Submitted:

20 June 2025

Posted:

24 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strains

2.2. In Silico Analysis

2.3. Phylogeny of C. auris Putative Yapsins

2.4. Prediction of the Secondary and Tertiary Structure of Putative Yapsins

2.5. Molecular Docking of C. auris Putative Yps1 and Yps7

2.6. Evaluation of C. auris Growth Under Different Conditions

2.7. Expression of YPS1 and YPS7 Genes by RT-qPCR

2.8. Effect of Pepstatin A on the Microscopic Morphology of C. auris

3. Results

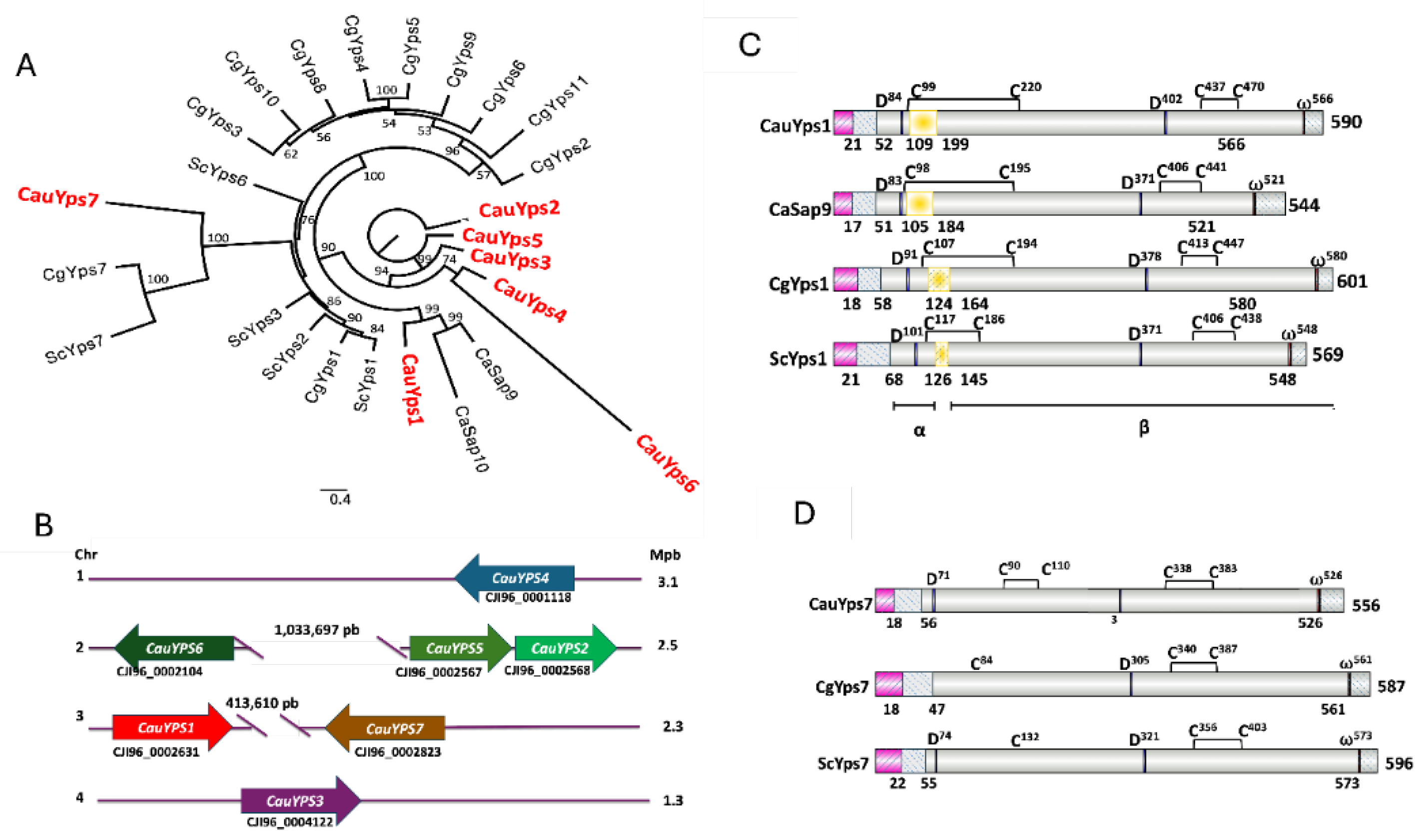

3.1. C. auris Presents a Family of YPS Multigene Encoding Putative Yapsins

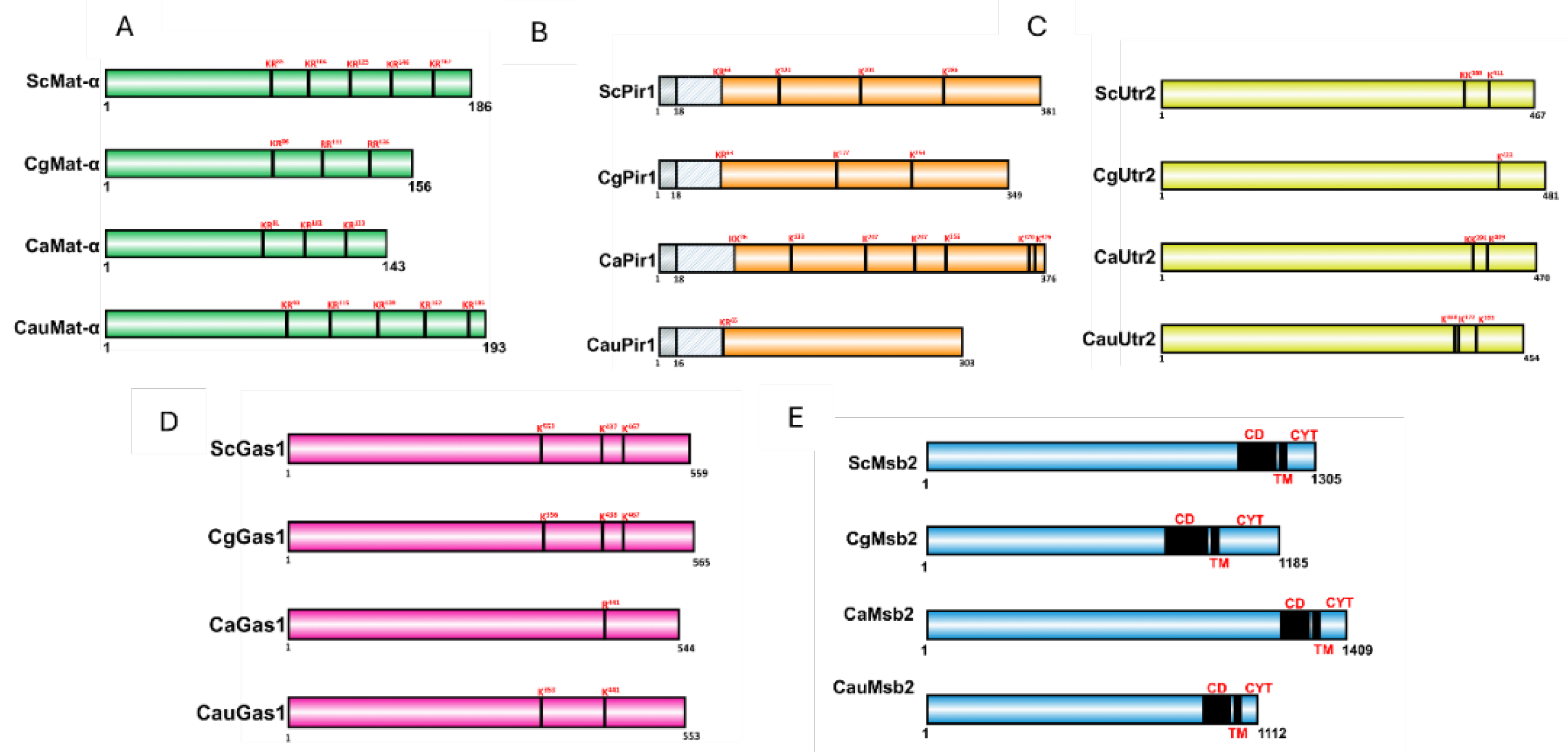

3.2. Yps1 and Yps7 of C. auris Are Orthologous to the Yapsins of C. albicans, C. glabrata (Nakaesomyces glabratus), and S. cerevisiae

