Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Current State of Statistics Education and Challenges

3. Theoretical Framework: Bridging Music and Statistics

3.1. Mastery Learning

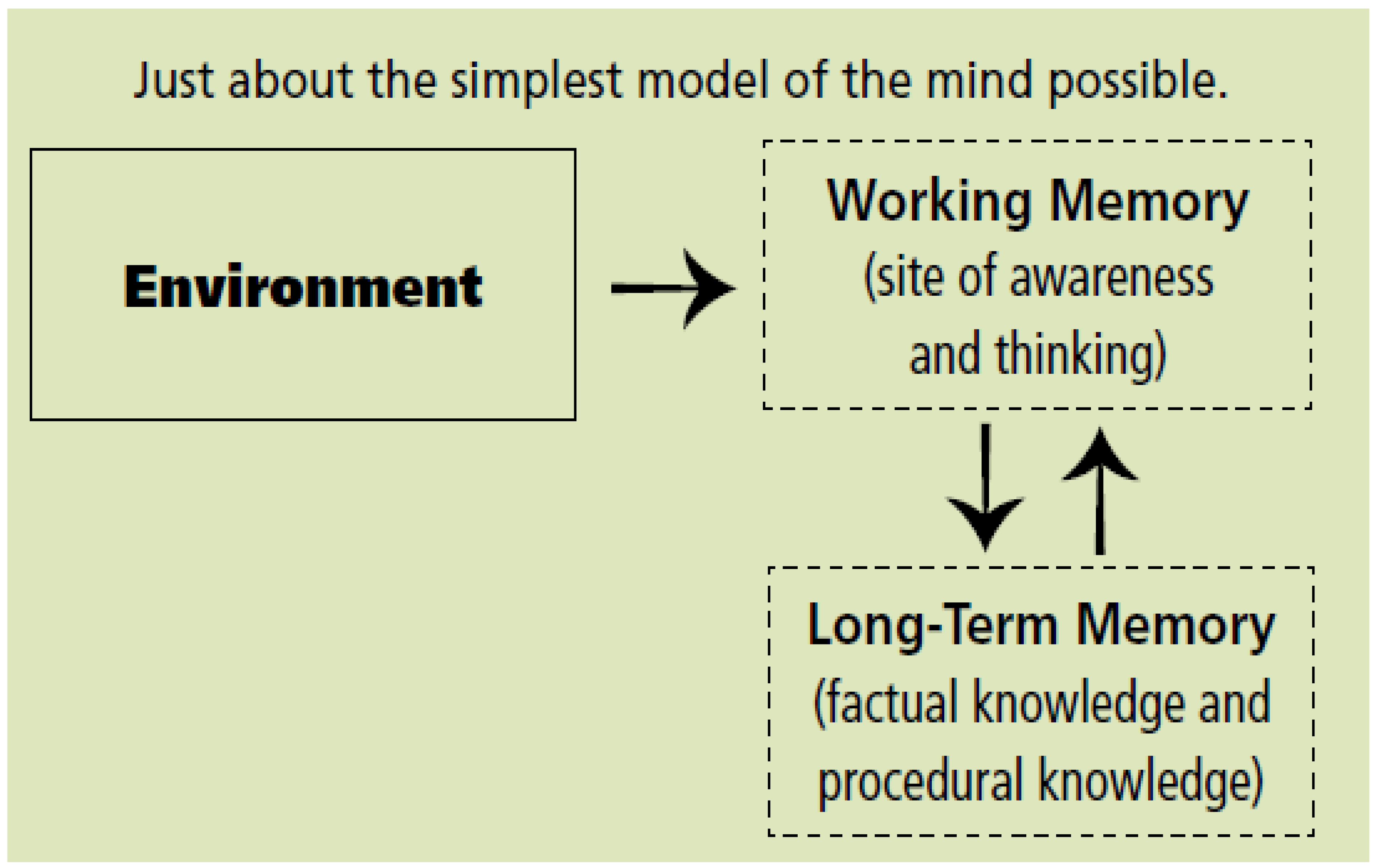

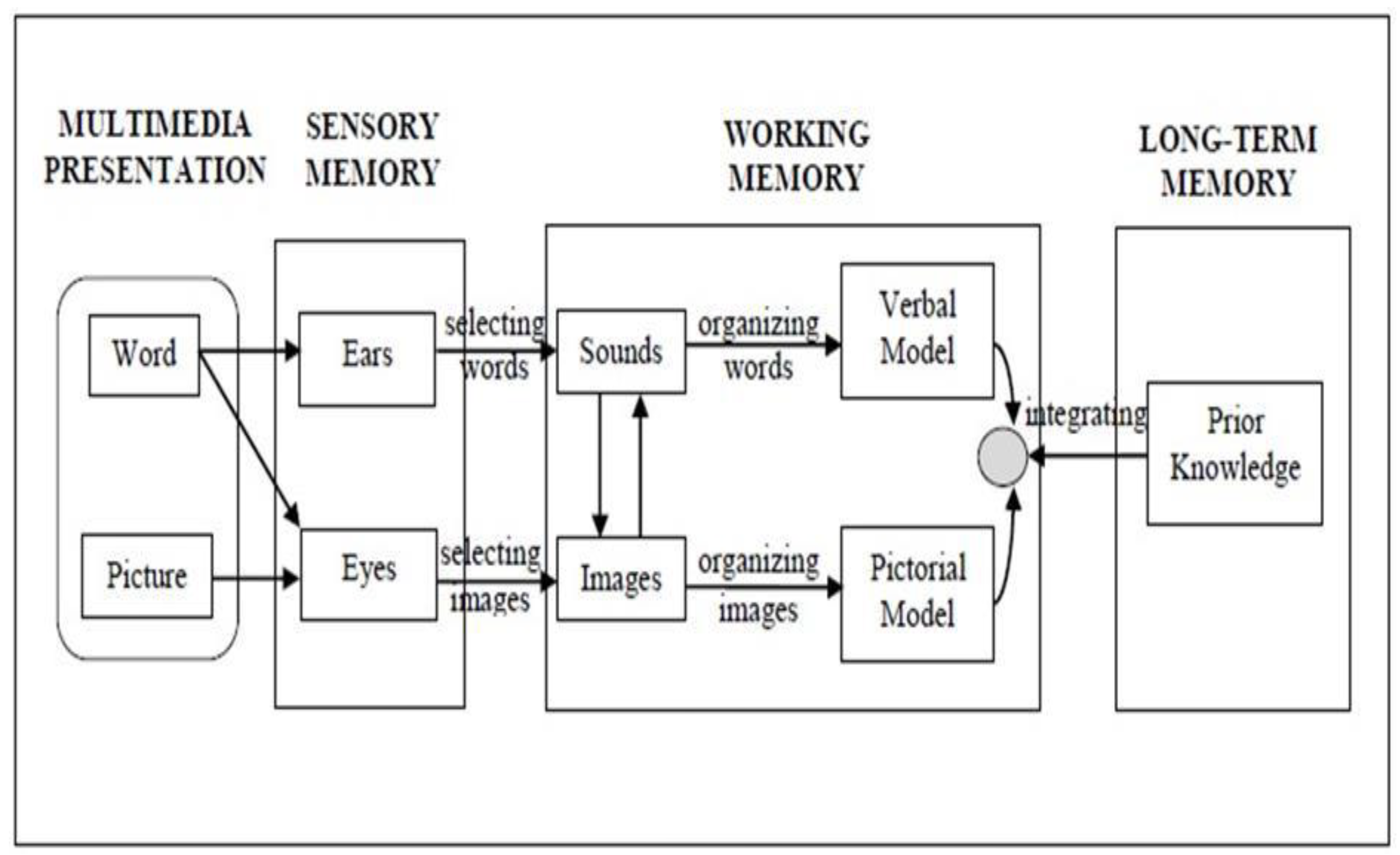

3.2. Cognitive Load Theory

3.3. Multiple Intelligences

3.4. Affective Domain and Embodied Cognition

3.5. Constructivism

4. Practical Implementation: Music in Statistics Education

4.1. Key Stage Three (Ages 11–14): Foundations and Involvement

- KS3 emphasizes the introduction of probability, descriptive statistics, and fundamental data handling. One can use music to make these first meetings interesting and natural.

