1. Introduction

The digital age has brought a tremendous demand for high-speed Internet services, fueling the search for efficient traffic management and optimization strategies. One critical branch of this effort is the accurate identification and classification of low-latency Internet traffic. Low-latency in networking refers to transmitting data with a low end-to-end delay, typically defined as under 100 milliseconds (ms) for real-time applications such as video conferencing or online gaming [

1]. In mission-critical systems like autonomous vehicles or financial trading, thresholds may be further reduced to 1–10 ms to ensure seamless responsiveness [

2,

3]. However, understanding the nature of the application, including whether it requires bidirectional or unidirectional traffic, is crucial for accurate classification. To address these needs, our approach utilizes Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) combined with wavelet-transformed temporal features such as throughput, slope, ratio, and moving averages to accurately identify and classify low-latency Internet traffic. This integration allows our model to capture the underlying dynamics of network traffic, enabling a more refined and precise classification. This AI-driven method not only provides a robust framework for near real-time classification, but also highlights the importance of advanced techniques in modern network management.

Identification of low-latency Internet traffic is essential to ensure that these applications operate seamlessly. Although latency is generally measured in milliseconds, the acceptable thresholds for low-latency applications vary depending on the use case [

4,

5]. To identify low-latency Internet traffic, several methods and tools are used, including real-time monitoring [

6] and statistical analysis of network performance [

7]. Additionally, Quality of Service (QoS) parameters [

8] serve as key indicators for assessing latency. By consistently monitoring and assessing network performance in real-time, low-latency traffic can be detected, and network resources can be allocated accordingly to ensure a smooth user experience. Streaming platforms like Netflix or YouTube continuously monitor network performance to adjust streaming quality based on available bandwidth. Algorithms dynamically allocate resources, ensuring smooth playback without buffering interruptions [

9].

In the context of managing low-latency Internet traffic, it becomes essential to understand the complex nature of data flows within networks. As we explore in our methodology, low-latency traffic shares characteristics similar to Gaussian noise, displaying organized patterns that can be modeled using signal processing techniques. In conjunction with wavelet transforms, features such as throughput, slope, and moving averages provide additional layers of insight, allowing us to track data flow fluctuations and packet exchange rates that are essential for distinguishing low-latency traffic from other forms. These traffic patterns can be effectively analyzed using methods such as wavelet transforms, offering valuable insight into the noise-like nature of data exchange. This analogy provides a foundation for our classification model, as detailed in the methodology section.

Much like noise reduction techniques in signal processing, where advanced algorithms and filters are employed to extract the pertinent signal from the surrounding noise [

10,

11], a variety of tools and methodologies are also implemented to classify [

12] and identify [

6] low-latency traffic. By recognizing the organized ’noise’ generated by the consistent bidirectional flow of small packets, this unique traffic pattern can be distinguished from other network traffic. This distinction enables us to allocate the necessary resources and bandwidth to users for low-latency applications, ensuring real-time responsiveness and quality.

The challenge in this case is to develop a sophisticated and robust system capable of distinguishing this unique form of ’noise’ from the ’signal’ with precision and consistency. One powerful tool in this effort is the use of wavelet transforms. The wavelet transform (WT) is a mathematical technique widely used in signal processing and data analysis [

13]. WT provides the ability to decompose a signal into its component frequency and time domain elements, offering a fine-grained view of the data. In the context of low-latency traffic, wavelet transforms can be utilized to identify characteristic patterns within the bidirectional flow of small packets. By analyzing the high-frequency components that correspond to rapid packet exchanges, automated tools can effectively isolate and differentiate low-latency ’noise’ from the broader network ’signal’ [

14]. This level of granularity enables the precise identification, classification, and prioritization of low-latency traffic, contributing to a more responsive and efficient network environment. Furthermore, wavelet transforms offer the advantage of adaptability, as they allow the selection of different wavelet functions and scales to match the specific characteristics of the traffic under examination. This adaptability makes wavelet transforms a valuable tool for not only recognizing low-latency traffic but also for continuously monitoring and adjusting network resources to ensure the optimal delivery of time-sensitive applications.

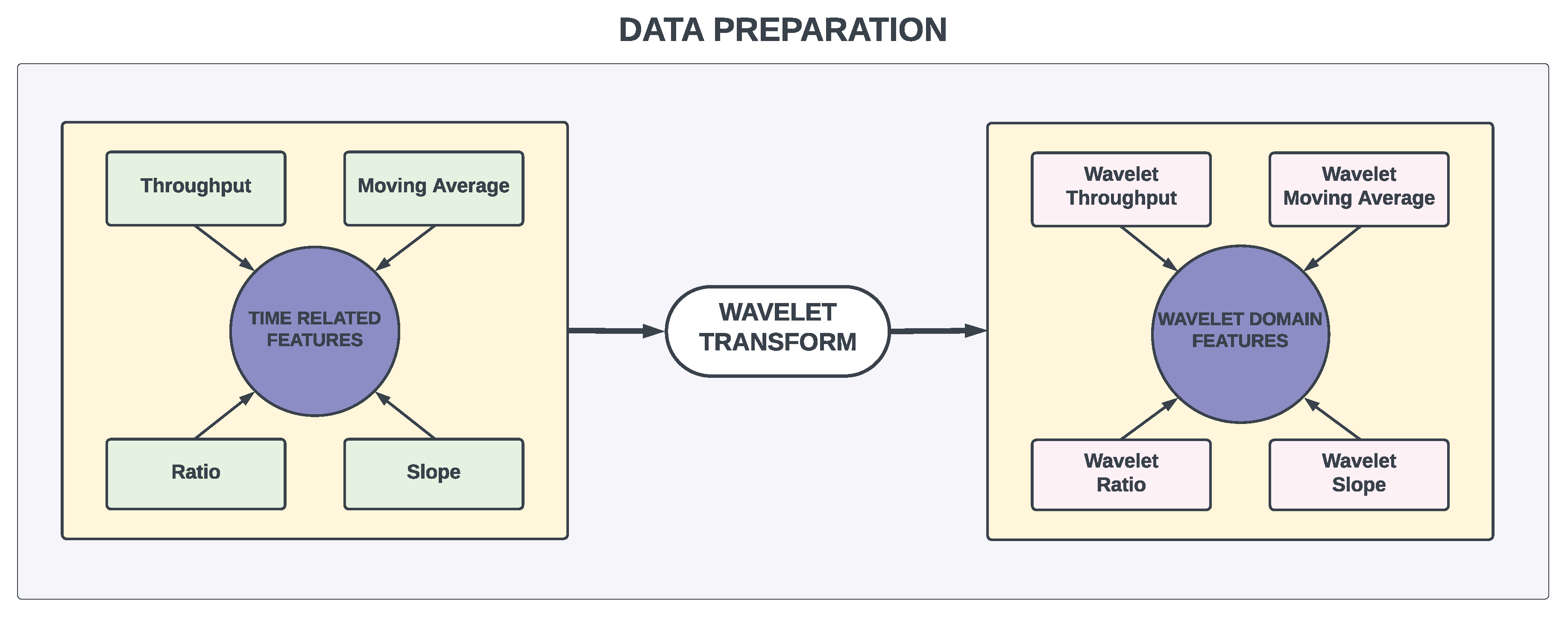

Our methodology integrates artificial neural networks (ANNs) with wavelet-transformed features to improve classification accuracy. By applying wavelet transform to key temporal features—such as throughput, slope, moving averages, and download-to-upload ratio—we expose high-frequency patterns that are often missed in raw time-series data. A detailed visualization of this transformation is presented in

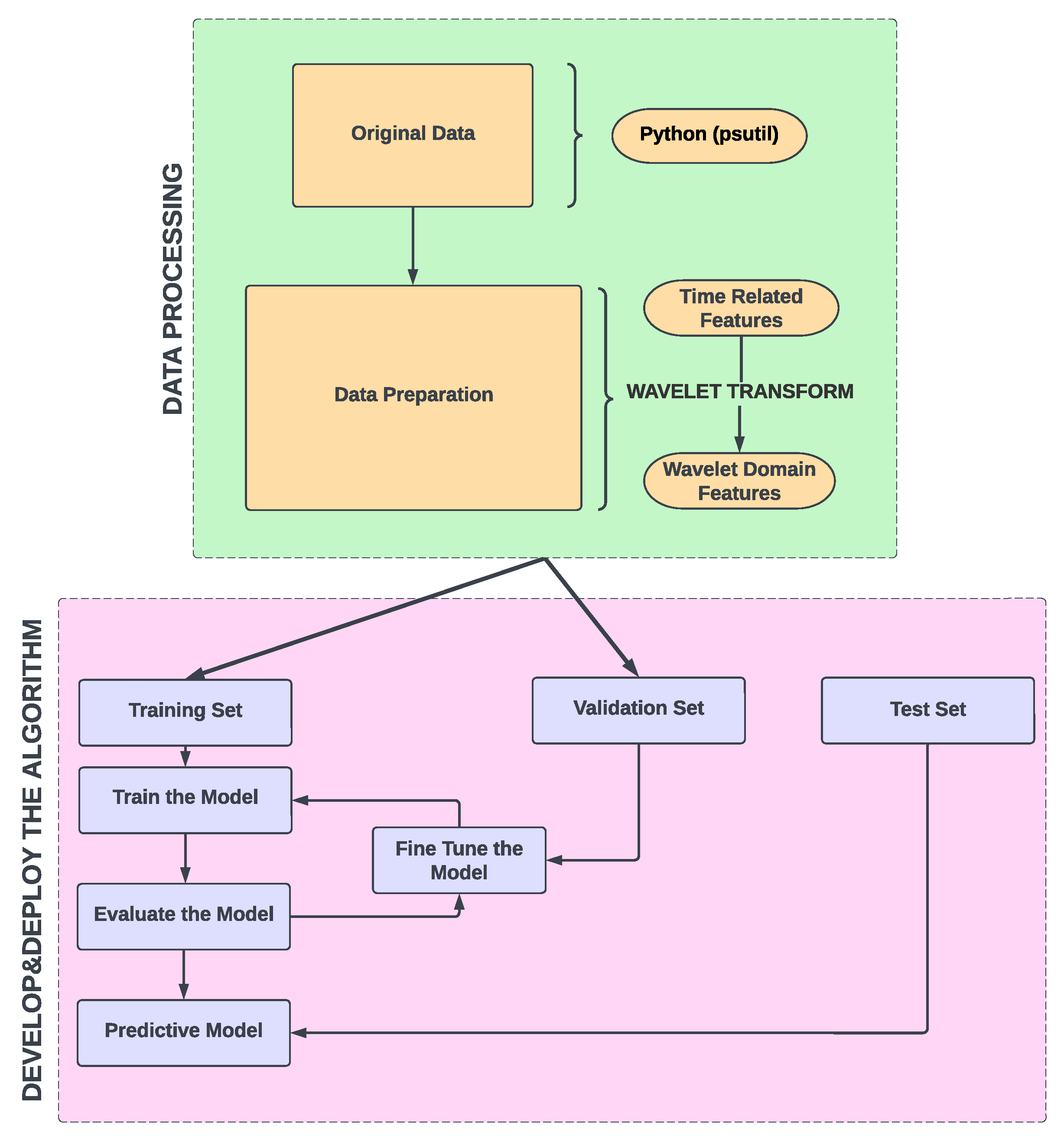

Section 3 (Methodology), where we illustrate the mapping of time-domain features into the wavelet domain 4. The overall system architecture, depicted in

Figure 1, illustrates the integration of wavelet transforms and artificial neural networks into a hybrid framework. The architecture comprises three key stages: (1) extraction of temporal features (e.g., throughput, slope, moving averages), (2) wavelet transformation of these features into frequency-domain representations, and (3) classification via a multilayer perceptron (MLP) ANN. This dual-domain analysis enables the model to capture both time-varying dynamics and multi-scale frequency patterns inherent in low-latency traffic. As discussed in

Section 3.2, the wavelet-transformed features Figure 4 and the ANN classifier Figure 11 are central to achieving robust classification accuracy, particularly in mixed-traffic scenarios

Section 5.

In the forthcoming sections of this article, we will explore our methodology in a comprehensive way, dive into the details of data collection, present our experimental findings, and engage in thoughtful discussions. The goal is to vividly demonstrate the effectiveness of our approach in classifying and identifying low-latency traffic.

2. Related Work

The rapid growth of high-speed Internet services has driven a surge in demand for efficient traffic management and optimization strategies, as highlighted in the Cisco report [

15]. With increasing reliance on real-time applications such as online gaming, video conferencing, and financial trading, the ability to accurately classify low-latency Internet traffic has become a critical research challenge [

16,

17,

18]. However, existing classification methods often struggle with the dynamic and bursty nature of low-latency traffic, necessitating novel approaches that move beyond traditional techniques.

Early traffic classification methods relied on port-based heuristics, deep packet inspection (DPI), and statistical analysis [

19,

20,

21,

22]. While these approaches provided initial insights into network traffic behavior, they suffer from severe limitations in modern networks. Port-based methods are increasingly unreliable due to dynamic port allocations and encryption techniques that obscure traffic signatures [

23]. DPI, while highly accurate, raises significant privacy concerns and requires high computational overhead, making it impractical for large-scale deployments [

24]. Statistical approaches, though lightweight, often fail when dealing with encrypted traffic, which now dominates Internet communications [

25].

To address these shortcomings, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) models have gained traction in traffic classification research. Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), in particular, have demonstrated remarkable success in recognizing complex traffic patterns [

26,

27]. They have been applied to traffic classification, anomaly detection, and predictive modeling, offering adaptability to evolving network conditions [

28,

29,

30]. However, a major challenge with ANN-based methods is their reliance on time-domain traffic features, which often fail to capture the high-frequency fluctuations characteristic of low-latency traffic. As a result, standard ANNs struggle to differentiate between low-latency and non-low-latency traffic in complex network environments.

To enhance feature extraction and improve classification accuracy, researchers have turned to signal-processing techniques such as Wavelet Transform (WT). Wavelet analysis has been widely used in time-series data processing, particularly in network traffic prediction [

31], anomaly detection [

32], and QoS monitoring [

33]. Unlike traditional statistical methods, wavelets decompose network traffic into multiple frequency scales, allowing for a more granular representation of underlying patterns. This capability is particularly useful for low-latency traffic, which exhibits noise-like fluctuations that are difficult to detect in the time domain alone [

34].