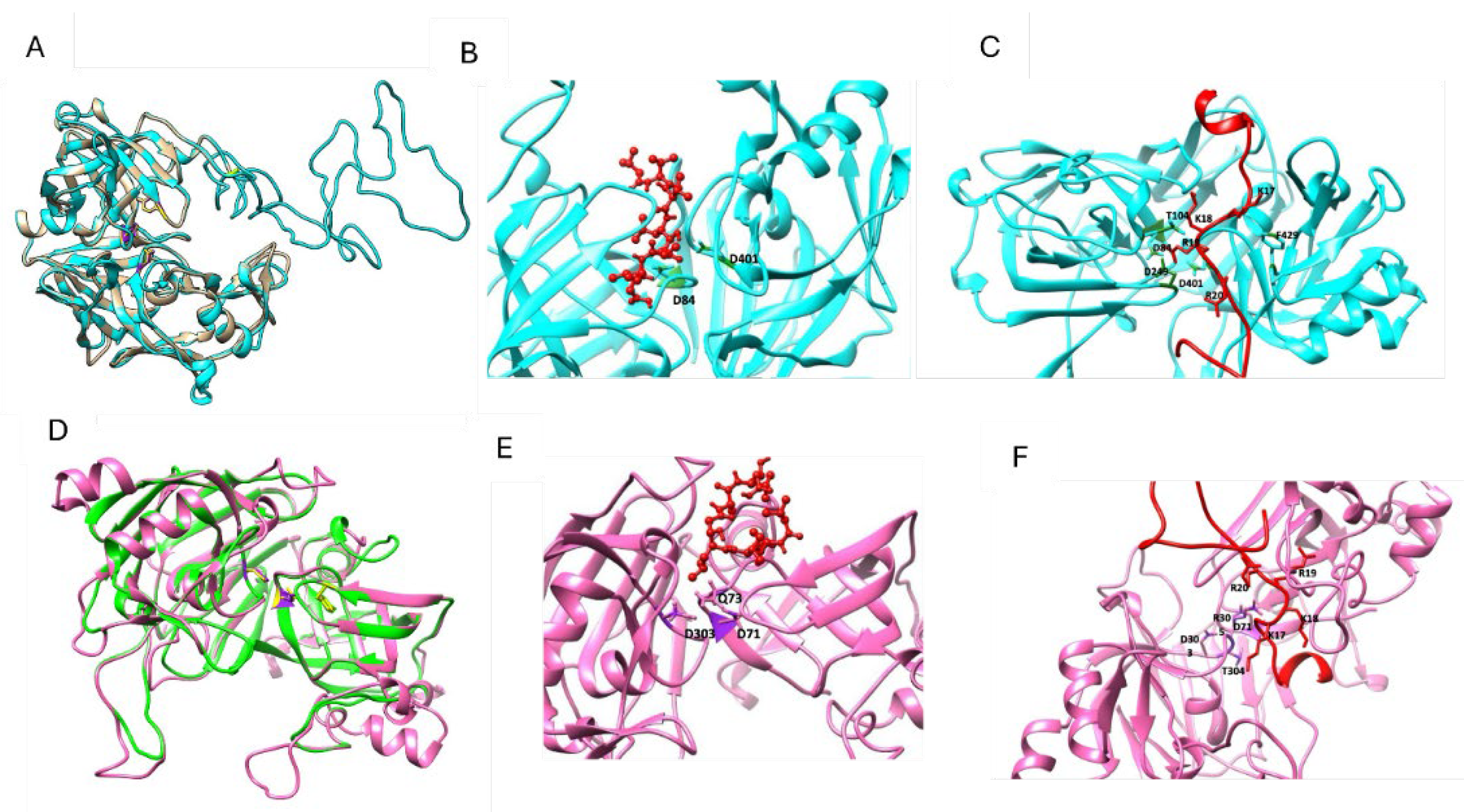

3.3. The C. auris proteins Yps1 and Yps7 Present a Secondary and Tertiary Structure of Aspartyl Proteases, Capable of Binding to the Specific Inhibitor Pepstatin A and Interacting with Other Proteins

