1. Introduction

Environmental constitutionalism (EC) is a relatively recent phenomenon in the national legal systems worldwide. The EC is a transformative process that constitutionally guarantees and protects enforcement of various environmental rights.1 The EC guarantees and protects environmental rights from two distinct but related viewpoints. One aspect of the environmental rights is the civic rights of the people to live in a clean, hygienic and healthy environment where there is clean and unpolluted air to breath, potable water from natural water bodies to drink, open space such as parks and gardens for recreation, and equitable opportunity for sustainable development. 2 This aspect of environmental rights is considered as people’s right to environment that is further categorized by transformative process of EC into substantive environmental rights (SER) and procedural environmental rights (PER). The SER is the typical constitutional guarantee and protection of basic and fundamental environmental rights of the people that is protected against actions of mighty limbs of the governments and its agencies.3 The SER imposes two-fold duty on the governments and its agencies; first, the governments and its agencies are duty bound not to make laws, rules, regulations and orders that may take away opportunity from the people to enjoy their basic and fundamental environmental rights that are guaranteed and protected within the constitutional texts; second, governments and its agencies are also duty bound to make laws, rules, regulations and orders for providing opportunity to the people to enjoy their basic and fundamental environmental rights that are guaranteed and protected within the constitutional texts, simultaneously. Further, the PER is another category of constitutionally guaranteed and protected people’s right to environment that includes catena of rights for the enforcement of the SER.4 The PER and the SER are the two sides of the same coin. The PER is as important as the SER, since the substantive rights have no values unless there is stable and sturdy procedural rights for redressal of substantive rights. The PER consists trinity of rights that includes the people’s right to periodically receive reliable environmental information possessed by authorities established by law; people’s right to effectively participate in the environmental decision making process of public and private entities by submitting their spatial observations and raising queries during the process; and people’s right to bring environmentally malign public and private activities before the justice.

Other and most important facet of the environmental rights within the span of the EC is the autonomous rights of the environment inter alia right of the nature (RoE) to be protected against the adverse effects of anthropocene and uninterrupted condition to regenerate and recreate its lifecycles, structures, functions and evolutionary process. The RoE is a recent and radical recognition of environment/ nature as an independent legal personality capable of bearing certain immutable and inalienable rights in the eyes of law like a person.5 This right emanates certain responsibilities on the government and non-government agencies to respect protect and promote these rights of environment. The RoE emanates that the right-holder environment is entitled to compensatory restoration against damage, degradation and interferences caused by the human conduct and the duty-holder State is obliged to restore environmental damage caused by natural disasters like windstorm, flood, cyclone, draught, earthquake etc.6

These environmental rights have largely been made part of the paramount law of the nations through the process of environmental constitutionalism. In modern times, domestic environmental care has been elevated from ‘ordinary legal stage’ to ‘constitutional stage’ to make environmental governance more endurable and less susceptible to political airs.7 A comparative study reveals that the nations having guaranteed environmental rights in their constitutions frequently ratify international environmental treaties; highly fulfill environmental commitments and represent lesser per capita ecological footprints in comparison to the nations not having constitutionally guaranteed such rights.8 Environmental constitutionalism has emerged as a potent tool to achieve the elusive goals of a complete eco-sustainability at the municipal levels.9

The United Nations (UN)

10 has significantly contributed in the development of environmental constitutionalism through conferences and summits on various themes including human environment to sustainable development since 1972. The UN has successfully developed a global consensus on a model of limited and controlled right to development of human beings that allows least exploitation of natural resources without impairing its resilience capacity. The UN has developed environmental jurisprudence and ecological jurisprudence to recognize people’s rights to environment and autonomous rights of environment/ ecology/ nature respectively. People’s right to environment is fulcrum of environmental democracy whereas autonomous right of environment is fulcrum of ecological democracy.

11 The environmental rights, being anthropocentric, enable human beings to capitalize natural environment for fulfillment of their interest and indirectly demands reforms in existing democratic institutions to protect and promote natural environment.

12 By contrast, the ecological rights i.e. rights of natural environment are eco-centric that ensures and protects interests of non-humans i.e. natural environment as well as future generations in the democratic decision making process demanding more normative standards for protection of environment. It would address well-being of human and non-human entities.

13 Despite certain theoretical distinctions, there is a unity in environmental jurisprudence and ecological jurisprudence in terms of shared environmental outcomes from the democratic institutions.

14 Distinctions between environmental rights and ecological rights are tabulated in table-I (created by author).

|

Table-I: Distinctions between Environmental Jurisprudence and Ecological Jurisprudence (created by author) |

| |

Environmental Rights |

Ecological Rights |

| SER |

Yes |

No |

| PER |

Yes |

No |

| RoN/ RoE |

No |

Yes |

| Democratic Values |

Environmental democracy |

Ecological democracy |

| Nature |

Anthropocentric |

Eco-centric |

| Priority of interest |

Human and present generation |

Non-human and future generations |

There has been a traumatic shift in the approach of the UN after the UNCHE-1972. The UN has registered shift in its approach from ‘human environment’ (1972) to ‘sustainable development’ (1992) within a short span of two decades. This shift in approach of the UN has continued through the UNWSSD-2002, the UNCSD-2012, and the Stockholm+50 Conference in 2022. The focus of the UN shifted from ‘environment’ to ‘development’ that weakened global concern for the protection of environment through the transformative process of the EC. The depletion of global concern for environmental protection began with the Rio Declaration-1992 that turned the clock of environmental conservation back under Principle 2 completely abandoning commitment for a wholesome environment and preferred right to development over the environmental conservation.15 Further, the Rio+20 Summit- 2012 and Stockholm+50 Meet tilted the environment-development scale towards the side of economic development that turned the concept of EC brownish.16 This research paper investigates the question that whether the UN has contributed in the progression of the EC or it has put the EC in peril through the UNHE-1972, the UNCED-1992, UNWSSD-2002, the UNCSD-2012, and the Stockholm+50 Meet? This research paper is presented in four sections: section 1 is the introduction; section 2 is the conceptual outlines of the EC; section 3 is the main scope of this research paper that examines the role of the UN in the development of the EC; and section 4 is the conclusion.

