1. Introduction

Almost all indices related to anthropogenic environmental change and natural resource consumption began accelerating in the 1950s [

1,

2]. This trend was also evident in the increasing nutrient loads in the Baltic Sea. In Finland, for instance, the volume of water pumped into the sewage system in 1969 was 3.7 times higher than in 1950 [

1]. The rise in nutrient discharge was likely even greater, as phosphate-containing detergents became widely used during the same period. At the time, most municipal and industrial wastewater from Baltic Sea countries was discharged into waterways either with minimal filtration or entirely untreated. This era also marked a shift in agricultural practices, with farms increasingly replacing manure with synthetic fertilizers [

1]. It has been estimated that the nutrient load entering the Baltic Sea increased up to eightfold during the 20th century, with the majority of this growth occurring between 1950 and 1980 [

3].

Various statistics suggest that eutrophication related to sewage pollution began around 1955 in the central Baltic Sea [

4]. The Eutrophication Ratio (ER) [

5] indicates that eutrophication emerged in the mid-1950s, peaked in the 1980s, and subsequently improved significantly. Andersen et al. [

5] documented these improvements, which are a direct result of long-term efforts to reduce nutrient inputs.

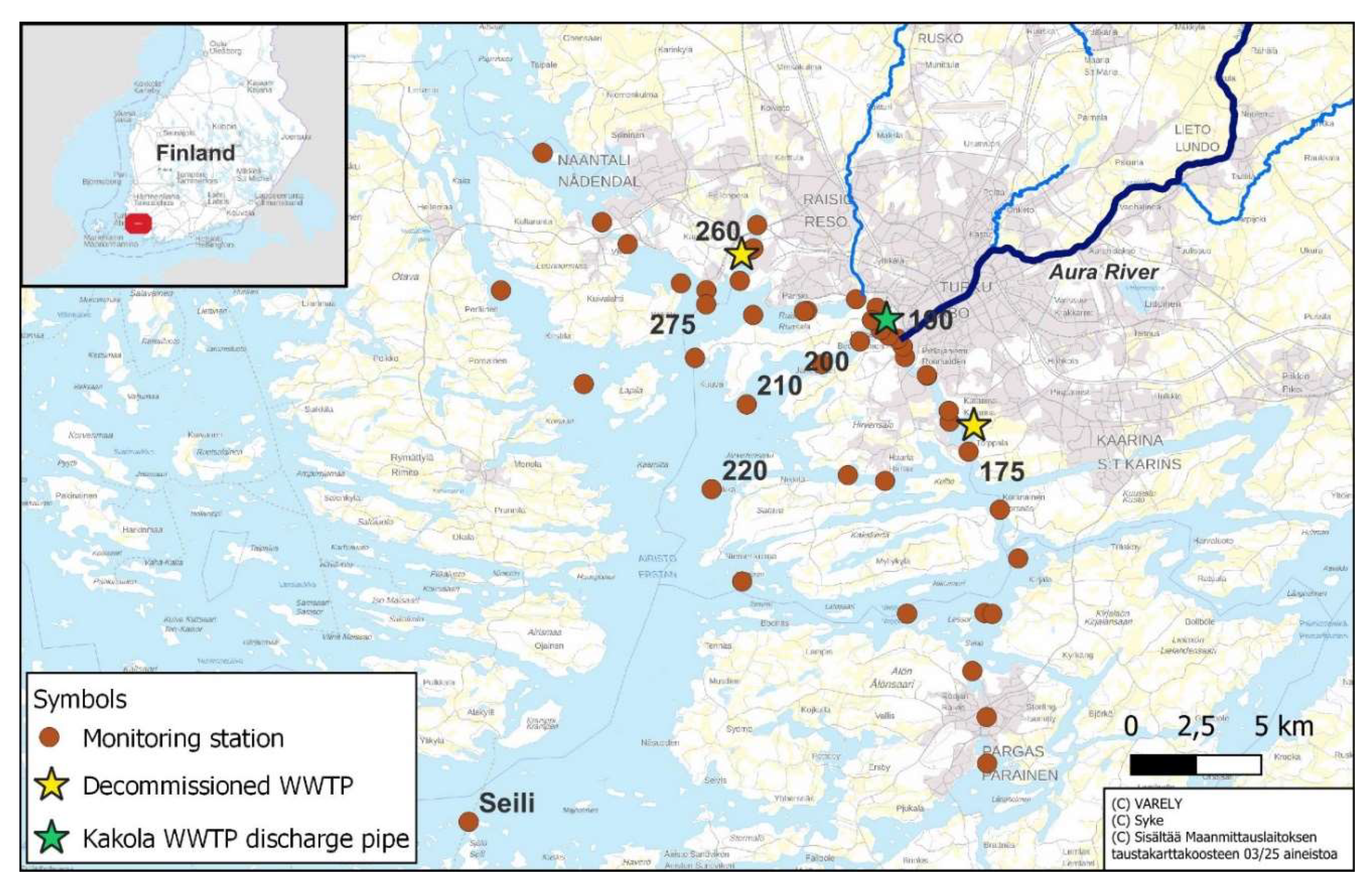

In Finland, wastewater treatment only began after the Water Act came into effect in 1962. The law prohibited activities that polluted water bodies and required polluters to apply for permits to discharge wastewater. However, the processing of wastewater permits was slow, and obtaining decisions took a long time. The largest wastewater polluter in the Archipelago Sea was the city of Turku. Turku’s first wastewater treatment plant was completed relatively late, only at the end of the 1960s. Until then, the city’s wastewater was discharged into the Aura River, which became increasingly polluted year by year. Over time, the lower reaches of the river began to resemble an open sewer.

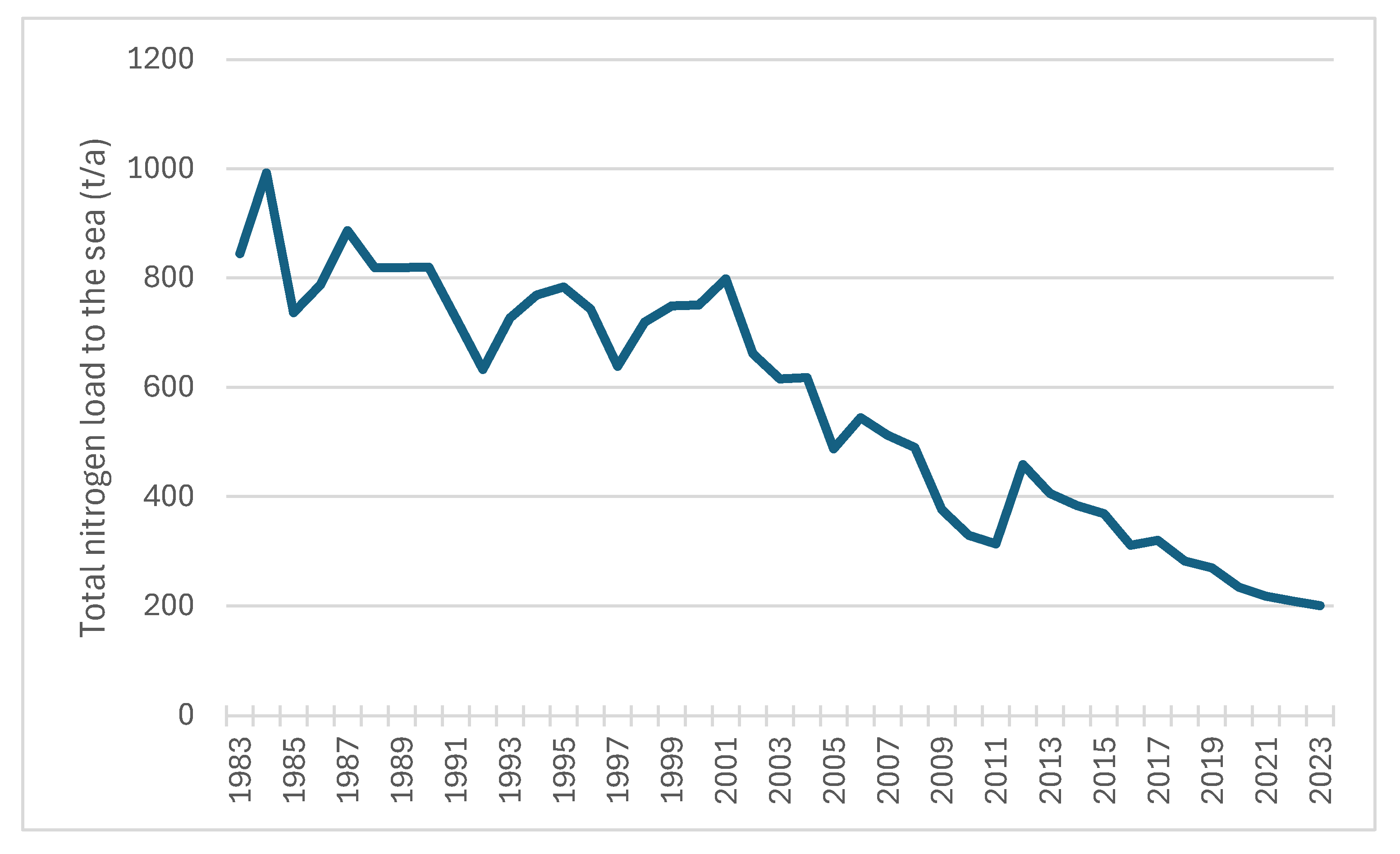

In the 1960s, Turku had approximately 120,000 residents, while its neighboring municipalities—Raisio, Naantali, and Kaarina—had a combined population of around 25,000. By the late 1960s, before wastewater treatment plants were built, the wastewater from 145,000 people was discharged directly into the sea off Turku. It is estimated that this wastewater contributed approximately 120 tons of phosphorus and 740 tons of nitrogen per year to the Archipelago Sea. By 2023, the estimated phosphorus load from wastewater discharged into the sea by the Turku region’s central wastewater treatment plant had decreased to 3.4 tons per year, while the nitrogen load had dropped to 212 tons per year [

6].

The ecological state of the Archipelago Sea has deteriorated over the decades, similar to the rest of the Baltic Sea, but there are significant regional differences between the various archipelago zones [

7]. The inner archipelago is predominantly sheltered and strongly influenced by riverine inputs and, in the past, by local wastewater loads. In the joint monitoring program conducted in the sea area off Turku, the development of water quality has been comprehensively monitored annually since the 1960s. Despite this, the long-term effects of reduced wastewater loads on the ecological state of the sea area have been surprisingly little studied in the Archipelago Sea region. The first summaries in Finnish [

8,

9] were made in the 1990s, when, for example, the phosphorus load from wastewater was still more than four times higher than the current level. In his 2011 review on the development of the state of the Archipelago Sea, Suomela [

10] examined the overall effects of wastewater load reduction.

This study examines in more detail how water quality parameters in wastewater-affected areas off Turku, in the eastern Archipelago Sea, have changed over the same period during which wastewater loads have significantly decreased. For this research, various statistics on wastewater loads have been combined, and environmental management information systems, which store all water quality data, have been utilized. The analysis also investigates changes in the abundance of blue-green algae based on phytoplankton samples. Based on this extensive analysis, the aim is to assess whether achieving good ecological status in the inner archipelago of the Archipelago Sea is possible by further reducing the critical nutrient load.

