1. Introduction

Incremental sheet forming (ISF) fits into the context of highly flexible technologies, such as additive manufacturing, stimulated by recent significant advances in computer applications in manufacturing [

1]. This materials processing technology exhibits several unique characteristics, such as reduced tooling, cycle time, and cost.

The principal concept of ISF in its basic variant involves the progressive deformation of a clamped material sheet by a simple, non-dedicated forming tool, guided by a CNC machine, which follows a path to incrementally deform the sheet into the final shape [

2]. Thanks to the layered manufacturing principle typical of rapid prototyping, it allows for the high customization of small-batch, non-axisymmetric sheet products [

3], with potential applications in aerospace, automotive, and other fields [

4,

5].

Early research on ISF has mainly focused on metals and their alloys, with several articles and reviews published on the topic. For example, initial overviews of the process [

6] have been followed by more recent literature reviews detailing scientific progress and future developments [

7,

8,

9]. Other papers have focused on specific topics such as formability [

10], deformation [

11] and failure mechanisms [

12], and analyses of forming forces [

13]. Additionally, other works have investigated the applications of ISF for metal parts [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Recently, research has shown increased interest in hard-to-form non-metallic materials, particularly thermoplastic polymers [

19,

20,

21]. Thermoplastics exhibit desirable properties (light weight, strength, corrosion resistance, and cost-effectiveness, among others) making them widely used for mass production [

22]. ISF can represent a viable alternative to conventional processes for these materials, which require repetitive heating, shaping, and cooling actions [

23,

24]. However, progress in ISF of composites has not been significantly reviewed or documented. Some preliminary studies have been conducted on the incremental forming of sandwich panels [

25] and composite materials [

26], as well as on advances in ISF of common polymer-based composite materials reinforced with glass [

27] and carbon fibers [

28]. Nonetheless, it is evident that there is an urgent need to deepen knowledge in this area, especially as industries seek alternative, sustainable, and cost-effective solutions for processing composite materials [

29].

An area of recent significant interest, both in research and on an industrial scale, is the manufacture of polymer composites using natural fibers as reinforcement [

30]. These fibers represent an inexpensive, biodegradable, renewable, and nontoxic alternative to the most common synthetic fillers (glass and carbon fibers) [

31]. They enhance certain properties of commercial polymers, reduce energy consumption, and make them semi-biodegradable [

32]. Hemp and flax are the strongest and stiffest natural fibers, as well as two of the most popular and widely available fibers in European countries. They are composed of several elementary fibers that are glued together by a middle lamella mainly of pectin [

33]. These fibers exhibit low density and high specific stiffness compared to glass or aramid fibers and are commonly used for the manufacture of biocomposites [

34]. Flax is widely cultivated in countries with cold and moist climates that promote its short growing cycle, such as Canada, Russia, France, and Belgium. Hemp has a very rapid growth cycle of only 3.5 months, high dry biomass production (4–5 times higher than that produced by a forest of the same area in one year), and high carbon storage potential [

35].

Polypropylene (PP), thanks to its high chemical and wear resistance, excellent mechanical properties, ease of processing, and cost-effectiveness [

36], is the world's second-most widely produced synthetic polymer. It is employed in various industrial applications, including automotive parts, reusable containers, packaging, and laboratory equipment [

37]. PP is strongly considered for advanced composites in aerospace, civil, and automotive fields [

38] and currently dominates as a matrix for natural composites, along with polyethylene and polyvinyl chloride [

39].

This work presents an experimental campaign of ISF tests for the manufacture of cones and spherical caps, starting from hemp and flax fiber-reinforced PP laminate composites. By observing failures and defects, it determines the formability of these composite materials. Additionally, energy considerations were made through the evaluation of forming forces. In doing so, it identifies potential applications and outlines directions for future research in the field of ISF of natural fiber-reinforced composites.

2. Materials and Methods

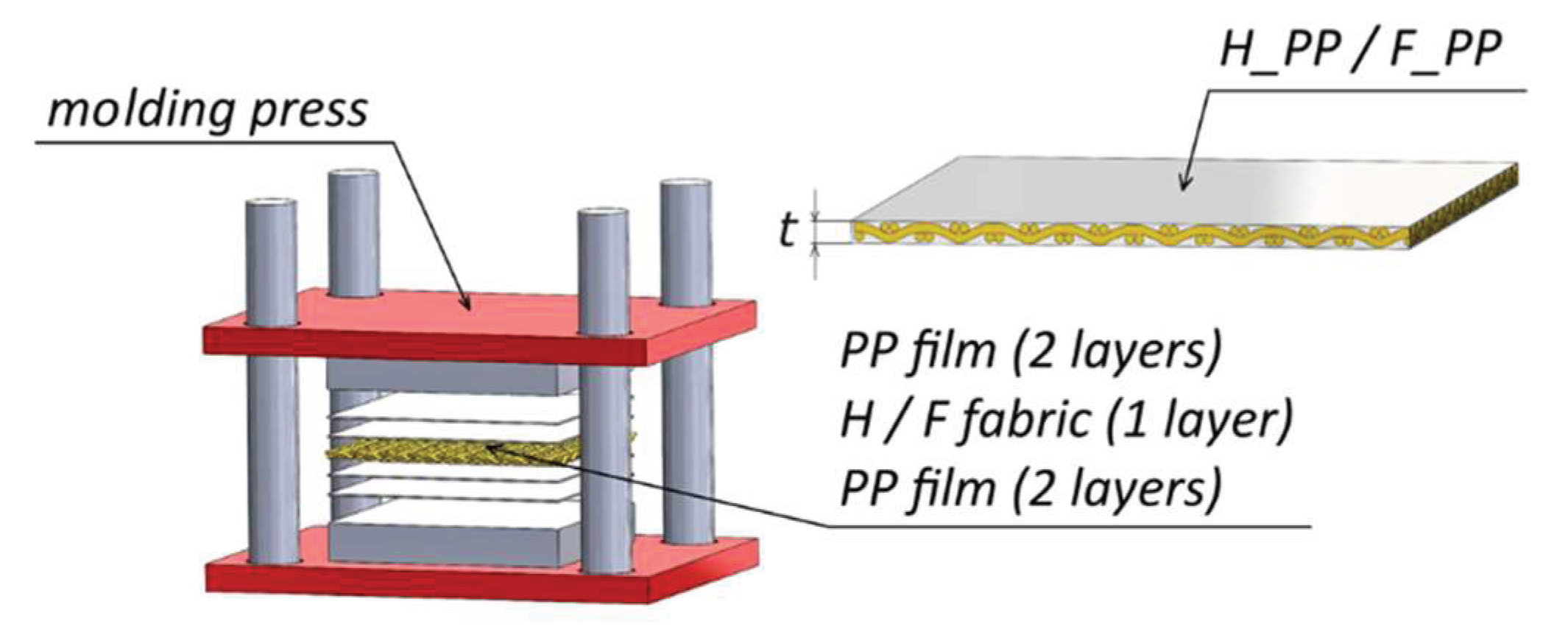

The laminates employed in this study were natural long hemp and flax fiber-reinforced PP composites, labelled as H_PP and F_PP respectively, with a thickness

t = 2.2 mm. They were manufactured through a molding process at 200°C for a total time of 5 min, using PP films (supplied by GDC S.r.l.; thickness of 0.5 mm and density of 0.92 g/cm

