1. Introduction

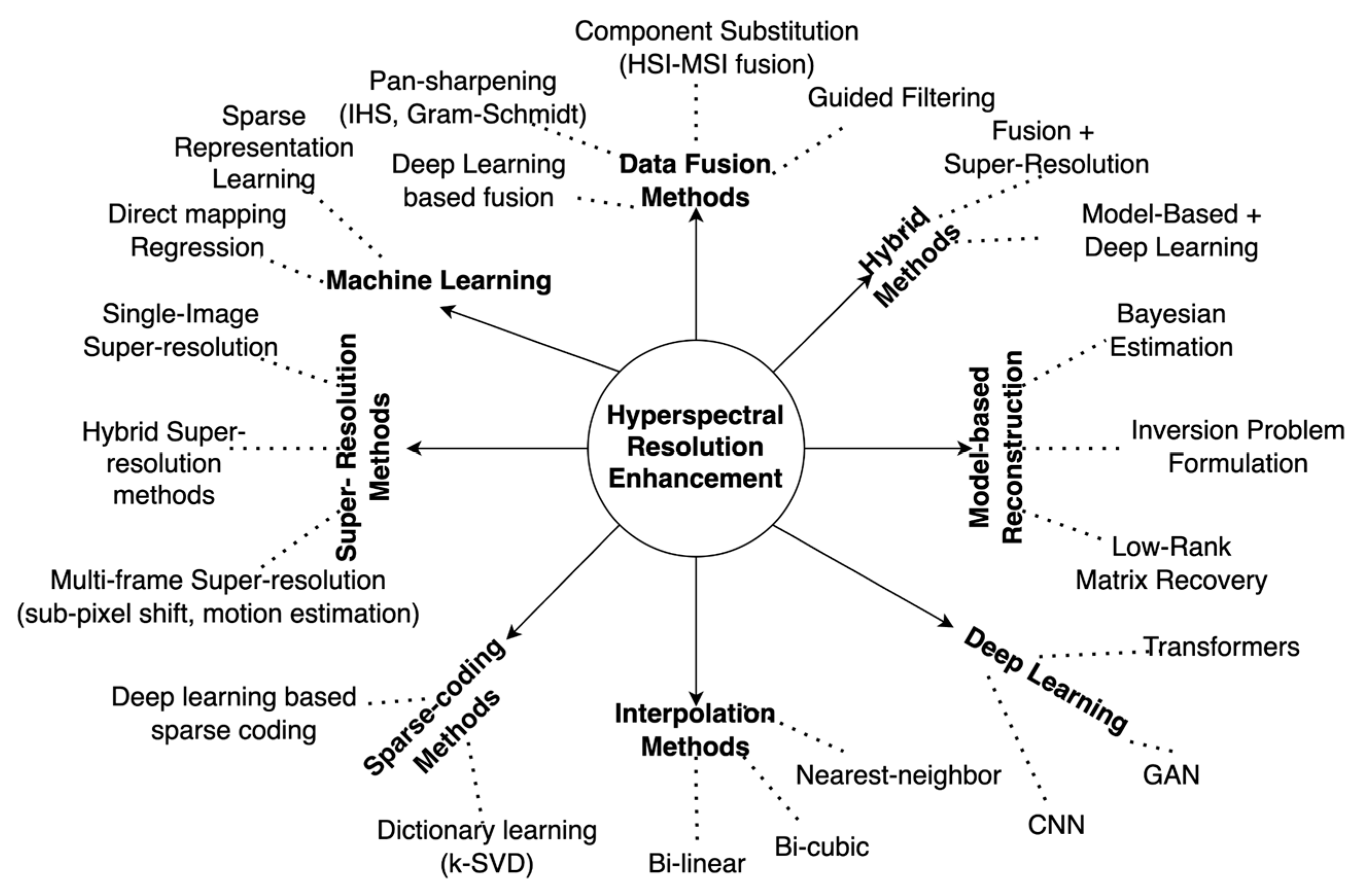

Hyperspectral imaging data (HSI) captures detailed spectral information across a wide range of wavelengths, which inherently results in a trade-off between spatial and spectral resolution. A range of resolution enhancement methods have been developed to help mitigate resolution limitations, each with distinct approaches to improving spatial fidelity while preserving (hyper) spectral information. These HSI resolution enhancement methods can be broadly categorized into data fusion-based methods, model-based super-resolution techniques, regularization approaches, and hybrid methods that combine several solitary techniques. Understanding the taxonomy of these techniques and their fundamental differences is important for selecting the most suitable approach for specific applications. Data fusion-based enhancement methods integrate HSI with co-registered high-resolution datasets, such as panchromatic (Pan) or multispectral imaging data (MSI). The most classical fusion approaches are pan-sharpening techniques, which fuse a high-spatial resolution panchromatic band with low resolution HSI. There are several pan-sharpening techniques, among which the PCA-based component substitution approaches [

1,

2], Gram-Schmidt spectral sharpening method [

3] and guided filters [

4,

5] are classically used for HSI pansharpening. Multisensor fusion methods extend pan-sharpening approaches by combining data from multiple modalities, theoretically enabling more comprehensive resolution enhancement. Techniques such as coupled nonnegative matrix factorization (CNMF) [

6] jointly decompose high-resolution MSI and low-resolution HSI into shared spectral and spatial components, effectively integrating their complementary information for enhanced spatio-spectral resolution. HySure [

7] is another popular fusion-based method where the high-resolution data is reconstructed by exploiting a low-dimensional subspace representation of HSI. Subspace-based regularization ensures stability and preserves spectral integrity while incorporating prior knowledge for accurate reconstruction.

In contrast to pan-sharpening, model-based super-resolution techniques aim to generate high-resolution HSI from low-resolution inputs, either by enhancing individual images (single-image super-resolution) or combining multiple observations (multi-image super-resolution) through a feature learning mechanism. Traditional super-resolution methods like maximum a posteriori estimation (MAP) [

8,

9] and spectral reconstruction methods [

10,

11] rely on mathematical modeling and prior information to deliver high-resolution HSI and often suffer from computational inefficiencies. Deep learning has significantly advanced HSI image super-resolution (HSI-SR) by offering models tailored to the unique challenges of spectral and spatial fidelity. Early models like FS-3DCNN [

12] and SRCNN [

13] adapted convolutional networks to HSI, leveraging 3D convolutions to capture spatio-spectral features. Deep residual models [

14,

15,

16] adapted residual learning for HSI-SR, enabling effective feature extraction across multiple spectral bands with improved reconstruction quality. GAN-based models like HS-SRGAN [

17] and HyperGAN [

18] incorporated adversarial and perceptual loss to generate visually realistic high-resolution HSIs, ensuring finer spatial details while preserving spectral integrity. Channel attention mechanisms were introduced in MPNet [

19] and HSRnet [

20] enabling models to focus on critical spectral features while maintaining enhanced spectral fidelity through neighbor-group integration. The latest advancements in this category include models like ESSAformer [

21] and Interactformer [

22], which integrate transformer and 3D convolutional architectures to effectively balance global and local feature extraction.

