Submitted:

31 May 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. University Course

2.2. Surveys

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

| Demographics | N = 374 |

|---|---|

| Age (years, median ± mad) | 21 (1.7) |

| Gender n (%) | |

| Male | 140 (37) |

| Female | 234 (63) |

| Ethnicity n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 136 (36) |

| Black/African American | 7 (2) |

| Asian | 136 (36) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1 (0) |

| American Indian / Alaska Native | 6 (2) |

| More than one ethnicity | 41 (11) |

| Other | 47 (13) |

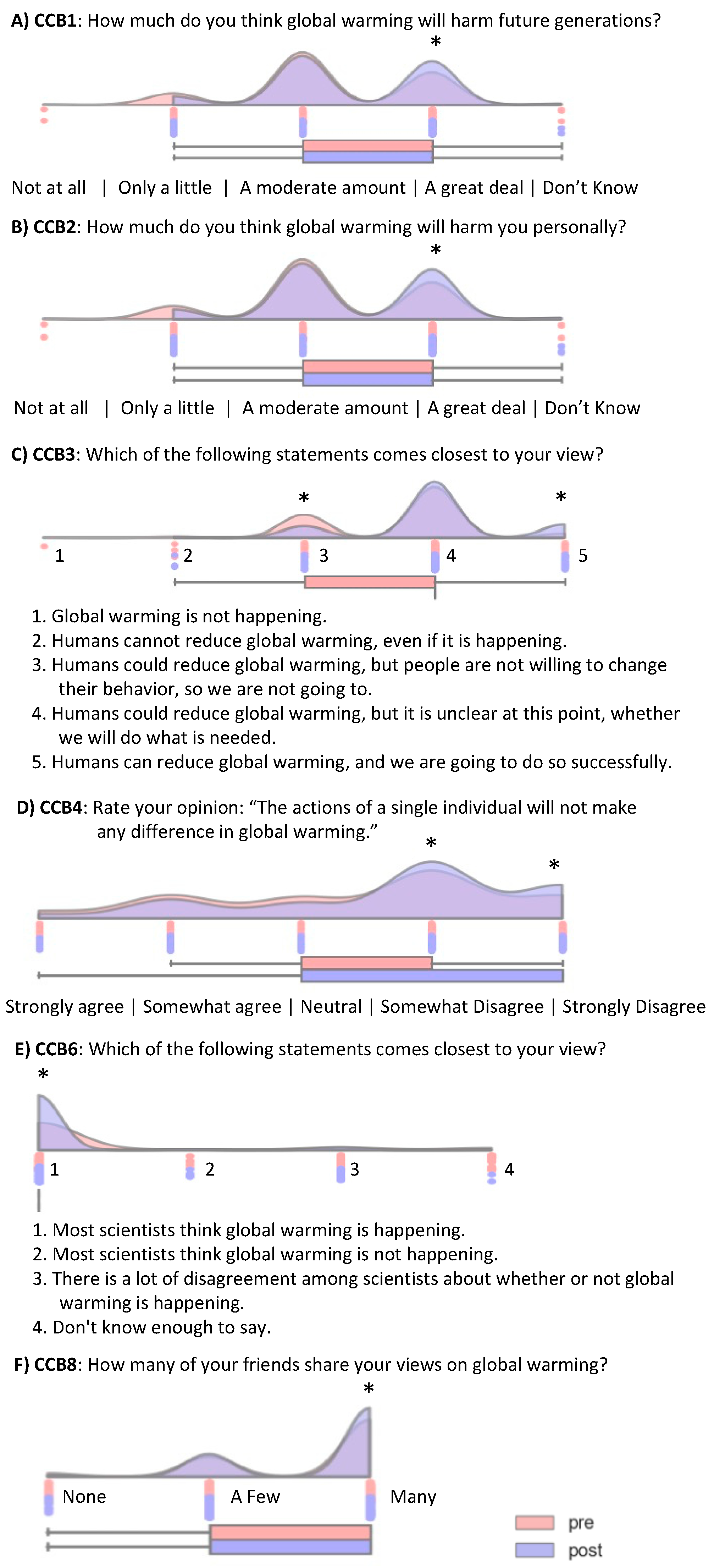

3.2. Climate Change Beliefs

| Statement | Not at all (1) / Only a little (2) | A moderate amount (3) | A great deal (4) | Don't know (5) | Pre Median (MAD) |

