1. Introduction

Antrodia cinnamomea, synonym of

Taiwanofungus camphoratus, is a parasitic fungus that grows only on the trunk of the tree

Cinnamomum kanehirae, a species endemic to Taiwan [

1]. It is a well-known traditional medicinal fungus in Taiwan and is consumed as a health food or used in the production of health supplements. Over 160 chemical compounds have been extracted and identified from

A. cinnamomea [

2], among which the triterpenoid compounds are considered to have the greatest biological activity [

3]. Of these, antcins are unique to

A. cinnamomea, and

A. salmonea (synonymous with

Taiwanofungus salmoneus)[

2] and their medicinal properties include anti-cancer[

4], anti-oxidative[

5], and anti-inflammatory effects[

6].

The therapeutic effects of

A. cinnamomea have caused an increase in demand for the fungus. However, the fruiting body has a very slow growth rate in the wild, leading to overharvesting and the destruction of many endangered

C. kanehirae trees [

1]. In response, the Taiwanese government has placed prohibitions and restrictions on the harvesting of

C. kanehirae, further increasing demand[

7]. As a result of this, efforts to culture the fungus in vitro have been made.

Submerged culture is an alternative method of cultivating

A. cinnamomea in vitro for commercial use, allowing for greater production of mycelium within a smaller area alongside reduced possibility of contamination[

3]. Yet, studies have shown that mycelia produced by submerged culture show drastically reduced triterpenoid content compared to wild-harvested fruiting bodies (basidiomata)[

2]. Alternatively, solid culture has also been used to produce

A. cinnamomea mycelia for therapeutic purposes. Solid culture presents advantage over submerged culture in that the formation of fruiting bodies is possible[

8]. Lin et al.[

9] found that abrasion of hyphae with cotton swabs was able to induce the production of fruiting bodies in

A. cinnamomea grown on agar plates, and found that the chemical profiles of plate-grown mycelia and fruiting bodies differed. Although it has also been shown that the induction of fruiting bodies is inconsistent[

10].

In addition to the culture method, fungal growth and secondary metabolite content also differs according to environmental conditions[

11]. The carbon source present in culture media is one of the major factors affecting fungal growth. Carbohydrates—including monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides—are the main energy source of fungi, and their availability influences fungal growth-rate, metabolism, and reproduction. The presence of monosaccharides causes a tendency toward asexual reproduction in fungi, whereas the presence of disaccharides and polysaccharides leads to increased sexual reproduction[

12]. While studies have investigated the impact of carbon source on the accumulation of mycelial biomass of

A. cinnamomea[

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]; few have examined the effect of carbon source on triterpenoid production.

The colour of

A. cinnamomea typically ranges from yellow to a dark reddish-brown, but a white variant of the fungus also exists in the wild. This variant is rare and said to be more medicinally potent, making it more desirable and thus expensive, but has not been extensively studied[

18]. Chung et al.[

19] found that the phytomic similarity index values for common triterpenoids of variants of red

A. cinnamomea were similar, while that of the white variant was notably different, suggesting that the white variant may have different therapeutic value. However, another study found that the concentrations of most of 10 major triterpenoid compounds found in white

A. cinnamomea were lower than that of the common variant, contrary to the beliefs of traditional Chinese medicine practitioners[

20]. Furthermore, Liu[

21] observed that the growth of different

A. cinnamomea variants (including a white variant) did not respond in the same way different carbon sources—the carbohydrate that resulted in the greatest mycelial dry weight was different among variants. However, the differences in triterpenoid content between wild-type and white

A. cinnamomea in response to different carbon sources has not yet been examined.

This study examines the effect of different culture methods and carbon sources on the triterpenoid content of two A. cinnamomea variants: a red, wild-type variant and a white variant.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. A. cinnamomea Strains and Preparation

Two

A. cinnamomea strains previously studied by Liu[

21] known as “A1” and “W” were obtained. A1 (hereafter referred to as AC) is a wild-type

A. cinnamomea variant with orange hyphae, while W is a mutant variant with white hyphae. Both were obtained from Da-Shan Farm in Zhushan Township, Nantou County, Taiwan. Using distilled water, spores were washed from the basidiomata onto plates, and diluted 10 times. Next, 1 µL of this suspension was taken and observed under a microscope to ascertain the spore count per microlitre. This dilution was continued until only one spore remained per microlitre. The monospore was inoculated onto lysogeny broth agar (LB) and incubated for 24 h at 27 °C. After 24 h, the LB agar media was cut into 1 × 1-mm2 squares containing hyphae for inoculation onto malt extract agar (MEA) for 1 month at 27 °C.

2.2. A. cinnamomea Culture

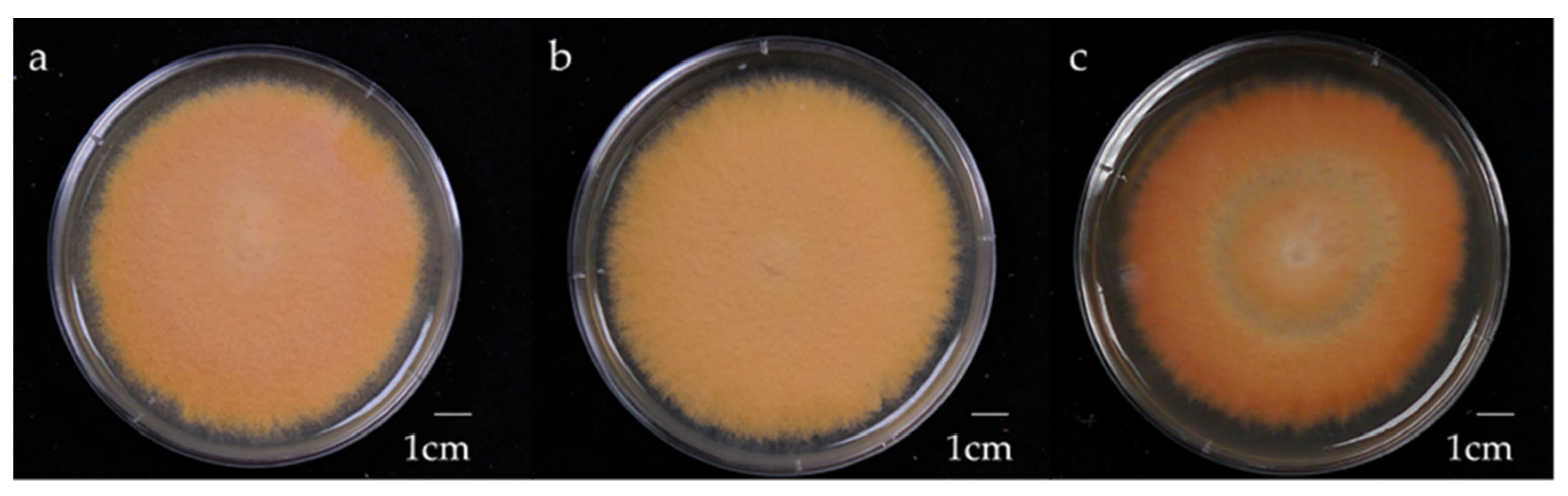

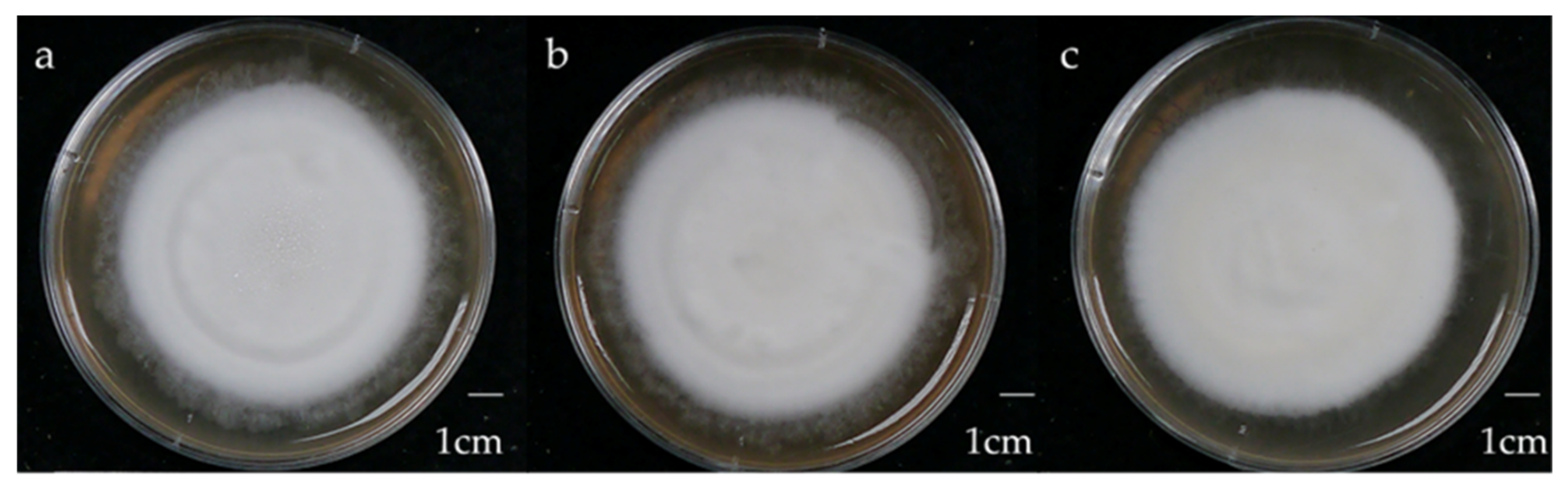

The AC (

Figure 1) and W (

Figure 2) strains were cultured on media with three carbohydrate sources: glucose, maltose, and sucrose. The culture methods included solid-state culture on MEA and submerged culture in malt extract broth (MEB) in a 250-mL flask. Both MEA and MEB contained 1% malt extract, 1% peptone, 1% agar, and 1% carbohydrate (glucose, maltose or sucrose), with a pH of 5.5. The media were sterilized in an autoclave (TOMIN, New Taipei City, Taiwan) at 121 °C for 25 minutes, whereas the carbohydrate sources were sterilized via being passed through a 45-µm filter.

