1. Introduction

Traffic classification plays a vital role in network traffic anomaly detection and intrusion detection systems. It is also a fundamental component of network management, particularly in the domain of cybersecurity. The process of associating network traffic with specific applications is referred to as traffic classification (TC). As a key function, traffic classification underpins various network activities-from traffic shaping and policy enforcement to security mechanisms like filtering, intrusion prevention, and anomaly detection. Accurate classification not only facilitates quality-of-service (QoS) optimization but also supports forensic analysis and threat intelligence in enterprise and critical infrastructure networks.

Given the increasing complexity and heterogeneity of modern internet traffic, alongside growing demands for extracting meaningful insights from user data, traffic classification has become both more necessary and more challenging. The rapid evolution of application-layer protocols, the prevalence of mobile and IoT devices, and the emergence of adaptive or obfuscation-based communication methods all contribute to making traffic patterns more variable and less predictable. Furthermore, the widespread adoption of encryption protocols such as TLS 1.3 and QUIC presents significant obstacles for traditional traffic classification methods by concealing payload contents and rendering payload inspection techniques largely ineffective.

A wide range of techniques has been developed for traffic classification [

1], including port-based matching, deep packet inspection (DPI), statistical feature analysis, behavioral analysis, and machine learning (ML)-based approaches. However, the effectiveness of port-based methods has declined sharply due to the prevalence of dynamic, multiplexed, or obfuscated port assignments. DPI approaches, while once dominant, are increasingly constrained by legal limitations, computational overhead, and encryption. While traditional ML methods offer improvements over rule-based systems-particularly in their ability to handle encrypted traffic and reduce reliance on payload content-they often depend heavily on manual feature engineering and exhibit limited adaptability to dynamic or previously unseen network behaviors.

To overcome these limitations, recent studies have applied deep learning to traffic classification. Deep learning models can automatically extract structured feature representations from raw data, enabling end-to-end training and improved generalization to new or evolving traffic patterns. Notable achievements include the use of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for unencrypted traffic classification, with performance metrics such as accuracy, recall, and F1-score all exceeding 89% [

3]. Other research [

5] has demonstrated that combining long short-term memory (LSTM) networks with 2D-CNN architectures can further enhance performance, achieving up to 96.32% accuracy and 95.74% F1-score. Hybrid models that integrate multiple neural architectures, as well as multitask learning systems that simultaneously optimize for different traffic-related tasks, have also been proposed to improve robustness and scalability [

6,

7,

8].

Despite these advances, most existing deep learning models rely on a single data modality-such as packet sequences or flow-level statistics-and fail to fully utilize the heterogeneity inherent in traffic data. This shortcoming limits their ability to model cross-modal dependencies and often reduces their generalizability and precision in complex, real-world environments. To address this, we propose a multimodal traffic classification framework that integrates diverse modalities-such as time series features, statistical summaries, and protocol metadata-into a unified deep learning model. By fusing complementary information sources, the proposed approach aims to improve feature representation quality, capture richer semantic structures, and enhance overall classification performance, especially in dynamic and encrypted traffic scenarios.

2. Related Work

Recent progress in deep learning has significantly enhanced traffic classification, particularly when addressing encrypted and heterogeneous traffic data. Contextual sequence modeling frameworks have shown promise using hybrid architectures such as BERT-BiLSTM for semantic interpretation and classification tasks [

9]. General-purpose multi-task learning models have further improved task adaptability and instruction coordination in diverse domains [

10].

Multivariate time series classification via graph neural networks and Transformer architectures has demonstrated effective learning from temporal dependencies-strategies relevant to network traffic data structured as packet sequences [

11]. Reinforcement learning, particularly through Double DQN, has been applied to optimize scheduling tasks dynamically, offering insights into policy-based adaptation mechanisms suitable for real-time traffic analysis [

12].

The integration of multimodal features has become central to enhancing classification precision. Approaches that fuse CNN and Transformer-based representations for image-text data have shown the power of cross-modal learning [

13], while attention mechanisms and multi-scale fusion techniques in Transformer models have proven effective in extracting hierarchical features [

14].