- Students can represent frequency distributions using rhythmic patterns. Rhythm for Mode and Frequency. For instance, a teacher could give a consistent beat (e.g., a quarter note) for every data point and students clap louder or faster for more often occurring values. The mode is the most often heard rhythm/clap. They may create brief rhythmic compositions wherein the number of occurrences a particular beat or instrument has corresponds to a frequency.

- Short, memorable jingles or songs might be developed to define and remember the central tendency metrics of Melody for Mean, Median, Mode, Range. For example, a basic tune could explain mean is average, add them up and divide, median is middle, line them up and find, and mode is most, it appears the most.

- Pitch for Data Scales: Students may use different tones to reflect various values in a dataset; higher pitches correspond to bigger numbers and lower tones correspond to smaller ones. This can audibly and visually demonstrate the dissemination of data.

- Simple probability experiments (e.g., rolling a die, flipping a coin) can be complemented with unique musical sounds for every result. Probability allows pupils to forecast noises, therefore making the idea more concrete and engaging, as visually demonstrated by Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 (c.f., Kurt, 2023).

- Children were supposed to find the centre point, position the cards on the circle, and then group the cards by colour to build a pie graph. It seemed that the kids found making pie charts simpler than making bar graphs. „How can we easily determine which colour is the most and which colour is the least?” was the question posed to the kids, like the bar graph exercise. Surprisingly, most kids (n = 24 of 28) knew where the circle’s centre was. They also compared the cards to slices of pizza. „Will we play a pizza game?” was a question that many of them asked. The cards were further categorised by colour by sixteen of them. Several illustrations of children’s pie charts are shown in Figure 8.

- Furthermore, some pattern reasoning was evident in the pie chart representations. As seen in the examples in Figure 9, some kids organised the cards in a recurring pattern.

- Students could gather basic categorical data (e.g., preferred colours, pets) and connect musical phrases or instruments to each category. They then create a brief composition whereby the frequency of that category is indicated by the length or number of times a word is played. This practical development helps to clarify information representation.

4.2. Key Stage Four, Ages 14–16: Advanced Ideas and Connections.

- KS4 covers more sophisticated subjects including standard deviation, correlation, sampling, and advanced data representation. Music offers concrete illustrations for these abstract concepts as well as parallels.

- Dynamics for variability (standard deviation) can be demonstrated using musical dynamics—a concept typically hard for pupils. Little variance in loudness (piano to mezzoforte) could indicate a little standard deviation; wide dynamic swings (pianissimo to fortissimo) would indicate a big standard deviation. Students can examine musical compositions to determine and define their dynamic range, then link it to disseminated data (Hallam & Himonides, 2022).

- Harmony for Correlation: Chord progressions could symbolize correlation. Consonant chords (e.g., C major) could represent a strong positive correlation, where two variables move in the same direction harmonically. Dissonant chords (e.g., a cluster chord) might represent weak or negative correlation, where variables show little or opposing relationship. Using bivariate data, students can produce a correlation soundscape.

- By taking brief rhythmic phrases from a longer musical piece, one can show the concept of sampling from a bigger population. Students evaluate if the sampled phrases appropriately reflect the overall tempo, rhythm, and melodic patterns of the whole piece, which spurs conversations about bias and representativeness in sampling (Zayed, 2018; Mageed & Bhat 2022; Mageed & Zhang, 2022; Mageed & Zhang, 2023; Mageed, 2023; Mageed, 2024e; Mageed, 2024f, Mageed, 2024g; Mageed, 2024h; Mageed 2024i).

- Musical Patterns for Time Series Data: Time series data, such as economic trends or population growth, can be mapped onto musical patterns. A rising trend could be represented by an ascending melody, a cyclical pattern by a repeating musical phrase, and volatility by sudden changes in tempo or pitch. Students could analyze graphs of time series data and then try to musically represent them.

- Data sonification projects: Using basic audio libraries in Scratch, Python, etc., students may sonify real-world datasets. Temperature data, for instance, could be mapped to pitch; humidity to volume; then they can listen for patterns and linkages in environmental data. This links computational thinking and actual world science with statistics (Lindborg et al., 2024).

4.3. Key Stage Five (Ages 16-18): Inferential Statistics and Modelling

- KS5 learners explore probability distributions, statistical modelling, hypothesis testing, and inferential statistics. Music can aid in seeing abstract distributions and reinforcing intricate logical reasoning.

