Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

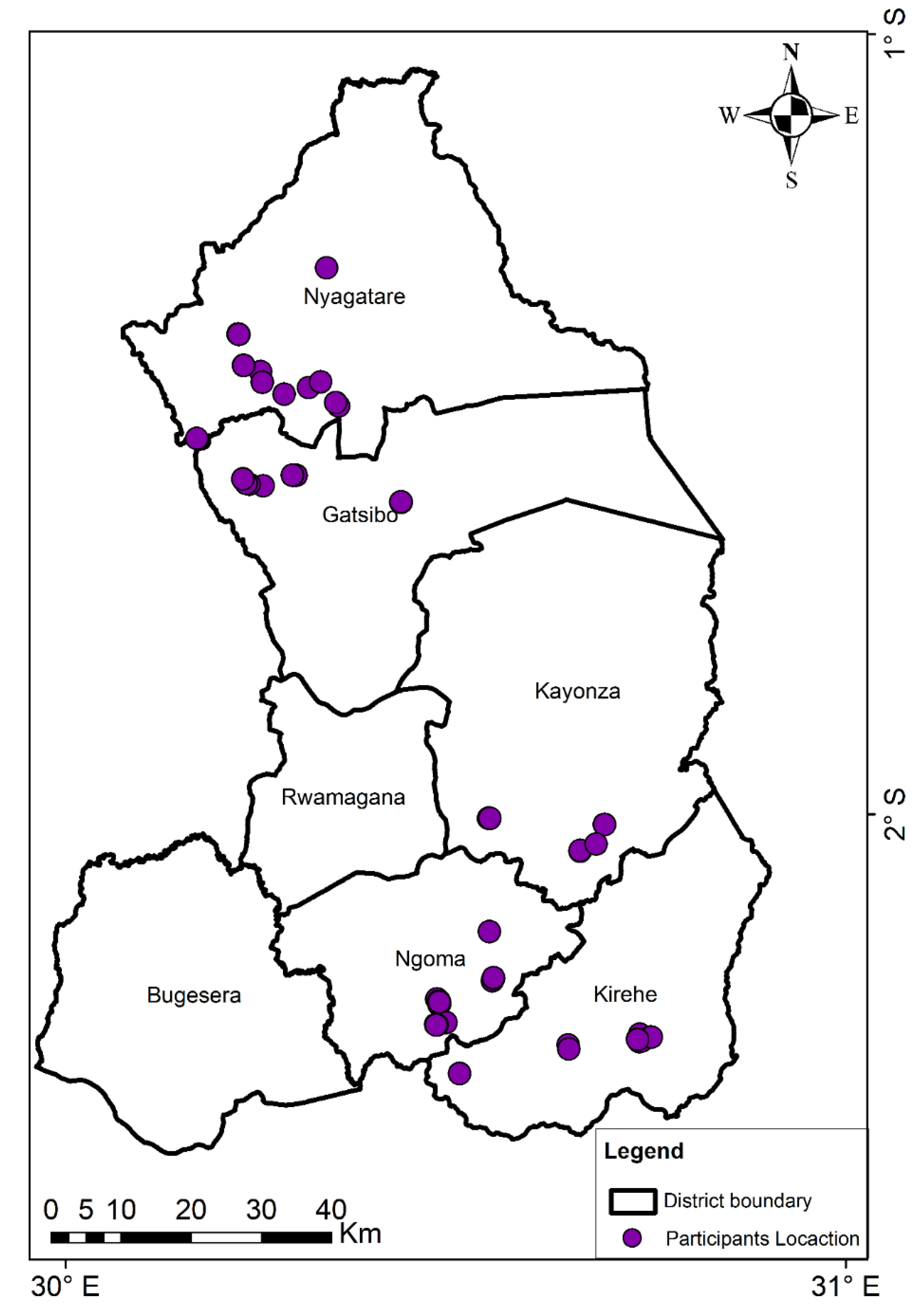

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sample (s)

2.3. Data Type and Data Collection Approach

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Climate Data Analysis

2.4.2. Farmers’ Field Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Changes in Temperature and Rainfall Events in Eastern Province

