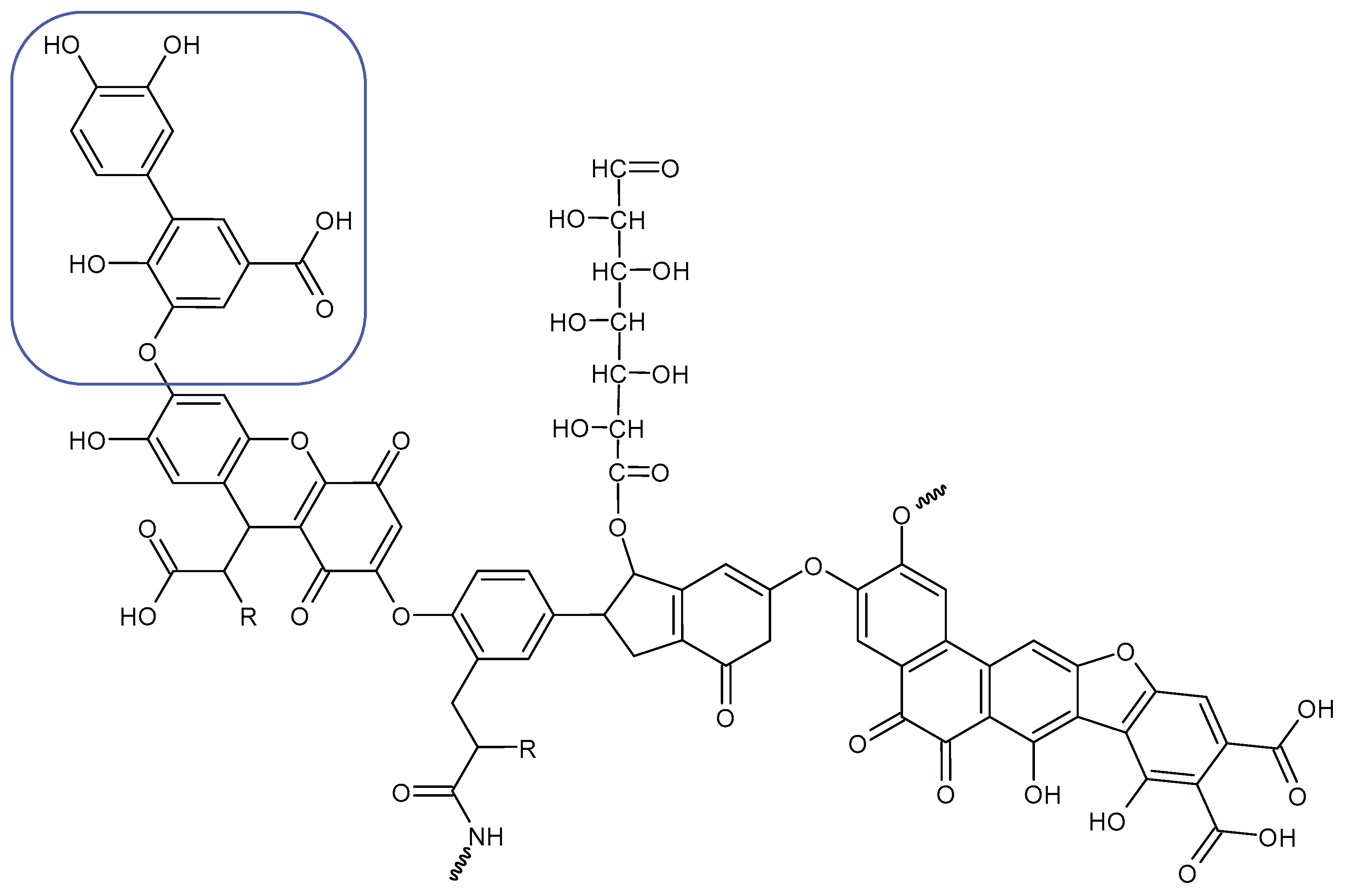

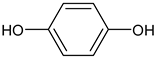

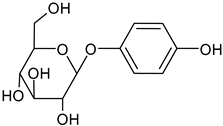

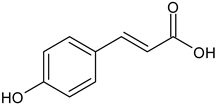

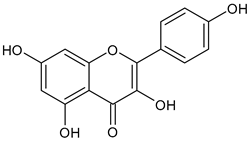

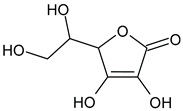

In the mushroom tyrosinase inhibition measurement, none of the samples reached the 50% inhibition level of the tyrosinase enzyme. The known tyrosinase inhibitors commonly have phenolic compounds with more than one heteroatom, which are usually oxygen in the form of oxo, hydroxyl and ether. In

Table 3., we listed some known tyrosinase inhibitors, for example.

