Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Analyses of Variance

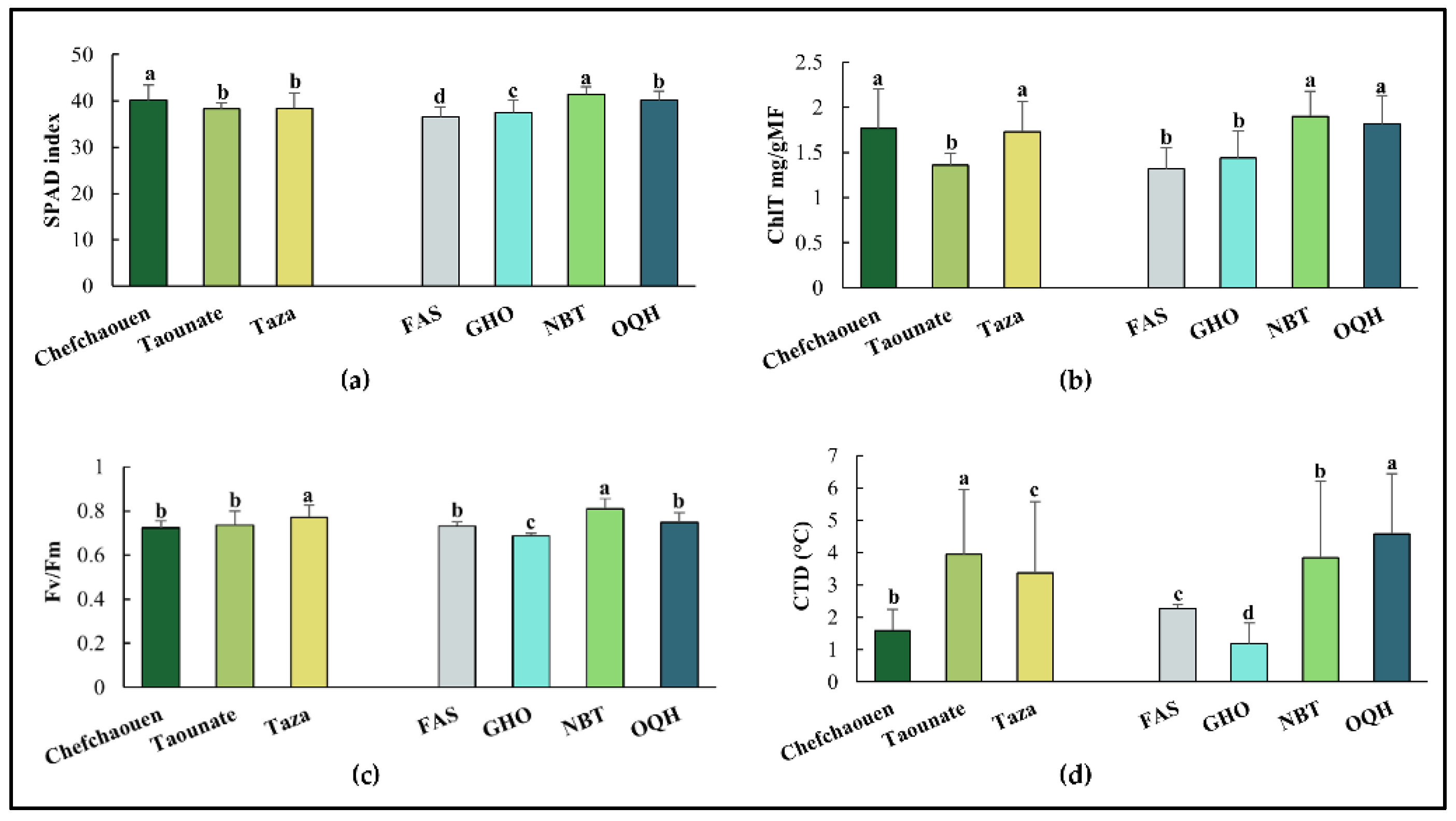

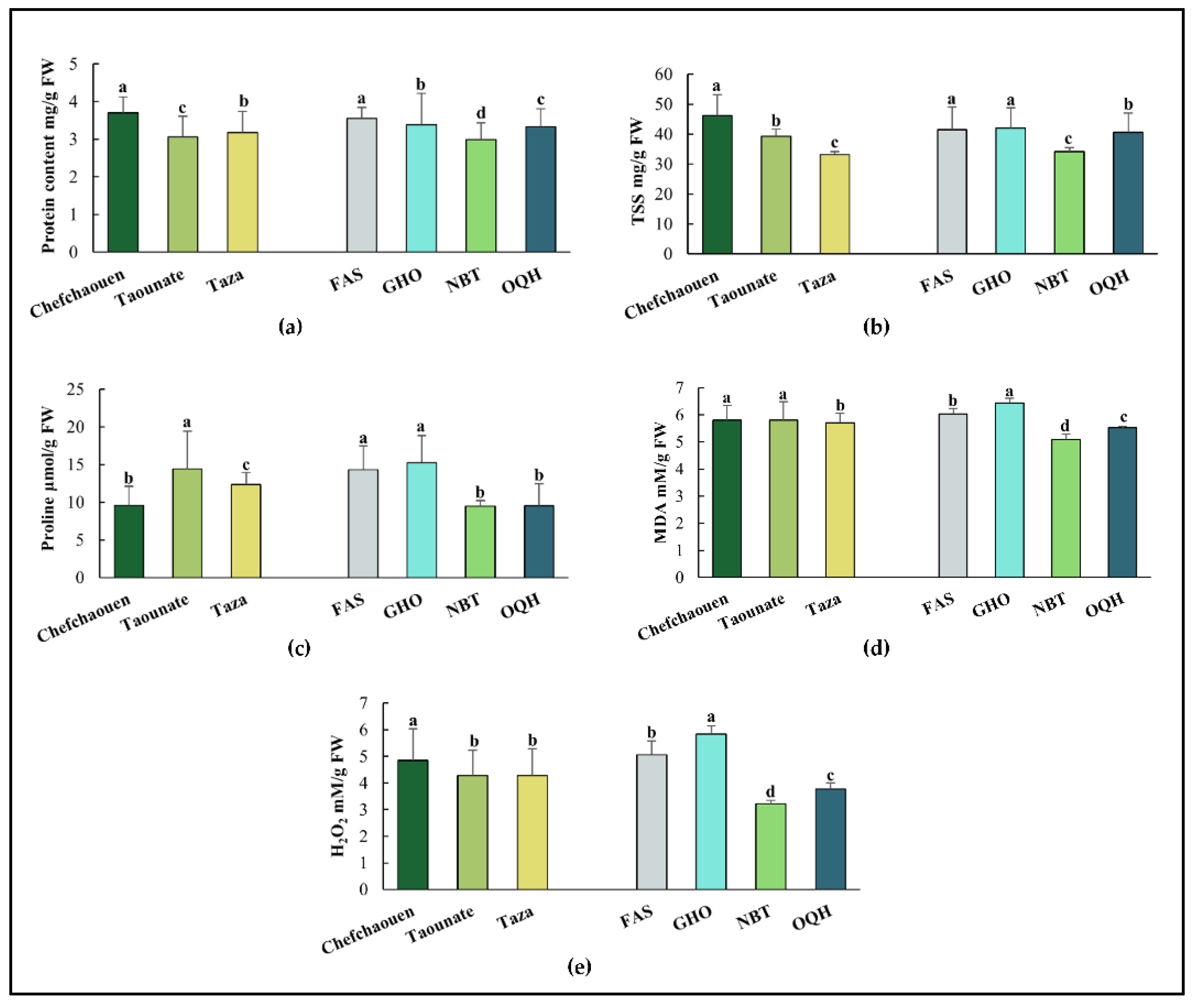

2.2. Effect of Location and Variety

2.3. Relationships Between Parameters

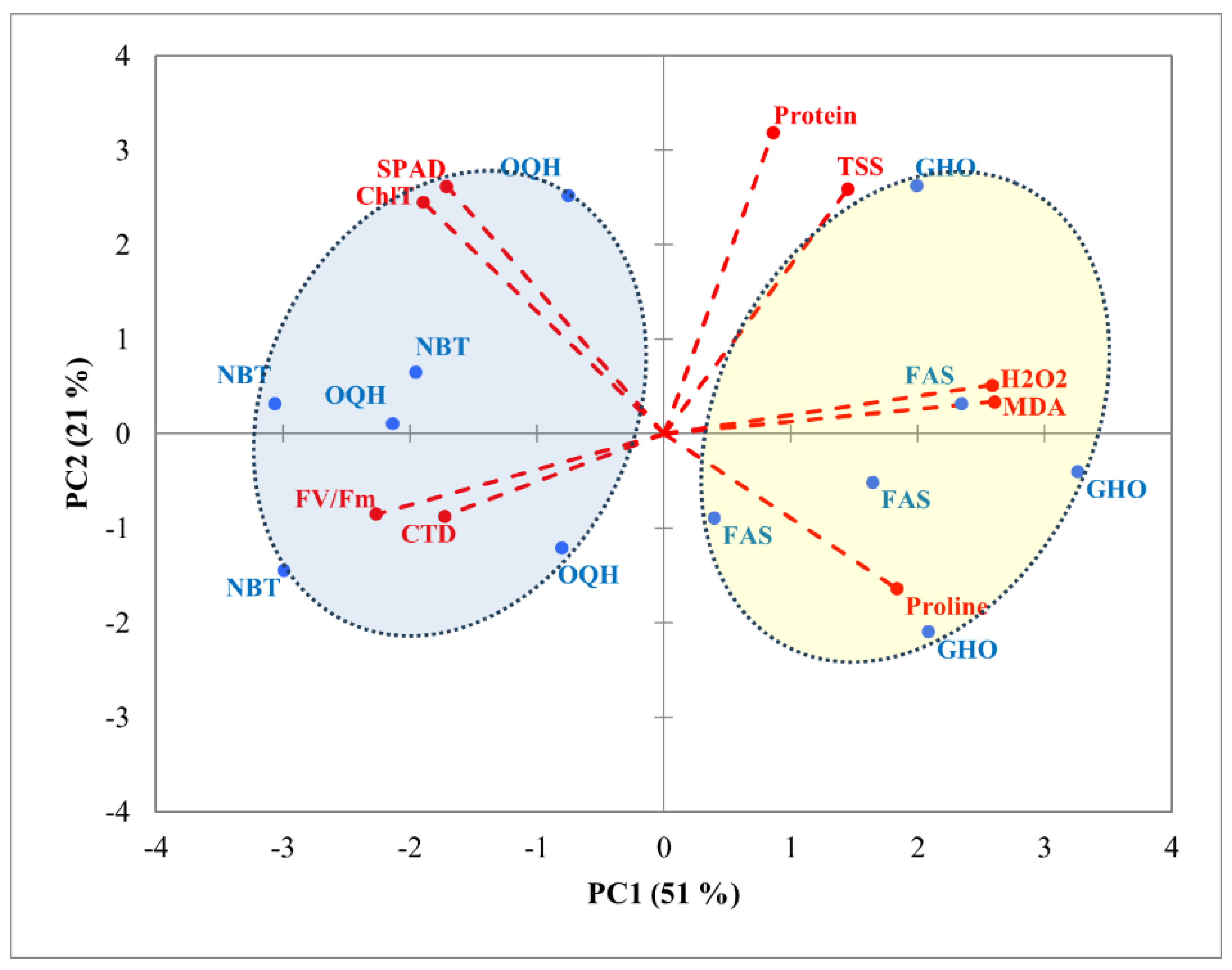

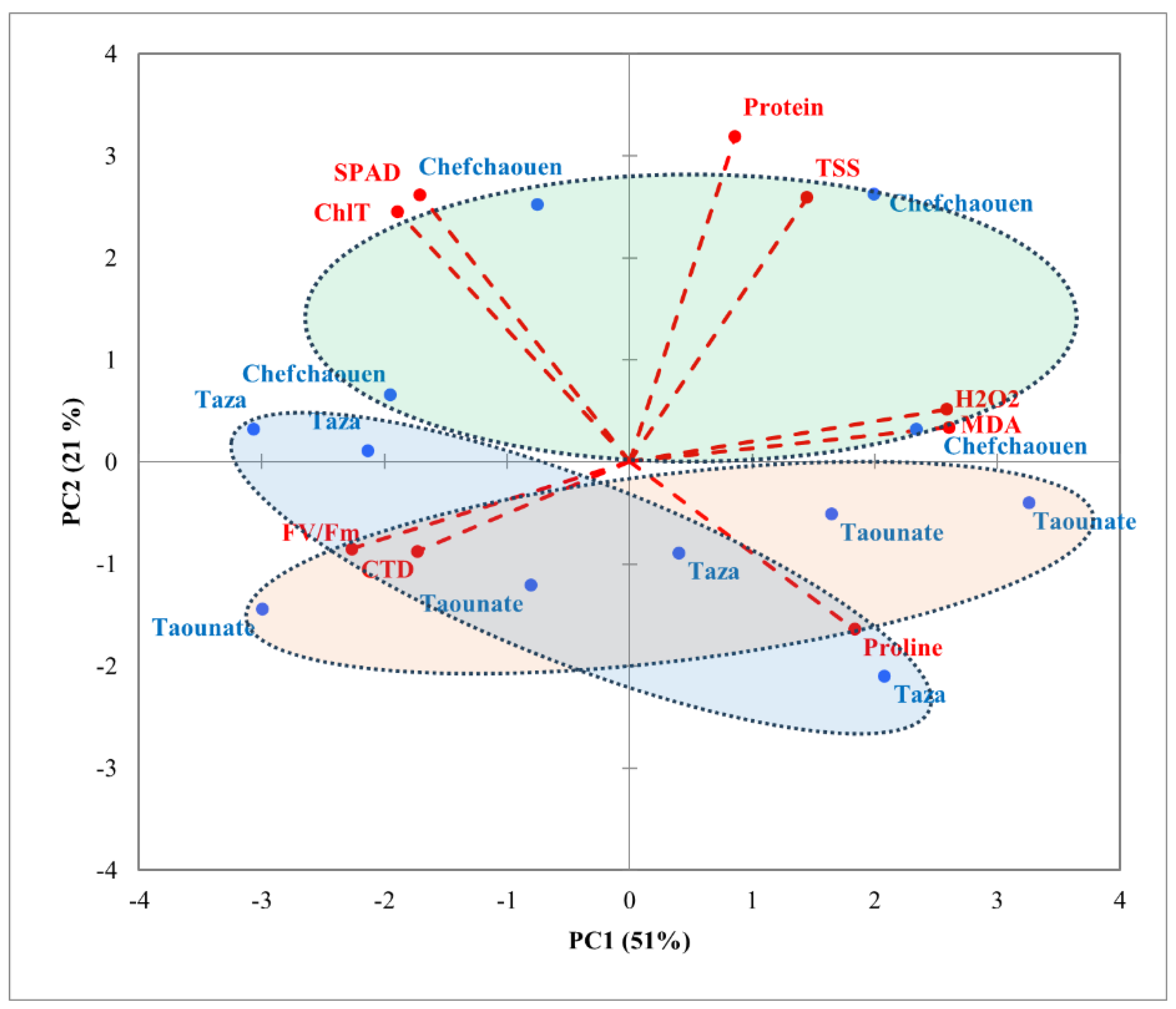

2.4. Principal Component Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

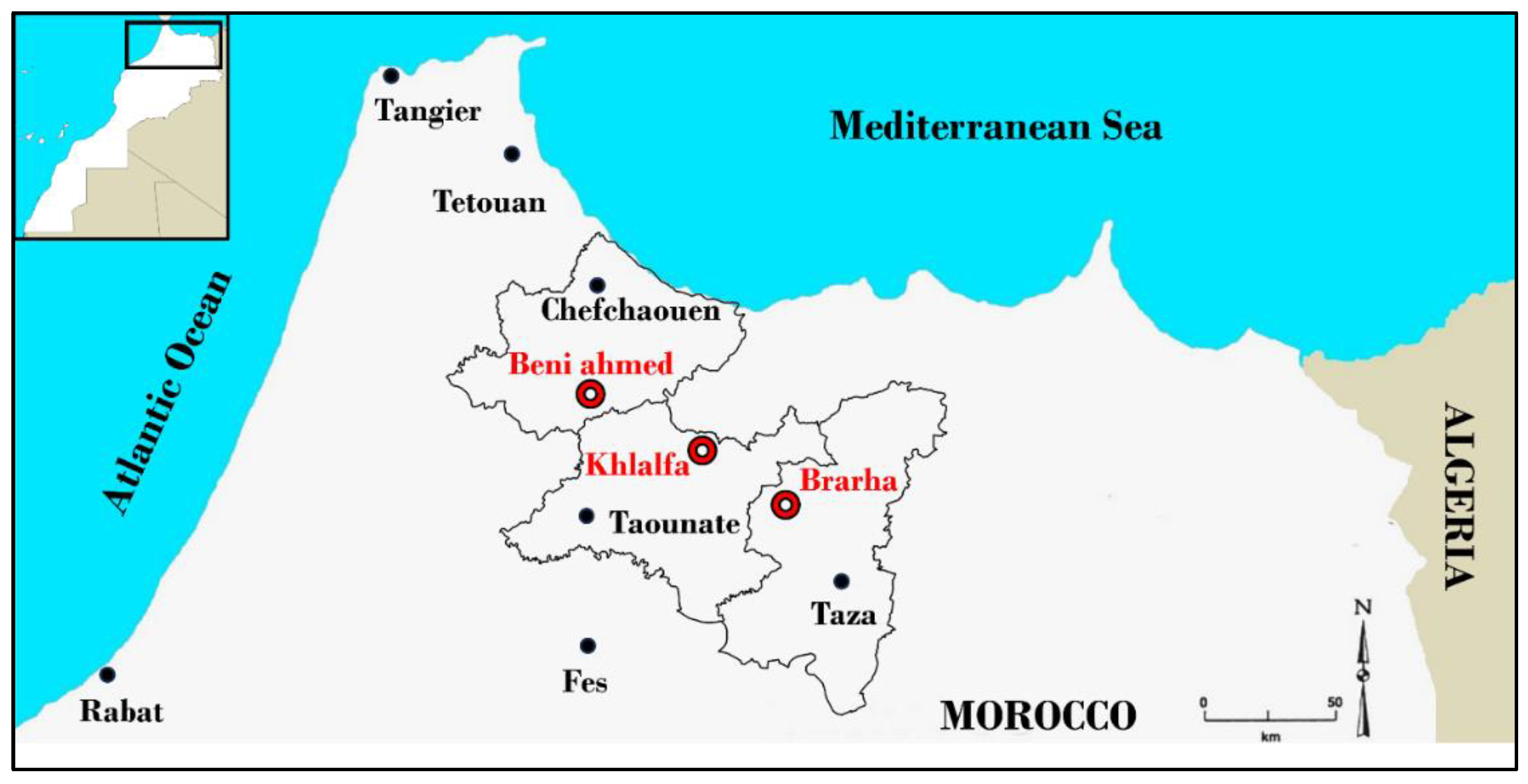

4.1. Plant Samples

4.2. Physiological Traits Determination

4.2.1. Chlorophyll Fluorescence (Fv/Fm)

4.2.2. SPAD Index

4.2.3. Total Chlorophyll Content (ChlT)

4.2.4. Canopy Temperature Depression (CTD)

4.3. Biochemical Traits Determination

4.3.1. Proline Content

4.3.2. Total Soluble Sugars (TSS)

4.3.3. Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2)

