1. Introduction

Pleurotus ostreatus commonly known as oyster mushrooms were first commercially cultivated in Germany during World War I as a subsistence measure, using tree stumps and wood logs as growing substrates (Deepalakshmi and Sankaran., 2014, Eger et al., 1976). Since then, cultivation of oyster mushrooms has been increasing on a commercial scale in different parts of the world including China, Italy, Poland, Netherlands, Romania, Republic of Korea, Spain, Lithuania and India. China is the world's largest producer of oyster mushrooms, accounting for 74% of the global production (Jarial et al., 2024). In recent times, various species of Pleurotus have been widely cultivated on a commercial scale due to their high mineral content, medicinal benefits, short growth cycle, ability to recycle agricultural and industrial by-products, and minimal requirements for resources and technology (Deepalakshmi and Sankaran., 2014, Raman et al., 2021, Bellettini et al., 2019, Yildiz et al., 2002). These factors, combined with Pleurotus' ability to directly degrade lignin without the need for substrate composting, as required by button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus), have positioned it as a viable food source in post-catastrophic scenarios, such as a nuclear winter (Winstead and Jacobson., 2022).

Many different substrates have been tested for their usefulness in cultivating of P. ostreatus, including cottonseed (Gossypium hirsutum L.), paper waste, wheat straw, sawdust (Girmay et al., 2016), palm waste supplemented with rice bran and wheat bran (Triticum aestivum L.) (Elkanah et al., 2022), rice husk, eucalyptus sawdust (Costa et al., 2023), hazelnut (Corylus avellana L.) branches, spent coffee grounds (Akcay et al., 2023), and peanut hulls (Zied et al., 2019). The lignolytic enzymes produced by Pleurotus species enable them to degrade and colonize a range of substrates, utilizing them as nutrient sources to support growth and initiate fruiting body production (Ruiz-Rodríguez et al., 2011). In Asia, rice straw and cotton waste are among the most used substrates for cultivation (Raman et al., 2021). In Sri Lanka, sawdust has traditionally served as a medium for oyster mushroom cultivation (Rajapakshe et al., 2007). In the United States, Pleurotus spp. are commonly cultivated on substrates such as chopped wheat straw, cottonseed hulls, or combinations of these materials (Penn State Department of Plant Pathology and Environmental Microbiology, 2024). Although substrate composition influences the nutritional quality of mushrooms (Elkanah et al., 2022), the choice of substrate in different countries is largely determined by cost and availability (Assan and Mpofu., 2014). However, there is also a need to explore the potential of substrates such as wood chips, especially in resource-limited settings. In post-catastrophic scenarios, industrial by-products like cotton seed hulls may not be readily available, necessitating reliance on forest resources like wood as energy input (Winstead and Jacobson., 2022).

This study aims to evaluate the growth performance of P. ostreatus on woody substrates, such as willow chips, and to compare its yield and nutritional composition with those obtained using the standard commercial cultivation formula. Additionally, a second treatment involving willow wood chips supplemented with cottonseed hulls is included to assess whether minimal supplementation can enhance performance or achieve results comparable to the standard substrate. The objective is to determine whether substrates like wood chips can serve as viable alternative and to predict the growth potential of P. ostreatus in challenging environments, such as those that may occur during a nuclear winter, where resource availability is limited. Furthermore, the study aims to compare key nutritional components, including protein and vitamin content, across the different substrates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Strain and Spawn

For our cultivation trials, organic blue oyster mushroom sawdust spawn was utilized from a commercial supplier (North Spore, Portland ME). Blue Oyster (P. ostreatus) is a fast substrate colonizer with a strong bluish-gray hue. Following our research, this isolate has been added to the Penn State University culture collection and is now designated as WC 1073. Fungal strain was maintained in liquid nitrogen –4°C and subcultured on to Potato Dextrose Agar plates.