Beyond wavelet transformations, recent advancements in Internet traffic classification have focused on trend-based features that enhance model interpretability. Studies have introduced fine-grained statistical features such as moving averages, throughput patterns, and slope-based metrics, which have led to significant improvements in classification accuracy [

6,

22,

35]. Additionally, feature selection techniques—such as multifractal analysis and PCA-based selection—have been applied to refine classification models, further improving performance and robustness [

34,

36]. Despite these advances, most studies still rely solely on time-domain features, which limits their ability to fully exploit the high-frequency patterns unique to low-latency traffic.

Parallel to ML-based solutions, researchers have also explored alternative traffic classification approaches to improve scalability and real-time adaptability. Incremental Support Vector Machines (SVMs) have been developed to handle dynamic traffic patterns, allowing for adaptive classification in real-world networks [

37]. Other work has explored hardware-accelerated classification techniques, such as FPGA-based decision trees, which enable high-speed traffic analysis with minimal computational overhead [

38]. Bio-inspired methods, such as artificial immune system algorithms, have also shown promise in optimizing classification models [

39], while multi-stage classifiers have been proposed for handling encrypted and obfuscated traffic types [

40,

41,

42]. While these approaches offer unique advantages, they still fall short in achieving high-precision classification of low-latency traffic, particularly in mixed-traffic scenarios.

In recent years, deep learning-based traffic classification has gained prominence, with CNN-based models such as Deep Packet [

43] and LSTM-based solutions like FlowPic [

44] achieving state-of-the-art results. These models leverage large-scale datasets, including those introduced by Draper-Gil et al. [

45] and Lashkari et al. [

46], which contain a mix of VPN, Tor, and unencrypted traffic. However, these solutions primarily focus on categorizing general Internet traffic and are not specifically optimized for low-latency classification. Furthermore, their reliance on end-to-end deep learning architectures often sacrifices interpretability, making them less suitable for real-time network management applications.

Despite extensive research in traffic classification, existing methods still struggle to accurately differentiate low-latency traffic due to its highly dynamic and bursty nature. While wavelet transform has been successfully applied in network anomaly detection and QoS analysis, its potential in deep learning-based traffic classification remains largely underexplored. Current deep learning models rely heavily on time-domain features, which fail to capture the high-frequency fluctuations characteristic of low-latency traffic. Additionally, most ANN-based approaches lack a hybrid mechanism that combines both time-domain and frequency-domain features for more precise classification. This paper addresses these limitations by introducing a novel hybrid framework that integrates wavelet transform with artificial neural networks (ANNs) to enhance the classification of low-latency traffic. The following sections present our methodology, experimental results, and discussions that demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach.

3. Methodology

In this section, we will detail the methodology for the identification of low-latency Internet traffic. Our approach combines ANN with the application of wavelet transform to create a powerful system for distinguishing a unique form of ’noise’ from the ’signal’ of network with precision and consistency.

3.1. Data Collection

To conduct our study on the identification of low-latency Internet traffic, data collection was performed over a WiFi network. The data consisted of three categories: Internet traffic generated by applications that require low latency, Internet traffic that does not require low latency, and a combination of these categories, which we call mixed traffic. During the data collection process, the throughput values in both downlink and uplink were continuously recorded and stored in real-time. This data collection procedure aimed to capture a wide range of network traffic information to facilitate a thorough analysis of the low-latency Internet traffic.

3.2. Introducing Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) with Ricker Wavelet

As mentioned in the previous sections, low-latency traffic shares some statistical properties with Gaussian noise, which provides a strong foundation for applying wavelet transform techniques. In this context, it becomes important to understand the complex nature of data flows within networks.

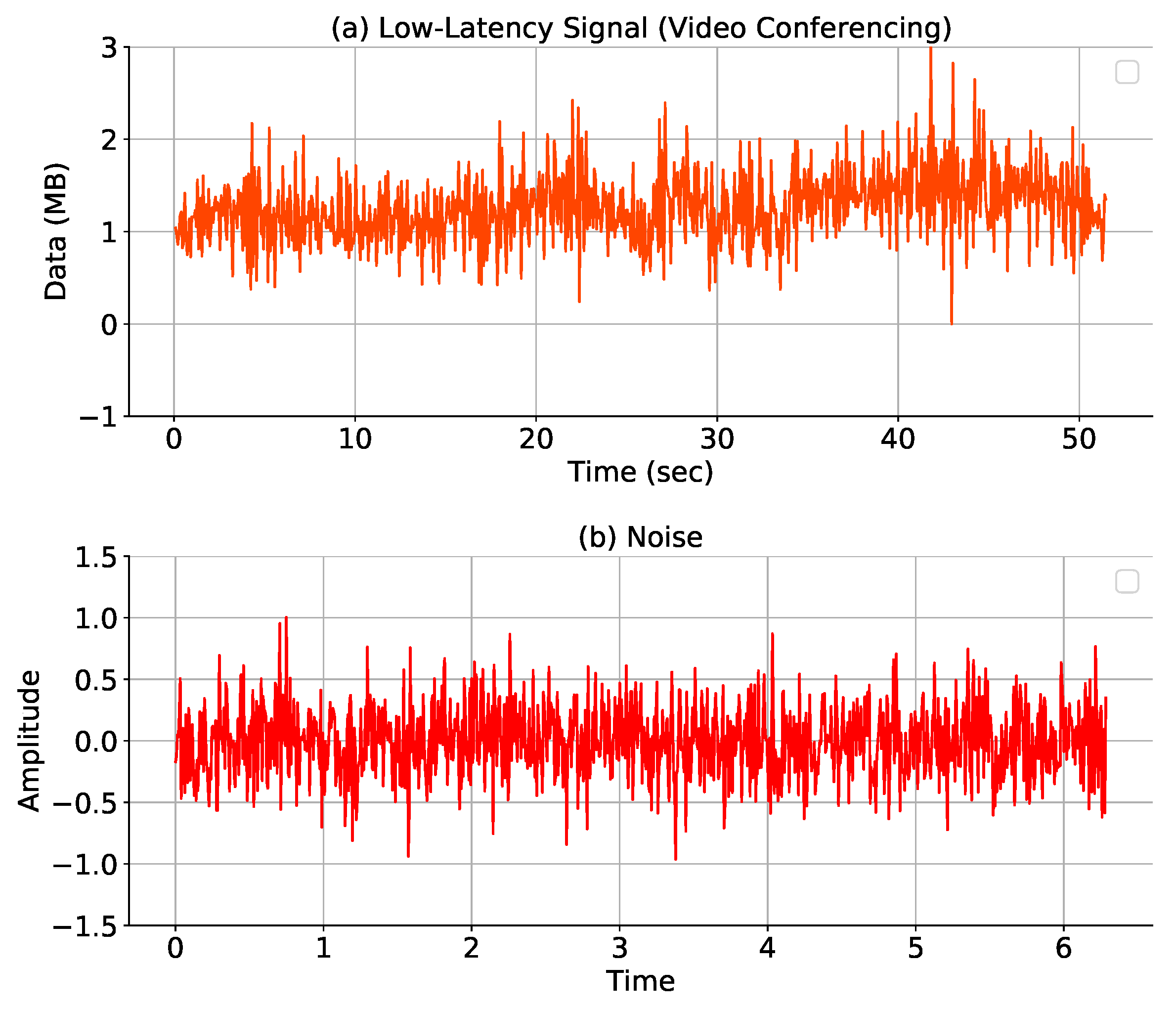

Figure 2 (a) shows the patterns of low-latency Internet traffic throughput of video conferencing and (b) Gaussian noise. The similarity observed in these patterns offers valuable insights, suggesting that low-latency traffic may exhibit noise-like characteristics. In signal processing, noise is conventionally perceived as unpredictable fluctuations or disturbances that can obscure crucial signal information [

12]. In contrast, low-latency traffic exhibits a form of organized ’noise,’ a controlled and structured flow of data characterized by frequent exchanges of small packets [

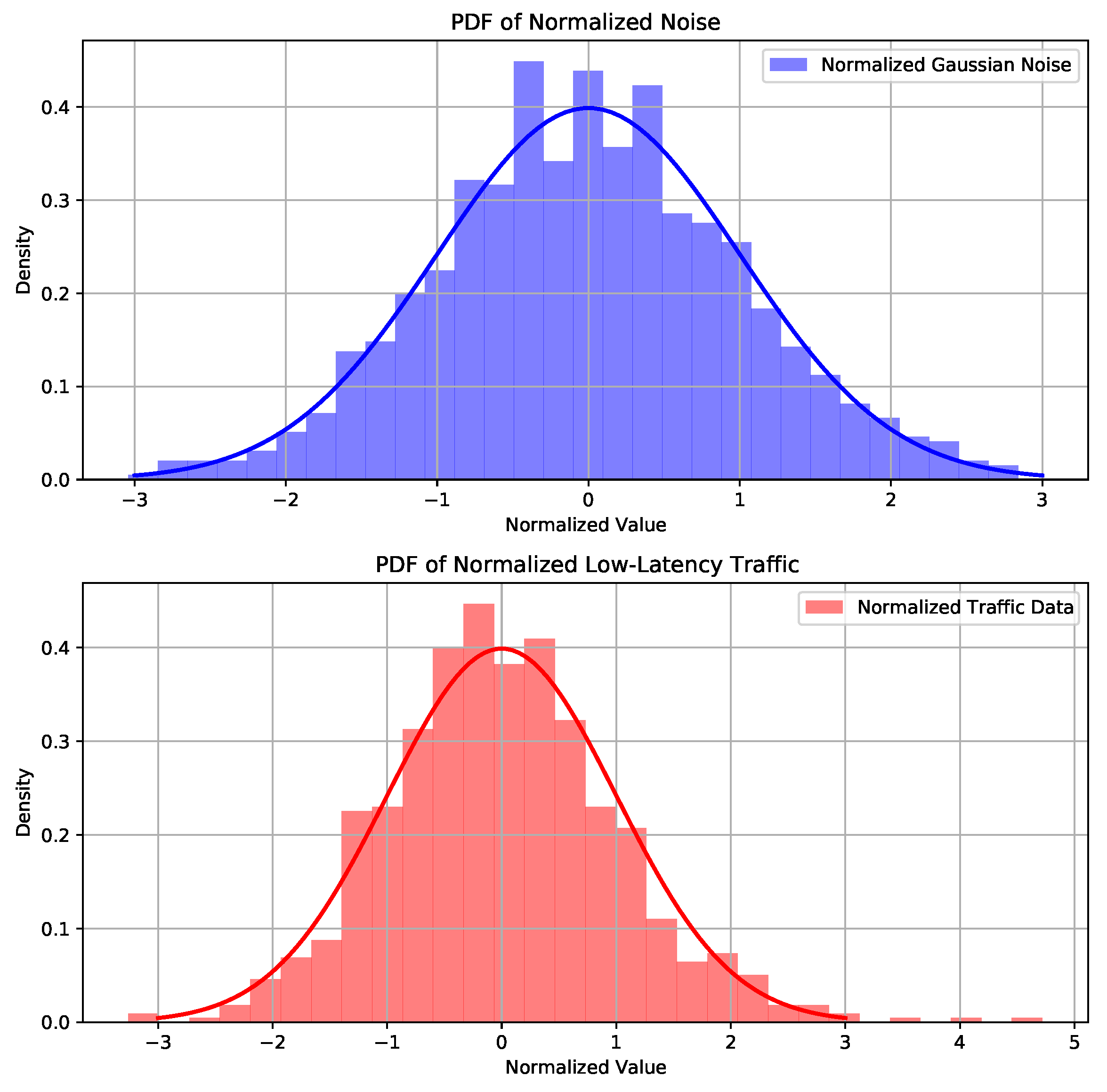

6]. To further support this observation,

Figure 3 presents the Probability Distribution Functions (PDFs) of both the low-latency traffic (b) and Gaussian noise (a). PDF analysis demonstrates that, when normalized, both signals share similar statistical properties, such as a classic bell-shaped curve, maximum density, and tails of the distribution. These similarities reinforce the idea that low-latency traffic can be modeled using signal processing techniques traditionally applied to noise in signal systems, such as wavelet transforms. This parallel draws attention to the fact that, while the nature of this data exchange might appear as noise to a casual observer, it is actually a deliberate and integral component within the network environment [

47].

Obtaining representations in the frequency domain is crucial for several reasons. The frequency domain provides a different perspective on the data, highlighting patterns and characteristics that may not be apparent in the time domain. This is particularly valuable for analyzing non-stationary signals, where the signal properties change over time. Thus, all the extracted time-related features are processed using the continuous wavelet transform (CWT). The CWT is a powerful mathematical technique employed to analyze non-stationary signals in both time and frequency domains. Unlike other transforms such as the Fourier Transform, the CWT decomposes a signal into various frequency components over time, enabling the capture of localized features and time-varying characteristics. This ability to capture fine-scale variations and changes in a signal makes the CWT particularly well suited for analyzing dynamic and irregular signals. Low-latency Internet traffic exhibits time properties similar to these signals, making CWT an effective tool for its classification. To better capture both short-term and long-term variations in Internet traffic, we apply wavelet transforms to key temporal features. This transformation provides a frequency-domain representation, exposing structured patterns in network traffic that traditional time-domain features fail to reveal.

Figure 4 illustrates how core temporal features (e.g., throughput, slope, moving averages, and ratio) are mapped into their corresponding wavelet representations, which serve as enhanced inputs for the ANN model.

The Ricker wavelet (also called the Mexican hat wavelet) is one of the commonly used wavelets in CWT. The Ricker wavelet is defined mathematically as follows:

where

t is the time variable,

f is the central frequency of the wavelet, and

is the width parameter that determines the scale of the wavelet.

The application of a wavelet transform enhances the feature representation by decomposing time-related features into distinct frequency components. This transformation allows the model to identify patterns in different frequency bands, enabling it to capture both short-term and long-term variations in network behavior. This capability is vital for accurate and robust classification of low-latency Internet traffic, which often exhibits complex, multi-scale patterns due to the nature of real-time applications.

Furthermore, low-latency traffic such as video conferencing or online gaming generates frequent, small data throughput bursts that may appear as noise in conventional time-domain analysis. However, by applying wavelet transform, we can isolate and emphasize these throughput bursts, which are characteristic of low-latency traffic, thus distinguishing them from other traffic types such as FTP or video streaming, which have different temporal dynamics. For instance, the wavelet transform helps to separate high-frequency components corresponding to the rapid exchanges in low-latency traffic from the slower, more consistent patterns seen in bulk data transfers.