2. The Conceptual Outlines of the EC

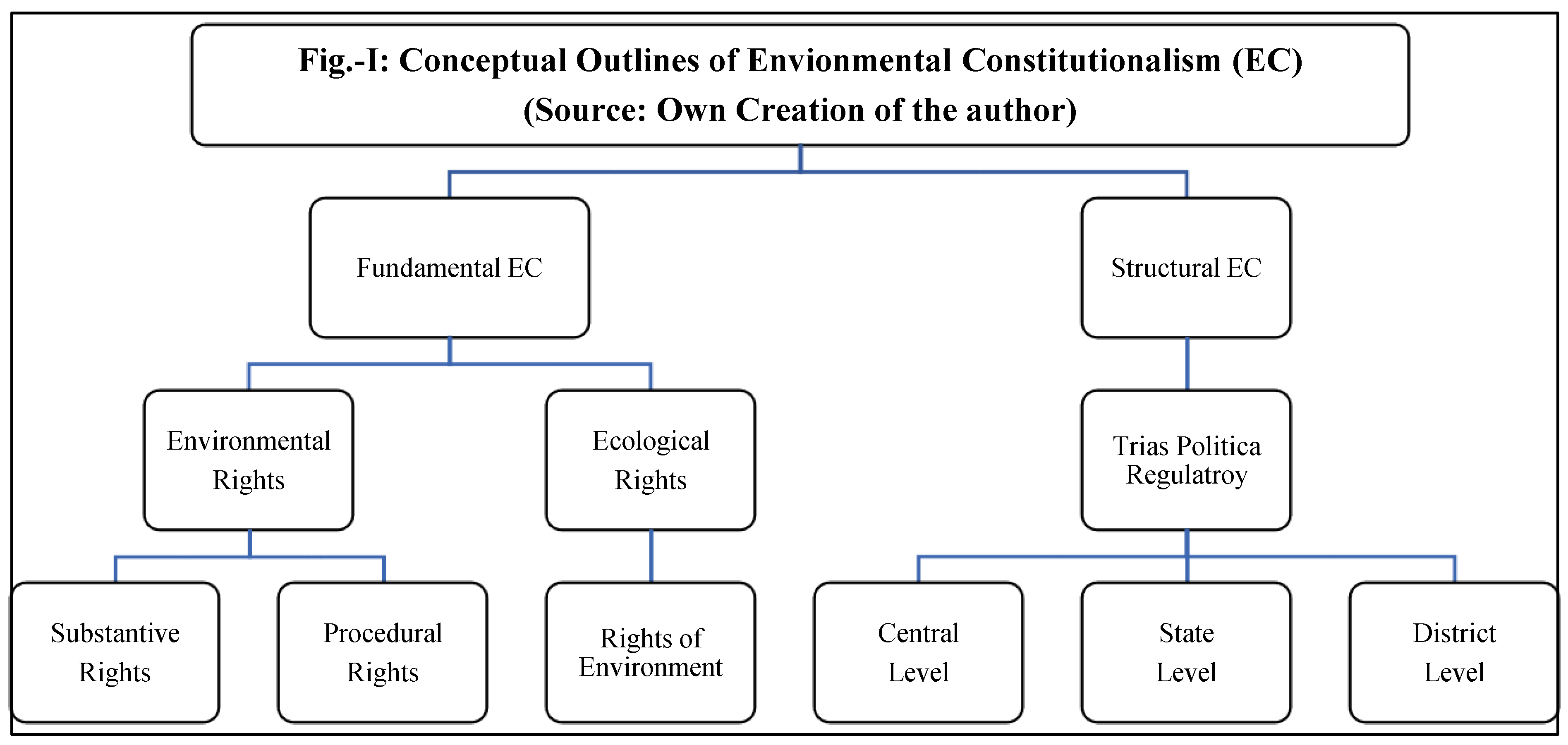

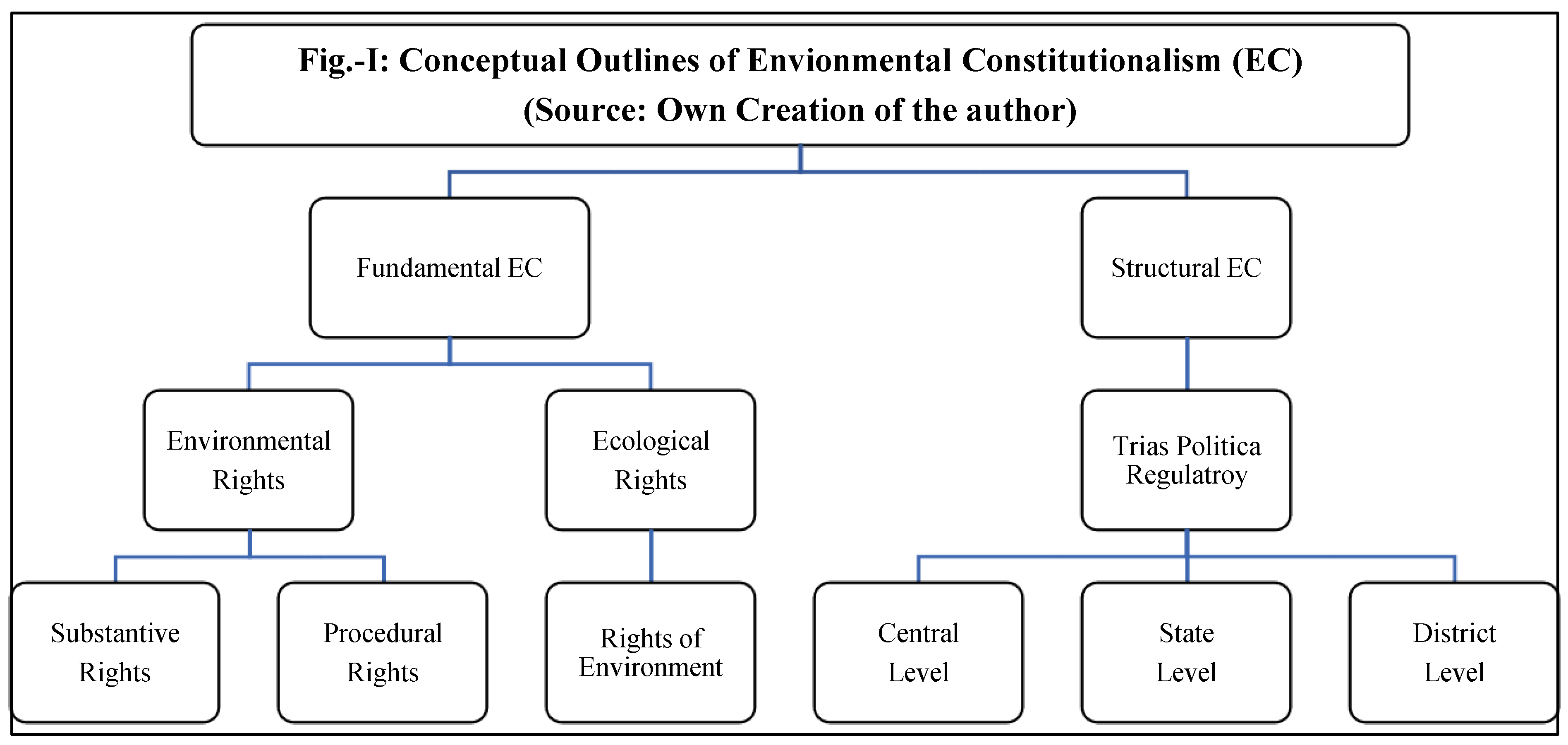

The phrase ‘environmental constitutionalism’ has acquired different meanings in different contexts.17 From the context of impact on the environmental quality and citizen’s environmental rights, the conceptual discourse of environmental constitutionalism is typically classified in two forms: fundamental environmental constitutionalism and structural environmental constitutionalism.18

2.1. Fundamental Environmental Constitutionalism

Fundamental environmental constitutionalism incorporates provisions for the SER, PER and RoE/N within the texts of national or sub-national constitutions.19 Such provisions create a new constitutional right and also codify common law principles pertaining to right to a healthy environment including right to clean and drinking water, right to fresh air, rights of wildlife and other natural resources. 20 Recent decision of Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in the Robinson Township v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania 21 is exposing tenets of fundamental environmental constitutionalism holding (per Castille, CJ) that

“The people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment. Pennsylvania’s public natural resources are the common property of all the people, including generations yet to come. As trustee of these resources, the Commonwealth shall conserve and maintain them for the benefit of all the people.”22

Fundamental environmental constitutionalism, from the perspectives of rights, encapsulates a set of future centric goal that is broad, ideal and aspirational in scope. For example, the Constitution of Republic of South Africa prescribes a justiciable environmental fundamental right: “Everyone has the right to an environment that is not harmful to their health or well-being; and to have the environment protected, for the benefit of present and future generations”23 and simultaneously declares objectives of the Local Government “to promote a safe and healthy environment.”24 Thus potential functions of these fundamental environmental constitutional rights are to mould and alter operational and functional rules of the government to conform environmental protection; prohibit functions of government that is hazardous to the environment; reaffirm existing and create new environmental rights; and present futuristic environment conservational goals. 25 Accordingly, Fundamental environmental constitutionalism is typically addressing to intra and intergenerational environmental relationship; citizen-government environmental relationship; citizen-citizen environmental relationship.26

The fundamental environmental constitutionalism is further grouped into three typical rights viz. substantive rights to environment, procedural rights to environment and basic rights of environment.

2.2. Substantive Environmental Rights (SER)

The substantive environmental rights (SER) are set of those basic and fundamental constitutionally entrenched rights that include rights of people to a clean, healthy, safe, sound, adequate and ecologically stable environment. The SER guarantees sustainable development to achieve good way of living.27 These basic and fundamental substantive environmental rights are supported by several other substantive rights such as right to environmental education, right to clean drinking water, right to health, and rights of nature.28 They provide ‘repose’ due to being self-executing and enforceable, less susceptible to political airs and more likely to endure because of resistance to constitutional reforms. They aim to afford the most durable and enforceable means for environmental protection.29