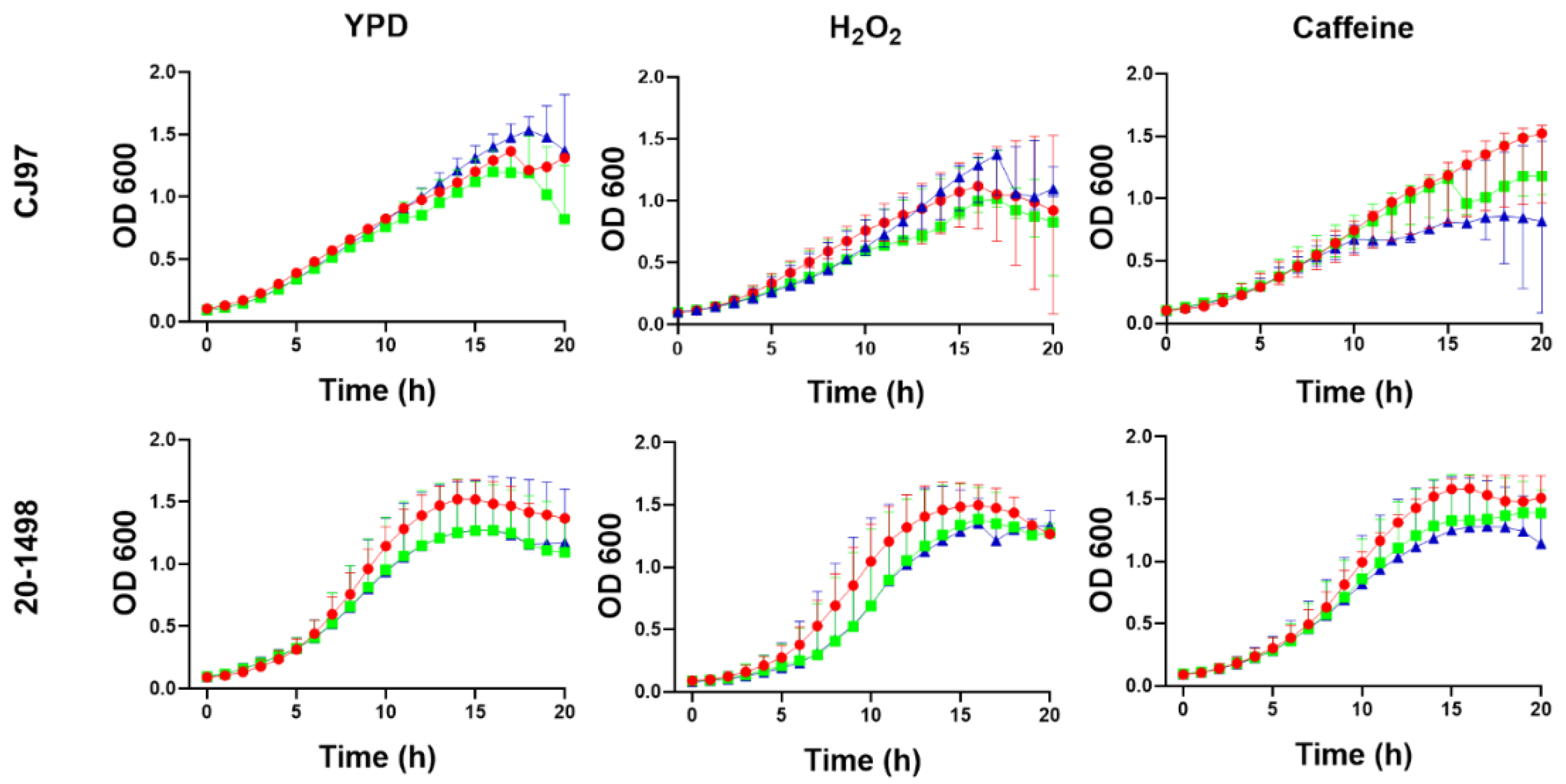

3.4. Growth of C. auris CJ97 and 20-1498 in the Presence of Different Stressor Compounds

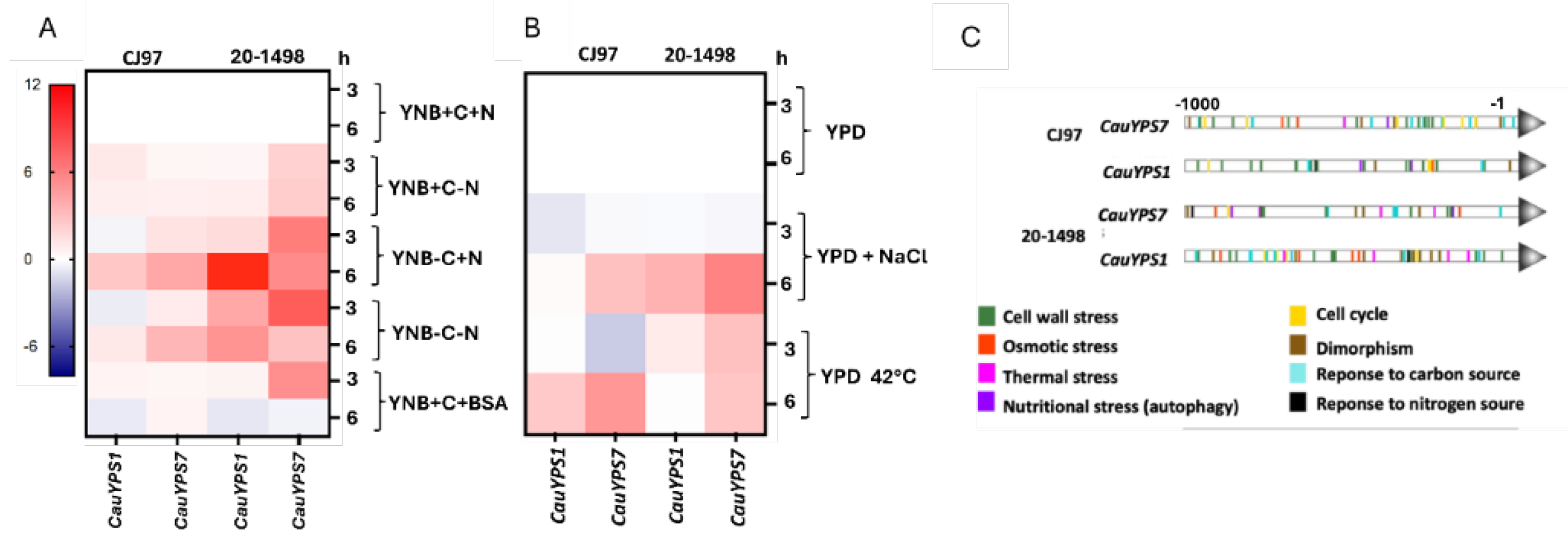

3.5. Differential Expression of YPS1 and YPS7 Genes Under Different Stress Conditions

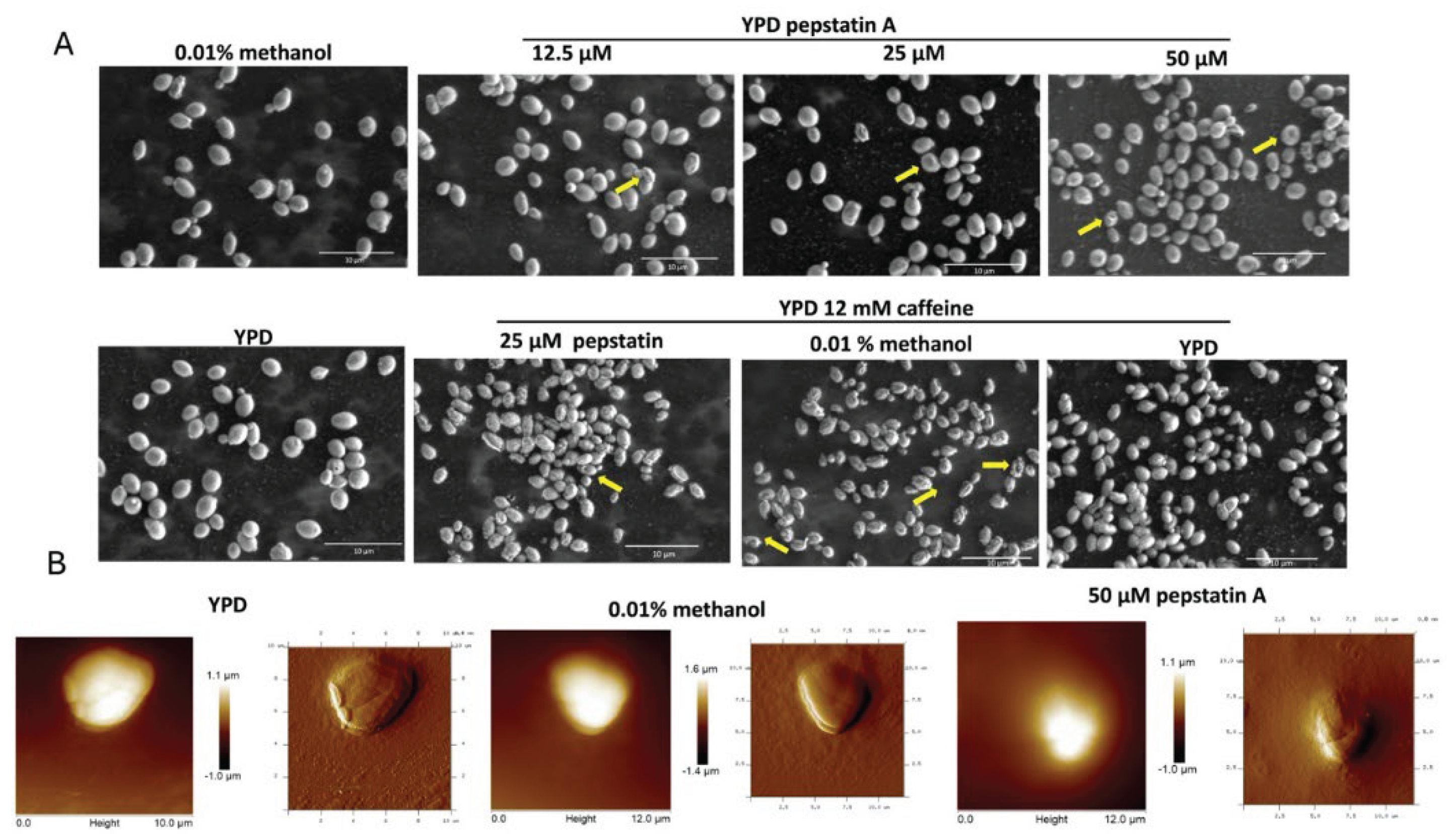

3.6. Effect of Pepstatin A on the Microscopic Morphology of C. auris 20-1498

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hube, B.; Naglik, J. Candida albicans proteinases: Resolving the mystery of a gene family. 2001. Microbiology, 147, 1997–2005. [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, A.; Felk, A.; Pichova, I.; Naglik, J. R.; Schaller, M.; de Groot, P.; MacCallum, D.; Odds, F. C.; Schäfer, W.; Michel, M.; Hube, B. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteases of Candida albicans target proteins necessary for both cellular processes and host-pathogen interactions. 2006. J Biol Chem, 281, 688–694. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Ma, B.; Cormack, B. P. A family of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked aspartyl proteases is required for virulence of Candida glabrata. 2007. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104, 7628–7633. [CrossRef]