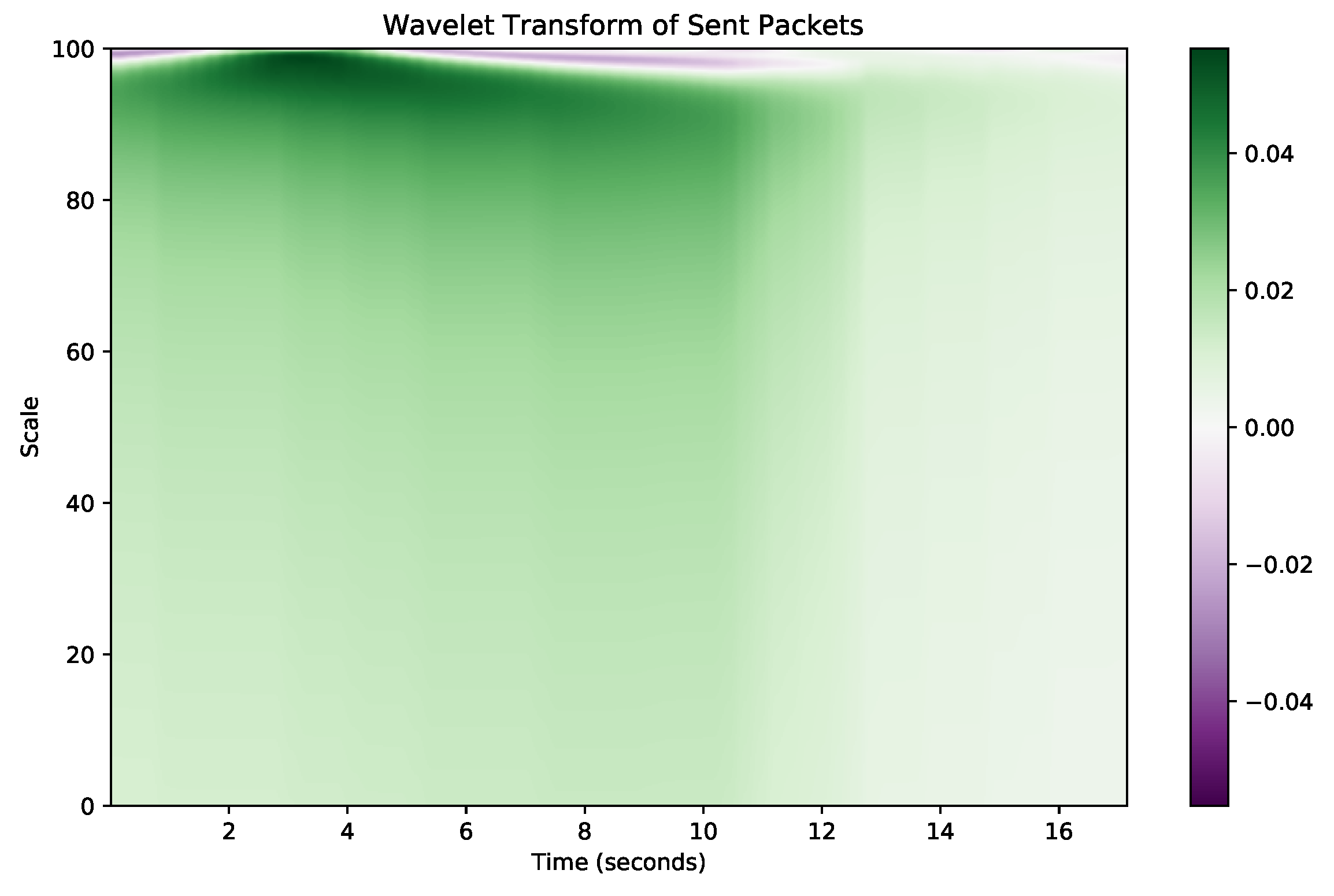

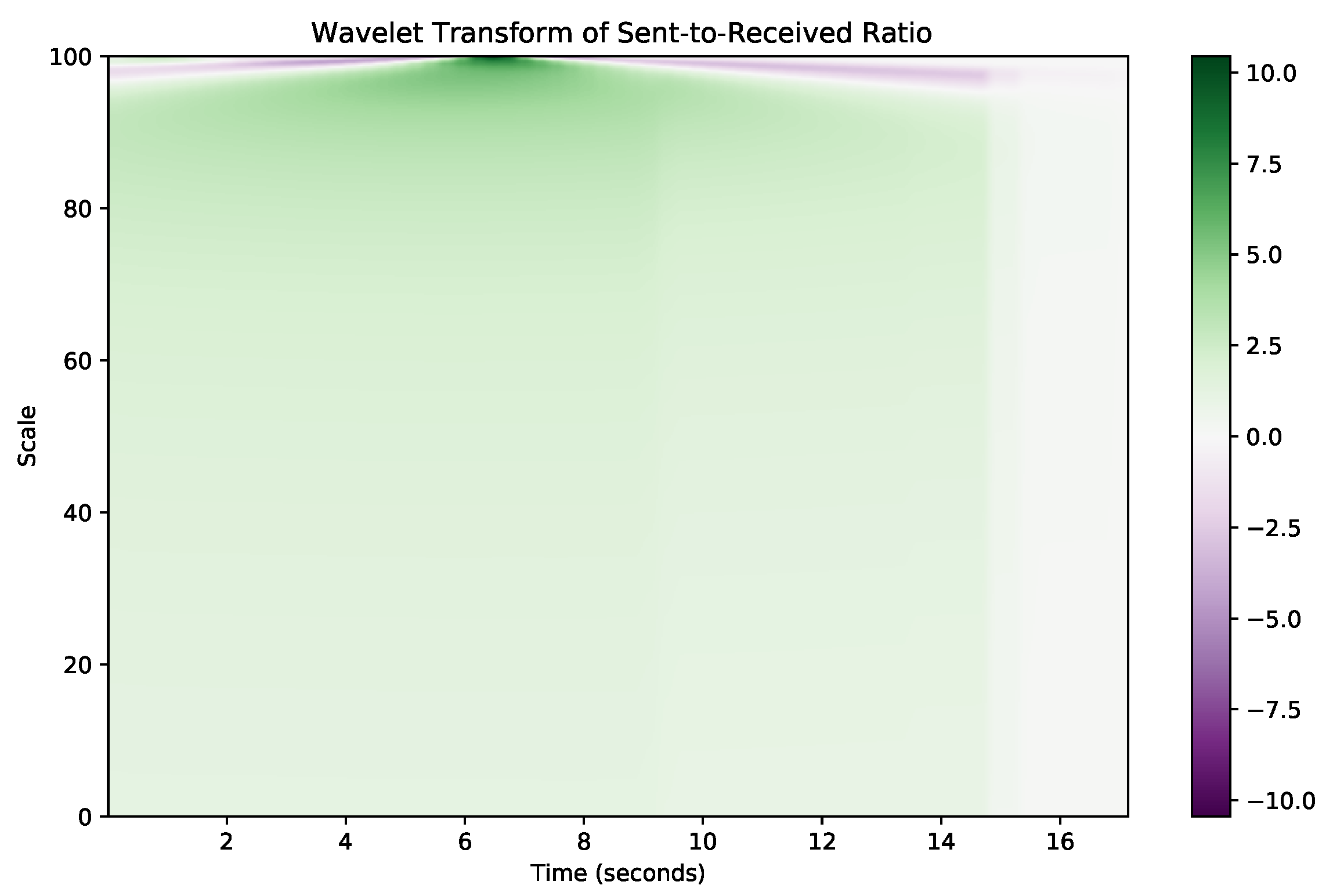

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrate this transformation for throughput and the ratio of sent to received packets, respectively, highlighting the distinct frequency components that the wavelet transform extracts from the raw time-domain features.

Using these enhanced feature representations, our ANN model becomes more adept at recognizing the unique patterns associated with low-latency traffic. This addresses the core challenge in traffic classification, where the goal is to accurately identify and prioritize time sensitive data flows among a diverse mix of network activities.

3.3. Data Preparation

After collecting raw data related to sent and received packets, a series of pre-processing steps were applied to extract novel time-domain features. These preprocessing steps were designed to improve the data set with meaningful features that could be used for effective classification. The following time domain features were derived for each network traffic:

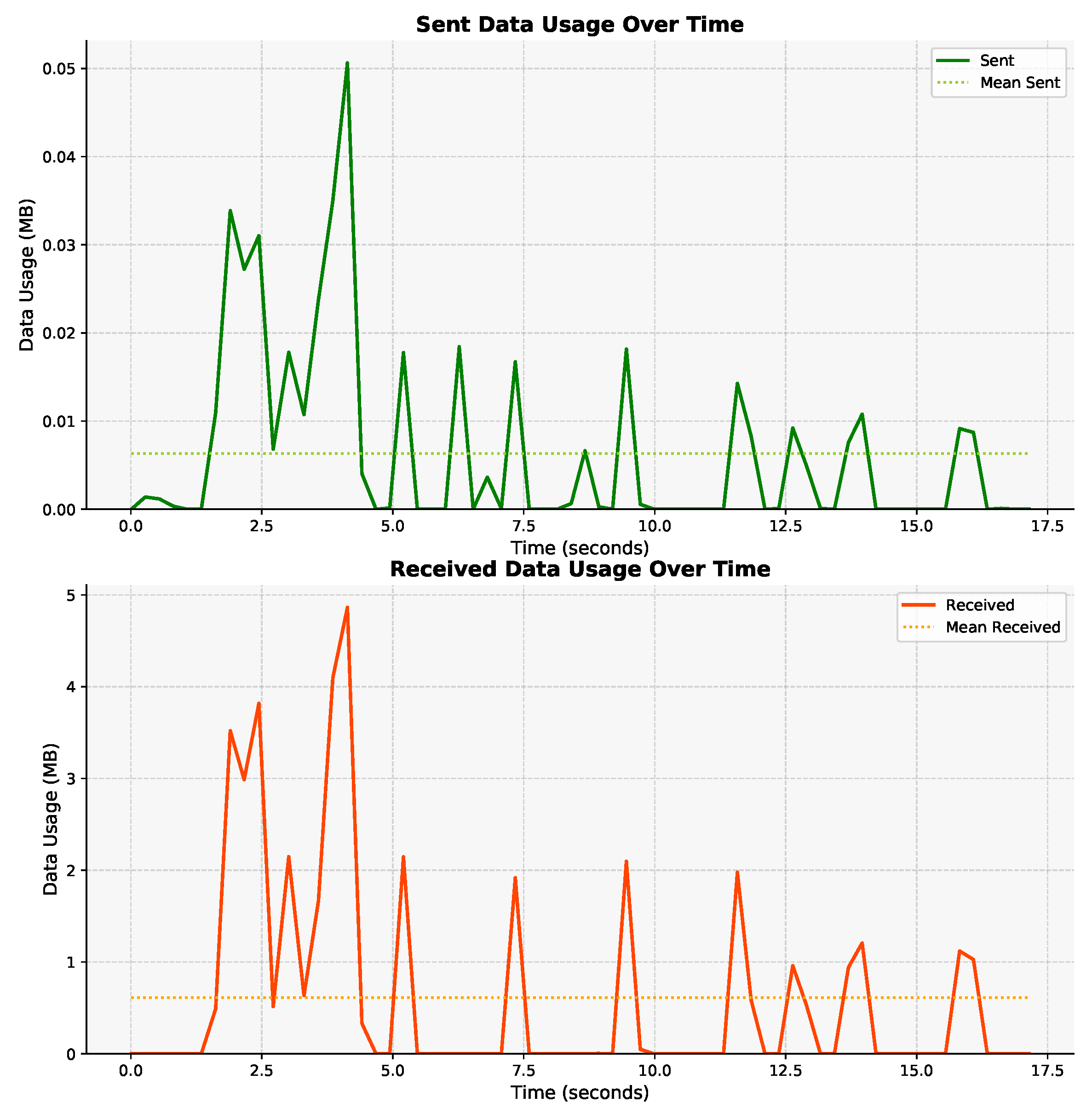

3.3.1. Throughput

This feature represents the total volume of data (in bytes) captured within specific time intervals during the measurement. The collected data includes the volume of individual sent and received traffic aggregated over these intervals. The features are denoted by

for the total volume of sent traffic and

for the total volume of received traffic within the interval. Here,

i represents the index of the time interval. Thus, for each traffic, the feature ’Throughput’ captures the volume of the sent and received data, providing valuable information about the data traffic patterns over time. In

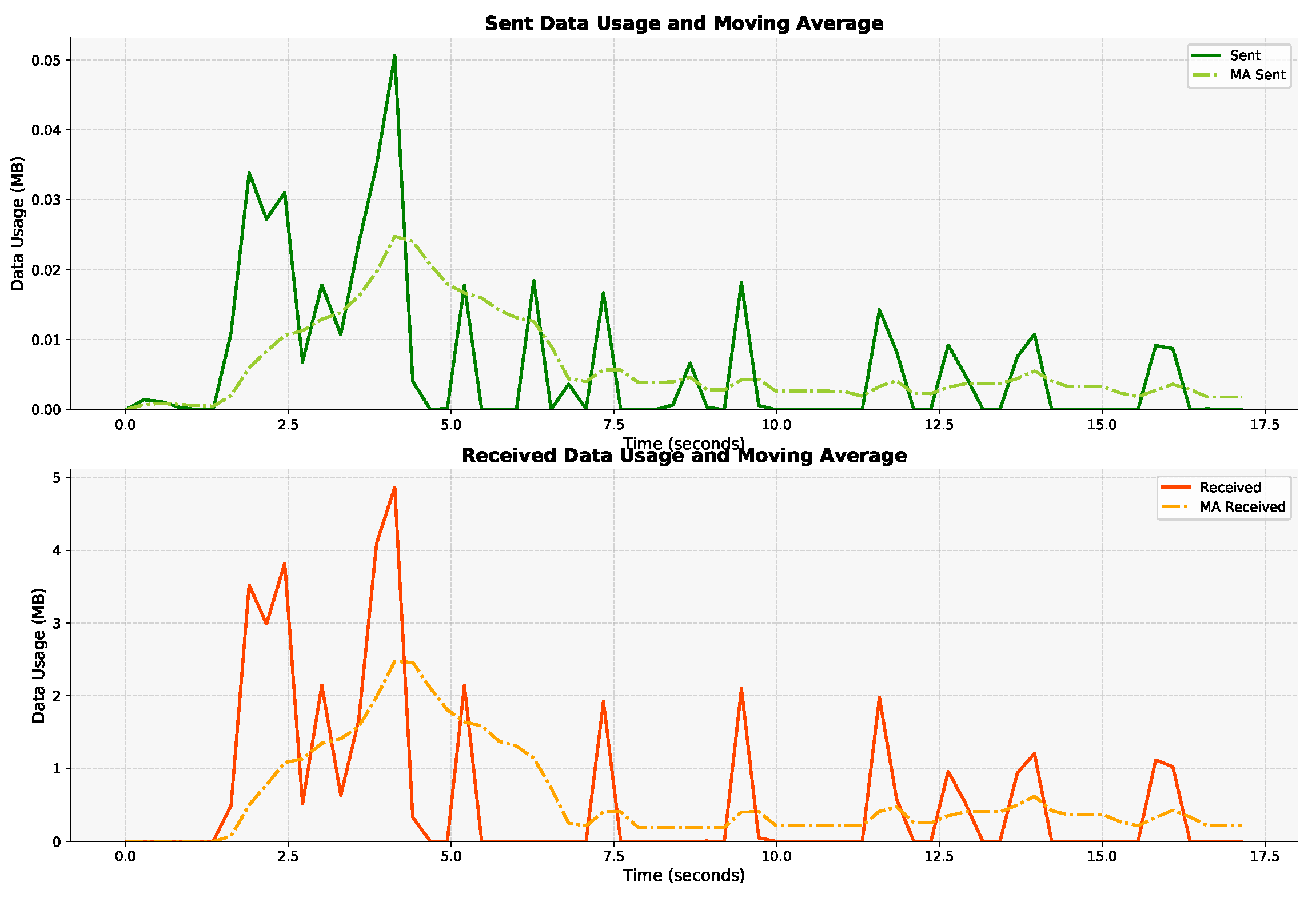

Figure 7, the throughput of YouTube traffic in the downlink and uplink is demonstrated.