Handl (2020) challenges universal acceptance of substantive environmental rights as a free standing substantive right to a healthy, adequate and sustainable environment supporting his plea by referring absence of such environmental rights in the International Bill of Human Rights.30 But Rodríguez-Rivera (2020) contradicts Handl and supports free standing of substantive environmental rights in the global sphere referring to the Stockholm declaration on human environment.31

2.3. Procedural Environmental Rights (PER)

The procedural environmental rights are the constitutionally entrenched typical rights of stakeholders including right to information related to environmental impact of economic activities, right to contribute in the framing and execution of economic activities and right to access to the justice inter alia to bring legal action in courts for intrusion of SER through economic activities carried out by state or private actors. 32 It is a cornerstone of environmental governance and complements implementation of substantive environmental rights that presupposes creation of wide range of procedural environmental rights.33

2.4. Rights of Environment (RoE)

The third aspect of environmental constitutionalism is concerned with the rights of environment (RoE). It is most radical environmental rights that envisage a value in the environment beyond mere human benefits. 34 It recognizes environment, natural environmental entities and natural environmental processes a right-holder entity in the eyes of law like a person. 35 It projects environment as a living organism that is capable of holding basic rights and enjoy protections.36 This aspect of environmental constitutionalism considers that restricting justice and rights exclusively to the inter-human relations and depriving rest interested parties (such as nature) on the basis of morally irrelevant factors is arbitrary.37 Corrigan and Oksanen (2021) argue that environment or nature has entitlement of natural entity with right not to be damaged, degraded or interfered.38 This right of environment entails a duty on the government and non-government agents to protect and respect these rights of environment. Recognition of rights of environment in legal system makes the nature or environment a right-holder and State a duty-holder. The right-holder environment is entitled to compensatory restoration against damage, degradation and interferences caused by the human conduct and duty-holder State is obliged to restore environmental damage caused by natural disasters like windstorm, flood, cyclone, draught, earthquake etc.39 By and large, the span of the RoE is larger than the rights of mankind. A human is entitled to only right to compensation for infringement of his rights by any agency viz. natural person or legal person; whereas, the RoE enables the environment for two types of rights: first is the right to compensatory restoration, and second is the right to compulsory restoration. The environment’s right to compensatory restoration imposes duty on the agents to pay compensation for restoration of environment against the damages caused by their anthropogenic activities. The environment’s right to compulsory restoration is only against the State that makes the State duty bound to restore the environment against the damages caused by the natural actors like wind, storm, cyclone etc.