3) and hemp and flax fabrics, supplied by FIDIA S.r.l. - Technical Global Services. The main properties of the fibers (both single unimpregnated yarn and fabric) are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2, while a schematic of the molding process and the layup is shown in

Figure 1.

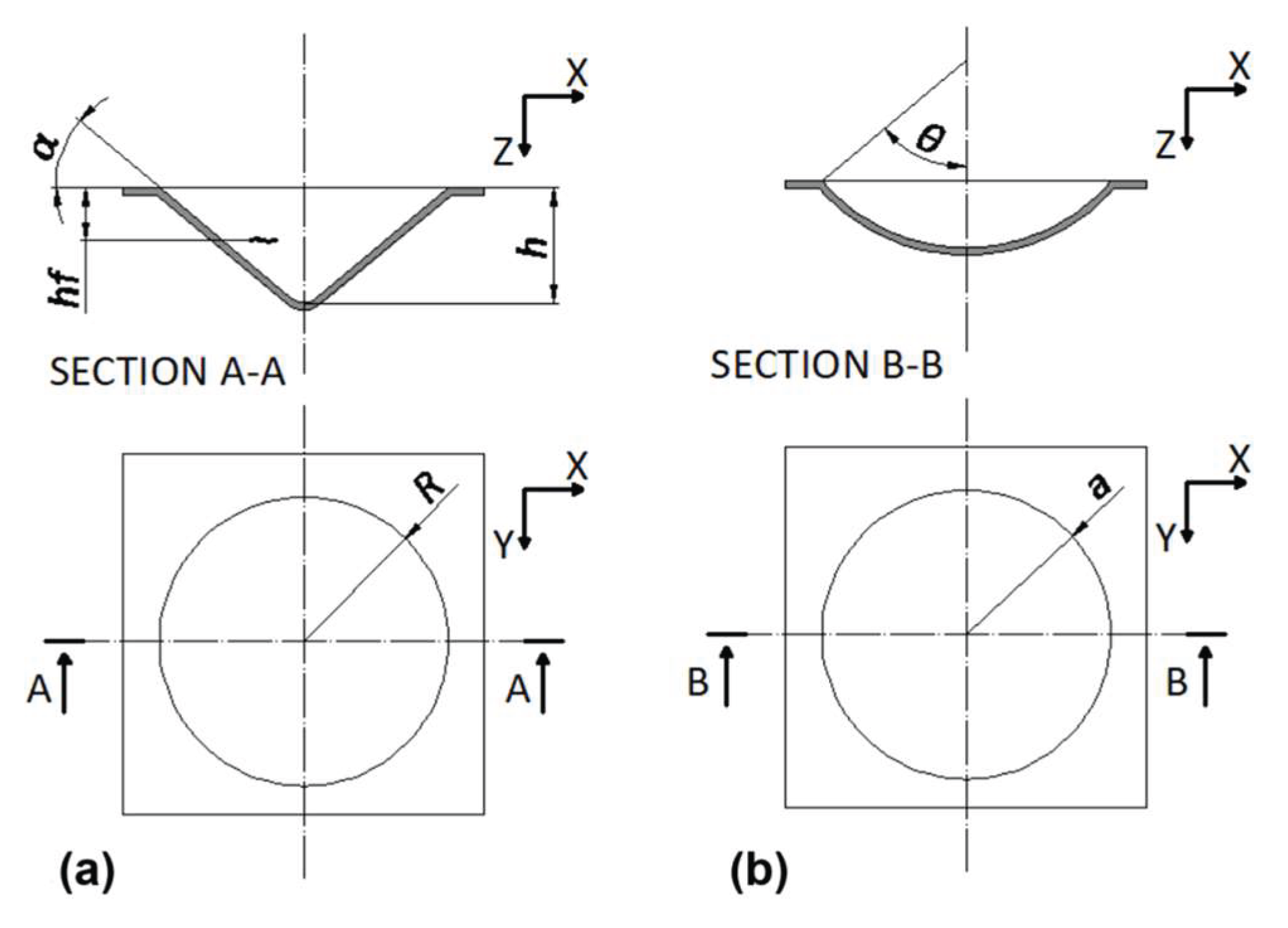

Cones and spherical caps were manufactured using the simplest variant of the process, known as single-point incremental forming (SPIF). A CAD representation of the components is shown in

Figure 2. In

Figure 2a,

R,

h and

α represent the base radius, height, and wall angle of the cones, respectively, while

hf is the height at the potential point of failure. Additionally,

a and

θ in

Figure 2b denote the base radius and polar angle of the spherical caps.

The forming tests (see an example for the manufacture of an F_PP cone in

Figure 3) were conducted using a C.B. Ferrari high-speed four-axis vertical machining center. This machine drove the forming tool, a non-rotating stainless-steel stylus with a hemispherical head 10 mm in diameter, to progressively deform the composite laminates. The laminates were secured using a clamping frame with a square working area of 100 × 100 mm