2.2. Substrate Preparation, Inoculation, and Incubation

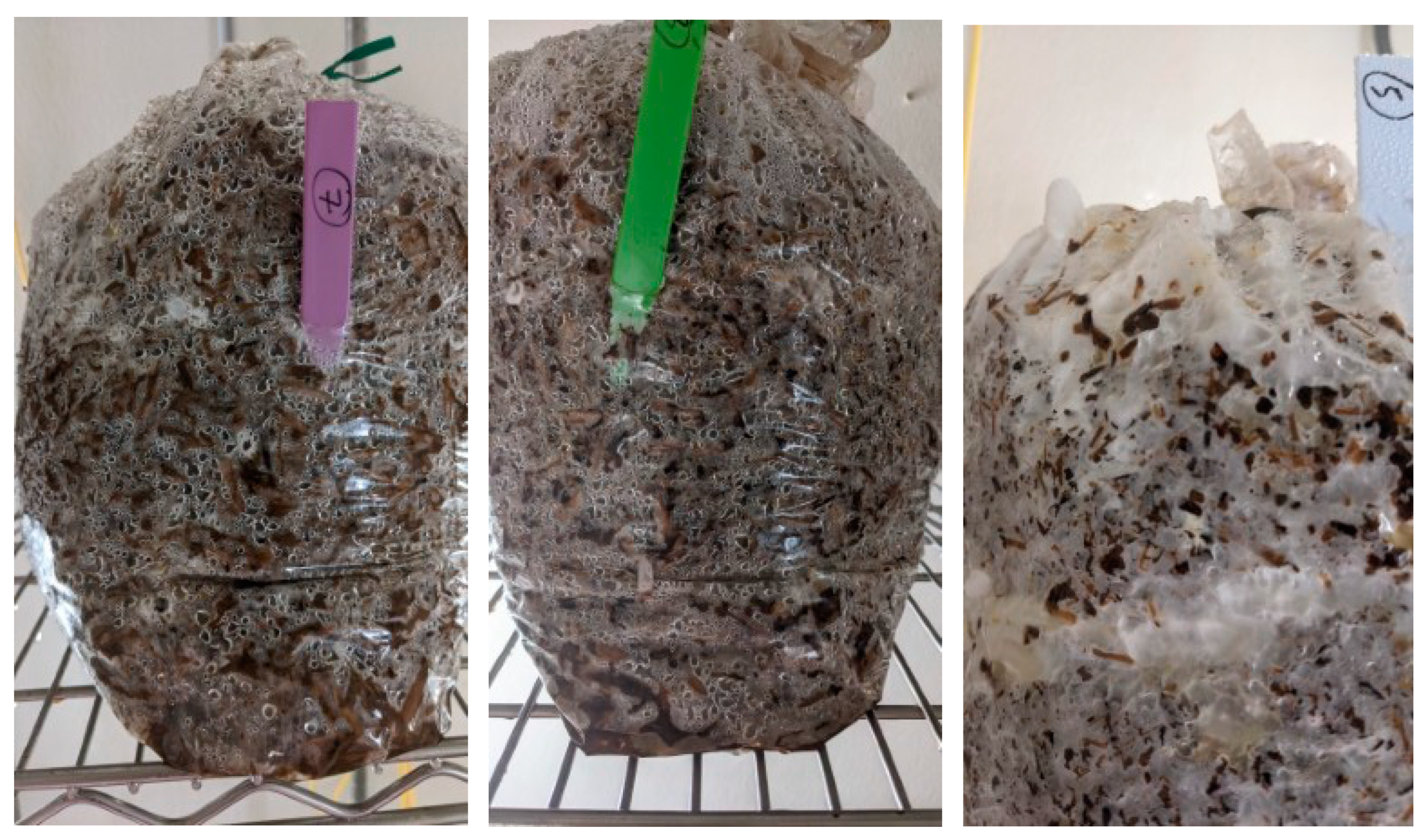

For

P. ostreatus, the optimal substrate used on an industrial / commercial scale in United States is a mixture of cottonseed hull, wheat straw and a protein supplement (Promycel Gold

TM, San Juan Bautista, CA) in the ratio 16:2:1 (w/w). This standard/commercial substrate was compared against minimally supplemented substrates W+C (Willow chips and cotton seed hull (3:1)) and W (Willow chips) to access any differences in the yield and nutritional differences. Shrub willow,

Salix spp., obtained from The Pennsylvania State University’s bioenergy crop fields (40°51′36.92″, −77°47′50.37″, elevation 370 m) in July 2021 were used for the study. Willow trees have high biomass potential and fast growth rate compared to other tree species (Volk et al., 2004, Kajba et al, 2014). Willow was chopped into willow chips of approximate dimensions 1-1.5cm × 0.5cm × 0.2 cm (

Figure 1) in a chopper at Mushroom Research Center, Penn State. Wood chips were soaked in water for 24 h, drained and used as substrate for our cultivation trials.