3.3.2. Moving Averages

This feature calculates the moving average of throughput in time, which can provide insight into the application’s traffic patterns. The moving averages of throughput in uplink and downlink are denoted by

,

, respectively, and computed using the following formulas:

where

k represents the moving average period (window size),

i denotes the current time index, and

represents the throughput at that time

j.

The moving average of throughput allows the model to consider the dynamic behavior of network traffic over time. By incorporating this feature, the model can detect variations in data flow rates and adapt its classification decisions based on temporal patterns, which is crucial for identifying intermittent low-latency conditions. In

Figure 8, MA of YouTube traffic is demonstrated.

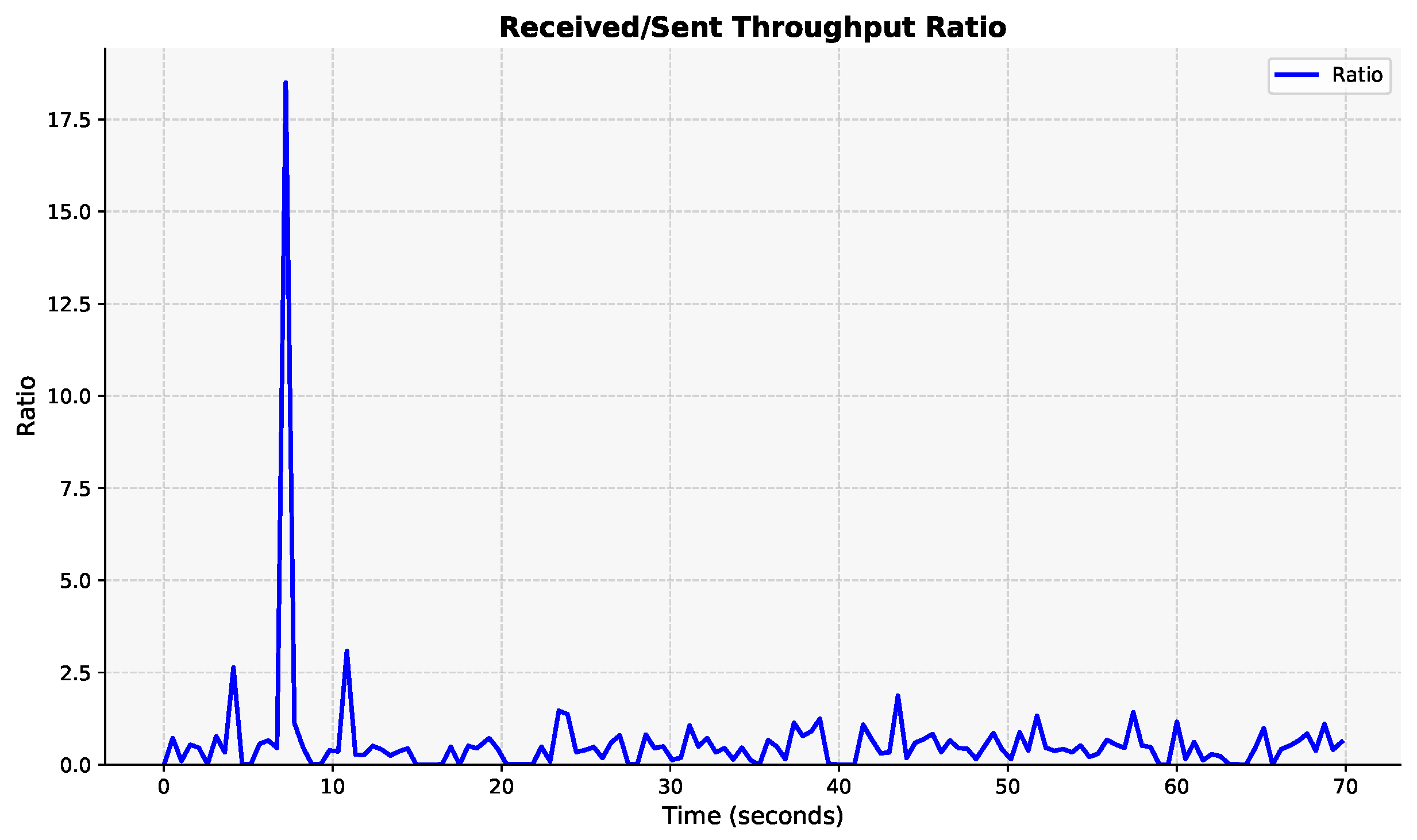

3.3.3. Ratio

This feature measures the downlink to uplink throughput values over time. The ratio, denoted by

R, is calculated as:

where

i denotes the current time index,

represents the downlink throughput, and

represents the uplink throughput at time

i.

The ratio quantifies the asymmetry between the sent and received throughput, revealing the unidirectional or bidirectional nature of each application. This characteristic helps the model distinguish between scenarios where byte transfer is required for both uplink and downlink communication and those where it is essential only for specific directions. In

Figure 9, the received to sent throughput ratio of YouTube traffic is demonstrated.

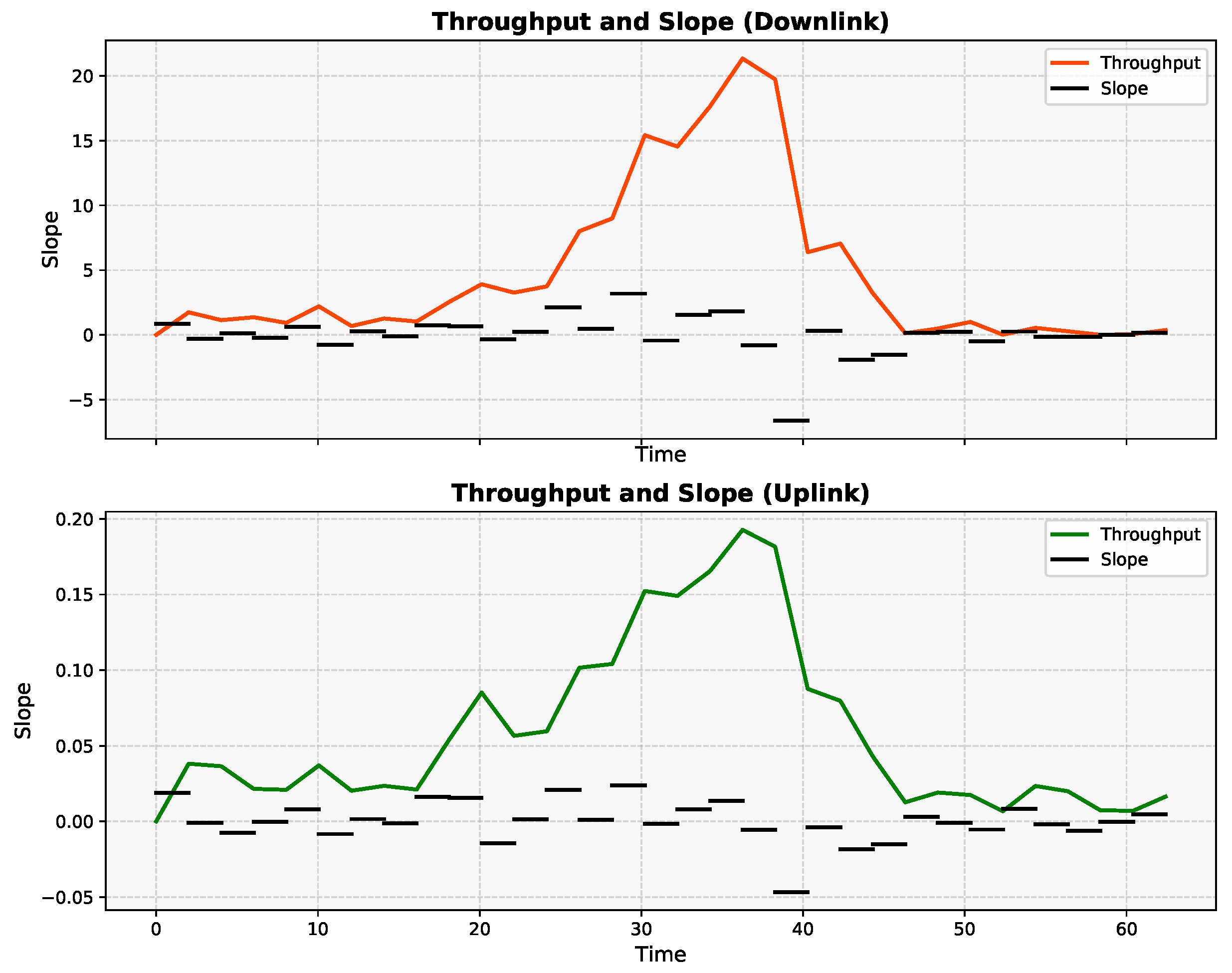

3.3.4. Slope

The slope of the throughput indicates the change in the number of packets over time. It is represented by

for sent packets,

for received packets and calculated as:

where

represents the number of sent packets at time

i, and

is the corresponding time stamp.

The slope feature, which captures the rate of change in throughput over time, provides valuable information on the dynamics of Internet traffic. Positive slope values indicate an increasing trend in byte activity, whereas negative slope values indicate a decrease. This feature is particularly useful for identifying traffic types characterized by distinctive patterns over time, such as video streaming. Video streaming traffic, for example, often shows a consistent and predictable pattern of data transmission due to buffering and playback mechanisms. Representation of it can be seen in

Figure 10. In addition, this characterization of trends offers crucial discriminatory information for the classification of various classes of low-latency Internet traffic.

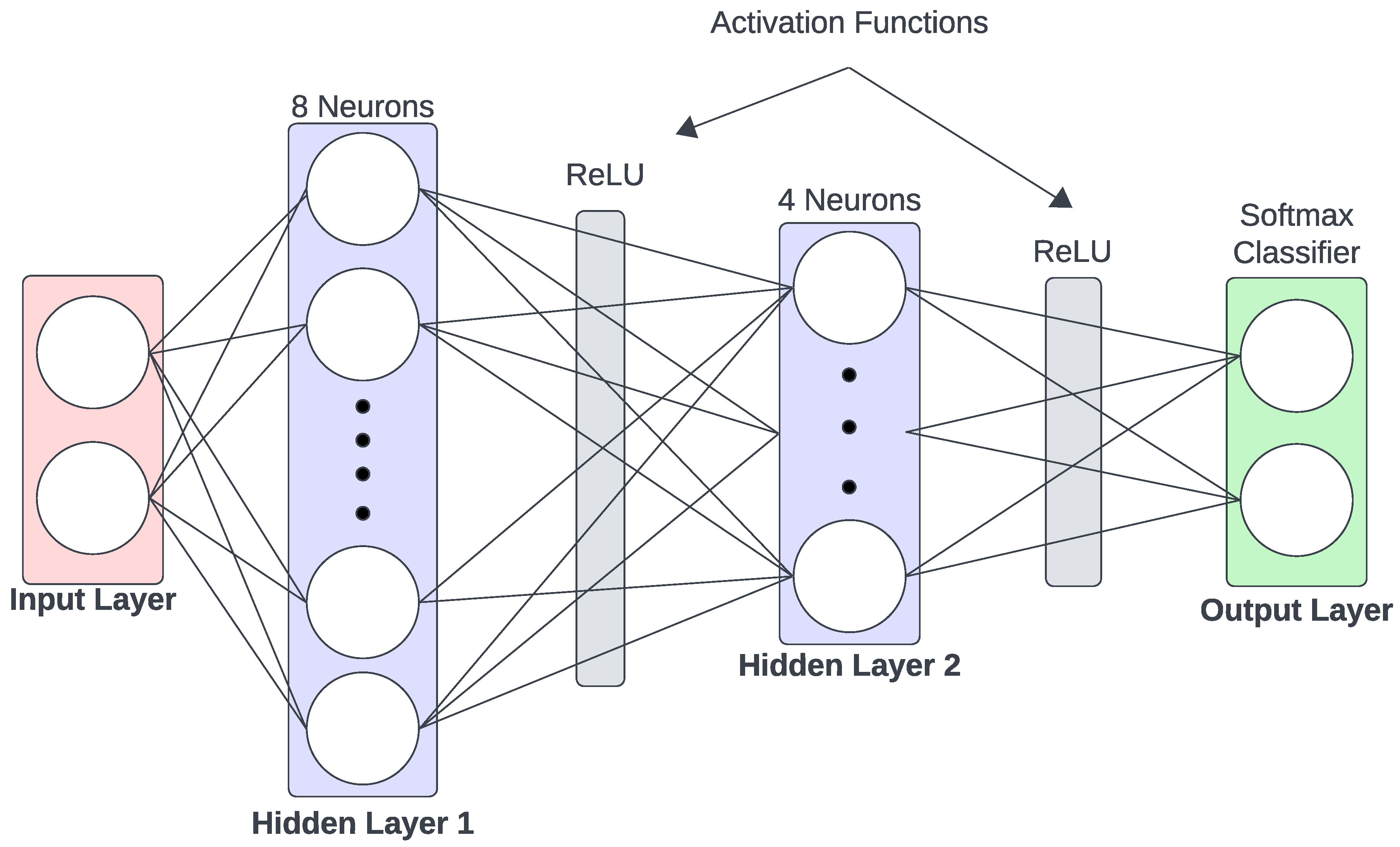

3.4. Artificial Neural Network

The objective of incorporating a multilayer perceptron (MLP) in our framework is to take advantage of its powerful pattern recognition capabilities [

48] to accurately classify low-latency Internet traffic. In our approach, the MLP serves as the core component of the artificial neural network model, which is essential to analyze the complex temporal dynamics present in the network traffic data. Using MLP, our aim is to effectively distinguish between various types of Internet traffic, ensuring high accuracy in identifying low-latency traffic patterns. The multilayer perceptron belongs to a category of feed-forward artificial neural networks, as depicted in

Figure 11. It typically comprises three or more layers. The initial layer is designated for receiving input data. Subsequent hidden layers, one or more in number, are responsible for extracting relevant features from the input data. The final layer produces a classification result. Each hidden layer, such as the

layer, is constructed with multiple neurons primarily utilizing a nonlinear activation function, as described below:

where

denotes an activation function, for example,

. A key attribute of the activation function is its ability to provide a smooth transition as input values change.

represents a weight matrix, and

is a bias vector. It is possible to have multiple hidden layers, and each layer performs the same function but with distinct weight matrices and bias vectors. The final layer produces the output based on the results of the last hidden layer, often denoted as layer

j and described as:

The deep learning model employed in this study is a feedforward neural network with three layers demonstrated in

Figure 11: an input layer, two hidden layers, and an output layer. The architecture is mathematically defined as follows.

