1. Introduction

The urgent global drive toward sustainable energy systems have amplified the significance of energy efficiency, particularly in the building sector, which accounts for approximately 30–40% of total final energy consumption worldwide (IEA, 2023). Energy Performance Certification (EPC) has emerged as a vital mechanism in this context, enabling the evaluation and communication of a building's energy usage and efficiency. Through EPC schemes, stakeholders, including homeowners, investors, and policymakers gain insights into a building’s performance, thus promoting informed decisions and incentivizing energy-saving improvements. In Africa, rapid urbanization, population growth, and economic development are placing increasing pressure on energy systems (Hong Vo et al., 2024). By 2050, the continent's building floor area is projected to more than double, underscoring the need for robust energy efficiency frameworks (UNEP, 2022). Yet, EPC implementation across African nations remains limited, inconsistent, and often under-resourced (Edze, 2025). Among the countries making notable progress are Ghana and Nigeria, two West African economies at different stages of integrating EPC within their national energy and building regulations (OECD/IEA, 2014). Ghana has demonstrated significant momentum with policies like the Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS), appliance labelling programmes, and recent training and certification of Energy Performance Assessors through partnerships with institutions like the Ghana Energy Commission and the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) (Ghana Energy Commission, 2024). Nigeria, on the other hand, is progressing through frameworks such as the Building Energy Efficiency Code (BEEC) and the National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP), though challenges around enforcement, awareness, and capacity persist (Osei-Poku et al, 2023; Ogbonna & Nnaji, 2023).

This paper explores the future of EPC in Nigeria and Ghana, focusing on three key dimensions: (1) challenges facing implementation, (2) innovations and tools enhancing performance assessments, and (3) policy pathways for integrated and scalable energy efficiency deployment. Through comparative analysis, the paper identifies actionable strategies that can support both countries in aligning EPC implementation with broader sustainability and climate goals, including commitments under the Paris Agreement and their respective Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Global Context of Energy Performance Certification (EPC)

Energy Performance Certification (EPC) has emerged as a critical instrument in the global effort to improve building energy efficiency and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The concept of EPC originated in the European Union with the implementation of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) in 2002, which mandated member states to introduce EPCs for buildings (European Commission, 2021). Since then, EPC frameworks have been adopted worldwide, including in North America, Asia and parts of Africa, as a tool to provide transparency on the energy consumption and efficiency of buildings, thereby influencing market behavior and policy formulation (Ürge-Vorsatz et al., 2020). Globally, EPCs serve multiple functions: they inform prospective buyers or tenants about the energy performance of buildings, encourage energy-efficient renovations, and support national and international climate goals (IEA, 2023). Innovations such as digitalization of EPC databases, integration with smart metering, and the use of dynamic energy modeling have enhanced the accuracy and usability of EPCs (Wang et al., 2022). Challenges, however, persist. They include inconsistent methodologies, lack of enforcement, and limited public awareness, which undermine the effectiveness of EPC schemes (Guerra-Santin & Tweed, 2021).

2.2. Current State of Energy Performance Certification

In Ghana and Nigeria, the adoption of EPCs is at a nascent stage, reflecting broader trends in sub-Saharan Africa where energy efficiency policies are emerging but not yet fully institutionalized (Agyekum et al., 2022; Oladipo & Adegboye, 2023). Ghana has made strides through its National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP) and the development of building codes that incorporate energy efficiency standards (Ministry of Energy Ghana, 2022). However, formal EPC systems are not yet widely implemented, with pilot projects primarily in commercial buildings and government facilities (Darko et al., 2023; Baidoo, 2024). Nigeria faces similar challenges, with energy efficiency policies embedded within its National Energy Policy but lacking comprehensive EPC frameworks (Federal Ministry of Power Nigeria, 2023). Efforts by organizations such as the Nigerian Energy Support Programme (NESP) have initiated awareness campaigns and capacity building for EPC implementation, yet the market penetration remains limited (Eze et al., 2023). Both countries contend with infrastructural deficits, limited technical expertise, and low stakeholder engagement, which impede the widespread adoption of EPCs.

2.3. Institutional and Regulatory Readiness

Institutional readiness in both countries is characterized by fragmented responsibilities across ministries, agencies, and local governments, leading to coordination challenges (Agyekum et al., 2022; Oladipo & Adegboye, 2023). Regulatory frameworks are evolving; Ghana’s Energy Commission has begun drafting regulations to mandate EPCs for new and existing buildings, while Nigeria’s Standards Organization is working on harmonizing building energy codes with international benchmarks (Ministry of Energy Ghana, 2022; Federal Ministry of Power Nigeria, 2023). Capacity building remains a significant hurdle, with limited numbers of certified energy assessors and inadequate training programs (Darko et al., 2023). Furthermore, enforcement mechanisms are weak, and incentives for compliance are minimal, reducing the motivation for stakeholders to adopt EPCs voluntarily.

2.4. Innovations in EPC Implementation

Innovations relevant to Ghana and Nigeria include the adaptation of low-cost, scalable EPC methodologies suitable for local climatic and economic conditions (Amankwah-Amoah et al., 2023). Digital platforms leveraging mobile technology have been piloted to facilitate data collection and certification processes, improving accessibility in remote areas (Oladipo et al., 2023). Furthermore, integration of renewable energy considerations into EPC frameworks is gaining attention, aligning with the countries’ renewable energy targets (IEA, 2023). Collaborative initiatives with international partners have introduced capacity-building programs and knowledge transfer, fostering innovation in EPC design and deployment (UNEP, 2023).