- Schild, L.; Heyken, A.; de Groot, P. W.; Hiller, E.; Mock, M.; de Koster, C.; Horn, U.; Rupp, S.; Hube, B. Proteolytic cleavage of covalently linked cell wall proteins by Candida albicans Sap9 and Sap10. 2011. Eukaryot Cell, 10, 98–109. [CrossRef]

- Egel-Mitani, M.; Flygenring, H. P.; Hansen, M. T. A novel aspartyl protease allowing KEX2-independent MF alpha propheromone processing in yeast. 1990. Yeast, 6, 127–137. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, V.; Loh, Y. P. In vivo processing of nonanchored Yapsin 1 (Yap3p). 2000. Arch Biochem Biophys, 375, 315–321. [CrossRef]

- Bourbonnais, Y.; Ash, J.; Daigle, M.; Thomas, D. Y. Isolation and characterization of S. cerevisiae mutants defective in somatostatin expression: cloning and functional role of a yeast gene encoding an aspartyl protease in precursor processing at monobasic cleavage sites. 1993. EMBO J, 12(1), 285–294. [CrossRef]

- Gagnon-Arsenault, I.; Tremblay, J.; Bourbonnais, Y. Fungal yapsins and cell wall: A unique family of aspartic peptidases for a distinctive cellular function. 2006. FEMS Yeast Res, 6, 966–978. [CrossRef]

- de Groot, P. W. J.; Brandt, B. W. ProFASTA: A pipeline web server for fungal protein scanning with integration of cell surface prediction software. 2012. Fungal Genet Biol, 49, 173–179. [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, N. D.; Salvesen, G. Handbook of proteolytic enzymes. 2013. Academic Press.