Alginite contains humic and fulvic acids. In the humic acids (

Figure 3), we can find a group whose chemical structure is similar to the mushroom tyrosinase inhibitors. In the blue bracket, a catechol is linked to a PHBA (para-hydroxybenzoic acid). So we could assume some tyrosinase enzyme inhibitor activity of alginite. However, the inhibitors and the smaller humic substances (which are able to bind to the enzyme) are polar due to the many hydroxyl and oxo groups, thus they are rather distributed into the aqueos phase (i.e. in ferment filtrate), and none in the ferment lysate. Unfortunately, not any further tyrosinase inhibitors were found.

Thess findings meet with our previous study, where we investigated the LABs’ ferment filtrates. The following results were obtained: the highest achieved inhibition of tyrosinase

L. reuteri and

B. adolescentis alginite-free filtrates had a value of 88% and 69%, respectively. However, the alginite-based ferment filtrates for the same strains reached values of −94% and −135% at the same dilution [

22].

To summarize, the alginite based ferment filtrates enhanced the activity of the mushroom tyrosinase, which leads to the tanning effect on the skin, as indicated by negative inhibition values, while alginate ferment lysate did not had any skin whitening effect i.e .tyrosinase inhibition.

4. Discussion

Our study on the effects of probiotic strains and their combinations with alginite has yielded valuable insights into their potential applications in skincare and functional foods. The research focused on three key aspects: moisturizing effects, antioxidant activity, and sun protection efficacy.

In terms of moisturizing properties, we observed significant variations among the probiotic strains and their alginite combinations. Alginite by itself has a skin-drying effect, but the combination of Lactobacillus rhamnosus’s ferment filtrate with alginite in fermentation showed the most significant moisturising effect, even outperforming the strong moisturising properties of pure Lactobacillus acidophilus. This finding suggests a synergistic interaction between L. rhamnosus and alginite, which could be particularly beneficial for skincare applications.

The investigation of antioxidant activity demonstrated intricate interactions between the probiotic strains and alginite. The IC50 of antioxidant capacity values were in different range depending on the employed methods (CUPRAC or DPPH), but the ratio of tested samples are similar: the disparity between the L. acidophilus lysate with and without alginite was much greater in the CUPRAC assessment than in the DPPH measurement. In both instances, the alginite supplement exhibited superior antioxidant capacity compared to the alginite-free. The lysates of L. rhamnosus alginite and alginite-free produced comparable outcomes in the CUPRAC assay, while alginite-supplemented and alginite-free lysates showed identical results, also with the DPPH assay. The B. adolescentis lysate combined with alginite exhibited the best antioxidant result in the DPPH assay, and also the alginite one reached better antioxidant capacity in measurement of CUPRAC.

Contrary to our initial expectations, the sun protection efficacy tests yielded no significant tyrosinase inhibition across all samples. L. acidophilus with alginite was an exception because it went negative and reached -83% in mushroom tyrosinase inhibition i.e. activation. We have previously experienced similar results, only then alginite filtrates of probiotic strains (L.reuteri, B. adolescentis and L.acidophilus) showed similar skin tanning properties. Returning to the rest, we hypothesize that this lack of effect may be due to the separation of potential inhibitors during the centrifugation, with active compounds likely remaining in the filtrates rather than the biomass based on their structure and water solubility.

These findings collectively emphasise the strain-specific nature of probiotic-alginite interactions and their effects on various skincare-related properties. The study underscores the potential of certain probiotic-alginite combinations, particularly for moisturizing and antioxidant applications. However, it also highlights the need for careful consideration of strain selection and processing methods when developing probiotic-based products.