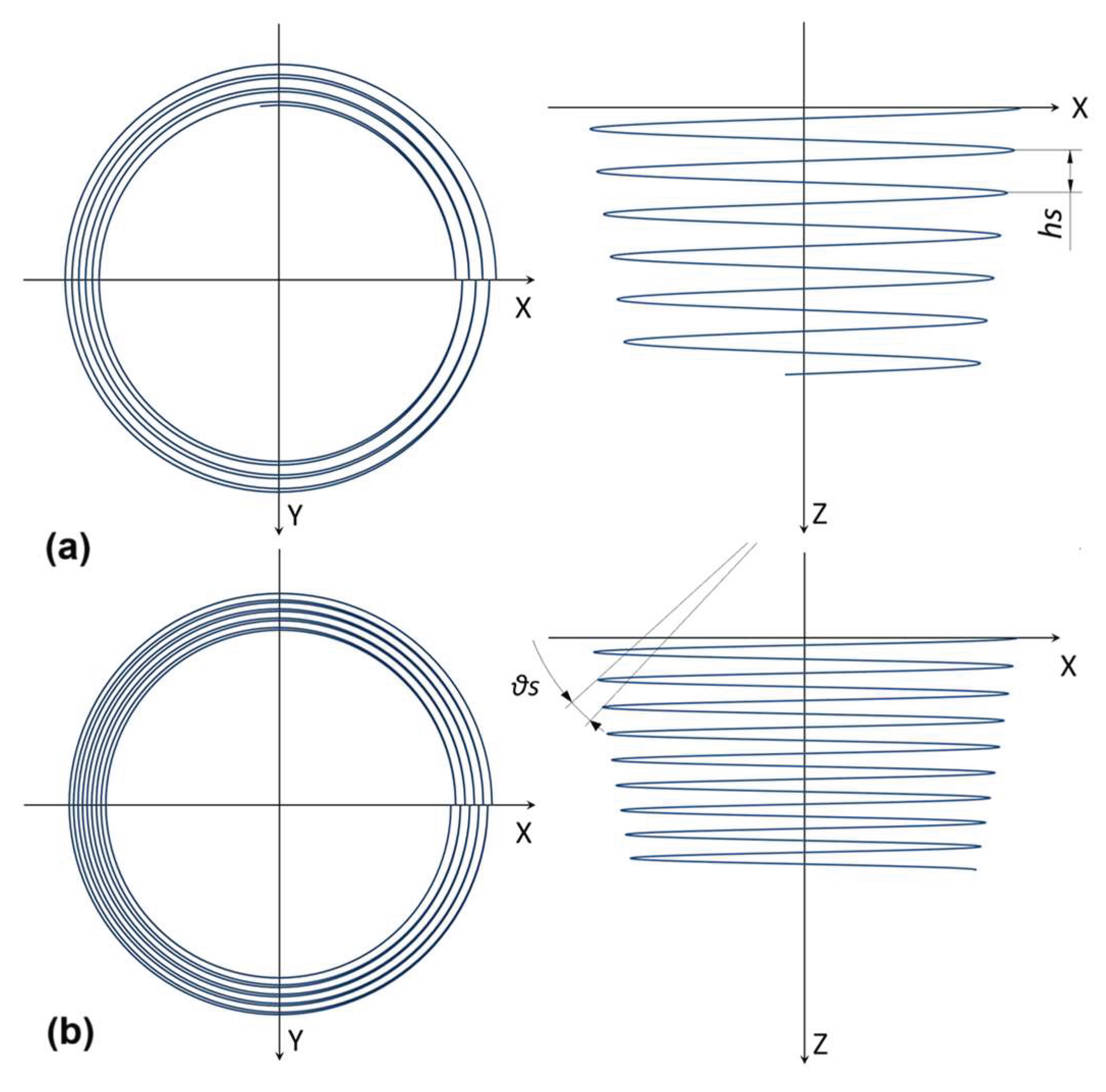

2. The forming tool followed alternating helical toolpaths (the turns alternated in anticlockwise and clockwise directions; see their not-to-scale representation in

Figure 4), with constant vertical and angular steps down (

hs and

θs, i.e. the vertical and angular distance covered after one complete turn of the toolpaths, respectively) and at a nominal speed

v = 1000 mm/min.

Figure 2.

CAD representation of the components manufactured by SPIF process: (a) cones and (b) spherical caps.

Figure 2.

CAD representation of the components manufactured by SPIF process: (a) cones and (b) spherical caps.

Figure 3.

Execution of an FF_P cone SPIF test.

Figure 3.

Execution of an FF_P cone SPIF test.

Figure 4.

Toolpaths for the SPIF process: (a) cones and (b) spherical caps.

Figure 4.

Toolpaths for the SPIF process: (a) cones and (b) spherical caps.

Despite recent innovations in ISF of biocomposites that provided for localized heating [

40], the SPIF process was conducted at room temperature to preserve its flexibility and ease of use. To reduce the probability of encountering failures and defects, the tests were carried out under lubricated conditions using the Boelube 70104 (100A) synthetic lubricant, developed by Boeing and supplied by Orelube.

The experimental campaign aimed to evaluate various types of failures and defects during the SPIF tests to collect information on the formability limits of SPIF applied to these composite laminates. Additionally, it provided information on the forming forces required for the manufacturing process. Three forces (

FX,

FY, and

FZ; the modules of the force acting in the sheet plane,

FXY, and of the total forming force,

FTOT, which is the resultant of the forces acting between the forming tool and the laminate, were obtained as a combination of the three components) and one moment (

MZ) were acquired at a frequency of 50 Hz using the K-MCS10 multicomponent sensor (see

Figure 3), equipped with the QuantumX MX840B data acquisition system and the Catman Easy AP software. These forces were also used to evaluate the process power profile and energy consumption. This choice of using the forces, instead of evaluating the energy requirement, is justified by the fact that the actual energy required for the process is only a small proportion of the total energy consumed, as most of the energy requirements are due to additional functions of the equipment [

41].

3. Results and Discussion

This section reports the results and discussion of the experimental campaign, subdivided into two parts. The first part describes the feasibility of the SPIF process, and the formability limits reached for the two laminate types, while the second part discusses the forming forces, power, and energy required for the process.

3.1. Feasibility of the SPIF Process and Formability Limits

The first part of the experimental campaign involved the manufacture of cones, represented in

Figure 2a, with

R = 40 mm and three different

α values (30°, 40°, and 50°); for the toolpath (see

Figure 4a),

hs = 1 mm. All the components showed no twisting, due to the alternating nature of the toolpath. This significantly reduces the probability of twisting because the twist produced after a turn is almost completely recovered in the next [

42], as observed in the ISF of metal [

6] and polycarbonate components [

43]. Additionally, the lack of instabilities and wrinkling indicates non-severe working conditions [

44].

Regarding formability limits, the cones were sound and had good surface quality for both fibers at

α = 30° and

α = 40°, reaching their maximum allowable heights

h (approximately 22 mm and 32 mm, respectively).

Figure 5 shows an H_PP cone with

α = 40°.

Failures occurred at

α = 50° for both fiber types. For H_PPs (see

Figure 6), the failure was perpendicular to the fabric and occurred at

hf ≈ 20 mm. For F_PPs (see

Figure 7), the failure occurred at higher heights (

hf > 30 mm) and primarily affected the matrix. These differences could be due to the mechanical behavior of the laminates, influenced by the efficiency of the fiber-matrix adhesion, in turn depending on the molding process.

