Submitted:

01 June 2025

Posted:

02 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- How aware are the stakeholders of the benefits of passive energy-efficient retrofitting of residential buildings in Lagos State, Nigeria?

- What dimensions of the benefits do the stakeholders consider important?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Environmental Benefits

2.2. Economic Benefits

2.3. Social Benefits

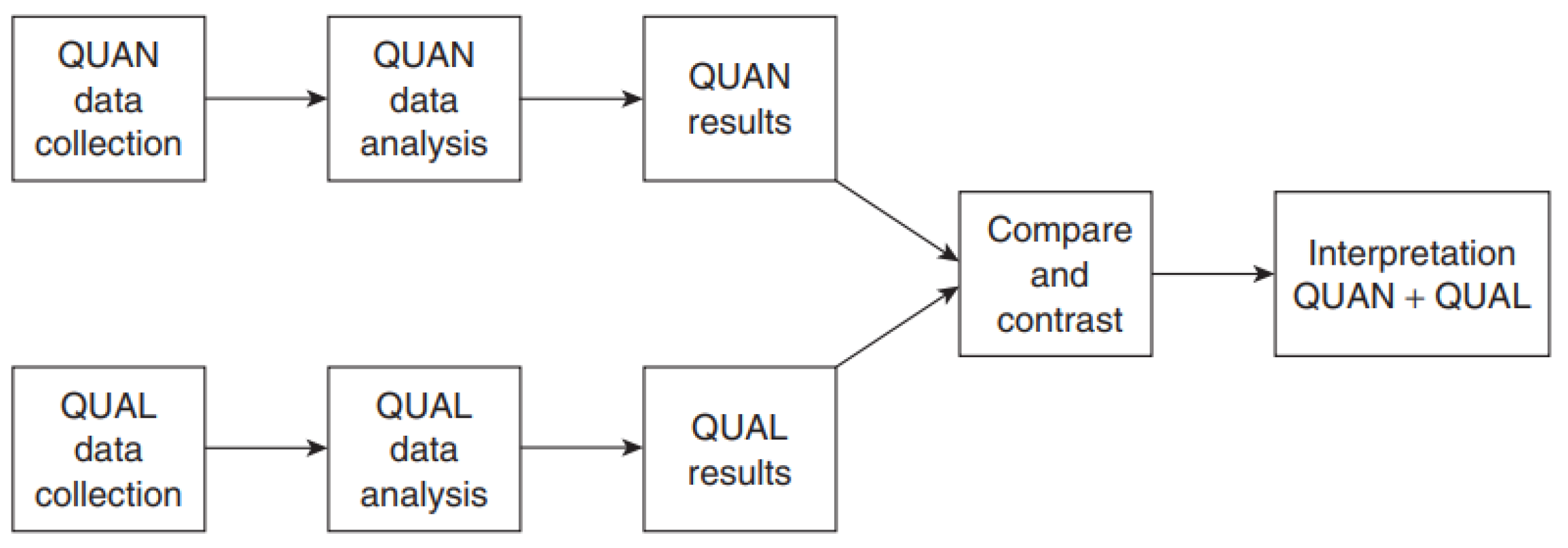

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Analysis

3.2.1. FSE

- Step 1: Definition of the factor set.

