1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation and integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) represent a paradigm shift across numerous domains, including scientific research, business operations, education, content creation, and daily communication [

1]. These powerful models, exemplified by architectures like GPT-4, Claude, Llama, Mistral and Gemini [

2], demonstrate remarkable capabilities in understanding and generating human-like text, translating languages, summarizing complex information, and even writing creative content and code. Their potential to enhance productivity, accelerate discovery, and democratize access to information is immense, driving their widespread adoption by organizations and individuals globally [

3].

However, this transformative potential is intrinsically linked with significant and multifaceted risks that challenge their safe, ethical, and reliable deployment [

4,

5]. As LLMs become more deeply embedded in critical applications and user interactions, concerns regarding their security vulnerabilities, potential for generating harmful or biased content, propensity for factual inaccuracies (hallucinations), and risks to data privacy have become paramount [

6,

7]. The flexibility and generative power that make LLMs so valuable create attack surfaces and potential failure modes that are different significantly from traditional software systems. Security risks include prompt injection attacks, where malicious inputs can hijack the model's intended function, data poisoning during training, and potential denial-of-service vectors [

7]. Ethical concerns are equally pressing, encompassing the generation and amplification of biased language reflecting societal prejudices (gender, race, etc.), the creation of toxic or hateful content, the spread of misinformation and disinformation at scale, and the potential for manipulative use [

8]. Furthermore, LLMs trained on vast datasets may inadvertently leak sensitive personal identifiable information (PII) or confidential corporate data present in their training corpus or user prompts [

8]. Finally, the inherent nature of current generative models leads to the phenomenon of "hallucinations" – the generation of plausible but factually incorrect or nonsensical statements – undermining their reliability, particularly in knowledge-intensive applications [

9]. The OWASP Top 10 for LLM Applications project (now OWASP Gen AI Security Project) underscores the industry-wide recognition of these critical vulnerabilities [

9]. These challenges are particularly acute in sectors like finance, healthcare, legal services, and public administration, where trust, accuracy, and compliance are non-negotiable [

10].

In response to these challenges, various approaches to LLM safety and content moderation have emerged. Major LLM developers like OpenAI and Anthropic have incorporated safety mechanisms directly into their models and APIs, often through extensive alignment processes like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) and Constitutional AI [

10]. OpenAI offers a Moderation API, while Anthropic's models are designed with inherent safety principles [

11]. While valuable, relying solely on this built-in alignment presents limitations. These internal safety layers can sometimes be overly restrictive, leading to refusals to answer legitimate queries or exhibiting a form of "over-censorship" that hinders utility [

11]. Furthermore, their specific alignment targets and policies are often opaque ("black box") and may not be sufficiently customizable to meet the diverse requirements of specific applications, industries, or international regulatory landscapes (e.g., General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), EU AI Act), which creates a dependency on the provider's specific safety philosophy and implementation [

12].

The research community and specialized companies are actively developing alternative and supplementary safety solutions. Platforms and tools from companies like Turing, Lasso Security, Protect AI, Granica AI, PromptArmor, Enkrypt AI, Fairly AI and Holistic AI address various facets of AI security, governance, and risk management [

13]. Approaches include specialized security layers, prompt injection defense data privacy techniques, vulnerability assessment and comprehensive governance frameworks. Google's Perspective API targets toxicity detection while open-source projects and academic research explore filter models, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) for grounding, and hallucination/bias detection methods [

14]. However, many external solutions focus on specific threat vectors, may introduce significant performance overhead, or lack seamless integration capabilities. The need for effective multilingual moderation further complicates the landscape for global applications.

This landscape reveals a critical need for a comprehensive, adaptable, and easily integrable framework that allows organizations to implement fine-grained control over LLM interactions. There is a gap for solutions that can provide robust safety and ethical alignment without solely relying on the inherent, often inflexible, safety layers of the base LLM. Such a solution should empower users to leverage a wider range of LLMs, including potentially less restricted open-source models, while maintaining control over the interaction's safety profile. Furthermore, an ideal system should move beyond purely reactive filtering ("Negative Filtering") to proactively enhance the quality and safety of LLM outputs ("Positive Filtering"), for instance, by grounding responses in trusted information sources. Diverging hypotheses exist regarding the optimal locus of control – internal model alignment versus external validation layers.

This paper introduces the AVI (Aligned Validation Interface), an intelligent filter system designed to bridge this gap. AVI functions as a modular Application Programming Interface (API) Gateway positioned between user applications and LLMs, providing a centralized point for monitoring, validating, and aligning LLM interactions according to configurable policies. Its core architectural principle enables universality, making it largely independent of the specific underlying LLM being used and offering potential extensibility to various data types beyond text in the future. We propose that AVI's "Compound AI" approach, orchestrating specialized validation and enhancement modules, offers significant advantages. This modularity allows for reduced dependency on the base LLM's built-in alignment, enabling users to tailor safety and ethical constraints externally. Crucially, AVI is designed for bidirectional positive/negative filtering: it not only detects and mitigates risks in both user inputs and LLM outputs (Negative Filtering via validation modules) but also proactively improves response quality, factual accuracy, and safety by injecting verified context through its RAG-based Contextualization Engine (Positive Filtering).

The central hypothesis tested in this work is that the AVI framework can effectively mitigate a broad spectrum of LLM-associated risks (including prompt injection, toxic content, PII leakage, and hallucinations) across diverse LLMs, while offering superior flexibility and control compared to relying solely on built-in model safety features, and imposing acceptable performance overhead. The main aim of this work is to present the conceptual architecture and methodology of AVI and to evaluate its feasibility and effectiveness through a Proof-of-Concept (PoC) implementation. We detail the design of the core AVI modules (Input/Output Validation, Response Assessment, Contextualization Engine) and their orchestration. We introduce a mathematical model and metrics for evaluation. Finally, we present preliminary results from our PoC evaluation, demonstrating AVI's potential to enhance the safety, reliability, and ethical alignment of LLM interactions. This work contributes a practical and adaptable architectural pattern for governing LLM usage, aiming to make LLMs more trustworthy and applicable in critical domains like finance, healthcare, education, and enterprise applications, thereby fostering responsible AI adoption. The described principles are intended to be comprehensible to a broad audience of scientists and engineers working with applied AI.

So, this paper addresses the identified research gap and proposes a new technology solution, the Agreed Verification Interface (AVI), which is a composite AI framework that acts as an intelligent API gateway to manage interactions between LLMs and end users. AVI introduces a dual-pronged approach: (1) negative filtering to detect and block malicious, biased, or privacy-infringing content in both input and output; and (2) positive filtering to enhance factual and contextual relevance using RAG-based reasoning. The interface’s modular design supports data input validation, result output evaluation, hallucination detection, and context injection, all managed through an industry, government, or enterprise policy-driven orchestration layer. Unlike black-box model alignments or fragmented security add-ons, AVI is configurable, highly scalable, and independent of the underlying LLM, allowing for flexibility and integration across a wide range of applications and compliance settings [

15]. By combining rule-based systems, machine-learning classifiers, named entity recognition, and semantic similarity techniques, AVI enables organizations to dynamically monitor, validate, and adjust LLM responses. Preliminary evaluation of the proof-of-concept system has shown promising results in reducing operative injection success rates, reducing toxicity, accurately identifying PII, and increasing actual accuracy—all while maintaining acceptable latency. As such, AVI represents a significant step toward implementing responsible AI principles in real-world LLM deployments.