Substrate moisture content plays a crucial role in mycelial growth (Koo et al., 1999, Wiesnerová et al., 2023, Shen et al., 2008), with an optimal range typically between 50–60%, depending on the substrate type and mushroom species (Hřebečková et al., 2024). In this study, the substrate was mixed with water to achieve a moisture content of approximately 55%, suitable for mushroom growth. Three different substrates were prepared and filled into autoclavable bags, with each bag containing 2 kg of substrate. The filled bags were then autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min. The bags were then cooled to room temperature and spawned at a rate of 4–5% of the wet weight of the bag. Each treatment/substrate was represented by six replicates/bags.

The optimal temperature for the mycelial growth of P. ostreatus is around 22-25°C (Hoa et al., 2015, Ghavimi et al., 2023, Hu et al., 2023) and a lower temperature (Sánchez, 2010) of between 15-20°C is preferred for fruiting (Zhou et al., 2016). In this study, the bags were incubated at a consistent temperature of 15°C to assess the fungal strain's performance under cool conditions. This approach seeks to determine its viability in scenarios like post-catastrophic events, such as a nuclear winter, where reducing energy demands for food production is essential.

2.3. Cropping, Harvesting and Determination of Biological Efficiency

After inoculation, substrate bags were sealed and incubated at 15 °C with 12 h of light maintained. After 25 days of mycelial colonization/ spawn run, 8 slits of approximately 2 cm length were made along the sides of the bag, to allow the lateral fruiting body production of

P. ostreatus (

Figure 2). Relative humidity in the room was maintained at 90%. Mycelial growth rate, days to pinning and fruiting were recorded. Within a few days small primordia (pins) emerged (

Figure 3) and mushrooms were ready to be harvested within the next few days. Data was collected for 30 days after pinning. Mature mushroom clusters (

Figure 4) were harvested and weighed from the substrate by cutting the stipe at the base where it attaches to the substrate bag.

The growth and development of mushrooms were monitored daily. The time required from inoculation to the completion of mycelial running, the time elapsed between opening the plastic bags and the formation of primordia/pins, and the time needed from opening the bags to the first harvest were recorded. Yield parameters were measured at harvest time, including the total fresh weight of mushrooms (g). Mature fruiting bodies, identified by their yellowish-brown color and reduced mucilage on the cap, were harvested by severing the base just above the substrate surface with a sharp blade or scissors. Two rounds, or flushes, of mushroom harvests were conducted across all substrate treatments during the experiment. To evaluate the mushrooms’ growth performance on different substrates, yield and biological efficiency were calculated.

% Biological efficiency = x 100

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted using R Studio at a 5% significance level, followed by Tukey’s HSD test. Mean values and standard deviations were calculated for each parameter.

2.4. Substrate and Mushroom Fruiting Body Analyses

Substrate was analyzed in collaboration with Penn State Agriculture Analytical Center and mushroom fruiting bodies were analyzed in collaboration with Penn State Agriculture Analytical Center and the Dr. Lambert Lab, Department of Food Science, Penn State. The crude protein content was measured based on the Dumas method, using a LECO FP 828p Nitrogen analyzer (St Joseph, Mi, USA) and calculated by multiplying the total nitrogen content by a conversion factor of 4.44 (Dwyer et al., 2000, Deepalakshmi and Sankaran., 2014). The analysis of water-soluble vitamins was carried out by LC/MS on a Vanquish UHPLC chromatographic system coupled to TSQ Quantis mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a H-ESI ion source by the electrospray ionization method in positive and negative modes. The extraction of Vitamin D2 from P. ostreatus mushrooms followed a modified version of the procedure (Hoa et al., 2015) described by Hu et al. (2020). Vitamin D2 quantification was performed using a 1260 Infinity Series HPLC system equipped with a UV/DAD detector (Agilent Technologies, Mainz, Germany). Separation was achieved using a Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 column (3.5 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm, Agilent Technologies) maintained at 30°C. An isocratic mobile phase of 95% aqueous methanol was used at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The injection volume was 50 μL. Vitamin D2 was detected at 265 nm and quantified by comparison to an external calibration curve. Concentrations were expressed on a dry weight basis.