2.5. Structural Environmental Constitutionalism

Second typical form of environmental constitutionalism from the point of its impact on the quality of environment and on the environmental rights of people is the Structural environmental constitutionalism that is profoundly functional in federal system of government to allocate environmental regulatory authority across all levels of federal institutions within a particular nation.40 Hudson (2015) argues that structural environmental constitutionalism is as important for the environmental as fundamental environmental constitutionalism is. He says that though fundamental environmental constitutionalism enjoys highest pedestal of environmental constitutionalism since it creates and reaffirms justiciable fundamental environmental rights, but such rights would be meaningless unless there is certain regulatory scheme for the enforcement of those fundamental environmental rights. Structural environmental constitutionalism elaborately prescribes regulatory scheme allocating structural environmental governance rights to the regulatory authorities at all levels of the government.41

A federal constitution usually distributes regulatory authority over different subject matters, including environmental subjects, between dual political institutions viz. federal (national) government and provincial or state (sub-national) governments. This federal scheme of environmental government may create a number of hurdles in the environmental governance at each level of government, if the structural environmental governance design is minimal in jurisdiction.42 A provincial government may challenge federal efforts of environmental governance claiming the subject matter to be constitutionally reserved in its favour; and conversely, the federal government may preempt a provincial effort of environmental governance claiming the business coming within its exclusive constitutional scheme of powers. 43 Similar conflicting tale of environmental administration from federal constitution may reach to the provincial constitutions for creating tussle between the provincial government and the local bodies.44 Such structural regulatory divide may arise from expressed environmental constitutional texts or impliedly through judicial interpretation of constitution. Such structural regulatory divide does not only impede environmental governance but also impede creation of innovative environmental policies and enforcement of international environmental laws in the country.

A loosely structured environmental governance scheme has significant potential to invite regulatory deficit and collapse entire scheme of environmental constitutionalism. Therefore, it is advisable that the structural environmental constitutional scheme shall unfold optimal environmental governance jurisdictions to the governments of all level. 45 A strong structural environmental right makes fundamental environmental rights stronger.

3. Role of the UN in the development of the EC

This research paper investigates seeds of environmental constitutionalism within the conferences, summits and meetings of the United Nations including the United Nations Conference on Human Environment, 1972 (UNHCE, 1972), the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, 1992 (UNCED/ Rio Conference, 1992), the United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development, 2002 (UNWSSD/ Rio+10 / Rio 10 / Earth Summit/ Johannesburg Summit, 2002), the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, 2012(UNCSD/ Rio+20 / Rio 20) and United Nations Meeting on a healthy planet for the prosperity of all: Our responsibility, our opportunity, 2022 (Stockholm+50 Meeting). All of these conferences and summits contribute in the development of trio components of environmental constitutionalism viz. substantive environmental rights (SER), procedural environmental rights (PER) and rights of environment (RoE).

3.1. The UN and the SER

The Stockholm Declaration, 1972 has inspired the world consensus to recognize nexus between human rights and environment under its Principle 1 laying down that people have fundamental right to a dignified life in a quality environment and people are simultaneously responsible for protection and improvement of environment for him and for generations to come. 46 Although Stockholm Declaration, 1972 has brought the first global environmental phase; but it didn’t proclaim a substantive environmental right.47 Two decades later, the UN delivered Rio Declaration, 1992 and declared in Principle 1 that human are epicenter of sustainable development with a right to healthy and productive livings in harmony with nature. 48 Like Stockholm Declaration, Rio Declaration didn’t deliver a concrete and convincing substantive environmental rights provision rather both of them were limited to making a rhetorical claim for a substantive environmental right. 49 Both declarations are soft international environmental laws.

Aarhus convention (1998) more convincingly states about the SER under its article 1. It demands compliance of the Aarhus convention by the signatory States through guaranteeing protection of SER of the present and forthcoming generations including right to a dignified life in a quality environment and the SER should further be supported by guaranteeing PER to the people that includes right to access to environmental information, participate in environmental decision-making process and access to environmental justice.50 The Aarhus convention is labeled to have jurisdictional exposure limited to Europe only.

It is quite interesting to note that after the UNCHE and UNCED the term “environment” disappeared from the themes of forthcoming conferences of the United Nations such as UNWSSD-2002, UNCSD-2012, and Stockholm+50 conference in 2022.

The United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development, 2002 (UNWSSD/ Rio+10 / Rio 10 / Earth Summit/ Johannesburg Summit, 2002) submitted to us the Johannesburg Plan of Implementation (JPoI) that doesn’t exhibit the SER rather presents plan for the sustainable development that are supportive to the SER. The JPoI includes diversification of national energy sources giving preference to renewable energy sources, poverty eradication, transfer of eco-friendly technologies, development of integrated water resources management, and other climate change related issues that are necessary for economic and social development. 51 The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, 2012 (UNCSD/ Rio+20 / Rio 20) recognizes right to health as an indicator of socio-economic-environmental development52 and pledged strengthen worldwide health system.53 But it doesn’t enumerate the SER viz. rights of people to a clean, healthy, safe, sound, adequate and ecologically stable environment. The high level international meet on a “healthy planet for the prosperity of all: Our responsibility, our opportunity” (Stockholm+50 Meet) has recognized and pledged to implement people’s right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment to fulfill commitment made in principle 1 of the Stockholm Declaration-1972.54

The UN (2018) has recognized mutual dependence of human rights and environmental preservation without directly mentioning ‘environmental rights’ that is reproduced as under:

“A safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment is necessary for the full enjoyment of a vast range of human rights, including the rights to life, health, food, water and development. At the same time, the exercise of human rights, including the rights to information, participation and remedy, is vital to the protection of the environment.”55

The UNHRC (2021) has repetitively recognized contribution of sustainable development and environmental protection in restoration and campaigning of human rights by recognizing right to an adequate standard of living, food, safe drinking water, shelter, physical and mental well being in a fit and sustainable environment for present and forthcoming generation.56 Recently, the UNGA has recognized a SER to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment affirming that57

“the promotion of the human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment requires the full implementation of the multilateral environmental agreements under the principles of international environmental law.”

Accordingly, substantive environmental rights are set of fundamental rights of people that equip them with the basic rights related to fit and sustainable environment. It includes right to live in an environment adequate for health and well-being, safe drinking water, housing, sanitation etc. these rights are human centric and essential for the sustainable development. Environmental constitutionalism gives enforceable force to these substantive environmental rights within the domestic legal system.

There has been a remarkable shift in the approach of the UN in global recognition and protection of the SER from the Stockholm Declaration 1972 to the Stockholm+50 Meet. The SER has been taken up in the Stockholm Declaration 1972 and the Rio Declaration 1992 but dropped in the JPoI 2002 and the Rio+20; however the Stockholm+50 meet reconsidered the significance of the SER and pledged to implement the SER.