Lastly, hybrid enhancement methods combine multiple approaches, e.g., fusing pan-sharpening with deep learning-based super-resolution, to leverage their respective strengths. In such a scenario, pan-sharpening methods excel in integrating spatial details from complementary sources, while deep super-resolution techniques focus on internal feature learning. Several earlier proposed hybrid methods, including the approach in [

23], integrate spectral unmixing with data fusion techniques, wherein HSI is decomposed into endmembers and abundance maps that are subsequently refined using high-resolution MSI imagery. Similarly, [

24,

25] introduces a hybrid framework that couples sparse representation with convolutional neural networks (CNNs), where sparse coding provides an initial estimation, and the CNN predicts high-frequency spatial details for refinement. More recently, methods incorporating generative adversarial networks (GANs) have emerged, such as the work [

26], which combines a GAN-based super-resolution model with a physical observation model to enhance both spatial quality and spectral accuracy. These examples illustrate how hybrid methods evolve by blending classical, physics-driven and statistical techniques with capabilities of advanced machine learning approaches, leading to more robust and versatile solutions for HSI resolution enhancement. The taxonomy of these methods is shown in

Figure 1, to underscore the diverse strategies available for enhancing HSI.

This paper presents a novel hybrid fusion-based process for enhancing spatial resolution of HSI by integrating high-resolution MSI through a multi-stage process that conducts feature decomposition, sparse coding, and parallel patch-wise refinement. Our method, Parallel Patch-wise Sparse Residual Learning (P2SR), offers a robust and efficient solution for hyperspectral resolution enhancement. It addresses some critical limitations in contemporary and recent methods, specifically, noise amplification, high-training data requirements, computational time and information loss. It avoids the global assumptions of CNMF and similar factorization approaches by using a patch-wise strategy that adapts to local data structures, reducing sensitivity to noise and improving detail reconstruction. It also avoids over-smoothing and aliasing artefacts (as observed in single/multi-image super-resolution methods) and reliance on large training datasets (a key requirement in deep learning methods). The proposed method also places special emphasis on scalability and potential real-time application capability through its distributed computation framework and parallel patch processing. It leverages the complementary strengths of traditional analytical methods and key operations from state-of-the-art methods, e.g., patch-wise parallel processing, a key concept in deep learning, to focus on small spatial regions and so leverage locally informative relationships that do not generalise over a whole dataset. P2SR's parallel patch-wise processing framework significantly reduces computational overhead, making it scalable to large datasets and suitable for near real-time applications, which is a notable limitation of both traditional iterative algorithms and deep learning models with high inference latency.