A. cinnamomea was cultured in a growth chamber at 27 °C for 1 month, and the submerged culture was stirred at 120 rpm. The samples were harvested and dried in an oven at 45 °C for 14 days and their weight was determined.

2.3. Triterpenoid Extraction and Analysis

To extract triterpenoid compounds present in the sample, 0.1g of sample was extracted in 5 mL of 90% acetic acid under ultrasonication for 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 15 min. Then, to determine the triterpenoid content of the sample, 0.5 mL of the extracted sample was taken and dried at 80 °C in an oven for 2 weeks. After drying, 0.2 mL of 5% (w/v) vanillin acetic acid and 0.08 mL of perchloric acid were reacted at 60 °C with ultrasonic oscillations for 20 min until the colour of the sample was homogenous. After homogenization, acetic acid was used to dilute the solution five times. Next, the total triterpenoid content of the sample was determined through spectrophotometry at 550 nm.

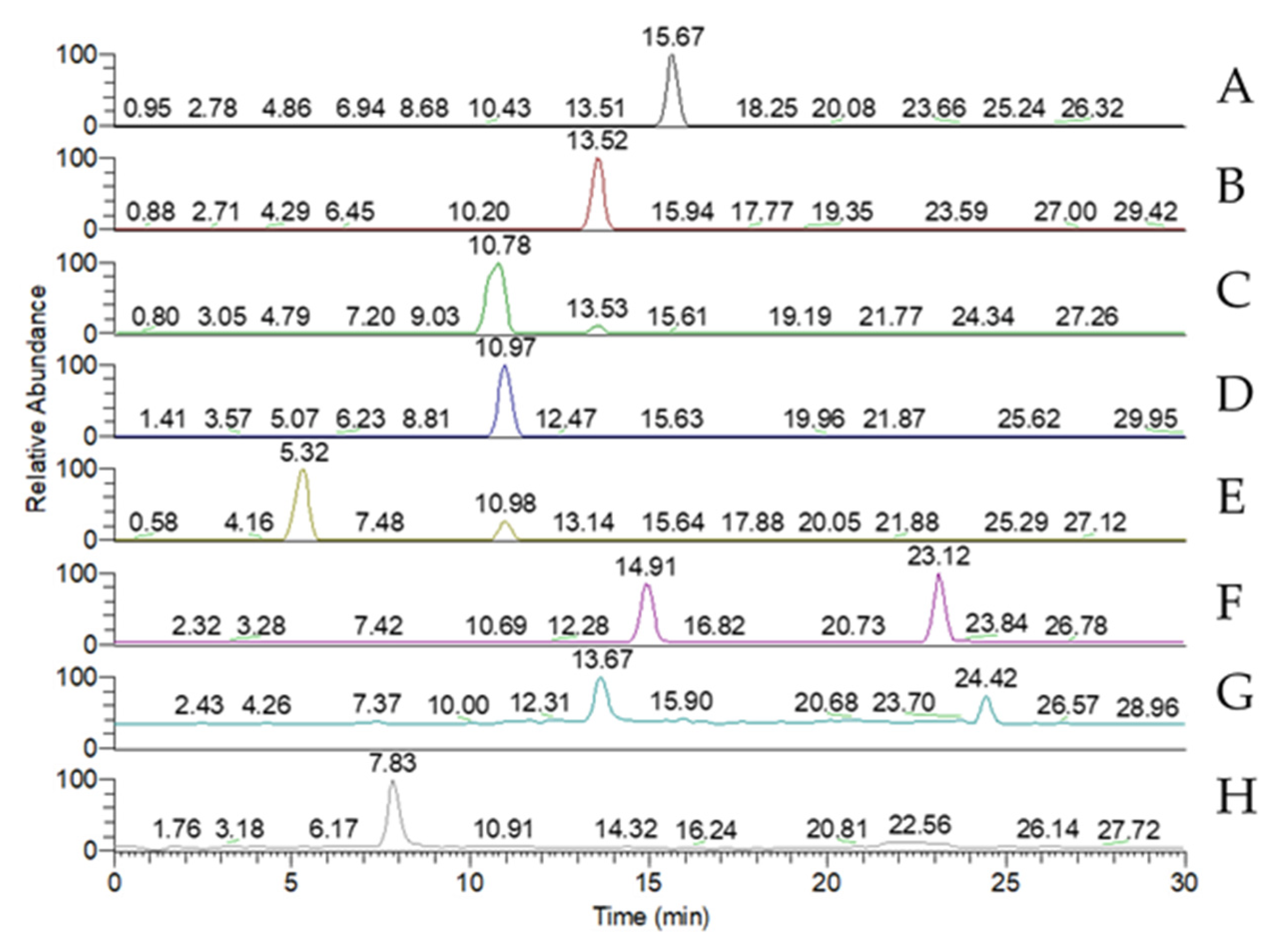

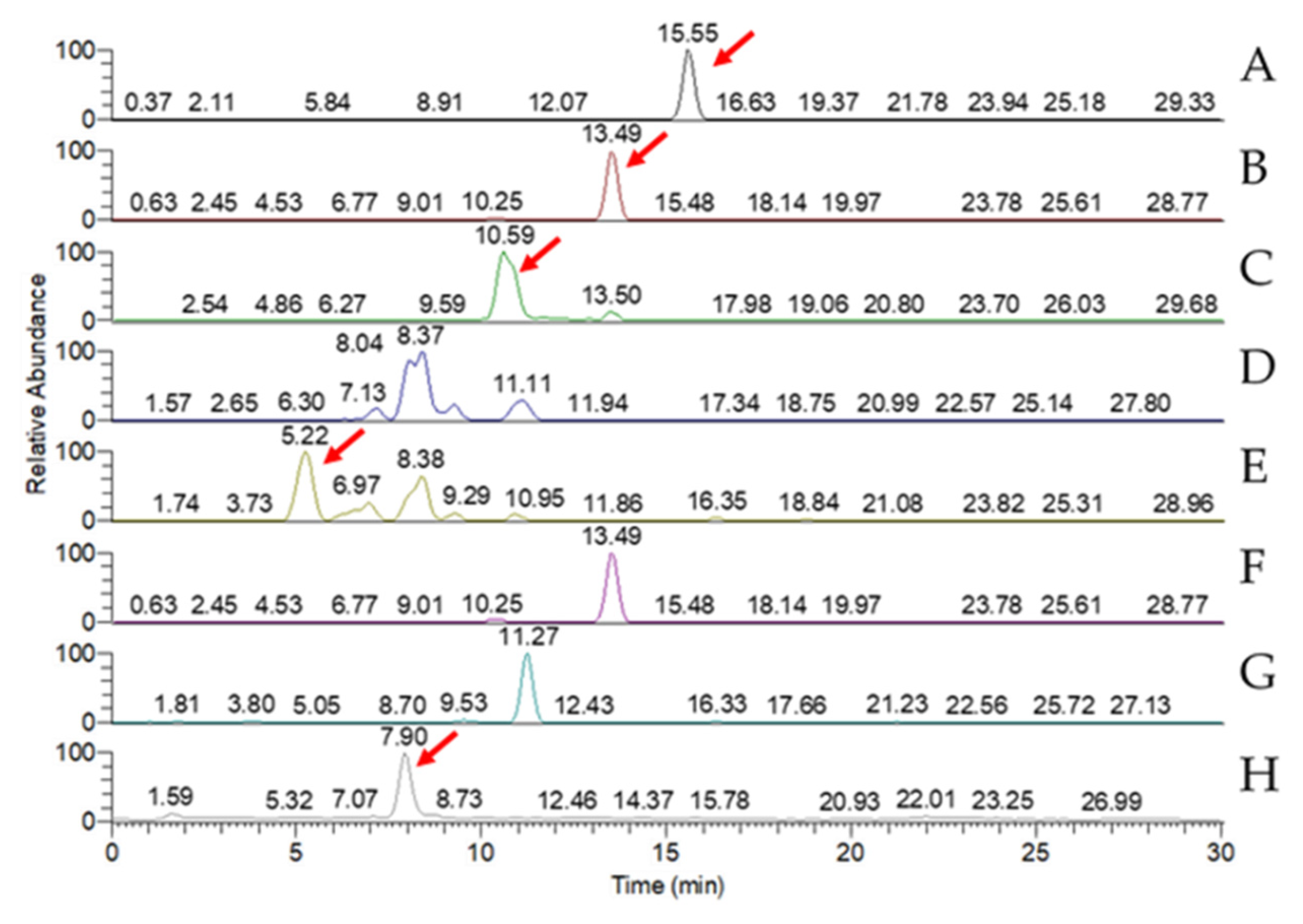

A liquid chromatograph (LC) DGU-20A (SHIMADZU, Kyoto, Japan) with a TSQ quantum access MAX triple stage quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, USA) was used to identify the presence of eight key triterpenoid compounds—antcin A, antcin B, antcin C, antcin H, antcin K, dehydroeburioic acid (DEA), dehydrosulphurenic acid (DSA), and 2,4-dimethoxy-6-methylbenzene-1,3-diol (DMMB)—and their concentrations. For mass spectrometry (MS), the column Syncronis C18 (150 × 2.1 mm2; Thermo Scientific) was used. Extracts from the 1% glucose-media samples were used for these analyses. The sample volume used for triterpenoid quantification was 5 μL. The flow rate was 0.4 mL/min, the binary gradient was (A) water with 0.2% formic acid and (B) acetonitrile. The mobile-phase gradient was as follows: 0 min, 35% (B); 7 min, 55% (B); 10 min, 65% (B); 19 min, 100% (B); 21 min, 65% (B); 25 min, 55% (B); 25.1 min, 35% (B); and 30 min, 35% (B). Triterpenoids were detected under MS/MS conditions, with the chromatograph running in the multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) mode.

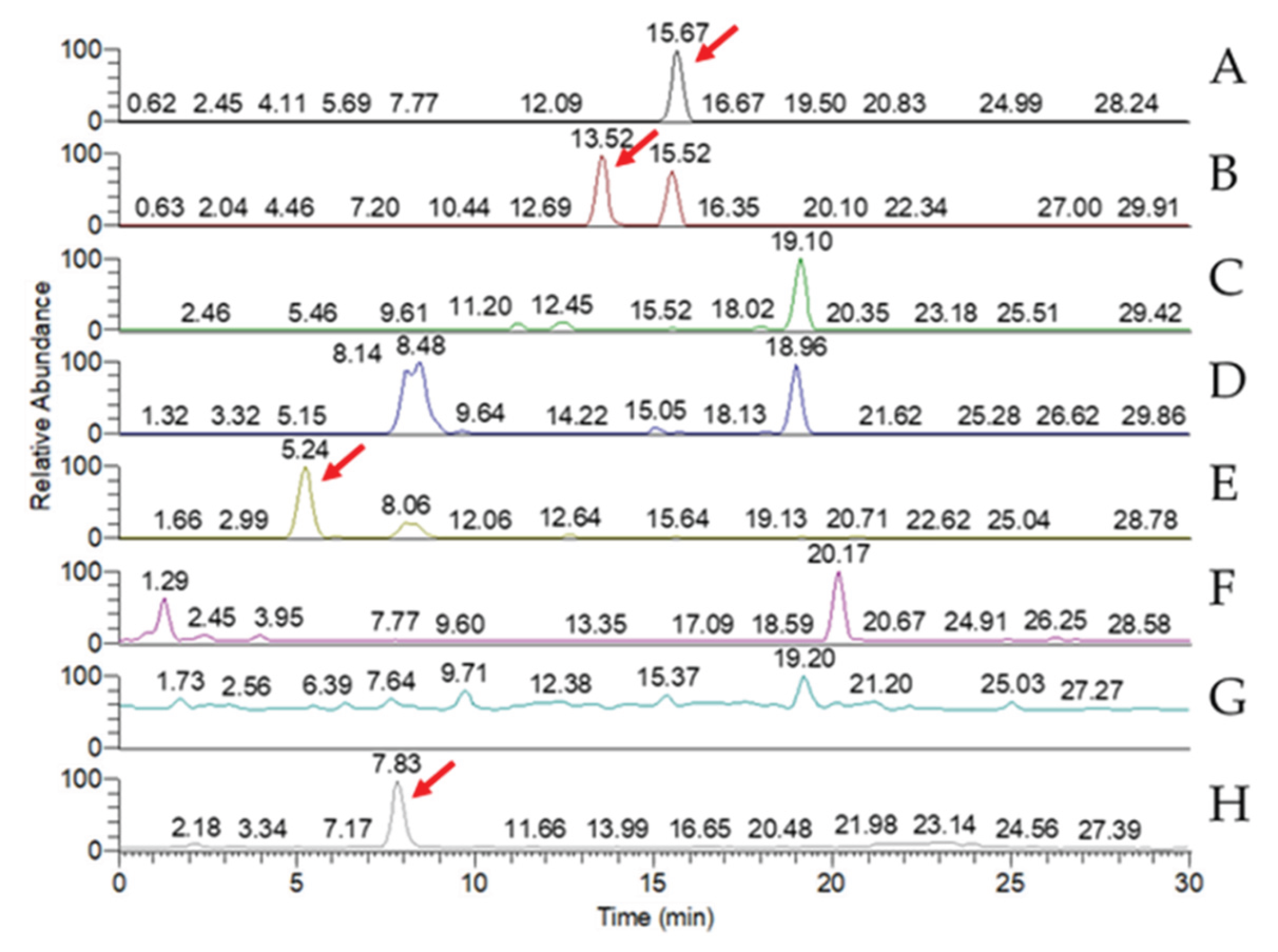

Table 1 and

Figure 3 show the MRM conditions of the MS analysis and the standard peaks of the eight key triterpenoid compounds respectively.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All the experiments were performed in triplicate to verify their reproducibility. The data were analysed using Statistical Product and Service Solution (SPSS; version 22). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare means and Duncan’s multiple range tests were used for post-hoc analysis (p < 0.05).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Culture Method and Carbohydrate Source on Biomass

