Submitted:

03 April 2025

Posted:

04 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

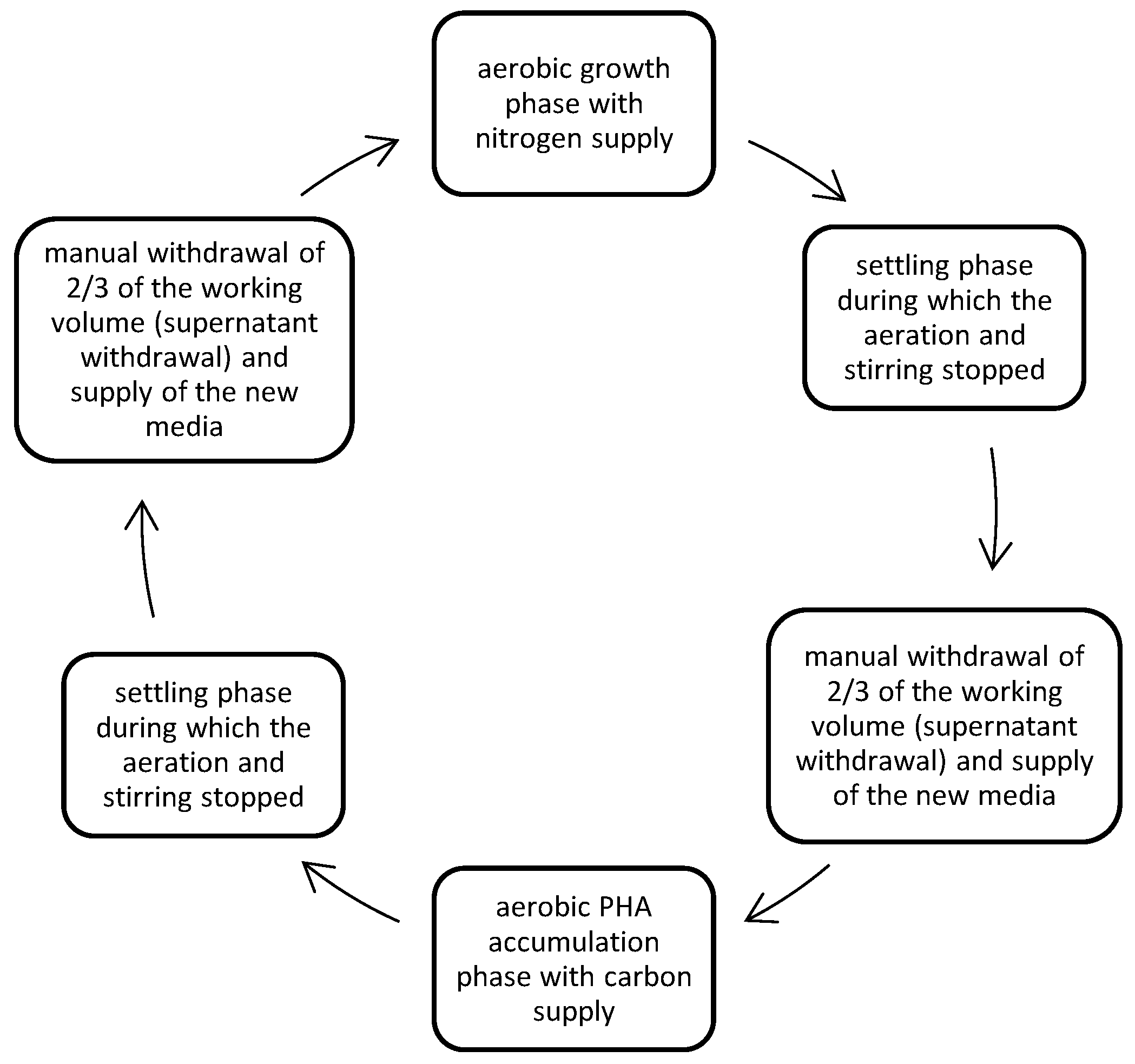

2.1. Setup and Operation of Bioreactors

2.2. Microbial Culture

2.3. Feedstock

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.5. Profiling of the structure of microbial populations

