Introduction

Composition of the Blue Crab (Callinectes sapidus): Detailed Analysis of Constituents

The blue crab (Callinectes sapidus) is a complex marine organism with a rich and intricate anatomical composition. The crab is covered by an exoskeleton composed of chitin, a biopolymer formed by N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) units with β-1,4 bonds. This biopolimer is the second most abundant in the natural kingdom, and gives resilience and flexibility to the shells of arthropods. Moreover there are structural proteins: such as cuticle proteins and chitin-binding proteins which contribute to the robustness and the integrity of the shell.

Blue crab’s adipose tissue is composed of a complex mixture of lipids that are relevant for energy balance and thermal regulation: fatty acids, phospholipids and sterols. Concerning the muscle tissue, the presence of nucleic acids essential for protein synthesis and vital functions was revealed by numerous studies.

In addition to its structural components, Blue Crabs can accumulate trace elements and minerals, especially calcium and phosphorus, which are responsible for the mineralization of the shell, ensuring its hardness. The shell of the crab contains carotenoids, specifically astaxanthin, a red-orange coloured pigment. During the research, the main difficulties were caused by the slow action of the bacterial fermentation. Usually for the extraction of chitin it took us 7 to 8 days to complete the process. Moreover, the bacterial action is highly influenced by environmental conditions such as: temperature, pH, oxygenation and the level of nutrients. These conditions were optimized along the way. We did not always manage to obtain optimal deproteinization and demineralization, because the mixture of nutrients rich broth, bacteria and crab powder, tended to create clumps and areas more concentrated than others. Since our institute does not possess a bioreactor, we had to equip ourselves with one. At the end of the process, following the extraction of chitin, numerous tests were carried out on the sample through an infrared spectrometer, which ultimately allowed us to compare the structure of our product with a chemically obtained one.

Biological Action

The most common procedure for the production of chitin is based on a first demineralization of the lyophilized shell together with NaOH 1M for a time of about 20h, followed by a deproteinization with the aid of HCl at a concentration that can vary from 3% to 5% for about 16 h. The extraction of chitin is then concluded with a wash in distilled water.

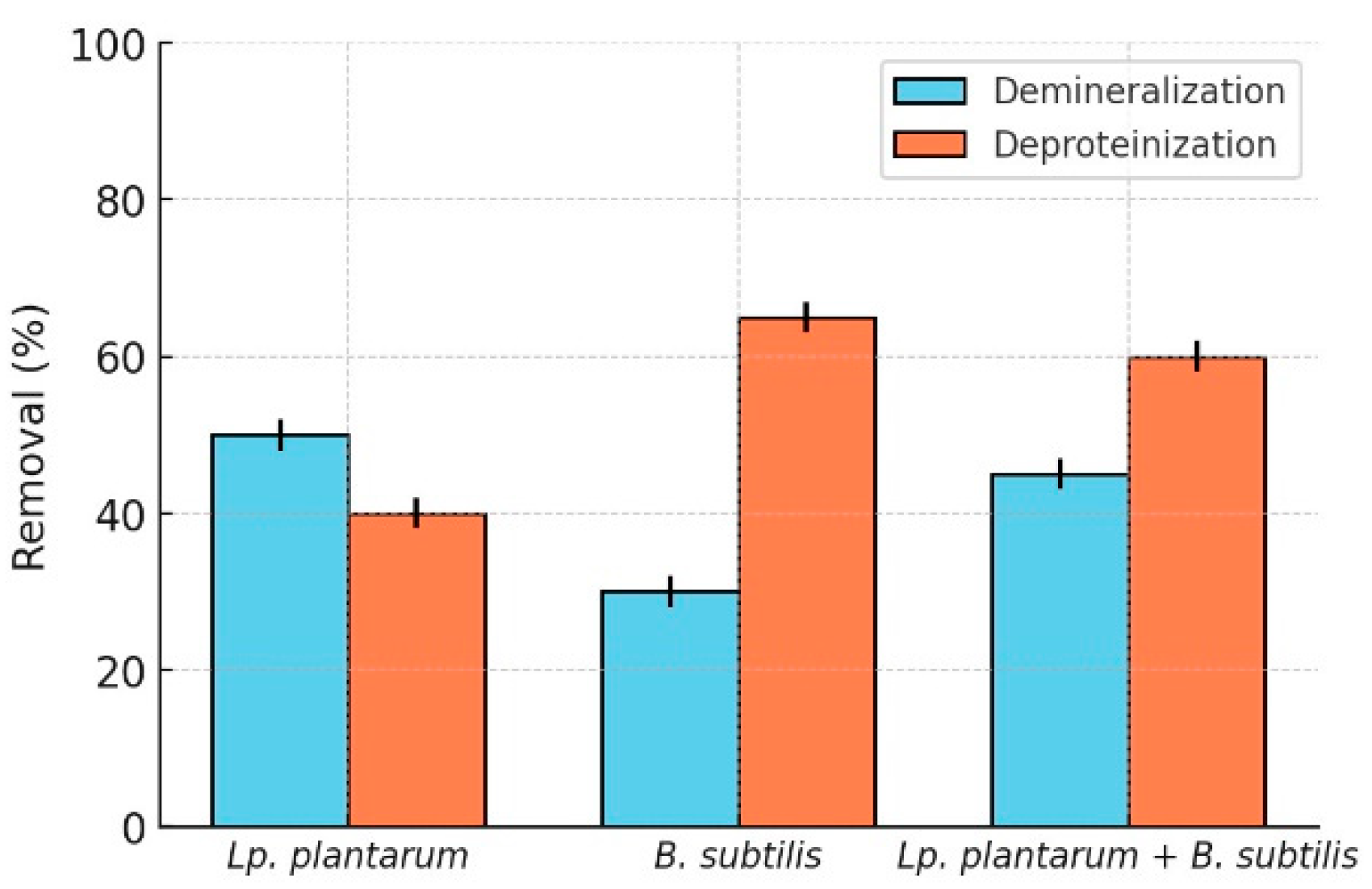

Our extraction process is divided into two main processes, which are entirely carried out by bacteria: the first phase consists in demineralization and the second phase is a deproteinization. We opted for safe bacteria, not dangerous for human health and easily available. In the demineralization phase, the bacterial species Lactobacillus plantarum, plays a crucial role, since it produces organic acids, such as the lactic one, by reacting with calcium carbonate present in large quantities within the shell, according to the following reaction:

CaCo

3+ 2CH

3CHOHCOOH -> Ca(CH

3CHOHCOO)

2+ CO

2+ H

2O. It can easily be observed from the graph [

Figure 1] that

L. plantarum has a more significant role in this first part of the process, unlike the other bacterial species employed in the process:

Bacillus subtilis, which is of greater impact in the second phase of the extraction. In this phase

B. subtilis mainly produces proteases, which break down proteins into smaller peptides that can be easily removed from the mixture, leaving only chitin. In addition, pH adjustments are made to the fermentation broth to ensure an acidic pH and to improve the demineralization process, while maintaining the proper growth of Lactobacillus plantarum and

B. subtilis.

During the process it was also essential to make corrections to the oxygenation, fermentation temperature and the types of nutrients administered to the microorganisms, in order to allow growth of both the bacterial strains in an optimal environment and in a relatively short time.