- Soundscapes enable representation of normal distribution, skewed distributions, and uniform distributions. A normal distribution might have a thick sound at the mean (middle of the pitch range) that thins out towards the extremes, while a uniform distribution would have an even spread of sound across the entire pitch range. By listening to the acoustic representation of the type of distribution, students could attempt to determine it (Grondin, 2025).

- Through a multipart musical phrase or short song, one may memorize and comprehend the organized logic of hypothesis testing (null hypothesis, alternative hypothesis, significance level, p-value, decision). Every portion of the phrase matches a step, which strengthens the procedural memory.

- Pitch for P values: It can be conceptual the idea of a p value and its connection with statistical significance. Consider a continuous pitch range denoting p values from 0 to 1. Significance might be suggested by a threshold sound (e.g., a specific note) at= 0.05. A different, more definitive sound might start to play when the p value pitch falls below this threshold. This gives a sound signal for decision making (Hales, 2023).

- Rhythmic Complexity for Model Fit: In regression analysis, the fit of a model can be illustrated by how well a simple rhythmic pattern (the model) aligns with a complex, observed rhythmic pattern (the data). A good fit would mean the model’s rhythm closely matches the data’s rhythm, while a poor fit would result in jarring or misaligned beats.

- Students could design projects to examine a data set, reach statistical conclusions, and then produce a musical composition telling the story of their results. For instance, a piece exploring social inequalities might use jarring harmonies and fluctuating tempos to represent disparities, whereas a piece about steady growth might use consistent, ascending melodies. Statistical literacy is combined here with artistic expression and narrative construction (Rumelhart & Ortony, 2017).

5. Benefits and Challenges

5.1. Advantages

- Music’s natural attractiveness may turn a dull topic into an interesting and pleasurable experience, thereby lowering worry and boosting student readiness to participate (Váradi, 2022).

- Multisensory inputs (auditory, kinesthetic, visual through musical notation) can help create more intuitive grasp of abstract statistical ideas by strengthening neural connections (Gage, 2009).

- Melodies, rhythms, and ordered musical patterns provide mnemonic tools that assist with the recall of formulas, definitions, and procedural phases (Degé et al., 2011).

- Tapping into musical intelligence widens the appeal of statistics to students with varied learning styles, therefore promoting success for those who might not prosper in conventional, entirely logical mathematical settings (Waterhouse, 2023).

- Interdisciplinary learning naturally connects math with the arts, hence fostering a whole grasp of knowledge and showing the interdependence of disciplines (Reinhardt, 2020).

- Developing Critical Thinking and Creativity: Writing and understanding musical representations of data challenges pupils to think critically about how data translates into meaning and to communicate these insights creatively (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996).

- The iterative nature of musical performance and practice—where errors offer chances for growth— fits well with the tenets of mastery learning and encourages a development attitude toward statistics challenges (Megaptche & Ramanantsoa, 2023).

5.2. Difficulties

- Curricular Integration and Time Restrictions: Appropriately planned and justified integration of creative musical events into an already crowded curriculum is crucial. It ought to be viewed as augmenting rather than replacing already available material (Shirley, 2017).

- Access to musical instruments, digital audio workstations (DAWs), or music education software could differ amongst schools (Third et al., 2025). Basic tools like body percussion, vocal work, and online sequencers can help to reduce this.

- Building reliable and accurate evaluation techniques that evaluate statistical understanding acquired via musical activities rather than only musical skill calls for great thought (Heritage, 2021).

- Distraction Potential: Music can become a distraction rather than a learning tool if not properly managed. Activities should be deliberate and intimately connected to statistical goals (Hanham et al., 2023).

- Student Resistance: Some students may first fight against unconventional teaching techniques or feel self-conscious about participating in music activities in a math lesson. Key is establishing a welcoming and nonjudgemental classroom atmosphere (Ntoumanis, 2023).

6. Practical Implementation Strategies

- There are several techniques necessary to properly include music into statistics instruction:

- Offer workshops for mathematics instructors concentrated on fundamental music ideas, music technology resources appropriate for use in schools, and pedagogical examples of music-statistics integration in collaboration with music department personnel (Copur-Gencturk &Thacker, 2021).

- Locate statistical learning goals where music integration could be most effective using curriculum mapping. Begin gently, maybe with one or two essential ideas per term, then progressively broaden (Richmond, 2018).