- Parra-Ortega, B.; Cruz-Torres, H.; Villa-Tanaca, L.; Hernandez-Rodriguez, C. Phylogeny and evolution of the aspartyl protease family from clinically relevant Candida species. 2009. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 104, 505-512 . [CrossRef]

- Satoh, K.; Makimura, K.; Hasumi, Y.; Nishiyama, Y.; Uchida, K.; Yamaguchi, H. Candida auris sp. nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital. 2009. Microbiol Immunol, 53, 41–44. [CrossRef]

- Santana, D. J.; Zhao, G.; O’Meara, T. R. The many faces of Candida auris: Phenotypic and strain variation in an emerging pathogen. 2024. PLoS Pathog, 20, e1012011. [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Bing, J.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, T.; Du, H.; Wang, H.; Huang, G. Filamentation in Candida auris, an emerging fungal pathogen of humans: Passage through the mammalian body induces a heritable phenotypic switch. 2018. Emerg Microbes Infect, 7, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Casadevall, A.; Kontoyiannis, D. P.; Robert, V. On the emergence of Candida auris: Climate change, azoles, swamps, and birds. 2019. mBio, 10. [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Singh, P.; Wang, Y.; Yadav, A.; Pawar, K.; Singh, A.; et al. Environmental isolation of Candida auris from the coastal wetlands of Andaman Islands, India. 2021. mBio, 12. [CrossRef]

- Lockhart, S. R.; Chowdhary, A.; Gold, J. A. The rapid emergence of antifungal-resistant human-pathogenic fungi. 2023. Nat Rev Microbiol, 21, 818–832. [CrossRef]

- Horton, M. V.; Johnson, C. J.; Zarnowski, R.; Andes, B. D.; Schoen, T. J.; Kernien, J. F.; et al. Candida auris cell wall mannosylation contributes to neutrophil evasion through pathways divergent from Candida albicans and Candida glabrata. 2021. mSphere, 6, e0040621. [CrossRef]

- Dakalbab, S.; Hamdy, R.; Holigová, P.; Abuzaid, E. J.; Abu-Qiyas, A.; Lashine, Y.; Mohammad, M. G.; Soliman, S. S. Uniqueness of Candida auris cell wall in morphogenesis, virulence, resistance, and immune evasion. 2024. Microbiol Res, 127797. [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, M.; Gómez-Navajas, J. A.; Blázquez-Muñoz, M. T.; Gómez-Molero, E.; Fernández-Sánchez, S.; Eraso, E.; Munro, C. A.; Valentín, E.; Mateo, E.; de Groot, P. W. J. The good, the bad, and the hazardous: comparative genomic analysis unveils cell wall features in the pathogen Candidozyma auris typical for both baker’s yeast and Candida. 2024. FEMS Yeast Res, 24, foae039. [CrossRef]

- Pezzotti, G.; Kobara, M.; Nakaya, T.; Imamura, H.; Fujii, T.; Miyamoto, N.; Adachi, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Kanamura, N.; Ohgitani, E.; Zhu, W.; Kawai, T.; Mazda, O.; Nakata, T.; Makimura, K. Raman metabolomics of Candida auris clades: Profiling and barcode identification. 2022. Int J Mol Sci, 23, 11736. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. S.; Lee, K. T.; Bahn, Y. S. Secreted aspartyl protease 3 regulated by the Ras/cAMP/PKA pathway promotes the virulence of Candida auris. 2023. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 13, 1257897. [CrossRef]

- Krysan, D. J.; Ting, E. L.; Abeijon, C.; Kroos, L.; Fuller, R. S. Yapsins are a family of aspartyl proteases required for cell wall integrity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. 2005. Eukaryot Cell, 4, 1364–1374. [CrossRef]

- Askari, F.; Rasheed, M.; Kaur, R. The yapsin family of aspartyl proteases regulate glucose homeostasis in Candida glabrata. 2022. J Biol Chem, 298, 101593. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Gaitán, A. C.; Moret, A.; López Hontangas, J. L.; Molina, J. M.; Aleixandre López, A. I.; Cabezas, A. H.; et al. Nosocomial fungemia by Candida auris: First four reported cases in continental Europe. 2017. Rev Iberoam Micol, 34, 23–27. [CrossRef]