3.2.2. Thematic Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Quantitative Results

4.1.1. Reliability of Data

4.1.2. Stakeholders’ Awareness of the Benefits of Passive Energy-Efficient Retrofitting

- Environmental Dimension

- Economic Dimension

- Social Dimension

- General Awareness Among Property Managers

4.1.3. FSE Results from Owners’ Perspective

- Environmental Dimension

- Economic Dimension

- Social Dimension

- General Awareness Among Owners

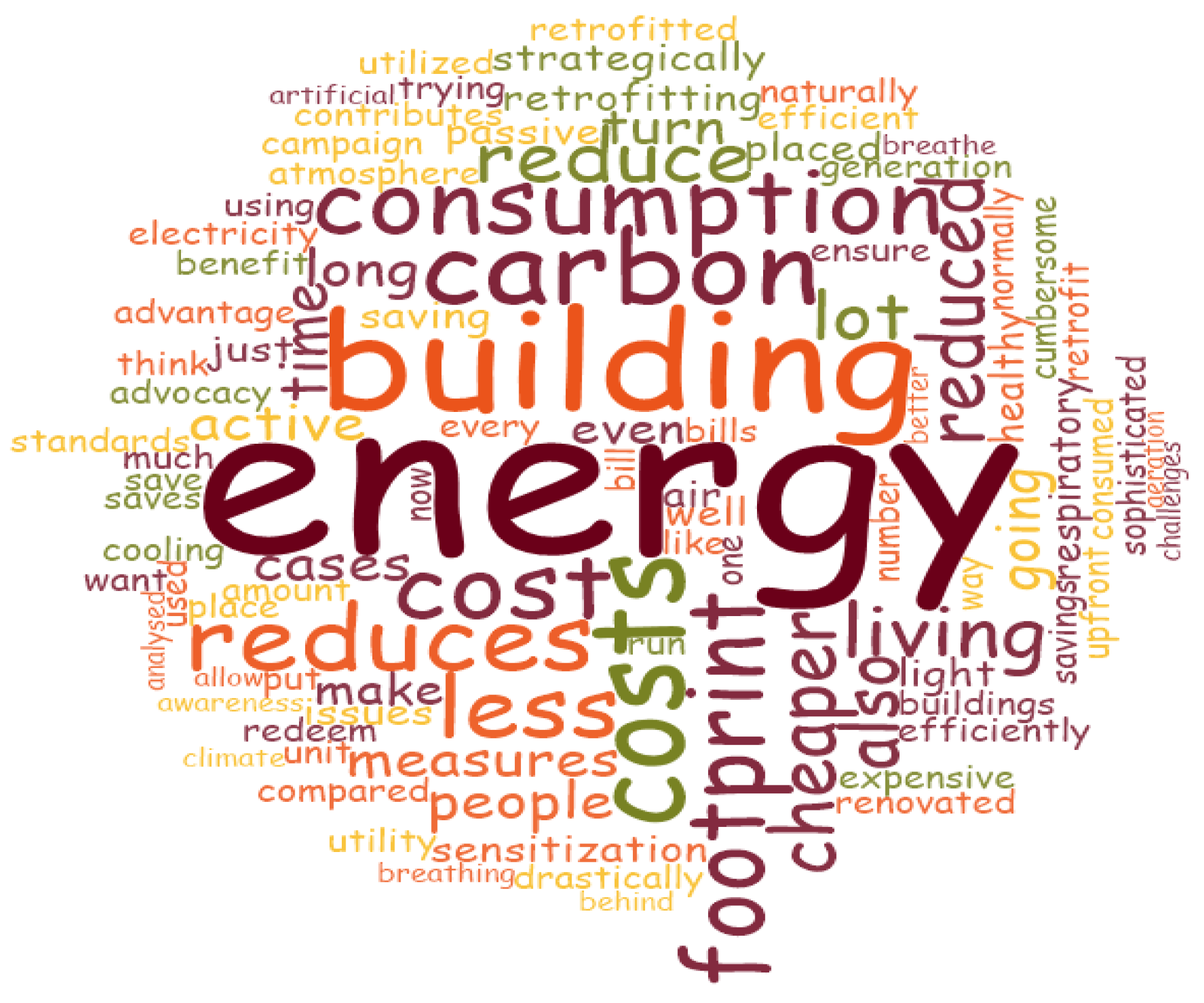

4.2. Qualitative Results

4.2.1. Environmental Benefits of Passive Energy-Efficient Retrofitting

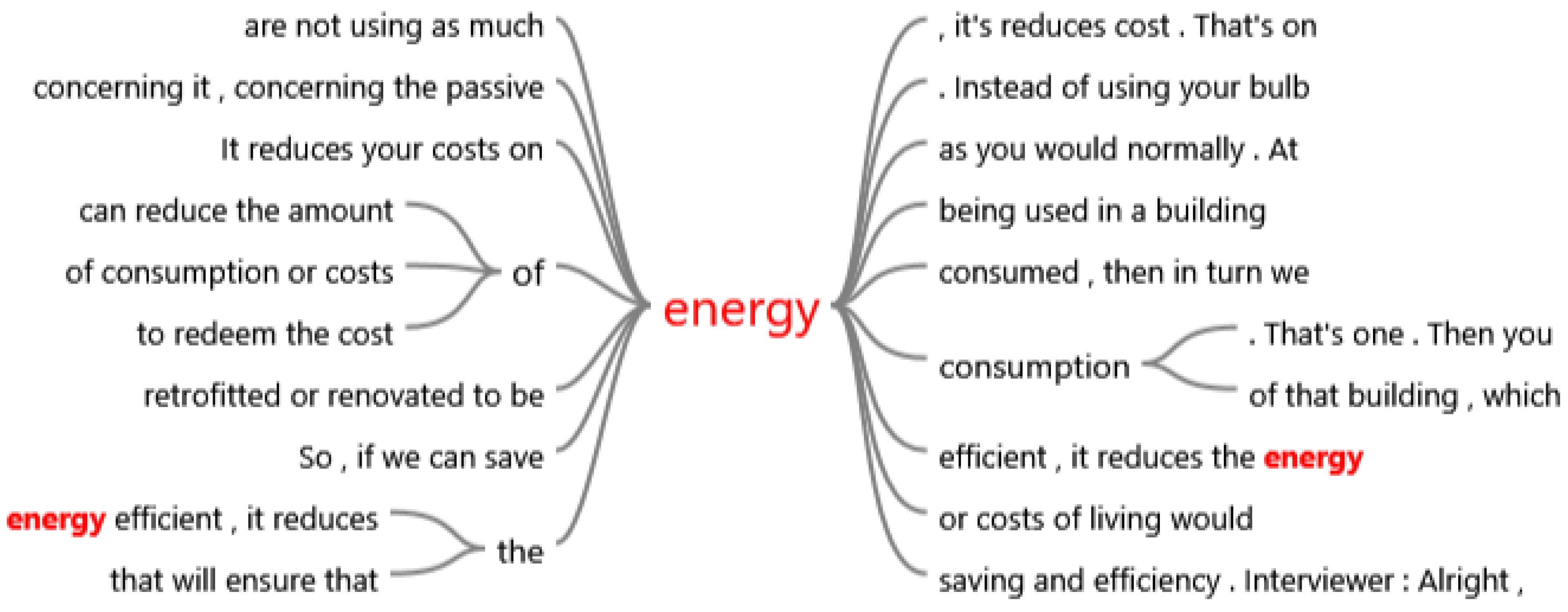

- Reduction in Energy Consumption and Carbon Footprint

“Passive retrofitting would put in place standards and measures that will ensure that the energy being used in a building is efficiently utilised.”[LAS001]

“If we can reduce the amount of energy consumed, then in turn we can reduce the carbon footprint of that building. The carbon footprint of that building is reduced because generation of electricity also contributes to carbon footprint.”[LAS005]

“You are naturally trying to have less carbon footprint just going to the atmosphere.”[LAS001]

- Climate Resilience

- Heat Management

“Your roofing style. Now you want to dissipate heat quickly from your house instead of the heat affecting your room.”[LAS002]

- Natural Lighting and Ventilation

- Reduced Dependency on Power Generator

“To the barest minimum, you don't need to use your power-generating sets.”