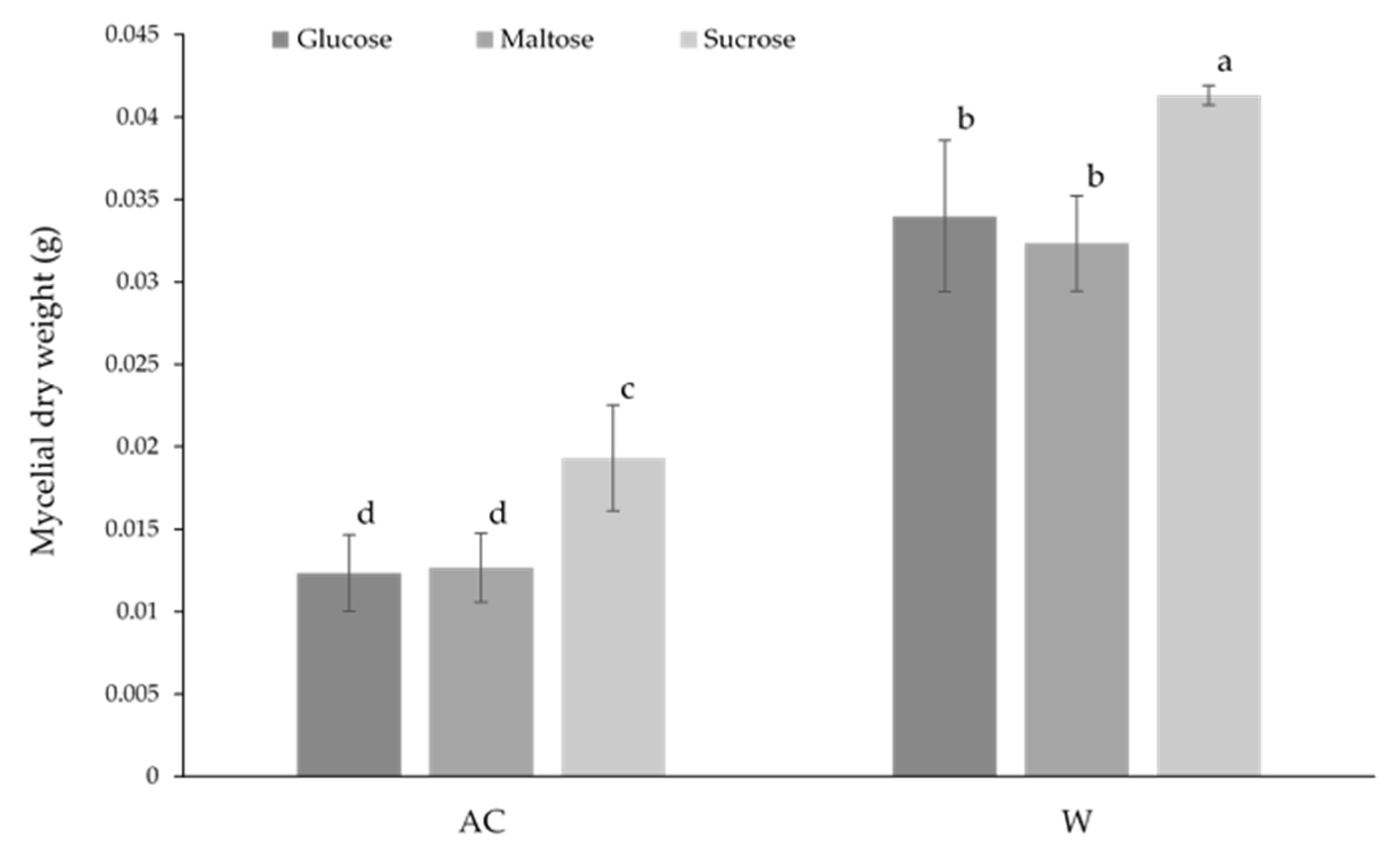

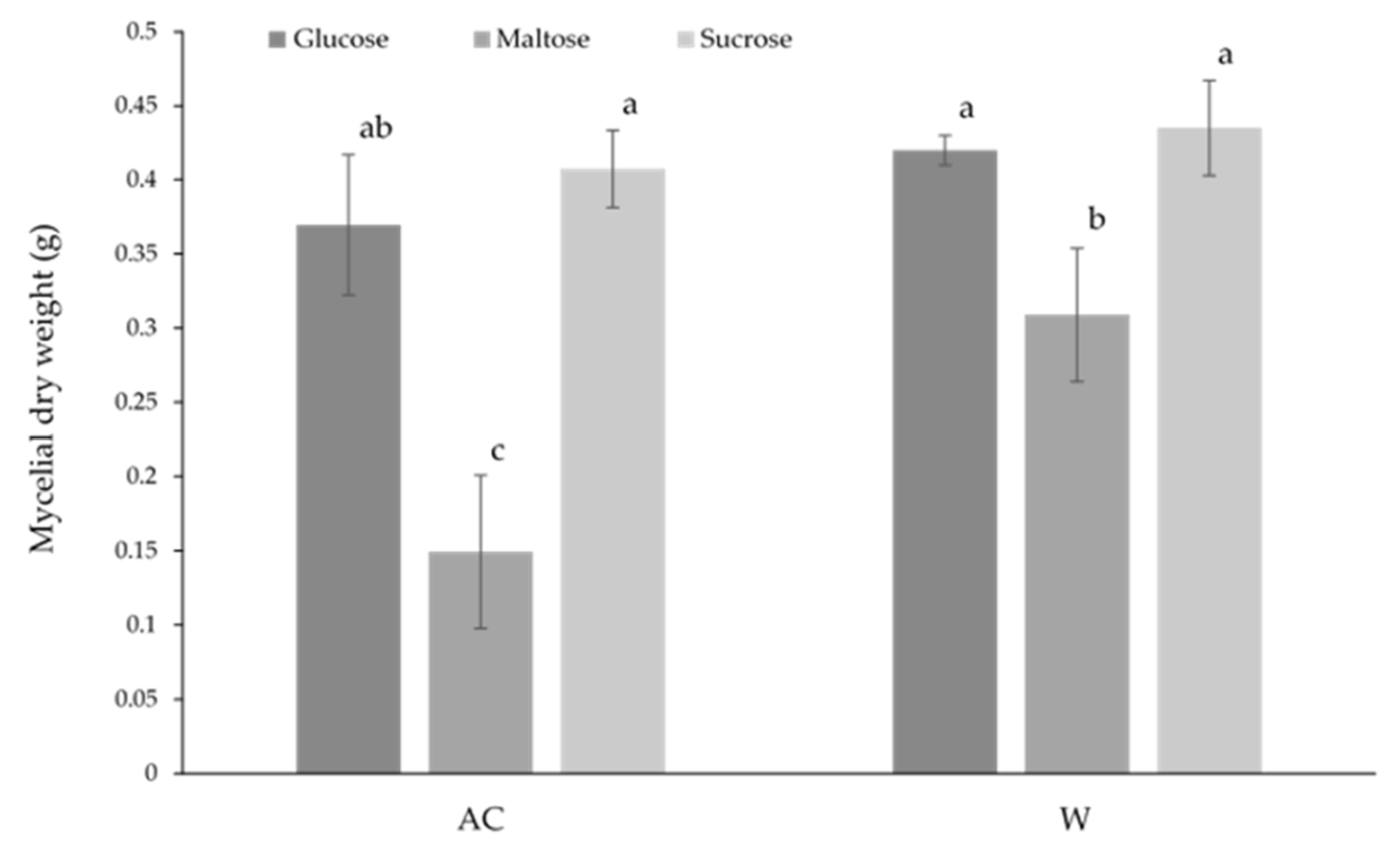

In solid-state culture (

Figure 4), the mycelial dry weight of the W strain was significantly greater under all conditions compared to the AC strain, with the dry weight of the W strain being more than double that of the AC strain when compared to the same carbohydrate culture. Of all carbon sources, sucrose was found to result in significantly greater biomass for both strains. Within both strains, there was no significant difference between culture with glucose or maltose.

Figure 5 shows that there were no significant differences in biomass between the two strains when grown with glucose or sucrose in submerged culture. However, the culture with maltose as the carbon source resulted in significantly greater mycelial dry weight for the W strain compared to the AC strain.

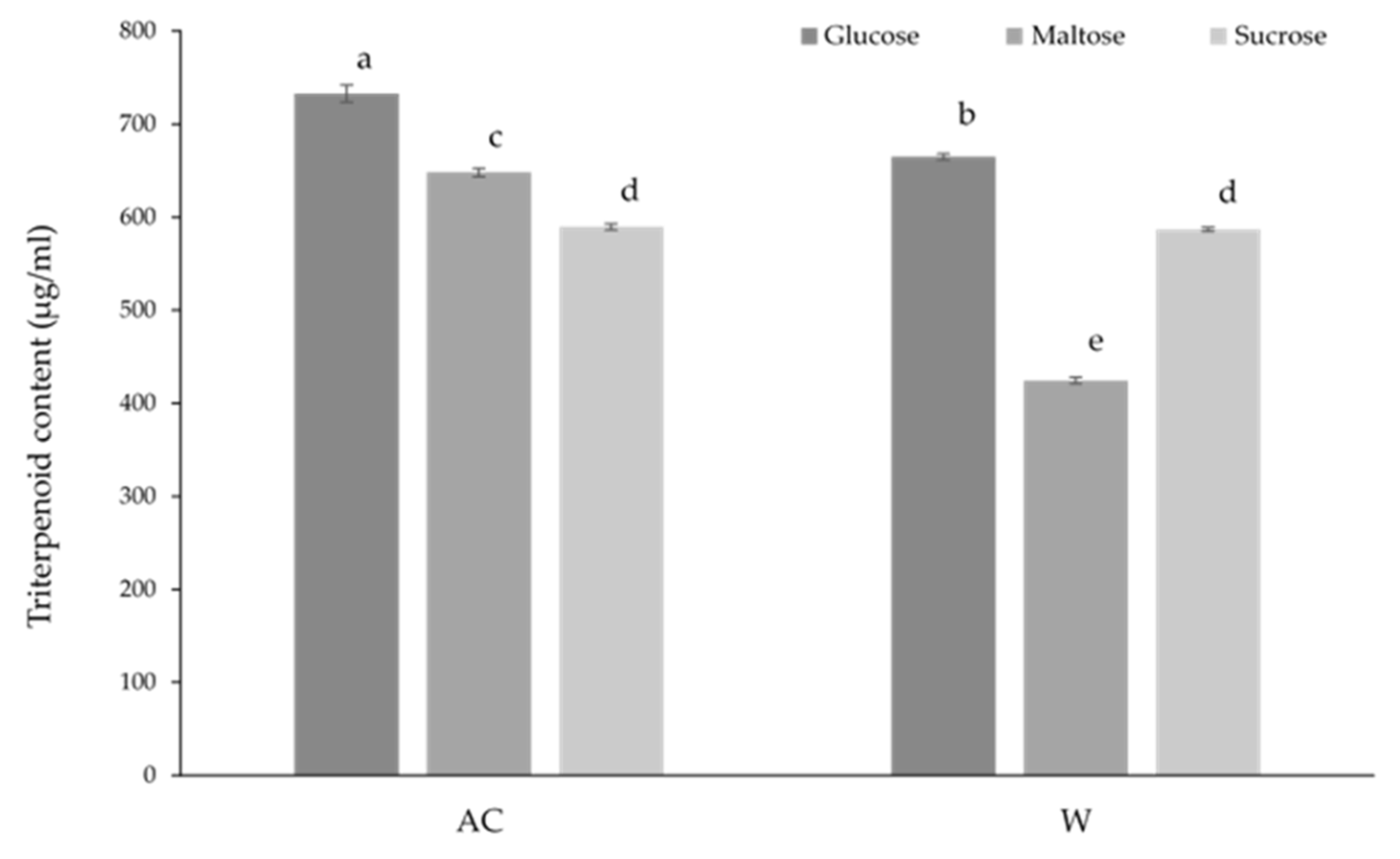

3.2. Effect of Culture Method and Carbohydrate Source on Triterpenoid Content

The effect of different carbohydrates on the triterpenoid content of

A. cinnamomea from solid-state culture is shown in

Figure 6. The AC strain grown with glucose media resulted in the greatest total triterpenoid content overall, while glucose media also showed the highest triterpenoid content among the W strain conditions. The lowest triterpenoid content was found in the W strain culture cultivated on maltose media. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in triterpenoid content between both strains when sucrose was the carbon source.