- Make use of easily accessible technology like online sequencers (e.g., Chrome Music Lab, GarageBand online), basic coding systems (e.g., Python with pydub), or even free virtual instruments. For teachers as well as students, these tools can lower the entry hurdle (Reid et al., 2023.).

- Collaborative Projects: Promote group projects in which students create or present musical pieces reflecting data together. Through shared creation, this encourages peer learning, cooperation, and more profound conceptual understanding (Alós-Ferrer & Garagnani, 2020).

- Invite musicians, data artists, or statisticians who use sound in their work to motivate pupils and show actual applications of data sonification (Wickens et al., 2021).

- Enable students to create their own musical interpretations of statistical ideas via student-led development. This supports individual tastes, fosters inventiveness, and encourages learning ownership (Papert, 2022).

- Formative Assessment Integration: See musical activities as chances for formative assessment. Watch how pupils interpret information into sound, pay attention to their justifications for their musical selections, and offer instant criticism (Jikandi, 2021).

- Help instructors and provide inspiration by compiling a shared repository of musical examples, lesson plans, templates, and student-created works.

7. Assessment and Evaluation

- Performance-Based Assessment: Students might be judged on their capacity to produce a musical composition that accurately depicts a certain dataset, together with a lucid justification of their musical and statistical decisions. This shows conceptual as well as practical knowledge (Brown, 2017). Long-term initiatives ending in a „statistical soundscape” or a &”data-driven song” can be evaluated for statistical precision, musical inventiveness, and narrative clarity. Rubrics should clearly specify standards for musical expression as well as statistical thinking (Boss & Krauss, J.2022). Teachers can observe students during music exercises and record their level of participation, problem-solving techniques, and conceptual knowledge. Focused conversations following musical tasks can expose more profound understanding of their learning (Chappuis et al., 2020).

- Using established criteria, students can assess one another’s musical statistical projects, hence encouraging critical thought and reinforcing their own knowledge (Heritage, 2021).

- Although conventional quizzes and tests still matter, questions can include scenarios based on musical data or request students to interpret imagined musical depictions of statistical ideas. Quantitative data could include student performance on standardized tests compared to conventional approaches, attendance rates, and optional course enrolment in statistics. Qualitative data could be acquired via student and teacher surveys, focus groups, and interviews examining impressions of engagement, understanding, and enjoyment (Gregar, 2023). Evaluation of the overall program should involve collecting both quantitative and qualitative data. Longitudinal studies might monitor the long-term effects on statistical literacy and attitudes toward mathematics.

References

- Alós-Ferrer, C. and Garagnani, M., 2020. The cognitive foundations of cooperation. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 175, pp.71-85. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, P. and Franklin, C., 2021. What makes a good statistical question?. Journal of Statistics and Data Science Education, 29(1), pp.122-130.

- Bloom, B.S., 1968. Learning for Mastery. Instruction and Curriculum. Regional Education Laboratory for the Carolinas and Virginia, Topical Papers and Reprints, Number 1. Evaluation comment, 1(2), p.n2.

- Boss, S. and Krauss, J., 2022. Reinventing project-based learning: Your field guide to real-world projects in the digital age. International Society for Technology in Education.

- Brown, G.T., 2017. Assessment of student achievement. Routledge.

- Buchner, J., Buntins, K. and Kerres, M., 2022. The impact of augmented reality on cognitive load and performance: A systematic review. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(1), pp.285-303. [CrossRef]

- Chappuis, J., Stiggins, R.J., Chappuis, S. and Arter, J., 2020. Classroom assessment for student learning: Doing it right--using it well (p. 432). New York, NY, USA: Pearson.

- Cheah, C.S., 2022. The importance of multimedia elements in learning and the impact of redundancy principle in developing effective multimedia learning materials: A literature review. Journal of Educational Sciences & Psychology, 12(2), pp.3-12.

- Copur-Gencturk, Y. and Thacker, I., 2021. A comparison of perceived and observed learning from professional development: Relationships among self-reports, direct assessments, and teacher characteristics. Journal of teacher education, 72(2), pp.138-151.

- della Putta, P. and Suner Munoz, F., 2023. The present and the future of embodiment and cognitive linguistics in language teaching. In 7th International Symposium on Figurative Thought. Cognitive, bodily, and cultural processes in Figurative Thought and Language.