4.2.2. Economic Benefits of Passive Energy-Efficient Retrofitting

- Energy Cost Savings

“It would go a long way in saving costs in the long run because if you are not using as much energy as you would normally.”[LAS001]

- Lower Implementation Costs

“It’s a lot cheaper than the active measures.”

- Feasibility

“Many things that you’d do are within your capacity.”[LAS003]

4.2.3. Social Benefits of Passive Energy-Efficient Retrofitting

- Air Quality Improvement and Indoor Comfort

“The less time we use those artificial interventions, the better for us because of the air we will be breathing in.”[LAS003]

- Health Improvement

“It would also promote healthy living because we're looking at reducing carbon emissions as well.”[LAS001]

“The less time we use those artificial interventions, the better for us because of the air we will be breathing in. Even for some cases of respiratory tract infections or respiratory issues, there have been cases of people sleeping in tenements with their generator set behind their windows. And they have reports, cases of a medical challenge that by the time they are analysed (diagnosed) in the hospital, they’d be told to shift the location of their generating sets that pollute the air they breathe in directly.”

“And then to make the people living there to be healthy so that they will be free from some health issues.”

“Even people that are living in my environment, some of them are complaining of that heat.”[LAS006]

4.3. Promotion of Awareness

"there's a PAU unit that's in charge of advocacy and sensitisation . . . the sensitisation is still on, but it's not as expected for now" .[LAS003]

"They've a lot of campaign and since we are talking of the existing building now, I think what they are doing is just like sensitisation, education, and advocacy for now on the issue of retrofitting, and some lectures and seminars on it . . . on the issue of advocacy and seminar, they are doing well, but you know, they still need to do more."

"We did a demonstration of National Building Code for Lagos State and energy efficiency is a major focus in it" .[LAS003]

"I'm believing that by the time they commence the construction of that building, there will be lots of more awareness to be created, even within the internal stakeholders, that means the civil servants themselves, then the general public" .[LAS003]

4.4. Results Integration and Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Capeluto, I.G. The Unsustainable Direction of Green Building Codes: A Critical Look at the Future of Green Architecture. Buildings 2022, 12, 773. [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, C. Linking Energy Use to Local Climate. Nat Energy 2023, 8, 1311–1312. [CrossRef]

- Ikechukwu, N.C. Electricity Tariff Hike And Economic Implications On Nigerians. Within Nigeria. Available online: https://www.withinnigeria.com/2024/04/28/electricity-tariff-hike-and-economic-implications-on-nigerians/.

- Akinbode, O.M.; Eludoyin, A.O.; Fashae, O.A. Temperature and Relative Humidity Distributions in a Medium-Size Administrative Town in Southwest Nigeria. J Environ Manage 2008, 87, 95–105. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, S.; Svendsen, S. Method and Simulation Program Informed Decisions in the Early Stages of Building Design. Energy Build 2010, 42, 1113–1119. [CrossRef]

- Pepple, D.G. & Pokubo, D. Nigerian Households Use a Range of Energy, from Wood to Solar – Green Energy Planning Must Account for This. Available online: https://theconversation.com/nigerian-households-use-a-range-of-energy-from-wood-to-solar-green-energy-planning-must-account-for-this-237491.

- Beavor, A., Khan, S., Makarem, N., Obasiohia, B.O., Oketa, N.J., & Fernandes, P.A. Financing Net Zero Carbon Buildings in Nigeria. Available online: https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Financing-Net-Zero-Carbon_Full-Report.pdf.

- Peiris, S.; Lai, J.H.K.; Kumaraswamy, M.M.; Hou, H. (Cynthia) Smart Retrofitting for Existing Buildings: State of the Art and Future Research Directions. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 76, 107354. [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Smart Growth and Preservation of Existing and Historic Buildings. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/smart-growth-and-preservation-existing-and-historic-buildings#:~:text=A new%2C green%2C energy-efficient office building that includes, lost in demolishing a comparable existing building. 1.

- Sasu, D.D. Amount of Electricity Consumed in Nigeria as of 2022, by Sector (in Terajoules). Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1307456/electricity-consumption-in-nigeria-by-sector/.

- Quintana, D.I.; Cansino, J.M. Residential Energy Consumption-A Computational Bibliometric Analysis. Buildings 2023, 13, 1525. [CrossRef]

- Xi, T.; Sa’ad, S.U.; Liu, X.; Sun, H.; Wang, M.; Guo, F. Optimization of Residential Indoor Thermal Environment by Passive Design and Mechanical Ventilation in Tropical Savanna Climate Zone in Nigeria, Africa. Energies (Basel) 2025, 18, 450. [CrossRef]

- Adegoke, A.S.; Abidoye, R.B.; Sunindijo, R.Y. A Bibliometric Analysis and Scoping Review of the Critical Success Factors for Residential Building Energy Retrofitting. Buildings 2024, 14, 3989. [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Airaksinen, M.; Lahdelma, R. Attitudes and Approaches of Finnish Retrofit Industry Stakeholders toward Achieving Nearly Zero-Energy Buildings. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7359. [CrossRef]