- Caballero, U.; Eraso, E.; Quindós, G.; Jauregizar, N. In vitro interaction and killing-kinetics of amphotericin B combined with anidulafungin or caspofungin against Candida auris. 2021. Pharmaceutics, 13, 1333. [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Gaytán, J. J.; Montoya, A. M.; Martínez-Resendez, M. F.; Guajardo-Lara, C. E.; Treviño-Rangel, R. de J.; Salazar-Cavazos, L.; et al. First case of Candida auris isolated from the bloodstream of a Mexican patient with serious gastrointestinal complications from severe endometriosis. 2021. Infection, 49, 523–525. [CrossRef]

- Casimiro-Ramos, A.; Bautista-Crescencio, C.; Vidal-Montiel, A.; González, G. M.; Hernández-García, J. A.; Hernández-Rodríguez, C.; Villa-Tanaca, L. Comparative genomics of the first resistant Candida auris strain isolated in Mexico: Phylogenomic and pan-genomic analysis and mutations associated with antifungal resistance. 2024. J Fungi, 10, 392. [CrossRef]

- Teufel, F.; Almagro Armenteros, J. J.; Johansen, A. R.; Gíslason, M. H.; Pihl, S. I.; Tsirigos, K. D.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. 2022. Nat Biotechnol, 40(7), 1023–1025. [CrossRef]

- Gíslason, M. H.; Nielsen, H.; Almagro-Armenteros, J. J; Johansen A. Prediction of GPI-Anchored proteins with pointer neural networks. 2021. Curr Res Biotechnol, 3. 10.1016/j.crbiot.2021.01.001.c.

- Monteiro, P. T.; Oliveira, J.; Pais, P.; Antunes, M.; Palma, M.; Cavalheiro, M.; Teixeira, M. C. YEASTRACT+: A portal for cross-species comparative genomics of transcription regulation in yeasts. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res, 48, D642–D649. [CrossRef]

- Campanella, J. J.; Bitincka, L.; Smalley, J. MatGAT: An application that generates similarity/identity matrices using protein or DNA sequences. 2003. BMC Bioinformatics, 4, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Larkin, M. A.; Blackshields, G.; Brown, N. P., Chenna, R.; McGettigan, P. A.; McWilliam, H.; Valentin, F.; Wallace, I. M.; Wilm, A.; Lopez, R.; Thompson, J. D.; Gibson, T. J.; Higgins, D. G. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. 2007. Bioinformatics, 23, 2947–2948. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L. T.; Schmidt, H. A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. 2015. Mol Biol Evol, 32, 268–274. [CrossRef]

- Robert, X.; Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. 2014. Nucleic Acids Res, 42, W320–W324. [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F. T.; de Beer, T. A. P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; Lepore, R.; Schwede, T. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. 2018. Nucleic Acids Res, 46, W296–W303. [CrossRef]

- Hanwell, M. D.; Curtis, D. E.; Lonie, D. C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Zurek, E.; Hutchison, G. R. Avogadro: an advanced semantic chemical editor, visualization, and analysis platform. 2012. J Cheminform, 4. [CrossRef]

- Pettersen, E. F.; Goddard, T. D.; Huang, C. C.; Couch, G. S.; Greenblatt, D. M.; Meng, E. C.; Ferrin, T. E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. 2004. J Comput Chem, 25, 1605–1612. [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, J.; Santos-Martins, D.; Tillack, A. F.; Forli, S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: New docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. 2021. J Chem Inf Model, 61, 3891–3898. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Tao, H.; He, J.; Huang, S.-Y. The HDOCK server for integrated protein-protein docking. 2020. Nat Protoc, 15, 1829–1852. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M. E.; Brown, T. A.; Trumpower, B. L. A rapid and simple method for preparation of RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. 1990. Nucleic Acids Res, 18, 3091–3092. [CrossRef]

- Livak, K. J.; Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. 2001. Methods, 25, 402–408. [CrossRef]

- Carolus, H.; Pierson, S.; Muñoz, J. F.; Subotić, A.; Cruz, R. B.; Cuomo, C. A.; Van Dijck, P. Genome-wide analysis of experimentally evolved Candida auris reveals multiple novel mechanisms of multidrug resistance. 2021. mBio, 12, e03333-20. [CrossRef]

- Hager, C. L.; Larkin, E. L.; Long, L.; Zohra Abidi, F.; Shaw, K. J.; Ghannoum, M. A. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the antifungal activity of APX001A/APX001 against Candida auris. 2018. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 62. [CrossRef]

- Bras, G.; Satala, D.; Juszczak, M.; Kulig, K.; Wronowska, E.; Bednarek, A.; Karkowska-Kuleta, J. Secreted aspartic proteinases: Key factors in Candida infections and host-pathogen interactions. 2024. Int J Mol Sci, 25, 4775. [CrossRef]