3. Results

3.1. Substrate Analysis

The composition of lignocellulosic substrates affects the yield and biological efficiency during mushroom cultivation (Xiao et al., 2019, Assan and Mpofu., 2014). Lignocellulosic substrates are mainly composed of carbon, which is the main nutrient required by mushrooms (Subedi et al., 2023). In addition to the carbon content, the C:N ratio of the substrate can directly affect the yield of

P. ostreatus (Cueva et al., 2017). For best yields, the C:N ratio of the substrate should be between 28:1 to 30:1 and extreme C:N ratios can adversely affect mushroom production (Bellettini et al., 2019, Subedi et al., 2017). In our study we observed that woody substrates, such as willow chips (W), are rich in carbohydrates, which increases their carbon content and raises the C:N ratio (

Table 2). On the other hand, the standard substrate (S), in addition to cottonseed hull and wheat straw, contains a protein supplement, Promycel gold

TM, which reduces the overall C:N ratio (

Table 2).

3.2. Time Elapsed for Mycelial Colonization, Pin-Head Formation and Maturity of Fruiting Body

The

P. ostreatus strain used in this study was able to completely colonize all treatment bags within 25 d. Eight slits, each approximately 2 cm in length, were made on the sides of the bag on 25th d and humidity of the room was raised to 90%. Pinheads started appearing within 5 d and mushrooms were mature and harvested within 10 d after slits were made. The temperature during the mycelial colonization, bag opening, and cropping phases was maintained at 15°C. There was no notable variation in the rate of colonization, primordium development, or fruit body maturation between treatments (

Figure 5).

3.3. Effect of Different Substrates/ Treatments on Yield and Biological Efficiency

In this study, a significant difference was observed when the yield and biological efficiency of P.

ostreatus grown on standard substrate (S) and supplemented willow (W+C) was compared with willow (W). There was no significant difference between substrates S and W+C, but both were significantly different from substrate W. The standard formulation did yield significantly more mushrooms than the willow alone treatment (238.5% higher total yield). Supplementing willow with 25% cotton seed hulls resulted in a 162.3% increase in yield compared to willow alone (

Table 3). The fresh weight of the first flush in S was approximately 158.05% greater than in W. The second flush was also higher in S compared to W. Additionally, observations of mycelial density indicated that substrate S exhibit higher mycelial density compared to those based on W and W +C (

Figure 6).

In this study, 2 kg substrate bags had a moisture content of approximately 55%, indicating that the remaining 45% (900 g) represented dry matter, primarily composed of carbon. This substrate yielded 259 g of fresh mushrooms when cultivated on willow (W) (

Table 1). Given that fresh mushrooms contain approximately 90% water, this corresponds to 25.9 g of dry mushroom matter. Further analysis revealed that 100 g of dry

P. ostreatus powder contains 15.4 g of digestible protein when the mushrooms are produced from substrate W (

Section 3.4,

Table 4). Based on these results, for instance, growing

P. ostreatus in 1 kg of dry willow substrate produced 28.7 g of digestible matter, including 4.4 g of digestible protein.

Table 1.

Three treatments/substrates used in the study for the cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus.

Table 1.

Three treatments/substrates used in the study for the cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus.

| Treatment/Substrate |

Substrate composition |

| S |

Cottonseed hull, wheat straw and a protein supplement (Promycel Gold) 16:2:1 (w/w)

(Commercial/Standard oyster formula)

|

| W+C |

Willow chips and cottonseed hull 3:1 w/w |

| W |

Willow chips alone |

Table 2.

Chemical properties of different substrate treatments.

Table 2.

Chemical properties of different substrate treatments.

Analyte

(Dry weight basis)

|

S |

W+C |

W |

| pH |

6.2 |

5.9 |

5.1 |

| Organic matter% |

95.9 |

96.5 |

94.1 |

| Total nitrogen (N) % |

1.81 |

0.79 |

0.52 |

| Carbon (C) % |

48.2 |

46.9 |

41.5 |

| C:N ratio |

26.6 |

59.2 |

80.10 |

Table 3.