3. Methodology

This paper employs a qualitative comparative case study approach to examine the development and implementation of Energy Performance Certification (EPC) in Ghana and Nigeria. The methodology is structured around three primary components: literature review, case study selection, and comparative data analysis. An in-depth review of scholarly publications, policy frameworks, and technical reports was undertaken to contextualize the evolution and current state of EPC in the two countries. Key literature reviewed include Gyimah and Addo-Yobo (2014), who explored EPC as a sustainability tool in Ghana’s building sector, highlighting institutional gaps and the importance of trained energy assessors. The Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction, which frames Africa’s broader EPC challenges, identifies Ghana as a pilot country for EPC frameworks under international energy efficiency programs (UNEP, 2022). Studies by Adeleke et al (2023) in Energy and Buildings revealed policy constraints and capacity deficiencies in the implementation of EPC and Building Energy Efficiency Codes (BEEC) in Nigeria. Government and donor-led policy documents were also examined, including the Ghana Energy Commission’s EPC implementation guidelines (2023) and Nigeria’s National Building Energy Efficiency Code (2017) developed under the Nigerian Energy Support Programme [NESP] (Ikudayisi & Adegun, 2025). The study used purposive sampling to analyze key EPC-related initiatives in both countries: The “Energy Performance Assessor Certification Programme,” launched in 2023 by the Ghana Energy Commission and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), was chosen as a representative case. The program involved training 60 professionals to conduct EPC assessments for public and private buildings (KNUST, 2024). The “Building Energy Efficiency Guidelines (BEEG)” implemented under the NESP and pilot applications in Abuja and Lagos were reviewed. Notably, the case of the Federal Ministry of Power's headquarters, designed under BEEC guidelines, provided insight into the early application of EPC principles (Adewolu, 2023). Each case was assessed based on implementation structure, stakeholder engagement, technological frameworks, and policy integration. A comparative thematic analysis was employed to extract and synthesize insights from the two case studies. The data were coded using NVivo software to identify five (5) recurring themes (Institutional coordination, Capacity development, Legal and regulatory support, Public-private collaboration, Technological readiness). Cross-case analysis allowed the identification of common barriers and enabling factors. For example, both countries face a lack of financing mechanisms for EPC implementation, but Ghana benefits from stronger institutional coordination between the Energy Commission, academia, and international partners (Gyimah & Addo-Yobo, 2014; UNEP, 2022). Conversely, Nigeria’s fragmented policy enforcement limits the uptake despite the existence of technical frameworks (Adeleke et al., 2023).

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Policy Framework

A comparative analysis of energy performance certification frameworks between Ghana and Nigeria reveals fundamental differences in governance structures that significantly influence policy development and implementation approaches. Ghana operates under a unitary system characterized by centralized policymaking mechanisms, which enables more coherent policy development through unified national standards and clear institutional hierarchies (

Table 1). The country's regulatory architecture is anchored by the National Energy Policy of 2010 and the more recent Energy Efficiency Policy of 2020, with the Energy Commission Ghana serving as the single primary regulator for energy-related matters. This centralized approach facilitates streamlined decision-making processes and reduces jurisdictional complexity, though it may potentially limit opportunities for local adaptation and innovation. In contrast, Nigeria's federal system presents a more complex governance landscape where state-level autonomy creates both opportunities and challenges for energy performance certification implementation. The country's regulatory framework is built upon the National Energy Policy of 2013 and the National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP) covering 2015-2030, but implementation occurs through multiple agencies including the Energy Commission of Nigeria (ECN), the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC), and various Federal Ministries. This multi-institutional approach, while potentially fostering innovation at the state level, creates significant coordination challenges and jurisdictional complexities that can impede uniform policy implementation.

The building code status in both countries reflects these structural differences, with Ghana pursuing a centralized revision approach while Nigeria experiences fragmented, state-level variations. Both nations currently lack comprehensive mandatory energy performance certification legislation, and their existing building codes require substantial updates to adequately address energy efficiency requirements. The enforcement mechanisms remain limited in both contexts, with voluntary compliance dominating current practice rather than mandatory regulatory frameworks as depicted by

Table 1.

4.2. Institutional and Regulatory Readiness

The regulatory ecosystem in Ghana appears more prepared for EPC enforcement compared to Nigeria. Ghana’s Energy Commission operates under a clear legislative mandate. Specified in the Renewable Energy Act 2011 (Act 832), it provides a legal foundation for energy efficiency interventions, including EPC (Energy Commission Ghana, 2021). The Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS), adopted in 2005 and updated in 2020, have over the period resulted in energy savings of over 8,000 GWh between 2007 and 2020 in Ghana (Tamakloe, 2022). In contrast, Nigeria lacks a unified legal framework mandating EPC in building construction. Although the Energy Commission of Nigeria (ECN) and the Nigerian Building and Road Research Institute (NBRRI) support energy efficiency, and have jointly developed building energy codes, enforcement mechanisms are weak or non-existent (Adeleke et al., 2018). Furthermore, energy-related data for buildings is fragmented, impeding efforts to benchmark and certify building performance.

4.3. Implementation Capacity

Comparative analysis identified performance in five critical EPC implementation dimensions: policy framework, training programs, stakeholder engagement, financial support and technology readiness (

Table 2). Ghana demonstrates relatively stronger performance across most metrics, particularly in training and engagement, while both countries struggle with financial mechanisms.