Despite the process not allowing for very high wall angles, it can be used for applications such as shaping stiffening ribs for panels in the automotive, aviation, and naval fields [

45]. In this context, spherical caps were manufactured (see

Figure 2b). They had

a = 40 mm and two different

θ values (40° and 50°); for the toolpath,

θs = 1° (see

Figure 4b).

The caps were sound and had good surface quality for both fibers and at both

θ values.

Figure 8 shows an F_PP cap with

θ = 50°.

Figure 6.

H_PP cone (α = 50°).

Figure 6.

H_PP cone (α = 50°).

Figure 7.

F_PP cone (α = 50°).

Figure 7.

F_PP cone (α = 50°).

Figure 8.

F_PP cap (θ = 50°).

Figure 8.

F_PP cap (θ = 50°).

3.2. Considerations on Forces, Power, and Energy

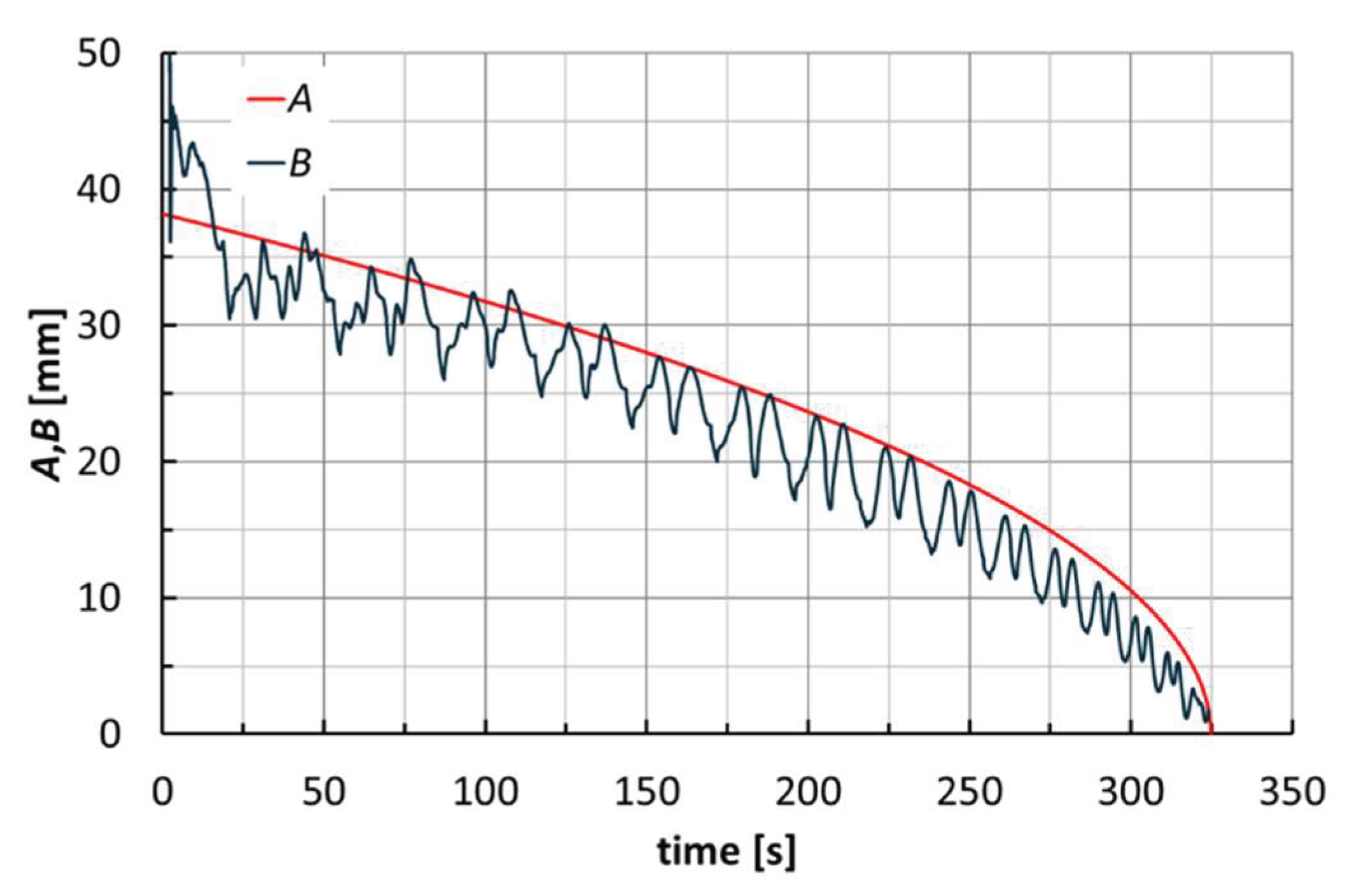

A first observation can be made by analyzing the curves in

Figure 9 (related to an F_PP cone with

α = 40°), where

A represents the current radius of the spiral toolpath and

B the absolute value of the ratio between

MZ and

FXY. Excluding the first turns of the toolpath (which can be considered a transition phase of the process), curve

A can be seen as the envelope of curve

B. This confirms the incremental nature of the ISF process because the

B ratio represents the lever arm of

FXY that generates

MZ.

The trends of forces and moments reflect the alternating nature of the toolpaths (this also justifies the fluctuations of