Days to fruiting and yield of WC 1073 strain of Pleurotus ostreatus.

Table 3.

Days to fruiting and yield of WC 1073 strain of Pleurotus ostreatus.

| Productivity parameters |

S |

|

W+C |

W |

| First harvest (DAI) |

35 |

|

35 |

35 |

| First flush (g) |

3783 ±103.0a |

|

3348±240.4a |

1466±75.0b |

| Second flush (g) |

1507±126.0a |

|

917±157.8a |

165±27.9b |

| Total yield (g) |

877.2±85.7a |

|

679.63 ±198.2a |

259.09 ±76.3b |

| Biological efficiency (%) |

98.0a |

|

79.0a |

30.2b |

| DAI = Days After Inoculation |

|

Values represent means± standard deviation of 6 replicates/ bags. Different letters indicate significant differences (p<0.05) using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

|

3.4. Effect of Different Substrates on Nutritional Composition of Fruiting Body

In our study we analyzed crude and digestible protein, carbohydrates, lipids and ash content (

Table 4). We also analyzed water soluble vitamins B1, B2, B3, B9, C and fat-soluble vitamin D2 (

Table 5). From our results we find the type of substrate significantly affects the digestible protein content, but did not significantly affect crude protein. Oyster mushrooms cultivated on willow (W) substrate contain a digestible protein content of 15.42 g per 100 g, which is 94.8% of the amount found in mushrooms grown on S. The digestible protein content of mushrooms grown on W was significantly different from that of those grown on S, but not significantly different from those grown on W+C. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (dRDA) for protein is 0.8 g per kilogram of body weight per day (Wolfe et al., 2017, Lonnie et al., 2018). For a consumer weighing 70 kg, 100 g of dry powder from mushrooms grown on W would supply approximately 28% of this daily protein requirement, underscoring its potential as a supplementary protein source.

While proteins are required in large amounts for the human body to support growth and tissue repair, vitamins are needed in smaller quantities for normal metabolism and growth (Zohoori, 2020). Vitamin C and vitamin D2 were significantly higher in mushrooms grown on willow substrate compared to the other substrates (

Table 5). The recommended daily intake (RDI) for Vitamin B1, B2, B3, B9, C and D3 is 1.2 mg, 1.3 mg, 16 mg, 400 µg, 90 mg and 15 µg (600 IU), respectively (Dwyer et al., 2000). Consumption of 100g of dry powder from oyster mushrooms grown on W would provide approximately 17.5% of RDI for thiamine (B1), 14.6% for riboflavin (B2), 12.1% for niacin (B3), 13.7% for vitamin C, and 6.3% for folate (B9). Notably, the sample contained 72.9 µg of vitamin D2, contributing to 486% of the RDI for vitamin D2, indicating that oyster powder is a particularly rich source of this nutrient.

Table 4.

Proximate composition of Pleurotus ostreatus mushrooms grown in three different substrates.

Table 4.

Proximate composition of Pleurotus ostreatus mushrooms grown in three different substrates.

| Nutrient (g/100g dry weight) |

S |

W+C |

W |

| Crude Protein |

20.93 ± 0.3a |

21.12 ± 0.04a |

21.03 ± 0.1a |

| Digestible Protein |

16.26 ± 0.2a |

15.77 ± 0.1ab |

15.42 ± 0.5b |

| Carbohydrates |

48.92 ± 2.3 a |

49.12 ± 2.2a |

48.57 ± 0.9a |

| Dry weight |

14.88 ± 1.6a |

16.12 ± 1.2a |

15.96 ± 1.7a |

| Lipids |

0.44 ± 0.01a |

0.45 ± 0.0a |

0.45 ± 0.0a |

| Ash |

10.38 ± 0.8a |

9.62 ± 1.4a |

9.99 ± 1.0a |

|

Values represent means± standard deviation of 3 replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (p<0.05) using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test.

|

Table 5.

Comparative vitamin compositions of Pleurotus ostreatus mushrooms grown in three different substrates.

Table 5.