Methods

As a first step, to remove surface impurities and excess of soft tissue a preliminary cleaning is carried out by washing cycles in demineralized water, followed by a drying process in the oven for 10 hours at 70°C.

The shell is then coarsely ground, this process allowes maximum reaction yield and optimises the contact surface. Subsequently, the raw product obtained is introduced into a specially designed bioreactor where the biotransformation phase begins. Inside the reactor there is the broth (Lactose Broth), and an addition of peptone as a nutrient for bacterial growth, then the pH is adjusted to about 6.5 using an acid solution. This pH values is optimal for the enzymatic activity of microorganisms. The temperature is constantly monitored and maintained between (34-37)°C and glucose is added to provide energy to support the metabolic activity of microorganisms.

When bacteria consume glucose by glycolysis, they produce ATP, which is the basic unit of cellular energy.

The energy produced in this process allows the synthesis of essential molecules for bacterial growth, such as nucleotides, fatty acids, proteins and other cellular molecules. Moreover, glucose influences bacterial metabolism by regulating gene expression and promoting the production of enzymes and other factors involved in the growth and survival of bacterial cells.

The addition of Lactobacillus plantarum as a fermentation agent allows the start of the first fermentation phase (demineralisation). During this phase, which lasts 4 days, the system is constantly oxygenated and stirred to ensure proper mixing of the reagent and a uniform distribution of nutrients and microorganisms within the bioreactor.

After 4 days, the second bacterial species - Bacillus subtilis - is added to the reactor, to start the deproteinization phase. Additional broth is also incorporated to provide the newly added bacteria with enough nutrients. This bacterial species, owns specific metabolic capacities, that contributes significantly to the conversion of the initial substrate into the desired compounds. During this second four-day phase a series of biochemical reactions occur, culminating in the formation of the desired compounds.

After this biotransformation phase, the resulting compound is subjected to a purification process to ensure that the final product is of high purity and quality. This process includes additional washing in distilled water and the extraction of pigments (carotenoids) through a treatment with ethyl alcohol. At the completion of this process the product is dried at 40°C for about 20 hours to ensure a complete removal of residual humidity.