- Gagnon-Arsenault, I.; Parisé, L.; Tremblay, J.; Bourbonnais, Y. Activation mechanism, functional role and shedding of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored Yps1p at the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell surface. 2008. Mol Microbiol, 69, 982–993. [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.; Battu, A.; Kaur, R. Aspartyl proteases in Candida glabrata are required for suppression of the host innate immune response. 2018. J Biol Chem, 293, 6410–6433. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, V.; Cawley, N. X.; Brandt, J.; Egel-Mitani, M.; Loh, Y. P. Identification and characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae yapsin 3, a new member of the yapsin family of aspartic proteases encoded by the YPS3 gene. 1999. Biochem J, 339, 407–411. [CrossRef]

- Dubé, A. K.; Bélanger, M.; Gagnon-Arsenault, I.; Bourbonnais, Y. N-terminal entrance loop of yeast Yps1 and O-glycosylation of substrates are determinant factors controlling the shedding activity of this GPI-anchored endopeptidase. 2015. BMC Microbiol, 15, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Vadaie, N.; Dionne, H.; Akajagbor, D. S.; Nickerson, S. R.; Krysan, D. J.; Cullen, P. J. Cleavage of the signaling mucin Msb2 by the aspartyl protease Yps1 is required for MAPK activation in yeast. 2008. J Cell Biol, 181, 1073–1081. [CrossRef]

- Miller, K. A.; DiDone, L.; Krysan, D. J. Extracellular secretion of overexpressed glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked cell wall protein Utr2/Crh2p as a novel protein quality control mechanism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. 2010. Eukaryot Cell, 9, 1669–1679. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Alampalli, S. V.; Nageshan, R. K.; Chettiar, S. T., Joshi, S.; Tatu, U. S. Draft genome of a commonly misdiagnosed multidrug resistant pathogen Candida auris. 2015. BMC Genomics, 16, 686. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Progress and challenges in protein structure prediction. 2008. Curr Opin Struct Biol, 18, 342–348. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, N.; Katagiri, T.; Matsumoto, A.; Matsuda, Y.; Arai, H.; Sasaki, N.; Abe, K.; Katase, T.; Ishida, H.; Kusumoto, K. I.; Takeuchi, M.; Yamagata, Y. Oryzapsins, the orthologs of yeast yapsin in Aspergillus oryzae, affect ergosterol synthesis. 2021. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 105, 8481–8494. [CrossRef]

- Silva, R. D. S.; Segura, W. D.; Oliveira, R. S.; Xander, P.; Batista, W. L. Characterization of aspartic proteases from Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and their role in fungal thermo-dimorphism. 2023. J Fungi, 9, 375. [CrossRef]

- Clark-Flores, D.; Vidal-Montiel, A.; Mondragón-Flores, R.; Valentín-Gómez, E.; Hernández-Rodríguez, C.; Juárez-Montiel, M.; Villa-Tanaca, L. Vacuolar proteases of Candida auris from clades III and IV and their relationship with autophagy. 2025. J Fungi, 11, 388. [CrossRef]

- Day, A. M.; McNiff, M. M.; da Silva Dantas, A.; Gow, N. A.; Quinn, J. Hog1 regulates stress tolerance and virulence in the emerging fungal pathogen Candida auris. 2018. mSphere, 3. [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, E.; Hsu, J.; Barth, K.; Goss, J. W. Characterization of the nanomechanical properties of the fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) cell surface by atomic force microscopy. 2021. Yeast, 38, 480–492. [CrossRef]

- Bairwa, G.; Rasheed, M.; Taigwal, R.; Sahoo, R.; Kaur, R. GPI (glycosylphosphatidylinositol)-linked aspartyl proteases regulate vacuole homoeostasis in Candida glabrata. 2014. Biochem J, 458, 323–334. [CrossRef]

- Shivarathri, R.; Chauhan, M.; Datta, A.; Das, D.; Karuli, A.; Aptekmann, A.; Chauhan, N. The Candida auris Hog1 MAP kinase is essential for the colonization of murine skin and intradermal persistence. 2024. mBio, 15, e02748-24. [CrossRef]

- Banda-Flores, I. A.; Torres-Tirado, D.; Mora-Montes, H. M.; Pérez-Flores, G.; Pérez-García, L. A. Resilience in resistance: The role of cell wall integrity in multidrug-resistant Candida. 2025. J Fungi, 11, 271. [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Acosta, E.; Ibarra, J. A.; Ramírez-Saad, H.; Vargas-Mendoza, C. F.; Villa-Tanaca, L.; Hernández-Rodríguez, C. Polymorphism in the regulatory regions of genes CgYPS1 and CgYPS7 encoding yapsins in Candida glabrata is associated with changes in expression levels. 2017. FEMS Yeast Res, 17, fox077. [CrossRef]

- Mercurio, K.; Singh, D.; Walden, E.; Baetz, K. Global analysis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae growth in mucin. 2021. G3, 11, jkab294. [CrossRef]

- Jenull, S.; Tscherner, M.; Kashko, N.; Shivarathri, R.; Stoiber, A.; Chauhan, M.; Petryshyn, A.; Chauhan, N.; Kuchler, K. Transcriptome signatures predict phenotypic variations of Candida auris. 2021. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 11, 662563. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).