The paper triggered a rating system using a likert scale graduated from 1 to 5, where 1 implies

very weak and 5,

very Strong (Nunoo, Twum & Panin, 2016). Ghana scores a 4 on the scale, indicating a strong and well-developed policy framework supporting EPC initiatives (

Table 1). This suggests that Ghana has made significant progress in formulating policies and regulations that promote energy efficiency in buildings. Nigeria, with a score of 3, shows moderate policy development but may still face gaps in enforcement or comprehensiveness of EPC-related regulations. Training programs are crucial for building the technical capacity necessary for EPC implementation. Ghana’s score of 5 reflects a very strong commitment to training and capacity building, likely supported by well-structured programs for certifying energy assessors and related professionals. Nigeria’s score of 2 indicates limited training opportunities, which could hinder the development of skilled personnel required to support EPC schemes. Ghana also outperforms Nigeria in stakeholder engagement, scoring 4 compared to Nigeria’s 2. This suggests that Ghana has been more effective in involving building owners, developers, policymakers, and financiers in the EPC process, fostering greater awareness and demand. Nigeria’s lower score points to insufficient stakeholder involvement, which may limit the acceptance and uptake of EPCs. In terms of technology readiness, Ghana scores 3, indicating moderate adoption of digital tools and platforms to facilitate EPC processes. Nigeria’s score of 2 suggests that technological infrastructure and innovation supporting EPCs are still in early stages, potentially limiting efficiency and scalability. Both countries score equally low at 2 in financial support, highlighting a shared challenge in providing adequate funding mechanisms such as subsidies, incentives, or affordable financing options for EPC-related activities. This financial constraint remains a significant barrier to widespread EPC adoption.

4.4. Implementation Strategies and Progress

Implementation strategies adopted by both countries reflect their respective governance structures and institutional capacities. Ghana has developed a sequential approach characterized by clear phases and unified coordination mechanisms. The first phase, spanning 2024-2026, focuses on policy framework development through unified national standards, single institutional coordination, public building pilots, and professional certification program launches (Osei-Poku et al, 2023). This is followed by a market development phase from 2026-2028, emphasizing commercial building requirements, incentive mechanisms, private sector engagement, and regional implementation. The final phase, covering 2028-2030, aims for full implementation including residential buildings, comprehensive monitoring systems, performance optimization, and regional cooperation initiatives (Al-Otaibi et al, 2025).

Nigeria's multi-track approach reflects the complexity of its federal system (

Table 1), requiring simultaneous coordination across multiple levels of government (Adewolu, 2023). The foundation-building phase from 2024-2026 emphasizes federal framework development alongside state-level pilot programs, institutional coordination mechanisms, and professional capacity building initiatives. The parallel implementation phase from 2026-2028 accommodates both federal standards and state variations, implementing multi-level incentive systems, regional demonstration projects, and technology transfer programs. The final harmonization and scale-up phase from 2028-2030 focuses on federal-state harmonization, cross-state coordination, national monitoring systems, and regional integration efforts. The institutional coordination strategies further highlight these differences, with Ghana employing a centralized coordination model led by the Energy Commission as the primary agency, featuring clear hierarchical structures, unified decision-making processes, and relatively limited stakeholder complexity (Tettey et al, 2025). Nigeria requires a more sophisticated multi-level coordination approach, potentially involving a proposed National Building Energy Performance Council, federal-state coordination protocols, inter-agency coordination mechanisms, and complex stakeholder management systems (Adewolu, 2023).

Ghana has made modest but notable progress in operationalizing EPCs, especially through institutional support and capacity-building programs (Energy Commission Ghana, 2023). Notably, the Ghana Energy Commission, in collaboration with GIZ under the Sustainable Energy for Climate Protection (SE4C) project, trained and certified 60 Energy Performance Assessors (EPAS) in 2024 to assess public building (KNUST, 2024).

Table 3.

Energy performance assessment.

Table 3.

Energy performance assessment.

| Indicator |

Ghana |

Nigeria |

| EPC Policy Framework |

Emerging (Energy Commission, SE4C) |

Conceptual (BEEC, BEEG, NESP) |

| Trained Energy Performance Assessors |

60+ certified (as of 2024) |

<10 professionals trained |

| Legal Support |

Renewable Energy Act 2011, MEPS |

Fragmented regulatory mandates |

| Market Penetration |

Limited to public buildings |

Negligible |

| Innovation Deployment |

Digital EPC registry, pilot audits |

Mobile EPC apps, pilot audits |

This initiative has enhanced the ability of the country to conduct building energy audits, laying a foundation for EPC rollouts for future certification schemes in residential and public buildings. Implementation progress in Nigeria, is at a nascent stage of EPC development. While efforts have been made to establish foundational documents such as the Building Energy Efficiency Code (BEEC) and Building Energy Efficiency Guidelines (BEEG), implementation has remained sporadic (Federal Ministry of Power Nigeria, 2023). The Nigerian Energy Support Programme (NESP), with support from international partners such as the EU and GIZ, has contributed to policy formation (Adeleke et al., 2018), yet practical enforcement and market uptake are limited. Survey data and stakeholder interviews suggest that less than 15% of new building developments in urban centers like Abuja and Lagos have adopted any form of energy performance assessment (Nwankwo et al, 2024).