3.2. Socioeconomic Characteristics of Respondent Farmers

3.3. Farmers’ Knowledge of Weather and Climate Change

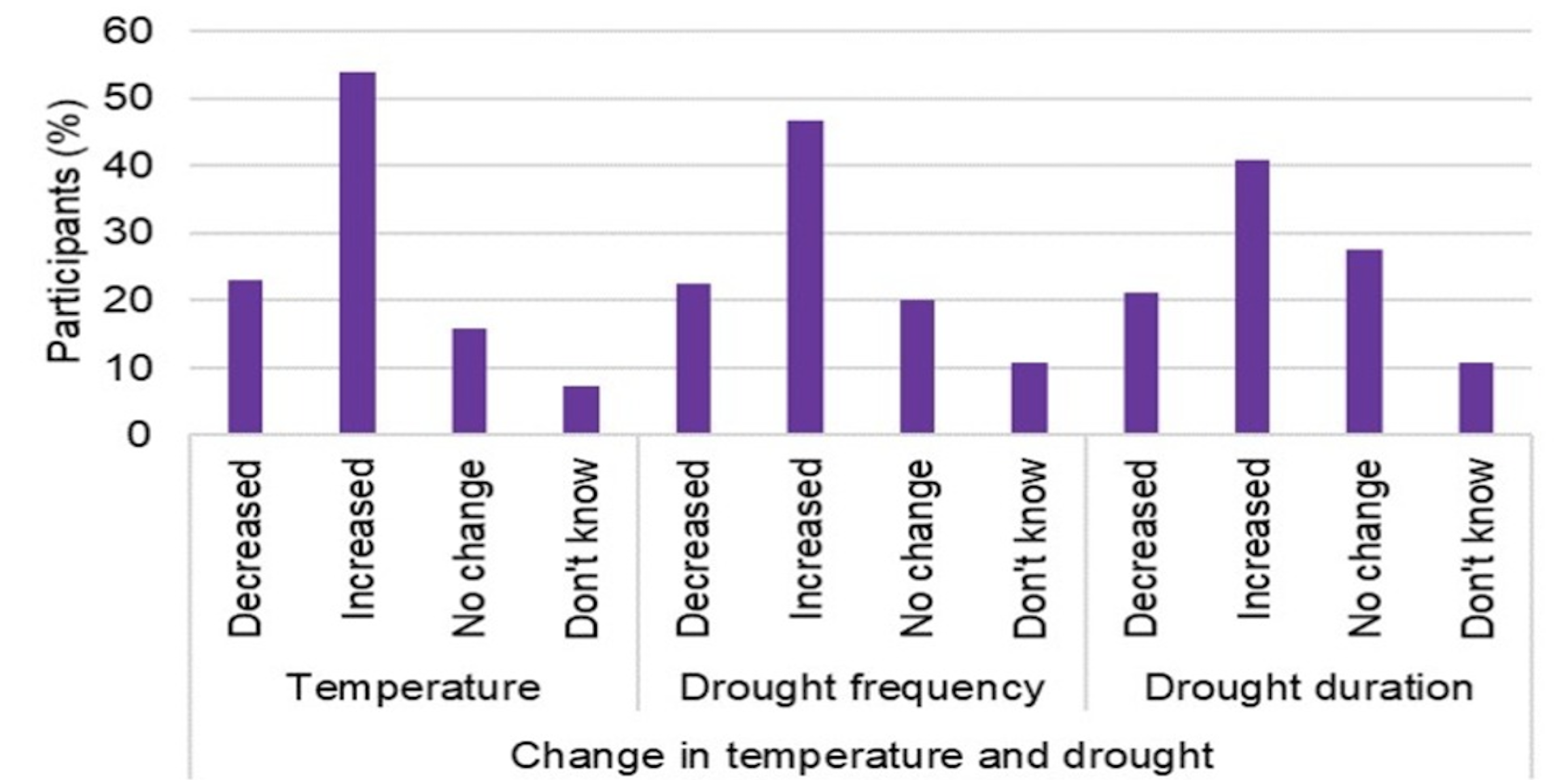

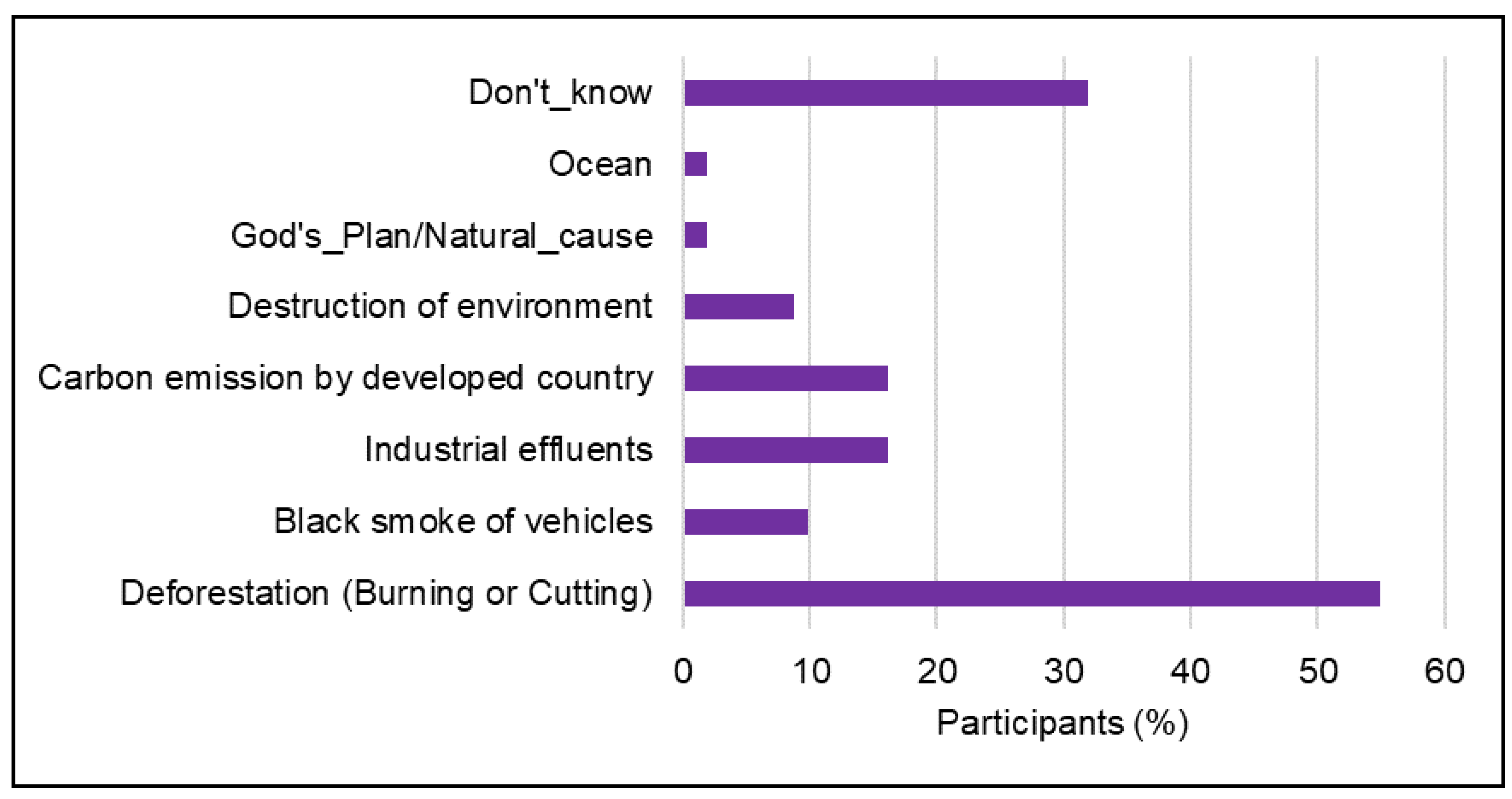

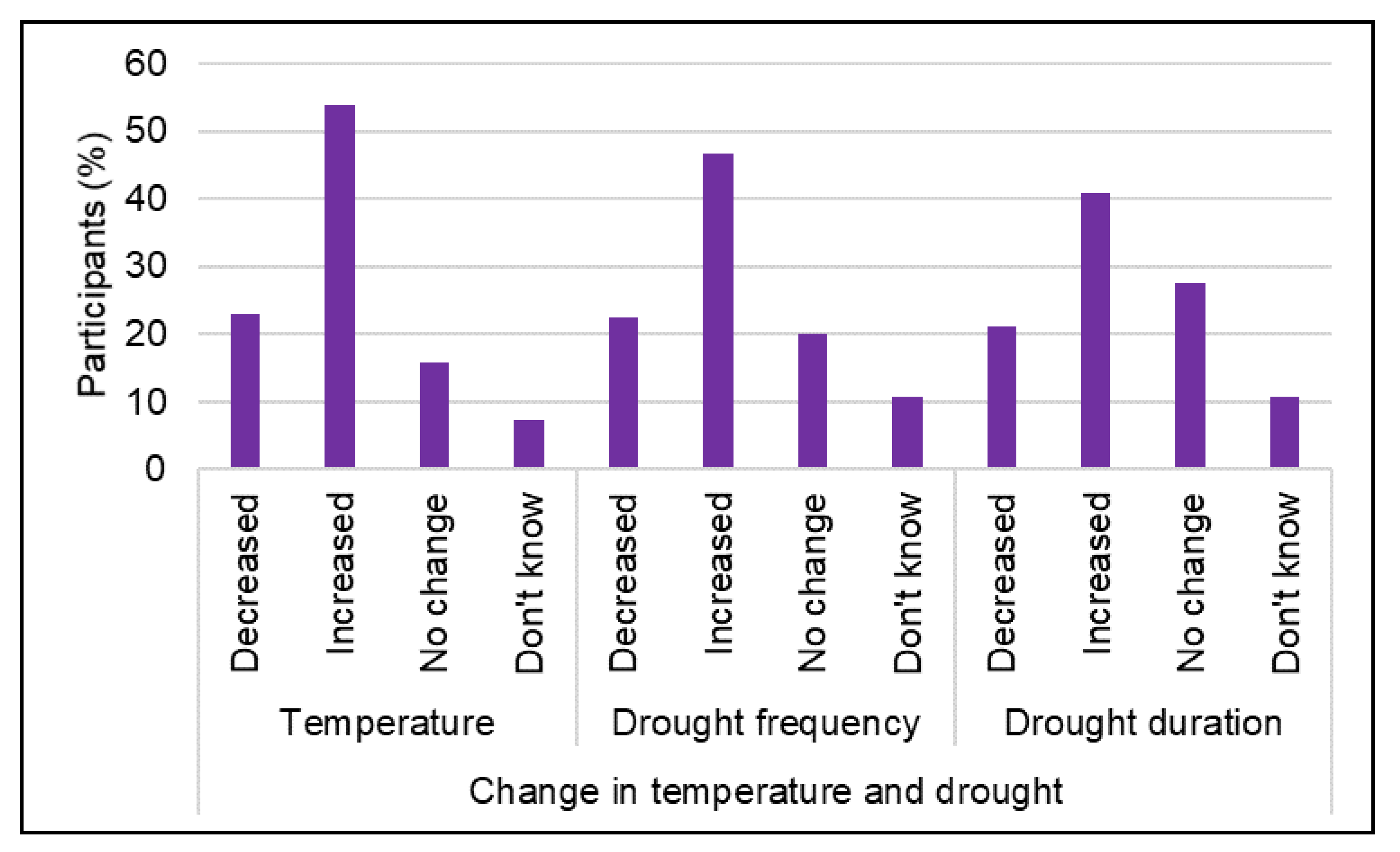

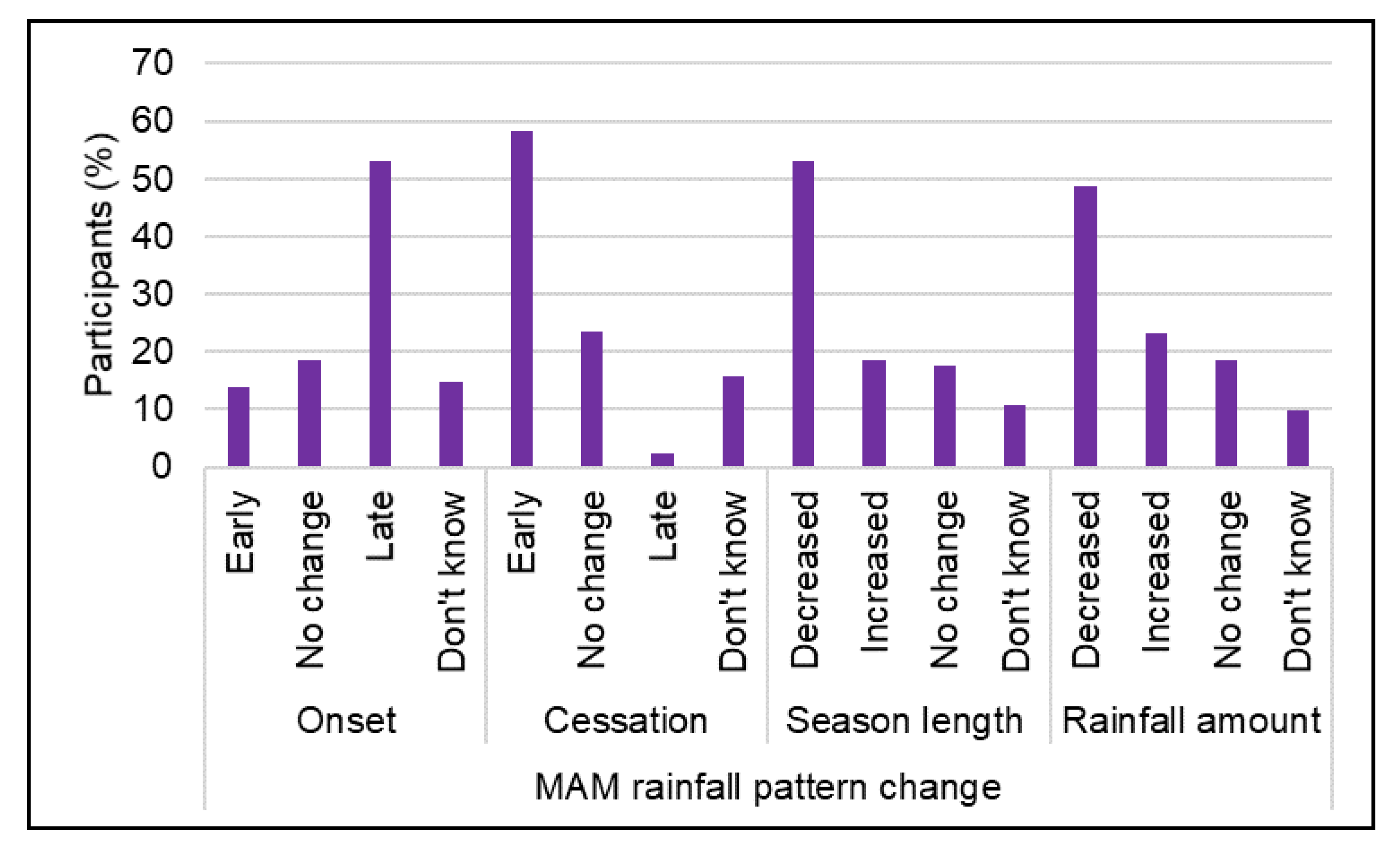

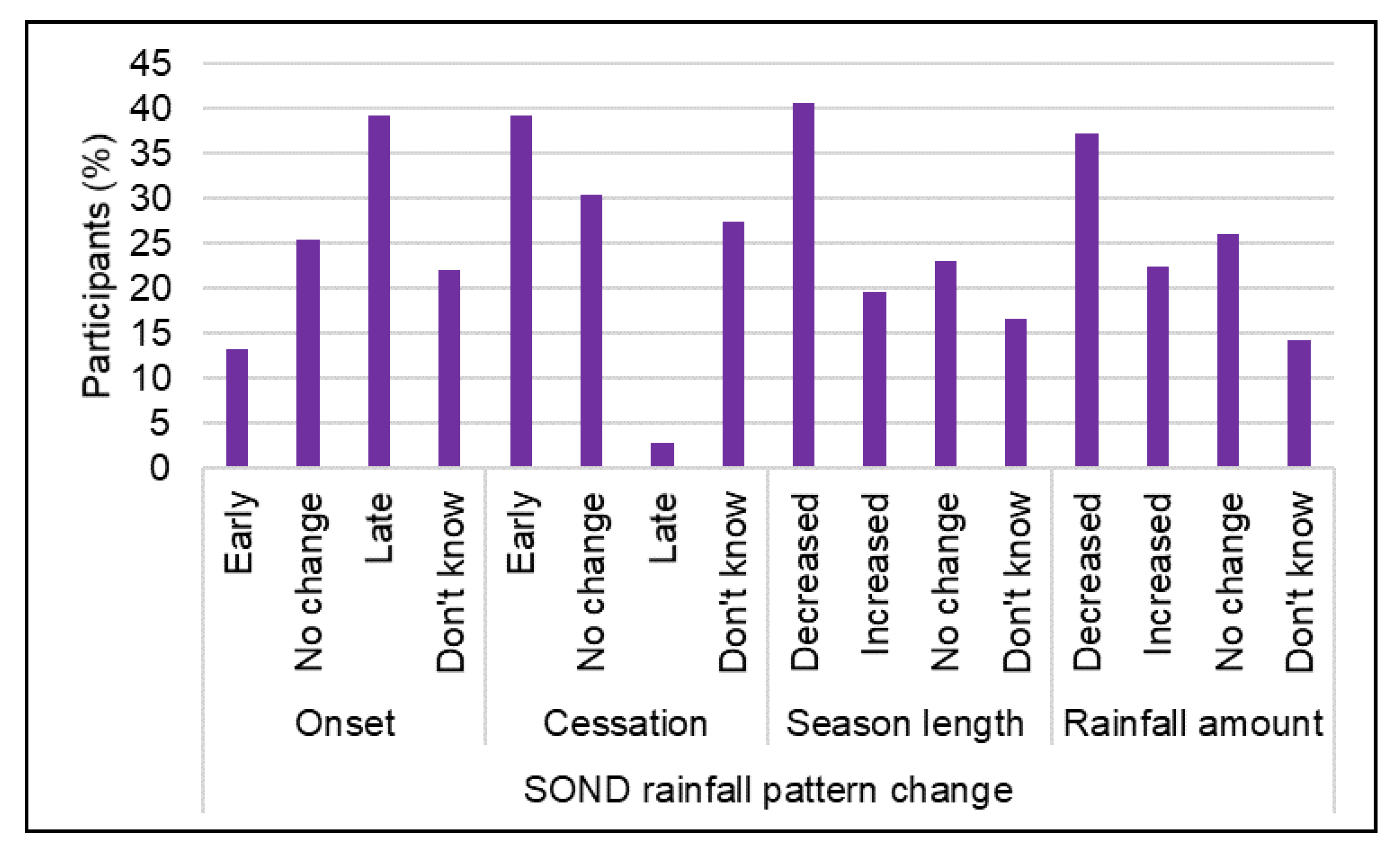

3.4. Respondent Farmers’ Perceptions of Climate Change

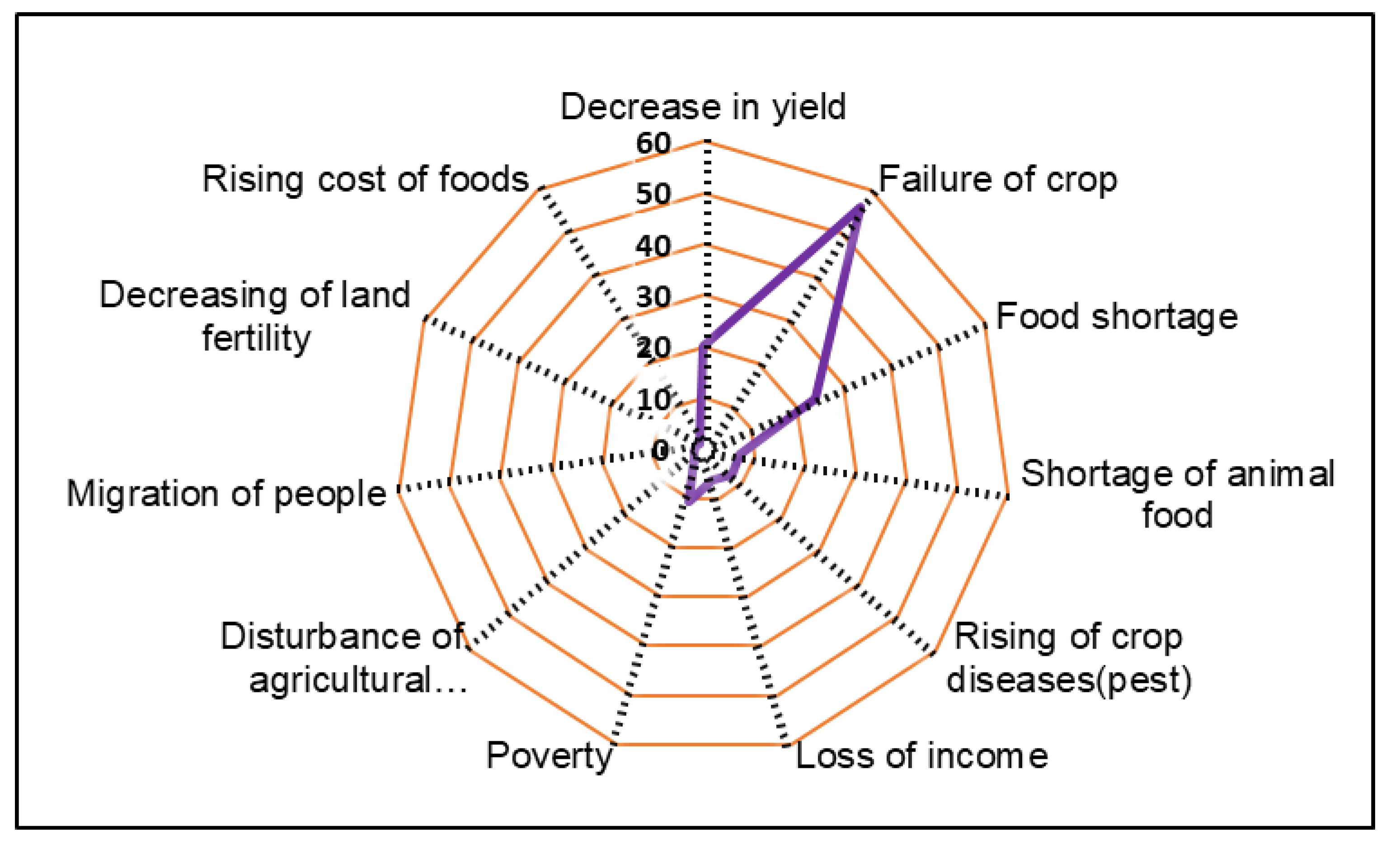

3.5. Respondent Farmers’ Perceptions of the Impacts of Climate Change

3.6. Climate Change Adaptation Strategies

3.7. Barrier to the Effective Adaptation of Climate Change

3.8. Socioeconomic Factors Influencing Farmers’ Choice of Adaptation Strategies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Climate research highlights significant shifts in temperature and rainfall patterns across the Eastern Province. While many farmers accurately recognize these changes in alignment with scientific findings, a considerable portion remains unaware or misinformed. This lack of awareness can impede the successful adoption of adaptation strategies, as understanding the nature of climate change and its implications is critical for fostering resilience. To address this challenge, it is essential for stakeholders, including government authorities, farmers, and community organizations, to take concerted action to mitigate the impacts of climate change in Eastern Rwanda. Priority should be given to capacity-building programs that educate farmers on the observed climatic shifts, their consequences, and the importance of adopting effective adaptation, mitigation, and prevention strategies. Enhancing farmers’ knowledge and awareness will contribute to building resilience and promoting sustainable agricultural practices in the region.