Moving forward, further research is warranted to optimize probiotic-alginite combinations for specific applications and to fully understand the mechanisms underlying their biological activities. This study lays a foundation for future investigations into the use of probiotics and alginite in skincare and functional food industries, opening up new possibilities for innovative product development.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we examined the cosmetic impacts of three probiotic lactic acid-producing bacteria (L. acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, and B. adolescentis) fermented lysates, both with and without alginite. The alginite enhanced the efficacy of probiotic ferment lysates as cosmetic additives. L. acidophilus samples demonstrated effective skin hydration; however, the alginite-based samples exhibited superior antioxidant activity, particularly in the CUPRAC assay. Furthermore, it demonstrated skin tanning properties in the mushroom tyrosinase assays. The L. rhamnosus alginite-supplemented ferment lysate achieved the highest skin hydration result at 14.8%, whereas the alginite-free variant yielded 1.5%. B. adolescentis exhibits strong antioxidant capacity (alginite based was better in all cases); however, it is ineffective in skin moisturization and mushroom tyrosinase inhibition.

According to our findings L. acidophilus alginite supplemented ferment lysate is app licable as moisturizer, antioxidant and skin tanner. L. rhamnosus lysate with alginite could be applied as a moisturizer.

Declarations

Author contributions: P.T. methodology, investigation, formal analysis, visualisation, writing original draft; Á.N conceptualisation, writing – review &editing, supervision, validation, project administration.

Funding

This research received no external funding. APC was funded by MÉL Biotech K+F Kft (Budapest, Hungary).

Ethics Approval

No animal and human experiments are involved; therefore, N/A.

Data Availability

Authors confirm that all data are involved in the manuscript; further data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgements

The used Alginite sample was a kind gift of Alginit Kft, Hungary.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Juliano, C.C.A.; Magrini, G.A. A Radish Root Ferment Filtrate for Cosmetic Preservation: A Study of Efficacy of Kopraphinol. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-F.; Huang, C.-C.; Lee, M.-Y.; Lin, Y.-S. Fermented Broth in Tyrosinase- and Melanogenesis Inhibition. Molecules 2014, 19, 13122–13135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, J.; Jeong, K.J. Engineering of Leuconostoc citreum for Efficient Bioconversion of Soy Isoflavone Glycosides to Their Aglycone Forms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hati, S.; Patel, M.; Mishra, B.K.; Das, S. Short-chain fatty acid and vitamin production potentials of Lactobacillus isolated from fermented foods of Khasi Tribes, Meghalaya, India. Ann. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Teng, J.; Lyu, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, M. Enhanced Antioxidant Activity for Apple Juice Fermented with Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC14917. Molecules 2019, 24, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duhan, J.S.; Nehra, K.; Gahlawat, S.K.; Saharan, P.; Surekha, D. Bacteriocins from Lactic Acid Bacteria. In: Salar, R., Gahlawat, S., Siwach, P., Duhan, J. (eds) Biotech.: Prosp. and Appl. Springer, New Delhi. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, X.; Cui, X.; Ding, K.; Wang, S.; Han, C. Application and mechanism of probiotics in skin care: A review. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.-Q.; Zhang, X.-H.; Gao, H.-Q.; Huang, L.-Y.; Ye, J.-J.; Ye, J.-H.; Lu, J.-L.; Ma, S.-C.; Liang, Y.-R. Green Tea Catechins and Skin Health. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrzak, W.; Motyl, I.; Śmigielski, K. Biological and Cosmetical Importance of Fermented Raw Materials: An Overview. Molecules 2022, 27, 4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haftek, M.; Abdayem, R.; Guyonnet-Debersac, P. Skin Minerals: Key Roles of Inorganic Elements in Skin Physiological Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q. PRELIMINARY STUDY ON THE ROCK WEATHERING EFFECT OF BACILLUS MUCILAGINOSUS. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 13297–13309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G. Solti, Az alginit. Budapest, A Magyar Áll Föld Int (alkalmi kiadványa). 1987; ISBN 963 671 073 2.