Post Median (MAD) |

P- Val |

||||

| Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | ||||

| CCB1: How much do you think global warming will harm future generations? | 1.9 | 0.5 | 8.0 | 5.6 | 89.8 | 93.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 4 (0.2) | 4 (0.1) | 0.013 |

| CCB2: How much do you think global warming will harm you personally? | 12.3 | 8.3 | 53.7 | 47.9 | 33.2 | 42.8 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Statement | 1/2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Pre Median (MAD) |

Post Median (MAD) |

P- Val |

||||

| Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | ||||

| CCB3: Which of the following statements come closest to your view? | 1.3 | 0.8 | 28.9 | 13.6 | 64.4 | 69.8 | 5.4 | 15.8 | 4 (0.5) |

4 (0.3) |

<0.0001 |

| CCB3 key - 1. Global warming is not happening. 2. Humans cannot reduce global warming, even if it is happening. 3. Humans could reduce global warming, but people are not willing to change their behavior, so we are not going to. 4. Humans could reduce global warming, but it is unclear at this point, whether we will do what is needed. 5. Humans can reduce global warming, and we are going to do so successfully. | |||||||||||

| Statement | Strongly agree (1) / Somewhat agree (2) | Neutral (3) | Somewhat disagree (4) / Strongly Disagree (5) | Pre Median (MAD) |

Post Median (MAD) |

P- Val |

|||||

| Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | ||||||

| CCB4: The actions of a single individual will not make any difference in global warming. | 24.9 | 17.9 | 17.1 | 12.0 | 58.0 | 70.1 | 4 (1.0) |

4 (0.9) |

<0.0001 | ||

| CCB5: New technologies can solve global warming, without individuals having to make big changes in their lives. | 30.7 | 33.2 | 19.0 | 15.5 | 50.3 | 51.3 | 4 (1.1) | 4 (1.2) | n. s. | ||

| CCB7: I have personally experienced the effects of global warming. | 71.9 | 76.2 | 15.0 | 13.4 | 13.1 | 10.4 | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.7) | n. s. | ||

| Statement | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Pre Median (MAD) |

Post Median (MAD) |

P- Val |

||||

| Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % |

||||

| CCB6: Which of the following statements come closest to your view? (Fig. 1B) | 84.8 | 93.9 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 8.0 | 4.6 | 5.9 | 0.5 | 1 (0.6) |

1 (0.2) |

<0.0001 |

| CCB6 key – 1. Most scientists think global warming is happening. 2. Most scientists think global warming is not happening. 3. There is a lot of disagreement among scientists about whether or not global warming is happening. 4. Don't know enough to say. | |||||||||||

| None (1) | A Few (2) | Many (3) | Pre Median (MAD) |

Post Median (MAD) |

P- Val |

||||||

| Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | ||||||

| CCB8: How many of your friends share your views on global warming? | 4.3 | 1.6 | 25.4 | 24.6 | 70.4 | 73.8 | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) | 0.023 | ||