3.1. The UN and PER

Since the Rio Declaration, 1992, the PER have significantly added environmental rights to the domain of human rights.58 The Rio Declaration, 1992 specifically acknowledges civic-participation to efficiently handle environmental issues. It advocates for multiple of rights to ensure civic-participation such as access to environmental information kept by civil authorities, participatory rights in environmental decisions making process,59 and right to the environmental justice to protect present and forthcoming generation’s right to live in environment fit for health and welfare. It obliges State to spread civic awareness by publically notifying environmental information. Agenda 21 has projected the PER at international scale stating that “broad civic involvement in decision-making is one of the fundamental prerequisites for the achievement of SD.”60 The Aarhus Convention is a milestone and a seminal hard IEL that has operationalized objectives of Principle 10 of Rio Declaration in the Europe. Aarhus Convention provides under article 1 that the signatory States must guarantee to its citizen right to get environmental information, participatory rights in environmental decision making and access to environment justice to protect present and forthcoming generation’s right to live in environment fit for health and welfare. The Aarhus convention additionally makes numerous provisions such as article 4 provides right to access to environmental information held by public authorities, article 5 makes it mandatory for States to collect and disseminate environmental information, article 6 enables public to participate in decisions on specific activities, article 7 empowers people to participate in environmental plans, programmes and policies, and many others in the forgoing articles. 61 The Johannesburg Plan of Implementation (JPoI) submitted in the UNWSSD- 2002 recognizes the PER that recommends people’s right to access to public environmental information kept of public authorities and people’s right to participate at all levels of lucrative policies and decisions.62 The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, 2012 (UNCSD/ Rio+20 / Rio 20) promotes regional, national, sub-national and local actions to promote people’s right to access to environmental information and stakeholder’s participation in lucrative decision making process.63

The Stockholm+50 Meet recommends enabling all relevant stakeholders, including indigenous people, youth, rural communities and women, to participate effectively in the formulation and implementation of environmental policies at international and national levels64 and making easy access of youth-led organization to environmental funds.65

The procedural environmental rights have been broadly guaranteed in several national constitutions, and if not in national constitutions then, in domestic environmental legislations at least through the participatory rights in the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) procedure. There are persuasive reasons for proliferation of PERs within the texts of constitution or environmental laws across the world such as: quantitatively, countries have performed more robust environmental protection that has incorporated PERs in their environmental policies;66 it has transported EJ to the vulnerable communities providing them opportunities of meaningful participation in environmental decision making process; 67 and finally it has strengthened egalitarian ethics and exercises by providing access to environmental information and forum to influence policy decisions to the underrepresented groups.68

There is diversity of scholarly writings on the efficacy of procedural environmental rights in the realm of environmental governance. Some support the view that procedural environmental rights are self sufficient and a goal in itself to govern environmental matters and they don’t need edge of any of the substantial environmental rights. Eckersley (2004) claim that “the procedural environmental rights facilitate a robust “green public sphere” by providing fulsome environmental information and the mechanisms for contestation, participation, and access to environmental justice and that mechanisms are not only ends in themselves but also means to enhance the reflexive learning potential of both the state and civil society.”69 While, some researchers support the view that procedural environmental rights are not end in self rather they are means to achieve to ends of substantive environmental rights. Both approaches seem good, but by and large procedural environmental rights are supplementary to substantive environmental rights, if not subservient.

3.3. The UN and RoE

Granting legal rights to environment is recognition of intrinsic values of the environment and presents antidote to anthropocene caused by human-centric environmental rights.70 The rights of environment are purely eco-centric and give independent standing rights to environment to be represented by people individually or collectively.71

Recognition of the rights of environment has emanated public trust doctrine over the natural resources holding people of present generation trustee of these natural resources for the future generation and nature as well.72 Boyd (2017) three reasons for recognition of rights of nature to understand human-earth relationship: first, rights of nature is deriving from the eco-centric aspect that human is not master, moulder, owner of his life supporting ecosystem rather they are caretaker and trustee of ecosystem and responsible to make it intact for themselves as well as for forthcoming generations; second, rights of nature are a counterforce to treating nature as property of humans; and third, rights of nature reflects an evolving consciousness that endless lucrative escalation is not necessary for progress of human.73

The Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment-1972 (the Stockholm Declaration- 1972) has brought the idea of independent RoE before the world on 5th June 1972 proclaiming the protection and improvement of the human environment a goal to be achieved for present and future generation by conscious and collaborative actions.74 This proclaim of the Stockholm Declaration- 1972 crystallized in its principles putting solemn responsibility on the stakeholders to protect, safeguard and improve the environment and its components through due, careful, rational and collaborative policies, planning, and financial-technological assistance.75 The Stockholm Declaration- 1972 has imposed responsibilities on the States to prevent sea pollution,76 to do rational planning to reconcile conflict between development and environment,77 and not to cause trans-boundary environmental pollution. 78 The Stockholm Declaration- 1972 has inadvertently declared the RoE subservient to the sovereign exploitative rights of States79 that rendered the RoE redundant so far as RoE not to be damaged, degraded, or interfered with is concerned and arbitrarily restricted justice and rights exclusively to the human depriving the environment.

The Rio Declaration of the UNCED- 1992 has also acknowledged the RoE recognizing the integral and interdependent nature of earth80 and proclaiming environmental protection an integral component of the sustainable development.81 The Rio Declaration- 1992, further, declares negative rights of the environment putting responsibility on the States to widely apply the precautionary principle, 82 polluter pay principle 83 and undertake national environmental impact assessment process 84 to protect the environment from lucrative activities. The Rio Declaration- 1992 has inadvertently copied the subservient approach to RoE from the Stockholm Declaration- 1972 licensing the States to exploit natural resources within their control.85 Both the declarations had built an edifice of the RoE by one hand but dismantled that edifice by the other hand.

The United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development, 2002 (UNWSSD/ Rio+10 / Rio 10 / Earth Summit/ Johannesburg Summit, 2002) has not only segregated the ‘environment’ from its theme but also surrendered individualistic autonomy of the environment to hold the RoE declaring environmental protection as one of the pillars of the sustainable development mutually interdependent with other two pillars including economic and social development.86Similarly, the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, 2012 (UNCSD/ Rio+20 / Rio 20) followed the concept of sustainable development that again gave up individualistic autonomy of the environment to hold RoE putting forward multiple ambitions to achieve all dimensions of the sustainable development integrating and interlinking its economic, social and environmental aspects together.87

The United Nations convened a high level international meeting on a “healthy planet for the prosperity of all: Our responsibility, our opportunity” (Stockholm+50 Meet) on 2nd & 3rd June 2022 in Stockholm to commemorate successful 50 years of the UNCHE-1972 and global environmental actions.88 The Stockholm+50 registered ‘ecocide’ as an international crime 89 and triple common environmental crises for present and future generations including climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution.90 The Stockholm+50 recommended integration of ethical values to restore human-nature relationship, 91 adoption of redefined environmentally centered economic and fiscal policies, 92 alignment of public-private financial flows with environmental-climate-sustainable development commitments, 93 and strengthening of national environmental legislations and frameworks94 for a healthy planet. But, the Stockholm+50 meet does not make recommendation for an autonomous RoE independent of social and economic development.