4.3.4. Malondialdehyde (MDA)

4.3.5. Protein Content

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hao, G.-Y.; Goldstein, G.; Sack, L.; Holbrook, N.; Liu, Z.-H.; Wang, A.-Y.; Harrison, R.; Su, Z.-H.; Cao, K.-F. Ecology of Hemiepiphytism in Fig Species Is Based on Evolutionary Correlation of Hydraulics and Carbon Economy. Ecology 2011, 92, 2117–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellal, M.K.; Khelifa, R.; Chelli, A.; Djouadi, N.; Madani, K. Combined Effects of Climate and Pests on Fig (Ficus Carica L.) Yield in a Mediterranean Region: Implications for Sustainable Agricultural Strategies. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xu, R.; Peng, Y. Research Progress of Interspecific Hybridization in Genus Ficus. Biodiversity Science 2019, 27, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaishman, M. Horticultural Practices under Various Climatic Conditions. In; 2022; pp. 117–138. ISBN 978-1-78924-247-8.

- Crisosto, H.; Ferguson, L.; Bremer, V.; Stover, E.; Colelli, G. 7 - Fig (Ficus Carica L.). In Postharvest Biology and Technology of Tropical and Subtropical Fruits; Yahia, E.M., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Woodhead Publishing, 2011; pp. 134–160e. ISBN 978-1-84569-735-8.

- Stover, E.; Aradhya, M.; Ferguson, L.; Crisosto, C. The Fig: Overview of an Ancient Fruit. HortScience 2007, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maatallah, S.; Guizani, M.; Lahbib, K.; Montevecchi, G.; Santunione, G.; Hessini, K.; Dabbou, S. Physiological Traits, Fruit Morphology and Biochemical Performance of Six Old Fig Genotypes Grown in Warm Climates “Gafsa Oasis” in Tunisia. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2024, 17, 101253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micheloud, N.; Gabriel, P.; Favaro, J.C.; Gariglio, N. Agronomic Strategies for FigFig CultivationCultivation in a Temperate-Humid Climate Zone. In Fig (Ficus carica): Production, Processing, and Properties; Ramadan, M.F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 193–214. ISBN 978-3-031-16493-4. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, F.S.O.; Pereira, E.C.; Mendonça, V.; Da Silva, R.M.; Alves, A.A. Phenology and Yield of the ‘Roxo de Valinhos’ Fig Cultivar in Western Potiguar. Revista Caatinga 2017, 30, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veberic, R.; Colaric, M.; Stampar, F. Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids of Fig Fruit (Ficus Carica L.) in the Northern Mediterranean Region. Food Chemistry 2008, 106, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistiques| FAO | Organisation des Nations Unies pour l'alimentation et l'agriculture. Available online: http://www.fao.org/statistics/fr (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Oukabli A; Mamouni A Fiche Technique Figuier (Ficus Carica L.), Installation et Conduite Technique de La Culture, Institut de La Recherche Agronomique, Maroc. 2008.

- Walali, L.; Skiredj, A.; Alattir, H. Fiches Techniques: L’amandier, l’olivier, Le Figuier, Le Grenadier; Bulletin de Transfert de Technologie en Agriculture, 105, 2003, 2003.