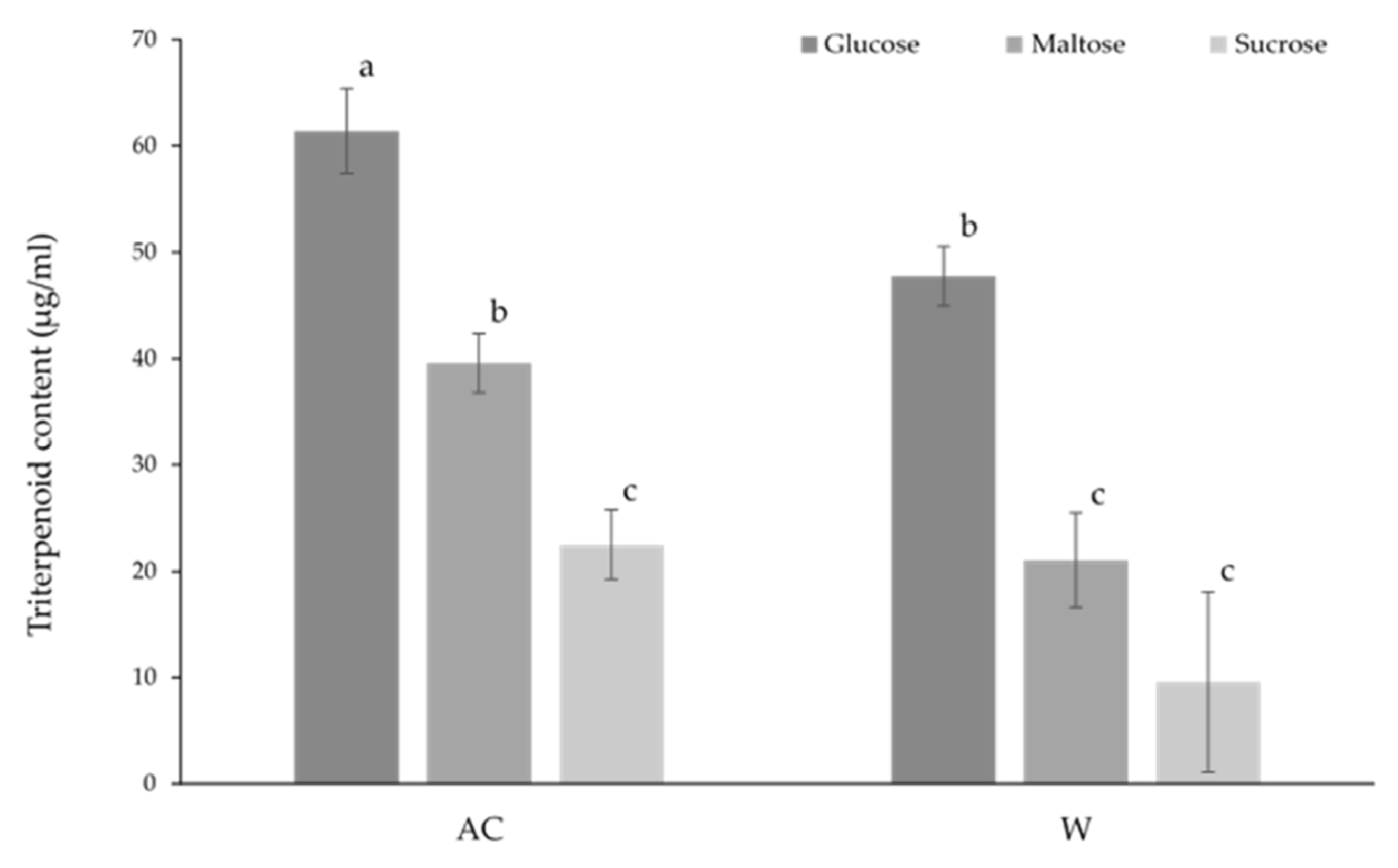

As with solid state culture, media containing glucose resulted in the highest triterpenoid content in both strains in the submerged culture, with the glucose-cultured AC strain containing the highest triterpenoid content overall (

Figure 7). The AC strain cultured on maltose had a similar triterpenoid content to that of the W strain cultured on media containing glucose. No difference was observed between the AC strain grown on sucrose media and the W strain grown on either maltose or sucrose media.

LC-MS analysis of the triterpenoid extract of the AC strain cultured in solid-state culture with 1% glucose (

Figure 8) showed that, of the eight key triterpenoids, five were detected in the extract: Antcin A, Antcin B, Antcin C, Antcin K, and DMMB. In submerged culture, extract of the AC strain showed the presence of four of the key compounds: Antcin A, Antcin B, Antcin K, and DMMB (

Figure 9). None of the eight triterpenoids were detected in the W strain samples for either culture method.

Table 2 shows the concentrations of eight key triterpenoids detected in the glucose-cultured AC strain from MRM chromatography. Mycelia of solid-state and submerged culture contained similar concentrations of DMMB, with the concentration from submerged-culture AC being marginally larger. However, the concentration of Antcins A, B, and K were magnitudes greater in the solid-state culture sample than in the submerged-culture sample. Of all the key compounds, the Antcin B concentration in the solid-state culture was by far the highest at 3.58 ± 0.19 µg/g, followed by Antcin C at 1.09 ± 0.01 µg/g.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Culture Method

When comparing the two culture methods, in concurrence with the existing literature, mycelia yield was lower in the solid-state culture than the submerged culture (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) [

22,

23]. This is theorised to be due to increased aeration in the liquid culture as it is continuously stirred, dispersing oxygen throughout the mixture, a critical factor affecting protein production of basidiomycete fungi such as

A. cinnamomea[

24,

25,

26].

Contrastingly, it was also observed that the increase in mycelial dry weight from submerged culture was proportionate to the decrease in triterpenoid content—an approximately 10-fold difference (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). In a review on solid-state culture, Barrios-González and Tarragó-Castellanos[

27] suggested that increased secondary metabolite production in solid-state culture compared to submerged culture is due to three main factors: direct air contact, stimulation from the supporting substrate, and water availability. This theory was formulated from the observations of Ávila et al.[

28], who examined the effect of these factors on lovastatin production of

Aspergillus terreus. Periodic submergence of solid-state culture in liquid at timer intervals of 12 hours induced greater lovastatin production than more frequent submergence, while inoculated polyurethane bands within a submerged culture resulted in greater lovastatin production compared with a standard free-floating submerged culture. Additionally, solid culture petri dishes covered with a polyethersulfone membrane (to prevent water loss) produced higher concentrations of lovastatin compared to those with no membrane. The presence of a solid substrate for hyphae to anchor to and provide structure, as well as contact with the air, may therefore induce greater triterpenoid production in

A. cinnamomea cultured with solid-state culture over submerged culture.

Furthermore, secondary metabolite production is usually initiated during the secondary growth stage (idiophase)—rather than the growth phase (trophophase)—which is usually initiated by the depletion of nutrients[

29]. The concentration gradients present in solid culture also facilitate this. Nutrients must be taken up and transported from the penetrative hyphae on the inner layer of the solid substrate to the aerial hyphae on the outer layer of the mycelium via diffusion in the cytoplasm[

30]. This process is slower than direct uptake from the nutrient solution the mycelia are suspended in when grown with submerged culture. As a result, mycelia in submerged culture are saturated with nutrients, and so do not enter idiophase until the sugar concentration in the entire solution is reduced, whereas there is a constant nutritional gradient between the outermost and innermost hyphae in solid culture, inducing the synthesis of secondary metabolites[

31].

Studies investigating

A. cinnamomea cultivation report a wide variety of triterpenoid profiles for different cultivation techniques. Qiao et al.[

32] found that

A. cinnamomea samples grown with solid-state culture on petri dishes contained antcin A, antcin B, antcin C, antcin H, antcin K, DEA, and DSA, but that none of these triterpenoids were detected in samples from submerged culture. Conversely, Chang et al.[

33] did not detect antcin C, antcin B, antcin H, and antcin K in any mycelia—either wild harvested or grown from liquid or solid culture. However, DEA and DSA were detected in mycelia from all sources. Similar differences in the triterpenoid profiles of the AC strain cultivated with the two methods were observed in this study (

Table 2). In the solid-state culture, five of the eight key triterpenoids (antcin A, antcin B, antcin C, antcin K, and DMMB) were detected, whereas only four were detected in the submerged culture (antcin A, antcin B, antcin K, and DMMB).

Despite this, many studies have demonstrated that

A. cinnamomea submerged culture extracts exhibit a variety of therapeutic effects that are beneficial to humans[

34].

A. cinnamomea production in submerged culture usually takes around 14 days[

35], whereas solid-state dish cultures require anywhere from six weeks[

8,

10,

36], to three months[

37]. The use of repeated batch fermentation—when a portion of one culture is used to inoculate future batches—also has the potential to improve commercial cultivation, allowing for continuous cultivation and peak triterpenoid content observed after only seven days[

35]. Moreover, methods of augmenting the triterpenoid content of submerge-cultured

A. cinnamomea through the supplementation of the liquid broth have also been discovered. Beneficial supplements include olive oil[

11], limonene[

3], soybean oil[

4], tangerine oil[

1], chitosan[

38], and alpha-terpineol[

39]. Submerged culture may therefore also be a reliable source of medicinally-valuable

A. cinnamomea, in spite of its low triterpenoid yield as submerged culture has greater scalability compared with solid-state culture in petri dishes as the size of the culture vessel can be increased[

26].