4. Conclusions

Rights related to environment are generally described as a typical set of responses to the environmental problems caused by human-environment interaction.95 The list of the environmental rights is growing with the growing environmental problems due to interaction between human and environment. Over the years, all environmental rights have been categorized into three typical categories on the basis of different objectives and goals of these rights: substantive environmental rights, procedural environmental rights, and rights of environment (Figure-I). 96 The three overarching category of environmental rights are significantly contributing in the formulation of environmental constitutionalism at domestic levels. 97 Making these environmental rights a Grundnorm i.e. hierarchically supreme norm in a domestic legal system shall serve in the environmental conservation by reconciling human-environment conflict. These three overarching rights are again divided in two classes based on their performances in democratizing environmental governance: environmental rights and ecological rights. The environmental rights include people’s substantive and procedural rights to environment. They are fulcrum of environmental democracy. The ecological rights are distinct from environmental rights and recognize nature’s rights in pari passu with human beings.

The Stockholm Declaration 1972 has been a seminal international environmental document that has lightly picked up the trinity of environmental rights including the SER, the PER and the RoE for the first time at global forum. This momentum of recognition of the trinity of environmental kept on in the Rio Declaration 1992 as well. However, the SER and RoE do not find mention in the Johannesburg Declaration 2002. The Johannesburg Declaration 2002 mentions only the PER that too in a very limited manner by recognizing people’s right to access to public environmental information kept of public authorities and people’s right to participate at all levels of lucrative policies and decisions.98 The Rio+20 Declaration 2012 follows the Johannesburg Declaration 2022 and recognizes only the PER of the people to access to environmental information and stakeholder’s participation in lucrative decision making process to promote regional, national, sub-national and local environmental actions.99 The Stockholm+50 recognizes the SER and the PER but not to the RoE.

Although there has been several U-turns in the approach of the UN to uphold trinity of environmental rights including the SER, the PER and the RoE, the United Nations has successfully encouraged around three quarter nations across the world to take steps for environmental constitutionalism inserting the SER, the PER, and the RoE within their constitutional texts in a variety for forms. Resultantly, the SER, the PER, and the RoE have received constitutional safeguards and became less susceptible to ordinary political change. For example, the Ecuador has amended its constitution in 2008 and recognized “right of nature to integral respect for existence, maintenance and regeneration; empowered natural and juristic persons to approach public authorities to enforce rights of nature; and made provision to encourage natural and legal persons by State incentives to save nature and encourage reverence for its conservation.”100

The United Nations Commission for Europe has yielded the Aarhus Convention, 1998 to guarantee right to accessibility to environmental information, stakeholders involvement in environmental decision making and right to access to environmental justice to protect present and forthcoming generation’s right to live in environment fit for health and welfare. 101 The environmental constitutionalism has attained ‘universal’ acceptance in Eastern European constitutions. The European Environmental Human Rights strongly argues that an environmental fundamental right is a means to resolve conflicts and include environmental rights in the constitutional texts. It declares environmental rights in pari passu with other fundamental rights and freedoms with respect to degree of judicial protection. Central and Eastern European countries (from Albania to Ukraine) have adopted environmental constitutionalism in their constitutions as first order rights that is self executing rights. Western European countries (Belgium and France) have incorporated environmental right of first generation within their constitutional texts. Ukraine has constitutionalizd substantive environmental rights to a livable and wholesome environment to all and right to recompense for defiance of this right. It has recognized right of the persons to free accessibility to environmental rights possessed by any authority including right to propagate it.102

Environmental constitutionalism is significantly reflected in about three quarters of Sub-Saharan African constitutions. Environmental constitutionalism has least reach in North Africa, Middle East and Oceania. Most of the African countries (from Angola to Seychelles) have also endorsed environmental constitutionalism placing SER in their constitutions as first order of rights or first generation rights. The fundamental right to environment is present in the Angolan Constitution that is reproduced hereunder:103

“1. Everyone has the right to live in a wholesome and unpolluted environment and the obligation to defend and preserve it.

2. The state shall take the requisite measures to defend the environment and class of flora and fauna throughout national territory, maintain the ecological balance, ensure the correct location of economic activities and the rational development and use of all natural resources, within the context of sustainable development, value for the rights of forthcoming generations as well as preservation of species.

3. Activities that jeopardize or damage ecological conservation shall be punishable by law.”

The Asian countries have also performed in this area and brought environmental constitutionalism in parity with the United Nations environmental parameters. Nepal has recognized fundamental right to clean environment for all in following words:

“1. Each person shall have the right to live in a healthy and clean environment.

2. The victim of environmental pollution and degradation shall have the right to be compensated by the pollutant as provided for by law.

3. Provided that this Article shall not be deemed to obstruct the making of required legal provisions to strike a balance between environment and development for the use of national development works.”104

The Constitution of India doesn’t bear judicative environmental rights rather it makes environment one of the contra-judicative constitutional provisions laying obligation of the State and the citizen to protect and preserve the environment and its various components.105 However, the Indian Courts have repeatedly recognized the environmental rights within the judicative fundamental rights in a number of cases 106 and also expressed its view to establish regional environmental courts107 that came up with the establishment of the National Green Tribunal under the National Green Tribunal Act-2010.

References

- Lael K Weis, “Environmental constitutionalism: Aspiration or transformation?,” International Journal of Constitutional Law, vol. 16(3) (2018), pp. 836–70; at p. 837, https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/moy063; David Richard Boyd, “The environmental rights revolution: constitutions, human rights, and the environment” (University Of British Columbia, Columbia, 2010), at p. 87. [CrossRef]

- Lynda Collins, The Ecological Constitution: Reframing Environmental Law (Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, London New York, NY, 2021), pp. 36-39. ISBN. 978-1-032-05211-3.

- Sam Bookman, “Demystifying Environmental Constitutionalism,” Environmental Law Review, vol. 54(1) (2024), pp. 1–77, at 9-14.

- Ibid.