- Achtak, H.; Ater, M.; Oukabli, A.; Santoni, S.; Kjellberg, F.; Khadari, B. Traditional Agroecosystems as Conservatories and Incubators of Cultivated Plant Varietal Diversity: The Case of Fig (Ficus caricaL.) in Morocco. BMC Plant Biology 2010, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmimsa, Y.; Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y.; Ater, M. Vernacular Taxonomy, Classification and Varietal Diversity of Fig (Ficus Carica L.) Among Jbala Cultivators in Northern Morocco. Human Ecology 2012, 40, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hssaini, L.; Hanine, H.; Razouk, R.; Ennahli, S.; Mekaoui, A.; Ejjilani, A.; Charafi, J. Assessment of Genetic Diversity in Moroccan Fig (Ficus Carica L.) Collection by Combining Morphological and Physicochemical Descriptors. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 2020, 67, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikent, A.; Marhri, A.; Mihamou, A.; Sahib, N.; Serghini-Caid, H.; Elamrani, A.; Abid, M.; Addi, M. Phenotypic Polymorphism, Pomological and Chemical Characteristics of Some Local Varieties of Fig Trees (Ficus Carica L.) Grown in Eastern Morocco. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences, January 20 2022; Vol. 337. [Google Scholar]

- Hajjam, A.E.; Ezzahouani, A.; Sehhar, E.A. Conduite Technique et Inventaire Des Variétés Marocaines Locales de Figuier (Ficus Carica L.) Dans Quatre Principaux Sites de Production, Provinces de Chefchaouen, El Jadida, Ouezzane, et Taounate; 2018.

- Khadari, B.; Roger, J.P.; Ater, M.; Achtak, H.; Oukabli, A.; Kjellberg, F. Moroccan Fig Presents Specific Genetic Resources: A High Potential of Local Selection. In Proceedings of the Acta Horticulturae; International Society for Horticultural Science, 2008; Vol. 798, pp. 33–37.

- Hmimsa, Y.; Ramet, A.; Dubuisson, C.; El Fatehi, S.; Hossaert-McKey, M.; Kahi, H.; Munch, J.; Proffit, M.; Salpeteur, M.; Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y. Pollination of the Mediterranean Fig Tree, Ficus Carica L.: Caprification Practices and Social Networks of Exchange of Caprifigs among Jbala Farmers in Northern Morocco. Human Ecology 2024, 52, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafrica, R.; Bruno, M.; Fiozzo, V.; Caridi, R.; Sorgonà, A. Rooting, Growth, and Root Morphology of the Cuttings of Ficus Carica L. (Cv. “Dottato”): Cutting Types and Length and Growth Medium Effects. Plants 2025, 14, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, F.; Aksoy, U.; Özer, K.B.; Can, H.; Konak, R. Effect of Altitudes on Physical and Chemical Properties of Sun-Dried Fig ( Ficus Carica ‘Sarılop’) Fruit. Acta Horticulturae 2021, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trad, M.; Gaaliche, B.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Mars, M. Inter- and Intra-Tree Variability in Quality of Figs. Influence of Altitude, Leaf Area and Fruit Position in the Canopy. Scientia Horticulturae 2013, 162, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.; Ben Aissa, I.; Mars, M.; Gouiaa, M. Comparative Physiological Behavior of Fig (Ficus Carica L.) Cultivars in Response to Water Stress and Recovery. Scientia Horticulturae 2020, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar Arouaand Ben Aissa, I. and Z.F. and G.M. and M.M. Physiological Behaviour of Fig Tree (Ficus Carica L.) Under Different Climatic Conditions. In Fig (Ficus carica): Production, Processing, and Properties; Ramadan, M.F., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 247–257. ISBN 978-3-031-16493-4. [Google Scholar]

- Vemmos, S.N.; Petri, E.; Stournaras, V. Seasonal Changes in Photosynthetic Activity and Carbohydrate Content in Leaves and Fruit of Three Fig Cultivars (Ficus Carica L.). Scientia Horticulturae 2013, 160, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolinejad, R.; Shekafandeh, A. Tetraploidy Confers Superior in Vitro Water-Stress Tolerance to the Fig Tree (Ficus Carica) by Reinforcing Hormonal, Physiological, and Biochemical Defensive Systems. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 12, 796215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swoczyna, T.; Kalaji, H.M.; Bussotti, F.; Mojski, J.; Pollastrini, M. Environmental Stress - What Can We Learn from Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Analysis in Woody Plants? A Review. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi Alagoz, S.; Asgari Lajayer, B.; Ghorbanpour, M. Chapter 10 - Proline and Soluble Carbohydrates Biosynthesis and Their Roles in Plants under Abiotic Stresses. In Plant Stress Mitigators; Ghorbanpour, M., Adnan Shahid, M., Eds.; Academic Press, 2023; pp. 169–185 ISBN 978-0-323-89871-3.