B in

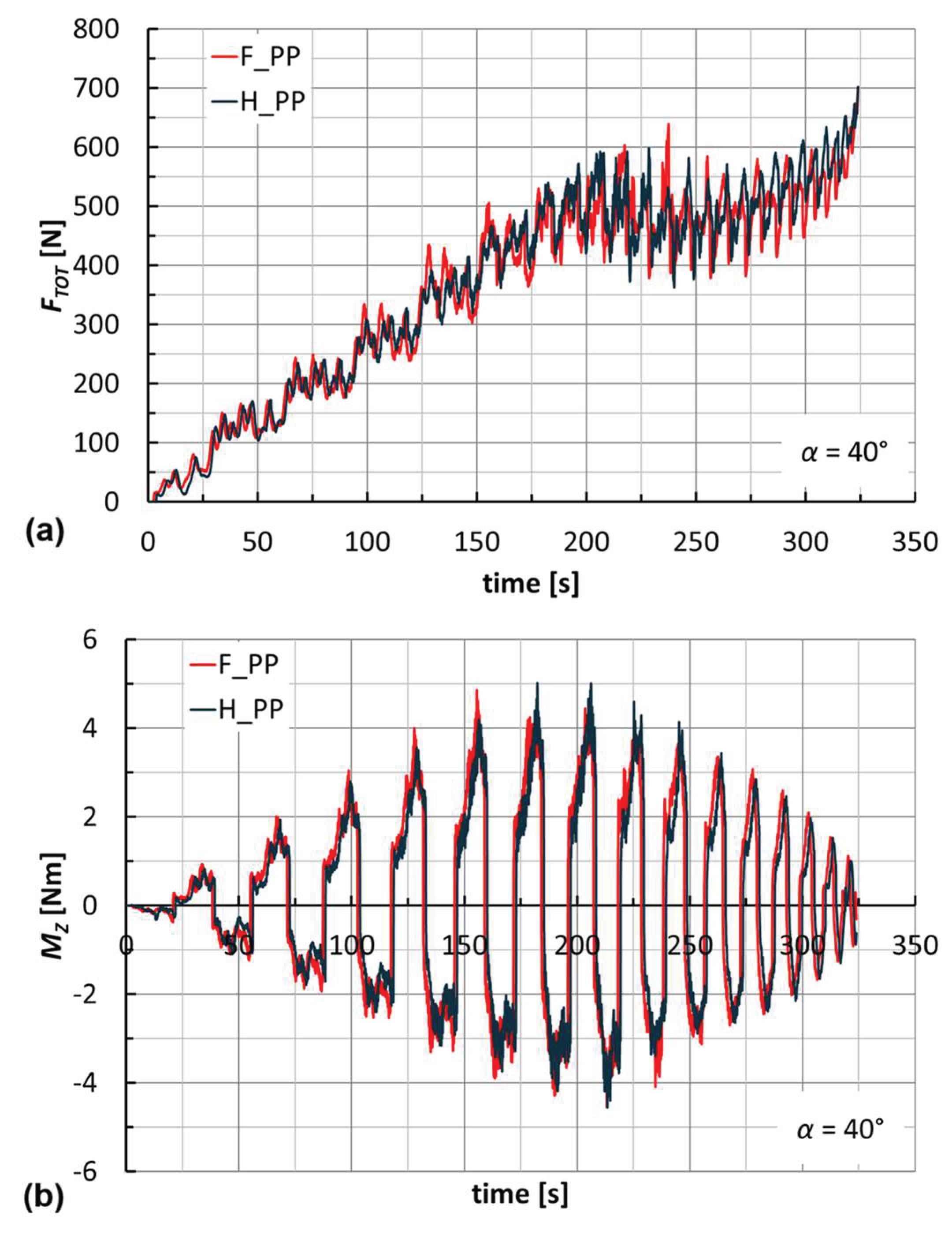

Figure 9). They are very similar for the two laminates; see, for example,

Figure 10 for the manufacture of cones at

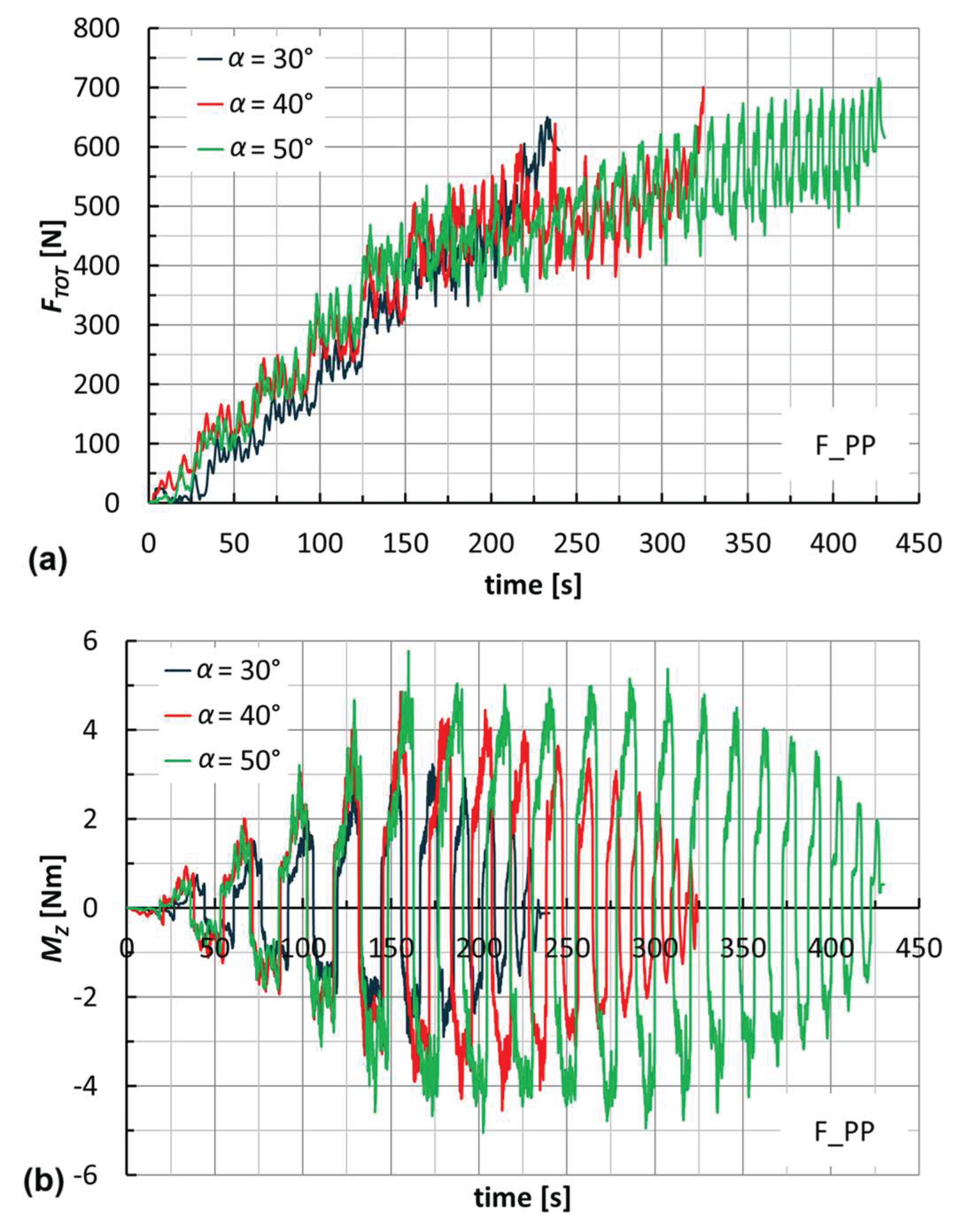

α = 40°. Their maximum values slightly increase with

α (see

Figure 11 for F_PP laminates) and, as anticipated earlier, translate into non-severe working conditions that suggest low energy impact for this manufacturing process. The maximum values of

FTOT and the module of

MZ, both reached for F_PP at

α = 50°, were equal to 716 N and 5.8 Nm, respectively.