- Gherri, B.; Cavagliano, C.; Orsi, S. Social Housing Policies and Best Practice Review for Retrofit Action - Case Studies from Parma (IT). IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2017, 245, 082038. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M. Benefits of Greening Existing Buildings. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2019, 615, 012033. [CrossRef]

- Altmann, E. Apartments, Co-Ownership and Sustainability: Implementation Barriers for Retrofitting the Built Environment. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2014, 16, 437–457. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, C.; Becker, N.; Erell, E. Retrofitting Residential Building Envelopes for Energy Efficiency: Motivations of Individual Homeowners in Israel. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2018, 61, 1805–1827. [CrossRef]

- Djebbar, K.E.-B.; Mokhtari, A. Evaluation of the Level of Awareness of the Inhabitants on the Importance of the Energy Retrofitting of Buildings: Case Study of Tlemcen (Algeria). International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation 2025, 43, 209–256. [CrossRef]

- Ab. Azis, S.S., Sipan, I. & Sapri, M. Malaysian Awareness and Willingness towards Retrofitted Green Buildings: Community. In Proceedings of the 25th International Business Information Management Association Conference - Innovation Vision 2020: From Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth; Amsterdam, Netherlands., 2015.

- Alfaiz, S.K.; Abd Karim, S.B.; Alashwal, A.M. Critical Success Factors of Green Building Retrofitting Ventures in Iraq. International Journal of Sustainable Construction Engineering and Technology 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Pajek, L.; Jevrić, M.; Ćipranić, I.; Košir, M. A Multi-Aspect Approach to Energy Retrofitting under Global Warming: A Case of a Multi-Apartment Building in Montenegro. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 63, 105462. [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Lu, S.; Wu, Y. A Review of Building Energy Efficiency in China during “Eleventh Five-Year Plan” Period. Energy Policy 2012, 41, 624–635. [CrossRef]

- Ojelabi, R.A.; Mohammed, T.A.; Oladiran, O.J. Awareness and Implementation Challenges of the Green Retrofitting in Building Enclosure in the Nigerian Construction Industry. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2024, 1342, 012023. [CrossRef]

- Oke, O.S.; Aliu, J.O.; Duduyegbe, O.M.; Oke, A.E. Assessing Awareness and Adoption of Green Policies and Programs for Sustainable Development: Perspectives from Construction Practitioners in Nigeria. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2202. [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks : The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business.; Oxford: Capstone, 1997;

- Fei, W.; Opoku, A.; Agyekum, K.; Oppon, J.A.; Ahmed, V.; Chen, C.; Lok, K.L. The Critical Role of the Construction Industry in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Delivering Projects for the Common Good. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9112. [CrossRef]

- Fuerst, F.; McAllister, P. Green Noise or Green Value? Measuring the Effects of Environmental Certification on Office Values. Real Estate Economics 2011, 39, 45–69. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Shen, G.; Guo, L. Improving Management of Green Retrofits from a Stakeholder Perspective: A Case Study in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015, 12, 13823–13842. [CrossRef]

- Coyne, B.; Lyons, S.; McCoy, D. The Effects of Home Energy Efficiency Upgrades on Social Housing Tenants: Evidence from Ireland. Energy Effic 2018, 11, 2077–2100. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Valentin, V. An Optimization Framework for Building Energy Retrofits Decision-Making. Build Environ 2017, 115, 118–129. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Lai, J. Environmental and Economic Evaluations of Building Energy Retrofits: Case Study of a Commercial Building. Build Environ 2018, 145, 14–23. [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, J.; Saari, A.; Jokisalo, J.; Kosonen, R. Socio-Economic Impacts of Large-Scale Deep Energy Retrofits in Finnish Apartment Buildings. J Clean Prod 2022, 368, 133187. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A., Valentin, V., Howe, K., & Russell, M.M. Environmental Impact of Housing Retrofit Activities: Case Study.; World Sustainable Building (WBS): Barcelona, Spain, 2014.

- Kabeyi, M.J.B.; Olanrewaju, O.A. Sustainable Energy Transition for Renewable and Low Carbon Grid Electricity Generation and Supply. Front Energy Res 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Hurley, D., Takahashi, K., Biewald, B., Kallay, J., and Maslowsk, R. Costs and Benefits of Electric Utility Energy Efficiency in Massachusetts. Available online: https://www.synapse-energy.com/sites/default/files/SynapseReport.2008-08.0.MA-Electric-Utility-Energy-Efficiency.08-075.pdf.

- Crespo Sánchez, E.; López Plazas, F.; Onecha Pérez, B.; Marmolejo-Duarte, C. Towards Intergenerational Transfer to Raise Awareness about the Benefits and Co-Benefits of Energy Retrofits in Residential Buildings. Buildings 2023, 13, 2213. [CrossRef]

- Luddeni, G.; Krarti, M.; Pernigotto, G.; Gasparella, A. An Analysis Methodology for Large-Scale Deep Energy Retrofits of Existing Building Stocks: Case Study of the Italian Office Building. Sustain Cities Soc 2018, 41, 296–311. [CrossRef]

- Alkhateeb, E.; Hijleh, B.A. Potential of Upgrading Federal Buildings in the United Arab Emirates to Reduce Energy Demand. Procedia Eng 2017, 180, 61–70. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.H.; Pearce, A.R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G. Drivers and Barriers of Sustainable Design and Construction: The Perception of Green Building Experience. International Journal of Sustainable Building Technology and Urban Development 2013, 4, 35–45. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F. Introduction to Cost-Effective Energy-Efficient Building. In Cost-effective Energy Efficient Building Retrofitting: Materials, Technologies, Optimization and Case Studies.; J. K. F. Pacheco-Torgal, C.G. Granqvist, B.P. Jelle, G. P Vanoli, N.B. (Eds. ), Ed.; Elsevier: Cambridge., 2017.