2. Study Areas and Dataset Description

2.1. Study Areas

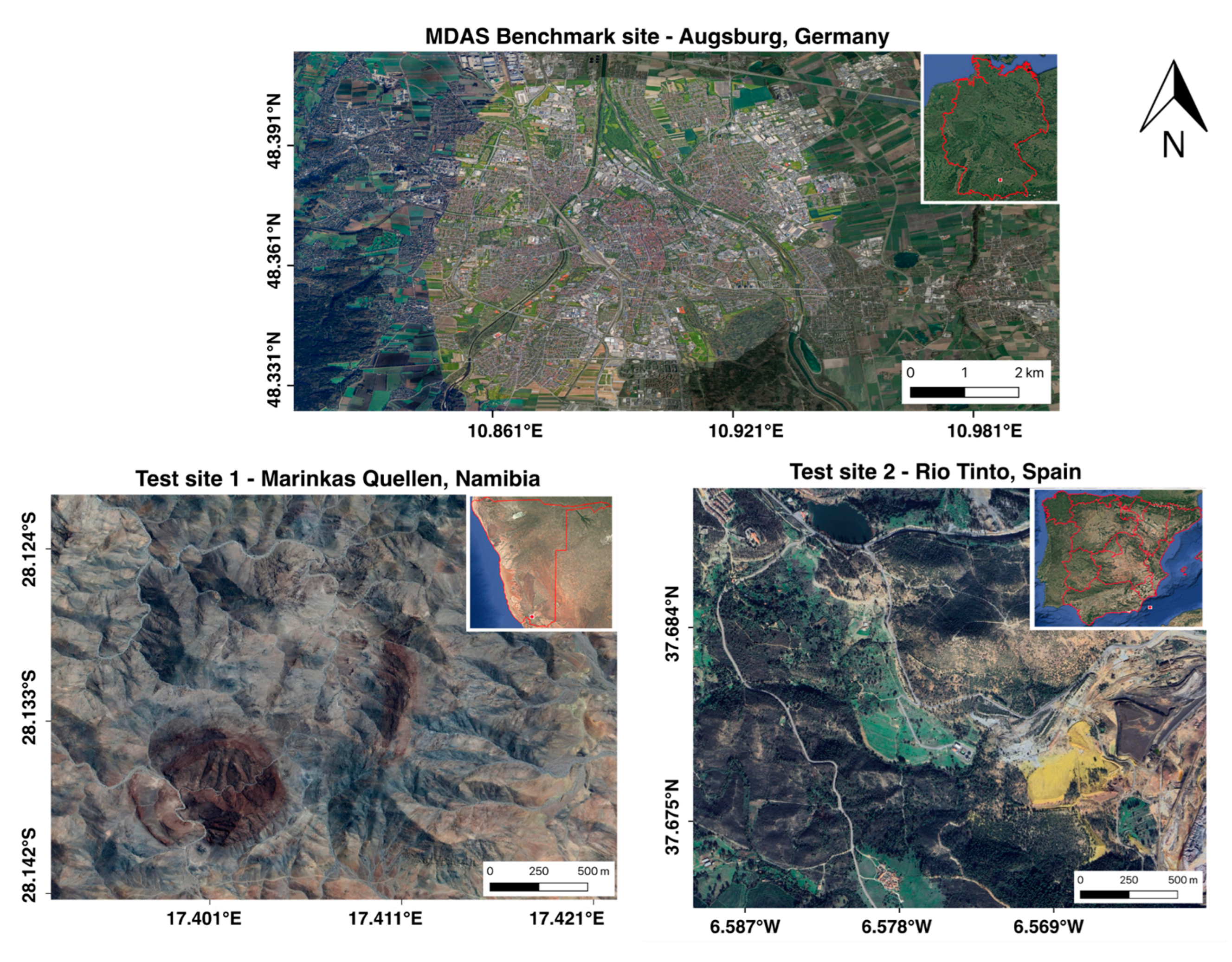

A total of three study sites, including a benchmark site and two test sites with distinct geo-characteristics were selected to evaluate the proposed method. The benchmark site covers an area in the city of Augsburg, Germany. The other two test sites are located in Spain and Namibia, and have been previously studied from a geological and ecological perspective, allowing us to evaluate application-specific aspects of the proposed resolution enhancement approach [

27,

28].

The test site-1 is located in the Marinkas-Quellen region of Southern Namibia. The area has an arid environment with limited vegetation and extensive bedrock exposure. Combined with limited seasonal variation and low population density, Marinkas-Quellen is an ideal location for testing the proposed method for large-scale geological mapping. The area hosts significant critical raw materials, including geologically interesting Rare Earth Elements (REE) bearing carbonatites [

29].

The test site-2 is located at Rio-Tinto, north of Huelva in the Iberian Pyrite Belt (IPB), Spain, a geologically significant region due to its endowment in massive sulphide copper ores and a mining history that dates back to pre-Roman times. The rocks of the Rio-Tinto area are intensely altered by low-grade hydrothermal activity associated with mineralization and regional metamorphism. These alteration minerals provide distinct spectral signatures that can be effectively detected and analyzed using HSI, to help locate previously undiscovered ore deposits. The area's extensive mining history has also led to widespread anthropogenic land cover changes, including environmentally damaging disturbances and mine wastes [

30]. Hyperspectral studies in this region can thus also help to effectively monitor and manage this legacy through the quantification of vegetation health and mapping of hazardous (acid-creating) mine wastes. The location and the extent of both the study areas are shown in

Figure 2.

2.2. Multi-Modal Benchmark Dataset

We use a benchmark HSI-MSI dataset to ensure a standardized evaluation and comparison of results with state-of-the-art methods. We selected the benchmark MDAS dataset [

31] for the city of Augsburg, Germany. The dataset was specially devised to test multiple remote sensing applications including methods for hyperspectral resolution enhancement. The dataset is unique as compared to contemporary datasets as most of them only emphasize spatial resolution, whereas MDAS claims to challenge the algorithms for spectral enhancement, instrumental effects and environmental impact. The original dataset is constructed with multi-modality - SAR data, multispectral image, HSI, DSM, and geographic data. We used the HSI acquired by the German Aerospace Center (DLR) using the HySpex airborne imaging spectrometer system. The HySpex HSI covers a spectral range of 416 to 992 nm with 160 channels and 256 channels covering a spectral range of 968 to 2498 nm using the HySpex VNIR-1600 and SWIR-320m-e sensors respectively. We also used the MDAS MSI, which is the Sentinel-2 bottom of atmosphere (BOA) reflectance and geocoded in WGS 84/UTM zone 32 N. It has 12 spectral bands with wavelengths ranging from 440 to 2200 nm. The final image is cropped to the ROI, resulting in a size of 1371×888 pixels.

2.3. Satellite and Airborne Remote Sensing Datasets for the Test-Sites

The tested satellite remote sensing datasets included co-registered HSI and MSI for the two test sites (Marinkas and Rio-Tinto). We used the EnMAP HSI with Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope MSI for the implementation of our proposed method. EnMAP captures HSI across visible, near-infrared (VNIR), and shortwave infrared (SWIR) ranges (420–2450 nm) with over 240 spectral bands. The ground sampling distance (GSD) is 30 m per pixel, with a 30 km swath width, enabling both broad and targeted data acquisition. The sensor achieves a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) greater than 500 (VNIR) and 150 (SWIR) at reference radiance, ensuring high radiometric quality with an accuracy of ≤ 5% and a 14-bit dynamic range. We used the Level-2A (surface reflectance with atmospheric correction) data, although it is also delivered in Level-1B (at-sensor radiance) and Level-1C (orthorectified radiance).

The high-resolution airborne HSI for the Rio-Tinto area were acquired using the HySpex sensor (as part of the EU Horizon project, INFACT under grant agreement nº 776487). An empirical line correction (ELC) was performed to convert the geo-rectified HySpex radiance data into relative reflectance, before resampling to 2 m spatial resolution. The ELC model was fit to target ground reflectance measurements acquired with a FieldSpec Spectral Evolution handheld spectroradiometer during the airborne acquisition. The airborne HSI for the Marinkas-Quellen area was acquired using the HyMap sensor from a height of 2000 m, resulting in a 5 m spatial sampling. Geometric and radiometric corrections were conducted by the HyVista Corporation, which acquired the data. Atmospheric correction was performed using a continental aerosol model and a mid-latitude summer atmospheric model, with an ozone count of 340 ppm and a 75 km visibility, to estimate ground reflectance. We used these high-resolution airborne data as a means to validate the satellite HSI resolution enhancement results.

The satellite MSI consists of Sentinel-2 data that captures data across 13 spectral bands, ranging from the visible (VIS) and near-infrared (NIR) to the shortwave infrared (SWIR), with GSD ranging between 10 m and 60 m. Out of the 13, we used 10 spectral bands at 10 m GSD (VIS, Red Edge, NIR and SWIR). The high radiometric performance is ensured with a 12-bit dynamic range and is available at multiple processing levels of which Level-2A (bottom-of-atmosphere reflectance with atmospheric correction) was used in the experiments. The Planetscope MSI was captured by Planet Labs with 8-spectral bands (VIS, Red Edge and NIR) at 3 m spatial resolution. We used the Level-3B ortho-rectified scaled surface reflectance 8-band image. Some key specifications and details of the HSI and MSI datasets used for this study are given in

Table 1.