Result

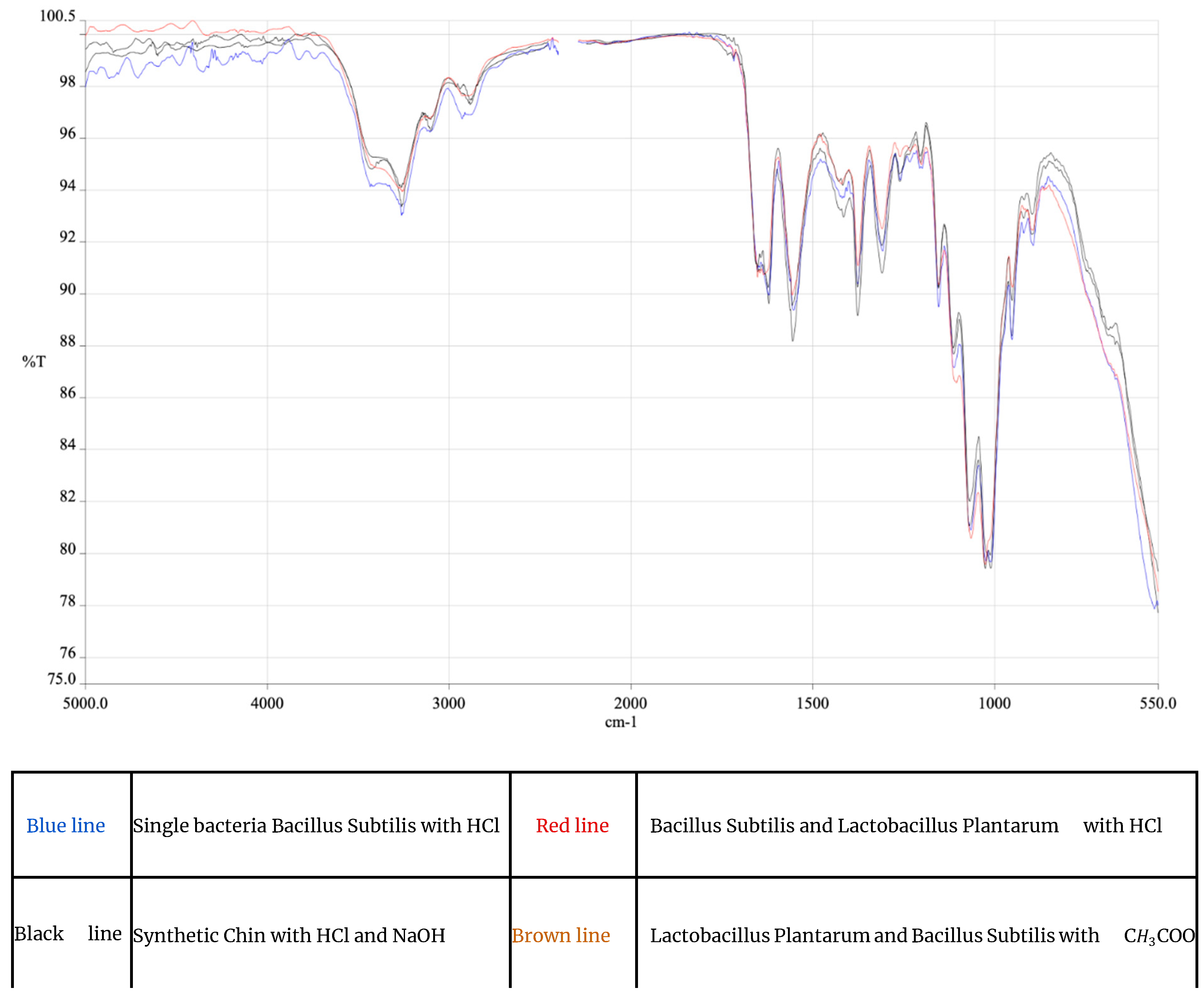

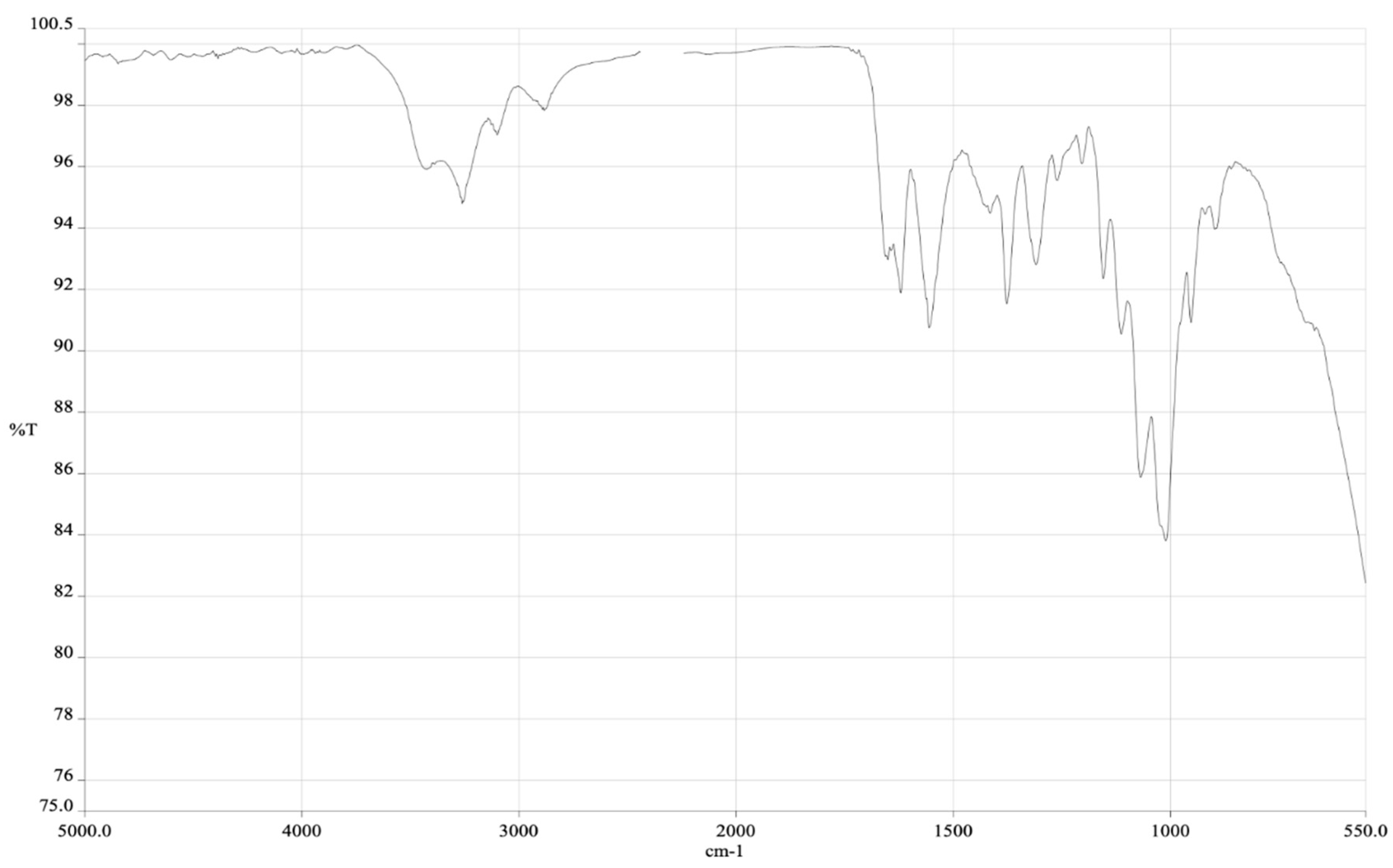

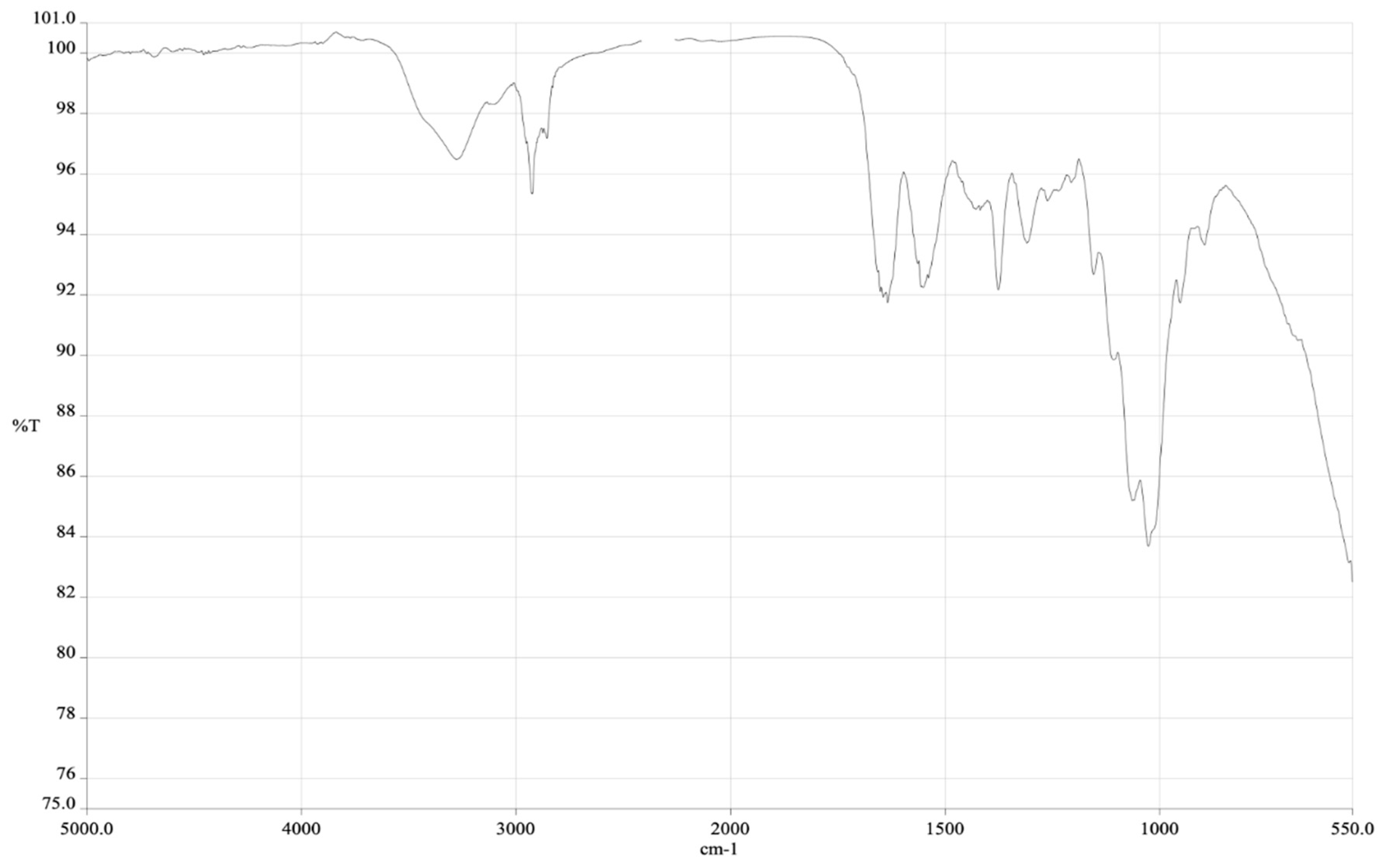

The final sample was analyzed by IR spectrophotometry [

Figure 2]. A comparison was carried out between samples obtained by different extraction methodologies:

1) A biological process which employed a single bacterial species (Bacillus subtilis) followed by a HCl 0,1 M treatment for 6 hours,

2) A biological process which employed two different bacterial species ([

1] Bacillus subtilis and [

2] Lactobacillus plantarum) followed by a treatment with HCl for 6 hours,

3) A process that employed the same two different bacterial species but in reverse order ([

1] Lactobacillus plantarum and [

2] Bacillus subtilis) with a subsequent treatment in diluted CH

3COOH for 12 hours,

4) A chemical process carried out only with NaOH and HCl, with a duration of 6 hours per phase, to replicate what is reported in literature.