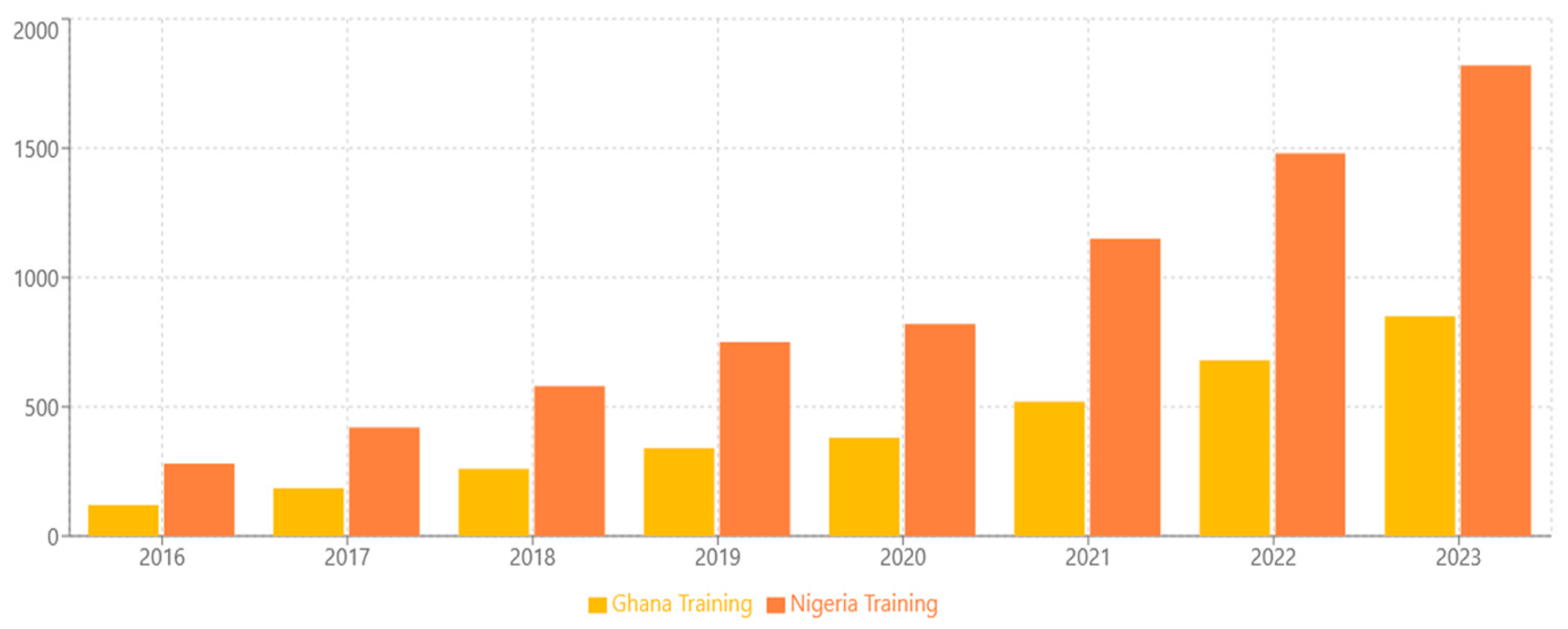

Figure 1.

Training programs participation.

Figure 1.

Training programs participation.