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

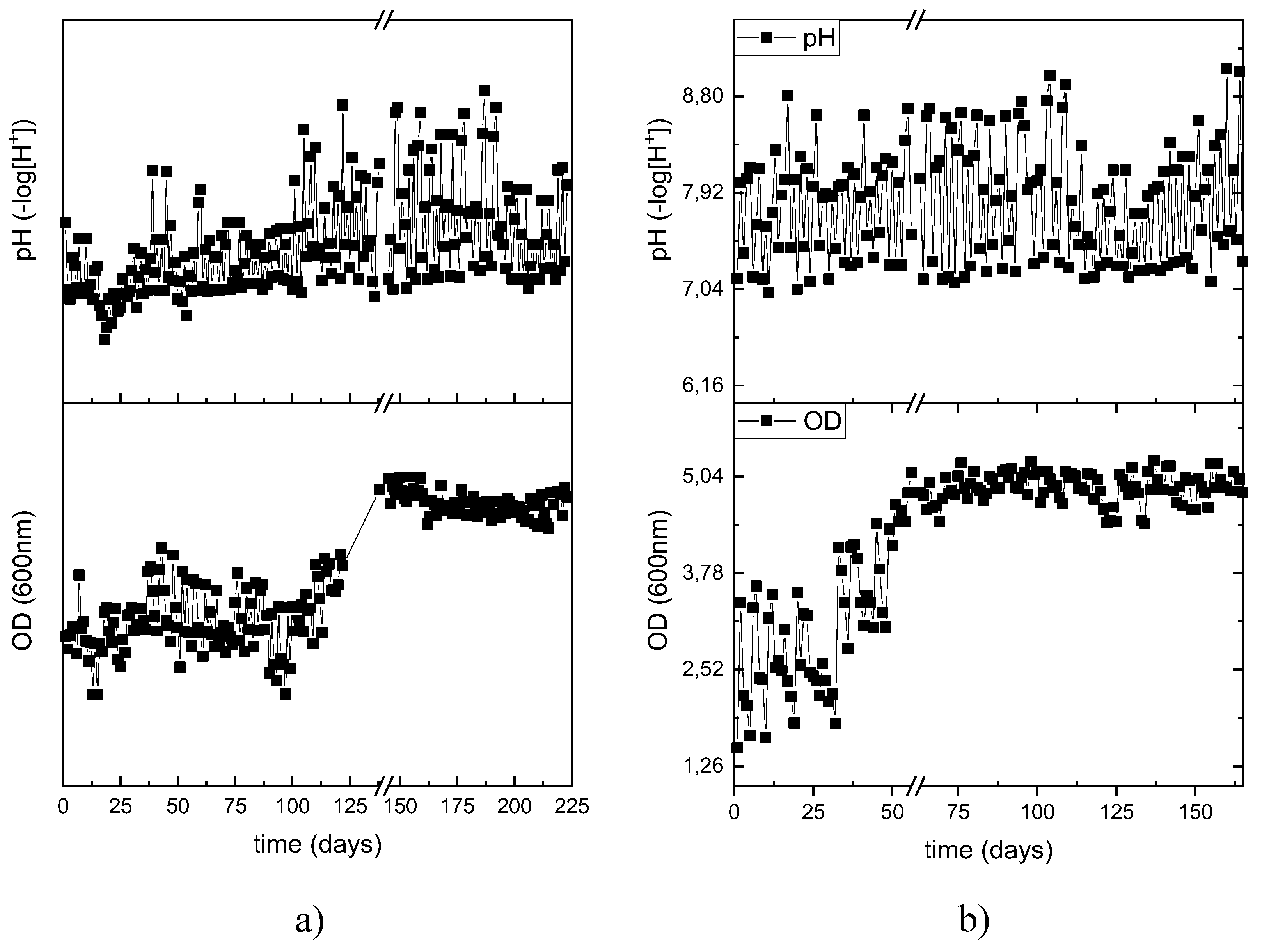

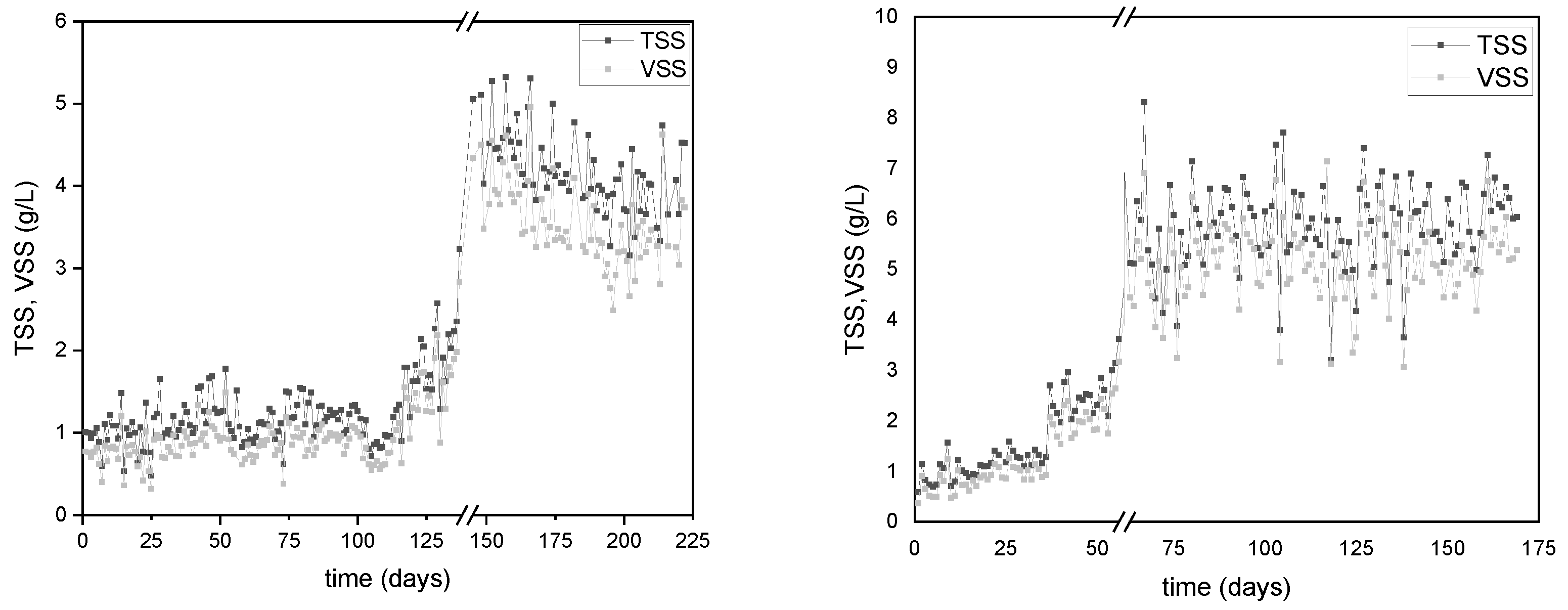

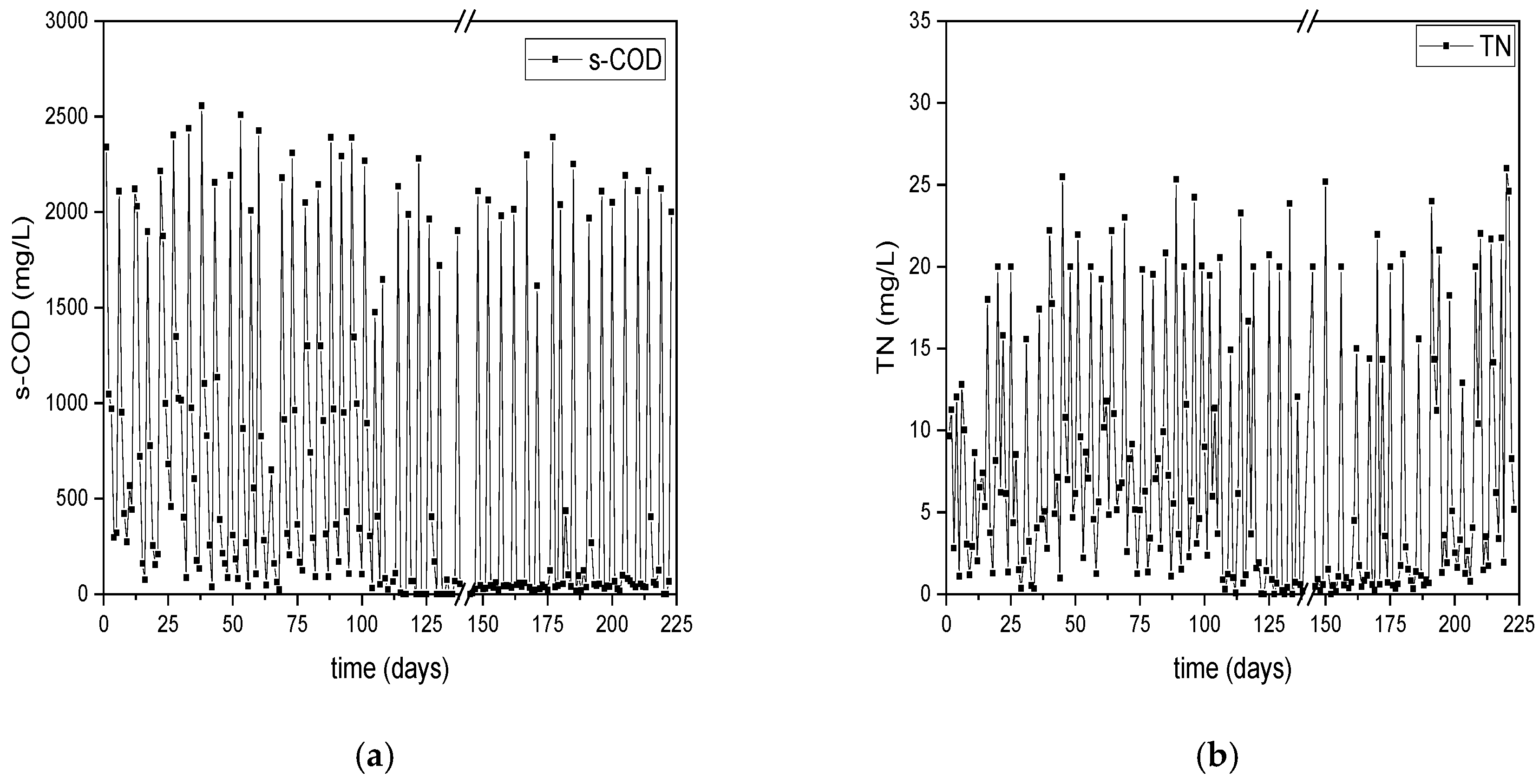

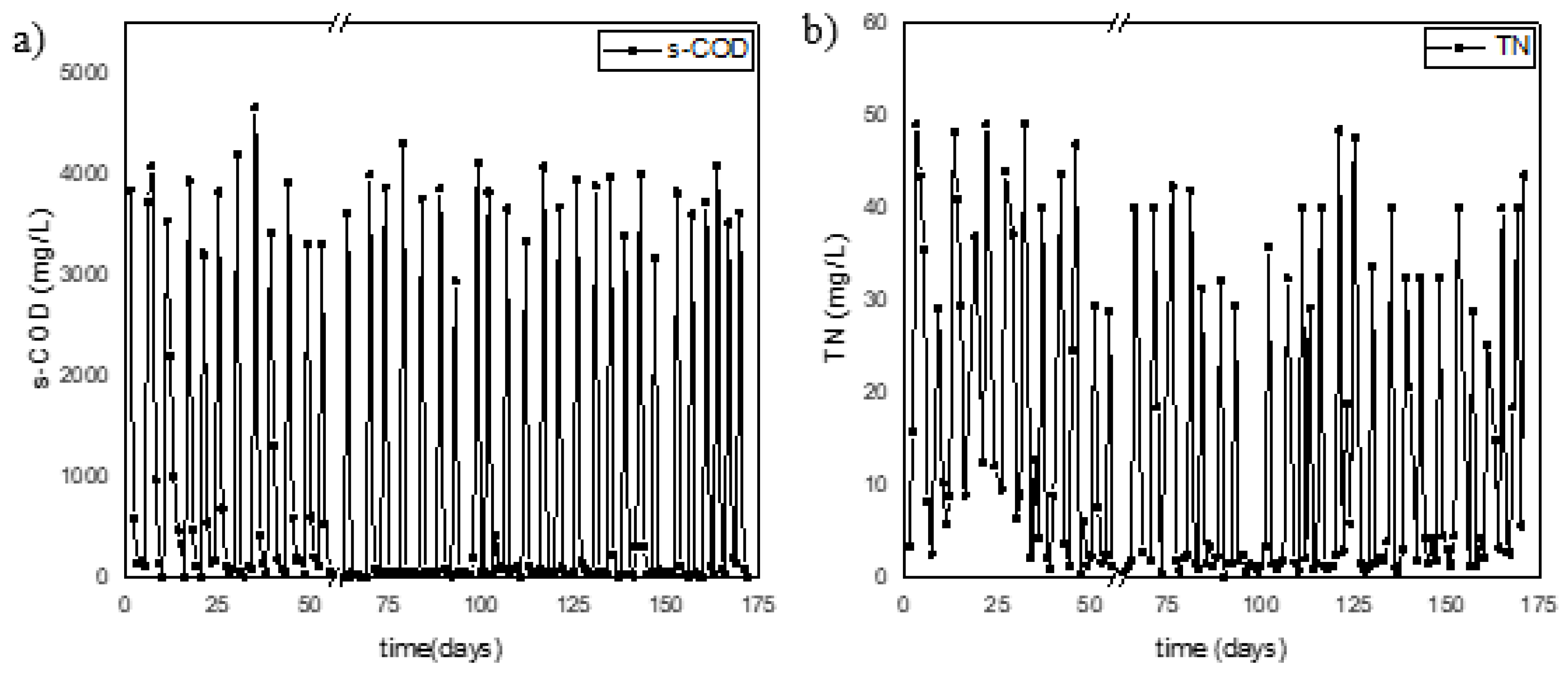

3.1. Comparison of operational efficiency of the reactors

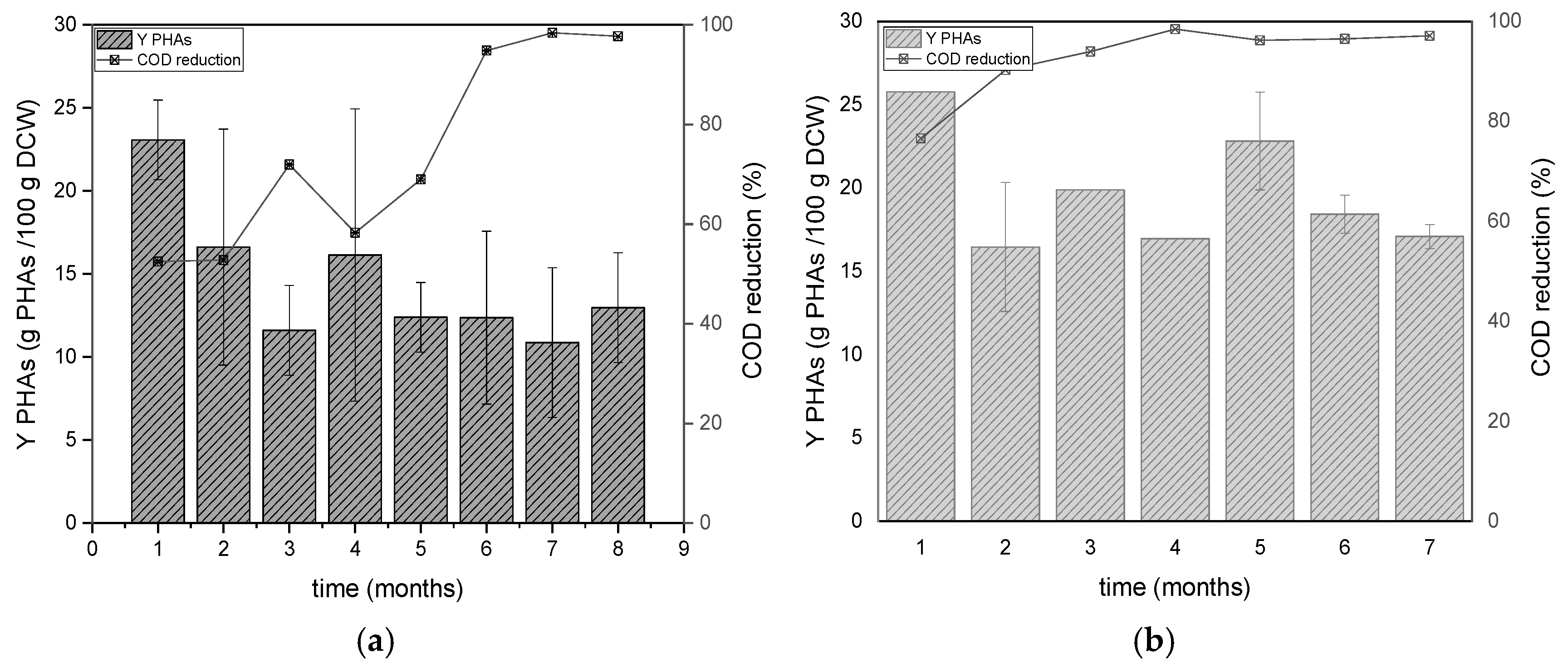