2. Literature Review

The rapid development and widespread adoption of large language models (LLMs)—including GPT-4, Claude, and LLaMA—have profoundly influenced many of the world’s leading industries, particularly those in the service sector [

16]. These models offer powerful capabilities for natural language generation, product and technology design, and the identification of inefficiencies within management process chains. LLMs now serve as foundational technologies in domains such as healthcare, finance, legal services, customer support, and education [

17]. They can generate answers to user queries, synthesize and transform information into structured knowledge, translate languages, and perform complex reasoning tasks.

Despite their transformative potential, the rise of LLMs has elicited serious concerns among users and developers, particularly in relation to security, bias, factual reliability, privacy, and compliance with data protection regulations—especially when these models are applied in high-risk or mission-critical business environments [

18]. Key risks include prompt injection attacks, the generation of toxic or biased content, hallucinations (i.e., plausible but incorrect outputs), and the unintended leakage of personally identifiable information (PII) [

19,

20]. These vulnerabilities pose significant dangers when LLMs are integrated into sensitive applications that demand high levels of trust, reliability, and ethical governance.

Applications in such contexts require both flexibility and rigorous risk management strategies. To address these challenges, leading LLM developers have embedded internal security mechanisms. For instance, OpenAI has employed Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) and moderation APIs to align model behavior with governmental and industry-specific security standards. Similarly, Anthropic’s Constitutional AI approach incorporates rule-based constraints to guide model behavior [

21,

22].

However, these existing mechanisms exhibit notable limitations. First, the alignment layers in commercial models are often opaque, making them difficult to audit and insufficiently adaptable across different domains or regulatory regimes. Second, they may impose excessive censorship or restrictive controls, leading to the rejection of benign user queries and a degradation of user experience [

23]. Third, many organizations opt to implement open-source or third-party models to reduce technological and operational costs, which often results in inadequate built-in security features.

Given these limitations, relying solely on internal alignment mechanisms is insufficient, particularly in sectors governed by strict privacy laws, compliance mandates, and cultural norms. In response, external security tools and middleware frameworks have emerged to supplement or replace internal safeguards. For example, tools such as PromptArmor, Holistic AI, and Google’s Perspective API provide targeted protections against prompt injections, bias, and toxic outputs [

24,

25]. Concurrently, academic research is exploring frameworks for hallucination detection, automated ethical filtering, and AI governance auditing [

26,

27,

28].

While these initiatives are valuable and address key components of LLM security, they often focus on isolated threats and lack holistic orchestration across the end-to-end model interaction pipeline. Furthermore, they are frequently ill equipped to address dynamic and unpredictable external risks. Thus, an integrative, modular approach is required to ensure more comprehensive and adaptable governance of LLM-based systems.

There is growing interest in the use of augmented search generation (RAG) to ground model outputs in validated, demand-based knowledge [

29]. RAG has potential benefits not only in reducing hallucinations but also in aligning credible responses with domain-specific context. However, few systems seamlessly integrate RAG into a modular security architecture capable of real-time filtering, assessing possible (predictable or undetectable) risks, and enhancing the context of outputs.

Microsoft has developed a standard for responsible AI. It is a framework for building AI systems according to six principles: fairness, trustworthiness and safety, privacy, and protection (

Table 1).

Neural networks operate on a probabilistic basis, so their answers are not always accurate. For example, AI can generate incorrect code but evaluate it as correct (hyper confidence effect). However, such errors are also common to humans, and AI trained on large data sets is more likely to imitate the work of an experienced developer than an unexperienced one. The software development lifecycle (SDLC) involves various risks at each stage when incorporating AI technologies. During maintenance and operation, AI systems may produce hallucinations—plausible but incorrect information—and can be vulnerable to manipulation by malicious users, such as through SQL injection attacks. In the deployment phase, generative AI models require high computational resources, potentially leading to excessive costs, and AI-generated configurations may degrade performance or introduce system vulnerabilities. Implementation risks include insecure code produced by AI developer assistants and flawed AI-generated tests that may reinforce incorrect behavior [

31]. To mitigate these risks, the SDLC is typically divided into key phases: requirements analysis, architecture design, development, testing, and maintenance. Each phase must consider specific AI-related challenges such as data specificity, adaptability to model changes, code security, and non-functional testing aspects like robustness against attacks. Increasingly, the analysis and design stages are merging, with developers directly collaborating with business stakeholders to define and refine system requirements—a practice common in both startups and major firms. Internal engineering platforms now handle many architectural constraints, adding flexibility to the design process [

32]. Historically, roles like business analyst and developer were separated due to the high cost of programmer labor, but agile methods and faster development cycles have shown that excessive role separation can hinder progress [

33]. AI is further reshaping these dynamics, as generative models can write substantial code segments, though they require carefully crafted prompts to yield reliable results. It represents one of the key AI-specific risks at the requirements analysis and system design stages.

Additionally, AI has limited contextual understanding of user prompts. While developers rely not only on formal specifications but also on implicit knowledge about the project to make informed decisions, language models operate solely based on the explicit information contained in the prompt. Furthermore, the process is affected by context length limitations—modern models can handle tens of thousands of tokens, but even this may be insufficient for complex tasks. As a result, generative AI currently serves more as an auxiliary tool rather than an autonomous participant in the design process.

For example, the rapid rise in popularity of ChatGPT is not just a result of marketing efforts, but also reflects a genuine technological breakthrough in the development of generative neural networks [

34]. Over the past two and a half years, model quality has significantly improved due to larger training datasets and extended pre-training periods. However, this stage of technological evolution is nearing completion and is now being complemented by a new direction: enhancing output quality by increasing computational resources allocated per individual response. These are known as "reasoning models," which are capable of more advanced logical reasoning. In parallel, ongoing efforts are being made to implement incremental algorithmic improvements that steadily enhance the accuracy and reliability of language models.

To effectively manage AI-specific risks in software development and application, it is essential first to have the ability to manage IT risks more broadly. Many of the current challenges associated with AI may evolve over time as the technologies continue to advance. However, the example and methodology presented in this article offer a systematic approach that can help tailor risk management strategies to real-world business needs [

35,

36]. Each company has its own level of maturity in working with AI, and understanding this factor is becoming a critical component of a successful AI adoption strategy.