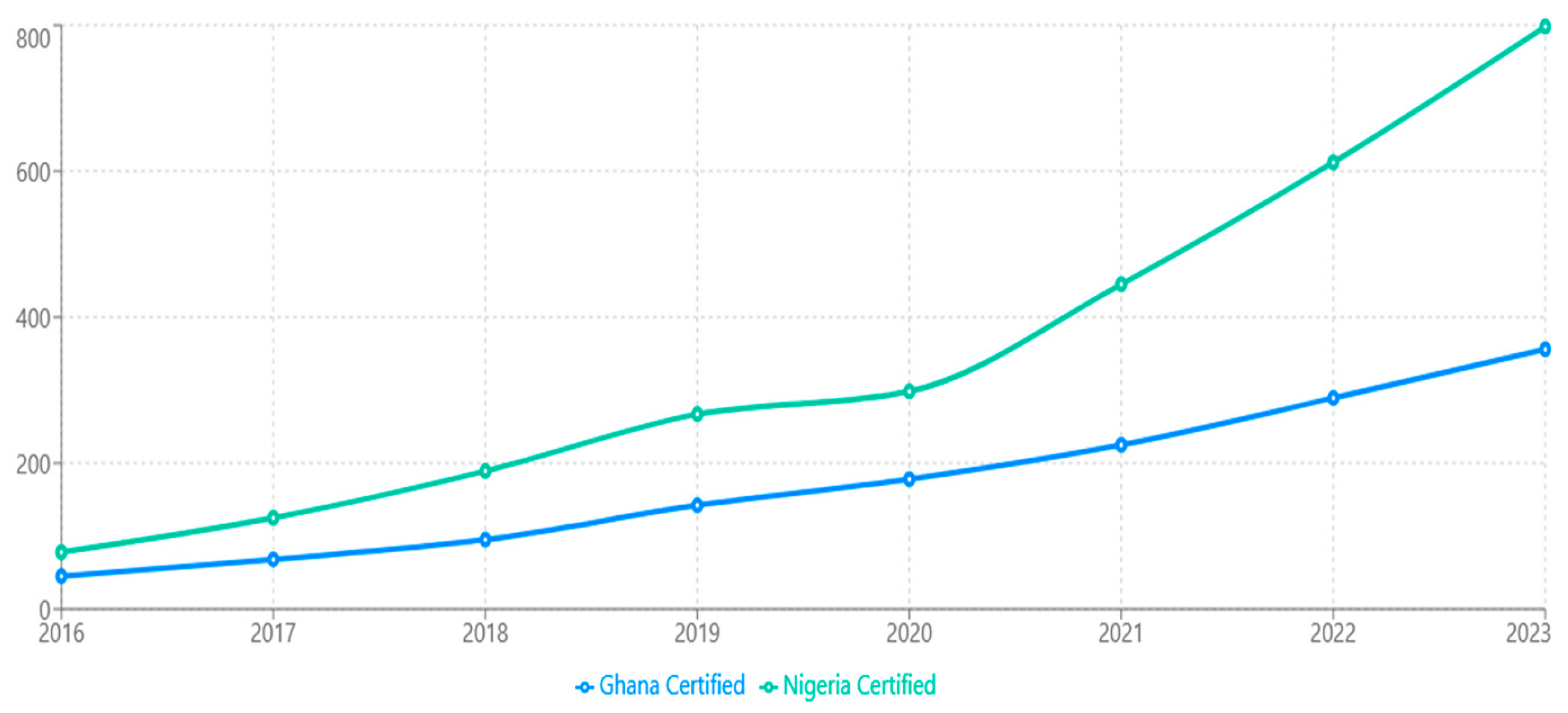

Figure 2.

Certified professionals’ growth.

Figure 2.

Certified professionals’ growth.

4.5. Technical Capacity and Development Pathways

The technical and capacity development approaches in both countries reflect their broader governance philosophies and institutional structures. Ghana's centralized capacity building strategy focuses on developing a national certification program for energy auditors, establishing university partnerships for curriculum development, implementing centralized training standards, and creating unified continuing education requirements (Nunoo, 2019b). This approach ensures consistency in professional standards and competencies across the country but may limit opportunities for regional specialization and innovation. While Ghana has made headway by certifying assessors, there still remain a significant shortage of trained professionals to implement EPC at scale (Anzagira, 2019). Most assessments to date have focused on government buildings, with little penetration into residential or commercial real estate sectors (Gyimah & Addo-Yobo, 2014). Nigeria's distributed capacity building approach operates through a federal certification framework with state-level implementation, multiple university partnerships across different regions, varied training approaches that accommodate local contexts, and federal standards delivered through state-level mechanisms (Oladipo & Adegboye, 2023). This approach allows for greater regional adaptation and potentially faster scaling but requires more sophisticated coordination to ensure quality and consistency. Nigeria's technical landscape is, however, constrained. Studies show that energy data collection systems are underdeveloped, limiting the feasibility of EPC deployment (Olaniyan et al., 2021). Interviews with officials from the Nigerian Institute of Architects (NIA) and the Nigerian Society of Engineers (NSE) confirmed outcomes of studies by Abiodun et al (2022), indicating a lack of exposure to EPC methodologies, that needs technical upskilling attention. These capacity constraints are exacerbated by low awareness among property developers and financiers about the long-term benefits of energy-efficient buildings (Oni et al, 2020).

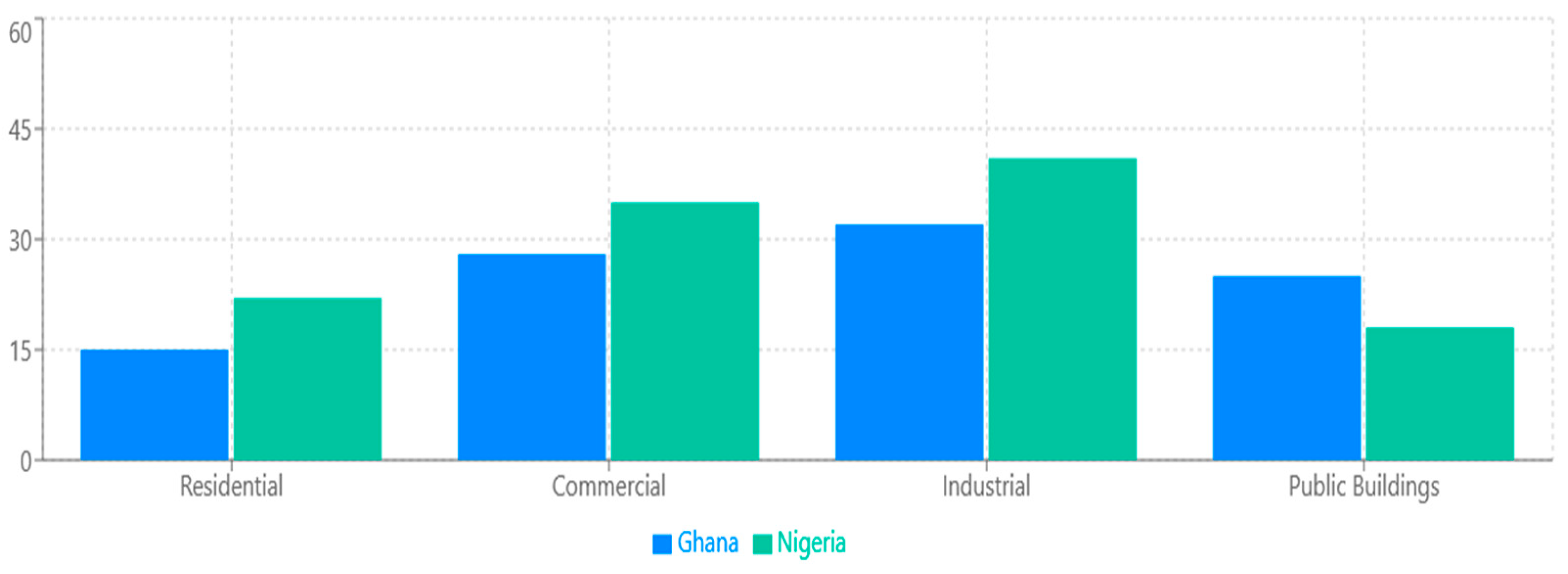

Figure 3.

