Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The P/E Ratio and Its Constraints

2.2. The PEG Ratio: A Partial Adjustment for Growth

2.3. Discounted Cash Flow and the Gordon Growth Model

- P is the intrinsic value of the stock

- D1 is the dividend expected in the next period

- r is the required rate of return or discount rate

- g is the expected constant growth rate in dividends

- P is the present value of the stock

- FCFt is the expected free cash flow in year t

- r is the discount rate reflecting time value of money and risk.

2.4. The Case for Generalization

- Generalizes the P/E ratio to include earnings growth and discounting;

- Retains simplicity and intuitive interpretation;

- Applies even when earnings are low, negative, or volatile.

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Revisiting the P/E Ratio

- Earnings remain constant in perpetuity,

- There is no time value of money (no discounting),

- Growth is absent or negligible,

- Earnings are positive and reliably estimated.

3.2. Defining the Potential Payback Period (PPP)

- P is the current stock price

- E is the current earnings per share

- g is the expected constant earnings growth rate

- r is the discount rate (typically derived from CAPM or investor-required return).

3.3. Derivation and Interpretation

3.4. The PPP as a Generalization of P/E

- If g = 0 and r = 0, then:

-

If g = r, then both the numerator and denominator of the full PPP formula approach zero. This results in an indeterminate form 0/0, where L’Hôpital’s Rule applies. Taking derivatives with respect to g confirms that:

3.5. Conceptual Advantages

- Forward-looking: Unlike P/E, PPP naturally incorporates expectations of earnings growth and required returns.

- Time-sensitive: Expressed in years, PPP provides an intuitive time horizon for investment recovery.

- Universally applicable: Unlike P/E, PPP remains defined even when earnings are low, volatile, or negative (as shown later).

- Integrative: PPP bridges the gap between relative valuation (multiples) and absolute valuation (discounted earnings).

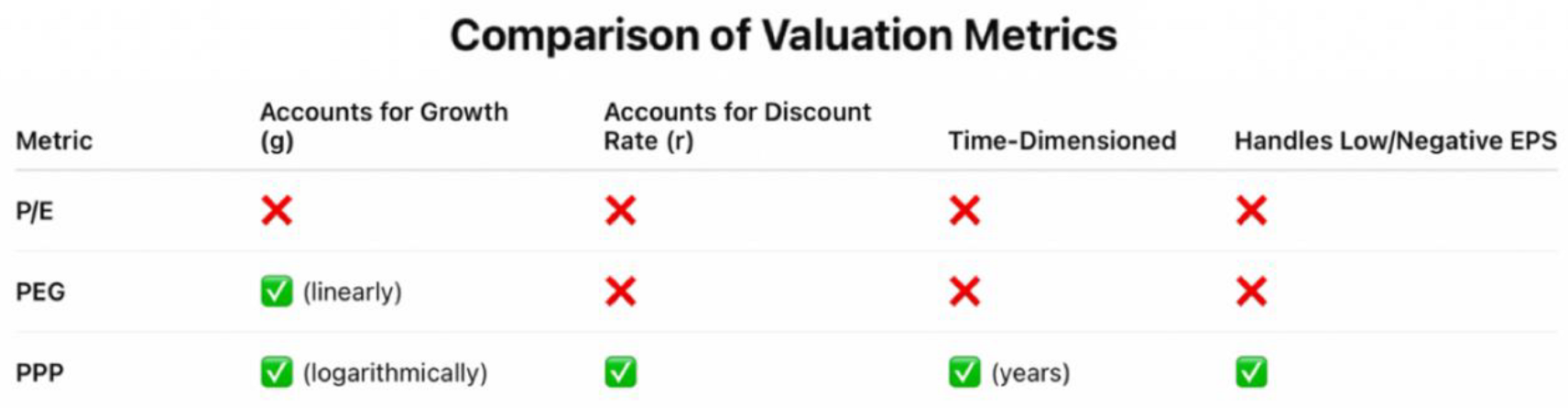

4. Comparative Analysis

4.1. Static vs. Dynamic Valuation Metrics

- The P/E ratio is static and forward-agnostic.