4.2. Effect of Carbohydrate Source

Carbon source also had a significant effect on the growth of

A. cinnamomea. Maltose was the least effective carbohydrate with regards to the accumulation of mycelial biomass in general, while the submerged (

Figure 4) and solid-state (

Figure 5) cultures showed differing results. In the solid culture condition, sucrose resulted the greatest biomass. This is contrary to the existing literature, which shows that glucose stimulates greater increases in

A. cinnamomea biomass than sucrose in solid state culture[

13,

21]. Glucose and sucrose were equally effective at promoting mycelial growth in the submerged culture. However similar studies find that either sucrose[

15,

16] or glucose[

14,

17,

40] result in greater mycelial biomass. Previous research has also noted that other sugars were superior to both glucose and sucrose in increasing

A. cinnamomea growth, including galactose[

13,

21], xylose[

1,

16] and fructose [

17,

40]. As a parasitic fungus,

A. cinnamomea relies on its host tree

C. kanehirae to supply it with carbohydrates, within which sucrose, glucose, and fructose are the most common forms of soluble carbohydrates[

41]. Additionally, the addition of water-soluble wood extracts of

Cinnamomum camphora (a relative of

C. kanehirae) resulted in hyphal growth significantly greater than extracts of

C. kanehirae[

42]. In a subsequent study, analysis of the crude polysaccharide content of this extract of

C. camphora revealed the presence of galactose and glucose, in addition to high concentrations of mannose and galactosamine[

43]. This suggests that these are some of the most abundant carbohydrates available in the natural environment of

A. cinnamomea, and that they are a common energy source for the fungus in the wild. Further investigation into other carbohydrates or carbohydrate combinations that assist in simulating its natural environment may be warranted.

Triterpenoid content was significantly higher when glucose was used as the carbon source in the cultivation media for both solid-state (

Figure 6) and submerged (

Figure 7) culture. This finding is supported by both Chang et al.[

14] and Shu et al.[

1] who found that glucose induced greater triterpenoid production than when cultured with sucrose or xylose respectively. In

A. cinnamomea, triterpenoids are synthesised via the mevalonic pathway, and a number of genes regulating this production have been identified[

44]. The initial reaction in the mevalonic pathway is the generation of acetoacetyl-CoA from acetyl-CoA[

45], with acetyl-CoA itself a product of the decarboxylation of pyruvate, which in turn is generated from glycolysis—the initial substrate of this metabolic pathway being glucose[

46]. An abundance of glucose in the environment may therefore result in increased production of triterpenoid precursors, resulting in the observed increase in triterpenoid content.

4.3. Effect of Phenotype

While the red phenotype of

A. cinnamomea is the most ubiquitous, uncommon phenotypes of different colours exist in the wild and Chinese medicine practitioners claim that these variants—the white variant in particular—are more medicinally potent than its common red-coloured counterpart[

20]. Although the growth of both strains responded similarly to submerged culture (

Figure 5), the W strain accumulated significantly greater mycelial dry weight in solid-state culture across all carbon sources than the AC strain (

Figure 4). Differences in the growth response of different

A. cinnamomea phenotypes to various sugars in solid culture has previously been examined. However, white cinnamomea phenotypes typically have lower growth than red phenotypes [

18,

21], the inverse of what was observed in this study. In addition, Liu[

21] observed that exposure to light during culturing resulted in significantly lower mycelial growth in the AC strain, while growth significantly increased for the W strain. Chen et al.[

20] observed that exposure to blue light was able to induce a whitening effect in a red

A. cinnamomea strain, and that the growth of the fungus under this treatment was similar to that of a white strain grown in darkness. It was also found that both the white and whitened mycelia grew faster over the first 10 days than the red strain.

The total triterpenoid content of the AC strain was significantly greater at its peak (when glucose was used as the carbohydrate source) in both solid-state and submerged culture than the W strain (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Analysis of both wild grown[

47] and in vitro cultured[

18]

A. cinnamomea have shown lower concentrations of triterpenoids in white strains than red ones, as was observed in this research. While both the AC and W strains responded similarly to the different carbon sources with regards to mycelial growth they responded differently in terms of triterpenoid content, particularly in the solid-state culture (

Figure 6). The use of sucrose as the carbon source resulted in the lowest triterpenoid content in the AC strain, while in the W strain it resulted in the second highest. This suggests that the while the primary metabolism of the strains is similar their secondary metabolism differs. Analysis of the triterpenoid profiles of the two strains provides evidence for this difference. None of the eight key triterpenoids were detected in the W strain, while in the AC strain, five and four were present in the solid-state cultured and submerged cultured fungus respectively (

Table 2).

Differences in the triterpenoid profiles of red and white

A. cinnamomea strains have been previously investigated. Chung et al.[

19] noted that while the phytomic similarity indices of three red

A. cinnamomea strains were similar, the index of a white strain was significantly different. Likewise, Chen et al.[

20] observed that no antcin I was detected in white mycelia before four weeks of growth, while the same was not true for red mycelia. Additionally, the concentrations of some triterpenoids—DSA, eburicoic acid, and DEA—were at some time points greater in the white strain. In contrast, Su et al.[

47] noted that the triterpenoid profiles of red, yellow, and white fruiting bodies were relatively similar and that the relative abundance of metabolites was lower in white basidiomata in general, but that the red and yellow phenotypes had distinct groups of metabolites that were uniquely abundant. The triterpenoid profiles of

A. cinnamomea also appear to vary widely between strains, even among those cultured on the same media, with large differences in the content of fruiting bodies in particular[

32].

The basidiomata and mycelia of

A. cinnamomea possess different triterpenoid profiles, with some compounds only found in the fruiting body [

10,

48]. Antcin K can be used as an indicator of fructification in

A. cinnamomea as it is one of the most abundant triterpenoids present in fruiting bodies[

49], yet is either not present or present at a far lower concentration in mycelia [

32,

33]. Emergence of fruiting bodies documented in solid-state dish culture of red but not white strains, accompanied by a characteristic spike in antcin k concentration[

18]. This increase in concentration was observed even in red mycelia whitened by blue light exposure, suggesting a difference in metabolic response between red and white

A. cinnamomea strains. Induction of fruiting bodies has already been shown to be strain dependent[

10], even so methods of stimulating the production of basidiomata in solid-state culture exist. Mechanical wounding with a cotton swab[

9] and a decrease in the incubation temperature by around 5 °C[

8] induced fruiting body formation in dish cultures. Investigation of the effects of these procedures of white

A. cinnamomea strains may yield different chemical profiles.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the effect of carbon source and culture method on the growth and triterpenoid content of red wild-type and white mutant A. cinnamomea. In general, the results were in line with previous similar studies—solid-state culture yields greater biomass than submerged culture, sucrose and glucose are effective at increasing mycelial biomass, glucose induces the greater triterpenoid synthesis, and the W strain exhibited lower triterpenoid content than the AC strain. However, in contrast with the existing literature, the W strain and the AC strain showed similar yields of mycelia in submerged culture, with the W yielding significantly more in solid-state culture. The key triterpenoid content of both strains was lower than previous research, with no key triterpenoids detected in the W strain. Interestingly, both strains responded similarly to the different sugars in terms of biomass, while their secondary metabolism deviated. This is also evidenced by the fact that none of the key triterpenoids were detected in the W strain spectrophotometrically. Examination of methods of inducing basidiomatal production on the white strain alongside metabolomic and transcriptome analysis may further elucidate how the metabolism of the white strain differs from that of its red counterpart.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, P.L and S.Y.M; methodology, P.L. and S.Y.M.; formal analysis S.Y.M., P.L. and H.R.A.; investigation, S.Y.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.M. and H.R.A.; writing—review and editing, P.L.; supervision, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Kun Cheng Liu for kindly providing both the red and white strains of A. cinnamomea.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shu, C.H.; Wu, H.J.; Ko, Y.H.; Lin, W.H.; Jaiswal, R. Effects of Red Light and Addition of Monoterpenes and Tangerine oil on the Production of Biomass and Triterpenoids of Antrodia cinnamomea in Submerged Cultures. J Taiwan Inst Chem E 2016, 67, 140-147. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.J.S.; Vani, M.G.; Chen, C.Y.; Hsiao, W.W.; Li, J.; Lin, Z.X.; Chu, F.H.; Yen, G.C.; Wang, S.Y. A Mechanistic and Empirical Review of Antcins, A New Class of Phytosterols of Formosan Fungi Origin. J Food Drug Anal 2020, 28, 38-59. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.W.; Lai, Y.T.; Chen, L.T.; Yang, F.C. The Cultivation Strategy of Enhancing Triterpenoid Production in Submerged Cultures of Antrodia cinnamomea by Adding Monoterpenes. J Taiwan Inst Chem E 2016, 58, 210-218. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.-W.; Chiu, M.-Y.; Yang, F.-C. Enhancement of Triterpenoids Formation of Antrodia cinnamomea in thin Stillage-submerged Culture by Shifting the Shaking Rate and Adding Soybean Oil. Asian Journal of Biotechnology and Bioresource Technology 2018, 4, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.T.; Shen, Y.C.; Chang, M.C.; Lu, M.K. Precursor-Feeding Strategy on the Triterpenoid Production and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Antrodia cinnamomea. Process Biochem 2016, 51, 941-949. [CrossRef]

- Tien, A.J.; Chien, C.Y.; Chen, Y.H.; Lin, L.C.; Chien, C.T. Fruiting Bodies of Antrodia cinnamomea and Its Active Triterpenoid, Antcin K, Ameliorates N-Nitrosodiethylamine-Induced Hepatic Inflammation, Fibrosis and Carcinogenesis in Rats. Am J Chinese Med 2017, 45, 173-198. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.S.; Leung, K.S. Quality Evaluation of Mycelial Antrodia camphorata using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Coupled with Diode Array Detector and Mass Spectrometry (DAD-MS). Chin Med 2010, 5, 4. [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.T.; Wang, W.R. Basidiomatal Formation of Antrodia cinnamomea on Artificial Agar Media. Bot Bull Acad Sinica 2005, 46, 151-154.