3. Proposed Method and Experimental Setup

3.1. Parallel Patch-Wise Sparse Residual Learning (P2SR) Method

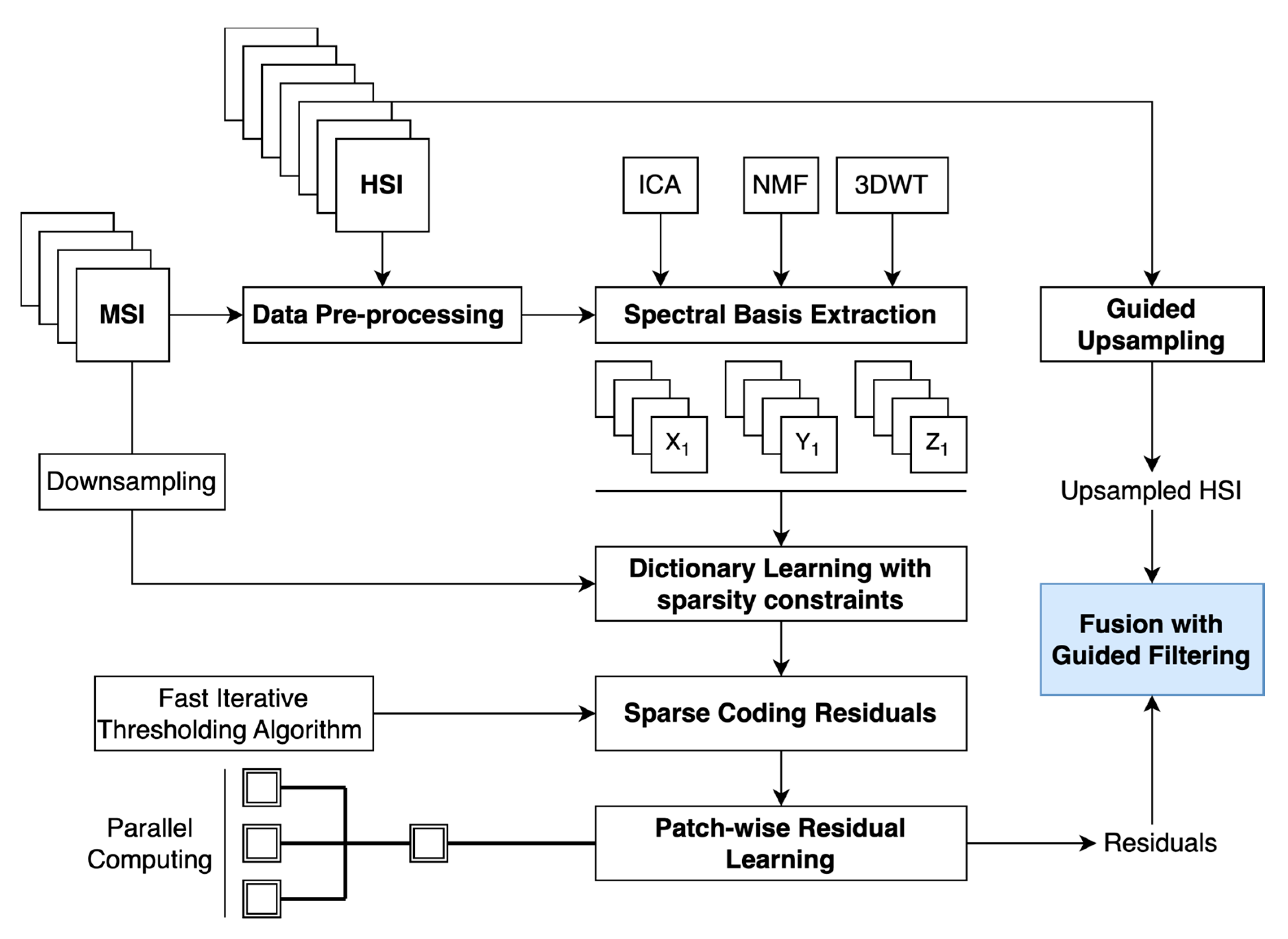

The proposed P2SR method employs a multi-stage approach that combines sparse coding and residual learning to generate HSI with higher spatial resolution (i.e. GSD) by fusion of low-resolution HSI and high-resolution MSI. P2SR is an organized approach that sequentially ensures consistency of data (through systematic pre-processing), captures diverse spatio-spectral features (via multi-decomposition), effectively fuses spatio-spectral features (with dictionary learning and sparse coding) and reconstructs high resolution HSI (using first order optimization and guided filtering) with easy and accelerated deployment (using parallel computing). These steps are described in detail in the following paragraphs of this subsection.

In the first stage, HSI and MSI data are preprocessed to address nan values, invalid bands and data gaps to ensure overall data integrity. The MSI is downsampled to align with the HSI’s resolution, and adaptive patch sizes and strides are calculated based on data dimensions (height and width) to enable efficient regional processing. A set of selected decomposition techniques— 3D-wavelet transforms (3DWT), Independent component analysis (ICA), and Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) are employed to extract spectral and spatial features from the HSI, creating a rich set of components that encapsulate the underlying data structure. The proposed P2SR method integrates these decomposition methods with their unique advantages: ICA isolates statistically independent spectral signatures and emphasizes variance, NMF enforces non-negativity for improved interpretability with localized features and 3DWT isolates multi-scale spectral patterns in the HSI data. The method applies each decomposition separately to the low-resolution hyperspectral patches to effectively utilize these complementary strengths. These patches provide a robust representation of the spatial and spectral content, allowing the model to learn high-frequency spatial details effectively.

The spectral bases extracted through multi-decompositions are crucial in forming a sparse dictionary that encodes the locally relevant spectral information. In the second stage, a dictionary (see supervised dictionary learning [

32]) is trained using a combination of downsampled MSI patches and spectral components extracted from the HSI through multiple decompositions. The goal of this dictionary is to capture the spectral characteristics of different materials present in the patch, while also accommodating the spatial details provided by the MSI. By leveraging both sources of information—low spatial resolution data from the HSI and relatively higher spatial resolution data from the MSI—the dictionary is constructed to be representative of the high-resolution hyperspectral space, enabling accurate super-resolution reconstruction. The next step is to utilize it for sparse coding, where each patch of the low-resolution HSI is represented as a linear combination of a few dictionary atoms. The patch-wise approach makes sparse coding faster and more accurate as each patch consists of only a few distinct materials. Sparse coding is based on the principle of sparsity, which assumes that natural signals can be efficiently represented using a small number of meaningful basis elements. It helps to suppress noise and irrelevant information while preserving the critical spectral structures necessary for reconstruction. However, the challenge in sparse coding is to determine the optimal sparse representation and optimally enforce sparsity constraints. Therefore, we employ the Fast Iterative Shrinkage-Thresholding Algorithm (FISTA) [

33] to solve this optimization problem. FISTA accelerates sparse reconstruction due to its fast convergence and ensures that the learned dictionary is utilized effectively to recover high-resolution hyperspectral details while avoiding overfitting or introducing artefacts. As a result, the final sparse representation of each hyperspectral patch is well-structured, preserving the essential spectral characteristics of the original scene while benefiting from the enhanced spatial resolution provided by the MSI. This combination of dictionary learning and sparse coding enables a highly effective fusion of MSI and HSI, leading to superior resolution enhancement with minimal spectral distortion.