- The PEG ratio improves on the P/E by incorporating earnings growth, but not the time value of money or risk.

- The PPP incorporates both key dynamic elements — growth and discounting — while preserving an intuitive unit: time to payback.

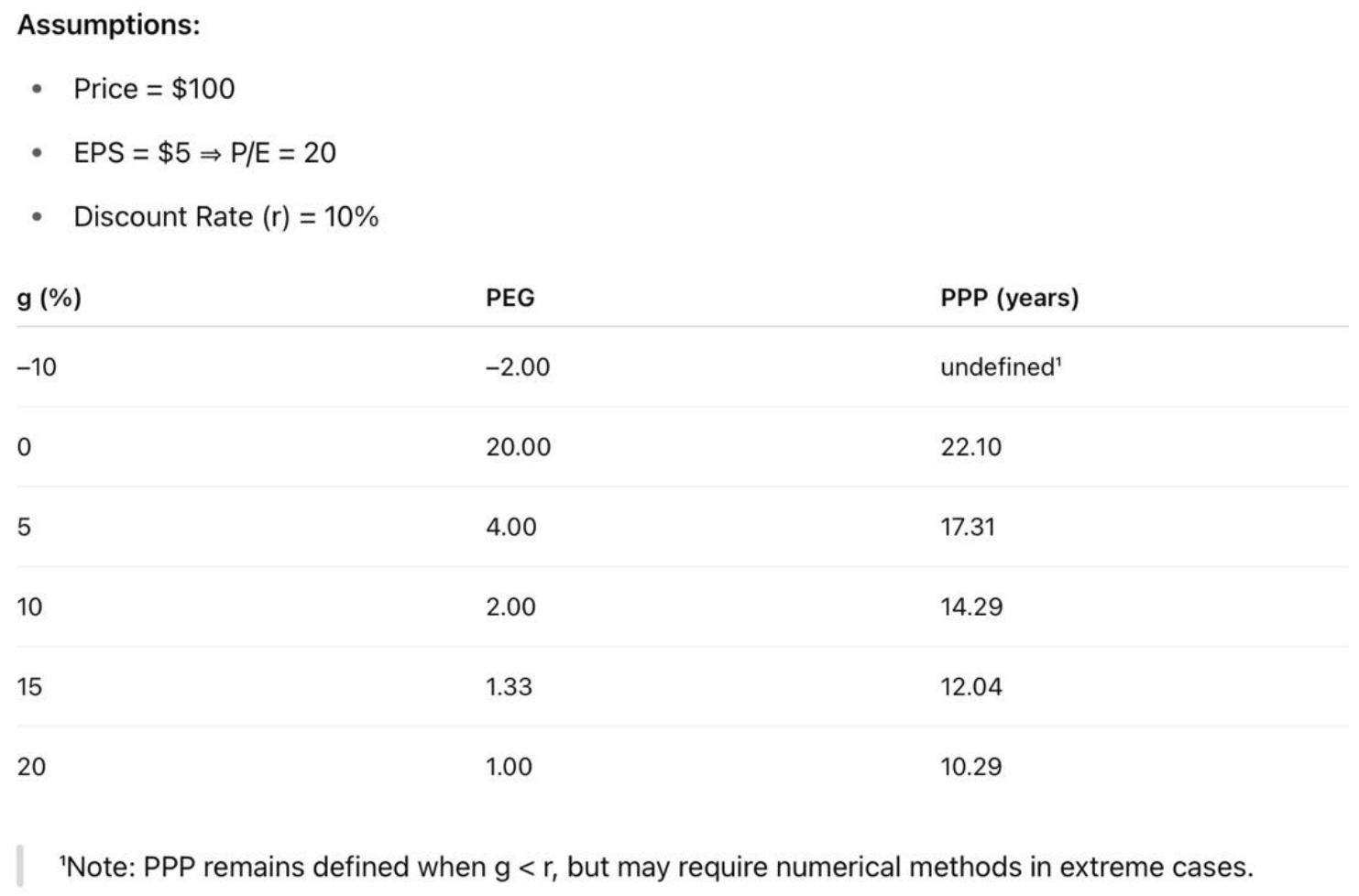

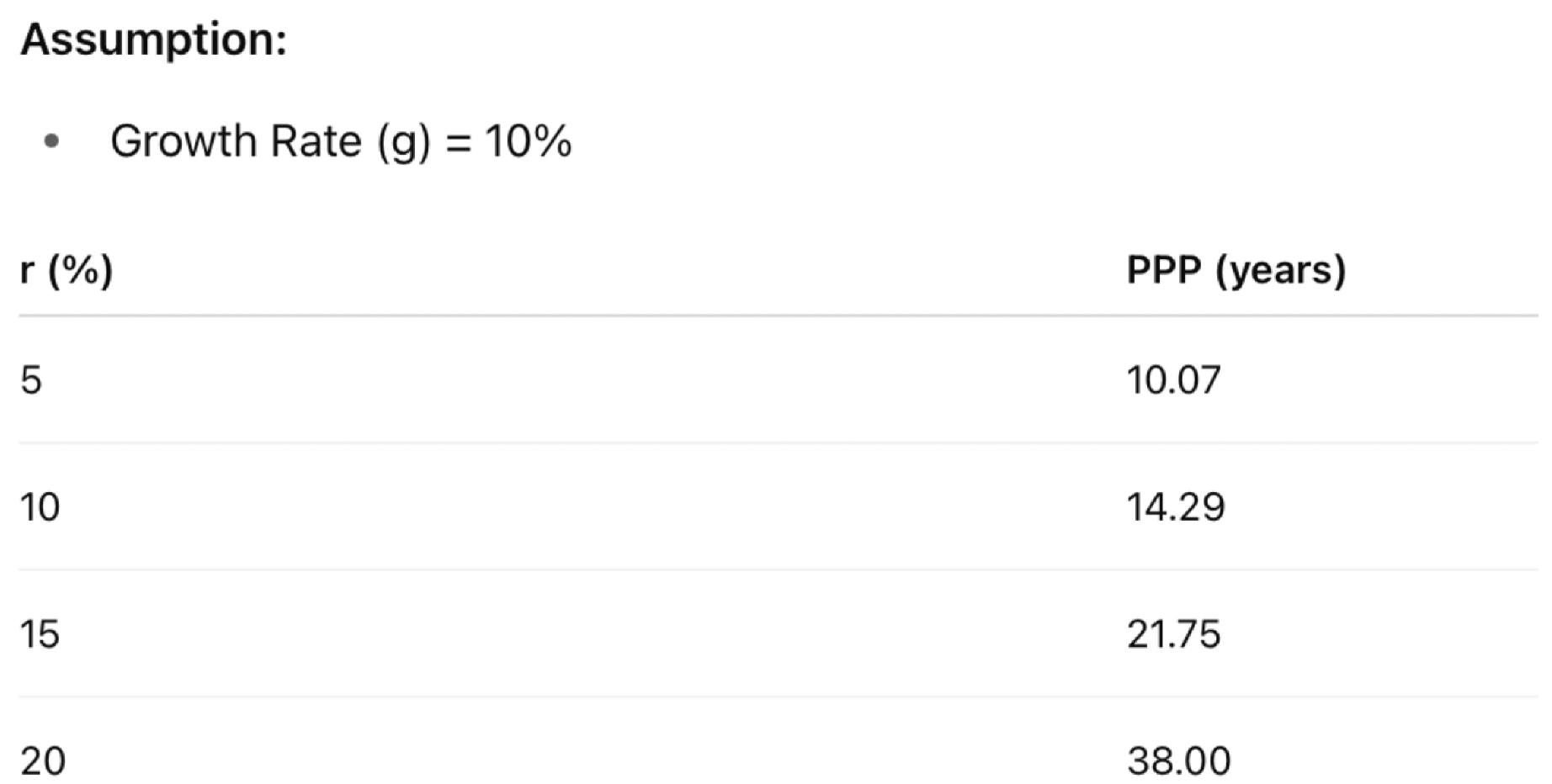

4.2. Illustrative Case: Impact of Growth and Risk on Valuation Metrics

4.3. Application Across Risk Profiles

4.4. Special Cases: When P/E Fails and PPP Persists

- EPS is near zero or negative: P/E becomes undefined or misleading, while PPP can still estimate time to payback based on future expected earnings and discounting.

- Earnings are expected to recover: PPP accommodates forward-looking growth even when current metrics fail.

- Volatile sectors or early-stage companies: PPP enables a time-based view of recovery and return, aiding in scenario analysis and portfolio weighting.

4.5. Summary of Comparative Insights

- Interpretability: P/E and PPP both use a time-based frame. But PPP embeds richer assumptions.

- Adaptability: PPP dynamically adjusts to changes in growth and risk, unlike PEG or P/E.

- Completeness: PPP bridges relative and intrinsic valuation, combining the practical interpretability of multiples with the rigor of discounted models.