- Lin, J.-Y.; Wu, T.-z.; Chou, J.-C. In Vitro Induction of Fruiting Body in Antrodia cinnamomea-A Medicinally Important Fungus. Botanical Studies 2006, 47, 267-272.

- Chu, Y.C.; Yang, R.M.; Chang, T.T.; Chou, J.C. Fructification of Antrodia cinnamomea Was Strain Dependent in Malt Extract Media and Involved Specific Gene Expression. J Agr Food Chem 2010, 58, 257-261. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.C.; He, K.Z.; Pu, Q.; Li, J.; Zhao, Z.J. Optimization of Cultivating Conditions for Triterpenoids Production from Antrodia cinnamomea. Indian J Microbiol 2012, 52, 648-653. [CrossRef]

- Moore-Landecker, E. Effects of Medium Composition and Light on Formation of Apothecia and Sclerotia by Pyronema domesticum. Can J Bot 1987, 65, 2276-2279. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-H.; Chen, C.-T.; Chen, H.-C.; Hsu, W.-C.; Lu, M.-K. Sugar Flux in Response to Carbohydrate-Feeding of Cultured Antrodia camphorata, a Recently Described Medicinal Fungus in Taiwan. Journal of Chinese Medicine 2002, 13, 21-31. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.Y.; Lee, C.L.; Pan, T.M. Statistical Optimization of Medium Components for the Production of Antrodia cinnamomea AC0623 in Submerged Cultures. Appl Microbiol Biot 2006, 72, 654-661. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.C.; Huang, H.C.; Yang, M.J. The Influence of Environmental Conditions on the Mycelial Growth of Antrodia cinnamomea in Submerged Cultures. Enzyme Microb Tech 2003, 33, 395-402. [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.S.; Wang, C.C.; Sung, S.C. Cultivating Conditions Influence Lipase Production by the Edible Basidiomycete Antrodia cinnamomea in Submerged Culture. Enzyme Microb Tech 2006, 39, 98-102. [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; He, Z.; Lu, Z.M.; Xu, H.Y.; Xu, G.H.; Shi, J.S.; Xu, Z.H. Antrodia camphorata ATCC 200183 Sporulates Asexually in Submerged Culture. Appl Microbiol Biot 2013, 97, 2851-2858. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-L. Chemical Variation of White Antrodia Cinnamomea from Regular Antrodia Cinnamomea. National Dong Hwa University, Taiwan, 2013.

- Chung, C.H.; Yeh, S.C.; Tseng, H.C.; Siu, M.L.; Lee, K.T. Chemical Quality Evaluation of Antrodia cinnamomea Fruiting Bodies using Phytomics Similarity Index Analysis. J Food Drug Anal 2016, 24, 173-178. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.L.; Ho, Y.P.; Chou, J.C. Phenologic Variation of Major Triterpenoids in Regular and White Antrodia cinnamomea. Botanical Studies 2016, 57. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-C. The Effect of Different Solid Plate Medium Culture on Mycelium Growth and Polysaccharides Content of White Antrodia cinnamomea. National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, Taiwan, 2019.

- Zhang, B.B.; Guan, Y.Y.; Hu, P.F.; Chen, L.; Xu, G.R.; Liu, L.M.; Cheung, P.C.K. Production of Bioactive Metabolites by Submerged Fermentation of the Medicinal Mushroom Antrodia cinnamomea: Recent Advances and Future Development. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2019, 39, 541-554. [CrossRef]

- Fazenda, M.L.; Seviour, R.; McNeil, B.; Harvey, L.M. Submerged Culture Fermentation of “Higher Fungi”: The Macrofungi. Adv Appl Microbiol 2008, 63, 33-+. [CrossRef]

- Stark, B.C.; Dikshit, K.L.; Pagilla, K.R. Recent Advances in Understanding the Structure, Function, and Biotechnological Usefulness of the Hemoglobin from the bacterium Vitreoscilla. Biotechnol Lett 2011, 33, 1705-1714. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.X.; Chen, G.Q. Applications of the VHb Gene for Improved Microbial Fermentation Processes. Method Enzymol 2008, 436, 273-+. [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, P.A.; Seviour, R.J.; Schmid, F. Growth of Filamentous Fungi in Submerged Culture: Problems and Possible Solutions. Crit Rev Biotechnol 2000, 20, 17-48. [CrossRef]

- Barrios-González, J.; Tarragó-Castellanos, M.R. Solid-State Fermentation: Special Physiology of Fungi. Ref Ser Phytochem 2017. [CrossRef]

- Avila, N.; Tarragó-Castellanos, M.R.; Barrios-González, J. Environmental Cues that Induce the Physiology of Solid Medium: a Study on Lovastatin Production by Aspergillus terreus. J Appl Microbiol 2017, 122, 1029-1038. [CrossRef]

- Barrios-González, J. Solid-State Fermentation: Physiology of Solid Medium, Its Molecular Basis and Applications. Process Biochem 2012, 47, 175-185. [CrossRef]

- Rahardjo, Y.S.P.; Tramper, J.; Rinzema, A. Modeling Conversion and Transport Phenomena in Solid-State Fermentation: A Review and Perspectives. Biotechnol Adv 2006, 24, 161-179. [CrossRef]

- Acuña-Argüelles, M.E.; Gutiérrez-Rojas, M.; Viniegra-González, G.; Favela-Torres, E. Production and Properties of Three Pectinolytic Activities Produced by Aspergillus niger in Submerged and Solid-State Fermentation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 1995, 43, 808-814. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Song, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, K.D.; Zhang, Z.X.; Bo, T.; Li, R.Y.; Liang, L.N.; Tzeng, Y.M.; Guo, D.A.; et al. Comprehensive Chemical Analysis of Triterpenoids and Polysaccharides in the Medicinal Mushroom Antrodia cinnamomea. Rsc Adv 2015, 5, 47040-47052. [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.T.; Wang, W.R.; Chou, C.J. Differentiation of Mycelia and Basidiomes of Antrodia cinnamomea using Certain Chemical Components. Taiwan Journal of Forest Science 2011, 26, 125-133.

- Lu, M.C.; El-Shazly, M.; Wu, T.Y.; Du, Y.C.; Chang, T.T.; Chen, C.F.; Hsu, Y.M.; Lai, K.H.; Chiu, C.P.; Chang, F.R.; et al. Recent Research and Development of Antrodia cinnamomea. Pharmacol Therapeut 2013, 139, 124-156. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.X.; Lu, Z.M.; Geng, Y.; Gong, J.S.; Zhang, X.J.; Shi, J.S.; Xu, Z.H.; Ma, Y.H. Efficient Production of Bioactive Metabolites from Antrodia camphorata ATCC 200183 by Asexual Reproduction-Based Repeated Batch Fermentation. Bioresource Technol 2015, 194, 334-343. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.W.; Chen, T.C.; Liu, C.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Shaw, J.F.; Chen, Y.T. Identification and Isolation of an Intermediate Metabolite with Dual Antioxidant and Anti-Proliferative Activity Present in the Fungus Antrodia cinnamomea Cultured on an Alternative Medium with Cinnamomum kanehirai Leaf Extract. Plants-Basel 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.C.; Wu, T.Y.; Hsu, T.H.; Lai, M.N.; Wu, Y.C.; Ng, L.T. Chemical Composition and Chronic Toxicity of Disc-Cultured Antrodia cinnamomea Fruiting Bodies. Toxics 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.J.; Chiang, C.C.; Chiang, B.H. The Elicited Two-Stage Submerged Cultivation of Antrodia cinnamomea for Enhancing Triterpenoids Production and Antitumor Activity. Biochem Eng J 2012, 64, 48-54. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.M.; Geng, Y.; Li, H.X.; Sun, Q.; Shi, J.S.; Xu, Z.H. Alpha-Terpineol Promotes Triterpenoid Production of Antrodia cinnamomea in Submerged Culture. Fems Microbiol Lett 2014, 358, 36-43. [CrossRef]

- Shih, I.L.; Pan, K.; Hsieh, C.Y. Influence of Nutritional Components and Oxygen Supply on the Mycelial Growth and Bioactive Metabolites Production in Submerged Culture of Antrodia cinnamomea. Process Biochem 2006, 41, 1129-1135. [CrossRef]

- Magel, E.; Einig, W.; Hampp, R. Carbohydrates in Trees. In Developments in Crop Science, Gupta, A.K., Kaur, N., Eds.; Elsevier: 2000; Volume 26, pp. 317-336.