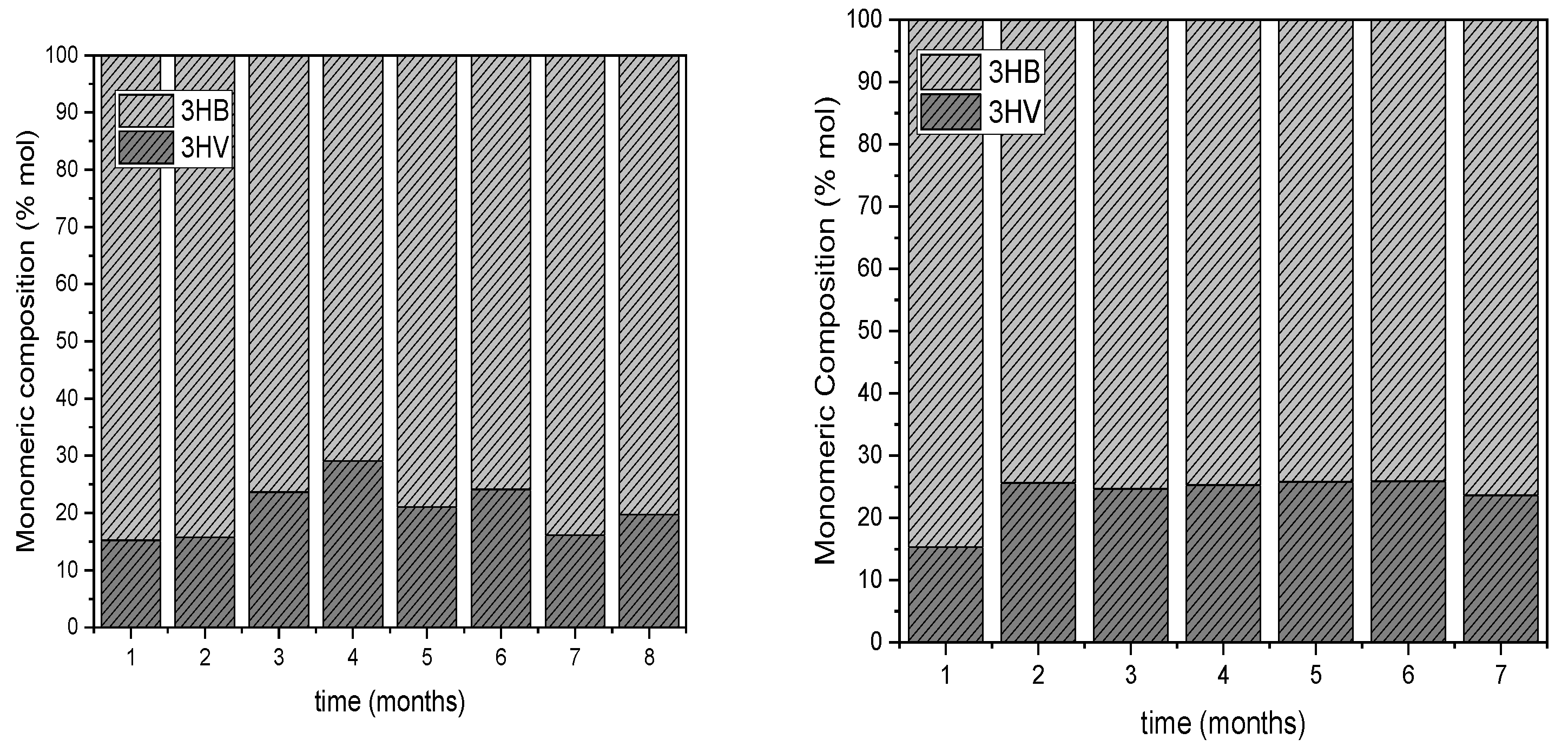

3.2. Comparison of PHAs yields and composition

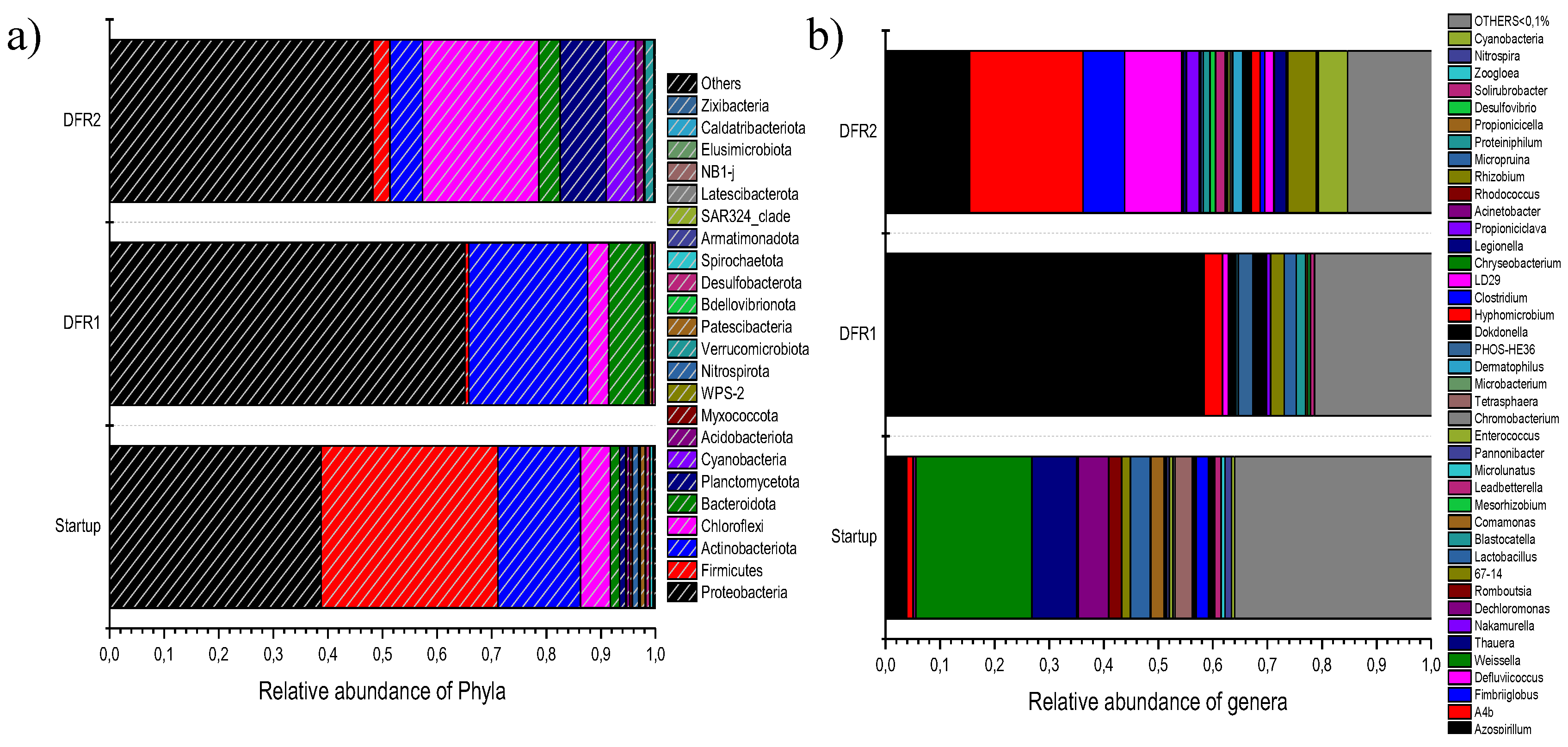

3.3. Development of the mixed microbial culture and evaluation of its structure

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PHA | Polyhydroxyalkanoates |

| scl-PHAs | short-chain-length Polyhydroxyalkanoates |

| mcl-PHAs | Medium-chain-length Polyhydroxyalkanoates |

| HFW | Household Fermentable Waste |

| FORBI | Food Residue Biomass |

| VFAs | Volatile Fatty Acids |

| MMC | Mixed Microbial Culture |

| DFR | Draw-Fill Reactor |

| sCOD | Soluble Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solids |

| VSS | Volatile Suspended Solids |

| HPLC | High Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| GC-FID | Gas Chromatography with flame ionization detection |

| PHBV | poly (3-R-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-R-hydroxyvalerate) |

| 3HV | 3-R-hydroxyvalerate |

| 3HB | 3-R-hydroxybutyrate |

| OL | Organic Load |

| OD | Optical Density |

| ADF | Aerobic Dynamic Feeding |

| ADD | Aerobic Dynamic Discharge |

| GAO | Glycogen-accumulating Organisms |

References

- Geyer, R. A Brief History of Plastics; 2020; pp. 31–47. [CrossRef]

- A Review on Microplastics – An Indelible Ubiquitous Pollutant. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2023, 13. [CrossRef]