- Alcazar, S.S. and Bass, B. (2005). Energy Performance of Green Roofs in a Multi-Storey Residential Building in Madrid.; Green Roofs for Healthy Cities, Toronto, ON (Canada); City of Washington, DC (United States): Canada; pp. 569–582.

- Niachou, A.; Papakonstantinou, K.; Santamouris, M.; Tsangrassoulis, A.; Mihalakakou, G. Analysis of the Green Roof Thermal Properties and Investigation of Its Energy Performance. Energy Build 2001, 33, 719–729. [CrossRef]

- Insulation Council of Australia and New Zealand. The Value of Ceiling Insulation: Impacts Of Retrofitting Ceiling Insulation To Residential Dwellings In Australia. Available online: https://icanz.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/ICANZ-CeilingInsulationReport-V04-1.pdf.

- Oguntona, O.A.; Maseko, B.M.; Aigbavboa, C.O.; Thwala, W.D. Barriers to Retrofitting Buildings for Energy Efficiency in South Africa. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2019, 640, 012015. [CrossRef]

- Shahdan, M.S.; Ahmad, S.S.; Hussin, M.A. External Shading Devices for Energy Efficient Building. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2018, 117, 012034. [CrossRef]

- Clinch, J.P.; Healy, J.D. Cost-Benefit Analysis of Domestic Energy Efficiency. Energy Policy 2001, 29, 113–124. [CrossRef]

- Pivo, G. & Fisher, J. Investment Returns from Responsible Property Investments: Energy Efficient, Transit-Oriented and Urban Regeneration Office Properties in the US from 1998–2008. In Responsible Property Investing Center.; 2009.

- Brounen, D., Kok, N., & Menne, J. Energy Performance Certification in the Housing Market. Implementation and Valuation in the European Union.; European Centre for Corporate Engagement, Maastricht University, Netherlands., 2009.

- Mayer, Z.; Volk, R.; Schultmann, F. Analysis of Financial Benefits for Energy Retrofits of Owner-Occupied Single-Family Houses in Germany. Build Environ 2022, 211, 108722. [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, J. Low Carbon Retrofit Toolkit: A Roadmap to Success. Available online: https://www.betterbuildingspartnership.co.uk/sites/default/files/media/attachment/bbp-low-carbon-retrofit-toolkit.pdf.

- Ferreira, M.; Almeida, M.; Rodrigues, A.; Silva, S.M. Comparing Cost-Optimal and Net-Zero Energy Targets in Building Retrofit. Building Research & Information 2016, 44, 188–201. [CrossRef]

- Falaiye, H. Nigerians Opt for Alternative Energy Sources amid High Fuel Costs. Available online: https://punchng.com/nigerians-opt-for-alternative-energy-sources-amid-high-fuel-costs/.

- Boyd, G.A.; Pang, J.X. Estimating the Linkage between Energy Efficiency and Productivity. Energy Policy 2000, 28, 289–296. [CrossRef]

- Worrell, E.; Bernstein, L.; Roy, J.; Price, L.; Harnisch, J. Industrial Energy Efficiency and Climate Change Mitigation. Energy Effic 2009, 2, 109–123. [CrossRef]

- Proskuryakova, L.; Kovalev, A. Measuring Energy Efficiency: Is Energy Intensity a Good Evidence Base? Appl Energy 2015, 138, 450–459. [CrossRef]

- Ma’bdeh, S.N.; Ghani, Y.A.; Obeidat, L.; Aloshan, M. Affordability Assessment of Passive Retrofitting Measures for Residential Buildings Using Life Cycle Assessment. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13574. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Cong, W.; Pan, S. Incremental Cost-Benefit Analysis of Passive Residence Based on Low Carbon Perspective. In Proceedings of the ICCREM 2017; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, November 9 2017; pp. 164–171.

- Mikulić, D.; Bakarić, I.R.; Slijepčević, S. The Economic Impact of Energy Saving Retrofits of Residential and Public Buildings in Croatia. Energy Policy 2016, 96, 630–644. [CrossRef]

- Howden-Chapman, P.; Matheson, A.; Crane, J.; Viggers, H.; Cunningham, M.; Blakely, T.; Cunningham, C.; Woodward, A.; Saville-Smith, K.; O’Dea, D.; et al. Effect of Insulating Existing Houses on Health Inequality: Cluster Randomised Study in the Community. BMJ 2007, 334, 460. [CrossRef]

- Causone, F.; Pietrobon, M.; Pagliano, L.; Erba, S. A High Performance Home in the Mediterranean Climate: From the Design Principle to Actual Measurements. Energy Procedia 2017, 140, 67–79. [CrossRef]

- Payne, J. Downy, F. & Weatherall, D. Capturing the “Multiple Benefits” of Energy Efficiency in Practice: The UK Example. Available online: https://energysavingtrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/reports/1-424-15_Payne.pdf.

- Liang, X.; Peng, Y.; Shen, G.Q. A Game Theory Based Analysis of Decision Making for Green Retrofit under Different Occupancy Types. J Clean Prod 2016, 137, 1300–1312. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.-Y.; Lee, K.-T.; Kim, J.-H. Green Retrofitting Simulation for Sustainable Commercial Buildings in China Using a Proposed Multi-Agent Evolutionary Game. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7671. [CrossRef]

- Meijer, Frits; Visscher, Henk; Nieboer, Nico; Kroese, R. Jobs Creation through Energy Renovation of the Housing Stock. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20171222124828/http://www.neujobs.eu/sites/default/files/publication/2013/01/Energy renovation-D14-2 19th December 2012_.pdf%0A.