All the processes mentioned above were followed by a final purification of the obtained chitin with pure ethyl alcohol to ensure the remotion of any pigment residues (the alcohol was then distilled and the pigments were used for secondary tests). As a result of these analyses, it was possible to compare the effectiveness of the aforementioned processes used for the extraction of chitin, in relation to their environmental impact. The observation focused on the discrepancies of characteristic peaks likely caused by possible impurities or incomplete states of demineralization or deproteinization. Initially it was observed how the demineralization phase had more variations compared to deproteinization. Given that,

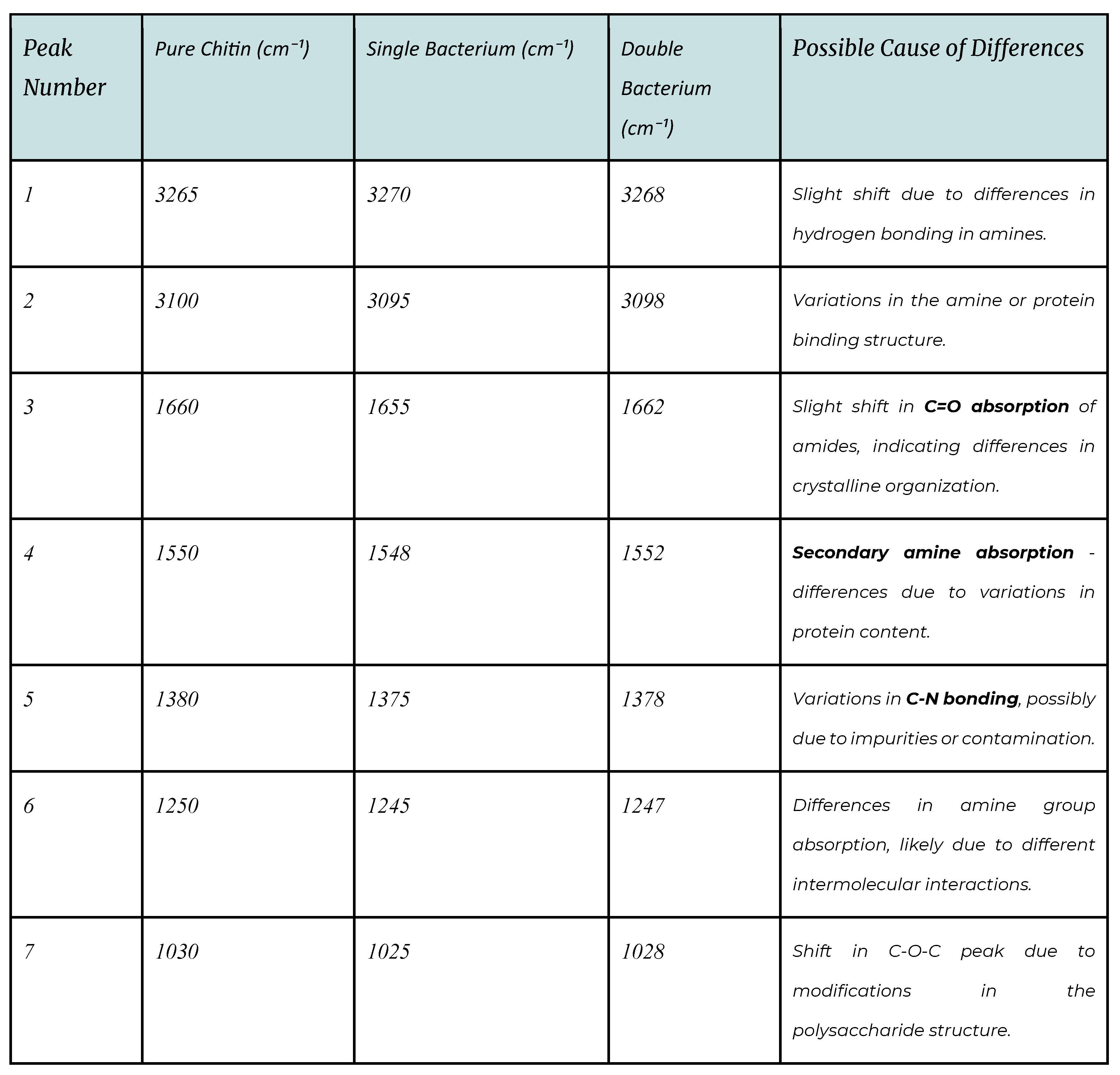

we focused our approach to wards improving the effectiveness of demineralization through the use of specific bacteria such as Lactobacillus plantarum, the manipulation of pH and changes in the properties of the culture medium improving performance and reducing residual carbonates present in the final product. Comparing the IR analyses, a promising similarity in the spectrum was found, with significant changes in some molecular characteristics. Peaks obtained are discussed in detail in [