Generative deep learning methods such as diffusion models have been explored for automated UI generation, demonstrating the capacity to model structured semantics and improve personalization in data synthesis tasks [

15]. In distributed systems, scheduling algorithms for data stream computing and spatial voice interaction highlight dynamic adaptability and efficiency optimization for real-time environments [

16,

17].

Intelligent data acquisition systems have benefited from context-aware adaptive sampling using DQN, facilitating efficient and relevant information capture under limited bandwidth scenarios [

18]. Low-rank adaptation techniques have also been revisited to enhance model scalability and reduce training overhead, which is critical for deployment in high-throughput traffic classification systems [

19].

Temporal-spatial deep learning frameworks have been developed for resource forecasting in cloud-based environments, emphasizing structural modeling of time-variant system behavior [

20]. Deep probabilistic models based on mixture density networks further contribute to anomaly detection by modeling uncertainty and behavior distribution [

21].

For structured sequence classification tasks, hybrid models using BiLSTM-CRF and social contextual integration have proven effective in boundary detection and segmentation [

22]. Lastly, semantic modeling of multi-hop relationships in heterogeneous networks has shown potential for improving relational reasoning, which aligns with the hierarchical and interconnected nature of network traffic features [

23].

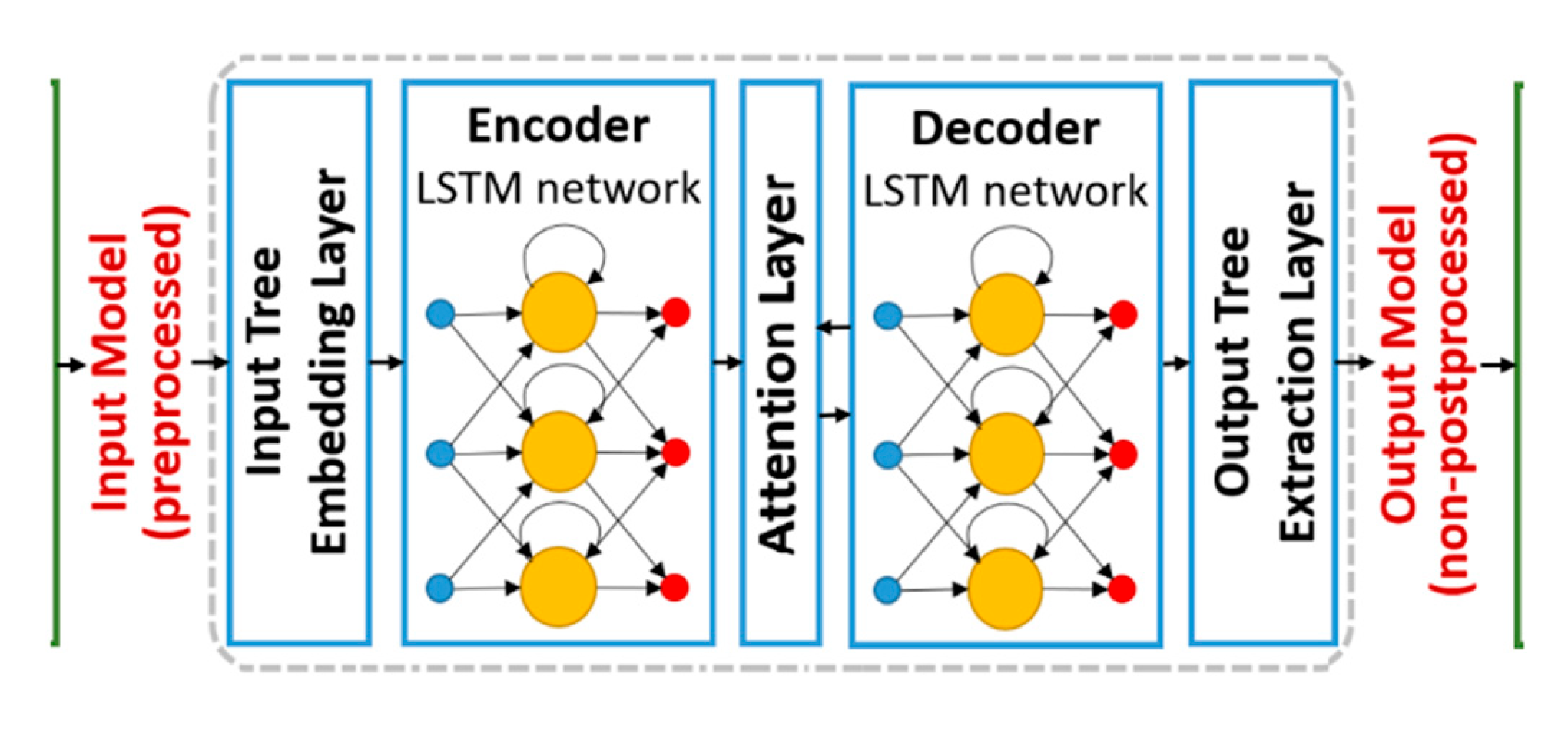

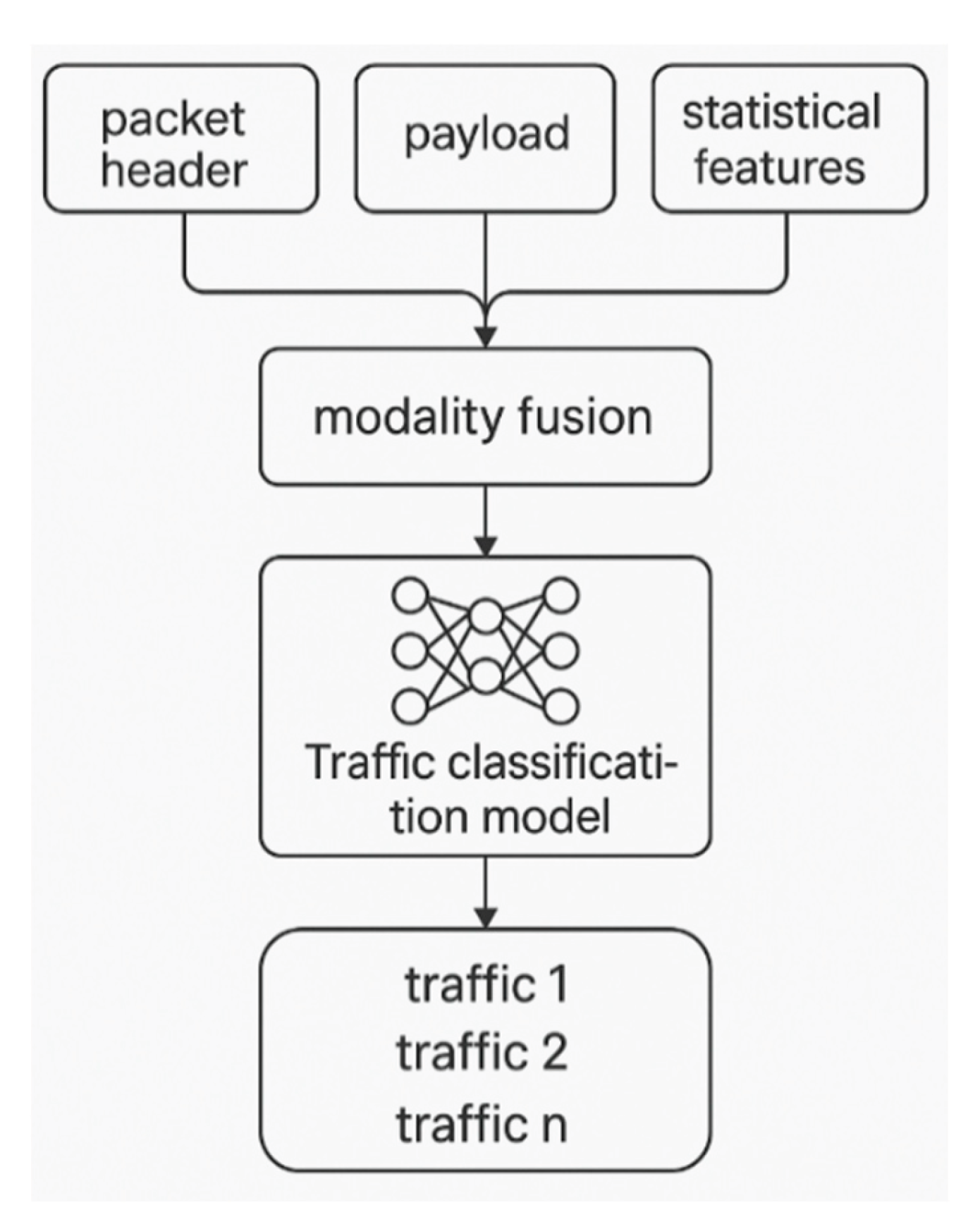