Comparative vitamin compositions of Pleurotus ostreatus mushrooms grown in three different substrates.

| Values per 100g dry weight |

S |

W+C |

W |

| Thiamine mg/100 g |

0.26 ± 0.1a |

0.25 ± 0.1 a |

0.21 ± 0.1 a |

| Riboflavin mg/100 g |

0.14 ± 0.02a |

0.18 ± 0.05 a |

0.19 ± 0.15a |

| Niacin mg/100 g |

1.41 ± 0.16a |

1.91 ± 0.6a |

1.93 ± 0.32a |

| Ascorbic acid mg/100 g |

4.83 ± 1.2b |

8.01 ± 1.5b |

12.37 ±2.2a |

| Folate ug/100 g |

17.3 ± 8.2a |

24.71 ± 13.7a |

25.3 ± 12.1a |

| Ergocalciferol ug/100 g |

36.2 ± 1.9c |

54.8 ± 2.9b |

72.9 ± 9.1a |

| Values represent means ± standard deviation of 3 replicates. Different letters indicate significant differences (p<0.05) using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. |

3.5. Effect of Different Substrate Formulas on Mineral Content of Fruiting Body

Minerals play a vital role in the human body, supporting essential functions such as maintaining a healthy immune system and regulating inflammation (Weyh et al., 2022). The mineral content in

P. ostreatus grown on different substrates including sawdust, sugarcane bagasse, corn cob (Hoa et al., 2015), different woody substrates (

Oyetayo and Ariyo., 2013), soyabean straw, paddy straw, wheat straw (Sopanrao et al., 2010) has been widely explored. In this study we compared the mineral content of

P. ostreatus mushroom grown in 3 different substrates. N, P, K, S, Mn, Fe, Cu, Zn and Na were analyzed. Results indicated that nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium are the most abundant (

Table 6); however, there was no significant difference in mineral content among treatments at the 5% significance level. This demonstrates that supplemented woodchips, or minimal formulated substrates can be used to grow

P. ostreatus as a food source to satisfy mineral requirements in case of post catastrophic period.

The recommended daily intake of macro elements for adults includes phosphorus (700 mg), potassium (2600–3400 mg), and sodium (1500 mg) (Farag et al., 2023). The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for trace elements is 18 mg/day for iron (Fe), 10 mg/day for zinc (Zn), 2 mg/day for manganese (Mn), and 1 mg/day for copper (Cu) (Espinosa-Salas and Gonzalez-Arias., 2023). Consuming 100 g of dry oyster mushroom powder provides 125.7% of the RDI for phosphorus, 130.9–171.3% for potassium (depending on the RDI range), and 2.1% for sodium. For trace elements, it supplies 20.3% of the RDI for iron, 55.9% for zinc, 43% for manganese, and 194% for copper. These findings indicate that oyster mushrooms are a good dietary source of phosphorus, potassium, zinc, and copper, with moderate contributions to iron and manganese intake, while providing minimal sodium.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that the cultivation of P. ostreatus on minimal substrates, particularly willow chips, presents a viable alternative to traditional commercial substrates, with potential applications in resource-limited environments. While the yield on willow chips (W) was significantly lower than that on the standard commercial substrate (S), the supplementation of willow chips with cottonseed hulls (W+C) enhanced the yield to a level comparable to the standard substrate, highlighting the potential of low-cost, sustainable alternatives. Furthermore, the nutritional analysis revealed that mushrooms grown on willow substrates had higher levels of vitamins C and D3, with comparable levels of all minerals, emphasizing their nutritional value. These findings underline the feasibility of using minimal, low-cost substrates like willow chips for sustainable mushroom production, which can be valuable in resource-limited environments, and highlight the nutritional benefits of oyster mushrooms as an alternative food source with substantial protein and vitamin content. This research contributes to the growing body of knowledge on sustainable agricultural practices and the potential role of P. ostreatus in addressing food security issues in post-catastrophic scenarios.

Author Contributions

Swathi Kothattil: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing, Writing - review and editing. Marjorie Jauregui: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing - review and editing. Joshua D. Lambert: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing - review and editing. John A. Pecchia: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - review and editing.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from Open Philanthropy entitled Food Resilience in the Face of Global Catastrophic Events as well as the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and Hatch Appropriations under Project #PEN04741 and Accession #1023198”.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Our heartfelt thanks to Edward Kaiser, Research Technologist at the Mushroom Spawn Lab, Penn State for his assistance in spawn preparation and ongoing guidance. We sincerely thank Open Philanthropy for providing financial support for this research. We also extend our appreciation to the Penn State Food Resiliency team for their guidance and contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial or non-financial interests.