4. Discussion

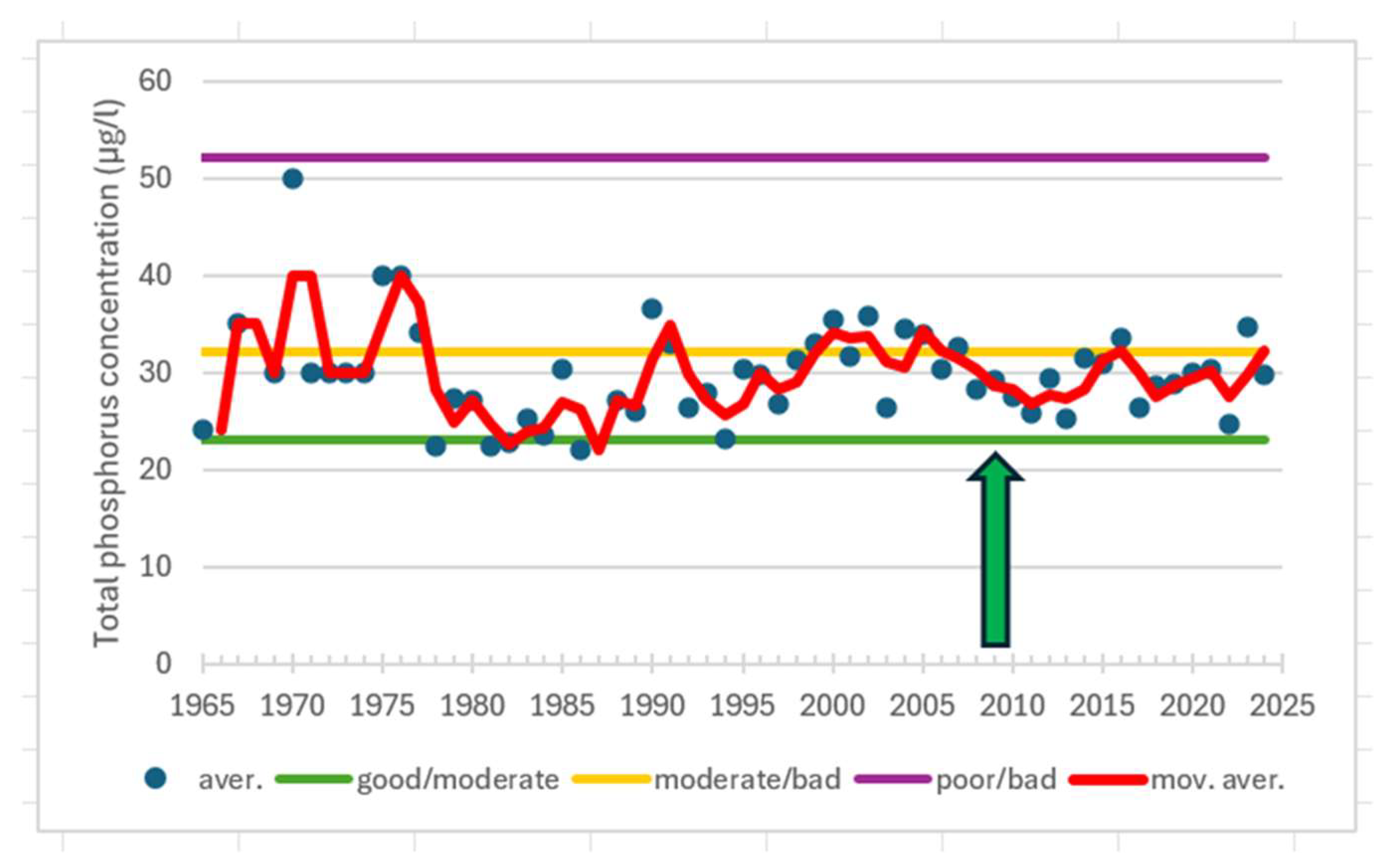

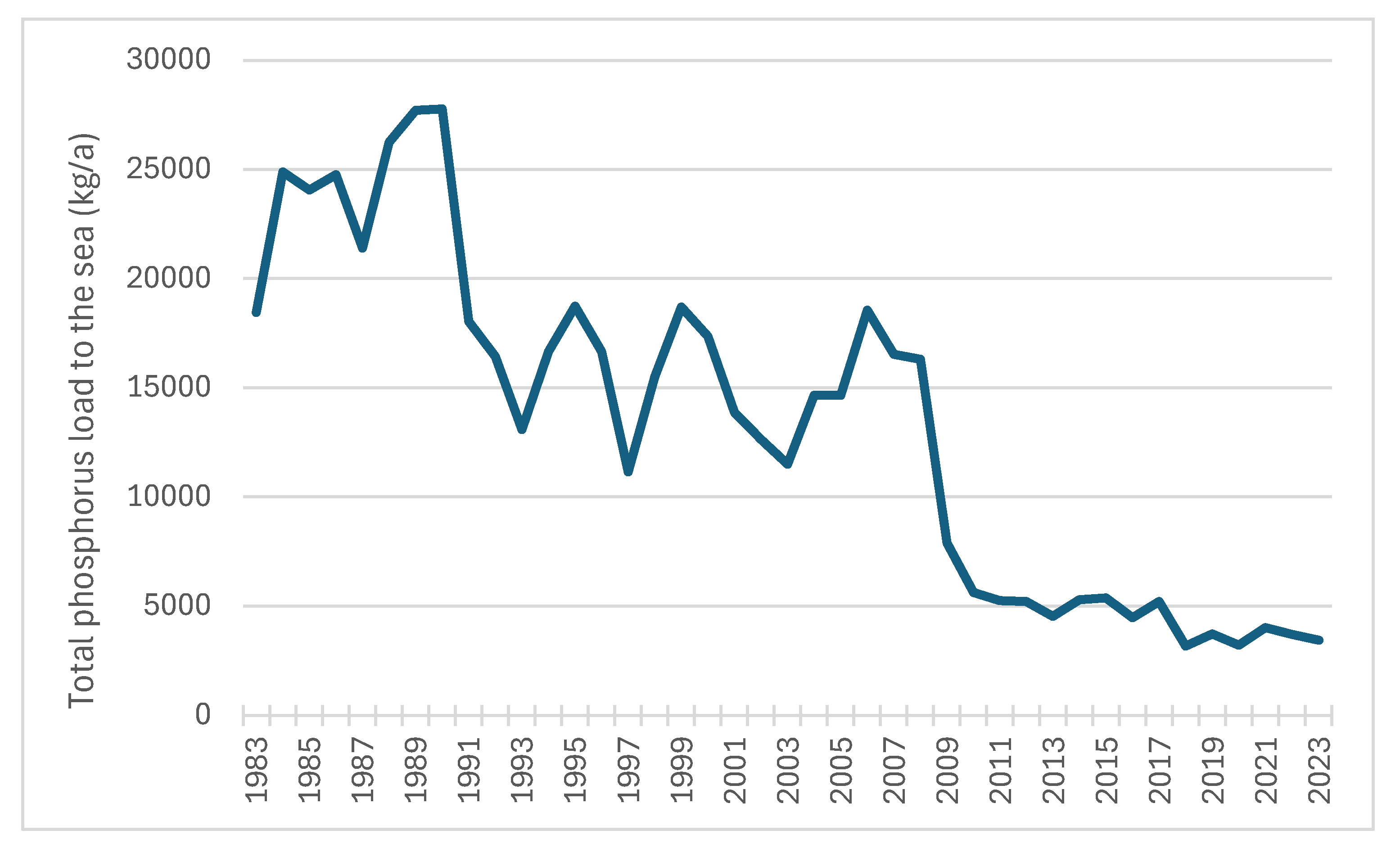

The total phosphorus load in the marine area off Turku was at its highest before the introduction of wastewater treatment in the late 1960s. At that time, the phosphorus load from wastewater into the sea was estimated at 120 t/a, while the phosphorus load from the Aura River was slightly lower than today, at 40 t/a [

10], totaling 160 t/a. The peak nitrogen load, on the other hand, occurred in the early 1980s, when Turku’s population had risen to 160,000 and nitrogen removal at treatment plants was inefficient. At that time, the nitrogen load from wastewater into the sea was approximately 1,000 t/a, while the nitrogen load from the Aura River was at a level similar to today, around 600 t/a, totaling 1,600 t/a. In recent years, the total phosphorus load to the sea off Turku has been 60 t/a, and the total nitrogen load has been 820 t/a. The phosphorus load has decreased by 62.5%, and the nitrogen load has decreased by 49%. Nevertheless, the nutrient load is still too high, as the ecological status of the marine area off Turku in the inner archipelago has, on average, only improved from

bad to

poor. Only at the outer boundary of the inner archipelago (station 220) has the total phosphorus concentration (22.7 µg/l) during the years 2021–2024 been just barely within the

good classification (threshold 23 µg/l). However, even there, the chlorophyll-a concentration (7 µg/l) has remained at a

moderate level.

Based on previous studies, it is known that the total phosphorus concentration in the surface water of the Archipelago Sea has in recent years been at a level of 20 µg/l in the intermediate and outer archipelago zones [

7]. This can be considered a background concentration, below which the total phosphorus concentration in the inner archipelago off Turku would not decrease, even if all local load from the catchment area were to cease. By combining this information with the previously described reduction in phosphorus load and the measured average total phosphorus concentrations, a simple load model is obtained: y = 0.369 x + 19.95, where y is the average phosphorus concentration (µg/l) and x is the phosphorus load into the sea (t/a) (n = 3, p = 0.0015, R

2 = 1).

Using the equation, it can be calculated that achieving a phosphorus concentration of 32 µg/l (the upper limit of the moderate status) would require reducing the phosphorus load to 32.7 t/a from the current 60 t/a, a 45.5% reduction. Similarly, reaching the threshold for good status, a concentration of 23 µg/l, would require lowering the load to 8.3 t/a, representing an 86.2% reduction. Achieving good status in phosphorus concentration would therefore require reducing the phosphorus load from the Aura River from the current 56 t/a to 5 t/a, a 91% reduction, since further phosphorus removal from wastewater is practically no longer feasible. Such a requirement is undoubtedly impossible.

Moreover, even achieving

good status in total phosphorus concentration would not result in a

good status for phytoplankton. Responses in chlorophyll a concentration to reduced total phosphorus levels can be examined using the previously presented regression equation y = 0.314 x–1.19, where y is the average chlorophyll a concentration (µg/l) and x is the average phosphorus concentration (µg/l) (

Figure 25). Using the equation, it can be calculated that a phosphorus concentration of 32 µg/l (the upper limit of

moderate status) would correspond to a chlorophyll a concentration of 8.9 µg/l, while a phosphorus concentration of 23 µg/l (the upper limit of

good status) would correspond to 6.0 µg/l. However, the ecological class threshold is much stricter, especially for the

good status, which requires a chlorophyll a concentration of 3 µg/l, while the threshold for

moderate status is 7 µg/l.

And conversely: achieving the good status threshold for chlorophyll a concentration would require a total phosphorus concentration of 13.3 µg/l, while the satisfactory status threshold would require 26 µg/l. The requirement for good status is so strict that, in practice, it would demand extensive measures across the entire Baltic Sea region, including a 50% reduction in the Baltic Sea’s total phosphorus concentration from current levels, in addition to significant local emission reductions. In fact, very similar conclusions were reached when using the FICOS model to calculate nutrient load ceilings for different Finnish marine areas [

7,

15].

When developing an ecological classification system reference concentrations of chlorophyll a were calculated by substituting the historical values of Secchi depth into the type-specific equations on the relationships between chlorophyll a and Secchi depth [

15]. However, statistical modeling could not be used for inner coastal types because historical Secchi depth values were missing. For inner coastal types, reference values have been estimated by relating the 5th percentile of current monitoring results to the reference values of outer coastal types [

16].

While it seems obvious that, in the inner archipelago zone, the requirements for good status would be too strict and impossible to achieve, one option would be to refine the classification thresholds by reanalyzing the observation data. In the inner archipelago, it might be sufficient to adjust the current upper limit for moderate status (7 µg/l) to be the threshold for good status, redefine the lower limit for poor status (17 µg/l) as moderate, and set the poor status threshold at around 30 µg/l.