- Chae, Y.; An, Y.-J. Current research trends on plastic pollution and ecological impacts on the soil ecosystem: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 240, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Advances and Challenges in Biopolymer-Based Films. Polymers 2022, 14, 3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafim, L.S.; Lemos, P.C.; Albuquerque, M.G.E.; Reis, M.A.M. Strategies for PHA production by mixed cultures and renewable waste materials. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 81, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourmentza, C.; Plácido, J.; Venetsaneas, N.; Burniol-Figols, A.; Varrone, C.; Gavala, H.N.; Reis, M.A.M. Recent Advances and Challenges towards Sustainable Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Production. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kora, E.; Tsaousis, P.C.; Andrikopoulos, K.S.; Chasapis, C.T.; Voyiatzis, G.A.; Ntaikou, I.; Lyberatos, G. Production efficiency and properties of poly(3hydroxybutyrate-co-3hydroxyvalerate) generated via a robust bacterial consortium dominated by Zoogloea sp. using acidified discarded fruit juices as carbon source. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 226, 1500–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Adama, N.; Adjallé, K.; Blais, J.-F. Sustainable applications of polyhydroxyalkanoates in various fields: A critical review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 221, 1184–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.-Q.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wu, F.-Q.; Chen, J.-C. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) toward cost competitiveness and functionality. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2020, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. English and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, The state of food and agriculture. 2019, Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction.

- Ioannidou, S.M.; Pateraki, C.; Ladakis, D.; Papapostolou, H.; Tsakona, M.; Vlysidis, A.; Kookos, I.K.; Koutinas, A. Sustainable production of bio-based chemicals and polymers via integrated biomass refining and bioprocessing in a circular bioeconomy context. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 307, 123093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytras, G.; Koutroumanou, E.; Lyberatos, G. Anaerobic co-digestion of condensate produced from drying of Household Food Waste and Waste Activated Sludge. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremouli, A.; Karydogiannis, I.; Pandis, P.K.; Papadopoulou, K.; Argirusis, C.; Stathopoulos, V.N.; Lyberatos, G. Bioelectricity production from fermentable household waste extract using a single chamber microbial fuel cell. Energy Procedia 2019, 161, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalopoulos, I.; Lytras, G.M.; Mathioudakis, D.; Lytras, C.; Goumenos, A.; Zacharopoulos, I.; Papadopoulou, K.; Lyberatos, G. Hydrogen and Methane Production from Food Residue Biomass Product (FORBI). Waste Biomass- Valorization 2020, 11, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellos, G.; Tremouli, A.; Kondylis, A.; Stamelou, A.; Lyberatos, G. Anaerobic Co-digestion of the Liquid Fraction of Food Waste with Waste Activated Sludge. Waste Biomass- Valorization 2024, 15, 3339–3350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamperidis, T.; Pandis, P.K.; Argirusis, C.; Lyberatos, G.; Tremouli, A. Effect of Food Waste Condensate Concentration on the Performance of Microbial Fuel Cells with Different Cathode Assemblies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, B. Rodger, Eaton D. Andrew, and Rice W. Eugene, Eds., Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Waste Water, 23rd ed. American Public Health Association, American Water Works Association, Water Environment Federation, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kiskira, K.; Lymperopoulou, T.; Lourentzatos, I.; Tsakanika, L.-A.; Pavlopoulos, C.; Papadopoulou, K.; Ochsenkühn, K.-M.; Tsopelas, F.; Chatzitheodoridis, E.; Lyberatos, G.; et al. Bioleaching of Scandium from Bauxite Residue using Fungus Aspergillus Niger. Waste Biomass- Valorization 2023, 14, 3377–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehmen, A.; Keller-Lehmann, B.; Zeng, R.J.; Yuan, Z.; Keller, J. Optimisation of poly-β-hydroxyalkanoate analysis using gas chromatography for enhanced biological phosphorus removal systems. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1070, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dionisi, D.; Majone, M.; Vallini, G.; Di Gregorio, S.; Beccari, M. Effect of the applied organic load rate on biodegradable polymer production by mixed microbial cultures in a sequencing batch reactor. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2006, 93, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khateeb, M.; Hassan, G.K.; El-Liethy, M.A.; El-Khatib, K.M.; Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Hu, A.; Gad, M. Sustainable municipal wastewater treatment using an innovative integrated compact unit: microbial communities, parasite removal, and techno-economic analysis. Ann. Microbiol. 2023, 73, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, D.; Fukuyama, A.; Ren, Y.; Ike, M. Rapid enrichment of polyhydroxyalkanoate-accumulating bacteria by the aerobic dynamic discharge process: Enrichment effectiveness, polyhydroxyalkanoate accumulation ability, and bacterial community characteristics in comparison with the aerobic dynamic feeding process. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerbergen, K.; Van Geel, M.; Waud, M.; Willems, K.A.; Dewil, R.; Van Impe, J.; Appels, L.; Lievens, B. Assessing the composition of microbial communities in textile wastewater treatment plants in comparison with municipal wastewater treatment plants. Microbiologyopen 2017, 6, e00413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freches, A.; Fradinho, J.C. The biotechnological potential of the Chloroflexota phylum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2024, 90, e0175623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troschl, C.; Meixner, K.; Drosg, B. Cyanobacterial PHA Production—Review of Recent Advances and a Summary of Three Years’ Working Experience Running a Pilot Plant. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angra, V.; Sehgal, R.; Gupta, R. Trends in PHA Production by Microbially Diverse and Functionally Distinct Communities. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 85, 572–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradíssimo, D.G.; Xavier, L.P.; Santos, A.V. Cyanobacterial Polyhydroxyalkanoates: A Sustainable Alternative in Circular Economy. Molecules 2020, 25, 4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheik, A.R.; Muller, E.E.L.; Wilmes, P. A hundred years of activated sludge: time for a rethink. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.d.L.Á.M.; Urzúa, L.S.; Carrillo, Y.A.; Ramírez, M.B.; Morales, L.J.M. Polyhydroxybutyrate Metabolism in Azospirillum brasilense and Its Applications, a Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itzigsohn, R.; Yarden, O.; Okon, Y. Polyhydroxyalkanoate analysis inAzospirillum brasilense. Can. J. Microbiol. 1995, 41, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Martínez, M.d.L.A.; González-Pedrajo, B.; Dreyfus, G.; Soto-Urzúa, L.; Martínez-Morales, L.J. Phasin PhaP1 is involved in polyhydroxybutyrate granules morphology and in controlling early biopolymer accumulation in Azospirillum brasilense Sp7. AMB Express 2019, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Galeote, D.; Argiz, L.; del Rio, A.V.; Mosquera-Corral, A.; Juarez-Jimenez, B.; Gonzalez-Lopez, J.; Rodelas, B. Dynamics of PHA-Accumulating Bacterial Communities Fed with Lipid-Rich Liquid Effluents from Fish-Canning Industries. Polymers 2022, 14, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Gautam, A.; Pawaday, J.; Kanzariya, R.K.; Yao, Z. Current Status and Challenges in the Commercial Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoate-Based Bioplastic: A Review. Processes 2024, 12, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokholm-Bjerregaard, M.; McIlroy, S.J.; Nierychlo, M.; Karst, S.M.; Albertsen, M.; Nielsen, P.H. A Critical Assessment of the Microorganisms Proposed to be Important to Enhanced Biological Phosphorus Removal in Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment Systems. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muigano, M.N.; Anami, S.E.; Onguso, J.M.; Omare, G.M. The Isolation, Screening, and Characterization of Polyhydroxyalkanoate-Producing Bacteria from Hypersaline Lakes in Kenya. Bacteria 2023, 2, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, S.; Werker, A.; Welander, T. Production of polyhydroxyalkanoates by glycogen accumulating organisms treating a paper mill wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 2008, 58, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, D.; Rossetti, S.; Serafim, L.S. PHA production by mixed cultures: A way to valorize wastes from pulp industry. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 157, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. Kivanc, M. M. Kivanc, M. Kıvanc, and N. Dombaycı, ‘PRODUCTION OF POLY-beta-HYDROXYBUTYRIC ACID BY RHIZOBIUM SP. PRODUCTION OF POLY-β-HYDROXYBUTYRIC ACID BY RHIZOBIUM SP’. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309315105. 3093. [Google Scholar]