- Ürge-Vorsatz, D., Tirado-Herrero, S., Fegyverneky, S., Arena, D., Butcher, A., and Telegdy, A. Employment Impacts of a Large-Scale Deep Building Energy Retrofit Programme in Hungary. Available online: http://3csep.ceu.hu/projects/employment-impacts-of-a-large-scale-deep-building-energy-retrofit-programme-in-hungary.

- Bell, C.J. Energy Efficiency Job Creation: Real World Experiences. In Proceedings of the ACEEE White Paper.; 2012.

- Oyedepo, S. Efficient Energy Utilization as a Tool for Sustainable Development in Nigeria. International Journal of Energy and Environmental Engineering 2012, 3, 11. [CrossRef]

- Sameh, S. and Kamel, B. Promoting Green Retrofitting to Enhance Energy Efficiency of Residential Buildings in Egypt. Journal of Engineering and Applied Science 2020, 67, 1709–1728.

- Tuominen, P.; Klobut, K.; Tolman, A.; Adjei, A.; de Best-Waldhober, M. Energy Savings Potential in Buildings and Overcoming Market Barriers in Member States of the European Union. Energy Build 2012, 51, 48–55. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; 3rd ed.; Sage Publications., 2017;

- Nigerian Institution of Estate Surveyors and Valuers (NIESV). 2023 Financial Members. Available online: https://www.niesv.org.ng/financial_list.php.

- NIESV. (2024). Firms Directory. Available online: https://www.firms.niesv.org.ng/niesv_firm_by_location.php?firm_location1=Lagos (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Hendriks, G. How the Spatial Dispersion and Size of Country Networks Shape the Geographic Distance That Firms Add during International Expansion. International Business Review 2020, 29, 101738. [CrossRef]

- Ott, R.L. & Longnecker, M. An Introduction to Statistical Methods and Data Analysis.; Brooks/Cole, Belmont, CA., 2010;

- Corral, N.; Gil, M.Á.; Gil, P. Interval and Fuzzy-Valued Approaches to the Statistical Management of Imprecise Data. In; 2011; pp. 453–468.

- Adegoke, A.S.; Taiwo Gbadegesin, J.; Oluwafemi Ayodele, T.; Efuwape Agbato, S.; Bamidele Oyedele, J.; Tunde Oladokun, T.; Onyinyechukwu Ebede, E. Property Managers’ Awareness of the Potential Benefits of Vertical Greenery Systems on Buildings. International Journal of Construction Management 2023, 23, 2769–2778. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yeung, J.F.Y.; Chan, A.P.C.; Chan, D.W.M.; Wang, S.Q.; Ke, Y. Developing a Risk Assessment Model for PPP Projects in China — A Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation Approach. Autom Constr 2010, 19, 929–943. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Z.; Lyu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Gu, Y.; Huang, X.; Zheng, H.; et al. Flood Risk Assessment Based on Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation Method in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Metropolitan Area, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1451. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.D.; Macchion, L. A Comprehensive Risk Assessment Model Based on a Fuzzy Synthetic Evaluation Approach for Green Building Projects: The Case of Vietnam. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management 2023, 30, 2837–2861. [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, J.L. A Note on the Usage of Likert Scaling for Research Data Analysis. USM R & D 2010, 18, 109–112.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006, 3, 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill.: New York, 1994;

- Mangialardo, A.; Micelli, E.; Saccani, F. Does Sustainability Affect Real Estate Market Values? Empirical Evidence from the Office Buildings Market in Milan (Italy). Sustainability 2019, 11, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lian, Y.; Zhao, H.; Xia-Bauer, C. Unlocking Green Financing for Building Energy Retrofit: A Survey in the Western China. Energy Strategy Reviews 2020, 30, 100520. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Read, B.; Pullen, S.; Shi, Q. Achieving Carbon Neutrality in Commercial Building Developments – Perceptions of the Construction Industry. Habitat Int 2012, 36, 278–286. [CrossRef]

- Santamouris, M.; Kolokotsa, D. Passive Cooling Dissipation Techniques for Buildings and Other Structures: The State of the Art. Energy Build 2013, 57, 74–94. [CrossRef]

- Nguanso, C.; Taweekun, J.; Dai, Y.; Ge, T. The Criteria of Passive and Low Energy in Building Design for Tropical Climate in Thailand. International Journal of Integrated Engineering 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Mastroberti, M., Bournas, D., Vona, M., Manganelli, B., & Palermo, V. Combined Seismic plus Energy Retrofitting for the Existing RC Buildings: Economic Feasibility. Available online: https://iris.unibas.it/handle/11563/136075.