- El Yamani, M.; Sakar, E.H.; Boussakouran, A.; Rharrabti, Y. Leaf Water Status, Physiological Behavior and Biochemical Mechanism Involved in Young Olive Plants under Water Deficit. Scientia Horticulturae 2020, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussakouran, A.; El Yamani, M.; Sakar, E.H.; Rharrabti, Y. Genetic Advance and Grain Yield Stability of Moroccan Durum Wheats Grown under Rainfed and Irrigated Conditions. International Journal of Agronomy 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, H.; Meyvaci, K.B.; Balcı, B. Determination of Gas Exchange Capacity of Some Breba Fig Cultivars. Acta Horticulturae 2008, 798, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Liu, Z.; Guo, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yu, Q.; Wang, J.; Zheng, F.; Lu, X. Relationship between Photosynthetic CO2 Assimilation and Chlorophyll Fluorescence for Winter Wheat under Water Stress. Plants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Yin, T.; He, H.; Liu, X.; Long, X.; Dong, P.; Zhu, Z. Phenotypic, Metabolic and Genetic Adaptations of the Ficus Species to Abiotic Stress Response: A Comprehensive Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Q.; Huang, W.; Jarvis, P. Use of a SPAD-502 Meter to Measure Leaf Chlorophyll Concentration in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Photosynthesis Research 2011, 107, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardinata, Z.; Edy Sabli, T.; Ulpah, S. Biochemical Responses and Leaf Gas Exchange of Fig (Ficus Carica l.) to Water Stress, Short-Term Elevated Co2 Levels and Brassinolide Application. Horticulturae 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Priya, M.; Bindumadhava, H.; Nair, R.M.; Nayyar, H. Influence of High Temperature Stress on Growth, Phenology and Yield Performance of Mungbean [Vigna Radiata (L.) Wilczek] under Managed Growth Conditions. Scientia Horticulturae 2016, 213, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rosario Jacobo-Salcedo, M.; Valdez-Cepeda, R.D.; Sánchez-Cohen, I.; González-Espíndola, L.; Arreola-ávila, J.G.; Trejo-Calzada, R. Physiological Mechanisms in Ficus Carica L. Genotypes in Response to Moisture Stress. Agronomy Research 2024, 22, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivcak, M.; Brestic, M.; Kalaji, H.M. ; Govindjee Photosynthetic Responses of Sun- and Shade-Grown Barley Leaves to High Light: Is the Lower PSII Connectivity in Shade Leaves Associated with Protection against Excess of Light? Photosynthesis Research 2014, 119, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaji, H.M.; Carpentier, R.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Bosa, K. Fluorescence Parameters as Early Indicators of Light Stress in Barley. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2012, 112, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlinarić, S.; Antunović Dunić, J.; Štolfa, I.; Cesar, V.; Lepeduš, H. High Irradiation and Increased Temperature Induce Different Strategies for Competent Photosynthesis in Young and Mature Fig Leaves. South African Journal of Botany 2016, 103, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verslues, P.E.; Agarwal, M.; Katiyar-Agarwal, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, J.K. Methods and Concepts in Quantifying Resistance to Drought, Salt and Freezing, Abiotic Stresses That Affect Plant Water Status. Plant Journal 2006, 45, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S. Response Mechanism of Plants to Drought Stress. Horticulturae 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valluru, R.; Van Den Ende, W. Plant Fructans in Stress Environments: Emerging Concepts and Future Prospects. Journal of Experimental Botany 2008, 59, 2905–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussakouran, A.; El Yamani, M.; Sakar, E.H.; Rharrabti, Y. Genetic Progress in Physiological and Biochemical Traits Related to Grain Yield in Moroccan Durum Wheat Varieties from 1984 to 2007. Crop Science 2022, 62, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wani, A.S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of Proline under Changing Environments: A Review. Plant Signaling and Behavior 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhraoua, S.; Ferioun, M.; Nassira, S.; Boussakouran, A.; Akhazzane, M.; Belahcen, D.; Hammani, K.; Louahlia, S. Biomass Partitioning and Physiological Responses of Four Moroccan Barley Varieties Subjected to Salt Stress in a Hydroponic System. Journal of Plant Biotechnology 2023, 50, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferioun, M.; Bouhraoua, S.; Belahcen, D.; Zouitane, I.; Srhiouar, N.; Louahlia, S.; El Ghachtouli, N. PGPR Consortia Enhance Growth and Yield in Barley Cultivars Subjected to Severe Drought Stress and Subsequent Recovery. Rhizosphere 2024, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, I.M.; Jensen, P.E.; Hansson, A. Oxidative Modifications to Cellular Components in Plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2007, 58, 459–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnocka, W.; Karpiński, S. Friend or Foe? Reactive Oxygen Species Production, Scavenging and Signaling in Plant Response to Environmental Stresses. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2018, 122, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.; Wani, S.H. Reactive Oxygen Species Generation, Scavenging and Signaling in Plant Defense Responses. In Bioactive Molecules in Plant Defense: Signaling in Growth and Stress; Jogaiah, S., Abdelrahman, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 111–132. ISBN 978-3-030-27165-7. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, F.K.; Rivero, R.M.; Blumwald, E.; Mittler, R. Reactive Oxygen Species, Abiotic Stress and Stress Combination. Plant Journal 2017, 90, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Armin, S.M.; Qian, P.; Xin, W.; Li, H.Y.; Burritt, D.J.; Fujita, M.; Tran, L.S.P. Hydrogen Peroxide Priming Modulates Abiotic Oxidative Stress Tolerance: Insights from ROS Detoxification and Scavenging. Frontiers in Plant Science 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zivcak Marekand Olsovska, K. and B.M. Photosynthetic Responses Under Harmful and Changing Environment: Practical Aspects in Crop Research. In Photosynthesis: Structures, Mechanisms, and Applications; Hou Harvey J.M.and Najafpour, M.M. and M.G.F. and A.S.I., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2017; pp. 203–248. ISBN 978-3-319-48873-8. [Google Scholar]