The last stage produces a final reconstructed and resolution enhanced HSI with guided filtering, applied for leveraging the MSI bands as a structural reference to increase the spatial fidelity while minimizing artefacts. This step ensures that both fine spectral details extracted from the learned dictionary, and the global spatial structure of the original HSI are retained. This systematic multi-stage process ensures that the resolution enhanced HSI achieves an improved spatial resolution while preserving spectral integrity, making it suitable for high-precision remote sensing applications. These multiple stages are encapsulated in a parallel computing framework that enhances computational efficiency, especially given the high-dimensional nature of hyperspectral data. The method was implemented on a HPC system and the distributed computing on multiple nodes accelerated the end-to-end process making it reliable for near-real-time hyperspectral resolution enhancement and scalable for large datasets. Additionally, efficient memory management techniques are employed to handle the substantial data load while minimizing computational overhead. The flowchart for the implementation of the method is shown in

Figure 3.

3.2. Experimental Setup and Evaluation Strategies

The experiments are organized to perform HSI spatial resolution enhancement in diverse terrain conditions and at multiple spatial levels. The proposed P

2SR method and a few selected state-of-the-art (SOA) / established methods are implemented for the enhancement of EnMAP data from 30 m to 10 m spatial resolution using Sentinel-2 data and to 3 m spatial resolution using PlanetScope data. The five selected methods for comparison are :- 1) Bicubic interpolation (Bicubic), 2) Hyperspectral Super-resolution (c-HySure (c-Hysure is a custom python implementation of Hysure method [

7] with original MATLAB code:

https://github.com/alfaiate/HySure)) [

7] 3) Coupled non-negative matrix factorization (CNMF (CNMF source code:

https://naotoyokoya.com/assets/zip/CNMF_Python.zip)) [

6], 4) Residual Two-stream Fusion Network (ResTFNet (ResTFNet source code:

https://github.com/liouxy/tfnet_pytorch)) [

25] and 5) Spatial–Spectral Reconstruction Network (SSRNet (SSRNet source code:

https://github.com/hw2hwei/SSRNET)) [

34]. These methods are prominently used for comparative evaluation and are reproducible with open source codes. All methods (except bicubic) are based on HSI-MSI fusion which makes them suitable for comparison with the proposed method.

The proposed P2SR method is evaluated using a combination of quantitative metrics and qualitative assessment. Quantitative metrics used for the evaluation of enhanced HSI are - Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM), Erreur Relative Globale Adimensionnelle de Synthèse (ERGAS) and Universal Image Quality Index for n-bands (Q2n). PSNR is a simple and widely used metric that measures reconstruction quality but is not always correlated with visual perception. SAM measures spectral distortion between the reference and reconstructed HSI. ERGAS measures global relative reconstruction error across all bands and Q2n is a multi-band extension of structural similarity measure (SSIM) that measures covariance between reference and re-constructed HSI depicting preservation of structural information. We also use a benchmark dataset (MDAS) with known high-resolution ground truth that allows for objective comparisons with other SOA methods (with open-source codes) and ensures generalization. The 10 m enhanced HSI products delivered from five SOA methods and the proposed P2SR method are evaluated using the assessment metrics for all three datasets. These metrics are computed for enhanced HSI against a high-resolution reference HSI captured with airborne sensors. P2SR method is then used to produce 3 m-enhanced HSI products for Marinkas-Quellen and Rio-Tinto to make a qualitative and application-oriented assessment. The qualitative assessment includes minimum wavelength maps, band-index inspection, spectral profile consistency checks and identifying interesting geological enhanced structures.

4. Results

4.1. Metrics Based Assessment of Enhanced Hyperspectral Products

The 10 m enhanced products were evaluated using PSNR, SAM, ERGAS and Q2n metrics for all three study sites (

Table 2). These scores indicate that the proposed P

2SR method outperforms all considered SOA / established methods on all metrics for all datasets, except for the Q2n metric in Rio-Tinto, where SSR-Net has the highest Q2n score. This indicates the robust nature of P

2SR when exposed to different terrain conditions and the accurate reconstruction of HSI across diverse land features. The fact that P

2SR achieves the best PSNR and SAM scores for all datasets indicates a stable performance in simultaneously maintaining the spatial and spectral quality of enhanced HSI in diverse scenarios. Although, high PSNR does not always guarantee spectral fidelity, and this is distinctly observed for CNMF which achieves high PSNR scores close to the P

2SR method but low SAM scores indicate inaccuracies in spectral reconstruction. Similarly, ResTFNet delivered better SAM scores as compared to CNMF indicating better spectral reconstruction but lower PSNR, suggesting inaccuracies in spatial reconstruction.

The proposed P2SR method also outperforms all methods in terms of ERGAS score, indicating robustness in relative spatio-spectral reconstruction (not only pixel-wise errors) and independence on the reflectance distribution of the original HSI. This difference can be observed between CNMF and deep learning methods (ResTFNet and SSR-NET) where there is high difference in the average PSNR scores (dependent on reflectance distribution) but the difference reduces in average ERGAS scores indicating compromised performance of deep learning methods due to high variations in HSI reflectance. Also, among the two deep learning models, SSR-NET achieves a better average ERGAS score than ResTFNet indicating better spatio-spectral reconstruction for uniform distribution of reflectance values but non-uniform distribution (such as in most realistic scenarios), SSR-NET has a better spatial reconstruction (better PSNR score) and ResTFNet has a better spectral reconstruction (better SAM score). In terms of universal image quality aspects such as luminance and contrast (along with structural similarity), the P2SR method performs better than all methods, except for the Rio-Tinto area where SSR-NET achieves a slightly better Q2n score. This could be attributed to the complex and dynamic features around mining areas.