References

- Akcay, C.; Ceylan, F.; Arslan, R. Production of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) from some waste lignocellulosic materials and FTIR characterization of structural changes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assan, N. , & Mpofu, T. (2014). The influence of substrate on mushroom productivity.

- Bellettini, M.B.; Fiorda, F.A.; Maieves, H.A.; Teixeira, G.L.; Ávila, S.; Hornung, P.S.; Júnior, A.M.; Ribani, R.H. Factors affecting mushroom Pleurotus spp. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 26, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.F.P.; Steffen, G.P.K.; Steffen, R.B.; Portela, V.O.; Santana, N.A.; Richards, N.S.P.d.S.; Jacques, R.J.S. The use of rice husk in the substrate composition increases Pleurotus ostreatus mushroom production and quality. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, M. B. R. , Hernández, A., & Niño-Ruiz, Z. (2017). Influence of C/N ratio on productivity and the protein contents of Pleurotus ostreatus grown in differents residue mixtures. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias, 49(2), 331-344.

- Deepalakshmi, K. , & Sankaran, M. (2014). Pleurotus ostreatus: an oyster mushroom with nutritional and medicinal properties. Journal of Biochemical Technology, 5(2), 718-726.

- Dwyer, J. T. , Melanson, K. J., Sriprachy-anunt, U., Cross, P., & Wilson, M. (2000). Dietary treatment of obesity.[Updated 2015 Feb 28]. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText. com, Inc.

- Eger, G.; Eden, G.; Wissig, E. Pleurotus Ostreatus ? breeding potential of a new cultivated mushroom. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1976, 47, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkanah, F.; Oke, M.; Adebayo, E. Substrate composition effect on the nutritional quality of Pleurotus ostreatus (MK751847) fruiting body. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Salas, S. , & Gonzalez-Arias, M. (2023). Nutrition: micronutrient intake, imbalances, and interventions. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

- Farag, M.A.; Abib, B.; Qin, Z.; Ze, X.; Ali, S.E. Dietary macrominerals: Updated review of their role and orchestration in human nutrition throughout the life cycle with sex differences. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavimi, P. , Soni, R., Caray, M., & Khawaja, A. (2023). Determining the Optimal Temperature for Pleurotus ostreatus Mycelium Growth. The Expedition, 15.

- Girmay, Z.; Gorems, W.; Birhanu, G.; Zewdie, S. Growth and yield performance of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq. Fr.) Kumm (oyster mushroom) on different substrates. AMB Express 2016, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, H.T.; Wang, C.-L. The Effects of Temperature and Nutritional Conditions on Mycelium Growth of Two Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus and Pleurotus cystidiosus). Mycobiology 2015, 43, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hřebečková, T.; Wiesnerová, L.; Hanč, A.; Koudela, M. Effect of substrate moisture content during cultivation of Hericium erinaceus and subsequent vermicomposting of spent mushroom substrate in a continuous feeding system. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xue, F.; Chen, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wang, F.; Wen, Q.; Shen, J. Effects and Mechanism of the Mycelial Culture Temperature on the Growth and Development of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditya; Neeraj; Jarial, R. ; Jarial, K.; Bhatia, J. Comprehensive review on oyster mushroom species (Agaricomycetes): Morphology, nutrition, cultivation and future aspects. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajba, D. , & Andrić, I. (2014). Selection of willows (Salix sp.) for biomass production. South-east European forestry: SEEFOR, 5(2), 145-151.

- Koo, C. D. , Kim, J. S., Cho, N. S., Min, D. S., & Ohga, S. (1999). Effect of moisture content for mycelial growth and primordial formation of Lentinula edodes in a sawdust-based substrate. Mushroom science and biotechnology, 7(4), 169-174.

- Lonnie, M.; Hooker, E.; Brunstrom, J.M.; Corfe, B.M.; Green, M.A.; Watson, A.W.; Williams, E.A.; Stevenson, E.J.; Penson, S.; Johnstone, A.M. Protein for Life: Review of Optimal Protein Intake, Sustainable Dietary Sources and the Effect on Appetite in Ageing Adults. Nutrients 2018, 10, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North Spore. (n.d.). Blue oyster mushroom sawdust spawn. North Spore. https://northspore.com/collections/sawdust-spawn/products/blue-oyster-mushroom-sawdust-spawn.