4. Experiment Setup

Due to the simplicity and efficiency of our design, our experiments were performed on a standard Windows 10 PC with an Intel Core i7 processor running at 3.20 GHz and 16 GB of RAM. This configuration was sufficient for the execution and training of the artificial neural network model without the need for additional computational resources, such as GPU acceleration. Furthermore, we used TensorFlow [

49], a versatile and powerful machine learning framework, which further facilitated the efficient implementation and training of our model.

4.1. Dataset

The data collection process was performed on a local WiFi network, and the set of traffic traces comprised FTP, video streaming, low-latency and mix of these. The traces were collected over a 50 Mbps Internet connection, and the throughput measurements of the active traffic in both directions was recorded and stored. In total, over 350,000 samples of throughput values (more than 35 hours of applications usage) were collected.

For the experiments, we designed two types of scenario: basic and complex. The basic scenarios, detailed in Table 2, involved pairwise combinations of traffic types, while the complex scenarios, described in Table 3, involved three or more types of traffic co-existing simultaneously. Each scenario was meticulously selected to ensure a comprehensive evaluation of our model’s performance under various real-world traffic conditions.The selection of such traffic mixes is similar to the approach used in the Low Latency DOCSIS study, which also employed a mix of different traffic types to evaluate latency performance and network behavior under varying conditions [

50].

In the basic scenarios where (Table 2), we tested combinations such as:

FTP + Video Streaming (A + B),

FTP + Low-Latency (A + C),

Video Streaming + Low-Latency (B + C), and

Repeated instances of the same traffic type (A + A, B + B, C + C).

For the complex scenarios (Table 3), we included combinations such as:

Three instances of the same traffic type (3A, 3B, 3C),

Two instances of one type combined with one instance of another (2A + B, A + 2B, 2A + C, A + 2C, 2B + C, B + 2C),

One instance of each traffic type (A + B + C),

One instance of each traffic type (A + B + C), and

Multiple instances of mixed traffic types (2A + B + C, A + 2B + C, A + B + 2C).

This comprehensive scenario design enabled a robust analysis of low-latency Internet traffic, ensuring the reliability and accuracy of our classification methodology.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

Similar to [

43], we measure the model’s performance using key metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1 score, to assess the effectiveness of traffic classification. Accuracy, denoted as

A, serves as an indicator of the model’s performance, reflecting the proportion of correctly classified instances out of the total samples, and is computed following equation

16. However, it is essential to understand that high accuracy alone may not provide a complete picture, especially in scenarios with imbalanced datasets.

Precision and recall offer deeper insights into the model’s performance on different classes of traffic. Precision, which measures the ratio of true positive predictions to the total predicted positives, is particularly crucial in assessing the model’s reliability in identifying low-latency traffic without false alarms. In contrast, recall, which calculates the ratio of true positive predictions to all actual positives, highlights the model’s ability to capture all relevant instances of low-latency traffic. The mathematical representations of these metrics are as follows:

The F1 score, as a harmonic mean of precision and recall, provides a balanced metric that is especially useful when dealing with imbalanced classes. In the context of our study, where accurate identification of low-latency traffic is critical, the F1 score serves as a robust measure of the model’s overall effectiveness and is defined as:

By focusing on these metrics, we can better understand the strengths and weaknesses of our classification model. For instance, while accuracy gives us a broad view, precision and recall help us delve into specific aspects of model performance that are crucial for practical applications, such as minimizing false positives in low-latency traffic detection. This comprehensive evaluation ensures that our model is not only accurate but also reliable and efficient in real-world scenarios.

4.3. Hyperparameter Tuning

In pursuit of optimizing the performance and robustness of our ANN model, a systematic hyperparameter tuning process was conducted.

Table 1 presents the hyperparameter tuning process for the ANN model used in this study.

A range of values was considered for each parameter, including the number of hidden layers, the activation function, the learning rate, the batch size, the number of epochs, the optimizer, and the dropout rate. While detailed evidence of each hyperparameter’s impact is beyond the scope of this paper, the chosen values reflect common practices and insights from the literature [

51,

52].

The grid search method was applied to systematically evaluate different combinations of these hyperparameters. The optimal configuration, which resulted in the best model performance, was selected as follows:

These hyperparameter choices are aligned with common practices in the field and are supported by various studies demonstrating their effectiveness in similar contexts [

52,

53]. The selection process aimed to achieve a model that performs well in terms of both accuracy and generalizability, without overfitting.

5. Experimental Results & Analysis

The experiments were meticulously planned to assess the efficacy of our work by contrasting it with state-of-the-art classification methods. To ensure that our evaluation is appropriate for the problem of low-latency Internet traffic classification, we designed our experiments with the following considerations:

Diverse Traffic Types: We included a variety of traffic types such as FTP, video streaming, and low-latency traffic. This selection ensures that our model is tested against different patterns of Internet traffic, reflecting real-world scenarios.

Balanced Dataset: The dataset used for training and testing the classification algorithm was designed to maintain a balanced representation of each traffic type, with approximately one hour’s worth of sampling per category. This balance is critical for avoiding bias in the model’s performance.

Comparison with Established Methods: Our approach was compared with state-of-the-art classification methods, including k-NN, CNN, and LSTM-based models, as highlighted in various studies [

6,

43,

54,

55], and [

44]. This comparison not only validates the robustness of our model but also situates our results within the context of existing research.

Evaluation Metrics: We measured the model’s performance using key metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1 score. These metrics are standard in the field of traffic classification and provide a comprehensive assessment of the model’s effectiveness.

Confusion Matrix Analysis: The use of confusion matrices allowed us to visualize the classification performance across different traffic types, providing insights into the strengths and weaknesses of our model.

Mixed Traffic Scenarios: We evaluated our model under both simple and complex traffic scenarios to understand its performance in real-world conditions where multiple types of traffic coexist. This evaluation is crucial for demonstrating the practical applicability of our approach.

Our initial experiments focused on evaluating the classification performance in mixed traffic scenarios involving different types of Internet traffic, such as File Transfer Protocol (FTP), video streaming, and low-latency traffic. These scenarios were selected based on a section of the [

50] and our own experiences. These scenarios reflect real-world conditions where multiple types of traffic coexist, providing a comprehensive test of the model’s ability to accurately identify the traffic types. We designed a series of basic traffic scenarios to assess the model’s accuracy. As shown in

Table 2, these scenarios consisted of different combinations of two or more traffic types, with special attention to the presence of low-latency traffic. The results demonstrated that the model achieved higher accuracy when low-latency traffic was involved, with the highest accuracy of 96.5% in the scenario where both instances were low-latency traffic. In scenarios without low-latency traffic, the accuracy was slightly lower, such as 88.3% in the case of two FTP instances.

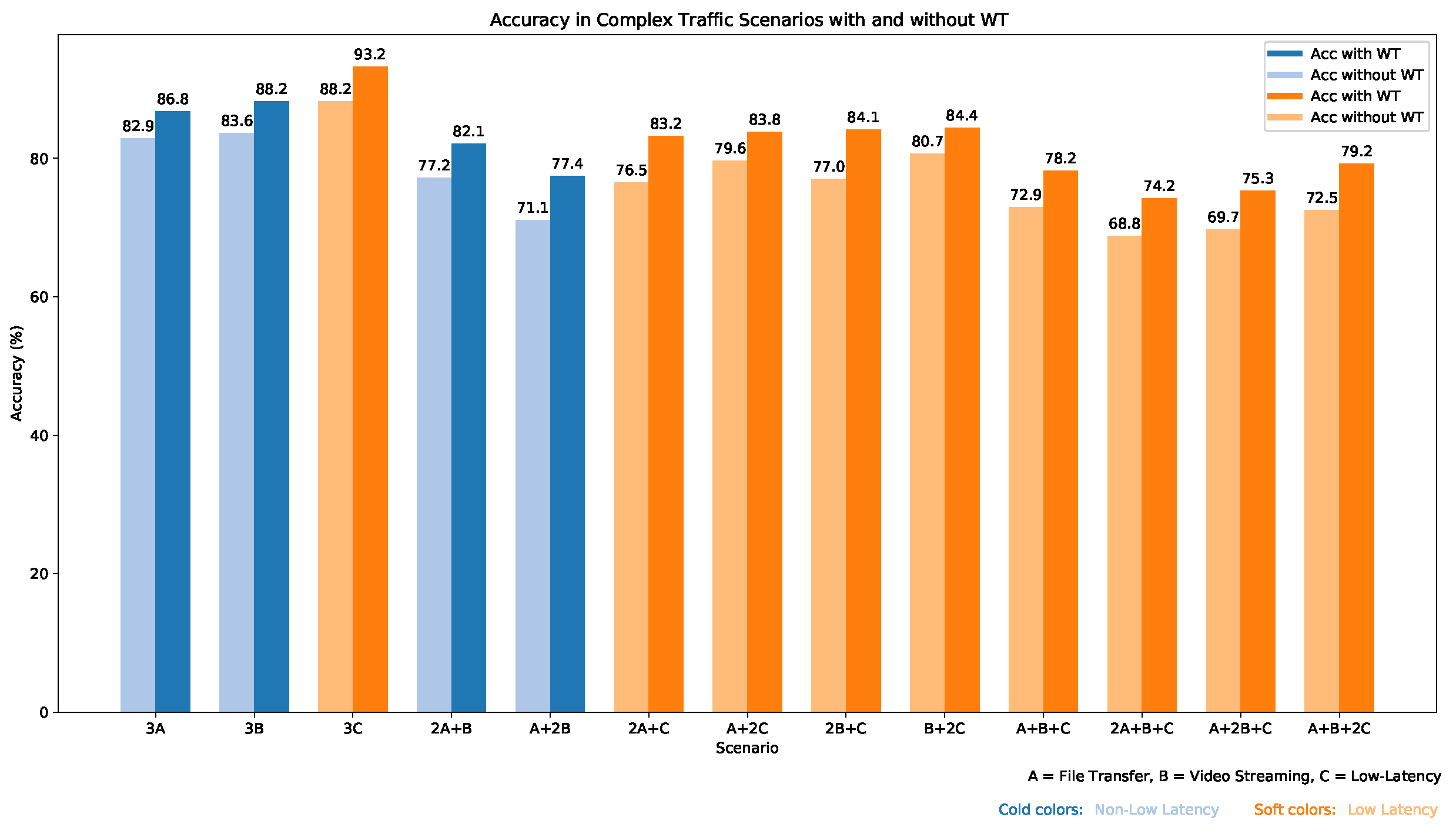

In addition to the basic traffic scenarios, we designed a set of complex traffic scenarios to further evaluate the model’s performance in more challenging environments where three or more types of traffic coexist. These scenarios provide insight into how the model performs as the traffic patterns become more intricate and diverse.