3. Multimodal Deep Learning-Based Method for Traffic Detection and Classification

A. Multimodal Traffic Data Analysis

Multimodal fusion technology (MFT) in deep learning refers to the process of analyzing and recognizing tasks by utilizing inputs from multiple heterogeneous data types. By integrating different data modalities-such as raw payloads, protocol headers, temporal features, and statistical patterns-MFT mitigates inter-modal heterogeneity and provides a richer, more comprehensive understanding of the underlying data. This integrative process enhances the decision-making accuracy of deep learning models, particularly in complex classification scenarios where single-modality inputs may lack sufficient discriminative power. Consequently, MFT has emerged as a prominent and rapidly advancing research direction in the field of deep learning and intelligent data analysis.

In this section, we begin by analyzing the fundamental input units typically employed in conventional traffic classifiers. These classifiers often operate on segmented units of traffic-most commonly packet flows-that serve as the basic granularity for feature extraction and model training. We then discuss the various types of data that can be extracted from a single traffic unit, including payload content, header metadata, temporal packet characteristics, and statistical aggregates. In the proposed framework, each modality (i.e., distinct input types derived from the same traffic flow unit) is processed through a dedicated neural network branch. These independently processed features are then fused through a joint representation layer, enabling synergistic learning that improves the overall classification performance. This architecture facilitates robust multimodal analysis and allows for more effective recognition of complex traffic patterns in diverse network conditions.

Traffic segmentation is a critical preprocessing step that divides continuous raw traffic data into discrete and analyzable flow units suitable for input to classification models. As defined in [

3], a “flow” is typically described using a five-tuple: source IP address, source port, destination IP address, destination port, and transport-layer protocol. To capture the bidirectional nature of real-world communication, the concept of a “biflow” is often employed-this includes both forward and reverse packet streams associated with the same five-tuple. The study in [

3] empirically demonstrated that biflows offer more contextual information and achieve higher classification accuracy compared to unidirectional flows, particularly for application-layer inference.

Contemporary deep learning-based traffic classification models have adopted various strategies for structuring input data. One common approach involves extracting a fixed-length byte segment from each flow-for instance, [

3] extracts the first 784 bytes from each flow’s payload, encompassing data from application-layer (L7) or full-stack protocol layers. Another approach, introduced in [

5], selects protocol field-level features from the first 20 packets in a biflow and constructs a matrix representation. This matrix comprises six key features per packet: source and destination ports, payload size, TCP window size, inter-arrival time, and packet direction, forming a structured 20×6 matrix that captures both temporal and contextual traffic characteristics.