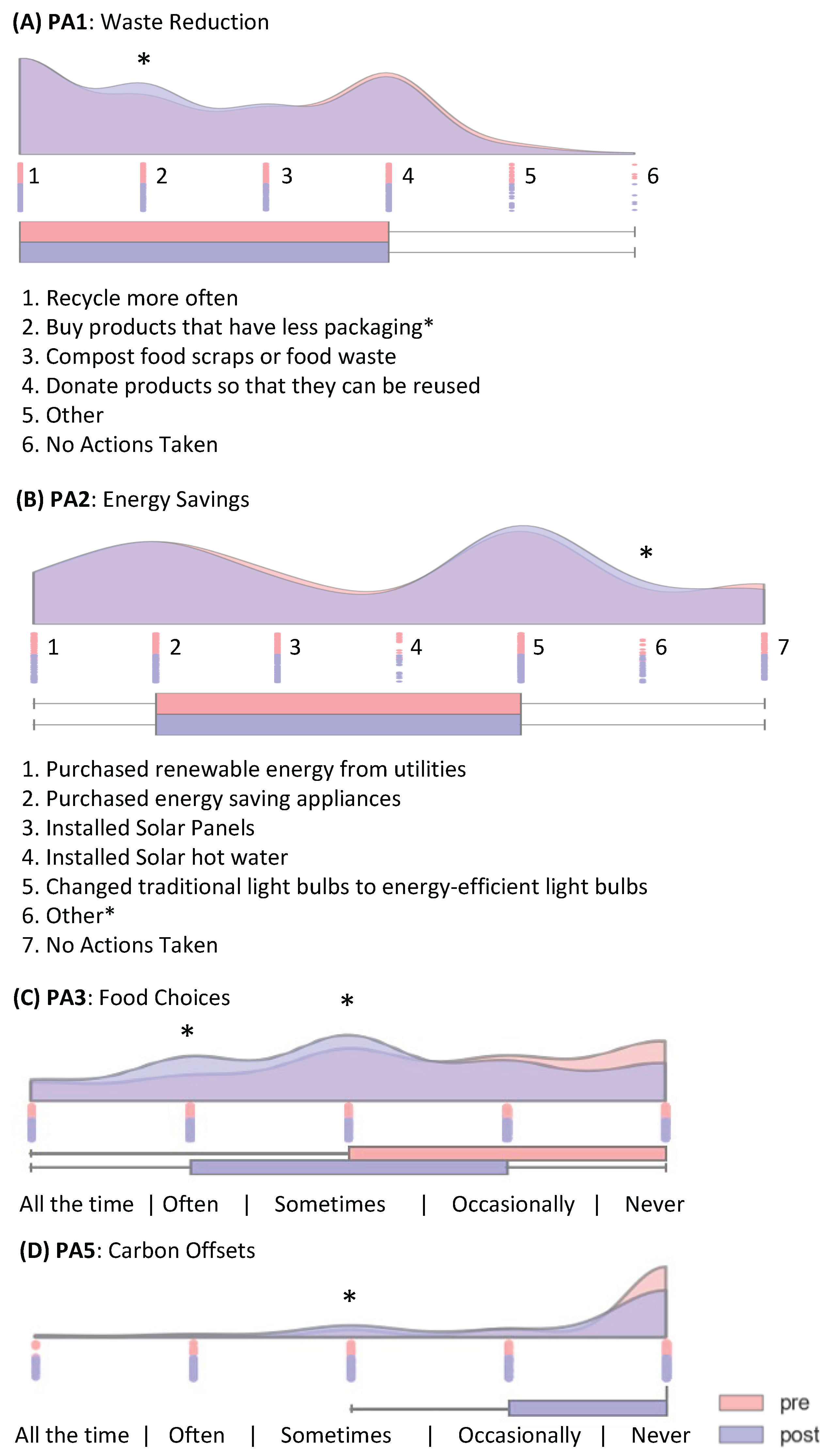

3.3. Personal Pro-Environmental Actions

| (1) Waste Reduction | Pre % | Post | P-val | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recycle more often | 90.1 | 91.7 | n.s. | |

| Buy products that have less packaging | 52.4 | 65.5 | <0.001 | |

| Compost food scraps or food waste | 40.9 | 44.9 | n.s. | |

| Donate products so that they can be reused | 76.5 | 74.3 | ||

| Other | 8.8 | 7.0 | ||

| No Actions Taken | 1.3 | 1.1 | ||

| (2) Energy Savings | Pre % | Post | P-val | |

| Purchased renewable energy from utilities | 21.7 | 24.1 | n.s. | |

| Purchased energy saving appliances | 40.4 | 44.1 | ||

| Installed Solar Panels | 21.1 | 19.5 | ||

| Installed Solar hot water | 4.8 | 5.1 | ||

| Changed traditional light bulbs to energy-efficient light bulbs | 54.6 | 61.0 | ||