- Christopher D. Stone, “Should Trees Have Standing? Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects,” Southern California Law Review, Vol. 45 (1972), pp. 450–501. URL: https://iseethics.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/stone-christopher-d-should-trees-have-standing.pdf; Roderic O’Gorman, “Environmental Constitutionalism: A Comparative Study,” Transnational Environmental Law, vol. 6(3) (2017), pp. 435–462. Daniel P. Corrigan and Markku Oksanen, “Rights of Nature: Exploring the Territory,” in D. P. Corrigan, M. Oksanen (eds.), Rights of nature: a re-examination (Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, London; New York, 2021), pp. 1-13, ISBN: 978-0-367-47958-9. [CrossRef]

- Daniel P. Corrigan and Markku Oksanen, note 5.

- Louis J. Kotzé, “Arguing Global Environmental Constitutionalism,” Transnational Environmental Law, vol. 1(1), (2012), pp. 199–233. [CrossRef]

- David Richard Boyd, The Environmental Rights Revolution: A Global Study of Constitutions, Human Rights, and the Environment, (UBC Press, 2012), https://www.ubcpress.ca/the-environmental-rights-revolution.

- Ibid.

- The United Nations is a global centre for harmonizing actions of nations in the attainment of international peace and security. Article 1(4) of THE UNITED NATIONS CHARTER, 1945, available at: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter/full-text accessed on 10 January 2025.

- Robyn Eckersley, “Ecological Democracy and the Rise and Decline of Liberal Democracy: Looking Back, Looking Forward,” Environmental Politics, vol. 29 (2020), p. 214. [CrossRef]

- Manuel Arias-Maldonado, Real Green: Sustainability after the End of Nature, 1st Edition (Routledge, 2016). [CrossRef]

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Franz Xaver Perrez, “The Role of the United Nations Environment Assembly in Emerging Issues of International Environmental Law,” Sustainability, vol. 12 (2020), p. 5680; Pierre-Marie Dupuy and Jorge E. Viñuales, International Environmental Law, 2nd Edition (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2018), ISBN 978-1-108-42360-1. [CrossRef]

- Franz Xaver Perrez, note 15; Lakshman Guruswamy, “International Environmental Law: Boundaries, Landmarks, and Realities,” Natural Resources & Environment, vol. 10 (1995), p. 43-48, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40923450.

- Brian J. Gareau, “Foreword: Global Environmental Constitutionalism,” Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review, vol. 40(2) (2013), pp. 403-8, https://lira.bc.edu/work/sc/28c24d71-8d53-407e-a9bf-2e052a14ccb6/reader/1f130149-40e0-459e-a002-53ffaa567bf6.

- Blake Hudson, “Structural Environmental Constitutionalism,” Widener Law Review, vol. 21(2) (2015), pp. 201–16, https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/faculty_scholarship/170.

- Ibid.

- Michael C. Blumm and Mary Christina Wood, The Public Trust Doctrine in Environmental and Natural Resources Law, 3rd Edition (Carolina Academic Press, Durham, North Carolina, 2021), ISBN: 978-1-5310-2056-9.

- 83 A.3d 901 (2013), available at: https://delawarelaw.widener.edu/files/resources/robinsontwp2013editedmay1.pdf accessed on 10 January 2025.

- THE CONSTITUTION OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA, 1968, Article I, section 27 (also known as the ‘Environmental Rights Amendment’ Act, 1971), available at: https://www.paconstitution.org/texts-of-the-constitution/1968-2/#amendments accessed on 10 January 2025.

- THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA (1996). Article 24, Chapter 2. Bill of Rights, available at: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitutions?lang=en&key=env&status=in_force&status=is_draft accessed on 10 January 2025.

- Ibid. Article 152(1)(d), Chapter 7. Objects of local government, available at: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitutions?lang=en&key=env&status=in_force&status=is_draft accessed on 10 January 2025.

- Louis J. Kotzé, Global Environmental Constitutionalism in the Anthropocene (Hart Publishing, Portland (Or.), 2016), ISBN: 978-1-5099-0758-8.

- Ibid.

- Lynda Collins, note 2.

- Ibid; Norbert Brunner et al., “The Human Right to Water in Law and Implementation,” Laws, vol. 4(3) (2015), pp. 413–71, https://www.mdpi.com/2075-471X/4/3/413.

- Richard S. Kay, “American Constitutionalism,” in Larry Alexander (ed.), Constitutionalism: philosophical foundations, 1st Edition (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001), pp. 16–63, ISBN: 978-0-521-48293-6.

- Günther Handl, “The Human Right to a Clean Environment and Rights of Nature: Between Advocacy and Reality,” in A. Von Arnauld, K. Von Der Decken, et al. (eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of New Human Rights, 1st Edition., (Cambridge University Press, 2020), pp. 137–53. [CrossRef]

- Luis E. Rodríguez-Rivera, “The Right to Environment: A New, Internationally Recognised, Human Right,” in A. Von Arnauld, K. Von Der Decken, et al. (eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of New Human Rights, 1st Edition, (Cambridge University Press, 2020), pp. 154–62. [CrossRef]

- Lynda Collins, note 2.

- Robyn Eckersley, “Greening Liberal Democracy: The Rights Discourse Revisited,” in B. Doherty (ed.), Democracy and green political thought: sustainability, rights and citizenship, 1st Edition (Routledge, London, 1996), pp. 207–29, ISBN: 978-0-415-14412-4.

- Roderic O’Gorman, note 5, at p. 5.

- Daniel P. Corrigan & Markku Oksanen, note 5, at p. 1.

- Christopher D. Stone, note 5.

- James Nash, “The Case for Biotic Rights,” Yale Journal of International Law, vol. 18(1) (1993), pp. 235–49, http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.13051/6297.

- Daniel P. Corrigan & Markku Oksanen, note 5, at p. 9.

-

Ibid, at p. 10.

- Blake Hudson, note 18.; Louis J. Kotzé, note 25.

- Ibid.

- Blake Hudson and Jonathan Rosenbloom, “Uncommon Approaches to Commons Problems: Nested Governance Commons and Climate Change,” Hastings Law Journal, vol. 16(4) (2013), pp. 1272–342, https://repository.uclawsf.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol64/iss4/4/.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Stockholm Declaration-1972 adopted by the United Nations Conference on Human Environment on 16 June 1972, UN Doc. A/Conf.48/14/Rev. 1(1973); 11 ILM 1416.

- Louis J. Kotzé, “Human Rights, the Environment, and the Global South,” in S. Alam (ed.), International environmental law and the Global South (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2015), ISBN: 978-1-107-05569-8.

- The Rio Declaration, 1992 adopted by the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development on 14th June 1992, Rio de Janeiro, UN Doc. A/CONF.151/26/Rev. 1 (Vol. l).