5. Practical Implementation

5.1. Estimating Key Inputs: Growth Rate and Discount Rate

5.1.1. Growth Rate (g)

- Analyst forecasts: Aggregated EPS growth estimates from institutional sources (e.g., Bloomberg, FactSet).

- Historical average: Compounded EPS growth over 3–5 years, adjusted for mean reversion.

- Top-down projections: Sector or macro-level growth outlooks allocated to firms proportionally.

- Company guidance: Management’s stated earnings targets or strategic plans.

5.1.2. Discount Rate (r)

- CAPM-derived rate r:

- Hurdle rate: Used in private equity or institutional settings where a minimum return is prescribed.

- Implied market premium: Calibrated to current market valuations or investor sentiment.

5.2. Incorporating Declining or Variable Growth

- Linearly declining growth: Approximate average growth using:

-

Multi-stage growth models: Extend the PPP framework to accommodate piecewise growth assumptions. For example:

- o

- High growth (5 years)

- o

- Transition phase (3 years)

- o

- Terminal growth (stable thereafter)

5.3. Implementation in Screening and Valuation

5.3.1. Screening Use Case

- Rank stocks by shortest PPP (fastest return of capital)

- Filter by sector, risk level, or growth band

- Identify asymmetric opportunities where PPP is low despite high headline P/E.

5.3.2. Full Valuation Integration

- Exit Price estimates: Using terminal EPS and a justified exit P/E

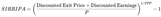

- IRR calculation: Deriving SIRR (Stock Internal Rate of Return) and SIRRIPA (SIRR Including Price Appreciation) directly from PPP and projected earnings streams

- Scenario analysis: Stress-testing changes in g and r to assess valuation robustness.

5.4. Implementation Tools

- Excel or Google Sheets: Straightforward application of the logarithmic formula.

- Python or R: Useful for batch processing and automated screening.

- Plug-ins for valuation platforms: Integration with tools like FactSet, Bloomberg, or Capital IQ via APIs.

6. Applications in Equity Valuation

6.1. PPP as a Screening Metric

- Growth investing: Identify companies with short PPPs despite high P/Es, signaling strong forward earnings potential.

- Deep value: Surface overlooked firms with long PPPs caused by temporarily depressed earnings, but favorable long-term recovery dynamics.

- Cross-sector comparison: Normalize valuation across industries with different growth-risk profiles by translating price and earnings into a common time-based scale.