Energy Efficiency Improvements by Sector (%).

Figure 3.

Energy Efficiency Improvements by Sector (%).

Table 4.

Key Achievements in Energy Efficiency Improvements.

Table 4.

Key Achievements in Energy Efficiency Improvements.

| Achievements in Energy Efficiency Improvements |

|---|

| Ghana |

Nigeria |

| Established National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (2019) |

National Energy Efficiency Action Plan implemented (2017) |

| 356 certified energy auditors trained |

798 certified energy professionals |

| 267 buildings with energy performance certificates |

478 buildings with performance certifications |

| 25% average energy savings in certified buildings |

30% average energy reduction in industrial sector |

|

$72.1M invested in energy efficiency programs (2023) |

$198.7M invested in efficiency initiatives (2023) |

Research and development strategies further demonstrate these differences, with Ghana pursuing a focused approach through a national building energy research center, concentrated research funding mechanisms, unified technology development priorities, and centralized knowledge management systems (Nunoo et al, 2019). Nigeria employs a distributed research and development strategy featuring multiple regional research centers, diverse funding sources and priorities, state-specific technology needs assessment, and decentralized knowledge sharing mechanisms (NESP, 2023).

4.6. Economic Policy Instruments and Market Development

The economic policy instruments employed by both countries reflect their governance structures and market development philosophies. Ghana's approach emphasizes national-level coordination through proposed national property tax reductions, development of a unified national green bond market, centralized green procurement policies, national utility rebate programs, and fast-track approval processes for certified buildings. This centralized approach aims to create uniform market conditions and standardized incentives across the country. Cost and economic feasibility are recurring challenges in Ghana. Developers cite the added costs of conducting EPC assessments and retrofitting buildings as a disincentive in the absence of financial incentives or subsidies (Addo-Yobo & Gyimah, 2014). While the Ghana Infrastructure Investment Fund (GIIF) has explored green building financing, uptake remains limited. Nigeria's economic policy framework accommodates the federal system's complexity through state-level property tax variations, with Lagos already implementing specific measures, multiple state and federal financing programs, varied federal and state procurement policies, state-specific utility partnerships, and state-level planning incentives. Although a few large-scale property developers in Lagos have adopted green design elements, EPC remains absent in most urban and peri-urban developments (Oladipo & Adegboye, 2023). While this approach allows for regional adaptation and innovation, it requires more complex coordination mechanisms to ensure overall coherence. The system is challenged with macroeconomic instability (Oni et al., 2020). Fluctuating exchange rates, high inflation, and limited access to affordable credit deter investments in energy efficiency adoption.

Market development strategies further illustrate these philosophical differences. Ghana pursues a national market approach featuring a unified national green building rating system, centralized professional certification processes, national awareness campaigns, and standardized market incentives (Nunoo et al, 2019). This approach aims to create a coherent national market with consistent standards and expectations. Nigeria's multi-market approach accommodates regional diversity through state-specific rating systems coordinated at the federal level, multiple certification pathways, targeted regional campaigns, and diverse market incentives. While this approach allows for greater local adaptation, it requires sophisticated coordination mechanisms to prevent market fragmentation and ensure interoperability across states.

Table 4.

Financial incentive mechanisms.

Table 4.

Financial incentive mechanisms.

| Instrument Type |

Ghana |

Nigeria |

| Tax Incentives |

National property tax reductions (proposed) |

State-level property tax variations (Lagos implemented) |

| Green Financing |

Development of the national green bond market |

Multiple state and federal financing programs |

| Public Procurement |

Centralized green procurement policy |

Federal and state procurement variations |

| Utility Incentives |

National utility rebate programs |

State-specific utility partnerships |

| Development Incentives |

Fast-track approvals for certified buildings |

State-level planning incentives |

4.7. Policy Innovation and Technology Transfer Mechanism

The study reveals the emergence of innovative practices across the divide. Ghana has piloted digital EPC tools through the Energy Commission’s online registry, improving data access and transparency. Integration with smart metering technologies is also being explored (Energy Commission Ghana, 2023). In Nigeria, early-stage startups such as “EcoAudit” have developed mobile energy audit tools to assess small commercial buildings (Adeleke et al., 2023). However, these innovations are often limited in scale and sustainability due to reliance on donor funding (Abiodun et al., 2022). Both countries have shown policy ambition by embedding EPC in broader climate and energy frameworks. Ghana’s National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP) aims for 10% renewable energy in power generation by 2030 (Tettey et al, 2025) and Nigeria’s Energy Transition Plan (ETP), which aims for 60% renewable energy in power generation by 2060 (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2022), provide strategic pathways for EPC institutionalization. However, translating these high-level strategies into enforceable regulations is essential. Achieving these goals will require mainstreaming EPC into national building codes and urban planning policies.

Technology transfer mechanisms reflect similar patterns, with Ghana centralizing international partnerships through the Energy Commission, establishing national standards for local conditions, integrating national industrial policy, and providing centralized innovation funding. Nigeria manages multiple federal and state partnerships, emphasizes regional adaptation with federal coordination, implements state-level industrial development programs, and supports multiple innovation ecosystems. These findings suggest that while both countries face similar challenges in implementing energy performance certification systems, their different governance structures necessitate distinct approaches to policy development, implementation, and coordination. Ghana's unitary system enables more streamlined and coherent policy implementation but may limit local innovation and adaptation. Nigeria's federal system allows for greater regional experimentation and adaptation but requires more sophisticated coordination mechanisms to ensure overall coherence and effectiveness.