| Other* | 3.7 | 10.7 | <0.001 | |

| No Actions Taken | 23.5 | 20.3 | n.s. | |

| (3) Food Choices | ||||

|

Never / Occasionally |

Sometimes / Often / All the Time |

|||

| Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | P-val |

| 52.1 | 37.2 | 47.9 | 62.8 | <0.001 |

| (4) Transportation Emissions | Pre % | Post | P-val | |

| Purchased a hybrid car | 18.7 | 16.8 | n.s. | |

| Carpool regularly | 45.2 | 52.7 | ||

| Purchased a more gas-efficient car | 23.8 | 24.6 | ||

| Used public transportation more often | 58.8 | 64.2 | ||

| Used a bicycle instead of a car as transportation | 17.9 | 20.1 | ||

| No Actions Taken | 16.0 | 13.4 | ||

| (5) Carbon offsets | ||||

|

Never / Occasionally |

Sometimes / Often / All the Time |

|||

| Pre % | Post % | Pre % | Post % | P-val |

| 88.0 | 76.7 | 12.0 | 23.3 | <0.001 |

3.4. Carbon Footprint

3.5. Behavioral Changes: Stress, Resilience, and Wellbeing

| Outcome | Pre (Median ± MAD) | Post (Median ± MAD) | P-val |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Stress | 20 ± 4.84 | 20 ± 5.00 | n.s. |

| Wellbeing | 3.43 ± 0.46 | 3.29 ± 0.45 | |

| Resilience | 3.33 ± 0.55 | 3.33 ± 0.55 |

4. Discussion

Acknowledgements

Appendix A

| Survey response | CO2 reduction (tons/year) | Assumptions used in CoolClimate calculator |

|---|---|---|

| Buy renewable energy | 1.36 | 100% electricity from renewables |

| Buy energy star appliances | 0.04 | Energy star fridge or other products |

| Install solar panels | 0.68 | 50% electricity from renewables |

| Install solar hot water | 0.4 | 50% of heating of water from solar hot water |

| Change light bulbs | 0.16 | 5 bulbs used 5 hours per day |

| Buy hybrid/electric car | 4.22 | average of hybrids (40 mpg*2/3) + electric vehicles (99 mpg*1/3)) = 59.67 mpg |

| Recycle more often, buy products with less packaging, compost food scraps, give away/donate products | 0.42 | Reduce waste by 25% for each action |

| Carpool regularly | 0.85 | 3 times/week |

| Buy more fuel-efficient vehicle | 2.08 | 32 mpg vs. 22 mpg for 13,100 miles/yr. |

| Use public transit more | 0.42 | 20 miles/week in bus instead of 22 mpg in car |

| Use bike for transportation | 0.53 | 20 miles/week instead of 22 mpg in car |

| Make food choices to reduce emissions | 0.69 | Response of ‘all the time’ or ‘often’ is default setting for ‘low carbon version of American diet’ (0.69 tons/year). Response of ‘sometimes’ or ‘occasionally’ is a reduction of 0.46 tons/year through increase in meat consumption from 244 calories (default) to 353 calories. |

| Buy carbon offsets for flying | 0.93 | Response of ‘all the time’ or ‘often’ is 80% of flights purchased offsets (0.93 tons/yr.). Response of ‘sometimes’ or ‘occasionally’ is 40% of flights purchased offsets (0.46 tons/yr.). |