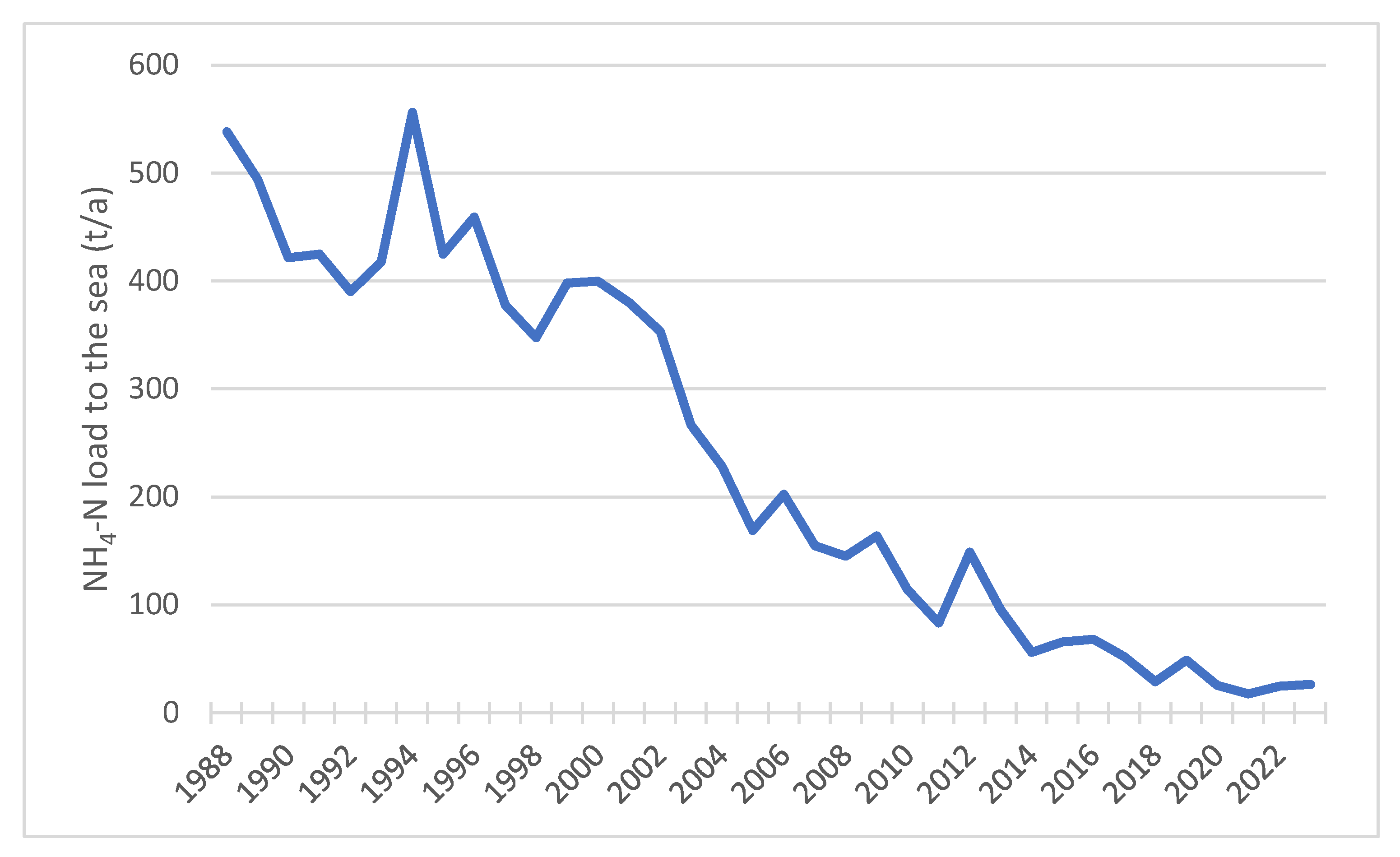

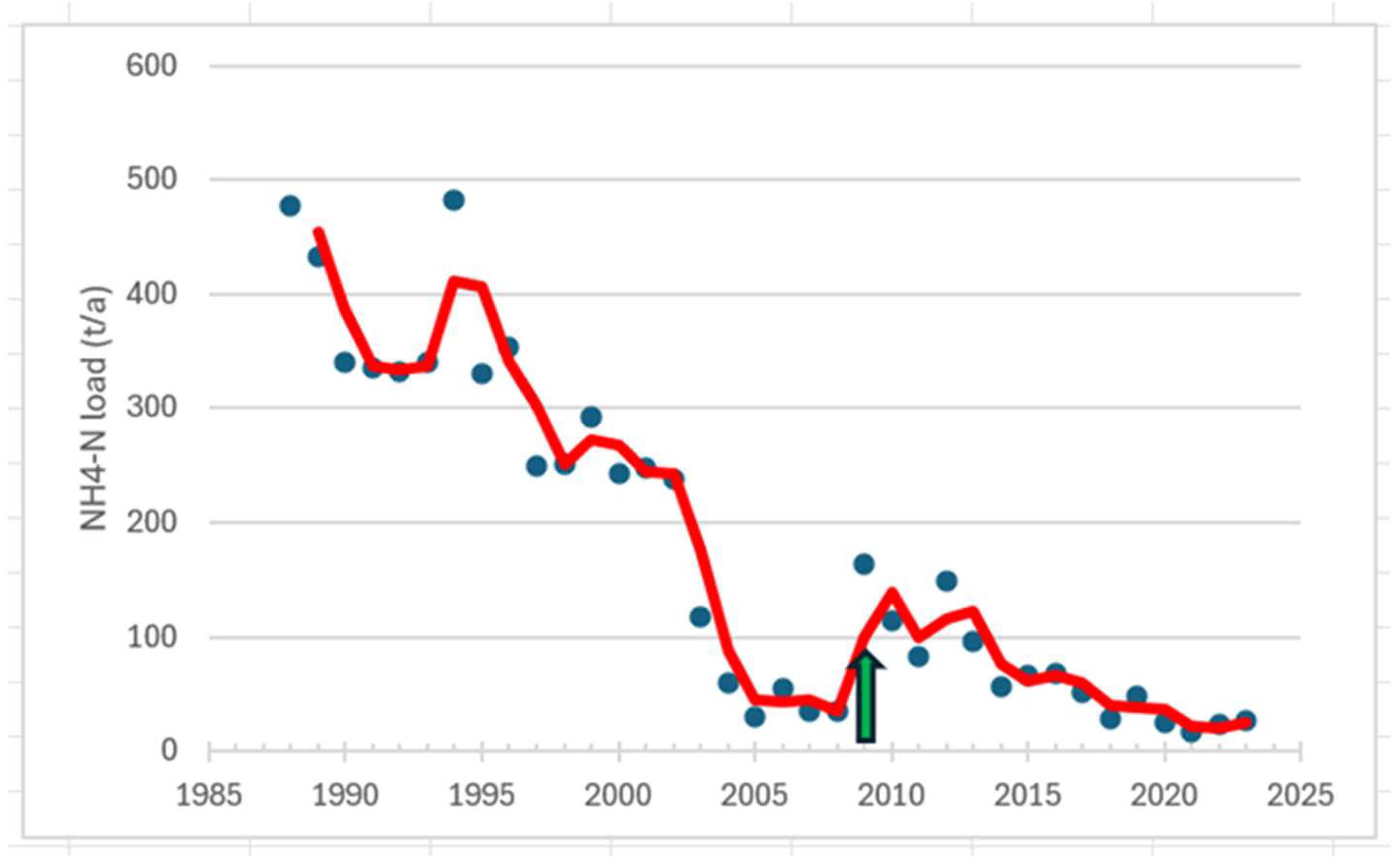

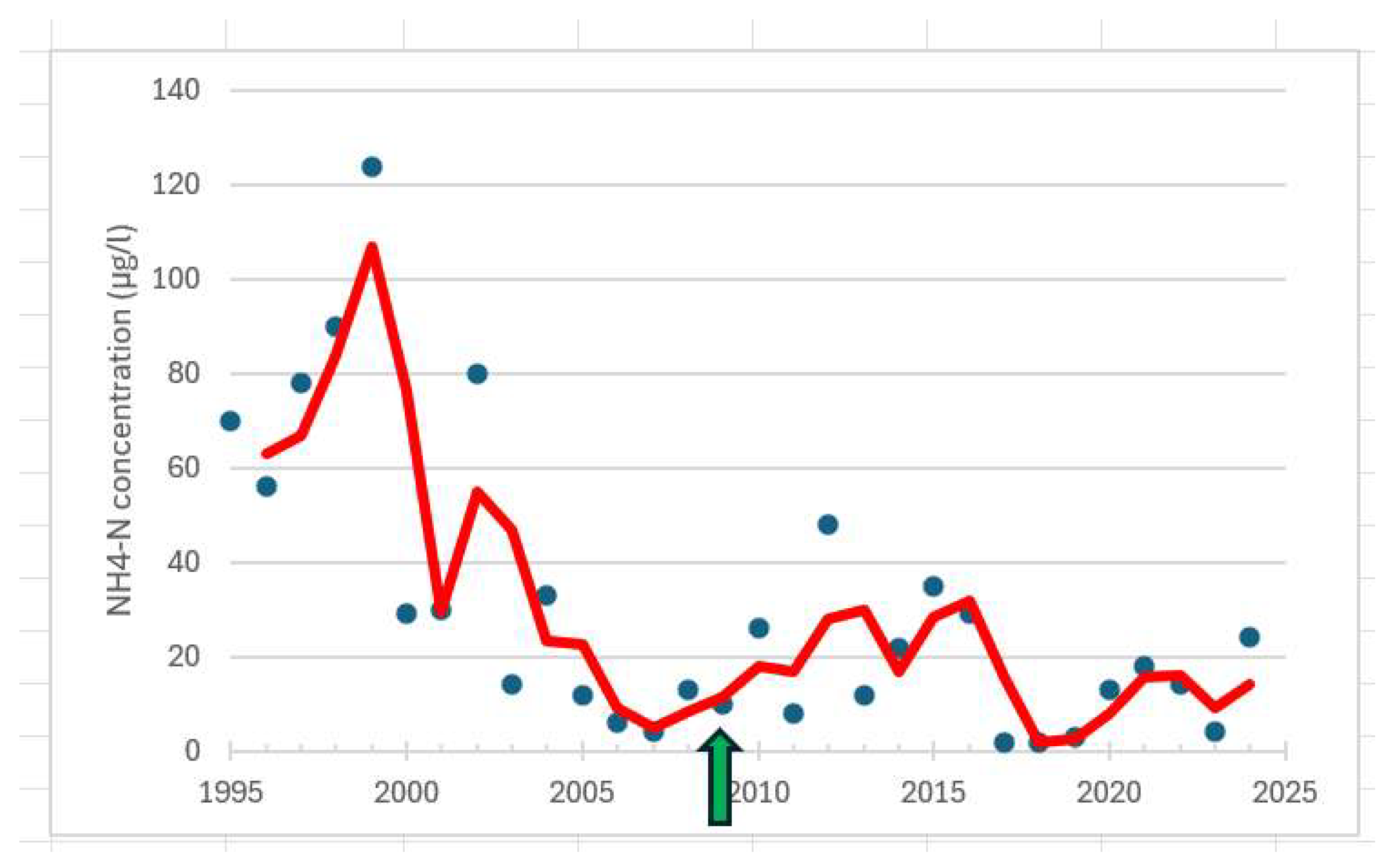

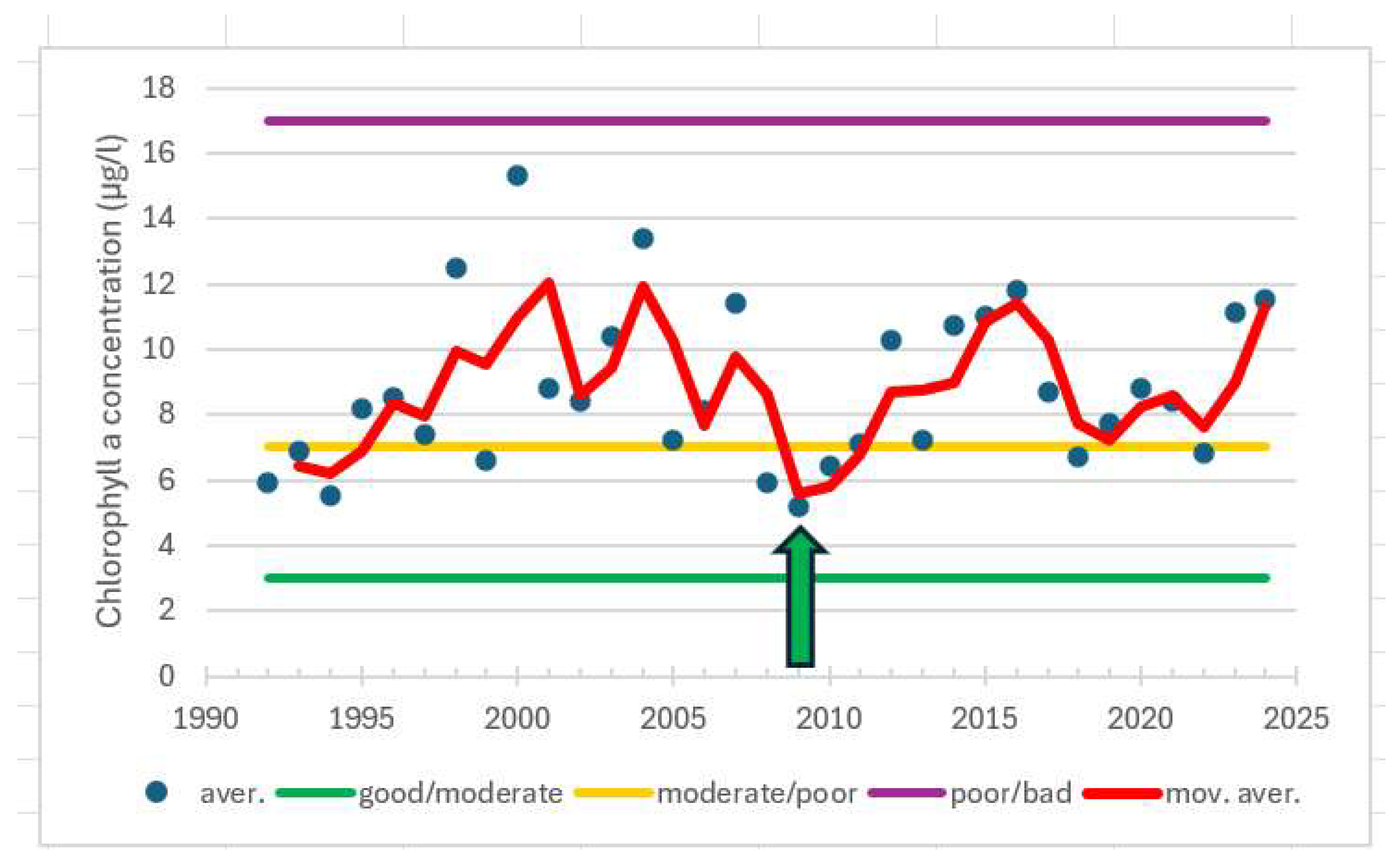

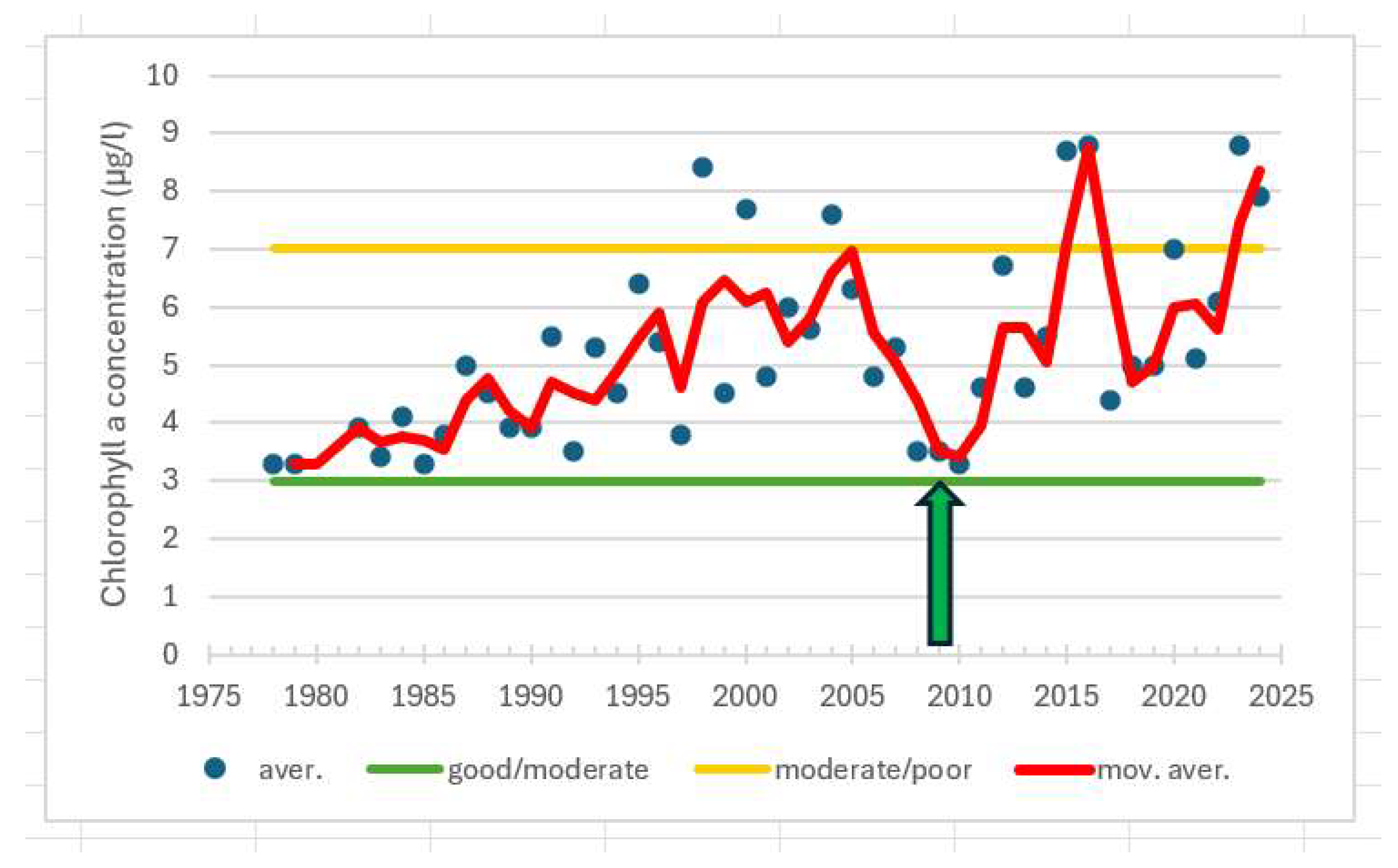

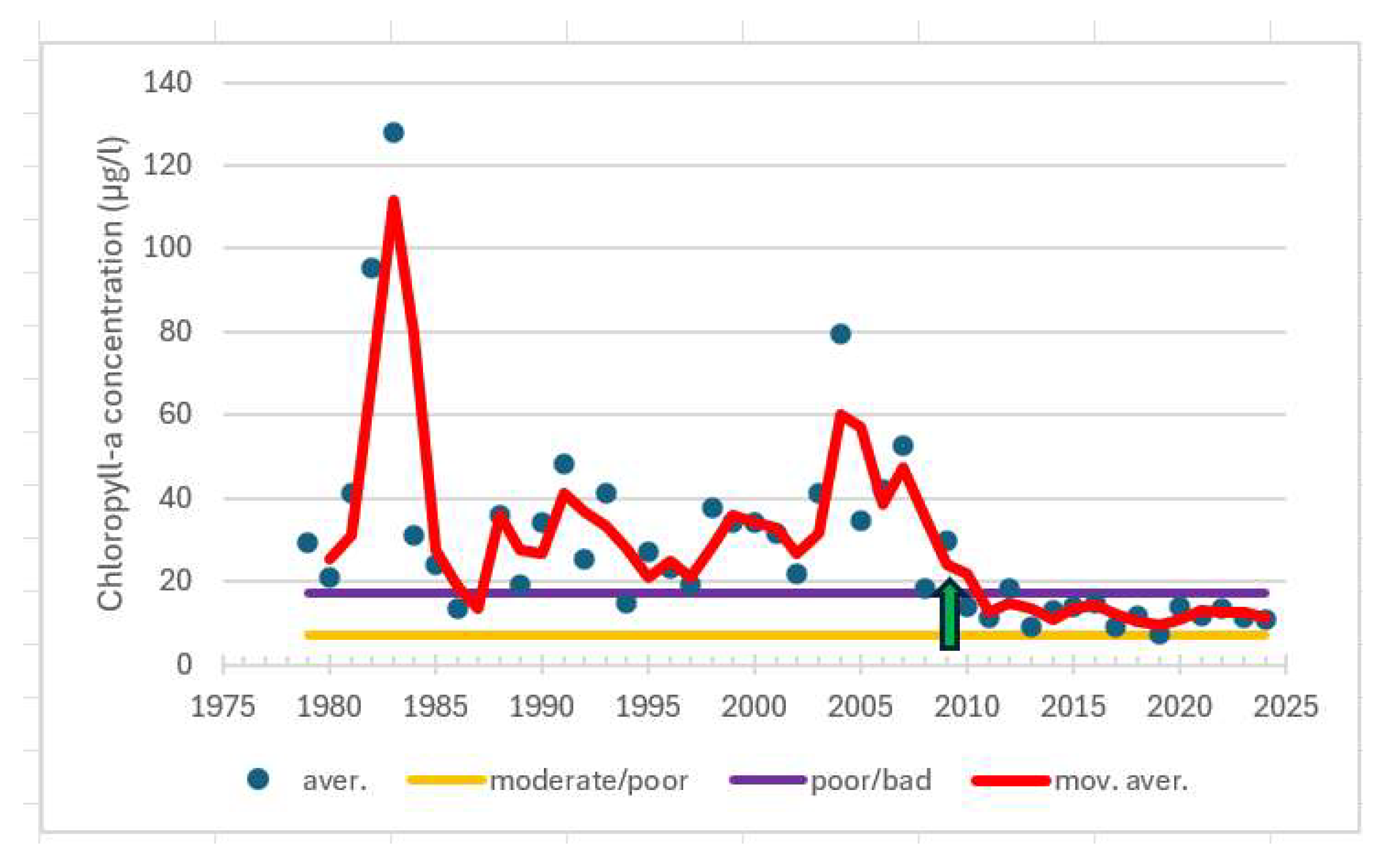

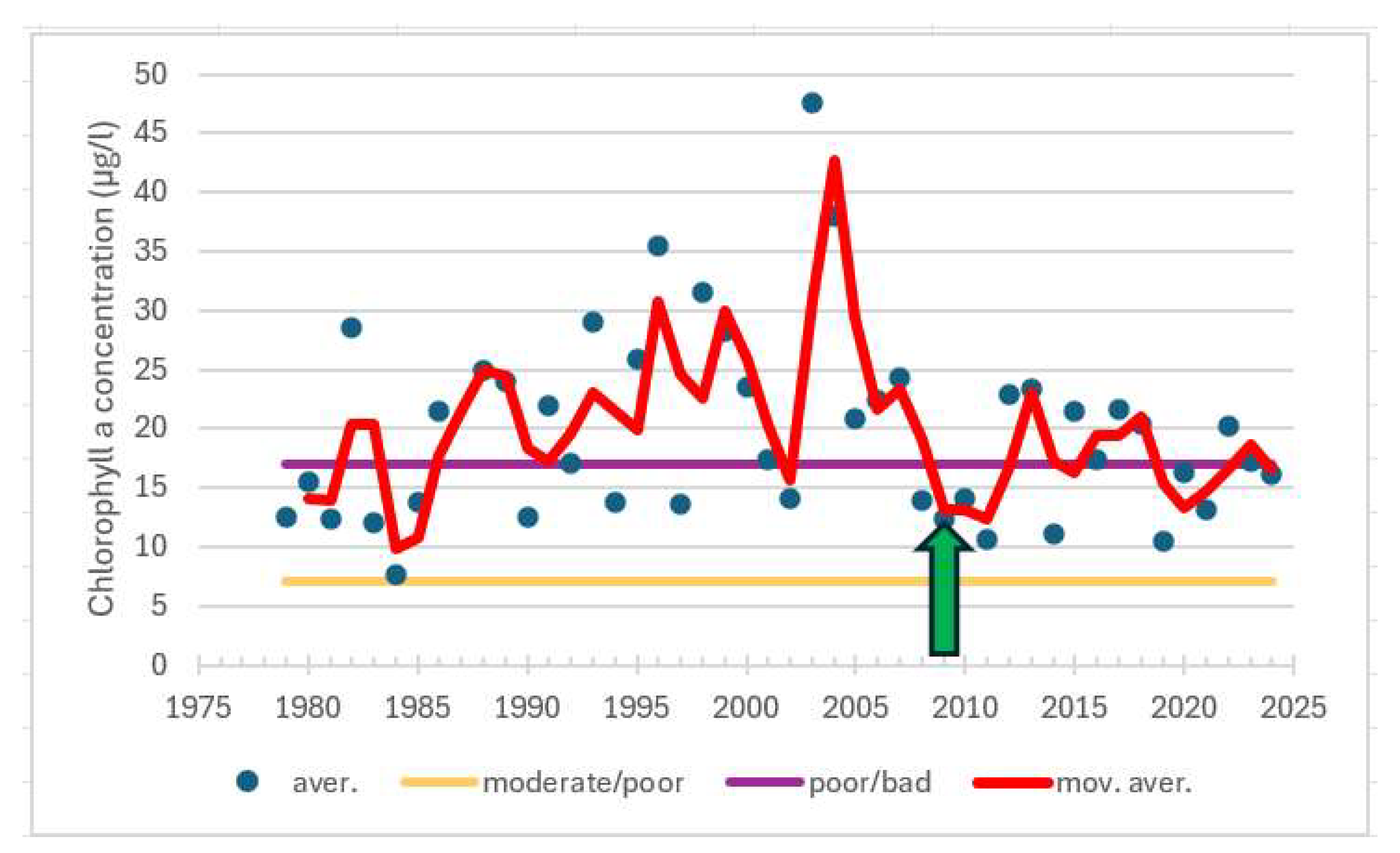

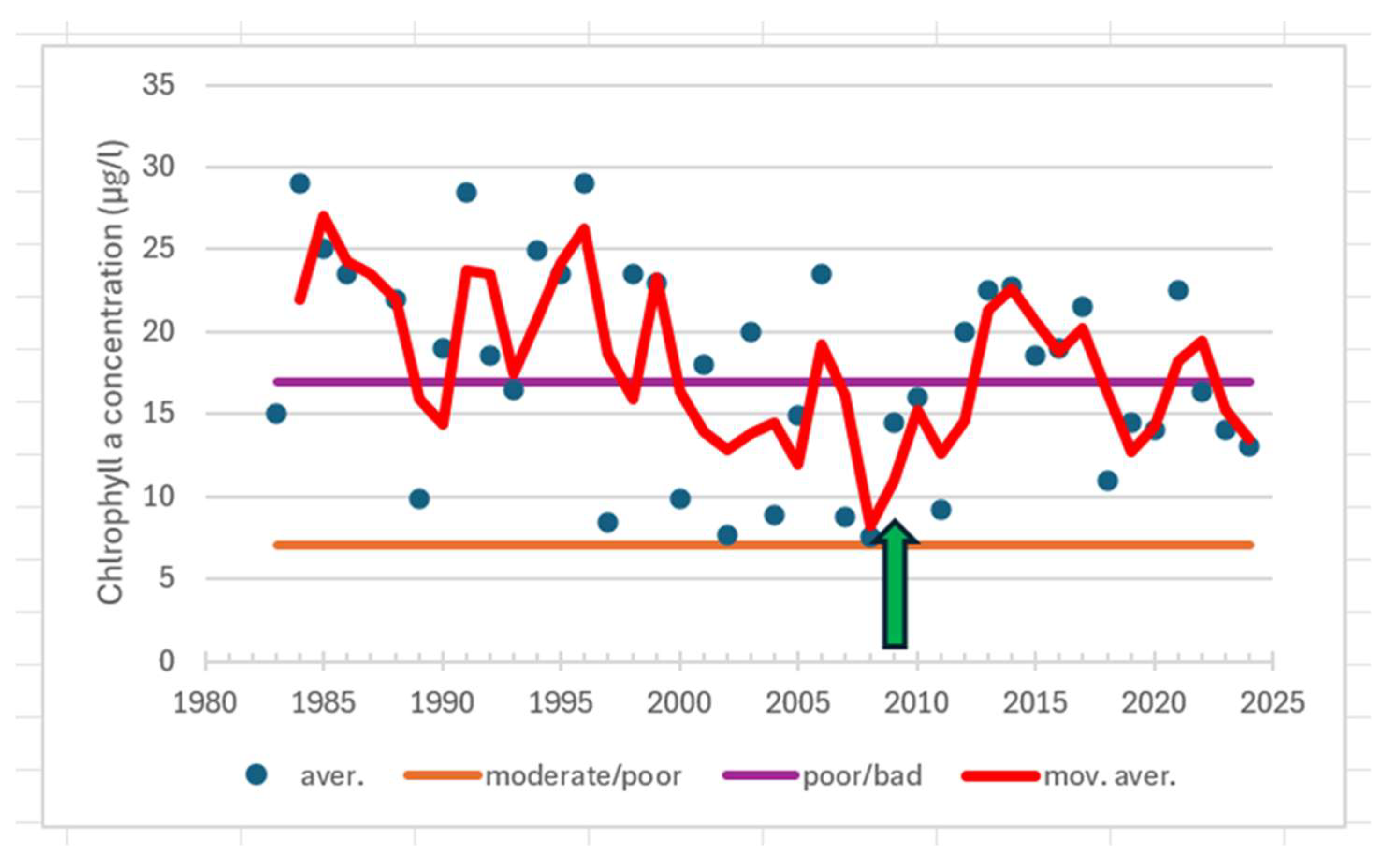

In any case, the wastewater treatment implemented has led to positive developments in water quality in the marine area off Turku, even though the goal of good status is still a way off. In Raisio Bay, the chlorophyll-a concentration, which indicates algal production, decreased by 68% when wastewater discharge was transferred to Kakola. Similarly, in Rauvola Bay near Kaarina, the reduction in chlorophyll-a concentration was estimated to be 36%. At the outer boundary of the inner archipelago, in Airisto at stations 210 and 220, the observed decrease in chlorophyll concentration in the early 2000s—approximately 40% between 2000 and 2009—appears to be linked to a significant reduction in ammonium nitrogen loading from wastewaters.