3. Materials and Methods

This study introduces and evaluates the Aligned Validation Interface (AVI), a conceptual framework designed to enhance the safety, reliability, and ethical alignment of interactions with Large Language Models (LLMs). The AVI system operates as an intelligent API Gateway, intercepting communication between user applications and downstream LLMs to apply configurable validation and modification policies. This architecture ensures LLM agnosticism and facilitates centralized control and monitoring. Underlying AVI is a Compound AI approach, orchestrating multiple specialized modules rather than relying on a single monolithic safety model. This modular design enhances flexibility and allows for the integration of diverse validation techniques. The primary goal of AVI is to enable safer, more reliable, and ethically aligned interactions by proactively validating and modifying the communication flow based on configurable policies, offering an alternative or supplement to relying solely on the often opaque and inflexible internal safety mechanisms built into many proprietary LLMs [

37,

38]. AVI aims to provide organizations with granular control over LLM interactions, adaptability to specific operational contexts and regulatory requirements (e.g., GDPR, EU AI Act [

39]), and compatibility with a diverse ecosystem of LLMs, thereby promoting responsible AI innovation and deployment across critical sectors such as finance, healthcare, and education [

40].

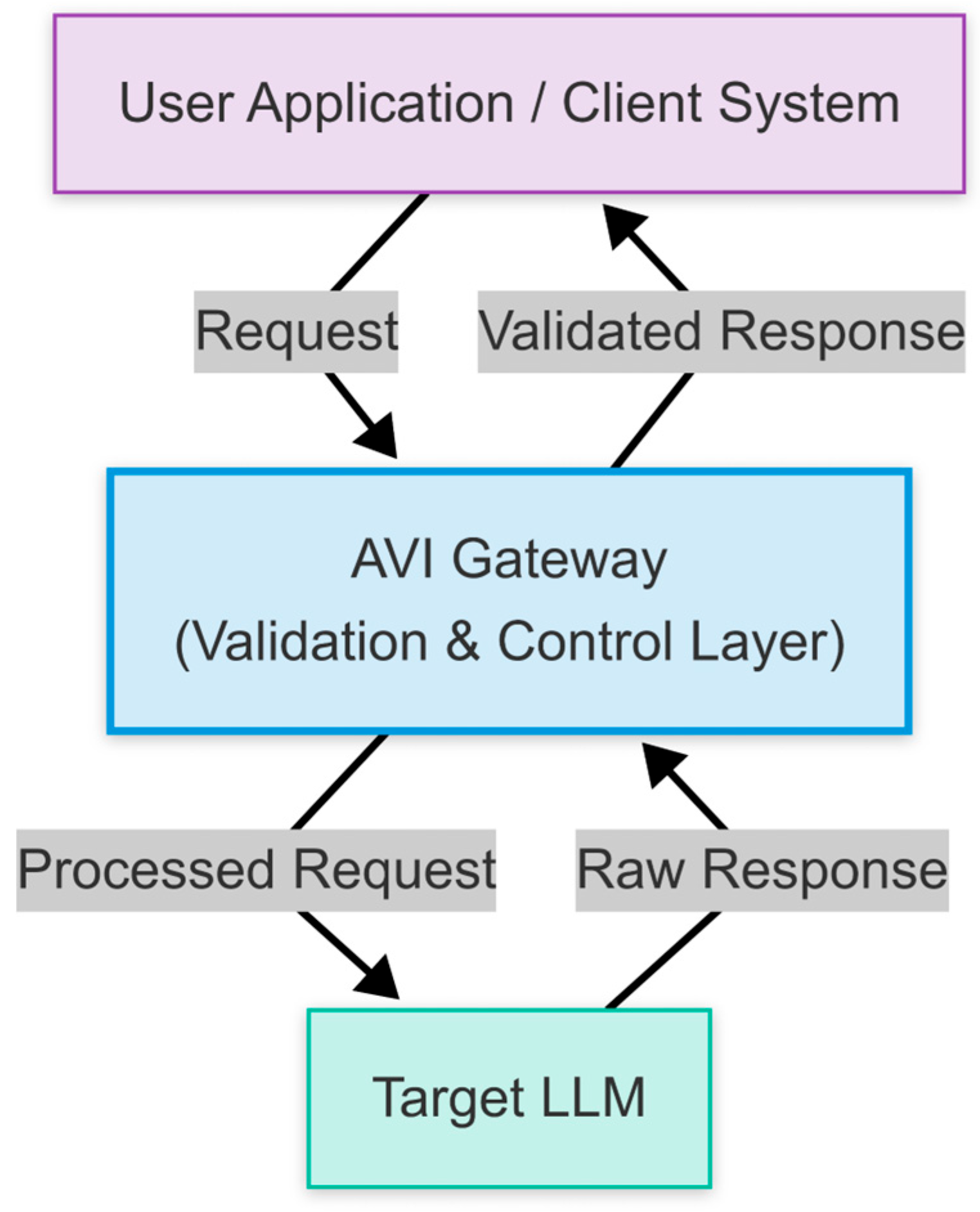

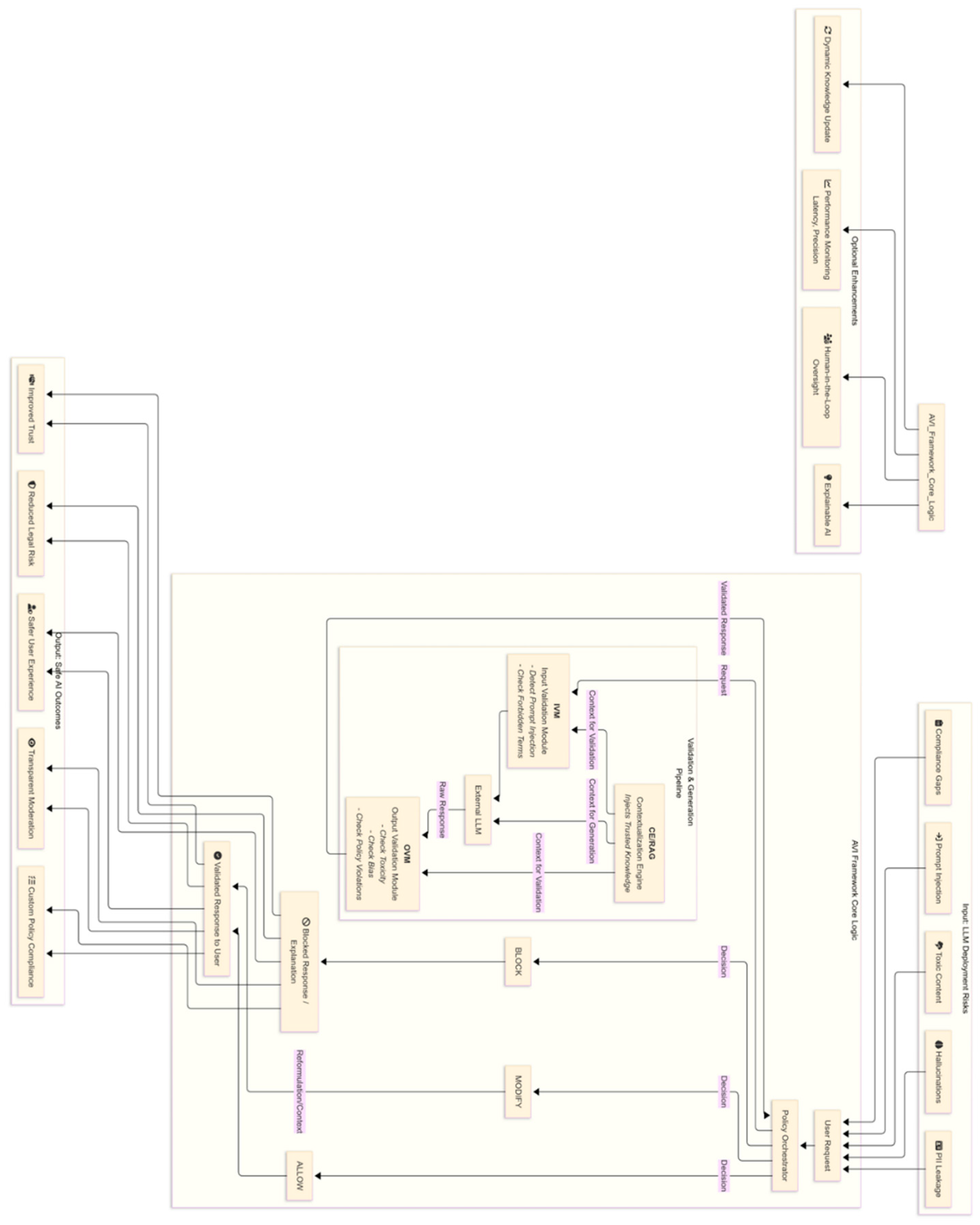

Figure 1.

High-level diagram of AVI as an API Gateway. Source: made by authors.

Figure 1.

High-level diagram of AVI as an API Gateway. Source: made by authors.

Architecturally, AVI functions as an API Gateway, positioning it as a mandatory checkpoint. The typical data processing sequence involves: 1) Receiving an incoming request. 2) Pre-processing and input validation via the Input Validation Module (IVM). 3) Optional context retrieval and augmentation via the Contextualization Engine (CE/RAG). 4) Forwarding the processed request to the designated LLM. 5) Intercepting the LLM's response. 6) Post-processing, assessment, and validation of the response via the Response Assessment Module (RAM) and Output Validation Module (OVM). 7) Delivering the final, validated response. This gateway architecture provides LLM agnosticism, centralized policy enforcement, simplified application integration, and comprehensive logging capabilities. The Compound AI philosophy underpins this, utilizing an ensemble of specialized modules for distinct validation and enhancement tasks, promoting flexibility, maintainability, and the integration of diverse techniques (rule-based, ML-based, heuristic) [

41].

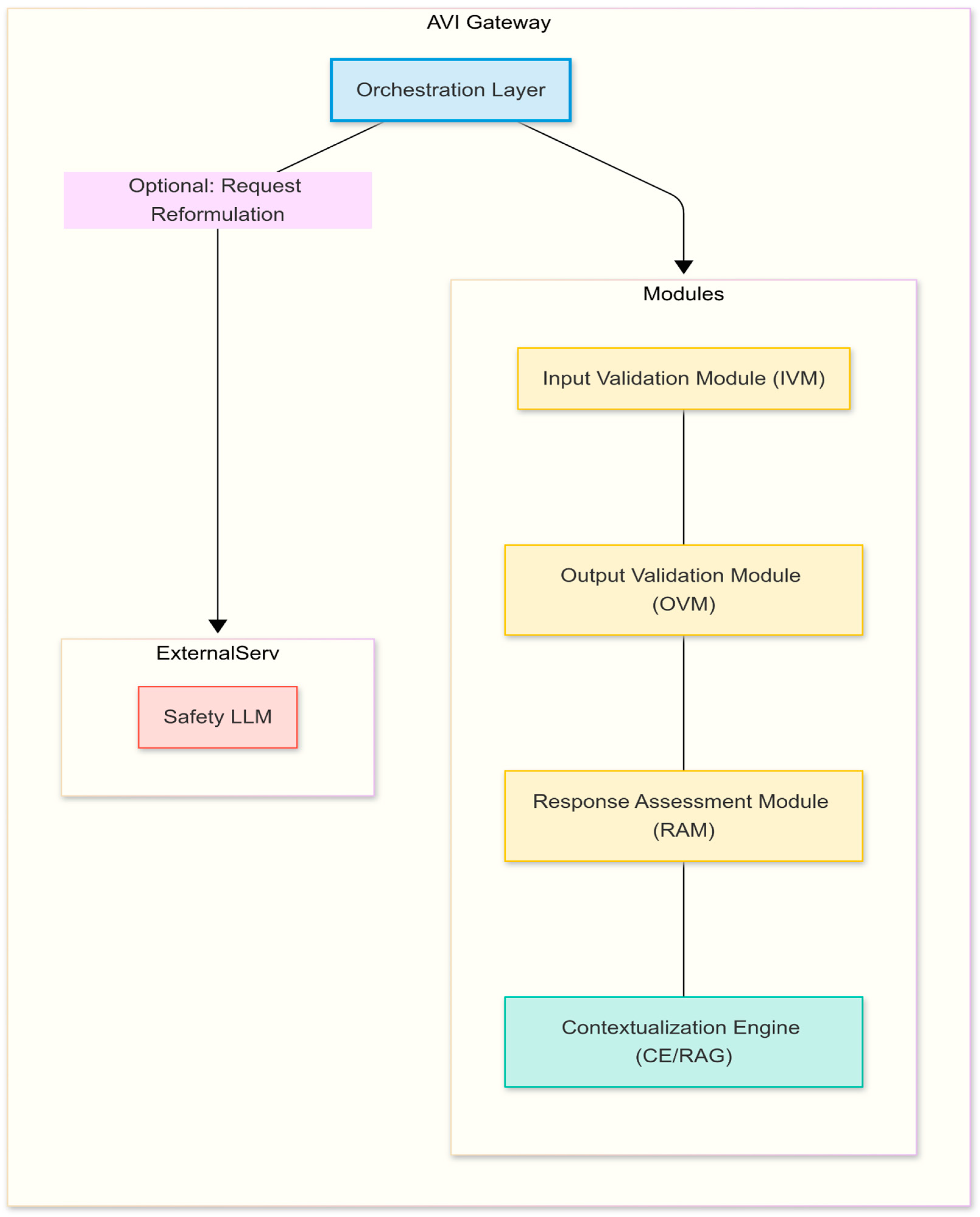

Figure 2.

Diagram illustrating the Compound AI concept. Source: made by authors.

Figure 2.

Diagram illustrating the Compound AI concept. Source: made by authors.