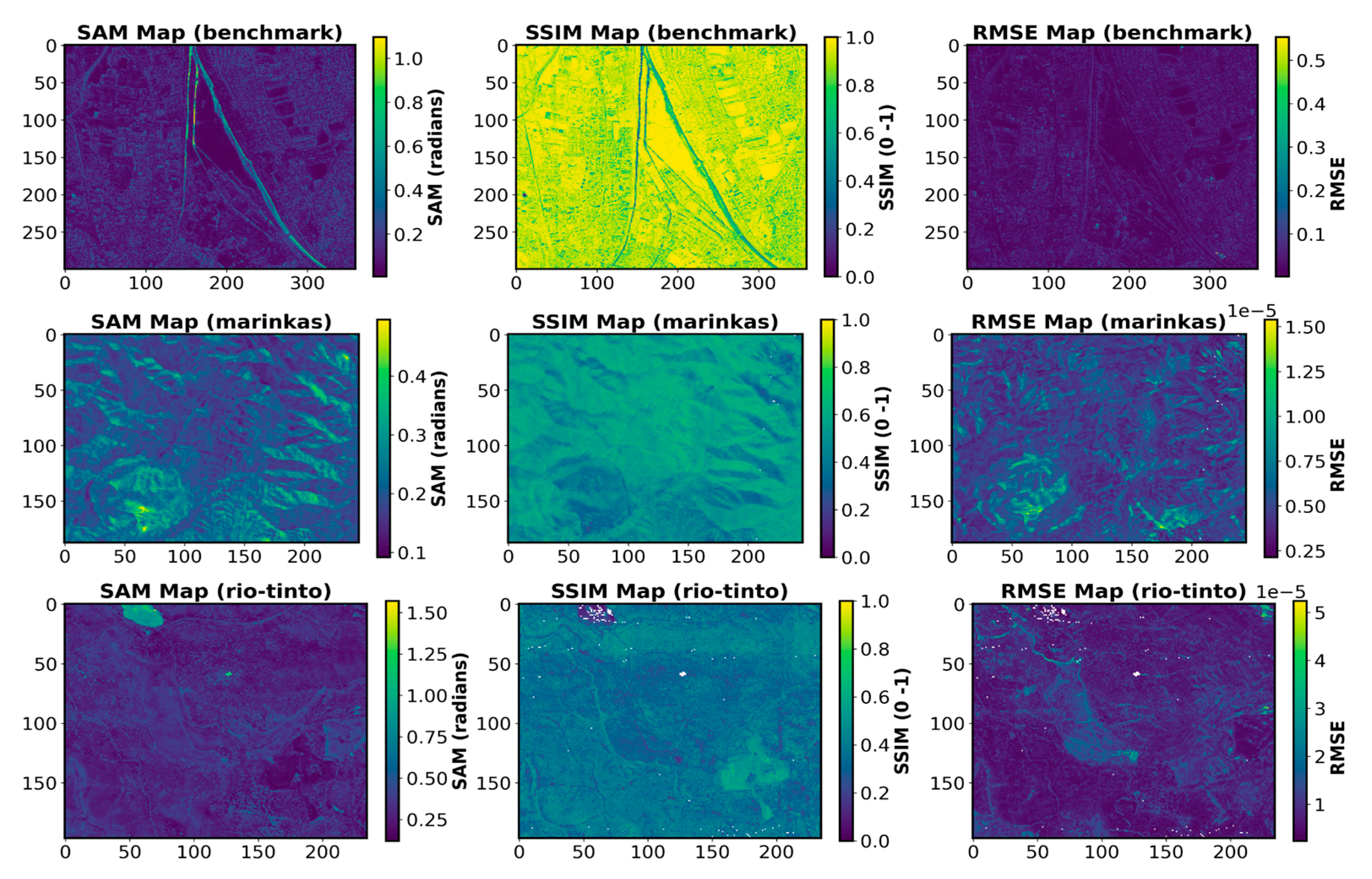

The visual maps of SAM, SSIM and RMSE metrics produced with the P

2SR method for all three sites are shown in

Figure 4. The SAM map shows that errors in spectral reconstruction are localized for specific features such as water-bodies and irregular topography. The SSIM and RMSE maps also render high confidence in spatial reconstruction of diverse terrain features facilitating finer detection of structural and environmental variables. Overall, the P

2SR method provides accurate results proving its ability to overcome sensor limitations in the enhancement process and reduces mixed pixels precisely through decomposition of original pixels in a resource efficient manner (low-data requirements and high computational speeds).

4.2. Qualitative Spatial Assessment of Enhanced Hyperspectral Products

The proposed P

2SR method delivers enhanced HSI data with qualitative results that complement the quantitative metrics with spatially sharper and consistent features.

Figure 5 shows false color composite (FCC) patches of original 30 m EnMAP data with 10 m enhanced EnMAP. Urban features are spatially sharper and the mixed pixels are resolved to produce distinct edges. The water features and bridges are reconstructed with finer boundaries with land features. The Marinkas site shown in

Figure 6 shows similarly enhanced EnMAP patches at 10 m and 3 m. The FCC patches show spatial regions with uniform material maintain their spectral consistency at both 10 m and 3 m. The FCC visualization of SWIR wavelengths indicates controlled noise with smooth and sharp spatial transitions.

4.3. Application-Oriented Assessment of Enhanced HSI Products

The application-oriented assessment in Rio-Tinto is divided into two blocks as shown in

Figure 7. The prominent feature (highlighted in the red bounding box) in

Figure 7a, identified as transported mine waste, exhibits well-defined and sharper boundaries in the enhanced HSI products. This region is also spectrally distinct due to its strong Fe²⁺ absorption feature between 800 nm and 1200 nm. Spectral analysis of the enhanced products confirms that they retain this spectral information with minimal variation. This site is particularly significant due to its diverse land cover and geologically important spectral features. A spectral index analysis was carried out to further evaluate the enhanced products. Three spectral indices were considered: kaolinite (

), NDVI (

), and Fe3+ index (

) and an RGB composite of the results was generated. In

Figure 7b, sparse vegetation in kaolinite-rich soil appears yellow, while magenta spots indicate areas of bare soil with Fe-rich clay. The enhanced products preserve and effectively amplify these subtle spectral variations while spatially enhancing roads and other distinct features.