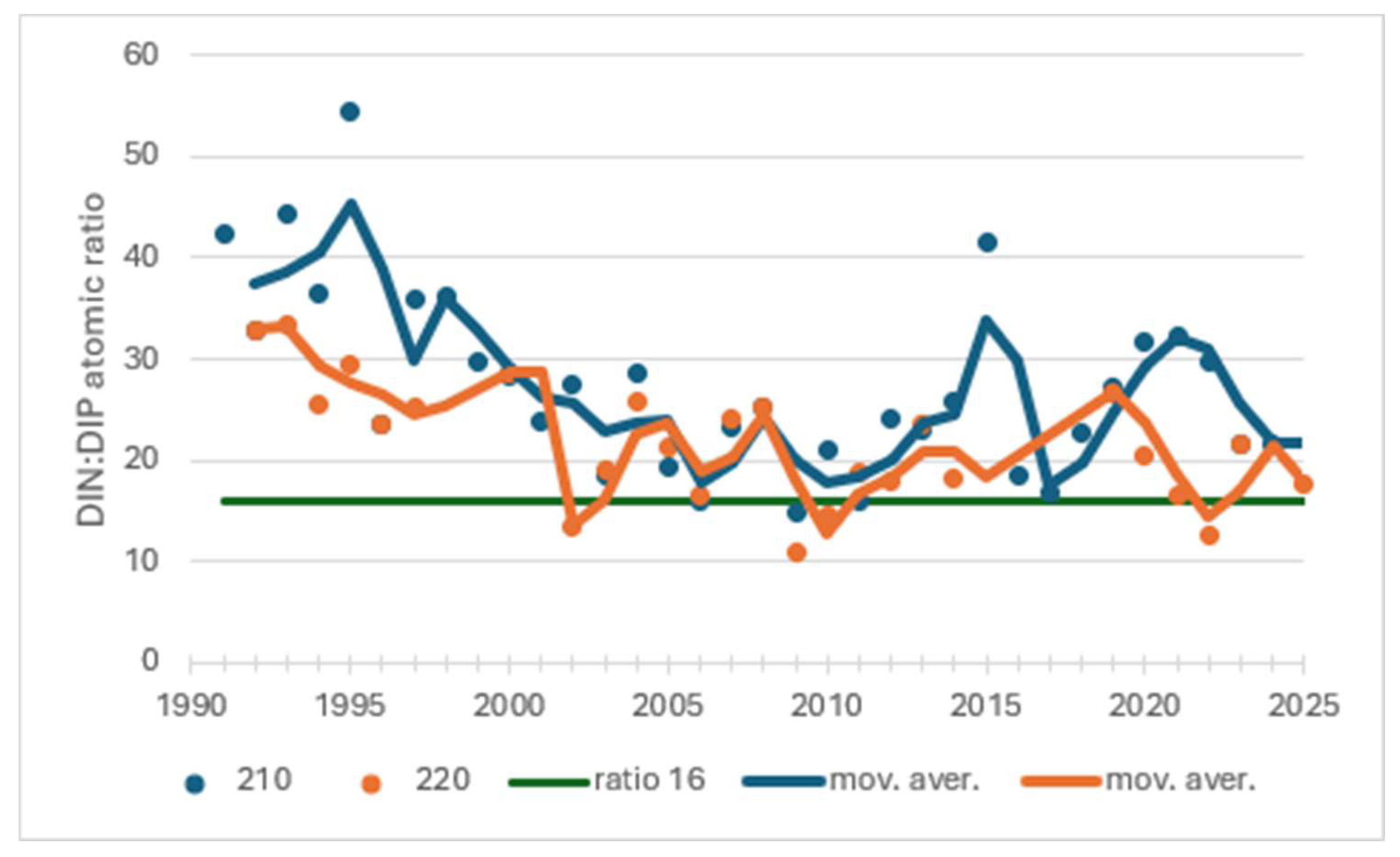

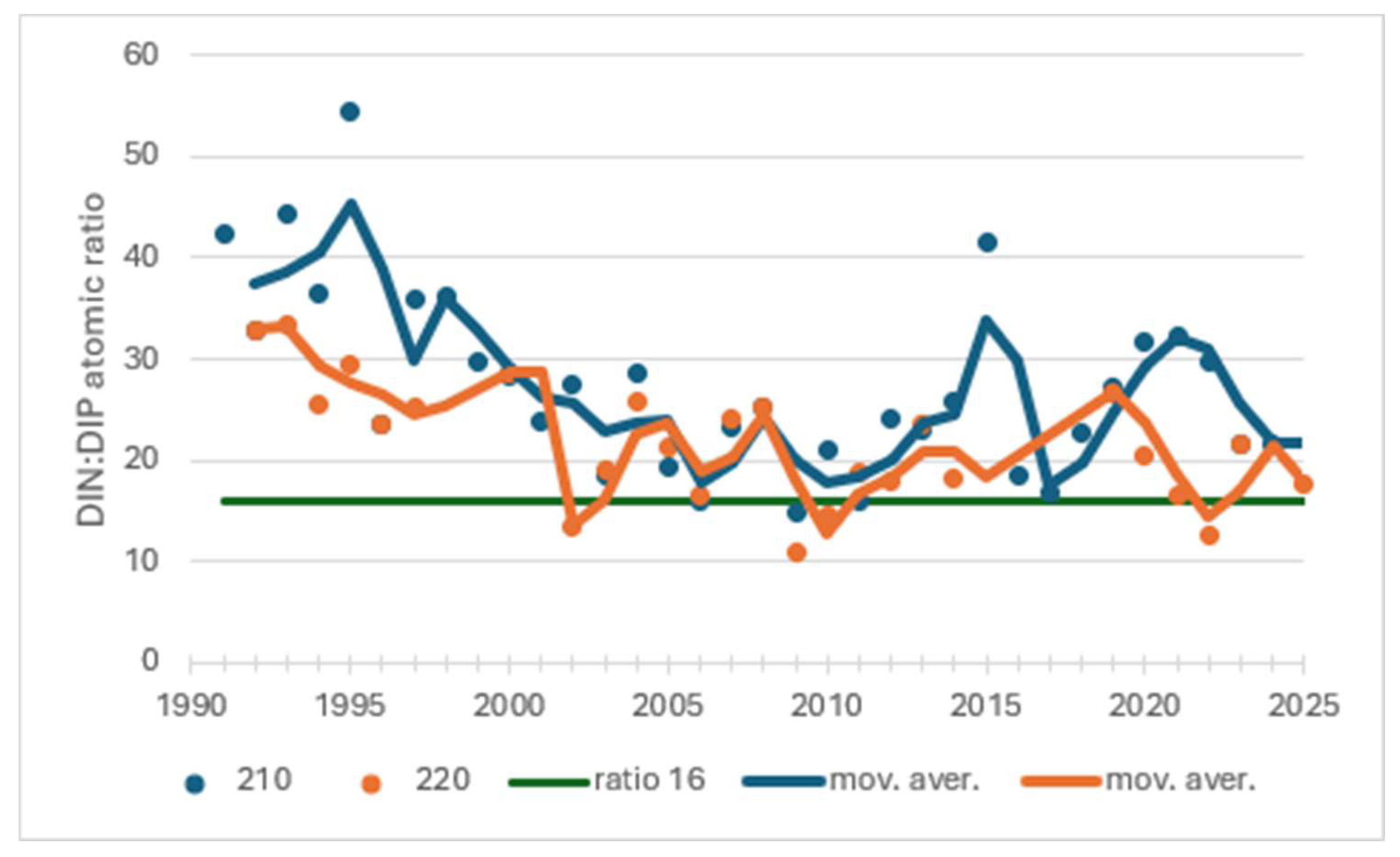

What’s interesting at these Airisto stations 210 and 220, however, is the development since 2009. Chlorophyll concentrations started to rise again, and the variation between years also increased, even though ammonium nitrogen and phosphorus loading from wastewater continued to decrease. Between 2009 and 2011, NH4-N loading to the sea was about 120 tons per year, while between 2021 and 2023, it was 23 tons per year. It is also worth noting that before the Kakola treatment plant started operating, in 2007-2008, NH4 loading had decreased to 35 tons per year. Phosphorus loading, on the other hand, has steadily decreased throughout the entire observation period. Between 2009 and 2011, it was 6.3 tons per year, while between 2021 and 2023, it was 3.7 tons per year.

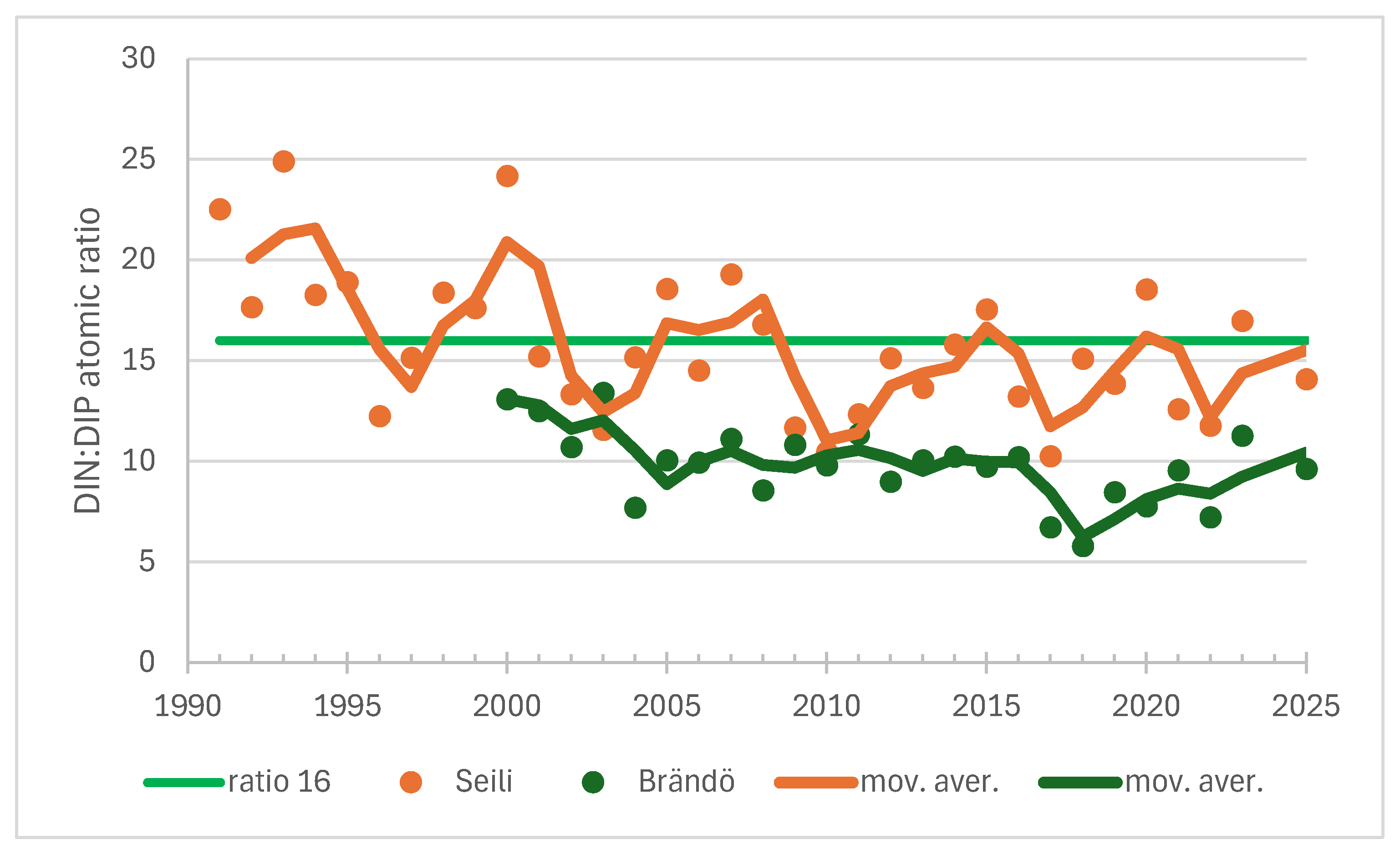

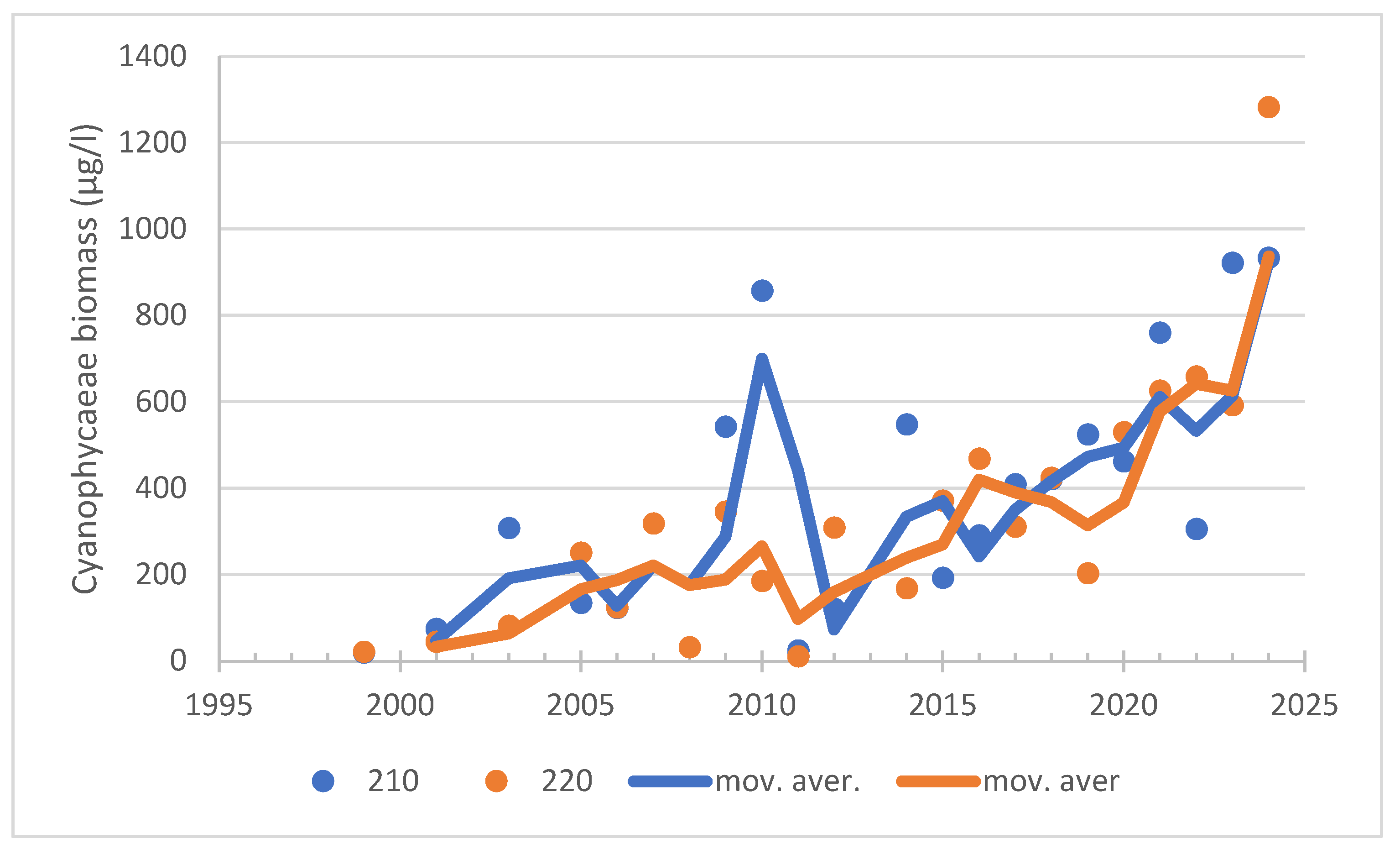

Since 2009, cyanobacterial biomass at the Airisto stations 210 and 220 has clearly increased compared to previous years and the situation in southern Airisto at the Seili station. Nutrient ratio analyses show that, at the same time, the system seems to have shifted towards nitrogen limitation, which favors nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria, such as species of the Nostocales order like

Aphanizomenon sp. [

17,

18] Due to the ability of nitrogen fixation, cyanobacteria are a nitrogen source for the system [

19]. So, we can think that they, in part, nullify the work of wastewater treatment plants in reducing nitrogen removal. If internal phosphorus loading increases simultaneously and more dissolved phosphorus becomes available for phytoplankton, the result is an increase in algal production. This kind of development has been observed in the chlorophyll-a concentrations at Airisto stations 210 and 220 since 2009 (

Figure 16 and

Figure 17). The temporal development of internal P loading intensity has not been studied in detail in the Archipelago Sea. The observed increase in wintertime dissolved phosphorus concentration at station 201 (

Figure 20) does indeed suggest a strengthening of internal loading. It is also known that if the relative loading is calculated based on the amount of phosphorus reaching the upper surface layers (0–20 m), it is highest in the inner archipelago [

7].