References

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (Ipcc). Climate Change 2022—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.Cambridge University Press, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, K.; Denckla, C.A.; Hahn, J.; Schiff, J.E.; Okuzono, S.S.; Randriamady, H.; et al. A systematic review of the effects of chronic, slow-onset climate change on mental health. Nat Ment Health. 2024, 2, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianconi, P.; Betrò, S.; Janiri, L. The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health: A Systematic Descriptive Review. Front Psychiatry. 2020, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, P.; Eboreime, E.; Agyapong, V.I.O. The Impact of Wildfires on Mental Health: A Scoping Review. Behav Sci. 2021, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Manning, C.; Meighen, S.; Hill, A.N. Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Inequities, Responses; American Psychological Association, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, H.L.; Bowen, K.; Kjellstrom, T. Climate change and mental health: A causal pathways framework. Int J Public Health. 2010, 55, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, K.; Hankin, B.L.; Kloos, B.; Cheely, C.; Turecki, G. Alcohol and Cigarette Use and Misuse Among Hurricane Katrina Survivors: Psychosocial Risk and Protective Factors. Subst Use Misuse. 2009, 44, 1711–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, C.S.; McKibben, J.B.A.; Reissman, D.B.; Scharf, T.; Kowalski-Trakofler, K.M.; Shultz, J.M.; et al. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Depression, and Alcohol and Tobacco Use in Public Health Workers After the 2004 Florida Hurricanes. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013, 7, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grennan, G.K.; Withers, M.C.; Ramanathan, D.S.; Mishra, J. Differences in interference processing and frontal brain function with climate trauma from California’s deadliest wildfire. Jia F, editor. PLOS Clim. 2023, 2, e0000125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradovich, N.; Migliorini, R.; Paulus, M.P.; Rahwan, I. Empirical evidence of mental health risks posed by climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018, 115, 10953–10958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Wong, M. Global climate change and mental health. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020, 32, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, R.M.; Gillezeau, C.N.; Liu, B.; Lieberman-Cribbin, W.; Taioli, E. Longitudinal Impact of Hurricane Sandy Exposure on Mental Health Symptoms. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017, 14, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, S.; Kornbluh, M.; Withers, M.C.; Grennan, G.; Ramanathan, V.; Mishra, J. Chronic Mental Health Sequelae of Climate Change Extremes: A Case Study of the Deadliest Californian Wildfire. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewandowski, R.E.; Clayton, S.D.; Olbrich, L.; Sakshaug, J.W.; Wray, B.; Schwartz, S.E.O.; et al. Climate emotions, thoughts, and plans among US adolescents and young adults: A cross-sectional descriptive survey and analysis by political party identification and self-reported exposure to severe weather events. Lancet Planet Health. 2024, 8, e879–e893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; et al. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet Health. 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanathan, V.; Von Braun, J. (Eds.) The proceedings of the Conference on Resilience of people and ecosystems under climate stress: 13-14 July 2022. Città del Vatican; Libreria editrice vaticana, 14 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; United Nations, 1992.

- Monroe, M.C.; Plate, R.R.; Oxarart, A.; Bowers, A.; Chaves, W.A. Identifying effective climate change education strategies: A systematic review of the research. Environ Educ Res. 2019, 25, 791–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, V.; Aines, R.; Auffhammer, M.; Barth, M.; Cole, J.; Forman, F.; et al. Bending the Curve: Climate Change Solutions. 2019. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6kr8p5rq.