- We recommend that stakeholders establish a participatory framework that actively involves farmers in decision-making processes. This study reveals that farmers not only recognize climate change but also possess a deep understanding of their local climate conditions, which is vital for strengthening their resilience. Their localized knowledge is an invaluable resource that must be integrated into adaptation planning. Excluding farmers from these discussions could lead to the development of strategies that fail to address their most critical needs, thereby undermining the effectiveness and sustainability of adaptation efforts.

- The study highlights that farmers encounter numerous challenges, particularly those linked to financial constraints. To address this, stakeholders must strengthen their collaboration with farmers to gain a deeper understanding of these difficulties. This approach will enable the development of support programs and solutions that are both cost-effective and aligned with farmers’ financial realities. Efforts to improve the financial capacity of farmers are especially crucial for fostering resilience and sustainable agricultural practices in Eastern Rwanda.

- Since adaptation methods like agroforestry have been widely embraced by farmers, it is vital for the government and other stakeholders to prioritize selecting tree species that are best suited to the soil and climatic conditions of Eastern Rwanda. Adopting this targeted approach can maximize the benefits of agroforestry, strengthening farmers’ resilience by improving health, nutrition, and financial stability, all of which are influenced by the choice of tree species planted.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Climate Change 2013 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. Mind’je et al., “Flood susceptibility modeling and hazard perception in Rwanda,” Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct., vol. 38, p. 101211, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Saleem et al., “Preparation of Marketable Functional Food to Control Hypertension using Basil (ocimum basillium) and Peppermint (mentha piperita).,” Int. J. Innov. Sci. Technol., vol. 01, no. 01, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (Ipcc), Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed. Cambridge University Press, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. T. Pecl et al., “Biodiversity redistribution under climate change: Impacts on ecosystems and human well-being,” Science, vol. 355, no. 6332, p. eaai9214, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. I. Christian, “Climate Change and Global Warming: Implications for Sub-Saharan Africa,” J. Contemp. Res., vol. 7, no. 1, 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Zougmoré, S. T. Partey, M. Ouédraogo, E. Torquebiau, and B. M. Campbell, “Facing climate variability in sub-Saharan Africa: analysis of climate-smart agriculture opportunities to manage climate-related risks,” Cah. Agric., vol. 27, no. 3, p. 34001, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Nahayo, J.B. Nsengiyumva, C. Mupenzi, R. Mind’je, and E. M. Nyesheja, “Climate Change Vulnerability in Rwanda, East Africa,” Int J Geogr Geol, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 1–9, 2019.

- G. Rwanyiziri and J. Rugema, “Climate Change Effects on Food Security in Rwanda: Case Study of Wetland Rice Production in Bugesera District,” Rwanda J Agric Sc, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 35–51, 2013. [CrossRef]

- F. Ntirenganya, “Analysis of Rainfall Variability in Rwanda for Small-scale Farmers Coping Strategies to Climate Variability,” East Afr J Sc Technol, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 75–96, 2018.

- N. J. Sebaziga, F. Ntirenganya, A. Tuyisenge, and V. Iyakaremye, “A Statistical Analysis of the Historical Rainfall Data Over Eastern Province in Rwanda,” East Afr J Sc Technol, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 33–52, 2020.

- J. Kazora et al., “Spatiotemporal variability of rainfall trends and influencing factors in Rwanda,” J Atmos Sol-Terr Phys, vol. 219, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Safari, “Trend Analysis of the Mean Annual Temperature in Rwanda during the Last Fifty Two Years,” J. Environ. Prot., vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 538–551, Jun. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Haggag, J. C. Kalisa, and A. W. Abdeldayem, “Projections of precipitation, air temperature, and potential evapotranspiration in Rwanda under changing climate conditions,” Afr J Env. Sc Technol, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 18–33, 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Ngarukiyimana et al., “Climate Change in Rwanda: The Observed Changes in Daily Maximum and Minimum Surface Air Temperatures during 1961–2014,” Front. Earth Sci., vol. 9, p. 619512, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Rwema, M. B. Sylla, B. Safari, L. Roininen, and M. Laine, “Trend analysis and change point detection in precipitation time series over the Eastern Province of Rwanda during 1981–2021,” Theor. Appl. Climatol., vol. 156, no. 2, p. 98, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Safari and J. N. Sebaziga, “Trends and Variability in Temperature and Related Extreme Indices in Rwanda during the Past Four Decades,” Atmosphere, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 1449, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Maúre et al., “The southern African climate under 1.5 °C and 2 °C of global warming as simulated by CORDEX regional climate models,” Environ. Res. Lett., vol. 13, no. 6, p. 065002, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. F. Kew et al., “Impact of precipitation and increasing temperatures on drought trends in eastern Africa,” Earth Syst Dyn, vol. 12, pp. 17–35, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Lydie, “Droughts and Floodings Implications in Agriculture Sector in Rwanda: Consequences of Global Warming,” in The Nature, Causes, Effects and Mitigation of Climate Change on the Environment, S. A. Harris, Ed., IntechOpen, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Uwimbabazi, Y. Jing, V. Iyakaremye, I. Ullah, and B. Ayugi, “Observed Changes in Meteorological Drought Events during 1981–2020 over Rwanda, East Africa,” Sustainability, vol. 14, no. 3, p. 1519, Jan. 2022. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Wolfe et al., Sensation & perception. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer, 2006. [Online]. Available: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=QO9ARccAAAAJ&hl=en&oi=sra.

- S. A. Bempah, “The role of social perception in disaster risk reduction_ Beliefs, perception, and attitudes regarding flood disasters in communities along the Volta River, Ghana,” Int J Disaster Risk Reduct, vol. 23, pp. 104–108, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Messner and V. Meyer, “FLOOD DAMAGE, VULNERABILITY AND RISK PERCEPTION – CHALLENGES FOR FLOOD DAMAGE RESEARCH,” in Flood Risk Management: Hazards, Vulnerability and Mitigation Measures, vol. 67, J. Schanze, E. Zeman, and J. Marsalek, Eds., Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2006, pp. 149–167. [CrossRef]

- Meteo Rwanda, “Climatology of Rwanda.” Accessed: Jun. 04, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.meteorwanda.gov.

- Ntwali, B. A. Ogwang, and V. Ongoma, “The Impacts of Topography on Spatial and Temporal Rainfall Distribution over Rwanda Based on WRF Model,” Atmospheric Clim. Sci., vol. 06, no. 02, pp. 145–157, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Nicholson, “The ITCZ and the Seasonal Cycle over Equatorial Africa,” Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., vol. 99, no. 2, pp. 337–348, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- NISR, “5th Population and Housing Census, Main Indicators Report,” National Institute of Statistics Rwanda, Kigali, Rwanda, 2023. [Online]. Available: http://www.statistics.gov.rw.

- M. B. Slovin, M. E. Sushka, and J. A. Polonchek, “The Value of Bank Durability: Borrowers as Bank Stakeholders,” J. Finance, vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 247–266, Mar. 1993. [CrossRef]

- Meteo Rwanda, “Dataset Documentation.” Accessed: Jul. 31, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://maproom.meteorwanda.gov.rw/maproom/Summary/index.html#tabs-2.