- Shen, Y.C.; Chou, C.J.; Wang, Y.H.; Chen, C.F.; Chou, Y.C.; Lu, M.K. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of the Extracts from Mycelia of Antrodia camphorata Cultured with Water-Soluble Fractions from Five Different Cinnamomum Species. Fems Microbiol Lett 2004, 231, 137-143. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, F.L.; Chou, C.J.; Chang, Y.C.; Chang, T.T.; Lu, M.K. Promotion of Hyphal Growth and Underlying Chemical Changes in Antrodia camphorata by Host Factors from Cinnamomum camphora. Int J Food Microbiol 2006, 106, 32-38. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, Y. Transcriptome Profiling of Antrodia cinnamomea Fruiting Bodies Grown on Cinnamomum kanehirae and C. camphora Wood Substrates. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Noushahi, H.A.; Khan, A.H.; Noushahi, U.F.; Hussain, M.; Javed, T.; Zafar, M.; Batool, M.; Ahmed, U.; Liu, K.; Harrison, M.T.; et al. Biosynthetic Pathways of Triterpenoids and Strategies to Improve their Biosynthetic Efficiency. Plant Growth Regul 2022, 97, 439-454. [CrossRef]

- Pietrocola, F.; Galluzzi, L.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Madeo, F.; Kroemer, G. Acetyl Coenzyme A: A Central Metabolite and Second Messenger. Cell Metab 2015, 21, 805-821. [CrossRef]

- Su, C.H.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Chng, J.Y.; Lai, M.N.; Ng, L.T. Metabolomic Profiling of Different Antrodia cinnamomea Phenotypes. J Fungi 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Chien, S.C.; Hsiao, W.W.; Chu, F.H.; Li, W.H.; Lin, C.C.; Shaw, J.F.; Wang, S.Y. Metabolite Profiles for Antrodia cinnamomea Fruiting Bodies Harvested at Different Culture Ages and from Different Wood Substrates. J Agr Food Chem 2011, 59, 7626-7635. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.L.; Chu, Y.L.; Ho, C.T.; Chung, J.G.; Lai, C.I.; Su, Y.C.; Kuo, Y.H.; Sheen, L.Y. Antcin K, an Active Triterpenoid from the Fruiting Bodies of Basswood-Cultivated Antrodia cinnamomea, Inhibits Metastasis via Suppression of Integrin-Mediated Adhesion, Migration, and Invasion in Human Hepatoma Cells. J Agric Food Chem 2015, 63, 4561-4569. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Morphology of 4-week-old AC strain Antrodia cinnamomea solid-state culture on malt extract broth containing 1% (a) glucose, (b) maltose, (c) sucrose.

Figure 1.

Morphology of 4-week-old AC strain Antrodia cinnamomea solid-state culture on malt extract broth containing 1% (a) glucose, (b) maltose, (c) sucrose.

Figure 2.

Morphology of 4-week-old W strain Antrodia cinnamomea solid-state culture on malt extract broth containing 1% (a) glucose, (b) maltose, (c) sucrose.

Figure 2.

Morphology of 4-week-old W strain Antrodia cinnamomea solid-state culture on malt extract broth containing 1% (a) glucose, (b) maltose, (c) sucrose.

Figure 3.

MRM chromatogram of the standard peaks of eight key triterpenoid compounds of Antrodia cinnamomea. (A) Antcin A; (B) Antcin B; (C) Antcin C; (D) Antcin H; (E) Antcin K; (F) Dehydroeburioic acid; (G) Dehydrosulphurenic acid; (H) 2,4-Dimethoxy-6-methylbenzene-1,3-diol.

Figure 3.

MRM chromatogram of the standard peaks of eight key triterpenoid compounds of Antrodia cinnamomea. (A) Antcin A; (B) Antcin B; (C) Antcin C; (D) Antcin H; (E) Antcin K; (F) Dehydroeburioic acid; (G) Dehydrosulphurenic acid; (H) 2,4-Dimethoxy-6-methylbenzene-1,3-diol.

Figure 4.

The effect of carbon source on the biomass of wild-type (AC) and white-mutant (W) Antrodia cinnamomea grown in solid-state culture for one month. Values shown are the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. Letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

The effect of carbon source on the biomass of wild-type (AC) and white-mutant (W) Antrodia cinnamomea grown in solid-state culture for one month. Values shown are the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. Letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

The effect of carbon source on the biomass of wild-type (AC) and white-mutant (W) Antrodia cinnamomea grown in submerged culture for one month. Values shown are the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. Letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

The effect of carbon source on the biomass of wild-type (AC) and white-mutant (W) Antrodia cinnamomea grown in submerged culture for one month. Values shown are the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. Letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

The effect of carbon source on the triterpenoid content of wild-type (AC) and white-mutant (W) Antrodia cinnamomea grown in solid-state culture for one month. Values shown are the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. Letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

The effect of carbon source on the triterpenoid content of wild-type (AC) and white-mutant (W) Antrodia cinnamomea grown in solid-state culture for one month. Values shown are the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. Letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

The effect of carbon source on the triterpenoid content of wild-type (AC) and white-mutant (W) Antrodia cinnamomea grown in submerged culture for one month. Values shown are the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. Letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

The effect of carbon source on the triterpenoid content of wild-type (AC) and white-mutant (W) Antrodia cinnamomea grown in submerged culture for one month. Values shown are the mean ± standard deviation of three replicates. Letters indicate significant difference (p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

MRM chromatogram of eight key triterpenoid compounds of wild-type Antrodia cinnamomea grown in solid-state culture for one month. (A) Antcin A; (B) Antcin B; (C) Antcin C; (D) Antcin H; (E) Antcin K; (F) Dehydroeburioic acid; (G) Dehydrosulphurenic acid; (H) 2,4-Dimethoxy-6-methylbenzene-1,3-diol.

Figure 8.

MRM chromatogram of eight key triterpenoid compounds of wild-type Antrodia cinnamomea grown in solid-state culture for one month. (A) Antcin A; (B) Antcin B; (C) Antcin C; (D) Antcin H; (E) Antcin K; (F) Dehydroeburioic acid; (G) Dehydrosulphurenic acid; (H) 2,4-Dimethoxy-6-methylbenzene-1,3-diol.

Figure 9.

MRM chromatogram of eight key triterpenoid compounds of wild-type Antrodia cinnamomea grown in submerged culture for one month. (A) Antcin A; (B) Antcin B; (C) Antcin C; (D) Antcin H; (E) Antcin K; (F) Dehydroeburioic acid; (G) Dehydrosulphurenic acid; (H) 2,4-Dimethoxy-6-methylbenzene-1,3-diol.

Figure 9.

MRM chromatogram of eight key triterpenoid compounds of wild-type Antrodia cinnamomea grown in submerged culture for one month. (A) Antcin A; (B) Antcin B; (C) Antcin C; (D) Antcin H; (E) Antcin K; (F) Dehydroeburioic acid; (G) Dehydrosulphurenic acid; (H) 2,4-Dimethoxy-6-methylbenzene-1,3-diol.

Table 1.

Multiple Reaction Monitoring conditions of the Mass Spectrometry analysis of eight key triterpenoids of Antrodia cinnamomea.

Table 1.

Multiple Reaction Monitoring conditions of the Mass Spectrometry analysis of eight key triterpenoids of Antrodia cinnamomea.

| Sample |

Selected ion |

Parent ion (m/z) |

Product ion (m/z) |

Collision energy (V) |

Scan time (s) |

| Antcin A |

[M-H]− |

453.4 |

393.7,409.6 |

30 |

0.2 |

| Antcin B |

[M-H]− |

467.5 |

407.6,423.6 |

30 |

0.1 |

| Antcin C |

[M-H]− |

469.5 |

407.6,425.5 |

30 |

0.5 |

| Antcin H |

[M-H]− |

485.4 |

413.4,441.5 |

30 |

0.1 |

| Antcin K |

[M-H]− |

487.4 |

391.7,443.6 |

30 |

0.2 |

| DEA |

[M-H]− |

467.4 |

337.8 |

34 |

0.5 |

| DSA |

[M-H]− |

483.4 |

270.1 |

41 |

0.5 |

| DMMB |

[M+H]+ |

197.0 |

139.0 |

21 |

0.5 |

Table 2.

Concentrations of eight key triterpenoid compounds of wild-type Antrodia cinnamomea grown identified from MRM chromatograms.

Table 2.

Concentrations of eight key triterpenoid compounds of wild-type Antrodia cinnamomea grown identified from MRM chromatograms.

| Culture Method |

Triterpenoid content (µg/g) |

| |

Antcin A |

Antcin B |

Antcin C |

Antcin H |

Antcin K |

DEA |

DSA |

DMMB |

| Solid-State |

0.46 ± 0.01 |

3.58 ± 0.19 |

1.09 ± 0.01 |

- |

0.14 ± 0.01 |

- |

- |

0.21 ± 0.01 |

| Submerged |

0.02 ± 0.01 |

0.03 ± 0.01 |

- |

- |

0.02 ± 0.01 |

- |

- |

0.26 ± 0.01 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).