In this study, the interpretation of the minimum nutrient was based on the dissolved nutrient DIN:DIP ratios derived from monitoring data. This approach has limitations compared to, for example, similar experimental studies [

20]. During the summer, dissolved nutrients cannot be measured from the productive surface layer using traditional water analyses, as all the available nutrient fractions are utilized by phytoplankton species and bacteria [

12]. Therefore, nutrient ratios measured at other times of the year must be used as indicators for assessing nutrient availability. In this study, winter nutrient data were primarily used, as they are suitable for evaluating concentrations caused by steady wastewater loading. The data from Airisto station 220 were also used to calculate DIN:DIP ratios which based on molar concentrations of deep-water layers (over 20 m) during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September). Based on this, a clearer change was observed from 2009 onwards compared to the DIN:DIP ratios based on winter data. Earlier analysis like [P] have in any case shown that rather simple ratios can reflect phytoplankton requirement for nutrients. However, from the management point of view, it is important to be aware that prevailing N-limitation will be more difficult to detect from nutrient data than prevailing P-limitation [

13].

Cyanobacteria blooms and N

2 fixation have been closely linked to eutrophication of the Baltic Sea. Enhanced internal loading of phosphorus and the removal of dissolved inorganic nitrogen leads to lower nitrogen to phosphorus ratios, which are one of the main factors promoting nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria blooms [

21]. Vahtera et al. described the coupled processes inducing internal loading, nitrogen removal, and the prevalence of nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria as a potentially self-sustaining “vicious circle” [

21]. They concluded that to effectively reduce cyanobacteria blooms and overall signs of eutrophication, reductions in both nitrogen and phosphorus external loads appear essential.

But on the other hand, at least the results of ecosystem modeling by Neumann et al. [

22] predicted that, in a medium-term perspective, a proportional reduction of nitrogen and phosphorus at the same time does not have the desired reducing effect on phytoplankton development in the open sea. In summer, the shortage of nitrogen has inhibitory effects on all phytoplankton groups, with exception of cyanobacteria. Neumann et al. concluded that a possible solution can be an early and increased reduction of phosphorus load [

21]. All phytoplankton groups are limited by phosphorus availability. An increased reduction of phosphorus can be supported by the fact that the increase in phosphorus load was twice compared with nitrogen in the last century [

23].

Figure 1.

Map of the study area and the locations of water quality monitoring stations, which are marked on the map with red triangles. The discharge pipes of wastewater treatment plants are marked with stars: Yellow—Naantali, Kaarina, Green—The current central wastewater treatment plant of the Turku region.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area and the locations of water quality monitoring stations, which are marked on the map with red triangles. The discharge pipes of wastewater treatment plants are marked with stars: Yellow—Naantali, Kaarina, Green—The current central wastewater treatment plant of the Turku region.

Figure 2.

Total phosphorus load (kg/a) of waste waters to the sea in the coastal area off Turku.

Figure 2.

Total phosphorus load (kg/a) of waste waters to the sea in the coastal area off Turku.

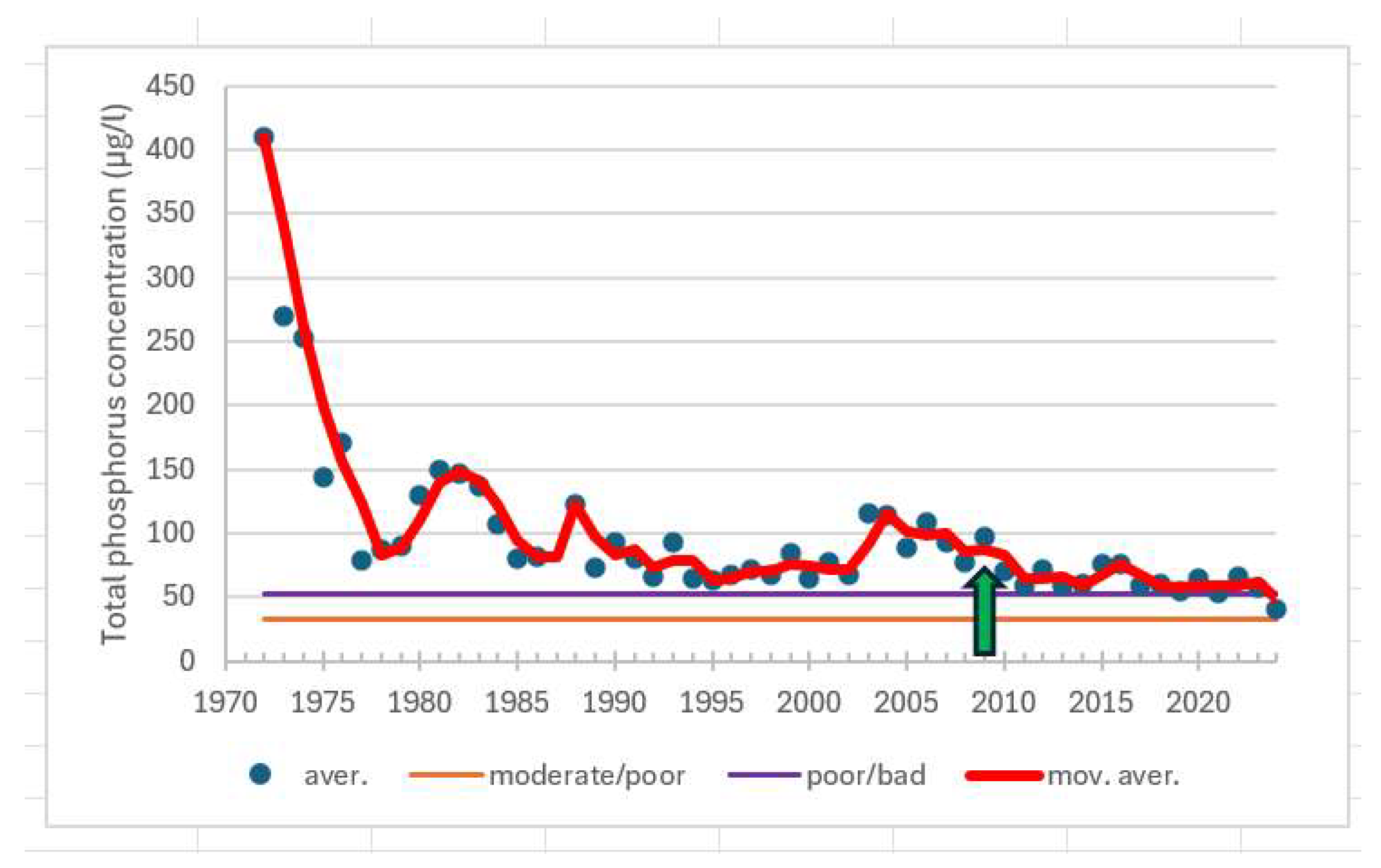

Figure 6.

Total phosphorus concentrations (µg/l) of surface water in monitoring station Turm 260 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1970 to 2024. The poor status lower threshold (moderate/poor) is 32 µg/L and the upper (poor/bad) is 52 µg/L. The red line indicates the moving average in the total phosphorus concentration over the entire period under review. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

Figure 6.

Total phosphorus concentrations (µg/l) of surface water in monitoring station Turm 260 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1970 to 2024. The poor status lower threshold (moderate/poor) is 32 µg/L and the upper (poor/bad) is 52 µg/L. The red line indicates the moving average in the total phosphorus concentration over the entire period under review. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

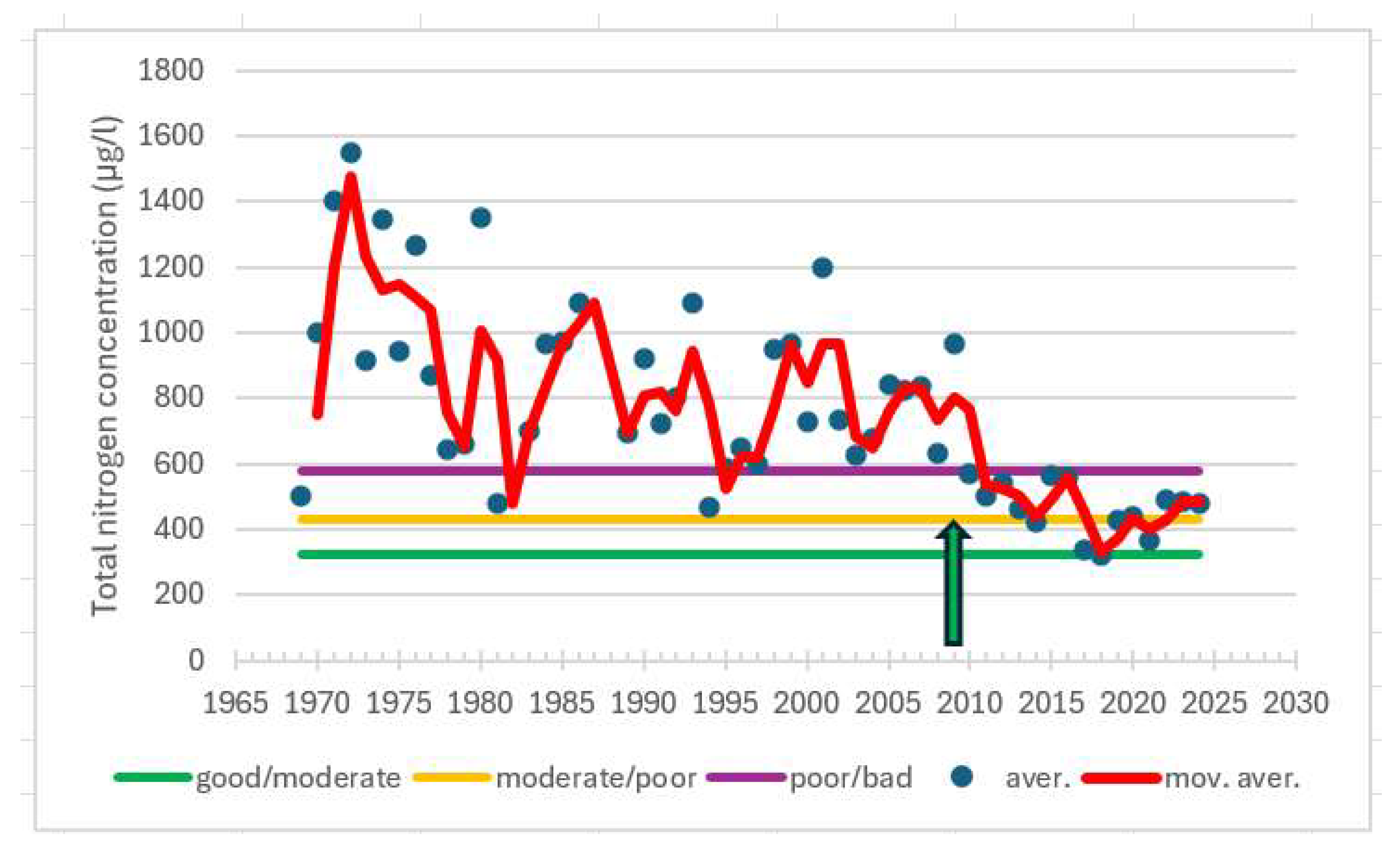

Figure 7.

Total nitrogen concentrations (µg/l) of surface water in monitoring station Turm 260 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1969 to 2024. The moderate status lower threshold (good/moderate) is 325 µg/L and the upper (moderate/poor) is 430 µg/L. The bad status lower threshold (poor/bad) is 575 µg/L The red line indicates the moving average in the total phosphorus concentration over the entire period under review. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

Figure 7.