- I. Tikito and N. Souissi, “ODK-X: From A Classic Process To A Smart Data Collection Process,” Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. IJIM, vol. 15, no. 13, p. 28, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Helsel and L. M. Frans, “Regional Kendall Test for Trend,” Environ. Sci. Technol., vol. 40, no. 13, 2006. [CrossRef]

- H. B. Mann, “Nonparametric Tests Against Trend,” Econometrica, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 245, Jul. 1945. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Kendall, “Rank correlation methods, 4th edn,” Charles Griffin Co. Ltd., 1975, [Online].

- T. Partal and E. Kahya, “Trend analysis in Turkish precipitation data,” Hydrol. Process., vol. 20, no. 9, pp. 2011–2026, Jun. 2006. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Dietz and T. J. Killeen, “A Nonparametric Multivariate Test for Monotone Trend With Pharmaceutical Applications,” J. Am. Stat. Assoc., vol. 76, no. 373, pp. 169–174, 1981. http://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1080/01621459.1981.10 477624.

- T. Chen, G. Xia, L. T. Wilson, W. Chen, and D. Chi, “Trend and Cycle Analysis of Annual and Seasonal Precipitation in Liaoning, China,” Adv. Meteorol., vol. 2016, pp. 1–15, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. K. Margaritidis, “Site and Regional Trend Analysis of Precipitation in Central Macedonia, Greece,” Comput. Water Energy Environ. Eng., vol. 10, no. 02, pp. 49–70, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. X. Xu, K. Takeuchi, and H. Ishidaira, “Monotonic trend and step changes in Japanese precipitation,” J. Hydrol., vol. 279, no. 1–4, pp. 144–150, Aug. 2003. [CrossRef]

- D. Gamerman and H. F. Lopes, Markov chain Monte Carlo: stochastic simulation for Bayesian inference, 2nd ed. in Texts in statistical science series, no. 68. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis, 2006.

- Petris, “An R Package for Dynamic Linear Models,” J. Stat. Softw., vol. 36, no. 12, 2010. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Durbin and S. J. Koopman, “Time Series Analysis by State Space Methods by Durbin and Koopman | PDF | Normal Distribution | Estimation Theory,” Scribd. Accessed: May 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.scribd.com/doc/55179464/Time-Series-Analysis-by-State-Space-Methods-by-Durbin-and-Koopman.

- M. Laine, N. Latva-Pukkila, and E. Kyrölä, “Analysing time-varying trends in stratospheric ozone time series using the state space approach,” Atmospheric Chem. Phys., vol. 14, no. 18, pp. 9707–9725, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Rwema, B. Safari, M. Laine, M. B. Sylla, and L. Roininen, “Trends and Variability of Temperatures in the Eastern Province of Rwanda,” Int. J. Climatol., p. e8793, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- IBM, SPSS Statistics for Windows. (2021). [Online]. Available: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/spss-statistics/28.0.0.

- P. Batungwanayo, “Confronting climate change and livelihood: smallholder farmers’ perceptions and adaptation strategies in northeastern Burundi,” Reg Env. Change, vol. 23, no. 47, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Fernihough, “Simple logit and probit marginal effects in R, Working paper series,” UCD Center for economic research, University of Dublin, Ireland. Accessed: Mar. 17, 2024. [Online]. Available: http://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/WP1122.pdf.

- A. Funk, A. R. Sathyan, P. Winker, and L. Breuer, “Changing climate - Changing livelihood: Smallholder’s perceptions and adaption strategies,” J Env. Manage, vol. 259, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Lever, M. Krzywinski, and N. Altman, “Logistic regression,” Nat. Methods, vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 541–542, Jul. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Acquah-de Graft, “Farmers’ perceptions and adaptation to climate change: a willingness to pay analysis,” J. Sustain. Dev. Afr., vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 150–161, 2011.

- E. O. Asekun-Olarinmoye et al., “Public perception of climate change and its impact on health and environment in rural southwestern N,” Res. Rep. Trop. Med., vol. 5, pp. 1–10, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Kabir, M. B. Rahman, W. Smith, M. A. F. Lusha, S. Azim, and A. H. Milton, “Knowledge and perception about climate change and human health: findings from a baseline survey among vulnerable communities in Bangladesh,” BMC Public Health, vol. 16, no. 266, 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. K. Mubalama, D. M. Masumbuko, D. R. Mweze, G. T. Banswe, and P. A. Mirindi, “Farmers’ Perceptions towards Climate Change, and Meteorological Data in Kahuzi-Biega National Park Surroundings, Eastern DR. Congo,” Int. J. Innov. Res. Dev., vol. 9, no. 6, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Balasha, A. B. Ndele, B. B. Murhula, and V. M. Ngabo, “Perceived Impacts of Climate Change and Farmers’ Choices of Adaptation Practices in the South Kivu’s Marshlands,” J Appl Agric Econ Policy Anal, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 18–24, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Abid, J. Scheffran, U. A. Schneider, and M. Ashfaq, “Farmers’ perceptions of and adaptation strategies to climate change and their determinants: the case of Punjab province, Pakistan,” Earth Syst. Dyn., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 225–243, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- IRDP, “Determinants of inorganic fertilizers and improved seeds along with extension services support for agricultural productivity in Rwanda. final policy issues and recommendations,” Institute of Research and Dialogue for Peace, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://irdp.rw/wp- content/uploads/IRDP%20Agri%20Final%20Policy%20brief%20Final.pdf.

- L. B. Chang’a, P. Z. Yanda, and J. Ngana, “Indigenous knowledge in seasonal rainfall prediction in Tanzania: A case of the South-western Highland of Tanzania,” J Geogr Reg Plann, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 66–72, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Radeny et al., “Indigenous knowledge for seasonal weather and climate forecasting across East Africa,” Clim. Change, vol. 156, no. 4, pp. 509–526, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Ziervogel and A. Opere, “Integrating meteorological and indigenous knowledge- based seasonal climate forecasts for the agricultural sector: lessons from participatory action research in sub-Saharan Africa.” Accessed: Jul. 20, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/items/a4b47199-a1ba-4047-a1e4-32ef2bc48c00.

- J. M. Kalanda, C. Ngongondo, L. Chipeta, and F. Mpembeka, “Integrating indigenous knowledge with conventional science: enhancing localized climate and weather forecasts in Nessa, Mulanje, Malawi,” Phys Chem Earth, vol. 36, no. 14–15, pp. 996–1003, 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. Kolawole, P. Wolski, B. Ngwenya, and G. Mmopelwa, “Ethnometeorology and scientific weather forecasting: small farmers and scientists’ perspectives on climate variability in the Okavango Delta, Botswana,” Clim. Risk Manag, vol. 4, pp. 43–58, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Nkuba, R. Chanda, G. Mmopelwa, E. Kato, M. N. Mangheni, and D. Lesolle, “Influence of Indigenous Knowledge and Scientific Climate Forecasts on Arable Farmers’ Climate Adaptation Methods in the Rwenzori region, Western Uganda,” Environ. Manage., vol. 65, no. 4, pp. 500–516, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Butera, T. K. Kim, and S. H. Choi, “Determinant Factors of Rice Farmers’ Selection of Adaptation Methods to Climate Change in Eastern Rwanda,” Korean J Org Agric, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 241–253, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Sarkodie, P. Rufangura, Herath MPC Jayaweera, and P. A. Owusu, “Situational Analysis of Flood and Drought in Rwanda,” p. 1773839 Bytes, 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Harvey et al., “Extreme vulnerability of smallholder farmers to agricultural risks and climate change in Madagascar,” Philos Trans Roy Soc B, vol. 369, no. 1639, pp. 2–22, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1098%2Frstb.2013.0089.