Figure 3] and in the graph below [

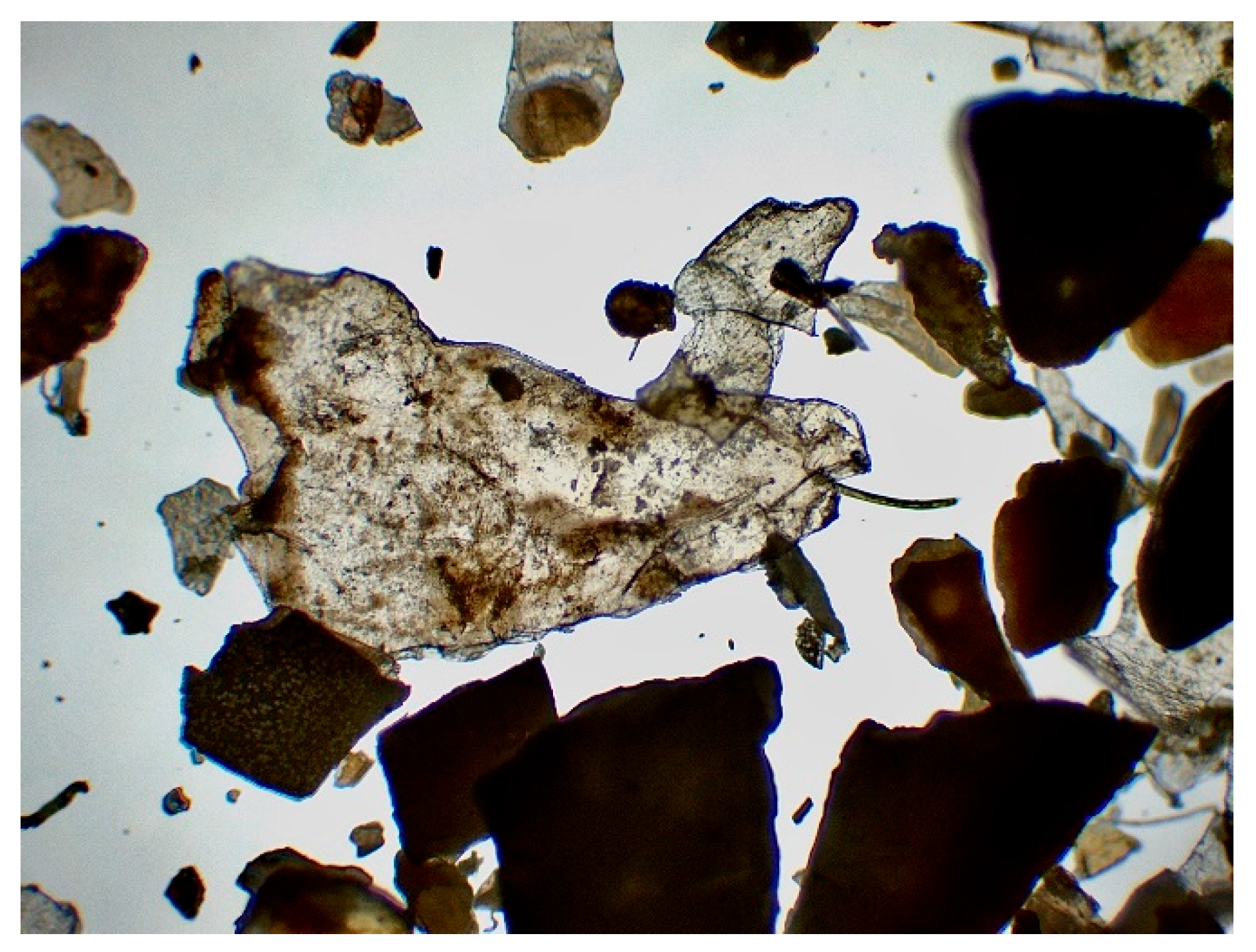

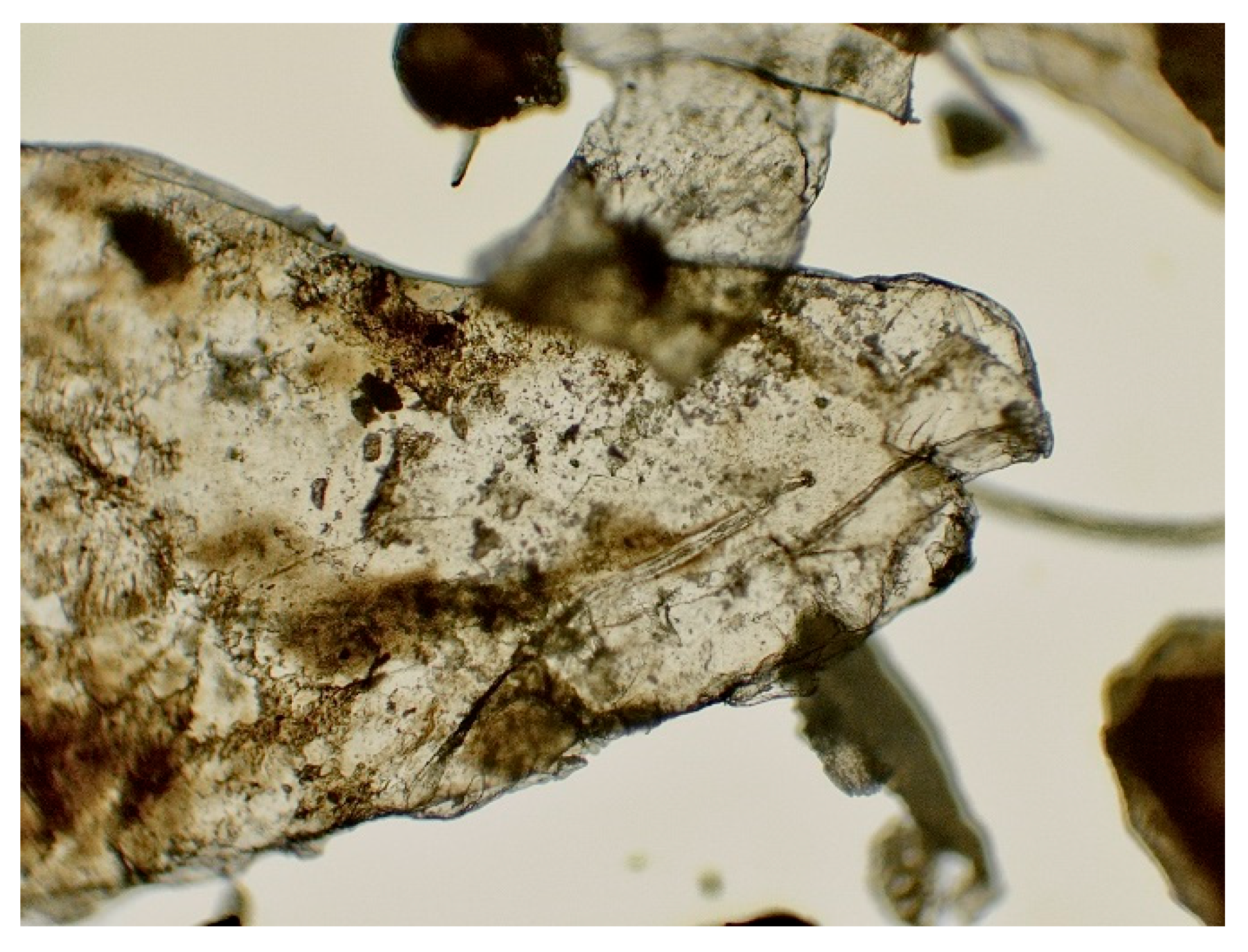

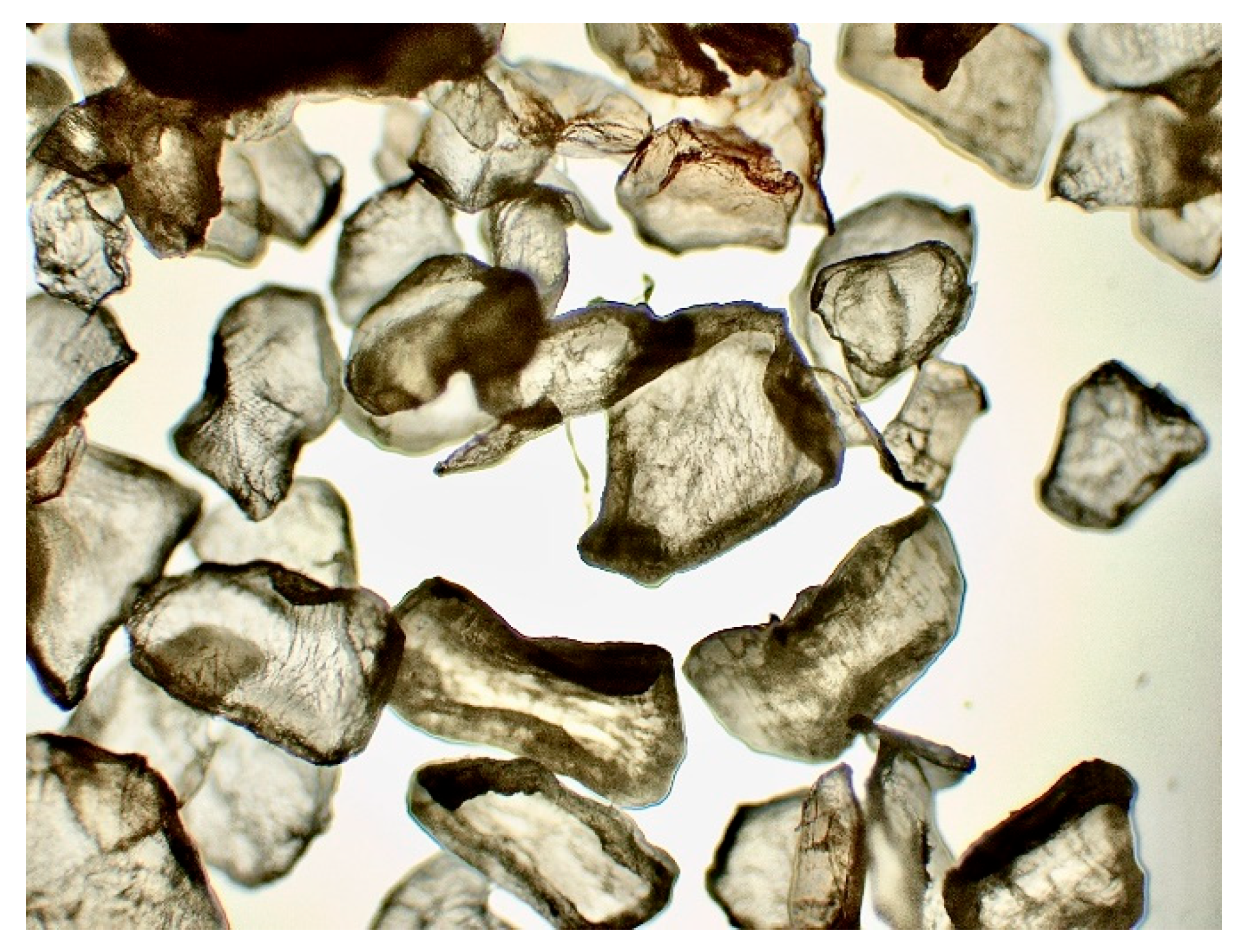

Figure 4]. In conclusion it was possible to observe different molecular structures through an approximate microscopic observation of the chitin obtained with the four different methods, [

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12].

Impurities

As a result of the synthesis, impurities may be found in the extracted chitin due to the extraction process itself and the chemical reagents used. These impurities can affect the intensity and bandwidth of some peaks in the IR spectrum, thus making direct comparison with pure chitin less accurate. In our analyses, we have always used controlled quantities of chemical reagents to ensure the eco-sustainability of the project. [

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4]. Potential impurities could include protein fragments, mineral salts, pigments and other organic compounds present in the blue crab shell. The presence of impurities could be confirmed by complementary analytical techniques such as Raman spectroscopy, chromatography, or elemental analysis. Since these impurities might interfere with potential specific applications of the final product, the project is focused on the optimization of the process, to achieve a final product with high-purity standards.