The core modules within the AVI framework are designed as follows: The

Input Validation Module (IVM) analyzes incoming requests for security threats (e.g., prompt injection), PII, and policy violations (e.g., forbidden topics). Conceptually, it combines rule-based systems (regex, dictionaries), ML classifiers (e.g., fine-tuned models based on architectures like Llama 3, Mistral, or DeBERTa V3 for semantic threat analysis), and NER models (e.g., spaCy-based [ ] or transformer-based) for PII detection [

42]. The

Output Validation Module (OVM) scrutinizes the LLM's generated response for harmful content (toxicity, hate speech), potential biases, PII leakage, and policy compliance, using similar validation techniques tailored for generated text. The

Response Assessment Module (RAM) evaluates the response quality, focusing on factual accuracy (hallucination detection) and relevance. Methodologies include NLI models [

43] or semantic similarity (e.g., SBERT [

44]) for checking consistency with RAG context, internal consistency analysis, and potentially LLM self-critique mechanisms using CoT prompting [

45].

The Contextualization Engine (CE/RAG) enables "Positive Filtering" by retrieving relevant, trusted information to ground the LLM's response. It utilizes text embedding models (e.g., sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2 [

46] as used in the PoC) and a vector database (e.g., ChromaDB [

47] as used in the PoC) with k-NN search. AVI's CE supports both explicit rule-document links (for curated context based on triggered rules) and implicit query-based similarity search against a general knowledge base. An

Orchestration Layer manages this workflow, implementing a multi-stage "traffic light" decision logic. Based on validation outputs from IVM, RAM, and OVM against configured policies, it determines the final action: ALLOW (pass through), BLOCK (reject request/response), MODIFY_RAG (add context before LLM call), or MODIFY_LLM (request reformulation by a Safety LLM).

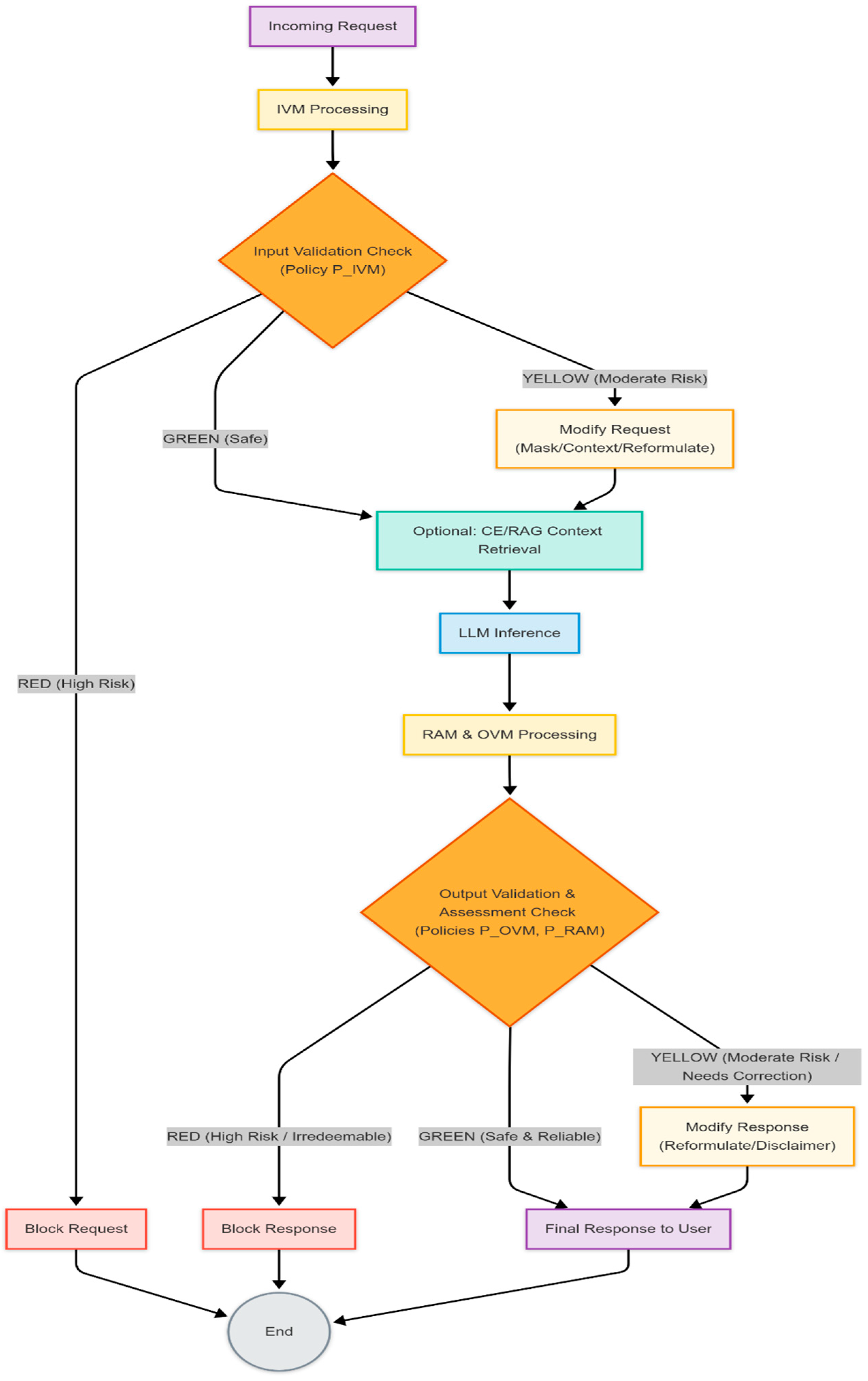

Figure 3.

Flowchart diagram illustrating the orchestration logic ("traffic light"). Source: made by authors.

Figure 3.

Flowchart diagram illustrating the orchestration logic ("traffic light"). Source: made by authors.

AVI's adaptability relies on its configurable Policy Management Framework. Policies define the rules (keywords, regex, semantic similarity, classifier outputs), sensitivity thresholds, and corresponding actions (block, mask, log, reformulate, add context) for each module. While the PoC utilized CSV files for simplicity, the framework conceptually supports more robust formats (JSON, YAML, databases) suitable for complex, potentially hierarchical or context-dependent policies [

47]. Critically, the dynamic nature of LLM risks and information necessitates continuous policy maintenance. Effective deployment requires human oversight and curation by a dedicated team or individual responsible for monitoring emerging threats (e.g., new prompt injection techniques), adapting ethical rules to evolving norms, maintaining the factual grounding knowledge base for RAG, analyzing system logs for refinement, and managing rule-context links. This human-in-the-loop approach ensures the long-term relevance and effectiveness of the AVI system.

Evaluation of AVI employs a combination of performance and quality metrics.

Performance Metrics include Latency (additional processing time introduced by AVI:

and Throughput (requests per second, RPS).