Although network traffic data inherently consists of multiple complementary modalities, many existing classification models are limited to a single modality-often focusing exclusively on either payload or protocol header fields. This narrow perspective restricts the model’s ability to fully exploit the wealth of information embedded in network flows, especially when dealing with encrypted, obfuscated, or multiplexed traffic. To address these limitations, the next section introduces a novel multimodal deep learning classification model. This model is designed to automatically learn and integrate heterogeneous traffic representations across modalities. By explicitly modeling both intra-modal patterns (within each feature type) and inter-modal relationships (across different types), the framework is capable of capturing richer traffic semantics and achieving greater robustness. This approach enables the classifier to better generalize across diverse network environments, ultimately overcoming the representational limitations of conventional single-modality models

4. Experiments and Result Analysis

A. Description of the Simulated Dataset

This study adopts the ISCX VPN-nonVPN traffic dataset used in [

24], which contains both flow features and raw packet captures (PCAP format). The dataset includes 12 traffic categories: 6 classes of regular encrypted traffic and 6 classes of VPN-encapsulated traffic. There are 20,173 non-VPN samples and 12,264 VPN samples, totaling 32,437 flow units.

B. Sample Preprocessing

The choice of flow segmentation granularity significantly impacts the quality of traffic classification. In this study, biflows are adopted as the basic unit. The transformation from raw traffic data to biflow units is carried out as follows:

Raw Traffic Packets: All packets form a collection P={p1,p2,...,pn}, where each packet pi=(f,l,t), with f representing the five-tuple (source IP, source port, destination IP, destination port, and transport protocol), l the packet length in bytes, and t the timestamp of transmission.

Conversion to Biflows: The packet set P is partitioned into subsets R={r1,r2,...,rN}, where each biflow ri contains packets with matching five-tuples (regardless of direction) and is ordered by timestamp. Each biflow is represented as Ri=(f,L,T,t0) , where L is the size of all packets, T the duration, and t₀ the starting time of the first packet.

For each biflow, two different input modalities are used:

Modality I: "L7-Nb", which consists of the first

Nb bytes of the application-layer (L7) payload [

5].

Modality II: "MAT-Np-[

5]", referring to the first

Np packets of each biflow. Each packet contributes four protocol-related features—payload size, TCP window size, inter-arrival time, and packet direction—forming an

Np×4 matrix. Unlike [

5], port numbers are omitted to reduce potential bias.

To simplify feature selection while maintaining classification fidelity, the study uses the application payload from biflow packets. Based on empirical analysis, we select Nb = 576 bytes for Modality I and Np = 12 packets for Modality II.

5. Conclusions

This study proposes a traffic classification method based on multimodal deep learning, integrating convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and long short-term memory (LSTM) networks. The approach effectively leverages the heterogeneous and multimodal characteristics of traffic data. By separately processing different modalities—specifically, payload bytes and protocol-level features—from the same traffic unit and then fusing the learned representations, the method achieves more accurate classification outcomes. Compared with existing deep learning-based classifiers that rely solely on single-modality inputs, the proposed framework significantly improves adaptability and precision, addressing the limitations of traditional models in dynamic and complex network environments.

References

- G. Aceto, D. G. Aceto, D. Ciuonzo, A. Montieri, and A. Pescapé, “MIMETIC: Mobile encrypted traffic classification using multimodal deep learning,” Computer Networks, vol. 165, Art. 106944, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- G. Aceto, D. Ciuonzo, A. Montieri, and A. Pescapé, “Encrypted traffic classification via multimodal multitask deep learning: The Distiller classifier,” Computer Networks, vol. 148, pp. 164–180, Jan. 2019.

- S. Rezaei and X. Liu, “Deep learning for encrypted traffic classification: An overview,” IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 57, no. 5, pp. 76–81, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Hussain Kalwar and S. Bhatti, “Deep learning approaches for network traffic classification in the Internet of Things: A survey,” arXiv preprint. Feb. 2024. arXiv:2402.00920.

- B. Pang, Y. Fu, S. Ren, Y. Wang, Q. Liao, and Y. Jia, “CGNN: Traffic classification with graph neural network,” arXiv preprint. Oct. 2021. arXiv:2110.14448.