6.2. Long-Term Return Forecasting (SIRR and SIRRIPA)

6.2.1. Stock Internal Rate of Return (SIRR) – Based on Cumulative Earnings:

6.2.2. Stock Internal Rate of Return Including Price Appreciation (SIRRIPA) – Incorporates Both Cumulative Earnings and an Estimated Exit Price:

6.3. Application to Nontraditional Cases

6.3.1. Low or Negative Earnings

- P/E becomes undefined when EPS is near zero or negative.

- PPP remains defined so long as forward growth in earnings is positive and forecastable.

- Allows valuation of firms in transition, early-stage innovators, or cyclical industries.

6.3.2. Declining Earnings or Negative Growth

- PPP naturally extends to cases where g < r, indicating longer payback periods.

- This behavior flags deteriorating investment prospects in real time, avoiding optimism bias in PEG or static P/E comparisons.

6.3.3. Asymmetric Growth Paths

- Through modifications (e.g., multi-stage growth models), PPP can model complex earnings curves.

- Particularly useful for tech startups, turnaround stories, or firms undergoing restructuring.

6.4. Integration with Institutional Valuation Frameworks

- Quantitative models: Used as a factor in alpha models or ranking algorithms.

- Risk-adjusted valuation: PPP offers a direct link between valuation and cost of capital — providing a consistent metric across varied investment mandates.

- Relative value: Use PPP alongside sector — or index-level averages — to identify over- or under-valued securities.

6.5. Communication and Reporting

- Portfolio managers seeking payback visibility

- Clients and stakeholders needing intuitive justification for investment decisions

- Boards or investment committees evaluating strategic capital allocation.

7. Limitations and Future Research

7.1. Limitations of the PPP Framework

7.1.1. Dependence on Input Accuracy

-

Like all forward-looking models, PPP relies heavily on estimated inputs:

- o

- Growth rate g is inherently uncertain, subject to forecasting errors, optimism bias, or cyclicality.

- o

- Discount rate r, although grounded in CAPM or other models, varies with market sentiment and risk assessments.

- Small changes in g and r can materially affect PPP, particularly when the difference g − r narrows.

7.1.2. Assumption of Constant Growth

- The base PPP formula assumes constant earnings growth over the payback period.

- Real-world companies rarely grow linearly or consistently. Multi-stage or non-linear growth requires adaptation of the model and more complex assumptions.

7.1.3. Interpretation Under Extreme Values

7.1.4. Sensitivity in High-Volatility Sectors

- In highly volatile sectors (e.g., biotech, early-stage tech), short-term earnings are unstable, making PPP inputs less reliable.

- PPP may still function as a long-term indicator, but results must be interpreted with caution and scenario analysis.

7.2. Practical Challenges

- Lack of widespread adoption: PPP is not yet available in mainstream financial terminals or screening tools, limiting its adoption among practitioners.

- Education curve: Investors accustomed to static multiples may require training to understand PPP’s logic, especially its logarithmic and time-value components.

- Computational effort: While formulaic, PPP requires logarithmic computation that may deter use in low-tech or high-frequency contexts without spreadsheet templates or automated tools.

7.3. Future Research Directions

7.3.1. Empirical Validation

- Large-scale empirical studies can compare PPP-based valuation signals to subsequent realized returns.

- Testing across sectors, market cycles, and macroeconomic regimes will clarify its predictive power and robustness.

7.3.2. Multi-Stage PPP Models

-

Extend the framework to accommodate:

- o

- High-growth early phase

- o

- Transitional growth stage

- o

- Mature, stable phase

- This mirrors the structure of DCF modeling but retains PPP’s interpretability.

7.3.3. Stochastic Modeling

- Introduce probabilistic frameworks that allow g and r to follow distributions rather than fixed values.

- This would improve sensitivity analysis and accommodate uncertainty in forecasting.

7.3.4. Behavioral Calibration

7.3.5. Integration with ESG and Intangibles

7.4. Toward Standardization

- Codified into investment platforms and valuation tools

- Included in financial education curricula

- Explored in academic and policy research as a bridge between market efficiency and valuation rationality.