Total nitrogen concentrations (µg/l) of surface water in monitoring station Turm 260 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1969 to 2024. The moderate status lower threshold (good/moderate) is 325 µg/L and the upper (moderate/poor) is 430 µg/L. The bad status lower threshold (poor/bad) is 575 µg/L The red line indicates the moving average in the total phosphorus concentration over the entire period under review. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

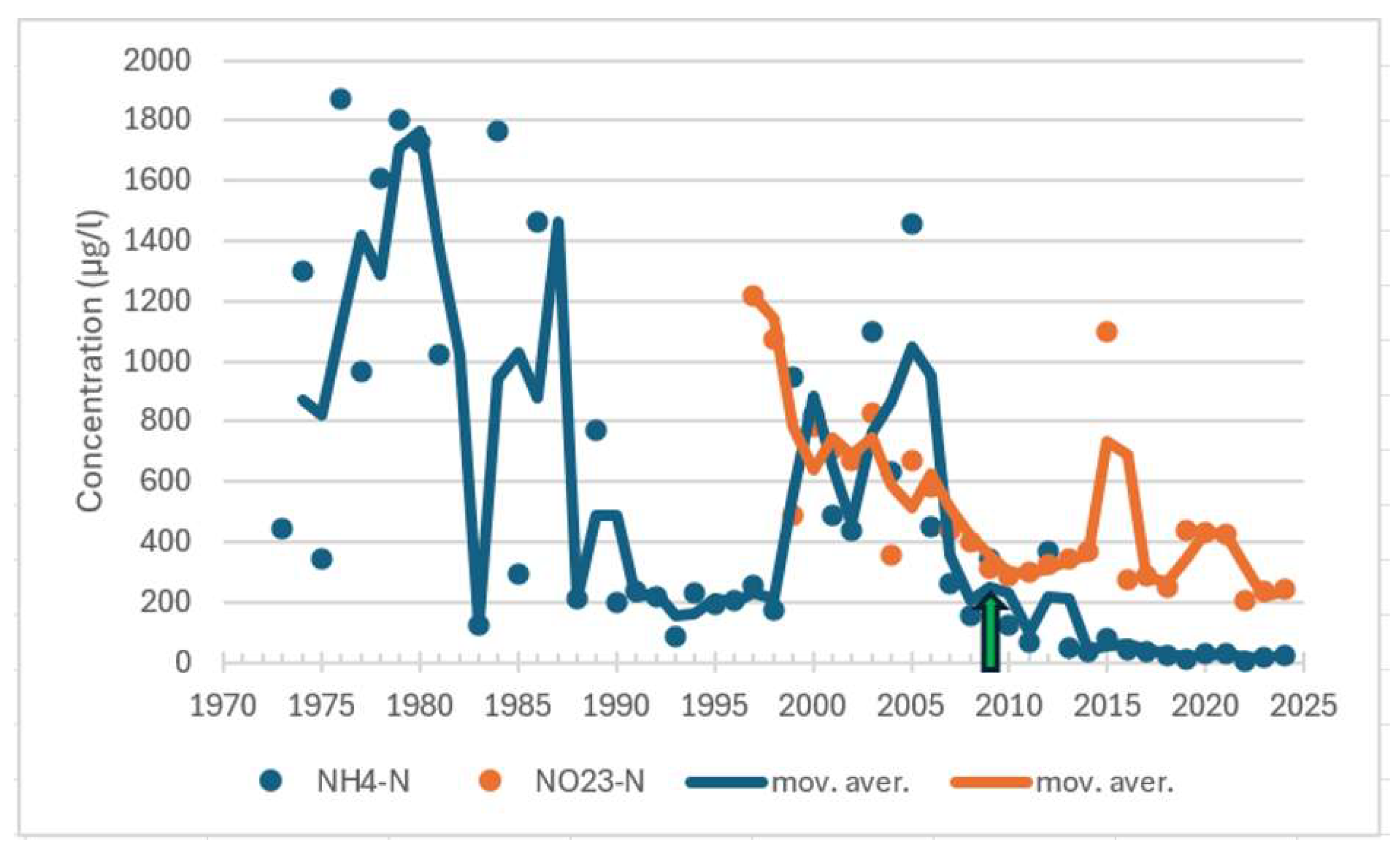

Figure 8.

Ammonium nitrogen (NH4-N) and nitrite-nitrate nitrogen (NO23-N) concentrations (µg/l) of surface water in monitoring station Turm 260 during the wintertime (1 January–31 March) from 1970 to 2024. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

Figure 8.

Ammonium nitrogen (NH4-N) and nitrite-nitrate nitrogen (NO23-N) concentrations (µg/l) of surface water in monitoring station Turm 260 during the wintertime (1 January–31 March) from 1970 to 2024. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

Figure 9.

The concentration of chlorophyll-a (µg/L) in surface water (0–10 m) at observation station Turm 260 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1979 to 2024. The poor status lower threshold (moderate/poor) is 7.0 µg/L and the upper (poor/bad) is 17.0 µg/L. The red line indicates the moving average in the chlorophyll-a concentration over the entire period under review. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

Figure 9.

The concentration of chlorophyll-a (µg/L) in surface water (0–10 m) at observation station Turm 260 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1979 to 2024. The poor status lower threshold (moderate/poor) is 7.0 µg/L and the upper (poor/bad) is 17.0 µg/L. The red line indicates the moving average in the chlorophyll-a concentration over the entire period under review. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

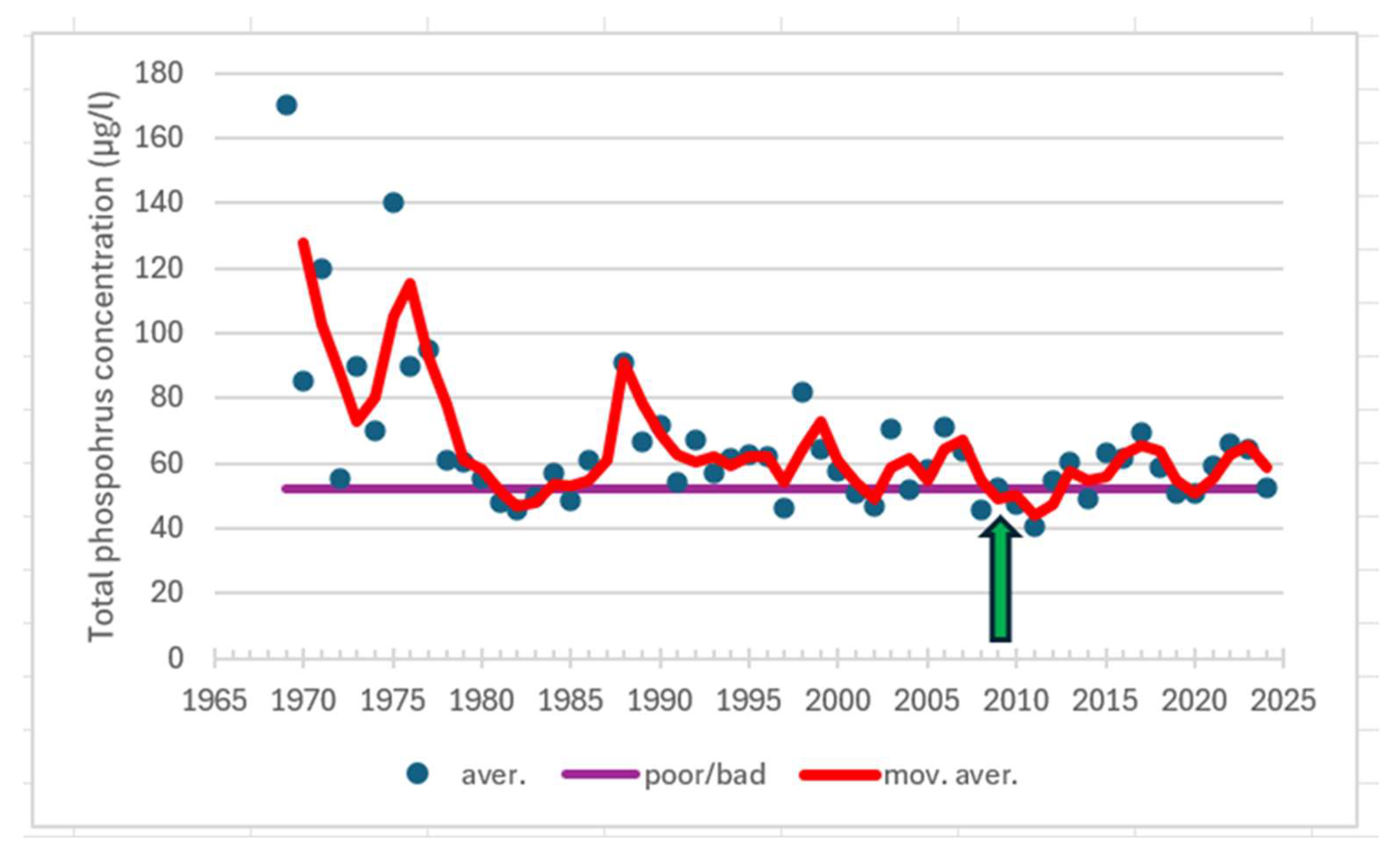

Figure 10.

Total ph osphorus concentrations (µg/l) of surface water in monitoring station Turm 175 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1970 to 2024. The poor status lower threshold (moderate/poor) is 32 µg/L and the upper (poor/bad) is 52 µg/L. The red line indicates the moving average in the total phosphorus concentration over the entire period under review. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

Figure 10.

Total ph osphorus concentrations (µg/l) of surface water in monitoring station Turm 175 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1970 to 2024. The poor status lower threshold (moderate/poor) is 32 µg/L and the upper (poor/bad) is 52 µg/L. The red line indicates the moving average in the total phosphorus concentration over the entire period under review. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

Figure 11.

The concentration of chlorophyll-a (µg/L) in surface water (0–10 m) at observation station Turm 175 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1979 to 2024. The poor status lower threshold (moderate/poor) is 7.0 µg/L and the upper (poor/bad) is 17.0 µg/L. The red line indicates the moving average in the chlorophyll-a concentration over the entire period under review. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

Figure 11.

The concentration of chlorophyll-a (µg/L) in surface water (0–10 m) at observation station Turm 175 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1979 to 2024. The poor status lower threshold (moderate/poor) is 7.0 µg/L and the upper (poor/bad) is 17.0 µg/L. The red line indicates the moving average in the chlorophyll-a concentration over the entire period under review. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

Figure 12.

Ammonium nitrogen (NH4-N) concentrations (µg/l) of surface water in monitoring station Turm 190 during the wintertime (1 January–31 March) from 2000 to 2024. The green arrow indicates the time when Kaarina’s and Raisio’s wastewater began to be directed to Turku’s Kakola treatment plant (2009).

Figure 12.

Ammonium nitrogen (NH4-N) concentrations (µg/l) of surface water in monitoring station Turm 190 during the wintertime (1 January–31 March) from 2000 to 2024. The green arrow indicates the time when Kaarina’s and Raisio’s wastewater began to be directed to Turku’s Kakola treatment plant (2009).

Figure 13.

The concentration of chlorophyll-a (µg/L) in surface water (0–10 m) at observation station Turm 190 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1983 to 2024. The poor status lower threshold (moderate/poor) is 7.0 µg/L and the upper (poor/bad) is 17.0 µg/L. The red line indicates the moving average in the chlorophyll-a concentration over the entire period under review. The green arrow indicates the time when Kaarina’s and Raisio’s wastewater began to be directed to Turku’s Kakola treatment plant (2009).

Figure 13.

The concentration of chlorophyll-a (µg/L) in surface water (0–10 m) at observation station Turm 190 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1983 to 2024. The poor status lower threshold (moderate/poor) is 7.0 µg/L and the upper (poor/bad) is 17.0 µg/L. The red line indicates the moving average in the chlorophyll-a concentration over the entire period under review. The green arrow indicates the time when Kaarina’s and Raisio’s wastewater began to be directed to Turku’s Kakola treatment plant (2009).