Differences in Crystal Structure

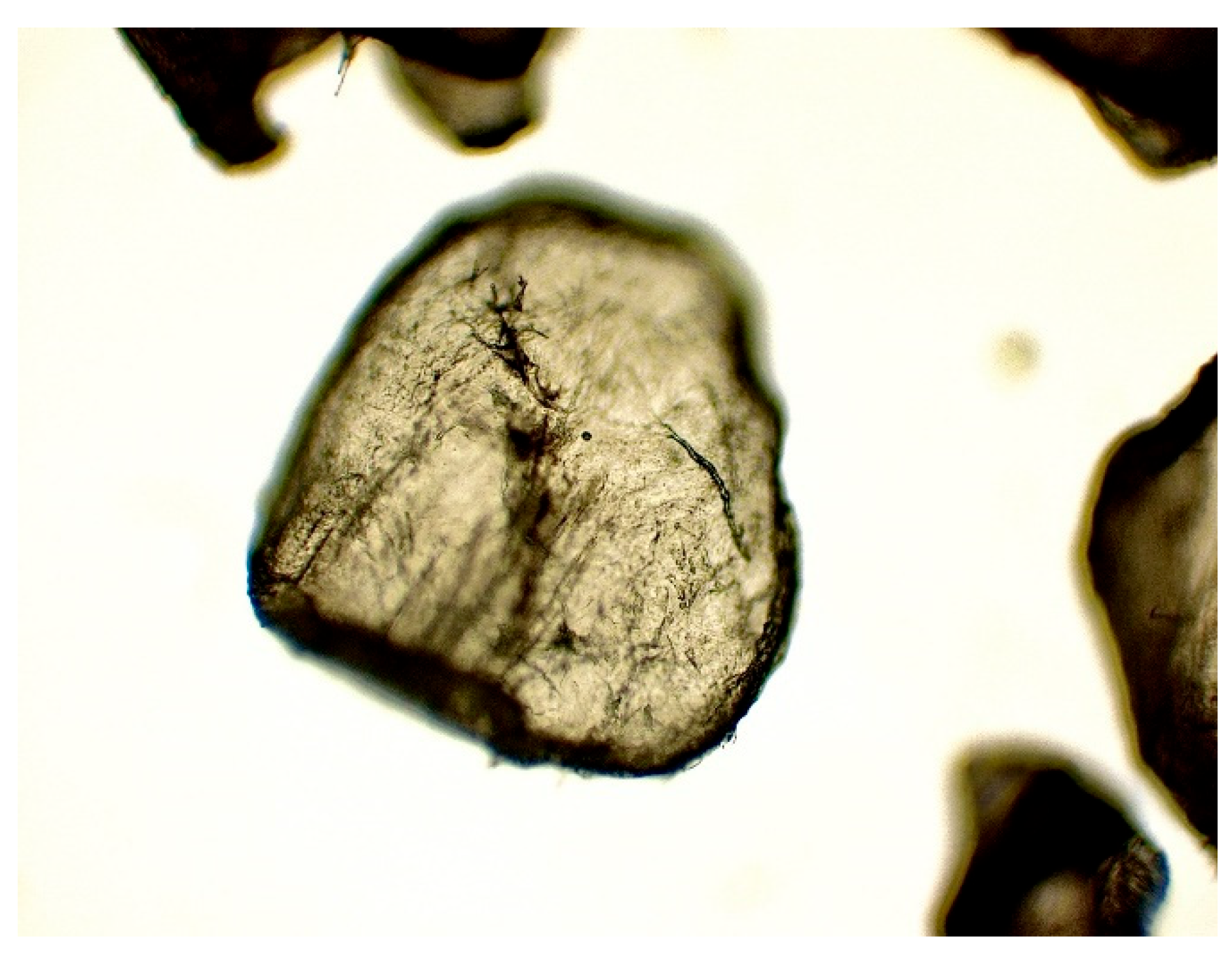

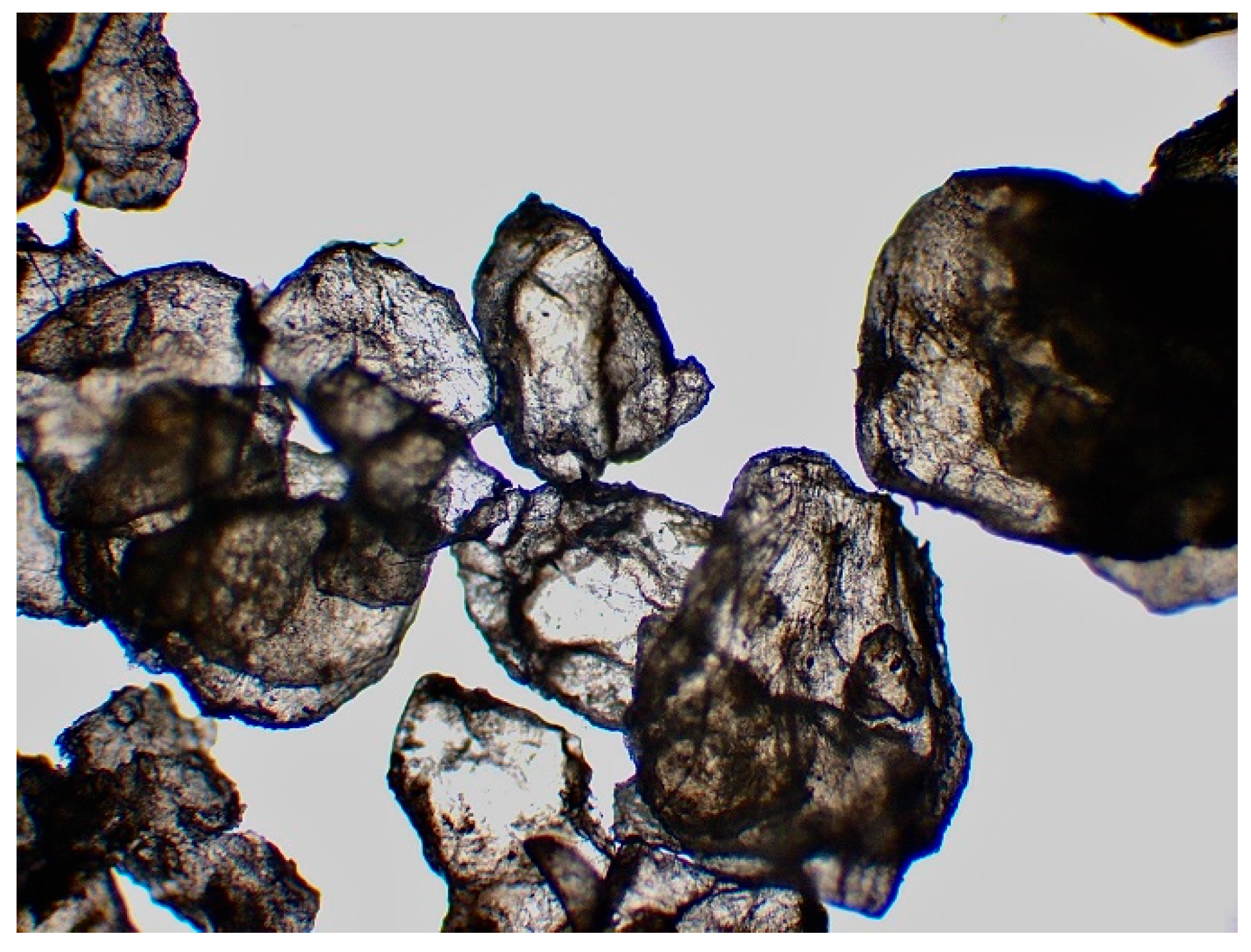

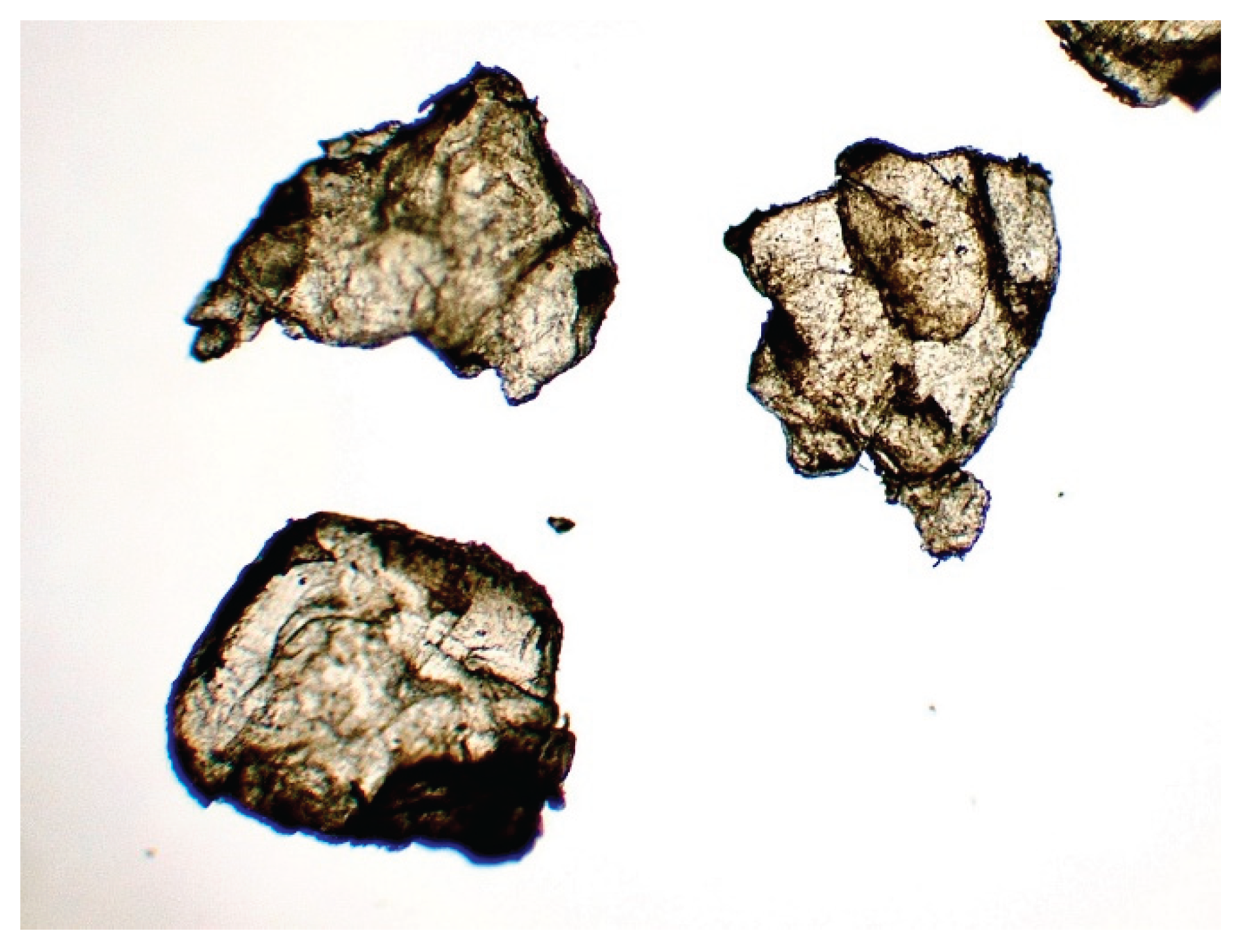

The deproteinization and demineralization processes used in the synthesis of chitin may have caused degradation of the polymeric chain. This degradation can result in a decrease in the intensity of the β-1,4 glycosidic bond peak (895 cm⁻¹) when analysed with the IR spectrum as observed in this case. On the other hand the presence of degradation may depend on various factors such as temperature, reaction time and pH conditions-parameters that can vary across different deacetylation and decarbonization processes. Furthermore biologically produced chitin can exhibit significant structural variations compared to the chemically synthesized one. These differences can be observed through various analytical methods. For this study we utilized infrared (IR) spectrophotometry to assess differences between biologically extracted chitin and a chemically purified sample. These variations affect the intensity and bandwidth of certain peaks in the IR spectrum. The final polymeric chain structure is crucial, as it determines the primary chemical and physical properties for potential applications. Therefore, a detailed study of the chitin's molecular structure is essential to identify the most suitable uses for the obtained raw material. Techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) or investigations using an optical microscope, [

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12] can be employed to examine the crystal structure of the synthesized chitin.