- Elaouzy, Y.; El Fadar, A. Energy, Economic and Environmental Benefits of Integrating Passive Design Strategies into Buildings: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 167, 112828. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Tan, Y.; Huang, Z. Knowledge Mapping of Homeowners’ Retrofit Behaviors: An Integrative Exploration. Buildings 2021, 11, 273. [CrossRef]

| Dimensions | Key benefits | Code | References |

| Environmental | Reduces heavy reliance on non-renewable energy consumption | Env1 | Hirvonen et al. [33], Hurley et al. [36], Kabeyi and Olanrewaju [35]. |

| Reduces carbon emissions and household energy consumption | Env2 | Ahn et al. [40], Alcazar and Bass [42], Alkhateeb and Hijleh [39], Clinch and Healy [47], Coyne et al. [30], Hirvonen et al. [33], Hurley et al. [36], Insulation Council of Australia and New Zealand [ICANZ] [44], Jafari et al. [34], Luddeni et al. [38], Niachou et al. [43]. | |

| Enhances air quality | Env3 | Ahn et al. [40], Pacheco-Torgal [41]. | |

| Mitigation of climate change | Env4 | Ab. Azis et al. [20]. | |

| Enhances energy security | Env5 | Ahn et al. [40], Oguntona et al. [45]. | |

| Increases the energy star rating of existing residential dwellings | Env6 | ICANZ [44]. | |

| Reduces solar radiation and glare | Env7 | Shahdan et al. [46]. | |

| Economic | Improves competitive positioning in the property market and attract more willing tenants | Eco1 | Ahn et al. [40]. |

| Increases property value | Eco2 | Brounen et al. [49], Hirvonen et al. [33], ICANZ [44], Pivo and Fisher [48], Sameh and Kamel [69]. | |

| Saves energy and reduces consumption cost | Eco3 | Clinch and Healy [47], Hirvonen et al. [33], Pacheco-Torgal [41], Ma'bdeh et al. [57], Mayer et al. [50], Rhoads [51], Su et al. [58]. | |

| Improves real estate’s contribution to national economic growth in the long run | Eco4 | Hirvonen et al. [33], Proskuryakova and Kovalev [56], Tuominen et al. [70]. | |

| Social | Enhances homeowners’ social reputation | Soc1 | Ahn et al. [40], Liang et al. [63], Wang et al. [64]. |

| Reduces illness and health care expenditures and guarantees good health and well-being | Soc2 | Causone [61], Clinch and Healy [47], Coyne et al. [30], Howden-Chapman et al. [60], Jafari and Valentin [31], Payne et al. [62]. | |

| Improves indoor thermal comfort, tenants’ satisfaction, and productivity | Soc3 | Causone [61], Clinch and Healy [47], Liang et al. [63], Payne et al. [62]. | |

| Creates local jobs and drives community growth | Soc4 | Bell [67], Clinch and Healy [47], Hurley et al. [36], Meijer et al. [65], Mikulić et al. [59], Oyedepo [68], Ürge-Vorsatz et al. [66]. | |

| Fosters positive tenant-owner relationship | Soc5 | Oguntona et al. [45]. |

| Respondent | Profession | Agency | Years with agency |

| LAS001 | Civil Engineer | LASBCA | 5 years |

| LAS002 | Town Planner | LASBCA | 24 years |

| LAS003 | Town Planner | LASPPPA | 11 years |

| LAS004 | Architect | LASPPPA | 16 years |

| LAS005 | Civil Engineer & Geographic Information System (GIS) Analyst | LASBCA | 8 years |

| LAS006 | Architect | LASPPPA | 15 years |

| Retrofit benefits |

Criteria Mean (1) |

Level 3 membership function (% of response) (2) |

Criteria weight (3) |

Dimen-sion weight (4) | Level 2 membership function (5 = 2*3) | 6 = 5/Likert scale* | Awareness scores | ||||||||||||

| SU | SLU | N | SLA | SA | SU | SLU | N | SLA | SA | SU | SLU | N | SLA | SA | |||||

| Environmental | 0.437 | 0.019 | 0.120 | 0.068 | 0.546 | 0.246 | 0.019 | 0.241 | 0.205 | 2.185 | 1.228 | 3.88 | |||||||

| Env4 | 3.96 | 0.000 | 0.102 | 0.102 | 0.534 | 0.263 | 0.1460 | ||||||||||||

| Env5 | 3.96 | 0.017 | 0.110 | 0.042 | 0.559 | 0.271 | 0.1460 | ||||||||||||

| Env2 | 3.95 | 0.034 | 0.102 | 0.042 | 0.525 | 0.297 | 0.1456 | ||||||||||||

| Env1 | 3.92 | 0.008 | 0.144 | 0.034 | 0.551 | 0.263 | 0.1445 | ||||||||||||

| Env3 | 3.92 | 0.042 | 0.068 | 0.068 | 0.568 | 0.254 | 0.1445 | ||||||||||||

| Env6 | 3.75 | 0.017 | 0.153 | 0.068 | 0.585 | 0.178 | 0.1382 | ||||||||||||

| Env7 | 3.67 | 0.017 | 0.169 | 0.127 | 0.500 | 0.186 | 0.1353 | ||||||||||||

| Economic | 0.259 | 0.021 | 0.089 | 0.075 | 0.473 | 0.342 | 0.021 | 0.177 | 0.226 | 1.891 | 1.710 | 4.03 | |||||||

| Eco2 | 4.13 | 0.008 | 0.085 | 0.059 | 0.466 | 0.381 | 0.2565 | ||||||||||||

| Eco3 | 4.12 | 0.034 | 0.059 | 0.025 | 0.517 | 0.364 | 0.2559 | ||||||||||||

| Eco4 | 3.95 | 0.025 | 0.110 | 0.110 | 0.398 | 0.356 | 0.2453 | ||||||||||||

| Eco1 | 3.9 | 0.017 | 0.102 | 0.110 | 0.508 | 0.263 | 0.2422 | ||||||||||||

| Social | 0.304 | 0.027 | 0.118 | 0.128 | 0.501 | 0.226 | 0.027 | 0.236 | 0.384 | 2.003 | 1.130 | 3.78 | |||||||