The total power,

PTOT, was obtained by considering separately the contributions of

FXY and

FZ (

PXY and

PZ, respectively), according to the following equations:

where

vZ,m is the mean value of the speed along the Z axis, calculated as the ratio between the total vertical displacement and the time to describe it.

For the process under examination, the speeds in the XY plane and along the Z axis (vXY and vZ, respectively) are not constant because they depend on the actual slope of the spiral toolpath. However, two simplifications were applied in equations 2 and 3, to use two constant values of speed. Specifically, v was used in place of vXY in Eq. 2 because the low value of hs compared to the spiral radii translates into a low slope (a large discrepancy between v and vXY occurs only when the last turn of the toolpath reaches the vertex of the cone). Similarly, it is possible to replace vZ with vZ,m in Eq. 3, especially considering that these are very low speeds and may not significantly contribute to the total power and energy.

Figure 10.

Trends of (a) FTOT and (b) MZ by varying the laminate (α = 40°).

Figure 10.

Trends of (a) FTOT and (b) MZ by varying the laminate (α = 40°).

Figure 11.

Trends of (a) FTOT and (b) MZ by varying the wall angle (F_PP).

Figure 11.

Trends of (a) FTOT and (b) MZ by varying the wall angle (F_PP).

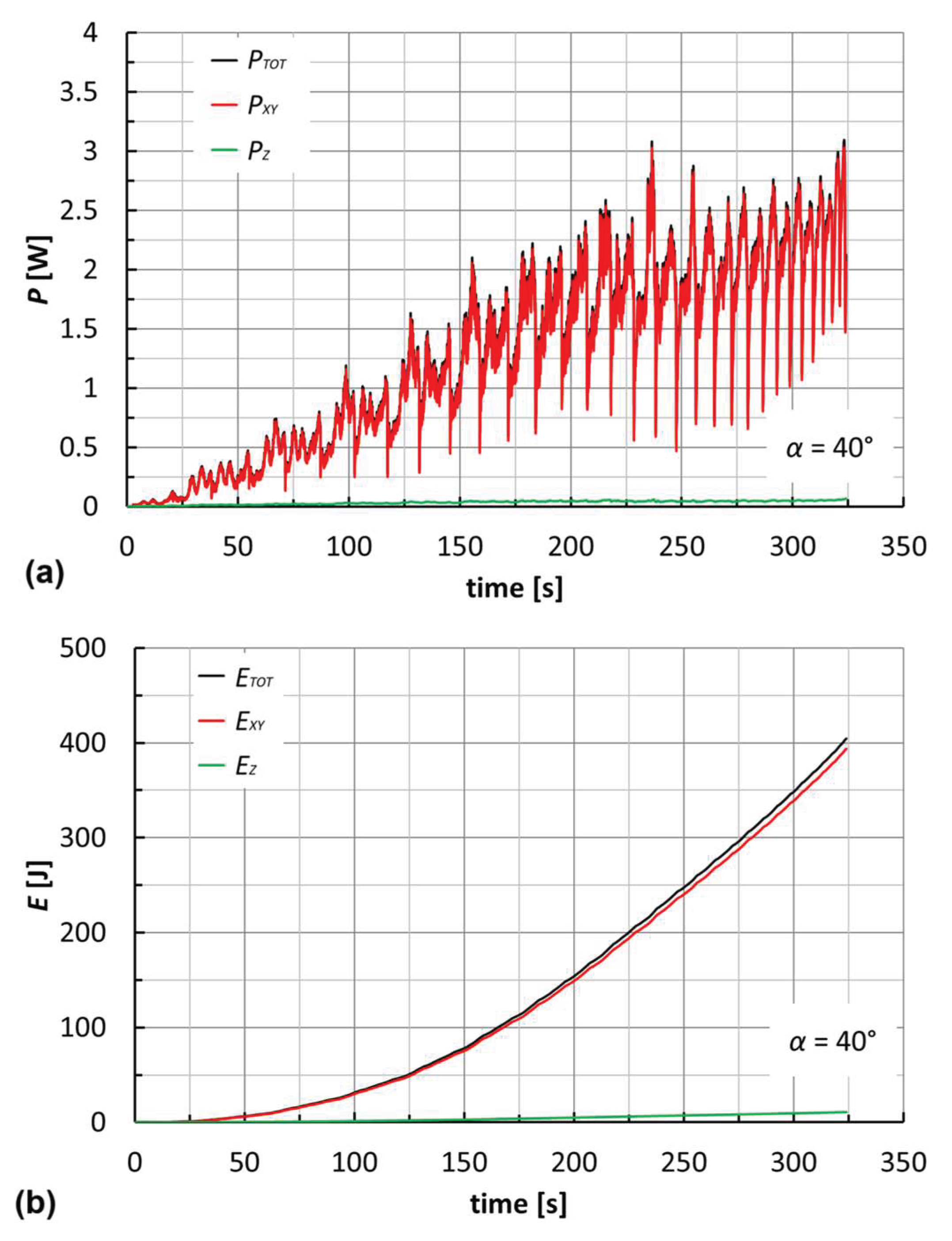

Figure 12a reports the power curves for an F_PP laminate at

α = 40°. It is evident that the contribution of

PZ is nearly irrelevant, in line with the above considerations on Eq. 3. Therefore, it is possible to make a good estimate of the total power through an assigned constant process parameter (

v) and the monitoring of

FXY. Alternatively, and according to the suggestions from

Figure 9, it would be necessary to know the angular speed law (not constant) and to monitor

MZ. Quantitatively, the powers reached are very low for all cases (under 5 W), due to the low

FXY and

v values.

The energies (

ETOT,

EXY and

EZ; see

Figure 12b for an F_PP laminate at

α = 40°) were determined as the time-integral of the power curves. The Riemann integral was used, with a regular partition of the time equal to the period of acquisition of the forces (0.02 s).

Just as with the powers, ETOT is almost equal to EXY. Moreover, the maximum values for the two geometries are reached for F_PP laminates at α = θ = 50° (about 600 and 450 J, respectively).