Marinkas-Quellen is a geologically complex site with minimal vegetation cover. Significantly, the enhanced HSI products reveal finer geological structures that are entirely absent in the original coarser 30 m HSI data. In the true-colour composite of the enhanced 3 m HSI product, distinct foliation and/or bedding patterns are clearly visible, as highlighted by the yellow bounding box in

Figure 8a. The primary spectral signatures in this region are observed in the SWIR, particularly from carbonates and clays. Further analysis of the enhanced products using minimum wavelength mapping (MWL) in the SWIR domain shows significantly improved clarity in geological demarcations (

Figure 8b). Broadly, shades ranging from green to cyan (2325 nm to 2335 nm) indicate carbonate-bearing lithotypes, while darker blue (~2340 nm) signifies the presence of Mg-OH in alteration. Additionally, a small dyke-like feature is apparent in the enhanced products (most prominent at 3 m), marked by reddish tones in the MWL, suggesting the presence of a Fe-OH absorption feature around 2250 nm.

5. Discussion

This paper presents P

2SR- a multi-stage sparse residual learning approach compatible with a parallel computing framework for fast and accurate hyperspectral resolution enhancement. Our approach maintains consistent performance across benchmark and test datasets. This performance can be attributed to the hybrid approach that integrates strengths of different machine learning and statistical methods for HSI enhancement. A key element of the proposed approach is the patch-wise processing operation that allows locally-relevant but globally trivial relationships to be leveraged for resolution enhancement. The studies that performed HSI-MSI fusion within a sparse coding framework [

35,

36,

37] reported concerns on spectral distortion due to high-frequency spatial information from auxiliary MSI data that corrupts spectral fidelity. Our method presents a robust process of constraining noise at various stages of the enhancement process which leads to accurate 3x as well as 10x super-resolved EnMAP products. The FISTA and guided filtering integrated at different levels of implementation provide regularization and thresholding of information getting injected in the enhanced HSI.

Moreover, deep learning architectures have demonstrated improvements in HSI enhancement by capturing complex spatial and spectral relationships. In spite of successive evolution of deep architectures such as 3D CNNs for spatio-spectral features [

38], RNNs that model spectral dependencies across bands [

39] and Transformers that learn priors of HSI [

40], the central problem of massive and diverse training data requirements limits their performance. This also includes limitations that primarily stem from sensor characteristics that cause spectral response mismatch and spatial resolution variability while training the deep models. This may cause performance loss especially for new generation hyperspectral sensors devised for specific applications with different spectral alignment and noise patterns. The proposed method reduces reconstruction errors by integrating select robust mechanisms from deep architectures, such as patch-wise processing and sliding window for local feature learning, extraction of hierarchical feature maps using multiple-decomposition, sparse representations, and residual learning. Lastly, similar to the distributed training of deep models, our method incorporates parallel computations of multi-core processors for scalability and speed.

Although our method outperforms other methods on most metrics, there is scope for improvement in the integrated stages of the method in terms of generalization, efficiency and performance. We implemented a process for adaptive patch size and stride selection but a poor selection can lead to loss of fine spatial details (e.g., excessively smaller patches may lose contextual information and larger patches may smooth out high frequency details). Another limitation stems from dictionary learning that may cause spectral distortions in regions with complex distribution of diverse land features. Though we have regulated sparse coding of residuals through FISTA to mitigate such errors, there could be separate dictionaries constructed for different frequency scales to avoid the distortions in such rare instances. In addition, the proposed method also needs to be tested for temporal robustness and more dynamic environmental conditions. To achieve similar accuracy of results for enhancing temporal datasets, a dynamic dictionary update mechanism may be required.

6. Conclusion

The proposed P2SR method demonstrates a robust and effective approach for HSI enhancement, consistently outperforming SOA methods across multiple quantitative and qualitative evaluations. The metric-based assessment reveals that P2SR achieves superior performance in terms of PSNR, SAM, and ERGAS across diverse terrains, indicating its ability to balance spatial and spectral accuracy effectively. Although SSR-Net slightly surpasses P2SR on the Q2n metric in the Rio-Tinto dataset, the overall results confirm P2SR's stability and precision in reconstructing high-resolution HSI under varying terrain conditions. The qualitative spatial assessments further validate these findings, showing sharper spatial features, reduced mixed pixels, and improved structural integrity across different resolutions (10 m and 3 m). Moreover, the application-oriented assessment highlights P2SR’s ability to preserve and enhance critical spectral signatures in geologically complex regions, as seen in the identification of Fe²⁺ absorption features and the detection of fine-scale geological structures. The method’s ability to maintain spectral fidelity while enhancing spatial details ensures its applicability in real-world scenarios, including mineral mapping, vegetation analysis, and land-use classification. With its efficient decomposition strategy and parallel processing framework, P2SR provides an advanced, scalable solution for enhancing HSI, bridging the gap between sensor limitations and the demand for high-resolution spectral data in remote sensing applications.

Funding

This research is funded by Open projects at Center for Advanced Systems Understanding at Helmholtz Zentrum Dresden Rossendorf.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Open Projects programme of the Center for Advanced Systems Understanding (Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf) for the support and funding of this project. The EnMAP Level 2A data was provided by the German Aerospace Center (DLR) under proposal number - A00001-P00375. We also thank Planet Labs PBC. for providing the PlanetScope data accessed under the Education and Research Program - PlanID 748533.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Shah, V. P.; Younan, N. H.; King, R. L. An Efficient Pan-Sharpening Method via a Combined Adaptive PCA Approach and Contourlets. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2008, 46, 1323–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelének, J.; Kopačková, V.; Koucká, L.; Mišurec, J. Testing a Modified PCA-Based Sharpening Approach for Image Fusion. Remote Sensing, 2016, 8, 794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Mura, M.; Vivone, G.; Restaino, R.; Addesso, P.; Chanussot, J. Global and Local Gram-Schmidt Methods for Hyperspectral Pansharpening. 2015 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), 2015. [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Li, Y.; Dong, W. A New Hyperspectral Pansharpening Method Based on Guided Filter. 2017 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), 2017, 5125–5128. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Xiao, S.; Li, Y. Hyperspectral Pansharpening Based on Guided Filter and Gaussian Filter. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation, 2018, 53, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoya, N.; Yairi, T.; Iwasaki, A. Coupled Nonnegative Matrix Factorization Unmixing for Hyperspectral and Multispectral Data Fusion. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2012, 50, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes, M.; Bioucas-Dias, J.; Almeida, L. B.; Chanussot, J. A Convex Formulation for Hyperspectral Image Superresolution via Subspace-Based Regularization. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2015, 53, 3373–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmak, H.; Akar, G. B.; Yuksel, S. E. A MAP-Based Approach for Hyperspectral Imagery Super-Resolution. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 2018, 27, 2942–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmak, H.; Akar, G. B.; Yuksel, S. E.; Aytaylan, H. Super-Resolution Reconstruction of Hyperspectral Images via an Improved MAP-Based Approach. 2016 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), 2016, 7244–7247. [CrossRef]