| Soc3 | 3.97 | 0.025 | 0.068 | 0.076 | 0.568 | 0.263 | 0.2102 | ||||||||||||

| Soc4 | 3.76 | 0.017 | 0.110 | 0.178 | 0.483 | 0.212 | 0.1990 | ||||||||||||

| Soc2 | 3.75 | 0.017 | 0.169 | 0.102 | 0.475 | 0.237 | 0.1985 | ||||||||||||

| Soc1 | 3.74 | 0.042 | 0.119 | 0.136 | 0.466 | 0.237 | 0.1980 | ||||||||||||

| Soc5 | 3.67 | 0.034 | 0.127 | 0.153 | 0.508 | 0.178 | 0.1943 | ||||||||||||

| Dimensions | Dimension weight (4) | Level 2 membership function (5 = 2*3) |

Level 1 membership function (7 = 4*5) |

GAS | |||||||||

| SU | SLU | N | SLA | SA | SU | SLU | N | SLA | SA | ||||

| Environmental | 0.437 | 0.019 | 0.120 | 0.068 | 0.546 | 0.246 | |||||||

| Economic | 0.259 | 0.021 | 0.089 | 0.075 | 0.473 | 0.342 | |||||||

| Social | 0.304 | 0.027 | 0.118 | 0.128 | 0.501 | 0.226 | |||||||

| 0.022 | 0.111 | 0.088 | 0.513 | 0.265 | 0.022 | 0.223 | 0.265 | 2.053 | 1.323 | 3.89 | |||

| Retrofit benefits |

Criteria Mean (1) |

Level 3 membership function (% of response) (2) |

Criteria weight (3) |

Dimension weight (4) | Level 2 membership function (5 = 2*3) | 6 = 5/Likert scale* | Awareness scores | ||||||||||||

| SU | SLU | N | SLA | SA | SU | SLU | N | SLA | SA | SU | SLU | N | SLA | SA | |||||

| Environmental | 0.397 | 0.101 | 0.255 | 0.072 | 0.422 | 0.151 | 0.101 | 0.509 | 0.216 | 1.686 | 0.756 | 3.27 | |||||||

| Env7 | 3.39 | 0.055 | 0.239 | 0.098 | 0.472 | 0.135 | 0.1483 | ||||||||||||

| Env6 | 3.39 | 0.055 | 0.282 | 0.080 | 0.387 | 0.196 | 0.1483 | ||||||||||||

| Env3 | 3.37 | 0.117 | 0.202 | 0.037 | 0.485 | 0.160 | 0.1474 | ||||||||||||

| Env4 | 3.28 | 0.104 | 0.245 | 0.074 | 0.423 | 0.153 | 0.1435 | ||||||||||||

| Env5 | 3.23 | 0.086 | 0.282 | 0.092 | 0.399 | 0.141 | 0.1413 | ||||||||||||

| Env2 | 3.15 | 0.135 | 0.264 | 0.061 | 0.399 | 0.141 | 0.1378 | ||||||||||||

| Env1 | 3.05 | 0.160 | 0.270 | 0.061 | 0.380 | 0.129 | 0.1334 | ||||||||||||

| Economic | 0.276 | 0.032 | 0.105 | 0.057 | 0.451 | 0.355 | 0.032 | 0.210 | 0.172 | 1.805 | 1.773 | 3.99 | |||||||

| Eco2 | 4.29 | 0.031 | 0.043 | 0.025 | 0.405 | 0.497 | 0.2703 | ||||||||||||

| Eco4 | 4.13 | 0.025 | 0.067 | 0.061 | 0.448 | 0.399 | 0.2602 | ||||||||||||

| Eco1 | 3.95 | 0.037 | 0.098 | 0.031 | 0.546 | 0.288 | 0.2489 | ||||||||||||

| Eco3 | 3.5 | 0.037 | 0.233 | 0.123 | 0.405 | 0.202 | 0.2205 | ||||||||||||

| Social | 0.327 | 0.039 | 0.124 | 0.109 | 0.450 | 0.278 | 0.039 | 0.247 | 0.327 | 1.800 | 1.389 | 3.80 | |||||||

| Soc4 | 4.25 | 0.012 | 0.049 | 0.061 | 0.429 | 0.448 | 0.2261 | ||||||||||||

| Soc1 | 4.15 | 0.018 | 0.055 | 0.067 | 0.472 | 0.387 | 0.2207 | ||||||||||||

| Soc3 | 3.77 | 0.031 | 0.135 | 0.074 | 0.558 | 0.202 | 0.2005 | ||||||||||||

| Soc5 | 3.44 | 0.031 | 0.184 | 0.233 | 0.423 | 0.129 | 0.1830 | ||||||||||||

| Soc2 | 3.19 | 0.123 | 0.233 | 0.135 | 0.350 | 0.160 | 0.1697 | ||||||||||||

| Dimensions | Dimension weight (4) |

Level 2 membership function (5 = 2*3) |

Level 1 membership function (7 = 4*5) |

GAS | |||||||||

| SU | SLU | N | SLA | SA | SU | SLU | N | SLA | SA | ||||

| Environmental | 0.397 | 0.101 | 0.255 | 0.072 | 0.422 | 0.151 | |||||||

| Economic | 0.276 | 0.032 | 0.105 | 0.057 | 0.451 | 0.355 | |||||||

| Social | 0.327 | 0.039 | 0.124 | 0.109 | 0.450 | 0.278 | |||||||

| 0.062 | 0.171 | 0.080 | 0.439 | 0.249 | 0.062 | 0.341 | 0.240 | 1.756 | 1.243 | 3.64 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).