Table 5.

Policy innovation and technology transfer.

Table 5.

Policy innovation and technology transfer.

| Aspect |

Ghana |

Nigeria |

| International Partnerships |

Centralized through Energy Commission |

Multiple federal and state partnerships |

| Technology Adaptation |

National standards for local conditions |

Regional adaptation with federal coordination |

| Local Manufacturing |

National industrial policy integration |

State-level industrial development programs |

| Innovation Support |

Centralized innovation funding |

Multiple innovation ecosystems |

5. Conclusions, Recommendations and Future Research

5.1. Conclusions

This paper examined the status, challenges, and future directions of Energy Performance Certification (EPC) in Ghana and Nigeria. It found that while both countries recognize the importance of EPC as a tool for promoting energy efficiency and reducing emissions, their implementation is at different developmental stages. Ghana has made measurable progress, supported by institutional mandates, limited technical capacity building, and pilot initiatives. In contrast, Nigeria’s efforts are primarily at the policy drafting stage, hindered by fragmented regulatory frameworks, low awareness, and a lack of enforcement capacity. Despite these challenges, the study identified emerging innovations such as digital EPC platforms in Ghana and mobile auditing applications in Nigeria. However, the effectiveness of these innovations remains constrained by economic barriers, limited technical know-how, and the absence of market-based incentives.

5.2. Recommendations

To effectively scale Energy Performance Certification (EPC) systems and align them with national energy and climate goals, a comprehensive and coordinated approach is required. First and foremost, strengthening regulatory frameworks is critical. Both countries must enact binding EPC legislation that is seamlessly integrated into national building codes and climate strategies. This legal foundation will provide the necessary authority and structure to ensure compliance and long-term institutional support. Equally important is the need to build technical capacity across institutional and professional domains. Partnerships between governments, academic institutions, and international donors can facilitate the large-scale training of EPC professionals. This workforce development is essential for ensuring consistent implementation, accurate assessments, and the credibility of EPC systems. To promote widespread adoption, developing incentive mechanisms is essential. Policy instruments such as tax reliefs, grants, and green financing tools should be introduced to encourage uptake, particularly among private developers and small-scale property owners. These financial incentives can help offset initial costs and make energy-efficient construction and retrofitting more attractive. In addition, enhancing data systems is crucial for effective monitoring and evaluation. Establishing robust national energy databases will allow for real-time tracking of building performance, support data-driven policymaking, and enable benchmarking across sectors. Reliable data is the backbone of any performance-based regulatory system and is vital for transparency and accountability. Finally, governments should leverage digital technologies to improve the efficiency and transparency of EPC processes. Investments in digital EPC platforms, remote auditing tools, and smart metering systems will streamline data collection, reduce administrative burdens, and enhance stakeholder engagement.

Looking ahead, several key areas for future research have been identified. A cost-benefit analysis of EPC implementation is necessary to quantify the long-term financial returns for households and businesses, thereby informing policy and investment decisions. Additionally, user perception and behavioral studies can provide insights into the attitudes of end-users and developers, helping to shape effective awareness campaigns. Research should also focus on the applicability of EPC in informal and low-income housing, which constitutes a major portion of urban dwellings in many developing countries. Moreover, integrating EPC with decentralized renewable energy systems, such as solar photovoltaics, could offer holistic and sustainable energy solutions. Finally, the development of monitoring and evaluation (M&E) frameworks specific to EPC is essential for tracking progress, ensuring compliance, and guiding continuous improvement over time.

Author Contributions

Edward Kweku Nunoo: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation Supervision. Joseph Essandoh-Yeddu: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Eric Twum: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Clement Oteng: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Joseph Asafo: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Philomina Kwabena: Writing – review & editing, Investigation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and principles for research involving human participants and the use of secondary data. The research follows the ethical standards outlined by the Declaration of Helsinki and adheres to the ethical policies of Societal Impact. For the collection of primary data, informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study. Participants were provided with detailed information about the purpose of the research, their rights to confidentiality, and their ability to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. All personal data collected during the study were anonymized to ensure participant privacy and confidentiality. Secondary data utilized in this research were obtained from publicly available, credible sources, and proper attribution has been provided where required. No proprietary or restricted-access data were used without proper authorization. Efforts were made to ensure that the secondary data used was reliable, accurate, and relevant to the objectives of the study. This research posed no foreseeable physical, psychological, or social risks to participants, and all data collection methods were designed to minimize any potential harm. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Cape Coast.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Adeleke, O. A. ; et al. Transition towards energy efficiency: Developing the Nigerian Building Energy Efficiency Code. Sustainability 2023, 10, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewolu, A. Green Building Certification in Nigeria: A Comparative Study of Selected Rating Systems. International Journal of Engineering Inventions 2023, 12, 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- Addo-Yobo, F.O. Strategies and challenges for energy efficient buildings in tropical developing countries: A case-study in Ghana. Journal of Building Performance 2014, 5, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Agyekum, E.B.; Darko, A.; Osei-Asibey, D. Energy efficiency policy and implementation in West Africa. Energy Policy Journal 2022, 17, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Sarpong, D.; Nyuur, R. Low-cost innovations in energy certification for developing countries. Energy and Buildings 2023, 287, 112986. [Google Scholar]