- Karen Morrow, “Human rights and the environment: substantive rights,” in M. Fitzmaurice, M. Brus, et al. (eds.), Research Handbook on International Environmental Law (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2021). [CrossRef]

- The Aarhus Convention-1998 adopted by the UN Economic Commission for Europe. Available at: https://unece.org/DAM/env/pp/documents/cep43e.pdf accessed on 12 January 2025.

- The Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development-2002 adopted by the United Nations World Summit on Sustainable Development on 4th September 2002. UN Doc. No. A/CONF.199/20.

- The Rio+20 Declaration-2012 titled ‘THE FUTURE WE WANT’ adopted by the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development-2012 on 27th July 2012. UN Doc. No. A/RES/66/288, Paragraph 138.

- Ibid. paragraph 139.

- The Stockholm+50 Meet-2022 titled “A HEALTHY PLANET FOR THE PROSPERITY OF ALL- OUR RESPONSIBILITY, OUR OPPORTUNITY” adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 1st August 2022, UN Doc. A/CONF.238/9, Paragraph 157, recommendation 2.

- United Nations, Framework Principles on Human Rights and Environment (2018). Principle 2. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/FrameworkPrinciplesUserFriendlyVersion.pdf; https://rm.coe.int/manual-environment-3rd-edition/1680a56197 accessed on 12 January 2025.

- United Nations Human Rights Commission, A/HRC/RES/48/13, (2021). Available at: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g21/289/50/pdf/g2128950.pdf?token=RVz0Uy0T2TfAGy8bUB&fe=true accessed on 12 January 2025.

- United Nations General Assembly, The human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment (2022), Resolution A/RES/76/300. Available at: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n22/442/77/pdf/n2244277.pdf?token=Ln7BABUOP5tQnAgkDe&fe=true accessed on 12 January 2025.

- A. Boyle, “Human Rights and the Environment: Where Next?,” European Journal of International Law, vol. 23 (3) (2012), pp. 613–42. [CrossRef]

- The Rio Declaration, 1992, note 48, Principle 10.

- Agenda 21 adopted by the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development on 14th June 1992, Rio de Janeiro, UN Doc. A/CONF.151/26/Rev. 1 (Vol. l). Chapter 8.

- Supra note 50.

- The Johannesburg Declaration- 2002, note 51.

- The Rio+20 Declaration-2012, note 52, Paragraph 99.

- The Stockholm+50 Meet-2022, note 54, Paragraph 157.

- Ibid. recommendation 9.

- Ken Conca, An Unfinished Foundation: The United Nations and Global Environmental Governance (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2015), ISBN: 978-0-19-023285-6.

- Scott Kuhn, “Expanding Public Participation is Essential to Environmental Justice and the Democratic Decisionmaking Process,” Ecology Law Quarterly, vol. 25(4) (1999), pp. 647–58, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24113385.

- Erin Daly, “Constitutional Protection for Environmental Rights: The Benefits of Environmental Process,” International Journal of Peace Studies, vol. 17(2) (2012), pp. 71–80, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41853036.

- Robyn Eckersley, The Green State: Rethinking Democracy and Sovereignty (MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass, 2004), ISBN: 978-0-262-05074-6.

- Geoffrey Garver, “A Systems-based Tool for Transitioning to Law for a Mutually Enhancing Human-Earth Relationship,” Ecological Economics, vol. 157 (2019), pp. 165–74. [CrossRef]

- Jérémie Gilbert et al., “The Rights of Nature as a Legal Response to the Global Environmental Crisis? A Critical Review of International Law’s ‘Greening’ Agenda,” in D. Dam-de Jong, F. Amtenbrink (eds.), Netherlands Yearbook of International Law 2021 (T.M.C. Asser Press, The Hague, 2023), pp. 47–74. [CrossRef]

- Quinn Yeargain, “Decarbonizing Constitutions,” Yale Law & Policy Review, vol. 41(2) (2023), pp. 1–74, https://yalelawandpolicy.org/sites/default/files/YLPR/1._yeargain_decarbonizing_constitutions_.pdf.

- David R. Boyd, The Rights of Nature: A Legal Revolution That Could Save the World (ECW Press, Toronto, ON, 2017), ISBN: 978-1-77041-239-2.

- The Stockholm Declaration-1972, note 46, Proclamation No. 7.

- Ibid, Principles 1, 2, 4, 10,11, 12 and 13.

- Ibid, Principle 7.

- Ibid, Principles 14, 15, 16 and 17.

- Ibid, Principle 21.

- Ibid, Principle 21.

- The Rio Declaration- 1992, note 48, Preamble.

- Ibid, Principle 4.

- Ibid, Principle 15.

- Ibid, Principle 16.

- Ibid, Principle 17.

- Ibid, Principle 2.

- The Johannesburg Declaration-2002, note 51.

- The Rio+20 Declaration-2012, note 52.

- The Stockholm+50 Meet, note 54.

- Ibid, paragraph 45.

- Ibid, paragraph 157.

- Ibid, recommendation 1.

- Ibid, recommendation 3.

- Ibid, recommendation 5.

- Ibid, recommendation 4.

- Tim Hayward, “Constitutional Environmental Rights: A Case for Political Analysis,” Political Studies, vol. 48(3) (2000), pp. 558–72. [CrossRef]

- Luis E. Rodriguez-Rivera, “Is the Human Right to Environment Recognized under International Law? It Depends on the Source,” Colorado J. of Int. Environ. Law & Policy, vol. 12(1) (2001), pp. 1–45.

- Roderic O’Gorman, note 5.

- The Johannesburg Declaration-2002, note 51.

- The Rio+20 Declaration-2012, note 52, Paragraph 99.

- THE CONSTITUTION OF THE REPUBLIC OF ECUADOR, Article 71. Available at: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Ecuador_2021.pdf accessed on 12 January 2025.

- Supra note 50.

- THE CONSTITUTION OF UKRAINE, 1996, Article 50. Available at: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Ukraine_2019.pdf accessed on 12 January 2025.

- Available at: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Angola_2010.pdf accessed on 12 January 2025.

- THE CONSTITUTION OF NEPAL, 2015, Article 30.

- THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA, 1950, Article 48A and 51(A)(g).

- Subhash Kumar v. State of Bihar, (1991) 1 SCC 598; Noise Pollution (V), In re,(2005) 5 SCC 733.

- P.N. Bhagwati, CJI. in M.C. Mehta v. Union of India (Oleum Gas Leakage case), 1986 SCR (1) 312; (1986) 2 SCC 176.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).