- Akgun, T.; Altunbasak, Y.; Mersereau, R. M. Super-Resolution Reconstruction of Hyperspectral Images. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 2005, 14, 1860–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Shen, H. A Super-Resolution Reconstruction Algorithm for Hyperspectral Images. Signal Processing, 2012, 92, 2082–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Bi, T.; Shi, Y. A Frequency-Separated 3D-CNN for Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Access, 2020, 8, 86367–86379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Hong, Y.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y. A Super-Resolution Convolutional-Neural-Network-Based Approach for Subpixel Mapping of Hyperspectral Images. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2019, 12, 4930–4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lee, J. An Efficient Residual Learning Neural Network for Hyperspectral Image Superresolution. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2019, 12, 1240–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Bai, X.; Tang, W.; Lei, P.; Zhou, J. Deep Residual Convolutional Neural Network for Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2017, 370–380. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Hou, J.; Chen, J.; Zeng, H.; Zhou, J. Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution via Deep Progressive Zero-Centric Residual Learning. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, 2021, 30, 1423–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, S.; Feng, Y.; Mei, S.; Jia, S.; Du, Q. Hyperspectral Imagery Spatial Super-Resolution Using Generative Adversarial Network. IEEE Transactions on Computational Imaging, 2021, 7, 948–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, X.; Jing, L.; Tang, Y.; Li, H.; Xiao, Z.; Ding, H. HyperGAN: A Hyperspectral Image Fusion Approach Based on Generative Adversarial Networks. Remote Sensing, 2024, 16, 4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Kang, X.; Fan, S. Multilevel Progressive Network With Nonlocal Channel Attention for Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2022, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.-F.; Huang, T.-Z.; Deng, L.-J.; Jiang, T.-X.; Vivone, G.; Chanussot, J. Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution via Deep Spatiospectral Attention Convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 2022, 33, 7251–7265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, J.; Gao, X.; Zhang, J. ESSAformer: Efficient Transformer for Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution. 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2023, 23016–23027. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Kang, X.; Luo, J.; Fan, S. Interactformer: Interactive Transformer and CNN for Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2022, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniarz, J.; Cerra, D.; Avbelj, J.; Reinartz, P.; Müller, R. Hyperspectral Image Resolution Enhancement Based On Spectral Unmixing and Information Fusion. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, 2012, XXXVIII-4/W19, 33–37. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; He, H.; Chen, N.; Kang, X.; Wang, B. SLRCNN: Integrating Sparse and Low-Rank with a CNN Denoiser for Hyperspectral and Multispectral Image Fusion. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 2024, 134, 104227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y. Remote Sensing Image Fusion Based on Two-Stream Fusion Network. Information Fusion, 2020, 55, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, J.; Yuan, Q.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, L. Physics-Based GAN With Iterative Refinement Unit for Hyperspectral and Multispectral Image Fusion. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2021, 14, 6827–6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booysen, R., Jackisch, R., Lorenz, S., Zimmermann, R., Kirsch, M., Nex, P. A., & Gloaguen, R. Detection of REEs with lightweight UAV-based hyperspectral imaging, Scientific Reports, 2020, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Thiele, Samuel T., Sandra Lorenz, Moritz Kirsch, I. Cecilia Contreras Acosta, Laura Tusa, Erik Herrmann, Robert Möckel, and Richard Gloaguen. Multi-scale, multi-sensor data integration for automated 3-D geological mapping, Ore Geology Reviews, 2021, 136 (2021): 104252. [CrossRef]

- Smithies, R. H., & Marsh, J. S. The Marinkas Quellen Carbonatite Complex, southern Namibia; carbonatite magmatism with an uncontaminated depleted mantle signature in a continental setting, Chemical Geology, 1998, 148(3-4), 201-212. [CrossRef]

- Salkield, L. U. A Technical History of the Rio Tinto Mines: Some Notes on Exploitation from Pre-Phoenician Times to the 1950s; Cahalan, M. J., Ed.; Springer Netherlands, 1987. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, R.; Hong, D.; Camero, A.; Yao, J.; Schneider, M.; Kurz, F.; Segl, K.; Zhu, X. X. MDAS: A New Multimodal Benchmark Dataset for Remote Sensing. Earth System Science Data, 2023, 15, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairal, J., Ponce, J., Sapiro, G., Zisserman, A., & Bach, F.. Supervised Dictionary Learning. In D. Koller, D. Schuurmans, Y. Bengio, & L. Bottou (Eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2008 (Vol. 21). Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2008/file/c0f168ce8900fa56e57789e2a2f2c9d0-Paper.pdf.

- Beck, A.; Teboulle, M. A Fast Iterative Shrinkage-Thresholding Algorithm for Linear Inverse Problems. SIAM Journal on Imaging Sciences, 2009, 2, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, W.; Wang, Q.; Li, X. SSR-NET: Spatial–Spectral Reconstruction Network for Hyperspectral and Multispectral Image Fusion. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2021, 59, 5953–5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadou, K.; Tsagkatakis, G.; Tsakalides, P. Spectral Super Resolution of Hyperspectral Images via Coupled Dictionary Learning. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 2019, 57, 2777–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yuan, Q.; Shen, H.; Meng, X.; Zhang, L. Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution by Spectral Mixture Analysis and Spatial–Spectral Group Sparsity. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters, 2016, 13, 1250–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

P.V., A.; B., K. M.; A., P. Spatial-Spectral Feature Based Approach towards Convolutional Sparse Coding of Hyperspectral Images. Computer Vision and Image Understanding, 2019, 188, 102797. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, W.; Ma, Q.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J. Rethinking 3D-CNN in Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution. Remote Sensing, 2023, 15, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liang, Z.; You, S. Bidirectional 3D Quasi-Recurrent Neural Network for Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing, 2021, 14, 2674–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, C.; Lu, C.; Zhan, T. HCT: A Hybrid CNN and Transformer Network for Hyperspectral Image Super-Resolution. Multimedia Systems, 2024, 30. [CrossRef]

- “Planet Team (2025). Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth. San Francisco, CA”. Available online: https://api.planet.com.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).