- E. C. Brevik, “The Potential Impact of Climate Change on Soil Properties and Processes and Corresponding Influence on Food Security,” Agriculture, vol. 3, pp. 398–417, 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Bele, D. J. Sonwa, and A. M. Tiani, “Local Communities Vulnerability to Climate Change and Adaptation Strategies in Bukavu in DR Congo,” J. Environ. Dev., vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 331–357, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- L. M. C. S. Menike and K. A. G. P. K. Arachchi, “Adaptation to Climate Change by Smallholder Farmers in Rural Communities: Evidence from Sri Lanka,” Procedia Food Sci., vol. 6, pp. 288–292, 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Abera, T. Debele, and D. Wegary, “Effects of Varieties and Nitrogen Fertilizer on Yield and Yield Components of Maize on Farmers Field in Mid Altitude Areas of Western Ethiopia,” Int. J. Agron., vol. 2017, pp. 1–13, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Kamran et al., “The Impact of Different P Fertilizer Sources on Growth, Yield and Yield Component of Maize Varieties,” Agri Res Tech Open Access J, vol. 13, no. 3, 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. Murthy, S. Dutta, V. Varghese, and P. Kumar, “Impact of Agroforestry Systems on Ecological and Socio-Economic Systems: A Review,” Glob J Sci Front Res, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 15–28, 2016.

- T. O. Jawo, N. Teutscherová, M. Negash, K. Sahle, and B. Lojka, “Smallholder coffee- based farmers’ perception and their adaptation strategies of climate change and variability in South-Eastern Ethiopia,” Int J Sustain Dev World Ecol, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 533–547, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Rajan, P. Manjet, and K. Solanke, “Organic Mulching- A Water Saving Technique to Increase the Production of Fruits and Vegetables – Current Agriculture Research Journal.” Accessed: May 01, 2025. [Online]. Available: http://www.agriculturejournal.org/volume5number3/organic-mulching-a-water-saving-technique-to-increase-the-production-of-fruits-and-vegetables/.

- World Bank, “Climate-Smart Agriculture in Rwanda. CSA Country Profiles for Africa, Asia, and Latin America and the Caribbean Series,” World Bank, 2015. [Online]. Available: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/2019- 06/CSA%20RWANDA%20NOV%2018%202015.pdf.

- E. Bryan, T. T. Deressa, G. A. Gbetibouo, and C. Ringler, “Adaptation to climate change in Ethiopia and South Africa: options and constraints,” Env. Sci Policy, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 413–426, 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. S. Juana, Z. Kahaka, and F. N. Okurut, “Farmers’ Perceptions and Adaptations to Climate Change in Sub-Sahara Africa: A Synthesis of Empirical Studies and Implications for Public Policy in African Agriculture,” J Agric Sci, vol. 5, pp. 121–135, 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Sani, “Farmers’ Perception, Impact and Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change among Smallholder Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review,” J. Resour. Dev. Manag., vol. 26, no. 0, p. 1, 2016.

- MoE, “Strategic Programme for Climate Resilience (SPCR) Rwanda,” Kigali, Rwanda, 2017. [Online]. Available: http://www.fonerwa.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/SPCR.pdf.

- T. P. Cox, “Farming the battlefield: the meanings of war, cattle and soil in South Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo,” Disasters, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 233–248, 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. Abebaw and M. G. Haile, “The impact of cooperatives on agricultural technology adoption: Empirical evidence from Ethiopia,” Food Policy, vol. 38, pp. 82–91, Feb. 2013. [CrossRef]

- E. Verhofstadt and M. Maertens, “Smallholder cooperatives and agricultural performance in Rwanda: do organizational differences matter?,” Agric. Econ., vol. 45, no. S1, pp. 39–52, Nov. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Manda et al., “Does cooperative membership increase and accelerate agricultural technology adoption? Empirical evidence from Zambia,” Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change, vol. 158, p. 120160, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Manda et al., “Does cooperative membership increase and accelerate agricultural technology adoption? Empirical evidence from Zambia,” Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change, vol. 158, p. 120160, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Destaw and M. M. Fenta, “Climate change adaptation strategies and their predictors amongst rural farmers in Ambassel district, Northern Ethiopia, Jamba,” J Disaster Risk Stud, vol. 13, no. (1), 2021. https://doi.org/10.4102%2Fjamba.v13i1.974.

| Zone | District | Sector | Cell |

|---|---|---|---|

| North | Nyagatare (33) | Nyagatare (1) | Nyagatare (1) |

| Gatunda (9) | Nyamirembe (9) | ||

| Mukama (6) | Gihengeri (1), Rugarama (5) | ||

| Mimuri (4) | Mimuri (2), Rugari (2) | ||

| Katabagemu (13) | Barija (3), Nyakigando (9), Ryaruganzu (1) | ||

| Gatsibo (35) | Ngarama (10) | Nyarubungo (9), Cyigashi (1) | |

| Nyagihanga (14) | Gitinda (14) | ||

| Kabarore (11) | Nyabikiri (10), Nyabikenke (1) | ||

| Central | Kayonza (36) | Ndego (10) | Byimana (7), Kiyovu (3) |

| Kabare (12) | Rubumba (10), Cyarubare (1), Karubimba (1) | ||

| Kabarondo (14) | Cyabajwa (14) | ||

| South | Ngoma (74) | Mutenderi (24) | Karwema (19), Kibare (5) |

| Kazo (29) | Kinyonzo (29) | ||

| Murama (21) | Sakara (19), Rurenge (1), Mvumba (1) | ||

| Kirehe (26) | Nyamugali (10) | Nyamugali (7), Kiyanzi (3) | |

| Kigina (11) | Gatarama (11) | ||

| Musaza (5) | Mubuga (4), Nganda (1) |

| 1983-2021 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Season | Tx | Tn | T |

| JF | 0.88 [-1.02-2.74] | 1.71 [0.66-2.83] | 1.47 [0.28-2.62] |

| MAM | 0.16 [-1.60-2.00] | 2.37 [1.07-3.68] | 1.69 [0.22-2.93] |

| JJA | 0.85 [-0.27-1.97] | 3.37 [1.75-4.81] | 2.37 [0.94-3.68] |

| SOND | -0.37 [-2.17-1.42] | 2.72 [1.10-4.46] | 1.17 [-0.18-2.47] |

| Annual | 0.30 [-1.31-1.71] | 2.95 [1.64-4.45] | 1.87 [0.61-3.19] |

| 1981-2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Season | Rainfall amount mm/day/year | Onset days/year |