- Z. Chen, K. He, and J. Li, “Seq2Img: A sequence-to-image based approach towards IP traffic classification using convolutional neural networks,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Big Data, Boston, MA, USA, 2017, pp. 1271–1276. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, M. Zhu, X. Zeng, X. Ye, and Y. Sheng, “Malware traffic classification using convolutional neural network for representation learning,” in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. on Computer and Information Technology (CIT), Helsinki, Finland, 2017, pp. 754–759. [CrossRef]

- M. López-Martín, B. Carro, A. Sánchez-Esguevillas, and J. Lloret, “Network traffic classifier with convolutional and recurrent neural networks for Internet of Things,” IEEE Access, vol. 5, pp. 18042–18050, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z., Zhang, H., He, J., Qi, Z., & Zheng, H. (2025, March). Semantic and Contextual Modeling for Malicious Comment Detection with BERT-BiLSTM. In 2025 4th International Symposium on Computer Applications and Information Technology (ISCAIT) (pp. 1867–1871). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Xu, Z., Tian, Y., Wu, Y., Wang, M., & Meng, X. (2025). Unified Instruction Encoding and Gradient Coordination for Multi-Task Language Models. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. (2024). Multivariate Time Series Forecasting and Classification via GNN and Transformer Models. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 3(9). [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Duan, Y., Deng, Y., Guo, F., Cai, G., & Peng, Y. (2025, March). Dynamic operating system scheduling using double DQN: A reinforcement learning approach to task optimization. In 2025 8th International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Control Engineering (ICAACE) (pp. 1492–1497). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Hao, R., Shi, S., Yu, Z., He, Q., & Zhan, J. (2025, March). A CNN-Transformer Approach for Image-Text Multimodal Classification with Cross-Modal Feature Fusion. In 2025 8th International Conference on Advanced Algorithms and Control Engineering (ICAACE) (pp. 1182–1186). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Y., He, Q., Xu, T., Hao, R., Hu, J., & Zhang, H. (2025). Adaptive Transformer Attention and Multi-Scale Fusion for Spine 3D Segmentation. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2503.12853.

- Duan, Y., Yang, L., Zhang, T., Song, Z., & Shao, F. (2025, March). Automated UI Interface Generation via Diffusion Models: Enhancing Personalization and Efficiency. In 2025 4th International Symposium on Computer Applications and Information Technology (ISCAIT) (pp. 780–783). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. (2025). Dynamic Distributed Scheduling for Data Stream Computing: Balancing Task Delay and Load Efficiency. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 4(1).

- Sun, Q. (2025). Spatial Hierarchical Voice Control for Human-Computer Interaction: Performance and Challenges. Journal of Computer Technology and Software, 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Huang, W., Zhan, J., Sun, Y., Han, X., An, T., & Jiang, N. (2025). Context-Aware Adaptive Sampling for Intelligent Data Acquisition Systems Using DQN. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2504.09344.

- Wang, Y., Fang, Z., Deng, Y., Zhu, L., Duan, Y., & Peng, Y. (2025). Revisiting LoRA: A Smarter Low-Rank Approach for Efficient Model Adaptation. arXiv preprint (not available).

- Aidi, K., & Gao, D. (2025). Temporal-Spatial Deep Learning for Memory Usage Forecasting in Cloud Servers. [CrossRef]

- Dai, L., Zhu, W., Quan, X., Meng, R., Cai, S., & Wang, Y. (2025). Deep Probabilistic Modeling of User Behavior for Anomaly Detection via Mixture Density Networks. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2505.08220.

- Zhao, Y., Zhang, W., Cheng, Y., Xu, Z., Tian, Y., & Wei, Z. (2025). Entity Boundary Detection in Social Texts Using BiLSTM-CRF with Integrated Social Features. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H., Xing, Y., Zhu, L., Han, X., Du, J., & Cui, W. (2025). Modeling Multi-Hop Semantic Paths for Recommendation in Heterogeneous Information Networks. arXiv preprint. arXiv:2505.05989.

- N. Bayat, W. Jackson, and D. Liu, “Deep learning for network traffic classification,” arXiv preprint. Jun. 2021. arXiv:2106.12693.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).