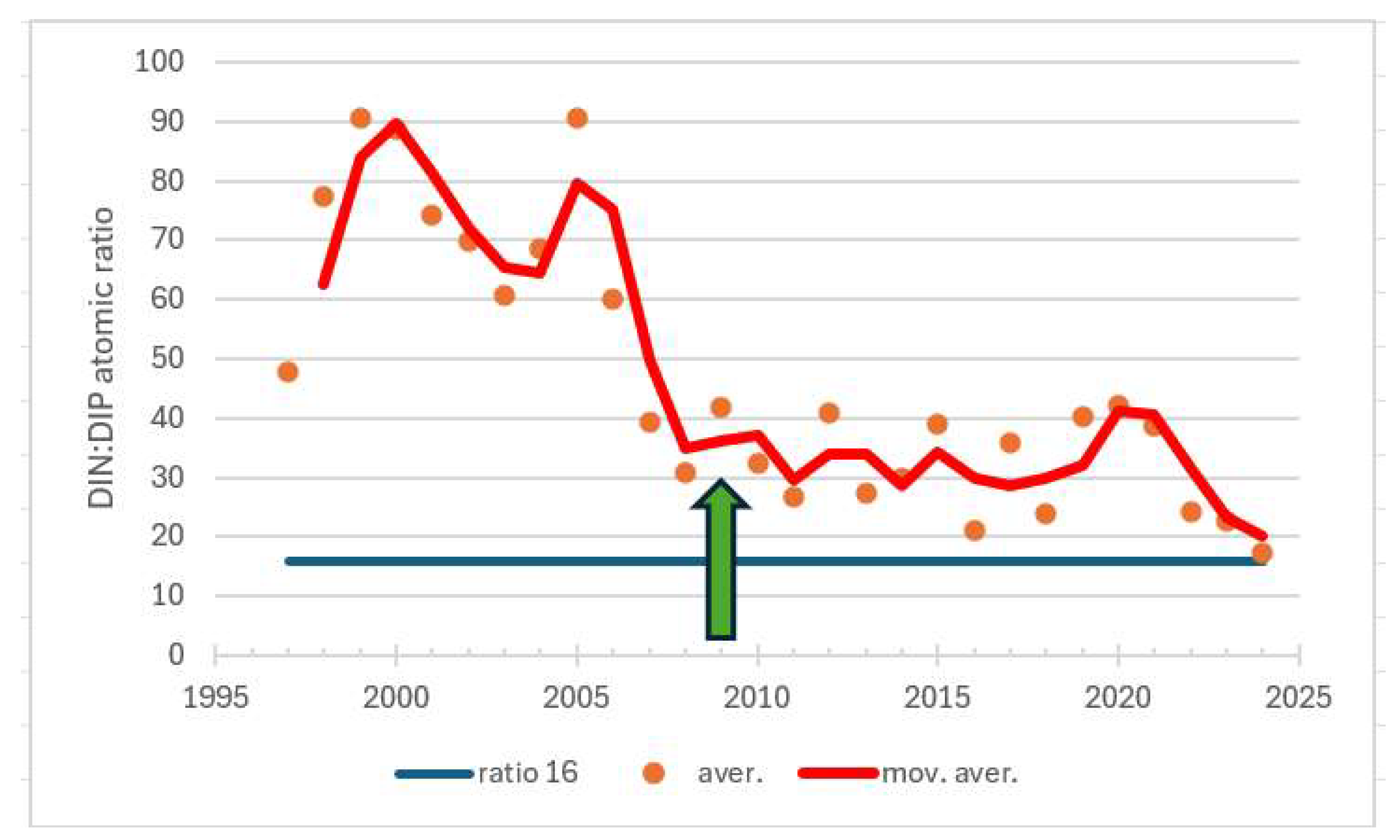

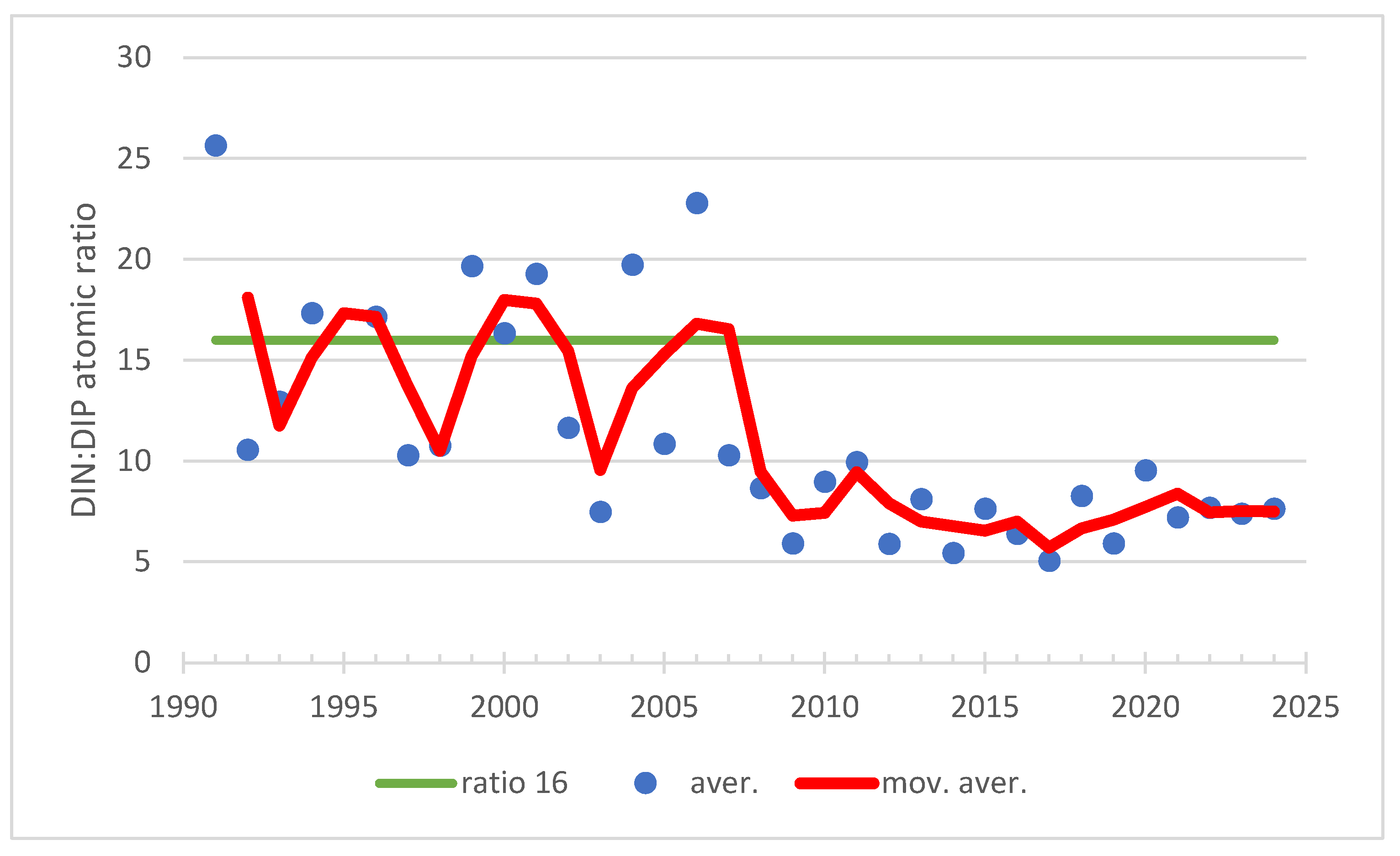

Figure 18.

The wintertime (January 1–March 31) DIN:DIP ratios based on molar concentrations at the Raisio Bay station 260 during 1997-2024. The Redfield ratio 16:1 is marked with a green crossline. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

Figure 18.

The wintertime (January 1–March 31) DIN:DIP ratios based on molar concentrations at the Raisio Bay station 260 during 1997-2024. The Redfield ratio 16:1 is marked with a green crossline. The green arrow indicates the time when the wastewater load ceased (2009).

Figure 19.

The wintertime (January 1–March 31) DIN:DIP ratios based on molar concentrations at the Airisto stations 210 and 220 during 1997-2024. The Redfield ratio 16:1 is marked with a green crossline.

Figure 19.

The wintertime (January 1–March 31) DIN:DIP ratios based on molar concentrations at the Airisto stations 210 and 220 during 1997-2024. The Redfield ratio 16:1 is marked with a green crossline.

Figure 20.

The wintertime (January 1–March 31) DIN (NH4 + NO23) and DIP concentrations (µg/l) at the Airisto station 210 during 1991-2024.

Figure 20.

The wintertime (January 1–March 31) DIN (NH4 + NO23) and DIP concentrations (µg/l) at the Airisto station 210 during 1991-2024.

Figure 21.

DIN:DIP ratios based on molar concentrations of deep-water layers (over 20 m) in monitoring station Turm 220 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1991 to 2024The Redfield ratio 16:1 is marked with a green crossline.

Figure 21.

DIN:DIP ratios based on molar concentrations of deep-water layers (over 20 m) in monitoring station Turm 220 during the ecological classification period (1 July–7 September) from 1991 to 2024The Redfield ratio 16:1 is marked with a green crossline.

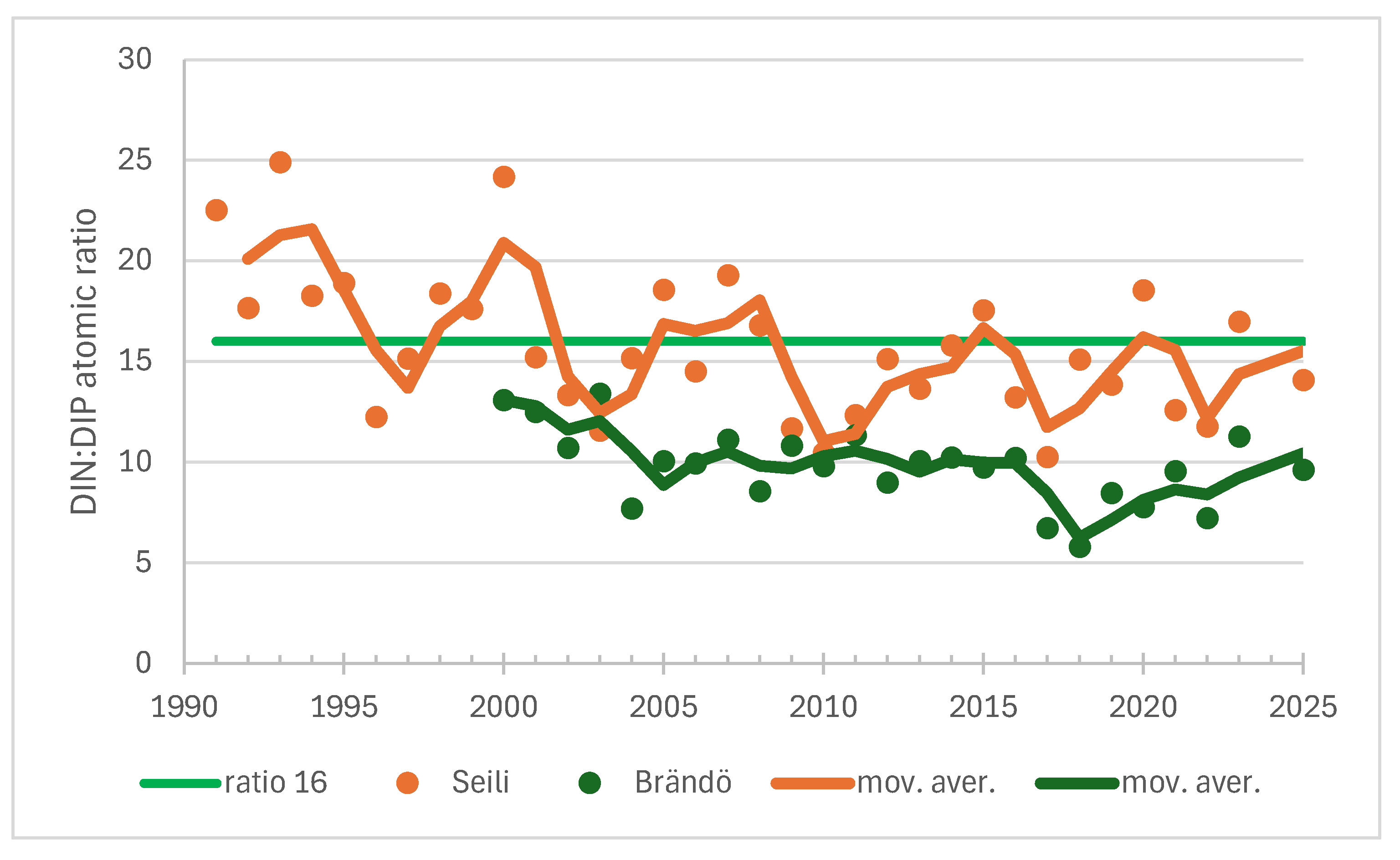

Figure 22.

The wintertime (January 1–March 31) DIN:DIP ratios based on molar concentrations at the Seili and Brändö stations during 1991-2024. The Redfield ratio 16:1 is marked with a green crossline.

Figure 22.

The wintertime (January 1–March 31) DIN:DIP ratios based on molar concentrations at the Seili and Brändö stations during 1991-2024. The Redfield ratio 16:1 is marked with a green crossline.

Figure 23.

Cyanophycaeae biomasses (µg/l) in surface water in July-August during 1999-2024 at the Airisto stations 210 and 220.

Figure 23.

Cyanophycaeae biomasses (µg/l) in surface water in July-August during 1999-2024 at the Airisto stations 210 and 220.

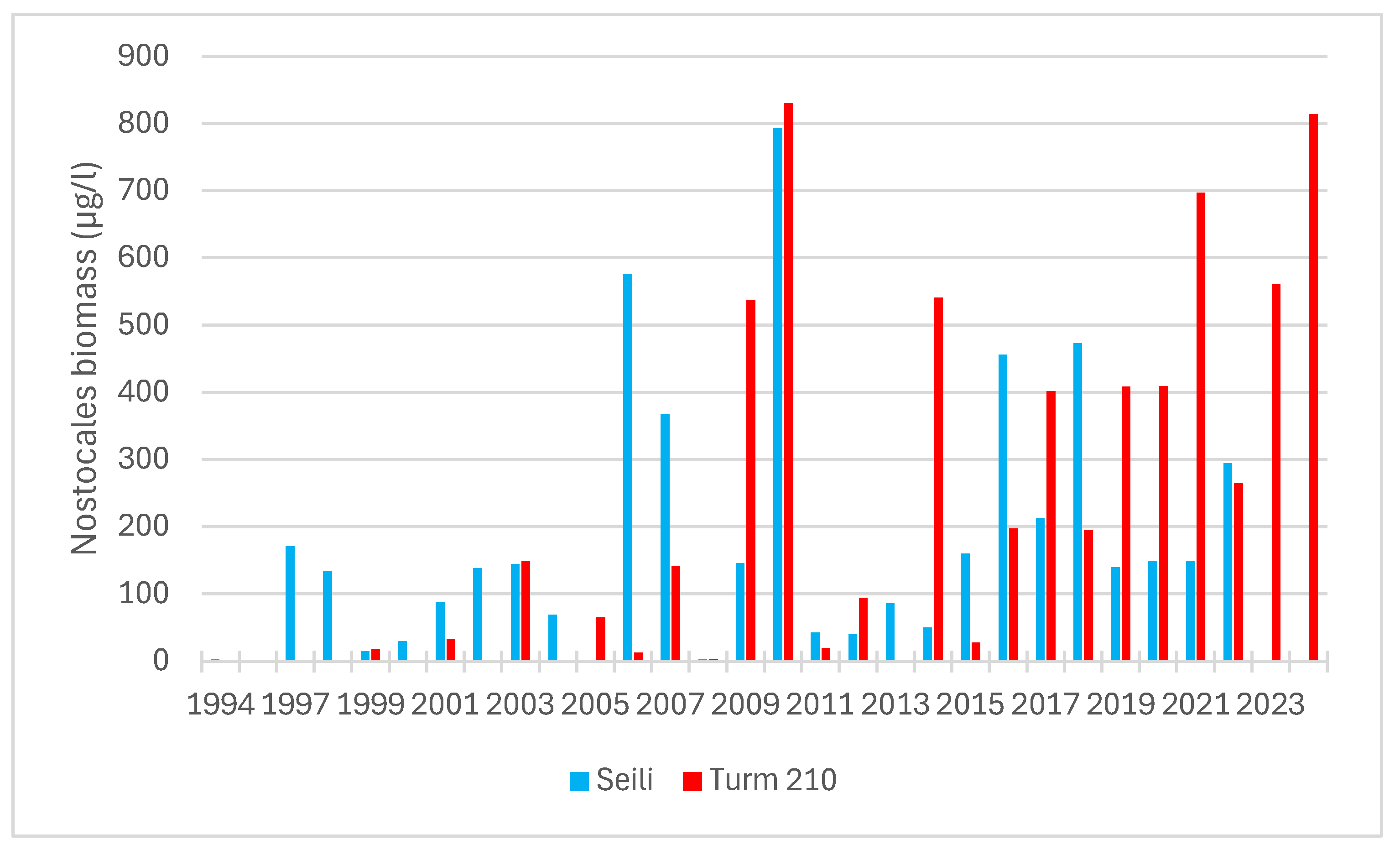

Figure 24.

Cyanophycaeae, order Nostocales biomasses (µg/l) in surface water in July-August during 1999-2024 at the Airisto stations 210 and Seili.

Figure 24.

Cyanophycaeae, order Nostocales biomasses (µg/l) in surface water in July-August during 1999-2024 at the Airisto stations 210 and Seili.

Figure 25.

The statistically significant relationship between total phosphorus concentrations (µg/l) and chlorophyll-a concentrations in the marine area off Turku at 34 monitoring stations during the years 1980–2024.

Figure 25.

The statistically significant relationship between total phosphorus concentrations (µg/l) and chlorophyll-a concentrations in the marine area off Turku at 34 monitoring stations during the years 1980–2024.