- Uddling, J.; Gelang-Alfredsson, J.; Piikki, K.; Pleijel, H. Evaluating the Relationship between Leaf Chlorophyll Concentration and SPAD-502 Chlorophyll Meter Readings. Photosynthesis Research 2007, 91, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnison, B.K. Modified Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) Extraction for Chlorophyll Analysis of Phytoplankton. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 1980, 37, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid Determination of Free Proline for Water-Stress Studies. Plant and Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. A Colorimetric Method for the Determination of Sugars. Nature 1951, 168, 167–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, U.; Oba, S. Drought Stress Effects on Growth, ROS Markers, Compatible Solutes, Phenolics, Flavonoids, and Antioxidant Activity in Amaranthus Tricolor. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2018, 186, 999–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, U.; Islam, M.T.; Rabbani, M.G.; Oba, S. Variability, Heritability and Genetic Association in Vegetable Amaranth (Amaranthus Tricolor L.). Spanish Journal of Agricultural Research 2015, 13, e0702–e0702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variation | Df | SPAD | ChlT | FV/Fm | CTD | Proline | Protein | TSS | H₂O₂ | MDA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | 2 | 13.264*** | 0.614*** | 0.00751*** | 18.0123*** | 70.926*** | 1.4238*** | 5.137*** | 1.293*** | 0.0398*** |

| Variety | 3 | 47.284*** | 0.718*** | 0.02358*** | 21.0292*** | 85.12*** | 0.4952*** | 1.2196*** | 12.764*** | 3.2001*** |

| Replicate | 2 | 0.285 | 0.018 | 0.00005 | 0.0003 | 0.929 | 0.0011 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.0008 |

| Location*Variety | 6 | 22.850*** | 0.239*** | 0.00366*** | 8.1465*** | 19.706*** | 1.3355*** | 0.469*** | 0.208*** | 0.1545*** |

| Residual | 22 | 0.187 | 0.010 | 0.00022 | 0.0006 | 1.457 | 0.0009 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.0007 |

| Total (corrected) | 35 |

| SPAD | ChlT | Fv/Fm | CTD | Protein | TSS | Proline | H2O2 | MDA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPAD | 0.834*** | 0.299 | 0.216 | 0.186 | -0.051 | -0.433** | -0.543*** | -0.502*** | |

| ChlT | 0.356* | 0.153 | 0.188 | -0.229 | -0.552*** | -0.556*** | -0.570*** | ||

| Fv/Fm | 0.652*** | -0.223 | -0.499*** | -0.456** | -0.732*** | -0.761*** | |||

| CTD | -0.160 | -0.263 | -0.295 | -0.633*** | -0.509*** | ||||

| Protein | 0.556*** | 0.080 | 0.351* | 0.426* | |||||

| TSS | -0.113 | 0.580*** | 0.488*** | ||||||

| Proline | 0.492*** | 0.683*** | |||||||

| H2O2 | 0.930*** | ||||||||

| MDA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).