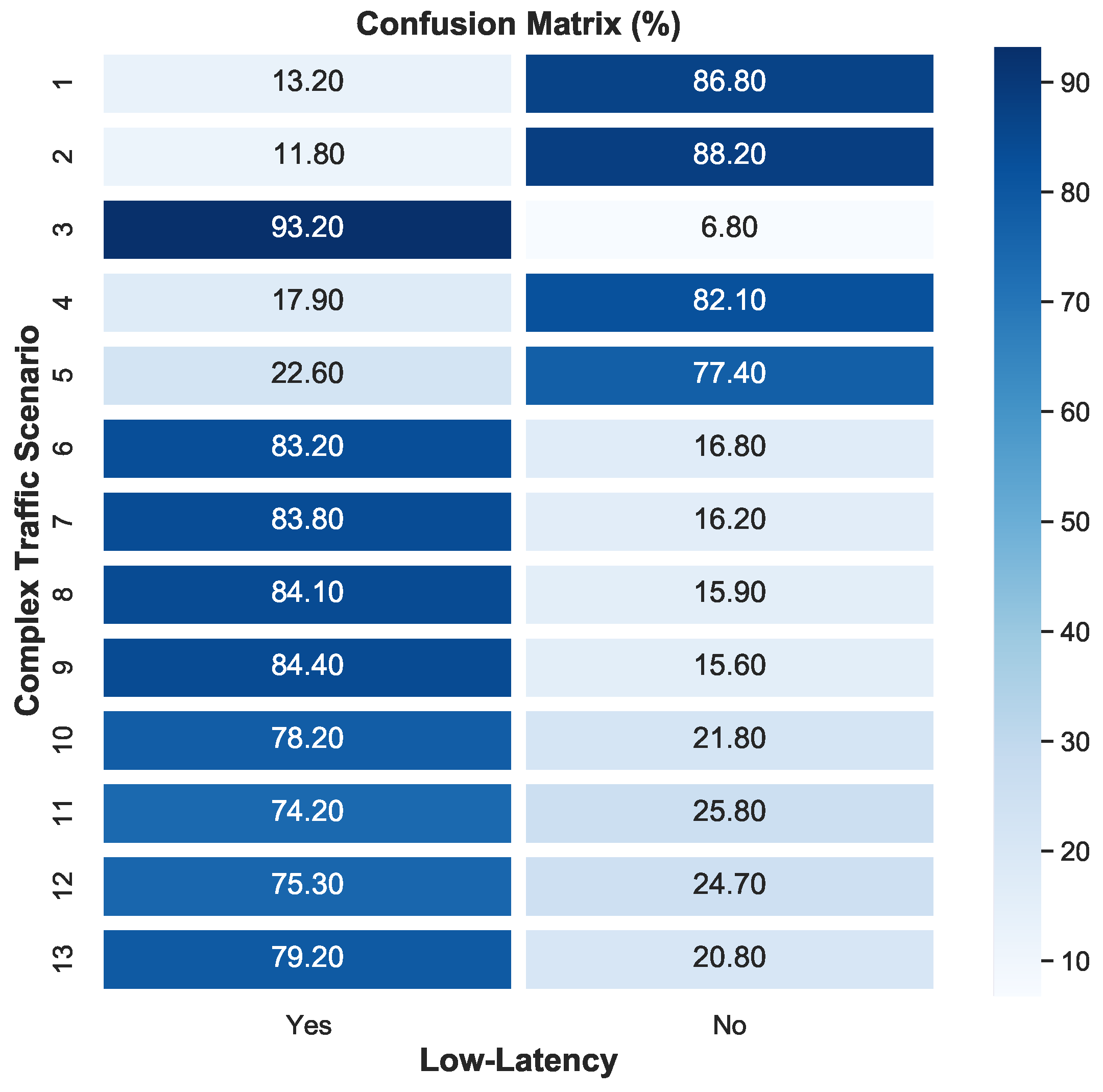

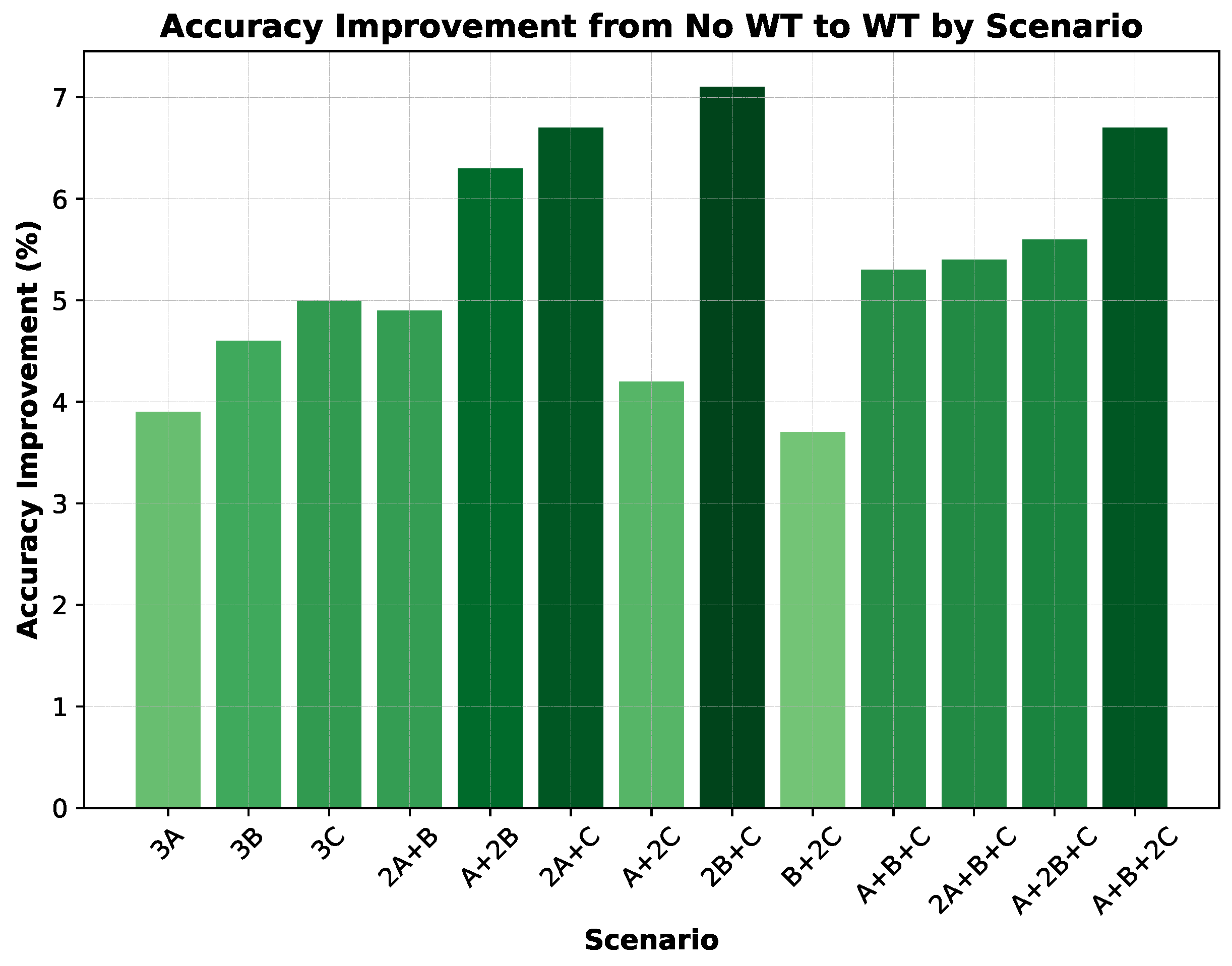

Table 3 presents the results of these experiments, showing the classification accuracy both with and without the application of wavelet transform (WT). The wavelet transform was employed to enhance feature extraction, particularly in the presence of low-latency traffic, which often exhibits patterns similar to noise in signal processing. The addition of wavelet transform consistently improved classification accuracy across all scenarios. For example, in Scenario 3C, where all traffic types were low-latency, the model achieved an accuracy of 93.2% with wavelet transform, compared to 88.2% without it. Similarly, in Scenario 6 (2A+C), where the traffic was composed of two instances of FTP and one instance of low-latency traffic, accuracy improved from 76.5% to 83.2% with the application of wavelet transform. As complexity increased, such as in scenarios with four types of traffic (e.g., Scenario 13: A+B+2C), the model’s performance remained strong but showed a slight decline, with an accuracy of 79.2% with wavelet transform. This decline reflects the increasing difficulty in distinguishing between different traffic types as the mix becomes more complex.

Figure 12 and

Figure 13 further visualize the model’s performance. The confusion matrix (

Figure 12) displays the accuracy of the model in classifying low-latency traffic across the complex traffic scenarios. The diagonal dominance shows a strong correlation between predicted and actual classifications, with the model performing particularly well in distinguishing between low-latency and non-low-latency traffic. Scenarios where low-latency traffic was present (e.g., Scenario 3C) showed a high classification accuracy. Furthermore,

Figure 13 illustrates the accuracy improvement brought about by applying the wavelet transform in each scenario. The plot clearly shows a consistent increase in accuracy when wavelet transform is applied, particularly in scenarios with low-latency traffic, highlighting the robustness of our model under complex conditions. Also,

Figure 14 provides a visual representation of the accuracy improvement across various scenarios. The improvement is evident, particularly in scenarios involving low-latency traffic, where the wavelet transform significantly enhances classification performance.

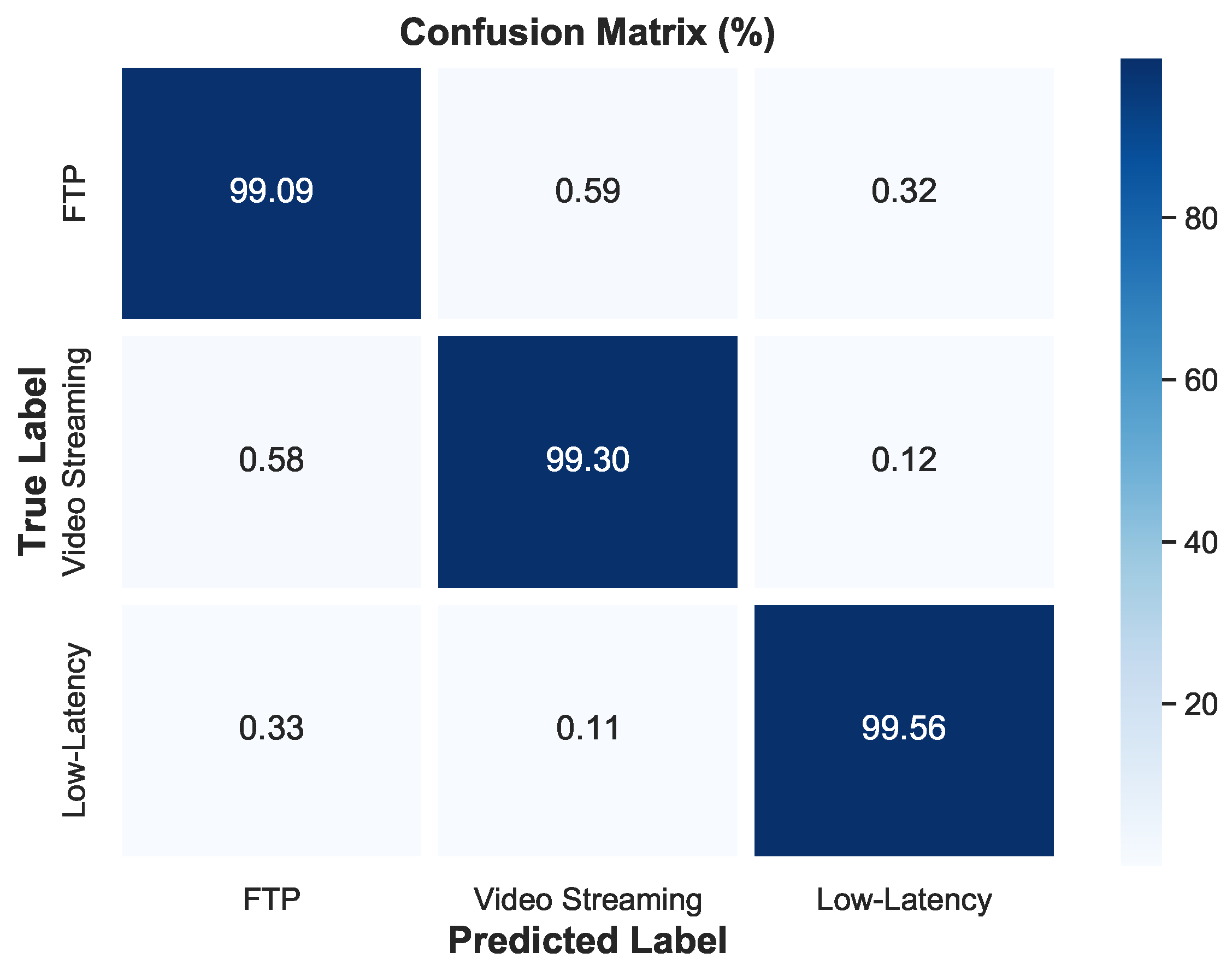

In the next experiment, our aim was to classify three distinct types of Internet traffic: FTP, video streaming, and low-latency traffic. The dataset used for training the classification algorithm was designed to maintain a balanced representation of each traffic type, with approximately one hour’s worth of sampling per category. The decision to utilize 14400 samples for each traffic type was deliberate. This sampling frequency, equivalent to an average of four samples per second over the course of an hour, allowed for a comprehensive representation of the behavior of each traffic category.

Table 4 presents the exact sample sizes for each traffic type, confirming the careful selection of our dataset, ensuring a balanced representation essential for robust model training and validation.

The deliberate selection of FTP, video streaming, and low-latency traffic was made to encompass a diverse representation of common Internet activities while maintaining a focused scope for the experiment. Accuracy results for our classification model are illustrated in

Figure 15, further supporting the exceptional performance with rates of 99.2% for FTP traffic, 99.3% for video streaming, and 99.4% for low-latency types, validating the effectiveness of our approach in accurately classifying these primary Internet traffic types.

Figure 15 presents the confusion matrix, visualizing the performance evaluation of the classification of the proposed models among different types of traffic.

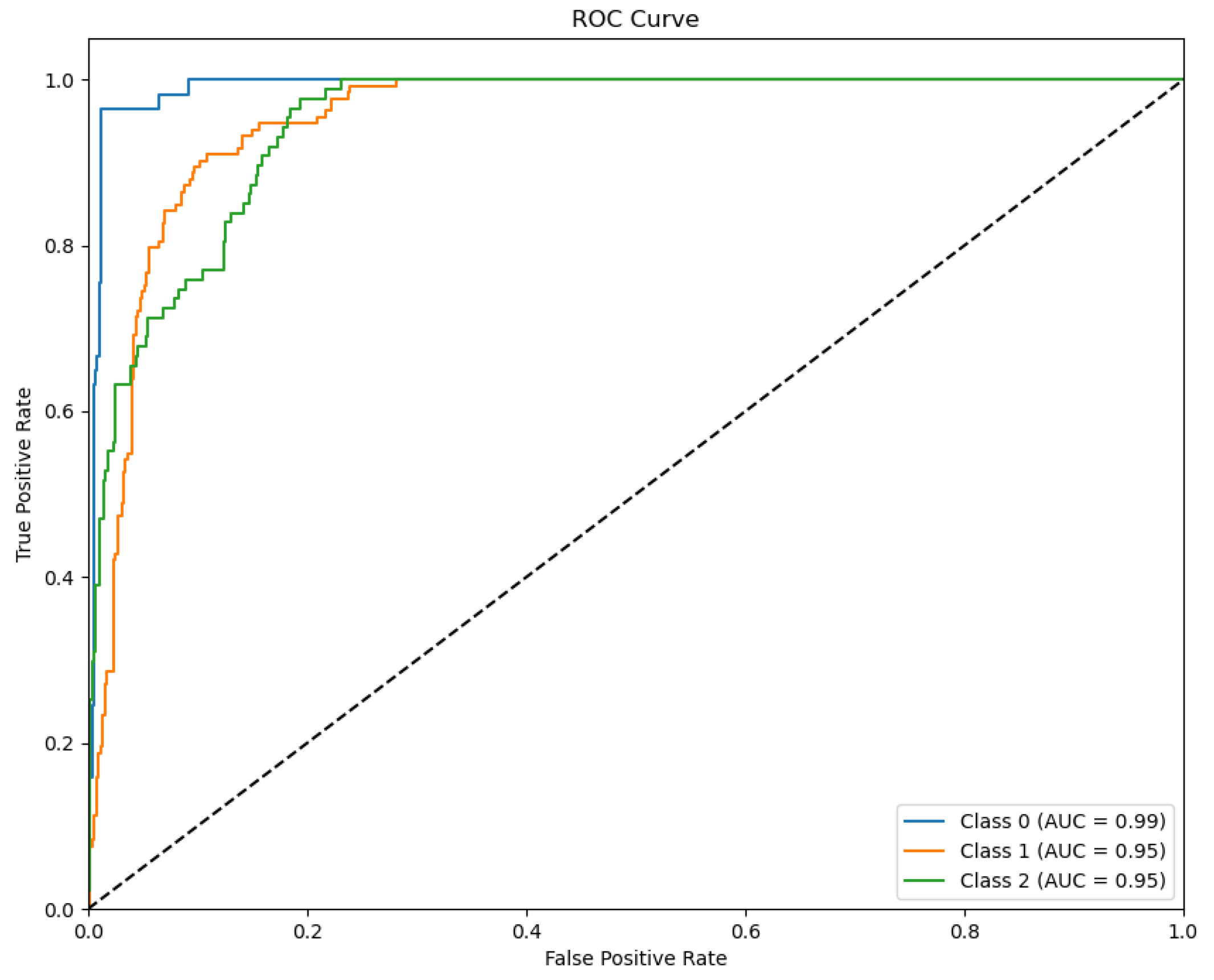

The ROC curve,

Figure 16, illustrates the model’s performance in terms of true positive rates and false positive rates for each traffic type. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) values show that the model achieved excellent classification performance across all three classes, with AUC values of 0.99 for FTP, and 0.95 for both video streaming and low-latency traffic.