Figure 12.

Trends of (a) power and (b) energy for an F_PP laminate (α = 40°).

Figure 12.

Trends of (a) power and (b) energy for an F_PP laminate (α = 40°).

4. Conclusions

This experimental research outlines the feasibility and energy implications of the single-point incremental forming process applied to laminates of flax and hemp fiber-reinforced polypropylene composites.

The first part of the work focuses on the manufacture of cones with different wall angles (from 30° to 50°) and demonstrates that the process, carried out at room temperature and without dedicated dies, ensures such formability limits that it allows for the manufacture of stiffening ribs like spherical caps.

The analysis of forces and moments highlights that the process requires low load levels (under the severest working conditions, less than 720 N and 6 Nm). Additionally, the force-based evaluation of powers and energies reveals a very low energy impact of the process under examination, which is of great interest from a sustainable manufacturing perspective.

Future research could extend the investigation of the process parameters that influence the incremental formability of natural fiber-reinforced composites, as well as compare this process with other forming processes in terms of energy efficiency. Additionally, it could include numerical simulations of the process, mechanical characterization and geometrical accuracy of the components, and feasibility of remolding panels after incremental forming.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F. and M.D.; methodology, A.F. and M.D; investigation, A.F., M.D., D.D.F. and G.I.; data curation, A.F. and D.D.F.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F.; writing—review and editing, A.F. and G.I.; supervision, A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ISF |

Incremental sheet forming |

| CNC |

Computerized numerical control |

| PP |

Polypropylene |

| H_PP |

Hemp fiber-reinforced polypropylene composites |

| F_PP |

Flax fiber-reinforced polypropylene composites |

| t |

Laminate thickness |

| SPIF |

Single-point incremental forming |

| CAD |

Computer aided design |

| R |

Base radius of the cones |

| h |

Height of the cones |

| α |

Wall angle of the cones |

| hf |

Height at the potential point of failure of the cones |

| a |

Base radius of the spherical caps |

| θ |

Polar angle of the spherical caps |

| hs |

Vertical distance covered after one complete turn of the toolpaths |

| θs |

Angular distance covered after one complete turn of the toolpaths |

| v |

Nominal toolpath speed |

| FX |

Module of the forming force along the X axis |

| FY |

Module of the forming force along the Y axis |

| FZ |

Module of the forming force along the Z axis |

| FXY |

Module of the forming force acting in the XY plane |

| FTOT |

Module of the total forming force |

| MZ |

Module of the moment around the Z axis |

| A |

Current radius of the spiral toolpath |

| B |

Absolute value of the ratio between MZ and FXY

|

| PTOT |

Total power |

| PXY |

Power associated to FXY

|

| PZ |

Power associated to FZ

|

| vZ,m |

Mean value of the speed along the Z axis |

| vXY |

Speed in the XY plane |

| vZ |

Speed along the Z axis |

| ETOT |

Total energy |

| EXY |

Energy associated to FXY

|

| EZ |

Energy associated to FZ

|

References

- Jiang, J. A Survey of Machine Learning in Additive Manufacturing Technologies. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2023, 36, 1258–1280. [CrossRef]

- Formisano, A.; Boccarusso, L.; Capece Minutolo, F.; Carrino, L.; Durante, M.; Langella, A. Negative and Positive Incremental Forming: Comparison by Geometrical, Experimental, and FEM Considerations. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2017, 32, 530–536. [CrossRef]

- Formisano, A.; Astarita, A.; Boccarusso, L.; Garlasché, M.; Durante, M. Formability and Surface Quality of Non-Conventional Material Sheets for the Manufacture of Highly Customized Components. Int. J. Mater. Form. 2022, 15, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, G.; Khan, H.R.; Gao, L.; Hayat, N. Guidelines for Tool-Size Selection for Single-Point Incremental Forming of an Aerospace Alloy. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2013, 28, 324–329. [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, G.; Nagarajan, D.; Ravisankar, B. The Incremental Sheet Forming of Light Alloys. In Analysis and Optimization of Sheet Metal Forming Processes; CRC Press, 2024; pp. 157–173 ISBN 9781040027318.

- Jeswiet, J.; Micari, F.; Hirt, G.; Bramley, A.; Duflou, J.; Allwood, J. Asymmetric Single Point Incremental Forming of Sheet Metal. CIRP Ann. 2005, 54, 88–114. [CrossRef]

- Trzepieciński, T.; Oleksik, V.; Pepelnjak, T.; Najm, S.M.; Paniti, I.; Maji, K. Emerging Trends in Single Point Incremental Sheet Forming of Lightweight Metals. Met. 2021, Vol. 11, Page 1188 2021, 11, 1188. [CrossRef]

- Mandaloi, G.; Nagargoje, A.; Gupta, A.K.; Banerjee, G.; Shahare, H.Y.; Tandon, P. A Comprehensive Review on Experimental Conditions, Strategies, Performance, and Applications of Incremental Forming for Deformation Machining. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2022, 144, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, M.K.; Singh, P.; Mishra, P.; Deb, R.K.; Mohammed, K.A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, G. A Brief Review on the Perspective of a Newer Incremental Sheet Forming Technique and Its Usefulness. Adv. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 10, 506–516. [CrossRef]

- Popp, G.P.; Racz, S.G.; Breaz, R.E.; Oleksik, V. Ștefan; Popp, M.O.; Morar, D.E.; Chicea, A.L.; Popp, I.O. State of the Art in Incremental Forming: Process Variants, Tooling, Industrial Applications for Complex Part Manufacturing and Sustainability of the Process. Materials (Basel). 2024, 17, 5811. [CrossRef]

- Emmens, W.C.; van den Boogaard, A.H. An Overview of Stabilizing Deformation Mechanisms in Incremental Sheet Forming. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 3688–3695. [CrossRef]

- Ai, S.; Long, H. A Review on Material Fracture Mechanism in Incremental Sheet Forming. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 104, 33–61. [CrossRef]

- Deokar, S.; Jain, P.K. Analyses of Stress and Forces in Single-Point Incremental Sheet Metal Forming. In Handbook of Flexible and Smart Sheet Forming Techniques: Industry 4.0 Approaches; wiley, 2023; pp. 117–127 ISBN 9781119986454.