- Fink, L.D., Davis, J.R. and Arend, B.D., 2023. Facilitating seven ways of learning: A resource for more purposeful, effective, and enjoyable college teaching. Routledge.

- Gage, N.L. 2009. A conception of teaching. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Gardner, H. , 2020. A synthesizing mind: A memoir from the creator of multiple intelligences theory. mit Press.

- Gikandi, J.W. 2021. Enhancing E-learning through integration of online formative assessment and teaching presence. International Journal of Online Pedagogy and Course Design (IJOPCD), 11(2), pp.48-61.

- Gregar, J. 2023. Research design (qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches). Research Design, 8.

- Grondin, S. 2025. Psychophysics. In Psychology of perception (pp. 1-16). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Hales, A.H. 2023. One-tailed tests: Let’s do this (responsibly). Psychological Methods. [CrossRef]

- Hallam, S. and Himonides, E., 2022. The power of music: An exploration of the evidence. Open Book Publishers.

- Hanham, J. Castro-Alonso, J.C. and Chen, O., 2023. Integrating cognitive load theory with other theories, within and beyond educational psychology. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, pp.239-250. 239–250. [CrossRef]

- Heritage, M. 2021. Formative assessment: Making it happen in the classroom. Corwin Press.

- https://www.elivabooks.com/en/book/book-1450104825 (Accessed 10/06/2025).

- Jung, C.G. and Hull, R.F.C., 2023. The Complications of American Psychology 1. In Collected Works of CG Jung (pp. v10_502-v10_514). Routledge.

- Kurt, G. 2023. Young children’s probabilistic and statistical reasoning in the context of informal statistical inference. Statistics Education Research Journal, 22(2), pp.4-4.

- Lange, C. Almusharraf, N., Koreshnikova, Y. and Costley, J., 2021. The effects of example-free instruction and worked examples on problem-solving. Heliyon, 7(8). [CrossRef]

- Lindborg, P. Caiola, V., Ciuccarelli, P., Chen, M. and Lenzi, S., 2024. Re (de) fining Sonification: Project Classification Strategies in the Data Sonification Archive. AES: Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, 72(9), pp.585-602.

- Mageed, I. A. 2025a. The Hidden Poetry & Music of Mathematics for Teaching Professionals: Inspiring Students through the Art of Mathematics: A Guide for Educators. Eliva Press. https://www.elivabooks.com/en/book/book-1450104825.

- Mageed, I.A. 2025b. The Hidden Dancing & Physical Education of Mathematics for Teaching Professionals. Eliva Press. https://www.elivabooks.com/en/book/book-7724827898.

- Mageed, I.A. and Bhat, A.H., 2022. Generalized Z-Entropy (Gze) and fractal dimensions. Appl. math, 16(5), pp.829-834.

- Mageed, I.A. and Nazir, A.R., 2024. AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity through Ismail A Mageed’s Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Annals of Process Engineering and Management, 1(1), pp.33-85.

- Mageed, I.A. and Zhang, Q., 2022, September. An introductory survey of entropy applications to information theory, queuing theory, engineering, computer science, and statistical mechanics. In 2022 27th international conference on automation and computing (ICAC) (pp. 1-6). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. and Zhang, Q., 2023. Formalism of the Rényian maximum entropy (RMF) of the stable M/G/1 queue with geometric mean (GeoM) and shifted geometric mean (SGeoM) constraints with potential geom applications to wireless sensor networks (WSNs). Electronic journal of computer science and information technology, 9(1), pp.31-40.

- Mageed, I.A. 2023. Cosistency axioms of choice for Ismail’s entropy formalism (IEF) Combined with information-theoretic (IT) applications to advance 6G networks. European journal of technique (ejt), 13(2), pp.207-213.

- Mageed, I.A. 2024a. Do You Speak The Mighty Triad?(Poetry, Mathematics and Music) Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. MDPI Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. , 2024b. The Mathematization of Puzzles or Puzzling Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. , 2024c. Let’s All Dance and Play Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. , 2024d. AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity Through Ismail A Mageed’s Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. 2024e. Entropy-based feature selection with applications to industrial internet of things (IoT) and breast cancer prediction. Big Data and Computing Visions, 4(3). 170–179.