- Tombolini, R.; Nuti, M. Poly(β-hydroxyalkanoate) biosynthesis and accumulation by differentRhizobiumspecies. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1989, 60, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bioreactor | C / N | OL (g COD/L) | Days of Operation |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFR-1 | 100 | 2 ± 0,5 | 223 |

| DFR-2 | 100 | 3.8 ± 0,6 | 172 |

| DFR-1 | DFR-2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TSS (g/L) | 2.42 ± 1.44 | 4.34 ± 2.12 | 0.0000 |

| VSS (g/L) | 2.12 ± 1.46 | 3.84 ± 1.93 | |

| % PHAs | 15.19 ± 6.00 | 19.05 ± 7.18 | 0.0653 |

| % HB | 81.41 ± 6.21 | 73.79 ± 3.80 | 0.0236 |

| % HV | 18.59 ± 6.21 | 26.21 ± 3.80 | 0.0317 |

| Start-up | DFR-1 | DFR-2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weissella (F) | 21,30% | Azospirillum (P) | 58,40% | A-4b (C) | 20,79% |

| Thauera (P) | 8,25% | Dokdonella (P) | 2,06% | Azospirillum (P) | 15,43% |

| Dechloromonas (P) | 5,52% | Microbulbifer (P) | 3,33% | Defluviicoccus (P) | 10,45% |

| Lactobacillus (F) | 3,56% | PHOS-HE36 (B) | 2,72% | Fimbriiglobus (PL) | 7,59% |

| Tetrasphaera (A) | 3,14% | Rhizobium (P) | 2,50% | Rhizobium (P) | 5,18% |

| Comamonas (P) | 2,39% | Micropruina (A) | 2,18% | Nakamurella (A) | 2,31% |

| Romboutsia (F) | 2,39% | Proteiniphilum (B) | 1,74% | Legionella (P) | 2,19% |

| Clostridium (F) | 2,33% | Defluviicoccus (P) | 1,08% | Dermatophilus (A) | 1,82% |

| 67-14 genera (A) | 1,62% | Propioniciclava (A) | 0,75% | Leadbetterella (B) | 1,78% |

| Nitrospira (N) | 1,18% | Solirubrobacter (A) | 0,72% | Dokdonella (P) | 1,52% |

| Sum top-10 | 51,69% | 75,49% | 67,55% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).