In the following

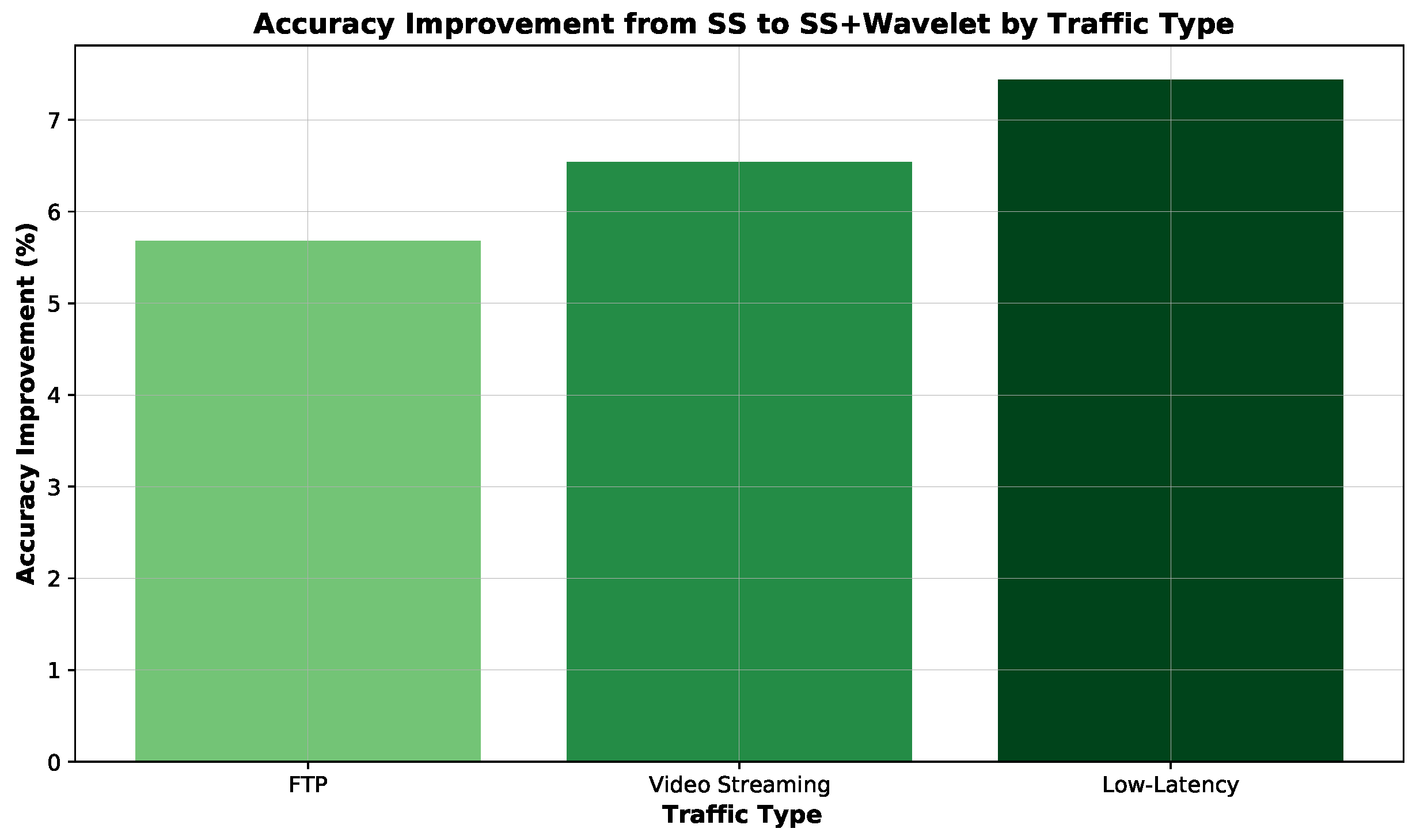

Figure 17 and

Table 5 demonstrate the benefit of incorporating wavelet transform into the model, we compared its performance against a standard scaling method (SS) across all traffic types. As can be seen, the application of the wavelet transform provided a significant improvement, particularly for low-latency traffic classification, where the accuracy increased by approximately 6% compared to using standard scaling methods alone. This improvement was also notable for FTP and video streaming, where the accuracy increased from 93.41% to 99.09% and from 92.76% to 99.30%, respectively. This demonstrates the wavelet transform’s effectiveness in enhancing feature extraction and improving overall classification performance, particularly in scenarios involving low-latency traffic.

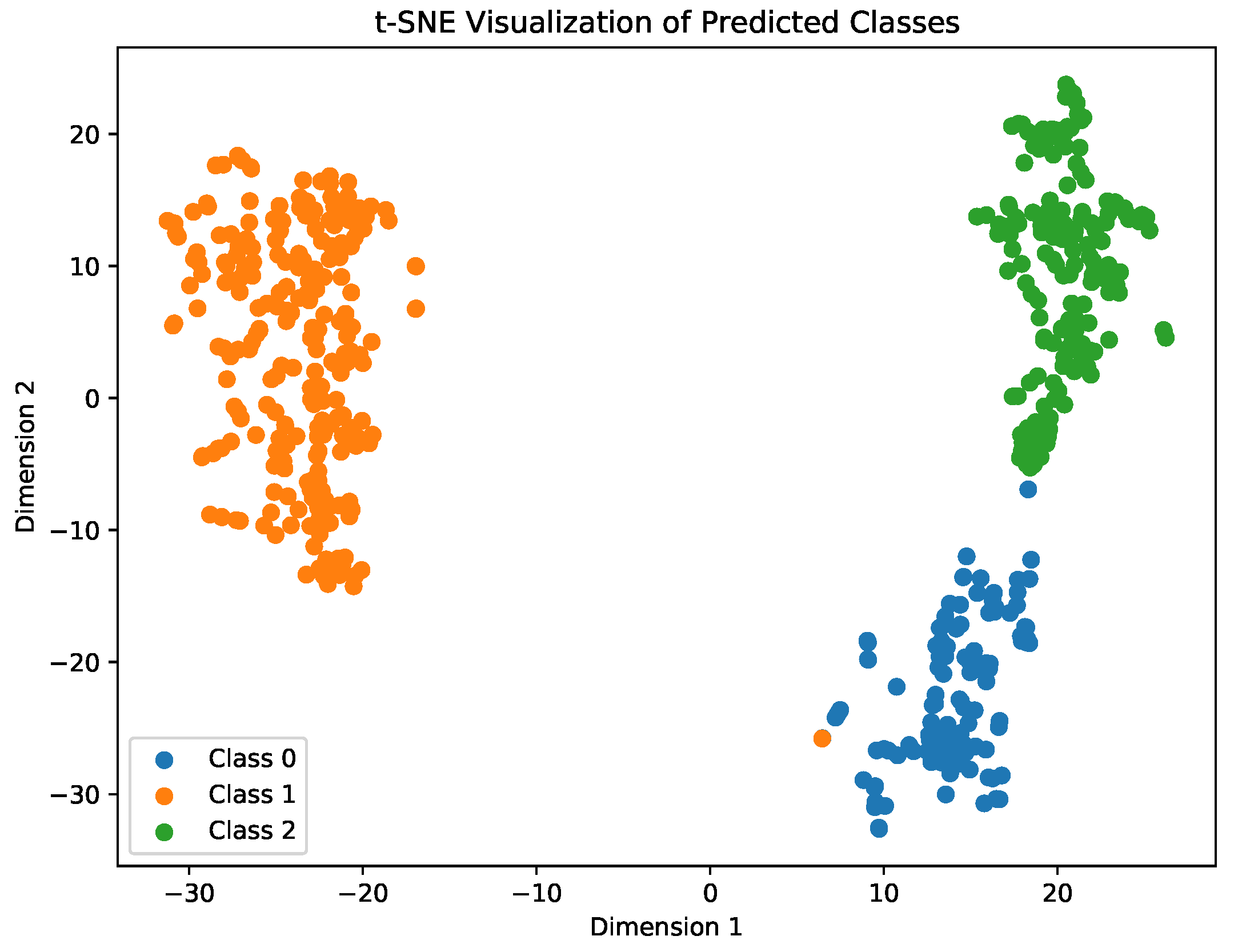

The t-SNE visualization in

Figure 18 portrays the distribution of predicted classes, FTP (Class 0), Video Streaming (Class 1), and Low-Latency (Class 2). Each distinct cluster in the plot corresponds to a class, revealing how the model separates and perceives these traffic types in a two-dimensional space. Overall, the plot provides a concise representation of the model’s segregation of these network behaviors into distinct categories with minimal overlap.

Table 6 presents a comparison of the classification accuracy achieved by various methods. This table highlights the performance of different methods, including solutions offered by other researchers, across three distinct traffic types: FTP, Video, and Low-Latency. In our previous paper [

6], we demonstrated high accuracy using the k-NN algorithm across all traffic types, while Wang et al.’s [

54] employment of CNN showed strong performance, especially in FTP and video classifications. Moreover, the utilization of Deep Packet [

43] with CNN yielded consistent accuracy rates of 98% across all traffic types. Chang et al.’s [

55] ANN model exhibited significant challenges in accurately classifying video traffic, registering a notably lower accuracy compared to other methods. The method proposed in this paper, employing an ANN approach, showcased remarkable accuracy rates of 99.1% in FTP and 99.6% in Low-Latency traffic classification, positioning it as a competitive solution among the state-of-the-art approaches for traffic classification in network analysis. Notably, FlowPic’s [

44] deployment of LSTM outperformed other methods with an exceptional 99.9% accuracy in Video traffic classification, underscoring the effectiveness of recurrent neural networks in handling sequential traffic data.

Figure 18.

Visualization of the predicted classes.

Figure 18.

Visualization of the predicted classes.

6. Conclusion

In this study, we have presented a novel approach for the classification and identification of low-latency Internet traffic using deep learning techniques and trend-based features. By incorporating advanced trend features such as slope, moving averages, download-to-upload ratio, and wavelet transform, we have demonstrated the effectiveness of our methodology in accurately classifying different types of Internet traffic. Experimental results have shown that our model achieved high accuracy rates of classifying FTP, video streaming, and low-latency traffic with 99.09% , 99.3% and 99.56%, respectively. These results validate the robustness and efficacy of our approach in accurately classifying primary Internet traffic types.

Furthermore, our experiments with mixed traffic scenarios, both basic and complex, have provided valuable insights into the performance of our model in real-world traffic mix situations. We observed that as the complexity and number of traffic types increased, the accuracy of identifying the existence of low-latency in the traffic mix decreased. However, our model still showed promising performance in detecting low-latency traffic within mixed traffic scenarios.

In general, the integration of wavelet transform and deep learning techniques has proven to be instrumental in enhancing the accuracy and precision of Internet traffic classification, particularly in the context of identifying low-latency traffic. Our findings contribute to the advancement of traffic analysis methodologies and have practical implications for optimizing the delivery of time-sensitive applications over the Internet.

In conclusion, our work underscores the significance of accurately identifying and prioritizing low-latency Internet traffic, and our proposed methodology offers a promising solution for addressing this critical aspect of network traffic management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.E. and V.R.; methodology, R.E and V.R.; software, R.E.; validation, R.E and V.R.; formal analysis, R.E and V.R.; investigation, R.E and V.R.; resources, R.E.; data curation, R.E and V.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.E and V.R..; writing—review and editing, R.E and V.R.; visualization, R.E and V.R.; supervision, V.R.; project administration, R.E and V.R.; funding acquisition, V.R.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of Turkey through a doctoral scholarship awarded to Ramazan Enisoglu.

Data Availability Statement

No data is being made available for the work presented in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Ramazan Enisoglu is a PhD candidate at City St George’s, University of London. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cisco. What is Low Latency? https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/solutions/data-center/data-center-networking/what-is-low-latency.html. Accessed: May 2, 2024.

- 3GPP. Service requirements for the 5G system. 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), Technical Specification (TS) 22.261 2019.

- Union, I.T. One-way transmission time. Recommendation G 2003, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Slyne, F.; Kaszubowska, A.; Ruffini, M. Virtualized EAST–WEST PON architecture supporting low-latency communication for mobile functional split based on multiaccess edge computing. Journal of Optical Communications and Networking 2020, 12, D109–D119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knieps, G. Internet of Things, future networks, and the economics of virtual networks. Competition and Regulation in Network Industries 2017, 18, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enisoglu, R.; Rakocevic, V. Low-Latency Internet Traffic Identification using Machine Learning with Trend-based Features. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC). IEEE; 2023; pp. 394–399. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, S.E.; Modafferi, S. Scalable classification of QoS for real-time interactive applications from IP traffic measurements. Computer networks 2016, 107, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirchoren, G.A.; Porrez, N.; La Sala, B.; Buraczewski, I. Quality of service in networks with self-similar traffic. In Proceedings of the 2017 XVII Workshop on Information Processing and Control (RPIC). IEEE; 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bentaleb, A.; Taani, B.; Begen, A.C.; Timmerer, C.; Zimmermann, R. A survey on bitrate adaptation schemes for streaming media over HTTP. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2018, 21, 562–585. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Z.; Wu, L.; Yu, Q.; Tan, X. Application of EMD combined with wavelet algorithm for filtering slag noise in steel cord conveyor belt. In Proceedings of the Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing, 2023, Vol. 2638, p. 012014.