Validation Quality Metrics for classification tasks (toxicity, PII, attacks) utilize the Confusion Matrix (TP, TN, FP, FN) to calculate Accuracy:

ROC curves and AUC may also be used.

Response Assessment Quality Metrics include Hallucination Detection Accuracy:

and potentially Faithfulness Metrics (e.g., NLI scores assessing adherence to RAG context).

RAG Quality Metrics include Context Relevance (average query-document similarity) and Context Recall (proportion of relevant documents retrieved). Conceptually, the

AVI Decision Process can be modeled as a sequence of transformations and decisions based on the outputs of its core modules. Let R be the input request:

be the set of active policies governing the modules and actions, C the retrieved context (if any), Resp_LLM the raw response from the downstream LLM, and Resp_Final the final output delivered to the user. The process unfolds through the following key steps:

- 1.

Input Validation Score (Score_IVM): The IVM module assesses the input request R against input policies P_IVM. This assessment yields a risk score, Score_IVM ∈ [0, 1], where 0 represents a safe input and 1 represents a high-risk input (e.g., detected high-severity prompt injection or forbidden content). This score can be derived from the maximum confidence score of triggered classifiers or the highest risk level of matched rules. The module may also produce a modified request R'.

- 2.

Context Retrieval (Context): If RAG is enabled (P_CE) and potentially triggered by R or Score_IVM, the CE module retrieves context C:

- 3.

LLM Interaction: The base LLM generates a response.

- 4.

Response Quality Scores (Scores_RAM): The RAM module assesses the raw response Resp_LLM potentially using context C and policies P_RAM. This yields multiple quality scores, for example: Hallucination_Prob ∈ [0, 1]: Probability of the response containing factual inaccuracies. Faithfulness_Score ∈ [0, 1]: Degree to which the response adheres to the provided context C (if applicable), where 1 is fully faithful. Relevance_Score ∈ [0, 1]: Relevance of the response to the initial request R:

- 5.

Output Validation Score (Score_OVM): The OVM assesses Resp_LLM against output policies P_OVM, yielding an output risk score, Score_OVM ∈ [0, 1], similar to Score_IVM (e.g., based on toxicity, PII detection, forbidden content). It may also produce a potentially modified response Resp':

- 6.

Risk Aggregation (Risk_Agg): The individual risk and quality scores are aggregated into a single metric or vector representing the overall risk profile of the interaction. A simple aggregation function could be a weighted sum, where weights (w_i) are defined in P_Action:

More complex aggregation functions could use maximums, logical rules, or even a small meta-classifier trained on these scores. The specific weights or rules allow tuning the system's sensitivity to different types of risks.

- 7.

Final Action Decision (Action, Resp_Final): Based on the aggregated risk Risk_Agg and potentially the individual scores, the final action Action and final response Resp_Final are determined according to action policies P_Action. These policies define specific thresholds, Thresh_Modify and Thresh_Block, which delineate the boundaries for different actions. The final action Action is determined by comparing the aggregated risk against these thresholds:

Subsequently, the final response Resp_Final delivered to the user is determined based on the selected Action:

ALLOW permits the (potentially OVM-modified) response Resp' to pass through to the user. MODIFY_LLM triggers a reformulation attempt, potentially invoking a separate, highly aligned "Safety LLM" which uses the original response Resp' and assessment scores Scores_RAM as input, guided by specific instructions in P_Action. BLOCK prevents the response from reaching the user, returning a predefined message indicating the reason for blockage. The specific thresholds (Thresh_Modify, Thresh_Block) and the implementation details of the modification strategy (SafetyLLM function) are crucial configurable elements within the action policy P_Action. This formal model provides a structured representation of the multi-stage validation and decision-making process inherent to the AVI framework.

To validate this framework, a Proof-of-Concept (PoC) system was implemented as an independent academic research effort. The PoC utilized Python (version 3.10), FastAPI (version 0.110.0) for the API and orchestration, ChromaDB (version 0.4.22) for vector storage, the Sentence-Transformers library (version 2.5.1) with the all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model for text embeddings, Pandas (version 2.2.0) for data handling, and Scikit-learn (version 1.4.0) for metric calculations. The primary LLM for testing was Grok-2-1212, accessed via its public API, chosen for its availability and characteristics suitable for observing the filter's impact [

48,

49,

50]. Development and testing were conducted on a standard desktop computer (Apple M1 Pro chip with 10-core CPU, 16-core GPU, and 16 GB Unified Memory) without dedicated GPU acceleration, focusing on architectural validation over performance optimization. The source code for this specific PoC implementation is maintained privately.