- Mohan, S.R.; Dewang, Y.; Sharma, V. Tool Path Planning for Hole-Flanging Process Using Single Point Incremental Forming. MATEC Web Conf. 2024, 393, 01003. [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Ou, H.; Shi, S.Q.; Long, H.; Chen, J. Titanium Based Cranial Reconstruction Using Incremental Sheet Forming. Int. J. Mater. Form. 2016, 9, 361–370. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wen, T.; Qin, J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Z. sun Deformation Feature of Sheet Metals During Inclined Hole-Flanging by Two-Point Incremental Forming. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2020, 21, 169–176. [CrossRef]

- Makwana, R.; Modi, B.; Patel, K. Single-Stage Single Point Incremental Square Hole Flanging of AA5052 Material. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2023, 38, 680–691. [CrossRef]

- Liuru, Z.; Yinmei, Z.; Zhongmin, L. Study on Incremental Forming for the Fender of the Car. Mater. Res. Innov. 2015, 19, S6105–S6107. [CrossRef]

- Franzen, V.; Kwiatkowski, L.; Martins, P.A.F.; Tekkaya, A.E. Single Point Incremental Forming of PVC. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 462–469. [CrossRef]

- Marques, T.A.; Silva, M.B.; Martins, P.A.F. On the Potential of Single Point Incremental Forming of Sheet Polymer Parts. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2012, 60, 75–86. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Ou, H.; Popov, A. Incremental Sheet Forming of Thermoplastics: A Review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 111, 565–587. [CrossRef]

- Rosa-Sainz, A.; Centeno, G.; Silva, M.B.; Vallellano, C. Experimental Failure Analysis in Polycarbonate Sheet Deformed by Spif. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 64, 1153–1168. [CrossRef]

- Das, A. A Comprehensive Review on Incremental Sheet Forming and Its Associated Aspects. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2024, 17, 159–178. [CrossRef]

- Durante, M.; Formisano, A.; Boccarusso, L.; Langella, A. Influence of Cold-Rolling on Incremental Sheet Forming of Polycarbonate. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2020, 35, 328–336. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.P.; Allwood, J.M.; Landert, M. Incremental Forming of Sandwich Panels. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 204, 290–303. [CrossRef]

- Fiorotto, M.; Sorgente, M.; Lucchetta, G. Preliminary Studies on Single Point Incremental Forming for Composite Materials. Int. J. Mater. Form. 2010, 3, 951–954. [CrossRef]

- Emami, R.; Mirnia, M.J.; Elyasi, M.; Zolfaghari, A. An Experimental Investigation into Single Point Incremental Forming of Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polyamide Sheet with Different Fiber Orientations and Volume Fractions at Elevated Temperatures. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2023, 36, 1893–1917. [CrossRef]

- Ikari, T.; Tanaka, H. Feasibility Study of Single-Point Incremental Forming for Discontinuous-Fiber CFRP Using Oil-Bath Heating. Int. J. Autom. Technol. 2024, 18, 433–443. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, G.; Hassan, M.; Wei, H.; Buhl, J.; Xiao, M.; Iqbal, A.; Qayyum, H.; Riaz, A.A.; Muhammad, R.; Ostrikov, K. (Ken) Advances on Incremental Forming of Composite Materials. Alexandria Eng. J. 2023, 79, 308–336. [CrossRef]

- Taha, I.; El-Sabbagh, A.; Ziegmann, G. Modelling of Strength and Stiffness Behaviour of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polypropylene Composites. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2008, 16, 295–302. [CrossRef]

- Alhijazi, M.; Safaei, B.; Zeeshan, Q.; Arman, S.; Asmael, M. Prediction of Elastic Properties of Thermoplastic Composites with Natural Fibers. J. Text. Inst. 2023, 114, 1488–1496. [CrossRef]

- Luthra, P.; Vimal, K.K.; Goel, V.; Singh, R.; Kapur, G.S. Biodegradation Studies of Polypropylene/Natural Fiber Composites. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Pil, L.; Bensadoun, F.; Pariset, J.; Verpoest, I. Why Are Designers Fascinated by Flax and Hemp Fibre Composites? Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 83, 193–205. [CrossRef]

- Frącz, W.; Janowski, G.; Bąk, Ł. Influence of the Alkali Treatment of Flax and Hemp Fibers on the Properties of PHBV Based Biocomposites. Polymers (Basel). 2021, 13, 1965. [CrossRef]

- Zampori, L.; Dotelli, G.; Vernelli, V. Life Cycle Assessment of Hemp Cultivation and Use of Hemp-Based Thermal Insulator Materials in Buildings. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7413–7420. [CrossRef]

- Formisano, A.; Papa, I.; Lopresto, V.; Langella, A. Influence of the Manufacturing Technology on Impact and Flexural Properties of GF/PP Commingled Twill Fabric Laminates. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2019, 274. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, K.A. Spring Back Analysis in Incremental Forming of Polypropylene Sheet: An Experimental Study. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2018, 32, 4859–4869. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, G. Development of the Temperature-Dependent Constitutive Model of Glass Fiber Reinforced Polypropylene Composites. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2023, 38, 295–305. [CrossRef]

- Arinze, R.U.; Oramah, E.; Chukwuma, E.C.; Okoye, N.H.; Eboatu, A.N.; Udeozo, P.I.; Chris-Okafor, P.U.; Ekwunife, M.C. Reinforcement of Polypropylene with Natural Fibers: Mitigation of Environmental Pollution. Environ. Challenges 2023, 11, 100688. [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.; Ortega, R.; Acosta, P.; Calderón, E. Hot Incremental Forming of Biocomposites Developed from Linen Fibres and a Thermoplastic Matrix. Stroj. Vestnik/Journal Mech. Eng. 2021, 67, 123–132. [CrossRef]

- Bagudanch, I.; Garcia-Romeu, M.L.; Sabater, M. Incremental Forming of Polymers: Process Parameters Selection from the Perspective of Electric Energy Consumption and Cost. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1013–1024. [CrossRef]

- Formisano, A.; Boccarusso, L.; De Fazio, D.; Durante, M. Effects of Toolpath on Defect Phenomena in the Incremental Forming of Thin Polycarbonate Sheets. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 133, 4957–4966. [CrossRef]

- Durante, M.; Formisano, A.; Lambiase, F. Incremental Forming of Polycarbonate Sheets. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 253, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Durante, M.; Formisano, A.; Lambiase, F. Formability of Polycarbonate Sheets in Single-Point Incremental Forming. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 102, 2049–2062. [CrossRef]

- Hariprasad, K.; Ravichandran, K.; Jayaseelan, V.; Muthuramalingam, T. Acoustic and Mechanical Characterisation of Polypropylene Composites Reinforced by Natural Fibres for Automotive Applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 14029–14035. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).