- Habeeb, I.Q.; Fadhil, T.Z.; Jurn, Y.N.; Habeeb, Z.Q.; Abdulkhudhur, H.N. An ensemble technique for speech recognition in noisy environments. Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science 2020, 18, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wang, X.; Hanzo, L. A survey on wireless security: Technical challenges, recent advances, and future trends. Proceedings of the IEEE 2016, 104, 1727–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osadchiy, A.; Kamenev, A.; Saharov, V.; Chernyi, S. Signal processing algorithm based on discrete wavelet transform. Designs 2021, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Fang, W.; Qu, Y. Network traffic prediction algorithm based on wavelet transform. International Journal of Advancements in Computing Technology 2013, 5, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Cisco, U. Cisco annual internet report (2018–2023) white paper. Cisco: San Jose, CA, USA 2020, 10, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Drajic, D.; Krco, S.; Tomic, I.; Popovic, M.; Zeljkovic, N.; Nikaein, N.; Svoboda, P. Impact of online games and M2M applications traffic on performance of HSPA radio access networks. In Proceedings of the 2012 Sixth International Conference on Innovative Mobile and Internet Services in Ubiquitous Computing. IEEE; 2012; pp. 880–885. [Google Scholar]

- Sander, C.; Kunze, I.; Wehrle, K.; Rüth, J. Video conferencing and flow-rate fairness: a first look at Zoom and the impact of flow-queuing AQM. In Proceedings of the Passive and Active Measurement: 22nd International Conference, PAM 2021, Virtual Event, March 29–April 1, 2021, Proceedings 22. Springer; 2021; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rajadurai, S.; Alazab, M.; Kumar, N.; Gadekallu, T.R. Latency evaluation of SDFGs on heterogeneous processors using timed automata. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 140171–140180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finsterbusch, M.; Richter, C.; Rocha, E.; Muller, J.A.; Hanssgen, K. A survey of payload-based traffic classification approaches. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2013, 16, 1135–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Armitage, G. A survey of techniques for internet traffic classification using machine learning. IEEE communications surveys & tutorials 2008, 10, 56–76. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, O.; Elhajj, I.H.; Kayssi, A.; Chehab, A. A review on machine learning–based approaches for Internet traffic classification. Annals of Telecommunications 2020, 75, 673–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adje, E.A.; Houndji, V.R.; Dossou, M. Features analysis of internet traffic classification using interpretable machine learning models. IAES International Journal of Artificial Intelligence 2022, 11, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deri, L.; Sartiano, D. Monitoring IoT Encrypted Traffic with Deep Packet Inspection and Statistical Analysis. 2020 15th International Conference for Internet Technology and Secured Transactions (ICITST) 2020, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Manju, N.; Harish, B.; Nagadarshan, N. Multilayer Feedforward Neural Network for Internet Traffic Classification. Int. J. Interact. Multim. Artif. Intell. 2020, 6, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandait, P.; Hubballi, N.; Mazumdar, B. Efficient Keyword Matching for Deep Packet Inspection based Network Traffic Classification. 2020 International Conference on COMmunication Systems & NETworkS (COMSNETS) 2020, pp. 567–570. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.P.; Barbar, J.S.; Soares, A.S. Multilayer perceptron and stacked autoencoder for Internet traffic prediction. In Proceedings of the Network and Parallel Computing: 11th IFIP WG 10.3 International Conference, NPC 2014, Ilan, Taiwan, September 18-20, 2014. Proceedings 11. Springer; 2014; pp. 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Aswad, S.A.; Sonuç, E. Classification of VPN network traffic flow using time related features on Apache Spark. In Proceedings of the 2020 4th International Symposium on Multidisciplinary Studies and Innovative Technologies (ISMSIT). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ishak, S.; Alecsandru, C. Optimizing traffic prediction performance of neural networks under various topological, input, and traffic condition settings. Journal of transportation engineering 2004, 130, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiodun, O.I.; Jantan, A.; Omolara, A.E.; Dada, K.V.; Umar, A.M.; Linus, O.U.; Arshad, H.; Kazaure, A.A.; Gana, U.; Kiru, M.U. Comprehensive review of artificial neural network applications to pattern recognition. IEEE access 2019, 7, 158820–158846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Shapira, T.; Shavitt, Y. Fast and lean encrypted Internet traffic classification. Computer Communications 2022, 186, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertam, F.; Avcı, E. A new approach for internet traffic classification: GA-WK-ELM. Measurement 2017, 95, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salagean, M.; Firoiu, I. Anomaly detection of network traffic based on analytical discrete wavelet transform. In Proceedings of the 2010 8th International Conference on Communications. IEEE; 2010; pp. 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gál, Z.; Terdik, G. Wavelet analysis of QoS based network traffic. In Proceedings of the 2011 6th IEEE International Symposium on Applied Computational Intelligence and Informatics (SACI). IEEE; 2011; pp. 275–280. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, C.; Wu, W. Efficient and robust feature extraction and selection for traffic classification. Computer Networks 2017, 119, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, Q. Balanced feature selection method for Internet traffic classification. IET networks 2012, 1, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, G.; Qassrawi, M.T.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, X. Feature selection for optimizing traffic classification. Computer Communications 2012, 35, 1457–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Chen, T.; Su, Y.; Li, C. Internet traffic classification based on incremental support vector machines. Mobile Networks and Applications 2018, 23, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.; Qu, Y.R.; Prasanna, V.K. Accelerating decision tree based traffic classification on FPGA and multicore platforms. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2017, 28, 3046–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Gupta, A.; Kountanis, D. Optimizing an artificial immune system algorithm in support of flow-Based internet traffic classification. Applied Soft Computing 2017, 54, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotti, M.; Dusi, M.; Gringoli, F.; Salgarelli, L. Traffic classification through simple statistical fingerprinting. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review 2007, 37, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Parish, D.J. Optimised multi-stage tcp traffic classifier based on packet size distributions. In Proceedings of the 2010 Third International Conference on Communication Theory, Reliability, and Quality of Service. IEEE; 2010; pp. 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, T.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Guan, X. Robust application identification methods for P2P and VoIP traffic classification in backbone networks. Knowledge-Based Systems 2015, 82, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfollahi, M.; Jafari Siavoshani, M.; Shirali Hossein Zade, R.; Saberian, M. Deep packet: A novel approach for encrypted traffic classification using deep learning. Soft Computing 2020, 24, 1999–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapira, T.; Shavitt, Y. Flowpic: Encrypted internet traffic classification is as easy as image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2019-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS). IEEE; 2019; pp. 680–687. [Google Scholar]

- Draper-Gil, G.; Lashkari, A.H.; Mamun, M.S.I.; Ghorbani, A.A. Characterization of encrypted and vpn traffic using time-related. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on information systems security and privacy (ICISSP); 2016; pp. 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Lashkari, A.H.; Gil, G.D.; Mamun, M.S.I.; Ghorbani, A.A. Characterization of tor traffic using time based features. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy. SciTePress; 2017; Vol. 2, pp. 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Kontogeorgaki, S.; Sánchez-García, R.J.; Ewing, R.M.; Zygalakis, K.C.; MacArthur, B.D. Noise-processing by signaling networks. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammedi, R. A DEEP LEARNING BASED TRAFFIC CLASSIFICATION IN SOFTWARE DEFINED NETWORKING. 14th IADIS International Conference Information Systems 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, G.S.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; et al. Tensorflow: Largescale machine learning on heterogeneous systems. https://www.tensorflow.org/?hl=tr. Accessed: 2023-10-25.

- White, G.; Sundaresan, K.; Briscoe, B. Low latency docsis: Technology overview. Research & Development 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Theisen, R.; Hodgkinson, L.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Ramchandran, K.; Martin, C.H.; Mahoney, M.W. Test accuracy vs. generalization gap: Model selection in nlp without accessing training or testing data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2023, pp. 3011–3021.

- Du, X.; Xu, H.; Zhu, F. Understanding the effect of hyperparameter optimization on machine learning models for structure design problems. Computer-Aided Design 2021, 135, 103013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.J.; Walters, S.D.; Petridis, M.; Malekshahi Gheytassi, S.; Morgan, R.E. Accelerated optimal topology search for two-hidden-layer feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Applications of Neural Networks. Springer; 2016; pp. 253–266. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, M.; Wang, J.; Zeng, X.; Yang, Z. End-to-end encrypted traffic classification with one-dimensional convolution neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE international conference on intelligence and security informatics (ISI). IEEE; 2017; pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.H.; Lee, T.H.; Chu, H.C.; Su, C.W. Application-based online traffic classification with deep learning models on SDN networks. Adv. Technol. Innov 2020, 5, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

System Architecture.

Figure 1.

System Architecture.

Figure 2.

Parallel Patterns: (a) Low-latency traffic and (b) gaussian noise.

Figure 2.

Parallel Patterns: (a) Low-latency traffic and (b) gaussian noise.

Figure 3.

Parallel Distributions: (a) Gaussian noise and (b) low-latency traffic.

Figure 3.

Parallel Distributions: (a) Gaussian noise and (b) low-latency traffic.

Figure 4.

Features from time domain to wavelet domain.

Figure 4.

Features from time domain to wavelet domain.

Figure 5.

Throughput in wavelet domain.

Figure 5.

Throughput in wavelet domain.

Figure 6.

Ratio in wavelet domain.

Figure 6.

Ratio in wavelet domain.

Figure 7.

Throughput of YouTube traffic.

Figure 7.

Throughput of YouTube traffic.

Figure 8.

Moving average of YouTube traffic.

Figure 8.

Moving average of YouTube traffic.

Figure 9.

Downlink/Uplink througput ratio.

Figure 9.

Downlink/Uplink througput ratio.

Figure 10.

Slope of throughput for downlink and uplink traffic.

Figure 10.

Slope of throughput for downlink and uplink traffic.

Figure 11.

Overview of the MLP based ANN classifier.

Figure 11.

Overview of the MLP based ANN classifier.

Figure 12.

Confusion matrix of complex scenarios.

Figure 12.

Confusion matrix of complex scenarios.

Figure 13.

Impact of wavelet transform on classification accuracy in complex traffic scenarios.

Figure 13.

Impact of wavelet transform on classification accuracy in complex traffic scenarios.

Figure 14.

Impact of wavelet transform on classification accuracy.

Figure 14.

Impact of wavelet transform on classification accuracy.

Figure 15.

Confusion matrix of the model.

Figure 15.

Confusion matrix of the model.

Figure 17.

Accuracy improvement of single traffic types.

Figure 17.

Accuracy improvement of single traffic types.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter tuning for ANN model.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter tuning for ANN model.

| Hyperparameters |

Range |

Selection |

| Number of hidden layers |

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5] |

2 |

| Activation Function |

[sigmoid, tanh, ReLU] |

ReLU |

| Learning Rate |

[0.1, 0.01, 0.001] |

0.001 |

| Batch Size |

[16, 32, 64, 128] |

32 |

| Number of Epochs |

[10, ..., 50, ..., 150] |

100 |

| Optimizer |

[Adam] |

Adam |

| Dropout Rate |

[0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5] |

0 |

Table 2.

Basic traffic scenarios.

Table 2.

Basic traffic scenarios.

| Mixed Traffic Scenarios (Basic) |

|---|

| Traffic Scenario |

Low-Latency |

Accuracy (%)∼ |

| A+B |

NO |

89.7 |

| A+C |

YES |

92.8 |

| B+C |

YES |

94.2 |

| A+A |

NO |

88.3 |

| B+B |

NO |

90.6 |

| C+C |

YES |

96.5 |

| A = File Transfer , B = Video Streaming , C = Low-Latency |

Table 3.

Complex traffic scenarios.

Table 3.

Complex traffic scenarios.

| Mixed Traffic Scenarios (Complex) |

|---|

| No |

Scenario |

Low-Latency |

Acc (%)∼ |

Acc (%)∼with WT

|

| 1 |

3A |

NO |

82.9 |

86.8 |

| 2 |

3B |

NO |

83.6 |

88.2 |

| 3 |

3C |

YES |

88.2 |

93.2 |

| 4 |

2A+B |

NO |

77.2 |

82.1 |

| 5 |

A+2B |

NO |

71.1 |

77.4 |

| 6 |

2A+C |

YES |

76.5 |

83.2 |

| 7 |

A+2C |

YES |

79.6 |

83.8 |

| 8 |

2B+C |

YES |

77.0 |

84.1 |

| 9 |

B+2C |

YES |

80.7 |

84.4 |

| 10 |

A+B+C |

YES |

72.9 |

78.2 |

| 11 |

2A+B+C |

YES |

68.8 |

74.2 |

| 12 |

A+2B+C |

YES |

69.7 |

75.3 |

| 13 |

A+B+2C |

YES |

72.5 |

79.2 |

| |

A = File Transfer , B = Video Streaming , C = Low-Latency |

Table 4.

Traffic types and exact sample sizes.

Table 4.

Traffic types and exact sample sizes.

| Traffic Type |

Duration |

Total Samples |

| FTP |

∼1 Hour |

14679 |

| Video Streaming |

∼1 Hour |

14287 |

| Low-Latency |

∼1 Hour |

14510 |

Table 5.

Impact of wavelet transform on classification.

Table 5.

Impact of wavelet transform on classification.

| Traffic Type |

Scaling Method |

Classification Accuracy(%)∼ |

| FTP |

SS |

93.41 |

| SS+Wavelet |

99.09 |

| Video Streaming |

SS |

92.76 |

| SS+Wavelet |

99.30 |

| Low-Latency |

SS |

92.12 |

| SS+Wavelet |

99.56 |

Table 6.

Classification performance comparison among six methods. Results are in the format of Avg.

Table 6.

Classification performance comparison among six methods. Results are in the format of Avg.

| Paper |

Algorithm |

Classification Accuracy(%)∼ |

| FTP |

Video |

Low-Latency |

| Enisoglu et al.[6] |

k-NN |

97.5 |

97.9 |

98.2 |

| Wang et al. [54] |

CNN |

94.5 |

96.5 |

84.5 |

| Deep Packet [43] |

CNN |

98.0 |

98.0 |

98.0 |

| Chang et al. [55] |

ANN |

NA |

59.0 |

92.0 |

| FlowPic [44] |

LSTM |

98.8 |

99.9 |

99.6 |

| This Paper |

ANN |

99.1 |

99.3 |

99.6 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).