8. Conclusion: From P/E to PPP — A Dynamic Shift in Equity Valuation

- 1 .Remark

- 2.

- Sources directly cited in the article

- Penman, S. H. (1996). The Articulation of Price-Earnings Ratios and Market-to-Book Ratios and the Evaluation of Growth. Journal of Accounting Research, 34(2), 235–259.— Provides a framework connecting P/E and market-to-book ratios with growth expectations, forming a theoretical foundation for equity valuation metrics later refined by models like the PPP.

- Damodaran, A. (2002). Investment Valuation: Tools and Techniques for Determining the Value of Any Asset. Wiley.— Offers comprehensive valuation techniques, including discounted cash flow models, which underpin the theoretical logic extended by the PPP methodology.

- Lee, C. M. C. (2004). Accounting-Based Valuation: Impact on Business Practices and Research. Accounting Horizons, 18(3), 153–157.— Discusses how accounting-based valuation, particularly through P/E and book value, affects both research and practice, which the PPP addresses with a more dynamic framework.

- Easton, P. D. (2004). PE Ratios, PEG Ratios, and Estimating the Implied Expected Rate of Return on Equity Capital. The Accounting Review, 79(1), 73–95.— Analyzes how P/E and PEG ratios imply expected returns, showing limitations that the PPP overcomes through its logarithmic integration of growth, risk, and interest rate.

- Nissim, D., & Penman, S. H. (2001). Ratio Analysis and Equity Valuation: From Research to Practice. Review of Accounting Studies, 6(1), 109–154. — Bridges theoretical valuation ratios and their use in practice, paving the way for enhanced models like the PPP that aim to address empirical shortcomings.

- Ohlson, J. A. (1995). Earnings, Book Values, and Dividends in Equity Valuation. Contemporary Accounting Research, 11(2), 661–687.— Develops a valuation model based on earnings and book values, laying groundwork for more comprehensive approaches like the PPP that incorporate time value and growth.

- 3.

- Other works inspiring the Potential Payback Period (PPP) methodology(Foundational texts that conceptually influenced the development of the PPP)

- Gordon, M. J., & Shapiro, E. (1956). Capital Equipment Analysis: The Required Rate of Profit. Harvard Business Review, 34(5), 102–110.— Provides the foundation for the Gordon Growth Model (GGM), which the PPP extends and surpasses under limiting conditions.

- Gordon, M. J. (1962). The Investment, Financing, and Valuation of the Corporation. Richard D. Irwin, Inc.— Develops the dividend discount model that influenced PPP’s time-discounting structure.

- Sam, R. (2025). Proving that the P/E Ratio is Just a Limiting Case of the Potential Payback Period (PPP) When Earnings Growth and Interest Rate are Ignored.Preprints.— Provides the mathematical proof that PPP generalizes and reduces to the P/E ratio under static conditions.

- Sam, R. (2025). How to Adjust the P/E Ratio for Earnings Growth in Equity Valuation: PEG or PPP? Preprints. — Compares PPP with PEG to show how PPP better integrates growth into valuation.

- Sam, R. (2025). Revisiting the Gordon-Shapiro Model: How the Potential Payback Period (PPP) Refines and Operationalizes a Foundational Framework in Stock Valuation. Preprints. — Demonstrates how PPP refines the structure of the Gordon-Shapiro model by making it applicable in modern contexts.

- Sam, R. (2025). Extending the P/E and PEG Ratios: The Role of the Potential Payback Period (PPP) in Modern Equity Valuation. Preprints. — Positions PPP as a superior alternative to both P/E and PEG ratios in dynamic valuation environments.

- Sam, R. (2025). SIRRIPA: The Stock-Tailored Yield to Maturity (YTM) and the Emergence of a Cross-Asset Valuation Metric. Preprints. — Introduces SIRRIPA as a complement to PPP, bridging equity and fixed-income valuation methodologies.