Figure 5.

Characteristic peak comparison chart.

Figure 5.

Characteristic peak comparison chart.

Figure 6.

The graph highlights the distances and the trend of the peaks within the analysis.

Figure 6.

The graph highlights the distances and the trend of the peaks within the analysis.

Figure 7.

Crab shell under microscope x4.

Figure 7.

Crab shell under microscope x4.

Figure 8.

Crab shell under microscope x10.

Figure 8.

Crab shell under microscope x10.

Figure 9.

Synthetic chitin under a microscope x4.

Figure 9.

Synthetic chitin under a microscope x4.

Figure 10.

Synthetic chitin under a microscope x10.

Figure 10.

Synthetic chitin under a microscope x10.

Figure 11.

Microbiological under a microscope x4.

Figure 11.

Microbiological under a microscope x4.

Figure 12.

Microbiological chitin under a microscope x10.

Figure 12.

Microbiological chitin under a microscope x10.

Conclusion

Following the extraction of chitin from the blue crab exoskeleton and its spectrophotometry analysis, it can be observed how the production of chitin through bacterial fermentation results more environmentally sustainable compared to the chemical extraction. However, structural chemical-physical changes directly caused by the different production processes were identified. Variations in various peaks of the FT-IR graphs were observed, most likely caused by enzyme activity and the specific environmental conditions within the bioreactor. Significant changes in the amino functional groups and the carbonyl (C=O) groups, particularly around 1660 cm⁻¹, suggest that crystalline alterations could be the potential result of interactions between different enzymes in the bioreactor, thereby introducing variations in the levels of deacetylation and decarbonization of the final product. Changes in the peaks were associated with C-N and C-O-C bonds; they were respectively observed at approximately 1380 cm⁻¹ and 1030 cm⁻¹, indicating possible interactions with bacterial metabolites. The aforementioned variations highlight the molecular adaptability of the biopolymer to biological treatments. Additionally, images captured using optical microscopy reveal variations in the texture of the final product, with bacterial chitin showing a more wrinkled texture compared to the smoother appearance of chemically produced chitin, indicating a difference in crystallization. A key objective in this research was optimizing the process from an ecological perspective, aiming for minimal environmental impact. The production of chitin through bacterial processes is easily reproducible and cost-effective, due to the rapid reproduction rate of the bacterial species involved in the process. In addition to that, the process is highly sustainable, since it leverages reactions that naturally occur in bacterial metabolism. In contrast to this production method, large-scale industrial chitin extraction relies on highly polluting chemical reagents; laboratory evidence shows that purifying approximately 5g of chitin utilizing chemical solvents requires not only over 200 ml of NaOH and an additional 200 ml of HCl, but also larger quantities of water, used to eliminate excess reagents in multiple washes. On the other hand, the microorganisms can produce multiple chitin stocks, resulting in a much more economical and ecological production, with minimal product waste. While limited in several aspects, this research aims to provide a tangible demonstration of how an environmental emergency that causes significant damage to both regional biodiversity and the economy can be intelligently and innovatively repurposed. As the second most abundant biopolymer on Earth after cellulose, chitin is a fundamental resource in multiple sectors and should not be wasted. With current technologies, we can exploit this resource in extremely eco-sustainable ways.

Idea Behind Our Work

During the last year of our Technical High School “N. Baldini”, we studied polymers and their applications from a chemical, biological, and industrial perspective. In the civic education course, we also explored the UN Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development, how to prevent waste, and the 3Rs (reduce, reuse, recycle) of the circular economy. Chitin (C8H13O5N)n is the second most abundant biopolymer on Earth after cellulose. Chitin and chitosan have high economic value due to their biodegradability, biocompatibility, and non-toxicity. Many fishermen in the Mediterranean, especially the Adriatic Sea, have reported that the Blue Crab is harming their catch. This omnivorous species feeds on fish, crustaceans, molluscs, and plant matter, threatening marine biodiversity. Literature shows that shrimp shells can be used to make bioplastics by simply adding vinegar, and chitin has also been chemically extracted from crabs. However, there is no standardized protocol: solvent concentrations and timing (especially for HCl and NaOH) vary across studies. Based on this, we aimed to reproduce chitin extraction in the school lab using a biological method.

References

- Chitin and Chitosan: Science and Engineering: Shameem Hasan, Veera M. Boddu, Dabir S. Viswanath, Tushar K. Ghosh.

- Chitin- and Chitosan-Based Biocomposites for Food Packaging Applications: Jissy Jacob (Editor); Sravanthi Loganathan (Editor); Sabu Thomas (Editor).

- Chitin : fulfilling a biomaterials promise: Eugene Khor.

- Handbook of Chitin and Chitosan: Volume 1: Preparation and Properties Sabu Thomas (editor), Anitha Pius (editor), Sreerag Gopi (editor).

- Starch, Chitin and Chitosan Based Composites and Nanocomposites: Merin Sara Thomas, Rekha Rose Koshy, Siji K. Mary, Sabu Thomas, Laly A. Pothan.

- lChitin and Chitosan: Properties and Applications: Lambertus A. M. van den Broek, Carmen G. Boeriu, Christian V. Stevens.

- Advances in Chitin-Chitosan Characterization and Applications: Marguerite Rinaudo, Francisco M. Goycoolea.

- Extraction, characterization, and nematicidal activity of chitin and chitosan derived from shrimp shell wastes: Mohamed A. Radwan, Samia A. A. Farrag, Mahmoud M. Abu-Elamayem, Nabila S. Ahmed. [CrossRef]

- Optimization of Chitin Extraction from Shrimp Shells: Percot, Aline, Viton, Christophe, Domard, Alain. [CrossRef]

- Characterization of chitin and chitosan extracted from shrimp shells by two methods: Gartner, Carmiña, Peláez, Carlos Alberto, López, Betty Lucy. [CrossRef]

- Physicochemical characterization of chitin and chitosan from crab shells: Ming-Tsung Yen, Joan-Hwa Yang, Jeng-Leun Mau. [CrossRef]

- Chitin extraction from shrimp shell waste using Bacillus bacteria: Olfa Ghorbel-Bellaaj, Islem Younes, Hana Maâlej, Sawssen Hajji, Moncef Nasri. [CrossRef]

- Chitin extraction from crab shells by Bacillus bacteria. Biological activities of fermented crab supernatants: Hajji, Sawssen, Ghorbel-Bellaaj, Olfa, Younes, Islem, Jellouli, Kemel, Nasri, Moncef. [CrossRef]

- Easy production of chitin from crab shells using ionic liquid and citric acid: Tatsuya Setoguchi, Takeshi Kato, Kazuya Yamamoto, Jun-ichi Kadokawa. [CrossRef]

- Production of Chitin and Chitosan from Shrimp Shell Wastes Using Co- Fermentation of Lactobacillus plantarum PTCC 1745 and Bacillus subtilis PTCC 1720. [CrossRef]

- Extraction of chitin from red crab shell waste by cofermentation with Lactobacillus paracaseisubsp.toleransKCTC-3074 andSerratia marcescensFS-3: W. J. Jung, G. H. Jo, J. H. Kuk, K. Y. Kim, R. D. Park. [CrossRef]

- A new method for fast chitin extraction from shells of crab, crayfish and shrimp: Kaya, Murat, Baran, Talat, Karaarslan, Muhsin. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).