- Cukor, J.; Linhart, L.; Vacek, Z.; Baláš, M.; Linda, R. The effects of Alginite fertilization on selected tree species seedlings performance on afforested agricultural lands. For. J. 2017, 63, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tužinský, M.; Kupka, I.; Podrázský, V.; Prknová, H. Influence of the mineral rock alginite on survival rate and re-growth of selected tree species on agricultural land. J. For. Sci. 2015, 61, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hippmann, S.; Ahmed, S.S.; Fröhlich, P.; Bertau, M. Demulsification of water/crude oil emulsion using natural rock Alginite. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 553, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.S.; Hippmann, S.; Roode-Gutzmer, Q.I.; Fröhlich, P.; Bertau, M. Alginite rock as effective demulsifier to separate water from various crude oil emulsions. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 611, 125830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlubeňová, K.; Mudroňová, D.; Nemcová, R.; Gancarčíková, S.; Maďar, M.; Sciranková, Ľ. The Efect of Probiotic Lactobacilli and Alginite on the Cellular Immune Response in Salmonella Infected Mice. Folia Veter- 2017, 61, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strompfová, V.; Kubašová, I.; Farbáková, J.; Maďari, A.; Gancarčíková, S.; Mudroňová, D.; Lauková, A. Evaluation of Probiotic Lactobacillus fermentum CCM 7421 Administration with Alginite in Dogs. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2017, 10, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancarčíková, S.; Nemcová, R.; Popper, M.; Hrčková, G.; Sciranková, Ľ.; Maďar, M.; Mudroňová, D.; Vilček, Š.; Žitňan, R. The Influence of Feed-Supplementation with Probiotic Strain Lactobacillus reuteri CCM 8617 and Alginite on Intestinal Microenvironment of SPF Mice Infected with Salmonella Typhimurium CCM 7205. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2018, 11, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, P.; Németh, Á. Exploring the Impact of Alginite Mineral on Lactic Acid Bacteria. Preprints 2025, 2025021082. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202502. 1082. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, P.; Németh, Á. Investigations into the Usage of the Mineral Alginite Fermented with Lactobacillus Paracasei for Cosmetic Purposes. Hung. J. Ind. Chem. 2022, 50, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, P.; Németh, Á. Investigation and Characterisation of New Eco-Friendly Cosmetic Ingredients Based on Probiotic Bacteria Ferment Filtrates in Combination with Alginite Mineral. Processes 2022, 10, 2672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kádár, I.; Ragályi, P.; Murányi, A.; Radimszky, L.; Gajdó, A. Effect of Gérce alginit on the fertility of an acid sandy soil. 64. [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Yamashita, D.; Takeda, Y.; Yonemori, S. Screening for Tyrosinase Inhibitors among Extracts of Seashore Plants and Identification of Potent Inhibitors fromGarcinia subelliptica. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005, 69, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillaiyar, T.; Manickam, M.; Jung, S.-H. Downregulation of melanogenesis: drug discovery and therapeutic options. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.; Ashraf, Z.; Abbas, Q.; Raza, H.; Seo, S.-Y. Exploration of Novel Human Tyrosinase Inhibitors by Molecular Modeling, Docking and Simulation Studies. Interdiscip. Sci. Comput. Life Sci. 2018, 10, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, T.; Gerwat, W.; Batzer, J.; Eggers, K.; Scherner, C.; Wenck, H.; Stäb, F.; Hearing, V.J.; Röhm, K.H.; Kolbe, L. Inhibition of human tyrosinase requires molecular motifs distinctively different from mushroom tyrosinase. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 138, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, Z.; Rafiq, M.; Seo, S.-Y.; Babar, M.M.; Zaidi, N.-U.S. Design, synthesis and bioevaluation of novel umbelliferone analogues as potential mushroom tyrosinase inhibitors. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2015, 30, 874–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolbe, L.; Mann, T.; Gerwat, W.; Batzer, J.; Ahlheit, S.; Scherner, C.; Wenck, H.; Stäb, F. 4-n-butylresorcinol, a highly effective tyrosinase inhibitor for the topical treatment of hyperpigmentation. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2012, 27, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, H.S.; Ghimeray, A.K.; Yoo, D.S.; Ahn, S.M.; Kwon, S.S.; Lee, K.H.; Cho, D.H.; Cho, J.Y. Kaempferol and Kaempferol Rhamnosides with Depigmenting and Anti-Inflammatory Properties. Molecules 2011, 16, 3338–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokinsee, D.; Shank, L.; Lee, V.S.; Nimmanpipug, P. Estimation of Inhibitory Effect against Tyrosinase Activity through Homology Modeling and Molecular Docking. Enzym. Res. 2015, 2015, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).