- Oyetayo, V. O. , & Ariyo, O. O. (2013). Micro and macronutrient properties of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq: Fries) cultivated on different wood substrates. Jordan Journal of Biological Sciences, 6(3), 223-226.

- Penn State Department of Plant Pathology and Environmental Microbiology. (n.d.). Production technology: Specialty mushrooms. Penn State University. https://plantpath.psu.edu/about/facilities/mushroom/resources/specialty%20mushrooms/production-technology.

- Rajapakse, J.C.; Rubasingha, P.; Dissanayake, N.N. The effect of six substrates on the growth and yield of American oyster mushrooms based on juncao technology. J. Agric. Sci. 2007, 3, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, J. , Jang, K. Y., Oh, Y. L., Oh, M., Im, J. H., Lakshmanan, H., & Sabaratnam, V. (2021). Cultivation and nutritional value of prominent Pleurotus spp.: an overview. Mycobiology, 49(1), 1-14.

- Raman, J. , Jang, K. Y., Oh, Y. L., Oh, M., Im, J. H., Lakshmanan, H., & Sabaratnam, V. (2021). Cultivation and nutritional value of prominent Pleurotus spp.: an overview. Mycobiology, 49(1), 1-14.

- Ruiz-Rodríguez, A.; Polonia, I.; Soler-Rivas, C.; Wichers, H.J. Ligninolytic enzymes activities of Oyster mushrooms cultivated on OMW (olive mill waste) supplemented media, spawn and substrates. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation 2011, 65, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C. Cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus and other edible mushrooms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 85, 1321–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Liu, P.; Wang, X.; Royse, D.J. Effects of substrate moisture content, log weight and filter porosity on shiitake (Lentinula edodes) yield. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 8212–8216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopanrao, P. S. , Abrar, A. S., Manoharrao, T. S., & Vaseem, B. M. M. (2010). Nutritional value of Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq: Fr) Kumm cultivated on different lignocellulosic agro-wastes. Innovative Romanian food biotechnology, (7), 66-76.

- Subedi, S.; Kunwar, N.; Pandey, K.R.; Joshi, Y.R. Performance of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) on paddy straw, water hyacinth and their combinations. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, T. A. , Verwijst, T., Tharakan, P. J., Abrahamson, L. P., & White, E. H. (2004). Growing fuel: a sustainability assessment of willow biomass crops. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2(8), 411-418.

- Weyh, C.; Krüger, K.; Peeling, P.; Castell, L. The Role of Minerals in the Optimal Functioning of the Immune System. Nutrients 2022, 14, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesnerová, L.; Hřebečková, T.; Jablonský, I.; Koudela, M. Effect of different water contents in the substrate on cultivation of Pleurotus ostreatus Jacq. P. Kumm. Folia Hortic. 2023, 35, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winstead, D.J.; Jacobson, M.G. Forest Resource Availability After Nuclear War or Other Sun-Blocking Catastrophes. Earth's Futur. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, R.R.; Cifelli, A.M.; Kostas, G.; Kim, I.-Y. Optimizing Protein Intake in Adults: Interpretation and Application of the Recommended Dietary Allowance Compared with the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2017, 8, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Q.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Ma, F. The potential of cottonseed hull as biorefinery substrate after biopretreatment by Pleurotus ostreatus and the mechanism analysis based on comparative proteomics. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2019, 130, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, S.; Yildiz, Ü.C.; Gezer, E.D.; Temiz, A. Some lignocellulosic wastes used as raw material in cultivation of the Pleurotus ostreatus culture mushroom. Process. Biochem. 2002, 38, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Ma, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Carbohydrate changes during growth and fruiting in Pleurotus ostreatus. Fungal Biol. 2016, 120, 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zied, D.C.; Prado, E.P.; Dias, E.S.; Pardo, J.E.; Pardo-Gimenez, A. Use of peanut waste for oyster mushroom substrate supplementation—oyster mushroom and peanut waste. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2019, 50, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohoori, V. (2020). Nutrition and diet. The Impact of Nutrition and Diet on Oral Health, 1-13.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).