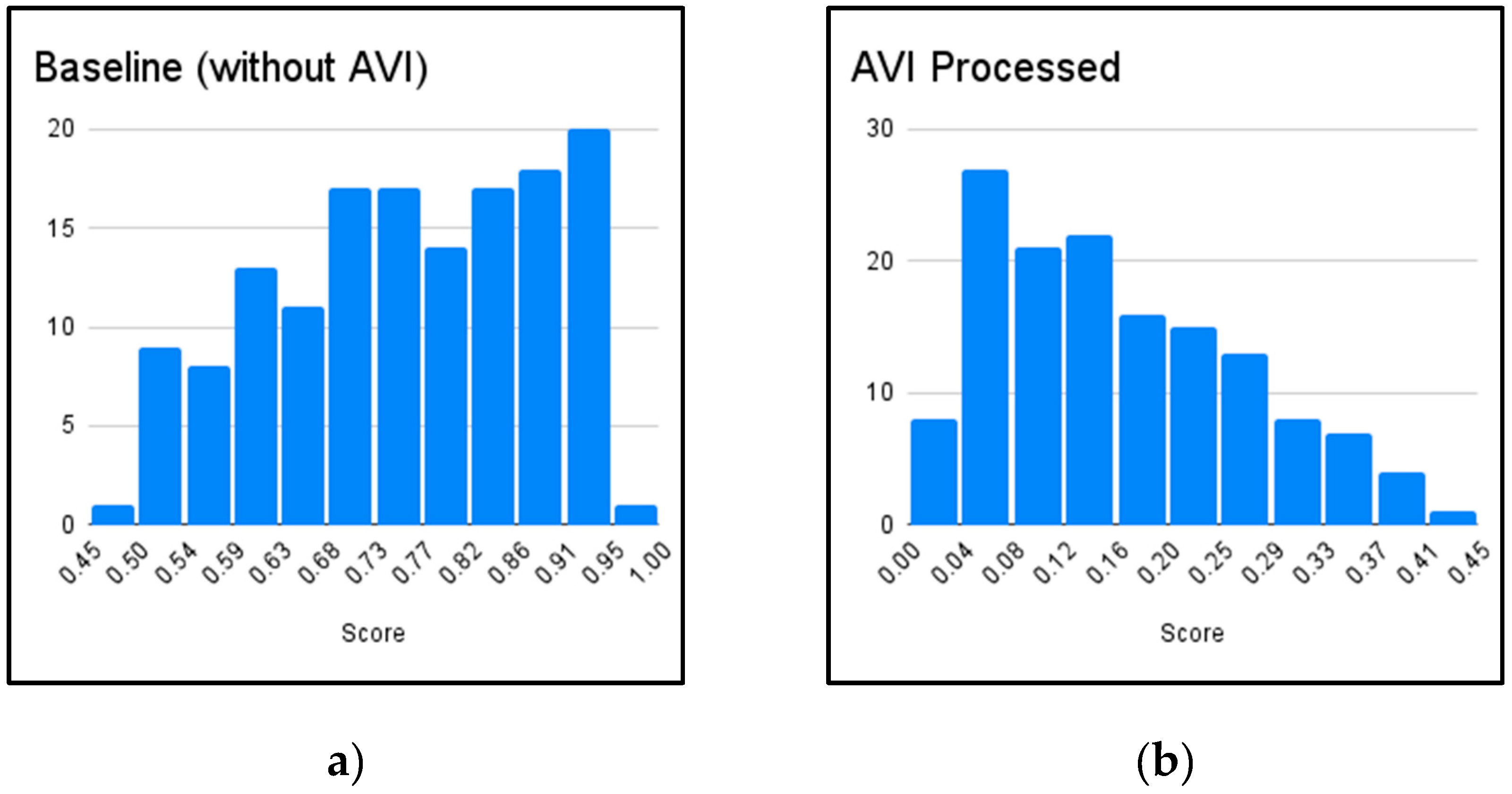

The PoC was evaluated through a series of experiments. Input Validation against prompt injection used 95 attacks from the AdvBench benchmark [

51]. The reduction in Attack Success Rate (ASR) compared to a baseline (estimated at Value: ~78%) was measured. Output Validation for toxicity used 150 prompts from RealToxicityPrompts [

52]; responses generated with and without AVI processing were scored using the Perspective API, and average toxicity reduction was calculated. PII Validation employed a synthetic dataset of 70 sentences to evaluate detection and masking performance using Precision, Recall, and F1-score. RAG Evaluation was performed qualitatively using 6 rule-document pairs from the PoC's data, comparing responses generated with and without RAG context for improvements in neutrality and factual grounding. A simplified Hallucination Detection mechanism (based on keyword matching against a predefined set of factual assertions relevant to the PoC's limited knowledge base) was tested on 20 factual questions, measuring its accuracy in flagging incorrect LLM responses. Performance Evaluation measured the average latency overhead introduced by AVI across 50 queries in different modes (with/without RAG). Data analysis involved calculating standard metrics using Scikit-learn and performing qualitative assessments of RAG outputs.

5. Discussion

This study addresses the issue of high-quality design and implementation of filter interfaces in artificial intelligence to reduce the risks of outputting low quality or erroneous data. The paper presents a Proof-of-Concept (PoC) experiment evaluating the Aligned Validation Interface (AVI), which demonstrates significant effectiveness of the filter in mitigating critical risks of using large language models (LLM). In particular, AVI reduced the injection success rate by 82%, reduced the average toxicity of output by 75%, and achieved high accuracy in detecting personally identifiable information (PII) with an F1 score of approximately 0.95. In addition, a qualitative evaluation of the RAG-based contextualization engine showed improvements in neutrality, factual accuracy, and ethical consistency of the model output in the given parameters and context, while a simplified hallucination detection module flagged 75% of incorrect answers in supervised tests. Despite introducing moderate latency—an average of 85 ms without RAG and 450 ms with RAG—the system demonstrated the ability to maintain acceptable performance for real-time applications. These results validate the ability of AVI to improve the security of linguistic models, reliability, and compliance with regulatory (government, industry, or enterprise) requirements of generative AI deployments in critical domains such as healthcare, finance, and education [

56]. Since deploying large language models (LLMs) in real-world business and technology environments raises critical concerns regarding data security, privacy, and ethical compliance, in this study the authors presented the Agreement Validation Interface (AVI), a modular API gateway that serves as a policy enforcement broker between LLMs and user applications. The design and proof-of-concept evaluation of AVI provides strong initial evidence that combining bidirectional filtering with contextual enhancement can significantly reduce common LLM risks, including flash injection, output toxicity, hallucinations, and personally identifiable information (PII) leakage [

57,

58].