- Vlasceanu, M.; Doell, K.C.; Bak-Coleman, J.B.; Todorova, B.; Berkebile-Weinberg, M.M.; Grayson, S.J.; et al. Addressing climate change with behavioral science: A global intervention tournament in 63 countries. Sci Adv. 2024, 10, eadj5778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A. Climate Change Education for Mitigation and Adaptation. J Educ Sustain Dev. 2012, 6, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Bryan, A. Climate Change Education in the Context of Education for Sustainable Development: Rationale and Principles. J Educ Sustain Dev. 2015, 9, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, E.C.; Centeno, D.; Todd, A.M. The role of climate change education on individual lifetime carbon emissions. Pausata FSR, editor. PLoS ONE. 2020, 15, e0206266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabow, M.; Bryan, T.; Checovich, M.M.; Converse, A.K.; Middlecamp, C.; Mooney, M.; et al. Mindfulness and Climate Change Action: A Feasibility Study. Sustainability. 2018, 10, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zautra, A.J.; Arewasikporn, A.; Davis, M.C. Resilience: Promoting Well-Being Through Recovery, Sustainability, and Growth. Res Hum Dev. 2010, 7, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epel, E.; Mishra, J.; Ekman, E.; Ogunseitan, C.; Fromer, E.; Kho, L.; et al. Effects of a Novel Psychosocial Climate Resilience Course on Climate Distress, Self-Efficacy, and Mental Health in Young Adults. Sustainability. 2025, 17, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, V.; Forman, F.; Suárez-Orozco, M.; Roper, A.; Friese, S.; Flammer, K.; et al. CLIMATE CHANGE AND EDUCATION FOR ALL: BENDING THE CURVE EDUCATION PROJECT. In Education; Suárez-Orozco, M., Suárez-Orozco, C., Eds.; Columbia University Press, 2022; pp. 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promoting Active Learning through the Flipped Classroom Model; Keengwe, J., Onchwari, G., Oigara, J.N., Eds.; IGI Global, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, V.; Aines, R.; Auffhammer, M.; Barth, M.; Cole, J.; Forman, F.; et al. Bending the Curve: Climate Change Solutions. 2019. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6kr8p5rq.

- Association, A.M. Bending the Curve Video Series. [cited ]. 30 May. Available online: https://edhub.ama-assn.org/university-of-california-climate-health-equity/pages/bending-the-curve-video-series.

- Bending the Curve: Climate Education for All. In: OHWA [Internet]. 5 Apr 2024 [cited]. 30 May. Available online: https://onehealthworkforceacademies.org/training/bending-the-curve-adaptation/.

- Tennant, R.; Hiller, L.; Fishwick, R.; Platt, S.; Joseph, S.; Weich, S.; et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007, 5, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983, 24, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What’s Your Carbon Footprint? | Center for Science Education. 14 Aug 2024 [cited 14 Aug 2024]. Available online: https://scied.ucar.edu/learning-zone/climate-solutions/carbon-footprint.

- Franklin, S.; Pindyck, R. A Supply Curve for Forest-Based CO₂ Removal. In A Supply Curve for Forest-Based CO₂ Removal; Report No.: w32207; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, 2024; p. w32207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About, us. In: University of California [Internet]. 14 Aug 2024 [cited 14 Aug 2024]. Available online: https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/about-us.

- What Exactly Is 1 Tonne Of CO2? | Anthesis Group. 31 Jul 2023 [cited ]. 13 May. Available online: https://www.anthesisgroup.com/insights/what-exactly-is-1-tonne-of-co2/.

- Home/. In: Climate Resilience [Internet]. [cited ]. 13 May. Available online: https://www.climateresilience.online.

- Bureau, U.C. State Population Totals and Components of Change: 2020-2023. In: Census.gov [Internet]. 21 Aug 2024 [cited 21 Aug 2024]. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-state-total.html.

- Composto, J.W.; Weber, E.U. Effectiveness of behavioural interventions to reduce household energy demand: A scoping review. Environ Res Lett. 2022, 17, 063005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, C.F.; Bélanger, J.J.; Schumpe, B.M.; Faller, D.G. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials testing behavioural interventions to promote household action on climate change. Nat Commun. 2019, 10, 4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Carbon Footprint Reduction per student CO2 tons/year (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre % | Post % | P-val | |

| Waste Reduction | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.4) | 26.3 (22.5) | 26.1 (18.5) | 0.0017 |

| Energy Savings | 0.6 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.7) | 13.5 (14.8) | 13.4 (15.3) | n.s. |

| Food Choices | 0.4 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.2) | 8.9 (11.2) | 10.1 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Transport Emissions | 2.0 (2.2) | 2.0 (2.1) | 48.5 (25.1) | 46.1 (22.5) | n.s. |

| Carbon Offsets | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.2 (0.3) | 2.8 (5.8) | 4.3 (6.4) | <0.001 |

| Overall | 4.2 (2.7) | 4.5 (2.6) | - | - | 0.0013 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).