- Mageed, I.A. 2024f. Entropic imprints on bioinformatics. Big Data and Computing Visions, 4(4). 245–256.

- Mageed, I.A. 2024g. Entropic Artificial Intelligence and Knowledge Transfer. Adv Mach Lear Art Inte, 5(2). 01–08.

- Mageed, I.A. 2024h. On the Rényi Entropy Functional, Tsallis Distributions and Lévy Stable Distributions with Entropic Applications to Machine Learning. Soft Computing Fusion with Applications, 1(2). 87–98.

- Mageed, I.A. , 2024i. Towards An Info-Geometric Theory Of The Analysis Of Non-Time Dependent Queueing Systems. Risk Assessment and Management Decisions, 154–197.

- Maratos, F. Byrd, J., Mosey, C. and Maratos, F., 2023. Schooling in England–An Overview. DYNAMIS. Rivista di filosofia e pratiche educative, 5(5). 21–33.

- McGaghie, W.C. Barsuk, J.H., Salzman, D.H., Adler, M., Feinglass, J. and Wayne, D.B., 2020. Mastery learning: opportunities and challenges. Comprehensive healthcare simulation: Mastery learning in health professions education, pp.375-389.

- Megaptche, Y.R.M. and Ramanantsoa, I.J., 2023. Metaphor as a key tool in personal development discourse: An extended conceptual metaphor theory approach to the study of Carol Dweck’s Mindset: The new psychology of success. Review of Cognitive Linguistics.

- Ntoumanis, N. 2023. The bright, dark, and dim light colors of motivation: Advances in conceptualization and measurement from a self-determination theory perspective. In Advances in motivation science (Vol. 10, pp. 37-72). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Papert, S.A. 2020. Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas. Basic books.

- Reid, L. Button, D. and Brommeyer, M., 2023. Challenging the myth of the digital native: A narrative review. Nursing Reports, 13(2), pp.573-600. [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, T. 2020. Geertz, Clifford: The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. In Kindlers literatur lexikon (KLL) (pp. 1-2). Stuttgart: JB Metzler. [CrossRef]

- Richmond, W.K. 2018. The school curriculum. Routledge.

- Rodríguez-Alveal, F. and Aguerrea, M., 2024. Statistical Inference in School Textbooks. An Approach to Statistical Thinking. Uniciencia, 38(1), pp.341-356. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A. 2022. Learning to reason with data: How did we get here and what do we know?. In Situating Data Science (pp. 154-164). Routledge.

- Rumelhart, D.E. and Ortony, A., 2017. The representation of knowledge in memory 1. In Schooling and the acquisition of knowledge (pp. 99-135). Routledge.

- Schilling, R.L. and Kühn, F., 2021. Counterexamples in measure and integration. Cambridge University Press.

- Sestir, M.A. Kennedy, L.A., Peszka, J.J. and Bartley, J.G., 2023. New statistics, old schools: An overview of current introductory undergraduate and graduate statistics pedagogy practices. Teaching of Psychology, 50(3), pp.211-221.

- Shirley, D. 2017. The new imperatives of educational change. Routldege. New York.

- Third, A. Livingstone, S. and Lansdown, G., 2025. Recognizing children’s rights in relation to the digital environment: challenges of voice and evidence, principle and practice. In Research Handbook on Human Rights and Digital Technology (pp. 325-360). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Váradi, J. 2022. A review of the literature on the relationship of music education to the development of socio-emotional learning. Sage Open, 12(1), p.21582440211068501. [CrossRef]

- Venohr, Y. 2025. Music Emotion Recognition. In Deep Learning in Personalized Music Emotion Recognition (pp. 5-19). Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Waterhouse, L. 2023. Why multiple intelligences theory is a neuromyth. Frontiers in psychology, 14, p.1217288. [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C.D. Helton, W.S., Hollands, J.G. and Banbury, S., 2021. Engineering psychology and human performance. Routledge.

- Willingham, D.T. 2021. Why don’t students like school?: A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom. John Wiley & Sons.

- Winnicott, D.W. 2018. Ego distortion in terms of true and false self. In The person who is me (pp. 7-22). Routledge.

- Zayed, A. 2018. Advances in Shannon’s sampling theory. Routledge.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).