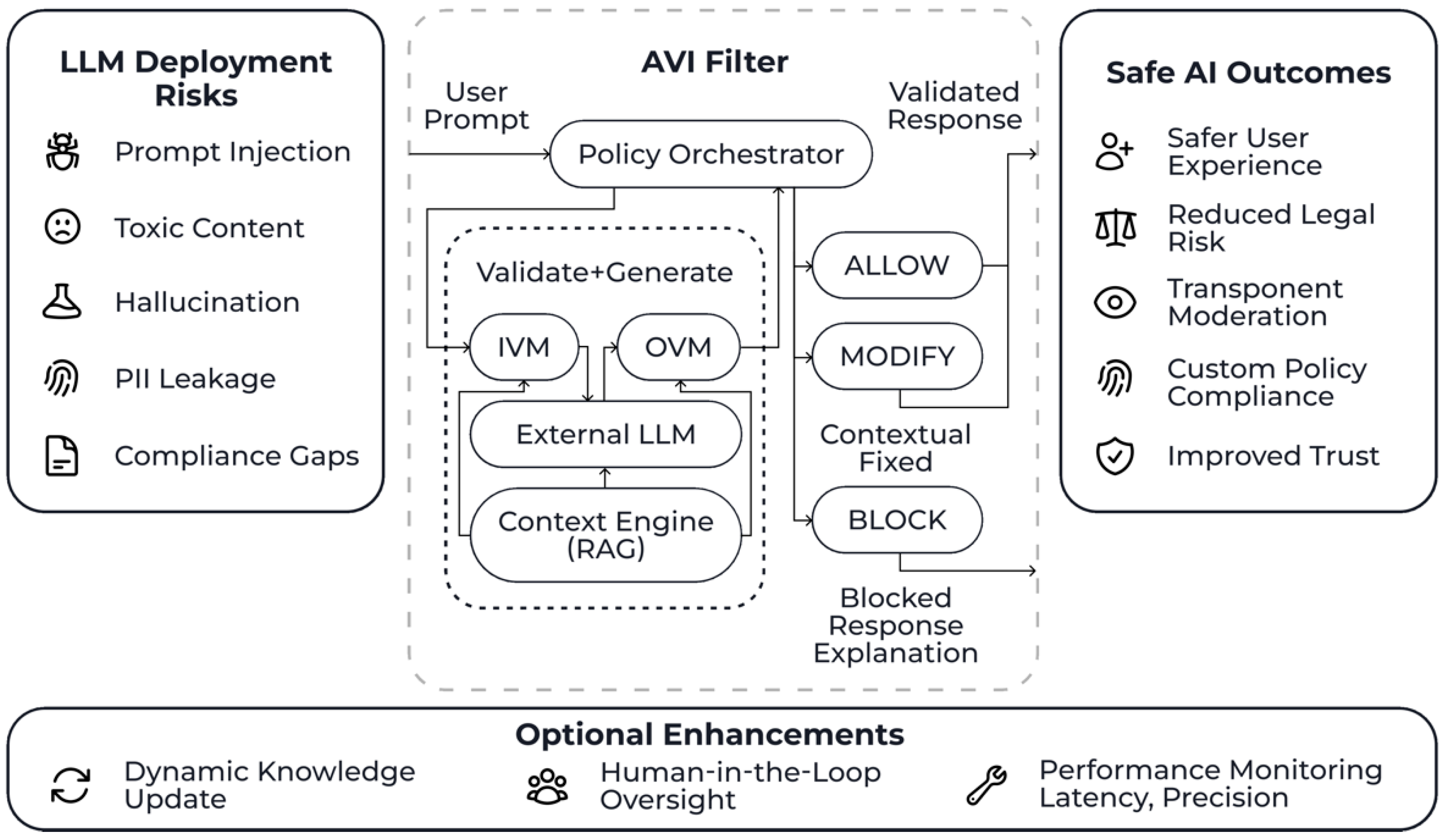

Figure 4.

Governance-Oriented Framework for Safe LLM Deployment via AVI. Source: made by authors.

Figure 4.

Governance-Oriented Framework for Safe LLM Deployment via AVI. Source: made by authors.

All the results are introduced below in structured order.

5.1. Advancing LLM Governance Through Interface Design

Among the most obvious strengths of AVI is its dual ability to perform negative filtering (e.g., blocking rapid entry of unverified data or filtering out toxic outputs) and positive filtering (e.g., grounding responses with trusted context and regulatory compliance). This approach enables the implementation of a model-agnostic information process governance layer. It is also dynamic and configurable, allowing organizations to exercise fine-grained control over AI behavior without changing the underlying software model. This approach also supports the discussed trends and assumptions that external governance tools are necessary for effective governance of AI systems when pre-trained models are distributed as opaque systems or APIs [

59]. The literature reviewed in this paper highlights that external verification mechanisms can significantly complement internal data governance, bridging the gaps in transparency and adaptability [

60]. The AVI interface offers an external point of control for implementation that allows users to integrate domain-specific information and technical policies, industry-specific ethical rules, and context-based reasoning to maintain trust and reduce operational risk.

5.2. Modular, Explainable Safety as a Normative Baseline

The modular architecture of AVI, which separates responsibilities between Input Validation Modules (IVM), Output Validation Modules (OVM), Contextualization Module (CE), and Response Evaluation Module (RAM), supports more transparent and auditable decision-making processes compared to existing interfaces. The advantage of the interface proposed by the authors is that each module can be adapted using rule-based logic, machine learning, or hybrid management logic, and the system's decisions can be verified by developers or compliance teams within the information ecosystem (industry or enterprise). The model presented in this paper meets the growing market demand for explainable AI (XAI), especially in critical infrastructure [

61]. At the same time, when using such an interface, users are able to analyze why an input was rejected, why a response was reformulated, or what risk was identified. AVI enables end-to-end problem recognition and understanding by breaking down interactions in the data governance information model into distinct review steps, each governed by customizable regulatory policies. This design provides a scalable foundation for AI assurance, which is especially relevant in today’s markets as organizations face increasing scrutiny under regulations such as the EU AI Act or the US Algorithmic Accountability Act [

62].

5.3. Navigating Performance vs. Precision Trade-Offs

The balance between system responsiveness and security controls is a constant tension in the AI deployment landscape. The AVI evaluation shows that security interventions do not necessarily entail prohibitive latency. The measured latency overheads—an average of 85 ms without RAG and 450 ms with RAG—suggest that real-time inspection and filtering can be practically integrated into interactive applications, especially those that do not operate under strict request processing latency constraints [

63].

However, domain-specific tuning remains critical. For example, applications in emergency services, trading platforms, or online learning may have stricter thresholds for processing latency. In these cases, organizations can selectively enable or disable certain modules in AVI or use risk stratification to dynamically apply security controls.

5.4. Expanding the Scope of Safety Interventions

Currently, LLM alignment mechanisms, such as those built in during pre-training or implemented through fine-tuning, often lack transparency, flexibility, and generalizability across contexts. Furthermore, many commercial models only partially comply with open fairness norms or user-centered ethical reasoning [

64]. By integrating search-augmented generation (RAG) and real-time verification, AVI goes beyond binary filtering to enable more proactive safety improvements. RAG ensures what Binns et al. [

65] call “contextual integrity,” in which generative responses are limited to verified, trusted data. The results obtained in this paper show that grounding improves not only factuality, but also data neutrality and its compliance with internal ethical rules. However, the success of such interventions depends largely on the quality, relevance, and novelty of the underlying knowledge base. Therefore, ongoing curation and maintenance of the context database remains a critical responsibility in operational environments.

5.5. Challenges and Limitations

Despite the positive results, several limitations require attention. First, the proof-of-concept evaluation was conducted on a narrow set of benchmarks and synthetic inputs, which may not fully reflect the complexities of real-world language use. Expansion to broader datasets, including multilingual and informal content, is needed. Second, the hallucination detection mechanism relied on rudimentary keyword matching and was not benchmarked against state-of-the-art semantic verification techniques, such as NLI or question answering-based consistency models [

66].

Third, AVI requires human oversight for maintaining policy rules, monitoring for new threat vectors, and updating context sources. This creates an operational burden that could limit adoption by smaller organizations lacking dedicated AI governance staff. Future versions of AVI should include a user-friendly policy dashboard, integration with log analytics platforms, and automated alerting systems for policy drift or emergent threats.

Finally, the evaluation was conducted using the Grok-2-1212 model, which may not generalize to other LLM architectures [

66]. Different models exhibit varying behavior in response to the same input due to differences in training data, decoding strategies, and internal alignment mechanisms. Extensive testing across models, including open-source variants, is needed to validate AVI’s universality.

5.6. Future Directions

Building on this foundation, several directions merit further exploration. First, adaptive risk scoring could allow AVI to adjust sensitivity dynamically based on user profiles, query history, or trust levels. Second, integration with audit trails and compliance reporting could help organizations meet documentation requirements for AI oversight. Third, deeper user interface integration, such as alerting end-users to moderated content and offering explanations, would enhance transparency and engagement [

67].

In addition, expanding AVI’s capabilities to handle multimodal input—such as images, speech, or code—would greatly increase its applicability. While the current version focuses on text interactions, the same modular validation logic can be extended with domain-specific detection models (e.g., for visual toxicity or code vulnerabilities). Lastly, future iterations should explore collaborative filtering networks, where risk data and rule templates are shared across organizations to accelerate threat detection and policy refinement.