- Sam, R. (2025). How the Potential Payback Period (PPP) Bridges the Gap Between Stocks and Bonds — and Revolutionizes Portfolio Management. Preprints. — Expands on PPP’s role in creating a unified valuation framework across asset classes.

- Sam, R. (2025). Why SIRRIPA is Set to Replace the P/E Ratio in Modern Equity Valuation. Preprints. — Advocates for a cross-metric valuation system that builds upon PPP-derived logic.

- Sam, R. (2025). Challenging Conventional Wisdom in Stock Valuation with the Potential Payback Period (PPP). SSRN. — Critiques legacy valuation metrics and positions PPP as a more rational, time-sensitive alternative.

- Sam, R. (2025). Breaking the Valuation Deadlock: Replacing the P/E Ratio with the Potential Payback Period (PPP) for Loss-Making Companies – A Case Study on Intel (2025). SSRN. — Applies PPP in contexts where P/E is inapplicable due to negative earnings, showing its practical advantages.

- Damodaran, A. (2012). Investment Valuation: Tools and Techniques for Determining the Value of Any Asset (3rd ed.). Wiley.— Provides foundational DCF and risk-pricing frameworks that underpin PPP’s treatment of discounting.

- Penman, S. H. (2010). Financial Statement Analysis and Security Valuation (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill/Irwin.— Offers techniques for earnings-based valuation, aligned with PPP’s focus on EPS recovery.

- Brealey, R. A., Myers, S. C., & Allen, F. (2017). Principles of Corporate Finance (12th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.— Covers key principles in financial theory including discounting, capital costs, and valuation logic integral to PPP.

- Bodie, Z., Kane, A., & Marcus, A. J. (2018). Investments (11th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.— Discusses risk-return relationships and valuation methodologies that conceptually support PPP's discount-rate framework.

- Copeland, T. E., Koller, T., & Murrin, J. (2000). Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies(3rd ed.). Wiley Finance.— Emphasizes practical DCF techniques and cost of capital, both central to PPP computation.

- Siegel, J. J. (2014). Stocks for the Long Run (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.— Advocates for long-term valuation strategies, compatible with PPP’s time-recovery approach.

- Greenwald, B., Kahn, J., Sonkin, P. D., & van Biema, M. (2001). Value Investing: From Graham to Buffett and Beyond. Wiley.— Reinforces intrinsic value investing principles that PPP seeks to quantify more rigorously.

- Graham, B., & Dodd, D. L. (2008). Security Analysis (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.— A foundational text on valuation that influenced PPP’s emphasis on earnings and intrinsic value.

- Miller, M. H., & Modigliani, F. (1961). Dividend Policy, Growth, and the Valuation of Shares. Journal of Business, 34(4), 411–433.— Established valuation equivalence principles that underlie PPP's sensitivity to growth and discounting.

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1992). The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns. Journal of Finance, 47(2), 427–465.— Provides empirical insights on return factors, supporting PPP’s incorporation of discount-rate-driven expectations.

- Arnott, R. D., & Bernstein, P. L. (2002). What Risk Premium Is “Normal”? Financial Analysts Journal, 58(2), 64–85.— Explores variability in equity risk premiums, essential for interpreting PPP's discounting logic.

- Koller, T., Goedhart, M., & Wessels, D. (2020). Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies (7th ed.). McKinsey & Company / Wiley.— Offers contemporary valuation frameworks that PPP helps to extend under extreme or unconventional conditions.

- Sam, R. (2025). Stock Internal Rate of Return — The Official Website on the Potential Payback Period (PPP) Methodology. www.stockinternalrateofreturn.com— Serves as the central hub for the PPP methodology, providing comprehensive resources, conceptual foundations, practical tools, and ongoing updates related to PPP, SIRR, SPARR, SIRRIPA, and SRP valuation metrics.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).