Cessation days/year |

Season Duration days/year |

| MAM | -0.01 | -0.21 | 0.00 | 0.21 |

| SOND | 0.00 | -0.21* | 0.00 | 0.23* |

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 88 | 43 | |

| Male | 116 | 57 | ||

| Age | 20-34 | 48 | 24 | 43.66 |

| 35-49 | 98 | 48 | ||

| 50-64 | 48 | 24 | ||

| 65-80 | 10 | 5 | ||

| Farming Experience (years) | 1-20 | 96 | 47 | 22.18 |

| 21-40 | 97 | 48 | ||

| 41-60 | 10 | 5 | ||

| Time in farm per day (unit is second) | ≤ 14400 | 21 | 10 | 20880 |

| 18000-28800 | 167 | 82 | ||

| ≥ 32400 | 16 | 8 | ||

| Education | None | 34 | 17 | |

| Primary | 124 | 61 | ||

| Secondary_level_1_(Senior_3) | 22 | 11 | ||

| Secondary_level_2_(Senior_6) | 17 | 8 | ||

| Technical_vocation | 6 | 3 | ||

| University | 1 | 0.5 | ||

| Farm size (unit is square meters) | 0-10000 | 144 | 71 | 13000 |

| 11000-20000 | 40 | 20 | ||

| > 20000 | 20 | 10 | ||

| Farm location | Hillside | 97 | 48 | |

| Wetland | 30 | 15 | ||

| Both | 77 | 38 | ||

| Farm ownership status | Owner | 108 | 53 | |

| Tenant | 34 | 17 | ||

| Both | 62 | 30 | ||

| Farming goals | Home consumption | 62 | 30 | |

| Income | 4 | 2.0 | ||

| Both (Income and home consumption) | 138 | 68 | ||

| Main crops | Maize | 184 | 90 | |

| Beans | 181 | 89 | ||

| Cassava | 63 | 31 | ||

| Livestock ownership | Yes | 131 | 64 | |

| No | 73 | 36 | ||

| Group membership | Yes | 76 | 37 | |

| No | 128 | 63 | ||

| Exchanging info | Yes | 161 | 79 | |

| No | 43 | 21 | ||

| Access to weather info | Yes | 99 | 49 | |

| No | 105 | 51 | ||

| Access to bank service | Yes | 119 | 58 | |

| No | 85 | 42 | ||

| Household size | 1-5 | 136 | 67 | 5 |

| 6-10 | 65 | 32 | ||

| 11-15 | 3 | 1.5 |

| Onset skills | Cessation skills | ||||

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | ||

| Cloud | 72 | 35 | Rainfall distribution | 93 | 46 |

| Wind | 38 | 19 | Rainfall amount | 36 | 18 |

| Temperature | 27 | 13 | Rainfall duration | 35 | 17 |

| Lightning | 12 | 6 | Rainfall frequency | 22 | 11 |

| Do not know | 32 | 16 | Cloud | 16 | 8 |

| Temperature | 13 | 6 | |||

| Wind | 4 | 2 | |||

| Do not know | 25 | 12 | |||

| Adaptation Strategies | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Agroforestry/Planting trees (PT) | 81 | 40 |

| Changing crop varieties (CCV) | 47 | 23 |

| Application of fertilizer (organic and inorganic) (AF) | 47 | 23 |

| Changing planting dates (CPD) | 54 | 26 |

| Soil conservation (SC) | 50 | 25 |

| Focus on wetland (FWL) | 21 | 10 |

| Use irrigation (UI) | 43 | 21 |

| Mulching (M) | 9 | 4 |

| Use of pesticides (UP) | 15 | 7 |

| Planting grass (PG) | 11 | 5 |

| Barriers | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Lack of finance | 58 | 28 |

| Inadequate info | 39 | 19 |

| Lack of material | 43 | 21 |

| Lack of weather info | 24 | 12 |

| Shortage of farm inputs | 40 | 20 |

| Lack of water | 14 | 7 |

| High cost of input | 7 | 3 |

| Land location | 4 | 2 |

| High cost of material | 4 | 2 |

| Omnibus Tests of Model Coefficients | ||||

| Models | Chi-square | Degree of freedom(df) | P-value | |

| Agroforestry/Planting trees (PT) | 34.026 | 15 | .003 | |

| Changing crop varieties (CCV) | 29.94 | 15 | .012 | |

|

Application of fertilizer (Organic and inorganic) (AF) |

45.219 | 15 | .000 | |

| Hosmer and Lemeshow Test | ||||

| Chi-square | Degree of freedom(df) | P-value | ||

| Agroforestry/Planting trees (PT) | 5.316 | 8 | .723 | |

| Changing crop varieties (CCV) | 2.59 | 8 | .957 | |

|

Application of fertilizer (organic and inorganic) (AF) |

9.611 | 8 | .293 | |

| Model Summary | ||||

| -2 Log likelihood | Cox & Snell R Square | Nagelkerke R Square | Model correctness (%) | |

| Agroforestry/Planting trees (PT) | 240.068 | 0.154 | 0.208 | 66.7 |

| Changing crop varieties (CCV) | 190.278 | 0.137 | 0.207 | 77.5 |

|

Application of fertilizer (Organic and inorganic) (AF) |

174.999 | 0.199 | 0.301 | 82.4 |

| Variables | PT | CCV | AF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.700 [0.345-1.418] | 0.477* [0.205-1.109] | 0.408** [0.167-1.000] |

| Age | 0.965 [0.915-1.017] | 0.963 [0.904-1.026] | 1.009 [0.951-1.070] |

| Education level | 1.037 [0.717-1.502] | 0.963 [0.629-1.474] | 1.013 [0.635-1.616] |

| Farmer experience(years) | 1.019 [0.969-1.072] | 1.036 [0.977-1.099] | 1.002 [0.946-1.061] |

| Time spent/day (Hours) | 1.007 [0.810-1.252] | 0.843 [0.647-1.099] | 0.751* [0.553-1.020] |

| Farm size (hectares) | 0.885 [0.690-1.134] | 1.013 [0.780-1.314] | 0.773 [0.498-1.201] |

| Farm location | 0.739 [0.513-1.064] | 1.052 [0.697-1.587] | 1.926** [1.225-3.028] |

| Land-holding status | 1.158 [0.803-1.670] | 1.324 [0.867-2.022] | 1.008 [0.638-1.591] |

| Farming goal | 1.668** [1.099-2.531] | 1.245 [0.745-2.083] | 0.770 [0.460-1.288] |

| Livestock ownership | 1.979* [0.965-4.060] | 1.250 [0.530-2.948] | 1.674 [0.679-4.128] |

| Farmer group membership | 1.587 [0.776-3.245] | 2.740** [1.206-6.226] | 3.926** [1.556-9.906] |

| Exchanging info | 2.024 [0.770-5.320] | 3.167* [0.810-12.375] | 1.118 [0.321-3.895] |

| Access to weather info (Radio) | 1.234 [0.639-2.384] | 1.272 [0.592-2.732] | 2.271* [0.978-5.276] |

| Access to bank services | 0.703 [0.344-1.437] | 0.494* [0.216-1.127] | 0.286** [0.116-0.706] |

| Household size (Individuals) | 1.043 [0.893-1.218] | 1.009 [0.846-1.205] | 0.994 [0.818-1.208] |

| Constant | 0.261 | 0.203 | 0.403 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).