- Anzagira, L.; Badu, E.; Duah, D. Towards an uptake framework for the green building concept in Ghana: A theoretical review. Resourceedings 2019, 2, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiodun, O.; Edeoja, O.; Umar, L. Assessing energy efficiency readiness in Nigeria’s construction sector. Journal of Sustainable Architecture and Design 2022, 10, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Otaibi, A.; Bowan, P.A.; Alabdullatief, A.; Albaiz, M.; Salah, M. Barriers to sustainable building project performance in developing countries: A case of Ghana and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoo, A.N.A.; Danquah, J.A.; Nunoo, E.K.; et al. Households’ energy conservation and efficiency awareness practices in the Cape Coast Metropolis of Ghana. Discover Sustainability 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, A.; Agyekum, E.B.; Osei-Asibey, D. Institutional gaps in Ghana’s energy efficiency policy. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 112–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ebekozien, A.; Ikuabe, M.; Awo-Osagie, A.; Aigbavboa, C.; Ayo-Odifiri, S. Model for promoting green certification of buildings in developing nations: A case study of Nigeria. Property Management. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edze, P. Local content requirements for the transfer of knowledge and skills in the solar photovoltaic industry in Ghana. Energy for Sustainable Development 2025, 85, 101682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Commission Ghana. Ghana’s energy efficiency programme report. Accra: Energy Commission. 2021. Available online: https://www.energycom.gov.gh.

- Energy Commission Ghana. EPC digital registry development project. Accra: Energy Commission. 2023. Available online: https://www.energycom.gov.gh.

- European Commission. Energy Performance of Buildings Directive; European Commission: Brussels, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Government of Nigeria. (2022). Energy transition plan: Nigeria’s pathway to net zero emissions. Abuja: Office of the Vice President.

- Federal Ministry of Power Nigeria. (2023). National energy policy update. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Power.

- Guerra-Santin, O.; Tweed, C. Measuring the effectiveness of EPC in Europe. Energy Policy 2021, 148, 111941. [Google Scholar]

- Gyimah, K.A.; Addo-Yobo, F. Energy performance certificate of buildings as a tool for sustainability of energy and environment in Ghana. International Journal of Research 2014, 1, 757–762. [Google Scholar]

- Hong Vo, T.; Nguyen, H.; Pham, Q. Urbanization and renewable energy consumption in the emerging ASEAN markets: A comparison between short and long-run effects. Heliyon 2024, 10, e14890. [Google Scholar]

- KNUST. (2024). Sixty participants receive certification as energy performance assessors. Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. Available online: https://www.knust.edu.

- Ministry of Energy Ghana. (2022). National energy efficiency action plan. Accra: Ministry of Energy.

- Nunoo, E. K., Mariwah, S., & Suleman, S. (2019). Energy efficiency processes and sustainable development in HEIs. In W. L. Filho & M. Misfsud (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education (pp. 495–504). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Nunoo, E. K. (2019a). Sustainable waste management systems in higher institutions: Overview and advances in Central University Miotso, Ghana. In W. L. Filho (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Nunoo, E. K. (2019b). Sustainability assessment in Ghana’s higher educational institutions using the assessment questionnaire as a tool. In W. L. Filho (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Nunoo, E.K.; Twum, E.; Panin, A. A criteria and indicator prognosis for sustainable forest management assessments: Concepts and optional policy baskets for the high forest zone in Ghana. Journal of Sustainable Forestry 2016, 35, 149–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, N.C.; Madougou, S.; Inoussa, M.M.; et al. Review of Nigeria’s renewable energy policies with focus on biogas technology penetration and adoption. Discover Energy 2024, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Poku, G., Koranteng, C., Amos-Abanyie, S., Botchway, E. A., & Gyimah, K. A. (2023). A review of frameworks for the energy performance certification of buildings and lessons for Ghana. In C. Aigbavboa, J. N. Mojekwu, W. D. Thwala, L. Atepor, & E. Adi (Eds.), Sustainable Education and Development – Sustainable Industrialization and Innovation (pp. 63–80). Springer.

- Oladipo, T.; Adegboye, A. Energy efficiency practices in Nigeria’s real estate sector. Property Management 2023, 41, 66–82. [Google Scholar]

- Oni, A.O.; Oyewole, T.T.; Adeniji, T.O. Economic barriers to sustainable energy in Nigeria: A stakeholder-based approach. Energy Reports 2020, 6, 405–412. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/IEA. (2014). Africa energy outlook: A focus on energy prospects in Sub-Saharan Africa (World Energy Outlook Special Report). Paris: International Energy Agency.

- Oyedepo, S.O. Energy and sustainable development in Nigeria: The way forward. Energy, Sustainability and Society 2012, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikudayisi, A.E.; Adegun, O.B. Pathways for green building acceleration in fast-growing countries: A case study on Nigeria. Built Environment Project and Asset Management. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaye-Larbi, H. (2016). Analysis of technical and financial benefits of energy efficient practices in selected Electricity Company of Ghana (ECG) buildings in Accra. KNUST Thesis Repository.

- Tamakloe, E. K. (2022). The impact of energy efficiency programmes in Ghana. In Alternative Energies and Efficiency Evaluation. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Tettey, G.; Ansah, E.A.; Asante, W. The politics of renewable energy transition in Ghana: Issues, obstacles and prospects. Energy Research & Social Science 2025, 120, 103939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Novikova, A.; Koppel, S. Lessons from global EPC implementation. Energy and Buildings 2020, 224, 110230. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, X. Future trends in digital EPC implementation. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 80, 103761. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).